Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Chemistry

On-line version ISSN 1996-840XPrint version ISSN 0379-4350

S.Afr.j.chem. (Online) vol.79 Durban 2025

https://doi.org/10.17159/0379-4350/2025/v79a08

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Unveiling the Anticancer Properties of Xanthone Derivatives: Molecular Docking, Molecular Dynamics simulation, MM-PBsA calculation, and Pharmacokinetics Prediction

Lathifah Puji HastutiI, II, *; Faris HermawanIII; Teni ErnawatiIII; Lala Adetia MarlinaIV; Nicky Rahmana PutraIII; Ervan YudhaV; Savira EkawardhaniVI; Kevin Muhamad LukmanI, *

IGraduate School, Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung, Indonesia

IIResearch Center of Biotechnology Molecular and Bioinformatic, Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung, Indonesia

IIIResearch Center for Pharmaceutical Ingredient and Traditional Medicine, National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), Tangerang Selatan, Banten, Indonesia

IVResearch Center for Computing, National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), Cibinong, Bogor, Indonesia

VDepartment of Chemistry, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

VIDepartment of Biomedical Science, Parasitology Division, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung, Indonesia

ABSTRACT

This investigation evaluates the potential of xanthone derivatives to inhibit cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK2) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) through molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulation, binding energy analysis using MM-PBSA, and ADMET predictions. Molecular docking results revealed that the binding energies of all xanthone derivatives (X1-X6) ranged between -6.69 and -7.39 kcal/mol for the CDK2 protein and -6.25 to -6.85 kcal/mol for the EGFR protein. Furthermore, a 50-nanoseconds molecular dynamics simulation showed that the root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 1-(dimethylamino)-3,4,6-trihydroxy-9H-xanthen-9-one (X3) and 3,4,6-trihydroxy-2-mercapto-9H-xanthen-9-one (X4) maintained stable interactions within the protein's active site. The root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) analysis indicated that these xanthone derivatives exhibited similar amino acid fluctuation patterns to the native ligands (C62 and erlotinib), suggesting comparable binding interactions. Binding energy assessments via MM-PBSA demonstrated that 1-(dimethylamino)-3,4,6-trihydroxy-9H-xanthen-9-one (X3) and 3,4,6-trihydroxy-2-mercapto-9H-xanthen-9-one (X4) had lower binding energies than the native ligands (C62 and erlotinib) and doxorubicin. Additionally, these compounds adhered to Lipinski's rule and met the minimum requirements in ADMET property predictions. In conclusion, 1-(dimethylamino)-3,4,6-trihydroxy-9H-xanthen-9-one (X3) and 3,4,6-trihydroxy-2-mercapto-9H-xanthen-9-one (X4) demonstrate significant potential as therapeutic candidates for cancers associated with CDK2 and EGFR dysregulation, warranting further research and development.

Keywords: anticancer, in-silico, molecular dynamics, molecular docking, xanthones

INTRODUCTION

Cancer, a complex group of illnesses characterized by uncontrolled cell proliferation and abnormal cell dissemination, poses a significant challenge to human health.1-3 Genetic and epigenetic alterations cause disruptions in vital cellular functions, such as the activation of oncogenes and suppression of tumor-suppressor genes.3,4 These irregular cellular behaviors result in the formation of tumors that invade nearby tissues and organs, interfering with normal physiological processes. Cancer progression involves a multifaceted sequence of events, including cellular proliferation, tissue invasion, angiogenesis, and metastasis to distant body regions.5,6 Intricate intracellular signalling networks govern these processes. Changes within these pathways, such as mutations affecting cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK/Cyclins), can drive the accelerated growth of malignant cells.7

Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2) primarily interacts with cyclins A, B, and E, which are pivotal in regulating the cell cycle, particularly during the G1 to S phase transition. In normal, healthy cells, CDK2 is not essential, as CDK1 can perform its functions by compensating or mimicking specific roles.8 However, CDK2 is critical for the proliferation and progression of cancer cells.8,9 Similarly, the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), located on the surface of epithelial cells, is part of the tyrosine kinase receptor family. It is activated by natural ligands like epidermal growth factor (EGF), initiating signalling pathways that restore normal cellular functions. Overexpression of EGFR, however, can promote tumor growth and progression, facilitating angiogenesis, tissue invasion, and metastasis through pathways such as Ras/Raf/ MAPK, P1K-3/AKT, PLC-PKC, and STAT. Consequently, EGFR has emerged as a significant target in cancer therapy.10,11 Thus, these proteins serve as promising targets for the development of anticancer agents.

Computational modelling has become a cornerstone of anticancer drug discovery, revolutionizing the identification and design of potential therapeutic compounds.12 Techniques such as molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations employ mathematical algorithms to assess drug-target interactions and stability.13,14 Additionally, ADMET (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity) predictions are used to evaluate drug feasibility. 1ntegrating network pharmacology and machine learning enhances this process by elucidating complex protein-protein interactions and predicting ADMET properties.15,16 These computational tools collectively form a robust and efficient framework, enabling rapid, cost-effective innovation in anticancer drug development.17-19

Xanthone, a heterocyclic compound with the formula 9H-xanthene-9-one, is recognized for its diverse pharmacological activities.20,21 Its biological functions, attributed to its molecular structure, include antibacterial,19,22 anti-inflammatory,23 a-glucosidase inhibitory,21 antiviral,12 and anticancer properties.24,25 Several studies have highlighted the anticancer potential of xanthone derivatives. Tang et al. (2016) identified novel xanthone derivatives with notable anticancer activity against A549, HepG2, HT-29, PC-3, and HL-7702 cell lines, with 1C50 values ranging from 3.90 to 10.0 µM.26 Huang et al. isolated and characterized two xanthones - 1,7-dihydroxy-2-methoxy-3-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)-9H-xanthen-9-one and 1-hydroxy-4,7-dimethoxy-6-(3-oxobutyl)-9H-xanthen-9-one-that showed moderate cytotoxicity against KB and KBv200 cells.27 Fatmasari et al. (2022) demonstrated that hydroxyxanthone derivatives effectively inhibited WiDr, MCF7, and HeLa cancer cells, highlighting the role of hydroxyl groups in enhancing anticancer activity.28 Similarly, Miladiyah et al. (2018) explored the biology, QSAR analysis, and molecular docking of xanthone derivatives on HeLa and WiDr cells, reporting IC5q values between 0.049 and 0.960 µM. They confirmed the positive impact of hydroxyl group inclusion on anticancer efficacy through in vitro assays.9,29

Despite extensive studies on xanthone derivatives, no existing research has comprehensively investigated their molecular interactions with CDK2 and EGFR proteins using a combination of molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations, MM-PBSA binding energy calculations, and ADMET property predictions. This study aims to fill this gap by analyzing xanthone derivatives with hydroxy, amine, dimethylamine, methoxy, and thio substituents to elucidate their inhibitory mechanisms, binding interactions, and stability at the active sites of these target proteins. The integration of these computational approaches provides a deeper understanding of the structure-activity relationship, offering insights into the potential of xanthone derivatives as selective kinase inhibitors. Furthermore, this study provides a predictive framework for assessing the anticancer activity of xanthone derivatives before conducting laboratory-scale experiments, thereby optimizing the drug discovery process.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Material

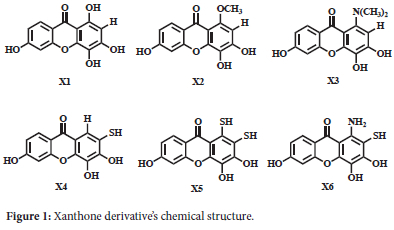

The intended crystal protein structures were extracted from the protein data bank (www.rcsb.org) (CDK2 PDB ID: 2UZO and EGFR PDB ID: 1M17). The target proteins were created by eliminating cofactors and water molecules from their structure, employing the UCSF Chimera software.30 A series of xanthone derivatives was used as ligands, and their chemical structures are shown in Figure 1.

Optimizing Xanthone Derivatives

The xanthone derivatives (X1-X6) were represented as three-dimensional (3D) structures using Avogadro software.31 Subsequently, their structures were optimized using Orca software using a DFT B3LYP 3-21G method and saved in the .pdb format.32,33

Molecular Docking

The crystal structures of complex CDK (PDB ID: 2UZO) and EGFR Protein (PDB ID: 1M17) were obtained from the RSCB Protein Data Bank (www.rcsb.org). The Chimera software was utilized to create and save the protein and native ligand structures as files in the PDB format. The structures of the xanthone derivatives were created using Avogadro software and subsequently optimized using Orca software using a DFT B3LYP 3-21G method. The optimized structures were saved in the .pdb format. AutoDock4 was used to perform docking simulations and redocking.34,35 The CDK2 protein was positioned within a grid box with dimensions of 40x40x40 Å, and the center grid box of 11.34x-8.22x9.73 Å in the x, y, and z directions, whereas the EGFR protein was positioned within a grid box of 42x40x40 Å and the center grid box of 21.69x0.30x52.09 Å. The Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm (LGA) was employed for 40 runs of docking, and the resulting molecular docking results were shown using BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer (DSV).36

Molecular Dynamics Simulation and MM-PBSA Free Energies Calculation

The GROMACS 2020 software performed molecular dynamics simulation for X1-X6, doxorubicin, and natural ligands against CDK2 and EGFR protein.37,38 The simulation process was conducted using the GROMACS 2020 software.39,40 The molecular dynamics simulation of xanthone complexes employed the Charmm36 force field. The cgenff server was used to generate ligand topology parameters for every molecule.40 After applying PBC (periodic boundary condition) to replicate the system, positive and negative ions were added to the box to neutralize it. Reduction in size steepest descent method for one ns was used to determine the energy, and minimization stopped when the energy reached 100 kJ/mol. At 300 K and 1 atm, NVT and NPT ensembles were run for one ns each with a dt of 2 fs. The system conditions were precisely controlled under isotropic conditions. The long-range electrostatic interactions were handled using the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method, while the modified Berendsen thermostat facilitated temperature coupling through the v-rescale algorithm.41 The MD production data were gathered under the same conditions for 50 ns. The results of the MD simulation included the hydrogen bond, RG (radius of gyration), RMSF (root mean square fluctuation), and RMSD (root mean square deviation).

Physicochemical and ADMET properties

ADMET refers to the biological processes involved in the absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity of medicine in an organism. The ADMET descriptors in Discovery Studio 3.5 (Accelrys) were used to predict these attributes. The pkCSM web server received the uploads of xanthone derivatives X1-X6 in SMILES format, one at a time.16,42 The physicochemical and ADMET parameters were determined by selecting the ADMET menu. Subsequently, the pkCSM presented the statistics for each drug, encompassing Lipinski's rule of five: absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Redocking against CDK2 and EGFR Protein

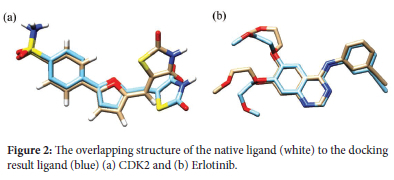

Molecular docking simulations were conducted for six xanthone derivatives targeting two anticancer proteins, CDK2 and EGFR. The Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) values, which measure the accuracy of docking simulations, consistently remained below 2 Å (39). This demonstrates the reliability of the docking parameters employed in this study. The precision of these results enhances the validity and credibility of the findings, boosting confidence in the outcomes. A redocking analysis for the CDK2 protein showed that the native ligand, C62, exhibited a binding energy of -9.49 kcal/mol with an RMSD value of 1.52 Å. Similarly, erlotinib, the native ligand for EGFR, displayed a binding energy of -7.05 kcal/mol with an RMSD value of 1.59 Å. Both RMSD values below 2 Å confirm that the docking methodology and parameters used were sufficiently accurate for investigating the molecular docking of xanthone derivatives. Figure 2 shows the native ligand's overlapping structure with the ligand redocking results.

Molecular Docking Study of Xanthone Derivatives Against CDK2 Protein

The docking analysis was conducted to provide a visual understanding of the interaction between xanthones and the CDK2 protein target, offering insights into their potential mechanism of action. The xanthone derivatives (X1-X6) were docked into the same binding site as the native ligand of the CDK2 protein receptor. These compounds were positioned within the active region of the CDK2 protein to evaluate their potential interactions as anticancer candidates. The CDK2 protein structure, available in the Protein Data Bank (PDB), includes a ligand identified as 4-{5-[(Z)-(2,4-dioxo-1,3-thiazolidin-5-ylidene)methyl]furan-2-yl}benzenesulfonamide, referred to as C62.

Table 1 shows that the binding energies of the xanthone derivatives (X1-X6) ranged from -6.69 to -7.39 kcal/mol. These binding energies were higher than those of C62 (-9.49 kcal/mol) and doxorubicin (-7.84 kcal/mol), indicating that the xanthones exhibited lower inhibitory activity against the CDK2 protein compared to C62 and doxorubicin. Additionally, the presence of different functional groups influenced the binding energy values. Among the derivatives, the dimethylamine group in compound X3 demonstrated the most favorable binding energy of -7.39 kcal/mol, surpassing compounds X1 (-7.04 kcal/mol) and X2 (-6.69 kcal/mol).

Figure 3 shows the 2D diagram of various interactions between the residues and the ligand, such as hydrogen bonds, atomic charge, and Pi-sigma interactions. The difference in the binding affinity values of each compound is influenced by the types of bonds formed during the docking process. The inhibitory activity of xanthone can be attributed to two primary factors: Hydrogen bonding and pi-sigma interactions. Hydrogen bonds play a crucial role in determining the binding affinity due to their higher energy compared to hydrophobic bonds.10 This higher energy contributes significantly to the stability and strength of the interactions between the compounds and the target protein. Native ligand C62 and doxorubicin interacted with Lys33, Leu83, Asp86, Asp145, and Ile10. The hydrogen bond formation of xanthone derivatives is analogous to that of the native ligand C62, occurring with the amino acid residues Asp86, Asp145, and Lys33. These interactions indicate that xanthone derivatives (X1-X6) exhibit equivalent inhibitory activity against the CDK2 protein as the C62 ligand.

Molecular Docking Study of Xanthone Derivatives Against EGFR Protein

We also examine the anticancer activity of xanthone derivatives (X1-X6) against the EGFR protein. The Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) is a transmembrane protein classified within the ErbB/HER family of tyrosine kinase receptors. Somatic mutations and excessive expression of EGFR have been documented to have a crucial impact on the growth and advancement of cancer cells, encompassing cell proliferation, differentiation, angiogenesis, apoptosis, and metastasis. Therefore, EGFR is an important therapeutic target for treating different epithelial malignancies. The X1-X6 was docked in the same position as the native ligand of the EGFR protein receptor. As shown in Table 1, the binding energy of xanthone derivatives (X1-X6) falls within the range of -6.25 to -6.85 kcal/mol. The compounds exhibited higher binding energies compared to the ligands erlotinib (-7.05 kcal/mol) and doxorubicin (-10.23 kcal/mol), suggesting that all xanthones had weaker inhibitory action against the EGFR protein than erlotinib and doxorubicin. Moreover, the presence of various functional groups impacted the binding energy value in comparison to other substituents. Compound X3 had the most favorable binding energy (-6.85 kcal/mol) among the three compounds, X1 (-6.25 kcal/mol) and X2 (6.61 kcal/mol), due to the presence of the dimethyl amine group.

The 2D interaction of erlotinib, doxorubicin, and X3 compound over the EGFR are shown in Figure 4, respectively. The X1-X6 complex firmly adheres to the active site of EGFR. Establish primary amino acid interactions with the following residues: Thr766, Lys721, Gln767, Met769, Pro770, Asp831, and Glu738. These amino acid residues have a crucial function in predicting the binding site of EGFR and the mechanism of catalysis. The xanthone derivatives form hydrogen bonds and van der Waals interactions with specific amino acids (Met769, Lys721, Asp831, Arg817, Thr766) in the EGFR binding pocket. The ligand-EGFR complexes naturally lead to inter- and intramolecular interactions, including hydrogen bonding, pi-pi stacking, pi-cation, and salt bridge formation.37 It was reported that the interactions with key amino acid residues of EGFR, i.e., Gly695, Gly700, Glu767, Met769, Asp831, Gly833, Arg812, Asp818, and Tyr845, were pivotal to the suppression of cancer cell division.38 The X3 compound exhibited a -6.85 kcal/mol binding energy while establishing the hydrogen bonding interaction with Pro770, Gln767, and Met769. It was found that the X3 compound has the lowest binding energy of the other xanthone derivatives, indicating that the dimethylamine substituent in the xanthone core influences the anticancer activity. The findings suggest that X1-X6 can deactivate the EGFR protein receptor and inhibit the proliferation of cancer cells. The xanthone derivatives X1-X6 exhibit variations in their molecular size, conformation, physicochemical properties, and pharmacokinetic profiles.17 Other research groups have discovered that these variations can potentially overcome doxorubicin resistance in specific cancer cells.42,43

Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Xanthone Derivatives against CDK2 Protein

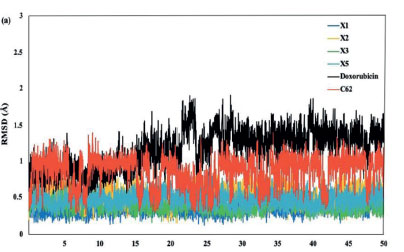

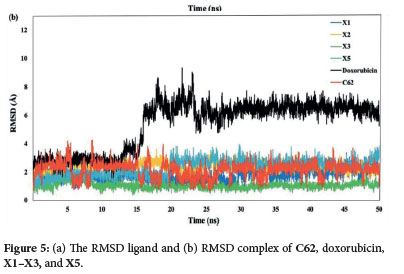

To further validate the interaction of docking conformers, the molecular dynamics (MD) simulation was performed to analyze the interaction of amino acid residues. We did the 50 ns MD between the CDK2 protein and its native ligand, doxorubicin, and the X1, X2, X3, and X5 xanthone derivatives. The MD simulation results gave some information, including the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) of ligand and complex with protein, the Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) of the simulation system backbone, the Radius of Gyration (Rg), and the hydrogen bond. As shown in Figure 5a, the RMSD values of the ligands are in the range of 0.25 to 2 Å., indicating limited movement within the protein's active site and consistent ligand-protein interactions over the 50 ns simulation.44 Subsequently, doxorubicin and C62 showed higher RMSD complex compared to compounds X1-X3 and X5 (Figure 5b). Notably, doxorubicin exhibits a significant increase in RMSD after 15 ns, jumping from 3 Å to 7.5-9 Å, suggesting that the doxorubicin complex is less stable compared to the C62, xanthones X1-X3, and X5. The stability of doxorubicin declines markedly after 15 ns. In contrast. the RMSD values for C62 show several significant increases. at 7, 17, and 32 ns, whereas such fluctuations are not observed for the X1-X3 and X5 xanthone derivatives. Among these, the X3 compound displays the lowest RMSD values, consistently 2 Å, making it the most stable ligand complex in this study.

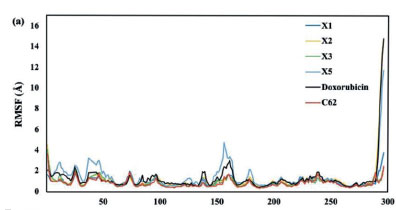

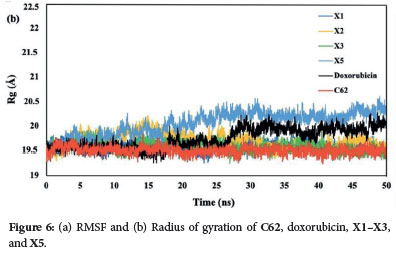

The Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) quantifies the divergence of atomic positions from their initial coordinates, serving to verify the accuracy of the radius of gyration (Rg) measurements and detect local alterations in protein chain residues resulting from ligand binding. The RMSF readings indicate that the backbone system's fluctuations correlate with RMSD values. Peaks with high RMSF values during the simulation denote significant fluctuations, suggesting less stable ligand-protein interactions for values greater than 2.5 Å. Among the xanthone derivatives, the X5 compound exhibits the most points with RMSF values exceeding 2.5 Å (3.0, 3.5, and 4.5 Å), followed by doxorubicin. In contrast. the native ligand (C62), X1, X2, and X3 all maintain RMSF values below 2.5 Å (Figure 6a). Notably, the X3 compound achieves the lowest RMSF values, consistent with its RMSD results. underscoring its superior stability as a ligand complex. This finding is supported by the radius of gyration (Rg) measurements, where the X3 compound consistently shows a stable value of 19.6 Å (Figure 6b). In contrast, the X5 compound exhibits the most fluctuating Rg values. It indicates that the protein tends to be highly compact and difficult to fold. These observations further reinforce the stability of the X3 compound compared to the other xanthone derivatives.

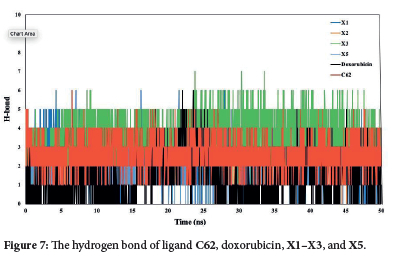

The total and intramolecular hydrogen bonds were analyzed from the simulated trajectories (Figure 7). The X3 compound exhibited the highest average number of hydrogen bonds compared to doxorubicin and ligand C62. Notably. the average intramolecular hydrogen bonds for the X3 compound remained constant over 50 ns, indicating stable interactions. In contrast, Doxorubicin showed a significant increase in the average number of hydrogen bonds between 15-25 ns, reflecting more variable binding dynamics. These results highlight the superior and consistent binding stability of the X3 compound. The combined results of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and molecular docking studies support the stability of the studied complexes under physiological conditions.18 These findings confirm that the X3 compounds are credible CDK2 inhibitors.

The binding energies were computed utilizing the MM-PBSA methodology. The van der Waals, electrostatic, polar solvation, SASA, and binding energy were calculated for the last 30 nanoseconds of the molecular dynamics (MD) trajectory. According to the data presented in Table 2, chemical X3 had the lowest binding energy (-51.35 kJ/mol), indicating the most stable association with the CDK2 protein.

Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Xanthone Derivatives against EGFR Protein

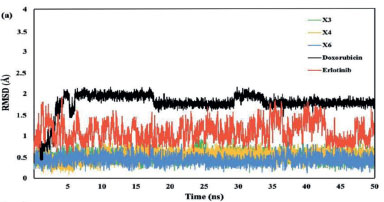

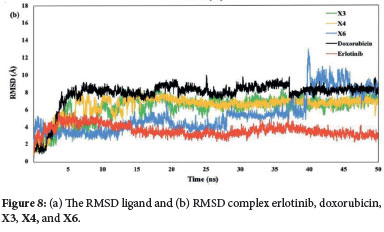

The native ligand erlotinib, doxorubicin, and several xanthone derivatives (X1-X6) were studied for their interactions with the EGFR protein through a molecular docking study. Among the xanthone derivatives, compounds X3, X4, and X6 were selected for further molecular dynamics simulation due to their lower binding energies. Compounds X3, X4, and X6 were selected for further molecular dynamics simulation due to their lower binding energies among the xanthone derivatives. Figure 8a demonstrates that the root mean square deviation (RMSD) of all ligands falls within the range of 0.5 to 2 Å. The results demonstrated that the ligands were stationary within the protein's active area, suggesting that they consistently interacted with the active site over the whole 50 ns simulation.

The RMSD complex revealed that compounds X3 and X4 exhibited greater stability compared to X6 (Figure 8b). Specifically, X6 showed a gradual increase in RMSD after 25 ns, with a significant rise after 40 ns. Meanwhile, after 5 ns, compounds X3 and X4 had a consistent RMSD value during the rest of the simulation time. Although the RMSD values for X3, X4, and X6 were lower than those for doxorubicin, they were higher than those for erlotinib.

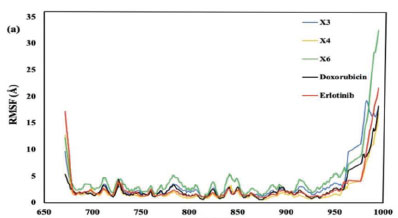

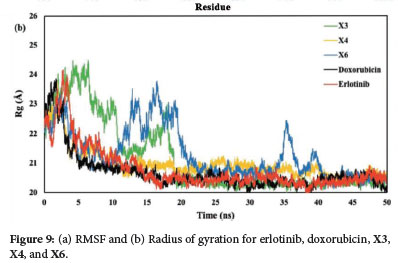

The RMSF graph presented in Figure 9a, indicates the stability of ligand-protein interactions with less stable bonds characterized by RMSF values greater than 2.5 Å. Erlotinib, doxorubicin, and the xanthone derivatives X3, X4, and X6 all exhibited RMSF values exceeding this threshold. Despite these high RMSF values, the xanthone derivatives showed a comparable pattern of amino acid fluctuations to both erlotinib and doxorubicin. This suggests that the binding interactions of the compounds with the EGFR protein were similar Furthermore, the X4 compound complexes demonstrated the most consistent radius of gyration (Rg) values, mirroring the patterns observed with the native ligand erlotinib and doxorubicin (Figure 9b). This consistency indicates that X4 maintained stable interactions within the protein's active site, reinforcing the idea that its binding interactions were similar to those of the native ligand and doxorubicin.

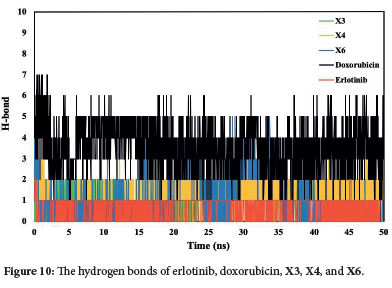

The total and intramolecular hydrogen bond analysis from the simulated trajectories (Figure 10) revealed distinct interaction patterns. The doxorubicin demonstrated the highest average number of hydrogen bonds compared to the other tested ligands, including erlotinib, X3, X4, and X6 compounds. The intramolecular hydrogen bonds for the X3 and X4 compounds remained stable over the entire 50-ns simulation period, indicating strong and consistent interactions. In contrast, the X6 compound fluctuated the number of hydrogen bonds. Suggesting less stable binding dynamics. These findings underscore the robust binding stability of the X4 compound. The integration of molecular dynamics simulations and molecular docking results confirms the reliability of the X4 compound as an effective EGFR inhibitor under physiological conditions.

The binding energy of the MM-PBSA was calculated during the last 30 nanoseconds. As presented in Table 3, Xanthones X3 (-57.96 kJ/ mol), X4 (-72.14 kJ/mol), and X5 (-58.24 kJ/mol) exhibited lower binding energies than erlotinib (-36.05 kJ/mol), suggesting a more stable interaction between the xanthones and the EGFR protein.

Pharmacokinetic Properties of Xanthone Derivatives

The ADMET and physicochemical results of xanthone derivatives were retrieved from the pkCSM website. The physicochemical of the drug candidate should have the following characteristics molecular weight <500 daltons, the logarithm of the octanol-water partition coefficient (log P) <5, rotatable bonds (ROTB) <10, hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA) <10, hydrogen bond donor (HBD) <5, and polar surface area (PSA) <140 Å according to Lipinski's rule of five.45 Only compounds X5 and X6 do not fulfill the H-bond donor parameters (Table 4).

An ADMET research evaluates the pharmacokinetics of a drug, particularly when examining the possible toxicity, metabolism, distribution, absorption, and excretion of small-molecule medicines (Table 4). The Caco-2 is commonly used as an in vitro model of the human mucosa to predict the absorption of oral medications in the absorption parameter. A drug is considered to have high Caco-2 permeability if its readings exceed 0.90. Compound X4 and X6 exhibit Caco-2 permeability values above the optimum threshold. The Intestinal Absorption (lA) parameter estimates the fraction of a drug absorbed by the human intestines. An absorption rate of 80% is deemed favorable, whereas a rate below 30% is regarded as unfavorable. All xanthones meet those criteria, indicating that they are easily absorbed.

The volume distribution (VDss) refers to the overall amount of a drug in the body and is characterized by a low value (log VDss < -0.15).46 All compounds exhibit a lower log VDss value than -0.15, indicating that all ligand has poor volume distribution. The quantification of blood-brain barrier permeability elucidates how much drug can pass across the barrier. It has been found that molecules with a logBB value more than 0.3 are readily taken up by the brain, but those with a logBB value less than -1 are not equally distributed inside it. The blood-brain permeability-surface area product (logPS), also known as CNS permeability, is an additional method used to measure the permeability of the blood-brain barrier. None of the xanthone derivatives can pass the blood-brain barrier and reach the central nervous system.

Compounds X3, X4, and X6 were shown to be unsuitable as substrates for CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 enzymes based on their metabolic properties. Nevertheless, none of the ligands exhibit inhibitory activity against these substrates. The metabolism of cytochrome P450 is contingent upon the presence of these two substrates. Cytochrome P450, the crucial enzyme responsible for detoxification in the human body, is predominantly located in the liver. Subsequently, the excretion data indicated that while none of the xanthones exceeded the Renal Organic Cation Transporter 2 (OCT2) requirement, their total clearance values varied between 0.269 and 0.391.

The toxicity characteristics indicated that all derivatives of xanthones possess mutagenic potential. The maximum recommended tolerated dose (MRTD) is the highest dosage limit of a hazardous substance that humans may safely tolerate. The MRTD value was high for all substances. Potassium channel blockage by hERG expression is a prominent factor in the development of long QT syndrome, resulting in cardiac arrhythmia and potential fatality. None of the compounds had any inhibitory effect on hERG I. Drug-induced liver damage is a significant cause of drug attrition and a critical safety problem in the development of new therapies. Consequently, there is a correlation between hepatoxicity and liver damage, and the liver did not exhibit any deviation from the predicted values for any chemical. Furthermore, the expected skin sensitivity could be enhanced. None of the xanthones exhibits any impact on hepatoxicity or skin.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, our comprehensive study utilizing molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations, binding energy calculation with the MM-PBSA method, and ADMET properties identified xanthones X3 and X4 as highly effective and stable ligands with significant inhibitory activity against both CDK2 and EGFR proteins. The xanthone derivatives, particularly X3 and X4, demonstrated superior stability compared to doxorubicin, underscoring their potential as therapeutic agents. These findings support the credibility of compounds X3 and X4 as promising candidates for further development in treating cancers involving CDK2 and EGFR dysregulation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

LPH, SE, and KML thank Riset Data Pustaka dan Daring no 2183/ UN6.3.1/PT.00/2024 from Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung, Indonesia.

CREDIT AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION STATEMENT

Conceptualization: LPH, FH; Methodology: LPH, FH, TE; Software: EY; Validation: LPH, TE; Formal analysis: LPH, LAM; Investigation: FH, TE, LAM, NRP, SE; Data curation: NRP, EY, SE; Resources: KML; Visualization: LAM, NRP; Writing - original draft: LPH; Writing -review & editing: LPH, FH, TE, LAM, NRP, EY, SE, KML; Supervision: KML; Project administration: LPH; Funding acquisition: LPH.

DECLARATION OF COMPETING OR FINANCIAL INTERESTS

LPH, FH, TE, LAM, NRP, EY, SE, and KML declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this manuscript.

ORCID IDS

Lathifah Puji Hastuti: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4976-4218

Faris Hermawan: https://orcid.org/0009-0006-6923-4050

Teni Ernawati: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2235-8591

Lala Adetia Marlina: https://orcid.org/0009-0000-9313-9850

Nicky Rahmana Putra: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4886-496X

Ervan Yudha: https://orcid.org/0009-0004-6955-4885

Savira Ekawardhani: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8904-7811

Kevin Muhamad Lukman: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1863-2965

REFERENCES

1. Mirowski M. Drug development. Chem Eng News. 2002;80(23):9. [ Links ]

2. Wang JYJ. Cell death response to dna damage. Yale J Biol Med. 2019;92(4):771-779. [ Links ]

3. Hashem S, Ali TA, Akhtar S, Nisar S, Sageena G, Ali S, Al-Mannai S, Therachiyil L, Mir R, Elfaki I, et al. Targeting cancer signaling pathways by natural products: exploring promising anti-cancer agents. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;150:113054. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113054. [ Links ]

4. Hanusova V, Skalova L, Kralova V, Matouskova P. Potential anti-cancer drugs commonly used for other indications. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2015;15(1):35-52. https://doi.org/10.2174/1568009615666141229152812. [ Links ]

5. Banerjee S, Nau S, Hochwald SN, Xie H, Zhang J. Anticancer properties and mechanisms of botanical derivatives. Phytomed Plus. 2023;3(1):100396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phyplu.2022.100396. [ Links ]

6. Çankaya N, Yalçin S. Antiproliferative activity and interaction with proteins of. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2022;29(11):101670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.04.030. [ Links ]

7. Shi XN, Li H, Yao H, Liu X, Li L, Leung KS, Kung H-F, Lin MC-M. eKung HF, Lin MCM. Adapalene inhibits the activity of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 in colorectal carcinoma. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12(5):6501-6508. https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2015.4310. [ Links ]

8. Wood DJ, Korolchuk S, Tatum NJ, Wang LZ, Endicott JA, Noble MEM, Martin MP. Differences in the conformational energy landscape of CDK1 and CDK2 suggest a mechanism for achieving selective CDK inhibition. Cell Chem Biol. 2019;26(1):121-130.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chembiol.2018.10.015. [ Links ]

9. Miladiyah I, Jumina J, Haryana SM, Mustofa M. Biological activity, quantitative structure-activity relationship analysis, and molecular docking of xanthone derivatives as anticancer drugs. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2018;12:149-158. https://doi.org/10.2147/DDDT.S149973. [ Links ]

10. Yuliana A, Rahmiyani I, Kartika C. Molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation using Monascus sp. as a candidate cervical cancer drug. J Trop Pharm Chem. 2023;7(1):41-51. https://doi.org/10.25026/jtpc.v7i1.432. [ Links ]

11. Kamal MA, Baeissa HM, Hakeem IJ, Alazragi RS, Hazzazi MS, Bakhsh T, Aslam A, Refaat B, Khidir EB, Alkhenaizi KJ, et al. Insights from the molecular docking analysis of EGFR antagonists. Bioinformation. 2023;19(3):260-265. https://doi.org/10.6026/97320630019260. [ Links ]

12. Rampogu S, Lee G, Park JS, Lee KW, Kim MO. Molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations discover curcumin analogue as a plausible dual inhibitor for SARS-CoV-2. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(3):1771. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23031771. [ Links ]

13. Pirintsos S, Panagiotopoulos A, Bariotakis M, Daskalakis V, Lionis C, Sourvinos G, Karakasiliotis I, Kampa M, Castanas E. From Traditional ethnopharmacology to modern natural drug discovery: a methodology discussion and specific examples. Molecules. 2022;27(13):4060. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27134060. [ Links ]

14. Chunarkar-Patil P, Kaleem M, Mishra R, Ray S, Ahmad A, Verma D, Bhayye S, Dubey R, Singh H, Kumar S. Anticancer drug discovery based on natural products: from computational approaches to clinical studies. Biomedicines. 2024;12(1):201. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12010201. [ Links ]

15. Hermawan F, Jumina J, Pranowo HD, Sholikhah EN, Ernawati T, Azminah A. In silico approach for design, synthesis and biological evaluation of tioxanthone derivatives as potential anticancer agents. ChemistrySelect. 2024;9(6):e202304014. https://doi.org/10.1002/slct.202304014. [ Links ]

16. Pires DEV, Blundell TL, Ascher DB. pkCSM: predicting small-molecule pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties using graph-based signatures. J Med Chem. 2015;58(9):4066-4072. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00104. [ Links ]

17. Bukowski K, Kciuk M, Kontek R. Mechanisms of multidrug resistance in cancer chemotherapy1. Bukowski K, Kciuk M, Kontek R. Mechanisms of multidrug resistance in cancer chemotherapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(9):3233. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21093233. [ Links ]

18. Belkadi A, Kenouche S, Melkemi N, Daoud I, Djebaili R. Molecular docking/dynamic simulations, MEP, ADME-TOX-based analysis of xanthone derivatives as CHK1 inhibitors. Struct Chem. 2022;33(3):833-858. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11224-022-01898-z. [ Links ]

19. Hermawan F, Jumina J, Pranowo HD, Sholikhah EN, Iresha MR. Computational design of thioxanthone derivatives as potential antimalarial agents through Plasmodium falciparum protein inhibition. Indones J Chem. 2021;22(1):263-271. https://doi.org/10.22146/ijc.69448. [ Links ]

20. Mahmud S, Rahman E, Nain Z, Billah M, Karmakar S, Mohanto SC, Paul GK, Amin A, Acharjee UK, Saleh MA. al Amin, Acharjee UK, Saleh Ma. Computational discovery of plant-based inhibitors against human carbonic anhydrase IX and molecular dynamics simulation. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2021;39(8):2754-2770. https://doi.org/10.1080/07391102.2020.1753579. [ Links ]

21. Santos CMM, Freitas M, Fernandes E. A comprehensive review on xanthone derivatives as a-glucosidase inhibitors. Eur J Med Chem. 2018;157:1460-1479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.07.073. [ Links ]

22. Hastuti LP, Hermawan F, Iresha MR, Ernawati T, Firdayani. Firdayani. In-silico studies of hydroxyxanthone derivatives as potential pfDHFR and pfDHODH inhibitor by molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulation, MM-PBSA calculation and pharmacokinetics prediction. Inform Med Unlocked. 2024;47(4):101485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imu.2024.101485. [ Links ]

23. Gohain BB, Gogoi U, Das A, Rajkhowa S. Enhancing cancer drug development with xanthone derivatives: A QSAR approach and comparative molecular docking investigations. S Afr J Bot. 2023;163:294-310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2023.10.031. [ Links ]

24. Roy S, Maiti B, Banerjee N, Kaulage MH, Muniyappa K, Chatterjee S, Bhattacharya S. New xanthone derivatives as potent g-quadruplex binders for developing anti-cancer therapeutics. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2023;6(4):546-566. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsptsci.2c00205. [ Links ]

25. Aye A, Song YJ, Jeon YD, Jin JS. Xanthone suppresses allergic contact dermatitis in vitro and in vivo. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;78:106061. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2019.106061. [ Links ]

26. Tang YX, Fu WW, Wu R, Tan HS, Shen ZW, Xu HX. Bioassay-guided isolation of prenylated xanthone derivatives from the leaves of Garcinia oligantha. J Nat Prod. 2016;79(7):1752-1761. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jnatprod.6b00137. [ Links ]

27. Huang Z, Yang R, Guo Z, She Z, Lin Y. A new xanthone derivative from mangrove endophytic fungus No. ZSU-H16. Chem Nat Compd. 2010;46(3):348-351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10600-010-9614-5. [ Links ]

28. Fatmasari N, Kurniawan YS, Jumina J, Anwar C, Priastomo Y, Pranowo HD, Zulkarnain AK, Sholikhah EN. Synthesis and in vitro assay of hydroxyxanthones as antioxidant and anticancer agents. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):1535. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-05573-5. [ Links ]

29. Poornima P, Kumar JD, Zhao Q, Blunder M, Efferth T. Network pharmacology of cancer: from understanding of complex interactomes to the design of multi-target specific therapeutics from nature. Pharmacol Res. 2016;111:290-302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2016.06.018. [ Links ]

30. Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. UCSF Chimera - A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25(13):1605-1612. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.20084. [ Links ]

31. Hanwell MD, Curtis DE, Lonie DC, Vandermeersch T, Zurek E, Hutchison GR. Avogadro: an advanced semantic chemical editor, visualization, and analysis platform. J Cheminform. 2012;4:17. https://doi.org/10.1186/1758-2946-4-17. [ Links ]

32. Neese F. Software update: the ORCA program system, version 4.0. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Comput Mol Sci. 2018;8(1):e1327. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcms.1327. [ Links ]

33. Xu X, Goddard WA 3rd. The X3LYP extended density functional for accurate descriptions of nonbond interactions, spin states, and thermochemical properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(9):2673-2677. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0308730100. [ Links ]

34. Yuriev E, Agostino M, Ramsland PA. Challenges and advances in computational docking: 2009 in review. J Mol Recognit. 2011;24(2):149-164. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmr.1077. [ Links ]

35. Mukesh B, Rakesh K. Molecular docking: a review. Int J Res Ayurveda Pharm. 2011;2(6):1746-1751. [ Links ]

36. BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer. Dassault Systèmes, San Diego, USA; 2019. https://discover.3ds.com/discovery-studio-visualizer-download [ Links ]

37. Balogun TA, Ipinloju N, Abdullateef OT, Moses SI, Omoboyowa DA, James AC, Saibu OA, Akinyemi WF, Oni EA. Computational evaluation of bioactive compounds from Colocasia affinis Schott as a novel EGFR inhibitor for cancer treatment. Cancer Inform. 2021;20:11769351211049244. https://doi.org/10.1177/11769351211049244. [ Links ]

38. Moreau Bachelard C, Coquan E, du Rusquec P, Paoletti X, Le Tourneau C. Risks and benefits of anticancer drugs in advanced cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;40:101130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101130. [ Links ]

39. Abraham MJ, Murtola T, Schulz R, Páll S, Smith JC, Hess B, Lindahl E. Gromacs: high performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX. 2015;1-2:19-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.softx.2015.06.001. [ Links ]

40. Pronk S, Páll S, Schulz R, Larsson P, Bjelkmar P, Apostolov R, Shirts MR, Smith JC, Kasson PM, van der Spoel D, et al. GROMACS 4.5: A high-throughput and highly parallel open source molecular simulation toolkit. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(7):845-854. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btt055. [ Links ]

41. Verlet L. Comyuter "Exyeriments" on Classical Fluids. I. Thermodynamical Properties of Lennard, -Jones Molecules-. Phisical Rev. 1967;159(1):159. [ Links ]

42. Wu CP, Hsiao SH, Murakami M, Lu YJ, Li YQ, Huang YH, Hung T-H, Ambudkar SV, Wu Y-S. Alpha-mangostin reverses multidrug resistance by attenuating the function of the multidrug resistance-linked ABCG2 transporter. Mol Pharm. 2017;14(8):2805-2814. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.7b00334. [ Links ]

43. Jun LY, Mubarak NM, Yee MJ, Yon LS, Bing CH, Khalid M, Abdullah EC. An overview of functionalised carbon nanomaterial for organic pollutant removal. J Ind Eng Chem. 2018;67:175-186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiec.2018.06.028. [ Links ]

44. Feroz Khan F, Alam S. QSAR and docking studies on xanthone derivatives for anticancer activity targeting DNA topoisomerase IIα. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2014;8:183-195. https://doi.org/10.2147/DDDT.S51577. [ Links ]

45. Lipinski CA. Lead- and drug-like compounds: the rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discov Today Technol. 2004;1(4):337-341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ddtec.2004.11.007. [ Links ]

46. Ramírez D, Caballero J. Is it reliable to take the molecular docking top scoring position as the best solution without considering available structural data? Molecules. 2018;23(5):1038. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23051038. [ Links ]

Received 30 November 2024

Revised 10 February 2025

Accepted 19 May 2025

* To whom correspondence should be addressed Email: iathifah.puji@unpad.ac.id