Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

African Human Mobility Review

On-line version ISSN 2410-7972Print version ISSN 2411-6955

AHMR vol.10 n.3 Cape Town Sep./Dec. 2024

https://doi.org/10.14426/ahmr.v10i3.2439

ARTICLES

Migrant Remittances, Food Security, and Translocal Households in the Ghana-Qatar Migration Corridor

Bernard OwusuI; Jonathan CrushII

IWilfrid Laurier University, Waterloo, Canada. Corresponding author owus1530@mylaurier.ca

IIBalsillie School of International Affairs, Waterloo, Canada and University of the Western Cape, Cape Town South Africa. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3342-3192

ABSTRACT

This paper examines the impact of migrant remittances on household food security in the Ghana-Qatar migration corridor. Drawing on a 2023 survey of migrant-sending households in Ghana and in-depth qualitative interviews with migrants in Qatar, the study explores the characteristics, determinants, and patterns of remitting. The findings reveal that cash remittances play a crucial role in enhancing food security and the overall welfare of households in Ghana. However, the pressure to remit affects the food security of migrants in Qatar significantly, and they often adopt various coping strategies to manage their limited resources. The paper highlights the translocal nature of Ghanaian households, where remittances contribute to the cultural and economic sustenance of families. The study underscores the dual role of remittances in supporting household food security while imposing financial constraints on migrants and calls for policies that address the needs of both remitters and recipients.

Keywords: migrant workers, remittances, food security, transiocality, Qatar, Ghana

INTRODUCTION

The growing volume of international global remittances has led to a significant body of research examining their impact in the Global South (Adams, 2011; Connell and Brown, 2015; Azizi, 2021; Benhamou and Cassin, 2021; Feld, 2021). The literature generally emphasizes the positive impact of remittances on economic growth, education, housing, and healthcare. Remittances are also widely credited with improved livelihood opportunities and poverty reduction (Fonta et al., 2022). However, only recently has attention turned to the impact of international remittances on food security in low- and middle-income countries (Ebadi et al., 2018; Sulemana et al., 2018; Smith and Floro, 2021; Seydou, 2023).

The emerging case study suggests that there are several ways in which remittances potentially enhance the food and nutritional security of recipient households. As a major source of income for recipient households, remittances can increase their ability to pay for basic needs such as education, medical care, and food. Recent studies in Asia (Moniruzzaman, 2022), Central America (Mora-Rivera and Van Gameren, 2021), and Africa (Abadi et al., 2018) show that food purchase is an important use of remittances, and recipient households are relatively more food secure than non-recipient households. In Ghana, work on international and internal remittance impacts has consistently reported positive effects on household income, welfare, and food security (Quartey, 2006; Sam et al., 2013; Atuoye et al., 2017; Akpa, 2018; Sulemana et al., 2018; Adjei-Mantey et al., 2023). However, as Thow et al. (2016) observe, remittances can also be spent on unhealthy foods and contribute to the epidemic of overnutrition.

Remittances are a potential source of funds for investment in boosting agricultural production and productivity, enhancing the ability of rural households to grow more of their own food, and mitigating food insecurity (Regmi and Paudel, 2017; Xing, 2018; Dedewanou and Tossou, 2021; Szabo et al., 2022; Cau and Agadjanian, 2023). The International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD, 2023) estimates that recipients either save or invest 25% of the money they receive, and that one-quarter of these savings (US$ 25 billion annually) go into agriculture-related investments. In the case of Ghana, Adams and Cuecuecha (2013) show that the bulk of remittances are spent on food, housing, and education. However, there is some case study evidence of agriculture-related investments. For example, Eghan and Adjasi (2023) show that the varied effects of remittances on agriculture depend on crop type and other economic activities of farming households.

Remittances also play an important food security-related role in mitigating sudden-onset and longer-duration economic, political, and environmental shocks (Couharde and Generoso, 2015; Bragg et al., 2017; Ajide and Alimi, 2019). Migrant remittances also tend to increase in volume in response to sudden shocks and in conflict settings (Le De et al., 2013; Bettin and Zazzaro, 2018; Rodima-Taylor, 2022). During the COVID-19 pandemic, remittances were initially expected to decline precipitously, but many migrants "defied the odds" and increased their remitting (Kpodar et al., 2023). The shock-absorbing mechanism (Ajide and Alimi, 2019) of increased remittances can play an important role in building resilience to food insecurity during recurrent or episodic crises and shocks (Obi et al., 2020; Gianelli and Canessa, 2021; Zingwe et al., 2023).

While there is a growing body of research on the impact of remittances on household food security, only a few have examined the impact of remitting on the food and nutritional security of remitters at their place of destination (Headley et al., 2008; Zezza et al., 2011; Choitani, 2017; Crush and Tawodzera, 2017; Osei-Kwasi et al., 2019). This paper expands on the existing literature that explores the complex relationship between migration and food security in Africa by presenting findings on the remitting practices of Ghanaian migrants working in the Gulf country of Qatar. It explores the links between migration, remittances, and food security by addressing the following questions: (a) What are the characteristics and motivations for remitting by Ghanaian migrants in Qatar? (b) How do recipient households use remittances, and do they improve the food security of those households? (c) Does the pressure or obligation to remit have negative food security consequences for migrants in Qatar? To answer these questions, the paper draws on data from two main sources: a 2023 survey of migrant-sending households in Ghana by the authors and in-depth interviews with Ghanaian migrants in Qatar. In the next section, we provide an overview of the emergence of Qatar as a destination for Ghanaian migrants, review the existing literature on this phenomenon, and discuss the conceptual framework for this study. The paper then presents the survey results on the receipt and use of remittances by migrant-sending households in Ghana, as well as their food security status. The final section discusses various themes relating to remitting and food security that emerged from the interviews in Qatar.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Ghana's long history of post-independence international migration has unfolded over several overlapping phases. Immediately after independence - in particular during the 1960s and 1970s - a small number of professionals, primarily students, went abroad for educational purposes; they were joined by others who trained as civil servants (Peil, 1995; Anarfi et al., 2003). The late 1970s and early 1980s saw the migration of trained professionals, such as teachers, to other countries in Africa where their expertise and skills were highly valued. Within the West African sub-region, Nigeria became a popular destination for Ghanaians, especially during the oil boom. However, in 1983, Nigerian President Shagari signed an executive order deporting all West African migrants from the country. Over two million migrants were deported, including one million Ghanaians (Daly, 2023).

In the late 1980s and the 1990s, skilled and semi-skilled Ghanaians began to emigrate in larger numbers to destinations outside the continent, including North America and Western Europe (Asiedu, 2010; González-Ferrer et al., 2013; Arthur, 2016; Schans et al., 2018). Most migrated in response to the economic crises and dislocation in Ghana that accompanied structural adjustment programs. These were implemented by the military government seeking to reverse economic decline and a massive balance of payments deficit (Konadu-Agyeman, 2000). The 1990s also saw the outmigration of migrants to new destinations such as Australia, North Africa, Eastern Europe, and Asia (Obeng, 2019; Andall, 2021; Kandilige et al., 2024). Across all of these phases, the decline in economic opportunities, depressed living standards, and the quest for improved livelihoods triggered the emigration of migrants.

In the last two decades, the Gulf emerged as an important destination for lower-skilled male and female Ghanaians who took advantage of the voracious demand of the Gulf states for the importation of temporary migrant workers. On the supply side, the movement was driven by the high rate of unemployment, low remuneration, and heightened poverty that many Ghanaian households faced within the country (Atong et al., 2018). The movement of migrants to the Gulf was facilitated by a proliferation of brokers, recruiters, and work placement agencies who hire low-skilled and unskilled migrants as domestic workers, security guards, construction workers, and drivers for employers (Awumbila et al., 2019a; Deshingkar et al., 2019).

While data on migrant Ghanaians in the Gulf is scant, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Qatar have become popular destinations for semi-skilled and unskilled male and female Ghanaian migrant workers (Atong et al., 2018; Awumbila et al., 2019; Rahman and Salisu, 2023). Recent studies show that about 75,000 Ghanaians are working in the Gulf, with an estimated 27,000 in Saudi Arabia, 24,000 in the UAE, 8,000 in Qatar, 4,500 in Bahrain, and 3,500 in Oman (Rahman and Salisu, 2023). However, these may be underestimates, given that not all migrants move through registered channels.

Several studies have revealed the poor working conditions and exploitative nature of the employment of temporary Ghanaian migrant workers in Qatar and elsewhere in the Gulf (Atong et al., 2018; Awumbila et al., 2019a; Kandilige et al., 2023). Others have documented the misrepresentation, abuse, harassment, and other difficulties that migrants face during their journey to and from workplaces in countries like Qatar (Apekey et al., 2018; Awumbila et al., 2019; Deshingkar et al., 2019). Additional studies have focused on the migration industry, the role of brokers and recruiters, and the reintegration experiences of returning migrants (Awumbila et al., 2019b; Rahman and Salisu, 2023). However, insufficient research attention has been paid to remitting practices in the Qatar-Ghana migration corridor and the impacts of remittances on the food security of translocal households in Ghana and Qatar.

Interactions between migrants and households in their countries or regions of origin have been variously conceptualized as "multi-spatial" (Foeken and Owuor, 2001), "stretched" (Porter et al., 2018), "multi-locational" (Schmidt-Kallert and Franke, 2012; Andersson Djurfeldt, 2015; Ramisch, 2016), and "translocal" (Greiner, 2011). Following Porter et al. (2018), Steinbrink and Niedenführ (2020), and Andersson-Djurfeldt (2021), we suggest that the concept of translocality is a useful starting point for framing the material and other connections between Ghanaian migrants in Qatar and households in Ghana. Steinbrink and Niedenführ (2020) see translocal households as collective social and economic units whose members do not live in one place but effectively coordinate their reproduction, consumption, and resource usage activities. Greiner (2011: 610) describes translocalism as "the emergence of multidirectional and overlapping networks created by migration that facilitate the circulation of resources, practices and ideas and thereby transforming the particular localities they connect." Migration of household members results in household networks, multiple sources of family income, and increased exchange of goods, information, and ideas between the origin and destination localities (Andersson Djurfeldt, 2015). Connectivity within translocal households is a fundamental survival strategy that contributes to sustainable livelihoods and food security for families at home. There is a mutual benefit through remittances and food transfers in a bi-directional relationship. While this concept of translocality in Africa has largely been applied to internal migration and livelihood strategies, international migration has similar dynamics when it comes to the food security of translocal households tied together by remittances (Crush and Caesar, 2018).

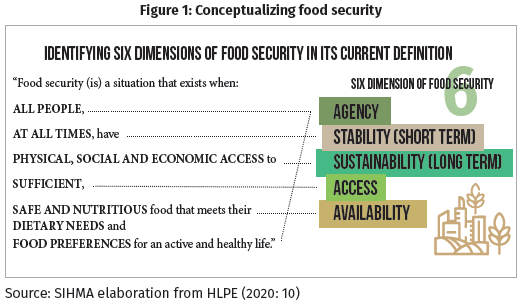

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO, 2006) defines food security as when "all people, at all times, have physical, social, and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life." Food security has six basic pillars: availability, accessibility, utilization, stability, agency, and sustainability (see Figure 1) (HLPE, 2020). This study focuses primarily on the accessibility and utilization dimensions of food security in Ghana and Qatar. The in-depth interviews in Qatar also provide insights into the agency exercised by migrants in making choices about remittances and food consumption, and the constraints on that agency.

METHODOLOGY

The research team collected data for this study in Ghana and Qatar from March to June 2023 using a mixed methodology. In the first phase of the research, we administered a household survey to a sample of households with migrants currently living and working in Qatar. There is limited information about the location of these households and no sampling frame from which to derive a probabilistic sample. Migrants in Qatar come from all over Ghana, but for logistical and cost reasons, sampling was concentrated in Accra and Kasoa, where, anecdotally, there were believed to be sizable numbers of migrant-sending households. The research team recruited participants through migrant networks, contacts at recruitment agencies, and the Ghana Immigration Service. In the time available, this non-probabilistic sampling method yielded 200 completed interviews. The survey collected data on the socio-economic characteristics of the household, factors influencing the decision to send migrants to Qatar, incomes and expenditure, remittance receipt and use, and household food security. The team collected the survey data on tablets using ODK Collect - an Android app for managing and filling out forms - and stored it in the Kobo Toolbox online. These data were downloaded for analysis after the surveys were concluded.

The study used the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) to assess the access dimension of food security in relation to the quality and quantity of food in the household and the dimension of worry and anxiety about food access and supply (Coates et al., 2007). The researchers generated a score for each household on a scale from 0 (most secure) to 27 (most insecure). Based on the HFIAS scores, they used the Household Food Insecurity Access Prevalence (HFIAP) to assign each household to one of four categories: food secure, mildly food insecure, moderately food insecure, and severely food insecure.

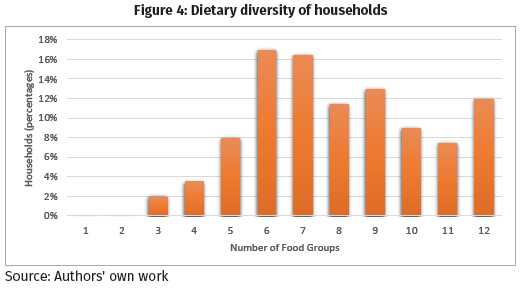

To capture food utilization, the researchers used the Household Dietary Diversity Scale (HDDS), which measures how many food groups were consumed in the household in the previous 24 hours and generates a score between 0 and 12 for each. Households were then categorized as having high (from 6 to12), medium (from 4 to 5) or low (from 0 to 3) dietary diversity (Baliwati et al., 2015). In addition to calculating the different food security metrics for households in Ghana, the research team compiled aggregated statistical tables with a focus on household characteristics, income sources, and use of remittances. Given the non-probabilistic sample, we focused on building a descriptive statistical profile of the sample of 200 migrant-sending and remittance-receiving households.

In the second phase of the research, the team conducted in-depth face-to-face interviews with Ghanaian migrants working in Doha and surrounding communities in Qatar. We identified 58 participants, using the purposive snowball sampling method with the assistance of a local gatekeeper. The initial participants were recruited through community networks such as the Ghanaian Association in Qatar and churches. The team arranged interviews at workforce camps, other accommodation facilities, and Ghanaian restaurants. These semi-structured interviews focused on a range of issues, including migration histories, employment and the nature of work, remittance motivations and practices, as well as food availability, access, and utilization experiences. For the analysis of the interviews, the researchers used thematic analysis to identify common patterns and describe and interpret the study data collected (Braun and Clarke, 2006). To identify common themes, we analyzed and coded transcripts of interviews, using Nvivo 12 software.

The study limitations include, first, that the findings in Ghana and Qatar are not directly comparable given the different methodologies used in each site. As a result, the Ghana survey provides more accurate statistical indicators of remittance usage and food security status, while the Qatar survey provides rich personal insights into the subjective food security experiences and remitting of migrants. Second, the migrants interviewed in Qatar were not necessarily from the same households as those surveyed in Ghana. Tracing those migrants would have been a breach of confidentiality and anonymity and would have been extremely challenging in the short time available for research in Qatar. Hence, only broad conclusions, rather than direct causal connections, can be drawn about translocality. Third, these were hard-to-reach populations in both sites, and random sampling was impossible. Both phases relied on non-probabilistic snowball sampling to identify respondents. As a result, the findings are indicative rather than representative and generalizable.

SURVEY RESULTS

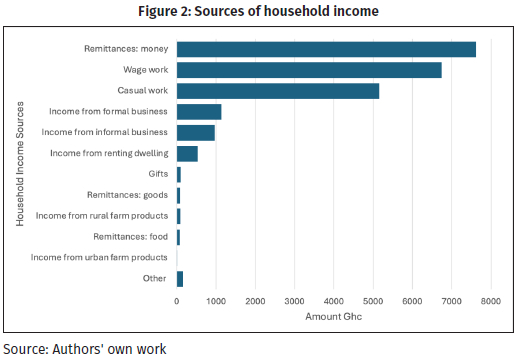

As many as 80% of the respondent households in Ghana had received cash remittances from their migrant members in Qatar in the previous year. Remittances were the most important source of household income overall, exceeding wage and casual work, as well as income from running a business (see Figure 2). The amounts sent to the household in Ghana varied considerably, with 34% receiving an average of Ghc 1,500 (USD 91) per month and 44% receiving more than Ghc 2,500 (USD 153) per month. However, only 11% of the households received remittances more than once a month and another one-third monthly. The rest received remittances only a few times in the year.

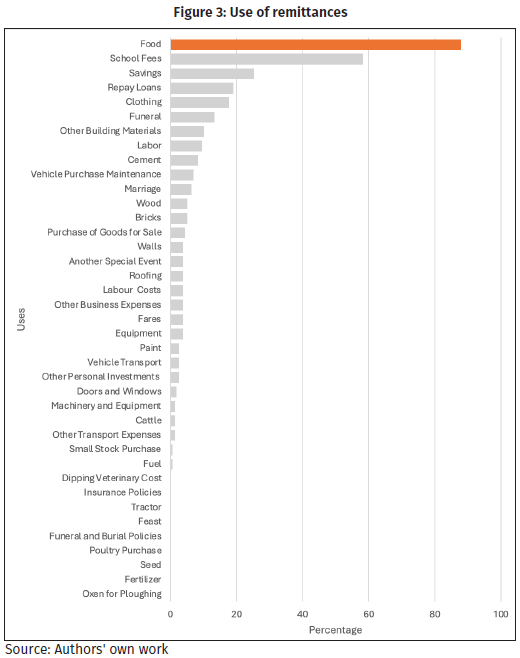

Remittances had a marked impact on these migrant-sending households in Ghana. As many as 73% of the respondents indicated that remittances were "very important" to their household, and another 18% said that they were "important." These findings are consistent with studies that have examined the role of remittances in improving household food security in the Northern and Upper-East regions of Ghana (Karamba et al., 2011; Kuuire et al., 2013; Sulemana et al., 2018; Akobeng, 2022; Apatinga et al., 2022; Baako-Amponsah et al., 2024). Remittances are used for a wide variety of household expenses, mostly basic needs. The most common use was food purchase (see Figure 3), with almost 90% of remittance-receiving households using the funds to buy food. Other important uses included investment in children's education (at 58%), and financial transactions in the form of savings (25%) and repaying loans (19%). Yet other uses included buying clothing (18%), funeral expenses (13%), and paying for a variety of construction materials such as cement, wood, bricks, and paint. None of the respondents invested remittances in improving rural agriculture, although a handful did purchase cattle with remittances. The findings about the priority given to remittance expenditure on food purchases are consistent with those of studies in other parts of Africa (see, for example, Pendleton et al., 2014; Crush and Caesar, 2017, 2018).

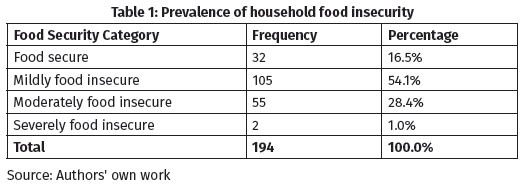

On the HFIAP indicator, only 1% of the households were classified as severely food insecure. On the other hand, just 17% of the households were completely food secure (see Table 1). Over half (54%) were only mildly food insecure. These results suggest that food insecurity is still a challenge among this group of remittance-receiving Ghanaian households but would be much more severe without the transfer of remittances from Qatar. The HDDS analysis shows that household dietary diversity was relatively high, with a mean of 8 out of a possible 12, indicating that, on average, the household consumed food from approximately eight different groups in the previous 24 hours. Approximately 47% had a dietary diversity score of 7 or less, and 53% had an HDDS above 7 (see Figure 4).

INTERVIEW RESULTS

This section focuses on the results of the Nvivo thematic analysis of in-depth interviews, concentrating on four key themes: translocality, remitting capacity, rationale for remitting, and remittances and food security. On the first theme, many of the Ghanaian migrants interviewed were clearly embedded in translocal households with nodes in Ghana and Qatar. For example, one migrant described the principle of reciprocity within their translocal household in this way:

I believe it's necessary to share my success with my family, no matter how small it may be. Back in Ghana, when I needed help, they supported me, so it's only fair to reciprocate and support them now. I don't get worried when I send them money because I always budget for things I need here and the rest for my family back home, which they can share among themselves. (Interview No. 29, Qatar, 4 June 2023).

Another mentioned his obligation for the family's survival in Ghana, seeing himself as the family 'breadwinner' and provider:

I send money every month to my wife and child. Monthly, I send 800 Ghs and support my siblings when they are needed. I am the man, the breadwinner, and the father. They cannot survive without me. Besides, it is my responsibility to provide for them as the man and father of the house. The money is used for household food purchases. (Interview No. 8, Qatar, 31 May 2023).

A third described how he coordinates his remitting to Ghana with family members in Italy, suggesting that some migrants in Qatar are members of more complex multilocal households with nodes in Ghana, Qatar, and elsewhere:

My other siblings in Italy help the family when one of us is lacking, especially during festive seasons; since we are Muslims, we send them money. My siblings also support the family when one of us is facing difficulties. Currently, I don't have any job, so any money I sent home will push me into a food crisis. I didn't have this problem previously when I was working. (Interview No. 28, Qatar, 4 June 2023).

On the second thematic issue of remitting capacity, the interviews provided insights into the remitting priorities of migrants in Qatar. A number addressed the question of why they were not always able to send large amounts home or were unable to remit on a consistent and regular basis. The frequency of remitting was clearly affected by their precarious economic status in Qatar, including the availability of jobs and the constant reality of job loss:

I try to remit [to] the family regularly, even though there are times when I cannot do so due to financial constraints, just like last month's ending. I pleaded with them that they will hear from me when things go well. (Interview No. 29, Qatar, 4 June 2023).

In the lead-up to the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar, there were numerous job opportunities in the construction industry. Many migrant workers left the companies who had recruited them in Ghana to become what they call "freelancers" who work in construction or other higher-earning sectors. However, after the World Cup, employment layoffs left many Ghanaian "freelancers" stranded and unemployed, with their savings spent on food and accommodation. They had very little money with which to support the household in Ghana. For example:

It has been seven months since I sent money to my family, but I explained to them that things have been difficult, and they understood my situation. The first 14 months in this country was peaceful and different. There was a lot of construction jobs available due to the 2022 World Cup. I survived, I had something to depend on and could consistently send [money] every month to the family, but this whole mess started when I moved from the company to freelance before the World Cup. Life has been complicated after the World Cup. A lot of jobs have shut down. (Interview No. 17, Qatar, 4 June 2023).

My earnings in Qatar have been minimal after the World Cup. I haven't been able to send enough money home to benefit the family for some time now. I could not even repay all the loans I took to come to Qatar. The land I used as collateral was seized and sold. I feel so disappointed in myself. I focused on getting my ID, so I didn't spend much on food. I hope they will pay me for the two weeks of work arrears, which should be 1,400 Riyals or half of it so that I can use that to survive. (Interview No. 34, Qatar, 9 June 2023).

I am unemployed; I don't send money home and manage what I have for my stay. But previously, I used to remit every month whenever I was paid my basic salary. Why should I send money to someone when I am unemployed and unsettled? They know how generous I am, but they would have to pardon me for now. (Interview No. 27, Qatar, 4 June 2023).

The interviews with the migrants in Qatar also provided insights into the reasons for sending remittances back to Ghana. Remitting to pay school fees and educational support was a major theme in many interviews and is consistent with Gyimah-Brempong and Asiedu's (2015) study on remittances and education in Ghana, which found a strong link between remittances and the formation of human capital. They note that international remittances significantly increase the probability that families will invest in the primary and high school education of children in Ghana. As one migrant confirmed:

I send money every month to my family, about 1,500 Cedis, to support their education. If it means sending the last amount of money on me, I will do whatever it takes to give them a better education and dreams. My kids and wife are why I am working, and I must take good care of them. I even have this education I am talking about well-planned out as well. I have learned that Ghana's educational system doesn't meet the desired standards, especially at the university level. I plan to enroll my children in vocational training after they complete junior high school, like being a mechanic, mason, fixing air conditioners, etc., which would make them better than their mates. (Interview No. 30, Qatar, 8 June 2023).

Another respondent noted that the school fees of his younger sibling are non-negotiable, regardless of his situation:

I send money to my mom for upkeep and to care for my little brother, who is still in senior high school. I am not financially stable; I sometimes struggle to eat, especially when sending money. I still have to think about my family's well-being, especially that of my little brother, who is still in school. It would go a long way to prevent him from indulging in certain practices to get money when he is not getting enough at home. (Interview No. 26, Qatar, June 6, 2023).

Additionally, most migrants in Qatar confirmed that food security features largely in their reasons for remitting to translocal household members in Ghana. For example:

I send money to the family in Ghana every month. I send 900 Cedis purposely for their food. They use the money to buy foodstuffs, including rice, beans, yam, chicken, etc. Rice is the most essential food in my household because of my kids. They like rice a lot. I want to give them a good life; it is my responsibility, and I fully embrace it. (Interview No. 5, Qatar, 31 May 2023).

I ask my mother what they need at home at the end of every month. I tell my aunt, who owns a "provision shop" (mini grocery shop), to make the list of items such as Milo, soups, cereals, soaps, rice, oil, Cowbell coffee, and tomato pastes and package them and give them to my mother. So, she might package groceries of about Ghc 300; then I will send her 800 Ghc, and she takes her money and gives the rest to my parents. I give them about 500 Ghc to my mother for their monthly upkeep and my son's feeding fee. My child's feeding fee is about 15 Ghc a day plus her lunch of about 5 Ghc. (Interview No. 1, Qatar, 31 May 2023).

In some cases, remittances for food purchase supplement household income from other sources:

My mother is not working, but my dad is a commercial driver, so sometimes he supports the family every month, too. He adds to the money and uses it to buy foodstuffs such as plantain, cassava, rice, vegetables, including garden eggs and other items on his way home after work. (Interview No. 3, Qatar, 31 May 2023).

A single mother noted that the food security of her family in Ghana had improved since she migrated to Qatar:

Life has been difficult, but things have improved since I came to Qatar. I am able to send some little money to my family, which has, to some extent, paid their rent and supported household food purchases and consumptions and the family in general, though the salary is not much all the money goes to essential household expenditures, such as sending money to feed my kids and paying the rent for them whenever it is due. (Interview No. 1, Qatar, 31 May 2023).

Another respondent noted a similar improvement in his ability to provide food for the family in Ghana since migrating to Qatar:

At least, I have been earning some money to support and provide food for my wife and kids and even started a project, something I wasn't able to do while in Ghana. (Interview No. 5, Qatar, 31 May 2023).

The capacity of migrants to remit on a regular basis is clearly key to sustainable household food security over time. If there are any delays or irregularities, the household must adjust its food consumption accordingly:

I am able to send money back home to Ghana once a month, but it sometimes delays when I am not paid. In that case, they have to adjust and find alternate ways to feed [people] at home until I am able to remit to them when I am paid. (Interview No. 54, Qatar, 17 June 2023).

An additional use of remittances with longer-term food security implications is the investment of remittance income in small income-generating businesses in Ghana. Respondents stressed that these small businesses generate income for the household to manage the food situation at times when they have not been able to remit:

I regularly send money to my mom and girlfriend in Ghana at the end of every month for her food. Also, I helped my mom reopen her collapsed bar to provide her with a source of income and food. You know, the job here is erratic, especially when you are on a free visa. Besides, you can be sacked at any time. I carefully manage how I send money to ensure that I save and support my family without leaving myself stranded here. (Interview No. 49, Qatar, 15 June 2023).

Some respondents noted that helping the household set up a small business relieved them of the pressure of caring for their children and extended family members. As one noted:

I don't send money to my family often. This is because my sister has her own business, which I helped to set up. She benefits and gets her income for food from the returns, so I don't have to work to support household food consumption - helping her monthly as well as my son would put a huge burden on me. Instead, I send my son 300 Riyals (Ghc 900) monthly. Sometimes, when I don't remit, my sister supports my son too, because she has the business. She takes money from me for food purchases and other household needs until I can remit to them. (Interview No. 22, Qatar, 4 June 2023).

Finally, there is the question of whether remitting to Ghana impinges in any way on the food security of remitters in Qatar. Other studies have suggested that remitting can affect their own food security negatively, forcing them to adopt various coping strategies (Crush and Tawodzera, 2017). Some respondents said they were able to remit by adjusting their own consumption, eating simply and cheaply in cafeterias and Ghanaian restaurants. For example:

Sending them money doesn't affect me here because I plan to keep some 100 Riyals on me for a month, which I use for basic expenses here. Still, even with that, I don't use all the 100 Riyals. I sometimes spend only 50 Riyals in a month. After all, I don't spend much here because I don't buy any clothing, and with food, I rarely make orders. I just go to the restaurant and eat at the work cafeteria, even though I don't like it at times (Interview No. 48, Qatar, 14 June 2023).

More common were descriptions by migrants of depriving themselves of food to save money to remit:

When I send the money home to my son and siblings, it also impacts me here, but I can't complain; if I don't do it, who will? I have to manage. It's not like they are using the money to do anything for me, but for their consumption. If I want to eat what I want, I might need 500 Riyals every month; but with my responsibilities, it is impossible. I must eat smaller and the same meals all the time. (Interview No. 4, Qatar, 31 May 2023).

My family is always appreciative of the little financial support. I send them regularly every month when I am paid, which makes me happy. Sometimes, sending money home puts me in a difficult situation here, especially when we are not paid early. I sometimes take foodstuffs such as rice from my friends and pay for or replace it when I am paid. (Interview No. 51, Qatar, 15 June 2023).

A single mother with three younger siblings explained that she had an enormous responsibility to her family in Ghana, so she kept only 10% of her basic monthly salary for her own monotonous diet:

Remitting money to my family in Ghana sometimes impacts what I eat. I don't send all the money: sometimes, I leave about 150 qa (from my basic salary of 1,500) on me for upkeep and food, which is not enough, but I "manage" it all the time. I am eating the same kind of food all the time. For instance, I eat one way: rice with no variety all the time because I want to manage the money. (Interview No. 1, Qatar, 31 May 2023).

A male respondent in his late twenties said that he ate beans all the time to cope with the financial pressure and burden that comes with assisting members of the translocal family:

Sending money impacted what I ate. Honestly, it was beans and gari that I usually like to eat because, per my calculation, it would have been difficult and lost for me to eat other foods. Someone owed me, so I relied on that to purchase food. (Interview No. 16, Qatar, 4 June 2023).

To cut down on living costs in Qatar and free up funds in order to remit, many migrants share the same rented housing space and kitchen with a degree of community living and solidarity. Shared cooking also cuts down the cost of food. Although some Ghanaian migrants work for companies where food is provided, they prefer to join their colleagues to cook and eat as a group:

In difficult times here in Qatar, my brothers in this room often help me. Even when we were all in the company and were provided food, we didn't like it because it was difficult to eat and hence, though not allowed in the company building, we still prepared food as a group and eat. Every member in the room contributed money that we used to buy foodstuff to prepare the meals. (Interview No. 28, Qatar, 7 June 2023).

CONCLUSION

Most studies of the relationship between migration and remittances focus on migrants who remit or households that receive. This study breaks with tradition by focusing on both ends of the Ghana-Qatar remittance corridor. In this paper, we juxtapose the results of a sample survey of remittance recipient households in Ghana with the observations of Ghanaian migrants working in Qatar about their remitting motivations, practices, and challenges. The combination of quantitative and qualitative data in the two sites provides new insights into the importance of remittance receipts for migrant-sending households in Ghana and complementarity insights into the remitting patterns of Ghanaian migrants in Qatar.

Peth (2018, blog) argues that "translocality is a variety of enduring, open, and non-linear processes, which produce close interrelations between different places and people. These interrelations and various forms of exchange are created through migration flows and networks that are constantly questioned and reworked." The priorities of remittance senders and the perspectives of remittance recipients indicate that this definition of translocality provides an appropriate conceptual framing for understanding the intimate material and emotive connections between migrants in Qatar and households in Ghana enabled by migrant remittances. At this stage, given the non-probabilistic nature of the sample in the two locations and the fact that the migrants interviewed are not necessarily from the same households as those surveyed, direct translocal linkages are indicative rather than definitive for future research on this migration and remittance corridor.

In the introduction, we posed several questions about this relationship: first, how do recipient households use remittances, and do they improve the food security of those households? Second, does the pressure or obligation to remit have negative food security consequences for migrants? Based on the data collected, these questions can be answered in the affirmative. Food purchase is a major use of remittances by the surveyed households in Ghana, and this infusion of income from outside the country significantly enhances levels of food security and dietary diversity. However, migrant cash remittances not only alleviate household food insecurity but improve household welfare through food purchases, payment of children's school fees, and enabling startup business opportunities. In Qatar, if migrants are employed and earning income, they can balance the obligation to remit with their own food consumption needs. However, unemployment and income loss affect their ability to remit and their own food security situation negatively. As one translocal migrant observed: "I could have enjoyed much better food and lived comfortably, if it was all about me." (Interview No. 1, Qatar, 31 May 2023).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) Grant No. 895-2021-1004 to the Migration and Food Security in the Global South (MiFOOD) Network.

REFERENCES

Abadi, N., Techane, A., Tesfay, G., Maxwell, D., and Vaitla, B. 2018. The impact of remittances on household food security: A micro perspective from Tigray, Ethiopia. WIDER Working Paper No. 2018/40, United Nations University.

Adams, J. 2011. Evaluating the economic impact of international remittances on developing countries using household surveys: A literature review. Journal of Development Studies, 47(6): 809-828. [ Links ]

Adjei-Mantey, K., Awuku, M. and Kodom, R. 2023. Revisiting the determinants of food security: Does regular remittance inflow play a role in Ghanaian house-holds? A disaggregated analysis. Regional Science Policy & Practice, 15(6): 1132-1147. [ Links ]

Ajide, K. and Alimi, O. 2019. Political instability and migrants' remittances into sub-Saharan Africa region. GeoJournal, 84: 1657-1675. [ Links ]

Akobeng, E. 2022. Migrant remittances and consumption expenditure under rain-fed agricultural income: Micro-level evidence from Ghana. Oxford Development Studies, 50(4): 352-371. [ Links ]

Akpa, E. 2018. Private remittances received and household consumption in Ghana (1980-2016): An ARDL analysis with structural breaks. MPRA Paper 87103, University Library of Munich, Germany.

Anarfi, J., Kwankye, S., Ababio, O. and Tiemoko, R. 2003. Migration from and to Ghana: A background paper. DRC on Migration, Globalization and Poverty, University of Sussex.

Andall, J. 2021. African labour migration and the small firm sector in Japan. Journal of Human Security Studies, 10(2): 97-108. [ Links ]

Andersson Djurfeldt, A. 2015. Multi-local livelihoods and food security in rural Africa. Journal of International Development, 27(4): 528-545. [ Links ]

Andersson Djurfeldt, A. 2021. Translocal livelihoods research and the household in the Global South: A gendered perspective. Journal of Rural Studies, 86, 16-23. [ Links ]

Apatinga, G., Asiedu, A. and Obeng, F. 2022. The contribution of non-cash remittances to the welfare of households in the Kassena-Nankana District, Ghana. African Geographical Review, 41(2): 214-225. [ Links ]

Apekey, D., Agyeman, P. and Ablordepey, A. 2018. Women's migration on the Africa-Middle East Corridor: Experiences of migrant domestic workers from Ghana. Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women.

Arthur, J. 2016. The African diaspora in the United States and Europe: The Ghanaian experience. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Asiedu, A. 2010. Some perspectives on the migration of skilled professionals from Ghana. African Studies Review, 53(1): 61-78. [ Links ]

Atong, K., Mayah, E. and Odigie, A. 2018. African labour migration to the GCC States: The case of Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria and Uganda. ITUC-Africa.

Atuoye, K., Kuuire, V., Kangmennaang, J., Antabe, R. and Luginaah, I. 2017. Residential remittances and food security in the Upper West Region of Ghana. International Migration 55(4): 18-34. [ Links ]

Awumbila, M., Teye, J., Kandilige, L., Nikoi., E. and Deshingkar., P. 2019a. Connection men, pusher, and migrant trajectories: Examining the dynamics of migration industry in Ghana and along routes into Europe and the Gulf States. Working Paper, Migrating Out of Poverty Consortium, University of Sussex.

Awumbila, M., Deshingkar, P., Kandilige, L., Teye, J. and Setrana, M. 2019b. Please, thank you and sorry: Brokering migration and constructing identities for domestic work in Ghana. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 45(14): 2655-2671. [ Links ]

Azizi, S. 2021. The impacts of workers' remittances on poverty and inequality in developing countries. Empirical Economics, 60(2): 969-991. [ Links ]

Baako-Amponsah, J., Annim, S. and Kwasi Obeng, C. 2024. Relative effect of food and cash remittance on household food security. International Trade Journal, 38(4): 348-369. [ Links ]

Baliwati, Y., Briawan, D. and Melani, V. 2015. Validation household dietary diversity score (HDDS) to identify food insecure households in industrial area. Pakistan Journal of Nutrition 14(4): 234-238 [ Links ]

Benhamou, Z. and Cassin, L. 2021. The impact of remittances on savings, capital and economic growth in small emerging countries. Economic Modelling, 94: 789-803. [ Links ]

Bettin, G. and Zazzaro, A. 2018. The impact of natural disasters on remittances to low- and middle-income countries. Journal of Development Studies, 54(3): 481-500. [ Links ]

Bragg, C., Gibson, G., King, H., Lefler, A. and Ntoubandi, F. 2017. Remittances as aid following major sudden-onset natural disasters. Disasters, 42(1): 3-18. [ Links ]

Braun, V. and Clarke, V. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2): 77-101. [ Links ]

Cau, B. and Agadjanian, V. 2023. Labour migration and food security in rural Mozambique: Do agricultural investment, asset building and local employment matter? Journal of International Development, 35(8): 2332-2350. [ Links ]

Choitani, C. 2017. Understanding the linkages between migration and household food security in India. Geographical Research, 55: 192-205. [ Links ]

Coates, J., Swindale, A. and Bilinsky, P. 2007. Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for measurement of food access: Indicator guide (Version 3). Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project, Academy for Educational Development, Washington, D.C.

Connell, J. and Brown, R. (eds.). 2015. Migration and remittances. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. [ Links ]

Couharde, C. and Generoso, R. 2015. The ambiguous role of remittances in West African countries facing climate variability. Environment and Development Economics, 20(4): 493-515. [ Links ]

Crush, J. 2013. Linking migration, development and urban food security. International Migration, 51: 61-75. [ Links ]

Crush, J. and Caesar, M. 2017. Cultivating the migration-food security nexus. International Migration, 55(4): 10-17. [ Links ]

Crush, J. and Caesar, M. 2018. Food remittances and food security: A review. Migration and Development, 7: 180-200. [ Links ]

Crush, J. and Tawodzera, G. 2017. South-South migration and urban food security: Zimbabwean migrants in South African cities. International Migration, 55: 88-102. [ Links ]

Daly, S. 2023. Ghana must go: Nativism and the politics of expulsion in West Africa, 1969-1985. Past & Present, 259(1): 229-261. [ Links ]

Dedewanou, F. and Tossou, R. 2021. Remittances and agricultural productivity in Burkina Faso. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 44(3): 1573-1590. [ Links ]

Deshingkar, P., Awumbila, M. and Teye, J. 2019. Victims of trafficking and modern slavery or agents of change? Migrants, brokers, and the state in Ghana and Myanmar. Journal of the British Academy, 7(s1): 77-106. [ Links ]

Ebadi, N., Ahmadi, D., Sirkeci, I. and Melgar-Quiñonez, H. 2018. The impact of remittances on food security status in the Global South. Remittances Review, 3(2): 135-150. [ Links ]

Eghan, M. and Adjasi, C. 2023. Remittances and agricultural productivity: The effect of heterogeneity in economic activity of farming households in Ghana. Agricultural Finance Review, 83(4/5): 821-844. [ Links ]

Feld, S. 2021. International migration, remittances and brain drain: Impacts on development. Cham: Springer Nature. [ Links ]

Foeken, D. and Owuor, S. 2001. Multi-spatial livelihoods in sub-Saharan Africa: Rural farming by urban households - the case of Nakuru town, Kenya. In De Bruijn, M., Van Dijk, R. and Foeken, D. (eds.), Mobile Africa: Changing patterns of movement in Africa and beyond. Leiden: Brill, pp. 125-140. [ Links ]

Fonta, W., Nwosu, E., Thiam, D. and Ayuk, E. 2022. The development outcomes of remittance inflows to Nigeria: The case of the Southeastern geo-political zone. Migration and Development, 11(3): 1087-1103. [ Links ]

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). 2006. Food security. Policy Brief Issue 2. FAO, Rome.

Giannelli, G. and Canessa, E. 2021. After the flood: Migration and remittances as coping strategies of rural Bangladeshi households. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 70(3): 1-55. [ Links ]

González-Ferrer A., Black, R., Kraus, E. and Quartey, P. 2013. Determinants of migration between Ghana and Europe. MAFE Working Paper No. 24. INED, Paris.

Greiner, C. 2011. Translocal networks and socio-economic stratification in Namibia. Africa: Journal of the International African Institute, 81(4): 606-627. [ Links ]

Gyimah-Brempong, K. and Asiedu, E. 2015. Remittances and investment in education: Evidence from Ghana. Journal of International Trade & Economic Development, 24(2): 173-200. [ Links ]

Headley, C., Galea, S., Nandi, V., Nandi, A., Lopez, G., Strongarone, S. and Ompad, D. 2008. Hunger and health among undocumented Mexican migrants in a US urban area. Public Health Nutrition, 11(2): 151-158. [ Links ]

High Level Panel of Experts (HLPE). 2020. Food security and nutrition: Building a global narrative towards 2030. A report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security. Rome: FAO. [ Links ]

International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). 2023. Remittances and diaspora investments are vital to boost agriculture and rural development, says IFAD President. Available at: https://www.ifad.org/en/w/news/remittances-and-diaspora-investments-are-vital-to-boost-agriculture-and-rural-development-says-ifad-president.

Kandilige, L., Teye, J., Setrana, M. and Badasu, D. 2023. "They'd beat us with whatever is available to them": Exploitation and abuse of Ghanaian domestic workers in the Middle East. International Migration, 61(4): 240-256. [ Links ]

Kandilige, L., Yaro, J. and Mensah, J. 2024. Exploring the lived experiences of Ghanaian migrants along the Ghana-China migration corridor. In Zeleke, M. and Smith, L. (eds.), African perspectives on South-South migration. London: Routledge, pp. 55-72. [ Links ]

Karamba, W., Quiñones, E. and Winters, P. 2011. Migration and food consumption patterns in Ghana. Food Policy, 36(1): 41-53. [ Links ]

Konadu-Agyeman, K. 2000. The best of times and the worst of times: Structural adjustment programs and uneven development in Africa: The case of Ghana. Professional Geographer, 52(3): 469-483. [ Links ]

Kpodar, K., Mlachika, M., Quayyum, S. and Gammadigbe, V. 2023. Defying the odds: Remittances during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Development Studies, 59(5): 673-690. [ Links ]

Kuuire, V., Mkandawire, P., Arku, G. and Luginaah, I. 2013. Abandoning farms in search of food: Food remittance and household food security in Ghana. African Geographical Review, 32(2): 125-139. [ Links ]

Le De, L., Gaillard, J. and Friesen, W. 2013. Remittances and disasters: A review. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 4: 34-43. [ Links ]

Moniruzzaman, M. 2022. The impact of remittances on household food security: Evidence from a survey in Bangladesh. Migration and Development, 11(3): 352-371. [ Links ]

Mora-Rivera, J. and Van Gameren, E. 2021. The impact of remittances on food insecurity: Evidence from Mexico. World Development, 140: 105349. [ Links ]

Obeng, M. 2019. Journey to the East: A study of Ghanaian migrants in Guangzhou, China. Canadian Journal of African Studies, 53(1): 67-87. [ Links ]

Obi, C., Bartolini, F. and D'Haese, M. 2020. International migration, remittance and food security during food crises: The case study of Nigeria. Food Security, 12(1): 207-220. [ Links ]

Osei-Kwasi, H., Nicolaou, M., Powell, K. and Holdsworth, M. 2019. "I cannot sit here and eat alone when I know a fellow Ghanaian is suffering": Perceptions of food insecurity among Ghanaian migrants. Appetite, 140, 190-196. [ Links ]

Peil, M. 1995. Ghanaians abroad. African Affairs, 94: 345-367. [ Links ]

Pendleton, W., Crush, J. and Nickanor, N. 2014. Migrant Windhoek: Rural-urban migration and food security in Namibia. Urban Forum, 25: 191-205. [ Links ]

Peth, S. 2018. What is translocality? A refined understanding of space and place in a globalized world. Available at: https://doi.org/10.34834/2019.0007.

Porter, G., Hampshire, K., Abane, A., Munthali, A., Robson, E., Tanle, A., Owusu, S., Delannoy, A. and Bango, A. 2018. Connecting with home, keeping in touch: Physical and virtual mobility across stretched families in sub-Saharan Africa. Africa, 88: 404-424. [ Links ]

Quartey, P. 2006. The impact of migrant remittances on household welfare in Ghana. AERC Research Paper 158. African Economic Research Consortium, Nairobi.

Rahman, M. and Salisu, M. 2023. Gender and the return migration process: Gulf returnees in Ghana. Comparative Migration Studies, 11: 18. [ Links ]

Ramisch, J. 2016. "Never at ease": Cellphones, multilocational households, and the metabolic rift in western Kenya. Agriculture and Human Values, 33: 979-995. [ Links ]

Regmi, M. and Paudel, K. 2017. Food security in a remittance-based economy. Food Security, 9: 831-848. [ Links ]

Rodima-Taylor, D. 2022. Sending money home in conflict settings: Revisiting migrant remittances. Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, 23(1): 43-51. [ Links ]

Sam, G., Boateng, F. and Oppong-Boakye, P. 2013. Remittances from abroad: The Ghanaian household perspective. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 4(1): 164-170. [ Links ]

Schans, D., Mazzucato, V., Schoumaker, B. and Flahaux, M. 2018. Changing patterns of Ghanaian migration. MAFE Working Paper No. 20. INED, Paris.

Schmidt-Kallert, E. and Franke, P. 2012. Living in two worlds: Multi-locational household arrangements among migrant workers in China. DIE ERDE: Journal of the Geographical Society of Berlin, 143(3): 263-284. [ Links ]

Seydou, L. 2023. Effects of remittances on food security in sub-Saharan Africa. African Development Review, 35(2): 126-137. [ Links ]

Smith, M. and Floro, M. 2021. The effects of domestic and international remittances on food insecurity in low-and middle-income countries. Journal of Development Studies, 57(7): 1998-1220. [ Links ]

Steinbrink, M. and Niedenführ, H. 2020. Africa on the move: Migration, translocal livelihoods and rural development in sub-Saharan Africa. Cham: Springer. [ Links ]

Sulemana, I., Anarfo, E. and Quartey, P. 2018. International remittances and house-hold food security in sub-Saharan Africa. Migration and Development, 8: 264-280. [ Links ]

Szabo, S., Ahmed, S., Wisniowski, A., Pramanik, M., Islam, R., Zaman, F. and Ku-womu, J. 2022. Remittances and food security in Bangladesh: An empirical country-level analysis. Public Health Nutrition, 25(10): 2886-2896. [ Links ]

Thow, A., Fanzo, J. and Negin, J. 2016. A systematic review of the effect of remittances on diet and nutrition. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 37(1): 42-64. [ Links ]

Xing, Z. 2018. Development impacts of remittances in agricultural households: Fiji experience. Remittances Review, 3(1): 19-49. [ Links ]

Zezza, A., Carletto, C., Davis, B. and Winters, P. 2011. Assessing the impact of migration on food and nutrition security. Food Policy, 36: 1-6. [ Links ]

Zingwe, D., Banda, A. and Manja, L. 2023. The effects of remittances on household food nutrition security in the context of multiple shocks in Malawi. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 9(1): 2238440. [ Links ]

Received 23 September 2024

Accepted 06 November 2024

Published 10 January 2025