Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

Cited by Google

Cited by Google Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SA Journal of Industrial Psychology

On-line version ISSN 2071-0763

Print version ISSN 0258-5200

SA j. ind. Psychol. vol.38 n.2 Johannesburg Jan. 2012

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Humour as defence against the anxiety manifesting in diversity experiences

Olga Coetzee; Frans Cilliers

Department of Industrial and Organisational Psychology, University of South Africa, South Africa

ABSTRACT

ORIENTATION: Using humour in diversity contexts may relieve tension temporarily, but it happens at the expense of someone and indicates a defence against an unconscious anxiety dynamic.

RESEARCH PURPOSE: The purpose of this research was to describe the manifestation of humour as a defence mechanism against diversity anxiety.

MOTIVATION FOR THE RESEARCH: In working with diversity dynamics in South African organisations, consultants and participants often do not take humour seriously, let alone interpret the accompanying dynamic aspects. Working below the surface with humour may elicit much more and typical diversity dynamics worth investigating.

RESEARCH DESIGN, APPROACH AND METHOD: The research design was qualitative and descriptive, using multiple case studies and content analysis.

MAIN FINDINGS: Humour is used as a defence against the anxiety experienced in diversity contexts caused by fear of the unknown within the self and the projection of the fear onto another identity group.

PRACTICAL/MANAGERIAL APPLICATION: Diversity consultations interpreting humour as defence mechanism can provide added opportunities for exploring dynamics below the surface.

CONTRIBUTION/VALUE-ADD: Deeper understanding of the unconscious dynamics of diversity humour could lead to meaningful interventions in organisations.

Introduction

The use of humour in diversity contexts is often defended as breaking the ice because the laughter relieves tension and participants feel more at ease. The question is whether everyone feels more at ease - even the person(s) at whose expense the joke was made? In one of the case studies discussed in this study, the statement was made, 'we have made so much progress with diversity that we can now openly joke about our differences.' It could be argued that this is not progress, but a (unconscious) defence against the anxiety provoking work with the real deep-seated stereotypes and prejudices that underlie the joke. What is really below the 'racist joke', the 'blonde joke', the 'gay joke' and the 'gender joke'?

The global human rights drive has led to the emancipation of previously oppressed race, gender, religious and sexual orientation groups. This, together with the post-apartheid era in South Africa, has necessitated ongoing diversity interventions in organisations to enable performance in the face of the diversity challenge (Coetzee, 2007). The challenge is to create unity in contexts in which people from different identity groups such as race, gender, generation or sexual orientation are expected to work together in heterogeneous teams (Cilliers, 2007). This is amplified in South African work groups because employees come from a vast array of cultural backgrounds and religions (Maier, 2002), have different dietary laws, dress codes and cultural taboos (Elion & Strieman, 2002), and they are also economically split between very rich and very poor (Chasing the rainbow, 2006). Employees often carry complex unresolved emotions such as anger and guilt from the apartheid era (Booysen, 2005; Pretorius, 2003). Coetzee (2007) developed and tested the face validity of the Community Building Model (CBM) for diversity consultation by means of which the conscious and unconscious interpersonal and intergroup dynamics occurring in diverse organisational settings can be explored. Humour was one of the diversity themes in Coetzee's (2007) work.

The chosen research paradigm and theory, and systems psychodynamics is based on psychoanalysis, systems theory and object relations theory (Cilliers & Koortzen, 1996). As a consulting stance, systems psychodynamics refers to the notion of group-as-whole which becomes the unit of organisational analysis (Stokes, 1994; Thelen, 1998). This thinking was linked to systems theory with its focus on relatedness and relationship issues between systems with the focus on the reciprocity, recursion and shared responsibility in a dynamic manner (Becvar & Becvar, 2000). An organisation is conceptualised as an open system in exchange with its environment, consisting of various physical and psychological sub-systems, the latter being influenced by phenomena suchas individual behaviour, status and role relationships, group dynamics, beliefs, values, expectations, anxieties and defence mechanisms (Stapley, 2006). The object relations theory focuses on the need of human objects to be attached, related and connected to other objects (Czander, 1993). Individuals develop the psychological capacity to relate to external (real) and internal (fantasy) objects including people, organisations, groups, ideas, and symbols (Cashdan, 1988). The worker enters the work situation with unfulfilled unconscious attachment needs and fantasies (Pick, 1992). Because the work group is not the family and does not fulfil those needs, the individual experiences conflict and frustration (Czander, 1993). The resulting anxiety may mobilise regression to infantile coping defences such as paranoid-schizoid behaviour, implying the splitting off of feelings into differentiated elements such as good and bad, and projection of the bad feelings onto others (Klein, 1997).

Le Bon theorised that a person becomes influenced when joining a group and will often act on the will of the group (Fraher, 2004). The behaviour of a group member may therefore be either the expression of own needs, or the needs of the group (Sandigo, 1991). Bion (1961) believed that most groups have a more primitive culture when they have just formed, a phase in which they resist dealing with painful emotions. Group development is about the struggle between the group's primitive instincts to avoid the pain and its need to deal with the feelings of coming together in the first place (Schulman, 2010). Bion (1961) hypothesized that any group therefore has two modes of operation that it may use: the work group is preoccupied with the formal task, whereas the basic assumption group is preoccupied with survival and the use of defence mechanisms to ease the group's anxiety (Fraher, 2004; Halton, 1994). Bion (1961; 1970) identified three basic assumptions. In fight-flight, the group is in fight against, or flight from an enemy. In pairing, the group fantasises about a connection between two members (or equivalents) to generate a saviour or saving idea. In dependence, the group is dependent on a leader, experienced as omnipotent, but at the same time set up to take the blame if the group should fail. A fourth assumption introduced by Turquet (1985), is oneness, where members are joined in a powerful union or bigger cause and they have surrendered self for passive participation and the feeling of wholeness. A fifth assumption is me-ness, where the individual who experiences engaging and connecting with the group as too threatening, retreats into self-reliance (Lawrence, Bain & Gould, 1996). A basic assumption group functions on group defences and uses its energy to relieve its anxiety instead of achieving any effective output (Huffington, Armstrong, Halton, Hoyle & Pooley, 2005).

The systems psychodynamic paradigm was chosen for this research because of its capacity to give the researcher access to the study of the manifestation of anxiety around diversity and the unconscious defence mechanisms used in a group setting to cope with this anxiety.The purpose of this research is to describe the manifestation of humour as a defence mechanism against diversity anxiety. Thus, the research addresses the gap in the literature around how diversity consultants can work effectively with manifesting humour. The research also addresses the notion mentioned in the literature that consultants may use (sometimes funny) icebreakers to relieve stress. In this research it is argued that it is the consultant's stress which is in need of relief and is being projected onto the client. Seeing and interpreting humour as a serious dynamic could help in understanding the unconscious anxiety being covered up.

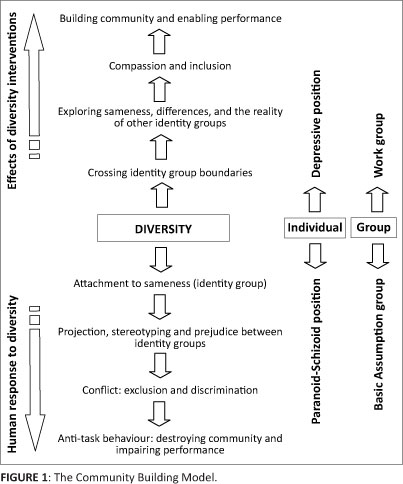

The systems psychodynamic literature contains little evidence of its application in studying diversity in organisations. Research by Foster, Dickinson, Bishop and Klein (2006) has applied its thinking to psychotherapy. Other international studies illustrated its application towards the understanding of cultural differences, racism and racial dynamics as phenomena and their influence on leadership, authority and power (see McRae & Short, 2010; Morgan-Jones, 2010; White, 2006). These studies were theorising about diversity, not based on experiential events such as workshops or coaching. The outcome of South African diversity dynamic experiential events is documented in various studies (Cilliers, 2007; Cilliers & May, 2002; Cilliers & Smit, 2006). The research suggested that such events have significant impact on the understanding of diversity dynamics for individuals, groups and the organisation. Humour has never been studied in this context, although Coetzee (2007) did refer to humour as a dimension which influences diversity dynamics. Her Community Building Model (CBM) (see Figure below) was chosen as reference point in this research.

Coetzee (2007) documented the following on diversity dynamic behaviour:

Individuals tend to attach themselves to sameness to form identity groups in order to reduce the anxiety resulting from diversity and the fear of the unknown. Each individual is a member of a multitude of identity groups, depending on the sameness observed in a given context. Behaviours between identity groups include projection, stereotyping and prejudice which may deteriorate into conflict between identity groups, manifesting themselves in exclusion and discrimination. The conflict is often maintained by collusion on the part of those against whom the exclusion and discrimination is aimed. The sense of community is destroyed by these dynamics, impairing performance of the individual, group and organisational levels.

On the individual level, intra- and interpersonal dynamics which may result from the human response to diversity, are based on splitting and projection as defences against anxiety, which is why the bottom half of the model is identified as happening in the paranoid-schizoid position of the individual. On the group level, intra- and inter-group dynamics are based on group defences against anxiety, which is why the bottom half of the model is identified as 'assumption group functioning'.

According to Coetzee (2007) the work of valuing diversity (top half of the model - moving upwards) relates to how destructive interpersonal and inter-group diversity dynamics can be replaced by constructive dynamics:

The crossing of identity group boundaries, although anxiety provoking, leads to the exploration of sameness, differences and the realities of diverse groups. Individuals and groups develop a better understanding and trust of each other, laying the foundation for attachments across identity-group boundaries and the formation of task-group boundaries. The compassion which people inevitably feel for one another when they become acquainted with each other, leads to the desire to include everyone into the task group. This desire to include others builds an organisational community which enables performance by the individual, group and on organisational levels.

On the individual level of functioning, intra- and interpersonal dynamics which may result from diversity interventions and are based on the taking back and giving back of projections and prejudices, as well as integrating opposite feelings, which is why the top half of the model is identified as the 'depressive position' of the individual. Similarly, on the group level of functioning, taking back and giving back projections and prejudices and discarding basic assumptions are the basis for engaging in the task at hand, which is why the top half of the model is identified as the 'work group'.

Coetzee (2007) explored humour in diversity contexts as one of the themes that emerged from the data of the qualitative research procedure. The interpretation of humour across racial boundaries was that it was based on fight-flight assumption group functioning to reduce the anxiety of the group in the diverse setting. Coetzee (2007) points out that such humour perpetuates stereotypes and destroys the sense of community in groups.

Literature on the psychology of humour (Barron, 1999; Carr, 2004; Lemma, 2000; Martin, 2007; Morreall, 1983) proposes and explores different theories. These theories can broadly be grouped into the following:

1. superiority theory in which the amused party feels a sense of triumph over the subject of amusement and/or the people that they are threatened by

2. incongruity theory in which humour is seen as an intellectual reaction to something unexpected, illogical or inappropriate

3. relief theory in which humour is seen as tension relief and a means of coping with adversity

4. arousal theory which sees humour as the result of people seeking to enhance their level of arousal for pleasure's sake

5. reversal theory which positions humour as a playground or safety zone in which humans can isolate themselves from the serious concerns of the real world.

Although some of these theories include systems psychodynamic thinking, they represent different paradigms.

Psychoanalytic and systems psychodynamic thinking on humour include the following. Freud (1960) distinguished between innocent jokes which intend only pleasure and tendentious jokes that run the risk of reaching people who do not want to listen to them. Tendentious jokes are either hostile (aggressive) or obscene (the purpose is exposure). Tendentious jokes require three parties: the person who makes the joke, the person who is used as the object of the hostility, and a third person who will be enlisted in the hostility if the joke succeeds in its purpose. So-called blonde jokes are clearly tendentious in nature because there is the joke teller, the blonde person (usually a woman) who is the object of the hostility and often present when the joke is being told, and the third person who is enlisted to support the projection of stupidity onto the blonde person. Blackman (2004) provides support for Freud's view that humour is not always a defence against anxiety, but sometimes simply the injection of inappropriate meanings, exaggerations, condensed illusions, drive-related fantasies, sadistic symbols, and grammatical inversion for the purpose of producing pleasure.

Grotstein (1999) provides an analytic description of the differences between humour in the paranoid-schizoid position and humour in the depressive position. Humour in the paranoid-schizoid position often takes the form of mocking and sarcasm which is indicative of projecting some negative issue 'out there', whereas humour in the depressive position, which allows the individual to view situations from different perspectives, is broader, more forgiving and more philosophical and appreciative of paradoxes and ambiguities.

Schulman (2010) described humour as a fight-flight basic assumption functioning in primitive groups to avoid painful feelings. Group members unite in an unconscious process to form the fight-flight group acting from the basic assumption that the group's objective is to avoid pain. An example would be of the group clown, who will use humour as a distraction just when difficult situation is emerging. The role of the group clown is one that therefore expresses the needs of a group and not necessarily that of the individual (Sandigo, 1991). This interpretation of humour is similar to Coetzee's (2007) interpretation of humour across racial boundaries in diverse settings.

The research problem was formulated as follows: Is humour used in diversity contexts as an innocent relief of tension or does it have a hostile, obstructive side similar to what Freud found in psychotherapy? In doing so, the question was asked whether the findings could be explained by Coetzee's (2007) CBM.

The research objectives were as follows:

To achieve a better understanding of the manifestation of humour as unconscious defence against anxiety in diversity experiences;

To use the CBM as a theoretical reference point to ground the findings in literature.

Next, the research design is described, detailing the approach, strategy and method. The setting, the role of the researcher and the method of sampling are given and the data collection and data analysis are described. This is followed by the research findings. Lastly, the discussion is presented consisting of the interpretation of the findings integrated into the research hypothesis, the conclusion, recommendations, limitations and suggestions for future research.

Research design

Research approach

Qualitative and descriptive research (Terre Blanche, Durrheim & Painter, 2006) was chosen as a process of inquiry towards obtaining an in-depth picture on how humour manifests itself as a phenomenon in a natural setting in the words and actions of clients (Stake, 2005). An interpretive paradigm was used, engaging the how's and what's of the social reality of humour as a defence against anxiety in diverse settings, following a process of apprehension, understanding, organising and conveying of this social reality (Holstein & Gubrium, 2005). This enabled the researchers to ensure the three tenets of the qualitative method, namely describing, understanding, and explaining (Tellis, 1997).

Research strategy

Multiple (three) cases forming a collective case study were used (Chamberlayne, Bornat & Apitzsch, 2004). The cases were treated individually and then integrated into the construction of the research hypothesis (Rosenwald, 1988), theory building and reflection of the data (Creswell, 1998; Yin, 1994) compared to a diversity community-building model.

Research method

Research setting

The research setting was individual and group diversity consultations in different organisations. Case study 1 was a feedback presentation after a qualitative survey that assessed the manifestations of racism and sexism in a work setting made up of mostly blue-collar employees. Case study 2 was a leadership and diversity workshop at a conference venue with participants from the Netherlands. Participants had just completed a three-day field tour of their industry in South Africa becoming aware of the diversity in this country. Through experiential-learning events they were invited to work with their own intra- and inter-group diversity behavioural manifestations. Case study 3 was an individual coaching session in which the coachee brought his need to work with his own offensive humour, which frequently brought him into regarding diversity dimensions. The purpose of the session was to reflect on the process and to understand the triggers that lead to humour.

Entrée and establishing researcher roles

The first researcher took up the roles as organisational development consultant and executive coach. In case study 1 the organisation invited her to give feedback to employees and facilitate a discussion on the findings of the survey which she had conducted. In case study 2 she was contracted by a service provider to facilitate the workshop. In case 3 she acted as executive coach in an individual coaching session. The second researcher took up the role as research supervisor (Clarke & Hoggett, 2009). Both researchers used the orientation of self as instrument of analysis (McCormick & White, 2000).

Sampling

Purposeful sampling (Terre Blanche, Durrheim & Painter, 2006) was used for information-rich cases (Patton, 1990) that entailed work in diversity settings, and in which humour manifested itself either as behaviour or as conversation content. The three case studies were chosen by scrutinising the professional consulting notes of the first researcher.

Data collection method

Data was collected by observation of verbal and non-verbal behaviour (Clarke & Hoggett, 2009).

Recording of data

Hinshelwood and Skogstad's (2005) guidelines were followed, namely: the data was electronically recorded accompanied by researcher comments after each session on the behavioural processes and the researcher's subjective experiences during and after the event.

Data analysis

Content analysis was conducted (Patton, 1990) on the cause-effect relationships of the descriptive data relating to humour of the interpersonal and inter-group dynamics of the respondents. Thus, primary patterns of behaviour manifested themselves, which were related to the literature on symptoms of unconscious group dynamics as the cause of humour. Finally, the data was interpreted in the context of the CBM as a theoretical reference point to ground the findings in literature.

Strategies employed to ensure quality data

Ethicality (Terre Blanche, Durrheim & Painter, 2006) was ensured by obtaining the consent of the participants to use and interpret the data and for keeping their identities confidential. In terms of the integrity of the analysis (Patton, 1990), care was taken to look for rival or competing themes and explanations (Patton, 1990), specifically attempting to interpret the patterns of humour first as tendentious, then as innocent (Freud, 1960), before using the tendentious interpretations. Trustworthiness was ensured through triangulation (Patton, 1990). Both researchers analysed the data. They are both psychologists with doctorate degrees and specific training, theoretical knowledge and experience in systems psychodynamic consulting and research (conforming to the requirements set by Brunner, Nutkevitch and Sher, 2006). The data analysis was assessed favourably by two psychologists and/or consultants familiar with the methodology. The researchers acknowledge the existence of subjective experience and that there may be more than one interpretation for the same experience by different researchers (Holstein & Gubrium, 2005).

Reporting

The research findings are reported per case study. In the discussion, the three cases are interpreted and integrated into the research hypothesis. This is followed by the conclusions, recommendations, limitations and suggestions for further research.

Findings

Case study one

At the beginning of the survey feedback-session it was striking to observe that employees sat separately, divided into race and gender identity groups (Black men, Black women, and White men). There was one exception: in the fifth row from the front a Black man (P1) and White man (P2) sat side by side, having a friendly conversation with each other before the presentation started. During the feedback presentation the consultant shared several observations of manifested racism. The tension was building in the room until the consultant was interrupted by P2. He said: 'There is not as much racism as you are talking about. We have made a lot of progress. This man next to me is my friend.' This was met by several remarks from the audience such as, 'Hello sweetheart!' and 'I love you, darling!' followed by thunderous laughter. The Black man (P1) put his arm around P2's shoulders and gave him a hug. More laughter followed. Once the laughter died down P2 said:

'The guys are just joking. We are not like that. We are just good friends. We have made so much progress with diversity that we can now openly joke about our differences.' (Particant 2, White male)

The anxiety in the setting was already visible as participants entered the room to take their seats. They seated themselves in identity groups, holding seats open to accommodate sameness and not diversity, indicating how they unconsciously acted out the basic assumption group fight (Stapley, 2006) as symptom of the anxiety in the system. The Black men were seated on the left-hand side, the White men on the right-hand side of the room, and the Black women in one row. The atmosphere was tense with no verbal participation, even when the consultant offered the opportunity for questions. Body language (nodding and head shaking) indicated strong disagreement or agreement by different individuals with the content of the findings of the research. Once P2 spoke people started making fun of the two men and their cross-cultural friendship, the tension was relieved. The humorous remarks implied that the two men were romantically involved with each other. The topic under discussion at the time was racism and not sexual identity. The change in content seemed to place the cause of the tension - the pair who dared to have an inter-cultural friendship - 'out there' and away from the group. The flight response was interpreted as a defence away from the anxiety of everybody's racism (as per the consultant's feedback) towards the sexual innuendo of two people of opposite race.

Exploring the behaviour by means of the CBM indicated that the participants who made the humorous remarks seemed to form a new identity group which indicated that the two men in question must be so different from the rest of the group that they projected another 'taboo', that of homosexuality, onto the men. The reaction of P2 ('we are not like that') indicated that, although he was now included in the new dyad, he was also excluded from the bigger group, claiming compassion and inclusion that didn't exist at that point in time. The defences at play were the denial of the seriousness of the racial matters, followed by the projection of the anxiety onto the new identity group consisting of the pair, and the pair's identity with the projection in taking on the anxiety, denying the content, but owning the anxiety.

Case study two

The Dutch participants addressed diversity in a cognitive manner, about how it manifests in South Africa (as something 'out there') as well as in the Netherlands with increasing numbers of Turks and Moroccans in the workplace. On the other hand, their anxiety levels were raised when they started to experience their own intra- and inter-group diversity. During their feedback after a small-group conversation, one participant (P3) gave feedback. He was struggling to express himself in English (the workshop language) about his realisation around the diversity issues of which he became aware. He was a Dutch-speaking Moroccan. Another participant (P4) who was fluent in English started mocking him about his 'Dutch-like English'. The group found that very humorous and laughed so much that they did not see the humiliation their laughter caused P3. It was only once he insisted to give the rest of his feedback in Dutch and the situation was analysed in more depth, that his humiliation became clear to the group.

The consultant facilitated the group's awareness of their heterogeneous nature in every sense, and pointed out that diversity exists in each individual and group. The system could use the humorous event as a potential space (Diamond & Allcorn, 2009) where their own diversity could be embraced before they could embrace the diversity of the other. The interpretation based on the CBM was that the group assumed that space because he was Dutch-speaking and he was of Dutch origin (one of them). Their humour about his Dutchlike English could be interpreted as an attempt to attach to sameness and not to explore the differences and the reality of other identity groups, keeping the Moroccans 'out there'. The group was functioning in its 'oneness', using humour as a defence against the anxiety they experienced when they realised that they were not homogeneous in every respect (Huffington, Armstrong, Halton, Hoyle & Pooley, 2005).

Case study three

In the individual coaching session, the coach provided opportunities for the coachee to reflect on incidents to ascertain his triggers which could assist in developing a strategy to change his behaviour. He cited various incidents which revealed his ideology of being superior to diverse others. He was a conservative Afrikaner who grew up in the apartheid era in South Africa in a family where women were subservient. Although he spoke about his transformation to an open-minded person who is committed to 'the new South Africa' and to the equality of women in the workplace, his sense of humour revealed his deep-seated, unconscious belief system of superiority. His jokes were degrading to females (reducing them to sex objects); to people of other race groups (insinuating that Black people were less intelligent, people of mixed race had no culture or pride, Indian people had no integrity); to the youth (revealing the belief that they needed absolute domination); and to gay people (reducing them to sex-offenders in terms of paedophilia and rape). Situations in which he was required to treat diverse people as equals made him anxious and resorted to offensive humour to break the ice.

At the beginning of the coaching session the coachee experienced the problem as being 'out there', that people who were different from him were too sensitive and overreacted when he was trying to be friendly through joking.

Seeing the problem as 'out there', is typical of the paranoid-schizoid position (Stapley, 2006) indicated on the CBM and the stereotyping content of his jokes confirmed this position. It was only once he faced a few of his own sensitivities through the revision of situations in which he was being stereotyped as a racist, as conservative, and as a coloniser through offensive jokes made by others, that he realised the effect of his behaviour on others. He realised that the intention of his jokes was to keep him in a superior position by belittling others. He discovered that, although he thought he had adapted to political democratisation and the human rights movement, he still had a deep-seated ideology of superiority. He realised that he kept that ideology intact by projecting his weakness 'out there' onto people who were different from him. He started the very difficult work of taking back projections and getting to know people from different identity groups on a much more meaningful level, which allowed him to see strengths in diverse others, and to develop compassion and the desire to value diversity and include people from diverse identity groups in functional teams.

The humour that manifested itself in all three cases was not innocent in nature. It seemed to reduce the anxiety for some participants in the diversity context, whereas at least one person was humiliated or offended by the humour. The humour was used to exclude diversity in case 1, to deny the existence of diversity in case 2, and to exclude diversity again in case 3. In the cause-effect relationships that were found in these descriptive case studies, the cause was anxiety-provoked by the diversity setting, the moderator was humour, and the effect was a reduction in anxiety for some people, whereas others, at whose expense the humour was had, were humiliated or offended.

Discussion

The purpose of this research is to describe the manifestation of humour as a defence mechanism against diversity anxiety.

Diversity dynamics events are associated with high levels of anxiety which are often dealt with through humour. Consultants often collude with the group's defence of denying the significance of the humour and seeing it as a stress release. This research focussed on the significance of attending to the dynamics of the humour as a potential space to enter the unconscious defences against the diversity issues.

In case 1 the paranoid anxiety (Armstrong, 2005) was probably caused by the fear of respondents to be identified and victimised as racists and sexists. It was also interpreted as their defence against guilt and shame (Mollon, 2004). This may explain why employees sought the comfort of identity groups in deciding where to sit, which was indicative of the fight-flight defence to reduce the experienced anxiety (Klein, 2005). The anxiety prevailed, however, evidenced by the tense, quiet atmosphere. The next attempt at reducing the anxiety was the friendly conversation between the Black and White men which was interpreted as a pairing defence unconsciously orchestrated by the group in the hope that such pairing would give birth to a saviour that would relieve the anxiety of the group (Campbell & Groenbaek, 2006). During the presentation anxiety may have been caused by the guilt and fear dynamics that are often found in South African diversity settings (Booysen, 2005; Pretorius, 2003). The White man's statement of denial of racism was an attempt at using a oneness as a defence against the anxiety. The humour that followed, which implied that the cross-cultural friendship was in effect a homosexual relationship, was interpreted as flight - an attempt to place the friendship 'out there', in a reality that is denied in this very conservative setting (Campbell, 2007). The topic under discussion at the time was racism and not sexual identity and the change in content provided evidence for the flight dynamic. The bottom part of the CBM (Coetzee, 2007) can be used to further explain the humour dynamics. The split caused by the humour between the two men and the rest of the group, created identity groups that were not based on reality (because sexual identity seemed a taboo topic in this group, the assumption was that the men were heterosexual). The group's unconscious fantasy was that this was a homosexual relationship. The White man's response of denial to the group's projection ('we are not like that') indicated his victim position in the humour, which provided evidence for the tendentious nature of the humour. Anyone present who might have been a homosexual person could be seen as the real victim because of the experience of alienation of an identity group that is 'out' in that community.

Case 2 participants were confronted with their own internal diversity. Until that point, they experienced diversity to be 'out there' in society. The moment they started giving feedback about their own diversity, it became visible how carefully and tentatively they expressed themselves. This was interpreted as their anxiety as a result of their threatened identity as a homogenous group (Vansina & Vansina-Cobbaert, 2008). The humour in that situation (see Coetzee, 2007) caused a split between participants who spoke fluent English (first identity group) and participants who struggled to speak English (second identity group). It seemed easier to deal with language through projective humour that seemed innocent on the surface, but obviously caused humiliation for the person who was the victim thereof. The denial of racial differences in the group was interpreted as a flight against the anxiety of dealing with the realisation that the group was not homogenous but heterogeneous (Campbell & Huffington, 2008).

These two cases have something interesting in common. There was a dynamic of super-imposing identity groups created by the humour over the identity groups that were denied because it became too painful to deal with them. In the first case the sexual-identity groups were super-imposed over the Black and White race groups. In the second case the language identity groups were super-imposed over the Netherlander versus Moroccan race groups. On the surface the made-up identity groups may look like the playground or safety zone mentioned in reversal theory, in which humans can isolate themselves from the serious concerns of the real world (Barron, 1999; Carr, 2004; Lemma, 2000; Martin, 2007;

Morreall, 1983). When the humiliation of someone present is taken into consideration though, the humour can no longer be seen as innocent, instead its dark and aggressive projective nature has to be recognised.

Case 3 was somewhat different in that the behaviour (offensive humour of the individual) was not taking place on behalf of a present group. The behaviour was driven by an individual's need placed in the bottom half of the CBM model (Coetzee, 2007), in the paranoid-schizoid position. The individual is splitting off bad parts of the self and projecting these onto identity groups that were previously oppressed by the identity group to which he belongs (Afrikaner male). The bad parts being split off related for example, to sexuality (projected onto females) and intellect (projected as the lack thereof onto Black people). The coaching intervention was aimed at providing an opportunity for empathy for the underdog, in the hope that he might move to the depressive position, own his projections and integrate the bad parts with superiority into a more realistic, balanced self.

In case 1 the group chose fight-flight and used humour to avoid diversity issues. In case 2 the group chose oneness and humour to deny the existence of diversity in the group -which was a more indirect way of excluding diversity by not valuing it. In case 3 the individual related to identity groups through splitting and projection as defences accompanied by humour. He projected his weaknesses onto diverse others and therefore excluded these from his own life. In all three cases there was a victim at whose expense the humour was had, someone who was humiliated or offended by it. This is congruent with Freud's (1960) statement that tendentious jokes require a person as the object of hostility. In the third case the individual leader underscored Grotstein's (1999) analytic description of humour in the paranoid-schizoid position as mocking and sarcasm.

The three case studies provided insight into humour as an unconscious defence against the anxiety experienced in diversity settings. Basic assumption defences include the splitting off of the parts different from the self, followed by the denial of its existence to avoid shame (because of the failure to do what is expected (Mollon, 2004), namely to include all people as a democratic activity) and its associated feelings of weakness. This is followed by guilt in response to the felt harm done to the other. In order to cope with social difficulty, reaction formation (Blackman, 2004) is used by turning the situation into something humorous for the self. As such the humour becomes a potential space (Diamond & Allcorn, 2009) where the system lives between the fantasy of uniting the group in humour to avoid the pain (Schulman, 2010) and the reality of the anxiety created by the shame and guilt.

The research hypothesis is formulated as follows: tendentious humour is used to relieve the anxiety experienced by groups in diverse settings. This defence can at most provide temporary relief, since the cause of the anxiety originates from the group's basic assumption functioning. Humour, which manifests itself in diverse settings, should therefore be observed and interpreted by diversity consultants to provide significant opportunities for awareness around the cause of anxiety towards inclusion and community building.

The conclusion was made that through the investigation and understanding of the nature of humour in diversity contexts, significant evidence exists that destructive humour is used to split, avoid and deny the anxiety around difference and to avoid community building. When consultants bring this dynamic into awareness, the group is offered the opportunity to explore these dynamics and thus integrate their unconscious fears into their group functioning.

It was recommended that human resources professionals, Organisational Development (OD) consultants and psychologists working in diversity settings, should be aware of the dynamic significance of manifesting humour. The humour may not be innocent and deeper exploration may be useful towards uncovering covert dynamics.

A limitation of the research was that the case studies were not recorded as case studies at the time, but taken from cryptic professional notes and reconstructed into case studies. Thus, some of the content of the sessions may have been lost. Further, two of the case studies were based on the functioning of the group, whereas only one was based on the functioning of the individual. More of the same (either group or individual) may have provided much richer data.

It was suggested that future research should focus on more group cases, based on the systems psychodynamic assumptions that the micro system (individual) acts on behalf of the meso (group) and macro (organisational) system. It was also suggested that the CMB be explored in the application of more and varied diversity scenarios.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationship(s) which may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this paper.

Authors' contributions

O.C. (University of South Africa) was the project leader and performed the empirical work. F.C. (University of South Africa) was the supervisor of the project and assisted in the interpretations and academic editing.

References

Anderson, R. (Ed.). (1992). Clinical lectures on Klein and Bion. London: Routledge [ Links ]

Armstrong, D. (2005). Organisation in the mind. Psychoanalysis, group relations and organisational consultancy. London: Karnac. [ Links ]

Barron, J.W. (1999). Humor and psyche: Psychoanalytic perspectives. Hillsdale: Analytic. [ Links ]

Becvar, D.S., & Becvar, R. (2000). Family therapy: A systemic integration. New York: Allyn & Bacon. [ Links ]

Bion, W.R. (1961). Experiences in groups. London: Tavistock. http://dx.doi. org/10.4324/9780203359075 [ Links ]

Bion, W.R. (1970). Attention and interpretation. London: Tavistock. [ Links ]

Blackman, J.S. (2004). 101 Defenses: How the mind shields itself. New York: Brunner-Routledge. [ Links ]

Booysen, L. (2005, 23rd June). Social identity changes in South Africa: Challenges facing leadership. Inaugural lecture, Graduate School of Business Leadership, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa. [ Links ]

Brunner, L.D., Nutkevitch, A., & Sher, M. (2006). Group relations conferences: Reviewing and exploring theory, design, role-taking and application. London: Karnac. [ Links ]

Campbell, D. (2007). The socially constructed organisation. London: Karnac. [ Links ]

Campbell, D., & Groenbaek, M. (2006). Taking positions in the organisation. London: Karnac. [ Links ]

Campbell, D., & Huffington, C. (2008). Organisations connected. A handbook of systemic consultation. London: Karnac. [ Links ]

Carr, A. (2004). Positive psychology: The science of happiness and human strengths. New York: Brumer-Routledge. [ Links ]

Cashdan, S. (1988). Object relations therapy: Using the relationship. New York: Norton. [ Links ]

Chamberlayne, P., Bornat, J., & Apitzsch, U. (2004). Biographical methods and professional practice. An international perspective. Bristol: Policy Press. [ Links ]

Chasing the rainbow. (2006). The Economist, April 06. Retrieved January 09, 2007, from http:/www.Economist.com. [ Links ]

Cilliers, F. (2007). A systems psychodynamic exploration of diversity management. The experiences of the client and the consultant. South African Journal of Labour Relations, 31(2), 32-50. [ Links ]

Cilliers, F., & Koortzen, P. (1996, September). The psychodynamics of organisations. Paper presented at the 2nd annual PsySSA Congress at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. [ Links ]

Cilliers, F., & May, M. (2002). South African Diversity Dynamics: Reporting on the 2000 Robben Island Diversity Experience: A group relations event. South African Journal of Labour Relations, 26(3), 42-68. [ Links ]

Cilliers, F., & Smit, B. (2006). A systems psychodynamic interpretation of South [ Links ]

African diversity dynamics: A comparative study. South African Journal of Labour Relations, 30(2), 5-18. [ Links ]

Clarke, S., & Hoggett, P. (2009). Researching beneath the surface. Psycho-social research methods in practice. London: Karnac. [ Links ]

Coetzee, O. (2007). Exploring interpersonal and inter-group diversity dynamics in South African organisations by means of a theoretical model. Unpublished D Com Thesis. University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa. [ Links ]

Colman, D., & Geller, M.H. (Eds.). (1985). An A.K. Rice Institute series group relations reader 2. Jupiter: A.K. Rice Institute. [ Links ]

Creswell, J.W. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]

Czander, W.M. (1993). The psychodynamic of work and organisations: Theory and applications. New York: Guilford. [ Links ]

Denzin, N.K., & Lincoln, Y.S. (Eds.). (2005). The Sage handbook of Qualitative research (3rd Edn.) Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]

Diamond, M.A., & Allcorn, S. (2009). Private selves in public organizations. The psychodynamics of organisational diagnosis and change. New York: Palgrave. [ Links ]

Elion, B., & Strieman, M. (2002). Clued up on culture: A practical guide for all South Africans. (2nd Edn.). Camps Bay: One Life Media. [ Links ]

Foster, A., Dickinson, A., Bishop, B., & Klein, J. (2006). Difference: An avoided topic in practice. London: Karnac. [ Links ]

Fraher, A.L. (2004). Systems psychodynamics: The formative years of an interdisciplinary field at the Tavistock Institute. History of Psychology, 7(1), 65-84. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1093-4510.7.1.65, PMid:15025060 [ Links ]

Freud, S. (1960). Jokes and their relation to the unconscious. London: W.W. Norton. [ Links ]

Grotstein, J.W. (1999). Humor and its relationship to the unconscious. In J.W. Barron (Ed.) Humor and psyche: Psychoanalytic perspectives (pp. 61-93). Hillsdale: Analytic Press. [ Links ]

Halton, W. (1994). Some unconscious aspects of organisational life. In A. Obholzer & V.Z. Roberts (Eds.), The unconscious at work (pp. 11-18). London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Hinshelwood, R.D., & Skogstad, W. (2005). Observing organisations. Anxiety, defence and culture in health care. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Holstein, J.A. & Gubrium, J.F. (2005). Interpretive practice and social action. In N.K. Denzin & Y.S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of Qualitative research (3rd Edn.) (pp. 483-505). Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]

Huffington, C., Armstrong, D., Halton, W., Hoyle, L., & Pooley, J. (2005). Glossary. In C. Huffington, D. Armstrong, W. Halton, L. Hoyle, & J. Pooley (Eds.), Working below the surface: The emotional life of contemporary organizations (pp. 223-229). London: Karnac. [ Links ]

Huffington, C., Armstrong, D., Halton, W., Hoyle, L., & Pooley, J. (Eds.). (2005). Working below the surface: The emotional life of contemporary organizations. London: Karnac. [ Links ]

Klein, L. (2005). Working across the gap. The practice of social science in organisations. London: Karnac. [ Links ]

Klein, M. (1997). Melanie Klein: Envy and gratitude and other works 1946-1964. London: Vintage. [ Links ]

Lawrence, W.G., Bain, A., & Gould, L. (1996). The fifth basic assumption. London: Tavistock. [ Links ]

Lemma, A. (2000). Humour on the couch: Exploring humour in psychotherapy and everyday life. London: Whurr. [ Links ]

Martin, R.A. (2007). The psychology of humour: An integrative approach. London: Elsevier. [ Links ]

Maier, C. (2002). Leading diversity - a conceptual framework. Bamberg: Difo-Druck. [ Links ]

McCormick, D.W., & White, J. (2000). Using one's self as instrument for organisational diagnosis. Organisational Development Journal, 18(3), 49-62. [ Links ]

McRae, M.B., & Short, E.L. (2010). Racial and cultural dynamics in group and organisational life. Crossing boundaries. Los Angeles: Sage. [ Links ]

Mollon, P. (2004). Shame and jealousy. The hidden turmoils. London: Karnac. [ Links ]

Morgan-Jones, R. (2010). The body of the organisation and its health. London: Karnac. [ Links ]

Morreal, J. (1983). Taking laughter seriously. Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press. [ Links ]

Obholzer, A., & Roberts, V.Z., (Eds.). (1994). The unconscious at work. London: Routledge [ Links ]

Patton, M.Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods. (2nd Edn.). Newbury Park: Sage. [ Links ]

Pick, I.B. (1992). The emergence of early object relations in the psychoanalytic setting. In R. Anderson (Ed.), Clinical lectures on Klein and Bion (pp. 24-33). London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Pretorius, M. (2003). An exploration of South African diversity dynamics. Unpublished M.A. dissertation. University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa. [ Links ]

Rosenwald, G.C. (1988). A theory of multiple-case research. Journal of personality, 56, 239-264. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1988.tb00468.x [ Links ]

Sandigo, C.A. (1991). Theories and models in applied behavioural signs. Vol 2: Group. New York: Pfessen. [ Links ]

Schulman, L. (2010). Dynamics and skills of group counselling. Belmont: Brooks/Cole. [ Links ]

Stake, R.E. (2005). Qualitative case studies. In N.K. Denzin & Y.S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of Qualitative research (3rd Edn.). (pp. 443-466). Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]

Stapley, L.F. (2006). Individuals, groups, and organizations beneath the surface. London: Karnac. [ Links ]

Stokes, J. (1994). The unconscious at work in groups and teams: Contributions from the work of Wilfred Bion. In A. Obholzer & V.Z. Roberts (Eds.), The unconscious at work (pp. 19-29). London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Tellis, W. (1997). Introduction to case study. The qualitative report, 3(2). Retrieved March 31, 2011 from http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR3-2/tellis1.html. [ Links ]

Terre Blanche, M., Durrheim, K., & Painter, D. (2006). Research in practice. Applied methods for the social sciences. Cape Town: UCT Press. [ Links ]

Thelen, H.A. (1998). Reactions to group situations test. [CD-Rom]. The Pfeiffer Library, 12(2), 133-135. [ Links ]

Turquet, P.M. (1985). Leadership: The individual and the group. In D. Colman & M.H. Geller (Eds.), An A.K. Rice institute series group relations reader 2 (pp. 71-87). Jupiter: A.K. Rice Institute. [ Links ]

Vansina, L.S., & Vansina-Cobbaert, M. (2008). Psychodynamics for consultants and managers. From understanding to leading meaningful change. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. [ Links ]

White, K. (2006). Unmasking race, culture, and attachment in the psychoanalytic space. What do we see? What do we think? What do we feel? London: Karnac. [ Links ]

Yin, R. (1994). Case study research: Design and methods (2nd Edn.). Beverly Hills: Sage. [ Links ]

Correspondence to:

Correspondence to:

Frans Cilliers

PO Box 392, UNISA 0003,

South Africa

Email: cillifvn@unisa.ac.za

Received: 31 May 2011

Accepted: 24 Oct. 2011

Published: 19 Mar. 2012