Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Kronos

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9585

versão impressa ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.50 no.1 Cape Town 2024

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-9585/2024/v50a3

ARTICLES

Violence and the Voice Note: The War for Cabo Delgado in Social Media (Mozambique, 2020)1

Paolo Israel

Department of Historical Studies, University of the Western Cape

ABSTRACT

In Cabo Delgado, Mozambique, the year of 2020 marked a dramatic escalation of military activities of the Islamist insurgent group locally known as Al-Shabab or mashababe. This intensification was accompanied by a more immaterial phenomenon: the rise in prominence of social media, both as battleground and as public forum. While the insurgents sacked and occupied major towns and district headquarters, the Web 2.0 networks - Facebook and WhatsApp especially - became the central arena in which the war was apprehended and discussed. This essay is an exploration of the entwining of social media with the 'new war' in Cabo Delgado, focussing on the events that surround the conquest of the Makonde plateau, mythical cradle of the Mozambican liberation struggle. Building on a budding literature on digital militarism, the essay dwells especially on orality and the use of the voice note as a medium to convey information deemed to be more trustworthy and stable than images. Tracking these media and their interrelations, the essay establishes a narrative, however fragmentary, of the downfall of the Makonde plateau; highlights recurring features of violence in the Cabo Delgado conflict; and provides fresh insight into the formation of the Local Force (Força Local), a State-sponsored militia largely constituted by war veterans.

Keywords: Social media, digital militarism, jihadism, orality, Mozambique, Cabo Delgado, Makonde

Nodes of intensification

In the province of Cabo Delgado, in Mozambique, the year of 2020 marked the explosion of military activities of the Islamist insurgent group known as Ansar Al-Sunna, Ahlu Sunnah Wal Jamaa and, locally, as Al-Shabab or mashababe.2 For about two years since the initial attacks on Mocímboa da Praia of 5 October 2017, the insurgents operated largely through small scale raids. The situation changed in the second half of 2019, after the group paid formal allegiance (bayat) to the Islamic State. Beheadings, kidnappings and the torching of villages escalated. The insurgents also expanded southwards of their original area of operations, nesting in the thick forested region around the Messalo River, in the hinterland of the district of Macomia.

From February 2020, the insurgents engaged governmental forces on a variety of fronts. The first important clash occurred in the abandoned village of Mbau, in the hinterland of Mocímboa, where the insurgents routed in frontal combat over 120 soldiers of the Mozambican army. For whoever was not fooled by the government's denialism, this was the first sign of the movement's military capabilities. In March, the insurgents stormed Mocímboa with a coordinated action, occupying it for one day and redistributing goods and money among the local population. In April, they ventured onto the Makonde highlands, mythical battleground of the Mozambican liberation struggle and stronghold of the ruling party Frelimo (Front for the Liberation of Mozambique). In the six months that followed, the Al-Shabab would lead a military onslaught on the whole of the Cabo Delgado province, leading to the occupation of Mocímboa and the storming of district headquarters such as Macomia and Quissanga. In November, they returned to the Makonde plateau, occupying several villages for weeks. As a result, an estimated 800,000 displaced persons flooded into the city of Pemba and in refugee camps and villages located in the south of the province as well as Nampula.3

The escalation of violence was accompanied by a more immaterial phenomenon: the rise in prominence of social media, both as battleground and as public forum.4 Whereas before the pledge of allegiance to the Islamic State, the group's communication had been all but inexistent, with a single short clip circulated in the aftermath of the first attacks, from 2020 onwards the insurgents publicised their military actions by way of images and films, diffused via the social networks and on the Islamic State's official outlets. The Mozambican government, gradually acknowledging the existence of a 'terrorist threat' that it had previously stubbornly denied, responded by circulating, whenever possible, images of defeated insurgents and (re)captured weaponry and equipment.5 In a context of dearth of information and government crackdown on conventional media, the social networks, especially Facebook and WhatsApp groups, became a vibrant forum for the sharing and commentary of information and images.6 Displaced people who were cut out from their families also recurred to digital means of communication to learn about the whereabouts of their dear ones, the fate of their homes and villages, and to make sense of the events. Gradually, the social networks became the major arena in which the war was apprehended and discussed, shaping the sense of its reality - and hyperreality.7

This essay is an exploration of the entwining of social media with the 'new war' that is ravaging Cabo Delgado.8 I focus on the year of 2020, and especially on the events that surrounded the insurgents' expansion towards the Makonde plateau. This angle reflects my own position, as a researcher with twenty years of frequentation of the Makonde country, many friends, and a little house in the village of Mwambula, who followed the turn of events from a COVID-imposed isolation with a sense of anxiety and dismay.9 At the time, embedding myself in local WhatsApp groups and frantically scrutinising and collecting clips and images was a matter of personal investment, rather than research. Here, I try to bring an element of reflection to that archive. This narrow focus and my linguistic competence in Shimakonde - I would not have been able to carry out the same work with material in Kimwani or Emakhuwa, the other two main languages of the province - allow me to pay close attention not only to images and text, but also to orality, a medium that has been by and large ignored by discussions of social media and warfare.

In the past decades, a substantial literature has discussed the interface of media and militarism. While initially much ink was poured on the virtuality of war, embodied in the spectacle of the American invasion of Iraq, with the emergence of Web 2.0 technologies the emphasis shifted from State control to horizontality, contingency, fragmentation, mobilisation, multiplicity and user-led content. The Abu-Ghraib scandal, the Arab Spring revolts, Operation Cast Lead in Palestine, the rise of the Islamic State in Syria, the Russian invasion of Ukraine: these are some of the landmark moments of this process of dispersion and democratisation of information. Increasingly, studies demonstrated the importance of platforms such as Twitter and Facebook to shape public opinion, triangulate information and substantially change the nature of conflict.10 This phenomenon was also scrutinised in relation to violent extremism.11 A number of studies paid attention to local responses to insurgency and conflict in Africa, articulated through social media, especially Twitter.12 Among those, George Agbo's work on the visuality of Boko Haram stands out for empirical richness and analytical subtlety.13

In all these accounts, visuality and the written word have taken centre stage. With the present intervention, I shift the focus to the medium of orality. In the case of Cabo Delgado, orality, more than visuality, was invested with the burden of bearing truthful testimony. The format of the voice note - recorded conversations, speech or sound - was especially important in this respect. As the war escalated, a mistrust for mainstream media was widespread in all social networks. The national ones were considered to be on the government's payroll; the international, either ill-informed or serving some hidden agenda. The Net was rife with conspiracy theory. Images turned out to be especially unstable. In the aftermath of the battle of Mbau, for instance, pictures of dead soldiers and insurgents circulated, which ultimately turned out to come from the Eastern Congo. In a classic Platonic move, voice was held to a more reliable referent of truth, at least for people not privy to secrets held in high places. While photographs and videos were subjected to forensic analysis carried out by foreign actors with sophisticated technological means - geo-triangulation, magnification, face recognition14 - audio clips constituted the object of a 'popular forensics' in which local people, for once, had an edge.15 Accent, intonation and indexical elements conveyed clues that could be decrypted only by local persons, to assess the veracity of audio clips or at least gauge their meaning. Thus, they became the preferred medium for relaying testimonies from the war zones. This is not surprising in a society in which orality has a central importance and spoken language is fundamentally permeated by the rhythms of traditional storytelling.

The media I discuss here were shared in multiple platforms - especially WhatsApp groups, Facebook, YouTube channels and local grassroots media - and generally marked with the mention 'forwarded many times', which makes the attribution of origin or authorship impossible and constitutes them as public.16 This is also an ephemeral archive: because of the fragility of the infrastructure, the ubiquitousness of viruses, or simply lack of archival interest, media get erased or lost. I may be one of the few people in possession of some of these fragments, as widespread as they may have been at the time.17

My approach in dealing with this material is narrative. Rather than engaging in a systematic analysis, I focus on specific events, which - like Benjaminian 'flashes in the moment of danger' - represent nodes of intensification both of warfare and of media language.18 This strategy reflects the fragmentary nature of social media and its multiple and disjointed temporalities.19 In the handling of the material, I was influenced by Svetlana Alexievich's work in oral history, in sensibility if not in method.20 Much like her orchestrations of voices, this is a downbeat tale.

For ethical reasons, I do not engage in any sociological analysis of platforms in which these media clips were circulated, as I did not participate in them as a researcher.21 Therefore, I do not discuss, if not in the broadest manner, user comments. I do, however, avail myself of the common sense and philological expertise available in these platforms - and of my own judgment and intuition - to gauge the veracity or at least plausibility of these snippets of sound and video. While in the age of poststructuralism, academics tend to muddle the line that separates truth from falsehood, for people affected by the war holding fast to the line was a matter of life and death.22 Rather than cynically celebrate its dissolution, one should therefore try to work with the line, however uncertainly.

The narrative established through these fragments and flashes sheds light on a number of aspects of the 'new war' fought in Cabo Delgado. In an insightful article, Bjørn Enge Bertelsen identifies the central characteristics of global war in the twenty-first century, as seen from Mozambique: the dissolution of the distinction between military and civilians; the increasing importance of stealth, dissimulation and blur; and the intensification of outbursts of spectacular violence (or 'visual excess', as he calls it).23 These points are very relevant for the material at hand and recur like leitmotifs in my narrative.24 The current conflict also bears witness to a dynamics typical of the Mozambican civil war: the tendency for civilians to be crushed between the hammer and the anvil of two - or more - warring factions. Thus, the war in Cabo Delgado appears both as fundamentally new and as haunted by the repetition - or intensification - of the same.25

This narrative also illuminates a phenomenon that is assuming increasing relevance in the unfolding war: the role of popular militias in containing the insurgency. The existence of these militias, which go under the name of Força Local (Local Force), was legally sanctioned, after much hesitation, in November 2022.26 For obvious reasons, the history and operation of this paramilitary group is surrounded by secrecy. The material discussed here opens a window into the early phases of the formation of the Força Local, including an extensive first-person oral account by one of its members. The other face of the coin, which the social media bare tragically, is the state of disarray of the Mozambican army, which translated into outbursts of violence against suspected insurgents and civilians. This alienated the army from the civil populations, who increasingly saw it as an oppressor rather than a liberator - a role taken by the Rwandan military after its arrival on the scene in 2021. This resulted into an increasing disaffection with Frelimo in its oldest and most faithful stronghold, especially on the part of the youths. The future of political allegiances - and even national sovereignty - in northern Mozambique is in rapid flux.27

I. A fortress besieged

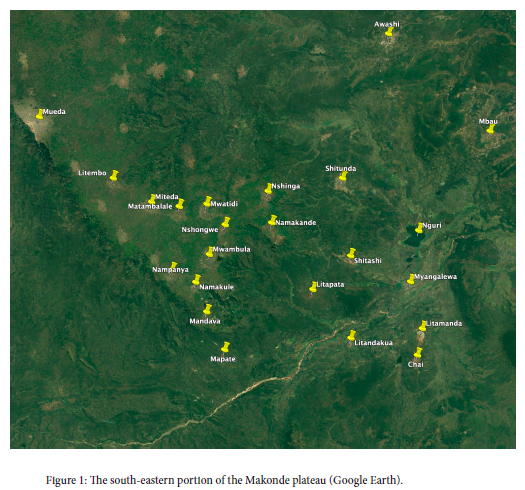

Rising south of the Rovuma River for an extension of about two hundred kilometres, to a height between six and eight hundred meters above sea level, the Makonde plateau has the geographical characteristics of a natural fortress. Whereas to the north the plateau shelves somewhat gently onto the Rovuma River valley, to the east, where it is closer to the sea, its profile is jagged and at times vertical, streaked by steep gullies and ravines [Figure 1]. During the two centuries in which the slave trade ravaged the coast and the hinterland of Cabo Delgado, the populations who took refuge on the plateau came to forge a common identity.28 To be a Makonde - literally, a person living in the fertile highlands - was a political choice, implying life in autonomous settlements under the loose leadership of a lineage elder, without centralised authority, in opposition to the Islamic chiefships established on the coast and the hinterland, which acted as raiders and middlemen of the Indian Ocean slave trade.29 The Makonde called the expanses below the plateau 'slavelands' (kunavashagwa) and their inhabitants 'slaves' (nshagwa). This didn't prevent them from trading with their neighbours - especially the coastal Mwani - and from dabbling in slave raids too. The lowlands at the edge of the plateau - south, near the Messalo River; east, near the sea; and north, near the Rovuma River - became intense zones of intercultural contact and friction.

The plateau was 'pacified' by the Portuguese between 1917 and 1921, in the course of the military operations of the First World War.30 Also because of an anti-Muslim sentiment rooted in the history of the slave trade, the Makonde became receptive to missionary activity.31 The mission of the Sacred Heart of Jesus of Nangololo, the second in the province, was established in 1937; and four more in the following decades, one of which, Nambudi, in the grasslands east of the plateau, near Mocímboa da Praia, where many Makonde resettled during colonialism. The missions offered an opportunity for education. Even so, many Makonde fled colonialism to pursue better economic opportunities across the border, in the sisal plantation and urban spaces of Tanganyika.

From 1964, the plateau became one of the core battlefields of the anti-colonial guerrilla waged by Frelimo, largely because of its geographical imperviousness and the recalcitrance of its inhabitants to submit to colonial rule. In the aftermath of the ten-year struggle, the place was mythified as the cradle of the Mozambican revolution. In spite of some resistance, Frelimo's programme of socialist villagisation was implemented with unmatched intensity. The social landscape of mobile autonomous settlements was radically reshaped into an organised network of communal villages, each gathering several thousand people, subjected to vertical party authority.

When in the 1980s the civil war between Frelimo and the anti-governmental movement Renamo spread into the north, the Makonde plateau was sheltered both by its geographical position and by the density of war veterans and militias trained during the liberation war. In the late 1980s, Renamo made headway into the lowlands laying at the south-east of the plateau, in the district of Muidumbe, near the Messalo River, an area of dense woodland and marshes. For two years, the rebels nested in the remote lowland villages of Mandela and Mapate, subjecting the plateau to occasional raids and bazooka fire. In 1991 they climbed the highlands to occupy the headquarters of the district of Muidumbe and the mission of Nangololo, only for a handful of days, until they were repelled by the coordinated effort of war veterans and militiamen.

At the dawn of the third millennium, the fabric of revolutionary socialism, which so drastically shaped the landscape of the Makonde plateau, gradually came undone.32 Under the presidencies of Joaquim Chissano and Armando Guebuza, war veterans were showered with pensions to ensure their support. Socialist governance structures were diluted and disempowered. Militia groups, formerly under the order of village presidents, were disbanded or turned into community police. Collective duties such as cleaning the public spaces or participating in political gatherings were no longer enforced. The communal villages expanded haphazardly, pushing against one another and breaking the previous geometry of order and vigilance. Opposition parties were granted right of presence and campaigning. Many youths lost interest in agriculture, living off their parents' war pensions or moving to the cities. They also began to timidly voice a critique of the elites' corruption and nepotism, especially by way of music. The discovery of gas, rubies and graphite in the province was met with high hopes of collective employment and drastic modernisation. The election of a Makonde to the presidency - Filipe Nyusi, nephew of an infamous sorcerer guerrilla and former pupil of the Frelimo revolutionary schools - was taken as a guarantee that the revenues from the extraction would be shared, if not fairly, at least with an eye to the president's homeland.

News of the insurgent attacks of 5 October 2017 in Mocímboa were met in the Makonde plateau with surprise and disbelief, as something difficult to acknowledge, understand or even name.33 The Makonde tended to look down at coastal Mwani people as backward, uneducated, unconnected and generally lacking initiative. People made jokes about the insurgents' name, mashababe, referring to them as bila sababu, 'without reason'. Most understood the attacks as passing disturbances. Someone would sort it out - general Chipande, Pachinuapa or Nyusi.34 Surely the chiefs wouldn't leave the precious resources slip away from their fingers? People whispered of summary executions and mass graves of killed insurgents.35

The awakening was brutal. In 2018, the insurgents moved their areas of operation eastward from the district of Palma, nearing the contours of the Makonde plateau. The border district of Nangade came repeatedly under attack. The following year, the insurgents pushed south of Mocímboa. In all likelihood, this was motivated by their strong support base in the coastal areas of the district of Macomia and by the impenetrability of the rectangle of forest comprised between Mocímboa at the north, the Messalo at the south, and the national road N380 on the west. This move led the insurgents into a friction area with the south-eastern portion of the Makonde plateau. First to be attacked and vacated were the two Makonde outposts in the grasslands south-east of Mocímboa, Nakitenge and Mbau, site of the mission of Nambudi. Then the attacks turned against the villages lying along the national road, in the shade of the plateau, mainly inhabited by Makonde who favoured the proximity of water over the traditional attachment to the highlands.36 Many abandoned their homes, rejoining their families on the plateau. Those who stayed did so because of lack of better opportunities. Due to the renewed pressure of the insurgents, the militia groups formed under socialism were reactivated and strengthened. Because the insurgents often wore uniforms stolen from the Mozambican army, rumours were rife that they were but a covert operation, a plan brewed by corrupted sectors of the State - President Guebuza was often named - to derail the extraction of resources.37 Many referred to the insurgents as 'treasonous soldiers'.

It is in this context of suspicion and paranoia that a warning sign about the tense relationships between the Mozambican military and the civilians came in the form of a video clip circulated in social media in the month of January 2020. This is the month in which the rites of passages into adulthood 'come out' and boys and girls return to the community as adult men and women.38 It is a time of joy, revelry, noise, drunkenness and symbolic inversion. The clip shows a group of young men, walking and singing: 'Here in Nambayaya - God, I can return only after I die.' This is a song from the women's nkamangu ordeals, from which men are barred from participating. Like women returning from the bush, the men in the video sway branches in the air somewhat aggressively. The person filming follows the crowd and reveals, at the head of the procession, a group of soldiers. The soldiers march hurriedly and never turn back to address or respond to the crowd that follows them.

The location of the video was identified as Namakande, the new headquarters of the district of Muidumbe.39 The clip itself was interpreted as an instance of citizens 'chasing away' soldiers for failing in their duty to protect the populations, or even consorting with the enemy. This event was never reported in any official news. Nobody clarified either why a group of young men chose a song from women initiation rituals to challenge the national military, or how the soldiers reacted to the provocation. One can only unpack the symbolic resonances. The nkamangu is the best guarded of all initiation secrets: women are known to post sentinels where the ordeals unfold and to ruthlessly thrash any intruder. Were the young men hinting at the secrecy and stealth surrounding the war? Or at the dogged perseverance of women to protect their prerogatives - and metonymically their culture and homeland?40 Were the youths implying that they had become like women, weaponless and at the mercy of the enemy?41 Or was the song itself the message, with its echoes of unescapable death and doom? At any rate, the video conveyed a creeping feeling: the Makonde plateau was forsaken, besieged and betrayed.

II. Of fences and massacres

The onslaught was brought on 6 April, eve of the national festivity of the Mozambican woman, only two weeks after the insurgents had demonstrated their muscle by storming the town of Mocímboa da Praia. The villages of Myangalewa and Shitashi, at the foot of the plateau, came first under attack. On that very day, two videos in which the insurgents addressed the populations of the Mbebedi neighbourhood in Mocímboa, during the March occupation, leaked on social media. The two clips show the person who was later revealed to be one of the leaders of the insurgency - Bonomade Machude Omar, the 'King of the forest' - haranguing a crowd, among a group of relaxed insurgents, wearing mismatch uniforms stolen from the Mozambican army, together with headscarfs, backpacks, tennis shoes or sandals.42 In a boastful and excited language, Bonomade presented the Al-Shabab's project as one of social justice:

Look at the prisons. You can see many poor people in jail. The jails are full of them. Only people from outside lie in jail. Is a chief imprisoned? Have you seen once a chief being imprisoned? This isn't ruling (utawala). This is a rule of unbelief (ukafiri). An impure (haramu) rule. All right? Today we came, we didn't destroy anything belonging to anybody; if we destroyed something it is because it belonged to the government.

After this accommodating beginning, Bonomade promised retaliation to all who kept on attending the meetings held by the 'pigs' (nguruwe), meaning the soldiers. 'The third time that we come in, we won't give you another chance, we won't be forgiving. […] Nobody: there won't be any pity.' The timing of the release led several international observers, who could not decrypt the indexical references, to misattribute the videos to the April attack and to infer that the insurgents had addressed in such a way the people of Myangalewa, rather than Mocímboa. This made little sense, as few residents of Myangalewa are Kimswani speakers. Reports from the grounds noted that there was an attempt to do so, by megaphone, but that people fled or locked themselves into their houses.

On the morning of the 7th, the insurgents climbed the plateau via the colonial road that connects the village of Shitunda to that of Nshinga. The physical distance is short - six kilometres as the crow flies - but a symbolic abyss separates the two. Shitunda is a lowland outpost, whereas Nshinga sits on the highlands, in the proximity of Frelimo's central base, where an open-air museum celebrating the anti-colonial deeds of Mondlane and Machel was opened in 2005.

It is in this conjuncture that the voice note emerged as a means of obtaining and sharing information about the war. For lack of good connection and the scarcity of touch-screen devices, no images could be obtained from the war zones. Thus, people from the cities phoned friends and relatives in the villages to know their whereabouts and understand what was going on. Initially, the accounts were related in a separate voice note by the caller. The sound clips were then posted onto WhatsApp groups; and in one way or another reached the grassroots media outlet, Pinnacle news, which through its Facebook page and WhatsApp groups is the foremost shaper of a subaltern public sphere in northern Mozambique.

The first sound clip, coming from Nshinga, was encouraging, indicating that the insurgents had addressed the populations like they had in Mocímboa:

The insurgents entered Nshinga in the morning. They did a meeting with some people who were taken hostage, according to which everybody must adhere to the Islamic faith. With this, they destroyed a Catholic Church and took four people; two with a group that went to Namakande, to show them the way; and two more to show them Mwatide. They didn't kill anybody, didn't destroy other goods.43

In all surrounding villages, people took to the bushes. Meanwhile, only four hours after the beginning of the attack, the insurgents released two videos on the Islamic State official media outlet, which showed them circling and storming the district headquarters at Namakande, wearing mismatched uniforms and weaponry captured from the Mozambican army. This was the first footage ever made public of a war operation. The attack was confirmed by a voice note related in the third person:

They say that: in Namakande, they put fire to the BCI [a bank]; the government building, they destroyed it; going to the crossroads, they set fire there as well; the hospital in Mwatidi, I don't know what's happening; and the school in Luanda, there was gunfire as well. In Matambalale, Mwambula, Nshongwe, all the people are in the bush. […] They haven't been eating since morning. These are the news of today.44

Reports of a pushback against the attack set the hopes of the online community aflame. One voice note referred to a response from the soldiers stationed in Namakande. A second one attributed the resistance to militias, which would have taken the matter into their own hands:

Look, brother, there is a terrible reaction here: insurgent casualties in this very moment. The population of the village of Muidumbe, the elders - those who asked for weapons to the President and he didn't give45 - invaded the barracks and took the weapons, told the soldiers: 'Nobody comes out from here and nobody comes in.' And it's them who are responding against the insurgents who wanted to head towards Mueda. Now, there are thirty casualties against the insurgents. Thirty. In this moment, the exact number is thirty-two. The youngster who is calling me is a soldier, who is afraid, in this moment, because his weapons were snatched by these oldsters. Do you understand? The old people don't want to know anything about orders from your side - Maputo, there. From our uncle. They don't want to hear about it.46

The war veterans' reaction would have been enabled by superior knowledge of terrain, but also by immaterial means. As in the time of the liberation struggle, magic would have rendered the militias undetectable, or would have made the bush paths confusing to the insurgents, forcing them to wander about the bush.47 The Portuguese expression used to describe this situation of magical entrapment was encurralado - herded, contained, trapped. 'There are informations', one post referred, 'according to which many veterans and militias closed off all possible exits of the insurgents!' Later, the thirty casualties were confirmed in other accounts. According to journalist Armando Nhantumbo, this was the foundational moment of the emergence of the Força Local: seeing Mueda under threat, the local authorities would have armed militias and war veterans with carbines and created a corps under the leadership of a former commander.48

Meanwhile, a group of insurgents, who had slept near the lowland village of Shitashi, called a meeting, rounded up all the young men who had not escaped, divided them in groups according to their religion and then gunned down over fifty, in what turned out to be the bloodiest massacre in the history of this Cabo Delgado war.49 The events were denounced by another voice note:

Big brother Vicente, now imagine: the bodies of those who were massacred in Shitashi, up until today, they are not being buried. They did a massacre yesterday, the bodies up till now are in the open… This is more… more… disastrous.50

In this circumstance of anxiety, insecurity and uncertainty, to boost the veracity of the information, people began to record phone conversations with friends or relatives and fed them raw to the social networks:

Respondent: 'I am your father, Mkeka.'

Caller: 'Mkeka?'

R: 'The little brother of Nyakula.'

C: 'Where are you? I am in Montepuez. Kalamalita told me that you are on the network.'

R: 'I am alive, but with sufferings.'

C: 'Thus, are you in the bush? Or did you go back?'

R: 'We didn't go back; they are in the district.'

C: 'Epah…They must be many!'

R: 'They are many! Lots of them!'

C: 'Eh-eh…'

R: 'They had two or three mortars, a couple of times they almost hit the helicopters.'51

[…]

C: 'Ai-ai. We are at the end.'

R: 'My wife got lost with my children, because one was strapped at her back.'

C: 'She doesn't have a phone?'

R: 'She does, but I think she lost it, running.'

C: 'Yes.'

R: 'I have two children: one boy, one girl. They bombarded me as well, even the backpack I had on my back burned.'

C: 'A shot?'

R: 'Yes a shot, father.'52

We must now pause to consider the slippery ethics of these sound artefacts. The clips were recorded and shared without the consent of the informants. While generally the speaker's name is edited out of the clip, names of relatives or acquaintances, or detail of place, make them theoretically identifiable.53 Sometimes the callers were distant relatives who had to identify themselves; often they pushed their interlocutors with pressing questions. And yet, the intentions may not have been nefarious. The ethics of 'informed consent' which has come to regulate institutional research is rooted in liberal contractualism; here, ideas of community and the urgency to share information prevailed.54

After having butchered fifty people in Shitashi, ransacked the district headquarters, proven once more their military capability, and humiliated the government by stepping onto the hallowed ground of the liberation struggle, the insurgents withdrew. In the aftermath of the attacks, a new genre - this time visual - emerged on the social networks: photographs taken by returning villagers to document the havoc of the aftermath. These images are all tragically alike: blackened walls, sagging roofs, carbonised interiors, piles of wrecked furniture. Only a few stand out from the dull monotony of destruction. On a bank wall, a message scribbled by the insurgents: 'The money is of Al-Shabaabe (Islamic government). Islamic State in the whole entire world.' [Figure 2] A video in which the wife of a former administrator, whose house was almost razed to the ground, walks among the rubble, pointing: 'Here was the kitchen. This was my bedroom.'55 In the most publicised image, which stirred a wave of grassroots Islamophobia in Makonde social networks, a man holds the head of a beheaded Christ in the ash-littered mission of Nangololo. [Figure 3]56

If suspicion against the army was rife before the attacks, it escalated afterwards. One much-shared declamatory voice note begged the president to admit defeat and call in external help to sort out the situation. Wearing a uniform was no longer a sign of trustworthiness, quite the contrary, as this other voice note made clear:

Between Litembo e Nimu, seven youths were surprised, walking toward the headquarter town [Mueda]. The population surprised them: 'Where are you going?'

'We are going to Mueda. We are soldiers.'

'Soldiers, ok. We know that soldiers go in a group. And the group uses vehicles to move from one place to the other. What about you?'

'They said: the vehicle is following behind. We'll catch them ahead.'

Sincerely. The populations did everything. They called the Mueda command. They ignored that. They said: 'We'll send soldiers to see this group, to check whether they are soldiers.' Sincerely, what does it cost to tell the populations: take care of these ones.

Nyusi's silence… Nyusi stained out ethnicity. The Makonde are respected. Three Makonde against twenty Mashangana. Against fifty… What is happening with us, here in the south: we are no longer respected. We lost all respect. Nyusi must know that he took away our power. […] We are not speaking because there is hatred. There is no hatred. It's the pain we are feeling. Fifty years will have to pass for Muidumbe to rise up.57

III. The owner of the phone, I have slit his throat

In the midst of the attacks of April, while the net was abuzz with grief, a strange voice note began to circulate. A man phones a relative and is answered by the insurgent who killed them. A lively exchange follows, in which the caller questions the receiver about the insurgents' motives. Reactions to the clip were incredulous. An insurgent willing to spend so much time debating politics and religion on the phone with the relative of a victim - this surely must be fake news, a piece of impromptu theatre concocted by irreverent youths indulging in gallows humour. A few insisted that the call was true. When the insurgents' violence abated, the attention shifted to more important matters - the burial of the dead, the reckoning of the damage, security.

When I listened to the clip, I - and the friends whom I consulted - concurred with the hypothesis of fabrication. This just seemed too implausible. Indeed, in a first version of this article, I engaged in an analysis of the clip in terms of a depiction of the ideology of the insurgents from the perspective of Makonde youths. Doubts began to emerge when, in the course of a 5-month fieldwork in the city of Pemba and the district of Metuge, I heard stories of family members of victims having conversations with insurgents, and even of insurgents calling from the victims' phones to taunt whomever responded. My field assistant swore to have heard one of these clips and to know personally the caller. In the last days of fieldwork I managed to interview one of the few survivors of the massacre at Shitashi. When I played the clip, the survivor unequivocally identified the caller as an acquaintance; and most importantly, the insurgent who responded as the person who harangued the captives at Shitashi before ordering their massacre.58 Rather than a practical joke, therefore, the sound clip turned out to be a case of reality outrunning imagination, as well as a chilling testimony of the insurgency from within.

The recorded phone conversation begins in an awkward Portuguese:

R: 'You. Where are you?'59

C: 'In am here in […] Now, I am asking about the owner of the phone.'

R: 'You am [sic] in […]. You are who?'

C: 'João.'

R: 'João. There, in […], what do you do?'

C: 'No, I stay right here.'

R: 'As what?

C: 'No, just… I am just a person.'

R: 'You aren't a soldier?'

C: 'No, no.'

R: 'So, speak Makhuwa, to converse well.'

C: 'Me, Makhuwa, I don't know.'

R: 'What about Makonde?'

C: 'Makonde, proper, I knows. I know.'

R: 'Ah. Speak, then.'

C: Switching to Shimakonde. 'Now, I am asking: the owner of this phone, where is he?'

R: Laughs. 'Thus? The owner of this phone, let me speak so: I slit his throat (ninshinda). Me, here, I am an Al-Shababe.'

This is a game of cat and mouse. The insurgent tries to ascertain whether the caller is a soldier. The caller tries to understand who is responding. The two strive to find a common language in which to communicate effectively. One of the reasons that had led me to disqualify the clip as a parody was the exceptionally calm reaction of the caller to the revelation - expressed in a jeering, flippant tone - that the responder is an insurgent who has murdered their family. Also, why would the caller record the conversation in the first place? The reason, I realised later, must be that the caller was prepared to the response by the several other calls happening at the time, and that he was in fact phoning with the intention of engaging in a confrontation and of creating a record of the interaction - an endeavour of knowledge production for the benefit of the social networks. Indeed, the dialogue comes across almost as an interview:

C: 'You slit his throat. What did he do wrong, for you to slit his throat?'

R: 'The reason why I slit his throat… Us… Me, I want Islam. Now, if I find a person, if I ask him: "Are you a Muslim?" "I am not Muslim, I am a Christian." Or perhaps: "I am heathen." I see him, that man is bad, doesn't know himself. Like, I am born, I come into this world, God gives it to me, but (sambi), but (kanji),60 he sits like… like meat, like a beast (inyama), thus. Now, such a person, if I find him, I slit his throat. A person needs to know oneself. Where he comes from, where he goes.'

C: 'Ah? Thus?'

R: 'Eeeh. Now, a man just sits, doesn't know himself, what-what. If I find him thus, I slit his throat - directly.'61

We have here one of the very few documents in which the insurgents - in this case, presumably, a leader - articulate their claims in an audible manner.62 The theological point is clear: the status of nonbeliever to Islam, of not having a direction in life, is tantamount to being a beast (inyama) to be slaughtered. The insurgent's tone is drawling, a sign perhaps that he is under the effect of some drug.63 Some jeering can be heard in the background. The final pun expresses the youthful cruelty of someone who revels in murder.

The caller moves to more practical terrain, prompting the insurgent to reveal their plans:

C: 'Now, you, where are you now?'

R: 'Me? In Namakande. You - didn't you hear yesterday, about the war (vita), the war (ing'ondo) in Namakande?'64

C: 'Hear, I hear, but I ask, to know. Now, from Namakande, you people, where will you go?'

R: 'To Mu-e-da.'

C: 'In Mueda, what do you aim to do?'

R: 'Bah! Unbelief (ukafiri), unbelief, I spurn it. I spurn unbelief. There, I want to get the head of Chipande, or perhaps Ardimu, or perhaps who… I'll kill him and I'll go home to Palma or wherever, where I come from.'

C: 'You are looking for Chipande or Lidimu, to kill them?'

R: 'Eeh, even Nyusi!'

C: 'Even Nyusi, you want him, to kill him.'

R: 'Eeh!'

C: 'Now, Nyusi, what did he do wrong?'

R: 'Is he a Muslim?'

C: 'You guys, you are doing things without meaning, really.'

R: 'About Nyusi, it's like this. You, my friend, you see that what we are doing is meaningless. But you, with your money, you buy a car, you drive on the road. But if government people get you, you must take out your money and give them, or what, so that they give you papers. In the law of Islam it's not like this. You went with your wife to the fields, worked, for five years, bought your car, went around with your car, they annoy you: is this lawful (ishariya)? But you have gotten used to unbelief.'

The practical objective is a literal decapitation of the current Mozambican leadership, especially its Makonde representatives: generals Chipande and Lidimu (mangled as 'Ardimu'), and president Nyusi. The argument is that this leadership is oppressing the people through unnecessary taxation and arbitrary abuses. This rejection of the State authority - and more specifically of the violence of the Mozambican State - was already articulated in Bonomar's speech at Mocímboa. The key signifier that allows the articulation between the political and theological realm is the Kiswahili word ukafiri - unbelief - which sinks its roots in the history of the slave trade and echoes a sore note with the Makonde.65

Then follows the obvious question: why killing innocents to topple a political system?

R: 'If you voted Nyusi! Who put him in power, it's you.'

C: 'And this is why you go around killing common people…'

R: 'Eeeh… We're gonna kill you, end you all, until you believe in Islam. And we're going to be together. And when we are together, we will leave each other be. And these days, we are leaving you, really, we only want - what? - soldiers. Those spread unbelief a lot.'

[…]

C: [sarcastically] 'In Shitashi you didn't kill common people: you killed government people.'

R: 'They are supporting Nyusi's programme. Those whom we killed yesterday, we asked them: "You, what are you?" "We don't know Christ, we don't know what-what. We are heathens." Now, a heathen person, what is it? A person without religion, what is it? That is to live like a beast (inyama). Rather a beast: you slaughter it, eat it, you fill up.'

[…]

C: 'You want to kill Nyusi?

R: 'If we kill him, you're going to be ours, you won't elect him anymore. My friend, you will get peace. You will till the land, will get each thing. You'll get work.'

C: 'Now, you want to kill Nyusi. Don't you know where Nyusi sits? Now where you do the war, is this where Nyusi is?'

R: Laughs. 'We will get there. To Maputo? Without problem. First, you supported him. You elected him. You put him in power. What-what. But first, true, we will wipe you out. So that you don't elect him again.'

The insurgent's response revolves around two points. First, civilians are responsible for having voted Nyusi, in particular in Cabo Delgado. Therefore, murdering civilians is a way of undercutting the leadership. But political and moral corruption are closely related. Both civilians and their leaders are unbelievers - some Christians, other heathens66 - and as such they are like beasts undeserving to live. The threat of devastation - embodied in the grotesque image of Nyusi's beheading and in the promise of a war that will spread until the capital - is mitigated by the Arcadian promise of a future in which everyone will live in peace, return to the land, work, get all they need.67

When the caller suggests that the levels of violence of this war are not comparable with the two previous ones, the insurgent is swift in calling out the hypocrisy:

R: 'You, don't be naughty. Beginning with the colonial war. You did it, you wiped out [people], until nowadays you are receiving money. Those who survived aren't receiving money? And people are looking after each other, those who are left.'

C: 'Now, the way you're doing, is someone going to be left?'

R: Laughs. 'Here, my friend. There is much history. Many people have been killed. In Mueda, where, where. Why are there still people there?'

R: 'The old wars are different from the one you are doing. You go around putting houses on fire… There won't be any people left: you are murdering them all. Like yesterday in Shitashi…'

R: 'You are not fooling anybody. We have seen the wars: of Renamo, of who. Thus, thus. Setting fire to the houses, destroying, thus, thus, each thing. Cars, what. Eh? Who do you think you're fooling?'

If one may wonder what kept a bereaved person in a verbal exchange with a murderer for twelve minutes, the inverse is also puzzling. What made this insurgent dialogue, in a rather courteous manner, with someone whom he considers a political enemy and akin to a beast? The caller has the courage to put the question straight:

C: 'Now, you, what benefit do you get, you snatch peoples' phones, if they call, you talk… Are these actions of yours meaningful? Why do you do this?

R: 'Shè. Don't be naughty. What is this? We overpowered you (tundikuulula)!'

C: 'Aah. You overpowered us.'

R: 'Eeh. What else?'

This juncture lays bare the politico-religious fault line that underwrites the conversation: between the Christian Makonde, who have put in power Nyusi, and a system of corrupt government; and the Muslim Mwani, who have been oppressed in the colonial and postcolonial dispensations and who now come to take their revenge by 'overpowering' their rivals.68 Thus, at a moment in which people were wondering about the motives of the 'faceless enemy', this voice note, recorded by a daring person who acted almost as an investigative journalist, exposes the tensions and ideology underpinning the dire violence unleashed in the attacks against the Makonde plateau.

Towards the end, another important point emerges: the resentment towards the ruthless repression of the insurgency in its initial phase:

R: Now, a little bit, should he [Nyusi] let go of our people - he arrested many of them - perhaps, should he release them, a little biiit [padiiki, in a high-pitched voice] we will give you a truce. A little biiit! He arrested many people without reason. What did he arrest them for? Only because they are Muslim.'

C: 'He arrested many people without reason, Nyusi?'

R: 'Eeh. He arrested many; others he killed without reason. Since the beginning. You must know, in Mocímboa, in Mucojo, in Macomia, whereever, the Shababe were killed and imprisoned. Do you know? Without reason. Without reason (bila sababu).'

When the caller retorts that the people imprisoned had murdered and burned, the insurgent sneers:

R: 'You, there's nothing you know, because you're really a Christian. Now, I need to get your neck.'

C: 'Get my own neck?'

R: 'Eeeh. If I get it…'

At this point, the caller's nerve fails him and he puts the phone down.

IV. The battle for Awashi

The village of Awassi - also rendered as Auasse or even Oasse, whose correct name in Shimakonde is kuna-Awashi - sits at the T-junction where the national road N380 coming from Pemba bifurcates, climbing to Mueda on the one side and heading to the sea and Mocímboa da Praia on the other. The tarred stretch connecting the two towns used to be one of the smoothest in the province. Awashi is part of a series of villages in which Makonde and Mwani used to mingle, both a friction and a dialogue zone. It also constitutes an ecological threshold between the grasslands in the hinterland of Mocímboa, the thick forests surrounding the Makonde plateau, and the drier coastal areas. It used to be a somnolent spot, known to the travellers because one could often find for sale ming'oko, a wild tuber that people ate in times of famine.

The crossroad acquired an obvious strategic importance, because it allowed the control of transit from Mueda to Mocímboa, as well as of the stretch leading south to Macomia. The police station of Awashi was also the very first objective of the insurgents' attack, in the night of 4 October 2017, one day before Mocímboa came under fire, in what was held by some to be merely a robbery. In May 2020, only weeks before the attack to Mocímboa, the insurgents occupied the crossroads and in the process stole an armoured vehicle from the Mozambican army, an action which they publicised through two videos.69 In the aftermath of the conquest of Mocimboa, they held the position as a defensive bulwark and deactivated the power station that fed Mueda, leaving the main military headquarters of the north in the dark.

Awashi was also the site of one of the most harrowing moral crises surrounding the Mozambican army. In September 2020, a video circulated on social media showing five young men dressed with the uniform of the Mozambican army cruelly whipping a naked woman along a road, eventually riddling her with 36 bullets.70 'We killed an Al-Shabab', one of the executioners commented, while the one who shot the film turned the phone towards his face, making the sign of victory.71 This was the sixth video leaked in the space of a few weeks showing army brutality against suspected insurgents - and the most harrowing, because the violence was directed against a harmless civilian. Immediately, the internet was abuzz with astonishment and grief. Two versions of the circumstances of the shooting emerged. According to the one, the woman was a 'witch' - hence the nakedness - who was caught reconnoitering for the insurgents. According to another, she was a peasant who, unable to flee the war zones, was found with her son gathering wood; the son was bludgeoned to death and the mother raped and murdered. The Facebook profile of the soldier who carried out the deed was identified, and it soon filled up with comments, both of insult and of celebration. Two days later, the family announced that the soldier had fallen in combat, leading to speculation that he was executed for leaking the video. Pressured by Amnesty International to institute an inquiry into the matter, the Mozambican government resorted to notions of 'flag operation' and 'deep fake'. The woman was never identified.

We do not know whether the incident of the naked mother - possibly a Makonde, coming from a predominantly Makonde village - had any role in prompting a military operation against Awashi led by war veterans from Mueda; or whether the considerations were merely tactical. Be that as it may, on 16 October a string of Facebook posts triumphantly announced the retaking of the crossroads with an astonishing figure of 270 insurgent casualties. 'The men who faced the insurgents', one voice note commented, 'were the much-scorned war veterans, the ancient guerrillas of the Front for the Liberation of Mozambique, who are in the reserve. Awashi is ours. Awashi is our land. We are about to take back Mocímboa and other places where these scoundrels are burning and killing. Long live the war veterans!'72 Several posts referred to the magic powers marshalled by the veterans to surprise the insurgents in their sleep.

As it turned out, the sole hard evidence to support this extraordinary news was a four-minute audio clip, shared across multiple platforms, in which the war veterans celebrated the victory in its immediate aftermath. This time, the audio clip was not a phone call, but the recording of an in-person conversation, taking place in a crowded place. Noises of partying can be heard in the background. The first speaker has a Makhuwa or Yao accent:73

C: 'Brother-in-law, how many did you slaughter there?'74

R1: 'There? Two-hundred and seventy.'

C: 'And their equipment, in terms of weapons, did you not take anything?'

R1: 'It's in the car. They are bringing it, uniforms, everything. Because another company of soldiers stayed there. You know what? Five trucks of soldiers; us, two trucks - all came back clean! Clean! […] We blocked the path of Shinda. […] We cut through the bush-bushes. We surrounded them badly. From Mbau. And from Nangade: cut them out. Where. Where. Where. You see?'

C: 'You slaughtered the guys.'

R1: 'Cartridge holder - Toma! Take! Take! And those soldiers whom we know, they said: Here came the war veterans. […] Those are only dangerous in name.'

C: 'This is what I always said. It's only the name. Those are nothing. They are nothing.'

R1: 'Brother-in-law. They are nothing. And us - much fucked! Even the soldiers bowed before us. "You? We respect you."'

C: 'These same soldiers who beat us up with sjamboks?'

R1: 'Hehe. They say there was a party yesterday at the headquarters.'

C: 'But did you not manage to put in the pocket something… For there was time…'

R1: 'There was no time. MIGs above. Helicopters above.'

After the first speaker trails off with a story about a piece of a motorbike he kept as a memento, the interviewer approaches another man, whom he refers to as big brother (kaka) and who speaks with a distinct Shimakonde accent and a veteran's recognisable tone of self-importance:75

C: 'Big brother! Good day. Congratulations. Congratulations.'

R2: 'We are congratulated, all of us. It's not only me. But electricity, forget about it. They burned all that stuff. They did a terrible damage.'

C: 'This new equipment.'

R2: 'They were celebrating some party there, perhaps a wedding or what, there by the mango trees. Here you have the soldiers' barracks and there the hospital. Here by the mangoes, by the market, there were cans, maybe beer, it was full of bottles. Right there, our fire broke off, pwii! Some just fell - tim! Shè, their job was just to climb up like monkeys. It's true, a good work was done. All the boys came home safe; the one whom you heard, got wounded, he shot himself […] but it's nothing serious. They are nothing, those; they didn't have time to shoot anybody, my friend. They tried to react a bit in that area of the petrol station. The last gunfire was right there - ki! It's as if God guided us. And then silence, heee… The boys partied, the soldiers partied yesterday. "They were wiping us out, why with you elders we are coming back fine?" Until now I feel for them. And me: "No, you are dads, we are the grandaddies." Eh.'

What made the audio clip a reliable piece of information were contextual, indexical and paratactical elements. Truth was the stuff of sound and voice. People call each other by name and offer drinks: 'Finish this up. Here's a reinforcement. Come on! Soda here!' The testimonies, especially the second, are interrupted by laughter. Even the hesitations, the errors and the exaggerations - not to speak of the mischievous reference to the soldiers' sjamboks - add to the sense of spontaneity. One can feel almost physically the exhaustion and the exhilaration. To forge such a recording would have required an astounding level of technical and performative skill, a deception more difficult to believe in than the authenticity of the clip.

When the news of the attack appeared in the mainstream media, however, they were met with incredulity. One newspaper described the operation as a 'joint patrol' of the military and the militias, which 'stumbled upon' an encampment of insurgents and called in helicopter fire to exterminate them all in their nest.76 The influential independent online gazette Cabo Ligado, which since May 2020 was shaping international opinion about the conflict, dismissed the news as, 'if not a fabrication, then at least a substantial overstatement of what actually took place'.77 Cabo Ligado did not discuss - and probably did not have access to - the sound clip that was the direct source of evidence. President Nyusi did not acknowledge the operation in his overview of governmental responses at the time - but then, doing so would have raised questions about the legal statute of the paramilitary group.78 The head of the Rapid Intervention Unit (UIR), Francisco Quiasse Madiquida, however, mentioned the Awashi operation in an incendiary speech made to shame young recruits of the police academy, which circulated as a sound clip and elicited many responses:79

As we are speaking, now, war veterans are retaking Awasse; they already retook Dyaka. Until when will we be using old people - and you youngsters, doing what? These are people with walking sticks who are today entering in Awashi. Because our youth simply looks away. What future will you have in this country? You do not understand the meaning of sacrifice.80

A few days later, the scan of a letter written in Shimakonde circulated on social media [Figure 4]. The letter was signed by one Maiti - 'corpse' - ostensibly a member of the local association of the war veterans (ACLLN), and directed at the Mozambican criminal police (SERNIC).81 The letter refers to Naveta, a septuagenary war veteran, as the commander of the Awashi operation. Indeed, Naveta was later acknowledged as the leader of the militias in Mueda and Muidumbe, before that role was taken by John Issa Mwalu. The tone and the writing are consistent, but there is no contextual element to decide on the document's authenticity. Whether real or a fabrication, the letter exudes the pride of a generation that fought three wars and the nostalgia for a fading order:82

Elder of the SERNIC of the Province of Cabo Delgado

The last Friday, date of 16th of October of 2020, the soldiers of the government guided by the war veterans who liberated our country, went to Awassi and infiltrated the enemy and killed a group of 270 people. Those who went circled from three fronts: Awassi - village Shinda; Awassi - Mitope; and Diaca - Awassi. The soldiers and other groups were led by the old commander, whose name is Naveta. The tradition is alive. Before engaging the enemy, they had to prepare a medicine, so that, on their arrival, they would find them all sleeping. They brought weapons and killed them. While I speak, the soldiers and the elders who liberated the country are in a meeting (at the palace) at the ACCLN.

Mueda, 19.10.2020

Maiti

V. A militiaman's odyssey

Whether the victory at Awashi was real, fictive, or just exaggerated, the enthusiasm lasted little. On the night of 30 October, several cars and motorcycles blasted through the crossroads, heading to Shitunda, the lowland village which offers the easiest access route to the Makonde plateau. The onslaught was temporarily stemmed, again, by the local militias. In a harrowing 16-minute audio clip, a militiaman tells the story of the defeat at the phone to a relative. This is a precious document to understand the nature of relationships between the army and the budding Força Local in a dramatic conjuncture of the war. There is no reason to doubt the tale's authenticity, sprinkled as it is with detail of place and names of people and punctuated by the interlocutor's exclamations of dismay. It would take more than a consummate actor to replicate the despondent tone and the speech rhythms, whose roots sink deep into local modes of storytelling:

On Friday we had organised to go to Shitunda. There were comrades from Mwambula, others from Vintequatro, us from Nshinga, others from Shitunda… We did a selection, a fine group. Truly, we went down until Shitunda. And there we slept. About midnight, we heard a car buzzing. People began to wake up: 'Boys, boys, boys. Here's our task coming: a car is coming in.' We kept on alert. That's it, the car arrived - a good ambush, big brother. They fell nicely into the ambush - gwé! We let the barrels loose. Ntutu! Fire! Until the car sideslipped. Fell to pieces. And it was loaded of people. Loaded, big brother. I think that they were going in the direction of Nawadimu. This is something true. The car came from Awashi. […]

That's it, truly, we lay down again. We hear another one, coming, buzzing. Us: 'Eh? Another one entering.' The car came, fell into the ambush. We shot, it collapsed right there. And we knew: the hunt today is going well. But now, the ammunition finished all. What to do? Know how to outflank, to do what? See if we could take what they carried in the car. Their weapons. We crept up in the road, circled around; as we got their weapons, we hear another car coming. Eh. All the ammunition was finished. Now, from there, we didn't go back. We stood behind the car. For we were blocking the road to Rwarwa and the one that goes to Shitashi. When we heard the other car coming, because the ammunition was over, we stood behind the car. And when that other car arrived, it stopped right there. Bo! For they knew: 'Who shot, it's from that car.' They knew. Soon enough, another motorbike arrived. And they started to shoot. All our ammunitions had finished. Among us militiaman, there wasn't a single person with ammo. All the ammunition was with the soldiers, who had fled long before. […]

Now, all the soldiers had left long before, they'd escaped, throwing their equipment away. True. Us: 'What should we do? Those, as they ran away, they dropped lots of stuff. We must follow where they passed.' And we tried our best to follow where the soldiers had passed. We managed to pick up a belt, a cartridge, a full magazine. They had thrown it all away. Two hundred and fifty bullets. We picked it up. We followed their tracks; found weapons they'd thrown away. We picked them up. They were shedding stuff as they went, throwing away stuff, because if they met the enemy they would be killed on account of those very things. Truly, we carried on, managed to catch up with some of them. We found some of them. Go go go; go go go… We caught up with some more. We got them, that's it. Go go go… Our group found four soldiers. We carried on, found a place to rest. We rested, until morning. Our friends, with whom we had parted, followed other soldiers and caught up with more of them.

We slept; at three in the morning, we hear, in Magaia: beh! Bazooka. And again: bazooka in Magaia. And us: 'Mhh. In Magaia, it looks like things are turning to the worst.' We had with us an elder from Mwambula, who was in great pain, could not even walk. So we had to stop and wait for him. Wait for him a little bit, wait for him a little bit; walk, walk, walk. Until, further down - bazooka in Nshinga. And us: bah! In Nshinga, we left some soldiers. Are they the ones who make confusion? And again - bazooka in Nshinga. And then AK-47s. And us: 'Mh. In Nshinga, today there's war. They entered.' Now there, the sick one, the elder, got worse, this got the best of him. We were just distraught. And me, I got enraged. My home, I just left it; my elder, I just left it. Eh. And all ammunition had finished. So we though to look after our lives. I needed to get home.83

The group tried to drag along the sick comrade, until one by one elderly people fell sick. They managed to reach the plateau - it is a steep climb through thick bushes - at midday, only to find it aflame with war:

Now we heard shooting at Namakande, in the locality. And there they had already invaded; everywhere, they were shooting. In the district, everywhere. And us: 'Wé! How should we do? Let's wait for the day to fall and get to Nshinga.' And as we did so, when the sun was beginning to set, we entered the village, this side, we looked for the adjunct commander. When we asked for ammunition, he said: 'I don't have ammo.' 'Thus?' 'Eeeh… Each person must get a little bit.' Each one got thirty bullets and a magazine. One, one, one. 'At least we got something.' The people from Mwambula went home, to look after at the situation there. Mwatidi and Namakule, and even Mandava, Vintequatro, Nshinga: everywhere was overrun. In Nang'unde they just came to do confusion, set the houses on fire, what-what.

We hunted-hunted them, from house to house, slip here and slip there, hit and run. True. Now my head started to ache and I got a fever. I told the chief: 'My body is battered. I want to go home and look for my family. My wife and mother.'

And he: 'Go look for them. The work, is what you did. And since you are worn out, because of climbing the mountain… There is no problem. I will release you. Go look for your family.'

And I asked: 'The weapon, should I leave it with you?'

And he: 'This weapon, because you have to go from village to village, don't leave it with me. If you meet them, this will be your defence.'

Truly, I went out with my weapon. I passed beside the hamlet, there, until the abandoned homestead, until the house of our friend Simba; I jumped the path to Nang'unde, arrived in Mangala. In Mangala, I did not find them. I came this way, kuna-Ng'avang'a, and finally found them. And I am here, all my body battered… That's it.84

There is something utterly tragic in this tale of fleeting victory, followed by disarray and defeat. The enthusiasm for the well-succeeded 'hunt' is immediately snuffed by unsurmountable practical obstacles: the soldiers' defection, the enemy's superior forces, the lack of ammunition, the elderliness of the combatants. The image of the militiamen following the tracks of soldiers to pick up the equipment they shed, hoping to pass as civilians to avoid slaughter, is an icon of abandonment. The clip also sheds light on the forms of organisation established by the Força Local, building on practices and chains of command inherited from the times of the liberation struggle, but also on older modalities based on trust and understanding.85

The successful ambush at Shitunda and the precipitous flight of the soldiers translated into yet another tangle of stealth and spectacular violence. The story was conveyed by another voice note, short and somewhat muddled. While the militias crawled back to the plateau, the bodies of the insurgents killed in Shitunda were carried to Namakande by a contingent of soldiers and put in display against the wall of the administration. Possibly picking up the uniforms shed by the soldiers in flight, a group of insurgents ambushed the soldiers who were handling their fallen comrades:

C: 'You really worked hard in Shitunda. You did the guys in.'

R: 'We did them in, truly! In the morning, thus, they transported them, carried them, laid them out. They put them out, in Muidumbe. In lines. On that big wall. On the side of that big wall. Right by the administration, they arranged them in lines, thus: da da da da. But now, those soldiers - there were some who had come with us, so when they began to shoot, we thought, perhaps it's the soldiers. But they were the same mashababe.'86

VI. The road to Mueda

The insurgents soon routed the soldiers stationed at Namakande. Once more, the people of Muidumbe took to the bush. As six months before, the flurry of voice notes from the war zones resumed, only this time straight from the people affected. 'They entered now, not an hour ago', a young man reported, 'not even an hour. If you call the people in Nang'unde they will be able to tell you well. I went to help them today…'87 Even more self-consciously, people took to phoning locals in the double capacity of concerned relatives and grassroots journalists. Not only voice, but sound is invoked as proof of presence and reliability:88

C: 'In Mwatidi, you only hear them? Are they there?'

R: 'They are!'

C: 'Gwé!'

R: 'We are in the middle, everywhere we hear weapons, surrounding us. Can you hear?'

C: 'I can hear.'

R: 'This [sound] now they started again.'

C: 'But are you drinking water?'

R: 'Drinking water - I tell you, since yesterday, at six, I haven't drunk, I haven't eaten mealie-meal.'

C: 'All people are in the bushes.'

R: 'All in the bushes. Full of them.'

C: 'And they are hunting you?'

R: 'In the houses? Booo…'89

The November attack would turn out to be very different from the April one. No attempt was made to address or convert anybody. Violence was not only unleashed against the army, government infrastructure, commercial establishments and the houses of local notables, but against common people. The distinction between civilian and military was erased: because of the resistance of the Força Local, anyone in Muidumbe was a potential enemy. It is also possible that the insurgents were more significantly influenced by the apocalyptic vision of the Islamic State, adopted by some of its leaders, according to which only after a phase of annihilation and 'savagery' the caliphate can be established.90 The government responded via air-fire from their mercenary force, the Dyck group, whose helicopters shot indiscriminately on village houses and against anything that moved:

R: 'I don't know whether your house exists. Helicopters, here. Two of them.' […]

C: 'Who do they attack, these helicopters?'

R: 'Who they attack, I don't know.'

C: 'But these helicopters, shoot.'

R: 'Helicopters. They don't have a way to get out from below. They surrounded the guys.'

C: 'And on the side?'

R: 'Everywhere they're surrounded: Namakule, Nshinga, Mandava, everywhere, they surrounded them.'

C: 'Weee.'

R: 'They, like an exit, they don't have an exit […] We see the helicopters shooting. We are here in Mandava, on the hill, at the abandoned homestead, and we see the helicopters shooting.'

C: 'You can see.'

R: 'I can see it, and they are shooting out of control.'

C: 'Do they shoot with small weapons or big ones?'

R: 'The helicopters are shooting with big weapons, not guns. Big weapons! […] They are shooting with bazookas. They shot them at the crossroads, wounded some, but they escaped. Because the bulk is at the crossroads. We are in war. We don't eat, nothing. Bare people. Thus: a trouble. The helicopters are shooting so hard you can hear it at the phone. If you don't hear it's only because of the wind. They were shooting in Mwatidi. Now they have flipped the LP and are shooting in Mwambula.'

C: 'I can hear a bit… Sounds like wind-wind.'

R: 'The helicopters are two and are shooting outside of the law.'91

As in April, hopes soared that through their superior knowledge of terrain, occult powers and aerial firepower support, the Força Local could 'fence in' the insurgents:

They blocked them everywhere, the war veterans and the soldiers, blocked them everywhere. Now the ones who are in Mwatidi, can't come out; the ones in Mwambula, don't come out: they don't know where to turn. On the path that goes at kuna-Ngoma, they shot at them terribly in the morning. […] They don't know where to look, they are hunted down. They come out sorcerously, but do not come out in the open, no. They are in the bush. All paths are blocked.92

Like the one at Shitunda, these barrages did not hold. The insurgents broke free and occupied the entirety of the plateau area of Muidumbe. Violence against civilians escalated. One alarmed voice note alerted: 'Elder, my big brother, people are being slaughtered in Nshinga; people are dying; many people beheaded in Nshinga. People are being beheaded in Nshinga, they are hunted in the bush.'93 Other messages of distress sent to family members were circulated as well, like the one of a woman who managed to connect to the network on her escape route and called her son, telling him that she would try to walk to Mueda. The mother breaks into tears: 'I won't make it, my son. They are hunting us.'94 A few people managed to send short videos from the bushes where they were hiding. A young man films himself, saying: 'We are in the bushes, without knowing what we did wrong. For the government, I don't know, our leaders who are before us. Three days in the bush. We are doing badly. Without food, we are eating green mangoes, which don't amount to…' Another one frames the people with their impromptu plastic buckets and plates, concealed in the thick foliage, trying to prepare some food; and then breaks into a sad, nervous, bitter, jeering laughter.

In this conjuncture, the news broke that the soccer field of Mwatidi was turned into a macabre killing field, in which the insurgents brought everyone whom they apprehended in the bush to be beheaded. The massacre was first announced by the grassroots outlet Pinnacle News, based on a voice note and follow up inquiries, none of which were ever made public.95 The shocking news was soon reprised by national96 and then international media - including Al-Jazeera - provoking a global wave of consternation, from Black Lives Matters activists to the UN general secretary.97 The government denied the existence of any massacre after the one at Shitashi.98 Pinnacle News published a series of photographs of beheaded women, mass graves and butchered babies, which, like the ones from Mbau, turned out to come from the northern Kivu. Besides one article from a Portuguese newspaper, which referred to independent research, the massacre at Mwatidi was never confirmed, even though many people were slaughtered and beheaded, their bodies left in the open to be eaten by stray dogs.99

By 5 November, the only bulwark against a march of the insurgents towards Mueda - the military headquarters in the north - was a military garrison stationed at Miteda, the last village of Muidumbe. On the 11th, alarming reports circulated according to which Matambalale, the village before Miteda, had been taken over:

C: 'Uncle (njomba).

R: 'Uncle. Wé uncle, they are destroying, there, today - Matambalale.'

C: 'Booo! […] They are destroying Matambalale… But in Matambalale, don't the soldiers stay right there?'

R: 'Where, uncle? The soldiers fled, they left behind even their weapons! Leave behind! Now, that in this war, the soldiers flee, this is what hurts me!'

C: 'That's it, uncle, they are almost in Mueda.'100

But the disruptions in Matambalale turned out to be a pillage from the Mozambican army:

I spoke with one friend of mine, in Matambalale. He spoke thus: 'In Matambalale they didn't enter. But in Matambalale, there is confusion of the soldiers. The soldiers are breaking into the houses, hoarding stuff and taking it to Mueda. They came today, broke in, took stuff, stole. They ate pigs; everything that the people left, they are stealing. And if someone tries to go back [to the village] to try and take something, they will whack them with their sjamboks and leave him for dead - jojolo!'101

My elder Lishoka. He called his family in Matambalale. Thus: 'How are things in Matambalale? We hear that they have entered, they are shooting?' And Lishoka heard that it's a lie: 'Shà! It's not them who entered. Who are responsible are the soldiers. Thus, the people fled to the mountains. Some houses were left unattended. The owners are not there. And the soldiers see, this house is worthy; that's it, they break the door, take what they like, and not to be discovered throw a bomb in. It's the soldiers who did such a thing. […] It's not the mashababe; it's the soldiers of the government. Yesterday they stole what they wanted: pigs, goats; slaughtered, cooked and ate'. And Lishoka said: 'Well, keep strong. The soldiers are not to be trusted.'102

The sacking of Matambalale was the last straw in the already tense relationships between the people and the army. Increasingly, emphatic calls were made for president Nyusi to demission.103 Meanwhile, Mueda was shaken by a wave of panic after several people received an sms warning them of an imminent insurgent attack. People flocked to the bus stations, buying tickets at triple the price for the town of Montepuez. Videos and photos circulating on social media capture the frenzy: trucks topped by piles of mattresses, families crowding under trees with all their belongings, the main road of Mueda turned into a trampoline for a mass exodus.104 'People don't trust anymore Cabo Delgado,' comments the person who films one video from the comfort of a car. 'There are people here who lost relatives. This is sad.' And his companion, a southerner: 'They say that the Makonde are touch [in English] for war, but where are those Makonde? They are leaving town. They surrendered. This war is terrible.' No images came from Muidumbe, still under insurgent control, except for a handful of photographs of the charred roof of the mission of Nangololo, brought by operators of the radio station after a two-week odyssey by foot through the war-torn forests.

VII. Of oranges and high waters

Unlike the other magical fences, the barrage at Miteda held, and the insurgents never attacked the town of Mueda. Muidumbe, though - the 'heart of the Makonde' - would remain under insurgent control for months, despite a fragile reoccupation of the district headquarters by the army. Tens of thousands of people swelled the ranks of the internally displaced. The situation began to change only in March 2021, when after the attack to Palma, near the liquified gas installations, the Rwandan army was called in.105 Even so, the resettlement of the villages on the south-eastern edge of the plateau was precarious; and today still, the area remains one of the most unstable of the province. The onslaught against Muidumbe had two crucial consequences on the landscape of war in Cabo Delgado: the consolidation of the Força Local as a major actor; and a growing anti-Frelimo disaffection among the Makonde, once the party's staunchest supporters.106

Media language also transformed together with the war. The use of the voice note declined precipitously. With the evacuation of the majority of Muidumbe's residents, nobody was really there to provide the news. Also, a turn of the screw in Mozambique's terrorism and media legislation made people more aware of what to share and with whom. It is probable that surveillance extended to the grassroots level. The voice note was therefore something like a 'vanishing mediator' that accompanied the moment of destruction of a social landscape.107

Still, people kept entrusting their thoughts or feelings to the fleeing matter of digital media, throwing messages-in-the-bottle into the great sea of social networks. An old man stands by a hut. He is dressed in a thick jacket and looks with watery eyes at the person who films him, declaiming: