Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Scientia Militaria: South African Journal of Military Studies

On-line version ISSN 2224-0020Print version ISSN 1022-8136

SM vol.52 n.3 Cape Town 2024

https://doi.org/10.5787/52-3-1484

ARTICLES

Illicit Activities and Border Control in Ngoma, Namibia

Charlene Bwiza Simataa ; Loide Shaamhula; Geldenhuys Johannes

Department of Military Studies, Faculty of Agriculture, Engineering and Natural Sciences, University of Namibia, Windhoek, Namibia

ABSTRACT

Ensuring border security and control is essential for maintaining national peace and stability, as it involves security forces monitoring border areas to safeguard communities. The Ngoma border faces difficulties, sharing boundaries with Zambia and Botswana. The current study explored key illegal activities, their effects on the community, and the existing border control measures and challenges. Despite the established border control efforts, significant illicit activities persist in Ngoma. Using a purposive sampling approach, the research obtained data through individual interviews and focus groups discussions with members of the Namibian Police Force, the Namibian Defence Force, Customs and Immigration officials, and community residents. The data were analysed through thematic analysis, revealing that, despite existing control measures, activities, such as poaching, illegal fishing, smuggling, and unauthorised border crossings, remain prevalent. The findings further indicate that border control in the area appears ineffective, largely due to a shortage of adequately trained personnel, limited screening equipment, and a lack of essential resources, such as patrol vehicles and aerial surveillance systems. Based on these insights, border control at Ngoma can be enhanced by integrating modern technologies, such as biometric identification, automated license plate recognition, and drones to improve efficiency and security. Furthermore, implementing training and capacity-building programmes for border law enforcement and customs officers would be advantageous. Engaging local communities through community policing also strengthens relationships between law enforcement and residents. Additionally, regional collaboration with neighbouring countries could help reduce illicit border activities and build stronger diplomatic connections.

Keywords: Border Security, Illicit Border Activities, Ngoma Area, Namibia, Human Trafficking, Illegal Migration

Introduction

Borders are lines separating two countries (Fischer, Achermann & Dahinden, 2020). One of the main forms of border demarcation is fencing along the borderlines of inland countries (Leutloff-Grandits & Wille, 2024). The current borders of Africa are a product of a complicated history marked by colonialism, political conspiracy, and power struggles (Thomson, 2022). Many of these borders were drawn without any consideration for preexisting cultural or ethnic boundaries (Sciortino, Cvajner & Kivisto, 2024). Unfortunately, this has resulted in numerous conflicts and challenges for the continent, especially for the border communities. These challenges include political instability, violence, economic disparities, ethnic tensions, and religious differences (Harff & Gurr, 2018). Border demarcation comes with issues of land and grazing rights, citizenship, and territory consideration as well as the involvement of several groups with different interests in borders (Byrne, Nightingale & Korf, 2017). It is therefore important to consider the varied interests of different parties, as they pose a threat to the security of the countries, particularly in border areas (Byrne, Nightingale & Korf, 2017).

The border areas, although often thought of as mere geographical dividers, can provide opportunities for a range of illegal activities to thrive. These activities include illegal crossing, smuggling of goods, human trafficking, and illegal wildlife trade (Rohilie, 2020). According to Vilks and Kipane (2018), illicit activities are activities not allowed by law or the social customs of a country. These activities pose a significant threat to national security, socio-economic stability, and public health. Illicit activities are driven by various factors, such as poverty, unemployment, and limited economic opportunities (Vitvitskyi, Syzonenko & Titochka, 2022). Such activities are prevalent in regions close to country borders, such as Ngoma in Namibia. Ngoma shares borders with Botswana and Zambia, a transnational region positioned on the geographical, political, and social margins of a succession of pre-colonial, colonial, and postcolonial states (Jacobs, 2014; Ndumba, Shikangalah & Becker, 2021). It falls within the Caprivi strip, which has routinely been cut off and re-inserted into Namibia due to political tension before Namibian independence in 1990 (Zeller, 2009). After independence, the border demarcation separated families in the area as the same family could find itself in Namibia with another half in Botswana leading to complex cross-border dynamics. As a result, the movement of both nationals visiting their families on the respective sides of the borderline became frequent. These movements provide both opportunities and challenges for Namibian and Botswana authorities in exercising control of their border areas.

Ngoma is faced with several illicit activities, such as illegal fishing, illegal crossing, smuggling of goods, and wildlife poaching, due to its geographical location. Moreover, its rural setting is associated with a high level of poverty, unemployment, and limited economic opportunities, which lead to an increase in crimes and illicit practices. This trend necessitates the need for border control.

Border control is defined as a means of control measures regulating the movement of people and goods as provided for in the national laws and regulations of nations (Fischer, Achermann & Dahinden, 2020). Wagner (2021) defines border control as a situational awareness of the border security measures that impede the ability of criminal activities effectively. To uphold the national laws and border regulations, Namibia has three border protection units, namely the Department of Immigration Control and Citizenship (DICC) under the Ministry of Home Affairs, Immigration, Safety and Security; the Namibian Agronomic Board (NAB); and the Special Field Force (SFF) under the Namibian Police.

Additionally, the Namibian government enacted the Immigration Control Act (No. 7 of 1993) and the One-Stop Border Posts Control Act (No. 8 of 2017) as some of the legislation guiding border control in Namibia.

• The Immigration Control Act (No. 7 of 1993) serves '[t]o regulate and control the entry of persons into, and their residence in, Namibia; to provide for the removal from Namibia of certain immigrants; and to provide for matters incidental thereto'.

• The One-Stop Border Posts Control Act (No. 8 of 2017) aims '[t]o provides for the conclusion of agreements with adjoining States on the establishment and implementation of one-stop border posts; and to provide for incidental matters'.

Understanding the efficacy of border control measures in combating illicit activities in Ngoma is vital for enhancing security and stability in the area. Countries have measures, such as border patrols, inspections, and border post-checking, to combat illicit activities (Simmons & Kenwick, 2022). The current study analysed the nature of illicit activities in the Ngoma area and the consequences of these activities on the communities. It outlined the border control measures, identified the gaps and challenges encountered by law enforcement agencies, and proposed recommendations for improving border control measures in the area. This article firstly reports on the literature applicable to the study, then it explains the data and methods used to gather information for the study. Thirdly, the findings are discussed, and the article concludes by offering recommendations to improve border control and monitoring at Ngoma.

African Borders

Literature indicates that African countries are increasingly facing the daunting task of managing their borders in ways that secure their territorial sovereignty and integrity (Kamidza, 2017). While the continent has put some efforts into managing border issues, border security in Africa remains a serious concern. African border security issues are unique when compared to other regions of the world, as they face increased volumes of cross-border trading and movements of people in search of greener pastures (Ombara, 2021). This is the result of economic growth, urbanisation, and organised crime activities that continue to put enormous pressure on African border control systems. While this is true, only a few African countries have actively implemented border security strategies that secure and promote peaceful border movements. This lack of security measures has largely contributed to the prevalence of threats, such as cross-border crimes, human trafficking, smuggling of illegal goods, and money laundering (Omoniyi, 2023). These realities give urgency to African countries to put in place effective border management systems that would minimise border tensions and, at the same time, promote joint enforcement and surveillance efforts. There is therefore a need for infrastructural development, collaborations, improved communication, and information exchange to promote a sense of security and well-being across borders.

Factors Influencing Border Security in Africa

Scholars, such as Carter and Poast (2017), Kacowicz, Lacovsky and Wajner (2020), as well as Zou, Bhuiyan, Crovella and Paiano (2024) highlight the prevalence of illicit border activities in various regions worldwide, emphasising the adverse effects on security, governance, and economic instability. In Africa, several dominant factors are found that hinder border security, such as the lack of cooperation, technology, and corruption (Fakhrzad, Yazdi-Feyzabadi & Fakhrzad, 2024; Motseki & Mofokeng, 2022). In the African context, cooperation, and coordination among stakeholders in border security are minimal at local, regional, and national levels. For example, at a local level, border management efforts are mainly focused on the security sector personnel, and the local communities are left out despite their knowledge of the border area (Udosen & Uwak, 2021). At a national level, there is also little to no integration among different divisions of immigration, customs, police, military, and intelligence (Robbing, 2016). This has been found to hinder effective border security efforts.

At a regional level, border control is observed among border countries that need to work together to enhance security by sharing intelligence information and undertaking joint border patrols among others (Wagner, 2021). As observed by Minnaar (2022), border control requires coordinated effort at all levels to ensure effective border security and control. As well as the advancement of technology, it has become necessary for developing nations to adapt to the changing landscape of technology. The lack of technology was therefore identified as one of the hindering factors in terms of border security and control -especially in African countries (Kuteyi & Winkler, 2022). The incorporation and adoption of technology in border security and control allow for the rapid detection and interception of illicit goods, as well as the collection, organisation, and dissemination of data. In many developed countries, the integration and use of advanced technology in border security and control has revolutionised the way illicit activities are detected and addressed (Blundell, 2020). These technologies include tools and devices for border surveillance, such as high-resolution cameras, drones, and sensors, which provide real-time insights into suspicious activities. In the same light, biometric scanners verify travellers' identities and detect their backgrounds (Blundell, 2020).

Besides co-operation and technological improvement, corruption was also found to be a concerning issue that could undermine the effectiveness of security measures and facilitate various illicit activities. As cited by Ortiz (2021), bribery and corruption are often witnessed among border personnel in their interaction with the offenders . This prevalence of corruption in border control agencies is attributed to a lack of supervision and monitoring mechanisms, low salaries, and poor working conditions, a lack of proper training in border control, and a lack of border regulations and procedures (Klopp, Trimble & Wiseman, 2022). In many developing countries, corruption is aggravated by low remuneration, poor infrastructure, poor working conditions, and a lack of capacity (Chikanda & Tawodzera, 2017). In Namibia, for example, border posts are understaffed, and they lack modern tools and devices for effective border policing, inspections, and checks. Addressing these challenges to uphold the integrity of border control systems requires collaborative efforts between national institutions, law enforcement agencies, community members, and international partners.

Case Study: Namibia-Botswana Border Dispute

Borders provide points of contact and opportunities for interactions between countries (Namibia shares borders with Angola, South Africa, Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Botswana), but they can also be a source of conflicts and tension. In the Ngoma area, which is an area on the border with Botswana, several disputes have been observed over the years, such as the ownership of Kasikili/Sedudu Island and the conflict over wild animals crossing the border. Le Roux (1999) highlights the tensions between Namibia and Botswana over Kasikili/Sedudu Island ownership. While the border was determined by the special agreement known as the Anglo-German Treaty signed in July 1890, the current border dispute persisted until 1996 due to conflicting perceptions and positions at the International Court of Justice (ICJ). The case was concluded in 1999 in favour of Botswana, and the court ruled that the island formed part of the territory of Botswana. This resulted in both countries increasing their security along the borders leading to insecurity amongst inhabitants living close to the borders. The outcome of the case culminated in political consequences as well as social and legal dilemmas that have impeded the cross-border management and security strategies between the countries. This necessitated the need for enhancing cross-border and regional connectivity, primarily through collaborations and setting up infrastructure (Maritz, Le Roux & Van Huyssteen, 2024). This was essential for promoting regional integration and enabling sustained economic growth for both countries (Maritz et al., 2024). Improved connectivity between neighbouring countries facilitates trade, increases accessibility, and consequently reduces disparities between countries within the region (Bonuedi, Kamasa & Opoku, 2020).

Materials and Methods

In this section, the study area, methods and sampling design, data analysis, and ethical considerations for the study are discussed.

Study Area

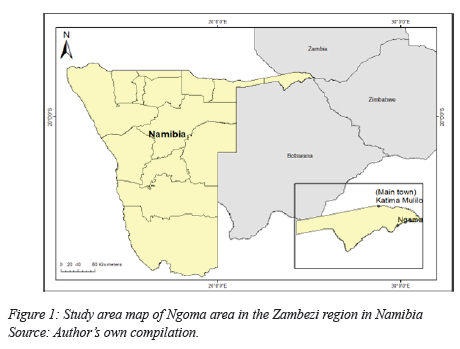

The current study was carried out in the rural area of Ngoma, which is located at the latitude of -17.8833 S and longitude of 24.7167 E in the far north-eastern part of Namibia, formally referred to as the Caprivi Strip. It is one of the border posts between Namibia and Botswana, where traffic crosses the border at Ngoma Bridge over the Chobe River (Figure 1).

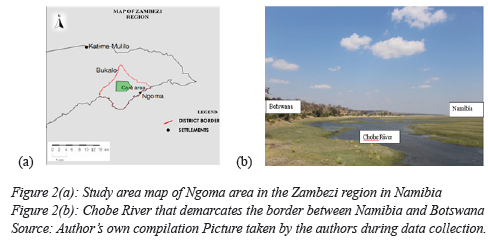

The region comprises a conservation area rich in wildlife, such as buffalo, lions, and elephants, and local communities benefit from both land and river resources (see Figure 2). The area attracts tourism that contributes significantly to the economy of the country and employment.

The area experiences human-wildlife interaction and conflict between residents and animals, as it is adjacent to the Chobe National Park in Botswana. Wild animals roam freely along the border area and between villages, threatening the lives of the locals.

Methods and Sampling Design

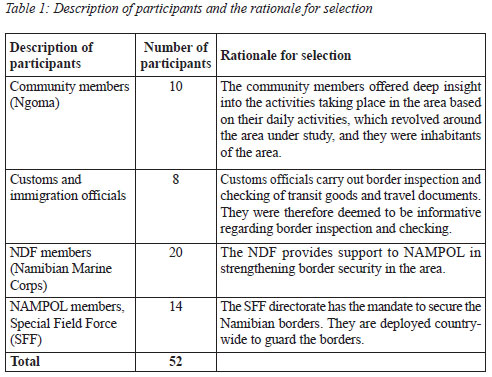

To explore the illicit border activities in the Ngoma area, a qualitative approach was used. The approach provided the opportunity for the elaboration of opinions that might not have been possible with other forms of data collection (Poth, 2023). The study employed desktop study, field observation, individual in-depth interviews, and focus group discussions (FGDs) with relevant stakeholders, comprising border officials, law enforcement agencies (NAMPOL [Namibian Police Force] and the NDF [Namibian Defence Force]), and community members. By combining these methods, the study gathered in-depth data, enabled data triangulation, and facilitated flexible engagement with participants to gather their insights, as recommended by (Poth, 2023). The researchers interviewed a total of 52 participants who were directly or indirectly involved in border security and law enforcement.

A purposive sampling technique was used to select participants based on their knowledge and understanding of the subject matter under investigation (Poth, 2023). Participants were selected either because they were representative of the sociocultural group where they had been living for at least five years, or because they were security or law enforcement officials assigned to border security and patrol. Moreover, the selection of participants was based on the roles that each group played in border security in the Ngoma area at the time, years of experience in border control, life experiences in the community, and duration of stay in the community. The NDF and NAMPOL (Namibia Police Force) participants were purposively selected based on their deployment in the area for border patrol and control. Particularly, the Marine Corps in the NDF formed part of the informants as they were expected to have the necessary experience and understanding of border security issues in the area where they had been deployed in the area for the past four years to guard the border area. In the same manner, community members who had been living in the area for at least five years were sampled. The researchers also interviewed customs and immigration officers who had been working at the border office for at least five years.

A total of 52 participants took part in the study of which 20 participants were from the Namibian Marine Corps in the NDF, 14 were from the Special Field Force in NAMPOL, 8 were from customs and immigration, and 10 were community members as shown in Table 1.

Of the 52 participants, 12 were interviewed (three community members, three Customs and Immigration officials, two NDF members, and four NAMPOL members). The interviews were face to face, and lasted between 30 minutes to an hour each. The remaining 40 participants took part in the FGDs (FGD) which lasted between 45 minutes to 1,5 hours. A total of five FGDs were conducted:

• One with members of NAMPOL (10 participants);

• Two with members of the NDF (nine participants each);

• One with officials from Customs and Immigration (five participants); and

• One with members of the community (seven participants).

Data Analysis

The data collected from the individual interviews and focus groups were analysed using thematic analysis. The method involved identifying, analysing, and reporting the identified themes, and interpreting them to deduce meaningful information (Clarke & Braun, 2017). Through the thematic content analysis procedure, the responses from the participants were collated, reviewed, and examined, and important phrases were highlighted by assigning codes in the ATLAS.ti software program. Through an inductive approach, these codes were sorted and categorised into groups and units of significance that were further coded into sub-categories. These sub-categories were reconstructed, re-classified, and grouped to develop themes and so to obtain meaning for the dataset. Consequently, significant themes related to illicit border activities in the Ngoma area emerged and were described accordingly. This process provided the basis for the researchers to use their knowledge and experience to identify patterns and similarities to bring meaning to the data.

Ethical Consideration

All procedures performed in this study followed the research ethical standards of the University of Namibia (UNAM). These standards align with the amended 1964 Helsinki Declaration (Kurihara et al., 1014). Before conducting the interviews and FGDs, ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee at UNAM. In the same manner, written informed consent was obtained from the participants before the interviews and FGDs, and for capturing of images and graphics. The study upheld the right to privacy throughout the study, and the participants were allowed to withdraw at any stage of data collection.

Results and Discussion

In this section, the findings from the data analyses were grouped and discussed in the following subsections: Nature and extent of illicit activities in the Ngoma Area, consequences of Illicit activities on Ngoma community and border control measures and their challenges.

Nature and Extent of Illicit Activities in the Ngoma Area

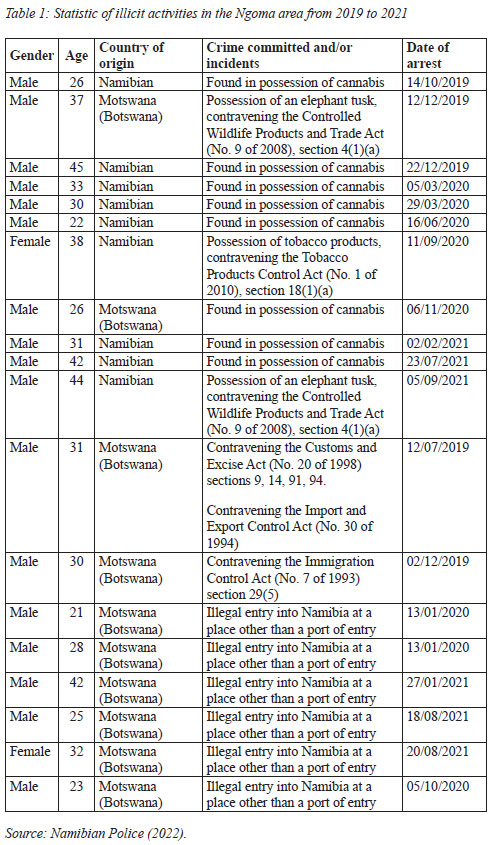

This section highlights the nature and extent of illicit activities occurring in a border are, namely the Ngoma area. It concludes by summarising ways of combating these activities. From the findings, the participants indicated that the prominent illicit activities occurring in the area at the time were carried out by Namibian and Batswana nationals. These illicit activities included poaching, illegal fishing, illegal border crossing, and smuggling of goods which was confirmed in a report by the Namibian Police (2022). These activities are driven by high levels of unemployment, poverty, access to affordable goods in neighbouring countries, inadequate border patrols, and a lack of police visibility in the area (Mabuku & Adewale, 2022). It is in this regard that community members see the need to have regulations in place to monitor and regulate such activities. Although these activities are frequently occurring in the area, participants indicated that only a few cases are documented and recorded because most of the activities go unnoticed. This observation is in line with the crime statistics report (see Table 2) received from NAMPOL indicating a few cases were recorded over three years (Namibian Police, 2022).

Moreover, Table 2 shows that there were 19 cases recorded over the three years involving both Batswana and Namibian offenders. Out of these 19 cases, about 89% of the crimes were committed by males in the age range of 30-39. The gender differences could be due to cultural beliefs that encourage women to stay home and care for their families while men go out to work and provide for their families. This argument is also supported by the gender-role theory, which argues, 'gendered differences in crime rates result from differences in gender roles, identities, and processes of socialisation' (Pleck, 2018:24).

The participants further indicated that many criminal activities go unnoticed because of a lack of patrol in the area due to insufficient vehicles, and limited manpower to patrol and make arrests if need be. This aligns with findings by Mabuku and Adewale (2022). Additionally, the results show that community members are at times not coming forth to report offenses occurring in their vicinities. A law enforcement participant stated, 'sometimes policing is a collaborative effort, but these locals sometimes are hiding most of the offenses committed in the area'. On the other hand, community participants claimed that, even if they report the offenders to the police, nothing much is being done; hence, they are discouraged from reporting. Participants confirmed this by stating, '[i] n most cases even if we report, the police do not show up. So why should we continue reporting the cases?'

The limited number of recorded cases along the border can also be attributed to the fact that the Botswana government is known to have strict measures in terms of law enforcement and border control measures (Nakale, 2024). An example is the ungazetted "shoot-to-kill" anti-poaching policy introduced to protect Botswana wildlife from poachers (Nakale, 2024). The policy has resulted in 30 Namibians and at least 22 Zimbabweans being killed in Botswana during anti-poaching operations (Tau, 2020). These killings may have instilled fear in the communities, and possibly resulted in a low number of cases recorded in the area. Over the years, the "shoot-to-kill" policy has caused diplomatic tensions between Namibia and Botswana (Tjitemisa, 2021).

Poaching

Participants indicated poaching as one of the prevalent illicit activities in the Ngoma area, as this area is located close to the Chobe National Park in Botswana. The area is home to a diverse range of wild animals, such as elephants, buffalo, giraffes, hippos, crocodiles, lions, leopards and many others. The Ngoma area falls under the Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (KAZA TFCA), a multinational conservation area that promotes the protection and free movement of wildlife and allows for the sharing of resources between countries (Kalvelage, 2021; Lines, Bormpoudakis, Xofis & Tzanopoulos, 2021). The conservation area stretches over the Kavango and Zambezi River basins, covering parts of Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe (Lines et al., 2021).

While the conservation area protects and promotes free wildlife movement, it may also result in a ^transit route" for wildlife, leading to increased human-wildlife conflict due to frequent encounters. This is because wildlife often grazes near riverbanks, villages, and agricultural fields making them a threat to human livelihoods. These interactions result in wildlife becoming easy targets for poachers. Poaching is also known to be prevalent in remote areas where monitoring is limited, and the chances of being caught are lower. As a result, poaching poses a significant threat to wildlife populations in the Ngoma area. This, in turn, affects tourism negatively and reduces revenue generation in the country.

While poaching is common in the area, the participants indicated that, due to a lack of transport vehicles, which hinders frequent patrols, only a few cases are recorded and arrests of offenders made (Namibian Police, 2022).

Smuggling of Goods and Illegal Crossing

The regular movement of goods and people is a common practice between bordering countries. This is no exception for the Ngoma border where goods and people are constantly in transit for different purposes. These movements become opportunities for the smuggling of illegal goods between Namibia and Botswana. With the growing demand for various types of goods for resale or personal use, individuals usually attempt to smuggle them in or out of the country either because they are attempting to avoid paying customs duties or because the items are illegal products. The participants indicated that the most common smuggled good is cannabis, intended for personal use and resale as recorded in Table 2. The increase in the use of cannabis could be because there is a high rise in its use within the African community, (USAID, 2013) resulting in higher demand. Such a demand promotes market opportunities for criminals to smuggle and sell the product for better returns on their investment. Participants indicated that offenders are caught during minimal border patrols and surprise inspections at the border office. The smuggling of illegal goods is a punishable offense in Namibia, as it contravenes customs regulations, taxation, and other legal requirements (Customs and Excise Act, No. 20 of 1998). The participants highlighted that the offenders mainly use undesignated border crossings and remote areas with limited surveillance of their illicit activities.

According to the reports released by the Namibian Police, it was observed that illegal entry into the country is a common activity, mainly carried out by individuals from Botswana. These individuals enter Namibia at locations other than designated ports of entry due to a lack of valid travel documents or involvement in illicit activities with a desire to avoid being caught. As indicated by the participants, the lack of equipment to scan and detect goods or people is a challenge and makes it difficult to control and monitor goods exiting and entering the country as well as the validity of entries.

Illegal Fishing

The Ngoma area has a unique geographical location that allows boat access to over 100 kilometres of prime water of the Chobe and Zambezi Rivers and the many productive waterways found in between (Bakane, 2016). The Chobe River is home to a multitude of fish species and inland fish resources that have supported the Ngoma and neighbouring communities for centuries. While these communities have lived off these resources for years, the introduction of fisheries resource management, which restricts fishing activities at times, has affected the common way of life in the communities. The restriction is implemented by the Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources (MFMR), which is responsible for monitoring, control, and surveillance (MCS) of both inland and maritime resources in Namibia. According to Kar and Chowdhury (2024), the MCS refers to plans, strategies, and policies geared towards the efficient management of inland and marine resources, particularly fisheries.

Moreover, the MFMR derives its mandate from the Marine Resources Act (No. 27 of 2000), which aims to provide adequate control over inland and marine resources through sustainable use and efficient conservation of resources. To achieve this, the MFMR has enacted several measures, including the restriction of the fishing season. The restriction of fishing is enforced to allow juvenile fish stocks to breed, although it affects those who depend on fishing as their only source of income. Since communities find it hard to sustain their livelihoods during this period, this restriction has forced them to engage in fishing even during the closed season leading to what is termed "illegal fishing". The illegal fishing referred to here, involves fishing outside of the permitted fishing period but also the type of fishing gear used. The participants indicated that locals engage in illegal fishing during the closed season by fishing at night using unauthorised fishing gear, such as mosquito nets and other illegal fishing gear. The participants further indicated that poverty and high rates of unemployment have contributed to these illegal activities as they serve as a means of food and income for local communities. As previously mentioned, the lack of equipment and manpower to carry out regular patrols and surveillance of the border area also seems to contribute to the frequent occurrence of illegal fishing in the area.

Overall, combating illicit activities in the area requires the involvement of several stakeholders comprising local authorities, community members, security clusters, and conservation organisations to collaborate and enhance border control efforts as well as to ensure the sustainable use of natural resources. Additionally, there is a need for community policing in monitoring and control of border areas to strengthen border security. Furthermore, engaging community members in security education programmes would empower stewardship toward their community and its resources. This will encourage sustainable use of resources and at the same time reduce the dependence on illicit activities for income. Moreover, with the assistance of its law enforcement agencies, government needs to invest and upgrade its infrastructure to increase patrols, surveillance, and technological innovations to deter illicit activities in the area. Technology, such as surveillance cameras, both stationery and mobile, could be one of the possible investments to be prioritised in the border area.

Lastly, collaboration with bordering counterparts is also crucial to address cross-border poaching, smuggling of goods, and illegal crossing. These strategies not only support conservation initiatives but also mitigate the consequences of illicit activities and preserve the rich natural heritage of the Ngoma area for generations to come.

Consequences of Illicit Activities on Ngoma Community

This section narrates the consequences of the identified illicit activities for the local economy and the community. The findings on the consequences experienced in the area include community instability and social disruption. This usually happens when members of the community are involved in illicit activities and are reported to authorities resulting in conflict, tension, and mistrust among them.

As previously discussed, smuggling of goods and illegal crossing are some of the common illicit activities that occur in the Ngoma area. These activities were found to threaten the local economy, and encourage unfair competition with smuggled goods. This results in loss of income and job opportunities for the local people. Moreover, the smuggled goods reduce government revenue from taxes and tariffs; thus, harming public services and infrastructure development, as pointed out by Edwards, Fadiran, Kamutando and Stern (2024). These activities also threaten the security of the communities, as illegal migrants are often involved in criminal activities that involve livestock theft and housebreaking (Kooper, 2024; Mubiana, 2023). This in turn encourages the local people to team up with the perpetrators, giving rise to an increase in violent activities and insecurity in the area. This can also lead to social fragmentation, mistrust, and a decline in social harmony within the communities. Moreover, participants indicated a lack of co-ordination between local law enforcement agencies as well as between Namibian citizens and people from the neighbouring countries (Botswana and Zambia). This is highlighted by Mubiana (2023) who refers to a lack of co-ordination among the security clusters, such as NAMPOL, the NDF, and immigration, and intelligence officials.

In the same manner, the participants indicated that inadequate border control facilitates the spread of illicit activities, which, in the long term, undermine border control legislation and weaken governance structures (Libanda, 2022). Participants also highlighted that it is a challenge to live along the border, as there seems to be constant conflict between Botswana law enforcement officials and the locals. This was confirmed by participants who stated, '[w]e are exposed to allegations by Botswana law enforcement officials that we are involved in poaching activities in their national park and that they will exercise their shoot-to-kill policy'. In this regard, Tlhage (2020) reports that Namibian citizens have been killed in anti-poaching operations, although the families of the deceased claimed that those killed were not poachers but rather innocent civilians or fishermen. This has inflicted fear among the communities whenever conducting their daily chores along the border.

Besides the challenges posed by the smuggling of goods and illegal crossing, illegal fishing is also a challenge in the area. Although fishing as a source of food and income in the area has been part of the lives these communities for years, illegal fishing seems to have a negative effect on the local economy, food security, and the environment. While some community members observe the off-fishing season, some ignore it and continue fishing illegally. This has resulted in the reduction of some fish species, threatening the livelihood of these communities. Additionally, the use of illegal fishing gear culminates in the disruption of marine habitats and ecosystems, resulting in a reduction of fish stocks in the area. To address the illicit activities in the area effectively, engaging local communities by way of training programmes on community policing, and border security regulations are necessary (Johnson, 2019).

Border Control Measures and Their Challenges

Under this section, border control strategies employed in Namibia and their challenges are discussed. Security screening of persons and travel documents is carried out when entering or leaving the country to ensure compliance with customs regulations. At the border post, inspection is conducted by customs officials, whereas patrol is carried out by NAMPOL and NDF personnel on foot and by way of vehicle patrols. The visibility of these security sectors along the border and surrounding area acts as a deterrent to illicit activities.

Their effectiveness of these control measures is hindered by several challenges. From a law enforcement perspective, a lack of vehicles, overhead aerial surveillance, as well as manpower, hinders regular border patrols. Additionally, the vastness of the area that needs monitoring and control still poses a significant challenge, as there are still inaccessible remote areas that require overhead aerial surveillance, which seems to be non-existent in the area. This presents an opportunity for offenders to engage in illicit activities. Moreover, the security agencies that conduct border patrols indicated that they are hampered by a lack of both land and water transport to carry out their duties. In this case, boats are required for river patrols while vehicles are used for land patrols.

Apart from limited border patrols, carrying out regular inspections is also a challenge. Participants cited that the lack of equipment such as X-ray scanners, and detectors for border inspection and verification remains a challenge. In the absence of equipment or where equipment malfunction, Customs officials resort to physical searching, checking, and manual recording, which present opportunities for errors, conflicts, and disagreements as well as bribery, as argued by Claasen (2022). To improve border control, investments in infrastructure and equipment are required to ease mobility during border patrols and to ensure adherence to border regulations.

Participants' perceptions of the effectiveness of law enforcement showed that even though the Namibian law enforcement agencies were trying their best at the time to maintain law and order along the borders, there was a lack of collaboration with their neighbouring counterparts, which may have contributed to the killing of four Namibians because of the "shoot-to-kill" policy administered by the Botswana government (The Namibian, 2019). Participants consequently recommended the need for improved co-operation with security forces of neighbouring countries to address transboundary illicit activities effectively. They also emphasised the need for engagement with local communities to improve intelligence sharing, as residents often have first-hand knowledge of suspicious activities or illegal crossings.

Lastly, there is a need for capacity training programmes for law enforcement officers on border security and management and relevant legislation. Moreover, customs officials may require training in modern technology applications, border legislation, anti-smuggling investigations, and customs and border management. Such training is vital for skill development and competencies in border control and management.

The current findings revealed that, although law enforcement personnel encounter challenges when carrying out border control activities, they still manage to accomplish a degree of control under the given circumstances. The main measures for border control in the Ngoma area are inspection at the border post and patrols of the border and its surroundings.

Conclusion and Recommendations

This study examined illicit activities in the Ngoma area in Namibia, focusing on the border control measures in place and the challenges faced. The key illicit activities identified were poaching, smuggling, illegal border crossings, and illegal fishing. The study on which this article reported highlighted how these activities threaten national security, hinder border control efforts, and disrupt community livelihoods and the local economy. Despite existing border control efforts, there are still challenges that hinder their effectiveness. The challenges identified include a lack of manpower, infrastructure, patrol means, collaboration among stakeholders, and equipment for border inspection and checking. Addressing these issues requires increasing manpower for enhanced law enforcement and patrols, investing in infrastructure, such as scanning equipment and surveillance technology, and fostering collaboration with security sector stakeholders.

In addition, engagement with local communities and regional co-operation, including shared intelligence, joint patrols, and training programmes, could improve border intelligence and co-ordination. Upgrading border control measures is essential to strengthen national security and maintain territorial integrity. This involves introducing advanced surveillance technologies, such as biometric scanners, and drones, as well as improving license plate recognition for greater security and efficiency in Ngoma. Training and capacity building for law enforcement and border officials are crucial for enhancing their skills in combating illicit activities. Moreover, sensitising community members to the effects of illicit activities through community policing could foster strong relationships with law enforcement. Furthermore, collaboration with agencies in neighbouring countries would also play a vital role in addressing cross-border threats and enhancing security.

Acknowledgments

We hereby acknowledge the following people who assisted in the study: the Zambezi regional governor, migration officers at the Ngoma border post, the Namibian police, community members of the Ngoma area, and the NDF.

REFERENCES

Bakane, M. 2016. The role of protected areas in the conservation and management of fisheries in the Chobe District of Botswana. Doctoral dissertation, Rhodes University. [ Links ]

Blundell, B.G. 2020. Surveillance: Technologies, techniques and ramifications. In B.G. Blundel (ed.). Ethics in computing, science, and engineering. Cham: Springer, 211-292. [ Links ]

Bonuedi, I., Kamasa, K. & Opoku, E.E.O. 2020. Enabling trade across borders and food security in Africa. Food Security, 12(5):1121-1140. [ Links ]

Byrne, S., Nightingale, A.J. & Korf, B. 2017. Making territory: War, post-war and the entangled scales of contested forest governance in mid-western Nepal. In C. Lund & M. Eilenberg (eds.). Rule and rupture. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell, 71-94. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119384816.ch4 [ Links ]

Carter, D.B. & Poast, P. 2017. Why do states build walls? Political economy, security, and border stability. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 61(2):239-270. [ Links ]

Chikanda, A. & Tawodzera, G. 2017. Informal entrepreneurship and cross-border trade between Zimbabwe and South Africa. Southern African Migration Programme. https://doi.org/10.2307/i.ctvh8qz72 [ Links ]

Claasen, W.H. 2022. An analysis of determinants of effective tax administration: Inland revenue department, Namibia. Doctoral dissertation, University of Namibia. [ Links ]

Clarke, V. & Braun, V. 2017. Thematic analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(3):297-298. [ Links ]

Edwards, L., Fadiran, D., Kamutando, G. & Stern, M. 2024. Quantifying tariff revenue losses from the African Continental Free Trade Area. Journal of African Trade, 11(1):1-22. [ Links ]

Fakhrzad, N., Yazdi-Feyzabadi, V. & Fakhrzad, M. 2024. Drivers of vulnerability to medicine smuggling and combat strategies: A qualitative study based on online news media analysis in Iran. BMC Health Services Research, 24(1):1-18. [ Links ]

Fischer, C., Achermann, C. & Dahinden, J. 2020. Revisiting borders and boundaries: Exploring migrant inclusion and exclusion from intersectional perspectives. Migration Letters, 17(4):477- 485. [ Links ]

Harff, B. & Gurr, T.R. 2018. Ethnic conflict in world politics. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429495250 [ Links ]

Hobbing, P. 2016. Integrated border management at the EU level. In T. Balzacq & S. Carrera (eds.). Security versus freedom? London: Routledge, 155-182. [ Links ]

Jacobs, S. 2014. Borders, border management, and regional integration in southern Africa: The case of Namibia. African Security Review, 23(4):425-439. [ Links ]

Johnson, W.H. 2019. Community engagement in policing: A leadership white paper. Karnes, TX: Karnes City Police Department. [ Links ]

Kacowicz, A.M., Lacovsky, E. & Wajner, D.F. 2020. Peaceful borders and illicit transnational flows in the Americas. Latin American Research Review, 55(4):727-741. [ Links ]

Kalvelage, L. 2021. Capturing value from wildlife tourism: Growth corridor policy and global production networks in Zambezi, Namibia. Doctoral dissertation, Universitat zu Köln. [ Links ]

Kamidza, R. 2017. Assessment of the role of SADC in the Zimbabwe crisis, 2000-2013. Doctoral dissertation, North-West University. [ Links ]

Kar, P. & Chowdhury, S. 2024. IoT and drone-based field monitoring and surveillance system. In S.S. Chouhan, A. Saxena, U.P. Singh & S. Jain (eds.). Artificial intelligence techniques in smart agriculture. Singapore: Springer, 253-266. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-97-5878-415 [ Links ]

Klopp, J.M., Trimble, M. & Wiseman, E. 2022. Corruption, gender, and small-scale cross-border trade in East Africa: A review. Development Policy Review, 40(5): art. 12610. [ Links ]

Kooper, L. 2024. Namibian, Zambian police work together to fight crime. The Namibian, 13 April. Retrieved from https://www.namibian.com.na/namibian-zambian-police-work-together-to-fight-crime/ [Accessed 19 November 2024]. [ Links ]

Kuria, M.Z. 2022. Resources and performance in border security: A study of border police unit in the national police service, Kenya. Doctoral dissertation, Kenyatta University. [ Links ]

Kurihara, C., Kerpel-Fronius, S., Becker, S., Chan, A., Nagaty, Y., Naseem, S., Schenk, J., Matsuyama, K. & Baroutsou, V. 2024. Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical norm in pursuit of common global goals. Frontiers in Medicine, 11: art. 1360653. [ Links ]

Kuteyi, D. & Winkler, H. 2022. Logistics challenges in sub-Saharan Africa and opportunities for digitalization. Sustainability, 14(4): art. 2399. [ Links ]

Le Roux, C.J.B. 1999. The Botswana-Namibian boundary dispute in the Caprivi: To what extent does Botswana's Arms Procurement Program represent a drift towards Military Confrontation in the Region? Scientia Militaría, 29:53-70. [ Links ]

Leutloff-Grandits, C. & Wille, C. 2024. Dynamics of dis/order in border complexities. In C. Wille, C. Leutloff-Grandits, F. Bretschneider, S. Grimm-Hamen & H. Wagner (eds.). Border complexities and logics of dis/order. Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, 7-30. [ Links ]

Libanda, E. 2022. Zambezi hit by Zambian stock thieves. Namibia Daily News, 11 November. Retrieved from https://namibiadailynews.info/zambezi-hit-by-zambian-stock-thieves/ [19 November 2024]. [ Links ]

Lines, R., Bormpoudakis, D., Xofis, P. & Tzanopoulos, J. 2021. Modelling multi-species connectivity at the Kafue-Zambezi interface: Implications for transboundary carnivore conservation. Sustainability, 13(22): art. 12886. [ Links ]

Mabuku, K. & Adewale, O. 2022. Preservation of internal security in Namibia: An impossible mandate for the Namibian Police Force. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science, 11(10):386-397. https://doi.org/10.20525/ijrbs.v11i10.2153 [ Links ]

Maritz, J., Le Roux, A. & Van Huyssteen, E. 2024. SADC's settlement hierarchy and networks in support of cross-border regional development. In J.E. Drewes & M. van Aswegen (eds.). Regional policy in the Southern African Development Community. London: Routledge, 99-122. [ Links ]

Minnaar, A. 2022. Border security: An essential but effective tool in combatting cross-border crime. In M. Gill (ed.). The handbook of security. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 357378. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-91735-7_17 [ Links ]

Motseki, M.M. & Mofokeng, J.T. 2022. An analysis of the causes and contributing factors to human trafficking: A South African perspective. Cogent Social Sciences, 8(1): art. 2047259. [ Links ]

Mubiana, S. 2023. Criminal activities concern residents of the Zambezi Region. NBC News, 29 October. Retrieved from https://nbcnews.na/node/98536 [Accessed 19 November 2024]. [ Links ]

Nakale, A. 2024. Nam, Botswana to quell cross-border fears. New Era, 30 May. Retrieved from https://neweralive.na/nam-botswana-to-quell-cross-border-fears [Accessed 19 November 2024]. [ Links ]

Namibian Police. 2022. Report on crime statistics in Zambezi Region. Namibia Police annual reports. Unpublished. [ Links ]

Ndumba, S., Shikangalah, R. & Becker, F. 2021. Towards understanding the role of informal cross-border trading at Rundu-Calai bridgehead, Namibia. Journal of Namibian Studies: History Politics Culture, 29:7-25. [ Links ]

NSA (Namibia Statistics Agency). 2020. Namibia Population and Housing Census: Analytical report. Retrieved from https://nsa.org.na/2023-housing-and-population-census/ [Accessed 19 November 2024]. [ Links ]

Ombara, I. 2021. Cross border natural resource management and sustainable peace in Eastern Africa region: A case study of Kenya. Doctoral dissertation, University of Nairobi. [ Links ]

Omoniyi, K.S. 2023. Evaluation of transborder crimes in Nigeria. American Journal of Society and Law, 2(1):13-20. [ Links ]

Ortiz, T.R. 2021. Bribery and corruption at the border: Mexico: An outstanding challenge to be overcome by the Mexican government. Global Trade and Customs Journal, 16(9):429-436. [ Links ]

Pleck, J.H. 2018. The theory of male sex-role identity: Its rise and fall, 1936 to the present. In H. Brod (ed.). The making of masculinities. New York, NY: Routledge, 21-38. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315738505-3 [ Links ]

Poth, C.N. 2023. The Sage handbook of mixed methods research design. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Republic of Namibia. 1998. Customs and Excise Act 20 of 1998. Windhoek. [ Links ]

Rohilie, H.F. 2020. State security and human security in border management. Academia Praja: Jurnal Ilmu Politik, Pemerintahan, dan Administrasi Publik, 3(1):23-36. [ Links ]

Sciortino, G., Cvajner, M. & Kivisto, P.J. (Eds.). 2024. Research handbook on the sociology of migration. New York, NY: Edward Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781839105463. [ Links ]

Simmons, B.A. & Kenwick, M.R. 2022. Border orientation in a globalizing world. American Journal of Political Science, 66(4):853-870. [ Links ]

Tau, P. 2020. Namibia citizens up in arms over Botswana's 'shoot to kill' approach. City Press News, 12 November. Retrieved from https://www.news24.com/citypress/news/namibia-citizens-up-in-arms-over-botswanas-shoot-to-kill-approach-20201112 [Accessed 19 November 2024]. [ Links ]

The Namibian. 2019. BDF killings: No guns found on Namibian fishermen, 19 November. Retrieved from https://www.namibian.com.na/bdf-killings-no-guns-found-on-namibian-fishermen/ [Accessed 19 November 2024]. [ Links ]

Thomas, K.A. 2015. The river-border complex: Governing flows in South Asia. Doctoral dissertation, Rutgers University. [ Links ]

Thomson, A. 2022. An introduction to African politics. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Tjitemisa, K. 2021. Two 'Namibians' killed in Botswana over poaching. New Era, 29 August. Retrieved from https://neweralive.na/two-namibians-killed-in-botswana-over-poaching/ [Accessed 19 November 2024]. [ Links ]

Tlhage, O. 2020. Namibia and Botswana in talks over Zambezi shooting. Namibian Sun, 1 December. Retrieved from https://www.namibiansun.com/news/namibia-and-botswana-in-talks-over-zambezi-shooting2020-11-09/ [Accessed 19 November 2024]. [ Links ]

Udosen, N.M. & Uwak, U. 2021. Armed banditry and border monitoring: Challenges for Nigeria's security, peace and sustainable development. European Journal of Political Science Studies, 5(1):45-72. [ Links ]

USAID. 2013. The development response to drug trafficking in Africa: A programming guide. Washington, DC. [ Links ]

Vilks, A. & Kipane, A. 2018. Economic crime as a category of criminal research. Journal of Advanced Research in Law and Economics, 9(8):2861-2868. [ Links ]

Vitvitskyi, S., Syzonenko, A. & Titochka, T. 2022. Definition of criminal and illegal activities in the economic sphere. Baltic Journal of Economic Studies, 8(4):34-39. [ Links ]

Wagner, J. 2021. The European Union's model of integrated border management: Preventing transnational threats, cross-border crime and irregular migration in the context of the EU's security policies and strategies. Commonwealth & Comparative Politics, 59(4):424-448. https://doi.org/10.1080/14662043.2021.1999650 [ Links ]

Wimmer, A. 2013. Ethnic boundary making: Institutions, power, networks. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Zeller, W. 2009. Danger and opportunity in Katima Mulilo: A Namibian border boomtown at transnational crossroads. Journal of Southern African Studies, 35(1):133-154. [ Links ]

Zou, F., Bhuiyan, M.A., Crovella, T. & Paiano, A. 2024. Analyzing the borderlands: A regional report on the Colombia-Ecuador border on political, economic, social, legal, and environment aspects. International Migration Review, 58(2):881-897. [ Links ]

1 Charlene Bwiza Simataa is a lecturer at the School of Military Science, University of Namibia, specializing in GIS, remote sensing, and geography. She served as Head of Department from 2019 to 2021. Currently pursuing a PhD in Geography, her research focuses on developing a framework to monitor fisheries activities in Namibia's Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), aiming to enhance marine resource management. In 2022, she participated in a training program on polymetallic nodule exploration by the International Seabed Authority (ISA) and Deep Ocean Resources Development (DORD), furthering her expertise in marine resources.

2 Dr Loide Shaamhula is a Senior lecturer and researcher at the University of Namibia at the School of Military Science where she is responsible for the courses on Military Geography and Physical Geography. She supervises and mentors' postgraduate students who have taken up research projects on Physical Geography, human geography, disaster studies and environmental management issues. She has a PhD in Military Science from Stellenbosch University in South Africa. Dr Shaamhula is an early career, and her research interests focuses on military studies, disaster risk and the formulation of socially, environmentally, and economically viable and acceptable disaster response strategies and management.