Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus (SPiL Plus)

On-line version ISSN 2224-3380

Print version ISSN 1726-541X

SPiL plus (Online) vol.67 Stellenbosch 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.5842/67-1-1005

AFRIKAANS LINGUISTICS

"Rêrag pragtag": A sociophonetic exploration of the vowel quality of the -ig suffix in Kaaps

Yolandi Ribbens-Klein

Research Fellow, Department of General Linguistics, Stellenbosch University, South Africa E-mail: yolandi.ribbens-klein@uct.ac.za

1. Introduction

In this squib, I propose a sociophonetic exploration into the vowel quality of the adjectivising and pseudo suffix -ig (spelled as <ig> or <ag>) in the language variety called Kaaps. This investigation not only falls within the ambit of the phenomenon of vowel-lowering in Afrikaans and Kaaps, but also aims to motivate further research on the acoustics of schwa /e/ in Afrikaans and Kaaps.1 I start out by briefly contextualising Kaaps as a social, ethno-regional linguistic entity that is indexical of not only place, but also involves identity politics related to experiences of marginalisation and self-affirmation. Next, I distinguish between adjectivising and pseudo suffixes, before discussing previous research on Afrikaans and Kaaps schwa and vowel-lowering. Comparing older phonetic texts to current research shows that while variation in schwa realisation was widespread in the early twentieth century, lowered schwa gradually became metapragmatically associated with present-day Kaaps. Finally, I propose further research directions that will seek to explore sociolinguistic, phonetic, and phonological processes involved in schwa realisation in the -ig suffix (henceforth referred to as the -ig vowel). The realisations of the -ig vowel can move us towards further exploration of Lass' (1986, 2007) claims that there is more to schwa than meets the transcriber's eye; it is possible that sounds transcribed as schwa are, in fact, cases where the eye is favoured instead of the ear. The spelling of the -ig vowel as <ag> in Kaaps points us in that direction.

2. Kaaps and the metapragmatic salience of <ag>

Geographically speaking, Kaaps is strongly associated with residents of the Cape Town peninsula and surrounding areas. According to Hendricks (2016: 5), while Kaaps is associated with Coloured speakers, it should be described as a sociolect, rather than an ethnolect, because it is foremost associated with Capetonians from a working-class background. However, owing to South Africa's colonial and apartheid legacy, the correlation between ethnic affiliation and varieties of Afrikaans remains significant and Kaaps plays an important role in identity politics. The increasingly racist political policies of the past century have had linguistic consequences, effectively creating a stark schism between Coloured and White Afrikaans speakers, with accompanying supra-regional myths (Wolfram, 2007: 295). With supra-regional myth-making, linguists and other language users alike assume a homogenising stance that favours the a priori grouping of speakers according to ethnicity (i.e. all speakers of an ethnic group as speakers of the same variety), thus obscuring the contribution of other social factors and specifically regional contexts to patterns of variation. Hence, we quite often see the use of the spurious labels "White Afrikaans" and "Coloured Afrikaans" (which traditionally includes Kaaps as a regional variety) for supra-regional ethnolects of Afrikaans.

Arguments for the recognition of Kaaps as a separate language, and not a variety or dialect of Afrikaans, is based on a premise that is succinctly summarised in a comment on the BBC's Language website about the dissolution of Serbo-Croatian into four separate languages. I rephrase it as follows: "Afrikaans and Kaaps have separate histories, developments, and most importantly, identities. Thus, even though they can be mutually understood by the respective speakers, they are not and cannot be one language" (see Attridge, 2021: 26). A concrete example of this position is the recent development of a Kaaps dictionary.2 As stated by Haupt (2021):

A Kaaps dictionary will validate [Kaaps] as a language in its own right. And it will validate the identities of the people who speak it. It will also assist in making visible the diverse cultural, linguistic, geographical and historical tributaries that contributed to the evolution of this language.

I agree with Attridge's (2021: 25) argument that "languages" denote "artificial, often politically instituted and regulated, phenomena; a more accurate picture of speech practices around the globe is of a multidimensional continuum." Thus, designating and proclaiming "speech practices" (i.e. language use as social practice) as "a discrete language" is underpinned by political ideologies, albeit ranging from the dubious to the justifiable.

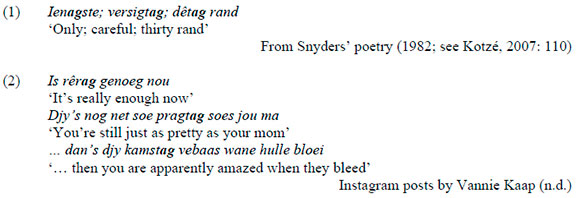

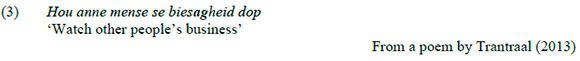

Hendricks (2012, 2016) and De Vries (2016) discuss the written "talige merkers'" ('linguistic markers') of Kaaps in literary and journalistic work. See Odendaal (2020) on the role of the poetic use of colloquial varieties of Afrikaans and Kaaps as strategic literary mechanisms to evoke socio-political impact, and to embody regional or group identities, realities, and lived experiences. Hendricks (2016: 7-26) provides an extensive list of linguistic features characteristic of Kaaps, primarily based on written sources. Thus, orthography is particularly drawn on to distinguish written Kaaps from other Afrikaans forms. Are we dealing here with eye dialect or pronunciation spelling: that is, does the spelling of <ig> as <ag> aim to represent dialect to the eye, or to the ear? If the former, then the writing <ig> as <ag> is indexical of Kaaps and performative of the Coloured self-identification of the language user, regardless of the actual vowel quality. With the latter, <ag> is a case of "skryf 'it soes jy praaf'3 ('write it as you speak', Trantaal, 2014), which of course also carries indexical meaning. Arguably the latter influenced the former, where language users' knowledge of the social meanings of language variation and metapragmatic awareness of the ways in which variants index different aspects of social contexts constitute "a crucial force behind the meaning-generating capacity of language in use" (Verschueren, 2000: 439).

De Vries (2016: 132) summarises the following writing or spelling styles that serve to index "tipies-KaapS" ('typical Kaaps'):

a) Direct borrowings from English and extensive code-switching/mixing;

b) Morphological embedding of English lexical items (e.g. gebother, 'bothered');

c) Localised lexical items (e.g. dronkie as diminutive of dronke or dronkaard, 'drunkard'); and

d) Pronunciation phenomena such as /e/-raising (e.g. beter 'better' written as bieter, i.e. using <ie> instead of <e>, where <ie> is pronounced as [i]); /o/-raising (e.g. hooggeleerde 'highly educated' written as hoeggeleerde, i.e. using <oe> instead of <oo>, where <oe> is pronounced as [u]); elision of postvocalic /r/ (e.g. maar 'but' written as maa); and /a:/-shortening and fronting (e.g. aan 'on' is written as an, i.e. using <a> instead of <aa>).

Not mentioned in the list above is the orthographic representation of schwa-lowering, where <ag> is used instead of <ig> to indicate the pronunciation of unstressed schwa in the suffix as a full, lowered vowel (e.g. pragtig 'stunning' written as pragtag, where <a> indicates a full vowel pronunciation instead of [a]; see Hendricks, 2016: 8). Kotzé (1984, 2007) finds that the pronunciation spelling of schwa-lowering occurred as early as 1856 in the text "Betroubare woord van Isjmoenf ('Trusted word of Isjmoeni'), an Afrikaans text originally written in Arabic orthography, and transliterated into Roman orthography by Van Selms (1953). For example: hoeghmoedagh4 (for hoogmoedig 'arrogant') and boes'aardaghait (for boosaardigheid 'evilness'). Kotzé (2007) used diachronic and synchronic sources to show that the occurrence of typical phonological features of spoken varieties of present-day Afrikaans can be traced back to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. One of these typical phonological features discussed by Kotzé (2007) is schwa-lowering in the ge- and -ig morphemes. I agree with Kotzé's (2007: 108) point that a phenomenon like schwa-lowering should be approached from the perspective of documenting sound variation and change processes, rather than from a comparative approach where one form is judged as the standard, and other forms as deviations from the standard.

My initial observations are also from written sources, where spelling seems to represent the pronunciation of the -ig vowel (in bold; reproduced here as written in the source):

The most striking example of the metapragmatic salience of the -ig vowel in Kaaps can be seen in a YouTube video by Vannie Kaap (2019), entitled "R.I.P. Kaaps" (in the video, it is explained that R.I.P. stands for "Rise in Power"). Screenshots in Figure 1 show the visuals, accompanied by the performer saying "Daai rêrig is jou rêrag" ('That rêrig is your rêrag'; at time point 01:36 in the clip).

Vannie Kaap's video shows how speakers, as agents, reflexively employ linguistic forms to produce and reproduce contextualised social structures. Reflexivity (as used here) refers to the states of "agentive consciousness" of people acting in social situations, "so that language use is appropriate to particular contextual conditions and effective in bringing about contextual conditions"; that is, reflexivity is part of speakers' metapragmatic awareness (Silverstein, 2006: 462-463). Metapragmatic awareness is a speaker's ability to recognise the usual or expected context for the use of certain linguistic expressions; this awareness is tied to certain properties of the linguistic forms (e.g. as markers of identity) that presuppose or entail contexts-of-use (Silverstein, 1981, 1993). Presupposition, in Silverstein's definition, is "appropriateness-to-context", where the meaning of the linguistic form as index is "already established between interacting sign-users", albeit implicitly (Silverstein, 2003: 195). With entailment, a sign's "effectiveness-in-context" is brought into being (i.e. created) by the usage of the indexical sign. Presupposition therefore works on the existing association of the indexical linguistic form to context-of-use, while with entailment, the language user creates a new context-of-use (Silverstein, 2003: 195; also see Eckert, 2008).

The main question I pose in this piece is: what is the quality of schwa in Kaaps unstressed suffixes written as <ag>? My interest in this matter is both sociolinguistic and phonetic/phonological. Firstly, in terms of sociolinguistics, of interest are the social meanings of this linguistic form that seem to have changed from a regional marker, to indexing ethnicity and place. In terms of phonetics/phonology, the phenomenon of vowel-lowering in Kaaps is also of interest: are we, in fact, actually dealing with schwa-lowering, or rather with retention of an older linguistic form (thus, centralisation to schwa was the innovation)? Furthermore, in a full vowel space for Kaaps, where does lowered schwa fall (potential for merger) and what is the vowel quality of schwa in general? And lastly, are supra-segmental aspects at play here, that is, can variation in intonation and stress patterns contribute to the vowel quality of the -ig suffix?

3. -ig as adjectivising or pseudo suffix

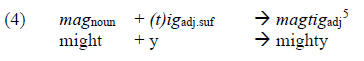

As stated, I am interested in segments that take the form <ig> or <ag> to explore variation in the realisation of the vowel. These segments frequently occur as adjectivising or pseudo suffixes. In brief, affixes are morphemes that attach to word stems to create different lexemes (listed in the lexicon) or word forms (lexemes with grammatical information); thus, affixes can determine or change the syntactic category of a word. Suffixes attach to the end of a word stem and are broadly categorised as derivational or inflectional. The former creates new lexemes: as shown in Example 4, the adjectivising suffix -ig derives an adjective from a noun.

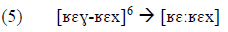

Looking closer at this suffix, it can often be difficult to discern its phonetic boundary, especially since the etymology of the original word formation has been lost over time. For example, with pragtag 'stunning' (seen in Example 2) and magtig (seen in Example 4), the <t> is a fossilised remnant of an older form of prag and mag (before the processes of t apocope; see Ponelis, 1989), c.f. Dutch pracht and macht. With -ig as a pseudo suffix, derivational processes are no longer apparent; the suffix is unanalysable, and mainly occurs in lexicalised forms, for example stadig 'slow'. The word rêrig 'really' in itself has an interesting etymology: derived from regreg 'right-right', a quite plausible speculation on the development of rêrig from reg-reg was shared with me by Prof. Jac Conradie (p.c., circa 2014). According to Conradie, early speakers of Afrikaans with uvular-r in their repertoire contributed to the change, where the velar fricative and uvular fricative merged at the word boundary:

The change was initiated in the first <reg> segment: firstly, the elision of inter-sonorant [γ] or merger with [κ], which is confirmed by the vowel lengthening [ε:]. This created the scenario where the <reg> in the second segment was reanalysed as a suffix, thus losing its lexical status, resulting in [ε] being changed to [a] or [ä].7

Trollip (2020) investigates two adjectivising suffixes that contain the -igvowel: -agtig, seen in jagluiperdagtig 'cheetah-like' and -erig/-rig, for example in hansworserig 'clownish'.8 Other adjectivising suffixes in Afrikaans are -tig (e.g. magtig 'mighty') and -ig (e.g. hongerig 'hungrily'). Although my focus is on phonetics and not morphology, adjectivising and pseudo suffixes can result in adjectives with different semantic properties and it will also be important in the analysis to distinguish between words with analysable and productive suffixes and words where the suffix became unanalysable (i.e. a pseudo suffix).

4. Variation in the vowel quality of Afrikaans schwa

Where previous studies focused on the orthographic representation of phonetic features in Kaaps, I propose a sociophonetic study of variation in Kaaps, starting with the realisations of vowels in unstressed syllables. Apart from taking a quantitative approach to determine the frequency of different variants according to linguistic and social factors, the first step should be to determine the range of possible vowel qualities. As I discuss in this section, going back to phonetic descriptions of almost a century ago, along with Lass' (1986, 2007) analysis of schwa as a vowel, a qualitative step is warranted to first determine the acoustic range of realisations grouped and transcribed as Afrikaans schwa.

Wissing (2020) discusses the role of schwa in Afrikaans stress placement and makes the distinction between two different types of monomorphemic words with word-final schwa. Type I monomorphemes have a single final /a/ (e.g. aarde /a:rda/ 'earth'), or a final syllable containing a schwa and a final sonorant consonant (/n/; /m/; /l/; /r/; /n/; e.g. nader /na:dar/ 'nearer'). With Type II monomorphemes, schwa occurs in a final syllable followed by an obstruent consonant (/k/; /x/; /s/, e.g. the pseudo suffixes -lik, -ig, and -nis). For both types of monomorphemes, schwa is not stressed, with stress falling on the penultimate syllable in bisyllabic and multisyllabic monomorphemes.

Afrikaans phoneticians classify Afrikaans /a/ as a full vowel phoneme that occurs in stressed and unstressed syllables, and which forms part of the group of short vowels (see, inter alia, Le Roux & Pienaar, 1927; Combrink & De Stadler, 1987; De Villiers & Ponelis, 1992; Wissing, 2011). One of the earliest descriptions of Afrikaans schwa is by Le Roux and Pienaar (1927). They describe the articulation parameters as follows:

(i) Hoogte van die tong - Ietsie hoër as middellaag, die gewone stand in die mond wanneer die person nie praat nie, net asemhaal.

'Height of the tongue. Somewhat higher than middle-low, the natural position in the mouth when the person is not speaking, only breathing.'

(ii) Deel van die tong wat die hoogste is - Tong lê horisontaal in die mond, 'n heeltemal neutrale stand. Artikulasie: middel van "voor", teenoor agterste deel van die [harde verhemelte].

'Part of the tongue that is the highest. Tongue lays horizontally in the mouth, a totally neutral position. Articulation: middle of "front", against back part of the hard palate.'

(Le Roux & Pienaar, 1927: 55)

The descriptions of a natural and neutral tongue position have stood the test of time, with more recent work using the same descriptions for tongue height and backness. Lass (1986: 18) singles out De Villiers (1976) for "obfuscating" the description of Afrikaans schwa articulation. Specifically problematic, according to Lass, is the description of the tongue as being in a natural or totally neutral position in the mouth, as when the person is not speaking. Lass attributes the origin of this general articulatory description to the direct use of the available phonetic description of schwa, without determining the actual acoustic and articulatory qualities of the vowel in question. According to Lass (1986: 1), "there is a good deal to be said against [a] as a symbol for unstressed vowels [...]. But 'stressed schwa', prominent in discussions of Afrikaans and English (among other languages), is probably just about inexcusable." For example, Figure 2 shows at least five different realisations of Afrikaans stressed schwa in monosyllabic words (i.e. stress bearing) identified by Lass (1986: 19):

Lass (2007) argues that his dialect of English contains at least seven different kinds of schwa (i.e. seven different vowel qualities that appear in unstressed syllables), and argues that the common practice of transcribing all of these vowels as [a] is a misleading reification. Mesthrie (2017) should also be mentioned for providing an in-depth investigation into variant realisations of schwa in Black South African English.

When compared to Dutch, most cases of Afrikaans schwa resulted from centralisation and lowering of /i/. Furthermore, Le Roux and Pienaar (1927: 55) list the following vowels that are also centralised to /a/ in bisyllabic words: /a ο o: e: y i si/. This might indicate that stress placement played a role in centralisation and neutralisation. Furthermore, Le Roux and Pienaar (1927: 55) remark that many Afrikaans speakers pronounce /a/ as [i], especially in penultimate syllables preceding a final -ing [aj], for example in belediging [bale:dixaj] 'insult'. Le Roux and Pienaar (1927: 54) also found that schwa is occasionally realised as [ε] in words such as niggie [nexi] 'female cousin', distrik [dastrek] 'district', and gesig [xasεx] 'face'. They refer to this pronunciation as "plat uitspraak" (flat pronunciation, which might mean 'lower', but is, rather uncomfortably, associated with a value judgment of 'coarse or unsophisticated'), and state that this is a known phenomenon in older Dutch and in the Dutch volkstaal ('colloquial Dutch'). Furthermore, and of particular interest to the current discussion, Le Roux and Pienaar (1927: 55) note the following: "in verskillende woorde is a oorgegaan tot a, gewoonlik voor x in the uitgang -ax" ('in different words [a] changes to [a], usually before [x] in the ending [ax]'). They also describe this pronunciation as plat. An intriguing suggestion is made by Le Roux and Pienaar in a footnote, where they conjecture that vowel harmony could have been an influence in the development of [a] realisations. Thus, the vowel quality in the preceding word stem should also be taken into account. Furthermore, Le Roux and Pienaar (1927) provide transcriptions of various speakers and speech styles, amongst which are transcriptions of both Le Roux and Pienaar's speech. A note is made about Le Roux's pronunciation of vinnig 'fast' as [fanax] and regtig 'really' as [regtax] (i.e., [a] instead of [a]); they find that "owerigens is die uitspraak plat" ('the pronunciation is largely coarse'; Le Roux and Pienaar, 1927: 218, note 11). Le Roux grew up in Wellington (Western Cape Province), and even though he left the area at age 21, his accent remained unchanged. Pienaar, who was from what is now the North West Province, also had [fanax] and [regtax] in the transcription of his speech. Thus, in the early twentieth century, [ax] seems to have been a variant form of the -ig vowel, showing a large geographical spread. Based on clear evidence of variation, plus Lass' arguments, there is a strong indication of a range of schwa variants, such as [ï ë a ä]. Returning to the question of the vowel quality of the -ig in Kaaps, a sociophonetic study can determine a possible range of schwa variants originally transcribed as /a/, and show that the long tradition of spelling <ig> as <ag> is in fact a more accurate phonetic representation.

5. Concluding remarks

In this squib, I made the call for further investigation into the sociophonetics of schwa in the Afrikaans and Kaaps -ig suffix. In terms of orthography, <ag> is a metapragmatically salient feature of Kaaps. However, based on a review of earlier sources, realisations of the sounds transcribed as schwa in the -ig suffix in fact showed variation. The literature points to a full vowel, instead of schwa, being the widely used form, before being centralised by some Afrikaans speakers; the spelling of the -ig vowel as <ag> in Kaaps also points us in that direction. Indexicality - referring to how the social meanings of linguistic forms can shift from context to context and change over time - is a useful concept here. A century ago, [a] instead of [a] in the unstressed -ig suffix was already recognised as a phonetic feature associated with regional varieties spoken in the south-western parts of South Africa; that is, a Western Cape feature, without specific associations with different social groups of speakers.

Furthermore, it is also worth considering different intonation and stress patterns in Kaaps -thus, we might be dealing with a case of supra-segmental variation. The possibility of vowel harmony - as alluded to by Le Roux and Pienaar (1927) - should also be explored further. Finally, given the possibility of the retention of older realisations of the -ig vowel, this study can be expanded on by looking at a specific chronolect of Afrikaans, as used by the last remaining Afrikaans speakers in Patagonia, Argentina; a current project of Andries Coetzee, whom this special edition is honouring.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Prof. Rajend Mesthrie and the National Research Foundation for funding (SARChI grant no. 64805). Also, my recent experiences working with Prof. Andries Coetzee were extremely rewarding and I thank him for his interest and support. Lastly, I am much obliged to the two reviewers for their valuable feedback.

References

Attridge, Derek. 2021. Untranslatability and the challenge of World Literature: A South African example. In Francesco Giusti & Benjamin Lewis Robinson (Eds.). The Work of World Literature, 25-56. Berlin: ICI Berlin Press. https://doi.org/10.37050/ci-1902 [ Links ]

Combrink, J. G. H. & De Stadler, Leon G. 1987. Afrikaanse Fonologie [Afrikaans Phonology]. Johannesburg: Macmillan. [ Links ]

De Villiers, Meyer & Ponelis, Fritz A. 1992. Afrikaanse Klankleer [Afrikaans Phonetics and Phonology]. Cape Town: Tafelberg. [ Links ]

De Villiers, Meyer. 1976. Afrikaanse Klankleer. Fonetiek, Fonologie en Woordbou [Afrikaans Phonetics, Phonology and Word Formation]. Cape Town: A.A. Balkema. [ Links ]

De Vries, Anastasia. 2016. Kaaps in koerante [Kaaps in newspapers]. In Frank Hendricks & Charlyn Dyers (Eds.). Kaaps in Fokus [Kaaps in Focus], 123-136. Stellenbosch: SUN MeDIA Stellenbosch. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1nzfx8c.13 [ Links ]

Eckert, Penelope. 2008. Variation and the indexical field. Journal of Sociolinguistics 12(4): 453-476. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9841.2008.00374.x [ Links ]

Haupt, Adam. 2021. The first-ever dictionary of South Africa's Kaaps language has launched - why it matters. The Conversation, 29 August 2021. Available: https://theconversation.com/the-first-ever-dictionary-of-south-africas-kaaps-language-has-launched-why-it-matters-165485. (Accessed December 2021)

Hendricks, Frank. 2012. Om die miskende te laat ken. 'n Blik op Adam Small se literêre verrekening van Kaaps [To acknowledge the unacknowledged. A consideration of Adam Small's literary account of Kaaps]. Tydskrif vir Letterkunde 49(1): 95-114. https://doi.org/10.4314/tvl.v49i1.8 [ Links ]

Hendricks, Frank. 2016. Die aard en konteks van Kaaps: 'n Hedendaagse, verledetydse en toekomsperspektief [The nature and context of Kaaps: A present, past and future perspective]. In Frank Hendricks & Charlyn Dyers (Eds.). Kaaps in Fokus [Kaaps in Focus]. Stellenbosch: SUN MeDIA Stellenbosch. 1-36. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1nzfx8c.5 [ Links ]

Kotzé, Ernst F. 1984. Afrikaans in die Maleierbuurt: 'n Diachroniese perspektief [Afrikaans in the Malay neighbourhood: A diachronic perspective]. Tydskrif vir Geesteswetenskappe 24(1): 41-72. [ Links ]

Kotzé, Ernst F. 2007. Die betroubare woord:'n beskouing van Arabies-Afrikaanse, Maleierafrikaanse en Kaaps-Afrikaanse tekste as fonologiese bloudruk vir hedendaagse Praatafrikaans [The trustworthy word: a consideration of Arabic-Afrikaans, Malay Afrikaans and Cape Afrikaans texts as phonological blueprint for current colloquial Afrikaans]. Tydskrif vir Nederlands en Afrikaans 14(2): 107-118. [ Links ]

Lass, Roger. 1986. On schwa. Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics 15: 1-30. https://doi.org/10.5774/15-0-95 [ Links ]

Lass, Roger. 2007. On schwa: synchronic prelude and historical fugue. In Donka Minova (Ed.). Phonological Weakness in English: From Old to Present-day English, 47-78. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Le Roux, T. H. & Pienaar, P. de Villiers. 1927. Afrikaanse Fonetiek [Afrikaans Phonetics]. Cape Town & Johannesburg: Juta. [ Links ]

Mesthrie, Rajend. 2017. Class, gender, and substrate erasure in sociolinguistic change: A sociophonetic study of schwa in deracializing South African English. Language 93(2): 314346. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2017.0016 [ Links ]

Odendaal, Bernard J. 2020. The poetic utilization of dialectal varieties of the Afrikaans language for strategic purposes in the Southern African context. In Norbert Bachleitner (Ed.). Literary Translation, Reception, and Transfer, 465-476. Berlin: De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110641998-037 [ Links ]

Ponelis, Fritz A. 1989. Ontwikkeling van klusters op sluitklanke in Afrikaans [Development of clusters on stops in Afrikaans]. South African Journal of Linguistics 7(1): 1-5. https://doi.org/10.1080/10118063.1989.9723783 [ Links ]

Silverstein, Michael. 1981. The limits of awareness. Southwest Educational Development Laboratory Vol. 84. Austin, TX: Southwest Educational Development Laboratory. [ Links ]

Silverstein, Michael. 1993. Metapragmatic discourse and metapragmatic function. In John A. Lucy (Ed.). Reflexive Language, 33-58. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511621031.004 [ Links ]

Silverstein, Michael. 2003. Indexical order and the dialectics of sociolinguistic life. Language and Communication 23: 193-229. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0271-5309(03)00013-2 [ Links ]

Silverstein, Michael. 2006. Reflexivity. In Keith Brown (Ed.). Encyclopedia of Language & Linguistics, 462-463. 2nd ed. Volume 10. Oxford: Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-08-044854-2/00385-0 [ Links ]

Snyders, Peter. 1982. 'n Ordinary Mens [An Ordinary Person]. Cape Town: Tafelberg. [ Links ]

Trantraal, Nathan. 2013. Chokers en Survivors [Chokers and Survivors]. Cape Town: Kwela Books. [ Links ]

Trantraal, Nathan. 2014. Skryf 'it soes jy praat [Write it like you say it]. LitNet, 7 November 2014. Available: http://www.litnet.co.za/Article/poolshoogte-skryf-i-soes-jy-praat. (Accessed December 2021)

Trollip, Benito. 2020. Denominal adjectives in Afrikaans: The cases of agtig and e rig. SKASE Journal of Theoretical Linguistics 17(5): 27-41. [ Links ]

Van Selms, Adrianus. 1953. Die oudste boek in Afrikaans: Isjmoeni se "Betroubare Woord" [The oldest book in Afrikaans: Isjmoeni's "Trusted Word"]. Hertzog-Annale van die Suid-Afrikaanse Akademie vir Wetenskap en Kuns 2(2): 61-103. [ Links ]

Vannie Kaap [@vannie.kaap]. n.d. Posts [Instagram profile]. Online: https://www.instagram.com/vannie.kaap/. (Accessed September 2021)

Vannie Kaap. 2019 (25 January). R.I.P. Kaaps. YouTube. Online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J5R7IySRXHo&abchannel=VannieKaap. (Accessed December 2021)

Verschueren, Jef. 2000. Notes on the role of metapragmatic awareness in language use. Pragmatics 10(4): 439-456. https://doi.org/10.1075/prag.10.4.02ver [ Links ]

Wissing, Daan. 2011. Ontronding in Afrikaans [Unrounding in Afrikaans]. Tydskrif vir Geesteswetenskappe 5: 11-20. [ Links ]

Wissing, Daan. 2020. Primary stress in Type-II monomorphemes ending on schwa. Taalportaal. Online: https://taalportaal.org/taalportaal/topic/pid/topic-14779379810951225. (Accessed September 2021)

Wolfram, Walt. 2007. Sociolinguistic folklore in the study of African American English. Language and Linguistics Compass 1(4): 292-313. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-818X.2007.00016.x [ Links ]

1 I will make the differentiation between Kaaps and Afrikaans in the next section: however, when I use the word "Afrikaans" elsewhere in this squib, it should be taken to include Kaaps, unless stated otherwise.

2 See details about the Kaaps dictionary project here: http://dwkaaps.co.za/.

3 Note the spelling differences: "skryf dit soos jy praat". Firstly, elision of initial consonant <d> of dit 'it'; <soes> soos 'like' indicates raising of /o/ to [u] (/sos/ to [sus]), which is a feature of Kaaps.

4 In Van Selms, /x/ is written as <gh> instead of <g>.

5 Abbreviations: adj.suf for adjectivising suffix; adj for adjective.

6 Or [rexrex]; voicing assimilation is probable for the first /x/, hence my narrow transcription of the voiced velar fricative[Y] instead of the voiceless velar fricative [x].

7 I am using [ä] to show centralised [a]; however, other sources, such as Le Roux and Pienaar (1927), use [a].

8 With -erig, <e> is a linking morpheme.