Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Kronos

On-line version ISSN 2309-9585

Print version ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.27 n.1 Cape Town 2001

Photography and the performance of History

Elizabeth Edwards

Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford

Iwant to start with two quotes, from two very different historians whose work I admire greatly and which form a sub-text to this article.* First Elizabeth Tonkin quoting and paraphrasing Karen Barber:

To understand oriki^[a form of Yoruba praise chant] ... you have to see them as a very specific, intense and heightened form of dialogue, in which the silent partner is as crucial as the speaker [for our contexts here read viewer] ... it is clear that the dramatic communication of oriki chants [here read photograph] is at the heart of very far-reaching processes of social action ... In engaging in this action [it is] reactivating the encoded past for a present purpose.1

Then Greg Dening:

I think that we never know the truth by being told it. We have to experience it in some way. That is the abiding grace of history. It is in the theatre that we know the truth ... truth is always there but in some other form than we might expect ... sometimes uncertainly, sometimes contradictorily, sometimes clouded by the forces that drive us to it, sometimes so clearly that it blinds us to anything else.2

I want to consider a particular role of photographs in inscribing, constituting and suggesting pasts. The basic question which has informed all my work recently is: what kind of history are photographs? What is the affective tone through which they project the past into the present? How can their apparently trivial incidental appearance of surface be meaningful in historical terms? How does one unlock the 'special heuristic potential' of the condensed evidence in photographs representing as they do intersections? Egmonde and Mason have recently described these intersections as 'cross roads of morphological chains, as the intersection of numerous contexts and actions, or at the nodal point where both contemporary and modern preoccupations reflect and enhance each other'.3 Do photographs have their own agency within this? If there are performative qualities in photographs, where do they lie? In the thing itself? In its making? In its content? I can only chip away at one corner of these questions. I want to move beyond the surface level evidence of appearance so that 'if it can be recognised that histories are cultural projects, embodying interests and narrative styles, the preoccupation with the transcendent reality of archives and documents should give way to dispute about forms of argument and interpretation'.4 This must be seen as experimental, a heuristic device to enable a bit of historiographical exploration, for photographs are a major historical form for the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, yet we have hardly started to grasp what they are about, how to deal with their rawness, in both senses of the word - the unprocessed and perhaps the sometimes painful.

A few preliminaries. I am taking 'colonial' as implicit here, but my argument has wider implications. It is simply more intense, perhaps, in its colonial moments, but not exclusively so. Some may label the photographs I am considering as anthropological. Certainly they have been at some time or still are anthropological, but I prefer to call it history, with a small 'H' (both the thing itself and what we do to it), for to liberate images from such categorisations is the first step to articulating alternative histories through them.

My argument here centres around some photographs from the Pacific in the late nineteenth century. These few Pacific images are ones with which I have been working lately and were instrumental in my thinking here. Consequently they are not merely illustrative but a central and formative part of my argument as they set me thinking in the first place.

I have argued on a number of occasions, as have others, the parallels between oral history and visual history - photographs. For the sake of argument I am going to concretise this connection by taking a model from oral history, especially that articulated by Elizabeth Tonkin, whom I quoted at the beginning. This model is that of genre, expectancy and performance.5 It is not a model that can necessarily be downloaded to photographs exactly, but the shape is useful to think with in relation to photographs. Genre and expectancy will resonate through this paper. Expectancy of the medium might be glossed here as how we expect photographs, with their beguiling realism, to tell us about the past in given performative or interpretative spaces and with their various audiences. Genres, visual dialects of style, form, intentions, uses, rhetorical strategies carry an expectation and assumption on the appropriateness of performance.

However, as my title suggests, it is the last characteristic, performance, on which I intend to concentrate here, exploring the ways in which photographs could be thought to have performative qualities, both literally and metaphorically. I want to push this idea to see how far it will lead us in an historiographical liberation if, as a heuristic device, we allow photographs a certain activity in the making of history. I hope the examples I use will perform what I want to discuss to some extent. At first glance they are rather ordinary photographs, but I hope to nudge them into action.

First, one should consider briefly the nature of the medium itself for this is inseparable from the genres, expectancy and performance in which it is entangled. In its stillness, deathlike as some commentators have argued, it contains within its frame, fracturing time, space and thus event, causing a separation from the flow of life, from narrative, from social production, In making detail, it subordinates the whole to the part. It is indiscriminate, fortuitous in its inscription, random in its inclusiveness. From this configuration emerge the inherently unstable signifiers in the image. Central to this are stillness and frame for they are sites of semiotic energy and thus mutability of meaning.

Among the five characteristics of the photograph defined by John Szarkowski in his famous catalogue for The Photographer's Eye at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1966 is the 'Frame'. I quote: 'The central act of photography is the act of choosing and eliminating, it forces a concentration on the picture's edge, the line that separates "in" from "out" and on the shapes created by it'.6While this statement was made in the context of a modernist restatement of photographic purity and essence, it has wider resonances if we allow ourselves to move outwards from this characteristic of the photograph rather than inward to a concentration on essence, and to consider the relationship of form and the making of historical meaning. I am not arguing that the medium is the message but that the cultural assumptions and expectancy both limit thinking about photography and put too greater stress on its indexicality. Rather, like Barthes, I would like to reintegrate the ontology into the rhetoric of the medium - insert the sense of magic, of theatre and even alchemy for history too embraces such subjectivities. The photograph awakens a desire to know that which it cannot show for it is perhaps an ultimate unknowability which is at the centre of the photograph's historical challenge. We are faced with the limits of our own understanding in the face of the 'endlessness' to which photographs refer. It was Siegfried Kracauer who saw 'endlessness' as one of his four affinities of photography.7 Even Szarkowski himself points in this direction in stating that the picture is bound by the plate but that the subject from which it was extracted went off in three dimensions, but he does not explore this idea.

Frame, in the way in which it contains and constrains, heightens and produces a fracture which makes us intensely aware of what lies beyond. Thus there is a dialectic between boundary and endlessness; framed, constrained, edged yet uncontainable. It is the tension between the boundary of the photograph and the openness of its contexts which is at the root of its historical uncontainability in terms of meaning. Derrida's argument on the activities of frames would seem pertinent here. While apparently naturalised, frames are essentially constructed and fragile. Framing and constraint impose artificially on a discourse constantly threatened with overflowing.8 This is so even of the most overtly oppressive of photographic practices, such as anthropometric photography, where the humanising marks of culture - the arrangement of hair, the cultural marking of the body such as cicatrices, pierce the objectifying image with the possibility of subject experience.9 Indeed it is perhaps the tensions between the intense objectified presentation of subject and an awareness of 'beyond' that is part of the power of such photographs.

Most important for my argument here is the theatricality of framing: an intensifying of the spatial and narrative arrangements which occur within the frame. But first it is necessary to explore the idea of performativity and theatrical in relation to photographs. One can argue that theatricality is linked to photography, and in two senses. First, the intensity of presentational form - the fragment of experience, reality, happening (whatever you want to call it) contained through framing - and second, the heightening of sign worlds which result from this intensity.

The idea of performance and its more overt and formal manifestation, theatricality, is not meant in the sense of the embedded formal qualities of drama as a genre, so much as a representation, heightening, containment and projection - a presentation which constitutes a performative or persuasive act directed toward a conscious beholder.10 The nature of the photographic medium itself carries an intensity which is constituted by the nexus of the historical moment and the concentration of the photograph as an inscription. This concentration, focus or containment has a heightening effect on the subject matter. It forces into visibility, focusing attention, giving separate prominence to the unnoticed and more important, creating energy at the edge. Further, photographs might be said to 'perform' the mutability of their signifying structures as they are projected into different spaces. For instance, how do photographs become 'anthropological'? Photographs have a performativity, an affective tone, a relationship with the viewer, a phenomenology not of content as such, but as active social objects projecting and moving into other times and spaces. This is more than passive images being read in different contexts, although that is obviously part of the equation. Rather as a heuristic device, we can see images as active through their performativity, as the past is projected actively into the present by the nature of the photograph itself and the act of looking at a photograph. One is reminded here of Mitchell's question 'what do pictures [here photographs] really want?' This is not a collapse into a personification and fetishism of the photograph, but rather to clear a space which allows for an excess or an extension beyond the semiotic to an appeal to the photograph, whose powers and possibilities emerge in the intersubjective encounter.11 Perhaps it is more intense at moments of encounter across systems of power and value, for such a heuristic device highlights points of fracture.

Peacock has defined performance as a condensed, distilled and concentrated life -an occasion when energies are intensely focused.12 Like performance or theatre, photographs focus seeing and attention in a certain way. Performances are also set apart. Likewise photographs are apart, being of other times and other places. Performances, like photographs, embody meaning through signifying properties, and are deliberate, conscious effort to represent, to say something about something. The sign itself is, in Schechner's analysis,13 performative in that it constitutes one or more bits of meaning which are related and projected into larger frames of performance, 'scenes' sequences of signs which embody narrative. Schechner's model allows us to link the mutability of the photograph's signs with their historical contexts, in that larger frames of performance - the cultural stage on which the drama of the photograph is played out - are comprised of the smaller, onto which it in turns deports meanings in a mutually sustaining relationship.

Theatre also confronts the viewer - opens a space for reflection, argument and the possibility of understanding. For Dening, 'Theatricality is deep in every action ... the theatricality always present, is intense when the moment being experienced is full of ambivalences'.14 It is through the heightening nature of the medium - that theatricality within the photograph and its inscription - that points of fracture become apparent. The incidental detail can give a compelling clarity, through which alternative histories might be articulated and the performance extend the possibilities of authorship of history through the interaction with precisely those points of fracture. Significantly the Soviet filmmaker, Sergei Eisenstein, perceived similar boundaries between photography and film as between theatre and film.15 Closing the triangle surely aligns photography with theatre. To refer back to my quote at the beginning - 'it is in the theatre that we know the truth'. Consequently one can argue that there is a massing of ideas which point in the direction of a certain performative quality in photographs.

I am going to look at three different ways in which the idea of performativity might be understood in relation to history and photography, first the theatre of the frame, second, the performance of making and finally theatre or performance within the frame. These are not mutually exclusive but rather integrally interconnected in the performance of history.

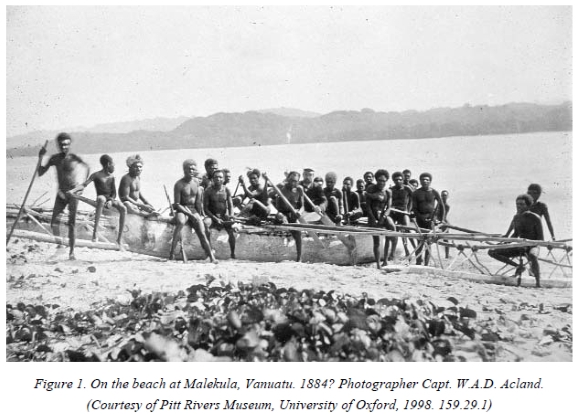

I want to consider first two photographs taken on the same occasion, in 1884, probably in March, at Malekula, Vanuatu (or New Hebrides as it was then). These photographs, as images to think with, become more than the sum of their parts.

Beaches have been described by Dening as 'beginnings and endings, frontiers and boundaries' that delineated the transformative space of cultural contact16 - not unlike photographs in some ways. These beach scenes, a recurring photographic trope in the Pacific, become intensified through the action of the frame. Their very ordinariness is transformed into a quiet theatricality which defines both the photographic moment and the colonial encounter on the edge of the island. It is pushed into visibility through the boundaries of the photograph. But the particulars within the frame overflow the pictorial limit onto the general cultural stage on which the little drama is played out.

The first photograph shows a group of Malekula people on their beach with a lieutenant from a Royal Navy sloop, H.M.S. Miranda, which was doing a tour of duty on 'The Island Run' as it was known (Figure 1). This was usually three to four months at sea out of Sydney, encompassing a huge chunk of ocean delineated by the run up through Norfolk Island, New Caledonia, Fiji New Hebrides and east to Samoa. The photographer was Miranda's commander William Acland, a well-connected young man doing the three-year posting on the Royal Navy's Sydney Station.

But what was happening that day at Malekula? What little history is it? There is a self-conscious acting out of frames or boundaries on the beach, rowing the outrigger canoe - sailors and boats, British and Melanesian.

Staged pictures such as this disclose specific intentions, as opposed to promising to reveal a priori meanings lodged in configurations of the world. There is also a theatricality in Michael Fried's sense, that the subjects project themselves or the drama forward to something external - the camera and the viewer. Hence we can attribute some significance to the self-conscious, intentional content of the photograph. We are looking here at encounters during the age of gunboat diplomacy. The scene on the beach can be read as a tense working out of a potentially volatile situation. Humour and camaraderie appear to defuse the situation. Boundaries and beaches, as Dening comments,17 are made of sensible things, raucous laughter and here, a canoe. Intimacy is suggested by the containment of both the canoe and the borders of the photograph frame, concentrating the viewer's attention, heightening content and moving the latter from the purely informational to the realm of alternative representations and contemplations.

I would argue that there are layered spatialities in this photograph, intensified by the framing of the photograph. A naval lieutenant is 'inserted' into the Melanesian physical space of the outrigger canoe. At one level the theatre of action on the beach would appear to fracture Melanesian space and make the colonial power relations visible, yet absence or silence can be a resonant active presence, a familiar device in both theatre and photography. Melanesian space may appear suppressed in the photographs, but it is present, embodied in Melanesian social being on their beach. Land is important in Melanesian societies, being linked to status through the production of food, but sea is equally so. One is a continuation of the other. Thus geographical 'facts' link people to their history and the organization of local knowledge and to Melanesian perceptions and definitions of space.18 Malekulans, through presence of their own cultural understandings of that space, mark it within the photograph, if we, the viewers, only allow them that space. While this is intensified by the frame it cannot here necessarily be reduced solely to the action in the frame alone, but to the quiet assertions of intersecting histories which become more visible through the heightening action of the frame.

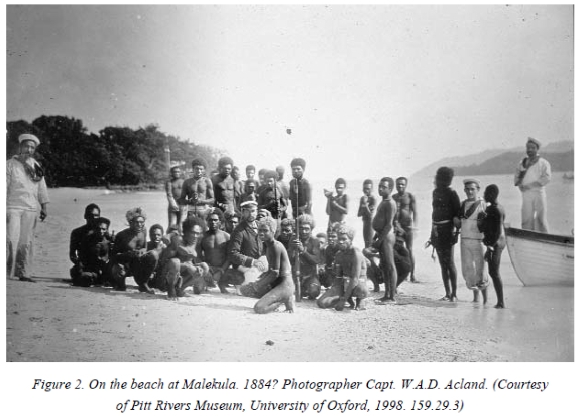

Another beach scene, taken at the same time is similarly carefully framed and composed (Figure 2). The coming together of recognition and framing, as Szarkowski suggested, is the photographer's primary act, dictating, in our contexts, what is performed as history and what is not. Two naval ratings form the left and right frames condensing the group. The one on the right standing in the bow of the ship's boat which projects into the frame. At the water's edge another seaman stands, arms linked (steadying perhaps in the relatively long exposure of two or three seconds) with those of two Melanesians.

However the controlling frame both physical and metaphorical has started to spring a leak, as containers do. The leak is a semiotic excess or energy, which manifests itself as the rawness, the ambiguity or ultimate uncontainability of the photograph as history. Kracauer's 'endlessness', triggered by the fortuitous, reaches beyond the frame. Frame, in this register, marks a provisional limit only: its content refers to other contents outside that frame. Within the containment of the image, small heightening details, such as the linked arms, a pair of boots (naval boots?) slung around someone's neck, assume a metaphorical and symbolic density. The careful presentation to the camera has the quiet theatricality with all the self-consciousness that such a tableau entails, as both parties project their contesting spaces for the resulting image. However the medium disguises the gesture, utterance and resonance on which fragile relations, such as those on the beach at Malekula, depended. Their absence is made palpably present through the photographs if we imagine the theatrical possibilities of the temporally suspended gesture, the stayed glance, the motionless finger on a forearm.

These two images assume what Daniels has described as 'high specific gravity', for they appear to 'condense a range of social forces and relations'.19 The heightening effect of stillness within the frame as the historical moment is performed for us, opens up possibilities not for seeing what the picture is 'of' in forensic terms but rather, and more significantly, for this is where I believe photographs are an unique form of history, they can suggest the experience of the past. Kracauer, writing of the distinctions between painting and photography, encapsulates their historiographical need: 'In order for history to present itself, the mere surface coherence of the photograph must be destroyed'.20 While photographs particularise, at the same time they resonate with that beyond themselves, they explain something of that world which made them possible in the first place. These photographs show Melanesian spaces here are at the point of negotiation, between space and types of power, between what is close to individuals and those remote and exterior forces, such as the Royal Navy and colonial policy, in which local life is enmeshed. The photographs on the beach are part of an endless continuum of microscopic incidents actions and interactions which constitute a historical reality.21 The fragmenting nature of photography brings the experiential moment to notice, visibility, an indiscriminate privileging of moment. Conversely it is the studium, to use Barthes' model, that by giving context allows punctum, the detail that assumes significance, to be recognised - the steadying finger for instance. Without frame, physical and metaphorical there is nothing to pierce. This is what I mean by the theatrical heightening of photography - allowing lines of fracture to appear and the space for alternative readings or histories to emerge.

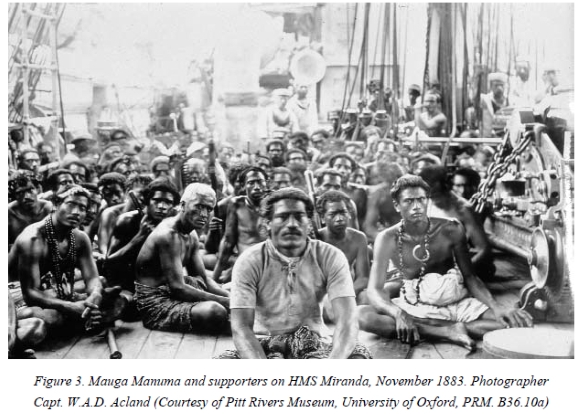

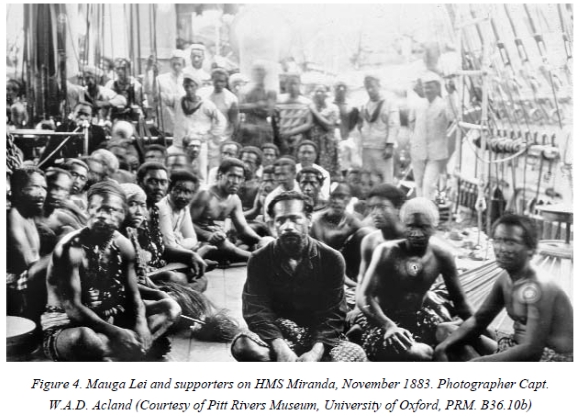

This is even more marked in two photographs taken by the same photographer a few months earlier in November 1883 (Figures 3-4).22 The surface appearance is that of the archetypal colonial image - islanders on a gunboat, or labour boat, cruise ship surrounded by sailors or tourists or the merely curious. But again engaging with the heightening intensity of space and moment through the fragmenting character of photography opens the space for alternative histories. Again it can be read as a performance. The very existence of these photographs, like the last two we looked at, breaks through the enclosed space of textual histories around this event - the meeting of two rival claimants to a Samoan chiefly title, Mauga of Tutuila, who have been brought on board H.M.S. Miranda so that the colonial powers can impose a peace on the latter's terms. The details are beyond the scope of this paper for what concerns me here is the way in which the photograph, through the heightening containment of the frame, confronts the generalising narrative of history and performs an alternative set of statements of power. It returns the specificity to the historical moment and forces it to signify.

Here we see even more clearly the way in which the photograph seizes a moment from the flow and process of existence and gives an intensity of moment. The act of photographing endowed this event with a permanence and theatricality which echoes at an abstract level the performance of the event itself. Further, the intensified fragment of event held in the photograph mirrors the intensified fragment of cultural power embodied in the ship, the British gunboat. Acland, the ship's commander, had intended this meeting of the Maugas precisely as a performance of political authority, the ceremonial itself being an integral part of that authority articulated in the spectacle or visibility of the moment. The photographs thus become the very essence of that moment.

However, a point of fracture is in place. Despite the appearance of containment within the space of a British gunboat, there is a Samoan spatial articulation clearly at work, which, rather than being fractured by expressions of colonial power, actually asserts its own cultural cohesiveness and fractures (or perhaps subverts) the totality of authoritative space. One could argue that the process of emerging global power is confronted by conscious local configurations of space.

Pre-existing socio-political hierarchy in Samoa provides precise spatial configurations premised on the socialised body, notably demonstrated in the village meeting. The claimants here, as high chief (the Maugas), are seated in the centre, over their right shoulders are their orators, 'talking chiefs' with limed hair and carrying the ceremonial fly-whisk, who spoke for the chiefs and served as chief advisors. Given that these crucial protagonists are in an ethnographically confirmed spatial arrangement and the other senior men appear in broadly semicircular array around the Mauga, it is not an unreasonable assumption that the rest of the entourage express hierarchical and kinship relations spatially, reproducing Samoan space and the authority such an arrangement carries, on the Quarter Deck of HMS Miranda. The spatial arrangement evident in the photographs speaks to a more complex intersection of authorities than the colonial written record might suggest. We cannot know it all, but the intensity of visualization which the photograph constitutes presented a line of fracture which allows an alternative view of what happened at 10.30 on 17th November 1883 on the Quarter Deck of HMS Miranda.

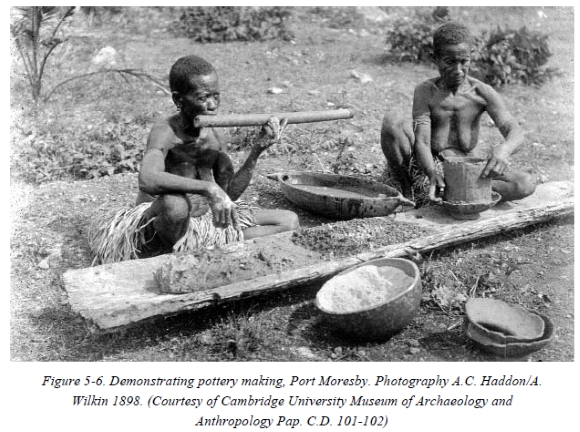

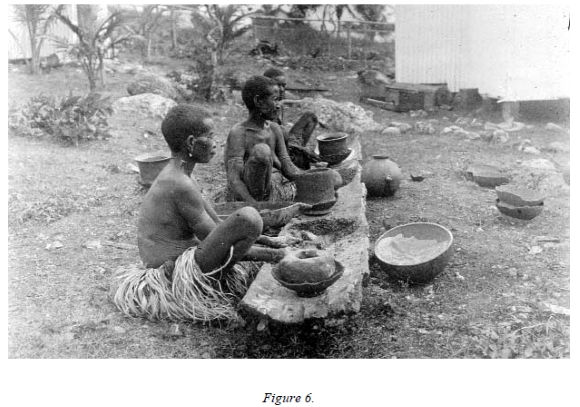

I want now to look briefly at the performativity of the act of photographing. In many ways this is a less complex manifestation of the idea of performativity than those I have just considered. Nonetheless, it is one crucial to the relationship between photography and the making of history. We can see this operating through a very different and unremarkable set of photographs taken near Port Moresby, British New Guinea in 1898. They demonstrate again the way in which content can be understood to extend beyond its subject matter. In these photographs we can actually see the performance of making photographs - the photographs show us the act of observation.

Here photography acts out the process of observation and the collection of visual data in an anthropology embedded in colonial relations (Figures 5-6). The acting is dependent too on frame. At one level the genre of the photographs is that of unmediated observation, immediacy and absorption which denies the presence of the viewer, an increasingly dominant truth value in anthropology at the end of the 19th century. However the way the camera moves around the group of women working at the 'bench' introduces an active spatial relationship between observer and observed. One feels the act of observation as the camera, acting as the viewer's eye, moves around the group 'to see better', 'to reveal more', to intensify the record. Spatial and kinetic qualities are clearly evident -the observer is embodied, outside the photographic frame as Antony Wilkin, the expedition photographer or Alfred Cort Haddon, the expedition leader (they did the photography between them) move around the group.23 There is a strong performative quality on two axes. First within the group, which is absorbed in the narrative action of making pottery, and stresses the distance from the viewer. The second is interactive, the performance of observation stresses the presence of the viewer, and the making of scientific information. These two are worked out simultaneously within the same performative space. Frame is again a provisional limit. It is fractured by what is beyond and relationships beyond - the container has again sprung leaks. The direction of responses of the women suggests there was another focus of attention or conversation, another camera perhaps, or interpreter or perhaps a local colonial officer, David Ballantine, who orchestrated the performance of making the pots. There is a sense of interaction between the whole group, not merely between performers and camera but by constant reference to what is beyond the frame over multiple spatial axes.

The performance of photographing is also clear in a series of three images of tattoo processes. Again there are shifting camera angles and, more significantly intrusions, into frame. Shadows, indexical traces of the act of observation, literally the shadow of the gaze, inscribe observation, they are both figurative and paradoxical, a symbol of presence and absence. They point to the unseen viewer's dominant space beyond the frame stating the authority of authorship. Here the unintended details, the fortuitous, reveal the nature of making history. Further these particular photographic encounters were framed within colonial relations where culture was performed for the camera and the camera performed culture.

I want to look finally at a photograph of re-enactment, a performance outside 'real time' and 'real life' because a consideration of it, in conjunction with the nature of photography, suggests how content, form and the nature of inscription come together in a performance that, very literally, makes history. It also fulfils some main characteristics of performance - preparation and presentation which are translated through photography, as an unmediated experience. This then is launched on the normalised temporal trajectory of photography as s the 'there-then' becomes 'here-now'. Further in relation to my argument here, this photograph assumes an allegorical nature, another performance where the images becomes revelatory and transcendent. Like the Malekula photographs it becomes paradigmatic of the link between theatre and frame, photography and history. It is conceptually very complex in configuration. This particular photograph is linked to salvage ethnography, which like the photograph, constitutes another temporally defined imperative concerned with the threat of disappearance. The scene is Mabuiag Island, Torres Strait on 21st September 1898.24

The subject is Kwoiam, the totemic hero, whose mythic cult was central to all western Torres Strait initiation and death ceremonies (Figure 7). It is in a series of images, made to 'record' this central myth. Here we have the visualisation of the very root of myth, not only in the photographing of sacred spaces, the sites of mythical happenings, but in this case through the re-enactment of a mythical moment which defined the topographical space and social space in Torres Strait - the death of Kwoiam. The landscape was defined mytho-topo-graphically, marked through contact with Kwoiam's body and those of his victims - his footprint is in the rock, boulders are the heads of his victims. The landscape is mapped through his social interaction: a stream that never dries is the place where he thrust his spear into the rock, the grassy planes studded with pandanus are where he had his gardens. His exploits themselves involved much slaughter and associated head-hunting but, to cut a long story short, eventually Kwoiam was ambushed by his enemies. He retreated to the summit of a hill where, crouched on the ground, he died.

Haddon writes with interesting rhetorical slippage:

The bushes on the side of Kwoiam's hill have most of their leaves blotched with red, and not a few are entirely of a bright red colour. This is due to the blood that spurted from Kwoiam's neck when it was cut at his death; to this day the shrubs witness this outrage on a dead hero.25

But Haddon also writes immediately before this passage:

I wanted one of the natives who had accompanied us to put himself in the attitude of the dying Kwoiam, so that I might have a record of the position he assumed, photographed on the actual spot ...26

To conclude, it has been argued that theatre, like photography, is merely the reproductive slave of the ideological apparatus of reproduction which can only free itself by the notion of true performance. By using ideas of performativity, the heightening effect, in relation to photographs, one can, I would argue, do just this, bringing to the surface a grounded historical meaning which moves beyond the merely mimetic. I hope I have shown through this historiographical exploration certain relationships between photography and the performance of history in bringing the points of intersection and fracture to the fore. In this register the trivial the ordinary and unconsidered reveals, through the density of its multiple layers, the possibilities of the histories condensed within it.

Michael Fried has written of painting that tableaux vivants scenes may be understood to show that there can be no such thing as an anti-theatrical work of art - that any composition, by being placed in certain contexts or framed in certain ways, can be made to serve theatrical ends.28 Within my argument for photography as a performance of history one could make similar claims. One can also claim that such an argument goes at least someway towards giving photographs an idea of visuality in history adequate to their ontology.29

While photographs may have different densities in the way in which they bring together a field-force of social relations and present their contents, they nonetheless carry with them the characteristics of photography as a medium of inscription. As such they are all touched, at their edges, to a greater or lesser extent: family photographs, official photographs, portraits. Their containments have the potential for performing histories in ways in which perhaps we least expect, when they are used not merely as evidential tools but as tools with which to think through the nature of historical experience. The positioned subjectivities in looking at photographs leaves a space to articulate other histories outside dominant historical methods. In using performance as a tool to think with I hope I have suggested a crucial characteristic of the photograph's agency in all this, as we try to come to grips with the relationship between photography and history.

* This article was originally presented as a keynote paper at the international conference 'Encounters with Photography', held at the South African Museum in Cape Town, July 1999.

1 Elizabeth Tonkin, Narrating Our Pasts (Cambridge, 1992), 64.

2 Greg Dening, Performances (Melbourne, 1997), 101.

3 Florike Egmond and Peter Mason, 'A horse called Belisarius', History Workshop Journal (1999) 47, 249.

4 N.Thomas, In Oceania: Visions, Artifacts, Histories (Durham NC, 1997), 34.

5 Tonkin, Narrating Our Pasts, passim.

6 John Szarkowski, The Photographer's Eye (New York, 1966), 9.

7 The others being 'an outspoken affinity with unstaged reality, fortuitousness and indeterminacy.' Siegfried Kracauer 'Photography' reprinted in Alan Trachtenburg, Classic Essays in Photography (New Haven, 1980), 263-265.

8 Jacques Derrida, 'Parergon' in The Truth About Painting, transl. G.Bennington & I.McLeod, (Chicago, 1987), 70.

9 See Elizabeth Edwards, Raw Histories: Photographs, Anthropology and Museums (Oxford, 2001), 144-47.

10 Michael Fried, Theatricality and Absorption: Painting and Beholder in the Age ofDiderot (Berkeley, 1980).

11 W.J.T. Mitchell, 'What do Pictures Really Want?', October (1996), 79.

12 James Peacock, 'An ethnography of the sacred and profane in performance' in Richard Schechner & Willa Appel (eds), By Means of Performance (Cambridge, 1990), 208.

13 Richard Schechner, 'Magnitudes of Performance' in Schechner & Appel (eds), By Means of Performance, 44.

14 Dening, Performances, 109.

15 Quoted in Kracauer, Photography, 256.

16 Greg Dening, Islands and Beaches: Discourse on a Silent Land: Marquesas 1774-1880 (Honolulu, 1980), 31-32.

17 Ibid, 20.

18 L. Lindstrom, Knowledge and Power in a South Pacific Society (Washington, 1990), 51 & 71.

19 Stephen Daniels, Fields of Vision: Landscape Imagery and National Identiity in England and the United States (Cambridge, 1993), 244-245.

20 Siegfried Kracauer, 'Photography' in The Mass Ornament: Weimar Essays, transl. & ed. T. Levin (Cambridge MA, 1995), 52.

21 Roland Barthes, 'The Rhetoric of the Image' in Image Music Text transl. S. Heath (London, 1977); Dagmar Barnouw, Critical Realism: History, Photography and the Works of Siegfried Kracauer (Baltimore, 1994), 251.

22 Edwards, Raw Histories, 107-29.

23 For an extended consideration of the British New Guinea photography of Haddon and the Torres Strait Expedition, see Elizabeth Edwards, 'Surveying Culture' in M. O'Hanlon & R. Welsch (eds), Hunting the Gatherers: Collecting and Agency in Melanesia (Oxford, 2000), 103-26.

24 For a detailed consideration of the photography of the Torres Strait Expedition see Elizabeth Edwards, 'Performing Science: still photography and the Torres Strait Expedition' in A. Herle & S. Rouse (eds), Cambridge and the Torres Strait: Centenary Essays on the 1898 Anthropological Expedition (Cambridge, 1998); and of this photograph see Edwards, Raw Histories, 157-80.

25 A.C. Haddon, Headhunters, Black, White and Brown (London, 1901), 147.

26 Ibid.

27 Dening, Performances, 48 and passim.

28 Fried, Theatricality and Absorption, 173.

29 Mitchell, 'What do Pictures Really Want?', 82.