Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.37 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2023/n37a4

ARTICLES

Conceptions of iconicity and their historical reorientations: Pippa Skotnes's horse skeletons and the topos of the Annunciation

Suzanne de Villiers-Human

Deptartment of Art History and Image Studies, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa. humane@ufs.ac.za (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4153-3519)

ABSTRACT

How has art practise historically displayed, enhanced and interrogated its contemporaneous definitions of the nature of images? The focus is on the contemporary South African artist, Pippa Skotnes's horse skeletons, in resonance with a constellation of select Renaissance Annunciation paintings, to highlight the impact of the Eucharist and "real presence" on early modern, modern and post-modern notions of what images have been assumed to be. My comparative interpretation of the diverse works distinguishes their peculiar image functions from systematic and historical perspectives. I show that, with the advent of the most sophisticated type of image, the artistic image, images have been refining their own definitions in performative ways.

I show in my interpretations of these image-aware meta-artworks, that the Incarnation of Christ as the Imago Dei, as well as changing historical understandings of Christ's image act of the institution of the Eucharist, gradually and radically transformed understandings of the nature of images in the west. I furthermore argue that Skotnes's knowledge, through performative research of indigenous Southern African image traditions of the Khoisan/|Xam, contributes lost historical image dimensions to her work, and augments current understandings of images and art, at a time when plenary experiences of time, and historical and cultural density, are appreciated.

For me, Skotnes's work artistically performs Paul Ricoeur's philosophical assumption that continuous and persistent historical reorientations of ancient sacred symbolism of the natural world remain at the root of, and infinitely augment, contemporary conceptions of the 'figurative' (Ricoeur 1967:10-18) - or by extension, of what images and art are. In the contemporary South African artist's work, the beauty and complexity of diverse simultaneous cultural and geographical notions of what images are and have been, are staged. Like the Renaissance Annunciation paintings, her "bone books" splendidly contribute to the process of differentiating and articulating discursive definitions of what images have been conceived to be.

Keywords: conceptions of iconicity, Annunciation, Pippa Skotnes, iconic difference, Eucharist, mytho-poetic symbolism, Paul Ricoeur.

Introduction

What would a history of art as a history of images look like? And how may such an approach contribute to the project of a World Art History? Early Modern awareness of the ability of artistic images to probe and share knowledge of their own nature has been variously divulged by Hans Belting (1994:458ff), Klaus Krüger (2001) and Barbara Baert (2013,2015), among other art historians. For Gottfried Boehm (according to Villinger 2021:946), this capacity of artistic images even implies that art history itself is 'a kind of iconic criticism where the agents of this criticism are the images themselves, which return to their older predecessors in order to cite them, to adapt, change, revert or otherwise criticize not only their forms, styles, objects and manners of representation but also their very conceptions of iconicity'.

A profound early modern and modern western awareness of a new dispensation for images comes about gradually during the Renaissance at the time when art is elevated to be considered above mere craft. The topos of the Annunciation is eminently suited to embody and display the various aspects of the humanlike nature of images - made by humans for the benefit of humans - of lifelikeness, of being able to point to something, of seeming to be alive, speaking or in conversation, ultimately pointing to the human image as the Imago Dei, to Christ's Incarnation always pointing beyond the body of Christ.

I argue that in the constellation of select Renaissance Annunciation paintings discussed here, Christ's Incarnation as Imago Dei, and the Eucharist as medium of presence, are evoked as historical presuppositions for a new early modern conception of images which is thus perceived as targeting the individual imagination. I suggest that in the early modern and modern notions of what images have been since the Renaissance, the spectator's imagination is personally addressed, just as the Virgin is addressed by the Angel in some Renaissance depictions of the topos of the Annunciation. I interpret the contemporary South African artist Pippa Skotnes's horse skeletons in resonance with this constellation of Renaissance Annunciation paintings to show how artistic image objects may knowingly point to profound historical changes in attitudes towards images.

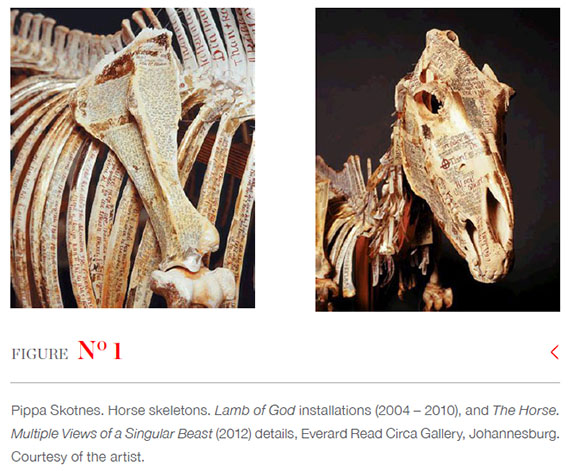

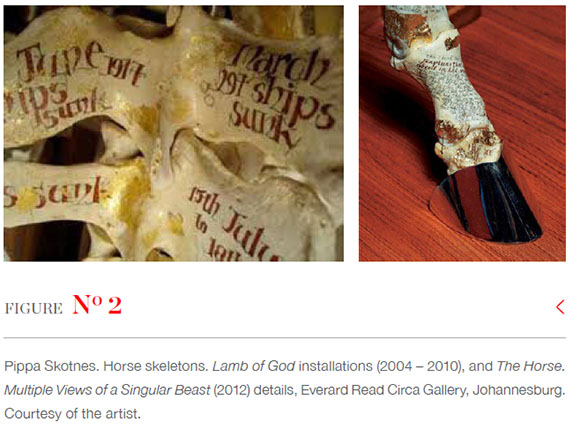

Pippa Skotnes's horse skeletons (Figures 1 and 2) were initially part of the Lamb of God installation at several international venues between 2004 and 2010.1 The installation is discussed and presented in Skotnes's (2009) published artist's book, Book of iterations. I first encountered them when they were exhibited separately as part of the exhibition The Horse. Multiple Views of a Singular Beast at the (Everard Read) Circa Gallery in Johannesburg in 2011. Not much has been written about Skotnes's conceptually sophisticated oeuvre from an art historical perspective.

Each of the three skeletons of the Lamb of God installations, held intact by its spine, resembles a book or illuminated manuscript and is punctiliously inscribed with fragments of texts related respectively to: on the first skeleton, superstitions about the Roman Catholic Eucharistic transubstantiation, on the second skeleton, fragments from the 13,000 pages of |Xam Bushmen transcriptions by Lucy Lloyd and Wilhelm Bleek during the 1870's, of oral accounts by |Xam teachers, and on the third skeleton, experiences of Skotnes's relatives during the two World Wars of the twentieth century. The archive of stories, pictures and words, created by Bleek and Lloyd, now in the University of Cape Town library,2 is invoked in this installation of bone books, by fragments of rolled up copies of documents in glass phials attached to one of the horse skeletons. The bone books are related to one another by their evocations of intercultural colonial violence and the destruction of traces of civilizations, counteracted by the artist's processes of compulsive inscription, archiving, preservation, touching and commemoration as if in an effort of resurrection or transubstantiation.

It is significant that Skotnes's interest in questions of 'real presence' in art and images was sparked in 1993 when she became involved in several court cases and was sued under the Legal Deposit Act of the South African Library for a mandatory copy of an (artist's) book she had made in 1991 and which contained several original prints (Skotnes 2001). This experience sparked her investigations into what an artistic image is, in relation to the significance of the "real presence" of the Eucharist. It became the theme of her inaugural lecture (Skotnes 2001) as Professor at the University of Cape Town, and inspired the "bone books" which interrogate not only the "artist's book" but the very historical roots of figuration, images and art.

In my interpretation, the exquisite horse skeletons imaginatively evoke similarities and differences among image functions over thousands of years, in a sophisticated imaginative fullness of allusions to earlier notions of what images have been: historical images as substitution, representation, magical presence, embalming, healing, imitation, as well as the "real presence" to the imagination, as in the Eucharist. I argue that the modern idea of the artistic image since the early modern era, may consciously and informatively resonate, as in Skotnes's "bone books", with conflicting historical and contemporaneous image understandings. I furthermore argue, that in the case of Skotnes, her interrogation, through art, of the nature of images and art is enhanced by her knowledge of indigenous Southern African image traditions - notably of the Khoisan/|Xam - through her curatorial, performative and artistic research.

Bones

The traces of Skotnes's obsessive writing on and handling, working, gilding, plating, touching of the once living bones of horses make them comparable to medieval reliquaries (Greenblatt 2009:58-71), and in the context of her installations, are reminiscent of acts of commemoration in the devotional use of the rosary (Hofmeyr 2009:76-101).

Bones are evocative media for a self-reflective exploration of the nature of artistic images, because skeletons are so closely related to founding conceptions of the image. Hans Belting (2011:84-124) has suggested from the perspective of his 'anthropology of images' that a historical grappling with questions of human life and death is at the origin of images.3

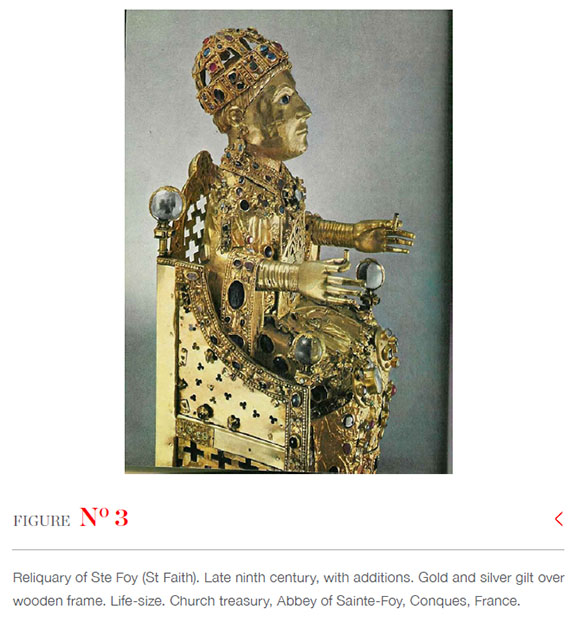

Relics and reliquaries, referenced in Skotnes's work, were signs of the presence of the bones of martyrs with us here, for example the reliquary of Ste Foy in the pilgrimage church of Ste Foy, at Conques, France (Figure 3). The history of this reliquary, which I will now discuss, shows the complex ways in which images have been involved in processes of translation, re-interpretation, and differentiation in incessant historical negotiations between the visible and the invisible, the human and the divine, and among diverse conceptions of the image. Moreover, it demonstrates that, although notions of the metonymical status of bones in reliquaries (which were believed to have healing powers) have not generally persisted until today, remnants of such image conceptions are palpable in beliefs and superstitions about the Transubstantiation. On one of Skotnes's three skeletons, she inscribed legends and superstitions about the storage of the consecrated Host which could for instance be eaten by mice. These stories which she encountered in the Convent school she attended, point to the persistence of such metonymic notions in the Roman Catholic Eucharistic Transubstantiation. During the Reformation such beliefs had been questioned when bread and wine were believed to merely be signs which guarantee the "real presence" of the Body of Christ in this world.

The golden doll with wide-open eyes and jewel-encrusted cloak serves as a case to enclose a bone fragment of the body of a girl who was martyred at the age of 12, early in the fourth century, according to Carlo Ginzburg's (2002:72) research. It has been discussed respectively by Carlo Ginzburg and Hans Belting as an example of historical and intercultural image exchange. The presence of bones in the shrine abolished the Roman religious ban on burial within the city walls and demonstrates a turning away from Roman image conceptions of substitution and representation of the Roman emperor. In the reliquary, gold and jewels serve as carriers of transcendental light, and like the miracles of healing which were supposed to take place in front of the shrine, they confirmed God's presence with us, presupposing the Eucharist - although a smattering of the metonymical status attributed to the imago of Roman emperors remains indubitably present (Ginzburg 2002:68-76) in the religious object - as it probably remains in conceptions of the Transubstantiation itself, as well.

In the process of restoring the reliquary statue, however according to Belting (1994), it was discovered that the body or cloak of the reliquary had been joined, towards the end of the tenth century, to a much older head which dates to the fourth or early fifth century. This head, made of gold and crowned with laurels, was discovered to be that of a deified Roman emperor (Belting 1994). In Roman rituals the waxen images of emperors were substitutes for their absent bodies and perpetuated their earthly existence. They could be ritually destroyed to eventually separate the bodies for departure, but the statues could establish real contact with the beyond (Ginzburg 2002:68-76). The union of this pagan head with the medieval reliquary shows how conceptions of iconicity have been reoriented, translated, re-interpreted and even inverted, in order to differentiate new image conceptions in incessant historical negotiations.

Iconic difference

Museum visitors of Skotnes's skeleton installations are invited into awkward stances and bodily postures in the museum space, to be able to restlessly read, inspect, and sense. This challenge to spectators to crouch, shift and unlock their bodies, reminds of participant positions in caves where Khoisan/|Xam rock paintings are often displayed on shallow niches and crevices, or on low rock overhangs, necessitating participants to even lie on their backs and re-orient their bodies in dynamic viewing positions (Skotnes 1994:321-325).4 Crevices are used compo-sitionally in paintings on the rock face, to suggest that images may 'slip through' the rock in a tiered universe, it has been suggested (Lewis-Williams 2002:156, Skotnes 1994:327). Skotnes's diverse body of art works referencing San or Khoisan/|Xam art may be described as performative research with a view, inter alia, to gain insight into its pictorial nature. With her bone installations, I argue, she poses complex and difficult questions about the comparative history and nature of images, making participants pause and slow down, to allow image objects philosophical space.

Comparable to the way in which, for Khoisan/|Xam painters, the materiality of the rock face itself had significance as the tangible interface between realms and was not merely a neutral support for paintings (Lewis-Williams 2002), Skotnes's skeletons overlaid in gold leaf, conjure up diverse historical and cultural types of interactions between the visible and the invisible. Skotnes's evocation of textures of light in her compulsive working of the bone surfaces through a variety of processes, suggests struggle with absence and presence not only in terms of the transubstantiation and the healing presence of reliquaries, but also in terms of the tiered and porous universe of Khoisan/|Xam painters in whose depicted and narrated "floating" world (Lewis-Williams 2000), the sense of time and of what is 'real' is constantly thrown into doubt (Skotnes 1996:23). Skotnes (2001:5) explains that her image-aware meta-artworks, the horse skeleton installations, were part of the result of her interrogations, in the context of the mentioned court case, of what constituted an artwork and 'how [an artwork] was, as an object, capable of being precisely what it did not appear to be'.

For Boehm (2007,2009,2011,2012) the very essence of the picture, is that it involves the interconnectedness of, or hinge between, what is visible and what is not (see Rampley 2012, Klonk 2020, Villinger 2021). "Iconic difference" which for him, ontologically speaking, characterises all images, entails the fundamental contrast between the materiality of the image, and all the individual events it encompasses; what is invisible beyond its material threshold. Therefore, for Boehm the image is an event, of the oscillation between identity (of the material object) and difference (of what it points to). The event, constituted anew in each image encounter, occasions a visually contrastive relationship or oscillation between a visible, and what may be called an imaginative, inner, or invisible component. The opaque impenetrability sparks an energetic flare of difference when an 'impossible' synthesis (Boehm 2012:124 cited by Rampley) occurs: the facticity of the material transforms itself into meaning. To explain this, Boehm relies on Edmund Husserl's notion of the horizon, where an oscillation occurs: the visible becomes invisible, and the invisible visible.

I draw on Gottfried Boehm's recent definition of the nature of the image as "iconic difference" to suggest that such early modern awareness of the fundamental nature of all images is visually conveyed in the select Renaissance depictions of the topos of the Annunciation. I mean to show that the visionary or imaginary fusion with the meaning of the immaculate conception, of pigment, materiality, and touch, through the presence of divine light, draws attention to the oscillation between the medium of painting itself and that to which it points. In the last chapter of Likeness and presence, Hans Belting (1994:471-472) describes this profound early modern dawning of a new dispensation for images when artists, like poets, attained the license to control (religious) subject matter, while taking into account sensual, perceptual and perspectival rules pertaining to nature and art - and when beholders were invited to be aware of their imaginative artistic conception of the subject matter.

The Annunciation

As event, the depiction of the Divine Incarnation through the Immaculate Conception seems impossible, because this occurrence remains incomprehensible and invisible to the human eye. The staging of a conversation between Angel and Virgin as the event of the Incarnation, thus presents the human body as fundamental to the very nature of images, emphasising the humanlike countenance of images.

Since the early modern and modern image has been conceded "meta-pictorial" (Mitchell 1994), "self-aware" (Stoichita 1997), "intelligent" (Elkins 2012), "knowing" (Marr 2016) and "pensive" (Grootenboer 2021) status, I want to ask to what extent the select constellation of aesthetically sophisticated paintings of the topos of the Annunciation in my following interpretation, are able to pictorially pre-figure and possibly historically deepen the understanding of Gottfried Boehm's recent discursive definition of the image.

The topos of the Annunciation, with its inevitable interruptive presence of divine light, lends itself most compellingly to stage the tangibly humanlike abilities of pictures to converse about the ineffable and the invisible. In her article 'Reading the Annunciation. The navel of the painting', Hanneke Grootenboer (2007) summons, for her argument on perspective, distinct positions on the topos of the Annunciation as "theoretical object" by among others, Erwin Panofsky (1971), Michael Baxandall (1974), Louis Marin (1989), Michael Ann Holly (1996),5 Georges Didi-Huberman (1992,2005) and George Steiner (1989). My re-interpretation is performed in terms of Boehm's (2011) more recent definition of the nature of images as Ikonische Differenz (iconic difference). In the light of his definition, I show the capacity of a constellation of Renaissance paintings of the Annunciation, to make sentient announcements about modern western understandings of images. I conclude, with reference to the recent work of the South African artist Pippa Skotnes, that current image understandings may resonate with conflicting cultural and historical image dispensations, in art.

The depiction of the Annunciation points to a peculiar image - Christ's human image as the image of God or imago Dei. By pointing to the invisible events of the Immaculate Conception and the anticipated presence of the body of Christ in this world, Renaissance pictures of the conversation at the centre of the Annunciation often stage an awareness of their own ambiguous image-ness. The human event of a conversation, involving gestures, breathing, hearing, movement (Baert 2013,2015) and changing demeanours (Baxandall 1974:48-57), is often presented or staged in Annunciation paintings as a bodily and imaginative interaction or image act between image and beholder (Bredekamp 2011). According to Barbara Baert: 'To step into the room [of the Annunciation] is to step into the process of Mary's conception, a conception that can only enable itself through the performative gaze of the beholder' (Baert 2015:201).

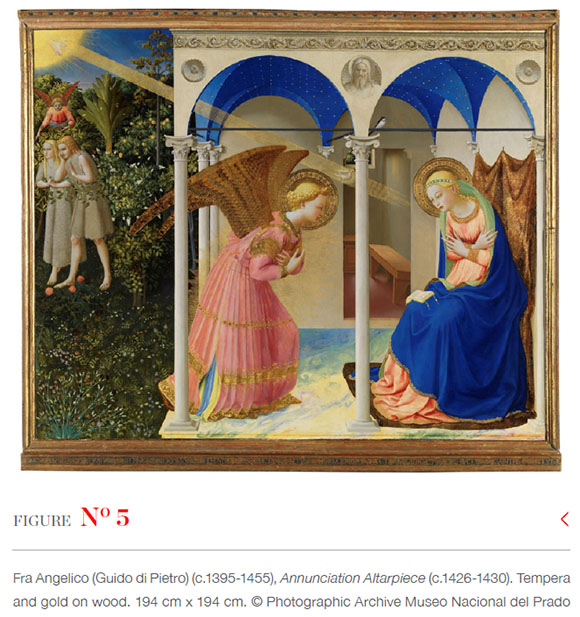

The punctum saliens, the leaping, striking or touching point of my argument, is the observation of the calculated separation which is mostly established between the Angel and the Virgin in Annunciation paintings, sometimes emphasised, during the Renaissance, by columns or an arch or open doorway, or even sometimes, as in Sandro Botticelli's Annunciation (1485) (Figure 4), by a seemingly impenetrable partition from the point of view of the spectator (Casey 2002:4). What I find remarkable about this deliberate evocation of non-touch in so many painted versions of the Annunciation over many centuries, is the way in which concomitantly in these same paintings, light is shown to break in on the scene in apparent compensation for the lack of contact between the Angel and the Virgin. Fra Angelico's Prado Annunciation (c.1426-1430) (Figure 5) serves as the first case in point, suggesting the blocking off of the observer, in order to open up a horizon of meaning.

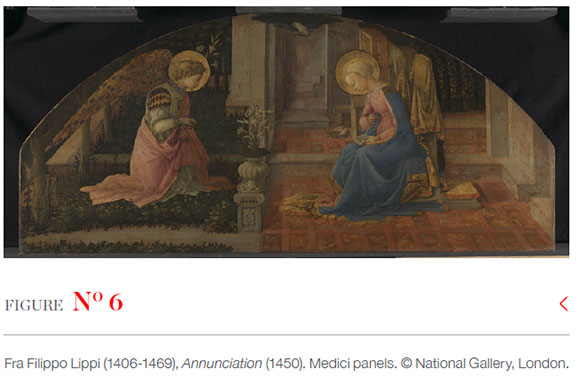

In this Annunciation, Angel and Virgin are divided by a Corinthian column from the point of view of the spectator (but not from those of the Virgin and Angel themselves). In addition, in the background of the charged interval between Angel and Virgin as seen from the point of view of the spectator, there is a door-opening in the rear wall. The phallic column partially blocks the beholder's view through the opening into the shadowy interior chamber behind as if to prevent entry or penetration, or to suppress all suggestions of it. However, counterpoised with the course of this virtually obstructed movement into the dim retreat at the back of the picture space, light enters the open portico in which the Virgin is seated, in her direction to the right, as golden rays extending from the Hand of God from the top left edge of the painting. The gilt rays transport a dove of the Holy Spirit to signify the distinction between this divine light of transcendental origin, and the sunlight which models and shapes the painted foliage visible through the rear window. The divine light which touches the Virgin evidently compensates for the spatial alienation between Virgin and Angel - as the dove almost touches the Virgin in Fra Fillipo Lippi's Annunciation (1449-1460) in the National Gallery in London (Figure 6) where it directly targets her womb.

Light

This, in each case, is a healing light which carries the Word of God turning into flesh. It bridges the impassable chasm between God and humankind at that moment when Christ enters the scene of human history through the Immaculate Conception and Incarnation. Like the speaking Angel, the bearer of good tidings, this redemptive light which touches the Virgin, and the Word which reaches her ears, bears the gift of salvation, thus urging the beholder to take cognisance of the oscillation between the transcendental and the visible.

In the Prado altarpiece (Figure 5) the golden ray of light aims at the Virgin's upper body clothed in a pink under-garment and enfolded in the shape of a safe receptacle by the golden hem of her blue over-garment. Similarly, light invades the sheltered space of the portico with its dark blue star-studded vaults, in a golden glow against the rear white wall behind the Angel, and even more spectacularly it is materialised in a marble-like pool of yellow and blue on the floor between Angel and Virgin. The golden and yellow splashes seem to visualise and displace the transforming effect of conception, by this gift-bearing light in the invisible womb of the Virgin. By attracting attention to the medium of paint in this self-aware way the imaginative effects of materiality, touch and light through brushwork and paint ignites the imagination of the pious viewer in a flare of "iconic difference" when the 'impossible synthesis' (Boehm 2012:124 cited by Rampley), referred to above, occurs.

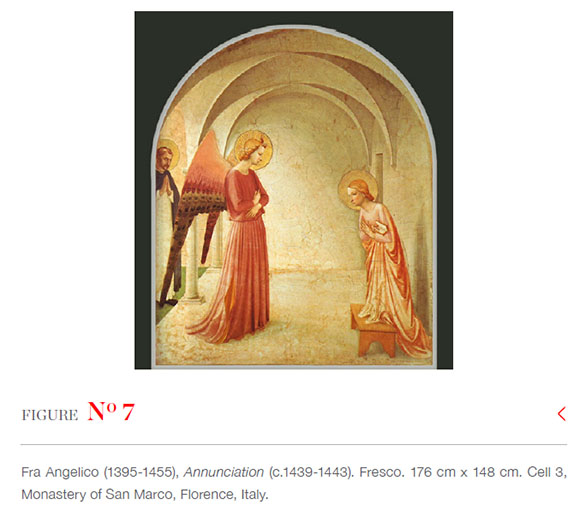

A comparable effect of 'luminous obfuscation' (to borrow George Didi-Huberman's (2005:11) phrase) to the marble-like floor is to be seen in another Fra Angelico Annunciation, a fresco from around 1440 in a monk's cell at the Dominican monastery of San Marco in Florence (Figure 7) where Fra Angelico himself was an inmate. The painted white cell extends the architecture of the cell in which the fresco is situated and there is "nothing" between the Virgin and the Angel, apart from luminous white pigment (Didi-Huberman 2005:11). Again, the invasion of the womblike place by light which seems to fall from the left in the direction of the Virgin, and is materialised in apparently incandescent pigment against the rear wall behind the Angel, not only evokes the transformational process of the Immaculate Conception, but also seems to effect the process of the Virgin's conversion, humiliatio or humble submission (Baxandall 1974:48-57), which sets the example of obedience for the painted onlooker to the left, the Dominican friar, St Peter Martyr.

The Eucharist

In more or less contemporary Northern renditions of the Annunciation (Figure 8) unabashed references to the uterus in the sacred act of conception are common in order to affirm Christ's humanity. In for example Hans Memling's Annunciation from around 1482, as Shirley Neilsen Blum (1992:44) has shown, not only is the nuptial bed a symbol of the sacred union between heaven and earth - Christ and his Bride, the Church - but in addition the very textured folds of the curtain knotted up into a curtain-sack between Virgin and Angel, are a reference to the Incarnation. To fifteenth-century observers the sack resembled the uterus of a woman. As Blum (1992:44) puts it:

Aristotle, still the basic source for the study of embryology in the fifteenth century, compared the formation of a fetus in the womb, to that of the curdling of milk in the making of cheese ... Moreover, the sack that stored the curds looked like a womb and hung down from a rafter not unlike the knotted curtain ...

The glass carafe placed on the stand to the left of the curtain sack in Memling's painting is another receptacle likened to the Virgin's womb - a solid, yet transparent object through which light passes as Christ passed through the Virgin's body. In the history of Christianity, the Virgin Mary has been a contentious figure about whom Gnostics like Iranaeus had asserted that Jesus had not been born of the Virgin Mary in the usual sense, but had 'passed through Mary as water runs through a tube', without her experiencing any birth pangs (Pelikan 1996:47). In response to this doctrine Mary was defined as the Theotokos and Mother of God around the fourth century to emphasise both the true Divinity and true humanity of Christ.

The reference to the shaping of the body of Christ in the womb of the Virgin is developed further in Memling's painting in association with the Transubstantiation. This further complicates pictorial references to the body and image of Christ. In this painting the Angel Gabriel is vested in a heavily embroidered cope in red and gold, secured by a large morse and worn over a long alb and an amice around his neck. The depiction of the Angel as not merely a messenger, but also as a subminister of the eucharistic rite was popular in Northern panel painting of the fifteenth century and connects the Immaculate Conception, Incarnation, and the Transubstantiation (Blum 1992:49). The shaping of the Body and Blood of Christ when he was conceived by the Holy Spirit in the Virgin's womb is thereby linked to the moment of the Transubstantiation. The curtain-sack and the Eucharistic messenger together suggest that just as the participant in the Holy Communion digests and thus touches the host, the Body of Christ touched the Virgin to become truly human while remaining truly Divine. Mary, like the participant through communion in the host, is changed through the body of Christ. On the other hand, the Body of the Church is created through participation in the sacrament. If we reread the San Marco fresco (Figure 7) in this light, the womblike cell surrounding the Virgin seems to overflow with light which cannot be limited or contained like the 'cosmic womb' of the Church of all ages (Mondzain 2005:164), whose representative Mary has been since patristic times.

Reorientation, inversion, transvaluation

The paintings of the Annunciations I have discussed are self-aware announcements of the possibility of images to function as media of presence to the imagination. The pious spectator of Angelico's fresco is placed in the shoes of the anachronistic Dominican friar, St Peter Martyr, to the left of the fresco, just outside the space of the cell, for whom it could not have been possible to witness the historical event of the Annunciation. The three diverse historical points of view firstly, of the event of the Annunciation, secondly of the world of the thirteenth-century Dominican friar and thirdly, of the era of the modern-day spectator, are thereby linked. This is an indication of an awareness of the image's function as a medium - the most basic definition of which (as defined by Lambert Wiesing (2010:130)) is that which makes the same thing present in diverse times and places. In fact, the Angel, who in the narrative has arrived to announce the birth of the Mediator of the Church of all ages, like the image itself, is a painted example of just such a medium. Regis Debray (1997:31-32) in his mediology (or history of media, or history of the means of transmission) refers to angels as media in a protomediology (a pre-history of technological media). He points out that in the case of angels the process of transmission has an intransitive character and that there is a hierarchy which entails a subordination or conversion in the recipient of the message. George Steiner (1989:143) describes the aesthetic effect in general, in similarly overwhelming terms, with reference to a Fra Angelico Annunciation in his book Real presences: 'If we have heard rightly the wing-beat and provocation of that visit, the house is no longer habitable in quite the same way as it was before'. Comparably Barbara Baert (2015:201) argues that: 'The act of walking deep into the room as the angel did, even frightening the Virgin, is repeated emotionally in us, the beholders'.

Christ's Incarnation as God with us, and the Eucharist as medium of presence, are thus evoked as presuppositions for a new concept of the image which personally addresses the spectator's imagination just as the Virgin is addressed by the Angel.

On the strength of Luce Irigaray's feminist philosophical critique, Cathryn Vasseleu has introduced the notion of The textures of light (1998) which criticises a long western tradition of the opposition of the sensible and the intelligible in the process of acquiring knowledge. According to Irigaray, Plato's metaphysics operates within a mythological cave which is analogous to a womb, but he re-places matter metaphorically in a metaphysical space. Sexual difference is disguised 'once the neck, the corridor, the passage has been forgotten' and the materiality of the passage or transition is covered over by resemblance (Vasseleu 1998:7-11). In the Annunciation paintings I have discussed, the materiality of light is shown to counteract the Platonic dissociation of light and touch when divine light is shown to enter, touch and transform this world 'in a flare of difference' (Rampley 2012:124).

This contrasts with image conceptions presupposing the production of substitutive illusions in a tragic human effort (see Mondzain above) to establish contact with an inaccessible beyond (Ginzburg 2002:63-93). The way in which the metaphoric significance of light is inverted in these Annunciation paintings points to a profound change in attitude towards images and draws attention to the pivotal place of the event of the Incarnation in the western history of conceptions of the image. The luminescent pigment conveys the healing of a tragic split between light and touch based upon an entirely novel relationship between God and humankind. In contrast to the constrained and surrogate human experience of 'self-presenting Being' in Plato's cave, light now enters the monk's cell from the outside (Vasseleu 1998:711). 'The platonic opposition of the cave fire to the sun of the Good, has been eliminated', as Hans Blumenberg (1993:38) puts it. In the Christian metaphorics of light, as is conveyed by the light-dispersing hand of God in Angelico Prado's painting, light is a gift of grace from God who is himself beyond the opposition of light and dark and has it at his disposal (Blumenberg 1993:41). The textures of light in the rendering of the Virgin and the Dominican monk in his white robe (Figure 4), turn them into what Blumenberg (1993:43) would call torches that have been touched by light.

Marie José Mondzain refers to this change - that images in their materiality reach out to the imagination of the beholder, presupposing the Eucharist - as the Passion of the image. She says: 'It is no longer the tragic speech of the Greeks, but the image that calms the violence of all passions' (Mondzain 2009: 28). The post-eucharistic Renaissance image is a medium of presence to the imagination and replaces or enriches other image notions like substitution, representation, and imitation where images have functioned to prolong the earthly presence of the dead or to establish human contact with the divine.

Blumenberg (1993:53) shows, however, that this enrichment of the metaphor of light has dwindled since, ironically, the so-called Enlightenment, when in the secularised meaning of the metaphor of light phenomena no longer stand in the light, but rather are subjected to the lights of an examination from a particular perspective. This reductive loss of sacrality in the use metaphors is usually described as the process of disenchantment.

Conclusion

French philosopher Paul Ricoeur especially in his two books, Figuring the sacred. Religion, narrative and imagination (1995) and The symbolism of evil (1967), profoundly rethinks the historical significance and importance of sacred symbolism, and for me he suggests new possibilities to describe the thickness of time in complex World Histories of Art. For him all symbolism or figuration is always only meaningful when it is borne by the sacred values of aspects of the cosmos themselves (Ricoeur 1995:53). Ricoeur (1967:10-18) shifts attention to the 'mytho-poetic', 'cosmic ground' of all symbolism. The wealth of modern figuration is 'guaranteed' by sacred human experiences of the natural world which characterised 'ancient' societies, and these experiences of mytho-poetic manifestations of the sacred in nature, are the 'ground' of all subsequent symbolic acts (Ricoeur 1967:10-18).

He argues that the display of the sacred in aspects of the cosmos cannot be completely articulated verbally in the Word. In the sacred universe the cosmos has the capacity to signify something other than itself which becomes immediately meaningful. Aspects of nature become transparent to allow the transcendent to appear, in what he calls 'bound' or 'adherent' symbolism. Ricoeur (1967:1018,1995:53) calls this mythical meaning, which is directly attached to the appearance and nature of rock, light, mountains, rivers, trees, and other natural elements, 'bound' or 'adherent' symbolism because it is not a product of free invention, but rather has sacred value on the basis of creational correspondences between nature and sacred human experiences. For Ricoeur (1995: 61-67) this direct manifestation of the sacred in nature was reoriented and inverted, but not abolished, by the proclamation of the Christian Word, and always remains the basis of the richness of all figuration or symbolic experience. The manifestation of the sacred is not completely translatable into linguistic articulation of the Word. Images, like the sacraments, surpass conceptual thinking.

Thus, for Ricoeur, Christian symbolism not only reaffirms, but also reorients, re-employs or even explodes ancient mythical symbolism. In the Christian world, so-called "archaic" symbolism (which persists in the modern world in a variety of forms) is re-described in terms of eschatological promise and hope, in an inversion rather than an abolition of the closed cyclical symbolism of the sacred cosmos. Whereas in Khoisan/|Xam image traditions the natural materiality of the rock face had numinous significance as the tangible interface between realms, such symbolic experiences of, fascination with, and fear of the sacred immanence manifesting in in elements like rock, for Ricoeur (1995:61-67) are reemployed, reoriented or 'transvalued', rather than abolished, 'when Golgotha becomes the axis mundi' (Ricoeur 1995:66).

In the above interpretation of a constellation of Renaissance Annunciation paintings, a reorientation and inversion of the ancient symbolism of light was seen, as well as the gradual transmutation of sacred symbolism into the meaning of the Eucharist - into the Body of Christ as the absolute and 'transvalued' manifestation of sacrality in this world. Artists of the Renaissance take part in this redescription or inversion of iconicity, when the incarnation becomes the justification of image making, and at a time when beholders and artists became aware of new imaginative, artistic and poetic conceptions of subject matter (Belting 1994:471-472).

An artistic 'transvaluation' is ostensibly at stake in Skotnes's bone work, when the violent destruction of traces of 'archaic' or sacred symbolism is powerfully interfered with, through her intense artistic processes of gilding, archiving, preservation, touching and commemoration, in what seems to be an effort of imaginative resurrection or transubstantiation of the rich roots of modern figuration (Ricoeur 1995:65). Skotnes's work resuscitates the power of sacred mytho-poetic symbolism at a time of the increasing awareness of the complexity of a World Art History when 'contemporaneity' is conceived to be anachronic and time is understood to have a multiplicity of textures (Moxey 2013:45,174).

Rather than as a progression to extricate itself from, or destroy the sacred, rendering the cosmos mute and indecipherable, Ricoeur (1995:48,61) describes the creational significance of sacred time in its fullness, its reorientations and present meaningfulness. He thus, for me, contributes the dimension of the symbolic significance of the sacred cosmos to current discourses on the meaning of history which appreciate cross-cultural, anachronic and thick time.

Since the Renaissance, artistic images with strong self-aware iconicity return to, invoke, and reassess predecessors - including mytho-poetic manifestations of the sacred in nature - to critically renew understandings of what images are. In this way artistic images, and their interpretations in art history and image studies, become agents of the self-scrutiny and criticism of images themselves. With the advent of the most sophisticated type of image, the artistic image, images have been refining and re-thinking their own definitions, functions and agency in performative ways.

Notes

1 . See http://stiftelsen314.com/oldweb/exhi_prog/pippa/index.html.

2 . See Skotnes (2007) and http://lloydbleekcollection.cs.uct.ac.za/.

3 . See especially the chapter 'Image and death: embodiment in early cultures', pp. 84-124.

4 . In a written communication to me in May 2023 Pippa Skotnes conveys: 'I also liked your comparison of viewing the bone books with viewing rock paintings - I don't think I ever made that comparison directly, but it is true'.

5 . See especially Holly's chapter on Witnessing an Annunciation, pp.149-167.

References

Baert, B. 2013. The Annunciation revisited. Essay on the concept of wind and the senses in late medieval and early modern visual culture. Critica D'arte 47-48:57-68. [ Links ]

Baert, B. 2015. The Annunciation and the senses: Ruach, Pneuma, Odour, in Between Jerusalem and Europe. Essays in honour of Bianca Kühnel, edited by R Barta and H Vorholt. Leiden: Brill:197-216. [ Links ]

Baxandall, M. 1974. Painting and experience in fifteenth century Italy: a primer in the social history of pictorial style. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Belting, H. 1990. Bild und Kult: eine Geschichte des Bildes vor dem Zeitalter der Kunst. München: C.H. Beck. [ Links ]

Belting, H. 1994 [1990]. Likeness and presence. A history of the image before the era of art, translated by E Jephcott. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Belting, H. 2011. An anthropology of images. Picture, medium, body. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Blum, S. 1992. Hans Memling's Annunciation with angelic attendants. The Metropolitan Museum Journal 27:43-58. [ Links ]

Blumenberg, H. 1993. Light as a metaphor for truth. At the preliminary stage of philosophical concept formation, in Modernity and the hegemony of vision, edited by DM Levin. London: University of California Press:30-62. [ Links ]

Boehm, G & Egenhofer, S (eds). 2010. Zeigen: die Rhetorik des Sichtbaren. München: Wilhelm Fink. [ Links ]

Boehm, G. 2010 [2007]. Wie Bilder Sinn erzeugen. Berlin: Berlin University Press. [ Links ]

Boehm, G. 2011. Ikonische Differenz. (Glossar. Grundbegriffe des Bildes). Rheinsprung II. Zeitschrift für Bildkritik:170-176. [ Links ]

Boehm, G. 2012. Representation, presentation, presence: tracing the Homo Pictor, in Iconic power. Materiality and meaning in social life, edited by J Alexander, D Bartmanski and B Giesen. New York: Palgrave Macmillan:15-23. [ Links ]

Bredekamp, H. 2011. Theorie des Bildakts: Über das Lebensrecht des Bildes. Berlin: Suhrkamp. [ Links ]

Bredekamp, H. 2018. Image acts: a systematic approach to visual agency. Berlin: De Gruyter. [ Links ]

Debray, R. 1997. The exact science of angels. A venerable protomediology, in Transmitting culture, edited by R Debray. New York: Columbia University Press:31-44. [ Links ]

Didi-Huberman, G. 1995. Fra Angelico: dissemblance and figuration. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Didi-Huberman, G. 2005. Confronting Images: questioning the ends of a certain history of art. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press. [ Links ]

Dowson, TA & Lewis-Williams, D. 1994. Contested images. Diversity in Southern African rock art. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press. [ Links ]

Casey, E. 2002. Representing place: landscape painting and maps. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Elkins, J. et al. (eds). 2012. Theorizing visual studies: writing through the discipline. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Ginzburg, C. 2002 [1998]. Representation. The word, the idea, the thing, in Wooden eyes. Nine reflections on distance, edited by C Ginzburg, translated by M Ryle and K Soper. London: Verso:63-78. [ Links ]

Greenblatt, S. 2009. On real presence, in Book of iterations, edited by P Skotnes. Cape Town: Axeage Private Press and Centre for Curating the Archive:58-71. [ Links ]

Grootenboer, H. 2007. Reading the Annunciation: the navel of the painting. Art History 30(3):349-363. [ Links ]

Grootenboer, H. 2021. The pensive image: art as a form of thinking. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Hofmeyr, I. 2009. A miraculous history of the book, in Book of iterations, edited by P Skotnes. Cape Town: Axeage Private Press and Centre for Curating the Archive:76-101. [ Links ]

Holly, MA. 1996. Witnessing an Annunciation, in Past looking: historical imagination and the rhetoric of the image. London: Cornell University:149-167. [ Links ]

Irigaray, L. 1977 [1985]. This sex which is not one, translated by C Porter and C Burke. New York: Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

Irigaray, L. 1993 [1984]. An ethics of sexual difference, translated by C Burke and GC Gill. New York: Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

Klonk C. 2020. Visual studies, in Glossary of morphology. Lecture notes in morphogenesis, edited by F Vercellone and S Tedesco. Springer: Cham:528-531. [ Links ]

Krüger, K. 2001. Das Bild als Schleier des Unsichtbaren. Ästhetische Illusion in der Kunst der frühen Neuzeit in Italien. München: Wilhelm Fink. [ Links ]

Lewis-Williams, JD (ed). 2000. Stories that float from afar. Ancestral folklore of the San of Southern Africa. Kenilworth: David Philips. [ Links ]

Lewis-Williams, JD. 2002. The mind in the cave. Consciousness and the origins of art. London: Thames and Hudson. [ Links ]

Marr, A. 2016. Knowing images. Renaissance Quarterly 69:1000-1013. [ Links ]

Meiss, M. 1945. Light as form and symbol in some fifteenth-century paintings. Art Bulletin 27(3):175-181. [ Links ]

Mitchell, WJT. 1994. Picture theory: essays on verbal and visual representation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Mondzain, M-J. 2005. Image, icon economy. The Byzantine origins of the contemporary imaginary. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [ Links ]

Mondzain, M-J. 2009. Can images kill? Critical Inquiry 36:20-51. [ Links ]

Moxey, K. 2013. Visual time. The image in history. Durham: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Pelikan, J. 1996. Mary throughout the centuries: her place in the history of culture. New Haven: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Rampley, M. 2012. Bildwissenschaft: theories of the image in German-language scholarship, in Art history and visual studies in Europe transnational discourses and national frameworks, edited by M Rampley. et al. Leiden: Brill:119-134. [ Links ]

Ricoeur, P. 1967. The symbolism of evil, translated by E Buchanan. Boston: Beacon Press. [ Links ]

Ricoeur, P. 1995. Figuring the sacred. Religion, narrative and imagination, translated by D Pellauer, edited by MI Wallace. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Schwartz, RM. 2008. Sacramental poetics at the dawn of secularism. When God left the world. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [ Links ]

Skotnes, P. 1994. The visual as a site of meaning. San parietal painting and the experience of modern art, in Contested images. Diversity in Southern African rock art, edited by TA Dowson and D Lewis-Williams. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press:315-330. [ Links ]

Skotnes, P (ed). 1996. Miscast. Negotiating the presence of the Bushman. Cape Town: UCT Press. [ Links ]

Skotnes. P. 2001. Real presence. Inaugural lecture of Professor Pippa Skotnes, Michaelis School of Fine Art, University of Cape Town, 3 October 2001. New series nr. 225. Published by the Department of Communication and Marketing, University of Cape Town:1-16. [ Links ]

Skotnes, P (ed). 2007. The archive of Wilhelm Bleek and Lucy Lloyd. Claim to the country Johannesburg: Jacana and Athens: Ohio University Press. [ Links ]

Skotnes, P. 2009. Book of iterations. Cape Town: Axeage Private Press and Centre for Curating the Archive. [ Links ]

Skotnes, P. 2010. A columbarium of words and a mode of locution, in On making: integrating approaches to practice-led research in art and design, edited by L Farber. Johannesburg: The Visual Identities in Art and Design Research Centre (VIAD), Faculty of Art, Design and Architecture, University of Johannesburg:248-262. [ Links ]

Steiner, G. 1989. Real presences. Is there anything in what we say? Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Stoichita, VI. 1997. The self-aware image: an insight into early modern meta-painting, translated by A-M Glasheen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Vasseleu, C. 1998. Textures of light. Vision and touch in Irigaray, Levinas and Merleau- Ponty. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Villinger, R. 2021. Gottfried Boehm, in The Palgrave handbook of image studies, edited by K Purgar. London: Palgrave Macmillan: 937-950. DOI: doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-71830-5_56 [ Links ]

Wiesing, L (ed). 2010. What are media? in Artificial presence: philosophical studies in image theory, Stanford: Stanford University Press:122-146. [ Links ]