Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Educational Research for Social Change

On-line version ISSN 2221-4070

Educ. res. soc. change vol.12 n.2 Port Elizabeth Oct. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2221-4070/2023/v12i2a7

ARTICLE

Grade 4 Rural Learners' Views and Learning Experiences That Address Social Justice in Postapartheid South Africa

Hlamulo MbhizaI; Thabisile NkambuleII

IUniversity of South Africa. mbhizhw@unisa.ac.za; ORCID ID: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9530-4493

IIUniversity of the Witwatersrand. Thabisile.Nkambule@wits.ac.za; ORCID ID: http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0044-3170

ABSTRACT

The complexity and dynamic nature of rural contexts and schools present intricacies for teaching and learning practices, understanding the challenges learners experience, as well as the overall educational achievements within the South African context. We argue that learning is fundamentally a social phenomenon that occurs within communities, making it important to explore the strengths, diversity, as well as learning challenges presented by the rural context to learners given that they learn in rural schools and classrooms daily. The symbolic interactionism framework was used to understand emergent meanings in the process of interacting with primary school learners, and how learners made sense of their experiences of learning in rural schools. A qualitative phenomenological research methodology was espoused to unearth learners' experiences of the rural contextual conditions in relation to learning. Photo-elicitation group interviews were used to collect data from eight learners from three different schools, and the data were analysed using a thematic approach. The findings revealed that children are aware of the conditions that shape their learning in rural schools. The information provided by the learners shows that much is yet to be done by the postapartheid government to address issues of equity and social justice through education in South Africa.

Keywords: rural, learning, learning conditions, experiences, rural schools, photo-voice

Introduction and Background

The United Nations (1989) Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), especially Article 12 of the CRC, gave children the right to express their views and be heard on all matters affecting them (Robinson, 2014). Due to the dearth of research in rural education, one of the main goals of this study was to understand the views and learning experiences of Grade 4 rural learners. The CRC clearly stated the expectation for schools to ensure the views of children are "heard and valued in the taking of decisions which affect them, and that they are supported in making a positive contribution to their school and local community" (United Nations, 2008, p. 5). We also promote the involvement of children in the process of knowledge construction in order to get their honest views on how best to improve learning in rural primary schools. Learners who reside in rural schools continue to experience complex teaching and learning inequities related to textbooks, chalk/white boards, chairs and tables, pens and pencils-things that could be taken for granted yet play a major role in learner performance. The Republic of South Africa's (RSA, 1996a) Constitution and the South African Schools Act (RSA, 1996b) stated that every South African learner should have access to learning and teaching, similar facilities, and equal educational opportunities (Singh, 2022)-which remain wishful thinking for many rural learners. Therefore, a particular focus is given here to how contextual elements play a role in defining the learning experience.

Usher (2018) stated that if we accept that constructing meaning from experience may be a more useful way of thinking about learning, then we are forced to recognise the active part the learner must play in that constructive process. The learning experience is a process in which situations can influence the way we are constituted in a certain time (moment of life) and space. Given that learning can happen in different social contexts, time, and space, in this study, we clarify that we are interested in the learning experiences in the primary schooling as context, and in the rural school as learning space. Even though some progress has been made since the end of apartheid in 1994, addressing social justice in the education system has been a challenge-particularly for the rural communities, schools, and learners. In postapartheid South Africa, rural schools continue to experience inequity in resource allocation, unequal access to funding opportunities due to remoteness, inefficient continuous professional development, and reluctant visits by district officials due to distances to schools (Mbanda & Ncube, 2021). These issues affect learning for rural learners because they compromise infrastructure and learner transportation (which can affect learners' consistency in school attendance) and teacher's professional development and practices.

Teachers usually tend to reflect on young children's successes and failures from their own perspectives, forgetting that children might attribute their successes or failures to entirely different factors (Bandura, 1977). According to Grau and Whitebread (2012), little is known about how children evaluate their own learning-even though this skill is critical for effective learning. Marcus et al. (2018) stated that children are renowned for having fantastic imaginations and have an enormous potential to think outside the box and produce truly innovative designs but are usually hindered by a strong sense of what the adult wants to hear. In this study, we allowed children to take pictures in order to see and understand rural schools and classrooms from their viewpoints, and to gain insight into learning experiences from their positions. The learning context plays a significant role in how children engage with learning tasks and situations. Colliver and Fleer (2016) posited that children's perceptions of the learning context influence their beliefs about themselves, their confidence, and their schoolwork. In turn, these beliefs and this confidence can influence the nature and extent of their engagement with learning tasks and situations. We focused specifically on Grade 4 learners because of the current research gap on this cohort in a rural context, and because we believed that they could talk about their own views and learning experience. We acknowledge the complex challenges of researching children's views and experiences due to age and cognitive development differences, diverse socio-economic and cultural backgrounds and experiences, as well as communication barriers. We seriously considered these complexities during the conceptualisation and data generation process and, for that reason, we used photos to make it easy for learners to talk about what they have captured.

Research has predominantly focused on teachers' experiences and teaching, resulting in a preponderance of teaching knowledge and positioning of teachers as experts of that knowledge, possessing the right to speak about teaching and learning processes. There is a paucity of research that interacts and presents primary school learners' views as experts on their own knowledge and experiences of learning, recognising them as individuals capable of speaking about and acting upon their experiences and knowledge (Pinter et al., 2013). Our position was to interact with rural primary school learners as active participants in the research on learning in rural classrooms. It was important for us to ensure that we did not trivialise the learners' involvement or let them become mere novelties, but to value their views and experiences and respect their involvement in ways that recognised children's thinking (Danaher, 2020). This is one way of redressing the overlooked critical discussion with primary school learners who experience the day-to-day conditions of learning in rural schools, as well as addressing issues of social justice as prioritised in the National Development Plan (RSA, 2012). Considering that discussion, this paper sought to answer the following research questions:

• What are the Grade 4 learners' views of learning in rural schools?

• What are the learners' experiences of learning in rural classrooms?

• What are the factors that influence learners' views and learning experiences?

The Research on Children's Perspectives

Research focusing on children's perspectives aims to unearth children's experiences, ways of thinking, ways of knowing, as well as ways of acting within a specific context (Ford et al., 2017). The research on children's perspectives resonates with the notion of child-centredness, which emphasises the need to view and treat children as active subjects (Graham et al., 2015; Powell et al., 2013). Previous studies that adopted child perspectives have highlighted the capability of children to act actively as producers and co-producers of research knowledge (Carter & Ford, 2013; Honkanen et al., 2018), a position we have taken seriously in this study. According to Honkanen et al. (2018, p. 184), "the well-being of children and young people has typically been studied from the adult's point of view, and traditional adult-centred research orientation has led to an adult's interpretation of child and childhood." We problematise the positioning of children and young people in research as individuals who are incapable of reflecting on their own experiences, and support researching with children in order to gain insight into their views and experiences, which continue to be marginalised by education researchers in South Africa. This resonates with studies that advocate the need to place children centrally for researchers who seek to understand their experiences and perspectives on schooling, learning, and well-being (Fattore et al., 2012).

In light of the above discussion, Farrugia (2014) posited that place and space are integral parts of children's lives given that they live and interact within specific cultural, geographical, historical, and situational contexts. Thus, awareness of their views about rural schools and classrooms as specific places and spaces that could influence their day-to-day learning experiences is important in order to gain insights into their everyday schooling lives, and to advance the understanding of education that children receive (Christensen et al., 2015; Nansen et al., 2015). We need information about primary school learners' experiences of learning in rural schools and classrooms, and how they see their schooling environment, so contributions can be made at policy level for the improvement of rural schools. In this regard, recent studies have emphasised the importance of listening to children's views on matters that are relevant and affect them as individuals as well as their communities (Christensen et al., 2015). Although researchers have shown a developing interest in children's experiences internationally, there is dearth of research within the South African context that has highlighted children's voices, especially in rural contexts and rural schools (Mbhiza, 2021; Nkambule, 2017). In this paper, we positioned primary school learners as experts of their own lives, researching with them to explore and problematise the nature of rural learning conditions and rural education.

Situating Research on Children's Learning Experiences

There are few studies that have explored children's views and learning experiences in rural South African schools. We decided to focus on children's views in order to understand their lived learning experiences as participants and learners in rural classrooms. As mentioned earlier, it is important to consider children's learning experiences because much of the research has been done from teachers' perspectives (Poulou, 2017), and has overlooked the important role that children play in their learning experiences. Children should have the right to be heard and are their own experts in describing their experiences and the impact of those experiences on their performance (Fattore et al., 2019; Simmons et al., 2015). Given that existing research has not focused on rurality, we believe it is important to understand how a rural learning context is experienced by children, and the role it plays in shaping their learning experiences. Such research has not been prevalent in South Africa because of the dominant focus on teachers' perceptions and experiences of teaching in rural contexts. Learning from the experiences of children is essential for teachers to understand their teaching from the everyday experiences of the children, and to enhance teachers' practices in context of children's views.

According to Pálmadóttir and Einarsdóttir (2016), a substantial body of research has argued that young children are incapable of understanding what learning is, and of reflecting on their own learning process. In addition, the practice of defining learning and reflecting on its processes has historically excluded children from the conversation. Murris and Muller (2018) stated that modern schooling positions children as knowledge consumers, not producers, because it is assumed that they are (still) developing, (still) innocent, (still) fragile, (still) immature, (still) irrational. Earlier, Hopkins' (2008) study with 180 junior school learners in Years 3-6 (ages 7-11 years) sought to elicit learners' views of learning and found that learners from all four year groups viewed the chance to be active learners and involved in hands-on activities as important contributory factors to the enjoyment of learning in school. In addition, learners became demotivated when they considered teachers over-talked, and expressed their perception that most teachers "talk too much," and such over-talking is the reason that learners have insufficient time for completing work in lessons: "She tells us again and again, then we run out of time" (Hopkins, 2008, p. 397). John-Akinola et al.'s (2014) study of 248 primary school learners aged 9-13 years reported that positive interpersonal relationships and feeling a sense of belonging were two aspects of their school experiences that were significant in contributing to learners feeling they were members of the school community.

In a study involving forty 3 to 6-year-old children from a Brazilian early childhood education and care school and Finnish day-care centres, Ferreira et al. (2018) used photographs to investigate children's perceptions of their learning experiences in the contexts of early childhood education. Their findings showed that the children's perceptions of learning were intimately connected to how they explored objects and places, indicating that children created opportunities to freely construct knowledge based on their appropriation and multiple uses of objects. This shows that children not only reproduce meanings, but produce them; they do not just adapt to the modification and (co)construction of social values and norms-they also influence them. This was an important study to consider for our study, because we also gave learners small cameras to take photographs of their schools and classrooms to understand the role the infrastructure plays in their learning experiences in such contexts. A relatively large study in Ireland, involving 1,149 primary school children aged 6-12 years, explored learners' attitudes towards, and experiences of, science in school (Murphy et al., 2021). Findings from that study resonated with those from other studies (Grau & Whitebread, 2012; Leinonen & Venninen, 2012; Tirosh et al., 2012) exploring learners' general views on learning in primary schools. They indicated that learners enjoyed and engaged with hands-on science and would like science lessons to involve more experiments and less writing. Learners also expressed a preference for working collaboratively with a friend in science, rather than on their own, and appreciated the benefits to learning when working collaboratively.

Theoretical Framework

The espoused theoretical framework for this article is symbolic interactionism, which enables the examination of how learners interact within their contexts. Blumer (1969), who coined the term "symbolic interactionism," was Mead's student and asserted that humans interact with things based on meanings they ascribe to those things. For symbolic interationism, the meanings we ascribe to things come from our interactions with others and society. Blumer (1969) posited that "the meanings of things are interpreted by a person when dealing with things in specific circumstances" (p. 47). Mead's contribution was in the development of self, especially in childhood, where he detailed how the child learns to take the role of the other, which is important in our study, because Grade 4 learners are still considered to be children (Mead, 1943, in Fink, 2016). We used photos as symbols to understand how learners communicate their views and learning experiences, thus developing meanings. The primary premise of this framework was the need to understand the meaning making that occurs through complex interactions within specific contexts (Blumer, 1986; Lifumbo, 2016), and the subjective meanings Grade 4 learners give to their experiences of learning in rural schools. Symbolic interactionism comprises three key principles: meaning, language, and thought (Lifumbo, 2016). Meaning is significant to human thinking and behaviour because humans act towards other people and objects based on the meanings they attribute to those individuals and objects (Lifumbo, 2016). Accordingly, the experienced conditions of learning in rural schools are symbolic because they do not possess meanings on their own. Learners ascribe meanings to rural education in their own ways as they experience what it means to learn in those contexts and schools. In this article, we do not view the specific conditions to be universal; rather, the meanings that learners attach to their lived rural experiences are dynamic, generative, and space and time specific.

The second principle of symbolic interactionism is the significance of language in the process of meaning making because it is through language that humans negotiate meaning through social symbols (Denzin, 2017). According to Vygotsky (1978), children accumulate language as they grow up in a society and mediate the kind of understanding they can form or construct. This means that language, in its different forms, constitutes the major symbolic tool appropriated by children and it shapes their views and understanding of learning experiences. According to Mead (1934), there is a relationship between thought and language because thought develops into action through language. This means that thought transforms the interpretation of the objects in the environment, using language in discussions and conversations. In this paper, the principle of language is important because it allows information about the rural learners' thoughts as they describe their views and experiences of learning within rural schools. Smit and Fritz (2008) stated that thoughts modify the symbols an individual encounters within their environment, and language reveals their thoughts and provides meaning and positionality, which is negotiated through symbols upon which the learners acted in the current study. In view of this, gaining insight into primary school learners' learning experiences, thoughts, and meanings of social condition using language are important in rural schools.

From a symbolic interactionist perspective, the subjective experience of the social actor (an individual) is a tool for analysis in understanding a particular organ of society-the school as a social organ for this paper (Stryker, 2017). Rural learners interact socially and adjust their behaviour in response to other people's actions and, as people interpret the actions of others, they adjust their own actions and behaviour. Thus, it becomes important to make sense of rural primary school learners' actions and interactions within an environment, using language that presents specific conditions of learning within rural contexts and schools. Thus, in this paper, we consider that learners are socialised as active beings and actively construct meaning in their social world, hence creating their own social reality relating to the learning conditions they experience (Carter & Fuller, 2016).

Furthermore, Blumer (2018) posited that the basic premise of symbolic interactionism is the understanding that events cannot be seen as purely objective but are impacted by the meanings social actors ascribe to external stimuli. Considering this, we believe that researching with learners to understand their lived experiences is essential to help us identify and understand specific conditions in rural schools that enable or constrain the effectiveness of their learning. For this paper, it was therefore important to allow learners to identify objects in their particular school that they were happy with as well as those they regarded as constraints to effective learning. We also paid attention to the specific meanings and interpretations learners ascribed to specific objects during our interactions and discussions.

Research Methodology

This study used the qualitative phenomenological design to explore Grade 4 learners' views and learning experiences in their natural setting, while making sense of the phenomena within complex, locally constructed realities (Qutoshi, 2018). Phenomenology explicates the meaning people attribute to everyday experiences-which were the ways in which the learners live in relation to a phenomenon (Vagle, 2014). Thus, knowledge is not viewed as universal truth but as a subjective understanding of reality we gathered through observation and interpretation. In our study, we used a qualitative phenomenological research methodology to explore Grade 4 rural learners' experiences and views of learning in rural schools and classrooms. The focus in phenomenological study is placed on the individual's lived experiences, rather than on the world as something detached from the person (Seamon, 2018). In our study, this meant understanding the nature of rural schools, specifically learning in rural classrooms as experienced by the learners.

We describe things as mentioned and represented by the learners-the way that rural learners experienced the conditions of learning in their schools-and looked for meanings embedded in their experiences. An understanding of the rural learners' world was the focus of the study because we believe that children make choices that are bounded by the specific conditions of their daily lives (van Manen, 2017). We believe that the social reality of learning in a rural context, as well as the meaning of the phenomena, are entrenched within the conscious experience of the learners. Accordingly, we allowed the learners to take photographs about aspects they loved about their schools as well as those they felt constrained the effectiveness of their learning, and we subsequently talked about issues related to these during our interviews (Carter & Ford, 2013).

Photo-Elicitation Interviews

In our study, we used child-centred photo-elicitation interviews to facilitate the generation of quality data with rural primary school learners. This method was helpful because it liberated the children's ability to express their views on conditions of learning in rural schools (Carter & Ford, 2013). We believed that the traditional methods of data generation, such as individual and focus group interviews, would constrain the depth and quality of data generation due to factors such as the children's reliance on verbal skills to answer questions, and their need to respond promptly to questions with no referent to aid their thinking (Miller, 2016). Photo-elicitation interviews as a data generation tool is based on the use of photographs that are supplied by researchers or the participants during conversations about the subject under scrutiny. In the current study, we gave learners cameras for approximately an hour to take photographs of the things they believed helped their learning, as well as things they felt limited their learning in their schools. After these activities, we engaged in photo-elicitation interviews about their different photographs. We used the photographs as visual inventories of different objects, artefacts, and depictions of events that the learners regarded as either positive or negative in their learning. The photographs helped us to generate an in-depth understanding of the conditions of learning in rural schools, and further allowed us and the learners to explore meanings about the conditions that were generated through learners' photographs (Mandleco, 2013).

Furthermore, the use of photographs with the children facilitated communication, resulting in detailed discussions with the learners about the conditions of learning in rural schools, and bridged the gap between the researchers' and participants' worlds because understanding was anchored in the photographs (Wells et al., 2013). This method helped us to explore the rural learners' lived experiences, critically examining things that are of importance to the learners, and allowed us to explore areas that we might otherwise have overlooked if we had only used the traditional adult research approach (Meo, 2010; Miller, 2016). Allowing the learners to provide and dictate the contents of the images that the conversations revolved around helped "to reduce the researcher bias embedded in the selection of specific images, subjects, and themes used in the interviews" (Lapenta, 2011, p. 206). The use of learner-driven photo-elicitation, and in accordance with symbolic interactionism, power dynamics between researchers and participants were altered because we allowed the learners to define what was important rather than what we thought was important. Thus, we conducted the study with primary school learners, rather than on them and about them because we considered the learners as legitimate and capable knowledge-producing agents (Grant, 2017). This process created a strong connection between the practices of photography and photo-elicitation to present in-depth insights into learners' experiences and views about learning in rural schools and classrooms. Even though it is an effective research method for the study, it was time consuming for the learners because they had to move around to identify appropriate symbols, make sense of them, talk about through reflection, and link them to their views and experiences of learning. The interpretation of the photos was done by the learners given that they gave meanings to the pictures, and our analysis and meanings were taken from the way learners talked about the pictures.

Data Analysis

We used a digital recorder to capture all the conversations with the learners, after having obtained consent from the parents and themselves. The initial stage of data analysis involved reducing the data, guided by the research questions. During this analysis stage we generated codes and developed them into key themes that we grouped together to form the final themes for discussion. We used a prior and emergent codes because they allowed us to work with the wealth of data in its entirety. In essence, we engaged in the following stages of data analysis: data reduction, consideration of plausibility of data and coding, conversion and clustering, verification with each group of learners and, finally, factoring. This process enabled in-depth understanding of learners' experiences and views about the conditions they encounter within rural schools and, in turn, how such conditions facilitate or constrain learners' effective learning.

During the analysis of the interviews, we focused on the learners' explanations of the content of their photographs and reasons for taking photographs of specific objects. This approach enabled us to understand some of the reasons for the learners to take photographs and the meanings ascribed to the photographs. Without the learners' explanations for the taken photographs, the ascribed meanings would have been misinterpreted (Mandleco, 2013; Miller, 2016). We transcribed the interviews separately from the photographs so the interview transcripts did not have context until we viewed the photographs that corresponded with learners' reflections. Accordingly, when the photographs and interview transcripts were viewed simultaneously, we created codes of learners' explanations and reasons for taking specific photographs as instrumental and symbolic in understanding their views and experiences of learning in rural schools and classrooms.

Ethical Considerations

We considered all the ethical processes in the study. All parents, the Wits School of Education, the Mpumalanga Department of Education, and the learners gave permission. For the learners, teachers assisted by explaining the nature of the study and the volunteering process to participate in the study. What was important throughout the data generation processes was reflexivity on how we developed the process in a way that facilitated opportunities for primary school learners to engage in the study. To ensure anonymity of the information that was provided by the learners during the photo-elicitation interviews, we used pseudonyms to conceal the identities of the children and their schools.

Findings and Discussion

The quality of rural education in South Africa has been in the spotlight in recent years (du Plessis & Mestry, 2019). The concern has been on how the quality of education rural learners receive can be improved. The Nelson Mandela Foundation (2005, p. viii-ix) had earlier argued that "the great majority of children in rural poor communities are receiving less than is their right in a democratic South Africa." Although the often-cited challenges for rural schools in South Africa include large class sizes, limited learning and teaching resources, and under-qualified or untrained teachers, learners in the current study identified other challenges that impinged on the effectiveness of their learning. The following sub-sections present and discuss the challenges identified by the learners through photographs and conversation-elicited interviews. These deal with the conditions of the school buildings and learning in multi-grade overcrowded classrooms.

The Conditions of the School Buildings

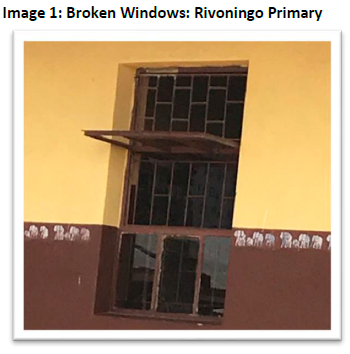

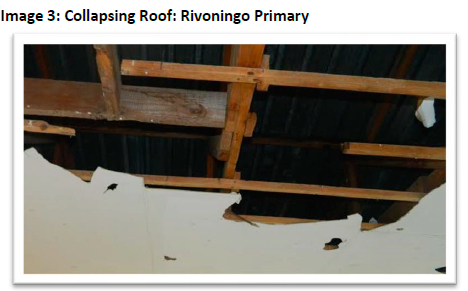

Photographs of decaying school buildings, broken windows, and classrooms without doors demonstrated features of the learners' views about learning in rural schools that they believed constrain the quality of education they receive (see Images 1 to 5). The learners complained that they suffer from the cold in winter and, in summer, it rains inside the classrooms. One learner from Rivoningo described her school and classroom thus:

We decided to take this picture because look at our school, there are lot of broken windows, it gets cold inside the classroom and some of us don't even have jerseys to be warm. (Image 1)

This statement demonstrates the infrastructural impediment at Rivoningo as well as levels of poverty that result in learners not having jerseys for cold days. Considering that we pay attention to the learners' meanings and interpretations ascribed to specific objects within their schools, it is important to note that the above statement reveals the interrelationship between the conditions of the infrastructure and the levels of poverty in the community. If the above statement is critically analysed, it reveals that learners do not ascribe meaning to the experiences of cold weather only to the broken windows, but also to the fact that they do not have jerseys to keep themselves warm.

When the above statement is critically considered alongside Images 1 to 5, one could argue that rural schooling contexts experience infrastructural impediments that are unique to schools located those areas in South Africa (du Plessis, 2014). According to Kak and Gond (2015, p. 13), poor infrastructure in rural schools contributes to poor learner attendance, which has a significant impact on their academic performance. In view of the learner's comment about classrooms with broken windows, broken doors, and lack of jerseys, learners might stay away from school on cold days due to these infrastructural constraints.

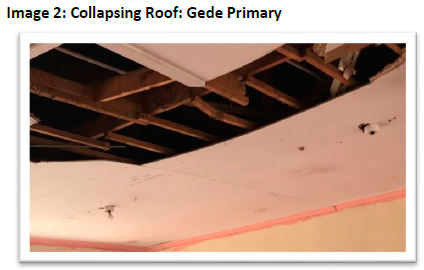

At another school, Gede Primary, learners commented that most of their classrooms are dilapidated, and they fear that one day when it rains very hard, the school buildings might collapse. Learners commented on Image 2, saying:

Look at this classroom, the, one day when it rains a lot the whole school will fall, and we remain with nowhere to learn in.

When it rains, the water comes in these holes.

The reason for this picture is because we can die when the classes fall, it is not safe.

This roof can fall, look at the roof, the water comes in and breaking the roof more, it can fall on us when we are learning.

These comments illustrate the safety concerns the children have about the state of their school buildings. From these comments, we establish that to leapfrog the standards of education in rural schools, good classrooms with windows and non-dilapidated walls and roof are fundamental, according to the learners. It is also important to note that these learners actively reflect on these conditions daily, and their level of awareness regarding the unconducive infrastructure points to social justice and the need for government to prioritise the improvement of the appalling infrastructure in rural schools.

Ogungbemi et al. (2014) asserted that adequate provision of infrastructure enhances the quality of life while improving the quality of basic services, which, in this context, is rural education. We argue that the infrastructural impediments identified by the learners are due to rural schools being marginalised and underdeveloped. The inequality facing rural schools is related to the special characteristics that impede resource accessibility and government service delivery while upholding inequality and social segregation through education.

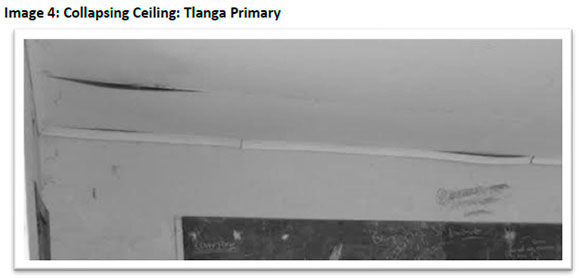

The issue of dilapidated buildings was also mentioned by children from Tlanga Primary where one of the learners reflected on Image 4 saying:

I always look up to see if the roof is not falling on us, I have seen in movies buildings falling, this classroom can fall on us.

The principle of language for symbolic interactionism is important here to make sense of the learner's choice of words (Denzin, 2017). The words "I always look up" and "this classroom can fall on us" illustrate that learners spend learning time worrying about the condition of their learning environments, which they believe puts their lives at risk. It could be argued that this robs learners of learning opportunities because of divided concentration. While another person could argue that the buildings in the photographs are not the worst, it is important to remember that the events or objects cannot be seen as purely objective but are impacted by the meanings learners ascribe to the conditions of their school buildings (Blumer, 2018).

Furthermore, learners at Tlanga reflected on Image 5 and described the condition of their toilets as follows:

We took this picture because our school is rotten, look at this toilet, it can collapse, or we fall inside.

When we went on a school trip to Pretoria, we saw toilets that flush at the schools we visited; why does ours not flush? Those learners are our age and they use flushing toilets, but ta hina ta nuha [ours stink], loko u nghena u huma ukha u nuha [when you enter there, you come out smelling].

The Grade R can fall in there, at least us, we are a bit bigger you see.

The learner's choice of words, "our school is rotten," signifies that they consider the toilet to be unpleasant and that they are fearful that they will lose their lives. We see this infrastructural constraint as a violation of Section 29 of the South African Constitution (RSA, 1996a) and South African Schools Act (RSA, 1996b), which require equal access to quality education, educational opportunities, and learning opportunities.

Gardiner (2017) contended that the socioeconomic conditions facing rural areas impinge on the quality of education offered to rural learners. He considered the geographic marginalisation of rural areas and schools as a key hindrance to good infrastructure in those schools. This resonates with Badat and Sayed's (2014) iteration that the geographic disparities between rural and urban areas constrain the opportunities for quality and equality in educational outcomes in rural areas. Without homogenising rural schools, we argue that policymakers need to configure strategies to bridge the infrastructural gaps that exist between rural schools and their urban counterparts, especially if the urgency of ensuring social justice and transformation is seriously considered. The information provided by the learners illustrates the urgent need for national government to address these identified circumstances to improve the educational opportunities for rural learners and make education equitable across contexts. The following section focuses on learners' reflections about learning in multi-grade and overcrowded classrooms, which they believe constrain the educational opportunities they receive.

Learning in Multi-Grade Overcrowded Classrooms

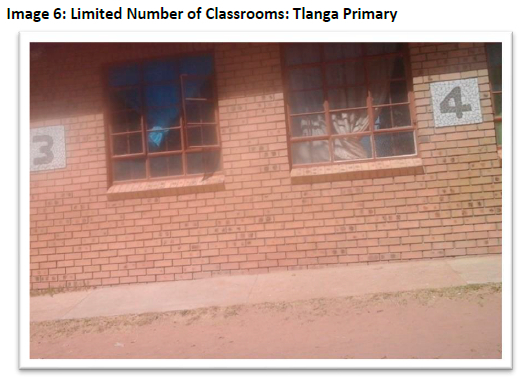

Rural education research in South Africa suggests that rural schools continue to have large class sizes and a shortage of teachers (du Plessis & Mestry, 2019; Myende & Hlalele, 2018). Other photographs learners presented and reflected upon pointed to the learning space in terms of the size of the classrooms in relation to the number of learners in the classrooms. The learners commented that the classroom accommodation is inadequate as they are overcrowded. The overcrowded classrooms, coupled with multi-grade learning environments, were cited by learners as a hindrance to their learning. Images 6 and 7 were captured by the learners at Tlanga Primary school to depict the multi-grade learning conditions in their schools, which they view as constraining effective learning. For ethical purposes, Image 7 is not attached in this paper because it showed learners' faces. Of importance to note is that the classroom was overcrowded, with some of the learners sitting on the floor. Reflecting on Image 6, one learner stated:

We are learning in the same class with the Grade 3, we can hear what their teacher is saying and sometimes when we know the answer we answer, we know those things.

Similarly, another learner commented on Image 6 indicating:

Our class is too full, but we don't divide because we only have small number of rooms.

These statements reveal that the children view the conditions they learn under as not being conducive for their learning.

While the answering of questions by learners from a different grade could be interpreted as helpful for the lower grade, it could equally be seen as disruptive because Grade 4 learners are tending to focus on the Grade 3 learners, resulting in them missing out on the content for their own grade. The following excerpts further illustrate learners' reflections on Image 6:

There is many of us in one class, there is only one class for grades, so they make us learn under one room with Grade 3. I don't like that because we are learning with children.

You see these numbers, there are only four grades in our school, that's what it shows . . . so when we pass Grade 4, we go to another primary school, it is not nice, they should build more classes here so we finish Grade 7 here.

Little et al. (2006) saw multi-grade classrooms as referring to classroom situations in which one teacher teaches learners from more than one grade level in the same classroom. Similarly, Makoelle and Malindi (2014) described multi-grade classrooms as learning environments in which a single classroom space contains learners from multiple grades. It should be noted that previous studies on multi-grade and overcrowded classrooms have predominantly been from the teachers' viewpoint (Hyry-Beihammer & Hascher, 2015; Kivunja & Sims, 2015; Mulaudzi, 2016), overlooking learners' views and experiences of these teaching and learning situations. The information provided by the learners during photo-elicitation interviews demonstrated that learners consider that overcrowded and multi-grade classrooms constrain effective learning. We recognise that previous studies have identified advantages of multi-grade teaching-flexible schedules for teachers, opportunities for self-directed learning, and a less formal classroom situation (Makoelle & Malindi, 2014; Taole & Mncube, 2012)-however, the situation of multi-grade learning and overcrowded classrooms in rural classrooms is not through choice but dictated by the lack of sufficient classroom accommodation. This further reinforces the need for government to address the infrastructural challenges facing the majority of rural schools in order to improve the educational opportunities.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Researching with children is a limited but developing practice in educational research. In the current study, we incorporated Grade 4 rural learners into participatory research through creating meaningful and ethical spaces to explore issues relevant to them. Using photo-elicitation interviews, we gained insight into learners' experiences and views of what it means to learn in rural schools and classrooms. Framed by the social interactionist perspective, learners' participation was built on the understanding that they are competent thinkers, social actors, and rights holders. The information provided by the learners demonstrates that rural schools should be prioritised in improving the infrastructure if the urgency of addressing social justice and equity is considered. We found it helpful to create research opportunities with young learners to explore issues that affect their learning and to actively participate in research.

It is important for education researchers to rethink spaces for children's participation in research, particularly in rural areas and schools, to gain insights into how they view their learning contexts. This implies the need to develop research studies that are built on the understanding that young learners are aware of the social objects and events that impact their learning. We argue that we need to rethink and restructure the role of rural children as partners in research and embrace the epistemological position that they can critically reflect on the issues that affect them.

References

Badat, S., & Sayed, Y. (2014). Post-1994 South African education: The challenge of social justice. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 652(1), 127-148. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716213511188 [ Links ]

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191-215. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191 [ Links ]

Blumer, H. (1969). Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method. Prentice Hall.

Blumer, H. (1986). Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method. University of California Press.

Blumer, H. (2018). Symbolic interaction. In R. W. Budd & B. D. Ruben (Eds.), Interdisciplinary approaches to human communication (2nd ed., pp. 135-154). Routledge.

Carter, B., & Ford, K. (2013). Researching children's health experiences: The place for participatory, child-centered, arts-based approaches. Research in Nursing & Health, 36(1), 95-107. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.21517 [ Links ]

Carter, M. J., & Fuller, C. (2016). Symbols, meaning, and action: The past, present, and future of symbolic interactionism. Current Sociology, 64(6), 931-961. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392116638396 [ Links ]

Christensen, J. H., Mygind, L., & Bentsen, P. (2015). Conceptions of place: Approaching space, children and physical activity. Children's Geographies, 13(5), 589-603. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2014.927052 [ Links ]

Colliver, Y., & Fleer, M. (2016). "I already know what I learned": Young children's perspectives on learning through play. Early Child Development and Care, 186(10), 1559-1570. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2015.1111880 [ Links ]

Danaher, P. A. (2020). Researching with children and marginalised youth: Introduction. In D. L. Mulligan & P. A. Danaher (Eds.), Researching within the educational margins: Strategies for communicating and articulating voices (p. 41). Palgrave.

Denzin, N. K. (2017). Symbolic interactionism and ethnomethodology. In J. D. Douglas (Ed.), Everyday life (pp. 258-284). Routledge.

du Plessis, P. (2014). Problems and complexities in rural schools: Challenges of education and social development. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(20), 1109-1117. http://dx.doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n20p1109 [ Links ]

du Plessis, P., & Mestry, R. (2019). Teachers for rural schools: A challenge for South Africa. South African Journal of Education, 39(1), 1-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v39ns1a1774 [ Links ]

Farrugia, D. (2014). Towards a spatialised youth sociology: The rural and the urban in times of change. Journal of Youth Studies, 17(3), 293-307. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2013.830700 [ Links ]

Fattore, T., Fegter, S., & Hunner-Kreisel, C. (2019). Children's understandings of well-being in global and local contexts: Theoretical and methodological considerations for a multinational qualitative study. Child Indicators Research, 12(5), 385-407. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12187-018-9594-8 [ Links ]

Fattore, T., Mason, J., & Watson, E. (2012). Locating the child centrally as subject in research: Towards a child interpretation of well-being. Child Indicators Research, 5(3), 423-435. https://idp.springer.com/authorize/casa?redirect url=https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12187-012-9150-x&casa [ Links ]

Ferreira, J. M., Karila, K., Muniz, L., Amaral, P. F., & Kupiainen, R. (2018). Children's perspectives on their learning in school spaces: What can we learn from children in Brazil and Finland? International Journal of Early Childhood, 50, 259-277. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/250156626.pdf [ Links ]

Fink, E. L. (2016). Symbolic Interactionism. In C. R. Berger & M. E. Roloff (Eds.), The international encyclopedia of interpersonal communication. (pp. 1-13). John Wiley & Sons.

Ford, K., Bray, L., Water, T., Dickinson, A., Arnott, J., & Carter, B. (2017). Auto-driven photo elicitation interviews in research with children: Ethical and practical considerations. Comprehensive Child and Adolescent Nursing, 40(2), 111-125. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694193.2016.1273977 [ Links ]

Gardiner, A. E. M. (2017). The socio-economic wellbeing of small mining towns in the Northern Cape [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Stellenbosch University, South Africa. [ Links ]

Graham, A., Powell, M. A., & Taylor, N. (2015). Ethical research involving children: Putting the evidence into practice. Family Matters, 96, 23-28. https://aifs.gov.au/research/family-matters/no-96/ethical-research-involving-children [ Links ]

Grant, T. (2017). Participatory research with children and young people: Using visual, creative, diagram, and written techniques. In T. Skelton, R. Evans, & L. Holt (Eds.), Methodological approaches: Geographies of children and young people (vol. 2, pp. 261-284). Springer.

Grau, V., & Whitebread, D. (2012). Self and social regulation of learning during collaborative activities in the classroom: The interplay of individual and group cognition. Learning and Instruction, 22(6), 401-412. https://www.academia.edu/download/75709381/j.learninstruc.2012.03.00320211204-13999-1xdocpo.pdf [ Links ]

Honkanen, K., Poikolainen, J., & Karlsson, L. (2018). Children and young people as co-researchers: Researching subjective well-being in residential area with visual and verbal methods. Children's Geographies, 16(2), 184-195. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2017.1344769 [ Links ]

Hopkins, E. A. (2008). Classroom conditions to secure enjoyment and achievement: The pupils' voice. Listening to the voice of Every Child Matters. Education 3-13, 36(4), 393-401. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03004270801969386 [ Links ]

Hyry-Beihammer, E. K., & Hascher, T. (2015). Multigrade teaching in primary education as a promising pedagogy for teacher education in Austria and Finland. In C. J. Craig & L. Orland-Barak (Eds.), International Teacher Education: Promising Pedagogies (Part C, pp. 89-113). Emerald.

John-Akinola, Y. O., Gavin, A., O'Higgins, S. E., & Gabhainn, S. N. (2014). Taking part in school life: Views of children. Health Education, 114(1), 20-42. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/HE-02-2013-0007 [ Links ]

Kak, S., & Gond, S. (2015). ICT for service delivery in Rural India: Scope, challenges and present scenario. IOSR Journal of Computer Engineering, 17(6), 12-15. https://www.academia.edu/download/47101213/B017611215.pdf [ Links ]

Kivunja, C., & Sims, M. (2015). Perceptions of multigrade teaching: A narrative inquiry into the voices of stakeholders in multigrade contexts in rural Zambia. Higher Education Studies, 5(2), 10-20. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1075120 [ Links ]

Lapenta, F. (2011). Some theoretical and methodological views on photo-elicitation. In E. Margolis & L. Pauwels (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of visual research methods (vol. 1, pp. 201-213). SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446268278

Leinonen, J., & Venninen, T. (2012). Designing learning experiences together with children. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 45, 466-474. https://doi.org/10.1016/Lsbspro.2012.06.583 [ Links ]

Lifumbo, F. M. (2016). Implementing inclusive education for persons with disabilities in Lusaka, Zambia: A symbolic interactionist perspective [Unpublished master's thesis]. Oslo and Akershus University, Norway. [ Links ]

Little, A. W., Pridmore, P., Bajracharya, H., & Vithanapathirana, M. (2006). Learning and teaching in multigrade settings: A final report to DFID. London Institute of Education.

Makoelle, T. M., & Malindi, M. J. (2014). Multi-grade teaching and inclusion: Selected cases in the Free State province of South Africa. International Journal of Educational Sciences, 7(1), 77-86. https://doi.org/10.1080/09751122.2014.11890171 [ Links ]

Mandleco, B. (2013). Research with children as participants: Photo elicitation. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing, 18(1), 78-82. https://doi.org/10.1111/jspn.12012 [ Links ]

Marcus, M., Haden, C. A., & Uttal, D. H. (2018). Promoting children's learning and transfer across informal science, technology, engineering, and mathematics learning experiences. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 175, 80-95. https://doi.org/10.1111/jspn.12012 [ Links ]

Mbanda, V., & Ncube, S. (2021). CGE analysis of rural economic development through agriculture policy in South Africa: A focus on poverty, inequality, and gender. Partnership for Economic Policy. https://policycommons.net/artifacts/2195449/cge-analysis-of-rural-economic-development-through-agriculture-policy-in-south-africa/2951841/fragments/

Mbhiza, H. (2021). Rural teachers' teaching of algebraic functions through a commognitive lens. Interdisciplinary Journal of Rural and Community Studies, 3(1), 10-20. https://doi.org/10.51986/ijrcs-2021.vol3.01.02 [ Links ]

Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self, and society: From the standpoint of a social behaviorist. (C. W. Morris, Ed.). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Meo, A. I. (2010). Picturing students' habitus: The advantages and limitations of photo-elicitation interviewing in a qualitative study in the city of Buenos Aires. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 9(2), 149-171. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691000900203 [ Links ]

Miller, K. (2016). Learning about children's school preparation through photographs: The use of photo elicitation interviews with low-income families. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 14(3), 261-279. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X14555703 [ Links ]

Mulaudzi, M. S. (2016). Challenges experienced by teachers of multi-grade classes in primary schools at Nzhelele East Circuit [Unpublished master's thesis]. University of South Africa. [ Links ]

Murphy, C., Smith, G., & Broderick, N. (2021). A starting point: Provide children opportunities to engage with scientific inquiry and nature of science. Research in Science Education, 51(9), 1759-1793. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11165-019-9825-0 [ Links ]

Murris, K., & Muller, K. (2018). Finding child beyond "child": A posthuman orientation to foundation phase teacher education in South Africa. In V. Bozalek, R. Braidotti, M. Zembylas, & T. Shefer (Eds.), Socially just pedagogies: Posthumanist, feminist and materialist perspectives in higher education (pp. 151-171). Palgrave MacMillan.

Myende, P. E., & Hlalele, D. (2018). Framing sustainable rural learning ecologies: A case for strength-based approaches. Africa Education Review, 15(3), 21-37. https://doi.org/10.1080/18146627.2016.1224598 [ Links ]

Nansen, B., Gibbs, L., MacDougall, C., Vetere, F., Ross, N. J., & McKendrick, J. (2015). Children's interdependent mobility: Compositions, collaborations and compromises. Children's Geographies, 13(4), 467-481. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2014.887813 [ Links ]

Nelson Mandela Foundation. (2005). Emerging voices: A report on education in South African rural communities. HSRC Press.

Nkambule, T. C. (2017). Student teachers' perceptions of a Wits rural teaching experience project: What to learn and improve. South African Journal of Higher Education, 31(1), 191-206. https://www.journals.ac.za/sajhe/article/view/901 [ Links ]

Ogungbemi, A. A., Bubou, G. M., & Okorhi, J. O. (2014). Revitalizing infrastructure for rural growth and sustainable development. Industrial Engineering Letters, 4(10), 23-30. https://www.academia.edu/26045699/Revitalizing_Infrastructure_for_Rural_Growth_and_Sustainable_Development [ Links ]

Pálmadóttir, H., & Einarsdóttir, J. (2016). Video observations of children's perspectives on their lived experiences: Challenges in the relations between the researcher and children. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 24(5), 721-733. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2015.1062662 [ Links ]

Pinter, A., Kuchah, K., & Smith, R. (2013). Researching with children. ELTJournal, 67(4), 484-487. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/elt/cct033 [ Links ]

Poulou, M. S. (2017). An examination of the relationship among teachers' perceptions of social-emotional learning, teaching efficacy, teacher-student interactions, and students' behavioral difficulties. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 5(2), 126-136. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2016.1203851 [ Links ]

Powell, M. A., Taylor, N., & Smith, A. B. (2013). Constructions of rural childhood: Challenging dominant perspectives. Children's Geographies, 11(1), 117-131. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2013.743285 [ Links ]

Qutoshi, S. B. (2018). Phenomenology: A philosophy and method of inquiry. Journal of Education and Educational Development, 5(1), 215-222. http://dx.doi.org/10.22555/joeed.v5i1.2154 [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa. (1996a). Constitution of the Republic of South Africa. https://www.gov.za/documents/constitution-republic-south-africa-1996

Republic of South Africa. (1996b). South African Schools Act 84 of 1996. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcisdocument/201409/act84of1996.pdf

Republic of South Africa. (2012). National development plan 2030. https://www.gov.za/issues/national-development-plan-2030

Robinson, C. (2014). Children, their voices and their experiences of school: What does the evidence tell us? Cambridge Primary Review Trust. https://cprtrust.org.uk/wpcontent/uploads/2014/12/FINAL-VERSION-Carol-Robinson-Children-their-Voices-and-theirExperiences-of-School.pdf

Seamon, D. (2018). Life takes place: Phenomenology, lifeworlds, and place making. Routledge.

Simmons, C., Graham, A., & Thomas, N. (2015). Imagining an ideal school for wellbeing: Locating student voice. Journal of Educational Change, 16, 129-144. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10833-014-9239-8 [ Links ]

Singh, M. (2022). Teachers lived experiences of teaching and learning in a rural school in the Western Cape. African Perspectives of Research in Teaching & Learning, 6(3), 92-106. https://www.ul.ac.za/aportal/application/downloads/sp_2022_7_Singh-De%20Waal%20article.pdf [ Links ]

Smit, B., & Fritz, E. (2008). Understanding teacher identity from a symbolic interactionist perspective: Two ethnographic narratives. South African Journal of Education, 28(1), 91-102. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/saje/article/view/25147 [ Links ]

Stryker, S. (2017). Symbolic interactionism: Themes and variations. In M. Rosenberg & R. H. Turner (Eds.), Social psychology: Sociological perspectives (pp. 3-29). Routledge.

Taole, M., & Mncube, V. S. (2012). Multi-grade teaching and quality of education in South African rural schools: Educators' experiences. Studies of Tribes and Tribals, 10(2), 151-162. https://doi.org/10.1080/0972639X.2012.11886653 [ Links ]

Tirosh, D., Tsamir, P., Tabach, M., Levenson, E., & Barkai, R. (2012). Preschool children's performance and self-efficacy on mathematical and non-mathematical tasks. Semantic Scholar. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Preschool-children-%27-s-performance-and-on-and-tasks-Tirosh-Tsamir/6196205d9ed31ad72d595c2b8652997ca3894cb4

United Nations. (1989). Convention on the rights of the child. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-child

United Nations. (2008). Consideration of reports submitted by states parties under Article 8 of the optional protocol to the convention on the rights of the child on the involvement of children in armed conflict: Geneva. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/619765?ln=en

Usher, R. (2018). Experience, pedagogy and social practices. In K. Illeris (Ed.), Contemporary theories of learning (pp. 189-203). Routledge.

Vagle, M. D. (2014). Craftingphenomenological research. Left Coast Press.

van Manen, M. (2017). Phenomenology in its original sense. Qualitative Health Research, 27(6), 810825. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732317699381 [ Links ]

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

Wells, F., Ritchie, D., & McPherson, A. C. (2013). "It is life threatening but I don't mind": A qualitative study using photo elicitation interviews to explore adolescents' experiences of renal replacement therapies. Child: Care, Health and Development, 39(4), 602-612. [ Links ]

1 Ethical clearance number: 2015ECE006S