Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of Contemporary Management

On-line version ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.22 n.1 Meyerton 2025

https://doi.org/10.35683/jcman1124.282

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Achieving sustainable development by leveraging innovation outcomes with design thinking

Kavisha NandhlalI, *; Cecile Gerwel ProchesII; Shamim BodhanyaIII

IGraduate School of Business and Leadership, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Email: kavisha@.theinnovationspace.co.za; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2250-2154

IIGraduate School of Business and Leadership, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Email: gerwel@.ukzn.ac.za; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2330-9575

IIIGraduate School of Business and Leadership, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Email: shamim@leadershipdialogue.co.za; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0000-6645-883X

ABSTRACT

PURPOSE OF THE STUDY: Sustainable development has garnered insufficient action around the world. A barrier to this has been pathways to achieve sustainable development. Innovation is a means by which sustainable development can be addressed. Design thinking has the potential to conceptualise innovations by understanding problems with greater depth where the complexity of matters is factored into the problem and multiple solutions are developed. The purpose of this study was to position design thinking as an alternative mechanism to traditional economics of research, strategy and policy in order to improve economic development outcomes and contribute to sustainable development

RESEARCH QUESTION: The research question focused on innovation as a driver of addressing SDG 8 for decent work and economic growth

METHODOLOGY: This study was conducted at a Municipality. Action research was used as a research strategy and qualitative research was used as a research approach for the data collection and the analysis of findings

FINDINGS: Key findings related to the municipality's problem-solving capacity and ways in which to improve their ability to create an enabling environment

CONTRIBUTION OF THE STUDY: The main contribution of this study was a new approach to improving economic development outcomes by addressing the SDGs with design thinking

JEL CLASSIFICATION: M10, M19

Keywords: Design thinking; Economic development; Innovation; Public sector; Sustainable development; SDGs; 2030 Agenda; SDG 8; United Nations.

1. INTRODUCTION

The public sector in South Africa is guided by a strategic planning framework referred to as the Integrated Development Plan (IDP); that utilises strategic planning to guide economic development outcomes. This has the intention to contribute to improving the quality of life for people in local governments. This overarching theme extends towards sustainable development, which encompasses the overall well-being of society. However, the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) has been rather slow globally. There are still many unanswered questions regarding its development and practice. The compounding of various complex issues in South Africa, such as unemployment, inequality and poverty, has shown that government officials require alternate mechanisms to provide evidence and develop interventions that can contribute towards the progress of the SDGs. Innovation has a multi-disciplinary solutions approach and has been recognised as one of the key drivers of feasible changes (Clune & Zehnder, 2018). However, the public sector has not yet embraced innovation as a meaningful intervention to bring about change for sustainable development. Although innovation does feature as an important contributor to economic development, this is most commonly perceived to be used for social innovation and optimising processes.

The applicability of innovation to sustainable development has not yet been adequately articulated. Much of the discourse on innovation focuses on technological advancements such as renewable energy technologies, smart grids, and green infrastructure. However, sustainable development also requires systemic innovation, which involves changes in policies, business models, and societal norms. The interaction between technological and systemic innovation in driving sustainable development is underexplored, and their combined impact is not well articulated. While innovation is recognised as vital to sustainable development, more work is needed to define its role in specific contexts, clarify pathways for integration, ensure equitable access, and develop robust metrics to measure its impact.

Design thinking is human centered and provides insights into the lived experiences of people, which allows for solutions to be transformed into innovations that better the lives of people.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

Local government officials are generally responsible for shaping the development of societies. Local economic development emerged in the 1980s with policies, strategic planning processes, investment programmes and development programmes (Pavel & Moldovan, 2019). Globally, local economic development has focused on the development of policy frameworks that are representative of the social and economic trends that impact local economies. This is inclusive of trade and commerce, globalisation and employment dynamics. Growth and development have traditionally been viewed and analysed as the accumulation of physical capital (Clune & Srholec, 2017).

Conventional theory on economic development views functions of markets in isolation from the greater socio-economic system where demand and supply functions are inter - related for market equilibrium (Morgan, 2015). Socio-economic challenges in South Africa dominate and largely influence the economy. Complex problems, such as poverty, social transformation and unemployment, pose the greatest impediments to economic growth. Consistently low growth rates in South Africa have been insufficient to counteract the effects of changing societies. Policies and practices set out by governments have not quite adapted to the speed at which societies and economies are changing (OPSI, 2019). Although proposed policies are well meant, the implementation thereof is often hampered by capacity issues.

Resorting to best practice leads to a dominance of single-case inductive approaches to LED strategies, where systematic monitoring is notably lacking. Traditional economics are no longer adequately serving the needs of a rapidly changing society. Post-apartheid South Africa has continued to face high levels of inequality, where service delivery has not reached optimal levels. Challenges of service delivery have often sparked widespread public protests in South Africa. This, it can be argued, can be due to dissatisfaction with adequate basic services. Despite the prioritisation of regulatory processes on a nation level, several countries are not able to meet the real needs of society with the implemented resources. New ways of working need to be sought after since problems within South Africa have been compounding over the years.

Development is defined as a multi-dimensional concept that is evolutionary and incorporates social structures, economic growth, the eradication of poverty, and the reduction of inequality (Mensah, 2019). Sustainability means 'maintained over time', with many academics citing sustainable development as a healthy social, economic and ecological system for human development (Tjarve & Zemite, 2016). At the 1992 UN conference on Agenda 21, the three pillars of global sustainability were presented as social well-being, economic growth and environmental stewardship (Opon & Henry, 2019). Whilst this concept presented an attractive construction, its meaning lacked sufficient semantic clarity for it to be coherently operationalised. The United Nations (UN) outlined the SDGs with a sense of urgency for governments and stakeholders to deliver on the 2030 Agenda of providing dignity and prosperity for people in order for the right choices to be made that would result in sustainable improvements (Breuer et al., 2019). This has introduced a multi-faceted approach that preserves human rights and humanity (Firoiu et al., 2019).

The UN presented a novel approach to the SDGs, where goal-setting was highlighted as a key strategy. While the UN's introduction of the SDGs marked a significant step toward operationalising sustainable development through goal-setting, the challenge remains in ensuring that these goals are effectively implemented and integrated across diverse contexts. Achieving true sustainability requires more than a theoretical framework. It demands coordinated action across social, economic, and environmental dimensions, with a focus on human rights, equity, and long-term resilience. Only through this multi-faceted and coherent approach can sustainable development be fully realised, ensuring both present and future prosperity.

Attempts have been made to assess the success of the SDGs through data gathering, monitoring and evaluation (Moyer & Hedden, 2020), whilst researchers have used a scoring system over a period of time that focuses on specific groups. Following the call at the 49th World Economic Forum in January 2019, global initiatives are required to address the world's most pressing problems, as the global COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated systemic changes that are now more apparent. The UN highlighted that governments should shift towards sustainable economies by partnering with the private sector and civil society to create an upward convergence of opportunities and standards of living (Messerli et al., 2019). Although this is a promising endeavour, a collective evaluation of the goals relative to national organisational goals is lacking. A shift of priorities of all parties is necessary to forge a common path and create conscious awareness of what is needed.

Prior to the practical application of the SDGs, it is imperative to determine the basis for actions that will support decision making. Prioritisations of current policies are not necessarily the only pathway to achieving the SDGs (Moyer & Hedden, 2020). Adhering to current ways of doing things does not necessarily bring about change. There is a need to create suitable ways in which to address problems. With only eight years remaining to achieve the ambitious 2030 agenda, more interest needs to be garnered from the public sector, civil society and the private sector. New ways of doing things are needed. Sustainable development policy has highlighted the innovation economy as an important constituent in generating added value (Szopik-Depczyńska et al., 2018).

Innovation has the ability to transform ways of life and contribute to sustainable development, as it has the potential to drive the creation of new solutions that can address environmental, social, and economic challenges more effectively. However, the shift towards innovation centered approaches has been slow. Harnessing human creativity at a localised level is a means with which to implement sustainable development in areas such as modern technologies and innovations (Raszkowski & Bartniczak, 2018), that will effectively deliver solutions for addressing the SDGs.

Innovation is understood to be a key factor in employment growth and economic growth, which impacts improving the living standards of people (Loppolo et al., 2016). It has always been considered to be imperative in improving economic growth. Innovation, whether in the form of new technologies, business models, processes, or products, leads to increased productivity and efficiency within industries. This allows businesses to expand, generate higher output, and contribute to overall economic growth. By making industries more competitive, innovation helps create wealth and new opportunities in the economy. As industries adopt innovative practices and technologies, they often expand or create new sectors and markets, leading to increased demand for labour. This demand can result in job creation, especially in high-skill, knowledge-based sectors. Moreover, innovation can lead to the development of entirely new industries, opening up more employment opportunities. Economic growth driven by innovation typically results in higher incomes and better employment prospects for individuals. As businesses grow and wages rise, people have more disposable income, which can enhance their quality of life. Additionally, innovations in areas like healthcare, education, and infrastructure contribute to better living conditions, social well-being, and access to essential services.

Sustainable indicators simplify information, making it more communicable, especially for nonexperts. Indicators are often void of theory (Fagerberg & Srholec, 2017) and may highlight trends at a national and global level but do not give enough attention to risks and background factors, potentially creating a non-optimal path. Existing research on education on sustainable development has predominately focused on learning outcomes and has lacked techniques that would enable individuals to shift towards sustainability (Lambrechts & Van Petegem, 2016). A development strategy that is innovation driven supports national strength and improvements in society's productive strength (Chen et al., 2017). It has been widely acknowledged that innovation has the ability to transform ways of life and the external environment, although the shift towards innovation-centred approaches has been slow. Achieving the SDGs requires a social movement inclined towards a bottom-up action that is specifically country-driven (Hajer et al., 2015), that utilises important knowledge and skills for developing complex and integrated solutions. This is alternative to the entirely top - down policy action.

Approaching the SDGs with innovation is most often viewed from a technological perspective. The notion of innovation as technology is shifting towards creating new value and meaning (Hautamäki & Oksanen, 2016). The understanding of innovation impacts the course of action taken as an innovation may present itself as any new value, such as improvements or a new product, service, programme, project, etc. An important consideration is that innovation should be thought of as the entire process of innovating, as well as the outcome (Kahn, 2018). A major focus on outcomes will lead to inefficiencies that minimise the process, duplications of efforts, and the overconsumption of resources. A broader vision for innovation should be anticipated. The innovation process can begin with an innovation concept, grounded in design thinking, that focuses on understanding user needs and challenges, serving as the foundation and justification for the innovation. This is followed by the development of the innovation and, thereafter, implementation or adoption that is dependent on the nature of the innovation (Oeij et al., 2019).

The SDGs require social movements with higher states of consciousness. Dealing with changes cannot depend solely on logic and linear processing; there has to be a simultaneous engagement of mental capabilities and holistic perspectives. Innovation that views the world as it is needed in order to open pathways to new ways of thinking. This prioritises understanding the ways of the world and seeking improvements for betterment. An approach to the implementation of sustainable development is by facilitating the lessening of problems and enhancing the ability to exploit opportunities. The use of design thinking for innovation has the potential to leverage transformation and build a more sustainable future by delivering more impactful innovation solutions that result in effective changes for people. The actions of design thinking aim to transform existing situations into desired situations. Design thinking is an approach to innovation that enables individuals to act as change agents by understanding citizens from their perspective, bringing forth what matters to them and what they are experiencing. This is the first step in creating abundant and meaningful solutions that are later translated into innovations.

Design thinking reflects on why the end-user is experiencing a problem, what can be done to address this, and how this solution can be realised (Thomas & McDonagh, 2013). This is enacted through empathetically engaging with end users during the design research, defining the problem, generating ideas, prototyping and testing the solution, as depicted in Figure 1. Design research is one of the main techniques used for end-user research in order to identify obstacles the end-users experience in their environment (Wolniak, 2017). The define phase has a core focus on synthesising and interpreting information that is turned into insights (Liebenberg, 2020). The purpose of the ideation phase is to generate as many creative ideas as possible by reflecting on insights from the problem space (Wolniak, 2017). A prototype is a physical representation of the solution and serves as a visual for fast feedback on its effectiveness (Wolniak, 2017) and for transforming it (Beckman, 2020). Testing involves reconstructing meanings derived from previous situations in order to inform improvements for future design activities (Stompff et al., 2016).

In the context of governments, innovation is often viewed from a perspective of social innovation, where other uses for innovation are seldom sought after. As the focus shifts to the initial conceptual stage of discovering and developing solutions, there will be a deeper level of understanding where understanding and addressing problems are reframed as opportunities for innovations that emerge in different contexts. Design thinking has the potential to systematically discover new opportunities for innovation, especially in ways that cannot ordinarily be ascertained. This process goes beyond traditional methods, often uncovering hidden insights or unmet needs that wouldn't be identified through conventional analysis alone. By encouraging creativity, collaboration, and constant feedback, design thinking helps explore new, often unexpected, avenues for innovation that may not be immediately obvious, enabling solutions that are more effective, relevant, and impactful. This is mainly through the discovery of the problem in the initial stages of design research, as defined in Figure 1.

Design research is different to other types of research in that it provides a rigorous understanding of a person and their life experiences. Design research is one of the main techniques used for end-user research in order to identify obstacles the end-users experience in their environment (Wolniak, 2017), where the end goal is prioritised as a starting point and is used to work back to understanding elements of the problem, through evidence and generating inferences (Amidu et al., 2019). Incorporated into this are also cause-and-effect relationships that are associated with observations of successive events (da Silva, 2019). This is an alternative to qualitative research that requires direct contact and focuses on understanding viewpoints from the perspective of the individuals. Design research is what sets design thinking apart as a more in-depth approach to understanding problems that people are experiencing, especially on an emotional level, in order for more solutions that could directly address problems that people are experiencing to be developed.

3. RESEARCH QUESTION

How can government entities address SDG 8 for decent work and economic growth with innovation as a driver of sustainable development in order to deliver improved value for citizens and contribute to economic transformation?

4. METHODOLOGY

The research philosophy encompasses the nature of social reality, ways of knowing and value systems. In design thinking, the researcher seeks to understand how people adapt processes and behaviours that are linked to theory and practice as an approach to problem-solving in order to harness innovative power (Callahan, 2019). This emphasises the participants' thought processes and harnesses the epistemological dimension of constructing new knowledge. The research philosophy that informed this methodology was constructivism. The constructivist perspective is typically viewed as an approach to qualitative research where individuals develop an understanding of their world through the subjective meanings of their experiences (Creswell & Creswell, 2017). The research approach selected for this study was thus qualitative research.

This study was conducted at a Municipality in South Africa. Purposive sampling was used to identify participants for this study. This considers people who have similar expertise and experience in the required information (Etikan & Bala, 2017). The inclusion criteria included individuals with more than five years of experience in contributing to decision-making and policy-making, which would satisfy purposive sampling. Senior government officials who met the inclusion criteria were interviewed. The research design selected for this study was based on the research problem of the municipality not having an articulated approach to innovation.

Qualitative research is not restricted to producing insights or knowledge; it can also be used to develop new knowledge that is practically relevant. Hence, action research was chosen as the most appropriate research strategy that aimed at understanding the organisational innovation capability (Price et al., 2018), from the data collection to the analysis of results.

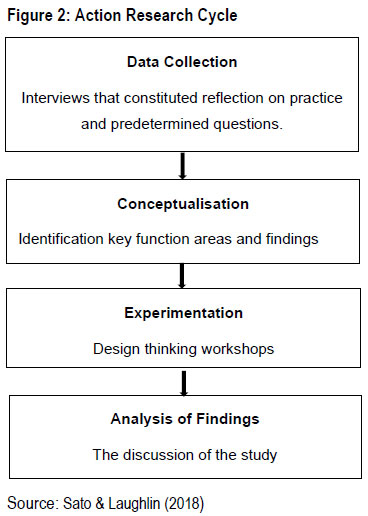

Action research is not, particularly, a method but rather an orientation towards inquiry. Action research most often begins with a question that highlights the purpose of the study. In the context of this study, the researcher conducted the action research inquiry by questioning how innovation outcomes could be improved in the organisation. Kolb's experiential learning cycle incorporates a stepwise process of experience and reflective observation that was incorporated into the data collection, conceptualisation, experimentation and concluded with an analysis of results (Sato & Laughlin, 2018), as shown in Figure 1. This process ultimately created new knowledge for the application of design thinking as the participants' experiences and challenges were gathered during the data collection and incorporated into the design thinking workshop.

4.1 Data collection

Qualitative research provides detailed descriptions and interpretations through its data and analysis that make theoretical explanations feasible (Eisenhardt et al., 2016). Framing the qualitative study plays a significant role in guiding the alignment of the methods used with the objectives of the study. Phenomenology, a type of qualitative research, assesses reflections on ordinary experiences that are lived through people's daily existence and investigates the meanings that correlate with lived experience (Van Manen, 2016). Understanding the participants' work experiences by conducting individual interviews assisted in identifying where changes could be made.

The data collection included contact time between individual participants and the researcher. This was done in two consecutive phases: reflection and observation. Interviews were conducted in person and via Zoom. The interview began with the participants reflecting on everything that was done to achieve the sustainable development goals, such as processes, frameworks, behaviours and attitudes. This was followed by the participants being asked ten pre-determined, semi-structured interview questions that were answered in the context of the reflection. See Annexure A for the semi-structured interview guide.

4.2 Conceptualisation

The conceptualisation stage contributed to formulating the experimentation phase by incorporating the understanding of the meaning of experiences coupled with the subject matter (Kolb & Kolb, 2018). The purpose of this study was to determine how design thinking could be utilised to improve innovation outcomes in the context of sustainable development. For this, the researcher engaged with raw data from the data collection phase in order to extract key functions carried out by the participants, and thereby determine the findings of the study. This formed the basis of the experimentation phase, where the researcher demonstrated how design thinking can be applied to key functions of the economic development unit for sustainable development as opposed to regular ways of doing things, as described by the participants during the interviews.

4.3 Experimentation

The design thinking workshop was actioned during the experimentation phase. Embedding design thinking in the experimentation phase allowed for the previous phases of the data collection and conceptualisation to serve as the planning for the design thinking workshop. During the experimentation phase, participants were invited to a design thinking workshop that was facilitated by the researcher. Key findings were acknowledged by the participants to be true and relevant. There was a greater focus on the exploration of problems and how more opportunities can be discovered with design thinking in a new way as compared to the routine ways of working in the public sector.

Participants were introduced to how complex problems can be addressed through design thinking in order to achieve sustainable development. The researcher highlighted the key function areas of research: job creation, industry support, social upliftment; and investment as predominate categories for economic development. This information emerged from the conceptualisation phase. Due to the nature of the research, the focus of the workshop was to highlight the approach of design thinking that could yield better outcomes as opposed to current ways of doing things. Therefore, the steps that were considered were problem statement, need-finding, defining and ideation. This provided sufficient evidence for the participants to recognise that design thinking has the potential to deliver superior outcomes, compared to the way they currently do things, by shifting focus to understanding problems from an end-user perspective instead of starting with outcomes that need to be achieved.

Interactive examples and case studies were used to demonstrate how design thinking can be used to innovate within their work areas. Participants were also given the opportunity to apply design thinking by collecting design research data and defining and ideating on examples provided by the researcher. The purpose of the experimentation phase was to gain feedback from the participants on the applicability of design thinking to their work activities. Active participation, such as the design thinking workshop, increases the quality of the research and improves the likelihood that the research results will be implemented and used. The design thinking workshop provided sufficient evidence for the participants to recognise that design thinking has the potential to deliver superior outcomes compared to the way they currently do things.

4.4 Analysis of results

The quality of the data was ensured through auditing and member checking. Auditing involved careful, detailed reflection on the data collection and analysis process. Member checking entailed confirming data collected and findings from the participants; this was done at the start of the design thinking workshop. Although there is no prescribed way to analyse phenomenology research, some studies have noted a general focus on first identifying independent themes from participants' experiences, followed by exploring patterns (Miller et al., 2018). The analysis of data, which was aligned with the ontological and epistemological position (Bleiker et al., 2019), was considered to be an interpretation of the construction of the participants' meanings of situations (Braun & Clarke, 2013). Therefore, it was not the intention of the researcher to establish a universal truth or test theories. Interpretive phenomenology research is successful when the researcher and participants reach a common understanding of the phenomenon. In this study, this was achieved through probing during the semi-structured interviews.

The qualitative research software NVIVO Pro 12 was used to code the interview data. The coding process entailed scrutinising each document for common themes and grouping details from each interview into a relevant theme. Thematic analysis was used for the analysis, following the identification of themes during the coding process to analyse and interpret the data. Coding involving grouping that had similar context. Thereafter, the thematic analysis involved reflecting on the data and describing the data with a theme.

4.5 Open-ended questions

Semi-structured interviews were used to interview participants of the study (Appendix A). This allowed for further probing.

5. FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

Economic development and economic growth have traditionally been viewed as the accumulation of physical capital, which increases the ability of governments to create wealth for their citizens. Economic transformation anticipates an outcome of higher productivity levels. Consequently, direct action often entails activities that will stimulate economic growth. Participants identified several initiatives to promote innovation to address the development challenges facing the municipality. Such initiatives consist of capacity building, community engagement and the assessment of community challenges; a context-based approach, depending on the needs of each department; an employment evidence-based approach; implementing innovation programmes; monitoring progress in economic sectors; partnerships with other stakeholders; promoting innovation awareness; providing access to basic services; providing funding for innovation; reforming action planning; encouraging staff to think outside the box; having strategic planning sessions; and supporting small businesses.

Participants highlighted that initiatives to address challenges were based on the context in which a community found itself, where it was understood that everyone has different needs. In this context, the municipality spent time researching how to contextualise the problem of a particular community before providing solutions. For instance, the officials sought to understand issues such as unemployment in the region and its contributing factors. In the film industry, they looked at ways of absorbing more people and the type of skills and intervention required. Whilst government officials favour the context-based approach, a participant believed that there were no processes to assess where the information is needed.

Internally, within the Municipality, current initiatives still haven't been able to adequately address sustainable development. Design thinking contributes to the fundamentals of thinking as a systematic approach to complex problem solving, from identifying challenges in the complex system to developing solutions. Starting to innovate in the Municipality was reported to be a bit challenging, as prior to initiatives, risk and mitigation assessments need to be done. Setting budgets and allocating resources were also challenging. There is much uncertainty throughout the innovation process, although it is still necessary to find ways to mitigate high risks in plans. Parts of a plan could more easily be left out if there is high uncertainty. This was seen as a deterrent to innovation, as it goes against a risk-taking culture, which is needed for innovation. There is a free flow of information on thought processes, such as how to engage, implement, or improve certain things. Things have more-or-less been done in the same way for the last ten years.

In terms of sustainable development, participants associated innovation with the alignment of the National Development Plan and as a mechanism for communication and coordination. Initiatives for sustainable development were noted; however, they appeared to be a bit piecemeal and lacked coherence. There was little clarity on how innovation can play a role in sustainable development. Participants viewed innovation as a driver of economic growth and as a means to improve their service delivery. However, none of the participants described how that can or is being done in the public sector, specifically for economic development. The execution of innovation is not a prominent feature in the municipality as yet. There is information and communication about innovation that occurs mostly in the government's role of promoting innovation in the external environment. The municipality does engage with industry on business ideas and new enterprises. The participants perceived this as innovation that improves business and improves the efficiency of IT systems.

Systems that are already in place at the Municipality are very rigid. This inculcates behaviours that discourage change. Creativity thus gets stifled in such an environment because there is more focus on ensuring that all procedures are adhered to and outcomes are foreseen. Individuals are afraid of stepping out of such a system for fear of being questioned. It has also been ingrained as the norm and has become second nature. Building internal capacity and adopting a better approach to problem-solving reduces the risk of reliance on external skills. Design theory can be used for complex situations where classical problem-solving is insufficient (Jones, 2014). Design thinking has received acceptance and has gained much popularity due to efficient and speedy results in innovation.

Strategic planning sessions are held during staff meetings as a means to develop projects and programmes that are aligned with the outcomes of the IDP. Services rendered by the municipality have become restricted due to limited resources and an over-dependence on government. The municipality has developed a high-level consultative process which meets quarterly with captains of business to understand their needs. As complexity increases, it outweighs control and can become a hindrance (Liu et al., 2015). Complexity in a system consists of diverse components, such as people. It describes the behaviours and certain properties as they appear in the surroundings, which may display non-linear interactions that may change over a period of time (CECAN, 2019). Whilst engaging in a fact finding mission, the complexity and depth of problems are not factored into the process. Consultative processes only serve to gather people's perceptions and are not a systematic approach to understanding problems. Design thinking adds a new function in understanding problems with greater depth by starting with being empathetic towards citizens and understanding their needs by conducting design research.

Although the IDP provides a guide on specific outcomes, uncertainty remains on pathways towards achieving these outcomes. The municipality focuses on development planning that will have a long-term impact, and protecting the most vulnerable is one of the main focal points. The participants perceived economic empowerment to be the driving force behind sustainable development. Participants claimed that the municipality was not adequately playing its role, as actions are more reactive, rather than addressing problems. One of the reasons for this was seen to be an issue with their problem-solving capacity or with having adopted a practical problem-solving approach, such as design thinking. Steps have not been taken too seriously to implement such techniques. Instead of being focused on GDP, attention should be shifted to a foundation of well-being for all humanity, which is redistributive and regenerative and enables a more sustainable economy (Schokkaert, 2019).

A participant described the IDP as a reference to the actions that they take. Significant emphasis has been placed on setting out projected results. However, guidance on the path towards achieving the SDGs garners very little attention. What appears to be lacking is more systematic mechanisms for problem-solving that will yield better outcomes. Hence, effective action has been elusive since achieving sustainability remains complex and requires coherence. The researcher facilitated a design thinking workshop with the participants of the study. This was the third step of the action research cycle, as depicted in Figure 1. The advantage of embedding the design thinking workshop in the experimentation phase is that the preceding phases of data collection and conceptualisation formed the basis of the study. The data collection focused primarily on the ways of working of the participants that could be linked to innovation. During the conceptualisation phase, the researcher utilised the raw data to determine the key findings of the study and extract key function areas where design thinking could be used as a new intervention.

Participants highlighted areas such as research, social upliftment, industry support and job creation as some of the key function areas for economic development and where most of their work activities were based. Participants viewed one of the main roles of the Economic Development Unit as being to create an enabling environment for businesses and citizens to thrive, specifically for job creation. The data revealed that some of the ways this was done were to partner with the private sector to create job opportunities, and the public sector also created numerous skills development programmes. The researcher used this as an opportunity to incorporate job creation into the design thinking workshop to experiment with using design thinking as a new approach to this problem. This was most relevant to SDG 8 for decent work and economic growth. Job creation addresses unemployment. With unemployment, the end users of potential innovations for this were unemployed people. These areas formed the basis of the design thinking workshop, where stories were drawn from unemployment, social upliftment, research and industry support to highlight the ability of design thinking as a strategic problem-solving mechanism can deliver multiple solutions that are different to the current ways of doing things with an inclination entirely towards policy, strategy and research. Participants highlighted that initiatives at the Municipality were largely influenced by policy, strategy and research; examples of support services are shown in Table 1.

A social media post was used as one of the stories for the design thinking workshop. This depicted a young graduate, standing alongside a busy road, holding up a signboard with his credentials, trying to get the attention of relevant professionals who he probably knew would be driving that way at peak hour. The author of the post viewed this young man as someone from the township, cited unemployment in townships as a problem, and described how the solution of entrepreneurship was most appropriate to address this problem. One of the most common interventions for unemployment proposed by governments all over the world has been entrepreneurship, as shown in Table 1, with several research studies and programmes to promote the initiative. During the workshop, the researcher first discussed design thinking. Participants then looked at the social media post with a design-thinking mindset. The researcher explained that, at first glance, many would see unemployment in townships, but design thinking puts humans first. Thus, the design research entailed understanding the young graduate. Upon empathising with the young graduate, participants understood him as being a jobseeker and experiencing various challenges in this regard. Participants then followed the phases of design thinking and generated several ideas, such as understanding the process of applying for jobs. As shown in Table 2, design thinking shifts the problem to higher degrees of specificity where a whole new range of solutions can be developed.

The workshop also included stories related to improving research, social upliftment and industry support, where similar to Table 2, current practices derived from the data collection were compared to using design thinking. Participants provided feedback after the workshop and concluded that design thinking has the potential to improve economic development outcomes. Given the amount of reference documentation that governments have to adhere to, such as policies, strategic planning, performance outcomes and various other government frameworks, participants have stated that conforming to these guidelines takes preference, and although they are faced with challenges where there is no roadmap for its resolve, it still has to be done within a stipulated parameter. As shown in Table 2, current practices of regular support services become ongoing solutions and allow for much lateral thinking. Design thinking can supplement current practices in economic development as a strategic tool for problem-solving in order to generate alternative solutions.

6. MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS

a) Shift in strategic planning approaches by integrating design thinking into economic development strategies. Traditional economic planning often relies on rigid, linear models. Design thinking introduces a flexible, iterative approach that allows managers to better understand complex problems and explore multiple innovative solutions aligned with sustainable development goals.

b) Invest in training and capacity-building programs to enhance problem-solving capabilities using design thinking principles. Managers should prioritise staff development that focuses on empathy, ideation, prototyping, and testing. These skills are crucial for addressing multifaceted economic and social challenges in more creative and adaptive ways.

c) Create enabling environments that support innovation, collaboration, and risk-taking within municipal and organisational contexts. To foster innovation, management should reduce bureaucratic barriers, encourage cross-sector collaboration, and create safe spaces for experimentation and learning from failure.

d) Embed Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG 8, into operational and strategic frameworks. Managers need to align local development initiatives with global objectives like decent work and economic growth. Design thinking can help tailor these goals to local contexts by focusing on user needs and systemic impact.

e) Redesign policies and programs using participatory, iterative methods aligned with design thinking. Instead of top-down policy development, managers can involve stakeholders in co-creating solutions. Iterative prototyping and testing ensure policies are both practical and responsive to changing circumstances.

f) Improve stakeholder engagement through human-centred approaches that increase the relevance and effectiveness of initiatives. Design thinking emphasises a deep understanding of user needs and inclusive engagement. This results in solutions that are more acceptable, impactful, and sustainable in the long term.

7. CONCLUSION

South Africa has been consistently experiencing substantially low growth rates coupled with high unemployment rates. Whilst the United Nations has conceptualised targets for the future in the form of sustainable development goals, there has been stagnation in delivering these goals due to little guidance on how these goals should be implemented. This study contributes to a new approach to addressing SDG 8 by implementing goal number eight with innovation. The use of design thinking in this study has highlighted how economic development outcomes can be improved by facilitating the lessening of complex problems with design thinking. This study further contributes to the development of innovation management in South Africa by enabling more people, especially within the public sector, to conceptualise innovations with design thinking.

The contribution of this research is a new approach to improving economic development outcomes with design thinking that addresses sustainable development. Traditional economics focuses largely on GDP and growth rates. This results in most decisions being made on a larger scale, where the resolutions are non-inclusive. Design thinking shifts focus to the livelihoods of people. Participants in this study have explained that they work mostly at the sector level. Design thinking takes problem-solving to a human level to understand what people are actually experiencing in order for systematic changes to be made. This study prompts new public governance surrounding development planning at municipalities in South Africa.

Organisations often use design thinking to develop products and services. This study added a new step prior to the problem space by utilising action research to understand the organisation's work environment and conceptualising areas where design thinking can be applied. The participants reflected on their work environment and answered interview questions pertaining to ways of working. Key function areas and findings were conceptualised to form the basis for the experimentation phase of the design thinking workshop. For the purpose of this research, all phases in the action research cycle were applied in this study; and the final phase of the analysis of findings was generated through coding the interview data, followed by a thematic analysis.

The SDGs present outcomes where the action of sustainable development has to be acquired through a series of multiple changes that result in improvements. Although innovation has been featured in achieving the SDGs, it has been through isolated initiatives. Systemic mechanisms that individuals can utilise to develop solutions towards the SDGs have been severely lacking. Design thinking shifts focus to understanding complex problems where multiple solutions may be developed to serve as improvements that contribute to the SDG. Current ways of doing things in areas such as industry support involve governments using economic indicators and incorporating sector-level problems in order to improve economic growth. Introducing design thinking shifts focus to industry support, becoming customer-centric, where economic growth can be improved by understanding problems on a human level. Similarly, introducing design thinking to other economic functions shifts to a new way of doing things that results in better outcomes. Further, design thinking in the public sector has often been associated with social innovation and process optimisation; this study contributes to utilising design thinking for economic transformation by reframing economic development challenges with design thinking.

The design thinking workshop with the participants of the study provided sufficient evidence for the participants to recognise that design thinking has the potential to deliver superior outcomes compared to the way they currently do things by shifting focus to understanding problems from an end-user perspective instead of starting with outcomes that need to be achieved. Design thinking can be used for finding improvements for current innovations or developing new innovations. The logic of this study does not propose that design thinking should be intertwined with policy, which is a top-down approach. Design thinking as a problem-solving mechanism should be used as a bottom-up action to develop improved solutions. Since design thinking is predominately intuitive, it should be independent of government processes and analytical systems.

Government entities will benefit mainly from this study. Current ways of doing things can be reflected upon, and new public governance outcomes can be envisioned. Policy making can be improved with better problem definitions derived from design thinking. Public value can thus be enhanced through a greater understanding of citizens' needs and experiences. This

study also presents new knowledge that will benefit educators and consultants who work with public sector entities. Sustainable development is a matter that should be everyone's responsibility, not only governments. Corporate companies that support societal development will also benefit from this study in that it adds a new area of business for supporting the SDGs with innovation.

This study focused on the applicability of design thinking to sustainable development. Design thinking was shown to supplement traditional economic development interventions that are set out by policies and strategic frameworks by shifting the problem to higher degrees of specificity, thereby allowing for more solutions that address sustainable development to be developed. Future work will utilise the action research strategy from this study in multiple cycles, which will allow for multiple design thinking workshops that will explore insights into further improving the problem capacity and understanding how design thinking can be integrated into the organisation. The public sector is a highly regulated environment that is fraught with stringent structures and processes that often don't allow for the flexibility for innovation to flourish. Future work will include a focus on the implementation of design thinking.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship and publication of the article.

Data availability: N/A

Ethical clearance and informed consent statement: The researchers obtained ethical clearance (HSSREC/00000634/2019) and signed informed consent forms from all the participants in this study prior to data collection.

Funding: The authors did not receive any financial support for research, authorship and publication of the article.

REFERENCES

Amidu, A.R., Boyd, D. & Gobet, F. 2019. A protocol analysis of use of forward and backward reasoning during valuation problem solving. Property Management, 37(5):638-681. [https://doi.org/10.1108/PM-10-2018-0056]. [ Links ]

Beckman, S.L. 2020. To Frame or Reframe: Where Might Design Thinking Research Go Next? California Management Review, 62(2):144-162. [https://doi.org/10.1177/0008125620906620]. [ Links ]

Bleiker, J., Morgan-Trimmer, S., Knapp, K. & Hopkins, S. 2019. Navigating the maze: qualitative research methodologies and their philosophical foundations. Radiography, 25(S1):S4-S8. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radi.2019.06.008]. [ Links ]

Breuer, A., Janetschek, H. & Malerba, D. 2019. Translating sustainable development goal (SDG) interdependencies into policy advice. Sustainability, 11(7):2092. [https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072092]. [ Links ]

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. 2013. Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Callahan, K.C. 2019. Design Thinking in Curricula. The International Encyclopedia of Art and Design Education, 1-6. [https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118978061.ead069]. [ Links ]

CECAN. 2019. Complexity evaluation framework. Complexity Evaluation Framework - CECAN. [Internet: https://www.cecan.ac.uk/resources/complexity-evaluation-framework; downloaded on 15 May 2024]. [ Links ]

Chan, J.K. 2018. Design ethics: Reflecting on the ethical dimensions of technology, sustainability, and responsibility in the Anthropocene. Design Studies, 54:184-200. [https://doi.org/10.1016/i.destud.2017.09.005]. [ Links ]

Chen, X., Liu, Z. & Ma, C. 2017. Chinese innovation-driving factors: regional structure, innovation effect, and economic development-empirical research based on panel data. The Annals of Regional Science, 59:43-68. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-017-0818-5]. [ Links ]

Clune, W.H. & Zehnder, A.J. 2018. The three pillars of sustainability framework: approaches for laws and governance. Journal of Environmental Protection, 9:211-240. [https://doi.org/10.4236/jep.2018.93015]. [ Links ]

Creswell, J.W. & Creswell, J.D. 2017. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Da Silva, R.T. 2019. From Effect to Cause: Deductive Reasoning. Kairos. Journal of Philosophy and Science, 22(1):109-131. [https://doi.org/10.2478/kjps-2019-0011]. [ Links ]

Eisenhardt, K.M., Graebner, M.E. & Sonenshein, S. 2016. Grand challenges and inductive methods: Rigor without rigor mortis. Academy of Management, 59(4):1113-1123. [https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.4004]. [ Links ]

Etikan, I. & Bala, K. 2017. Sampling and sampling methods. Biometrics & Biostatistics International Journal, 5(6):00149. [https://doi.org/10.15406/bbij.2017.05.00149]. [ Links ]

Fagerberg, J. & Srholec, M. 2017. Capabilities, economic development, sustainability. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 41(3):905-926. [https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bew061]. [ Links ]

Firoiu, D., lonescu, G.H., Băndoi, A., Florea, N.M. & Jianu, E. 2019. Achieving sustainable development goals (SDG): Implementation of the 2030 Agenda in Romania. Sustainability, 11(17):2156. [https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072156]. [ Links ]

Hajer, M., Nilsson, M., Raworth, K., Bakker, P., Berkhout, F., de Boer, Y., Rockström, J., Ludwig, K. & Kok, M. 2015. Beyond cockpitism: Four insights to enhance the transformative potential of the sustainable development goals. Sustainability, 7(2):1651-1660. [https://doi.org/10.3390/su7021651]. [ Links ]

Hautamäki, A. & Oksanen, K. 2016. Sustainable innovation: Solving wicked problems through innovation. In: Open Innovation: A Multifaceted Perspective: Part I. World Scientific, April(2016):87-110. [https://doi.org/10.1142/97898147191860005]. [ Links ]

Ioppolo, G., Cucurachi, S., Salomone, R., Saija, G. & Shi, L. 2016. Sustainable local development and environmental governance: A strategic planning experience. Sustainability, 8:180. [https://doi.org/10.3390/su8020180]. [ Links ]

Jones, P.H. 2014. Systemic design principles for complex social systems. In: Social Systems and Design. Springer. [https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-54478-4_4]. [ Links ]

Kahn, K.B. 2018. Understanding innovation. Business Horizons, 61(3):453-460. [https://doi.org/10.1016/i.bushor.2018.01.011]. [ Links ]

Kolb, A. & Kolb, D. 2018. Eight important things to know about the experiential learning cycle. Australian Educational Leader, 40(3):8-14. [ Links ]

Lambrechts, W. & Van Petegem, P. 2016. The interrelations between competencies for sustainable development and research competencies. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 17:776-795. [https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-03-2015-0060]. [ Links ]

Liebenberg, E. 2020. Human-centred design and innovative research methods for healthcare. Sight and Life, 34:50-56. [https://doi.org/10.52439/DTOA2623]. [ Links ]

Liu, H., Ma, L. & Huang, P. 2015. When organizational complexity helps corporation improve its performance. Journal of Management Development, 34(3):340-351. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-05-2013-0071]. [ Links ]

Mensah, J. 2019. Sustainable development: Meaning, history, principles, pillars, and implications for human action: Literature review. Cogent Social Sciences, 5(1):1653531. [https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2019.1653531]. [ Links ]

Messerli, P., Murniningtyas, E., Eloundou-Enyegue, P., Foli, E.G., Furman, E., Glassman, A., Hernández Licona, G., Kim, E.M., Lutz, W. & Moatti, J.-P. 2019. Global Sustainable Development Report 2019: The future is now - science for achieving sustainable development. New York: United Nations. [Internet: https://sdgs.un.org/gsdr/gsdr2019; downloaded on 15 May 2024]. [ Links ]

Miller, R.M., Chan, C.D. & Farmer, L.B. 2018. Interpretative phenomenological analysis: A contemporary qualitative approach. Counselor Education and Supervision, 57(4):240-254. [https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12114]. [ Links ]

Morgan, J. 2015. What is neoclassical economics? Debating the origins, meaning and significance. London: Routledge. [https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315659596]. [ Links ]

Moyer, J.D. & Hedden, S. 2020. Are we on the right path to achieve the sustainable development goals? World Development, 127:104749. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104749]. [ Links ]

Oeij, P.R., Van der Torre, W., Vaas, F. & Dhondt, S. 2019. Understanding social innovation as an innovation process: Applying the innovation journey model. Journal of Business Research, 101:243-254. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.04.028]. [ Links ]

Opon, J. & Henry, M. 2019. An indicator framework for quantifying the sustainability of concrete materials from the perspectives of global sustainable development. Journal of Cleaner Production, 218:718-737. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.01.220]. [ Links ]

OPSI. 2019. Embracing innovation in government: Global trends 2019. Paris: OECD. [Internet: https://oecd-opsi.org/publications/emerging-trends; downloaded on 15 May 2024]. [ Links ]

Pavel, A. & Moldovan, O. 2019. Determining local economic development in the rural areas of Romania. Exploring the role of exogenous factors. Sustainability, 11(1):282. [https://doi.org/10.3390/su11010282]. [ Links ]

Price, R., Wrigley, C. & Matthews, J. 2018. Action researcher to design innovation catalyst: Building design capability from within. Action Research, 19(2):318-337. [https://doi.org/10.1177/1476750318781221]. [ Links ]

Raszkowski, A. & Bartniczak, B. 2018. Towards sustainable regional development: economy, society, environment, good governance based on the example of Polish regions. Transformations in Business and Economics, 17(2):225-245. [ Links ]

Sato, T. & Laughlin, D.D. 2018. Integrating Kolb's Experiential Learning Theory into a sport psychology classroom using a golf-putting activity. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 9(1):51-62. [https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2017.1325807]. [ Links ]

Schokkaert, E. 2019. Review of Kate Raworth's Doughnut Economics. London: Random House, 2017, 373 pp. Erasmus Journal for Philosophy and Economics, 12(1):125-132. [https://doi.org/10.23941/ejpe.v12i1.412]. [ Links ]

Stompff, G., Smulders, F. & Henze, L. 2016. Surprises are the benefits: reframing in multidisciplinary design teams. Design Studies, 47:187-214. [https://doi.org/10.1016/i.destud.2016.09.004]. [ Links ]

Szopik-Depczynska, K., Kçdzierska-Szczepaniak, A., Szczepaniak, K., Cheba, K., Gajda, W. & loppolo, G. 2018. Innovation in sustainable development: an investigation of the EU context using 2030 agenda indicators. Land Use Policy, 79:251-262. [https://doi.org/10.1016/i.landusepol.2018.08.004]. [ Links ]

Thomas, J. & McDonagh, D. 2013. Empathic design: Research strategies. The Australasian Medical Journal, 6(1):1-6. [https://doi.org/10.4066/AMJ.2013.1575]. [ Links ]

Tjarve, B. & ZemTte, I. 2016. The role of cultural activities in community development. Acta Universitatis Agriculturae et Silviculturae Mendelianae Brunensis, 64:2151-2160. [https://doi.org/10.11118/actaun201664062151]. [ Links ]

Van Manen, M. 2016. Phenomenology of practice: Meaning-giving methods in phenomenological research and writing. London: Routledge. [https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315422657]. [ Links ]

Wolniak, R. 2017. The Design Thinking method and its stages. Systemy Wspomagania w Inzynierii Produkcji, 6(6):247-255. [ Links ]

* corresponding author

Annexure A: Semi-structured interview questions

1. What is the understanding of sustainable development at the municipality?

2. What is the importance of innovation to the government?

3. How is innovation encouraged?

4. What are the factors that inhibit innovation outcomes?

5. How does the municipality contribute to innovation in the city?

6. Describe how the Municipality engages with societal challenges related to the sustainable development goals.

7. Describe how innovation ideas are identified and realised.

8. How does the Municipality treat innovation as a long-term strategy for economic growth and social well-being?

9. Does the Municipality have a tolerance for risk, ambiguity and uncertainty? Please elaborate.

10. Describe how the Municipality views the problems of citizens within the context of a broader vision.