Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Kronos

On-line version ISSN 2309-9585Print version ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.33 n.1 Cape Town 2007

ARTICLES

Power, Secrecy, Proximity: A Short History of South African Photography

Patricia Hayes

History Department, University of the Western Cape

I. Power

A tremendous shattering of tradition (Walter Benjamin)

The sea brought photography to South Africa and the rest of the African coastline in the wake of ninteenth century merchant and colonial empires. The daguerreotype traveled quickly across this liquid frontier to Brazil and India, and reached Durban via the island of Mauritius in September 1846.1

It is fitting, perhaps, that this maritime space should bring a new way of looking, for the mercantile exchanges it carried had also contributed to the industrial revolution and ensuing mechanical possibilities that led to the camera. Allan Seku-la's Fish Story speaks of the sea and its excess, bringing different ways of imagining to-and-fro, tied in with different knowledges that changed with capitalism and the mechanization of making pictures.2

Few people had access to the camera when it first arrived on the subcontinent with Jules Léger at Algoa Bay on the schooner Hannah Codner. Very soon Léger exhibited a handful of settler portraits and some colonial scenes, all described in the Grahamstown Journal in November 1846 as 'beautiful, wonderful, interesting'. His associate, William Ring, moved to Cape Town with the equipment, but was less successful. However, by 1851 three daguerrotypists of note, Carel Sparmann, William Waller and John Paul, were doing good business. The adoption of the wet plate ensured that photography in South Africa expanded. The studios of S.B. Barnard and F.A.Y. York were the most renowned. They were charged with public commissions and there were many notables among their clientele. York photographed the Governor Sir George Grey's last public act in the Cape, the laying of a foundation stone at the Somerset hospital in 1857. He also photographed the building of the Breakwater and prison nearby at the waterfront docks.3

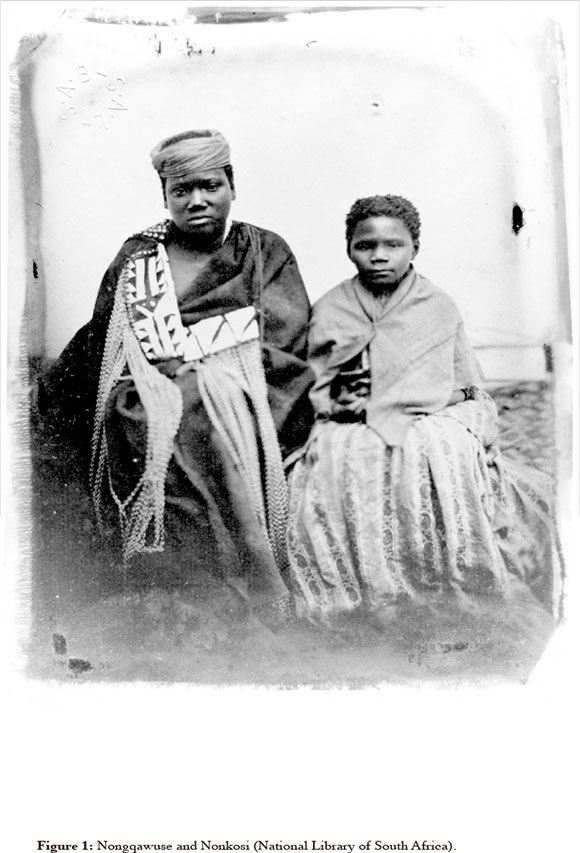

The thought of Sir George Grey and the Breakwater prison brings to mind another kind of photography. This arises from the establishment of colonial government, and control over the indigenous people of South Africa. Grey is most notorious for his role in the destruction of the Xhosa chiefdoms in the wake of the cattle-killing of 1856-7 in the Eastern Cape. A famous image resulting from the cattle-killing episode is that of the prophetess, Nongqawuse, and the young Non-kosi, taken in 1858. The young women were taken captive and dressed haphazardly before being put before a camera in King William's Town. Nongqawuse's spiritual aura is strangely translated by the same camera Walter Benjamin later accused of 'eliminating' aura.4 According to Benjamin, writing in the shadow of fascism and mass culture in 1930s Germany, photography has two propensities: firstly it makes a plurality of copies out of one unique existence, and secondly it reactivates the object reproduced. This all leads to 'a tremendous shattering of tradition'.5 It is provocative to transpose the argument to the African continent and its photographic archive. We must acknowledge that 'tradition' was being shattered in almost every other way. Because of emerging colonial photographic rituals marking subjugation and power however, and the British culture of documentation that put emphasis on archives, we also have the birth of a new tradition. Against a background of so much other loss, we cannot know what re-assemblies of 'tradition' might occur as Nongqawuse's haunting replica comes out of the filing cabinet.

This was by no means the only photographic capture. John Tagg has argued that the history of photography 'has no unity. It is a flickering across a field of institutional spaces'.6 As such, photography should not be studied in isolation. In southern Africa in the late nineteenth century, photography is related to the history of exploration, colonization, knowledge production and captivity. David Livingstone, who had his portrait taken in Cape Town in 1852 before setting out on his travels, took a photographer with him on his travels. William Chapman's later stereoscopic photographs in South West Africa were more successful, and the naval photographer Hodgson produced excellent photographs when he accompanied Palgrave on his 1876 Herero mission for the Cape Government.

In a nexus of which the prison was part, an important body of photographs of /Xam bushmen was generated in 1871. These men were taken out of the Breakwater prison for purposes of linguistic study by Wilhelm Bleek and Lucy Lloyd. When they were photographed at the prison, Professor Huxley's anthropometric guidelines were followed.7 This was a rather different proposition from Mikhael Subotzky's recent work in Pollsmoor prison in Cape Town, with very different relationships involved. Subotzky justified his prison subject matter by pointing out that so many people's lives are affected by it.8 This is true now, and was then. Indeed there is a long and complicated tradition of prison photography in South Africa. One further example will suffice for the nineteenth century: Gustav Frit-sch's portraits of African leaders held on Robben Island.9 It seems that as political captives filtered to Robben Island prison or exile elsewhere, they were also filtered by the camera.

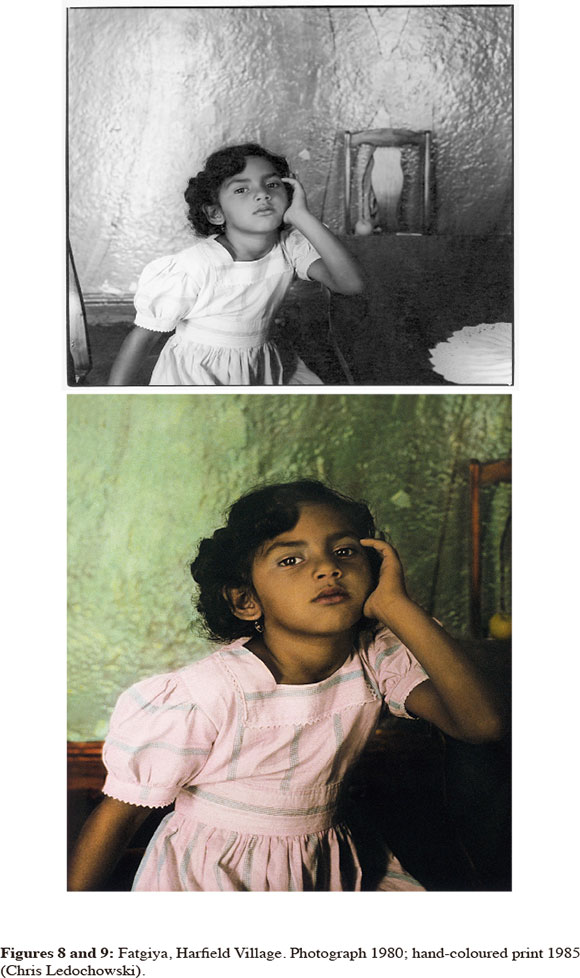

The colonial moment does not seal off more ambiguous or alternative readings of these older images. Some 'portraits' have a kind of double effect: many viewers today find them honorific, and then realize they were repressive.10 But they can flicker back as well, as the personal force or dignity shines through the prison or anthropometric backdrop. Michael Aird's work with Aboriginal photographs in Australia suggests that often it does not matter, families will come and seek them out in the museum.11 In South Africa as well, people have enlarged and hand-coloured identity photographs of older relatives into remarkable family portraits. The plasticity of the medium allows this.

It was not simply the white elite who sought their portraits in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Santu Mofokeng's project on the 'Black Photo Album' delves into remnants of family photographs in Soweto. Indian 'passenger' immigrants brought the practice with them to Natal, and doubtless many city and small town studios attest to the old existence of black archives.12 From 1937, for example, the Van Kalker Studio in Woodstock, Cape Town, photographed generations of families who, even after apartheid's forced removals in the 1960s, made their way back along a visual seam to the studio to continue the tradition.

Photography was thus embedded widely in South Africa, as it went from war to Union in 1910. One of the most remarkable photographers to emerge in a new nexus of mining, labour, ethnography and aesthetics was Alfred Duggan-Cronin. He moved from extraordinary figural and ethnographic studies on the Kimberley diamond mines, to field visits where he photographed the historic sites from which the arteries of migrant labour originated.

Pictorialism was by this time very popular, reflecting European trends, with regular salons established from 1906.13 These showed little awareness of the growing urban presence of black South Africans. Two accomplished modernist photographers who engaged in growing corporate and industrial commissions, as well as ethnographic and (perhaps) early documentary photography, were Constance Larrabee and Leon Levson.14 Social anthropologist Ellen Hellmann also used photography in her study of African families living in the city.15 Even more important to documentary and early 'resistance' photography was Eli Weinberg.16 But a platform emerged in the 1950s which allowed for the new and dynamic expression of a cohort of black photographers.

II. Secrecy

How dare you try to do this and keep it a secret ... (Eric Miller, Afrapix)

Drum magazine launched a generation of talented black writers and photographers. The latter included Alf Khumalo, Bob Gosani, Ernest Cole and Peter Magubane, with German immigrant photographer Jürgen Schadeburg an important stylistic influence. In their representation of popular urban life, they portrayed worlds that were extraordinarily animated, vivid and ineluctably modern. The magazine in toto set the tone for glamour, desire and consumerism. Its major talent belonged to this Drum decade of the 1950s, but the photographers continued with more serious assignments and projects into the 1960s and beyond. Bob Gosani secretly photographed the notorious prison practice of tauza, for instance, while Ernest Cole portrayed nude body inspections of migrant workers.

Without doubt, the most sustained and remarkable body of documentary work amongst this generation was Ernest Cole's House of Bondage, published abroad after the photographer 'exiled himself'.17 As the title suggests, it ripped open the belly of the apartheid beast by making visible the multifaceted challenges people confronted in their daily lives. Peter Magubane followed with much courageous photojournalist work before and after the 1976 Soweto student uprising and state crackdown, until he too was obliged to work abroad.18 Both Sharpeville and Soweto resulted in the banning of political activity and organization, which made committed photojournalism a dangerous undertaking. The world famous photograph of Hector Peterson, the first victim of the Soweto shootings on 16 June 1976, effectively ended the working career of the photographer, Sam Nzima.

The Hector Peterson image became iconic, and it is relevant to the rest of this essay to ask why. Nzima's picture has often been compared to the Pièta. A very strong theme which emerges in South African photographic icons of the apartheid era is an ostensibly Christian one, involving martyrdom and the suffering of the innocents. The appetite of the west for similar images during the 1980s, discussed below, shows how profoundly and reductively the impact persisted globally.

On a different trajectory through the 1970s, and working professionally on various magazines and corporate assignments, David Goldblatt began publishing his own powerful thematics in On the Mines (1973), Some Afrikaners Photographed (1975), and In Boksberg (1982). This was the beginning of an immensely influential and nuanced oeuvre that continues to expand and shape the visual understandings of a changing South Africa today. His preoccupations over time include the impact of mining, the class and race fragilities of whiteness, the generic nature of South African modernization, built structures and their human inscriptions, and landscapes with their historical inscriptions. Goldblatt acted as mentor to many younger photographers, and by his insistence on photographic rigour and coherence of theme, he both nurtured and debated with the overtly politicized generation of the 1980s.

A key figure in the emergence of this 1980s generation was Omar Badsha, an artist, activist and trade unionist in Durban. Badsha started out using photography as an educational tool in the trade unions, but increasingly used it to record a 'visual diary' of the social and political worlds in which he moved. The Leica enabled a loose, accessible style that allowed Badsha to explore the ghettoes in full movement, both urban and rural.19 These were the micro-worlds hidden by apartheid: people lodged in the cracks produced by the contradictions of capitalist growth, the 'scars of modernity'.20 His observation of the dynamics of political, cultural and religious leadership also constitute an enduring theme concerning 'the leaders and the led' up to the early 1990s.

Together with Paul Weinberg, Lesley Lawson, Cedric Nunn and Peter Mackenzie, Badsha co-founded the progressive photographic collective and agency, Afrapix, in 1982. This followed the highly charged photographic and political debates at the Festival of Culture and Resistance held in Botswana. These photographers were already immersed in political, educational and trade union work - a new set of institutional spaces for photography. Cedric Nunn points to the fact that the 'documentary project' emerged before the big mobilizations of the mid-1980s: 'you consolidate culture, and you develop resistance. And so when the resistance began then we began documenting that as well. But we actually predated the re-sistance.'21 Lesley Lawson also worked from the very early 1980s in worker and alternative education, developing a focus on women: '[W]hat I was interested in really was ordinary people's lives... it was political because of the nature of South Africa, and because ordinary people's lives were so embattled. And also at the same time, in that period, so heroic, in a way'.22

Such photography was inserted into diverse institutional fields and uses, such as worker and alternative education, and community activism. But the visual economy was expanding. From the mid-1980s, as South African images received heightened global attention, full-time professional photography became viable. The landscape was changing; South Africa became 'the land of the violence'. Nunn comments: 'We started out as activists. ironically, what happened is that the more successful we [Afrapix] became, the more people we attracted. . And it was quite a sexy way to make a career for yourself, you know'.23

Afrapix was formed in 1982, and the United Democratic Front was launched in 1985. This constituted a large front for trade union, student, church, youth, women's and civic organizations. In a sense Afrapix replicated some of the organizational dynamics it was photographing in the mass democratic movement, though unlike many others they sought to generate their own income. The full cohort of Afrapix photographers by the mid-1980s included Steve Hilton-Barber, Guy Tillim, Chris Ledochowski, Rashid Lombard, Paul Alberts, Joseph Alphers, Ben Maclennan, Santu Mofokeng, Pax Magwaza, Jeeva Rajgopaul, Rafs Mayet, Paul Grendon, Anna Zieminski, Gille de Vlieg, Eric Miller, Deseni Moodliar, Zu-beida Vali and numerous others. The predominant themes in the photography were forced removals, marches, meetings, rallies and later, of course, funerals. Mobilisation and repression loomed large as issues, but so did the contradictory social conditions under apartheid. This included in-depth work such as Paul Weinberg's study of the effects of militarization on bushmen in illegally-occupied Namibia. An excellent sense of the range of documentary at the time is conveyed in the publication for the Second Carnegie Commission Inquiry into poverty and development, The Cordoned Heart (1986). This was followed by a second Afrapix publication, Beyond the Barricades (1989).24

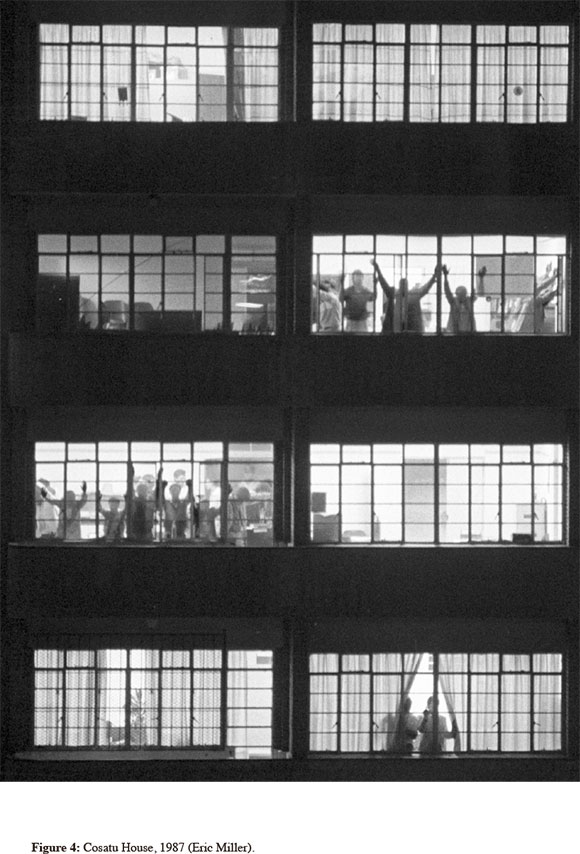

One of the priorities for photographers was of course exposure, pure and simple. A good example is Eric Miller's photograph of Cosatu House in Beyond the Barricades. It concerns the police occupation of the headquarters of the largest labour organization in the country, in Johannesburg in 1987. Miller recalled being fuelled by anger. 'It's partly this, **** you people! How dare you do this shit and then try and keep it a secret sort of thing.' He entered the building on the opposite side of the road as police were searching, arresting and assaulting Cosatu officials. From his window several floors up, he took this picture.

Miller recalled: 'I remember watching it for a few minutes before I took pictures. ... I just remember this surreal thing, watching from across the road, and watching them go from office to office, ... you could see the whole building from this side ... And it was just a very surreal.. ..as was a lot of the stuff that was happening.'25 Miller's testimony is suggestive because there is more to documentary, and the big documentary decade, than has hitherto been acknowledged. Miller's own obsession was with exposing secrecy and lies, as was the case with many photographers. The mechanism of that state control was the censorship operated by the Emergency Regulations. There were moments when Afrapix photographers found openings which they fully exploited. But this photograph also raises questions about the scale of events, and the tension between visibility and invisibility.

This is a very dense, modernist photograph about multiple surveillances and the dynamics around seeing, all closed in a circuit. The two figures half-concealed by the curtains drawn slightly open, cautiously looking out as if to find out what is happening above, seem to want vision but do not want to be visible. It is a code for the power problem here, the enactment of domination and surrender - all exposed against an industrial grid of architecture, in a series of frames replicating the action of the shutter. The photograph presents a series of cell-like structural vignettes that offer a series of statements about the relations between antagonists in the political struggle, including the photographer who left the scene when spotted by the policemen (Figure 4).

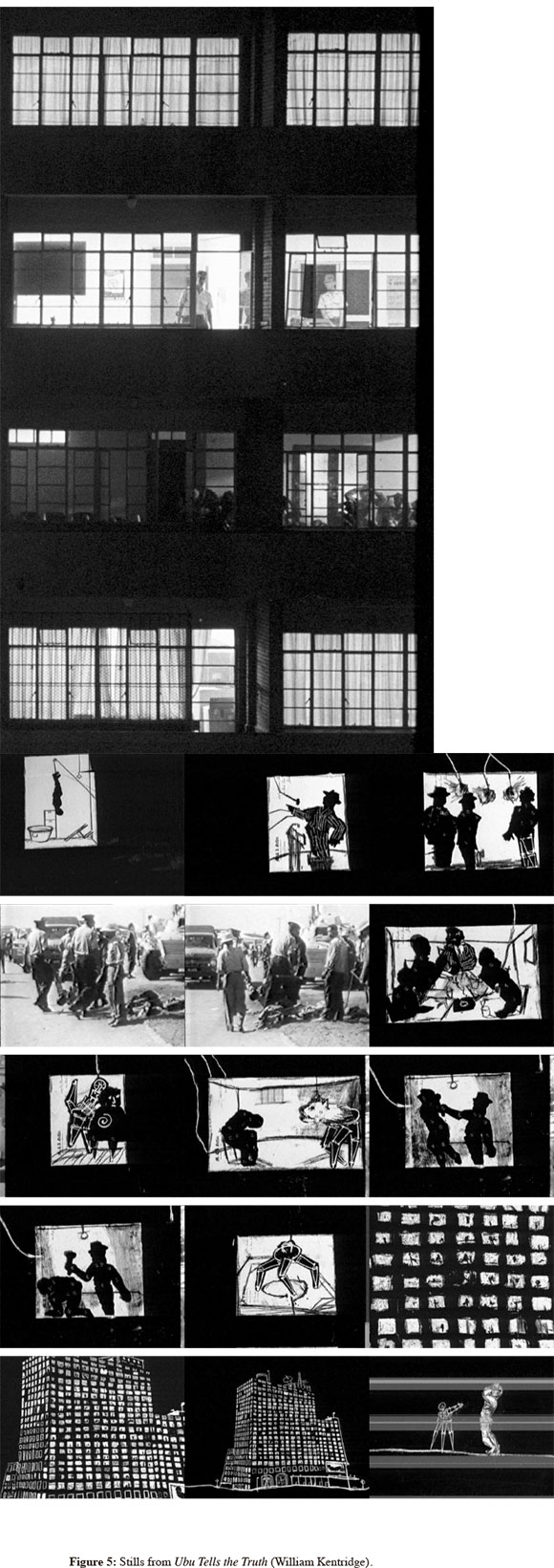

The photograph resembles a contact sheet; it has the look of a film-strip before editing. This openness is a rawness, producing what Elizabeth Edwards calls 'the first transcript of history'.26 There is the history of photography, but there is also the photography of history. I think that this is where 'documentary' has been underestimated. For the history it produces has immeasurable influences, and inter-ocular effects that enter the art world, among other things. As South African photography now enters the art galleries in a serious way, we should remember it is not the first or the last presence of photography. It is intriguing to consider how William Kentridge, for example, 'indirectly' incorporates elements of seen photographs in Ubu Tells the Truth, his own artistic re-enactment of the disempower-ments of apartheid.27

III. Proximity

[D]ominant social relations are inevitably both reproduced and reinforced in the act of imaging those who do not have access to the means of representation themselves (Solomon-Godeau).28

A complex chain of events was taking place in the photographic economy. Vi-suality works in reciprocal ways. It is 'not merely a by-product of social reality but actively constitutive of it.'29 Badsha commented at the time: 'We are ... in competition with the multi-national news and feature agencies whose main interest in this country is financial.' Gideon Mendel remarked on this shift in the mid-1980s: 'A lot of people began doing photography as a commitment to the political struggle ., but I think also those images were becoming valuable commodities.' This is echoed by Mofokeng: 'There was a kind of understanding that you belonged in a community and ... we're fighting the same purpose. Within there was competition too. Who's making money? Who's not making money? ... In time that broke Afra-pix.'30

By the mid-1980s professionalization became one of the key debates within Afrapix. A number of emergent photographers were able to get employment with the news agencies, such as Associated Press, Reuters or Agence France Press. This in fact enabled them to supply Afrapix with many images at the same time. Afrapix in turn sent a package each week to support networks in Europe, to organizations such as the International Defence and Aid Fund (IDAF) in London which disseminated them to further solidarity groups and student organisations. Such audiences had an impact on the kinds of images that went into circulation. The specifics are very revealing. Paddy Donnelly, who prepared photographs for public use from the growing collection at IDAF in the late 1980s, describes how the tendency was for a single story, namely 'the state as total aggressors and people as victims'. These were the market forces, as it were, of solidarity politics in the west:

You'd have people coming in looking for blood. They were looking for hard, hard-assed pictures ... And there was a lot of appalling state violence that was happening and those basically were pictures that people were fixed on. And they certainly were the pictures that people could organize a picket around or get a meeting around. You needed that sort of imagery.

The pressure was felt keenly inside the country. Santu Mofokeng relates how he came to understand the problem: 'If I show a picture of a policeman it's a good picture. If I show pictures of two policemen it's even better ... this is how I came to categorize the work I was doing at the time . If I show three policemen then that's front page ... it was bad white, good black. Not in so many words.'

Clearly, as South Africa became big news from the mid-1980s onwards, market forces through the press, and outside interests, had started to dictate the kinds of photographs that 'sold'. This signaled a hardening and proliferation of certain kinds of photography. For example, speaking of his own trajectory into the late-80s, Gideon Mendel offered this self-critique:

And whenever there was a protest or a march I felt I had to go and photograph, just in case something dramatic happened. It was a real waste of film, so much, I just got too many funerals and protests . when I really should have been trying to look beneath the surface of what was happening. ... I was repeating myself over and over and over again.31

Guy Tillim put it very succinctly: 'When I think about my work in the 1980s, I feel some regrets, we were circumscribed by quite unified ways of thinking.' Chris Ledochowski spelt it out very explicitly:

We were propagandists for the struggle. I spent four years in those COSATU meetings since its launch. ... What photos have I got to show for it? Reels of boring footage. You wait two hours for one amandla! and maybe by then you might have nodded to sleep and you miss the shot. The main shot, the Badsha or Weinberg type photo. Because we all were influenced by those archetypal shots.

He added that captions also became stereotyped: 'What is that picture of Crossroads all about? What is Crossroads? I mean if you are going to write a proper caption for this situation it's going to take you two weeks!'32 This last statement raises the issue of close knowledge (or lack of it) about the communities and places that were getting intense photographic attention. There were two related problems, firstly the social distance between the photographer and the photographed, and secondly the huge gulf between the world audience of viewers and the photographed.

A number of photographers address the first problem by pointing out that in the 1980s, as members of a progressive collective such as Afrapix, political proximity overcame class and race differences to a large extent. In Cape Town for example, Eric Miller argues that people on the Cape Flats saw photographers as fighting on the same side, the United Democratic Front, and gave them access and even protection. But the furore around Steve Hilton-Barber's exhibition in Johannesburg, concerning Sotho male initiates, showed that many South Africans felt photographers were intrusive, powerful interlopers. In this case Hilton-Barber was accused of using a position of privilege to expose secret ritual practices that were not intended for public consumption. It was in a sense an early attempt to take documentary into the art gallery. But taking the paradigm of exposure into such a dense, closed cultural field left Hilton-Barber himself uncomfortably exposed.33

A more sustained way of overcoming the problem of distance between photographers and photographed was through the training of local, young township photographers. Afrapix ran many workshops to this end. In the post-mortem discussions around the difficulties in Afrapix by 1990, this training agenda was seen as clashing with the need for professionalization in the face of international competition. In fact, the problems were more complex than this.

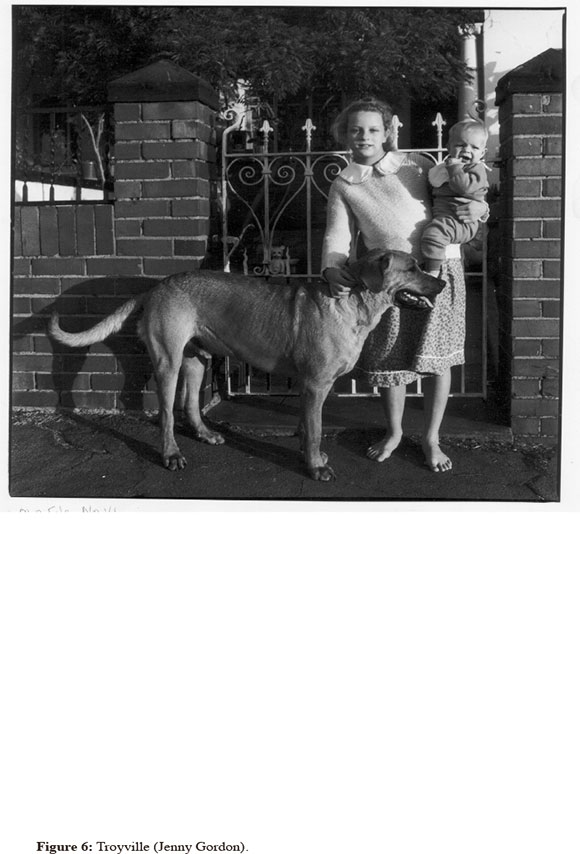

Related to proximity, there was also a move by some white photographers to photograph 'their own communities'. Encouraged by David Goldblatt, Lesley Lawson and Jenny Gordon (Figure 6) at different times both photographed the more vulnerable white sectors, the supposed beneficiaries of apartheid. The benefits were racial, yes, but in terms of class, less so. Such photographers dramatically pinpointed this.

In addition, a woman-centred even feminist agenda was apparent amongst the minority of women photographers in Afrapix. Lesley Lawson and Gille de Vlieg in particular, photographed women and gender issues, or foregrounded women in their bigger compositions, as in de Vlieg's iconic funeral photograph.

The problems of distance did not go away, despite insider positions or strong political identification. Probably this was inherent in the way photography effects multiple displacements. Santu Mofokeng recalls for instance a seminal moment in his career. A comment was written in the Visitors' Book at a small exhibition he mounted in Johannesburg, saying 'Making money with blacks'. It gave him pause. 'But the one thing I realize, I'm making pictures in the township but they get consumed in the north. They are made in the south but they are not communicating, which is another criticism too.'34

Many South African photographers were chafing against the metropolitan class implications of networks into which their work was being inserted. For some it was became a long struggle to forge a non-metropolitan visual episteme and aesthetic. The implications of consumption had an impact on creativity, and individuals responded in different ways.

Chris Ledochowski is very insistent about what the majority of South Africans wanted from photography: '[T]hey don't see themselves in black and white looking all dismal and that.' Many younger township residents in fact associate black and white photographs with poverty. Most people, quite simply, want 'beauty'. This means colour. Ledochowski's long experience in the Cape Flats, where he encountered both a desire for hand-coloured portraits (an old photographic tradition for which the Van Kalker Studio was famous) and ephemeral popular art, made him rethink his entire photographic practice. He transformed a number of his well-known black and white photographs into entirely different works, by treating them in the same way as hand-coloured portraits. 'But you force the viewer, you force them. That's my aim, you see. Just like I did with those coloured-in things. I forced you to look at this photo that is so dismal but coloured you have to look at it in a different light, you see. It can actually be quite beautiful.'35

Santu Mofokeng had another approach, which he terms the metaphorical or fictional biography. 'I'm not interested in showing how the African must live, or coloured people, or whatever. ... It's fiction, it's a metaphor about my life, things that interest me'. He began with the surfaces and spaces of the everyday, people's relationships with the things that make up their worlds, material objects, all the time controlling the play of light very carefully.

In terms of the idiosyncracies of life in the eighties whereby we want to show that apartheid is bad, I'm making pictures of ordinary life. Football, shebeen, daily life. ... When the world becomes tired of seeing ... sjamboks or whatever, they come to you they start to ask what is daily life like?

It is not so much people's relationships with each other, but with the objects that surround them in the ghetto, their landscapes, that are given an atmospheric spin. It is not quite certain what is going on, there is something unstable, unresolved. A number of Mofokeng's urban photographs are reminiscent of the surrealist notion of terrains vagues, which Andre Breton called a 'wasteland of indecisiveness'. Chance juxtapositions of street posters and reality have a 'nagging pointlessness'. 36

Andrew Tshabangu, though very different and coming from a younger cohort of Soweto photographers, also takes the realist genre into terrains that are more imprecise.

'I don't see myself as a documentary photographer. I see myself as a photographer. Not as an art photographer. When I photograph my attitude was that my approach was more documentary but the process and the editing is totally different than the documentary'.

Tshabangu states firmly that when he photographs, he photographs for himself. 'I'm not trying to change things. I don't make social comments'.37

IV. Conclusion

Nelson Mandela's release from Pollsmoor Prison in February 1990 heralded the end of a major phase in South African photography. In retrospect, and even at the time, many photographers mark it as the moment when the photographic economy shifted, with international competition putting pressure on the culture of solidarity. By 1991 Afrapix had folded. Photography was tied very closely, it would seem, to historical events.

But I want to suggest two things. Firstly, there are big photographic continuities in the longer trajectory of time. Ledochowski's fifteen years' work in the Cape Flats, and Cedric Nunn's long-term family history called Bloodlines, both originated in the 1980s. Goldblatt's method of systematically pushing at 'fuckall landscapes' as he calls them, amplifying the frame to incorporate more layers of time, make constant references to a much deeper pastness.

Secondly, the documentary archive in South Africa does not simply become the 'detritus of lapsed passion'.38 People, even those who claim to have departed from it, cannot quite leave what is called 'documentary' behind. Powerful traces of political awareness, economic dynamics, socially affected landscapes and above all, empathy with - or at the very least, dignified reference to - human subjects, inflect post-apartheid sensibilities on one level or another. I want to insist that photography now could not have happened without the documentary impetus of the 1980s, which was the breeding ground for a number of contemporary photographers. The need to mark the social in some way persists, the need to get into closer proximity with those on the receiving end of history.

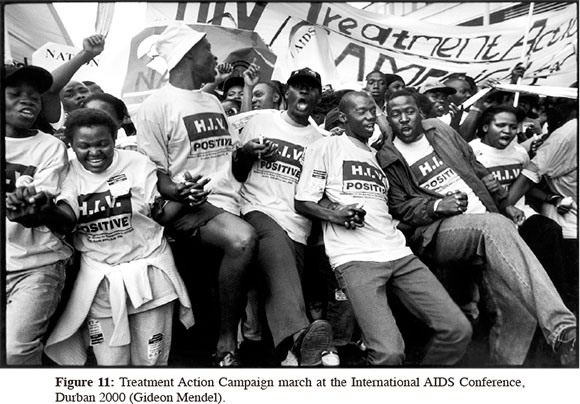

There are formal aspects to this argument. The technique and aesthetic apparent in Gideon Mendel's photograph of Treatment Action Campaign demonstrators, probably the best toyi-toyi photograph ever taken, takes a familiar genre to new levels. The protest song and dance toyi-toyi was massively photographed in the 1980s, but is incorporated here into bigger contexts of the politics of health in Africa. Visually, it is difficult to imagine any other toyi-toyi photograph which (perhaps ironically in this case) conveys such rolling, boiling movement and political force:

According to Mendel, toyi-toyi is:

[O]ne of the hardest things to photograph... Because there's a combination of things. The noise and the sound and the emotion of the singing, . the sound gets you in your chest, gets you in your heart, you think you're taking great pictures... It's something I learnt. ... But taking that [TAC] picture is probably the product of years of earlier experience, . I think I knew I was looking for a strong, positive picture. . I had to be very cerebral, to make that image.39

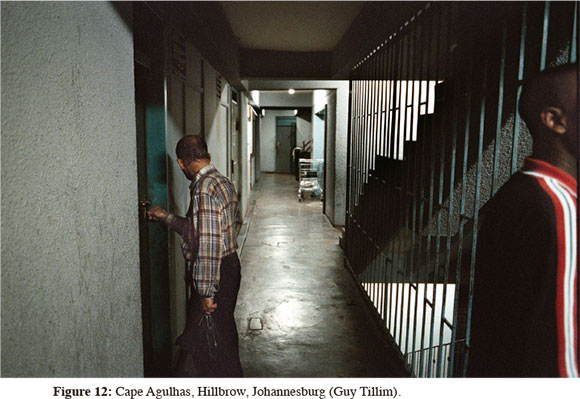

It is doubtful Guy Tillim could have taken the African photographs he did after 1994 if he had not come from the Afrapix generation. Moreover, it is doubtful he could have taken the South African urban photographs he did recently about inner city tenements, without having first photographed the postcolonial ruins of Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo. He more than most has bridged the temporalities between then and now, between Africa and South Africa, by keeping close to the human beings who cross those lines. As he himself puts it, he has gone from being a documentary photographer, to being a 'photographer of interesting spaces'.40

It might be that many photographers had de facto gone meta-documentary before the big shift. There remains a need to open the documentary debates very wide in order to render a different perception, as opposed to the simple, post-1994 anti-documentary line that many have internalized. The latter have given it a fixity that makes it easier to get a liberating sense of unfixing oneself as a photographer.41

If we look at the genesis of documentary as a genre, there were complex discourses around it from the start. Lugon describes the naming of the genre from the late 1920s as the coming of a 'multiple notion'. Very diverse works qualified.42Despite South African self-critiques, the Afrapix generation have a very ambiguous unity, especially as their work extends into the present.

There is no doubt that documentary was considered the appropriate genre from the early 1980s and even before. The imperatives of the 1980s, the agendas of visibility if you like, evoke terms like exposure, truth-telling, reality, documenting, recording, showing, educating - in the face of the lies (often called distortions), concealment and violence of the state. But documentary has its problems. What is fascinating is the way South African photographers were taking a full documentary turn in the 1980s at the very time it was falling from grace in Europe and North America.43 Some would say that events compelled South African photographers to do so. But parallel documentary debates have unfolded locally in South Africa as auto-critiques within photographic circles, and have become especially articulate in recent years with the clarity of hindsight.

In fact since 1994 the term 'documentary' has solidified in a particular way in South African contexts, partly as a functional mechanism to distinguish between the apartheid then and the post-apartheid now. It was relevant then, but is often seen to be limiting now. If the risk then was physical, with all the dangers attendant on exposing injustice and brutality - which Enwezor characterizes as 'heroic documentary'43 - the risk now is possibly more personal, introspective, enigmatic and intellectual. Women photographers seem to find it easier to broach some of these intimate dangers than male photographers. Jo Ratcliffe, Jodi Bieber, Lien Botha, Zanele Muholi and Nontsikelelo Veleko testify eloquently to this in their work.

The simple dichotomy, however, this separation of eras, masks over many photographic continuities. Also, the nature of peace is such that it brings its own turbulence and unresolved conflicts, its new manifestations of old public poverties and sufferings. The explosion of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in southern Africa represents, most ironically perhaps, a challenging synthesis of the two photographic poles: how to represent 'universal' human suffering on a political and social plane so that something will be done, together with the intimacies and implications of sexuality, anxiety and death on the most individual, familial level. It is not simply, objectively a broken landscape, but many broken subjective landscapes.

As photography flickers out of the old institutional space of the media into the new regime of the art gallery, commercial interests still abound. Photographers remain with the dilemma of the gulf they create between the audiences looking at their work, and the people and issues they photograph. In a more ideal world, of course, it would be sufficient for the Santu Mofokengs to follow their most creative method, which is very simple. 'I just most of the time I stay on my own and I dream about what I need to do, and I do it.'44

1 Talbot's early English patent kept the calotype under strict control, but the French daguerreotype spread without inhibition after 1839. M.Bull and J.Denfield, Secure the Shadow. The Story of Cape Photography from its Beginnings to the end of 1870 (Cape Town: Terence McNally, 1970), Chapter 1.

2 A.Sekula, Fish Story (Rotterdam and Düsseldorf: Richter Verlag, 1995), 43.

3 A.D.Bensusan, Silver Images (Cape Town: Howard Timmins, 1966).

4 The photograph was taken by Durney. See H.Bradford, 'Framing African Women' in Kronos, vol. 30, Nov. 2004. My argument here takes a different turn to Bradford, who does not ask what later audiences who identify with Nongqawuse's history might see in a visual record that physically identifies the prophetess.

5 W.Benjamin, Illuminations (London: Fontana Press, 1982), 215.

6 J.Tagg, The Burden of Representation (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1988), 63.

7 A.Bank, Bushmen in a Victorian World (Cape Town: Double Story, 2006), 125; also E.Edwards, Raw Histories (Oxford: Berg, 2001), 140-1. Particular informants were also photographed in studio and other settings.

8 Mikhael Subotzky, 'Inside and outside: Mikhael Subotzky in conversation with Michael Godby' in Kronos, vol. 32, Nov. 2006.

9 See A.Bank, 'Anthropology and Portrait Photography: Gustav Fritsch's "Natives of South Africa", 1863-1872', in Kronos, vol. 27, Nov. 2001.

10 This dualism is borrowed from A.Sekula, 'The Body and the Archive' in R.Bolton, ed., The Contest of Meaning (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1992).

11 M.Aird, 'Growing up with Aborigines' in C.Pinney and N.Peterson, eds., Photography's Other Histories (Durham: Duke

University Press, 2003), 25.

12 S.Mofokeng, 'The black photo album' in Revue Noire, Anthology of African and Indian Ocean Photography (Paris: Revue Noire, 1998); U.Dhupelia-Mesthrie, From Cane Fields to Freedom (Cape Town: Kwela, 2000).

13 K.Grundlingh, 'The development of photography in South Africa' in Revue Noire, Anthology of African and Indian Ocean Photography (Paris: Revue Noire, 1999), 244.

14 See G.Minkley and C.Rassool, 'Photography with a Difference: Leon Levson's Camera Studies and Photographic Exhibitions of Native Life in South Africa, 1947-1950' in Kronos, vol. 31, 2005.

15 M. du Toit, 'The General View and Beyond: From Slumyard to Township in Ellen Hellmann's Photographs of Women and the African Familial in the 1930s', Gender & History, vol. 17(3), November 2005.

16 E.Weinberg, Portrait of a People: A Personal Photographic Record of the South African Liberation Struggle (London: International Defence and Aid Fund, 1981).

17 E.Cole, House of Bondage (London: Penguin, 1967).

18 See J.Johnson and P.Magubane, Soweto Speaks (Johannesburg: Donker, 1979).

19 I am grateful to Graham Goddard for his suggestions concerning photographic practice in the 1980s.

20 The phrase comes from J.Roberts, The Art of Interruption (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998), 9. Badsha's work includes Letter to Farzanah (Durban: Institute for Black Research, 1979); Imijondolo (Durban: Afrapix, 1985); Imperial Ghetto (Maroaleng: SAHO, 2001). Omar Badsha and others were interviewed by the Project in Documentary Photography, located at the University of the Western Cape. All interviews cited in the essay arise from this research, which is funded by the National Research Foundation of South Africa and the Senate Research Committee of the University of the Western Cape. The author gratefully acknowledges the participation and co-operation of all photographers.

21 Cedric Nunn interviewed by Farzanah Badsha, Johannesburg, July 2002.

22 Lesley Lawson interviewed by Patricia Hayes, London, 24 July 2002.

23 Cedric Nunn interviewed by Farzanah Badsha, Johannesburg, July 2002.

24 Omar Badsha and Francis Wilson, South Africa. The Cordoned Heart (Cape Town: Galleiy Press, 1986); Beyond the Barricades. Popular Resistance in South Africa (New York: Aperture, 1989). Staffrider and other journals such as Full Frame also encouraged the more considered photo-essay approach.

25 Eric Miller interviewed by Patricia Hayes, Cape Town, 5 August 2002.

26 Elizabeth Edwards, Raw Histories (Oxford: Berg, 2001).

27 Interview with William Kentridge, Sunday Independent, 7 October 2007.

28 A.Solomon-Godeau, Photography at the Dock (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1991), 180.

29 W.J.T.Mitchell, What Do Pictures Want? The Lives and Loves of Images (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2005), 47.

30 Santu Mofokeng, interviewed by Patricia Hayes, Farzanah Badsha and Mdu Xakaza, Johannesburg, 24 July 2005.

31 Gideon Mendel, interviewed by Patricia Hayes, London, 23 July 2002. Mendel in fact was not officially a member of Afra-pix, but closely associated with many who were.

32 Chris Ledochowski, interviewed by Patricia Hayes, Farzanah Badsha and Natasha Becker, Cape Town, 22 September 2002.

33 Peter Magubane did not suffer the same fate when he published similar photographs in his first post-apartheid publication, Vanishing Cultures of South Africa (Cape Town: Struik, 1998).

34 Santu Mofokeng, interviewed by Patricia Hayes, Farzanah Badsha and Mdu Xakaza, Johannesburg, 24 July 2005.

35 Chris Ledochowski, interviewed by Patricia Hayes, Farzanah Badsha and Natasha Becker, Cape Town, 22 September 2002.

36 I.Walker, City Gorged with Dreams. Surrealism and Documentary Photography in Interwar Paris (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002), 174-5.

37 Andrew Tshabangu interviewed by Patricia Hayes, Farzanah Badsha and Mdu Xakaza, Johannesburg, 24 July 2005.

38 D.Vaughan, For Documentary (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 41.

39 Gideon Mendel, interviewed by Patricia Hayes, London, 23 July 2002.

40 Guy Tillim interviewed by Patricia Hayes, Farzanah Badsha and Natasha Becker, Cape Town, 14 May 2003.

41 See for example G.Wood, 'Still Lives. Interviews with seven of South Africa's best photographers', Contempo, June-July 2006, No 2, 74.

42 O.Lugon, Le style documentaire. D'August Sander à Walker Evans (Paris: Macula, 2001), 15-16.

43 See for example A.Solomon-Godeau, Photography at the Dock (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1991), and S.Stein and M.Rosler in R.Bolton, ed., The Contest of Meaning (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1992).

44 O.Enwezor, Snap Judgments. New Positions in Contemporary African Photography (New York: International Centre of Photography, 2006), 17.

45 Santu Mofokeng, interviewed by Patricia Hayes, Farzanah Badsha and Mdu Xakaza, Johannesburg, 24 July 2005. The author wishes to extend deep thanks to Eric Miller, Lesley Lawson, Gillee de Vlieg, Jenny Gordon, Chris Ledochowski, Santu Mofokeng, Gideon Mendel, Guy Tillim, William Kentridge and the South African National Library for generous permission to reproduce their images in this essay.