Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

The African Journal of Information and Communication

versão On-line ISSN 2077-7213

versão impressa ISSN 2077-7205

AJIC vol.32 Johannesburg 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.23962/ajic.i32.16429

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Framings of colourism among Kenyan Twitter users

Caroline KiarieI; Nicola-Jane JonesII

IPostdoctoral Researcher, Media and Cultural Studies, School of Arts, University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN) Durban, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7295-6533

IIAssociate Professor, School of Arts, University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN) Pietermaritzburg, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2796-4120

ABSTRACT

Colourism is a form of discrimination where dark-skinned people of colour are perceived and treated less favourably than lighter-skinned people of the same ethnic group or racial classification. Much of the scholarly literature on colourism is focused on the experiences of African-Americans in the United States, but there is also substantial literature examining colourism's impacts for Americans of Latinx, Indigenous, and Asian ancestry, and for people of colour in the Caribbean, Latin America, the UK, Europe, the Asia-Pacific, and parts of Africa. To date, there has not been significant scholarly focus on the phenomenon as it manifests in Kenya. This study sought to address that research gap by: (1) exploring the extent to which colourism is an issue of concern among Kenyan users of the social media platform Twitter; and (2) identifying the main colourism themes present in posts in the Kenyan Twitter ecosystem. The research entailed mining Kenyan Twitter data for nine and a half months in 2022, which resulted in the documentation of 7,726 unique posts on elements of colourism, as posted from 5,094 unique Twitter user accounts. Using inductive frame analysis, three predominant thematic categories were identified across the posts: (1) colourism perceptions; (2) colourism experiences; and (3) colourism influence. The frame analysis also uncovered sub-themes in each of these three broad categories. It was found that most of the Kenyan Twitter users who tweeted on matters of colourism during the period studied both acknowledged the existence of colourism's manifestations and at the same time rejected the manifestations, advocating for a future free from such discrimination.

Keywords: colourism, discrimination, perceptions, experiences, influence, Twitter, Kenya, frame analysis

1. Introduction

Colourism is the phenomenon where dark-skinned people of colour are discriminated against in ways that are not experienced by light-skinned people from the same ethnic or racial grouping (Hunter, 2013). Hunter (2013) adds that colourism is a discriminatory social process that is experienced in areas such as income level, access to education, criminal justice sentencing, housing, and marriage. The origins of the identification of the concept of colourism are often attributed to the work of African-American novelist Alice Walker, who wrote of "prejudicial or preferential treatment of same-race people based solely on their color" (Walker, 1983, p. 290).

Much of the key scholarship on colourism has, to date, been done by American academics, thus leading to a strong focus on colourism's manifestations for African-Americans and Latinx, Indigenous, and Asian Americans. At the same time, however, important scholarly contributions have looked at the presence and effects of colourism in Latin America, the Caribbean, the UK, Europe, the Asia-Pacific, and parts of Africa (see, for example, Anjari, 2022; Gabriel, 2007; Hall, 2021; Kinuthia et al., 2023; Mishra, 2015; Tekie, 2020).

In reflecting on the presence of colourism on the African continent, US scholar Norwood (2015, p. 587) writes:

My visits to Ghana, to South Africa, and to Zambia in the mid-2000s opened up a whole new world to me. Even there, in a world of Black and shades of brown, lighter was better. I am embarrassed to admit that this shocked me. I did not understand the continued hold and power that the legacy of colonization had on African communities, no longer under colonial rule.

In the Kenyan context, discussions of colourism are increasingly common in the media (see, for example, Kanja, 2020; Obino, 2021; Ongaji, 2019; Simiyu, 2023), but not to a great extent in the scholarly literature (see, as exceptions, Kinuthia et al., 2023; Okango, 2017). To begin to address this gap, this study sought to explore colourism discourses in one particular context where trends in public discussion can be detected: among Kenyan users of the social media platform Twitter (re-named X in July 2023, after the conclusion of the research). The objective of this study was twofold: to determine the extent to which colourism was a topic of discussion on Twitter in Kenya; and to determine the main framings being adopted and used in the tweets related to colourism matters.

In this article, we briefly survey some of the key literature on colourism's sociocultural and socioeconomic dimensions. After that, we explore the frame analysis framework as a methodology, which was applied to the study. Based on the findings of the study, different themes within colourism are discussed and conclusions are offered.

2. Colourism's sociocultural and socioeconomic dimensions

Colourism in the United States has many of its roots in the transatlantic slave trade, where slave owners favoured light-skinned slaves over those with dark skin (Hunter, 2013). Light-skinned slaves were often rewarded by being allowed to work in their slave owners' houses, by being assigned more skilled work, and/or by being accorded more learning opportunities (Hunter, 2004). In the contemporary era, it has been found that African-Americans with mixed ancestry, and, for example, fairer-skinned people of Latin American origin, are often privileged over people perceived to be more purely African or black (Williamson, 1995; Telles & Ortiz, 2008). In their study of employment inequalities and race in the US, Goldsmith et al. (2006) identify wage discrimination where light-skinned black males earn more than their darker-skinned counterparts. Dhillon-Jamerson (2018) identifies the role of colourism as a contributor to class divisions.

Hunter (2004) finds that light skin is associated with beauty, intellectual capability, and likeability, with the result that light-skinned black people are more welcomed in many social spaces than those with darker skin, and light-skinned black women are more likely than those with dark skin to marry high-status spouses. Mathews and Johnson (2015) find that most African-American men would prefer to marry a lighter-skinned African-American woman, so as to elevate their own status, as light-skinned women are seen as attractive and pleasing to society. Hill (2002) finds that light-skinned women are perceived to be more likeable, honest, cooperative, and desirable as romantic partners (Hill, 2002).

Hunter (1998), in examining colourism ("skin color stratification") as experienced by African-American women, traces its beginnings in the US to "sexual violence against African women by White men during slavery", which was a form of "social control" and "was part of the beginning of the skin color stratification process itself" (1998, pp. 517-18). One obvious result, Hunter (1998) writes, "was the creation of racially mixed children", while the sociological effect "was to systematically privilege lighter-skinned Blacks via their connection with the White slave owner and thus their connection with whiteness" (1998, p. 518).

Keith and Monroe (2016, p. 4) write that, in the US context, "[a] well-regarded cadre of scholars presently assert that when African-Americans, Asians, and Latinos/ as fare comparably well within their ethnoracial group, they tend to have lighter complexions". Keith and Monroe (2016) find the roots of the "skin-tone hierarchy in the United States" in white supremacist ideologies and the dynamics of racial mixing during the European colonial era. UK-based writer Gabriel (2007), who explores colourism in the African diaspora settings of the US, Latin America, Jamaica, and Britain, frames colourism as "a manifestation of the psychological damage caused by centuries of enslavement which created social hierarchies based on skin colour [and] maintain an invisible presence in our psyches" (2007, p. 2).

While colourism has been found to be experienced by both women and men, the biases are more harmful to women-chiefly with respect to notions of beauty, the dynamics of spouse selection, and socioeconomic status (Mathews & Johnson, 2015). Mathews and Johnson (2015) find evidence of African-American women desiring dark-complexioned African-American men, and the authors conjecture that "[p] erhaps this is because dark skin as a male attribute has been historically associated with masculinity, strength, and praise" (2015, p. 269). Several studies (Hunter, 1998; Thompson & Keith, 2001; Hill, 2002) have found that an African-American woman's personal self-esteem can be influenced by the lightness or darkness of her skin.

Van Hout and Wazaify (2021) write of efforts to lighten dark skins through bleaching in African countries such as Tanzania, Burkina Faso, Benin, Cameroon, Mali, Senegal, Rwanda, Ghana, South Africa, and Nigeria, as well as in Asian countries such as India, China, Japan, Pakistan, and South Korea. Anjari (2022) examines the origins and evolution of colourism and skin-lightening practices in South Africa, and also explores the strong opposition to these phenomena from the apartheid-era Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) and, in the contemporary era, by Black Lives Matter (BLM) activists. BLM has its origins in the US but in 2020 it became a global movement as countries joined in the protests against racial injustices. Anjari (2022) states that in South Africa, there is a problematic relationship between skin colour and access to socioeconomic opportunities, where the light-skinned are looked up to, leading, in inter alia, to a profitable skin-lightening industry.

In a Tanzanian study, Lewis et al. (2011) link women's use of skin-bleaching to, inter alia, self-objectification, Westernisation, and colonialism. A study by Tekie (2020) sets out findings from research into the harmful impacts of colourism on notions of identity and ethnicity among women in Zanzibar. A Kenyan study by Kinuthia et al. (2023) explores the role of family members and peers in imposing notions of colourism and texturism (focused on hair texture) on young women. The family and peer influences are found to be harmful: "Young women had, therefore, internalized the idea that beauty was represented in either light or medium toned skin and soft hair" (2023, p. 41). Another Kenyan study, by Okango (2017) examines the roles played by colonialism, globalisation, technology use, and TV consumption in encouraging bleaching and other chemical methods for lightening skin among Kenyan women.

3. Frame analysis methodology

Frame analysis, which originated in the work of Goffman (1974), has its roots in agenda-setting theory, which emphasises the ways in which human beings' definitions of reality are shaped by framings they encounter in society and culture around them. Goffman (1974) argues that, through a combination of social construction and reliance on existing frames, human beings adopt and develop frames to make sense of realities they encounter and to guide their everyday lives. Frame analysis can be used, inter alia, to interrogate the effects of audience exposure to an issue via its media coverage (Price & Tewksbury, 1997).

Tewksbury and Scheufele (2019) state that, in frame analysis, the framing effect occurs when a phrase, image, or statement suggests a certain meaning or interpretation to an audience. These authors add that the framing effect can occur via three processes: information effects, persuasion effects, and agenda-setting effects. The common aspect across the three effects is exposure to framings through media consumption. Goffman (1974) points to cultural context as a crucial element in framing. When an audience is exposed to a message, the audience's surrounding culture influences their interpretation of the issue. Gamson and Modigliani (1989) describe this phenomenon as "cultural resonance".

The data for this study's frame analysis of Kenyans' framing of colourism was extracted from the social media platform Twitter. Twitter was selected as a relevant media consumption tool on the grounds that it is, at present, a key media platform for the framing of issues and for audience consumption of, and interaction with, frames (Wasike, 2013). Machine learning was used to mine and analyse the data from Twitter, using the Network Overview, Discovery, and Brandwatch application programming interfaces (APIs). The online data was collected in 2022. In Kenya, internet penetration was estimated at 23.35 million users in January 2022, with an increase of 1.6 million from 2021 to 2022 (Kemp, 2022), meaning that approximately 42% of the Kenyan population was using the internet. The target population for this study was Kenyan-based Twitter users, and there were an estimated 1.35 million such users in January 2022 (Kemp, 2022).

The colourism data was collected between 1 January and 18 October 2022. Keywords and keyword phrases associated with colourism were formulated, resulting in 39 keywords and keyword phrases, such as colorism/colourism, light-skinned, dark-skinned, melanin, brown skin, fair skin, discrimination + color/colour, and Lupita Nyong'o + colorism/colourism, and including Kiswahili phrases such as "rangi ya thao" (referring to the colour of the 1,000-shilling note in Kenyan currency), among others, that were likely to be used in the Kenyan context. (The Kenyan 1,000-shilling note is light brown in colour and commonly associated with light skin tone.) The keywords and keyword phrases were queried using Brandwatch, and the location was limited to Kenya. Brandwatch was used because it enables data to be mined for a long period, in this case for nine and half months.

4. Colourism on Twitter in Kenya: Findings and discussion

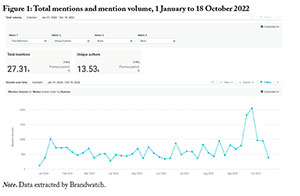

The colourism data mined from Twitter using Brandwatch contained 27,382 mentions by 13,540 unique authors in Kenya, as shown in Figure 1 below. (In the figure, the Twitter handles of the posts are the actual online handles of the Twitter users on the platform as mined by Brandwatch.)

The line graph in Figure 1 shows the monthly volumes of mentions of colourism themes for the study period, with most colourism mentions occurring on 2 October 2022 when there were 2,043 such mentions. On that day, the following tweet was retweeted 229 times:

Sir-Rap-A-Lot @Osama_otero, "Sasa nikisema taste yangu ya madem ni lightskin hiyo ni colourism? So kumaanisha dem akisema hapendi machali wafupi hiyo ni heightism? Mnapenda kuplay victim sana." Twitter, Oct 2, 2022, 11:27 AM

The above tweet, in Kiswahili, translates to: "Now, if I say my taste is light skinned girls, that is colourism? Which means that if a girl says she doesn't like short men, that is heightism? You like playing the victim a lot."

Another tweet on 2 October 2022, which had 196 retweets, was a response to a user seeking to understand the difference between colourism and preference. The response was as follows:

Barry @_barrack_: "Colorism is what dark skinned female[s] feel when they see a dark-skinned man choosing to be with a light-skinned chic [woman]. Preference is when women state the type of man they would consider being with." Twitter, Oct 2, 202212:26 PM

The demographic analysis found that 69% of the originators of the colourism-related tweets self-identified as male, compared to 31% who identified as female. With respect to professions, the top five posters who collectively made 1,567 mentions of colourism themes identified themselves as artists. Executives, scientists and researchers, journalists, and students collectively made 477 colourism mentions. The findings indicate that both the male and female genders, and Twitter platform users from various fields, are contributing to the colourism discussion.

The data was then cleaned to exclude retweets and irrelevant tweets such as promotional material. This reduced the colourism mentions to 7,726, by 5,094 unique authors. After the cleaning, the demographic analysis produced similar results, with 65% male posters and 35% female posters mentioning colourism themes. The top five posters remained the same artists, who had made 476 colourism mentions, while the students had made 122 colourism mentions, and the executives, scientists, researchers and journalists, collectively, had made 345 colourism mentions.

The first objective of the study was to establish whether colourism as a topic of discussion exists in Kenya. The mined data indicated that it exists in Kenya, and that Twitter is used as one of the platforms for the conversations. This supports Norwood's (2015) findings that colourism is prevalent not only in Western countries but also on the African continent. With regard to gender, male users were found to be discussing the subject more than female users. This aligned with the findings from Kiarie's (2020) study of Kenyans' use of social networking sites, which found that males spent more time on social media than females.

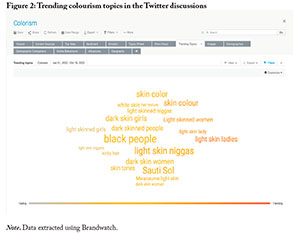

The trending topics in the colourism discussions are highlighted in Figure 2 below, with the larger fonts indicating the most prevalent topics. These prevalent topics included "black people", "light skin niggas", "Sauti Sol" (a Kenyan musical group), "skin color/colour", "dark skin girls", and "light skin ladies".

The topic wheel in Figure 3 provides another representation of the topics of conversation on colourism matters among Kenyan Twitter users. A topic wheel indicates the key topics and sub-topics within conversations, which are segmented using unique parameters (Agnew, 2018). In this case, the key topic within the colourism tweets,was "skin men", as shown in the centre of the topic wheel. The sub-topics include "dark skin", "melanin", "black skin", "light skin", and more sub-topics as one moves to the outer layer of the topic wheel. It should be noted that these words came from the conversations on colourism on Twitter. This shows that the main focus areas of conversations were men's skin colour, light skin, dark skin, melanin, and black skin.

The trending topics and topic wheel visualisations guided this study's theme identification. The first step of the analysis was issue identification, which required identifying the tweets that were in one way or another connected to colourism. As a second step, the frames were identified, with guidance from the trending topics and topic wheel visualisations as shown in Figures 2 and 3. Guided by the literature review and the data collected, we used an inductive approach to identify the primary framing themes, and the following framing themes emerged: (1) colourism perceptions; (2) colourism experiences; and (3) colourism influence.

Colourism perceptions

The tweets identified as falling within this framing theme were those putting forward preference, relationship, and beauty frames in relation to colourism. Tweets touching on preference included the following:

Ben @_benie: "I love lightskin women. It's not colorism, it's just what I prefer. My sister is dark as midnight, I still love her though!" Twitter, Oct 2, 2022, 12:41 PM

Also aligned to the preference frame, several tweets sought to draw a distinction between preference and colourism:

Jesse Jim @iamjessejim: "Preference is: I like a light skinned person because that is my type! Colorism is: I like a light skinned person because a dark skinned person is (all manner of negative traits that could be true or not)! One is out of preference which is fine, the latter out of prejudice!" Twitter, Oct 2, 2022 2:42 PM

MuNdüz @Mtu_Bossman: "I don't believe in colourism, certainly not in the same breathe [sic] as racism, homophobia and sexism. Because at what point does preference make the jump to bias. Yes a majority will prefer lightskin over darkskin, but unlike racism they have nothing against darker skin." Twitter, Apr 23, 2022, 9:08 AM

Rachel Agunda @agundarachel: "Preference is going for or talking about what you prefer and sticking to it. Colorism is hating on and demeaning those with skin tones you do not like just to make the skin tone you prefer like or want you, or to make it known that you prefer the other one." Twitter, Oct 2, 2022, 3:23 PM

Tweets falling within the relationship frame included:

Barry @_barrack_: "Colorism is what dark skinned female[s] feel when they see a dark-skinned man choosing to be with a light-skinned chic [female]." Twitter, Oct 2, 2022, 12:26 PM

Jack Maina @mainabrand: "When women choose tall men over shore [sic] men it's fine. When women choose dark men over light skin it's fine. But when a man chooses a light skin lady over a dark skin its colorism??" Twitter, Oct 2, 2022, 11:57 AM

KonzoDavies @KonzoDavies: "Y'all are the same people that will only date outside your race but the moment a black man says they like light skin women y'all turn to be a bunch of activist[s] and start lecturing him on colorism!" Twitter, Sep 22, 2022, 8:44 AM

One male user set forth an opposing frame, advocating for relationships with dark-skinned women:

Lord @nairobilord: "Light skinned women are the worst. They feel entitled. They think they are God's gift to men. Dark women make the best partners. Just keep them happy with themselves." Twitter, Oct 15, 2022, 11:06 AM

The final frame under this perception framing theme was beauty. One user strongly objected to the frame wherein light-skinned women are regarded as more beautiful than those with dark skin:

Nelly Alili @NellyAlili: "This thing of lightskinned girls are beautiful but darkskins have good personalities is not okay. This kind of thinking still feeds into the narrative of 'darkskins are ugly' Someone's skin color has nothing to do with nothing." Twitter, Mar 3, 2022, 5:18 PM

Also rejecting the light-skin-is-beautiful framing imposed on black women, one male tweeted the following in respect of his dark-skinned spouse:

Tyrion @Maxwizy: "For my wife I also noticed she admired light skin women and wished that she was also light skin [...] I had to convince her multiple times that she is also beautiful and that light doesn't guarantee beauty [... ] I agree we need to embrace and appreciate dark skin women too." Twitter, Oct 2, 2022, 2:41 PM

In line with the aforementioned tweets' rejection of the framing in which light skin is held up as an ideal for beauty in black women, many tweets extolled the virtues of melanin-the pigment whose quantity dictates darkness of skin. One of the tweets, which was widely shared and re-tweeted, provided a video of a white woman applying sunscreen lotion. After the woman in the video is finished applying the lotion on most parts of her body, she shares some of it with a young black boy. The boy applies it only to the palms of his hands and the soles of his feet (signifying that people with black skin do not need to apply any lotion as melanin protects them from sunburn). Most of the comments on the video tweet included the word "melanin", with mention of melanin's positive attributes and even some claims that lack of melanin could be associated with certain diseases. Another tweet that was widely re-tweeted referenced the song "Melanin", a track by Sauti Sol and featuring Patoranking. The song refers to dark-skinned women as "melanin girls" and praises them. One of the tweets extolling the virtues of melanin read as follows:

TonyCaston Mwirigi @TonycastonM: "But we're all rich in melanin! Proud African!" Twitter, Mar 1, 2022, 5:57 AM

We see here in the tweets falling under the "colourism perceptions" framing theme that there was, among the Kenyan Twitter, predominantly a rejection of, and counter-framing response to, the light-skin-is-beautiful framing experienced by black women. These framings in the Kenyan Twitter users' tweets acknowledged the framing we saw above in the US findings of the Mathews and Johnson (2015) study, where lightness of skin colour was a powerfully positive factor in African-American men's perceptions of the attractiveness of African-American women. But, at the same time, the Kenyan users proposed a counter-framing, in which darker skin is beautiful for black women and also, as expressed through the pro-melanin frame, for black men.

Colourism experiences

In this colourism experiences framing theme, employment and discrimination were the dominant frames. One element that emerged in the employment frame was the Kenyan government's decision to employ doctors from Cuba, whom the user refers to as having "no melanin":

gina linetti's twinflame @winter_emmm: "They're not any better. Incompetence in our hospitals is because of bad management and low pay. They're employing Cuban doctors and I'm sure they're being paid in dollars. Hii imposter syndrome yetu as a country ya kubelieve someone with no melanin knows more than us should stop." Twitter, May 3, 2022, 1:31 PM

The last sentence in the above tweet translates to: "This is imposter syndrome of ours as a country where we believe someone with no melanin is better than us should stop." Another user writing within the employment frame criticised the advantages bestowed upon light-skinned black women:

Mabinda @cmabinda: "And studies show that in interviews, light skinned women with straight hair are [more] likely to advance to [the] interview stage and get the job than dark skinned women with kinky hair so this light skin issue colorism is something that is reinforced by white media. http:// mabinda.com." Twitter, Jan 20, 2022, 12:41 PM

Also within the employment frame, another user argued that light-skinned black women mistreat their black male counterparts in the workplace:

nickson mwangale @nicksonmwangale: "Miss mandi is just an example of how light skinned pretty women who get preferential treatment at the job bully the hell out of their male counterparts." Twitter, Jan 20, 2022, 5:33 PM

In respect of the discrimination frame, one user rejected and mocked the frame with these words:

Wdxsm @delashoo: "Blacks are hated for having more melanin pigment, crazy!?" Twitter, Mar 4, 2022, 4:45 AM

One tweet approached the discrimination frame through an international lens:

Fred @SirAlfred006: "Light skinned girls have an upper hand almost everywhere compared to black skinned. Kenya and beyond." Twitter, Apr 3, 2022, 6:22 PM

Another user adopted a defeatist stance in relation to the discrimination frame:

Sewe Saldanha @SeweS_: "As long as Africans are poor (whether it's a melanin thingie or this misguided black nationalism) nobody will ever want them anywhere and thus will keep dying like flies attempting to swim to Europe. And that is just how things are, melanin notwithstanding." Twitter, Jul 1, 2022, 5:40 PM

Here, in the tweets falling under the "colourism experiences" framing theme, we see, among the Kenyan Twitter users, a mix of both acknowledgement and critique of colourism framings.

Colourism influence

The frames identified under this framing theme were children and bleaching. With respect to the children frame, one user tweeted as follows:

Nelly Alili @NellyAlili: "Some lightskinned women have attested that there's pressure to reproduce only lightskinned babies. This kind of pressure is rooted in colorism." Twitter, Jul 23, 2022, 7:28 PM

The same Twitter user added that:

Nelly Alili @NellyAlili: "Colorism in families, is not that the parent hates the darkskinned child, it's [that] they treat the lightskinned child better; more care/affection. Which is also a problem." Twitter, Mar 15, 2022, 7:42 PM

Also addressing the children frame, another user stated:

Carlisle @cryptonait: "A great but weighted question. Most of it has been internalized like growing up dark where all my siblings took after my mom who is extremely light skin. then her & co constantly calling me thin then fat when I started puberty It's taken me years to be comfortable in my body as is." Twitter, Jun 24, 2022, 11:42 AM

With respect to the bleaching frame, users wrote as follows:

Siennaxgold @luckyredrebel: "People shame girls for bleaching badala mshame [instead shame] the colourists who made fun of their dark skin, called them ugly and made them feel inferior to lightskinned girls which is all just a product of racism juu mliambiwa [because you were told] white skin is superior mkaamua [you decided] it's the hill you'll die on lol." Twitter, Aug 30, 2022, 11:07 AM

Uju Anya @UjuAnya: "Let's save some of our shock and disgust for the society compelling people to burn and mutilate themselves to lighten skin. Let's not place all blame on somebody trying to get the better treatment, better jobs, better dating prospects, better life they see attached to light skin." Twitter, Oct 16, 2022, 6:38 PM

Luna M.N @MphoMoalamedi: "Until you guys are honest with yourselves about how horrible you treat dark skin people in this country, especially women, then leave conversations about skin bleaching alone. From birth, dark skinned peoole [sic] are bullied and even profiles [sic] as foreigners and experience so much abuse." Twitter, Jan 15, 2022, 12:46 PM

Mass . Acceleration @CraigParis7: "Bleaching is not immoral as such. Colorism that forces people to bleach is what's immoral. Let's not blame dark-skinned girls who are ostracized in society for dark skin tones that are considered undesirable. This forces them to bleach to be desirable. It is a real problem." Twitter, Sep 7, 2022, 11:34 AM

Meanwhile, one user, apparently seeking to undermine the anti-bleaching framing, made light of a tweet pointing to the harms of bleaching products:

First Doktor @firstdoktor: "Bleaching can thin your skin! Bleaching can scar your skin! Bleaching can harm your liver! Bleaching can harm your kidney! Bleaching can cause skin cancer! Bleaching can malform your unborn baby!" Twitter, Feb 7, 2022, 2:26 PM

In all but the final tweet cited above under the "colourism influence" framing theme, we see an acknowledgment of, and also defiance towards, the elements of colourism that harm dark-skinned children in Kenyan families and the colourism that makes some Kenyan women seek to lighten their skin.

5. Conclusions

This study explored the extent to which colourism is a topic of discussion among Kenyan Twitter users, and it also identified, via frame analysis, the main thematic elements in Kenyan Twitter users' discourses on colourism matters. The fact that during the nine and half months studied in 2022, there were 7,726 unique Kenyan posts linked to elements of colourism, and 5,094 unique Twitter user accounts linked to these posts, indicates that colourism is indeed a prominent topic of discussion in the Kenyan Twitter ecosystem. Through frame analysis of the posts, it was found, through an inductive approach, that the discussions could broadly be broken down into three predominant thematic categories: (1) colourism perceptions; (2) colourism experiences; and (3) colourism influence. Across all three themes, it was notable how much passion, and oftentimes pain, was elicited by discussions of colourism.

The frame analysis of the tweets indicated a strong presence of perceived and/or directly experienced colourism among many Kenyan Twitter users, with effects identified in areas such as employment, procreation, and skin bleaching. However, the framings were by no means monolithic. For instance, while some of the Twitter users framed colourism as a form of harmful discrimination, others framed it more benignly as merely an element of preference. Most significantly, among the Kenyan Twitter users active during the period studied who addressed colourism issues, there was a predominant current of rejection and defiance in response to manifestations of colourism in Kenyan society.

References

Agnew, P. (2018, October 3). Introducing the topic wheel. Brandwatch. https://www.brandwatch.com/blog/introducing-the-topic-wheel/

Anjari, S. (2022). From Black Consciousness to Black Lives Matter: Confronting the colonial legacy of colourism in South Africa. Agenda, 36(4), 158-169. https://doi.org/10.1080/10130950.2022.2166240 [ Links ]

Baeza-Yates, R. (2018). Bias on the web. Communications of the ACM, 61(6), 54-61. https://doi.org/10.1145/3209581 [ Links ]

Carty-Williams, C. (2019, October 3). The interview: Lupita Nyong'o on female warriors, colourism and the problem with fairly tales. The Times.https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/the-interview-lupita-nyongo-on-female-warriors-colourism-and-the-problem-with-fairy-tales-2wjlxj35p

Chacha, B. K., Chiuri, W., & Nyangena, K. O. (2020). Racial and ethnic mobilization and classification in Kenya. In Z. L. Rocha, & P. J. Aspinall (Eds.), The Palgrave international handbook of mixed racial and ethnic classification (pp. 517-534).https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-22874-327

Chong, D., & Druckman, J. N. (2007). Framing theory. Annual Review of Political Science, 10(1), 103-126. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.10.072805.103054 [ Links ]

Dhillon-Jamerson, K. K. (2018). Euro-Americans favoring people of color: Covert racism and economies of white colorism. American Behavioral Scientist, 62(14), 2087-2100. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764218810754 [ Links ]

Gabriel, D. (2007). Layers of blackness: Colourism in the African diaspora. Imani Media.

Gamson, W. A., & Modigliani, A. (1989). Media discourse and public opinion on nuclear power-A constructionist approach. American Journal of Sociology, 95(1), 1-37. https://doi.org/10.1086/229213 [ Links ]

Gullickson, A. (2005). The significance of color declines: A re-analysis of skin tone differentials in post-civil rights America. Social Forces, 84(1), 157-180. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2005.0099 [ Links ]

Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. Harvard University Press.

Goldsmith, A. H., Hamilton, D., & Darity, W. (2006). Shades of discrimination: Skin tone and wages. American Economic Review, 96, 242-245. https://doi.org/10.1257/000282806777212152 [ Links ]

Hall, R. E. (2021). The historical globalisation of colorism. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-84335-9

Hall, R. E. (2023). Interdisciplinary perspectives on colorism: Beyond black and white. Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003302889

Hill, M. E. (2002). Skin color and the perceptions of attractiveness among African Americans: Does gender make a difference? Social Psychology Quarterly, 65(1), 77-91. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090169 [ Links ]

Hunter, M. L. (1998). Colorstruck: Skin color stratification in the lives of African American women. Sociological Inquiry, 68(4), 517-535. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-682X.1998.tb00483.x [ Links ]

Hunter, M. (2004). Light, bright, and almost white: The advantages and disadvantages of light skin. In C. Herring, V. M. Keith, & H. D. Horton (Eds.), Skin/deep: How race and complexion matter in the "color-blind" era (pp. 22-44). University of Illinois Press.

Hunter, M. (2007). The persistent problem of colorism: Skin tone, status, and inequality. Sociology compass, 1(1), 237-254. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9020.2007.00006.x [ Links ]

Hunter, M. (2013). The consequences of colorism. In R. E. Hall (Ed.), The melanin millennium: Skin color as 21st century international discourse (pp. 247-256). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4608-4_16

Johnson, J., Bienenstock, E., & Stoloff, J. (1995). An empirical test of the cultural capital hypothesis. The Review of Black Political Economy, 23, 7-27. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02689909 [ Links ]

Kanja, K. (2020, December 16). Kenyans increasingly acknowledging the existence of skin tone discrimination. The Standard, https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/entertainment/news/article/2001397443/kenyans-increasingly-acknowledging-the-existence-of-skin-tone-discrimination

Keith, V. M., & Monroe, C. R. (2016). Histories of colorism and implications for education. Theory Into Practice, 55(1), 4-10. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2016.1116847 [ Links ]

Kemp, S. (2022). Digital2022: Kenya. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-kenya

Kiarie, C. (2020). Social networking sites and interpersonal communication: A mixed methods study on employees at the workplace in Kenya [PhD thesis.] University of Kwa-Zulu- Natal (UKZN), Durban. [ Links ]

Kinuthia, K. M., Susanti, E., & Kokonya, S. P. (2023). Afrocentric beauty: The proliferation of "texturist" and "colorist" beliefs among young women in Kenya. Masyarakat, Kebudayaan & Politik, 36(1). https://doi.org/10.20473/mkp.V36I12023.32-43 [ Links ]

Lewis, K. M., Robkin, N., Gaska, K., & Njoki, L. C. (2011). Investigating motivations for women's skin bleaching in Tanzania. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 35(1), 29-37. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684310392356 [ Links ]

Maddox, K., & Gray, S. (2002). Cognitive representations of Black Americans: Reexploring the role of skin tone. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(2), 250-259. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167202282010 [ Links ]

Mathews, T. J., & Johnson, G. S. (2015). Skin complexion in the twenty-first century: The impact of colorism on African American women. Race, Gender & Class, 22(1-2), 248-274. [ Links ]

Mishra, N. (2015). India and colorism: The finer nuances. Washington University Global Studies Law Review, 14(4), 725-750. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/lawglobalstudies/vol14/iss4/14 [ Links ]

Monroe, C. (Ed.). (2016). Race and colorism in education. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315746227

Norwood, K. J. (2015). If you is White, you's alright: Stories about colorism in America. Washington University Global Studies Law Review, 14(4), 585-607. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/lawglobalstudies/vol14/iss4/8 [ Links ]

Obino, V. (2021, May 17). Colour culture through the Kenyan eye. Andariya. https://www.andariya.com/post/colour-culture-through-the-kenyan-eye

Okango, J. K. (2017). "Fair and lovely": The concept of skin bleaching and body image politics in Kenya. Master's thesis, Graduate College of Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, Ohio. https://etd.ohiolink.edu/acprod/odbetd/ws/send file/send?accession=bgsu1496345994175129&disposition=inline [ Links ]

Ongaji, P. (2019, November 28). We need to talk about colourism. Nation. https://nation.africa/kenya/life-and-style/ongaji-we-need-to-talk-about-colourism-227196

Parker, S. (2021). What does it mean to be Black-ish?A grounded theory exploration of colorism on Twitter. Master's thesis, University of Oklahoma, Norman. https://shareok.org/handle/11244/330247 [ Links ]

Price, V., & Tewksbury, D. (1997). News values and public opinion: A theoretical account of media priming and framing. In G. A. Barnett, & F. J. Boster (Eds.), Progress in communication sciences, vol. 13. (pp. 173-212). Ablex.

Rosario, R. J., Minor, I., & Rogers, L. O. (2021). "Oh, you're pretty for a dark-skinned girl": Black adolescent girls' identities and resistance to colorism. Journal of Adolescent Research, 36(5), 501-534. https://doi.org/10.1177/07435584211028218 [ Links ]

Simiyu, M. (2023, September 3). TikTok trend: Kenyans condemn colourism, share traumatic experiences of dark-skinned women. Nairobi News. https://nairobinews.nation.africa/tiktok-trend-kenyans-condemn-colourism-share-traumatic-experiences-of-dark-skinned-women/

Telles, E. E., & Ortiz, V. (2008). Generations of exclusion: Mexican Americans, assimilation, and race. Russell Sage Foundation.

Tekie, F. (2020). Colorism in Zanzibar: A qualitative field study on the effects of colorism on women's identity and ethnicity construction. Master's thesis, Malmö University, Sweden. https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:mau:diva-22911 [ Links ]

Tewksbury, D. H., & Scheufele, D. A. (2019). News framing theory and research. In Media effects (4th ed.). (pp. 51-68). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429491146-4

Thompson, M. S., & Keith, V. M. (2001). The blacker the berry: Gender, skin tone, self-esteem, and self-efficacy. Gender and Society, 15(3), 336-357. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124301015003002 [ Links ]

Tuchman, G. (1978). Making news: A study in the construction of reality. Free Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/2578016

Van Hout, M. C., & Wazaify, M. (2021). Parallel discourses: Leveraging the Black Lives Matter movement to fight colorism and skin bleaching practices. Public Health, 192, 1-2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2020.12.020 [ Links ]

Walker, A. (1983). If the present looks like the past, what does the future look like? In In search of our mothers' gardens: Womanist prose. Harcourt. http://l-adam-mekler.com/walker_in_search.pdf

Wasike, B. S. (2013). Framing news in 140 characters: How social media editors frame the news and interact with audiences via Twitter. Global Media Journal: Canadian Edition, 6(1), 5-23. http://gmj-canadianedition.ca//wp-content/uploads/2018/11/v6i1wasike.pdf [ Links ]

Wickett A. (2021). Not so Black and white: An algorithmic approach to detecting colorism in criminal sentencing.In COMPASS (p.46). https://doi.org/10.1145/3460112.3471942

Williamson, J. (1995). New people: Miscegenation and mulattoes in the United States. Louisiana State University Press.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge with gratitude Kenyan data scientist Jacktone Momanyi's work on this study's data mining and analysis, and the funding support provided by the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN) and South Africa's National Institute for the Humanities and Social Sciences.