Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

Cited by Google

Cited by Google Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.32 n.3 Pretoria Jan. 2012

ARTICLES

Girls' career choices as a product of a gendered school curriculum: the Zimbabwean example

Edmore MutekweI; Maropeng ModibaII

IDepartment of Education Studies, University of Johannesburg, South Africa edmorem@uj.ac.za

IIDepartment of Education Studies, University of Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The unequal distribution of boys and girls in certain subjects studied at school and its consequent unequal distribution of men and women in the occupational structure suggest some failure by schools and teachers to institute adequate measures to ensure learning equity. In this study we sought to unmask factors in the Zimbabwean school curriculum that orient girls into not only pursuing different subjects at school, but also following careers in fields traditionally stereotyped as feminine. The study was qualitative and utilized an exploratory case study as the design genre. Data were collected through classroom and extra-curricular observations and focus group discussion sessions (FGDS) with girl pupils. A sample size of 40 participants comprising 20 sixth form school girls and 20 teachers was used. These were purposively sampledfrom four schools. To analyse data we used simple discourse analyses. The main findings of this study were that gender role stereotypes and the patriarchal ideology communicated through the hidden curriculum reflected teachers' attitudes and influence that contributed to girls' career aspirations and choices.

Keywords: career-aspirations; choice; gender-typing; girls; hidden-curriculum; ideology; learning-equity; occupation; patriarchy; Zimbabwe

Introduction and background to the study

Feminist authors such as Kwinjeh (2007) and Gordon (2004) have voiced concerns about the marginalization of women in the social, economic and political spheres in Zimbabwe. The views of the aforementioned authors resulted in some positive strides in women's fight for equal recognition to their male counterparts. Legislative reforms such as the Legal Age of Majority Act of 1987 and the Matrimonial Causes Act repealed in 2008 were consequently enacted to recognize women's rights to own property independent of their husbands or fathers (Kwinjeh 2007), and to recognize them as adults who could vote, open bank accounts and even marry should they choose to, none of which was possible without the consent of a male affiliate: brother, father or uncle (Gordon, 2004). After challenging their physical abuse at the hands of men, the Zimbabwean parliament also passed the Domestic Violence Act of 2008, which deterred men from physically harming women (Mawarire 2007). Some women gender activists have been jailed and tortured for peacefully participating in protest marches against the gender discriminatory tendencies of this patriarchal society (Kwinjeh 2007), which has resulted in some of them temporarily losing the courage to oppose the prevalent restrictive authority of the ruling party. Despite these reforms, women remain marginalized in a number of areas within society, thus affecting their education and career aspirations.

Goals of the study

The goals of the study we report on herein were (i) to explore factors in the school curriculum that promoted gender role stereotypes and so informed the career aspirations and choices for girls and boys; and (ii) to better understand how teacher attitudes and expectations influenced, specifically, the girls' career aspirations. The hope was that a better understanding of the aforementioned would provide insights to draw on in future attempts to reform curricula aimed at achieving equal gender recognition and treatment.

Problem statement

Even though Zimbabwean schooling is structured to provide education that fosters freedom or autonomy to all pupils by offering subjects and equipping them with skills deemed necessary for them to take charge of their own destiny, this structure and the curricula offered within it restricts girls' career choices. Despite having received what is purported to be one of the best education systems on the African continent (Zvobgo, 2004), the stereotyping interferes with their choice of school subjects, occupational choices and, in general, their life chances.

Research questions

The study was guided by the following research questions: What factors contribute to gender role stereotypes in the Zimbabwean school curriculum? What motivates the career aspirations and choices made by girls in Zimbabwe? How do teacher attitudes and expectations influence girls' career aspirations?

Literature review

Drawing from Blackledge and Hunt's (2005) assertion that every theoretical effort is like a building block that is added to other blocks to build a house, the literature review in this study was conducted in an eclectic way, drawing from, amongst other things, a range of theoretical perspectives including feminist and cultural reproduction theories.

Gender, education and pupils' career aspirations: a feminist view

According to Kwinjeh (2007), Mawarire (2007) and Gordon (2004), gender equity issues have not received adequate attention in Zimbabwe studies. Very little attention has been given to what happens to girls within the school walls (Machingura, 2006). Research has mainly focused on equality of access to schooling for girls and, more recently, factors contributing to their high dropout rate from schools. For example, Gordon (2004), Atkinson, Agere and Mambo (2003), Gaidzanwa (1997), Jansen (2008) and Nhundu (2007) focus on curricular trends from the pre- to the post-independence era. Atkinson et al. (2003), Gaidzanwa (1997) and Jansen (2003) view colonial history as having left an indelible political, economic and educational legacy. The school curriculum inherited post-independence Zimbabwe was modelled on the English system (see also Wolpe, 2006), with Zimbabwean girls being educated for domesticity whilst boys were prepared for employment and the role of family head and breadwinner. Boys and girls were taught different practical and vocational subjects, boys having to study technical subjects such as metalwork, woodwork, agriculture, technical graphics and building, and being encouraged to pursue science subjects, whilst girls were offered domestic science subjects and typing and shorthand, and being encouraged to pursue the arts subjects.

Based on this, Atkinson et al. (2003) have argued that the colonial settler officials tended to view girls and women in terms of the Victorian image of what a woman should be, instead of recognizing actual abilities to function alongside their male counterparts. Men were consi- dered to be breadwinners and needed to be exposed to technologies and jobs that paid more and were highly esteemed. These jobs often took them away from homes, farms and rural areas, then called 'tribal trust lands'. The trend continued with the expansion of the market economy with men migrating to work in the mines, plantations and towns. Even land settlement schemes gave title deeds to men only, which meant that they had automatic rights to the proceeds of the land that included products of women's labour. It is in this sense that the colonial period is viewed as having laid the foundations for unequal educational and career aspirations between males and females and thus unequal access to economic sustainability (cf. Zvobgo, 2004). Concerned with this legacy, Gordon (2004) has argued that equality of educational opportunity should involve not only equal access to schooling but also equal treatment of boys and girls within the school and classrooms (Gordon 2004). Also in Chengu's (2010) view, equality of access without social justice for girls and women fails to address the gender imbalance. Therefore, in spite of the Zimbabwean education system's claim to be liberative, it has remained conservative, discriminatory and oppressive, especially to girls and women in matters of career choices.

The hidden culture curriculum theory and career aspirations

The views of Gordon (2004), Jansen (2008) and Machingura (2006) on the relationship between the school curriculum and career choices in Zimbabwe are based on Burrow's (2005) notion of the hidden culture curriculum. In his view, regardless of forms the curriculum takes, its content is often presented to pupils in a manner that emphasises their gender role differences. As a result, boys and girls receive different messages in school, so schooling fails to afford girls opportunities for competing on an equal footing with their male counterparts and influences education, career aspirations and choices (see also Christie, 2008; and Wolpe, 2006).

The cultural transmission theory (Sunstein, 2005) is invaluable in explaining this point further, as from birth to death the social environment points to boys and girls or men and women being different. Life thus promotes conformity with cultural definitions of behaviour and obligations associated with masculine and feminine roles. Individuals acquire ways of thinking, feeling and acting characteristic of such roles through their social experiences, most notably enculturation practices passed on across and within generations (Momsen, 2008). Boys and girls thus develop different and polarized roles that limit the horizons of the latter by locking them into a gender-stratified occupational world.

Curriculum, social class and career choices: a reproduction theoretical view

According to Bourdieu (2008), a lack of familiarity with the dominant culture (cultural capital) and the absence of the proper disposition that typically comes from such familiarity (habitus) serves as a barrier for academic achievement and career aspirations and choices, especially for girls or youth from the low socioeconomic status (SES) backgrounds. For him, various actors in schools value certain cultural characteristics, which are conveyed through speech, attitudes, behaviour, knowledge, and other interactions in the school environment. A relevant cultural capital thus helps youth to develop the proper habitus to navigate the education system and establish clear-cut career aspirations. Conversely, youths from low-SES backgrounds are often not exposed to what is necessary to build relevant cultural capital and are therefore placed at a disadvantage as regards school and career aspirations. Schools reproduce inequalities based on SES because teachers, principals and the occupational world reward displays of dominant culture, which often translate into high educational achievement and ambitions (see also Sianou-Kyrgiou & Tsiplakides 2009).

Methodology

The study was an exploratory case study to examine in-depth a curriculum that is assumed to be determining girls' career aspirations and choices (cf. Stake 2000; Yin 2009) and to highlight the issues that predispose them to career trajectories traditionally stereotype as feminine. The girls' were observed during lessons and involved in focus group discussions (FGDS) in which elements of their school culture were observed as the discussions unfolded, eliciting factors that impinge upon the girls' education and career prospects. The observations were followed by FGDS in which the girls' views on school culture were sought and probed to obtain their understanding of its influence on their career aspirations and choices.

Sampling

A purposive sample of 40 participants, comprising 20 teachers and 20 sixth-form girls drawn from four schools in the Masvingo province of Zimbabwe was used. The district was chosen because it is well placed to provide insights from girls belonging to diverse socio-economic backgrounds. As one of the industrialised provinces, its population consisted of a variety of classes that provided a cross-section of girls whose career aspirations and choices were explored. This made sampling purposive (cf. Odimegwu, 2000; Fayisetan, 2004).

Data collection methods

The study was conducted for two months. Its duration was influenced by the time of the year we were allowed into schools. It was a time just before the commencement of the year-end examinations, during which time we could not collect more data without disrupting the students. This proved an opportune time as the sixth-form girls were consciously thinking of what to do after graduating from their schools. Through the FGDS we were able to engage them in ways that enabled us to collect data that proved useful to answer the questions we had posed. The participant classroom observations and FGDS we used facilitated an in-depth understanding of the messages conveyed to the girls in lessons and the meaning they attached to them (see Merriam, 1998, on the significance of process, context and discovery when probing a phenomenon). The methods are discussed in greater detail here.

Classroom observation

The role of the researchers was that of overt participant ob servers who interacted with the participants for two months. The observations were used to gain close and intimate familiarity with the interactions between teachers and their pupils. There was intensive involvement with them in the classrooms and schoolyard. Participants were thus observed in action in the classroom and during general extra-curricular activities in the school.

The approach was informed by a key principle of this method, requiring us to observe and identify a role in which to partake (Fayisetan, 2004). We watched teacher-pupil interactions that is both verbal and visual behaviour, and noted physical characteristics during lessons. These observations involved listening and recording the verbal interactions for later reflection and transcription, as well as looking at structures and patterns in the social interaction between teachers and girls. To understand these interactions it was important to look at them as reflecting the school culture in which they occurred (Fayisetan, 2004). Anecdotal and running records were also used. In order to ensure that the observations remained focused, a guide was used as part of the advance protocols. Classroom interactions were not recorded since doing so would have had unpredictable effects on participants (Odimegwu, 2000). However, field-notes were made.

Focus group discussion sessions (FGDS)

Focus group discussions with girl pupils from the four schools were given an opportunity to answer, comment, and ask questions to other participants or to respond to questions and comments made by others. Each of the four focus groups of between 6-12 members was interviewed four times for the purpose of enhancing constant reflection on the girls' own and other views. It also ensured the validity of the design used in the study by establishing it as a tool for obtaining credible data (cf. Krefting, 2007). Each interview session was for an average of 90 minutes to enable sufficient coverage of the focus group discussion items and give each girl a chance to express a view (see Appendix A). A structured interview guide (Appendix B) was used to ensure that the participants dealt with the same questions and issues. FGDS were used to capture the group dynamics and to allow a small group of girls to be guided by the researchers into increasing levels of focus and depth on key issues that needed to be discussed (Odimegwu 2000). The open conversations helped us to obtain data that clarified the attitudes, motivations, concerns and problems related to how girls chose their careers (see also Dzvimbo, Moloi, Potgieter, Wolhuter & Van der Walt, 2010; Fayisetan 2004).

Data analysis

Data analysis involved adopting simple content and discourse analyses of participants' interaction patterns and conversations emerging from classroom observations and FGDS. The analysis also included a study of a couple of text books and the wall charts displayed in the classrooms. Discourse analysis is concerned with the ideological effects of language constructions (Fairclough, 2003) and how texts contribute to establishing, maintaining and changing social relations of power, domination and exploitation (Foucault, 2006). It thus works on the assumption that individuals construct the world to make sense of it whilst reproducing or challenging ideological systems of beliefs that exist in society. In this study it was used as a lens though which to identify the gender biases characteristic of the Zimbabwean school curriculum and explore how the ideological biases embodied in this curriculum influence girls' career choices upon graduating from schools.

Walum (2008), a discourse analyst, contends that language usage is the chief vehicle that makes social interaction possible and provides an ideal illustration of the cultural transmission process. Language contains many explicit messages regarding cultural definitions of male and female roles. In the English language, for example, women are included under the rubric 'man'. Elaborating on the impact of language in communicating gender or sexual inequalities between females and males, he notes that it is through discourse communication that much of the pattern of sexist interaction is engendered and perpetuated. Discourses have been used in the past and are still being used to dehumanize a people into submission. Such discourses reflect and shape the cultural context in which they are embedded. Discussing sexism in the English language, Nilsen (2000), also a discourse analyst, contends that sexist discourse takes three language forms, namely, ignoring, defining and deprecating. In discussing these language effects, Nilsen employs a chicken metaphor which summarizes a girl's life course:

"In her youth the girl child is a chick, and then she marries and begins feeling cooped up, so she goes to hen parties where she cackles with her friends. Then she has her brood and begins to henpeck her husband. Finally she turns into an old biddy" (Nilsen, 2000:109).

The above quotation shows that in a patriarchal society language, use or discourses have an enormous impact in subordinating girls and women to the patriarchal ideologies and values embedded in their social structure.

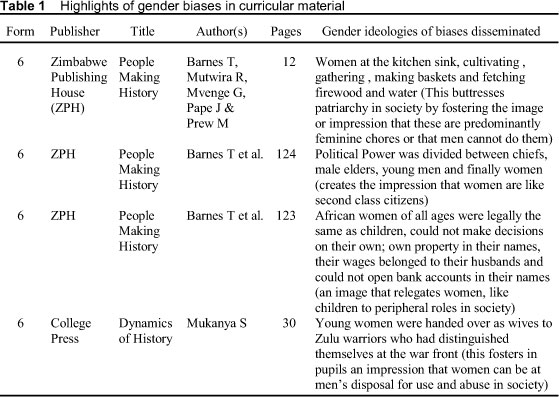

Discourse analysis was guided by Fairclough's (2003) notion of discourses as transcending language to encompass ways of interacting and believing. Following the data coding process, patterns of emerging issues were identified for interpretation and reduced into discernible themes for analysis and discussion. Fairclough's conception of discourse analysis as both a method and theory was thus useful in identifying elements of the gender and patriarchal ideologies embedded in the school curricula. Discourses were conceived of as texts encompassing both the spoken and written modes of communicating for disseminating cultural beliefs, ideologies, values, stereotypes and prejudices (cf. Table 1). Discourses were considered as occurring at three levels: action, representation and identification and as social practices at the personal, social and professional levels (cf. Table 1).

Ethical considerations and measures for ensuring trustworthiness

The instruments for data collection (observations, FGDS and discourse analysis) were first piloted with a group of teachers and pupils from schools in the same province that the study was conducted, but in a different education district so as to guarantee their authenticity (Lincoln & Guba, 2002). The pilot study thus ensured their transferability to different schools in the province and their dependability could not be doubted (Krefting, 2007), as the differences amongst the schools, teachers and student populations within the Masvingo province proved insignificant when the main study was conducted. The patterns of interactions and attitudes within schools were generally characteristic of prevalent cultures within the province amongst the different classes within society. The presentation and analysis of the data that follows confirms this.

The observations and focus group interviews were initiated by clarifying the purpose of the research and reassuring teachers and their pupils of their rights in the study (Maphosa & Shumba, 2010; Meintjes & Grosser, 2010), especially their right to withdraw from the study at any moment as well as the confidential nature of the observations and responses made through the study. None of the participants withdrew however. Informed consent had been sought and obtained from the Department of Education and the necessary ethical clearance granted for the research as part of the advance protocols.

Findings and discussion

The following is a discussion of the research results of observations, FGDS and the discourse analyses conducted for this study, presented according to emerging themes, which are clustered under headings that link with the main questions that steered the study, namely, factors that contribute to gender role stereotypes; the influence of teacher attitudes and expectations and factors that motivate career aspirations and choices made by girls.

Factors that contribute to gender role stereotypes

It emerged from the classroom observations that in virtually all the four sixth-form classes observed boys received more teacher-initiated contact than their female counterparts. This prevalence of patriarchy and the gender role ideology in co-educational schools was manifest or evident in that boys were asked more questions than girls and they contributed more during class discussions. Also, the boys received not only more feed-back from their teachers but also more attention. In a follow-up FGDS question asking participants whether or not they felt teachers were fair in their treatment of boys and girls in the school, thirteen out of the twenty girl respondents confirmed what we had witnessed during the lessons, namely that boys were more favoured by the teachers. The following verbatim statements were made by three of the participants and supported by the majority of the girls as a response to the above question:

Participant 1 (P1): Teachers think that boys know better than us and as a result they tend to pose more questions to them.

P2: Sometimes you hear a teacher saying, 'boys please do not be as quiet as girls in classes'. To us this clearly shows that boys are encouraged to be more vocal than us girls in the school and classroom. A girl who tries to stand her ground and compete with boys is called all sorts of names just to discourage her.

P3: The surprising thing is that even female teachers ridicule girls who want to compete with boys. They even go to the extent of dressing her down by such comments as 'you reason like a boy' or ridicule her through remarks like, ' if you continue behaving like a boy, you may never get married as if to say marriage is all that matters for us girls' The participants' views expressed above represent some of the in-school factors that engender and perpetuate patriarchy and lead to the polarization of gender role aspirations in society. These results or findings are consistent with those reported by Whyte, Deem and Cruickshank (2002) in a study of secondary teachers in Birmingham, where they discovered that generally teachers (both male and female) preferred to teach boys because they were more active, outspoken and willing to exchange ideas than the girls.

The lesson observations also revealed gender bias in curricular materials, in particular, charts displayed on the walls and textbooks sampled from the classrooms for observation. The charts portrayed men and women in traditionally gender stereotyped occupations. In the analysed curricula material the central characters embodied were overwhelmingly masculine. Where women and girls did appear, they were portrayed as weak, soppy creatures, bearing little resemblance to real life females. Women were generally wearing aprons, cooking and looking after children. The responses emerging from the FGDS and lesson observations also revealed that among the sources of gender role stereotypes and the patriarchal values and prejudices are the sexist biases embodied in the school curriculum (cf. Table 1). For instance, the constant portrayal of women in traditional feminine roles: at the kitchen sink, with babies on their backs or cooking, created in learners the impression that not many women engage in paid work outside the home.

The girls' response to FGDS questions 6, 7, 8, and 9 (Appendix B) revealed that discourses have an impact on girls' career aspirations and choices. The following verbatim statements from participants confirm the above view:

P4: 'When our mathematics teacher was giving out our test scripts yesterday he commented to one of the girls (name given) saying, you did very well in a boys' subject, I hope you do not neglect girls' subjects such as home economics, which is a girls' subject.'

These findings correspond well with those of McRobbie (1982) who, in her analysis of the adolescent magazine, Jackie, discovered the ways through which adolescent femininity was constructed and upheld. The findings corroborate Walum's (2008) assertion that discourses disseminate messages regarding cultural definitions of male and female roles and contribute enormously to the social construction of gender and sexual inequality between females and males. We interpreted the portrayal of women and girls as evidence of how some of the curricular material used in schools disseminated patriarchal ideologies and values to learners. Table 1 highlights some of the portrayal of males and females in some of the curricular material used in Zimbabwean schools.

The images reflected, disseminated and buttressed the patriarchal ideology embodied in the curriculum. As a follow up to the observations we posed questions to FGDS participants on whether or not they felt the educational material they used in schools contained gender-neutral content and illustrations. They were unanimous in their responses that negative stereotypes about girls were rampant in their school curriculum, and alleged that teacher attitudes and expectations compounded the negative stereotypes about girls.

P5: Many teachers in our school think that girls should aim to become nurses, teachers and hoteliers. One can tell this from their comments, language and actions when dealing with boys and girls. When one looks at our text books, the bulk of the diagrammatic illustrationsfor people show girls and women in jobs associated with child rearing while boys and men are often depicted in more challenging jobs as if to say we cannot also do it.

These findings are consistent with those of Meyer (2008), who found that patriarchal values embodied in the school curriculum disadvantages girls as a whole. The results also support Bourdieu's (2008) assertion that through the school curriculum boys generally have access to an array of educational goodies, relevant culturally but systematically denied to girls.

The influence of teacher attitudes and expectations

Our observations and analyses of the discourses employed by teachers during their interaction with learners revealed that the discourses inherent in the teachers' attitudes and expectations about appropriate gender roles for boys and girls compound the effects of the educational literature discussed above. Responding to the FGD question on whether or not girls felt that their teachers had anything to do with the fate of girls who sometimes drop out of school, the girls' answers were generally in the affirmative, with 12 out of 20 concurring. The following verbatim statement by one of the participants attests to the above view:

P6: When a girl is absent from school some teachers joke with that saying has she gone to get married as if marriage is all that matters to us. In some situations you hear a teacher deliberately saying, if you find school work challenging, why don't you get married and look after the home?. Such comments send wrong messages to some girls, no wonder why there are more girls than boys dropping out of this school.

Responding to the question of whether the participants felt that boys and girls should follow the same subjects (question 5, Appendix B), 11 answered in the affirmative, saying that girls and boys were different and should thus pursue different subjects.

P7: As a girl I think subjects like Fashion and fabrics, Home economics and Biology are good for me because through them I am able to study things related to my duties as a woman. I should be able to sow and cook for my husband and children when I get married. With biology, I should be able to manage my health and that of my children, for example I must not reproduce children like a goat. I need to know about family planning and the like.

P8: Boys can study technical subjects and other sciences because they must know that they are the husbands and breadwinners who should earn more since they have to support their wives and children in the home. The above quoted responses confirm assertions of the cultural reproduction and transmission theories that from birth to death our social environment tells us that boys and girls or men and women are different, as social life dictates that they conform to cultural definitions that point to the behavioural expectations and obligations associated with masculine and feminine roles (Sunstein, 2005).

Probed to state whether there are subjects they consider to be better suited to boys or girls (question 6, Appendix B), 15 participants concurred that for them subjects like Mathematics and pure sciences (Physics, Chemistry and Biology) should fall in the masculine category, while the feminine category should include those such as Home Economics, Humanities and Typing. It was thus clear that, as in the texts we examined, teachers also tended to categorize academic subjects as either feminine or masculine, a practice described by Gordon (2004) as gender typing. We interpreted the above observations to imply that what was learnt at school depended on the ideologies about gender that are embedded in the curriculum in both its explicit and hidden forms.

With follow-up questions to probe pupils on what subjects they were studying, who normally helped them in the choice of subjects at the advanced school level, and whether they were treated the same as their boy counterparts when choosing subjects (questions 1, 2 and 7, Appendix B), elicited responses revealed that through the gender typing of subjects, schools channel learners into polarized occupational trajectories they ultimately follow. This idea is evident in the following statements given by some of the participants:

P9: Our teachers, both males and females advise us that subjects like Home economics, Biology and Tourism are especially ideal for girls. They advise boys to study technical graphics, physics and maths saying as boys they will eventually become men and therefore should not compete with girls on the jobs. They must follow different and challenging occupations.

These perceptions of gender roles are often accompanied by prejudicial and biased teacher attitudes and expectations, resulting in a sustained pattern of occupational disadvantage for girls, a pattern so complex that it seems intractable to those who might initiate changes in the system.

To establish the ways through which the school curriculum orients learners toward specific careers, we posed questions about the subjects studied; the jobs they wished to do upon graduating from school; and the reasons for their aspirations. The majority, 16 out of the 20 girl participants expressed an interest in the traditional female dominated careers: teaching, cosmetology, hotel and catering, and pharmacy. Not surprisingly, we also noted strong links between the subjects studied by the girls and their anticipated careers, with only four participants arguing in favour of the more male-dominated careers, such as engineering, technology and ICT. The reasons cited for such career aspirations included their families' influences, society's attitudes towards marriage, and how tasks are allocated to girls and boys in the home and school. Fourteen cited a desire not to be away from children and the home, thereby reflecting values instilled in them through gender socialization. These results corroborated Machingura's (2006) contention that although gender awareness campaigns may be under way in other spheres of society, very little attention might be given to what happens to girls within the school walls especially through the hidden curriculum of the school. The following statement captured from one of the participants' responses evidences this view:

P10: What we girls go through in school and what our parents expect us to be when we leave school give us direction as to what careers to pursue in our world of work.

Responding to question 12 on what pupils feel needs to be done to mitigate the effects of gender biases in the school curriculum and promote learning equity, the following statements represent the participants' views on the subject:

P11: Teachers need to be retrained in matters of gender neutrality so that they become part of the solution not to exacerbate the problem of gender inequality in schools.

P12: Our parents and older siblings also need to be aware that things are changing and therefore there is no need to cling to some of these ancient beliefs about appropriate gender roles for girls or boys.

P13: Our teaching and learning material needs to be relooked into with a view of eradicating gender biases, stereotypes and prejudices, which tend to promote male domination all the way.

Asked about the kind of treatment girls received in the school and classroom in comparison to boys particularly in the allocation of roles, participants of the FGDS expressed dissatisfaction with the way sexist discourses were peddled by their teachers and boys in the school. The classroom discourses revealed that teachers' beliefs about the feminine role as primarily domestic and the belief that men should be the providers and heads of families influenced their perceptions and treatment of girls. The examples of discourses captured during lesson observations are listed below:

Teacher 1 (T1): I wonder why you chose this subject (Accounting) leaving out subjects like Shona and English which are easy subjects for girls of your calibre.

T2: You boys surprise me. How can you allow these two girls to beat you in Mathematics, which is known to be a male subject? Why didn't you go for History, Divinity or English Literature and join other girls (implying that they were girls too).

T 4: As a woman I have to prepare you for one of the inescapable roles you will take in life. Biology is particularly usefulfor you as girls so that you learn about your bodies and to avoid sex and pregnancy. For you boys, it is useful for your jobs if you decide to become doctors, gynaecologists (class laughs uproariously). And you girls too, can become nurses.

The above responses indicate that not only were teachers disseminating their stereotypical gender role biases but also expectations for their pupils. The prevalence of gender biases and discriminatory practices were also noticeable in the interaction of teachers and pupils during the extra-mural activities where hockey and netball were strictly deemed feminine-only sports and cricket and rugby masculine domains. As revealed by the FGDS, school subjects such as Mathematics were dominated by boys, with the ratio to girls being 3 to 1. The FGDS also revealed that in the Arts and Humanities subjects, girls tended to outnumber boys by 3 to 2. This trend seemed to justify Mutekwe's (2007) call for a paradigm shift in the Zimbabwean school curriculum towards gender sensitivity.

Factors that motivate career aspirations and choices made by girls

Responding to the questions on how tasks are allocated to boys and girls in their schools (questions 8 and 9, Appendix B), the girls' responses clearly revealed that in addition to streaming pupils on the basis of school subjects, teachers also used gender as a basis for their allocation of different tasks to boys and girls. These tasks included what teachers themselves perceived to be gender-appropriate roles for boys and girls. At one school, boys were observed ferrying bricks to the new library construction underway, while girls were observed sweeping classrooms. Many teachers also encouraged girls to join clubs such as cookery, drama and dance as part of their co-curricular activities. They encouraged boys towards activities deemed masculine: karate, boxing, gymnastics, aerobics and judo. These findings confirmed Walker-dine's (2006) assertion that the school as a structure serves to engender and reinforce society's gender polarized role expectations and career aspirations for children.

It also emerged from the FGDS and observations that fewer women than men in Zimbabwe teach in the sciences subjects. Neither do many men teach such subjects as Home Economics, Shorthand or Typing. Three of the principals in the schools studied were male, while only one school was headed by a woman. It became clear to us that the participants were being educated in an environment in which men dominated in exercising power and authority. It also became apparent that the ratio of female to male teachers in leadership positions in many schools did not offer girls enough role models or inspiration. The situation in the four schools studied epitomized the level of gender inequality and stratification characteristic of many social institutions in Zimbabwe. It corroborated Gordon's (2004) assertion that although schools in Zimbabwe may offer girls and boys equality of access and choice to education, girls still opt for those subjects perceived as feminine and traditionally stereotyped as such. It was also clear from both the FGDS and observations made that the decision taken by girls to study or not to study a particular subject is often influenced by factors other than whether or not it is offered to them as part of the school curriculum. These factors relate to both societal and school culture and include the ways in which school subjects are gender-typed. Even when the formal curriculum does not differentiate between boys and girls, the hidden curriculum tends to influence girls to make particular choices.

Despite the efforts being made towards gender sensitivity in the curriculum, as evidenced through the informal discussions held with teachers that as part of their initiatives towards learning equity they constantly remind their pupils that there are no differences in the performance of boys and girls in all school subjects, the evidence in this study did not attest to this claim. These observations clearly pointed to the need for educators to create an equitable learning environment (Tabane & Human-Vogel, 2010) in order to overcome the divisions caused by the gendered nature of the school curriculum.

Conclusion

The study has shown that what teachers and pupils consider as appropriate roles or occupations for men and women have an impact on the girls' aspirations or career prospects. Teacher attitudes and expectations of their pupils' gender roles influence to a large extent the career trajectories girls eventually follow. The results of the study also attest to the view that the school, as one of the modern apparatuses of social regulation, not only defines what shall be taught and what knowledge is, but also defines and regulates both what a girl or boy pupil is and how learning and teaching are to be considered for him or her. It does so by an ensemble of apparatuses, from the architecture of the school, teacher attitudes, and expectations of gender roles as well as their treatment of pupils, to the individualized work cards and wall charts in the classrooms. This study has revealed that some curricular material or literature needs to be reviewed in order to deconstruct the gender role stereotypes, ideologies and values embedded in them.

Recommendations

In the light of the findings of this study, the following recommendations are made: Teachers need to play an important role in closing the ranks and gaps created by the gender role stereotyping experienced by pupils in the home and those incorporated in textbooks and reinforced by the hidden curriculum of the school. Understanding both the overt and covert ways in which gender ideologies operate and are manifest in the school curriculum is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for alleviating the effects of gender inequality and promoting learning equity. The curriculum needs to be gender sensitive or balanced as opposed to being gender blind to the plight of girls and women if it is to empower girls to be on an equal footing with boys and to compete for equal opportunities in life. Because early aspirations formed as a result of gender role socialization ultimately affect the gender balance of higher education programmes and of the workforce, promoting gender parity from the earliest levels of schooling is critical. We hope that our study will draw attention to this important issue and bring Zimbabwe closer to achieving the gender equity to which it aspires.

References

Atkinson N, Agere T & Mambo M 2003. A Sector Analysis of Education in Zimbabwe. Harare: UNICEF. [ Links ]

Blackledge D & Hunt B 2005. Sociological Interpretations of Education. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Bourdieu P 2008. Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture. Beverly Hills: Sage. [ Links ]

Burrow R 2005. Common Sense and the Curriculum. London: Allen and Unwin. [ Links ]

Chengu G 2010. Indigenization must empower women. Zimbabwean, 16 December, 14-16. [ Links ]

Christie P 2008. Changing Schools in South Africa: Opening the Doors of Learning. Johannesburg: Heinemann. [ Links ]

Dzvimbo P, Moloi C, Portgieter F, Wolhuter C & van der Walt C 2010. Learners' perceptions as to what contributes to their school success: A case study. South African Journal of Education, 30:479-480. [ Links ]

Fairclough N 2003. Critical Discourse Analysis: The critical study of language. Edinburgh Gate: Longman. [ Links ]

Fayisetan K 2004. 'Focus Groups'. Paper presented at Qualitative Methods Workshop, Tanzania: Ifakara, April 2004. [ Links ]

Foucault M 2006. The order of Discourse. In R Shapiro (ed.). Language and Politics. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. [ Links ]

Gaidzanwa R 1997. Images of women in Zimbabwean literature. Harare: College Press [ Links ]

Gordon R 2004. Educational Policy and Gender in Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe Journal of Educational Research, 13(8):10-18. [ Links ]

Jansen J 2008. What education Scholars write about Curriculum in Namibia & Zimbabwe. In W Pinar (ed.). International Handbook of Curriculum Research. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Keller R 2005. Analysing discourse. An approach from the sociology of Knowledge [33 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research [On-line Journal], 6(3): Art 32. Available at: http://www.qualitativeresearch.net/fqsteste/3-05/05-3-32-e.htm. Accessed 27 October 2005. [ Links ]

Krefting L 2002. Rigor in qualitative research: the assessment of trustworthiness. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 45:214-222. [ Links ]

Kwinjeh G 2007. Male authority disbanded: Understanding opposition politics in Zimbabwe. Journal of Alternatives for a Democratic Zimbabwe, 1(2):16-17. [ Links ]

Lincoln Y & Guba G 2002. Establishing Trustworthiness. In A Bryman & R Burgess (eds). Qualitative Research. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Machingura V 2006. Women's access to teacher education: a gender profile. Zimbabwe Bulletin of Teacher Education, 13(2):21-34. [ Links ]

Maphosa C & Shumba O 2010. Educators' disciplinary capabilities after the banning of corporal punishment in South African schools. South African Journal of Education, 30:387-390. [ Links ]

Mawarire J 2007.Locating women and the feminist discourse in Zimbabwean transitional politics. Journal of Alternatives for a Democratic Zimbabwe, 1(2):10-11. [ Links ]

McRobbie A 1982. Working Class Girls and the Culture of Femininity, in Women's Studies Group, Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies, Women take Issue. London: Hutchinson. [ Links ]

Meintjes H & Grosser M 2010. Creative thinking in prospective teachers: the status quo and the impact of contextual factors. South African Journal of Education, 30:361-363. [ Links ]

Merriam S 1998. Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education. San Francisco: Jossey Bass. [ Links ]

Meyer A 2008. "Cultural particularism as a bar to women's Rights: reflections on women's gender roles in an African society." British Journal of Education, 30(6):31-34. [ Links ]

Momsen J 2008. Gender and Development: Routledge perspectives on development. London: Taylor & Francis. [ Links ]

Mutekwe E 2007. The teachers' role in the de-construction of gender role stereotypes and in promoting gender sensitivity in the school curriculum. Zimbabwe Journal of Educational research, 14(1):13-33. [ Links ]

Nilsen H 2000. Using the chicken metaphor in child developmental progressions. Journal of Social Psychology, 13(6):64-67. [ Links ]

Nhundu T 2007. Mitigating gender-typed Occupational Preferences of Zimbabwean Primary school Children: The Use of Biographical Sketches and Portrayals of Female role models. Sex Roles, 56:639-649. [ Links ]

Odimegwu C 2000. Methodological issues in the use of focus group discussions as a data collection tool. Journal of Social Sciences, 4:207-212. [ Links ]

Sianou-Kyrgiou E & Tsiplakides I 2009. Choice and social class of medical school students in Greece. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 30:727-737. [ Links ]

Stake R 2000. The Art of Case Study Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]

Sunstein C 2005. Cultural transmission theory and its enculturation effects on children's development of social roles. Journal of Sociology and Anthropology, 16:27-31. [ Links ]

Tabane R & Human-Vogel S 2010. Sense of belonging and social cohesion in a desegregated former house of delegates school. South African Journal of Education, 30:491-493. [ Links ]

Walum E 2008. How discourses communicate attitudes and cultural expectations in society. The Anthropologist: International Journal of Studies of Man, 9:91-94. [ Links ]

Walkerdine V 2006. School Girl Fictions. London: Verso. [ Links ]

Whyte J, Deem R & Cruickshank N 2002. Girl Friendly Schooling. London: Methuen. [ Links ]

Wolpe A 2006. Education and the Sexual Division of Labour. In A Kuhn & A Wolpe (eds). Feminism and Materialism. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Yin R 2009. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Newbury Park: Sage. [ Links ]

Zvobgo R 2004. Reflections on Zimbabwe's search for a relevant curriculum. The Dyke Journal, 1:70-79. [ Links ]