Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.37 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2023/n37a36

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Give the Black Girl the Remote: De-colonising and Depatriarchalising Knowledge and Art in Black Panther and Colour Me Melanin

Deirdre C. Byrne

University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa. byrnedc@unisa.ac.za (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4436-6632)

ABSTRACT

This article explores two texts set in Africa to determine to what extent they exhibit decolonial and anti-patriarchal impulses. They are Ryan Coogler's 2018 film, Black Panther, and the adult colouring book, Colour Me Melanin (Kekana 2019), which features 27 portraits of African women paired with 27 poems inspiring pride in women's African heritage. Black Panther features a Black superhero: the hypermasculine T'Challa, although its technological genius is not T'Challa (the eponymous Black Panther), but his sister Shuri, disparaged by traditionalists in Wakanda as 'a child'. Despite her irreverent and iconoclastic approach to tradition, sixteen-year-old Shuri is 'the smartest person in the world, smarter than Tony Stark [Iron Man]' (Malik 2023). Despite these promising features, the film's portrayal of Shuri - a Black girl nerd who is manifestly her brother's equal in the arts of war and technology - stops short of a complete depatriarchalisation of the norm that reserves superhero status for men. Further, Black Panther contains a number of concerning representations that reinforce, rather than disrupting, the colonial view of Africa. Colour Me Melanin may be called speculative fiction in that it points to a future that is yet to come as it shifts the locus of women's beauty away from whiteness and places it firmly in the domain of Black African women's embodiment. All the same, some aspects of this multimodal text signal its affinity for colonial taxonomies and ways of thinking about ethnicity.

Keywords: Black Panther, Colour Me Melanin, decolonising, depatriarchalising, Wakanda, tribalism.

Introduction

Coloniality and patriarchy are intersecting, mutually reinforcing systems of oppression. Although this may seem obvious, it is less widely acknowledged than decolonial feminists would like. Patriarchy ensures that men call the shots and make the decisions, while coloniality privileges commercial, educational, religious, political and intersubjective structures that legitimate White, Western and Northern2 power. These two systems, which intersect with global capitalism and its neoliberal iteration, oppress social groups in ways that are both structural and personal (Vicente 2022). As postcolonial theorists such as Ashcroft, Griffin and Tiffin (2006); Memmi (1974) and Fanon (1986) have shown, colonial conditions linger for extended periods after a colonised territory gains independence. The postcolonial turn in the latter part of the twentieth century addressed the lingering effects of colonialism on nations and communities across the globe. Decolonial theory, however, has taken the debate further, into an analysis of (colonial) modernity as a totalising regime that infiltrated and shaped all aspects of personal and social existence. As a world order, coloniality3subjugated - and continues to subjugate - indigenous peoples:

Once the colonial matrix of power is no longer managed and controlled by the so-called West, it impinges on and transforms all areas of life, particularly with regard to two interrelated spheres: (a) the coloniality of political, economic, and military power (interstate relations), and (b) the coloniality of the three pillars of being in the world: racism, sexism, and the naturalization of life and the permanent regeneration of the living (e.g., the invention of the concept of nature). (Mignolo & Walsh 2018:10, original emphasis)

Coloniality's pervasiveness as a system of control and domination must be kept in mind in any decolonial analysis or endeavour. In this article, my focus is on how coloniality affects 'the three pillars of being in the world: racism, sexism, and the naturalization of life and the permanent regeneration of the living' (Mignolo & Walsh 2018:10).

Patriarchy, driven by sexism, is ubiquitous and powerful, despite global feminist efforts to dethrone, undermine and undo it. Decolonial feminist Maria Lugones (2008:12) understands coloniality and patriarchy as mutually constitutive: 'the imposition of this gender system [by colonisers] was as constitutive of the coloniality of power as the coloniality of power was constitutive of it'. Undoing sexism is not always seen as a decolonial act, although, in Lugones's terms, it should be perceived as such. I wish to re-emphasise the co-imbrication of depatriarchalisation and decoloniality here through a decolonial feminist analysis of two speculative fiction texts in popular culture: Ryan Coogler's Black Panther (2018) and Katlego Kekana's Colour Me Melanin (2019). At the outset, though, it is necessary to establish the viability of such an analysis.

There are a range of understandings of decolonisation and decoloniality. Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang (2012:1) argue convincingly that 'decolonization is not a metaphor', but 'brings about the repatriation of Indigenous land and life'. Theirs is an extreme version of the decolonial agenda and does not cover all the acts that are part of decolonising the world, society or knowledge. Most decolonial theorists see knowledge as a key feature of the colonial/modern order; what counts as knowledge, and whose knowledge counts, are important ways of creating and buttressing colonial power. Anibal Quijano (2007:177) offers a more gradual programme for effecting decolonisation than Tuck and Yang:

The alternative, then, is clear: the destruction of the coloniality of world power. First of all, epistemological decolonization, as decoloniality, is needed to clear the way for new intercultural communication [...] as the basis for another rationality [...].

Walter Mignolo (2007:453) agrees that severing epistemic ties with colonial models of thought is crucial: 'delinking [...] leads to de-colonial epistemic shift and brings to the foreground other epistemologies, other principles of knowledge and understanding and, consequently, other economy, other politics, other ethics'. In order to foreground the necessity to undo sexism, I use the neologism 'depatriarchalise' ('to divest of patriarchal attributes', Your Dictionary), which derives from the work of Bolivian anarcha-feminist group Mujeres Creando ('women creating'). Mujeres Creando's Constitution - primarily comprising lists of social institutions and organisations to be dissolved - contains the aphorism:

You cannot decolonize

if you do not depatriarchalize4

(Political, feminist Constitution of the State: The impossible country we build as women; Mujeres Creando [sa]).

'Depatriarchalise' is also the sub-title of one of Mujeres Creando's best-known publications, Feminismo Urgente: A Despatriarcar! (Urgent Feminism: Depatriarchalise!) by Maria Galindo ([sa]).

Decolonising and depatriarchalising contemporary society is an ambitious goal, involving all areas of collective and individual existence. In this process, access to and control of resources is crucial: the world's extractive economies have powered colonial domination for centuries, and Indigenous communities need to take back their control of mineral and financial resources. At the same time, the discourses and images that circulate in society, including in popular culture, play a vital role in constituting and maintaining relations of power. Suely Rolnik (2007:5) has gone as far as to posit an 'imagosphere' which 'today covers the entire planet - a continuous layer of images that places itself as a filter between the world and our eyes'. This layer of images supports and reinforces power-interests, as well as hiding them from the people who are oppressed by the colonial matrix of power. Thus, for example, a predominance of images of white women in clothing advertisements is normalised as 'the way things are' because of the ubiquity of the imagosphere. It is only when one questions the codes and protocols of representation that the inequalities that derive from the colonial matrix of power become obvious. In this article, I scrutinise Black Panther and Colour Me Melanin as works of speculative fiction which have overt decolonial agendas in order to evaluate the extent to which they can be called 'decolonial' or 'decolonising'.

The two texts I discuss in this article - the blockbuster Marvel film Black Panther (Coogler 2018) and Colour Me Melanin, an adult colouring book with pictures accompanying poetry (Kekana 2019) - are definitely part of popular culture. Black Panther grossed more than USD 1.3 billion, making it the highest grossing superhero film of all time (Mohdin 2018). While Colour Me Melanin has a much smaller reach, directed exclusively at Black women in Southern Africa, it taps into the popular trend of adult colouring books, which saw 12 million books being sold worldwide in 2015 (Grady 2017). It is also necessary to establish whether these texts can be called 'speculative'. Black Panther certainly belongs in the speculative fiction genre. Its focus on a superhero (in the form of T'Chaka and his son T'Challa) as the protagonist, pitted against an apparently implacable antagonist (Erik Killmonger), places the narrative squarely outside the realm of realism. In addition, most of the action takes place in a fictional African kingdom: Wakanda. The depiction of Wakanda as one of the richest nations in the world due to its mineral wealth of vibranium extrapolates into the speculative fiction realm from contemporary extractive economies; extrapolation is one of speculative fiction's most well-known tropes (Suvin 1979:76).

It is a stretch, however, to call Colour Me Melanin a text of speculative fiction. The text consists of black and white pictures of African women, accompanied by poems about their various ethnic origins. Unfortunately, the women are assigned to static ethnic categories, which assumes that each woman belongs in only one of these categories and fails to take cultural hybridisation into account. In a 2019 radio interview with DJ Sabby and Tshepi on YFM, Kekana refers to the book's composition as involving women from different 'tribes'. This term has been discredited by anthropologists and Critical Race theorists as serving no purpose beyond belittling and oversimplifying the complexity of ethnic groups in Asia, Africa, North America and Oceania (Wiley 2013). Yet, in its call to African women to colour the images in vibrant shades, Colour Me Melanin is future-oriented and reliant on imagination, aligned with the hope that African women will perceive themselves as possessing rich colours.

Both texts rely heavily on visual images to create portrayals of Black people, especially (for my purposes) Black women. As countless theorists (Nagel 1989; Brown 1993; Hall 1985, 2003: 39) have shown, images encode ideologies, values, judgements, and hierarchies that may buttress socio-political structures of domination. Accordingly, I will introduce each text first, then focus on selected images for close analysis.

Black Panther

Black Panther, based on the Marvel comic series of the same name (1977-2018), was popularly hailed as the first Hollywood film to feature a Black superhero, and much of its box-office success was based on this assumption. However, it is not the first such film: the much less well-known Meteor Man (1993) holds that position, and the second was Blade (released in 1998, Thomas 2020). However, Black Panther's superior box office takings - the highest for any Marvel film - enabled it to change the face of superhero film narratives in terms of racial representation and imagery.

The director's choice to set the action in the fictional African country of Wakanda, and to focus on a Black character as a superhero, ensured that the film shifted the locus of power decisively away from white men and the Global North. Beschara Karam and Mark Kirby-Hirst's editorial for a themed section of Image & Text on Black Panther (2019:9) argues that '[Coogler's] perspective could be argued to be consciously decolonising because of the manner in which white western characters are marginalised, and the technological and scientific achievements of the Wakandans are placed front and centre'. This is an example of the film's anti-racist and antiWestern characterisation and setting. However, as Mignolo (1994:505 and passim) demonstrates, the 'locus of enunciation' is a more complex matter. Enunciation is imbricated in a network of meanings:

there is a linguistic story to be recalled here about [.] the fact that enunciating is always enunciating from within (or without) an institutional site that legitimizes speaking or writing, or against which speaking or writing is enacted (Foucault), and that enunciating is always dialogic, entrenched in previous discourses and in an established system of genres. (Mignolo 1994:507)

Enunciation, in Black Panther, is mostly done by Black people such as King T'Chaka, King T'Challa, Erik Killmonger, and Chief M'Baku. But they tend to speak from within a discourse that exoticises and primitivises Africa, as seen in their largely ceremonial and often impractical clothing and the exotic locations of much of the action. Further, the film's central political debate - whether to share Wakanda's vibranium with the rest of the African diaspora or not - focuses on an extractivist model of political economy. Thus, while giving Black African speakers the metaphoric microphone is a step in the direction of decolonising the superhero genre, it does not change the content of the discussion.

Wakanda exists in an imagined pre-colonial African past, which has been maintained, unspoilt by colonialism, by a powerful force-field. This makes the nation appear to be one of the poorest in the world by hiding its technoscientific achievements. Rosemary Chikafa-Chipiro (2019:71) correctly identifies the film's decolonising strategy in its depiction of an African past as a repository of scientific knowledge:

Black Panther is arguably a postcolonial, Afrocentric and de-colonial [sic] reinstitution of a pre-colonial African past undertaken by means of traversing a ubiquitous African colonial past and through a de-colonial African present.

Chikafa-Chipiro and Karam and Kirby-Hirst's praise for Black Panther relies on their assessment of Coogler's effective 'delinking' (Mignolo 2007:449) from Eurocentric views that centre and promote white masculinity, reserving heroic (and superheroic) roles for white men. Walter Mignolo offers several definitions of delinking in his 2007 article of the same name. A relevant definition is: 'Delinking means to change the terms and not just the content of the conversation' (Mignolo 2007:449, emphasis added). So, when decolonising superhero narratives, the very term 'hero' needs to be changed, which Black Panther achieves, to a certain extent, by changing the race of those who qualify to be heroes and superheroes. Nevertheless, the model of hyperathletic masculinity, which is found in numerous superhero narratives,5 is retained unchanged.

More seriously, though, several reviews have criticised the film on the grounds that it reproduces Euro-American stereotypes of Africa. Paul Tiyambe Zeleza (2018) complains, with considerable justification, that the film homogenises Africa by presenting it as having a single cultural expression:

The bodies of several of the characters are duly adorned with the 'tribal markings' of National Geographic among 'native peoples' in remote corners of the globe; one even spots [sic] an elongated mouth disk! Equally disconcerting are the fake accents, the poor attention paid to African languages, all of which produces a dangerously simplistic and [sic] homogenization of the continent.

The justice of Zeleza's complaint is manifest in the scenes where T'Challa defends his claim to the Wakandan throne.

In these scenes, African culture is oversimplified, with ethnic dress and body decorations presented through a Western gaze, as exotic, primitive and outdated, as seen in Figure 1.

Patrick Gathara (2018) is more scathing than Zeleza in his review for The Washington Post:

At heart, it is a movie about a divided, tribalized continent, discovered by a white man who wants nothing more than to take its mineral resources, a continent run by a wealthy, power-hungry, feuding and feudalist elite, where a nation with the most advanced tech and weapons in the world nonetheless has no thinkers to develop systems of transitioning rulership that do not involve lethal combat or coup d'etat (sic).

Jonas Slaats (2018) is similarly condemnatory, arguing that the film is a 'a nationalist, xenophobic, colonial and racist movie' on the grounds that, under the pretext of subverting Euro-American norms of representing Africa, it reinscribes and reinforces those norms. Some of Slaats's (2018) criticisms can be read in a different way than he might have meant: for example, the claim that 'All black protagonists are morally ambivalent' can also be interpreted as Coogler's depicting Black characters as psychologically and morally rounded. However, his central argument, that Black Panther depicts a neocolonial view of Africa, is difficult to refute.

T'Challa (played by the late Chadwick Boseman) is the obvious viewpoint character and heroic protagonist of Black Panther. T'Challa, in keeping with the Western and Northern myth of the hero as hypermasculine, is an impressively manly figure with large muscles and radiant health (an ironic depiction considering Boseman's death in 2020 from colon cancer). Heroism in Western and Northern culture, including popular culture, has always been male, as Ursula K. Le Guin notes (1993:2). A typical hero is a man, of humble birth, but possessing superior intellect and/or athletic prowess, who is destined to play a more-than-human role.6 T'Challa is the heir to the throne of Wakanda and the mantle of the Black Panther, which gives him superhuman abilities. Wakanda can only be ruled by a king; it would be unthinkable for Queen Ramonda (Angela Bassett) to ascend to the throne. The heir's ascension to the throne is sealed by a show of masculine athletic prowess, in which any challenger may duel with the incumbent and the strongest man wins. The duel takes place in a pool of water in a mountainous area and is conducted with fatal weapons. While this creates a picturesque spectacle, it reduces the criterion for the new king's ascension to the throne to a display of testosterone, undermining Wakanda's cognitive and scientific accomplishments as an important source of scientific knowledge production.

T'Challa is introduced to the viewer on a mission to a Kenyan forest to retrieve the girlfriend of his teenage years, Nakia (Lupita N'yongo), so she can attend his coronation the next day. This implies that the future king needs a (heterosexual) consort, whom Le Guin (1993:11) describes as 'a pro-forma bride', who will not become the reigning monarch. Despite some heavy flirting, Nakia does not marry T'Challa: she follows her own agenda instead. In this, she breaks away from the superhero formula that dictates that the superhero can have any woman he chooses and depatriarchalises the genre in a minor way.

Shuri (Letitia Wright), however, steals the show. As Wakanda's main designing scientist, she controls the country's vast mineral resource of vibranium, an extremely powerful substance that can be used for anything from weapons to textiles and even as fuel. Ascribing Wakanda's wealth to its possession of vibranium is an ambivalent move in the politics of representation. On the one hand, as Nakia and Erik Killmonger repeatedly assert, and as is seen in the film's closing scenes, the country has the power and scientific knowledge to help to all members of the African diaspora. Locating this capability in an African country significantly subverts colonial stereotypes that perceive Africa as materially and epistemologically impoverished. On the other hand, though, the fact that Wakanda's wealth lies in its minerals unfortunately, and rather ham-handedly, perpetuates extractivism as the film's primary economic model.

Shuri's technological and scientific genius allow her to break away from a cultural stereotype that has dominated speculative fiction for centuries: the notion that women cannot be scientists in their own right, but are limited to roles as men's helpers in the pursuit of scientific knowledge. This notion is fuelled by patriarchal ideas that women, who, stereotypically, are 'more emotional' than men, cannot possess the required intelligence for scientific innovation.7 It has found its way into numerous texts in popular culture, such as the early years of the Star Trek television series, where the main protagonists and decision-makers were always male scientists.8 The patriarchal prejudice against male scientists in fiction can be traced back to Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus (1818), famously hailed by Brian Aldiss in Trillion Year Spree as the first science fiction novel (1973:21). Frankenstein enjoys this position primarily because of the novel's allusion to the (then) cutting-edge theory of 'galvanism', which held that one could animate inanimate objects, including corpses, with electricity. While the mistaken scientist, Victor Frankenstein, occupies himself with assembling a human body from dismembered corpses and then animates the resulting cadaver with electricity, the sexism running through his scientific discourse does not escape the reader's attention: 'The modern masters [of science] ... penetrate into the recesses of nature, and show how she works in her hiding places' (Shelley 1930:40, emphasis added). This discourse is similar to Carolyn Merchant's argument in her now-classic The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology and the Scientific Revolution (1980:171), which outlines

the key feature of the modern experimental method - constraint of nature in the laboratory, dissection by hand and mind, and the penetration of hidden secrets - language still used today in praising a scientist's 'hard facts,' 'penetrating mind,' or 'the thrust of his argument'.

The central impulse of Frankenstein (Mellor 1988; Moers 1978; Byrne 1993) is to exclude women from the process of reproduction, claiming it as a male prerogative. When the monster wishes for a female mate, the scientist refuses, tormented by thoughts of a race of murderous, destructive monsters sprung from their union. Victor Frankenstein's monstrous 'child' cements and perpetuates a habit of excluding women from scientific discourse and competency. Mary Shelley's text occupies a central position in the canon of Western speculative fiction, where, with the exception of Octavia Butler's work, women scientists were very scarce and Black women scientists were completely excluded.

Shuri not only decolonises the Western epistemic tradition of white male scientists labouring alone in laboratories with only their scientific genius for company: she depatriarchalises it as well. Shuri is Wakanda's chief scientist, 'a position she cherishes much more than her royal status' (Shuri [sa]). Her often sassy relationship with the rest of the characters indicates that the princess is as skilled at repartee as she is at science and technology. Shuri is reprimanded for her unceremonial levity at T'Challa's ritual challenge for the throne, when she famously asks, 'This corset is really uncomfortable, so could we just wrap it up and go home?' (Marvel Cinematic Universe Fandom Wiki). Nevertheless, she demonstrates her loyalty to the Wakandan and African philosophy of Ubuntu, which is dominated by the African value of communalism: 'Communalism insists that the good of all determines the good of each or, put differently, the welfare of each is determined by the welfare of all' (Kamwangamalu 1999:27). Discussing whether Ubuntu/communalism is unique to Africa, Kamwangamalu (1999:36) notes pertinently that, 'Ubuntu is indeed unique to Africa, where the Bantu languages from which it derives are spoken. However, the values it evokes seem to be universal'. Shuri's exemplifying Ubuntu is another example of the film decolonising received values.

Shuri's scientific brilliance can be read in two ways. She may be seen as another extraordinary woman who is prevented by authorial patriarchal prejudice from rising further than the role of sidekick to a man, as women have been in heroic speculative fiction for decades. Or her genius may be seen as demonstrating her loyalty to Wakanda, the country she loves and serves. Shuri is, therefore, less independent than Nakia, despite her witty repartee. She is also, manifestly, fond of scientific invention. When she manages, - through her own efforts - to drive a car remotely, her delight is infectious.

While Shuri's superior intellect and technoscientific skills depatriarchalise the speculative fiction genre, her relegation to a secondary role contradicts this progressive move towards gender-equal representation. This unfortunately conveys the message that masculine athletic prowess and aggression, which T'Challa possesses, are superior to scientific brilliance, a message that is reinforced by the depiction of General Okoye (Danai Gurira), whose dominance and prowess in war enable her to best her own husband and force him back to loyalty to T'Challa. The Marvel comics recognise Shuri's scientific and technological genius by giving her her own comic series, titled Shuri (2018-2019), where she becomes the Black Panther and even the Queen of Wakanda. Nevertheless, as things stand in the Black Panther film, although a gesture towards depatriarchalising has been made, it is not enough definitively to counter the pervasive representation of women in speculative fiction as sidekicks to the 'real' heroes, who are men. In a similar way, although the film counters racism in its foregrounding of Black heroes, it also unfortunately reinforces many of the economic and discursive pillars of colonialism.

Colour Me Melanin

The adult colouring book, Colour Me Melanin (Kekana 2019), offers a different perspective on decolonisation and depatriarchalisation. The artist, Katlego Kekana, calls herself 'The Colourist', a pun on her skin colour as well as the activity of colouring in. The book contains 27 black and white line drawings of women from many African 'tribes' (Zulu, Ndebele, Sotho, Swati, isiXhosa, Khoisan, Pedi, Tswana, Venda, Tsonga, Haya, Himba, Maasai, Mursi, Ngoni, Shona, Kikuya, Swahili, Wodaabe, Afar, Borana, Fulani, Kisongo, Mangbetu, Pokot, Suri, and Tigrai). The first letter of the tribe's name is illuminated in black and white, in a way that recalls the illumination of medieval manuscripts, emphasising its illustrious history. Each drawing is accompanied by a 'synopsis' of facts about the tribe and an original poem by an African poet. The book aims to encourage readers to colour in the drawings, using colours that authentically represent African women's skin tones, and to be inspired by the poetry (Figure 2). In this way, although the book does not strictly belong in the genre of speculative fiction, it gestures towards a future yet to be realised, in which Black women can enjoy their own beauty and lineages.

Colouring in, although often perceived as a children's activity, is a multimodal, embodied practice, using the body and mind to create an affective and affecting artwork. Colour Me Melanin aims to raise Black women's awareness of the multiple and nuanced ways in which embodiment is both social and political. Colouring in the images requires subtle toning, breaking away from the binary logic of coloniality that places Black people as the discarded second term in an oppressive dichotomy. The colours that readers would probably use to colour in the images might belong to shades of brown: ochre, umber, mahogany, beige, buff, chocolate, coffee, cappuccino, tan, burnt sienna and others, as shown in the image on the cover. Colouring in reinforces what Rosemary Chikafa-Chipiro (2019a:9) calls 'Africana (melanated) womanism'. Chikafa-Chipiro confirms that this is 'a recent reconceptualisation of Clenora Hudson-Weems's concept of Africana Womanism' (Chikafa-Chipiro 2019a:9), with the modifier 'melanated' emphasising how melanin unites women of African descent across the globe. Nadia Sanger (2009:144) points out, referring to biological research, that melanin in skin cells protects the skin from ageing and from sun damage, so that melanated women can enjoy their skins in better condition for longer than those who do not possess melanin. Sanger rightly reverses the binary opposition between white and non-white skins (Gammage 2016:2), valorising Black women's skin colour as a source of health and vitality.

The opening pages of the volume contain Kekana's (2019) request 'that these poems are read out loud'. This request is multi-layered: it draws on the oral tradition of poetry in Africa, and it also evokes the sonic, aural, rhythmic and gestural multimodal affordances of reading poetry aloud. By requesting the reader to read the poetry out loud, Kekana appeals to them to participate in the Indigenous lineage of African women's cultural pride, which is historically rooted in the oral praise poetry tradition. This may be seen, for example, in Yamoria's9 poem for the 'Khoisan' woman:

Krotoa rises from the sun kissed soil, And mouths chant parables into the desserts [sic]!

Masters of linguistics! Our tongues click and fold mysteries!

Herb Gathers [sic]! We collaborate with nature to whisper healing, Upon rigid rocks we are art dancing!

Conquerers [sic]! IIN^au!a ta g era the land Disciples of Sand!

We are the Alpha people! We are the Khoisan!

(Kekana 2019)

The poem's inclusion of Khoisan words in line 9 decolonises the hierarchy of linguistic representation in which English has held sway in South Africa, as in all former British colonies, as the sole acceptable means of literary communication. The phrase 'We are the Alpha people!' in the final stanza alludes to the fact that the Khoisan are South Africa's first indigenous inhabitants. 'Alpha' invokes the first letter of the Greek alphabet. This is used in the Christian Bible, which was brought to South Africa by colonising missionaries, and describes God as 'the Alpha and Omega' or beginning and end. It also - possibly closer to Yamoria's intentions - evokes the leadership of a group, as in 'the Alpha male'. The poets' choice to draw on Western and Northern culture to assert the Khoisan's primacy may be read as a trace of colonial culture, or as evidence of Indigenous peoples' assimilating the Western cultures that were imposed on them. Either way, it is a vestige of colonial enunciation.

'Krotoa' alludes to the Griqua slave woman who was taken into Jan van Riebeeck's house a few days after the Dutch arrival at the Cape of Good Hope in 1652 and served as a translator between the Griquas, the Dutch and the Portuguese. Krotoa died on Robben Island in her early thirties after terrible suffering and mistrust (South African History Online [sa]); but she was a '[master] of linguistics' who, in the twenty-first century, would have been recognised and fêted as a genius. Her spirit and memory inspire, not only the poet/s, but also contemporary Khoisan women.

Oral praise poetry's habit of invoking ancestors to provide inspiration for the present is found in Katleho Kano Shoro's poem for the Sotho woman:

I gather straws of our scattered stories.

Weave tranquillity into an epic of MaNthatisi

herding armies of wild cats

through victories in far lands.

The healing of Mantsopa: my intertwist,

She remedied war with rain,

So I criss-cross water into our tale.

I intwine myself as the brave Tselane,

Plait pluck into our plot,

Draw out luck and abundance for the final knot.

I am the weaver of peace: Khotso

I am the offspring of rain: Pula

I am abundance: Nala

I am MoSotho! (Kekana 2019, n.p.)

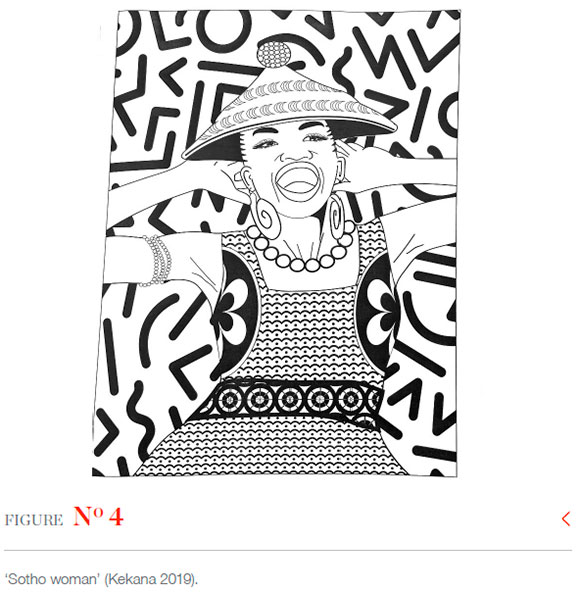

Shoro's allusion to 'gathering straws of our scattered stories' evokes a tapestry of stories, scattered across the African continent because of colonialism and a long history of migration, which she poetically re-ties into a 'knot' of strength and beauty. The mention of famous Sotho women, MaNthatisi, Mantsopa and Tselane, conjures courage, a powerful bond with nature and finally 'luck and abundance'. These three foremothers kindle pride in the audience at their distinguished lineage. The image accompanying this poem shows a woman with her hands cupped over her ears and her mouth stretched wide: a clear allusion to the centrality of voice, both in spoken word poetry and in women's reclamation of public utterance (Figure 4).

The combination of appealing to distinguished ancestors and natural forces along with powerful images of women in striking poses makes a number of points about African women. Much popular culture has presented white women's bodies as beautiful, to the exclusion of Black women, who have been visually erased and silenced in what we might call the coloniality of the image. Marquita Marie Gammage's Representations of Black Women in the Media: The Damnation of Black Womanhood (2016:1; 5-7) explains how popular discourse, including media representation, has trapped Black women in a catch-22 situation where their stereotyping as hypersexual does not allow them to be portrayed with dignity even in such patriarchally conditioned roles as wife and mother. The 'purposeful condemning of Black womanliness as inferior, inhumane, and ungodly' (Gammage 2016:5) has damaged black women's self-concept. Considering this, it is important for them to adopt new, decolonial fashion practices as a way of decolonising their own expectations of bodily aesthetic. Nthabiseng Motsemme's article, 'Distinguishing Beauty, Creating Distinctions: The Politics and Poetics of Dress among Young Black Women' (2003:14), finds that the adoption of what she calls an 'Afro-femme' sartorial aesthetic offers a substantial challenge to colonial images of beauty:

Growing up in a country where beauty has been, and continues to be, violently raced or articulated through the medium of skin colour and hair texture, the privileging of darker skin tones dressed in these new Afro-femme designs constitutes ... an important disruption to what were conventional forms of beauty and femininity.

The invidious conjunction of violence with ideals of feminine beauty was seen in the furore in 2016 around the hairstyles of Black learners at Pretoria Girls' High School (Pather 2016), who were required by the school to conform to European hairstyles. This was only one incident where Black women have been expected to conform to white standards of beauty. A preoccupation with the politics of hairstyles, as Motsemme (2003:14) notes, is not simply 'a demonstration of vanity and superficiality by women', but a profoundly political matter. For Black women to wear 'natural (unstraightened) hair' is an act of defiance against media images of feminine beauty that decree that only straight, silky (white) hair is (hetero)sexually attractive (Sanger 2009:142-144). Demanding that black women straighten their hair and lighten their skin in order to conform to white standards of beauty is an act of discursive colonial violence, which Colour Me Melanin seeks to undo.

The diversity of ethnic and tribal groups mentioned in Colour Me Melanin avoids the trap of homogenising African culture or African people in the way Black Panther arguably does. In decolonising images of African people, it is important to combat and undo the suggestion that Africa is unitary: as Stuart Hall reminds us, 'all identity is constructed across difference' (in hooks 1995:11). Colour Me Melanin's invitation to the reader to write her name in the book, and then to colour in the images, for example by using the vibrant tones of the cover illustration, invite African women to understand themselves as possessing nuance, diversity and beauty. At the same time, the book's insistence on Black women as belonging to 'tribes' primitivises ethnicity in Africa. The word 'tribe' was used by colonial ethnologists who regarded Indigenous people as primitive and undeveloped. Many theorists now consider it outdated (Mamdani 2012; Sneath 2016), so it is unusual to find it being used in a text such as Colour Me Melanin, written by Black women for Black women. Its appearance here can only be attributed to the extraordinary longevity of colonial paradigms for thinking about ethnicity.

Conclusion

My article has drawn out the decolonising and depatriarchalising threads that connect Black Panther and Colour Me Melanin to theoretical work on anti-racism, decoloniality and anti-sexism. The 2018 Marvel blockbuster film, Black Panther, presents not only one, but two black superheroes: T'Challa, King of Wakanda, and his sister, the scientific and technological genius, Shuri. Black Panther centres African achievements in the fields of industry, science and technology, and in this way breaks with colonial narratives about the 'primitiveness' of African culture and epistemology. Nevertheless, the film has been justly criticised for reproducing Western and neoliberal ideas of Africa. The abiding imprint of these ideas is seen in its dependence on extractivist economic models (Wakanda is a mining economy, and the main conflict that drives the plot concerns mineral resources) and in images of African culture. The scenes depicting the challenges for the throne take place against a waterfall, with members of all the Wakandan tribes watching. The unfortunate impression is created that all the diverse African cultures are part of the same nation. This is reinforced in the scenes featuring W'Kabi (General Okoye's husband), who is always shown tending a herd of cattle, while his wife is clearly technologically skilled and an accomplished warrior. The depiction of W'Kabi as a bucolic shepherd ties into stereotypes of Africans as pastoral and technologically primitive and is demeaning, given his standing as the Head of Security for Wakanda's Border Tribe (Marvel 2021). A more serious concern about Black Panther is, however, its gender hierarchy. Despite the film's executive producer, Nate Moore, saying that Shuri is 'the smartest person in the world', who possesses 'genius level intellect and incredible engineering skills' (Marvel Cinematic Universe Fandom Wiki [sa]), she plays, in the final analysis, only a supporting role for her brother. So despite the film's depatriarchalising the tradition of women as scientists, her portrayal remains within patriarchal confines.

Colour Me Melanin, a South African adult colouring book, gestures towards a future in similar, albeit less explicit, ways to Black Panther. The future it invokes, and attempts to bring into being, is one where Black African women can celebrate their own beauty without comparing it to white Western standards. While this is laudable, the book's assigning women to tribes belittles rather than appreciating their ethnic diversity. The two texts belong to completely different genres and appeal to widely divergent audiences. Nevertheless, they bear witness to decolonising and depatriarchalising impulses in contemporary popular culture and contribute to this shift, even as they highlight the work that remains to be done to bring about epistemological and representational transformation.

Notes

1 The neologism 'depatriarchalise' is taken from Bolivian anarcha-feminist group, Mujeres Creando (women creating), one of whose publications is entitled Feminismo Urgente - A Despatriarcar! (Urgent Feminism - Depatriarchalise!) (Mujeres Creando 2020).

2 There are no fully adequate terms for the part of the world that colonised and continues to oppress the other. 'The Global North' is not geographically accurate, and neither is 'the First World' or 'the developed world'. In this article I settle for 'Western and Northern powers' because it seems the least problematic of numerous unsatisfactory terms.

3 This term was originally introduced by Anibal Quijano (2007:171): 'Coloniality of power was conceived together with America and Western Europe, and with the social category of "race" as the key element of social classification of colonized and colonizers'.

4 The English version of the Constitution uses -ize, in accordance with the US spelling preferred by Mujeres Creando, and I have followed the group's use here.

5 For example: Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (Persichetti, Ramsey & Rothman 2018); The Dark Knight (Nolan 2008); Superman: The Movie (Donner 1978); and Marvel's The Avengers (Whedon 2012).

6 Joseph Campbell (2021:23) writes in The Hero with a Thousand Faces that 'The hero has died as a modern man; but as eternal man - perfected, unspecific, universal man -he has been reborn'.

7 An example of these stereotypes is the mathematician Ada Lovelace, Lord Byron's natural daughter, who worked with the inventor Charles Babbage and has been called 'the first computer programmer' (Computer History Museum 2021). Lovelace was not credited with programming the computer until after her death.

8 Star Trek Voyager introduced Kathryn Janeway, the first female captain of the USS Enterprise. It ran from 1995-2001.

9 Yamoria is the pen name of sibling duo, Fumane and Mfumo Ntlhabane.

References

Aldiss, B. 1973. Billion Year Spree: The True History of Science Fiction. Garden City NY: Doubleday. [ Links ]

Ashcroft, B, Griffiths, G & Tiffin, H (eds). 2006. The Post-Colonial Studies Reader. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Best Drive. 2019. The best drive coloured in a 'Colour Me Melanin' colouring book. YFM. [O]. Available: https://www.yfm.co.za/2019/11/20/the-best-drive-coloured-in-a-colour-me-melanin-book-for-universal-childrens-day/. Accessed 26 June 2022. [ Links ]

Brown, RH. 1993. Cultural representation and ideological domination. Social Forces 71(3):657-676. [ Links ]

Byrne, D. 1993. The Meaning(s) of Frankenstein. Journal of Literary Studies 9(2):170-184. [ Links ]

Campbell, J. 2010 (1949). The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Fontana. Epub. [ Links ]

Chikafa-Chipiro, R. 2019. The future of the past: Imag(in)ing black womanhood, Africana Womanism and Afrofuturism in Black Panther. Image & Text 33:68-88. [ Links ]

Chikafa-Chipiro, R. 2019a. Racialisation and imagined publics in Southern Feminisms' solidarities. Agenda: Empowering Women for Gender Equity 33(3):8-18. [ Links ]

Computer History Museum. 2024. Ada Lovelace. [O]. Available: https://www.computerhistory.org/babbage/adalovelace/. Accessed 1 February 2024. [ Links ]

Coogler, R (dir.) 2018. Black Panther. Marvel Studios. [ Links ]

Depatriarchalize Definition. [sa]. Your Dictionary. [O]. Available: https://www.yourdictionary.com/depatriarchalize. Accessed 30 May 2022. [ Links ]

Fanon, F. 1986. Black Skin, White Masks, translated by CL Markmann. London: Pluto. [ Links ]

Gammage, MM. 2016. The Representation of Black Women in the Media: The Damnation of Black Womanhood. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Gathara, P. 2018. 'Black Panther' offers a regressive, neocolonial vision of Africa. The Washington Post. [O]. Available: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/global-opinions/wp/2018/02/26/black-panther-offers-a-regressive-neocolonial-vision-of-africa/?variant=95d42e19c24b03e7. Accessed 26 June 2022. [ Links ]

Gill, R. 2008. Empowerment/sexism: figuring female sexual agency in contemporary advertising. Feminism & Psychology 18(1):35-59. [ Links ]

Grady, C. 2017. The coloring book trend is dead. Happy National Coloring Book Day!' Vox. [O]. https://www.vox.com/culture/2017/8/2/16084162/coloring-book-trend-dead-happy-national-coloring-book-day. Accessed 2 September 2022. [ Links ]

Grosfoguel, R. 2006. World-systems analysis in the context of transmodernity, border thinking, and global coloniality. Review (Fernand Braudel Center) 29(2):167-187. [ Links ]

Hall, S. 1985. Signification, representation, ideology: Althusser and the post-structuralist debates. Critical Studies in Mass Communication 2(2):91-114. [ Links ]

Hall, S (ed.). 2003 (1997). Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices. London: SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

hooks, b. 1995. Art on my Mind: Visual Politics. New York: The New Press. [ Links ]

Kamwangamalu, NM. 1999. Ubuntu in South Africa: a sociolinguistic approach to a pan-African ideal. Critical Arts 13(2):24-41. [ Links ]

Karam, B & Kirby-Hirst, M. 2019. Guest editorial for themed section Black Panther and afrofuturism: theoretical discourse and review. Image & Text 33:1-15. [ Links ]

Kekana, K. 2019. Colour Me Melanin. Chartwell: Katlego Kekana. [ Links ]

Le Guin, Ursula K. 1993. Earthsea Revisioned. Cambridge: Children's Literature New England. [ Links ]

Malik, E. 2023. When Black Panther producer settled the debate about who's smarter Shuri or Tony Stark & declared Letitia Wright's MCU character the winner! [O]. Available: https://www.koimoi.com/hollywood-news/when-black-panther-producer-settled-the-debate-about-whos-smarter-shuri-or-tony-stark-declared-letitia-wrights-mcu-character-the-winner/. Accessed 25 November 2023. [ Links ]

Mamdani, M. 2012. What is a tribe? [O]. Available: www.ppgcspa.uema.br/Mahmood-Mamdani_What-is-a-tribe. Accessed 16 January 2024. [ Links ]

Marvel Cinematic Universe Wiki. [sa]. Shuri. [O]. Available: https://marvelcinematicuniverse.fandom.com/wiki/Shuri. Accessed 24 January 2021. [ Links ]

Marvel. [sa]. A Dora Born. [O]. Available: https://www.marvel.com/characters/okoye/on-screen. Accessed 24 November 2021. [ Links ]

Mellor, AK. 1988. Mary Shelley: Her Life, Her Fiction, her Monsters. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Memmi, A. 1974. The Colonizer and the Colonized, translated by H Greenfeld. London: Souvenir Press. [ Links ]

Merchant, C. 1980 (1983). The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology, and the Scientific Revolution. New York: Harper & Row. [ Links ]

Mignolo, W. 2007. DELINKING: the rhetoric of modernity, the logic of coloniality and the grammar of de-coloniality. Cultural Studies 21(2):449-514. [ Links ]

Mignolo, W & Walsh, CE. 2018. On Decoloniality: Concepts, Analytics, Praxis. Durham & London: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Moers, E. 1978. Literary Women. Garden City, NY: Anchor Press. [ Links ]

Mohdin, A. 2018. 'Black Panther' is the highest grossing superhero film of all time in the US.' Quartz. [O]. Available: https://qz.com/1237284/black-panther-is-the-highest-grossing-superhero-film-of-all-time-in-the-us/. Accessed 8 August 2021. [ Links ]

Moraes, A, Patrício, M & Roque, T. 2016. 'The homogeneity in feminism bores us: unusual alliances need to be formed': Interview with Maria Galindo. Sur 24(13):225-235. [ Links ]

Motsemme, N. 2003. Distinguishing beauty, creating distinctions: the politics and poetics of dress among young black women. Agenda: Empowering Women for Gender Equity 17(57):12-19. [ Links ]

Mujeres Creando. [sa]. Political, feminist Constitution of the state: the impossible country we build as women. [O]. Available: http://mujerescreando.org/political-feminist-constitution-of-the-state-the-impossible-country-we-build-as-women/. Accessed 8 April 2021. [ Links ]

Nagel, T. 1989. The View from Nowhere. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Pather, R. 2016. Pretoria Girls High School pupil: I was instructed to fix myself as if I was broken. Mail & Guardian. [O]. Available: https://mg.co.za/article/2016-08-29-pretoria-girls-high-school-pupil-i-was-instructed-to-fix-myself-as-if-i-was-broken/. Accessed 13 April 2021. [ Links ]

Quijano, A. 2007. Coloniality and modernity/rationality. Cultural Studies 21(2):168-178. [ Links ]

Rolnik, S. 2007. The body's contagious memory: Lygia Clark's return to the museum. [O]. Available: https://www.kunsthuissyb.nl/images/projecten/archief/2012/On_residency/Body'sContagiousMemory.pdf. Accessed 30 May 2022. [ Links ]

Sanger, N. 2009. New women, old messages? Constructions of femininities, race and hypersexualised bodies in selected South African magazines, 2003-2006. Social Dynamics 35(1):137-148. [ Links ]

Shelley, M. 1930. Frankenstein, Or the Modern Prometheus. London: JM Dent & Sons. Shuri. [sa]. Marvel Unlimited. [O]. Available: https://www.marvel.com/characters/shuri/. Accessed 11 April 2021. [ Links ]

Slaats, J. 2018. 15 reasons why Black Panther is a nationalist, xenophobic, colonial and racist movie. KifKif. [O]. Available: https://kifkif.be/cnt/artikel/15-reasons-why-black-panther-nationalist-xenophobic-colonial-and-racist-movie-6036. Accessed 26 June 2022. [ Links ]

Smith, J. 2022. 'Black Panther: Wakanda Forever' star Letitia Wright slams the Hollywood reporter for equating her vaccine skepticism to some of Hollywood's most notorious child sex abuse scandals. [O]. Available: https://boundingintocomics.com/2022/11/23/black-panther-wakanda-forever-star-letitia-wright-slams-the-hollywood-reporter-for-equating-her-vaccine-skepticism-to-some-of-hollywoods-most-notorious-child-sex-abuse-scandals/. Accessed 16 January 2024. [ Links ]

Sneath, D. 2016. Tribe. The Open Encyclopedia of Anthropology. [O]. Available: https://www.anthroencyclopedia.com/entry/tribe. Accessed 20 September 2022. [ Links ]

South African History Online. [sa]. Krotoa (Eva). [O]. Available: https://www.sahistory.org.za/people/krotoa-eva. Accessed 10 May 2022. [ Links ]

Suvin, D. 1979. Metamorphoses of Science Fiction: On the Poetics and History of a Literary Genre. New Haven: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Thomas, S. 2020. The rise and history of the black superhero: Wakanda forever. Digital Spy. [O]. Available: https://www.digitalspy.com/movies/a34437644/rise-history-black-superhero/#:~:text=Sorry%20Blade%20fans%2C%20but%20before,the%20first%20Black%20superhero%20movie. Accessed 8 April 2021. [ Links ]

Tuck, E & Yang, KW. 2012. Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decoloniality: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1(1):1-40. [ Links ]

Vicente, ANG de A. 2022. Building Feminist Solidarities: The Case Study of Mujeres Creando. [O]. Available: https://hdl.handle.net/10500/30512. Accessed 12 November 2022. [ Links ]

Wiley, D. 2013. Using 'tribe' and 'tribalism' to misunderstand African societies. UPenn. [O]. Available: https://www.africa.upenn.edu/K-1/Tribe-and-tribalism-Wiley2013.pdf. Accessed 26 June 2022. [ Links ]

XX Fashion Diva. 2018. Favorite costumes from Black Panther movie. [O]. Available: https://xxfashiondiva.com/2018/03/06/favourite-costumes-from-black-panther-movie/. Accessed 10 July 2022. [ Links ]

Zeleza, PT. 2018. Black Panther and the persistence of the colonial gaze. USIU-Africa. [O]. Available: https://medium.com/QUSIUAfrica/black-panther-and-the-persistence-of-the-colonial-gaze-6c093fa4156d. Accessed 12 April 2021. [ Links ]