Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Lexikos

On-line version ISSN 2224-0039

Print version ISSN 1684-4904

Lexikos vol.33 spe Stellenbosch 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.5788/33-2-1843

ARTICLES

Gender Stereotypes in Dictionaries: The Challenge of Reconciling Usage-based Lexicography with the Role of Dictionaries as Social Agents

Genderstereotipes in woordeboeke: Die uitdaging om die gebruiksgebaseerde leksikografie met die rol van woordeboeke as sosiale werktuie te versoen

Carolin Müller-Spitzer

Institut für Deutsche Sprache, Mannheim, Germany (mueller-spitzer@ids-mannheim.de)

ABSTRACT

In many countries of the world, perspectives on gender equality and racism have changed in recent decades.1 One result has been more attention being devoted to traces of androcentric and racist language in society. This also affects dictionaries. In lexicography there are discussions about whether or to what extent social asymmetries are inscribed in dictionaries and if this is still acceptable. The issue of the nature of description plays an important role in this discussion. If sexist usages are often found in language use, i.e. in the corpus data on which the dictionary is based, does the dictionary also have to show them? How is this, in turn, compatible with the normative power of dictionaries? Do dictionaries contribute to the perpetuation of gender stereotypes by showcasing them under the banner of descriptive principles? And what roles do lexicographers play in this process? The article deals with these questions on the basis of individual lexicographical examples and current discussions in the lexicographic and public community.

Keywords: gender and language, gender stereotypes, collocations, corpus-based lexicography, dictionaries as social agents

OPSOMMING

In baie lande van die wêreld het perspektiewe op gendergelykheid en rassisme in onlangse dekades verander.1 Een uitvloeisel hiervan is dat meer aandag geskenk word aan spore van androsentriese en rassistiese taal in die gemeenskap. Dit beïnvloed ook woordeboeke. In die leksikografie is daar besprekings oor of en tot watter mate sosiale asimmetrieë in woordeboeke beskryf word en of dit nog aanvaarbaar is. Die kwessie rondom die aard van beskrywing speel 'n belangrike rol in hierdie bespreking. Moet die woordeboek ook seksistiese gebruike opneem indien dit dikwels in taalgebruik, bv. in die korpusdata waarop die woordeboek gebaseer is, gevind word? Hoe is dit op sy beurt weer versoenbaar met die normatiewe krag van woordeboeke? Dra woordeboeke by tot die verewiging van genderstereotipes deur hulle onder die vaandel van beskrywende beginsels op te neem? En watter rolle moet leksikograwe in hierdie proses speel? In dié artikel word op grond van individuele leksikografiese voorbeelde en huidige besprekings in die leksikografiese en openbare gemeenskap aan hierdie vraagstukke aandag geskenk.

Sleutelwoorde: gender en taal, genderstereotipes, kollokasies, korpusgebaseerde leksikografie, woordeboeke as sosiale werktuie

Culture does not make people. People make culture. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

1. Introduction

In a recent article, Rufus Gouws classifies dictionaries not only as utility instruments commenting on linguistic issues, but also as "agents": "As an agent in social impact, it reflects the culture of the speech community but often also the attitudes and assessment of the lexicographer and the broader speech community towards their world and the prevailing ideologies and different ways of thinking" (Gouws 2022: 40). This position is not new. Wiegand, for example, had already pointed out that so-called cultural dictionaries offer possibilities of identification through their descriptions: "It is also true that, especially in the field of so-called cultural words, in the field of political-social lexis, as well as in the case of moral-ethical terms, general monolingual dictionaries always make offers of identification." (Wiegand 1995: 212).2 Bergenholtz also stated that it is not only politically loaded vocabulary (such as democracy or freedom) that requires a political positioning of the lexicographer: "Lexicography without value assessments and without social commitment is an illusion and, furthermore, not possible. … traces of political and cultural-political attitudes are found not only in meaning paraphrases, but also in the external and internal selection process" (Bergenholtz 2001: 500).3 Bergenholtz and Gouws even go so far as to say that "every single lexicographical decision has a language-political relevance and therefore, in the end, a political dimension" (Bergenholtz and Gouws 2006: 14).

This provides both opportunities and risks. One of the opportunities is that dictionaries may contribute to social transformation, as Gouws outlined for the South African dictionary landscape after the end of apartheid. He emphasised that the dictionaries to be compiled promote communication between the newly acknowledged national languages (cf. Gouws 2001: 522; for a different context cf. also Wiegand 1995). On the other hand, there is a risk that dictionaries may contribute to exclusion, for example, by perpetuating racist attributions or gender stereotypes. In this sense, lexicographers have a high degree of responsibility: "This puts an enormous responsibility on the shoulders of lexicographers to include a representative selection of items from a given language and to treat these items in an objective, responsible and unbiased way" (Gouws 2022: 40).

In addition to racism, the issue of gender constructions has received much more attention in recent years. Therefore, greater attention has been devoted to traces of an androcentric society in language. This also affects dictionaries. There are lexicographical discussions about whether or to what extent social asymmetries should be inscribed in dictionaries and if this is still acceptable, e.g. if listing a lexeme such as bitch as a synonym for woman is still a justifiable lexicographic choice. The issue of descriptivity plays an important role in this discussion. One of the questions arising from descriptive considerations is whether dictionaries have to portray everything the corpus basis suggests, even if it goes against moral considerations.

The construction of large digital corpora, the potential they offer, and the partial automation of lexicographic processes were central topics in lexicography and dictionary research in the last decades. Corpus-based lexicography is a great achievement when the aim is to base dictionary descriptions on actual language use. However, the question of how different sources differ and how to deal with more problematic aspects of language use has been somewhat forgotten in the light of these promising possibilities. For example, if sexist usage is common in language use, i.e. in the corpus data on which the dictionary is based, does the dictionary also need to show it? How is this, in turn, compatible with the function of dictionaries as instruments of inclusion and as social agents? Within this context, this paper aims to highlight the debate about gender stereotypes in dictionaries (section 2), show how the lexicographic database can introduce biases into dictionaries with a case study on collocations for man and woman in German (section 3), and what can be learned from this, using the example of primary school dictionaries in South Africa (section 4).

2. Gender stereotypes in dictionaries4

Personal designations such as man and woman can be understood as 'cultural words' in a broader sense (cf. Nied Curcio 2020: 186): cultural changes in society are also reflected in discussions about appropriate language, e.g. for women and men or for non-binary people. For example, in the wake of the #MeToo movement, there are debates about whether and how everyday sexism is reflected in language. These debates also have an impact on dictionaries. One example is the petition "Have you ever googled 'woman'?" which Maria Beatrice Giovanardi started in 2019. There she primarily complained about the description of women in various dictionaries, including lexicographic works by Oxford University Press, e.g. that filly, biddy or bitch are listed as synonyms for woman:

The first search involved googling 'woman synonyms' and boom - an explosion of rampant sexism. I thought to myself, 'What would my young niece think of herself if she read this?' […] Should data about how language is used control how women are defined? Or should we take a step back and, as humans, promote gender equality through the definitions of women that we choose to accept? […] We talked about how the dictionary is the most basic foundation of language and how it influences conversations. Isn't it dangerous for women to maintain these definitions - of women as irritants, sex objects and subordinates to men? (Giovanardi 2020)

Oxford University Press responded to these questions saying that their dictionaries tried to reflect the language, not to "dictate" language use (cf. Flood 2019). First, however, some brief remarks on gender roles in dictionaries need to be made.

Dictionaries in general are often a reflection of their time, i.e. the way that they describe the meaning of certain lexical units must always be seen in their respective historical contexts. They are linguistic resources that reflect and reproduce gender stereotypes (Nübling 2009: 594; cf. also Bergenholtz and Gouws 2006: 15). Consider the following example phrases taken from the entries on man, woman, girl and boy in the up-to-date online version of the Cambridge Dictionary,5 reproducing stereotypical gender concepts (on stereotypes in general cf. McGarty, Yzerbyt and Spears 2002):

- "He plays baseball, drinks a lot of beer and generally acts like one of the boys."

- "Steve can solve anything - the man's a genius."

- "She's a really nice woman."

- "Who was that beautiful girl I saw you with last night?"

- "Both girls compete for their father's attention."

Such entries concerning gender can be found in many dictionaries and have been discussed for a long time. Very pointedly and amusingly, Luise Pusch has shown how gender stereotypes that were prevalent at that time can be read in example phrases of the German Duden Bedeutungswörterbuch from 1970:6 The man, i.e. "he", "shows an acrobatic mastery of his body", "his soul is able to encompass the universe" and "he had a great impact". "She," on the other hand, "is always neatly dressed," "took the baby out daily," "awaits his return with great anxiety," and "she looked up to him as to a god."7 Pusch summarizes: "In the preface, the editors write that the 'basic vocabulary of German in its basic meanings' is to be presented. They succeed in much more: they convey a deep, unforgettable insight into the soul of German, into its basic treasure of feelings and thoughts" (Pusch 1984: 144; for more details on various German dictionaries cf. Nübling 2009). This illustrates that dictionaries are often a mirror of their time and thus also one of the important "platforms for productions of gender" (Nübling 2009: 594 [my translation]). Similarly, in their analysis of a contemporary Chinese dictionary, Hu, Xu and Hao (2019) point out that women "are often constructed in peripheral and domestic roles, as daughter, mother or grandmother" (Hu, Xu and Hao 2019: 28). In contrast, men "are described as strong in physical strength, versatile in skills and noble in their actions. In other words, men are represented as valuable, active social members" (Hu, Xu and Hao 2019: 28) These stereotypical representations of men and women are therefore not only to be found in dictionaries of the past, but also in current lexicographical works (cf. e.g. Fuertes-Olivera and Tarp 2022).

Dictionary editors' conscious positioning is particularly relevant because dictionaries can be understood as normative instances, even if they are primarily intended to be descriptive (Ripfel 1989; Sinclair 1992; Barnickel 1999; Hidalgo Tenorio 2000; Kotthoff and Nübling 2018). Therefore, lexicographers have a special responsibility not to contribute to perpetuating gender stereotypes by showcasing them under the banner of descriptive principles. After Pusch's essay cited above, attempts were made by the Duden editors to improve the dictionary in many ways, e.g. by avoiding unnecessarily stereotypical example phrases and by systematically including female occupational designations (Kunkel 2004; cf. also Westveer et al. 2018; Nübling 2009: 595)

The representation of gender in dictionaries is a matter of both language use and lexicographic-moral responsibility. Regarding language use, however, it is necessary to look closely at the data basis that is considered to represent this use. As in the field of machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI), lexicographers should discuss whether the selection of a particular database introduces additional, probably unintended, biases into their analyses (and then into the dictionaries). To illustrate the problem of gender bias in dictionaries, I will approach the basic problem from two very different perspectives. First, a summary of a comparative corpus study of German will show what influence the corpus base can have on the representation of gender roles in a dictionary. Secondly, I would like to illustrate more anecdotally how gender stereotypes are (unconsciously) reproduced on thematic pages in two concrete dictionaries for children from the South African dictionary landscape, and how these representations can be made more inclusive through greater awareness of gender stereotypes (and the desire to avoid them).

3. The database as a source of bias

Biases that are introduced by the database are a well-known problem in computer-linguistic research. For example, Caliskan et al. summarise the results of a study on semantics derived automatically from language corpora like this: "Our results indicate that text corpora contain recoverable and accurate imprints of our historic biases, whether morally neutral as toward insects or flowers, problematic as toward race or gender, or even simply veridical, reflecting the status quo distribution of gender with respect to careers or first names." (Caliskan, Bryson and Narayanan 2017: 184). This is in line with a growing number of studies conducted in the field of ML or AI, stating that these technological systems "often influence, reflect, and reinforce gender stereotypes" (Singh et al. 2020: 1281; cf. also Chen et al. 2021; Criado Perez 2020).

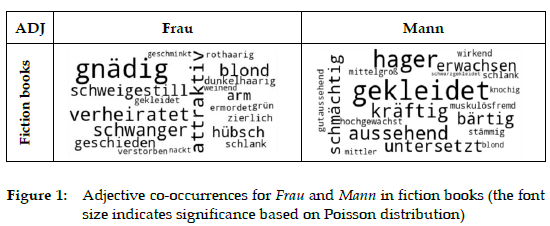

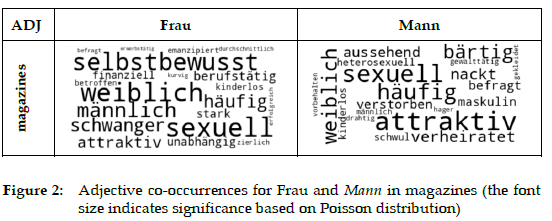

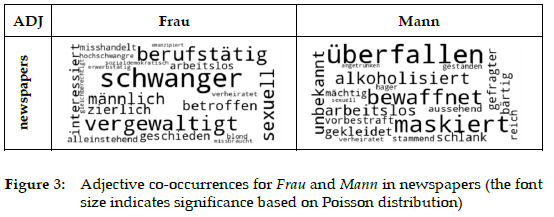

To investigate whether this problem also applies to corpus-based dictionaries, i.e. whether different corpus samples lead to different meaning paraphrases, we examined collocations for Mann (man) and Frau (woman) in different text sources (cf. Müller-Spitzer and Rüdiger 2022). The analyses presented in the following are based on three corpora for German, compiled from different source materials. The first is a corpus of 'Fiction Books' which is based on various works of fiction (20th and 21st century). The second, 'Magazines', is a corpus containing various periodicals on food, lifestyle, psychology, nature, education, etc. The third corpus consists of 'Newspapers' (for details cf. Nied Curcio 2022: 134). For the comparison, co-occurrences were filtered to include only tokens that were annotated at least once by the TreeTagger8 with the adjective POS tag. Common co-occurrences were filtered by the 100 most significant entries (based on Poisson distribution; cf. Heyer, Quasthoff and Wittig 2006: 134). In the following figures (Figures 1-3), we see all adjectives co-occurring with Mann and Frau in these three corpora. Adjectives are especially interesting to examine gender stereotypes as they are used, among other things, to describe entities. Thus, they would be included in a collocation set answering a question such as "What is a woman or a man like?" Our three corpora show different tendencies in this regard.

In works of fiction women are mainly described regarding their appearance, e.g. blond, pretty or attractive (blond, hübsch, attraktiv; n=10/20), but also in terms of their marital status (married or divorced - verheiratet, geschieden), or pregnant (schwanger). The adjective schweigestill seems to be a tagging error (it is not a German adjective) and gnädig points to the quasi-lexicalized, outdated address comparable to milady or madam/ma'am (gnädige Frau). For man, in contrast, adjectives describing appearance clearly dominate, e.g. gaunt, stout, stocky, bearded or lanky (hager, kräftig, untersetzt, bärtig, schmächtig).

In magazine texts only three collocators refer to appearance (attraktiv, kurvig, zierlich - attractive, curvy, petite), while pregnant and childless (schwanger, kinderlos) refer to the role of (not) being a mother. Adjectives referring to marital status are not part of the most significant collocates. Interestingly, women are rather characterized as self-confident, employed, independent, strong or emancipated (selbstbewusst, berufstätig, unabhängig, stark, emanzipiert). Therefore, the magazine corpus is the only dataset in which women are more characterized by other adjectives than those referring to appearance, social roles or violence. Men, on the other hand, are described as attractive, married, bearded, naked, gay or *-looking (attraktiv, verheiratet, bärtig, nackt, schwul, aussehend). Surprisingly, a considerable number of terms relate to appearance, social role or sexual orientation.

In the newspaper texts, women are described in terms of marital roles (alleinstehend, verheiratet, geschieden - single, married, divorced) and as pregnant (schwanger, hochschwanger). We also find collocators referring to work (berufstätig, erwerbstätig) and to emancipation (emanzipiert, gleichberechtigt). What is striking, however, is the diverse and dominant vocabulary referring to physical violence: raped (vergewaltigt), probably both in its adjectival and its participial/passive use, is the most significant collocate after pregnant and employed. Sexual (sexuell) and affected (betroffen) could point to contexts such as affected by sexual violence. Other collocators indicating violence are misshandelt and missbraucht (mistreated, misused). Also for men, violent acts or potentially dangerous physical/ mental states are a predominant topic in the newspaper corpus: armed, masked, alcoholised, drunk, previously convicted (bewaffnet, maskiert, alkoholisiert, angetrunken, vorbestraft) are significant collocators of Mann.

The examples show how strongly 'language use' depends on the empirical basis. The linguistic-thematic embedding of the words Frau and Mann in the various text groups show several overlaps (e.g. appearance and, for women, marital status), but also significant differences (fiction: dominance of appearance; magazines: topics of emancipation arise; newspapers: violent acts dominate for both lexemes). It is therefore too simplistic to state that meaning paraphrases and examples dictionaries should be based on 'language use', as this can mean very different things in different contexts. At least in academic lexicography, scrutiny is necessary to determine which source is responsible for which descriptions in the dictionary. This finding also highlights the importance of good metadata for linguistic corpora. For example, when corpora used in lexicography are crawled from the web and lack metadata such as text type, source or authorship, it is even harder to adequately reflect or classify the different contexts in which texts were created.

When lexicographers aim at designing dictionaries as instruments of inclusion, it is certainly a sensible approach to avoid over-emphasising gender in entries concerning men and women, while still basing the descriptions on actual language use. For example, linguistic contexts that point to violence and are taken from newspaper corpora must be classified as such - it is not 'general language use', but that of a specific genre or jargon. It is another question whether such examples should be part of a general language dictionary at all, which will not be discussed in this paper. Contrastingly, the various sets of collocations from magazines show that men and women can be portrayed in totally different ways (e.g. as self-confident and emancipated). These collocations are certainly preferable when balanced portrayal is an aim in dictionary-making. Kaplan also argues for a carefully curated selection: "Unlike those offered by the regular English dictionaries, bias-free and inclusive paraphrases of meaning reflect real usage and the real consequences of bias and exclusion. Such paraphrases of meaning and illustrations are necessary in order for dictionaries and lexicographical resources as a whole to provide users with information that is trustworthy, culturally aware, and socially responsible" (Kaplan 2020: 218).

4. Gender stereotypes in the Longman school dictionaries

As far as I know, the South African dictionary landscape is unique in that, after apartheid, nine indigenous languages were recognised as national languages alongside the colonial languages English and Afrikaans, and dictionaries were developed specifically for these 'new' national languages, initiated by PanSALB (Pan South African Language Board). PanSALB's goal is to "accelerate the production of dictionaries" in order to create "the conditions for the development of and the equal use of all official languages".9 Another special feature is that leading academics are involved in the development of very different types of dictionaries (cf. e.g. Gouws 1993), for example, the Longman dictionaries for all official languages of South Africa, which are published with Rufus H. Gouws and Danie Prinsloo as series consultants. Such dictionaries or textbooks can play an important role in (un)learning gender stereotypes: "Textbooks are used by teachers as a core means of teaching in 70-95% of classroom time. Gender-sensitive books can encourage children to discuss gender stereotypes and help promote equitable behaviour" (Benavot 2016).

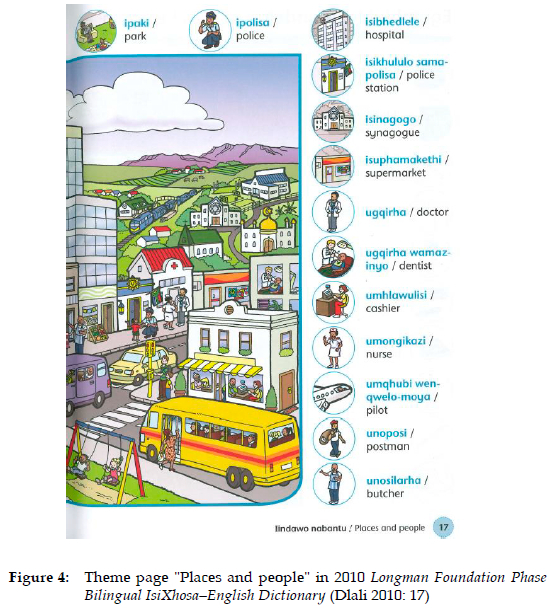

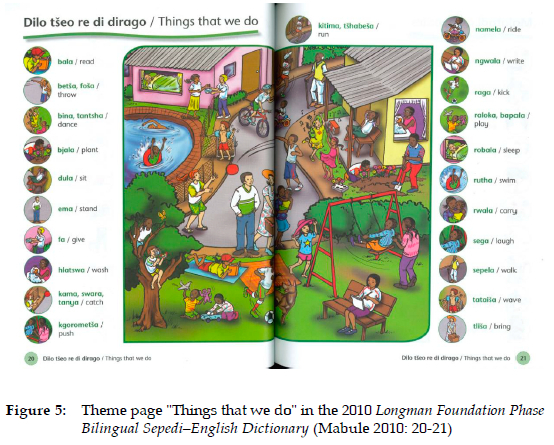

The last two decades have seen many societal changes regarding gender constructions. Not only are women's rights being discussed more often and with more positive outcomes - the binary gender order itself is gradually being deconstructed. Therefore, it is worth looking at teaching material and reference works with a new critical eye to see if there is room for improvement. The dictionaries I examine are the 2010 Longman Foundation Phase Bilingual Sepedi-English Dictionary (Mabule 2010) and the 2010 Longman Foundation Phase Bilingual IsiXhosa-English Dictionary (Dlali 2010). These dictionaries contain word lists and a picture dictionary with themes that are frequently used in the Foundation Phase. They include scenes from children's everyday lives and the corresponding English and Sepedi/IsiXhosa terms. The second part of the paper therefore focuses on visual representations of gender stereotypes, as opposed to the verbal expressions examined in the preceding section.

On the theme page of "Places and people", we see various people in different professions (cf. Figure 4). Professional roles are often stereotypically associated with one gender. It is therefore worth taking a critical look at them: We see a male police officer, a male doctor, a male dentist, a female cashier, a female nurse, a male postman and a male butcher. In total, we have a 5:2 ratio of men to women. Besides that, the higher status occupations are all portrayed by men (doctor, dentist). Jobs performed traditionally by women are respectively illustrated with female personas (cashier, nurse) This is a problem that is also known from AI systems: "Especially, in widely used language translation systems ML/AI models assign pronouns to professions confirming the gender stereotypes; for example, the models automatically assign he/him pronouns to professions such as doctors and pilots, whereas it assigns she/her pronouns to nurses and flight attendants" (Shrestha and Das 2022: 1). A study of Malaysian, Indonesian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi school textbooks describes the same asymmetry: "The overall findings show that professions attached to female characters are traditional, and lower in prestige and income" (Islam and Asadullah 2018: 14). On the other hand, it is also important that these theme pages must relate to the children's world, otherwise they might regard the dictionary as a 'bad' reference book. This is the well-known problem of usage and authority that Sinclair has already described: "This brings up the question of usage and authority. These concepts must support each other or no-one will respect either of them. If their close relationship breaks down, and authority is not backed up by usage, then no-one will respect it. … Similarly, no-one will respect usage if it is merely an unedited record of what people say and write. … Any successful record of a language such as a dictionary is itself a contribution to authority" (Sinclair 1992). Nevertheless, more inclusive portrayals can be implemented without going against either authority or usage. While certain occupations might still be gender-biased, others certainly have started to see more mixed groups (e.g. doctors are predominantly female in younger age groups (Tiwari et al. 2021: 7). In this way, asymmetries can be reduced and gender role perceptions gradually altered.

Another area where stereotypes are encoded is the gendered assignment of verbs or actions. On the topic page "Things that we do" (Figure 5), we see children involved in various actions: girls reading, dancing, writing, pushing (someone on the swing) and swimming; boys throwing, sitting, giving, catching, kicking, playing, laughing and waving. As these are all gender-unrelated activities, a balanced portrayal of girls and boys would be desirable (boys are assigned 8 activities, girls only 5). Moreover, some children could easily be depicted without any clear gender attribution.

Among the adults it is mainly the helping activities that are attributed to women: Carrying baskets and washing dishes are done by women, while the man is standing in the playground with his hands in his pockets. From today's point of view, the illustrations should be less gender-stereotypical in order to give children a freer idea of role assignments (without being unrealistic). Mohd Faeiz Ikram bin Mohd Jasmani et al. (2011) argue along these lines that overly stereotypical role allocation in textbooks could have very negative impacts; accordingly, I suggest that more conscious and diversified representations could have a positive impact. Mohd Faeiz Ikram bin Mohd Jasmani et al. (2011: 71) point out:

portrayals of stereotypical ideals and ideologies about men and women in the English language textbooks can have lasting consequences. Children and adolescents usually develop their ideas about the world at an early stage and this will last well into their adult lives. The textbooks, by depicting gender bias ideologies, seem to suggest that women have a limited or restricted role to play in a male-dominant society and women, by accepting such a perspective, perceive this view as normal.

5. Concluding remarks

Lexicography is a discipline that (if it wants to produce user-friendly dictionaries) stands at the centre of society. This means that societal values are reflected in dictionaries and that lexicographers have to be aware of changes and adapt their work accordingly, e.g. when it comes to paraphrases of meaning. This is something that Rufus Gouws pointed out early and repeatedly: "In the treatment of any linguistic expression lexicographers should not only look at the linguistic features of that form, but they should also look beyond that at the cultural values it conveys. Taking due cognizance of the culture also implies being aware of specific culture-bound lexical items and suggesting new ways to present and treat them in an optimal way" (Gouws 2020: 4).

In the context of descriptive, corpus-based lexicography, this aspect has been somewhat neglected, as exemplified by OUP's statement above saying that their dictionaries try to reflect and not to dictate language use (Flood 2019). And the results of the empirical analyses presented here can be seen as indicative of gender bias in dictionaries, although this would require much more extensive empirical investigation. In my view, it is not enough to simply observe language use and record it in the dictionary. Dictionaries are made by humans, and if dictionaries are to be different from search engines or other ML or AI tools, they should show a carefully curated selection of language use (cf. Nied Curcio 2020: 200; for the field of ML and AI cf. Caliskan, Bryson and Narayanan 2017; Bolukbasi et al. 2016). As Bergenholtz emphasized, such processes of selection from language use or comments on it have little to do with language policy. Rather, it is a conscious classification that makes dictionaries more helpful (cf. Bergenholtz 2001: 517; Bergenholtz and Gouws 2006: 39-40) and, hopefully, less discriminating.

Critical analyses of already published dictionaries, as shown briefly in section 4, are not ends in themselves. They enable us to learn from the past and to avoid making the same 'mistakes' again in the future. Rufus Gouws once expressed this very well regarding digital lexicography, so the last word here is his:

What should be learned from the past, and this applies to both printed and electronic dictionaries, is to conscientiously avoid similar traps and mistakes, especially in cases where what are now seen as mistakes were then regarded as the proper way of doing things. ... In these new endeavours, we as lexicographers are still bound to make mistakes in the future, but we have to restrict ourselves to making only new mistakes. (Gouws 2011: 18)

Endnotes

1 I thank Samira Ochs for insightful comments on this paper and both reviewers for helpful remarks.

2 My translation of original: "Weiterhin gilt: Besonders im Bereich der sog. kulturellen Wörter, im Bereich der politisch-sozialen Lexik sowie bei den moralisch-ethischen Bezeichnungen machen die allgemeinen einsprachigen Wörterbücher stets auch Identifikationsangebote."

3 My translation of original: "Lexikographie ohne Werturteile und ohne gesellschaftliches Engagement ist ein Unding und darüber hinaus gar nicht möglich. […] Dies gilt jedoch für alle Wörterbücher, nicht nur bei Bedeutungsangaben, sondern auch bei der äußeren und inneren Selektion finden sich Spuren politischer und kulturpolitischer Haltungen."

4 Parts of the following study (section 2 and 3) are already published in (Müller-Spitzer and Rüdiger 2022; Müller-Spitzer and Lobin 2022).

5 https://dictionary.cambridge.org/de/.

6 Duden Bedeutungswörterbuch, Mannheim 1970.

7 Own translation, original: "Der Mann, also 'er', 'zeigt eine akrobatische Beherrschung seines Körpers', 'seine Seele vermag das All zu umfassen' und 'große Wirkung ging von ihm aus'. 'Sie' dagegen 'ist immer adrett gekleidet', 'hat das Baby täglich ausgefahren', 'erwartet mit großer Angst seine Rückkehr' und 'sie sah zu ihm auf wie zu einem Gott'."

8 Helmut Schmid (1995): Improvements in Part-of-Speech Tagging with an Application to German. Proceedings of the ACL SIGDAT-Workshop, Dublin, Ireland: 47-50; https://www.cis.uni-muenchen.de/~schmid/tools/TreeTagger/data/tree-tagger2.pdf.

9 https://pansalb.org/.

References

Barnickel, Klaus-Dieter. 1999. Political Correctness in Learners' Dictionaries. Herbst, Thomas and Kerstin Popp (Eds.). 1999. The Perfect Learners' Dictionary (?): 161-174. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110947021.161 [ Links ]

Benavot, Aaron. 2016 (updated 2022). Gender Bias is Rife in Textbooks. World Education Blog, 8 March 2016 (updated version: 18 April 2022 by Aaron Benavot and and Catherine Jere). https://world-education-blog.org/2016/03/08/gender-bias-is-rife-in-textbooks/ (24 January, 2023)

Bergenholtz, Henning. 2001. Proskription, oder: So kann man dem Wörterbuchbenutzer bei Textproduktionsschwierigkeiten am ehesten helfen. Lehr, Andrea, Matthias Kammerer, Klaus-Peter Konerding, Angelika Storrer, Caja Thimm and Werner Wolski (Eds.). 2001. Sprache im Alltag: Beiträge zu neuen Perspektiven in der Linguistik. Herbert Ernst Wiegand zum 65. Geburtstag gewidmet: 499-519. Berlin/New York: De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110880380 [ Links ]

Bergenholtz, H. and Rufus H. Gouws. 2006. How to Do Language Policy with Dictionaries. Lexikos 16: 13-45. https://doi.org/10.4314/lex.v16i1.51486 [ Links ]

Bolukbasi, Tolga, Kai-Wei Chang, James Zou, Venkatesh Saligrama and Adam Kalai. 2016. Man is to Computer Programmer as Woman is to Homemaker? Debiasing Word Embeddings. arXiv: 1607.06520. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1607.06520

Caliskan, Aylin, Joanna J. Bryson and Arvind Narayanan. 2017. Semantics Derived Automatically from Language Corpora Contain Human-like Biases. Science 356(6334): 183-186. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aal4230 [ Links ]

Chen, Yan, Christopher Mahoney, Isabella Grasso, Esma Wali, Abigail Matthews, Thomas Middleton, Mariama Njie and Jeanna Matthews. 2021. Gender Bias and Under-representation in Natural Language Processing across Human Languages. AIES '21: Proceedings of the 2021 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, May 19-21, 2021, Virtual Event USA: 24-34. New York: ACM (Association for Computing Machinery). https://doi.org/10.1145/3461702.3462530 [ Links ]

Criado Perez, Caroline. 2020. Invisible Women. Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men. London: Vintage. [ Links ]

Dlali, M. 2010. Longman Foundation Phase Bilingual IsiXhosa/English Dictionary. Cape Town: Maskew Miller Longman. https://www.graffitiboeke.co.za/ (7 February, 2023) [ Links ]

Flood, Alison. 2019. Thousands Demand Oxford Dictionaries "Eliminate Sexist Definitions". The Guardian, 17 Sept. 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/sep/17/thousands-demand-oxford-dictionaries-eliminate-sexist-definitions (22 March, 2022)

Fuertes-Olivera, Pedro A. and Sven Tarp. 2022. Critical Lexicography at Work: Reflections and Proposals for Eliminating Gender Bias in General Dictionaries of Spanish. Lexikos 32(2): 105-132. https://doi.org/10.5788/32-2-1699 [ Links ]

Giovanardi, Maria Beatrice. 2020. Open Letter calling on @OxUniPress to change their entry for the word "woman" #SexistDictionary. Change.org. https://www.change.org/p/change-oxford-dictionary-s-sexist-definition-of-woman/u/25841171 (17 March, 2022)

Gouws, Rufus H. 1993. Afrikaans Learner's Dictionaries for a Multilingual South Africa. Lexikos 3: 29-48. https://doi.org/10.5788/3-1-1099 [ Links ]

Gouws, Rufus H. 2001. Der Einfluß der neueren Wörterbuchforschung auf einen neuen lexikographischen Gesamtprozeß und den lexiko graphischen Herstellungsprozeß. Lehr, Andrea, Matthias Kammerer, Klaus-Peter Konerding, Angelika Storrer, Caja Thimm and Werner Wolski (Eds.). 2001. Sprache im Alltag: Beiträge zu neuen Perspektiven in der Linguistik. Herbert Ernst Wiegand zum 65. Geburtstag gewidmet: 521-531. Berlin/New York: De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110880380 [ Links ]

Gouws, Rufus H. 2011. Learning, Unlearning and Innovation in the Planning of Electronic Dictionaries. Fuertes-Olivera, Pedro A. and Henning Bergenholtz (Eds.). 2011. e-Lexicography. The Internet, Digital Initiatives and Lexicography: 17-29. London/New York: Continuum. [ Links ]

Gouws, Rufus H. 2020. Metalexicography, Dictionaries and Culture. Lexicographica 36(2020): 3-9. https://doi.org/10.1515/lex-2020-0001 [ Links ]

Gouws, Rufus H. 2022. Dictionaries as Instruments of Exclusion and Inclusion: Some South African Dictionaries as Case in Point. Lexicographica 38(1): 39-61. https://doi.org/10.1515/lex-2022-0003 [ Links ]

Heyer, Gerhard, Uwe Quasthoff and Thomas Wittig. 2006. Text Mining: Wissensrohstoff Text: Konzepte, Algorithmen, Ergebnisse. IT Lernen. Herdecke: W3L. [ Links ]

Hidalgo Tenorio, Encarnación. 2000. Gender, Sex and Stereotyping in the Collins COBUILD English Language Dictionary. Australian Journal of Linguistics 20(2): 211-230. https://doi.org/10.1080/07268600020006076 [ Links ]

Hu, Huilian, Hai Xu and Junjie Hao. 2019. An SFL Approach to Gender Ideology in the Sentence Examples in the Contemporary Chinese Dictionary. Lingua 220: 17-30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2018.12.004 [ Links ]

Islam, Kazi Md Mukitul and M. Niaz Asadullah. 2018. Gender Stereotypes and Education: A Comparative Content Analysis of Malaysian, Indonesian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi School Textbooks. PLOS ONE (Public Library of Science) 13(1): e0190807. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190807 [ Links ]

Kaplan, Steven M. 2020. Boys Will Be Boys: An Example of Biased and Exclusive Usage. Lexicographica 36: 205-223. https://doi.org/10.1515/lex-2020-0011 [ Links ]

Kotthoff, Helga and Damaris Nübling. 2018. Genderlinguistik: Eine Einführung in Sprache, Gespräch und Geschlecht. Narr Studienbücher. Tübingen: Narr Francke Attempto. [ Links ]

Kunkel, Kathrin. 2004. Die Frauen und der Duden - der Duden und die Frauen. Eichhoff-Cyrus, Karin M. (Ed.). 2004. Adam, Eva und die Sprache : Beiträge zur Geschlechterforschung: 308-315. Mannheim: Dudenverlag. [ Links ]

Mabule, M. 2010. Longman Foundation Phase Bilingual Sepedi/English Dictionary. Cape Town: Maskew Miller Longman. (7 February, 2023) [ Links ]

McGarty, Craig, Vincent Y. Yzerbyt and Russell Spears. 2002. Social, Cultural and Cognitive Factors in Stereotype Formation. McGarty, Craig, Vincent Y. Yzerbyt and Russell Spears (Eds.). 2002. Stereotypes as Explanations: The Formation of Meaningful Beliefs about Social Groups: 1-15. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511489877.002 [ Links ]

Mohd Faeiz Ikram bin Mohd Jasmani, Mohamad Subakir Mohd Yasin, Bahiyah Abdul Hamid, Yuen Chee Keong, Zarina Othman and Azhar Jaludin. 2011. Verbs and Gender: The Hidden Agenda of a Multicultural Society. 3L: Language, Linguistics and Literature: The Southeast Asian Journal of English Language Studies 17 (Special issue): 61-73. [ Links ]

Müller-Spitzer, Carolin and Henning Lobin. 2022. Leben, lieben, leiden: Geschlechterstereotype in Wörterbüchern, Einfluss der Korpusgrundlage und Abbild der sprachlichen ‚Wirklichkeit'. Diewald, Gabriele and Damaris Nübling. 2022. Genus - Sexus - Gender: 33-64. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110746396-002 [ Links ]

Müller-Spitzer, Carolin and Jan Oliver Rüdiger. 2022. The Influence of the Corpus on the Representation of Gender Stereotypes in the Dictionary. A Case Study of Corpus-based Dictionaries of German. Klosa-Kückelhaus, Annette, Stefan Engelberg, Christine Möhrs and Petra Storjohann (Eds.). 2022. Dictionaries and Society. Proceedings of the XX EURALEX International Congres: 129-141. Mannheim: IDS Verlag. https://euralex.org/publications/the-influence-of-the-corpus-on-the-representation-of-gender-stereotypes-in-the-dictionary-a-case-study-of-corpus-based-dictionaries-of-german/ (21 December, 2022) [ Links ]

Nied Curcio, Martina. 2020. Kulturell geprägte Wörter zwischen sprachlicher Äquivalenz und kultureller Kompetenz. Am Beispiel deutsch-italienischer Wörterbücher. Lexicographica 36(2020): 181-204. https://doi.org/10.1515/lex-2020-0010 [ Links ]

Nied Curcio, Martina. 2022. Dictionaries, Foreign Language Learners and Teachers. New Challenges in the Digital Era. Klosa-Kückelhaus, Annette, Stefan Engelberg, Christine Möhrs and Petra Storjohann (Eds.). 2022. Dictionaries and Society. Proceedings of the XX EURALEX International Congres: 71-84. Mannheim: IDS Verlag. https://euralex.org/wp-content/themes/euralex/proceedings/Euralex%202022/EURALEX2022_Pr_p71-84_Nied-Curcio.pdf (21 December, 2022) [ Links ]

Nübling, Damaris. 2009. Zur lexikografischen Inszenierung von Geschlecht. Ein Streifzug durch die Einträge von Frau und Mann in neueren Wörterbüchern. Zeitschrift für germanistische Linguistik 37(3): 593-633. https://doi.org/10.1515/ZGL.2009.037 [ Links ]

Ripfel, M. 1989. Die normative Wirkung deskriptiver Wörterbücher. Hausmann, Franz Josef, Oskar Reichmann, H.E. Wiegand and Ladislav Zgusta (Eds.). 1989. Wörterbücher. Ein Internationales Handbuch zur Lexikographie / Dictionaries. An International Encyclopedia of Lexicography / Dictionnaires. Encyclopédie internationale de lexicographie. Volume 5.1: 189-207. Handbücher zur Sprach- und Kommunikationswissenschaft. Berlin/New York: De Gruyter. [ Links ]

Shrestha, Sunny and Sanchari Das. 2022. Exploring Gender Biases in ML and AI Academic Research through Systematic Literature Review. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence 5. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frai.2022.976838 (24 January, 2023) [ Links ]

Sinclair, John. 1992. Introduction. Collins Cobuild English Language Dictionary, xv-xxi. London: HarperCollins. [ Links ]

Singh, Vivek K., Mary Chayko, Raj Inamdar and Diana Floegel. 2020. Female Librarians and Male Computer Programmers? Gender Bias in Occupational Images on Digital Media Platforms. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 71(11): 1281-1294. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24335 [ Links ]

Tiwari, Ritika, Angelique Wildschut-February, Lungiswa Nkonki, René English, Innocent Karangwa and Usuf Chikte. 2021. Reflecting on the Current Scenario and Forecasting the Future Demand for Medical Doctors in South Africa up to 2030: Towards Equal Representation of Women. Human Resources for Health 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-021-00567-2 [ Links ]

Westveer, Thom, Petra Sleeman and Enoch O Aboh. 2018. Discriminating Dictionaries? Feminine Forms of Profession Nouns in Dictionaries of French and German. International Journal of Lexicography 31(4): 371-393. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijl/ecy013 [ Links ]

Wiegand, Herbert Ernst. 1995. Der kulturelle Beitrag der Lexikographie zur Umgestaltung Osteuropas. Lexicographica 11: 210-218. [ Links ]