Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

Cited by Google

Cited by Google Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Yesterday and Today

On-line version ISSN 2309-9003

Print version ISSN 2223-0386

Y&T n.7 Vanderbijlpark Jan. 2012

ARTICLES

History in Senior Secondary School CAPS 2012 and Beyond: A comment

Peter Kallaway1

Emeritus Professor, University of the Western Cape Associate Researcher, University of Cape Town peter.kallaway@uct.ac.za

ABSTRACT

History Education has been a neglected aspect of the great educational debate in South Africa in recent times. Despite its high profile in anti - apartheid education the subject has not received the same attention as science and maths in the post 1994 debates, and was to a large extent sidelined by Curriculum 2005 and OBE reforms because of the emphasis on constructivist notions of knowledge which devalued formal historical learning. Although partially rescued by Asmal's reforms in the Revised National Curriculum Statement (RNCS) of 2002, it has taken the CAPS curriculum of 2010-2011 to put it back at the centre of the educational picture by recognising the importance of history as a key aspect of the worthwhile knowledge to be offered at school. This article looks at the new CAPS curriculum for senior school (Grades 10-12) and recognises its value but also turns a critical eye to question the credibility of the new curriculum in terms of knowledge criteria and pedagogic viability.

Keywords: History Education; Curriculum development; South Africa; Historiography; Teacher knowledge; Pedagogy; CAPS.

Introduction

During the 1990s the new South African government introduced "the most radical constructivist curriculum ever attempted anywhere in the world." (Taylor 2000 cited by Hugo 2005: 22) which was intended to complement the new post-apartheid constitution. It integrated different disciplines, their learning areas, education and training, knowledge and skills, "with all the intention of creating a transferability of knowledge in real life"(Hugo, 2005: 22). For all its Progressive resonance and radical innovatory signals, the curriculum of the 1990s was for the most part a pot pourri of curriculum proposals with largely unacknowledged origins that can be traced from Dewey to Freire. Some of the discourse was drawn from People's Education and various worker education projects that were a distinctive product of the community and trade union struggles of the 1980s. Added to this there was the influence of the National Qualifications Framework (NQF) and the American educationalist Spady's notion of Outcomes Based Education (see Christie & Jansen, 1999) In much of this there was a strong reliance on notions of constructivist curriculum design which had enjoyed a resurgence at that time, emphasising the virtues of learning from the social context and the immediate environment of the learner. There was an emphasis on the relevance of local knowledge.

These proposals, which were aimed at providing a constructivist alternative to apartheid education, represented a direct challenge to more orthodox notions of curriculum and pedagogy which relied on conventional structures and traditions of knowledge by "making clear the content, sequencing, pacing and assessment requirements within strongly differentiated subject boundaries." (Hugo, 2005:23) The rejection of the apartheid education curriculum was confused with the abandonment of a curriculum that was based on historically constructed knowledge. Apartheid education was characterized in terms of formal knowledge; the new curriculum was presented as an oppositional project. As Jansen (1997) and others pointed out at the time, these proposals failed to engage with "what the conditions of possibility were for the elaboration of the new curriculum dream."(Hugo, 2005:28) The ideas that underlay this romantic view of radical curriculum reform ignored the crucial work of Gramsci in the 1930s which had warned against the notion that radical working class knowledge could be conceived of as something different in kind from traditional academic or modern scientific knowledge. He argued strongly that general public education should provide "a historicizing understanding of the world and of life," which could only be obtained through traditional academic pursuits. (Hugo, 2005:31; Gramsci, 1971; Entwistle, 1979). As Michael Young has pointed out with regard to curriculum innovation in the UK in recent years, whatever the pedagogical merits of the progressive, or technical-instrumentalist view of curriculum, the radical progressive proposals give "scant attention to the nature of knowledge, or to "the cognitive and pedagogical interests that underpin the production and acquisition of knowledge" which gives such knowledge "a degree of objectivity and a sense of standards." (Young, 2008: 33, cited by Roberts, 2010: 8).

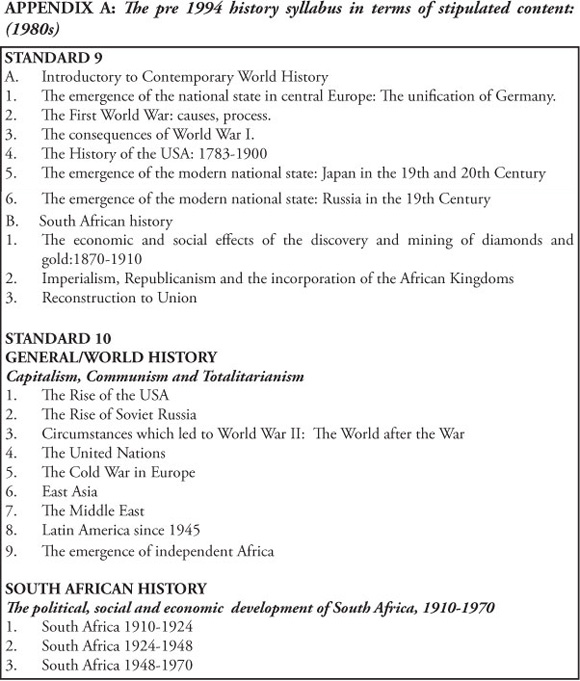

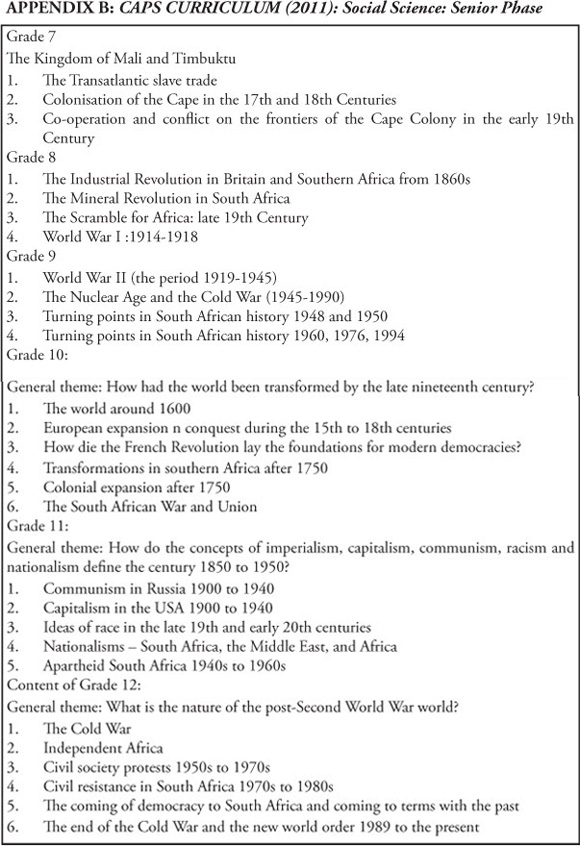

Since the unveiling of Curriculum 2005 in 1998 there has been a strong response to it and a gradual recognition of the limitations of the various forms of proposed curriculum development (Jansen, 1997); (Christie & Jansen, 1999); (Kraak & Young, 2001); (Hoadley, 2011); (Hugo, 2005); (Young, 2008). Most significantly there has been a concerted attempt to challenge the epistemological foundations of the reforms. There is not sufficient space here to engage with that whole curriculum reform process between 1994 and 2011 - namely the NATED 550 exercise (1996), the Revised Curriculum Statement (NCS, 2006), and the new CAPS: Grade 10-12: History curriculum of 2011. The focus here will just be on the most recent iteration of that curriculum, with some brief references to the comparisons with the pre 1994 syllabus (see Appendix A).

The Issues

By 2010 - 11 the weaknesses of the new curriculum and the critique levelled against it gave rise to the new National Curriculum Statement (NCS), Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement, (CAPS) that was released for Grades 6 - 9 in 2010 and for Grades 10 - 12 in 2011. A key element of the revision has been the return to notions of curriculum disciplinarity in the secondary school history curriculum with a new history curriculum (CAPS Grades 10-12: Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement: HISTORY) representing a return to forms of knowledge that experienced teachers would find more familiar. (It has to be noted that the process by which that change took place remains obscure and calls for further careful research)

By comparison to the focus on literacy and numeracy or science and maths in the years since 1994, very little of that debate has focussed specifically on the area of history education. There has been very little research on the apartheid history curriculum or a clarification of what was at fault and what needed to be changed. The only initiative directed at this general area was Kader Asmal's Values and Education policy statement and campaign in 2001 which was only partially related to the area of history education (DOE, 2001). Chisholm (2005), Bertram (2008, 2009) and Sieborger (2011) have been the only significant contributors.

An adequate review of the global context of history in schools at the present time is beyond the scope of this paper, but it is important to note that there is a degree of concern about a decline in popularity of the subject, attributable to the changing culture of globalisation and the market economy (Judt, 2009; Tosh, 2008). The significance of the study of History in Education has been underscored by the recently published report by David Cannadine and associates under the auspices of the Institute of Historical Research in the UK where the subject has been under pressure in the schools (Cannadine, 2011). In that context there has been considerable argument in favour of the teaching of history in schools and a reconsideration of the role of history in education. Christine Counsell, also writing about history education in the UK, notes that "bringing an epistemic tradition to the pedagogical site so that pupils can understand the grounds on which valid claims about the past can be made will never be easy" (Counsell, 2011:202), but she argues that good history teaching does foster thinking, reflection, criticality and motivation. Thus there is little need for these skills to be introduced through constructivist strategies designed to promote generic critical thinking.

In that context, and in the best of history teaching in South Africa since the 1970s, history teachers have been aiming to develop student understanding of the distinctive properties of this form of "disciplinary knowledge as a mechanism for exploring issues of similarity and difference; change and continuity and cause and consequences." They have pursued these ends by the use of teaching strategies that are driven by notions of "the active and engaged exploration of the structure and forms of historical knowledge, using concepts and attendant processes." (Counsell, 2011:207-217).

Much of the confusion about the nature of reform in history education seems to stem from approaches which confuse information or content with knowledge in the wider sense elaborated above (Roberts, 2010:7). In the South African case a key element of the reforms proposed for history was that they were to replace rote learning (associated with Christian National Education and Bantu Education) with critical thinking. That juxtaposition of content-based learning - "learning or memorizing the facts" - with critical and analytical thinking, radically misrepresents the issues at stake. Critical understanding and learning in history is arrived at through an interrogation of the narrative, the events, or the evidence related to various interpretations of events. The habits of critical thinking are therefore arrived at through an understanding of the interaction between that narrative or the understanding of events and the ability to pose the right question when engaging in historical explanation.

Although the learning of history in school during the apartheid era is usually associated with rote learning and indoctrination, this only represents part of the picture. There had for a long time been a tradition in South African history education which challenged those assumptions. In the Joint Matriculation Board (JBM), Natal and Indian education versions of the national curriculum and assessment practices, specific reference was placed on the ability of students to critically engage with a question and demonstrate a range of skills specifically associated with history (HSRC Report, 1992).

Counsell's cautionary warning about the difficulties of teaching history as an academic discipline at school in the form proposed is of course to be taken seriously. To teach history well at the level we are addressing is an extremely demanding task that requires considerable expertise, resources and commitment by teachers and students. It also requires that the teachers do not only have pedagogic teaching skills in the conventional sense, but that they are able to bring the "epistemic tradition" of history to the classroom in forms and under conditions that will allow for meaningful learning to take place and enable students to gain access to this valuable means of understanding and interrogating the world.

Although many history teachers are very pleased to see the return of a credible history curriculum to the secondary school, on closer examination I am disturbed by the limitations of the new document and the lack of attention to key aspects of its credibility with regard to formal academic knowledge and the pedagogical value or implementability of these proposals in the classroom. Given the lack of research regarding a critique of the apartheid education history curriculum, and the clear shortcomings of the curriculum process regarding history since 1994, the new curriculum statement still seems to demonstrate a degree of confusion about what history teaching at secondary school should entail, how content should be selected and assessed, what it is precisely that is being reformed, and what its objectives should be in a context where we need to give teachers much more clarity about the goals of history teaching. As commentators on the curriculum process unfolding here, we need to know a lot more about the process by which this was conducted and the criteria for the investigation. Who decided on the need for a curriculum revision and on what grounds? Who was consulted in the process?2 How did the consultation take place and how were the investigators and drafters of the new curriculum chosen?

In summary, the CAPS document very competently sets out a table of skills to be promoted which emphasise the distinctive nature of historical knowledge and the means for its promotion. But I am concerned that the actual framing of the curriculum and the organisation of the content presents very significant obstacles to the achievement of these goals for a majority of teachers.

In short, I think that the CAPS History Curriculum for Grades 10-12 is far too ambitious in terms of the factual content to be covered, the conceptual targets for the students, and the demands on the teachers. My approach to these complex issues will be to focus on two key aspects of the process of history curriculum development. Firstly, the process of content knowledge selection and historiographical perspective, and secondly, the pedagogical issues relating to the level of capacity required in terms of teacher ability and resource availability to achieve the ends proposed.

Curriculum selection

One of the issues that concerns me is that there are unstated principles of selection at play regarding content knowledge which are influenced by the notion that history in the classroom should be tied to the principle that it "demonstrate the current relevance of the events studied." (CAPS: History Grades 10-12:10) This would seem to imply an unacceptable presentism. We would need much more clarity on what this means and how it is to be effectively put into practice since the whole enterprise of OBE was based on such presentist principles and has been found to be lawed in many ways. Although the new curriculum makes considerable advances by reasserting notions of historical disciplinarity, it often tends to ignore complexity and context and reverts excessively to narrow notions of race and nationality in what appears to be a quest for 'relevance'. If we are to be able to effectively assess the engagement of students with this field of study we must be able to understand precisely what effective learning would amount to i.e. to understand precisely how assessment would work and what the relationship is between history education and civic education (Kallaway, 2010). Another issue to be highlighted is that the lack of chronological continuity means that students can easily be disorientated and fail to make the kinds of linkages that are required. The search for "relevance" in the selection of content has dangers when events are ripped out of due sequence - something that is the hallmark of historical studies. This leads to students "thinking in bubbles" (Tosh, 2008:4) and insufficient awareness of the links between the contextual and structural issues and the events being studied, or adequately linking international and local events.

Level of capacity

One of the greatest flaws of the Curriculum 2005/OBE proposals was the lack of capacity in terms of person power, skill and resources to carry out the elaborate curriculum plans it required. The knowledge capacity, or ability of the majority of teachers to drive the curriculum goals and their ability to engage effectively with the complex pedagogical requirements of implementing this curriculum, was often questionable. The lack of historical training at advanced levels of many teachers and the limited access to library and resource materials in schools and communities compounds the problem. There is little awareness in the curriculum of what used to be called "the psychological aspects of history education," namely the need to shape the curriculum to suit the cognitive level of the students. Bertram found in her research, reported in 2009, that there was a lack of capacity of teachers even in advantaged schools to translate the pedagogical goals into practice (Bertram, 2009:57- 60). All of these issues need to be taken into account once again when assessing the appropriateness of the CAPS initiative.

These issues will now be discussed in more detail.

Knowledge and the Curriculum

Of utmost relevance to an understanding of the issues raised here is a question of what precisely should be happening in the history classroom if effective teaching and learning is to take place. It is quite fundamental to grasp the essentials of this issue if curriculum development is to proceed with any degree of professional confidence. There seems to be wide acceptance of the negative consequences of content memorization and of rote learning in the history class as in other curriculum areas. But there does not always seem to be a good grasp of what an adequate and creditable alternative would be in the history class. What is it that the teacher should be doing? What kinds of learning should be promoted? What skills are central to the task? What should the students be learning? How do we select an appropriate mix of skills and content? What are the criteria for content selection? And what knowledge and skills are necessary on the part of the teacher if this process is to be managed in an educationally credible manner? What modes of assessment are appropriate? Above all, who should be involved in the process of curriculum reform? It seems to me that much of this is only dimly grasped in policy discourse and educational practice and it is essential to investigate whether the CAPS Curriculum for history manages to capture these issues in ways that do justice to history education.

The CAPS Grades 10-12 History document makes a commitment to promoting 'history as a process of enquiry" but it seems that the process of content selection is strongly influenced by another stated goal - the commitment to the study of history as a means of "support for citizenship within a democracy" (Section 2:8).

A specific issue mentioned in this regard is citizenship education: upholding the values of the South African constitution and helping people to understand those values; reflecting the perspective of a broad social spectrum so that race, class, gender and the voices of ordinary people are represented; encouraging civic responsibility and responsible leadership, including raising current social and environmental concerns; promoting human rights and peace by challenging prejudices that involve race, class, gender, ethnicity and xenophobia, and preparing young people for local, regional, national, continental and global responsibility."

It is not clear from the document how these goals are to be reconciled with the more traditional goals of history education. These have been defined in various ways. In CAPS the aims of teaching history are to promote "an interest in and the enjoyment of the study of the past", the imparting of "knowledge, understanding and appreciation of the past and the forces that shaped it." The introduction to "the study of history as a process of enquiry" and the promotion of "an understanding of historical concepts," is acquired through coming to understand the nature of "historical sources and evidence." (Specific Aims: 2.2:8) The concepts to be emphasised (2.3.2) in the promotion of historical knowledge are: cause and effect; change and continuity; time and chronology; multi-perspectivity; historical sources and evidence.

A key question to ask concerns what is and what is not engaged with in 2.1: "What is history?" What seems to be missing in the description of the project is any reference to the essence of historical studies: a reading and interpretation of an existing body of literature in the field of historical studies in the light of the available evidence (historiography - the politics of historical writing). This refers to knowing what interpretations have been presented in the past by the major scholars in the field. That exercise should also identify the overarching issues which shape the architecture of the study and need to be considered in interpreting historical change, issues such as the political, social and economic forces and processes, or the context that needs to be understood. Students need to understand by doing what historians do: to a large extent to balance the weight of explanation by weighing the influence of the interpretations of major scholars in the specific time and context under discussion. Such a vision shapes the context of historical studies and puts into place a background for understanding more specific explanatory conceptual markers such as race, class, ideology, human rights, gender, etc. To attempt to teach history without attempting to engage with that background seems to put in question the whole legitimacy of the enterprise.

The history curriculum and the history class have long been at the centre of the debate about the nature of education in South Africa. In particular the question of historiography, namely what version of history is presented in the curriculum, the textbooks, the 'matric' examination papers and by the teachers, has been a key to political debate about education throughout the twentieth century. Although we still lack anything like an adequate account of the history of history in South African schools, everyone who studied school history in pre-apartheid times will remember debates about British colonial versions of South African history, and in apartheid times much heat was generated about bias in the curriculum in favour of Afrikaner nationalist interpretations (Van Jaarsveld, 1964; Auerbach, 1966; Dean, et al., 1983). There is also very little recognition of the fact that the history taught in schools was revised at various times during the apartheid era. The curious path of history in schools after the introduction of Curriculum 2005 and Outcomes Based Education, and through the reforms of the Schools History Project of Minister Kader Asmal, has still to be critically assessed in detail in relation to these issues of historiography and bias.

CAPS (Grades 10-12 History: Section (2.4:10) refers to the "rationale for the organisation of the content and weighting." The focus of my comment below refers primarily to this issue. We are told that "a broad chronology of events is applied in Grade 10 - 12 content, from the 17th Century to the present." It is not at all clear to me what this means. There is no clear statement regarding the criteria for selection of the topics chosen, e.g. key organising themes, issues, links, barring a reference to the need for balance and "interconnectedness between local and world events." There is also a statement about the Grade 10 content being "reorganised more logically" -whatever that might mean. In summary there is a commitment to ensure that 'learners gain an understanding of how the past has influenced the present' and the key question for FET is: "How do we understand our world today?" (2.4:10) According to CAPS it would seem to be a fundamental principle that "in teaching history it is important to demonstrate the current relevance of the events studied."(2.4:10) This is an issue that has long been contested in discussions about the goals of history teaching and raises the question of the role of civic education and its relationship to the history curriculum. This would seem to be a possible but not a necessary condition for good history teaching and it might even be a dangerous yardstick by which to judge all classroom practice. Is effective history teaching to be judged by these criteria of relevance, or by the quality of the understanding developed in relation to the specific goals set about above for history education? How is the teacher to interpret this discourse and these instructions?

The Content

My first concerns relate to the manner in which the content has been selected. The return to a specified content will be valued by those who have argued against the constructivist curriculum form and for a discipline-based curriculum, but the manner in which that content has been selected, and the fragmented manner in which it is presented, represent a cause for serious review. As in the pre 1994 South Africa history curriculum, there is no clear statement of why this content was selected rather than any other. Tosh has remarked with regard to the new English history curriculum that the "constant switching from one topic to another means that the students do not learn to think historically. They fail to grasp how the lapse of time always places a gulf between ourselves and previous ages... and to understand that any feature of the past must be interpreted in its historical context." He concludes that "instead of emerging from school with a sense of history as an extended progression, students learn to 'think in bubbles'." (Tosh, 2008:4). It seems that this comment could be aptly applied to our own CAPS curriculum and I will attempt to demonstrate below what I mean by this.

The CAPS rationale for the organisation of "the content and weighting" (CAPS, 2011, 2.4:11) makes reference to: "Key questions used to focus each topic." These are stated as follows:

A. "questions convey that history is a discipline of enquiry not just received knowledge." It would seem that it is necessary to spell out more carefully what this means.

B. "historical knowledge is open-ended, debated and changeable." This would seem to imply that such debate is simply a matter of subjective opinion and argument. There should be a rider to this comment which states that this is "subject to the knowledge/evidence/approaches engaged in by historians"?

C. "history lessons should be built around the intrigue of questions". There is no indication of what "the intrigue of questions" might mean or how these questions might be arrived at. What are good and bad questions? How do we decide? What are the criteria?

D. "research investigation and interpretation are guided by posed questions." I would suggest that this is misguided as historical questions are not just the result of "posed questions"; they are guided by the state of research in the field which gives rise to such questions. This is a key section of the document which needs careful revision and elaboration for teachers, as there is abundant evidence from long experience that teachers simply fall back on content delivery and rote learning where they are unable to interpret the topic or the period in a critical manner.

All this is highly complex and there are few easy solutions to the issues raised, but these seem to be the key issues to be kept in mind when evaluating a new curriculum for South African schools which claims to encourage critical thought and the promotion of democratic citizenship. I am essentially in agreement with Carol Bertram regarding her concerns that the new CAPS curriculum is a question of "Rushing Curriculum Reform Again" (Bertram, 2011). I am concerned that we have failed yet again to achieve an adequate and clear statement of the objectives for history education in our schools that manages to capture the need to "bring the epistemic tradition of history to the classroom in forms that allow the students to understand the grounds on which valid claims about the past can be made." (Counsell, 2011:202). By so doing we are still undermining the credible teaching and learning of this subject in the classroom and thereby depriving young people of access to the fundamental educational skills that are potentially available to them though access to this mode of enquiry. The question of how to assess student achievement in the field is directly related to these shortcomings.

Although CAPS has rescued history as a knowledge discipline from the clutches of OBE, it still seems to me to hold older apartheid era ideas that the essence of the curriculum is to impart various content(s) to "learners" in order to teach some kind of, usually unarticulated, though implied, LESSON. A hidden curriculum! This is clearest with regard to the goals of civic education articulated in 2.1 as spelt out previously. Those objectives are framed in terms of the study of the virtues of the constitution, 'promote civic responsibility', encourage an awareness of 'current social and environmental concerns,' challenge prejudiced thinking, and promote global responsibility.'" But the relationship between the promotion of those civic goals and "learning to think about the past, which affects the present, in a disciplined way" as part of "a process of enquiry" is not made explicit.

It might be argued that selection is a necessary condition of historical practice and curriculum content choice. As EH Carr pointed out years ago, the notion of "objective history" is a myth (Carr, 1961). If selection is necessary or inevitable, should we seek to be more explicit about the "lessons" we wish history to teach? If we agree that we cannot teach "objective" or "value free" history, it seems that, for our practice to be educationally credible, we need to be explicit about the pedagogic goals. We have tried, to our cost, to leave this issue to teachers to decide, based on the romantic assumptions of constructivist knowledge. Such degrees of subjectivity and random selection leads to a complete loss of coherence in terms of the practices and conventions of the formal study of history.

Given the complexity of the issue, and the centrality of selection as an issue in the process of planning or revising a curriculum, it seems of crucial importance to understand how this selection of the CAPS curriculum content was made and by whom and how it is justified? The curriculum reveals a return to subject knowledge specification. That knowledge is selected in very particular ways with, for example, an emphasis on the conflict between capitalism and communism; the significance of African history; the role of race and racism in history etc. Whether such selection is to be justiied or not needs to be understood within the context of longstanding history curriculum debates and scholarship internationally. These questions were central to our challenges to the apartheid era history curriculum. Should the same question not be given salience at the present time in the context of history education in a democratic South Africa?

The lack of contextual sequence is also a key concern (e.g. how are students to engage meaningfully with the history of nationalism in South Africa, the Middle East and Africa (Grade 11: 4) or Independent Africa (Grade 12:2) without careful attention to the background to the rise of nationalism in the nineteenth century Europe and the post-War world? How are they to understand the Cold War (Grade 12:1) without having a background to the politics of the inter-war era and the origins of World War I and World War II? This tendency to isolate certain topics that seem to offer the prospect of "relevance" arises from neglecting to take into consideration the difficulties of shaping the content and the themes without careful regard to the state of the discipline itself. In the desire to focus on skills and concepts there still seems to be insufficient focus on the contemporary literature of historical studies. What is not sufficiently emphasised is that the study of history at school needs to be carefully aligned with, and to take proper cognisance of, the state of the disciplinary knowledge in the area.

Another issue relates to the connections between world history and South African history in the new curriculum. In the section on "the rationale for the organisation of the content and weighting" (CAPS History: Grades 1012:10) a key issue seems to be "the comparative approach (which) reveals the interconnectedness between local and world events." This has long been a fundamental assumption of school history in South Africa. A return to this is to be applauded. But in the past this approach was often criticised because the two sections lacked any overt linkages. It is therefore necessary for the new curriculum to spell out with care the principles or criteria which inform such linkages. One seeks in vain for such clues.

The History Teachers

Further to these issues is the question of the teacher's role. Teacher background and familiarity with specific content is a necessary condition for effective teaching. This is no slight issue. It is the teacher's familiarity with and critical grasp of the key issues and dynamics of a particular era and set of issues and concepts that are the necessary conditions for effective historical learning to take place in the classroom. It is that understanding and insight that enable teachers to pose the appropriate questions and engage productively and effectively with students. With the best will in the world a teacher cannot teach effectively if he/she is not in control of the content and the knowledge that is to be engaged with. To put it in Wally Morrow's terms, the teacher needs to have epistemological access, namely, a comprehensive and critical engagement with the issues, concepts and contemporary relevance of issues if teaching and learning are to proceed effectively (Morrow, 1989). At universities we do not assume that a Latin American specialist is competent to teach Asian history; or that a social historian is competent in economic history, so why should we assume that a secondary school history teacher is automatically capable of teaching any topic that is prescribed by curriculum planners? (At the very least we surely need to investigate the competency of the teachers to engage in these tasks or to ensure that adequate and comprehensive support for them to be able to do so.) A key question for me is whether this key issue has been considered in the process of designing a new curriculum for our schools. Are the majority of our high school history teachers in a position to deliver on the task that is being required of them? Or, given the daunting nature of the task, will they just revert - as generations of history teachers have done in the past - to memorisation and rote learning, thus defeating the goals of the new system?

The new curriculum seems to characterise the teacher as a person who is competent to teach any stipulated historical content. The curriculum planners make decisions about what it is desirable to teach and the teachers simply carry out the mandate. This reasserts the role of disciplined knowledge in curriculum construction but it makes a lot of assumptions about the teachers and their levels of competence in the discipline. It can be more or less taken for granted that few have ever conducted historical research, yet the curriculum document seems to often assume a level of understanding of such processes. The assumption is that any history teacher can teach the history of Songhi or Latin America with the same depth, and with the same insight and critical engagement, as he or she would teach the history of Europe or South Africa in the nineteenth or twentieth century. There seems to be an assumption carried over from the earlier curricula since 1994 that "interesting themes" and foci can be selected or imagined by the curriculum planners and that the teacher will then be able to simply adapt to these themes with ease. Only with considerable effort in relation to continuing / in service education and the provision of appropriate teaching and learning support materials for teachers will these challenges be met.

In summary, teachers, the conveyors of the new curriculum, do not seem to have been considered by those compiling the curriculum which raises questions about the nature and inclusivity of the consultative process. They have not been given a history or considered in context. The reality is that, given the limitations of their own historical training, many teachers battle to get beyond reliance on the textbook and rote learning. In that context it is essential for the compilers of the new curriculum to ensure as far as possible that they follow a path that will enable all teachers to engage as effectively as possible with the new script by relating it to what they know and feel competent to teach? In parts of the curriculum this condition seems to have been kept in mind and there has been a degree of continuity. In other places many teachers would feel totally at sea and would find themselves in a situation where there would be little support material available in the school library (where there is one) or the local public library (where there is one), for example in relation to topics like those to be covered in Grade 10: Ming Dynasty, Songhi, Mughal, the conquest and history of Latin America, Southern Tswana kingdoms, Ndwandwe.

The converse point is simply that the areas of the curriculum that are more likely to be taught with some degree of confidence and critical engagement are those that have an established historiography and literature, and some continuity with past syllabuses. Such topics would have some degree of articulation with the knowledge teachers are familiar with. The topics which would have a better chance of being taught with relative competence are:

Grade 10:

Topic 2: European expansion and conquest during the 15th to 18th Centuries

Topic 3: The French Revolution

Topic 5: Colonial expansion (in South Africa) after 1750

Topic 6: The South African War and Union

Grade 11:

Topic 1: Communism in Russia 1900-1940

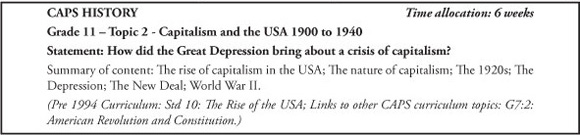

Topic 2: Capitalism and the USA 1900-1940

Topic 4: Nationalisms in South Africa the rise of Afrikaner nationalism the rise of African nationalism

Topic 5: Apartheid South Africa 1940s (presumably 1948 is meant) to 1960s

Grade 12:

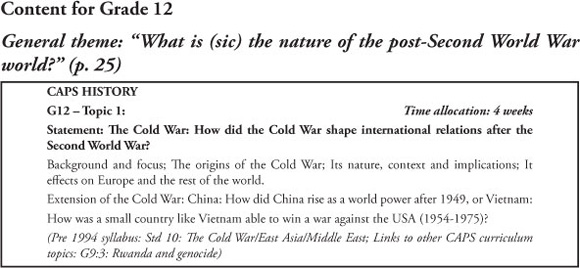

Topic 1: The Cold War

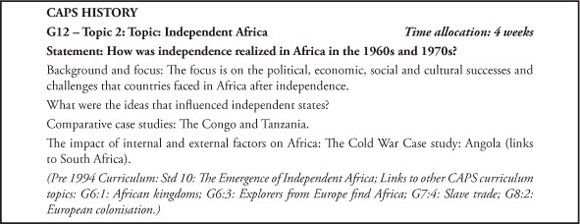

Topic 2: Independent Africa

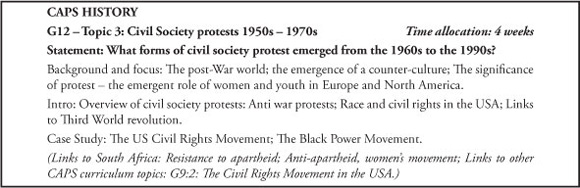

Topic 3: Civil Society protests 1950s to 1970s

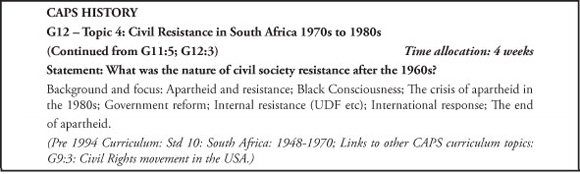

My intention below is to review the CAPS history curriculum for Grades 10-12 with the above reservations in mind. Due to lack of space I will only compare the content selection with the pre-1994 history curriculum and will not refer to the various articulations of the curriculum since 1994 related to Curriculum 2005 (1997) and the Revised National Curriculum Statement (RNCS, 2000).

Detailed comment on CAPS History Curriculum: Grade 10-12

The rest of this paper will attempt to engage with the above issues in the context of a detailed review of the CAPS History G10-12 document. Whatever the merits of the new CAPS history curriculum, can we be confident about the selection of content to meet the goals set out in 2.1 and 2.2, and about the promotion of skills as set out in 2.3.? Can we be confident that teachers as practitioners are able to understand fully and achieve the goals set for them in the guidelines for teaching? Are we not handing them a poisoned chalice in the form of an impossible task and then blaming them when they are not successful in achieving the ends that we demand? And what of our educational responsibility to the students?

Content for Grade 10

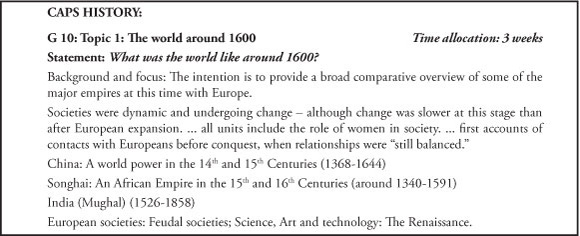

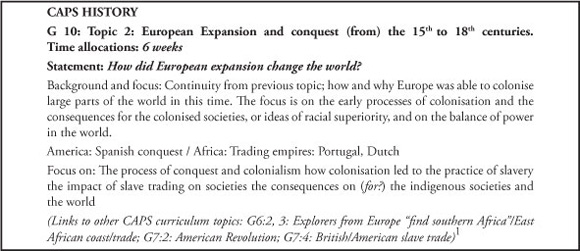

This is broadly in keeping with the general approach proposed, with three world history topics preceding the South African history and the chronology following sequentially (see Appendix B for CAPS Curriculum, 2011) Grade 10-12 and Appendix A for a statement of the 1980s History Curriculum for Standards 9 and 10, for purposes of comparison). I will first examine the content of the CAPS curriculum by giving an outline of what is stated in the CAPs document. Then comment with reference to the rest of the CAPS curriculum for earlier Grades (see CAPS: Social Sciences Senior Phase: Final Appendix B), and finally make brief references to the manner in which this topic was dealt with in the pre - 1994 history syllabus at this level (specifically in relation to Standards 9 and 10) (see Appendix A).

The early modern world is a difficult but coherent sphere of historical studies and the cross-over between world history and southern African history in the Grade 10 syllabus (Topics 4 and 5) makes a lot of sense. Another positive factor is that each of these topics has been well researched and have a coherent historical literature. (I doubt whether the injunction to compare these societies, 'assess their rates of change' (?) or engage with the role of women in each, is a realistic call.)

What disturbs me most is that from my knowledge of high school history teachers in South Africa, very few of them would have the necessary depth of knowledge to teach much of this material in a meaningful way that would go beyond textbook content coverage or rote learning. How many South African teachers have the knowledge or the resources to engage with China in the 14th and 15th Centuries, Songhai in the 14th and 15th Centuries, the Mughal empire or even early modern Europe? (The Renaissance era is a vast and complex field). How many of them would have studied these topics in the course of their training or even read a history of these Empires? The reality is that few public libraries have material on these topics so teachers will be reduced to teaching out of the textbook without alternative sources for the most part unless they are able to access Provincial Education libraries or make effective use of the Internet. This is not a promising context for stimulating interest and critical thinking about a key period of history that is intended to provide an introduction and gateway to historical studies at secondary level.

It is hard to imagine what teachers are going to make of the need for "broad comparative accounts of the empires" of the time, or the notion that "relationships were still balanced" or comments that "change was slower" in some areas. At the very least we could have asked for more careful editing in an official national curriculum document.

The focus here seems to be on the causes of these events. What were the key issues in European history that led to the age of discovery and what were the results? (This is not quite the same thing as "why European expansion was possible" (p. 14)). It is doubtful whether this topic can be taught meaningfully without a greater understanding of what was going on in Europe at this time i.e. without more background even if this was only to explore why slavery was an integral part of these economic developments. On the whole this seems to be a sensible section and would probably be able to draw on a degree of knowledge of teachers as one would assume that most teachers would have studied this at some stage in some form. Resources would also likely be available.

The focus on slavery is also sound given the degree of research on this topic, but the implication (message) of the curriculum seems to be that the sole consequence of colonialism was slavery and its negative consequences for African societies.

This anchor on European history is to be applauded and should provide a degree of continuity for good teachers with Topics 1 and 2. The focus on concepts of democracy and individual rights, the modern state and the transition from feudal to modern society is to be applauded. This is a topic that remains one of the anchors of the history curricula for South Africa. In the pre 1980s era it was dealt with in Standard 8.

Teachers would hopefully have some knowledge of the topic and materials would be easily available. The conceptual and disciplinary background would be familiar to most competent teachers. It provides an excellent backdrop to other themes to follow. There is high quality international historical published material on this and a variety of pedagogic materials are available.

These topics cover essential fields in South African history and provide a platform for careful analytical teaching. But I am puzzled about these two topics - How are they different? Is this an attempt to keep black and white history in separate compartments? Why? Recent historiography emphasises the unity of the processes of political and economic change at this time. What is the justification of returning to a racial/racialised version of South African history? At the very least it seems that the approach needs to be explained? More guidance on the thematic and/or conceptual anchors would also be useful.

There is a substantial amount of quality literature on the topics and many teachers would probably have a fair knowledge of Topic 5. (I am not so sure about Topic 4) Would it not be possible to ask for the coverage of ONE example of an African state in this period in the interests of manageability? An ample allocation of time for these topics is to be applauded.

This statement jumps to the explanation of broad historiographical debates, but it needs to begin by exploring the specific nature of the topic in its own terms. It emphasises the role of mining capitalism but British imperialism and the nature of the ZAR and the Uitlander question are hardly mentioned. Students need to be introduced to the historiography of debates on the topic to get a sense of how history is made and changed and how debates take place.

This topic is very similar to the pre-1994 curriculum. It is based on a sound historiography that raises fundamental question about South African history and there is a good chance that most teachers will be competent to teach it in a balanced and critical manner. It is logical and chronological and deals with causes and consequences in a way that students can understand. There is a good deal of material available on the topic. The conceptual underpinning is sound.

It would be helpful to spell out more carefully what it is that the students are expected to know on the completion of the topic and what is meant by the broad goal of understanding how the war shaped the politics of the 20th Century. If the goals of studying the topic (i.e. what is expected of teachers and students) lie beyond and outside of the boundaries of the topic itself, teachers need to know what it is that is expected of them in terms of these goals.

It seems that the pre 1994 syllabus title for this topic (see Appendix A) was more appropriate to the history curriculum since it is the history of Russia/USSR that is being studied not just the history of the "application of communism" under Lenin and Stalin." This is one instance among many in the curriculum where this feels like a political science course that investigates political systems and their application rather than a comprehensive account of all aspects of the historical situation. In this instance, it is not just the application of communism that interests historians but also the resistance to that process and how all of this has been part of a major historical developments and debates of the 20th Century.

On the positive side there is a strong narrative element to this section which allows teachers to build on the rich literature and materials available in the area and provides a background to the study of the Cold War that is to follow.

There was only one form of communism in the USSR after 1917 so it is not at all clear what the reference to "socialism and various forms or communism in the USSR" means.

This is a tried and tested topic in South African secondary school history and many teachers have a solid background in this, so it makes eminent sense to continue with this as it shapes our view of key events in the twentieth century.

The "Background and focus" begins by highlighting the contrast between this section and Topic 1. It incorrectly refers to the fact that students have "looked at socialism in the previous topic.."! This is not the case. The previous topic studied communism in the USSR; socialism was perhaps a by-product of that study but it can hardly be said that it represented a study of socialism. The curriculum seems to conflate the two concepts which seem to betray a radical misunderstanding of 20th Century history.

The topic has some merit from the viewpoint of relevance - but why the history of the USA should only be seen through the lens of a single concept is somewhat puzzling. The framing of the topic is based on a binary distinction between communism and capitalism, rather than paying attention to the actual history of the USA in its own right. And that is surely an essential issue in the study of history: to understand the uniqueness of historical events and the need to explain them in context. There is a lot to be said for a study of the USA between 1900 and 1940 as a way of framing an approach to the modern world and acquainting students with key themes in contemporary history. But I would be in favour of a less constrained curriculum than one which emphasises only "Capitalism in the USA." (Unless everything is identified as being a result of capitalism - in which case the usefulness of the concept disappears).

Again - the strength of this topic is that many teachers will have some background to these issues and many would have some background in academic study in the field. There are also many resources available at all levels. (In addition, the topic has a credible history in senior high school history going right back to the days of the Joint Matriculation Board.)

The rest of the topics for Grade 11 fail to qualify in terms of academic credibility and teacher familiarity with the content areas.

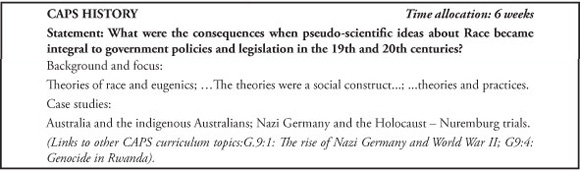

It is difficult to imagine what most teachers will make of this topic: "Ideas of Race in the late 19th Century and 20th Centuries: What were the consequences when pseudo-scientific ideas of Race became integral to government policies and legislation in the 19th and 20th Centuries?" (Which "government policies"? "consequences" for whom?) How will teenagers make sense of such complex questions that are as yet poorly represented in secondary historical literature. Social Darwinism; eugenics; discrimination; racism; ideology; the emergence of science. There is no indication of how the learning of this material might be evaluated. The designers of the curriculum seemed to misjudge the level of competence of their teachers and the level/sophistication of conceptual development of the students.

It is of course not a question of the lack of significance of such issues: it is a question of how "teachable" they are and how examinable they are given the existing state of easily accessible published resources and teacher expertise available in most schools. To the best of my knowledge there is no single easily accessible volume that covers these issues in terms of content quite apart from the possibilities of teaching and examining the topic. It is not at all clear to me how adequately Aboriginal Australian history can be taught outside of a thorough analysis of Australian general history. Or for that matter how the Holocaust can be taught outside of a thorough study of Nazi Germany as it always was in the old JMB Matric Syllabus (this topic was last touched on in Grade 9 with a focus on the World War II).

It would seem that this section is clearly aimed at linking issues of eugenics to Australian aboriginal genocide, to the Holocaust, to apartheid, but this is not stated upfront. It leaves me uneasy to say the least! This is a selective focus on particular aspects of history a foregrounding of specific themes, which precludes a careful contextual analysis. Issues of race conflict need to be explained in the context of the particular histories being engaged with. The whole historiographical revision of the 'seventies in South Africa rested on challenging the view that South African history was all about race and reinterpreting that history in terms of a balance between race and class analysis. This highlighting of race once again seems to preclude those perspectives.

How effectively will the majority of teachers engage with these topics? It seems to me to be unfair to ask a teacher to do this in a credible historical manner.

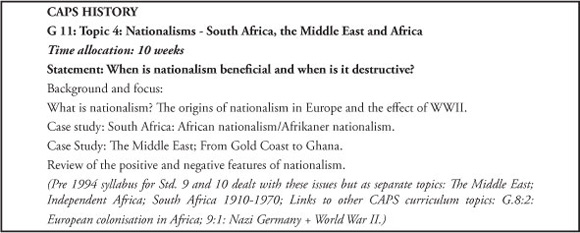

Although there is a statement about the need to "understand where nationalism comes from" there is little space to explore this important issue. Nationalism is here taken up here as a major theme without sufficient reference to its sources in nineteenth century Europe. It is reified and decontextualised. (The last reference to European history was in relation to the French Revolution in Grade 10). The complex background to nationalism as a means of understanding contemporary history has not been put in place. In that context I am concerned about the Statement which once again seems to be located in the realm of political science rather than history.

The focus on nationalism in the South African case would seem to preclude the highlighting of other themes and other ways of approaching and understanding South African history during the period prior to the 1940s (Topic 5). This represents a return to the much critiqued view of the cultural and national interpretations of our history that were decisively disputed in the historical revisions of the 1970s and 1980s and which placed the rise of capitalism, class conflict and social history at the centre of the picture. The historiographical revolution of the 'seventies and 'eighties seems to disappear in this recast of school curriculum. We seem to return to a present - centred curriculum here with an exaggerated focus on race, ethnicity and nationalism.

There is certainly a large literature on these topics and this is accessible to a wide audience, but there is a danger of seeing history in cultural and ethnic terms and downplaying the central role of non-racism and democracy in the constitutional background to our understanding of our history. Once again this retreat from modern historiography, while understandable in the ideological climate of post 1994, is to say the least problematic if understood from the point of view of historical studies and professional historiography. Any teacher who is conversant with modern interpretations of South African history would surely feel uncomfortable with this reversion to nationalism as key lodestone for understanding South African history.

Other studies of nationalism are indicated presumably by way of comparison to the above, namely the post War experience in the Middle East and Africa. There is no explanation for the focus on the Middle East. The controversial nature of the topic and the complexities and difficulties of exploring these issues in a scholarly manner, in a context where on-the-ground knowledge and history expertise is thin, are decidedly problematic. One cannot help but ask why this topic was chosen. Few teachers would be in any position to teach this complex topic effectively with a degree of objectivity. I imagine that there are few resources available on this topic for most teachers.

The inclusion of a topic on Africa and the Gold Coast clearly makes more sense in terms of an African study of a particular context relating to Uhuru politics. And it provides a mirror for understanding the transition processes of the post-War War II world in Africa and the Third World and links to world history to the South African focus.

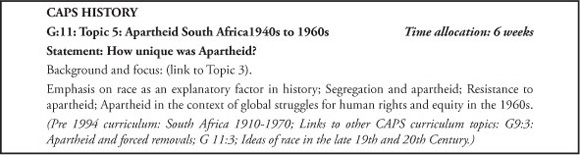

The selection of this topic is in keeping with the commitment to "content and weighting" in a comparative approach (which) reveals the interconnectedness between local and world events. (CAPS:10) It is a core topic that has always dominated the study of school history at the top of the high school. Here, as in Topic 4, the overwhelmingly emphasis seems to have reverted to race as the major explanatory category in South African history when there has been a host of challenges to that exclusive focus in the years since the seventies. As such it presents a rather traditional and nationalistic perspective on the topic with insufficient emphasis on the revisionist challenges to historiography. There is little on the rationale or explanation for apartheid in political, economic and class terms: Why such policies came into existence/what they sought to defend or create. There is very little in the way of a careful analysis of the nature of National Party power and what apartheid was about in terms of political agendas. There is very little on the important explanations of apartheid in economic/class terms.

The overwhelming emphasis is on the opposition and resistance to apartheid. It seems curious that in the long list of list of organisations arrayed against the apartheid government the Liberal Party and the Progressive Party are ignored! One cannot help wondering why this is so!

It seems doubtful whether the framing question for the Statement in terms of the question "How unique was apartheid?" would provide a useful guide to teachers. Is this a historical question? How can the question be answered without a comprehensive knowledge of world history in the 20th Century, which by definition students would not have. The questions which frame and inform the teaching cannot rely on exogenous knowledge if they are to be fair to the students.

In the outline the experience of South Africa under apartheid is not placed in the context of the African revolution or the politics of the Cold War.

This is a clear statement of an important topic for study at this level. But it is not clear how students will be able to engage intelligently with these complex issues without a comprehensive background to the inter-war period, the causes of World War II and the outcomes of the war. (These issues were last studied in Grade 9). All that is mentioned in the curriculum is: "the end of WW II (introduction) and why did the Cold War develop?" This leaves significant gaps for an understanding of the history of the 20th Century and means that there is a lack of context for this study.

The danger of studying history through a rear-view mirror or with hindsight (looking at the Cold War as the focus and then looking backwards) is that the issues that dominated in the Cold War period might clearly be seen to be the major explanatory features of the earlier era. This is clearly not entirely the case! The only place where European history is referred to is in Grade 9:1: The rise of Nazi Germany and World War II; Grade 10: Topic 3: The French Revolution, and in Grade 11: Topic 3, where reference is made to the origins of nationalism in Europe and the Holocaust as an aspect of Race and Racism in the 20th Century. It seems that there is an underestimation of, and lack of appreciation of, the complexity of these issues and the difficulties of teaching them critically and meaningfully without a comprehensive background to European and World History.

What makes logical sense is the extension of the Grade 11 topics: Communism in Russia 1900 to 1940 (Topic 1) and Capitalism in the USA 1900 to 1940 (Topic 2). But this runs into the danger of hindsight of seeing the emergence of the Cold War as a logical and inevitable outcome of these forces in conflict. It erases other aspects of the history of the 20th Century, in particular the challenges to both Communism and capitalist/liberal democracy by Fascism and the Totalitarian powers.

There is no careful periodization of the Cold War or explanation of the dynamics of the post-World War II settlement. In the "Background and focus" there are specific directions for the teaching of "The Origins of the Cold War" which emphasise "overview; source-based questions; broad narrative". It is not clear why the instruction about "overview and "broad narrative" is linked to the use of source materials? Source materials and documents are usually particularly appropriate in relation to detailed study where the student has a good grasp to the context.

This topic is virtually identical to the earlier version in the pre 1994 syllabus (see Appendix A). It needs to be linked to Grade 11: Topic 4: Nationalisms.

What seems to be missing is the context for the rise of African nationalism: the history of nationalism in Europe from the 19th Century to the mid 20th Century and the expansion of those ideas (the post World War I and II settlements in Europe) and the impact on Africa of nationalist struggles in India and elsewhere during and after World War II.

The general framing remark is rather curious, since it is not just the question of "how independence was realized in the 1960s and 1970s" that is a key to the study of the topic, but what the outcome and consequences of that process were during the period indicated and in the context of the Cold War. The general overarching topic does not reflect what follows in the curriculum outline - which does indeed engage with the "successes and challenges faced by independent Africa.

There should surely be attempt to make links here with Third World struggles in Latin America (Che Guevara and Fidel Castro and the Cuban revolution) and its linkages to Topic 3 (Civil society protests 1950s to 1970s) the rise of protest movements of many kinds in the West during these years. Extensive research has demonstrated that these movements were not all about nationalism, i.e. nationalism is one of many explanatory factors which inform an understanding of the history of the Cold War era. Careful guidance is needed if teachers are to grapple with this in an analytical manner rather than simply assume that all historical change is to be attributed to nationalism.

In general the outline is comprehensive and does link coherently to G 12: Topic 1 and to G 11: Topic 4 which deals with Nationalism in Africa (specifically Africa: Gold Coast to Ghana) and elsewhere.

While this is an attractive and "relevant" topic that lends itself to innovative approaches, and to the linkages between global history and South Africa, it is doubtful whether many teachers have a systematic background in the issues concerned.

The curriculum planners seem to have forgotten that much of the protest of this time was Anti- War "Ban the Bomb" in the UK and Germany and anti Vietnam War in the USA. (Link to Topic 1). The great 1968 Paris Student Revolt and many similar responses throughout the world are not mentioned. This is extraordinarily remiss for such a key set of issues. In addition there were other reactions to the post war situation by the Bader Meinhof Gang, Red Brigade and so on and Third World revolution (Che Guevara, Frantz Fanon and Cuba) and issues of development, poverty and Third World liberation. It seems strange that the uprisings in Hungary and Czechoslovakia neglected.

The whole focus here is on the USA and the Civil Right Movement, and the Black Power Movement and the significant rise of the Women's Movement. The topic seems to be framed in terms of race and gender issues, while the history of worker and peasant struggles, trade unionisms and community protest (class) seems to disappear. Some would argue that the whole history of the period is more accurately understood as a set of power issues that were structured around First World economic policies and initiatives linked to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. These issues have direct relevance to an understanding of Topics 4 and 5 on South Africa. But the linkages need to be more carefully specified.

A few brief points. Topic 3 is essentially logically prior to Topic 2. Much of the substance of the Independent Africa section would become much clearer if it were dealt with after this topic, which sets the scene (with Topic 1) for the post - war world. The term "civil society" does not seem appropriate here as this was not a term that was in wide use at that time and reveals a degree of hindsight regarding terminology. In terms of the logical presentation of topics it is essential that the curriculum reflect the logic and chronology of historical convention. The Women's Movement (mentioned five times in various forms) was in fact a late comer to high profile politics of the 'sixties and should be dealt with in correct sequence. Finally, if the framework set out by the curriculum planners demonstrates such an inadequate grasp of the issues to be covered one can only fear for the degree of confidence with which teachers will approach the topic. As mentioned above it is doubtful if most teachers would deal with these issues with confidence.

It is difficult to understand why the theme of civil resistance should be exclusively selected. This theme cannot be understood outside of a full analysis of South African political, economic and social history in this era. It does not make sense to pick out the resistance theme without referring to the dynamics of power in the apartheid society, the nature of apartheid and how it was reformed over time, the nature of the state, foreign policy as an aspect of the Cold War, economic history of South Africa, as well as the history of the opposition to the NP. The issue of a repressive state and the changes it wrought on the nature of resistance politics needs to be highlighted. There is a great deal of emphasis and detail regarding the role of the Black Consciousness Movement during this time, which is appropriate, but this seems to eclipse all other players in the history of the times, such as trade unions (e.g. FOSATU) and even the ANC, PAC and other key players. Somewhat strangely, there is very little reference to the armed struggle and years of exile for many South Africans. War is surely something that needs to be considered as well; as the role of the UDF in the 1980s. Much that is important in the context of resistance seems to be left out!

"The crisis of apartheid in the 1980s" is carefully addressed, but there is insufficient focus on what was being reformed and why. The macro picture is not spelt out with care.

(This section refers back to G11: Topic 5 and to G12 Topic 1: The Cold War.)

It needs to be appreciated that the historical literature of the period is often new to many teachers and that there is a need to ensure that teachers are adequately informed about this "familiar" struggle history and that it is taught with rigour and a degree of objectivity. Questions that need to be asked are: How much do students need to know? What do they need to know for examination purposes? To avoid simple regurgitation of content, careful guidelines would need to be given about the nature of the learning to be encouraged. This is a formidable task and one of the reasons why contemporary history is often avoided at this level where there is little established historical literature or source materials. Thus the limitations of teacher knowledge is probably a significant barrier to effective and critical teaching and learning of this topic.

This content is specified in terms of an understanding of the processes that led to the negotiating process in "the context of the end of the Cold War" and the compromises that had to be made on both sides. Great emphasis is placed on the "the negotiated settlement and the Government of National Unity" and why South Africa chose the TRC process as a means of dealing with history/the past. (There is no critical appraisal of the TRC process.) Then there is a section on "How South Africans come to terms with the Apartheid past." And the whole issue of memorialisation and the meaning of Freedom Park, etc.

This section raises all the old questions about the teaching of contemporary history at school level teaching history that has in a sense not yet been written. What are the key analytical issues that young people are expected to grapple with in a systematic manner? What kinds of questions would be both fair and demanding in an assignment or examination? How do we avoid politics in the classroom? There is a lot of detail about the period of the settlement in the document, but little guidance in the analytical issues at stake and the major lines of historical debate on the topic.

A key issue for consideration in relation to the South African contemporary history for Grade 12: Topic 4,5, and 6 is the difficulty of dealing with the balance between what we would like young people to know about the recent past and our ability or capacity to teach these topics with any degree of depth, distance or objectivity.

The great political changes of the period since the 1980s (struggle and revolution, state reformism, the internal uprising (UDF), the Border War, the nature of the settlement, and the post 1994 "dispensation" ) are of course of great significance for young people, but the state of research and mature historical writing and analysis on these issues still leaves a great deal to be desired. Historians have always stayed away from the immediate past because of the lack of perspective we have on events that are so close to our present political consciousness. With the best will in the world teachers are going to find it difficult to give a balanced account of these issues and one which manages to impart the skills of the historian to students. This problem arises in part out of the raw state of research and published material on these issues, but it is also relates to the ability and capacity of teachers to make these issues into a valid pedagogical project that brings the craft of the historian into the classroom.

This is of course not a problem unique to the teaching of history in South Africa, but it is of particular significance in the context of the need for a balanced and nuanced set of perspectives on the volatile social, political, ideological and economic context in which we live.

This dilemma also highlights the ambiguities or contradictions between the need for civic education in the schools and the goals of history education and points to the dangers of collapsing these goals into one.

Is this not the key problem here? The more one attempts to drive the history curriculum by notions of 'relevance' or present - mindedness, the further away the outcomes become from Counsell's goals of "bringing an epistemic tradition (of history) to the pedagogical site so that pupils can understand the grounds on which valid claims about the past can be made." (Counsell, 2011:202)

Part of the problem would seem to be that discussions on these issues in 2012 are intensely subjective and political and it is very difficult to get a perspective on such issues or even understand clearly the key issues of analysis. If the experts are still debating these issues, and the historians have not yet written in depth about them, it seems unfair to be asking students to write analytical essays and answers to any question that might be asked. What criteria would we be using in assessing the quality of the answers?

Once again we need to consider the question of teacher capacity and ability to teach this topic with rigour and a degree of objectivity. If we are not confident about our answers to these issues it seems irresponsible to proceed with this item. The question of adequate resources is also relevant here.

There is a section on Memorialisation: "Remembering the past: Memorials."

The topic is stated as follows:"how has the struggle against apartheid been remembered? (Appropriate museum or memorial, examples include Freedom Park at national level, Thokoza monument at local level)". What precisely is it that students are supposed to learn here and what would qualify as an appropriate assessment of learning or examination question? Is this not an example of a confusion between methods of motivating students in historical studies, and substantive knowledge of the subject?

It is not clear at all why this item is placed in this order. It is more logical and in keeping with historical convention to place all the world history topics first, followed by the South African material, if for no other reason than to demonstrate in this case that the South African changes are taking place in the context of the end of the Cold War. It is therefore logical in terms of historical explanation to place this section before the South African section given the commitment to an emphasis on the interactions and relationships between international and local histories.

There seems to be little regard for the complexity of this topic and the difficulty of understanding all the complexities of recent events. It is only with the publication in recent years of Tony Judts Post War (2010), and similar works, that we have begun to get a grasp of the architecture of this field of historical research. It is very difficult to see how teachers and students with limited access to resources will be able to engage meaningfully, in the short term, with these complex issues.

There is a kind of postscript to the curriculum statement on page 31 which poses broader questions about the purposes of history education, and which it discreetly notes is "not for examination purposes." The following questions are posed:

- What have we learned from history?

- To what extent can we understand why people behaved in the way they did?

- Has history taught us more about the 'human condition'?

Conclusion

When I was a teacher, students used to often ask: "Why do we have to learn history, Sir?"

I'm not sure I had a convincing answer but I think that students and parents need a serious answer to this question today! If history cannot be taught in an educationally credible manner perhaps it should not be taught at all. Does the CAPS Curriculum for 2012 meet that challenge?

Are we just using the history class as a way of politically inculcating contemporary values? Under apartheid education it was support for apartheid, and now it seems to be support for the democratic constitution. Or is the project espoused by history educators or the defenders of a knowledge- based curriculum that is opposed to the constructivism of Curriculum 2005/OBE of a different order? The emphasis here is on the introduction of students to the practices of the historian and the means of enquiry associated with the discipline of history. Counsell's characterization is precise: "the purpose of teaching and learning history in the classroom is to bring the epistemic tradition of history to the pedagogical site so that pupils can understand the grounds on which valid claims about the past can be made." (Counsell, 2011:202). She warns that this is not an easy task, but that it is a worthwhile educational challenge and an important objective if we are to provide an adequate educational legacy to our students that will prepare them for the challenges and difficulties of life in a democracy. This is not about teaching "objective history" as was sometimes thought in the past; it is about teaching history as a set of intellectual skills and abilities that enable students to think independently within the framework of a set of practices and methods of enquiry. As such these skills are vital to the civic understanding of citizens in a democracy.

In considering the CAPS History curriculum of 2012 we need to ask:

- What are the educational objectives of this document?

- What assumptions were made with regard to the selection of knowledge (content)?

- Why these topics rather than others?

- Why has there been continuity with previous practices in some areas and rupture in others?

- What meaningful educational objectives can be attached to the teaching of the discipline of history for 15-17 year olds?

- What resources are needed to make these objectives attainable?

- Are the teachers capable of making educational sense of the CAPS prescribed curriculum and translating it into viable pedagogical strategies?

In short: Were these topics selected with an eye to political or civic education or were historians consulted about the selection of topics or content (the knowledge selected) and were teachers consulted about the "teachability" of these topic and this content? The essence of the problem is that the historical content selected and the topics chosen need to be able to be defended in terms of the criteria of discipline - based knowledge in the profession of history and in terms of their pedagogic suitability/teachability for teenagers, as well as with reference to the resources available.

Over half of the Grade 12 curriculum is comprised of material that is on the margins of a definition of historical knowledge that is suitable for study at this level if we are serious about providing young people with the skills and forms of understanding that are characteristic of the field of history. Only Topics 1 (Cold War) and 2 (Independent Africa) provide students with the confident possibility of getting into a mature historical literature, or provide the possibility of a teacher being prepared or resources being available. Topic 3 (Civil society protest) is extremely interesting and links many themes relevant to Topics 1 and 2 of the South African section, but I am concerned about the depth of teacher knowledge and the availability and quality of resources.

My real concerns lie with Grade 12: Topics 4, 5, 6 which might well be very important and interesting for students to know and grapple with on grounds of relevance or political education, but the difficulties of relating this material to "the epistemic tradition of (historical studies) so that pupils can understand the grounds on which valid claims about the past can be made" would seem to be made nigh impossible in this context.

There are parts of the CAPS History Curriculum which match the criteria for teaching and learning of the subject laid out in Section 2. But it is in the main only really in relation to the traditional historical topics (often those rescued from the pre 1994 syllabus) which offer hope of achieving those goals laid out in the introduction to this curriculum document. (CAPS: 10-12: History: 8-12)

Where new and "relevant" topics have been crafted with an eye to focussing on the specificity of the post 1994 South African situation, the curriculum planners appear to have entered dubious territory from the point of view of knowledge selection criteria, the ability to assess student work with confidence, and from the perspective of teacher capacity and ability to deliver pedagogically on the demands of the curriculum. The presentism of parts of the curriculum, however apparently dramatic, relevant and significant, is a problem for careful historical analysis and would seem to indicate a degree of confusion about curriculum goals. The desire to fuse a form of civic education with this history curriculum would seem to lead to doubtful outcomes. What is undoubtedly necessary is to promote historical studies which encourage a need for students to view matters of public concern in a historical light (Tosh - personal communication, 2012), but that is by no means the same thing as framing the history curriculum to teach banal "lessons" or promoting an approach that encourages hindsight.