Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Scientia Militaria: South African Journal of Military Studies

On-line version ISSN 2224-0020

Print version ISSN 1022-8136

SM vol.51 n.2 Cape Town 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.5787/51-2-1416

ARTICLES

The Bond van Oudgeïnterneerdes en Politieke Gevangenes as a Direct and Long-Lasting Social Manifestation Related to the Internment Policy of the Union of South Africa, 1946-1985

Potsdam University

ABSTRACT

During the Second World War, the Union of South Africa implemented emergency regulations, including an internment policy, to curb anti-war efforts within South Africa. These regulations and the internment policy affected one of the biggest anti-war organisations, the Ossewabrandwag ("Oxwagon Sentinel"), and many of its members were detained during the war in internment camps. In 1946, the Bond van Oudgeïnterneerdes en Politieke Gevangenes (freely translated as "the Association of Former Internees and Political Prisoners") was formed by individuals, mostly Ossewabrandwag members, who were interned in South African internment camps. Using the Bond van Oudgeïnterneerdes en Politieke Gevangenes collection that forms part of the Ossewabrandwag Archive, this article provides a brief historical background to the Bond van Oudgeïnterneerdes en Politieke Gevangenes. Some key themes are discussed, and the focus is on the organisation, and the possible effect of the organisation on its members is explored by framing nostalgia or nostalgic longing as central to its existence. By considering the Bond van Oudgeïnterneerdes en Politieke Gevangenes as a direct and long-lasting social manifestation related to the internment policy of the Union of South Africa, the ongoing study - from which this article derives - constitutes a first attempt at exploring the Bond van Oudgeïnterneerdes en Politieke Gevangenes and understanding its role in the larger picture of the South African Second World War experiences and memories.

Keywords: Bond van Oudgeïnterneerdes en Politieke Gevangenes, BOPG, Ossewabrandwag, Memorable Order of Tin Hats, Internment, Emergency Regulations

Introduction and Contextualisation

The Bond van Oudgeïnterneerdes en Politieke Gevangenes (BOPG) was an organisation founded by individuals who were interned in South Africa during the Second World War.190Most of its members were former Ossewabrandwag (OB) members, and most also formed part of the subversive and activist wing of the OB known as the Stormjaers ("Storm Troopers"). The BOPG has not been analysed within the OB historiography previously, which is surprising given the growing number of academic works on the OB over the past few years.191 Part of the reason why the BOPG has been missing from historiography until now is the position of the BOPG on the edges of mainstream historiographical concerns and the fact that traces of the BOPG in broader society are minimal, with all of its archival documents forming part of the OB Archive (OBA).

As one of the social manifestations that can be traced back directly to the OB, the BOPG had a protracted influence on the lives of its members, and existed until 1985 - more than thirty years after the OB had been disbanded officially. Hans van Rensburg, the former leader of the OB, remained honorary president of the BOPG until his death. This is perhaps one of the key indicators of the inseparability of the BOPG and the OB. It is safe to argue that the BOPG would never have existed without the OB. Two of the most authoritative historical texts on the OB, by Christoph Marx and Piet F van der Schyff respectively,192scarcely mention the BOPG. Apart from a few sporadic references to the BOPG in the works of Albert Blake,193 Charl Blignaut, and Dawid Olivier,194 the current study is the first to delve into the inner workings of the organisation. Much like the argument by Neil Roos that the 'memory of war service' bound South African (SA) Second World War veterans 'together until their very old age',195 mostly in the form of various veterans' organisations, such as the Memorable Order of Tin Hats (MOTHs), the BOPG provided the same opportunity for former internees and political prisoners.

The current study analyses one of the long-lasting social manifestations of the emergency regulations of the Smuts government by highlighting the BOPG as an organisation. Other studies have already looked at, or in some cases briefly touched upon, the internment of OB members during the Second World War,196 and the effect of the emergency regulations by the Union government on South Africa in general and on the OB specifically, has also been analysed from various social angles.197 The study builds on previous studies by asking the following question:

What were the long-term social consequences of the emergency regulations, and which role did the BOPG play after the dissolution of the OB in the lives of persons directly affected by the South African internment policy during the Second World War?

By utilising both the official BOPG newsletter, Dankie, along with the large number of interview transcripts that now forms part of the OBA,198 and BOPG minutes and reports, the current study follows a socio-historical approach by highlighting the opinions of contemporaries to convey an overall picture of the organisation. As Patrick Finney notes, activities, such as recording interviews and testimonies on tape, '[are] a rather literal way of seeking to prolong the era of living memory beyond the life-span of participants'.199In the case of the BOPG, it is however interesting to note that this phenomenon is not limited to veterans and victims of war circumstances, such as holocaust survivors. In South Africa, the climate existed for former violent individuals who actively participated in acts of sabotage to prolong the era of living memory beyond the lifespan of those who were directly involved.

OB members formed camaraderie within the organisation, built on the idea that they would 'never abandon' their comrades, especially those held as internees and political prisoners, 'in their struggle'.200 This sense of camaraderie took two specific forms. Firstly, they wanted to "help" fellow Afrikaners, and secondly, they wanted to "protect" them. These two themes, "to help" and "to protect", are visible early in the OB policy, and can be observed in some of the official pamphlets of the organisation, such as Die OB: Vanwaar en Waarheen.201 These themes are, however, also clearly visible in the long-term social consequences of the emergency regulations, as they had a lasting power that outlived the demise of the OB, and were, to a certain extent, adopted by the BOPG. These two themes are constantly highlighted in this article.

The article firstly provides a brief historical background to the BOPG. Secondly, some key themes and focusses within the organisation are discussed. It is also illustrated how the BOPG tried to take complete ownership of the history of the SA internment camps during the Second World War. Finally, the influence of the organisation on its members is explored by highlighting nostalgia or nostalgic longing as central to the existence of the BOPG.

Brief Description of the Bond van Oudgeïnterneerdes en Politieke Gevangenes

Four years after the last political prisoners had been released, the final official retreat of the OB was held in Bloemfontein. During this retreat, on 23 August 1952, the decision was made to officially disband the OB in its current form,202 and to transform the organisation into 'a comprehensive republican movement'.203 More than a year after this retreat, on 10 September 1953, the OB was effectively transformed into the Republikeinse Bond ("Republican League") under the leadership of former OB Assistant Leader JA Smith. The Republikeinse Bond only existed for a few months, and on 16 January 1954, it was also dissolved due to a lack of funds.204

With the official demise of the OB, and later the Republikeinse Bond, several organisations and sections that had been connected to the OB were also disbanded. This included the OB-Boerejeug ("OB Youth League") and the OB-Vroueafdeling ("OB Women's Section"). The OB members, however, came up with other ways to keep the ideals of the OB and the friendships formed through the organisation alive. The two most prominent manifestations were the OB-Vriendekring ("OB Circle of Friends"),205 and the Bond van Oudgeïnterneerdes en Politieke Gevangenes (BOPG).206 On 22 April 1946, six years before the dissolution of the OB, the BOPG was officially established.207 Although this organisation was already established before the dissolution of the OB, it did not die with the OB.

The BOPG decided from the outset that membership should be limited to those detained in internment camps and prison cells. Within the organisation, there were two forms of membership: 'full membership' and 'honorary membership'. Full membership was for individuals physically detained in camps, prisons, or police cells. Those who enjoyed 'honourable distinction' because of their 'close association' with such individuals were also considered members - albeit only honorary members.208 Members and honorary members enjoyed almost the same benefits, except that only full members could serve on the council of the organisation. The requirements for 'honorary members' were much more comprehensive. Honorary members had to fall into any one of the following three groups:

• Individuals who fought against war participation during the war years and who, 'regardless of the greatest danger and persecution', persevered outside the camps and prisons;

• Individuals who cared for and assisted the families of internees and refugees; and

• Individuals who participated in the Afrikaner Rebellion of 1914.209

The honorary member system allowed Hans van Rensburg, the former leader of the OB, for example, to serve as the honorary president of the BOPG, even though he was never detained in any camp or prison.210 Several women were also visible in the activities of the BOPG, even though no women were interned during the war. Women played an indirect role in the BOPG and were prominent in social activities, such as dinners and wreath-laying ceremonies. Although the role of women within the OB has been analysed thoroughly in the past, the role played by women in the BOPG provides a perfect opportunity for future research on the organisation.

The BOPG was aware of the continuous decline in membership and, as a result, the need to 'bring comrades together in a close unit' was emphasised.211 In 1961, the future of the BOPG was already a concern, mainly because most members were already seniors at the time. It was proposed that BOPG members let their sons join the organisation.212 This involvement would be subject to several requirements:

• An age requirement (the specific age was never stipulated);

• A character test (mainly to test prospective members' 'Afrikanerskap [Afrikanership]'); and

• A knowledge test, which would be based on knowledge of the official publication of the BOPG, Agter Tralies en Doringdraad (1953).213

The proposal never materialised. Nevertheless, this does not indicate that fears surrounding the legacy and future of the BOPG disappeared. This matter posed a serious concern for members, and validly so, as the BOPG was officially disbanded in 1985. However, in its almost forty years - especially after radical changes to membership requirements, which became less strict and formal as time went by - several former OB members joined the BOPG. The experience of being detained and interned during the war, and for many simply belonging to the OB, remained a part of their identity, one that could not be suppressed.

The BOPG continued to affect members' lives for about four decades. For members of the organisation, the BOPG was defined as 'a group of people among whom the suffering of the past has forged a camaraderie'.214 One of the main practical aims of the BOPG was to provide an opportunity for those who had been interned and detained as political prisoners 'to meet up from time to time' to commemorate and talk about the 'the pain and the joy of the struggle' during the Second World War.215 The function of the BOPG has been described as 'being a leaven for our volkslewe ["national life"]', referring, of course, to Afrikanerdom.216 This function resonated with the early objectives of the OB, which included:

• The 'expansion' of volkslewe';

• '[P]reserving the language and tradition of the Boer people';

• '[P]rotection and promotion of all Afrikaner interests'; and

• [U]niting all Afrikaners'.217

This overlap between the function of the BOPG and some of the early objectives of the OB was just one of the ways in which the BOPG experienced nostalgia for the heyday of the OB, and by which the long-lasting connection between these two bodies was made visible.

The goals of the BOPG, mainly contained in the constitution of the organisation and which are discussed later, also served as a lens through which members' greatest needs and concerns were viewed. In the early years of the BOPG, the need for a sense of unity was among the most important points of discussion. In 1947, three of the most important needs among members were:

• The need for a badge or an emblem for the BOPG;

• A conference at which the necessary rules, regulations, and constitutional matters could be discussed; and

• A dinner to rekindle old friendships.218

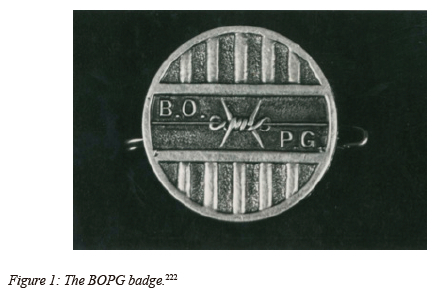

Regarding the need for a badge, one of the main requirements for the design was that it had to include themes directly related to the internment camps and prisons. One suggestion was that the coat of arms had to depict 'the barbed wire of the camps in the middle and the bars of the prisons on either side'.219 This emphasis on themes directly relating to internment and internment camps shows that the BOPG members perceived their shared experience as internees and political prisoners as the basis on which this new community rested and was formed. This is proved even further by the decision made by the BOPG to limit the number of badges that were physically produced, and by issuing them only to a 'limited number of persons'.220 This move not only formed a community but also added to the perceived prestige of belonging to the BOPG. The final coat of arms was approved at the BOPG conference on 4 October 1947 (see Figure 1).221

Adding the motifs of barbed wire and prison bars to the official BOPG coat of arms and the badge ensured that the effects of the emergency regulations and internment policy were physically visible. Because the BOPG was founded precisely for those affected by the emergency regulations and internment policy, it is obvious that the themes of barbed wire and prison bars would frequently appear within the activities of the organisation. In addition to the coat of arms and the badge, which physically depicted these motifs, the BOPG also decided to name their publication on the history of the camps Agter Tralies en Doringdraad ("Behind Bars and Barbed Wire"). Once again, this was seen as a tribute to how they were affected by the introduction of the internment policy by the Smuts government. The cover of the publication also depicted the motifs of barbed wire and prison bars (see Figure 2). As regards the second and third needs, the BOPG members wanted to discuss 'important matters' regarding the establishment and role of the organisation during a conference in Pretoria, and a dinner was arranged because 'everyone wants to revive old friendships'.223

Key Themes within the Bond Van Oudgeïnterneerdes en Politieke Gevangenes: "To Help" and "To Protect"

As already mentioned, the objectives set out in the constitution of the BOPG offer the historian a unique lens through which to view the greatest needs and concerns of the members of the organisation. The official constitution of the BOPG set out four objectives for the organisation.

• To maintain and further develop brotherhood and friendship;

• To help fellow members financially and to support them to obtain employment;

• To raise funds for assisting members financially; and

• To 'record the history of internment and the internment camps' of the Second World War.225

One immediately apparent aspect is that the ideals of helping and protecting were again prominent, and all four objectives touched upon one or both ideals. The ideals of helping and protecting, which so prominently formed part of the OB, therefore still emerged years after the OB no longer existed.

By assisting members in obtaining a fixed income, the BOPG protected those individuals from financial insecurity. For example, funds were collected for 'aid purposes' to assist fellow members financially. Initially, these funds were channelled to the OB Noodhulpfonds ("Emergency Relief Fund"), but later it was mainly directed towards the recording of the history of the internment and the protection of important documents. The BOPG also tried to provide help and assistance by offering legal advice to members. For example, the secretary of the BOPG appealed to all persons who were found guilty of any political charge between 1939 and 1945 to forward information to the BOPG. This request was made because 'there is a possibility that the authorities may lift or remove any disadvantage or disqualification (legal impediment) that exists as a result of such a conviction to our benefit'.226 All of these initiatives pointed towards the role of the BOPG in helping fellow members, mainly by protecting them from financial insecurity.

Many former internees and political prisoners decided not to join the BOPG. The reasons for this varied from individual to individual. Some of the most prevalent reasons were the acute need to leave the past in the past. FR Bartman, arrested and detained in 1942 for setting fire to a timber yard in Pretoria as an act of sabotage,227 explicitly stated that the BOPG members were 'living in the past'.228 Another former internee, Sven Eklund, who was interned in the Koffiefontein camp during the war, was also opposed to the idea of the BOPG, and believed that there was 'no need' for such an organisation.229 Despite the opinions of former internees and political prisoners, such as Bartman and Eklund, it is obvious that the BOPG played a prominent role in the lives of some of these individuals who were affected by the internment policy.

The last objective, namely to publish a history of the camps, particularly occupied the activities of the BOPG. The decision that the history of the internment camps should be drawn up was already made at the first general meeting of the BOPG in 1946.230 This goal was carried through to the very last days of the BOPG, of which the establishment of the OBA is surely the greatest physical remnant. This article argues that the most significant role that the BOPG played in the lives of affected persons was that it provided the opportunity to preserve a kind of own history of the camps - in publication and archive - for future generations. By doing this, the BOPG not only offered help and protection to affected persons but also provided an opportunity for them to protect the history in which they were directly involved.

'Our History'

The BOPG took the writing of the history of the Second World War internment camps particularly seriously, and tried to take full ownership of the history of this phenomenon, even referring to it as 'our history'.231 Books conveying the "correct type" of history232were regularly promoted in Dankte, the official BOPG newsletter,233 for example:

• Magda Boyce's Root Verraad (1949);

• Hans van Rensburg's Their Paths Crossed Mine (1956);

• Hendrik van Blerk's En Drie Maal Kraai Die Haan (1968); and

• FW Quass's Tweede Rebellie (1975).

The tendency to propagate the "correct type" of history is not unique to the BOPG. On a much smaller scale, this tendency could also be seen within the OB structure in 1944. For example, in the official Boerejeug circular of 14 June 1944, all members were encouraged to purchase AJH van der Walt's 'n Volk op Trek (1944). Just as the above cases, this book by Van der Walt tells the preferred version of history, seeing that it was written by the then OB secretary of the Grootraad ("Grand Council").234

However, unique to the BOPG is the overemphasis by the organisation on the "correct type" of history. This was done by promoting certain books and harshly criticising any publications that were, according to the BOPG, 'blatant lies'.235 Such publications were regularly identified and criticised in Dankie, and usually came with a warning to its members not to buy or read such books. Most prominent were:

• Hans Strydom's Vir Volk en Führer (1983); and

• George Cloete Visser's OB: Traitors or Patriots? (1976).236

The criticism against such books was conveyed in Dankie and in numerous interviews with BOPG members, who regularly stated their disdain for such publications. One BOPG member, Heimat Anderson, even consulted a lawyer about the possibility of suing Visser over statements in his book, OB: Traitors or Patriots?237 In the December 1983 edition of Dankie, the BOPG also encouraged members to come forward with any documents or information that could prove Strydom's publication wrong.238 Other books that retold the version of history preferred by the BOPG were marketed to BOPG members to teach 'children and grandchildren our own history'.239

By promoting certain publications and rejecting others, the BOPG members wanted to take full ownership of what they perceived to be "their own history". This objective was further realised by putting together a collection of works on the history of the camps, which would eventually take the form of a published book. Already in the planning phase of the book, every effort was made to ensure that it is as comprehensive as possible: 'If the book is to have value, then it must contain everything.'240 Emphasis was also placed on 'facts'.241 During the planning phase, it was repeatedly stated that no writing would be allowed in the book if it were not based on facts. During the writing process, contributors were reminded to focus on 'facts and dates', and that 'guessing and opinions' should not be part of the writing process.242

It is also clear that the BOPG wanted to gain as much attention as possible through the publication. The editors, therefore, faced a problem: on the one hand, the publication had to contain 'everything' related to the history of the camps,243 but on the other hand, it must not be 'dry reading material'. As OL Nel, a prominent member of the editorial team, put it:

If we compile a history of the camps and prisons, then, of course, it must contain everything, and if it includes everything, it will be rather dry reading material for the outsider, and the book will never be considered 'popular reading material.' In other words: I doubt very much whether the book will be a financial success.244

The above quote illustrates that the BOPG ranked publishing their version of the events higher than any possible financial gains from such a publication.

The BOPG wanted to exercise absolute control over every aspect of the history of the internment camps. In the 7 January 1948 edition ofDie OB, the official newspaper of the OB, a former internee wrote an article in which he encouraged other internees to record 'interesting incidents from internment life' as part of a writing competition.245 This article was written and published without the permission of the BOPG Council, and shortly after it had appeared, the secretary of the BOPG wrote a stern letter to the editor of Die OB:

According to the constitution of the BOPG, no one may do or say anything regarding the BOPG except for members of its Union Council [...] I would appreciate it if, in the future, you would send such matters as the article I am discussing to me first for approval before posting them [in Die OB]246(Author's own translation)

Some former internees and political prisoners raised serious and valid concerns over the objectivity of such a book, especially because it would be written so soon after the events had taken place. Sven Eklund, a former Koffiefontein internee, maintained that the book had to be postponed until 'things are clearer in an extended perspective'.247 Hendrik van den Berg, who was also interned in the Koffiefontein camp, believed that ex-internees only had to be involved in 'gathering the necessary facts' and that 'the time is by no means yet ripe' to publish such a book.248 GPJ Trümpelmann, who was the camp leader at the Leeuwkop internment camp,249 also believed that the time was 'not yet ripe' for such a publication. Trümpelmann's opinion was that the authors of such a publication would not have been able to take the right perspective a mere two years after the war: 'For perspective, distance is necessary, and none of us can have that at the moment.'250

When ex-internees revealed such opinions about the compilation of a history of the camps, it seemed that the views of other BOPG members around them changed. These individuals were often labelled 'anti-Afrikaner', 'more German than Afrikaner', or even 'pro-English'.251 In an article about Trümpelmann, he is described by one of the BOPG members as 'always a German and never an Afrikaner'. Furthermore, he was also branded as 'never pro-Afrikaans' and that he 'prefers English over Afrikaans' - a bizarre remark seeing that all Trümpelmann's correspondence and writings in the OBA is in Afrikaans.252Anyone, even those who shared the experience of being detained under the emergency regulations during the war, could therefore be ostracised by the BOPG members if he or she deviated from the opinion of the wider group.

Despite the opposition of certain members, the BOPG continued organising the publication of the book, and in 1953, the BOPG published Agter Tralies en Doringdraad. The publication of this book can be considered a climax in the existence of the BOPG precisely because it fulfilled one of its four main objectives (i.e. to record the history of South Africa's Second World War internment camps). The book was published under the impression that it was 'the truth' and that no information in the book was open to any interpretation.253 This pointed once again to the idea that the BOPG wanted to exercise control over the history of the camps.

The BOPG used this book as an attempt to take ownership of the history in which they were directly involved by passing on their version of events to future generations. The history of the camps was also used to emphasise the perceived sacrifice of those who were interned and arrested. The internees and political prisoners were framed as innocent victims of the emergency regulations and the war effort by the Union government: 'Children of a conquered people have ... been put into prisons and camps, without trial, [and] without any charges being brought against them .. ,'254

This depiction of internees and political prisoners as innocent martyrs is not new. Depicting such individuals in this manner is also apparent in the official anthem of the BOPG, "Voorwaarts":

Oor die vlakte, oor die rante, oor riviere, dal en veld

Ruis die stem van duisend helde wat geveg het teen geweld

Wat hul lewe het geoffer vir die vryheid van ons land

[Forward

Over the plains, over the ridges, over rivers, valleys and fields, Resounds the voice of a thousand heroes who fought against violence, Who offered their lives for the freedom for our country] (Author's own translation)

Strangely, the BOPG framed its members as 'heroes' who had 'fought against violence', referring to their opposition to active participation by the Union of South Africa in the war.255 Ironically, several of these individuals were involved in numerous acts of violence to sabotage the war effort by the government. This warped and entangled idea of presenting the internees and political prisoners as both heroes and victims is seen throughout Agter Tralies en Doringdraad. The long-lasting effect of emergency regulations issued by the Union government on the OB as an organisation and on its members, therefore, pointed to a dualistic character, one with two sides that formed a unity, despite being directly opposed to each other. On the one hand, unity, helpfulness, and camaraderie were embodied; on the other hand, themes such as martyrdom, despair, and bitterness emerged. This juxtaposition was detectable within the BOPG too. Pride was often entangled with martyrdom. In the correspondence between BOPG members and in interviews conducted with former internees and political prisoners, camaraderie and togetherness were often juxtaposed with despair and bitterness.256 This was also visible in several editions of Dankie.

Concluding the section on the BOPG planning and publishing Agter Tralies en Doringdraad, the historian Dawid Olivier's take on the book perhaps provides the best summary. Agter Tralies en Doringdraad is, in its true essence, a 'work of remembrance',257covering numerous aspects of internment and life as a political prisoner in South Africa during the Second World War. For the BOPG, however, their remembrance project and goal of preserving the history of the camps did not end with the publication of Agter Tralies en Doringdraad.

The members not only longed for the social aspect of the OB years but there were also constant efforts to collect memories of the internment experience. The members nostalgically collected certain physical relics of camp life. In Dankie of December 1965, for example, one member asked whether any fellow members still had a £1 camp coin so that he could complete his collection.258 The BOPG also used Dankie to appeal to members to send objects related to the internment camps during the Second World War for permanent preservation.259 With the establishment of the OBA at the Potchefstroom University for Christian Higher Education (PU for CHE, now part of the North-West University [NWU]), the need to preserve physical remnants only increased. Dankie also regularly published articles in which contemporaries were encouraged to send documents and other historical pieces to the archival department of the university.260

On 9 October 1976, the BOPG decided that - if the BOPG were to dissolve - all assets remaining would be transferred to the PU for CHE.261 These assets would be used exclusively for 'the preservation, housing, exhibition, maintenance, expansion, improvement, insurance and protection of the Ossewa-Brandwag [sic] Archive'.262 By making this decision, and by transferring these assets to the PU for CHE, the BOPG directly contributed to protecting some of the remnants of the OB, the BOPG, and the internment camps.

By 12 October 1985, the bond had R9 935,09 in fixed assets and R240,35 in a current account. The management requested that members donate money because the BOPG 'does not want to leave less than R10 000 to the archive'.263 The total amount transferred to the PU for CHE was never officially recorded, but it amounted to around R10 000. These funds were mainly used for the improvement and expansion of the archive. It is therefore important to consider that the BOPG succeeded, to a certain extent, in keeping the history and memory of the OB, the BOPG, and the internment experiences of various members alive. With the death of the last prominent BOPG members, all documents and collections related to the OB and the BOPG were handed over to the PU for CHE library for safekeeping.264

The BOPG was officially disbanded on 12 October 1985.265 For about forty years, the organisation played a role in the lives of those affected by the internment policy. The four objectives of the organisation have undoubtedly been achieved.266 As regards the first objective, namely the preservation and cultivation of brotherhood, the BOPG contributed to the bringing together of several Afrikaners. In a sense, the BOPG continued with the early objective of the OB, namely the bringing together of contemporaries. In this sense, the BOPG has kept alive the friendships of a handful of people who were bound together by one shared experience. The second objective, namely to offer help and stimulate employment among members, was already realised in the early years of the BOPG, sometimes on a small scale (such as legal advice) and sometimes on a larger scale (by forming a community where most members stumbled through the same employment obstacles). The third objective, fundraising for relief purposes, largely occupied the early years of the existence of the BOPG, especially when the emergency relief fund was still in existence. However, the greatest success of the BOPG, if one measures the organisation against its own goals, lies in the realisation of their fourth goal, the effort to protect the history of the internment and camps for future generations.

Although the BOPG publication Agter Tralies en Doringdraad can be described as a subjective retelling and a contemporary source rather than as a history book, the work still offers a glimpse of the influence the emergency regulations of the Union government had on internees and political prisoners.

The most significant role that the BOPG played in helping those affected by the internment policy is that the association provided the opportunity to preserve the history of the camps for future generations, not only through the publication of Agter Tralies en Doringdraad but also by the contributions made to the OBA. This allowed affected persons to protect the remnants of history within which they were directly involved. More importantly, for the historian, however, is the fact that the documents in the OBA not only contain what the BOPG termed the "correct type" of history but also that they provide an opportunity to understand not only the OB better but all its affiliated organisations - including the BOPG.

Nostalgia and the Bond van Oudgeïnterneerdes en Politieke Gevangenes

The BOPG was an organisation born out of the SA wartime internment experiences, but to a large extent, also born out of the OB. By implication, it was thus an organisation with nostalgic tendencies, a community built on members' shared past. Nostalgia operated both on individual and societal level, helping to create links between the individual and the group.267 Much like veterans' organisations, such as the MOTHs, represented 'a response to a post-war society that neither understood nor adequately acknowledged veterans' experience',268 the mere establishment of the BOPG was an indication that former internees and political prisoners craved camaraderie with those with whom they shared experiences during the war.

The establishment of the BOPG allowed several individuals affected by the internment policy to create a community where this experience formed a central point. As time went by, another mutual link between these individuals, namely their OB membership, also became apparent. Could it be argued that nostalgia or nostalgic longing might have been the linchpin that enabled the BOPG to exist for almost forty years? As already pointed out, the role of the BOPG in establishing the OBA shows that the organisation and its members perceived the heyday of the OB as a phenomenon worth protecting. Nostalgic reminiscences of the OB days thus contributed to the need felt by the BOPG to create the OBA and to ensure its survival for future generations.

For some, the OB represented social contact and a community of like-minded individuals. This social aspect is seen in the numerous events hosted by various OB commandos across the country during the war. Events hosted by the OB included folk festivals,269 dinners, wreath-laying ceremonies at monuments, camps, and hosting braais ("barbecues").270Social events were such a characteristic part of the OB during its prime that a 1941 morale report by the Union Defence Force reported, 'the different branches of the Ossewa-Brandwag [sic] are organising 'braaivleisaande' [barbecue evenings] and various other social functions' which were perceived with some envy by troops who mentioned in letters, 'they have nothing to cheer them up'.271 Social events were thus an intrinsic part of the OB wartime experience. By the 1970s, many former OB members who had not been interned and who had not been affected directly by the internment policy had joined the BOPG.272 The BOPG was thus something more than merely an organisation for former internees and political prisoners; it also represented a way in which the social aspects, the cohesion, the camaraderie, and the togetherness of the heyday of the OB could be relived nostalgically or - in a certain sense -even be continued.

The BOPG also arranged various social events, such as camps, picnics, formal dinners, and braais. Invitations to these events, such as the one depicted in Figure 3, were regularly published in Dankie.274 These invitations sometimes emphasised that the former leader of the OB, Van Rensburg, would be in attendance, possibly because Van Rensburg was closely associated with the prime of the OB. At other events, such as formal dinners

The BOPG also arranged various social events, such as camps, picnics, formal dinners, hosted by the BOPG, OB symbols and icons were visible and formed an essential part of the social event (see, for example, Figure 4).

Social events organised by the BOPG thus created a space where BOPG members could reminisce about the blooming period of the OB, a period characterised by social events to attain some level of unity in Afrikanerdom. Nostalgia and nostalgic longing typically encapsulate a slanted view of the past, in which only the positive aspects are remembered and longed for.276 What is interesting in the case of the BOPG is that, despite this apparent nostalgic longing for the positive experiences of the OB days, there was also an inherent link with the harsh realities of being interned and incarcerated during the war, an experience that was so intrinsic to the BOPG that its entire foundation, name, and existence reflected it. This harsher side of the past was too traumatic for some former internees and political prisoners, such as Bartman and Eklund,277 to become actively involved in the BOPG and to be swept up in the general nostalgia. Despite this, the BOPG successfully created safe spaces where numerous former OB members could reminisce.

The OB is often cast in a strictly political light, especially because of the link between the organisation and acts of sabotage during the war. It is however important to note that the OB meant many things to its members. The experiences of members when the OB was in its prime varied greatly not only from individual to individual but also from one phase to the next. These varied experiences are perfectly articulated by HL Pretorius, a former internee and political prisoner incarcerated under the emergency regulations issued by the Union government. The quote below encapsulates the varied experiences of certain OB members, and gives good insight into the nostalgia juxtaposed with bitterness, and it thus justifies being quoted at length. The original Afrikaans is added below to convey emotions and sentiments that might have been lost in the English translation, fully:

What I remember most clearly from the OB period is this ... camaraderie, the mutual relationship amongst the people, the unanimity, the enthusiasm, and simply the love of your volk and the love of your country ... Those are the beautiful aspects of the OB period for me. Another aspect about which I reminisce is the fact that I have lost many years of my life . I regret that I have lost many years of my life being locked up behind bars doing absolutely nothing . I was young, and that was probably the good years of my life. [Author's own translation]

[Jy weet wat my uit die OB-jare die meeste sal bybly, is dié ... kameraadskap, die onderlinge verhouding tussen die mense . die eensgesindheid, die entoesiasme en sommer net die liefde vir jou volk en die liefde vir jou land ... Dit is vir my die mooi dinge van die jare van die OB. 'n Ánder aspek waaraan ek terugdink, is die feit dat ek jare van my lewe verloor het . Ek is jammer oor die jare van my lewe wat ek verloor het; wat ek absoluut nutteloos agter tralies gesit en niks gedoen het nie. Dis seker, jy weet ek was jonk, die goeie jare van my lewe .]278

Despite this juxtaposition, the BOPG goal of creating a sense of togetherness and a sense of community aligned with the goal of the OB of creating cohesion amongst Afrikaners,279a legacy that the BOPG kept alive. The BOPG thus brought together a group of people who were bound by the shared experiences of being OB members and, in some cases, being directly affected by the internment policy.

Conclusion

The effect of the emergency regulations issued by the Union of South Africa - especially the internment policy - on the lives of OB members and the OB as an organisation did not end with the release of the last prisoners and internees. A long-lasting influence is also visible, especially concerning the Bond van Oudgeïnterneerdes en Politieke Gevangenes (BOPG). This article discusses the role played by the BOPG in the lives of OB members who were affected by the internment policy. As pointed out, the adjustment after internment and imprisonment was often difficult for some members. It is not the aim of this article to delve too deeply into the camaraderie formed in these camps and prisons; however, it is argued that the formation of the BOPG would not have been possible without this camaraderie. The camaraderie in the camps and the way it was formed were not properly analysed. This consequently provides a good opportunity for historians to delve deeper into the BOPG.280 The current study should therefore be viewed as a first attempt to explore the BOPG and to understand its role against the background of Second World War experiences, memories, and nostalgia in South Africa.

Much like the argument by Neil Roos that war service remained a crucial part of the identity of white SA men who volunteered to serve in the Second World War,281 this article maintains that the BOPG formed a similar platform for ex-internees and political prisoners to highlight a critical part of their identity in the post-war years. The conclusion is that the BOPG adopted the OB stance of helping and protecting and these two motives took various forms. As the current study is only an exploratory study into the BOPG, the article did not cover all of the similarities and differences between the BOPG and SA veterans' organisations, such as the MOTHs. Future research into the long-term effects of the Second World War on South Africans could explore this topic.

With the end of the Second World War, and a German defeat, the OB lost momentum.282However, the end of the war (1945), the release of the last political prisoners (1948), and the end of the OB (1952) did not mean that the effect of the emergency regulations also ceased. As a result of the emergency regulations, the BOPG continued to affect the lives of its members for forty years after the war (until 1985). The initial objective of the BOPG also focussed on the themes of help and protection, and later, most attention was shifted to preserving the history of the internment camps. Nostalgia played an important role in the social function that the BOPG fulfilled in the lives of its members, and this created a community where the heyday of the OB - especially the camaraderie, friendships, and support networks - could be fondly remembered and, to a certain extent, be continued.

This article argued that the biggest role played by the BOPG in the lives of those affected was that the organisation allowed its members to ensure the survival of important documents (directly related to what the BOPG considered to be 'our history') for future generations.283 This was done not only by the publication of Agter Tralies en Doringdraad but also by eagerly collecting documents related to the SA internees and political prisoners of the Second World War. This process eventually culminated in the establishment of the OB Archive. This provided those concerned with the means to "protect" the history of the events in which they were directly involved. Without the protection of these documents, this article, along with numerous other publications dealing with the OB, would not have been possible.

189 Anna la Grange obtained her Magister Artium in History (cum laude) from North-West University (Potchefstroom Campus) in 2020. She is currently pursuing a doctoral degree at the University of Potsdam. Her research interests include the role of South African troops in the two world wars, illegitimate violence, internment policies and practices, and the treatment of prisoners of war.

190 As the Bond van Oudgeïnterneerdes en Politieke Gevangenes (BOPG) is the official name of the association, this article uses the Afrikaans acronym BOPG throughout to refer to the association.

191 A Blake, Afrikanersondebok? Die Lewe van Hans van Rensburg, Ossewabrandwagleier (Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball, 2021); E Kleynhans, Hitler's Spies: Secret Agents and the Intelligence War in South Africa (Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball, 2021); A la Grange & C Blignaut, 'Die Ikonografie van Afrikanernasionalisme en die "Vryheidsideaal" van die Ossewa-Brandwag in die Suid-Afrikaanse Interneringskampe van die Tweede Wereldoorlog', Historia, 66, 1 (2021), 88-118; A Blake, Wit Terroriste: Afrikaner-saboteurs in die Ossewabrandwagjare (Cape Town: Tafelberg, 2018).

192 C Marx, Oxwagon Sentinel: Radical Afrikaner Nationalism and the History of the Ossewabrandwag (Pretoria: University of South Africa Press, 2008); and PF van der Schyff (ed.), Die Ossewa-Brandwag: Vuurtjie in Droë Gras (Potchefstroom: Potchefstroomse Universiteit vir Christelike Hoër Onderwys, 1991).

193 Blake refers to the BOPG in his biography of Hans van Rensburg, Afrikanersondebok, but mostly in relation to the organisation's role in the lives of Van Rensburg and later also his widow, Katie van Rensburg. See Blake, Afrikanersondebok, 286-287.

194 Both Blignaut and Olivier refers to the BOPG's publication, Agter Tralies and Doringdraad, but neither analyses the organisation itself. See C Blignaut, Volksmoeders in die Kollig: Histories-teoretiese Verkenning van die Rol van Vroue in die Ossewa-Brandwag, 1938 tot 1954 (MA thesis, North-West University, 2012), 6-7; DP Olivier, "A Special Kind of Colonist": An Analytical and Historical Study of the Ossewa-Brandwag as an Anti-colonial Resistance Movement (MA Thesis, North-West University, 2021), 26.

195 N Roos, Ordinary Springboks: White Servicemen and Social Justice in South Africa, 1939-1961 (London: Routledge, 2005), 197.

196 Blake, Wit Terroriste, 53-65; Marx, Oxwagon Sentinel, 515-529; AM Fokkens, The Role and Application of the Union Defence Force in the Suppression of Internal Unrest, 1912-1945 (MMil thesis, Stellenbosch University, 2006), 115-118; JM van Tonder, 'Die Afrikaanse Kerke in die Tweede Wereldoorlog (3): Internering', Die Kerkblad, 118, 3295 (2015), 14-15; P Furlong, 'Allies at War? Britain and the "Southern African Front" in the Second World War', South African Historical Journal, 54, 1 (2005), 16-29; HO Terblanche, John Vorster - OB-generaal en Afrikanervegter (Roodepoort: CUM Boeke, 1983), 133-170; C Blignaut, 'From Fund-raising to Freedom Day: The Nature of Women's General Activities in the Ossewa-Brandwag, 1939-1943', New Contree, 66 (July 2013), 121-150.

197 Prominent works include A la Grange, 'The Smuts Government's Justification of the Emergency Regulations and the Impact Thereof on the Ossewa-Brandwag, 1939 to 1945', ScientiaMilitaria, 48, 2 (2020), 39-64; FL Monama, 'South African Propaganda Agencies and the Battle for Public Opinion during the Second World War, 1939-1945', Scientia Militaria, 44, 1 (2016), 145-167; C Blignaut, '"Rebelle Sonder Gewere": Vroue se Gebruik van Kultuur as Versetmiddel teen die Agtergrond van die Ossewa-Brandwag se Dualistiese Karakter', Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Kultuurgeskiedenis, 30, 2 (2016), 109-131; FL Monama, Wartime Propaganda in the Union of South Africa, 1939-1945 (PhD dissertation, Stellenbosch University, 2014), 66-77; Blignaut, 'From Fund-raising to Freedom Day', 121-150; and C Blignaut, 'Doing Gender is Unavoidable: Women's Participation in the Core Activities of the Ossewa-Brandwag, 1938-1943', Historia, 58, 2 (2013), 1-18.

198 These transcripts form part of the Ossewabrandwag Archive in Potchefstroom, where both the transcripts and the audio recordings are stored. These interviews were conducted by staff from the university's archival department during the 1970s and 1980s, and in some cases audio tapes were recorded by BOPG members themselves and sent to the archives. This whole process is an impressive oral history undertaking that has not been addressed or fully investigated in any current literature on the OB. In 1960, the first edition of Dankie was published by the BOPG. The initial purpose was to serve as the official circular for the BOPG. Over time, it became known as the official organ of the BOPG. This publication offers a lens through which to view the activities of those who were directly affected by the internment policy and emergency regulations.

199 P Finney, 'Politics and Technologies of Authenticities: The Second World War at the Close of Living Memory', Rethinking History, 21, 2 (2017), 157. [ Links ]

200 Ossewabrandwag Archive (hereafter OBA), newspaper collection, Die OB, 7 April 1943.

201 OBA, DJM Cronjé Collection, Box 1, File 5/4, Die Ossewa-Brandwag: Vanwaar en Waarheen, 36.

202 C Blignaut & K du Pisani, '"Om die Fakkel Verder te Dra": Die Rol van die Jeugvleuel van die Ossewa-Brandwag, 1939-1952', Historia, 54, 2 (2009), 155. [ Links ]

203 OBA, newspaper collection, Die OB, 27 August 1952.

204 Marx, Oxwagon Sentinel, 553.

205 Die OB Circle of Friends (or OB-Vriendekring in Afrikaans) was formed in April 1952 in the western Cape area and the group mostly met and operated in this part of South Africa. The group was led by WR Laubscher and M van Rooyen, both former OB members, who also played a prominent role in the formation of the group. Apart from arranging social events from time to time and organising fund-raising endeavours to assist with the payment and upkeep of the Amajuba farm, the group did not really affect the lives of former OB members. For this reason, the focus of this article is on the BOPG rather than the OB Circle of Friends; however, the Circle of Friends should at least be mentioned and considered as one other group that outlasted the OB. For more information on the OB Circle of Friends, see OBA, J Corin Collection, Box 1, File 1/3, "OB-vriendekring Geskiedenis"; and OBA, WR Laubscher Collection, Box 1, File 1/2, "OB-Vriendekring".

206 Although the BOPG already existed before the official disbandment of the OB, it far outlasted the OB. It also provided an opportunity for many individuals with ties to the OB to meet up and rekindle old friendships that were formed during the OB years. OBA, unpublished pamphlet by HM Robinson, 'n Perspektief op die Uitstalling, 10.

207 OBA, BOPG Collection, Box 8, BOPG Minute Book, Minutes of the first BOPG general meeting held in Pretoria, 22 April 1946.

208 OBA, Dankie, 1, 2 (1961), 11.

OBA, Dankie, 1, 2 (1961), 11.

210 OBA, BOPG collection, Box 8, BOPG Minute Book, Minutes of the first BOPG general meeting held in Pretoria, 22 April 1946. Van Rensburg remained the honorary president until his death in 1966, after which the BJ Vorster became the honorary president of the organisation. OBA, Dankie, 7, 1-2 (1967).

211 OBA, Dankie, 1, 1 (1960), 21.

212 This suggestion was made by the executive council of the BOPG, and printed in the official mouthpiece of the organisation, see OBA, Dankie, 1, 4 (1961), 7-8, 18.

213 OBA, Dankie, 1, 4 (1961), 7-8, 18.

214 OBA, Dankie, 4, 1 (1964), 2. Translated from Afrikaans.

215 OBA, Dankie, 17, 2 (1977), 3. Translated from Afrikaans.

216 OBA, Dankie, 4, 1 (1964), 2. Translated from Afrikaans.

217 OBA, Grootraad Collection, Box 1, File 2/9, Ossewabrandwag Constitution, Article IV (5), c. 1940.

218 OBA, BOPG Collection, Box 1, File 2, "Korrespondensie: Stigting van BOPG". Correspondence between BOPG members, 1 August 1947, 24 August 1947.

219 OBA, BOPG Collection, Box 1, File 2, "Korrespondensie: Stigting van BOPG". Correspondence between BOPG members, 1 August 1947. Translated from Afrikaans.

220 OBA, BOPG Collection, Box 8, BOPG Minute Book, Minutes of the BOPG conference of 4 October 1947, held in Pretoria. Translated from Afrikaans.

221 OBA, BOPG Collection, Box 8, BOPG Minute Book, 5. Minutes of the BOPG conference of 4 October 1947, held in Pretoria.

222 OBA, photo collection, record number F00513 1.

223 OBA, BOPG Collection, Box 1, File 2, "Korrespondensie: Stigting van BOPG". Correspondence between BOPG members, 9 August 1947. Translated from Afrikaans.

224 OBA, book collection, record number A8393.

225 All four objectives are stated in the BOPG's official constitution. OBA, BOPG Collection, Box 8, BOPG Minute Book, Constitution of the BOPG. The quote is translated from Afrikaans, original Afrikaans: "Om die geskiedenis van die internering en kampe op boek te stel".

226 OBA, Dankie, 1, 1 (1960), 10.

227 Department of Defence Archives (hereafter DOD Archives), Army Intelligence Group, Box 49, File I:43(H), Subversive Activities (Sabotage and Treason), report, 1 October 1942 .

228 OBA, Dankie, 2, 2 (1962), 25. Translated from Afrikaans.

229 OBA, BOPG Collection, Box 1, File 2, "Korrespondensie: Stigting van BOPG". Correspondence between BOPG members, 3 May 1948. Translated from Afrikaans.

230 OBA, BOPG Collection, Box 8, BOPG Minute Book, 3. Minutes of the first BOPG general meeting held in Pretoria, 22 April 1946.

231 This quote appears prominently and regularly in interviews with BOPG members and in the BOPG's official newsletter, Dankie. For some examples, see OBA, Dankie, 5, 3 (1965), 4; Dankie, 25, 1 (1985), 13 and Dankie, 25, 1 (1985), 24; OBA, interview transcriptions, tape number 109, 1985, "Mededelings deur Mnr. Leonard Johannes Marais van Bloemfontein", 16.

232 Including Agter Tralies en Doringdraad, which is discussed regularly between 1965 and 1985 in various editions of Dankie.

233 OBA, Dankie, 5, 3 (1965), 13; Dankie, 6, 1 (1966), 42-43; Dankie, 7, 1 (1967), 4, 24; Dankie, 7, 2 (1967), 11-12; Dankie, 8, 1 (1968), 4-5, 11-12, 27-28, 47; Dankie, 8, 2 (1968), 8, 14, 17, 43; Dankie, 9, 1 (1969), 11-12, 39, 45; Dankie, 9, 2 (1969), 4, 11; Dankie, 10, 1 (1970), 20, 32; Dankie, 10, 2 (1970), 8, 15; Dankie, 11, 1 (1971), 15; Dankie, 12, 1 (1972), 15, 20; Dankie, 13, 1 (1973), 7; Dankie, 15, 1 (1975), 10, 17, 22; Dankie, 15, 2 (1975), 32, 36, 39-41; Dankie, 16, 1 (1976), 14, 28-29; Dankie, 16, 2 (1976), 13-14, 28-29, 38; Dankie, 18, 1 (1978), 11; Dankie, 19, 1 (1979), 3, 20; Dankie, 20, 1 (1980), 3, 37, 39, 44, 46; Dankie, 22, 1 (1982), 29; Dankie, 23, 1 (1983), 35; Dankie, 25, 1 (198 5), 47-49.

234 OBA, Assistent Kommandant Generaal (hereafter AKG) Collection 3/18/34, Folio 4, "Boerejeug". Newsletter 4/44, 14 June 1944.

235 OBA, Dankie, 23, 1 (1983), 27-28.

236 OBA, Dankie, 23, 1 (1983), 27-28; OBA, Dankie, 16, 2 (1976), 13-14.

237 OBA, interview transcriptions, tape number 215, 1977, LM Fourie and H Anderson interview, 4-5.

238 OBA, Dankie, 23, 1 (1983), 7.

239 In this context, "our" refers to BOPG members. OBA, Dankie, 23, 1 (1983), 35. Translated from Afrikaans.

240 OBA, BOPG Collection, Box 1, File 2, "Korrespondensie: Stigting van BOPG". Correspondence between BOPG members, 6 December 1947. Translated from Afrikaans.

241 OBA, BOPG Collection, Box 8, BOPG Minute Book, Minutes of the BOPG meeting of 15 November 1947, Pretoria. Translated from Afrikaans.

242 OBA, BOPG Collection, Box 8, BOPG Minute Book, Minutes of the BOPG meeting of 15 November 1947, Pretoria. Translated from Afrikaans.

243 OBA, BOPG Collection, Box 1, File 2, "Korrespondensie: Stigting van BOPG". Correspondence between BOPG members, 6 December 1947. Translated from Afrikaans.

244 OBA, BOPG Collection, Box 1, File 2, "Korrespondensie: Stigting van BOPG". Correspondence between BOPG members, 5 January 1948. Translated from Afrikaans.

245 OBA, BOPG Collection, Box 1, File 2, "Korrespondensie: Stigting van BOPG". Correspondence between BOPG members, 5 January 1948. Translated from Afrikaans.

246 OBA, BOPG Collection, Box 1, File 2, "Korrespondensie: Stigting van BOPG". Correspondence between BOPG members, 15 January 1948. Translated from Afrikaans.

247 OBA, BOPG Collection, Box 1, File 2, "Korrespondensie: Stigting van BOPG". Correspondence between BOPG members, 3 May 1948.

248 OBA, BOPG Collection, Box 1, File 2, "Korrespondensie: Stigting van BOPG". Correspondence between BOPG members, 30 December 1947.

249 For more information on the names and locations of Second World War internment camps in South Africa, see Fokkens, The Role and Application of the Union Defence Force, 115-118.

250 OBA, BOPG Collection, Box 1, File 2, "Korrespondensie: Stigting van BOPG". Correspondence between BOPG members, 6 December 1947.

251 OBA, BOPG Collection, Box 1, File 2, "Korrespondensie: Stigting van BOPG". Correspondence between BOPG members, 3 June 1948.

252 OBA, BOPG Collection, Box 1, File 2, "Korrespondensie: Stigting van BOPG". Correspondence between BOPG members, 3 June 1948. Translated from Afrikaans.

253 I Raubenheimer, 'Aanbevelingswoord', in HG Stoker (ed.), Agter Tralies en Doringdraad (Stellenbosch: Pro Ecclesia, 1953), vi. Translated from Afrikaans.

254 Raubenheimer, 'Aanbevelingswoord', vi. Translated from Afrikaans.

255 OBA, BOPG Collection, Box 29, File 144, Official song of the BOPG ("Bond se lied"). The original Afrikaans lyrics are included to retain the lyric and poetic nature of the song.

256 OBA, interview transcriptions, tape number 1, undated, HL Pretorius interview, 12.

257 Olivier, "A Special Kind of Colonist", 26.

258 OBA, Dankie, 5, 3 (1965), 16-18.

259 OBA, Dankie, 6, 2 (1966), 24.

260 See for example OBA, Dankie, 9, 2 (1969), 18-19. The war museum in Bloemfontein also initially collected items related to the internment camps; however, this initiative was later completely taken over by the PU for CHE.

261 OBA, Dankie, 16, 1 (1976), 15; OBA, interview transcriptions, tape number 119, 1976, J Ackermann interview, 1. This decision was possibly motivated by the fact that the PU for CHE already had numerous artefacts and documents in their possession at this point. One of the last decisions made by the OB before its official dissolution was to donate all the organisation's documents and records to the PU for CHE's Ferdinand Postma Library. For more information on the transfer of the records to the PU for CHE, see OBA, BOPG Collection, Box 18, File 83/3, "Ontbindingsfunksie", 12 October 1985; OBA, unpublished pamphlet by HM Robinson, 'n Perspektief op die Uitstalling, 1-12; E Kleynhans, 'Documenting Afrikaner Fascism: A Historical Overview of the Ossewabrandwag Archive'. Paper presented at the Historical Association of South Africa (HASA), HASA / HGSA Biennial Conference, Thaba Nchu, 20-22 June 2018.

262 OBA, Dankie, 16, 1 (1976), 3.

263 OBA, BOPG Collection, Box 8, BOPG Minute Book, 453. Minutes of the BOPG conference of 4 October 1947. Translated from Afrikaans.

264 After the death of JM Ackermann in 1981, for example, the organisation's membership radically declined and finding a safe place for its documents became even more important. OBA, Dankie, 21, 1 (1981), 14.

265 OBA, BOPG Collection, Box 8, BOPG Minute Book, 430. Report by the chairman of the BOPG, 6 October 1984. These reasons were also published in Dankie, see OBA, Dankie, 24, 1 (1984), 7.

266 All four goals are stated in the official constitution of the BOPG, see OBA, BOPG Collection, Box 8, BOPG Minute Book, 1.

267 J Tosh, The Pursuit of History: Aims, Methods and New Directions in the Study of History (London: Routledge, 2015), 15-17. [ Links ]

268 N Roos, 'The Springbok and the Skunk: War Veterans and the Politics of Whiteness in South Africa during the 1940s and 1950s', Journal of Southern African Studies, 35, 3 (2009), 657-658. [ Links ]

269 The Afrikaans term "volksfeeste" is a better description. At these events, traditional Afrikaner

dancing took place and traditional food was served, with the aim of continuing the "ossewa-gees" born out of the 1938 centenary celebrations.

270 DOD Archives, Adjutant-General (3)154, Box 469, File 361/4, Civilians Subversive Activities - Ossewa-Brandwag, Method and Organization of the Ossewa-Brandwag, 17 July 1941.

271 DOD Archives, Army Intelligence Group, Box 50, File I:44(B), SA Troops Morale, November 1941.

272 OBA, Dankie, 17, 2 (1977), 3.

273 OBA, Dankie, 2, 2 (1962), 14. "Die Eiland" refers to Van Rensburg's farm in the Parys area. The farm was bought by OB supporters and gifted to Van Rensburg. For more information, see H van Rensburg, Their Paths Crossed Mine (Cape Town: Central News Agency, 1956), 166-268.

274 See for example OBA, Dankie, 2, 2 (1962), 14.

275 OBA, photo collection, record number F01334/1.

276 Tosh, The Pursuit of History, 16.

277 OBA, Dankie, 2, 2 (1962), 25; and OBA, BOPG Collection, Box 1, File 2, "Korrespondensie: Stigting van BOPG". Correspondence between BOPG members, 3 May 1948.

278 OBA, interview transcriptions, tape number 1, undated, HM Robinson and HL Pretorius interview, 12.

279 OBA, Grootraad Collection, Box 1, File 2/9, Ossewabrandwag Constitution, Article IV (5), c. 1940.

280 A similar study has been done on the Zonderwater Italian prisoner-of-war camp by Donato Somma, who analysed the role of music in the lives of the prisoners of war in the camp during their detainment; see D Somma, 'Music as Discipline, Solidarity and Nostalgia in the Zonderwater Prisoner of War Camp of South Africa', SAMUS: South African Music Studies, 30, 1 (2010), 71-85.

281 Roos, Ordinary Springboks; Roos, 'The Springbok and the Skunk'.

282 For a more detailed discussion of all the factors that contributed to the demise of the OB, see Marx, Oxwagon Sentinel, 530-554.

283 As explained, this quote appears prominently and regularly in interviews with BOPG members and in the BOPG's official newsletter. For some examples, see OBA, Dankie, 5, 3 (1965), 4; Dankie, 25, 1 (1985), 13 and Dankie, 25, 1 (1985), 24; OBA, interview transcriptions, tape number 109, 1985, "Mededelings deur Mnr. Leonard Johannes Marais van Bloemfontein", 16.