Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

African Human Mobility Review

On-line version ISSN 2410-7972Print version ISSN 2411-6955

AHMR vol.10 n.3 Cape Town Sep./Dec. 2024

https://doi.org/10.14426/ahmr.v10i3.2435

ARTICLES

"An Endless Cycle of Worry and Hardship": The Impact of COVID-19 on the Food Security of Somali Migrants and Refugees in Nairobi, Kenya

Zack AhmedI; Jonathan CrushII; Samuel OwuorIII

ISchool of International Policy and Governance, Wilfrid Laurier University, Waterloo, Canada. Corresponding author zahmed@balsillieschool.ca

IIBalsillie School of International Affairs, Waterloo, Canada and University of the Western Cape, Cape Town South Africa. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3342-3192

IIIDepartment of Geography and Environmental Studies, Nairobi, Kenya. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8928-2862

ABSTRACT

COVID-19 has produced unprecedented effects on the global economy and society by exposing multiple weaknesses and faultlines. The pandemic has disrupted global and local agricultural production processes and food supply chains with negative consequences for food security. Containment measures to limit the spread of COVID-19, including strict restrictions on the movement of people, goods, and services have affected urban food systems adversely in multiple ways. Urban migrants and refugees in many parts of the Global South have been disproportionately hit by these measures, increasing the precarity of their living conditions and exacerbating the food insecurity of the migrants' households. Based on the results of a household survey and in-depth interviews with Somali migrants in Nairobi, Kenya in August 2022, this study documents the pandemic-related experience of these migrants in food access and consumption and assesses the overall impacts of COVID-19 on their food security. This study seeks to contribute to the emerging body of case study evidence that assesses the food security outcomes of the pandemic in vulnerable populations.

Keywords: COVID-19, food security, urban refugees, migration

INTRODUCTION

Cities have been labeled "Ground Zero" of the COVID-19 pandemic by the Secretary-General of the United Nations (Guterres, 2023). Urban areas, especially large cities, were hotspots of the coronavirus spread and impact because of their high population concentration, overcrowding, and poor health and living conditions (Florida et al., 2021). In major African cities such as Nairobi, the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated preexisting challenges for urban migrants and refugees, especially those with limited mobility due to their lack of legal documents (Luiu et al., 2022). Migrant and refugee vulnerability was compounded by existing inequities, exclusionary government responses, and residential segregation (Hitch et al., 2022). The situation was particularly dire in informal settlements and low-income neighborhoods, where overcrowding and lack of basic services made adherence to containment measures difficult (Kibe et al., 2020).

The Kenyan government imposed a nationwide dusk-to-dawn curfew in March 2020 restricting movement between and within urban areas (Wangari et al., 2021). These control measures led to economic slowdown, unemployment, loss of income, and reduced mobility, further worsening pre-pandemic poverty and socioeconomic vulnerability (Luiu et al., 2022; Kunyanga et al., 2023). Somali migrants and refugees in Nairobi were particularly affected by government pandemic control measures. Most Somalis live in the Eastleigh section of Nairobi, known locally as "Little Mogadishu" (Carrier, 2017; Ahmed et al., 2024). Eastleigh was officially designated by the government as one of two major COVID-19 hotspots within the country and experienced a harsher response than other parts of Nairobi (Lusambili et al., 2020). In May 2020, after a surge in cases in Nairobi concentrated in Eastleigh, the Kenyan government imposed a lockdown that involved a cessation of mobility into and out of the area for one month (Hiiraan Online, 2020; Lusambili et al., 2021). Markets and food stores, including restaurants and eateries were also shut down during this period.

By documenting the pandemic-related food security experiences of Somali migrants in Nairobi during the pandemic, this paper aims to contribute to the emerging body of case study evidence assessing the negative outcomes of the pandemic on vulnerable populations in African cities (Kassa and Grace, 2020; Durizzo et al., 2021; Chirisa et al., 2022; Nuwematsiko et al., 2022; Turok and Visagie, 2022; Bhanye et al., 2023; Dupas et al., 2023; Onyango et al., 2023). Assembling data from a household survey and in-depth interviews with Somali migrants in Eastleigh, the paper assesses the overall impact of COVID-19 on their food security. It particularly focuses on the challenges faced by Somali migrants in accessing and consuming sufficient and nutritious food during the pandemic. Thus, the paper adds a crucial layer to our understanding of the impact of the pandemic on vulnerable populations in cities of the Global South.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly disrupted food security worldwide, with pronounced consequences in the Global South where economic vulnerabilities and structural inequalities predated the crisis. Pandemic-response containment measures - including lockdowns, curfews, and trade restrictions - led to severe disruptions of agricultural production and supply chains, undermining food access and affordability across low- and middle-income countries (Laborde et al., 2020; Béné et al., 2021; Balistreri et al., 2022). In urban areas, food systems were particularly affected, as restrictions limited the movement of goods and people, stalling both formal and informal food supply networks. Low-income households and vulnerable groups, such as migrants and refugees, were disproportionately affected by these disruptions because of their dependence on informal food markets and lack of access to food reserves or alternative income sources (Béné et al., 2021; Swinnen and Vos, 2021; Bitzer et al., 2024).

In urban areas of the Global South, where daily sustenance depends on accessible and resilient food systems, the socio-economic effects of the pandemic exacerbated preexisting inequalities. Numerous studies have documented how food insecurity surged in cities where containment measures and lockdowns restricted informal trade, a critical source of food and income for low-income urban populations (Crush and Si, 2020; Resnick, 2020; Rwafa-Ponela et al., 2022; Crush and Tawodzera, 2024). These disruptions highlighted the fragility of urban food systems in these contexts, as well as the limited capacity of local governments to provide adequate food support to marginalized communities. Urban refugees in African cities encountered compounding food security challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic, as mobility restrictions, lockdowns, economic shutdowns, and exclusion from social services intensified their vulnerability (Bukuluki et al., 2020; Odunitan-Wayas et al., 2020; Moyo et al., 2021; Nyamnjoh et al., 2022; Tenerowicz and Wellman, 2024). In most cities, migrant-dense localities experienced heightened food insecurity due to the strict lockdowns that limited both physical and economic access to food sources (Resnick, 2020; Mulu and Mbanza, 2021; Luiu et al., 2022). Additionally, lack of legal documentation barred many migrants from accessing government food aid, deepening their dependence on informal networks for survival (Ahmed et al., 2023).

Social and economic inequities have long shaped food access among migrant populations in African cities, and the COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated these inequalities. Urban migrants and refugees often reside in densely populated informal settlements with limited infrastructure, where access to essential services like water, sanitation, and healthcare is minimal (Kibe et al., 2020). The pandemic worsened these conditions, as lockdowns restricted mobility, limiting migrants' ability to access food and social services. While many African governments implemented food assistance programs, migrants - especially those lacking legal documentation -were largely excluded from these initiatives (Hitch et al., 2022). In cities like Harare, Kampala, Lilongwe, and Nairobi, official pandemic responses exposed and often deepened existing inequalities, prompting grassroots strategies within communities to mitigate food and resource shortages (Sverdlik et al., 2024).

The pandemic triggered a surge in food prices across African cities, further constraining food access for financially insecure urban migrant populations. Previous studies indicate that food prices rose sharply due to supply chain disruptions and lockdown measures, with maize prices increasing by 26% to 44% in various regions (Adewopo et al., 2021; Agyei et al., 2021). In Nairobi, food prices rose by an average of 13.8%, exacerbating food insecurity among low-income households (Kunyanga et al., 2023). In addition, food price inflation affected both formal and informal markets, with staple foods subject to significant price hikes (FAO et al., 2020). This spike in prices meant that even when food was available, affordability became a significant barrier for migrants in urban African settings.

In Nairobi, the growing literature on COVID-19 has focused on the vulnerability of households to pandemic shocks (Onyango et al., 2021), the impact of travel restrictions on mobility patterns (Pinchoff et al., 2021b; Kasuku et al., 2022), the income hit for small informal food enterprises (Chege et al., 2021; Moochi and Mutswenje, 2022; Mwangi and Mwaura 2023), food supply chain disruptions (Alonso et al., 2023; Kunyanga et al., 2023), and economic hardships in the city's informal settlements (Nyadera and Onditi, 2020; Quaife et al., 2020; Pinchoff et al., 2021a; Joshi et al., 2022; Solymári et al., 2022). Some attention has also been paid to the impact of the pandemic on food security in the informal settlements and other low-income areas of the city (Mbijiwe et al., 2021; Merchant et al., 2022).

One survey of over 2,000 Nairobi households found that 90% of households were in a dire food insecurity situation, including being unable to eat preferred kinds of food, eating a limited variety of foods, consuming smaller portions than they felt they needed, and eating fewer meals in a day (Chege et al., 2022). Onyango et al. (2024) note that only 38% of informal settlement households had consistently acceptable diets, while another two-thirds (61%) fluctuated between acceptable and unacceptable diets. Shupler et al. (2021) report that there was an almost universal (95%) income decline in an informal settlement during the lockdown, leading to 88% of households reporting food insecurity. Household response strategies included changing consumption activities, reorganizing household finances, reducing urban household size, prioritizing children's access to food, depending on social networks, and relying on household food production.

The small cluster of studies on the pandemic experiences of migrants and refugees in Nairobi have focused on disruption to their transnational networks and the strengthening of local social relations of mutuality and support (Müller, 2022, 2023; Shizha, 2023). Other studies suggest that the pandemic widened gaps in social services and healthcare and depressed social support within Nairobi's refugee community (Tenerowicz and Wellman, 2024). To date, the impact of the pandemic on migrant and refugee food security is a notable gap in the literature. Previous research has indicated that the economic effects of the lockdown were felt acutely by Somali migrants in Nairobi, many of whom also work as informal vendors (Doll and Golole, 2023). With lockdown measures in place, both food availability and income sources diminished, leaving the community in a precarious state (Lusambili et al., 2021). However, this is the first study we know of to systematically examine the impact of the pandemic on the food security of urban migrants and refugees from Somalia living in Eastleigh, Nairobi.

METHODOLOGY

This study was conducted in Nairobi's Eastleigh section, with its predominantly Somali population and cultural identity. Eastleigh itself is a densely populated area that serves as a residential, commercial, and social hub for Somali migrants and refugees, making it a critical site for examining the food security challenges faced by this population. The study employed a mixed-methods approach to capture the complexity of food security dynamics among Somali households during the COVID-19 pandemic. The research team selected households through random sampling to ensure a fair representation of migrant households in Eastleigh. Random sampling ensured that a variety of household structures, economic status, and food security experiences were captured. As the area houses migrants from Somalia and Somali Kenyans, the research team employed a screening question to identify households with a Somalia-born head. The search yielded 268 households from an overall sample of 318. This paper therefore reports on the findings from the survey of these 268 households.

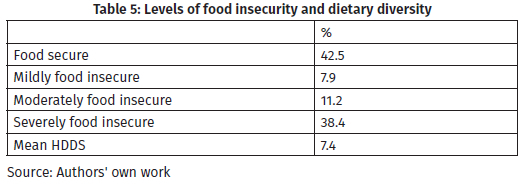

First, the research team administered a structured quantitative household survey to the sampled households, collecting data on demographics, food security levels, economic conditions, and pandemic-related experiences. The team analyzed quantitative data using descriptive statistical methods to summarize household characteristics, food security levels, and the economic impacts of the pandemic. Researchers assessed food security using a combination of indicators, including the Household Dietary Diversity Score (HDDS), the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS), and the Household Food Insecurity Access Prevalence (HFIAP) indicator. The HDDS captures dietary diversity as a proxy for the nutritional value of the diet, while the HFIAS and HFIAP assess the prevalence and severity of food insecurity (Swindale and Bilinsky, 2006; Coates et al., 2007).

Second, the research team conducted 30 qualitative in-depth interviews with Somali migrant household heads to capture detailed personal narratives of food access challenges, coping strategies, and broader socio-economic impacts of the pandemic. These interviews were conducted in Somali, Swahili, or English by trained local research assistants with contextual and linguistic expertise. Finally, the team conducted 15 key informant interviews with community leaders, business representatives, and organizers to provide broader insights into the economic and social dynamics influencing food security in Eastleigh. The researchers analyzed the qualitative data from the in-depth and key informant interviews thematically to identify recurring patterns and narratives related to food insecurity, economic disruptions, and coping strategies.

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

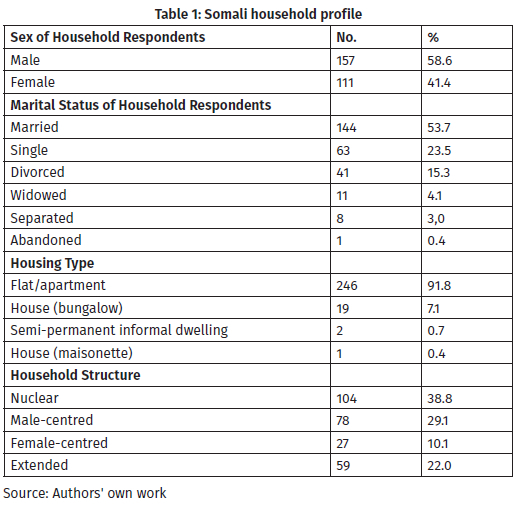

Table 1 provides a profile of the respondents and households surveyed. Of the respondents, 59% were male and 41% female, with just over half married and a quarter single. Somali households in Eastleigh live predominantly in flats or apartments, reflecting the dense urban environment of the area. Nuclear (39%) and male-centered (29%) households predominated, with only 10% being female-centered (defined as a household with a female head without a spouse or partner in the household).

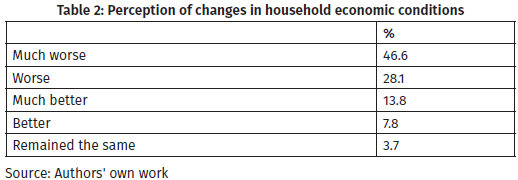

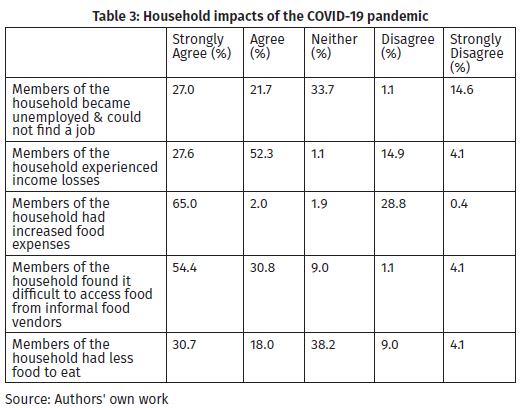

Three-quarters of the survey respondents said their households were economically worse ofl' than before the pandemic. Only 22% said their conditions had improved. The reasons for this pandemic shock are evident from Table 2. Almost half of the households had household members losing their jobs and unable to find work (see Table 3). As many as 80% of the participants reported that their households experienced a loss of income. The high level of job loss is reflected in the closure of businesses and the halt in economic activities because of the lockdown and other restrictions. However, this was not the only reason for reduced income, as many households in Eastleigh derive income from running an informal business, and the shutdown of these enterprises affected their sales and income directly.

Two-thirds of the Somali households experienced an increase in food expenses during the pandemic (see Table 3). The increase can be attributed to disrupted food supply chains, which particularly affected communities relying on informal food sources. Informal food networks play a central role in the urban food security of migrant communities such as this, and disruptions can severely limit access to necessary food supplies. The difficulty in accessing food from informal vendors was pronounced, with 85% of households funding it harder to obtain food this way during the pandemic.

The survey findings provide a lens through which to interpret the subjective experiences relayed by respondents during the in-depth interviews. For example, one Somali refugee lost his job as a shopkeeper and was forced to lay low during the pandemic for fear of being assaulted or arrested:

COVID-19 really affected our household, especially in 2020 and 2021. I lost my job working as a shopkeeper in Eastleigh, Nairobi, due to COVID-19. I could not also move freely to look for a job due to COVID-19 containment measures. Police used to arrest and beat people who are found walking outside. For someone like me with refugee documents, I could not move freely, as I could easily get arrested. Therefore, I had to stay at home for most of the pandemic period. In addition, the living condition is now harder than before the pandemic. Everything is expensive, and the price of foodstuffs has gone up. The tough economic conditions have had negative effects on my household's food security situation (Interview No. 16).

In this case, the suffering was clearly compounded by his being unable to look for other employment and by the increase in the cost of food. Another respondent faced a similar situation when the shop in which they worked shut down and they lost their job. Efforts to find another job proved fruitless:

Before COVID-19, I worked in a wholesale food shop to support my wife and our four kids. I was the sole breadwinner of my family, and my income was essential for us to survive. When the pandemic hit, the shop was closed due to lockdown measures, and I lost my job. With no income, we really struggled to put food on the table. Every day was a battle to find enough to eat and make ends meet. The situation was dire, and I often felt helpless. Our savings quickly ran out, and there was no work to be found. The impact on our lives was devastating, and it felt like we were trapped in an endless cycle of worry and hardship (Interview No. 19).

This recollection of the negative impact of the pandemic is indicative of a significant deterioration in food security and general well-being among the Somali migrants. The closure of informal markets not only restricted food access, but also further marginalized already vulnerable populations, amplifying the food security crisis among urban migrants. One respondent recalled how the closure of shops made food access a challenge:

We rely heavily on informal food vendors for our daily sustenance, buying cheap groceries and fresh produce to feed our families. However, during the pandemic, Eastleigh was considered a hotspot, and the government closed all food-vending shops. This made it incredibly difficult for us to access food. The closure of these vendors, who are our primary source for affordable and fresh food, left us struggling. We couldn't buy the groceries and produce we needed, and the alternatives were either too expensive or inaccessible. It was a challenging time for all of us, and at times [we] went hungry because we simply couldn't afford the higher prices in the formal supermarkets (Interview No. 23).

As Table 3 shows, nearly half of the surveyed households reported having less food to eat during the pandemic. The restrictions on informal vending also had negative implications for households that relied on income from street vending:

Before the pandemic, I worked as an informal food vendor, selling meat and groceries in Eastleigh's Jam Street. This job was our main source of income and helped me support my family. When COVID-19 hit, everything changed. The market was shut down, and movement was heavily restricted. I couldn't sell produce anymore, and our income disappeared overnight. To make things worse, the cost of food went up significantly. As a vendor, I saw firsthand how the disrupted supply chains and increased market prices affected everyone. People who used to buy from me struggled to afford basic groceries. My family was no different; we had to pay more for the food we needed, but we had no income to cover these expenses. It was a constant struggle to make ends meet, and every day felt like a battle for survival (Interview No. 30).

Food price inflation in Kenya exacerbated the challenges faced by Somali migrants, who typically have limited financial reserves and rely heavily on the informal sector for their food (Ahmed et al., 2023). However, loss of income and food inflation were far from being the only livelihood challenges. In addition to food insecurity, many faced challenges paying for services such as water and electricity:

In Eastleigh, we usually live in a densely populated neighborhood that is both commercial and residential. We purchase everything, including food, water, and electricity. During COVID-19, there was a heavy crackdown with strict restrictions on movement in and out of the neighborhood. This made life extremely difficult for us, as we were deprived of most essentials.

We frequently went without sufficient food, and getting clean water became a struggle. The prices of everything went up, and there were times when we had no electricity because we couldn't afford to pay for it. The restrictions isolated us from our usual sources of support and supply, leaving many families in a state of constant need and anxiety (Interview No. 25).

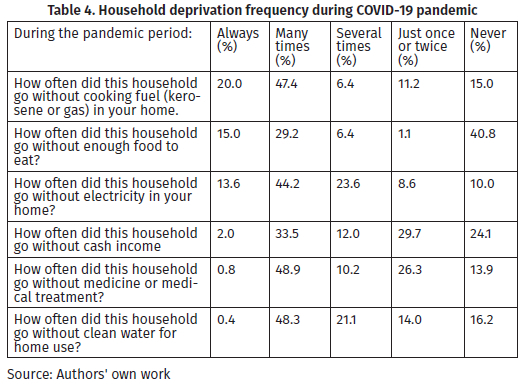

In many cases, households experienced multiple deprivations, as evidenced by the testimony of this respondent. To understand the broader impact of the pandemic restrictions, the research team used the Lived Poverty Index (LPI), which provides data on the frequency with which households were deprived of a range of necessities. Table 4 shows that significant sections of the Somali migrant community faced critical shortages. For example, 44% of households reported always or frequently going without sufficient food and almost half struggled with inconsistent access to clean water and medical treatment. Access to electricity and cooking fuel was also significantly disrupted, and most households faced these challenges during the pandemic period.

Table 5 illustrates the stark reality of food insecurity among Somali migrant households in Nairobi. Almost 60% of the households experienced some level of food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic, with severe food insecurity affecting 38% of households. This finding underscores the compounded effects of economic disruptions, inflation in food prices, and the collapse of informal food networks during the pandemic. The high prevalence of severe food insecurity not only highlights the precarious living conditions of Somali migrants but also points to systemic inequities in urban food systems that disproportionately impact marginalized groups during crises.

CONCLUSION

The findings reported in this paper illuminate the significant and multi-dimensional challenges brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic for Somali migrants in Nairobi. The research uncovered a complex tapestry of economic, health, and social challenges intricately woven into the lives of these individuals, reflecting a microcosm of the broader systemic issues faced by vulnerable urban communities across the Global South. Moreover, the individual narratives of hardship recounted in the in-depth interviews, emphasize the human dimension of the pandemic's toll and reflect the urgency for compassionate and comprehensive policy measures.

As researchers continue to navigate the pandemic's impacts and aftermath, the experiences detailed by Somali migrants in this paper serve as a poignant illustration of the extensive challenges that lie ahead for similar communities. They underscore the need for policies that address not only immediate food distribution and health concerns but also the underlying structural inequities, exacerbated by the pandemic. The evidence presented in this paper highlights the acute need for targeted interventions designed to bolster food security and foster economic resilience within urban refugee populations. These interventions must address the multi-layered impact of the pandemic, acknowledging the vulnerability of migrants to the shutdown of informal economies and the subsequent tightening of food environments. Future research is imperative and should aim to build on these findings, enhancing our strategies to ensure the well-being of migrants. Such work should not only offer relief during global crises but also pave the way for long-term resilience and stability, providing a roadmap for the recovery of migrant communities in the Global South.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge SSHRC Partnership Grant No. 895-2021-1004 for funding the research on which this paper is based.

REFERENCES

Adewopo, J., Solano-Hermosilla, G., Colen, L. and Micale, F. 2021. Using crowd-sourced data for real-time monitoring of food prices during the COVID-19 pandemic: Insights from a pilot project in northern Nigeria. Global Food Security, 29: 100523. [ Links ]

Agyei, S., Isshaq, Z., Frimpong, S., Adam, A., Bossman, A. and Asiamah, O. 2021. COVID-19 and food prices in sub-Saharan Africa. African Development Review, 33(S1): S102-S113. [ Links ]

Ahmed, D., Benavente, P. and Diaz, E. 2023. Food insecurity among international migrants during the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(7): 5273. [ Links ]

Ahmed, Z., Crush, J., Owuor, S. and Onyango, E. 2024. Disparities and determinants of Somali refugee food security in Nairobi, Kenya. Global Food Security, 43: 100808. [ Links ]

Alonso, S., Angel, M., Muunda, E., Kilonzi, E., Palloni, G., Grace, D. and Leroy, J. 2023. Consumer demand for milk and the informal dairy sector amidst COVID-19 in Nairobi, Kenya. Current Developments in Nutrition, 7: 100058. [ Links ]

Balistreri, E., Baquedano, F. and Beghin, J. 2022. The impact of COVID-19 and associated policy responses on global food security. Agricultural Economics, 53(6): 855-869. [ Links ]

Béné, C., Bakker, D., Chavarro, M., Even, B., Melo, J. and Sonneveld, A. 2021. Global assessment of the impacts of COVID-19 on food security. Global Food Security, 31: 100575. [ Links ]

Bhanye, J., Mangara, F., Matamanda, A. and Kachena, L. 2023. COVID-19 lockdowns and the urban poor in Harare, Zimbabwe. Cham: Springer. [ Links ]

Bukuluki, P., Mweyango, H., Katongole, S., Sidhva, D. and Palattiyil, G. 2020. The socio-economic and psychosocial impact of COVID-19 pandemic on urban refugees in Uganda. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 2(1): 100045. [ Links ]

Carrier, N. 2017. Little Mogadishu: Eastleigh, Nairobi's global Somali hub. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Chege, C., Mbugua, M., Onyango, K. and Lundy, M. 2021. Keeping food on the table: Urban food environments in Nairobi under COVID-19. CIAT Publication No. 514. International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT). Nairobi, Kenya.

Chege, C., Onyango, K., Kabach, J. and Lundy, M. 2022. Effects of COVID-19 on dietary behavior of urban consumers in Nairobi, Kenya. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 6: 718443. [ Links ]

Chirisa, I., Mutambisi, T., Chivenge, M., Mabaso, E., Matamanda, A. and Ncube, R. 2022. The urban penalty of COVID-19 lockdowns across the globe: Manifestations and lessons for Anglophone sub-Saharan Africa. GeoJournal, 87: 815-828. [ Links ]

Coates, J., Swindale, A. and Bilinsky, P. 2007. Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for measurement of food access: Indicator guide (Version 3). Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project, Academy for Educational Development, Washington, DC.

Crush, J. and Si, Z. 2020. COVID-19 containment and food security in the Global South. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, 9(4): 149-151. [ Links ]

Crush, J. and Tawodzera, G. 2024. Informal pandemic precarity and migrant food enterprise in South Africa during COVID-19. Global Food Security, 43: 100804. [ Links ]

Doll, Y. and Golole, A. 2023. The impact of COVID-19 restrictions on Kenya's international trade relations: A case of Eastleigh Market, Kamukunji, Nairobi County. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 13(3): 104-110. [ Links ]

Dupas, P., Fafchamps, M. and Lestant, E. (2023). Panel data evidence on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on livelihoods in urban Côte d'Ivoire. PLoS ONE, 18(2): e0277559. [ Links ]

Durizzo, K., Asiedu, E., Van der Merwe, A., Van Niekerk, A. and Günther, I. 2021. Managing the COVID-19 pandemic in poor urban neighborhoods: The case of Accra and Johannesburg. World Development, 137: 105175. [ Links ]

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO. 2020. The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2020: Transforming food systems for affordable healthy diets. Rome: FAO. [ Links ]

Florida, R., Rodriguez-Pose, A. and Storper, M. 2021. Critical commentary: Cities in a post-COVID world. Urban Studies, 60(8). [ Links ]

Guterres, A. 2023. COVID-19 in an urban world. Policy brief. Available at: https://www.un.org/en/coronavirus/covid-19-urban-world.

Hiiraan Online. 2020. Nairobi's Eastleigh in lockdown as COVID-19 cases rise sharply. Available at: https://www.hiiraan.com/news4/2020/May/178048/nairobi_s_eastleigh_on_lockdown_as_covid19_rise_sharply.aspx.

Hitch, L., Cravero, K., Masoud, D., Moujabber, M. and Hobbs, L. 2022. The vulnerability of migrants living in large urban areas to COVID-19: Exacerbators and mitigators. European Journal of Public Health, 32(Supplement_3). [ Links ]

Joshi, N., Lopus, S., Hannah, C., Ernst, K., Kilungo, A., Opiyo, R., Ngayu, M., ... et al. 2022. COVID-19 lockdowns: Employment and business disruptions, water access and hygiene practices in Nairobi's informal settlements. Social Science & Medicine, 308: 115191. [ Links ]

Kassa, M. and Grace, J. 2020. Race against death or starvation? COVID-19 and its impact on African populations. Public Health Review, 41: 30. [ Links ]

Kasuku, S., Akatch, S., Gichaga, F., Opiyo, R. and Musyoka, R. 2022. Impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on accessibility in Nairobi City. Africa Habitat Review Journal, 17(1): 2549-2562. [ Links ]

Kibe, P., Kisia, L. and Bakibinga, P. 2020. COVID-19 and community healthcare: Perspectives from Nairobi's informal settlements. The Pan African Medical Journal, 35(Suppl 2): 106. [ Links ]

Kunyanga, C., Byskov, M., Hyams, K., Mburu, S., Werikhe, G. and Bett, R. 2023. Influence of COVID-19 pandemic on food market prices and food supply in urban markets in Nairobi, Kenya. Sustainability, 15(2): 1304. [ Links ]

Laborde, D., Martin, W. and Vos, R. 2020. Poverty and food insecurity could grow dramatically as COVID-19 spreads. International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). Available at: https://www.ifpri.org/blog/poverty-and-food-insecurity-could-grow-dramatically-covid-19-spreads/.

Luiu, C., Wandera, A., Radcliffe, J., Pope, F., Bukachi, V. and Mulligan, J. 2022. COVID-19 impacts on mobility in Kenyan informal settlements: A case study from Kibera, Nairobi. Findings, August.

Lusambili, A., Martini, M., Abdirahman, F., Abena, A., Ochieng, S., Guni, J.N., Maina, R., ... et al. 2020. "We have a lot of home deliveries": A qualitative study on the impact of COVID-19 on access to and utilization of reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health care among refugee women in urban Eastleigh, Kenya. Journal of Migration & Health, 1-2: 100025. [ Links ]

Lusambili, A., Martini, M., Abdirahman, F., Abena, A., Guni, J., Ochieng, S. and Luchters, S. 2021. "It is a disease which comes and kills directly": What refugees know about COVID-19 and key influences of compliance with preventive measures. PLoS One, 16(12): e0261359. [ Links ]

Mbijiwe, J., Kiiru, S., Konyole, S., Ndungu, N. and Kinyuru, J. 2021. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on food consumption pattern in the population of Nairobi, Kenya. Journal of Agriculture, Science and Technology, 20(3): 16-26. [ Links ]

Merchant, E., Fatima, T., Fatima, A., Maiyo, N., Mutuku, V., Keino, S., Simon, J., ... et al. 2022. The influence of food environments on food security resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic: An examination of urban and rural difference in Kenya. Nutrients, 14: 2939. [ Links ]

Moochi, J. and Mutswenje, V. 2022. COVID-19 containment measures and financial performance of small and medium enterprises in Nairobi CBD, Kenya. International Academic Journal of Economics and Finance, 3(7): 403-436. [ Links ]

Moyo, K., Sebba, K. and Zanker, F. 2021. Who is watching? Refugee protection during a pandemic: Responses from Uganda and South Africa. Comparative Migration Studies, 9: 37. [ Links ]

Müller, T. 2022. COVID-19 and urban migrants in the Horn of Africa: Lived citizenship and everyday humanitarianism. IDS Bulletin, 53(2): 11-26. [ Links ]

Müller, T. 2023. Transnational lived citizenship turns local: COVID-19 and Eritrean and Ethiopian diaspora in Nairobi. Global Networks, 23(1): 106-119. [ Links ]

Mulu, N. and Mbanza, K. 2021. COVID-19 and its effects on the lives and livelihoods of Congolese female asylum seekers and refugees in the City of Cape Town. African Human Mobility Review, 7(1): 46-67. [ Links ]

Mwangi, I. and Mwaura, A. 2023. Impacts of COVID-19 containment measures on informal neighbourhoods in Nairobi City County. Africa Habitat Review Journal, 18(1): 2513-2524. [ Links ]

Nuwematsiko, R., Nabiryo, M., Bomboka, J., Nalinya, S., Musoke, D., Okello, D. and Wanyenze, R. 2022. Unintended socio-economic and health consequences of COVID-19 among slum dwellers in Kampala, Uganda. BMC Public Health, 22: 1-13. [ Links ]

Nyadera, I. and Onditi, F. 2020. COVID-19 experience among slum dwellers in Nairobi: A double tragedy or useful lesson for public health reforms? International Social Work, 63(6): 838-841. [ Links ]

Nyamnjoh, H., Hall, S. and Cirolia, L. 2022. Precarity, permits, and prayers: "Working practices" of Congolese asylum-seeking women in Cape Town. Africa Spectrum, 57(1): 30-49. [ Links ]

Odunitan-Wayas, F., Alaba, O. and Lambert, E. 2020. Food insecurity and social injustice: The plight of urban poor African immigrants in South Africa during the COVID-19 crisis. Global Public Health, 16(1):149-152. [ Links ]

Onyango, E., Crush, J. and Owuor, S. 2021. Preparing for COVID-19: Household food insecurity and vulnerability to shocks in Nairobi, Kenya. PLOS ONE 16(11): e0259139. [ Links ]

Onyango, E., Owusu, B. and Crush, J. 2023. COVID-19 and urban food security in Ghana during the third wave. Land, 12: 504. [ Links ]

Onyango, K., Kariuki, L., Chege, C. and Lundy, M. 2024. Analysis of responses to effects of COVID-19 pandemic on diets of urban slum dwellers in Nairobi, Kenya. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 10(1): 2336691. [ Links ]

Pinchoff, J., Austrian, K., Rajshekhar, R., Abuya, T., Kangwana, B., Ochako, R., Tidwell, J., ... et al. 2021a. Gendered economic, social and health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and mitigation policies in Kenya: Evidence from a prospective cohort survey in Nairobi informal settlements. BMJ Open, 11(3): e042749. [ Links ]

Pinchoff, J., Kraus-Perrotta, C., Austrian, K., Tidwell, J., Abuya, T., Mwanga, D., Kangwana, B., ... et al. 2021b. Mobility patterns during COVID-19 travel restrictions in Nairobi urban informal settlements: Who is leaving home and why. Journal of Urban Health, 98: 211-221. [ Links ]

Quaife, M., Van Zandvoort, K., Gimma, A., Shah, K., McCreesh, N., Prem, K., Barasa, E., ... et al. 2020. The impact of COVID-19 control measures on social contacts and transmission in Kenyan informal settlements. BMC Medicine, 18: 316. [ Links ]

Resnick, D. 2020. COVID-19 lockdowns threaten Africa's vital informal urban food trade. In Swinnen, J. and McDermott, J. (eds.), COVID-19 and global food security, Part four: Food trade. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), pp. 73-74. [ Links ]

Rwafa-Ponela, T., Goldstein, S., Kruger, P., Erzse, A., Abdool Karim, S. and Hofman, K. 2022. Urban informal food traders: A rapid qualitative study of COVID-19 lockdown measures in South Africa. Sustainability, 14(4): 2294. [ Links ]

Shizha, E. 2023. Transnational lives and the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on immigrants and refugees. In Shizha, E. and Makwarimba, E. (eds.), Immigrant lives: Intersectionality, transnationality, and global perspectives. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 436-459. [ Links ]

Shupler, M., Mwitari, J., Gohole, A., Anderson de Cuevas, R., Puzzolo, E., Cukic, I., Nix, E., ... et al. 2021. COVID-19 impacts on household energy and food security in a Kenyan informal settlement: The need for integrated approaches to the SdGs. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 144: 11l0l8. [ Links ]

Solymári, D., Kairu, E., Czirják, R. and Tarrósy, I. 2022. The impact of COVID-19 on the livelihoods of Kenyan slum dwellers and the need for an integrated policy approach. PLoS ONE, 17(8): e0271196. [ Links ]

Sverdlik, A., Dzimadzi, S., Ernstson, H., Kimani, J., Koyaro, M., Lines, K., Luka, Z., ... et al. 2024. African cities in the wake of Covid-19: Tracing multiple inequalities, official responses and grassroots strategies in Harare, Kampala, Lilongwe and Nairobi. ACRC Working Paper 2024-10. University of Manchester, Manchester, UK.

Swindale, A. and Bilinsky, P. 2006. Household Dietary Diversity Score (HDDS) for measurement of household food access: Indicator guide (Version 2). Washington, DC, Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project, Academy for Educational Development. [ Links ]

Swinnen, J. and Vos, R. 2021. COVID-19 and impacts on global food systems and household welfare. Agricultural Economics, 52(3): 365-374. [ Links ]

Tenerowicz, G. and Wellman, E. 2024. The social impact of COVID-19 on migrants in urban Africa. Urban Forum, 35: 433-449. [ Links ]

Turok, I. and Visagie, J. (2022). The divergent pathways of the pandemic within South African cities. Development Southern Africa, 39(5): 738-761. [ Links ]

Wangari, E., Gichuki, P., Abuor, A., Wambui, J., Okeyo, S., Oyatsi, H., Odikara, S., ... et al. 2021. Kenya's response to the COVID-19 pandemic: A balance between minimizing morbidity and adverse economic impact. AAS Open Research, 4: 3. [ Links ]

Received 23 September 2024

Accepted 23 November 2024

Published 10 January 2025