Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of Vocational, Adult and Continuing Education and Training

On-line version ISSN 2663-3647Print version ISSN 2663-3639

JOVACET vol.7 n.1 Cape Town 2024

https://doi.org/10.14426/jovacet.v7i1.390

ARTICLES

How implementable is e-RPL in the public TVET sector after COVID-19? Learnings from the Western Cape

Nigel Prinsloo

University of the Western Cape, Institute for Post-School Studies, Faculty of Education, Bellville, Cape Town ORCID link https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6970-7747 (nprinsloo@uwc.ac.za)

ABSTRACT

'e-RPL' is referred to as the unique practice of using electronic, digital and mobile web technology to collect and record evidence of prior learning acquired formally, non-formally or informally, or as a combination of these (Cameron & Miller, 2014). This article reports on a small-scale study of artisan recognition of prior learning (ARPL) implemented at public technical and vocational education and training (TVET) institutions in the Western Cape province, South Africa. Current practice is reviewed and opportunities for, and barriers to, implementing e-RPL are explained. The author attempts to investigate whether it has been possible to apply e-RPL and e-Portfolios effectively in ARPL at public TVET colleges in the TVET environment since the COVID-19 pandemic. It was found that, although ARPL is gaining traction at selected public colleges, funding and resource constraints remain a significant impediment to expanding it. The form of e-RPL evident at the institutions of higher education studied was limited to the administration of ARPL. Although pilot projects have used mobile technology, they have been limited in their extent and effectiveness. The author concludes that e-RPL holds promise as a means of expanding RPL access and provision during times when physical contact is curtailed. However, the potential of e-RPL tends to be tempered by the socio-economic realities affecting potential candidates.

Keywords: Recognition of prior learning (RPL); artisan; e-RPL; artisan recognition of prior learning (ARPL); e-Portfolio

Introduction

The South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA) defines recognition of prior learning (RPL) as

the principles and processes through which the prior knowledge and skills of a person are made visible, mediated and assessed for the purposes of alternative access and admission, recognition and certification, or further learning and development (SAQA, 2019:6).

Artisan RPL (ARPL) was introduced through a series of pilot programmes at accredited trade test centres in 2017 to replace the section 28 Trade Test of the Manpower Training Act 56 of 1981. This enabled workers who had not received formal training to have their experience assessed against the criteria required by a specific trade. Successful completion of an RPL assessment would allow the candidate to do a trade test and ultimately become a fully fledged artisan. ARPL was conducted solely face-to-face.

However, in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic forced education and training institutions in the post-school sector to rethink their methods of teaching, learning and assessment (OECD, 2021). Face-to-face lessons were replaced with a combination of Zoom, Google Meet and WhatsApp platforms. Assessments also transitioned from the traditional sit-down examinations to online assessments. Whereas these online assessments could be applied when testing theory, practical tests requiring observations were not easily accommodated (OECD, 2021).

COVID-19 also had an impact on the ARPL processes, with several centres having to close during the lockdown phase of the pandemic. Now, in the post-COVID-19 environment, there have been calls to move the RPL assessments online, particularly for those candidates who live in areas far from recognised RPL centres.

Costs are an important barrier to accessing RPL opportunities; they could range from R1 800 for an RPL evaluation to around R13 000 for the six-week gap training and trade test preparation. If not funded or supported by business, workers would not be able to afford these costs. At the same time, access to online opportunities, especially for the poor, was curtailed and so the existing race, class and gender divide was exacerbated by the digital divide. With many ARPL candidates being poor and living in rural and peri-urban areas, access to resources, including the Internet and Wi-Fi, are affected negatively. A 2022 report by the World Economic Forum on data costs in Africa found that South Africans pay up to R85 per gigabyte of data, a cost equivalent to nearly four hours' work for people earning the minimum wage (Harrisberg & Mensah, 2022). This resulted in reduced access to resources for electronic RPL or e-RPL.

In South Africa, a key philosophical and legislative or policy underpinning of RPL is to provide access and to enable redress for the racial injustices of apartheid in order to further learning and personal advancement. Supported and driven by the union movement (Cooper, 1998), RPL was considered to be a vehicle through which workers would have their skills recognised and certificated, which would, in turn, result in commensurate increases in remuneration. This is captured in policies such as the SAQA RPL policy (2019), the Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) RPL Coordination Policy (2016) and the Quality Council for Trades and Occupations (QCTO) RPL Policy (2014). Progressive steps have also been taken to broaden access to RPL opportunities, particularly in the artisan space, including attempts to increase the number of decentralised trade test centres that offer ARPL.

Internationally, there has been increasing emphasis on developing e-Portfolios in RPL for artisans by means of which candidates develop and upload their portfolios of evidence onto an online platform. However, the relevant literature, particularly that from Australia, Europe and New Zealand, points to some of the challenges and opportunities of this approach to RPL (Cameron, 2012; Chan, 2022; Stojanovska-Georgievska et al., 2023). Chan (2022) investigated the increasing use of technology to assist in the process of upskilling workers in a changing work environment in New Zealand. Chan's study, which focuses on the vocational educational system, notes the increasing role of e-Portfolios in these changing contexts and in the promotion of lifelong learning. Stojanovska-Georgievska et al. (2023), focusing on the European Union, investigated the development of digitisation, especially the use of the e-RPL tool for creating a web-based application that would replace the document-based procedure for RPL. The authors argue that there is a need to have the predetermined criteria for qualifications in place before the minimum requirements for mutual acceptance, recognition and validation of qualifications, based on the existing occupational standards which need to be defined first in order for e-RPL to be effectively implemented. They also note the advantages of using various web-based platforms to streamline the RPL process.

Cameron (2012) notes that the use of e-Portfolios in RPL processes in the workplace and professional-practice contexts attracted little attention in the literature due to its emergent nature. Her study explored the growing use of e-Portfolio-based RPL (e-RPL) and professional recognition (e-PR) processes in Australia and the implications of these for recognising workplace learning and experience.

Although the study was limited to the Australian context, Cameron (2012) found that an array of e-RPL and e-PR were being used across multiple fields, disciplines and contexts. She also found that the occurrence of e-PR was more dominant than that of e-RPL and this resulted in the development of a framework that provided the conceptual scaffolding for recognition systems in the workplace.

Cameron (2012) outlined the implications of the correct matching of practices and tasks to appropriate types of e-Portfolio-based RPL and PR along a continuum of formal and informal learning, and with varying degrees of learner control. This highlighted the complexity of RPL assessment systems in the workplace and training institutions.

More recently, a Kenyan study by Ligale (2023) has provided an African perspective on the potential benefits of the use of e-RPL to allow for wider access to potential candidates and by modifying the e-learning platforms in Kenya to achieve this. In considering e-learning, Ligale (2023) argues that e-learning support is mainly facilitated by content design, the quality of e-learning systems, learner experiences and feedback, social support, assessment and evaluation, and institutional factors.

Based on the international literature reviewed above, can e-RPL and e-Portfolios increase viable access to RPL opportunities at public vocational institutions? This article therefore seeks to answer two questions:

1. What, if any, are the current practices of RPL in the public TVET sector?

2. What are the potential barriers to and opportunities when implementing e-RPL at public TVET colleges?

Theoretical framework

This study uses two theoretical lenses to frame the study: Activity Theory is used to provide a theoretical basis for the ARPL context, and a Critical Theory of Technology (CTT) lens is employed to evaluate the use of e-RPL in the TVET sector.

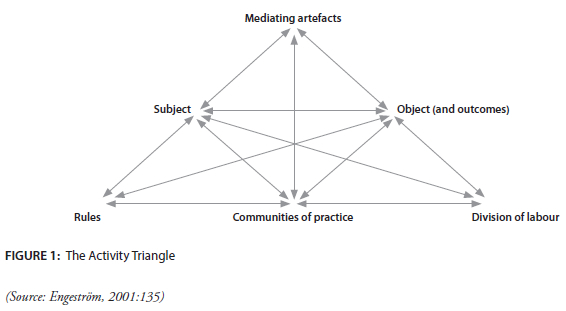

Activity Theory considers the ways in which human activities are regarded as systemic and socially situated phenomena that include work systems, community, history and culture (Engeström, 2001). Developed further by Engeström, the well-known 'Activity Triangle' captures the key players in this process, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1 shows a network of relationships between a subject (an individual or an organisation) and its object. It indicates that, for a subject to achieve its goals, more than a direct relationship is needed. To achieve a goal, mediating tools, rules, communities of practice and the division of labour are required. The arrows show how each part of the activity could influence another part in the activity system.

Activity Theory or Cultural-Historical Activity Theory (CHAT) is particularly useful in capturing the roles of the different actors and contexts involved in RPL. Naudé (2016) notes that RPL candidates struggle to link their knowledge gained through workplace experience to the requirements of the qualification. The role of the RPL assessor in this case is critical in the process of making the tacit knowledge and skills visible.

Naudé (2016) highlights activity systems: the academic and those in the workplace. The academic institution as an activity system uses the components of the activity system to generate new knowledge and disseminate disciplinary knowledge with strong rules and boundaries. These disciplines are strongly coded in a community of practice, which does not allow the less informed to get behind these boundaries. The more solid the boundary, the more narrowly defined are the knowledge and skills.

The workplace could be described in a similar manner but as a different context. The tools, rules, communities of practice and division of labour have similarities (policies, procedures, manuals, etc), but also clear differences (i.e. the absence of journals, academic traditions and disciplinary boundaries, and different communities of practice) when compared with the academic institution. The ARPL process pays special attention to the competencies that are needed by the workplace or industry.

Naudé (2016), when focusing on rethinking RPL, notes the importance of mediating tools. He argues that

[m]ediating tools play an important role in determining whether [an] RPL advisor could unlock the knowledge that candidates have obtained in the workplace. The concept of mediating tools provides a starting point for transferring workplace knowledge into academic knowledge (2016:10).

This is particularly important when considering the role of the ARPL toolkit (mediating tool) and the role of the RPL assessor. The way the assessor engages with the RPL candidate is important in order to allow for a broader assessment of competence, especially when considering e-RPL.

The Critical Theory of Technology (CTT) is used in research to examine and critique the social, political and economic dimensions of technology. This theoretical lens goes beyond the technical aspects of technology to explore its broader impacts on society, emphasising the interplay between technology and power structures. The CTT argues that technologies are not separate from society but are adapted to their social and political environment. Since technologies are implicated in the sociopolitical order they serve and contribute to shaping, they cannot be characterised as either neutral or as embodying a singular 'essence'. According to Feenberg (2008), two philosophical streams underpin CTT: substantivism and constructivism. Substantivism emerges from a philosophy of technology and argues that technology is autonomous and inherently biased towards domination. Constructivism, in contrast, emerges from contemporary social science. Social studies of technology pursue empirically grounded investigations of technological design and development. Feenberg (1991) states that a CTT seeks to reconcile the schism between the substantivist and the constructivist theories of technology.

This theoretical framework adds a useful lens through which this study can be evaluated, in that it allows for a balance between debates of what constitutes knowledge, skills and competence, on the one hand, and the use of technology to validate or reinforce patterns of dominance, on the other. However, in the post-COVID-19 context, a shift to online assessment and the promise that this holds, particularly in the context of e-RPL, needs to be tempered by the stark realities of the digital divide, the demographics of the ARPL candidate, and also the extent of access to necessary resources. Technology can also serve as a barrier to teaching and learning due to the lack of access to online platforms - which goes against the underpinning RPL aims of access and redress.

The use of these two theoretical perspectives will provide useful lenses through which to analyse both the ARPL process and the use of e-RPL. Both CTT and Activity Theory or CHAT allow for a critical analysis of the interplay between technology, society, learning and experience. Activity Theory highlights the various activity systems that form the basis of socially situated processes, including community and workplace. It draws from the basis of situated learning as espoused by Vygotsky (Cole et al., 1978). CTT considers the way technology affects the social, economic and political dimensions of society. The theory also investigates the interplay of technology and the maintenance of social and knowledge hegemony. The CTT theoretical perspective highlights the important role of technology in Activity Theory systems, in this way providing insights into the tensions and contradictions of technological solutions for professional occupational practice when compared with traditional practices of face-to-face human observations of competence.

e-RPL in TVET - a policy context

In recent years, policies in South Africa have raised the profile of RPL in the national discourse. For instance, the White Paper on Post-School Education and Training (WPPSET) (DHET, 2013c) highlighted the importance of RPL for enhancing the mobility and employability of candidates. The WPPSET states that RPL is an important approach to 'redressing past injustices and recognising competence gained through practical workplace learning and experience' (DHET, 2013c:93). The varying conceptions of RPL and competence, the policy suggests, have been detrimental to streamlining and embedding RPL in the education and training system.

Skills development policies have, however, been developed against the backdrop of a decline in the manufacturing capacity of South Africa, which has seen a reduction in large-scale apprentice training by state-owned enterprises (Bhorat et al., 2020). There have also been debates about the goals of the National Qualifications Framework (NQF) when considered against the National Plan for Post-School Education and Training (NPPSET) and, more particularly, the backdrop of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) (Loots & Butcher, 2021). Commentators on ARPL and subsequent policies such as the WPPSET (DHET, 2013c) have therefore urged that an increase in the number of qualified artisans be achieved through artisan RPL so as to meet the development targets of the National Development Plan (NDP) (Presidency, 2012). This was also captured in the National Skills Development Plan (2011) and the NPPSET (2023), where targets were laid down that include the training of 5,1 million students across higher education, TVET and adult education. This includes the training of 30 000 artisans per year by 2030, of which ARPL is viewed as an integral component.

The current RPL policies also allow for the use of enabling technology to facilitate access and redress, but they are silent on how these will be implemented. For example, some RPL policies do not specifically refer to e-RPL, but they do note the broadening access and the standardisation of processes (SAQA, 2019). New policies continue to represent the changing education and training context and, by extension, RPL. The recently developed RPL implementation framework for post-school education and training (2024) that is open for public comment has highlighted the importance of technology at an assessment and administrative level to streamline the RPL process. Therefore, the use of technology to facilitate the RPL processes is considered to be an essential means to increase access to RPL opportunities.

However, the technicist approach to ARPL focuses primarily on assessing certain occupational competencies while other critical competencies are not assessed. The result is a more substantivist approach to the use of technology and equipment linked to a particular trade. The use of technology will also be affected by the age of the candidate and their access to equipment that is used in the trade (Feenberg, 2008).

The implementation of e-RPL is gaining increasing traction in South Africa, particularly in higher education institutions. This includes the use of e-Portfolios in the RPL process. e-Portfolios are understood to be electronic portfolios that use digital technologies. This allows the portfolio developer or RPL candidate to collect and organise portfolio artefacts in various media types (i.e. audio, video, graphics, text). An electronic portfolio is also known as a web folio, an e-Portfolio or a digital portfolio. (Softic et al., 2013; Chan, 2022; Stojanovska-Georgievska et al., 2023).

e-Portfolios are, however, not confined to RPL. In the workplace, for example, e-Portfolios are used to collect and record evidence of prior learning based on the current competencies that are required by an organisation or an employer. These purposes could be related to human resource management requirements such as job-related competencies, knowledge and skills or for skills audits such as skills gap analyses and performance appraisals (Cameron, 2012).

At higher education institutions (HEIs), the development and use of e-Portfolios have become more prevalent in recent times as a means of both assessment and a record of personal development, and also for use in RPL for access and advanced standing. However, although e-RPL and e-Portfolios are referred to separately, they are not mutually exclusive and are in fact complementary in the RPL context (Cameron, 2012; Ligale, 2023).

Research methodology

The study focuses exclusively on ARPL in the engineering trades of Motor Mechanic, Diesel Mechanic and Welding. When compared with RPL applied in HEIs, ARPL in TVET colleges is applied in a more technicist and more narrowly defined manner. The data for this article are drawn from two sources: a 2017 pilot project report of ARPL implementation at technical and vocational institutions; and a 2021 study of ARPL implementation in TVET colleges and the workplace. Both data sources were obtained in the Western Cape province of South Africa and processed by the institute at which the present author works. The data from this small-scale study was primarily derived from interviews the author conducted with key stakeholders, including TVET college and workplace managers and RPL practitioners, in addition to observations. In the 2017 pilot study, a total of ten individual, semi-structured interviews were conducted and the same number of observations of the ARPL processes were made. The study interviewees included managers, ARPL practitioners and candidates. The 2021 study included a total of 32 interviews, which were conducted at six public TVET colleges and three workplaces. These studies highlighted key barriers to broadening the findings and recommendations drawn from the report and the study. The findings of this study focused on the possible applications of e-RPL and e-Portfolios. The interview data were transcribed and analysed using Atlas Ti and coded themes were then derived, one of which was the potential use of e-RPL.

A limitation of this research is that it was a small-scale study that focused on RPL implementation in the public TVET context and that it may not be capable of generalisation to the TVET sector or other sectors.

Findings: Current RPL practice in TVET - the ARPL toolkit

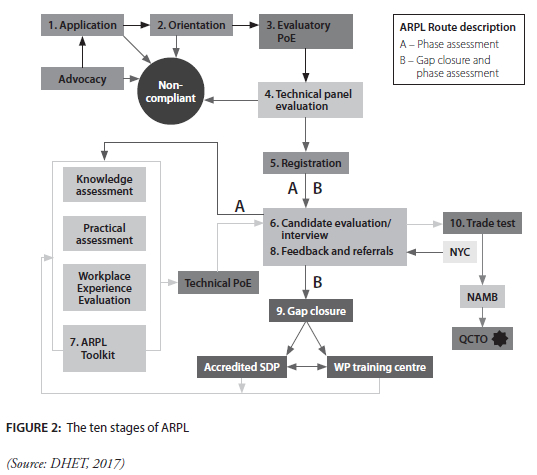

As mentioned previously, the RPL processes in TVET colleges were initially implemented according to the Manpower Training Act (MTA) of 1981. In 2016, this was streamlined into what was known as RPL toolkits, which were promulgated by a series of Trade Test Regulations as new toolkits for trades were developed (DHET, 2017). The ARPL process is presented in Figure 2. The paragraphs below the figure capture the ten key stages in the ARPL process in addition to the e-RPL status and opportunities.

The ten stages of ARPL (DHET, 2017) illustrated in Figure 2 present opportunities for e-RPL, and these are captured below. The current level of technology use is also discussed.

Stage 1 - application

At this stage, candidates are encouraged to apply. The minimum entrance criteria are the minimum verifiable entrance criteria for an assessment as per the DHET Trade Test Regulations (2013 a), which include being 19 years of age or older. Candidates may be either employed or unemployed, with a minimum of three years' verifiable work experience in the diesel, motor mechanic or welding trades. Although currently used at most ARPL centres, the online application process is still in its infancy at some public centres.

Stage 2 - orientation

At this stage, potential candidates are introduced to the ARPL process and what it entails. They are counselled as to their expectations and what is required to complete the process successfully. Orientation usually comprises a plenary session followed by one-on-one counselling by an ARPL assessor.

Orientation is currently done mostly via a face-to-face process or a telephonic interview with an ARPL assessor. e-RPL possibilities in this regard include using platforms such as Google Meet and WhatsApp that would allow remote interview opportunities.

Stage 3 - evaluatory portfolio of evidence (PoE)

This stage comprises the development of a portfolio that includes a record of employment, experience and qualifications. One of the challenges here is assisting or guiding the candidate to find the relevant information.

At present, the PoE development is an intensive process requiring regular contact sessions between the RPL practitioner and the candidate. Whereas there is a move to shift to online platforms, most portfolios are currently article-based. However, a move to e-Portfolio development will alleviate additional costs, such as printing, for candidates.

In some sectors, such as the professional body for sports coaches, the South African Sports Coaching Association (SASCA), the use of e-RPL for designations is widely used and has produced very good and credible results. However, e-RPL in the artisan environment could benefit from researching these case studies in other contexts where e-RPL practices have been piloted and then implemented on a larger scale.

Stage 4 - technical panel evaluation

The panel comprises subject-matter experts (SMEs) who will evaluate the portfolio prepared by the candidate. This evaluation will determine whether the student progresses to the next phase.

Evaluations are mostly performed by SMEs at the college or workplace in consultation with the Sector Education and Training Authority (SETA). They can also be done using a common platform if the SME is not in the same location as the candidate. This will also deal with logistical constraints when there is a shortage of expertise.

(Stages 1-4 have stop-outs built in where students are counselled as to what processes to follow. Successful candidates move on to Stage 5.)

Stage 5 - registration

Successful candidates are registered whereas those who are not successful are advised on what to do. Registration is currently done online at the colleges and workplaces, although it will be important to consider enhancements, including the use of common platforms.

Stage 6 - candidate evaluation

Candidates are then interviewed and evaluated for trade test readiness based on their PoE. At this stage, they are either considered to be ready for the ARPL assessment or they will require training to fill in skills or knowledge gaps. The interviews are mostly conducted face-to-face but there are moves afoot to have this done online using video platforms such as WhatsApp, Google Meets or Zoom, or even telephonically. By conducting these interviews online or telephonically, travel and accommodation costs will be reduced for candidates.

Stage 7-ARPL assessment

The candidate is assessed via the ARPL toolkit. This includes a knowledge assignment, a practical assignment and a workplace evaluation. The assessment process is conducted through face-to-face sessions during which the candidate and the assessor are physically present. There are, however, opportunities to use readily accessible platforms to conduct the assessment remotely. This requires an ARPL assistant to be present with the candidate and an RPL assessor who can operate remotely.

Stage 8 - candidate evaluation

Based on the results of the ARPL evaluation that includes the interview and ARPL toolkit assessment, the candidate may either be considered fit to proceed to the trade test or may be required first to undergo additional training. Currently, candidates are informed and counselling takes place either face-to-face or telephonically and, where possible, via email. Where gap training is required, counselling is conducted between the RPL assessor and the candidate. Nevertheless, using appropriate platforms that allow online meetings may facilitate the process of counselling and support - especially where the candidate resides far from the training centre. The ARPL process ends at this stage. Being RPL for access, successful completion enables the candidate to do the trade test, which is explained below.

(It is important to note that Stages 9 and 10 are not part of the RPL process but an assessment required of all apprentices. Successful completion would mean that an apprentice or labourer would receive their trade test certificate and be recognised as an artisan.)

Stage 9 - the trade test

Candidates who have completed their gap training and their evaluation or those who were considered competent and did not require gap training can submit themselves for the trade test. Currently, the trade test requires physical, face-to-face evaluation of the candidate by the trade test assessor. Using online platforms, however, may enable remote observation of the assessment by the assessor. An assistant will need to be present with the candidate.

Stage 10 - certification

Successful candidates are awarded their trade test certificate.

The process of certification has significant delays due to different platforms being used in addition to reporting requirements. However, using a common online system and processes will streamline and speed up this process.

As can be gleaned from the process above, each of these stages, except for Stages 9 and 10, has the potential to implement and use e-RPL processes. Some processes are already being used, while others have the potential to be seamlessly transferred onto an online platform. It is, however, important to critically evaluate the potential opportunities of e-RPL against the socio-economic realities of the digital divide. These include, inter alia, access to resources, Wi-Fi, technical support and funding.

In the context of this study, there is a difference between ARPL for the trade test and e-RPL. The ARPL process is specifically focused on assessing practical competence against specific occupational standards. As has been highlighted above, e-RPL, in contrast, focuses on using electronic, digital and mobile web technology to collect and record evidence of prior learning acquired either formally, non-formally or informally, or a combination of these. e-RPL can, however, be used to replace traditional face-to-face processes, although this nascent approach has yet to be implemented at scale in the South African TVET sector.

Findings: e-RPL in TVET - current form and extent

In the South African context, the use of e-Portfolios for RPL is still in its infancy but is growing (Davids et al., 2019). The use of e-Portfolios is increasingly evident in HEIs, whereas at TVET colleges RPL candidate portfolios are still mostly paper-based. Furthermore, research conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on TVET and other learning institutions (Papier, 2021) showed that a move to online platforms may affect the fairness of the assessment owing to the uneven access of candidates across the country to adequate connectivity and the high costs of data.

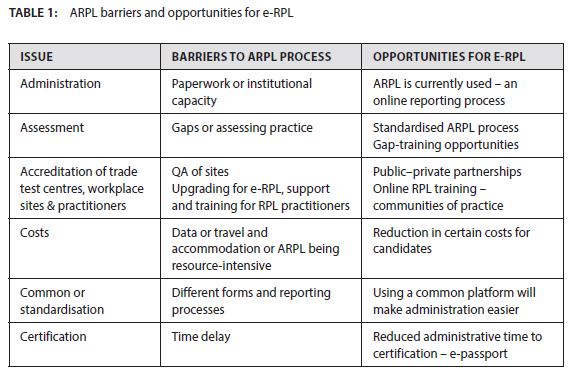

Based on the 2017 ARPL report findings and also the findings in the 2021 study highlighted in Table 1, the interviewee responses were grouped under six broad challenges. These are described below.

First, the respondents complained that the paperwork and administration were intensive and were especially challenging when administrative support was not available. Ten respondents in the 2021 study stated that particularly RPL in the trades required a great deal of administration to gather the necessary documentation for the PoE. For example, one practitioner stated that the ARPL process was very bureaucratic and that practitioners tend to go overboard regarding RPL compliance issues.

It was also noted that there was a long turnaround time between the test being done and certification, which was damaging to the industry and demotivating for the candidate. Apparently, the delays are caused during the processes which are dependent upon the trade test centre involved, the National Artisan Moderation Body (NAMB), and the QCTO which awards the certificate. The suggestion was that these administrative processes should be performed online, including the development of candidates' e-Portfolios of Evidence.

Second, current ARPL assessment practice is a time-consuming, resource-consuming and resource-intensive process. Sixty per cent of the respondents in the 2021 study believed that the self-assessment part of the ARPL could be completed at home on a computer or a smartphone and emailed back.

One college respondent noted that the self-assessment component of the ARPL processes required the candidate to be physically present. This required them to take a day off from work to go and complete the assessment. He asked: 'Why can't he (the RPL candidate) do it at home on his computer or on his smartphone and mail it to me and I can check it?' Doing so would reduce the time lost at work for candidates while also reducing the costs of assessment.

Third, as with assessment, the quality assurance and accreditation processes are intensive. It was also acknowledged that, along with the increasing use of technology in the automotive and welding industries, there was a need for public TVET colleges and their workplace counterparts to adapt the curriculum to meet the new competency benchmarks.

In this context, the use of digital platforms would require RPL practitioners to develop new strategies to train, support and assess candidates and would require their institutions and/or training academies to support such initiatives.

Fourth, as noted previously, costs were an inhibiting factor, and the view was expressed that these could be reduced through online/e-RPL means.

A college RPL practitioner argued that ways need to be found to make it easier for candidates to complete the ARPL process. Echoing the examples given by other respondents, he stated that candidates were forced to leave his panel shop to go and complete the ARPL process. While he acknowledged that the candidates must be exposed to the requirements for the test, it nevertheless means that they are away from their work for a considerable time, which means a loss of income, yet they must pay for the test.

Components of the ARPL process, such as the preparation of the e-Portfolio, could be completed at home on a computer or a smartphone and sent back to the RPL practitioner. This modus operandi would reduce the time lost at work for candidates while also reducing the costs of assessment.

Fifth, the view was expressed that having a standardised ARPL in place would allow for the shift towards a more online environment.

A respondent noted that all the trade test centres would need to be 'linked to a server, a central server and the trade test tasks generated via the computer' as a means of quality assuring the process and streamlining the ARPL process in particular.

Furthermore, some concerns were expressed about moving RPL assessment entirely to a digital platform, since it was said that this may have an impact on the way in which assessment is implemented. Concern was also expressed about the fairness of the assessment owing to the unevenness of Internet access and the cost of data for candidates from diverse socio-economic groups. In addition, RPL candidates with limited levels of digital literacy would need to be supported on such platforms. It was mentioned, moreover, that, for artisans, evidence of competence resides mainly in their demonstration of practice.

Finally, linked to the discussion on administration was the matter of certification. In this context, it was noted by several stakeholders that there was a need for a common platform for reporting to various assessment bodies and regulatory authorities. The timeous issuing of the trade certificate was viewed as critical by respondents, as was the recognition of the trade certificate by industry. Thirteen per cent of the respondents in the 2021 study stated that RPL needed to be more widely advertised in the community and especially in industry. One respondent stated that it was important to work with the community entities and formations, but that this did not always work in practice. He suggested the use of digital platforms to reduce the administration of RPL and for advocacy of RPL.

Table 1 offers an overview of the ARPL barriers stated in the 2017 and 2021 research on ARPL and opportunities for the use of e-RPL presented above.

Discussion - implications of e-RPL for TVET

In the article to this point, the concept of e-RPL and e-Portfolios and the way artisan RPL or ARPL is used in TVET colleges, have been considered. Consideration has also been given to the extent of its implementation in TVET colleges.

Feenberg (1991) argues that the CTT highlights the need to bring the substantivist use of technology closer to its developmental aims. In the context of e-RPL, it means the use of technology that is accessible and supportive of students, particularly in the rural and poor communities where there is limited connectivity and data costs are high. Widely used platforms such as Google, Teams, Zoom and WhatsApp and mobile phones could be harnessed instead to facilitate access.

Although e-RPL can enable a larger group of candidates to access RPL services, particularly from the rural communities, support is still needed (Davids et al., 2019; Ligale, 2023). This includes assisting and counselling candidates in preparing their PoE. This ties in with the constructivist developmental view expounded by the CTT (Feenberg, 2019).

The online e-RPL process adds another andragogical layer to the RPL practised by the practitioner. Cooper et al. (2016) have argued that RPL is a specialised pedagogy requiring practitioners to apply a broad range of teaching and assessment methodologies to ensure that the often tacit or hidden knowledge and skills of the candidate become explicit. Several authors, including Softic et al. (2013), Cameron, Travers & Whihak (2014), Davids et al. (2019) and Ligale (2023), allude to the role of the RPL practitioner in applying a similar process when using technology in RPL. Softic et al., for example, note that

[t]eachers also need a tool, support (technical and pedagogical) and students who will want to use it. Teachers also must be aware and prepared that implementation of new tools and new methods of teaching require significant amount of time and effort in the beginning (2013:2).

Certain forms of RPL lend themselves to the use of online technology. For example, the PoE in the form of e-Portfolios and online interviews is being used regularly at institutions. Practical RPL assessment requires candidates to be observed by the RPL practitioner or assessor via video link while the RPL assistant is available at the remote centre to assist the candidate.

Resourcing continues to be a perennial challenge, one of balancing the importance of creating access to and reducing the cost of RPL. In the e-RPL context, this means having access to the appropriate equipment and resources at the college or institution where the candidate can be assisted.

The literature increasingly recognises the specialised role of RPL practitioners in the assessment process (Ralphs, 2012; SAQA, 2019). Consequently, several policy documents have considered the training and development of these practitioners - for instance, the SAQA National Policy on RPL (2019) proposed that it would be necessary for Quality Councils to provide for 'supporting the training and monitoring of RPL practitioners including RPL advisors, facilitators, assessors, moderators, and administrators' (2019:12). According to the SAQA (2019) National Policy document, the RPL practitioner is

a person that functions in one or more aspects of RPL provision, including policy development, advising, portfolio course design and facilitation, assessment, moderation, administration, monitoring and evaluation, research and development (2019:5).

The continuing development of RPL practitioners was also recognised in the DHET National RPL Policy (2015) document that argued for the professionalisation of RPL practitioners through a professional body and for a register for all RPL practitioners in terms of which they would receive support to grow their technical knowledge and skills in order to implement and improve RPL practices (2015:13).

Conclusion

This article sought to answer two questions: (1) What, if any, are the current practices of RPL in the public TVET sector? and (2) What are the potential barriers to and opportunities when implementing e-RPL at public TVET colleges? It has been found through interviews, observations and a review of the literature that the current practice of RPL is more standardised with the implementation of common RPL toolkits. The application of these toolkits is technicist and focuses on the application of core competencies based on the trade rather than on the critical competencies needed for the 4IR. It has also been found that e-RPL has mostly been focused on the administration of ARPL but not on the process.

Activity Theory highlights the role of practitioners and is the mediating tool relevant to this study. The theory stresses the need for the RPL practitioner to be flexible in their approach to assessing the competence gained in the workplace and in their application of the mediating tool. The dangers of a solid disciplinary boundary is evinced in the narrowness of the assessment. The mediating tool therefore needs to be flexible, allowing the RPL assessor to consider broader notions of competence. This creates the tension between technology as a primarily human process in an activity system process and in raising contradictions and tensions in the interface between technology and human beings.

CTT cautions that technology, while possibly broadening access to opportunities, is neither apolitical nor value-free. It is important that the digital divide in the context of e-RPL be dealt with by providing the bridges suggested in the recommendations to ensure access to, and redress for, ARPL candidates. It is also important that technology should facilitate and accommodate varying learning and assessment styles.

Finally, the post-COVID-19 period challenges mentioned at the start of this article mirror the experience of those involved in RPL and at the public TVET colleges and in private workplaces. In this context, e-RPL holds promise as a means of expanding RPL access and provision at times when physical contact is curtailed. However, this promise of e-RPL needs to be tempered by the realities affecting many potential candidates, including unequal and costly access to digital resources.

REFERENCES

Bhorat, H, Lilenstein, K, Oosthuizen, M & Thornton, A. 2020. Structural transformation, inequality, and inclusive growth in South Africa (No. 2020/50). WIDER working article.

Cameron, R. 2012. Recognising workplace learning: The emerging practices of e-RPL and eePR. Journal of Workplace Learning, 24(2):85-104. [ Links ]

Cameron, R & Miller, A. 2014. Case studies in e-RPL and e-PR. Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 54(1):89-113. [ Links ]

Cameron, R, Travers, N & Wihak, C. 2014. Technology and RPL. Handbook of the recognition of prior learning. Adelaide: Torrens University. [ Links ]

Chan, S. 2022. Recognition of current and prior experience in Aotearoa New Zealand and the role of e-portfolios. In: International handbook on education development in Asia-Pacific. Singapore: Springer Nature. [ Links ]

Cole, M, John-Steiner, V, Scribner, S & Souberman, E (eds). 1978. LS Vygotsky. Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Cooper, L., 1998. From 'Rolling Mass Action' to 'RPL': The changing discourse of experience and learning in the South African labour movement. Studies in Continuing Education, 20(2):143-157. [ Links ]

Cooper, L. 2014. Towards ex-centric theorizing of work and learning. Journal of Workplace Learning, 26(6/7):474-484. [ Links ]

Cooper, L, Ralphs, A, Cooper, L, Deller, K, Harris, J, Jones, B & Bofelo, M. 2016. RPL as specialised pedagogy. Towards a conceptual framework. In: L Cooper & A Ralphs (eds), RPL as specialised pedagogy: Crossing the lines. Cape Town: HSRC Press. [ Links ]

Davids, YD, Chetty, K, Nomdo, A, Leach, N & Foiret, J. 2019. Online pilot test: Recognition of prior learning (RPL) instrument. (Report commissioned by the Unit for Applied Law, Faculty of Business and Management Sciences, Cape Peninsula University of Technology (CPUT). Cape Town: HSRC Press. [ Links ]

DHET (Department of Higher Education and Training). 2011. National Skills Development Strategy III. Pretoria: DHET. Available at: <http://www.info.gov.za/> [ Links ].

DHET (Department of Higher Education and Training). 2013a. Trade Test Regulations 2013. Pretoria: DHET. Available at: <http://www.fpmseta.org.za/> [ Links ].

DHET (Department of Higher Education and Training). 2013b. Ministerial Task Team on a National Strategy for the Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL). Final report incorporating a proposal for the national implementation strategy. Pretoria: DHET. [ Links ]

DHET (Department of Higher Education and Training). 2013c. White Paper on Post-School Education and Training. Pretoria: DHET. [ Links ]

DHET (Department of Higher Education and Training). 2015. Draji Policy on Artisan Recognition of Prior Learning. Pretoria: Government Printer. Available at: <http://www.gov.za/sites/www.gov.za/> [ Links ].

DHET (Department of Higher Education and Training). 2016. National Recognition of Prior Learning Coordination Policy. Pretoria: DHET. [ Links ]

DHET (Department of Higher Education and Training). 2017. Criteria and Guidelines for the Implementation of Artisan Recognition of Prior Learning. Pretoria: DHET. [ Links ]

DHET (Department of Higher Education and Training). 2023. National Plan for Post-School Education and Training. Pretoria: DHET. [ Links ]

DHET (Department of Higher Education and Training). 2024. Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL) Implementation Framework in the Post-School Education and Training (PSET) System. Pretoria: DHET (For public comment). [ Links ]

DoL (Department of Labour). 1981. Manpower Training Act 56 of 1981. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Engestrom, Y. 2001. Expansive learning at work: Toward an activity theoretical reconceptualization. Journal of Education and Work, 14(1):133-156. Available at: <http://doi.org/10.1080/13639080020028747> [ Links ].

Feenberg, A. 1991. Critical theory of technology (Vol 5). New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Feenberg, A. 2008. Critical theory of technology: An overview. Information Technology in Librarianship: New Critical Approaches, 31-46.

Harrisberg, K & Mensah, K. 2022. As young Africans push to be online, data cost stands in the way. London: Thomson Reuters Foundation. Available at: <https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/06/as-young-africans-push-to-be-online-data-cost-stands-in-the-way/> [ Links ].

Ligale, LM. 2023. Development of a new model for an e-RPL system quality evaluation: A case study of Kenya Technical Trainers College. Africa Journal of Technical and Vocational Education and Training, 8(1):38-51. [ Links ]

Loots, S & Butcher, MN. 2021. Aligning post-school education and training (PSET) and the National Qualifications Framework (NQF): Potential and challenges in the age of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR). SAQA BULLETIN.

Naudé, L. 2016. Rethinking the role of RPL assessment within an interactive activity system. PLA Inside Out: An International Journal on Theory, Research and Practice in Prior Learning Assessment 5. [ Links ]

OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development). 2021. Implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for vocational education and training.. Paris: OECD Publishing. [ Links ]

Papier, J. 2021. 21st century competencies in technical and vocational education and training: Rhetoric and reality in the wake of a pandemic. Journal of Education (University of KwaZulu-Natal), 84:67-84. [ Links ]

QCTO (Quality Council for Trades and Occupations). 2014. Policy for the Recognition of Prior Learning. Pretoria: QCTO. [ Links ]

Ralphs, A. 2012. Exploring RPL: Assessment device and/or specialised pedagogical practice. Journal of Education, 53:75-91. [ Links ]

Softić, SK, Pintek, TIP Martinović, Z & Bekić, Z. 2013. Use of the e-Portfolio in the educational process. EUNIS 2013 Congress Proceedings, 1(1).

SAQA (South African Qualifications Authority). 2019. National Policy for the Implementation of the Recognition of Prior Learning. Pretoria: SAQA. [ Links ]

Stojanovska-Georgievska, L, Sandeva, I, Krleski, A, Spasevska, H & Ginovska, M. 2023. Digitalisation of the process of recognition of prior learning: The concept of e-RPL tool. In: IATED. ICEPI2023 Proceedings (9059-9069).

The Presidency. 2012. National Development Plan (NDP) 2030 - Our Future, Make It Work. Pretoria: National Planning Commission. [ Links ]