Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

African Human Mobility Review

On-line version ISSN 2410-7972Print version ISSN 2411-6955

AHMR vol.11 n.2 Cape Town May./Aug. 2025

https://doi.org/10.14426/ahmr.v11i2.2870

ARTICLES

Cross-Border Solidarity: Migrant-Led Associations as Spaces of Epistemic Resistance and Food Security Innovation in South Africa

Perfect Mazani

Doctoral candidate, Institute for Social Development, the University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa. Corresponding author. 3934785@myuwc.ac.za; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4700-6026

ABSTRACT

In the midst of closure and securitization of border regimes, climate-change displacement, and entrenched inequalities, migrant communities are not just surviving but creating new sites of resistance, creativity, and adaptation to their worlds in crisis. This paper explores how migrant-solidarity organizations function as epistemic spaces of invention and resistance in South Africa among Zimbabwean, Pakistani, and Cameroonian migrant communities in Parow Valley, Summer Greens, and Kensington (Cape Town). Based on 250 household surveys and 12 qualitative in-depth interviews, the paper explores how migrant-led social movements become sites of agency, social resilience, and resistance to marginalization habitually employed by state policy and academic scholarship. These forms of solidarity networks, which are essentially national in scope, maintain food security at a household level, access to livelihood, and socio-emotional well-being. Group savings, mutual support, and rotating credit associations enable these networks to build adaptive capacities to deal with uncertain migration status and socio-economic risk. They constitute resilient, informal social safety nets for food, income, and affective resources that go beyond what formal mechanisms can provide. By situating migrant practice and epistemologies, the paper challenges hegemonic discourses that position migrants as passive. Instead, it positions everyday solidarities at the site of politicized invention and resistance. It situates where these practices intersect with Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2 (zero hunger), SDG 8 (decent work), and SDG 10 (reduced inequalities). It establishes a decolonial, plural migration knowledge positioning migrants as co-producers, policy entrepreneurs, and change agents.

Keywords: migration research, solidarity economies, food safety, epistemic justice, migrant agency, decolonial praxis, South Africa, SDGs

INTRODUCTION

Migration is increasingly grasped less as the movement of individuals from one point to another but as a complex, sociopolitical phenomenon determined by power relations, borders, and global inequalities. As the increase in restrictive border regimes persists, global climate change effects become more pronounced, and socio-economic disparities grow larger, the dominant debate on migrants continues in large part to focus on their vulnerability and dependency (Crush, 2001; Moyo, 2024). This structure, however, ignores the agency, resilience, and creativity of migrant populations, especially in South Africa - one of the major destination countries for migrants in the African continent (Hlatshwayo and Vally, 2014; Ncube and Bahta, 2022).

Migrant populations, typically marginalized in receiving countries and in global narratives as a whole, are mobilizing in solidarity groups as critical spaces of collective care-making, knowledge production, and social resistance (Awumbila et al., 2023). These solidarity masses, which are highly organized along national lines, are key to addressing the full range of migration challenges, notably food security, marginalization from formal livelihoods, and marginalization from state welfare regimes (Pande, 2020). Anything but minimalist survival tactics, these masses are sites of epistemic resistance that actively challenge prevailing hegemonic discourses of migration and development. They are sites at which migrant-led knowledge systems flourish, yielding practical answers to the universal dilemma of migrants and, in the process, constructing transnational solidarities beyond the expectations of the state and the academy (Pande, 2012).

This paper discusses how such migrant-led solidarity organizations function as spaces of agency, resistance, and innovation. It draws on empirical evidence from Kensington, Summer Greens, and Parow Valley (Cape Town), where Zimbabwean, Pakistani, and Cameroonian migrant groups pursue different forms of collective action in response to food insecurity and promote socio-economic activities. This research resists the prevalent imagining of migrants as passive recipients of provision or victims of migration policy. Rather, it highlights their role as strategic agents of knowledge production and innovators in the establishment of food security.

This paper contends that while contemporary migration is driven by world inequalities, climatic factors, and increasingly militarized borders, hegemonic accounts frame migrants as weak, helpless, and in need of humanitarian intervention. However, these negative images are shrinking and one-dimensional. This research counters the dominant narratives by foregrounding migrants' agency and collective resilience. It argues that migrant-organized solidarity groups are not merely survival strategies but sites of successful resistance, invention, and knowledge production. The paper re-maps migration as a deeply political and epistemic practice, rooted in the generally mundane practices of resilience, mutuality, and world-making.

Drawing on the relevant literature, this paper contributes to the critical scholarship on migrants in South Africa by examining how migrants use resilience practices of solidarity, collective agency, and social innovation to challenge the hegemonic accounts of passivity and dependency. In a mixed-methods investigation of migrant associations in Cape Town, this paper tracks how migrants counter structural exclusion and reshape their socio-economic realities, staking their claim to belonging. In so doing, the paper contributes to the body of knowledge by making visible the interface of food security interventions, collective agency, and epistemic resistance in South African migrant-led solidarity spaces.

RESEARCH APPROACH

The research used a mixed-method design, incorporating qualitative and quantitative methods in analyzing migrant-organized solidarity group practices, networks, and systems of knowledge. This is consonant with the study conceptualization with regard to the possibility of the simultaneous exploration of both the material realities (e.g., the outcomes of food security) and the epistemic dimension of migrant lives -how migrants create, share, and act on their own knowledge sets to make themselves heard and confront marginality (Fricker, 2007; Awumbila et al., 2023). Quantitative surveys mapped wider trends in food security and membership belongings, while qualitative interviews documented lived experience, cultural practice, and social innovation behind migrant solidarity. The mixed-methods design is thus not simply methodological, but epistemological - it turns mainstream knowledge production processes around by centering migrants' voices and practices as valid sources of knowledge and resilience.

The research was conducted in three Cape Town suburbs - Kensington, Summer Greens, and Parow Valley, which were chosen purposively, as they are home to high numbers of migrant communities, notably Zimbabweans, Pakistanis, and Cameroonians. The suburbs are therefore optimal to examine the intersection between migration, solidarity, and food security. Migrant communities in the suburbs are organized along either national or ethnic lines. The national or ethnic affiliations are spontaneous systems of governance and sites of living together, where everyday sharing of information, co-sponsorship, and survival mechanisms are enacted. These coping mechanisms are displays of epistemic agency, whereby the migrants counter the exclusion by creating alternative systems of knowledge and belonging.

Fieldwork and data collection

The research employed a mixed-methods design for the 6-month study period. While the quantitative data constituted a 250-household-survey of migrant livelihood access, food security, and membership in the association, the qualitative data involved 12 in-depth interviews with leaders and members of the association. The research team also carried out participant observation during association meetings, savings meetings, and food-sharing activities.

The sample consists of 250 migrant families, purposively selected to give a representative sample of diverse migrant experiences and socio-economic statuses. The sample was heterogeneous by age, gender, and migration history, with a first-priority selection of current affiliated solidarity association members. The research team conducted in-depth interviews with 12 important informants that included solidarity association leaders, community organizers, and key members of the association to determine their roles and perspectives. Semi-structured interviews allowed the participants to provide their experiences and opinions on their own terms while also leading the interview into some areas like food security, mutual care, sharing knowledge, and community governance.

Furthermore, participant observation of group meetings, savings meetings, and community events enhanced the researcher's insights into how solidarity groups interacted. As an ethnographic procedure, the researcher could see firsthand how resources and knowledge were mobilized within these networks and how power, trust, and solidarity were negotiated.

Data analysis

Quantitative analysis

The study used descriptive and inferential statistical methods to examine the household survey data gathered from 250 migrant households. It used a statistical package (SPSS): (a) to calculate frequencies and percentages of significant variables such as food insecurity, income levels, family size, and association membership; (b) to create cross-tabulations to determine whether there were relationships between variables (for example, food security and association membership); (c) to use chi-square testing and logistic regression to determine whether migrant-led solidarity association membership had correlations with such outcomes as dietary diversity, meal frequency, and household coping that were statistically significant. Additionally, the researcher gender-disaggregated the data to determine whether male-headed and female-headed households engaged differently with solidarity organizations.

Qualitative analysis

The researcher used thematic coding to analyze and code data from the 12 in-depth interviews and ethnographic fieldnotes using thematic coding. To code repeated themes throughout the data set, the researcher employed NVivo (or manual coding). Thematic categories included:

• Food security practices: Community cooking, food-sharing practices, community gardens.

• Mutual aid and care: Emotional support, emergency lending, shared childcare.

• Epistemic practices: Knowledge sharing, traditional farming practices, language bridging.

• Resistance and agency: Advocacy work, storytelling as resistance, symbolic actions of cultural preservation.

The research team then analyzed these topics alongside the broader literature on epistemic justice, solidarity, and migration. Furthermore, the study used epistemic justice-informed interpretative theories to observe how everyday practices are resistance performances and knowledge construction. The researcher also reflected on how closely such bottom-up practice aligns to international development paradigms and specifically the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Ethical issues

Ethical concerns were a top priority at every point in the research process. The researcher informed the subjects adequately with regard to the purpose, procedure, and potential risks of the research and reassured them of their anonymity and confidentiality. The research team endeavored to ensure all participants' awareness of the study's aims and objectives and made efforts to hear the silenced groups, particularly women and poor migrant people. Since the research deals with sensitive issues related to migration, vulnerability, and legal status, it was imperative to create a non-judgmental and empathetic research environment. The University of the Western Cape's Ethics Committee approved the ethical requirements of the study. The research team obtained informed consent from all the participants and maintained the protection of confidentiality, anonymity, and voluntariness during the study.

MIGRATION AND SOLIDARITY IN SOUTH AFRICA

South Africa is a centuries-old host of migrants from across the African continent and beyond (Owen et al., 2024). Its comparative prosperity, job openings in the urban towns, and historic connections with the surrounding countries have rendered it a welcoming host to immigrants in search of enhanced livelihood. However, South Africa's xenophobic, restrictive immigration policies involving control of its borders and exclusion of foreigners have contributed significantly to the production of precariousness for migrants (Mazani, 2022). Exclusionary space and heightened levels of record unemployment, poverty, and inequality have compelled migrants to survive on their own networks and resources.

In this context of hardship, solidarity associations of migrant communities have served as lifelines. These networks, often operating along national or ethnic lines, form the basis for a range of solidarity activities, such as informal savings schemes (e.g., rotating credit associations), mutual assistance in food and healthcare dispensation. They are particularly important in the case of food insecurity, itself commonplace among migrants, since they have limited access to formal employment, social welfare, and housing. Along with material support, they are also a space of social solidarity and emotional warmth that allows the migrants to belong and feel integrated into the host society.

Migrant epistemologies and resistance

Epistemic resistance is courageous and deliberate in opposing unjust, oppressive social and epistemic norms, particularly when few others have similar intentions or with whom one is in resistance (Beeby, 2012). It is resisting powerful systems of knowledge that disempower or misrepresent particular groups and claim other ways of knowing and being. This type of resistance is a matter of resisting the structures and practices on which epistemic injustice relies like silencing, disentitlement to knowledge-making processes, and being on the periphery and undervalued (Medina, 2013).

Migrant epistemologies' creation, dissemination, and use of knowledge by the migrants in their everyday lives are at the core of migrant-solidarity associations. These epistemologies are fashioned by migrants' everyday lives and the imperative to navigate more than one, and sometimes contradictory, sociopolitical space (Safouane et al., 2020; Ríos-Rojas et al., 2022). Migrants generate practical knowledges of survival, resource management, and making community into their everyday lives (Hlatshwayo and Wotela, 2018; Mazani, 2022). This is disseminated informally along lines of kinship, social networks, and shared practice and is a counter-hegemonic knowledge that challenges the dominant discourses about migration as a linear and one-way process of loss and exposure.

Migrant-solidarity groups thus are spaces of epistemic resistance, where systems of counter-knowledge and practice are not only preserved but actively fostered (Awumbila et al., 2023). In organizing by shared needs and resources, migrants push against structural inequalities that deny them access to state provision and also against academic discourses that seek to represent migrants as passive victims (Pande, 2020). Through such organizations, the ability of migrant communities to innovate, adapt, and survive in the face of adversity is instead brought into view.

Migration, food security, and development

The role of migrant-solidarity organizations in reducing food insecurity is therefore pertinent to global development agendas as well. Food insecurity, so vital to migrants, since they are excluded from the formal economy and welfare states, is one of the most pressing problems in the Global South, according to Rugunanan (2022), but also among migrant enclaves in the Global North. By providing mutual support systems, group savings schemes, and food-sharing programs, such organizations provide realistic solutions to the challenges that hinder their members from accessing food at times of economic uncertainty.

For supporting the SDGs, notably SDG 2 (zero hunger), SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth), and SDG 10 (reduced inequalities), migrant-led programs are a sustainable, equitable, and community-driven model of development. Besides ensuring basic survival, they are the building blocks of long-term resilience that allow migrant populations to deal with the hazards of migration and build adaptive capacities in the face of socio-economic and environmental uncertainties.

LITERATURE REVIEW/THEORETICAL MODELS

Literature across food security, solidarity networks, and migration studies has increased exponentially in recent years, offering novel insights regarding how migrants can make sense of complex socio-economic situations (Rugunanan, 2022; Triandafyllidou, 2022). While much of the written academic literature has traditionally viewed migrants as victims, new research has focused on migrant agency, resilience, and creativity under difficult circumstances. This review integrates a range of theoretical frameworks and empirical research, no less focusing on migrant-led solidarity organizations, epistemic resistance, and food security in South Africa.

The criticism further reveals how these networks function not merely as survival tactics but as sites oftransformation that reorganize power dynamics, construct collective identity, and enable sustainable development. By connecting the micro-politics of migrant everyday life to broader structural injustices, the literature deconstructs the multifaceted nature of global migrant resilience and collective struggle.

Migration and solidarity networks

Migrant-solidarity networks are the focus of attention in migration studies because the networks expose this social and economic coping strategy used by migrants in host countries. Migration is not only an individual process but a social process in which the migrants use the social network for information, financial, and emotional support (Blumenstock et al., 2025). These networks are particularly significant for forced migration scenarios, in which migrants may be marginalized or discriminated against by state-provided services and may be marginalized from society. Solidarity networks are, in exclusion contexts, parallel social networks through which migrants may be autonomous and agentive. They arise out of historical migratory streams, kinship, and communing cultural practices that cut across borders.

The exercise of "solidarity" among migrant groups is a form of non-formal expression of solidarity, ranging from rotating credit clubs and savings associations to other forms of collective action. They are vital to their survival, according to Mazani (2022), as they enable access to resources that otherwise would be unavailable to the migrants due to their irregular status or due to not having access to the formal labor markets (Keles et al., 2022). In addition, solidarity networks can make migration shift from the forced to the collective agency form, which gives a sense of belonging and shared ownership (Awumbila et al., 2023). These networks yield social capital more than immediate economic returns, as arenas for the practice of citizenship, skills transfer, and the reproduction of culture. This is what makes solidarity a survival politics and political praxis that resonates in the context of dignity of migrants against xenophobia in host countries. In South Africa, in particular, a report by Mazzola and De Backer (2021) outlines how solidarity organizations provide vital services such as the supply of food, health treatment access, and legal aid to migrants.

These organizations are most vital among marginalized communities where government help is unavailable or inaccessible. In the same vein, Moyo and Zanker (2020) chronicle how migrant-based movements upset the state's hegemonic form of discourse on migration and make an argument about migrants being less reliant but rather stakeholders in their own right in their communities. These types of contributions continue to be unaddressed in hegemonic policy discourses that threaten to pathologize migration. However, in the logic extended by solidarity networks, migrants are assumed to be co-producers of local economies and social ecologies. Moreover, the adaptive capacity of these types of networks is better mobilized and culturally sensitive than that of state-led interventions and therefore critical to urban resilience strategy.

Food security and migrant economies

Food security is the greatest problem that confronts migrant communities, particularly in instances of economic marginalization. Food insecurity punishes migrant communities who may not have easy access to formal employment and social welfare systems. In South Africa, where poverty and unemployment are pervasive, migrants participate in the informal economy - in the majority of cases, as low-skilled and vulnerable labor (Dunn and Maharaj, 2023). This at-risk group has been behind the development of intricate food-sharing networks, most often headed by migrant women, who are primarily responsible for the care of much of the household's food and feeding. The women's activities form the backbone of most solidarity associations, in turn solidifying the feminization of food security and collective resilience.

Through his research, Olawuyi (2019) demonstrates that informal networks improve food security, particularly in times of economic crisis among Southern African communities. Migrants will typically pool resources using solidarity associations to ensure the members are provided for during times of hunger. Importantly, locally based food-sharing businesses and communal saving schemes can be accessed by migrants to purchase food in bulk; hence, the accessibility to everyone.

These social networks do not only respond to emergency food needs; on the contrary, they are also expressions of participatory economies as an alternative to neoliberal market culture. By organizing cooperation rather than competition, solidarity associations become platforms for alternative development paradigms anchored on equity and care.

The food security contribution of migrant-solidarity networks is also founded on the food sovereignty concept, which underscores people's rights to make choices about their own food systems. Byaruhanga and Isgren (2023) depict how food sovereignty challenges neoliberalism in food security by promoting local and community-based modalities. The South African migrant-solidarity groups, by their congregation food-sharing practice, are setting the example of such values, which serve as a strong and lasting counter-hegemony to state-led food security interventions.

This framing also situates migrant communities as not merely reactive but active actors constructing new geographies of food. These are based on cultural capital, seasonal repetition, and obligations to one another, thereby making localization and democratization of food possible. Migrant food economies are thus material and symbolic subversions, claiming presence, purpose, and permanence in otherwise hostile city spaces.

Epistemic resistance and knowledge production

Epistemic resistance is the act of resisting hegemonic ways of knowing and systems of power that marginalize specific groups (Frega, 2013). In the case of migration, epistemic resistance smashes the stereotypical role of migrants as recipients of assistance and instead situates them as knowing subjects that generate their knowledge. Migrant-organized solidarity networks are central epistemic sites of resistance, for they construct knowledge from the migrants' experiences and distinct ways of coping with displacement, marginalization, and economic insecurity (Awumbila et al., 2023). They are transmitted through narrative, ritual, body practice, and through everyday survival practice. These knowledges, though often ignored, still hold boundless explanatory and transformative power.

Epistemic justice is a term coined by Miranda Fricker (2007), who states that members of oppressed groups need their knowledge to be legitimated and authenticated; this theory is supported and underscored by Catala (2015). In the context of migration studies, it is important that the epistemologies, experiences, and survival strategies of migrant communities should be accepted as legitimate knowledge (losifides, 2016). This is a departure from hegemonic discourses on migration that rarely recognize migrants' existing knowledge, which they already possess or gain through their material objective conditions. Solidarity groups, in organizing spaces of collective learning and knowledge sharing, are such arenas where this epistemic resistance is invoked. These are unofficial sites of academies, where migrants negotiate structural imbalances, improvise new ways of earning a living, and challenge prevailing policy orthodoxy. Oral reservoirs and lived pedagogies that take place there form a counter-hegemonic epistemology - an imperative need of academic and policy universes.

Scholars such as Amelina (2022) and Celikates (2022) assert that the knowledge production of marginalized groups is not simply a survival strategy but a counter that repositions the locus of power. In ethnographic studies of the everyday lives of South African migrant communities, this research shows how such solidarity groups not only counter state and academic hegemonies but also construct new forms of knowing and being that shape wider political and social change.

This reshaping of migrants as epistemic agents puts at the forefront the politics of recognition and shifts the spotlight from deficiency to contribution. It also requires rethinking development praxis so that migrant priorities, knowledge, and understanding become the very core of policymaking and social transformation.

Theoretical models: Resilience and epistemic justice

This paper addresses two core theoretical models: resilience theory and epistemic justice. Resilience theory, used by Holling (2001) and others, is a foray into explaining how any system - ecological, social, or economic - operates resiliently toward stress and shocks. In the context of migration, resilience theory provides a tool for examining how migrant communities react with adaptive responses in conditions of exclusion, marginalization, and environmental pressure. Migrant-led solidarity organizations exemplify the resilience model because they enable migrants to act in concert against the pressures of migration by sharing resources and supporting one another (Barglowski and Bonfert, 2023). They construct useful anticipatory forms of resilience whereby communities do not merely react to crises but actually prepare to engage positively with latent uncertainty. This temporal aspect of resilience is pertinent where structural exclusion is ever-long-term and cyclical instead of episodic.

Epistemic justice enables subordinated groups to participate in the creation of knowledge (Fricker, 2007). Via a case study of migrant-led solidarity associations, this study demonstrates how these groups create new, productive knowledge that can be harnessed to shape broader social, political, and development practice. By integrating the two lines of thought, this paper considers how resilience and epistemic justice are conversely balanced in the context of migrant-solidarity organizations in South Africa. Resilience is not only material or social adjustment, but the act of regaining the ability to voice one's definition of experiences and responses to adversity (Folke et al., 2010; Ungar, 2011). Migrant associations practice anticipatory resilience through the creation of their own knowledge systems, strategies, and narratives - through epistemic resistance and advocacy for epistemic justice (Fricker, 2007; Dotson, 2011). Resilience is practiced both as a survival and knowledge-production process. It is here that various discourses of belonging, community, and development are created collectively among migrants outside of state or humanitarian dominant discourse (Medina, 2013; Barglowski and Bonfert, 2023).

These two theories were chosen over other perspectives because they capture both the structural and the epistemological dimensions of solidarity among migrants. Resilience theory captures how migrant societies adapt and endure in the face of system shocks (Holling, 2001; Berkes and Ross, 2013), while epistemic justice captures the importance of voice, recognition, and knowledge de-hierarchization (Fricker, 2007). Combined, they provide a general idea of how migrant organizations manage to survive but, in fact, recreate their social worlds and redefine marginalization on both a practical and a theoretical basis (Maldonado-Torres, 2016; Awumbila et al., 2023).

RESEARCH FINDINGS AND INTERPRETATION

Field research among 250 migrant families and 12 in-depth interviews conducted in Parow Valley, Summer Greens, and Kensington (Cape Town) produced a number of important findings concerning the role of solidarity associations in solving food insecurity, community resilience, and knowledge production. Qualitative findings indicate the importance of bottom-up movements within the migration process to change migrants from being passive victims to showing their capacity and agency to take control of their situation to organize themselves. The way in which migrantled initiatives are not only reactive but also highly adaptive and initiative-taking in becoming systems-based on cultural origins and visionary planning is a testament to their work as transformative agents in the development of alternative economies and community resilience.

The quantitative aspect of the study revealed that 68% of the interviewed households were food insecure and ranged from being moderately to severely food insecure. Within the households, those with membership in solidarity associations were three times more likely than those without membership to report having access to stable meals and diversified diets. Female-headed households indicated greater use of shared food systems and savings groups.

The intersecting and multiple data from the three research sites provided a rich perspective on how migrants react to exclusionary systems and rebuild social infrastructures with collective power. The study brings to the fore how such migrant communities operate at the nexus of innovation, solidarity, and survival and build resilience microcosms in the face of marginalization.

Food security and solidarity associations

The strongest finding of this research is the pivotal role played by solidarity associations in alleviating food insecurity among migrants. The research revealed that about 80% of the families interviewed relied on some form of collective food-sharing mechanism, either institutionalized group savings associations or group savings associations. These mechanisms allowed the migrants to pool resources and get food at a reduced cost, and even the most vulnerable members of society were able to fulfill their food needs.

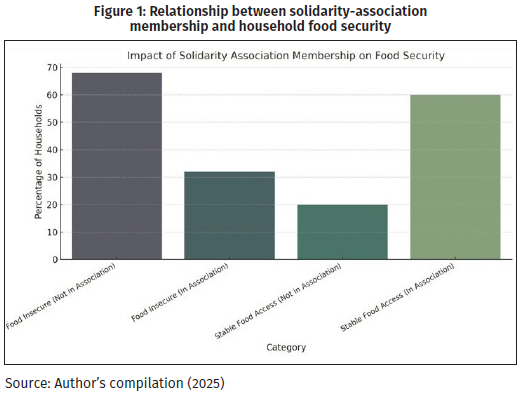

Quantitative evaluation of 250 migrant families, as shown in Figure 1 reported 68% of the households to be experiencing chronic food insecurity, and members of the association were significantly likely to have regular access to meals. Membership in the association was strongly associated with more varied diets and frequency of meals by chi-square analysis (p < 0.05). Logistic regression made association membership to be three times as probable to have regular access to food. Female-headed households, according to gender-disaggregated figures, had a greater level of participation in solidarity associations. Cross-tabulations further revealed the direction of the fact that low incomes were linked with greater dependency upon such networks. Overall, the evidence confirms the statistically significant impact of migrant-led associations for better food security outcomes.

The prevalence of the practice is a signal of a larger community culture where the well-being of the many takes precedence over survival at the individual level. Food-sharing arrangements were not charitable acts but institutionalized social agreements grounded in reciprocity, trust, and responsibility. The migrants outlined how the networks facilitated security, dignity, and belongingness as crucial psychosocial cushions in the face of an oppositional sociopolitical environment. For others, the relationship provided a surrogate welfare system providing some security and relief unavailable in official state structures.

Migrant-solidarity associations are created as a form of social protection and security in host countries by migrants as safety nets due to the exclusion of these migrants from the host country's mainstream economy and social services (Barglowski and Bonfert, 2023). Apart from food-sharing programs, the majority of solidarity associations also undertook group purchases of staple foods that were handed out to members within routine periods. This was particularly common among Zimbabwean migrants, who reported being more exposed as regards food, since they lacked official employment and state welfare.

Within the migrant-solidarity associations in this study there were bulk-buying programs. Such buying programs were typically funded through capital raised collectively by revolving savings associations; hence, members had reduced costs at the market and paid less for transport. Occasionally, associations would hire local wholesalers on direct contract, both signing terms that were favorable to their respective interests. Quite often, choices about bringing the food to members would be collaborative, involving committees or elected delegates organizing planning and making access available, thus helping to extend principles of transparency and participatory democracy.

The roles played by solidarity associations extend beyond social belonging; these are instrumental support networks that enable members to navigate exploitative market relations and buffer themselves from the volatility of food prices. Through resource pooling, information exchange, and mutual support, the associations create shock-absorbing buffers that insulate migrant households from both immediate economic shocks and food insecurity.

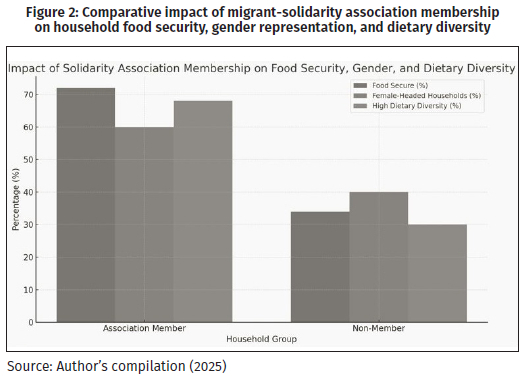

Figure 2 shows percentage disparities between solidarity association members and non-members for three indicators: food security, representation of female-headed households, and high dietary diversity. The results are that membership in the solidarity association is associated with increased food availability, increased representation of female-headed households, and increased dietary diversity.

Knowledge production and epistemic resistance

The second profoundly important finding is that the solidarity associations organized by migrants are spaces of epistemic resistance. From the interviews conducted, the associations were not only spaces of material assistance but also spaces of knowledge exchange and innovation. The migrants revealed that they would usually share tips on work opportunities in the region, accommodation, and legal rights, among others, with coping mechanisms for managing climate stressors such as flooding and drought.

These knowledge exchanges were consistently facilitated by meetings, WhatsApp groups, casual mentoring, and skills-sharing workshops. This assisted these organizations in facilitating codification and sharing of experiential, actionable, and experience-based place-specific community-based knowledge that they had earned. These migrants did not have to rely on outside agents for information; rather, they created their own epistemic infrastructure that was more adaptive and efficient in meeting their needs.

These solidarity networks also facilitated the passing on of survival and cultural wisdom, whereby several generations passed on food-preserving methods, knowledge of agriculture, and savings practices. This sharing of knowledge processes, too often overlooked in mainstream texts on migration, highlights the migrant as a knowledgeable producer of knowledge who reconstructs their future through learning and reciprocal aid.

In these solidarity associations, older women in particular became central to intergenerational learning as seed-saving experts and trainers in herbal medicine, but more significantly, as the depository for cooperative food-cooking practices. They were not merely caregivers but epistemic and cultural anchors whose labor supported the reproduction and innovation of food habits in new environments. Highlighting their lives, this study discloses gendered aspects of epistemic resistance, which were typically hidden from view within male-stream accounts of migration.

Moreover, these networks were also informal campaigning spheres, where migrants could document their past and share complaints. This in itself was political narrative, establishing individual sufferance, collective memory, and mobilization. As they gained traction, these narratives started subverting institutional imaginings of migrants as voiceless and inarticulate. Instead, they were a diverse and changing population with the capacity to think strategically, mobilize support, and develop political awareness.

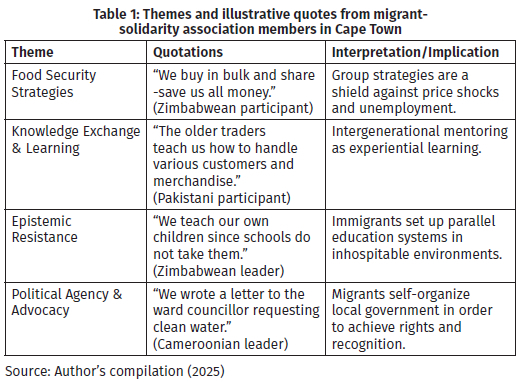

Table 1 summarizes the dominant qualitative themes of 12 in-depth interviews and participant observation of Zimbabwean, Pakistani, and Cameroonian migrants involved in grassroots solidarity initiatives in Cape Town. The themes are located within the practical, epistemic, and political functions of the organizations, covering food security programs and intergenerational knowledge sharing to modes of resistance and counter-education networks. All the themes are supplemented with direct quotes from the participants and analyzed to illustrate the contribution of the associations in the development of resilience, self-organization, and daily activism.

The table shows that migrant-led organizations are not only sites of support but also sites of epistemic resistance and political engagement.

Agency and resistance

According to this study, migrant-led solidarity groups were established as powerful voices of resistance against state policy and hegemonic migration discourses. In their collective action, these groups counter the migrant story of passive victimhood or being mere recipients of assistance. Instead, they create affirmation of the agency of migrant groups in fashioning and shaping their own survival strategies, along with resisting for greater social inclusion and recognition. Their collective effect includes collective mobilization of resources in rotating savings associations, labor exchange in hidden food economies - like communal cooking and street vending, and mutual sharing of communal knowledge - like seed-saving, herbal medicine, and cooperative childcare. Beyond allowing room for survival, these groups create solidarity economies and reproduce social networks at the core of resilience.

This is a three-dimensional resistance - economic, social, and epistemic. Migrants resist not only by protest but by everyday practice of survival, redefinition of community, and assertion of their right to belong. Different associations formed alliances with local civic society organizations, religious institutions, and sympathetic policymakers to struggle for changes in housing, documentation procedures, and access to health care. They acted as proto-political institutions, training their members to become citizens and social activists. According to Mottiar (2019), in South Africa, Durban protests were accompanied by more concealed, ordinary resistances. The migrants and dispossessed populations sometimes express themselves through visible protests, primarily in opposition to extreme grievances such as xenophobic attacks or harassment from the police. Shack dwellers, for example, practice protest as a routine and culturalized form of resistance. However, most migrants and undocumented workers such as street vendors employ predominantly "everyday resistance" - less audible, less explicit acts challenging power relations through everyday survival strategies without challenging the authorities. This is three-dimensional resistance -economic survival strategy, social redefinition of community, and epistemic claims to membership - with protest as important but not the sole mode of resistance.

In interviews, some migrant leaders described a desire to connect their networks with other networks and to campaign for policy change that would bring benefit to the overall health of all migrants, not just those directly around them. These findings bring to the fore the political significance of action led by migrants and how it can potentially be an input in broader discussions surrounding the management of migration, food security, and social justice.

These hopes are solidarity-based aspirational politics rather than the struggle for mere survival. The migrant leaders articulated visions of just city planning, democratic policymaking, and the acceptance of their organizations as legitimate actors in development. Their struggle for food justice, access to land, and decisionmaking at the local level highlight the intersectionality of their struggle as bridging migration with discussions of democracy, equity, and human rights.

These groups' material and symbolic practices intersect to produce what scholars such as Piacentini (2014) refer to as "everyday resistance" practices that are mundane but with the potential for transformation. Through the establishment of community gardens, rotating credit associations, or schools, these practices refuse exclusionary models and posit a model for more just urban potentialities.

Migrants introduce intergenerational knowledge and skills that challenge exclusionary regimes as well as hegemonic discourses. Pakistani businesspeople, for instance, are prepared to transfer entrepreneurial as well as survival skills to second-generation migrants to hand over to the third generation. Zimbabwean diaspora in South Africa, once more, since they are not documented and hence cannot offer access to public education to children of the migrants, have devised their own education system. Some of the schools offer the Zimbabwe School Examinations Council (ZIMSEC) curriculum and provide students with a chance to sit for final examinations in Zimbabwe, while others run Cambridge programs. These "solidarity schools," as they are otherwise known, provide unofficial learning such as language, budgeting, and work-skills training. These are examples of epistemic resistance: migrants making and disseminating knowledge outside formal state-directed systems themselves. Migrant associations are therefore not only survival networks, but knowledge-generating fields and political struggle sites. They build other knowledges from experience on how to get around, how to survive on savings in exclusionary economies, and how to access education in the midst of structural exclusion. In this way, migrants position themselves as epistemic actors in themselves - knowledge-making intentionally relevant to development, food security, and justice. These everyday acts of caretaking, narrative, networking, and advocacy are small acts of resistance against the dominant discourse that attempts to portray migrants as needy and powerless.

As this study illustrates, resistance of this kind is not oppositional but rather reconstructive; migrants are constructing alternative care and support systems that compensate for systemic failure. This has significant practice and policy implications, contending that migrant communities need not only to be consulted but need to be actively included in urban government and food-policy spaces.

Integration of data (mixed-methods triangulation)

This study brought together in triangulation these quantitative and qualitative strands to build validity and to gain a better understanding based on evidence from these. For instance: quantitative analysis indicated that association members were less food insecure. Qualitative interviews explained how and why: through bulk purchasing, savings groups, and emotional support. These qualitative results were compared with appropriate literature and explicated applying resilience theory that focuses on social networks and collective agency in helping migrants cope with adversity, and epistemic justice theory focusing on migrants' knowledges and daily practices of resistance that reverse exclusion and reclaim their right to belong. This synthesis allowed the study not just to recognize what is happening statistically, but to understand the lived experiences and underlying meanings behind the patterns.

CONCLUSION

This research has demonstrated that migrant-solidarity associations in South Africa are important for addressing social resilience provision, food insecurity, and social-spaces provision for migrant epistemic resistance and knowledge production. The solidarity associations are an attempt to be not only a survival strategy but also a type of collective agency that resists mainstream migration discourses and offers innovative solutions for migrants' socio-economic challenges.

The qualitative data gathered throughout Parow Valley, Summer Greens, and Kensington demonstrates that migrant networks are embedded in the everyday lives of migrants, creating long-term reactions to exclusion, precarity, and invisibility. Rather than depending on external assistance, these networks use internal resources, trust, information, and reciprocity to create new forms of governance, care, and economic survival.

The research has brought to the fore migrant epistemologies and everyday practices of solidarity, making visible grassroots movements' political stakes and providing migrant communities with an opportunity to bring about changes in social, political, and economic realms. The conclusions that this research indicates relate to the necessity to view migrants not so much as recipients of aid but rather as agents and the necessity for migration and food security policies to be more inclusive, decolonial, and epistemology-led by migrants. The theorization of solidarity, thus, not just as a political project but as social practice, is a gesture of critical juncture in the scholarship of migrant agency. Solidarity organizations are sites of invention and resistance, inventing new social belonging while resisting structural violence.

This paper is the result of a scholarship that has called for an epistemic turn in migration and development policy. It resists dominant hierarchies that downgrade migrants to objects to be controlled rather than co-performers of policy and practice-making. In a moment of climate crisis hegemony, heightened xenophobia, and food systems breakdown, exclusionary policy works to enhance inequality and forestall pragmatic solutions.

At the heart of this work is a recognition that migrant-led movements are not just survivalist. They are incubators of alternative futures, where imaginations of care, dignity, and reciprocity in direct opposition to existing regimes of extraction and domination are cultivated. Our empirical findings illustrate how migrant-solidarity networks embody resilience by building flexible networks that cushion the shocks of the system while practicing epistemic justice through the production of knowledge that challenges exclusion and marginalization (Holling, 2001; Fricker, 2007).

These mobilizations hold valuable lessons for the redesign of urban development, humanitarian intervention, and postcolonial governance toward justice, autonomy, and collective flourishing. Foregrounding agency and migrant knowledge, this paper illustrates how transformation can be seen at the borders on the grounds of agency, reframing dominant political and social narratives.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Policy integration

International institutions and governments need to include migrant-led solidarity action within regional and national migration policy, foregrounding food security. It reflects the migrant communities' ability for agency and innovation that implies more efficient policy interventions at the root causes of food insecurity and marginalization.

This entails charting existing solidarity networks, bringing migrant associations into policymaking, and institutionalizing cooperation with community-based organizations. Migration policy regimes must move beyond containment and surveillance to enable social protection systems to acknowledge and complement migrant-led initiatives. Integration needs to entail legal reforms reducing bureaucratic barriers to association, mobility, and access to food systems for undocumented migrants.

Grassroots network support

Grassroots solidarity networks must be supported, for instance, through resources, capacity building, and technical assistance. Grassroots solidarity networks are essential to the resilience of migrant communities and are able to contribute to disaster response, climate adaptation, and social cohesion.

Investment in local infrastructure, such as communal storage, gardens, and kitchens, can extend the reach of such networks. Donors and agencies must also shift from top-down models of development aid to long-term accompaniment models that build local agency. Organizing such aid to be gender sensitive as well as inclusive of marginalized migrant groups (e.g., migrants, refugees, youth) will enhance the transformative potential of such networks.

Epistemic justice in migration studies

Migration studies must practice epistemic justice in recognizing that migrants are knowledge producers just like researchers instead of being mere research subjects. Research methodologies must be more participative and co-produced so that migrant voices are heard and knowledge systems of migrants are given serious consideration. This entails developing research that works actively with migrants at every phase, from problem-definition and data-gathering to analysis and dissemination. Researchers are also required to interrogate critically their positionality and power within the research process and try to redistribute such power using collaborative designs. Academic departments and journals need to increase epistemic horizons by making space for the knowledges produced by migrant scholars, activists, and community practitioners.

Decolonizing migration discourse

Migration scholarship needs to move toward more decolonial trajectories that disengage from the dominant discourses of migration and recognize diversity of migrant experience. This requires reforming migration policy, border control regimes, and representation of migrants in policy and academic discourse. Decolonization, therefore, involves not only a recasting of the analytic imaginary but also an institutional change of heart. Decolonization involves the deconstruction of epistemic hierarchies that favor Global North knowledge and place migrant voices from the Global South at center stage as explanatory and leading migratory systems. Moreover, media, education, and development planning must avoid representing migrants only in terms of risk, crisis, or burden and promote instead their contributions, innovations, and rights.

Apart from these initial recommendations, this study suggests the following additional policy issues in the future:

• Intersectional policy solutions: The migration policies cannot be decoupled from other issues such as housing, health care, gender justice, and climate change. Policymakers need to adopt intersectional solutions that appreciate how different vulnerabilities intersect in shaping the migrant-community experience.

• Cross-border cooperation: In as much as most existing solidarity organizations are transnational, regional institutions like the African Union (AU) and the Southern African Development Community (SADC) should facilitate forums for cross-border cooperation, information sharing, and harmonized protection strategies for migrants. Cooperation can enhance best practices and develop advocacy for migrants' rights.

• Urban inclusion strategies: Migrants' perspectives need to be incorporated into urban planning, especially in the slums and food systems. Local food councils, participatory budgeting, and land-use policy design can operationalize migrant agency at the urban level.

• Monitoring and accountability: Establishing independent monitoring mechanisms for assessing migrant-inclusive policies is critical. These need to incorporate migrant voices in their design and oversight to bring responsiveness and accountability.

Overall, this work outlines the transformatory capacity of migrant-led solidarity associations as system-level change agents. They are less about coping mechanisms. Instead, they are more blueprints for a more equitable, participatory, and resilient world. In a world under threat from cross-cutting crises - economic, ecological, and political - there is much to learn from these: care, autonomy, and co-living by communities. Supporting and strengthening such migrant-led movements is not only a moral imperative but also a strategic imperative for building more equitable futures.

REFERENCES

Amelina, A. 2022. Knowledge production for whom? Doing migrations, colonialities and standpoints in non-hegemonic migration research. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 45(13): 2393-2415. [ Links ]

Awumbila, M., Garba, F., Darkwah, A.K. and Zaami, M. 2023. Migrant political mobilisation and solidarity building in the Global South. In Crawley, H. and Taye, J.K. (eds.), The Palgrave handbook of South-South migration and inequality. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 719-739. [ Links ]

Barglowski, K. and Bonfert, L. 2023. Migrant organisations, belonging and social protection: The role of migrant organisations in migrants' social risk-averting strategies. International Migration, 61(4): 72-87. [ Links ]

Beeby, L. 2012. The epistemology of resistance: Gender and racial oppression, epistemic injustice, and resistant imaginations. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Berkes, F. and Ross, H. 2013. Community resilience: Toward an integrated approach. Society and Natural Resources, 26(1): 5-20. [ Links ]

Blumenstock, J.E., Chi, G. and Tan, X. 2025. Migration and the value of social networks. Review of Economic Studies, 92(1): 97-128. [ Links ]

Byaruhanga, R. and Isgren, E. 2023. Rethinking the alternatives: Food sovereignty as a prerequisite for sustainable food security. Food Ethics, 8(2): 16. [ Links ]

Catala, A. 2015. Democracy, trust, and epistemic justice. The Monist, 98(4): 424-440. [ Links ]

Celikates, R. 2022. Remaking the demos "from below"? Critical theory, migrant struggles, and epistemic resistance. In Fassin, D. and Honneth, A. (eds.), Crisis under critique: How people assess, transform, and respond to critical situations. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 97-120. [ Links ]

Crush, J. 2001. The dark side of democracy: Migration, xenophobia, and human rights in South Africa. International Migration, 38(6): 103-133. [ Links ]

Dotson, K. 2011. Tracking epistemic violence, tracking practices of silencing. Hypatia, 26(2): 236-257. [ Links ]

Dunn, S. and Maharaj, P. 2023. Migrants in the informal sector: What we know so far. In Maharaj, P. (ed.), Migrant traders in South Africa. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 23-59. [ Links ]

Folke, C., Carpenter, S.R., Walker, B., Scheffer, M., Chapin, T. and Rockström, J. 2010. Resilience thinking integrating resilience, adaptability, and transformability. Ecology and Society, 15(4). [ Links ]

Frega, R. 2013. Review: José Medina, The epistemology of resistance, 2012, Oxford: Oxford University Press. European Journal of Pragmatism and American Philosophy, 5(1): 1-8.

Fricker, M. 2007. Hermeneutical injustice. In Fricker, M., Epistemic injustice: Power and the ethics of knowing. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 147-175. [ Links ]

Hlatshwayo, M. and Vally, S. 2014. Violence, resilience, and solidarity: The right to education for child migrants in South Africa. School Psychology International, 35(3): 266-279. [ Links ]

Hlatshwayo, N. and Wotela, K. 2018. Social capital as survival strategy for immigrants in South Africa: A conceptual framework. Immigration and Development, 7: 109-135. [ Links ]

Holling, C.S. 2001. Understanding the complexity of economic, ecological, and social systems. Ecosystems, 4: 390-405. [ Links ]

losifides, T. 2016. Qualitative methods in migration studies: A critical realist perspective. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Keles, J.Y., Markova, E. and Fatah, R. 2022. Migrants with insecure legal status and access to work: The role of ethnic solidarity networks. Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion: An International Journal, 41(7): 1047-1062. [ Links ]

Maldonado-Torres, N. 2016. Outline of ten theses on coloniality and decoloniality. Paris: Frantz Fanon Foundation. [ Links ]

Mazani, P. 2022. Migration and hospitality in Cape Town: A case of Zimbabwean migrants and refugees. Master's Thesis, University of the Western Cape. [ Links ]

Mazzola, A. and De Backer, M. 2021. Solidarity with vulnerable migrants during and beyond the state of crisis. Culture, Practice and Europeanization, 6(1): 55-69. [ Links ]

Medina, J. 2013. The epistemology of resistance: Gender and racial oppression, epistemic injustice, and the social imagination. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Mottiar, S. 2019. Everyday forms of resistance and claim making in Durban, South Africa. Journal of Political Power, 12(2): 276-292. https://doi.org/10.1080/2158379X.2019.1624059 [ Links ]

Moyo, K. 2024. Migration in Southern Africa: Openness is overshadowed by xenophobia. Global Food Journal: Development Policy and Agenda 2030.

Moyo, K. and Zanker, F. 2020. Political contestations within South African migration governance. Arnold Bergstraesser-Intitut. Deutsche Stiftung Friedensforschung.

Ncube, A. and Bahta, Y.T. 2022. Meeting adversity with resilience: Survival of Zimbabwean migrant women in South Africa. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 23(3): 1011-1043. [ Links ]

Olawuyi, S.O. 2019. Building resilience against food insecurity through social networks: The case of rural farmers in Oyo State, Nigeria. International Journal of Social Economics, 46(7): 874-886. [ Links ]

Owen, J., Juries, I. and Mokoena, M. 2024. Beyond migration categories: Amity, conviviality, and mutuality in South Africa. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 59(7): 2154-2169. [ Links ]

Pande, A. 2012. From "balcony talk" and "practical prayers" to illegal collectives: Migrant domestic workers and meso-level resistances in Lebanon. Gender and Society, 26(3): 382-405. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243212439247 [ Links ]

Pande, A. 2020. Body, space, and migrant ties: Migrant domestic workers and embodied resistances in Lebanon. In Baas, M. (ed.), The Asian migrant's body: Emotion, gender, and sexuality. Netherlands: Amsterdam University Press.

Piacentini, T. 2014. Everyday acts of resistance: The precarious lives of asylum seekers in Glasgow. In Marciniak, K. and Tyler, I. (eds.), Immigrant protest: Politics, aesthetics, and everyday dissent. New York: SUNY Press, pp. 169-187. [ Links ]

Ríos-Rojas, A. and Jaffe-Walter, R. 2022. "Before anything else, I am a person." Listening to the Epistemological standpoints of im/migrant youth: Racialisation and reimagining the human. Nordic Journal of Social Research, 13(1): 80-93. [ Links ]

Rugunanan, P. 2022. Migrating beyond borders and states: Instrumental and contingent solidarities among South Asian migrant informal workers in South Africa. In Rugunanan, P. and Xulu-Gama, N. (eds.), Migration in Southern Africa: IMISCOE regional reader. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 25-38. [ Links ]

Safouane, H., Jünemann, A. and Göttsche, S. 2020. Migrants' agency: A re-articulation beyond emancipation and resistance. New Political Science, 42(2): 197217. [ Links ]

Triandafyllidou, A. 2022. Spaces of solidarity and spaces of exception: Migration and membership during pandemic times. In Triandafyllidou, A. (ed.), Migration and pandemics: Spaces of solidarity and spaces of exception. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 3-21. [ Links ]

Ungar, M. 2011. The social ecology of resilience: Addressing contextual and cultural ambiguity of a nascent construct. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 81(1): 1-17. [ Links ]

Received 18 June 2025

Accepted 16 July 2025

Published 27 August 2025