Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of Geography Education in Africa

On-line version ISSN 2788-9114

JoGEA vol.6 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.46622/jogea.v6i1.4653

ARTICLES

Geography learners' awareness and lived experiences of their local environment: A case of Namibia

Tiani Wepener

Department of Human Sciences Teaching, Sol Plaatje University, Kimberley, South Africa tiani.wepener@spu.ac.za https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1743-6452

ABSTRACT

This paper examines the awareness and lived experiences of 28 secondary-level school learners in Namibia, to explore their observations and experiences in their local environments. It investigates the factors influencing their ability and/ or willingness to make observations and to reflect on experiences. The research employed open-ended, semi-structured interviews and drawings to collect data from Grade 11 learners in five research sites across Namibia. The data were analysed using interpretativephenomenological analysis and the themes related to exposure to environments are explored. The study draws on theories of place and informal learning, highlighting the role of everyday experiences in shaping individuals understandings of their surroundings. All the participants showed that they are aware of what makes the environment in which they live different to others, by describing the geographical concepts present in their local environment. However, the findings show that the participants' ability or willingness to make observations can be hindered or reduced by factors such as a lack of interest and familiarity with their local environment and a preoccupied mind. The study highlights the value of understanding learners' perspectives from their own lifeworlds and sheds light on the contribution of the local environment to geographical awareness.

Keywords: everyday Geography; children's geographies; lived experiences; geographical awareness; local environment

Introduction

How people understand and perceive the world and how they engage with their surroundings are lingering geographical questions (Bennett et al., 2017; Xu, Wong & Yang, 2013). Cole (1973: 241) questioned this relationship by asking: "How much 'world-conscious' is a well-travelled person than a younger one, a person with access to pictures of places and to television than one without, a geographer than a non-geographer?" Theories of place in Geography are vital in understanding the relationship of people with each other and the culturally situated, biophysical world (Binz et al., 2020; Greenwood, 2013). Immanuel Kant researched human experience and space extensively. He argued that a person's mind has a built-in spatial schema which plays a similar role to that of a map's relationship to a map projection (Richards, 1974). Kant

believed that all thinking about and knowledge of the world stems from this schema and it is only when the signals transmitted by the world to our senses are mapped, that meaningful patterns are revealed (Richards, 1974). McCarter & Pallasmaa (2012: 10) quote Matoré (1962) who stated that "We do not grasp space only by our senses ... we live in it, we project our personality into it, we are tied to it by emotional bonds; space is not just perceived...it is lived." This paper explores the self-reported awareness and lived experiences of Geography learners from Namibia to determine (1) the observations they make in their local environments; (2) the lived experiences they have had in their local environments, and (3) the factors that influence their ability or willingness to make meaningful observations in their local environments. The participants' observations and lived experiences are important because they shed light on the value and contribution an individual's local environment can make to their awareness of geographical phenomena.

Literature

Lived experiences as informal and incidental learning opportunities

Informal learning is defined as "the lifelong process of reflection-inaction by which every person makes meaning out of their experiences and life situations" (Hasselkus & Ray, 1988: 32) as opposed to formal learning that is "typically institutionally-sponsored, classroom-based, and highly structured" (which informal learning is not) and "control of [informal] learning rests primarily in the hands of the learner" (Marsick & Watkins, 1990: 12). In real-life situations, formal learning and informal learning occur in dialectical unity, and informal learning completes formal learning rather than being opposites on a continuum (Marsick et al., 2017; Scully-Russ & Boyle, 2018).

Illeris (2007) proposed the concept 'everyday learning' as a parallel to everyday consciousness and he argued that learning takes place informally in our everyday lives as we move around in space without really intending to learn something, but inevitably we do gain some understanding. Informal learning in the form of experiential learning, according to Cedefop in Souto-Otero (2021: 367), results "from daily activities related to work, family or leisure. It is not organised or structured in terms of objectives, time or learning support. Informal learning is in most cases unintentional from the learner's perspective." Marsick & Volpe (1999) argue that informal learning is often random and part of an individual's daily routines. The individual is unlikely to be highly conscious of the learning and it is an inductive process of reflection. The characteristics of informal learning are relevant to lived experience. Lived experiences can be classified as informal learning opportunities because they are rooted in an individual's everyday life which is laden with daily routines and interactions with other people and the surrounding environment. Meaning extraction and meaning making are random and are influenced by a variety of internal and external factors (Marsick & Volpe, 1999). An individual can learn from a lived experience without having an intention to do so in the first place.

Incidental learning is part of informal learning and has been simply defined by Watkins & Marsick (2015: 12) as "a byproduct of some other activity". Incidental learning also takes place in everyday experiences and individuals might not always be conscious of it or it might not be recognised as learning (Wagnon et al., 2019). Both informal and incidental learning take place during normal daily events without a high degree of structure (Kimmons & Caskurlu, 2020; Watkins & Marsick, 2015). Both take place along a continuum of conscious awareness which determines the clarity of learning (Watkins & Marsick, 2015). Informal and incidental learning can be enhanced by critical reflectivity, proactivity and creativity (Watkins & Marsick, 2015). Critical reflectivity refers to the ability to critique taken-for-granted and tacit assumptions; proactivity refers to an individual's readiness to take the initiative in learning; and creativity is a person's capacity to consider multiple viewpoints and use new perspectives. Learning therefore takes place when people have the motivation, need and opportunity for learning (Marsick & Watkins, 2001).

Children's geographies

Children, as well as individuals in general, find themselves unavoidably immersed in a tangible, geographic context (Seamon, 1980). This phenomenon captured the interest of geographers during the 1970s, with researchers like Blaut, McCleary & Blaut (1970) and Hart (1979) turning their attention to the environmental experiences and perspectives of children. In doing so, they posed a challenge to the rigid developmental theories put forth by Piaget, while also incorporating elements from other developmental psychologists, such as Vygotsky, who regarded a child's immediate surroundings as a valuable resource for both cognitive and social growth (Ansell, 2009). Vygotsky considered the socialisation of children with others to play a vital role in their cognitive development (referred to as the sociocultural theory of constructivism). This socially mediated process is dependent on assistance children receive from their peers and adults (Devi, 2019). Through social interaction, children can comprehend concepts and construct knowledge they would likely not be able to do on their own (Devi, 2019).

The Human Geography literature has shown children to experience, view and value environments quite differently to grownups (Burke, 2005; Loebach, 2013; Visser, 2020). For example, Matthews & Limb (1999) argue that there is a marked difference between an adult who can recall memorable childhood experiences and children experiencing a place or environment for the first time. Catling (2003) avers that the spatial and environmental knowledge of older children differs from that of adults because their geographies differ. Cultural and social conventions are associated with space which gives a space a certain qualitative dimension which is intrinsically different for children and for adults (Van Manen, 1990). Young people's and adults' interpretations of the same environment are unlikely to be the same because they see, feel and react differently to a landscape (Visser, 2020). Because environments are experienced as places that afford opportunities, a child will remember a place differently than adults will, depending on the opportunities the places afford the child (Matthews & Limb, 1999). There is an evident need to understand children's perspectives from their own lifeworlds rather than assuming that they know less than adults (Arnott & Yelland, 2020). Matthews & Limb (1999) suggest that children might know 'something else!

Hart (1979) has described children's daily lives as multidimensional, unique and inherently spatial, and Caputo (1995) has argued that children's everyday lives are diverse and multifaceted with their own intrinsic value and richness. Children live their everyday lives in physical spaces and they interact with these physical spaces over time. Acar (2014) points out that a human being cannot be seen as a separate entity from his or her environment and that an individual is both the centre of his or her environment and an element in that environment. Rasmussen (2004) reasons that time and place are essential components in conceptualising the transient nature of everyday life. Children explore their surroundings both visually and through the testing out of objects using their senses (Beery & Jorgensen, 2018; Bulman & Moonie, 2004). To a child, according to Day & Midbjer (2007: 3), the world is "one big sensory exploratorium". Even the youngest children are able to exhibit a grasp of the world around them, despite their limited command of graphical and verbal techniques (James, 1990). Children perceive an environment through sight, sound, taste, touch and smell (Ittelson et al., 1974; Moolman, 2015). They live in the here and now, indulging themselves in colour, light, sound, textures, movement and rhythm around them (Haines et al., 2020; Olds, 2001).

Children are constantly collecting and processing experiences that will eventually have an important influence on their later constructed life stories to make sense of their lives (McAdams, 2001; Rogoff, Dahl & Callanan, 2018). Catling (2003: 173) describes children as "natural enquirers who are curious, observant and inquisitive, who relate, classify, analyse, hypothesise and predict continuously about the natural and social environment they inhabit." Thus children develop spatial awareness through familiarisation and exploration in an environment, especially in their own environment (Arnott & Yelland, 2020; Catling, 2003).

Locating the research

This paper forms part of a series of papers that were derived from a doctoral study. The overarching aim of the doctoral research was to analyse the reported geographical lived experiences of selected secondary school learners in four Namibian towns and one city in order to establish the role of their lived experiences in the acquisition of geographical consciousness. The value of children's lived experiences and the lives of children are under researched, taken for granted or regarded as redundant and understanding their unique perspectives and experiences have been identified as being significant (e.g., Holloway 2014, Mason & Danby, 2011. In part, this paper addresses one of the research objectives namely to investigate whether and how the selected Namibian secondary school learners consider and use their everyday environments as a geographical learning resource. The focus of this paper, however, is on participants' local environment only. The following are investigated and reported on: (1) the observations the learner participants make; (2) the lived experiences they have access to, and (3) the factors that influence their ability or willingness to make observations.

Data collection and analysis

Data was collected from four to six Grade 11 Geography learners per school. One school from four towns (Walvis Bay, Otavi, Rundu, Keetmanshoop) and one city (Windhoek) in Namibia were selected as research sites. In total 28 learners participated in the research. The number of females and males participating in the research was almost equal with 15 females and 13 males. The ages of the participants varied from school to school with a range from 16 to 18 years (and one participant aged 21). An open-ended, in-depth and semi-structured interview was conducted with each participant and they were asked to draw a picture based on the statement "Geography is all around me. Draw a picture illustrating your own experience(s) with this statement." Interview questions such as "Would you like to tell me about the observations you have made when driving/walking to and from school?" "Tell me about the different places you interact with on a daily basis?" and "How do you feel about the city/ town/village where you live?". The interviews were conducted in English which is the language of instruction in all the schools where data collection took place. It must however be noted that all the participants are non-native English speakers with English being their second or third language.

Data were examined using interpretative phenomenological analysis. Each participant's interview and the description of his or her drawing were transcribed, coded and categorised into themes. One of the themes, and the theme partially discussed in this paper, that emerged from the data was "exposure to environments". The purpose of investigating the theme was to provide an understanding of the ranges and types of environments participants engage with as well as to establish how these environments are understood and perceived by the participants, their local environment being one of them. The research was done ethically, permission was obtained from the Ministry of Education, participants gave assent and the parents or guardians of participants gave consent (ethical clearance number 2019/ CAES/027). Pseudonyms are used in the place of participants' names, thereby giving the participants added confidentiality and protection.

Results and findings

Participants' observations and lived experiences in their local environments

The participants' awareness of their local environment was explored in relation to the town or city and the neighbourhoods in which they live, the school they attend and the immediate areas in and around these sites. Reference was also made to participants who detailed specifics about their local environment in their drawings. Four categories of specific observations and lived experiences were distinguished, namely natural features, sense of belonging, infrastructure and open public space.

Category 1: Natural features

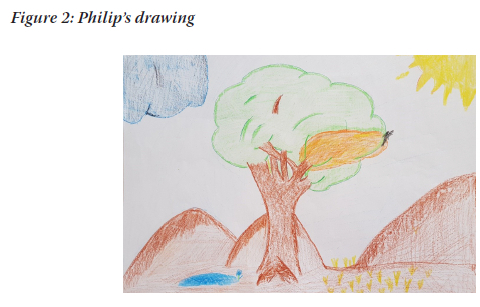

Regarding the first category, some participants' descriptions focused on nature-orientated details like general taxonomic units such as animals (e.g., Yvette) and plants (e.g., Joseph), while others centred on more environment-specific natural geographical features such as topography and geology (e.g., Philip). Trees were highlighted as prominent natural features in the interviews (e.g., John, Ben, James and Melanie).

...the soccer field is stony but not that stony. There are some grasses but no shrubs. (Joseph, Otavi)

Our school is a pleasant place, very beautiful with big trees. (John, Otavi)

After making a turn you just follow a sandy road straight, after going there then you will get a big tree like, at the big tree then when you look at the side you just see an iron or a corrugated iron shack here. (Ben, Rundu)

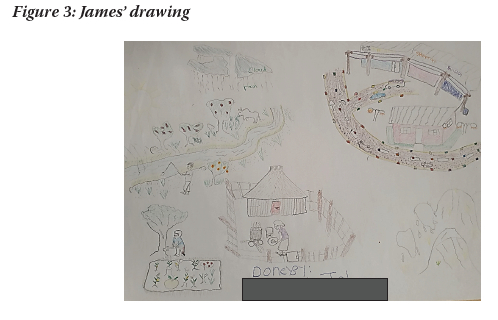

Around our house is surrounded with a wall. In the middle there's only one tree, a big tree where we spend time resting there. Even during summer you'll be there just for nice and cool air there. (James, Rundu)

If you are in my neighbourhood where I live one of the main things that you will see that dominates the surroundings is actually the rocks. (Philip, Keetmanshoop)

.our street has a lot of trees. I think Pionierspark in general has a lot of trees.. (Melanie, Windhoek)

I've noticed recently that there are a lot more animals, like small animals such as meerkat. Ja, like wild animals and birds, a lot more birds in the city, my mom says it's because of the drought, so they're kind of moving, migrating. (Yvette, Windhoek)

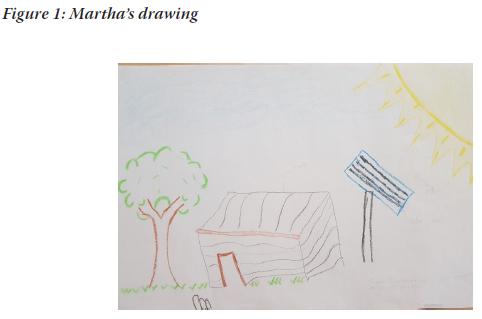

Trees are also included in some drawings. In some drawings a tree is drawn in the centre of the page or bigger in relation to other elements to show its prominence. Like the earlier findings of Moolman (2015), the trees are drawn in such a manner that they show awareness regarding seasonality, colour and aesthetic quality. This finding confirms that these participants recognise that trees contribute to the aesthetic appeal of an area and that trees are considered a valuable resource whether it is to provide shade (Figure 1, Martha, Rundu), firewood (e.g., Miles, Otavi) and a nesting place for birds (Figure 2, Philip, Keetmanshoop). Some participants included fruit trees in their drawings which demonstrates their use as a source of food and firewood (e.g., Figure 3, James, Rundu). It might also be that trees are regarded a site for the imagination.

The emphasis on trees is an interesting finding in the environment of Namibia which is a country dominated by arid or semi-arid conditions. The frequent references to trees suggest the participants' show awareness of (the limited number of) trees. The scarcity of trees in the Namibian environment seems to lead to increased levels of awareness about trees because trees were often used in participants' descriptions as a frame of reference or a landmark in their local environments. One can argue that trees seem to draw the attention of participants because of their prominence and stature in local environments dominated by low-growing vegetation such as shrubs and grass. This also indicates that the learners recognise that trees affect their quality of life and that trees have various benefits.

Scholars agree that trees play an important role in human history metaphorically, symbolically, traditionally and in meaning making (Cloke & Pawson, 2008; Relph, 1976; Pearce, Davison & Kirkpatrick, 2015). The findings from this study concur with those of Merewether (2019) who found that children tend to emphasise the prominence of trees, clouds and rocks. Merewether (2019) maintains that children view themselves as intricately part of and connected to these natural features. The literature also suggests that children find trees fascinating and that trees are often associated with tree climbing, the building of huts and the making of wooden products (Gurholt & Sanderud, 2016; Laaksoharju, Rappe & Kaivola, 2012; Laaksoharju & Rappe, 2017; Shackleton et al., 2015).

The inclusion of natural features particularly into the participants' drawings can be due to the influence of media (print and online). It is common for Namibia to be portrayed on the media as a desert environment with a few scattered trees (for example, the fossilised trees at Deadvlei or a Quiver tree in the South of Namibia).

Category 2: Sense of belonging

The second category refers to how participants feel about living in their town or city. According to political geographer John Agnew, place has three fundamental aspects, namely place as an absolute location with a latitudinal and longitudinal positioning, place as a locale where everyday life activity takes place and sense of place which refers to people's affective attachment to a place (Agnew, 2011). Below are examples of participants' voicing their experiences of a sense of belonging to their local environment.

Otavi is a very small town. You'll find different people. Otavi is not like Windhoek where there are a lot of loose criminals. So, if you come here, you'll be free. You don't need to be scared. (Joseph, Otavi)

Rundu really has a lot of memories for me, because I grew up here. I don't know other places but, Rundu is like home. I feel home, I feel safe. (Riana, Rundu)

The fact that everyone is treated the same in this place. It does not matter whether you are Ovambo, Nama or what you are. But everyone sees you the same. (Ann, Keetmanshoop)

Keetmanshoop is small so it's a tight-knit community. So most of the time, we know people, so you get to know people better. You have a close relationship with people, so it's better socially living in Keetmanshoop. (Philip, Keetmanshoop) Rehoboth is different because it's, I think it's a Baster community. So like, all of us coloureds are there. And then the difference is that, I can't really think of something now, but it's probably just like, we work together as a community. (Matthew, Windhoek)

For the people, for our neighbours, our neighbours are lovely. Everybody is just in their own thing, but then they all have this thing that connects everyone to one another, so I would say. (Adam, Windhoek)

...the neighbours we are very connected and so on, we know each other and we always interact and yes there are a few of us that have been staying there longer than the others, but there is still a bond. (Kristen, Windhoek)

It is very friendly because everybody knows one another. A lot of people, here where I live, mainly the street, everybody knows one another. They grew up with one another and their children grew up knowing one another, like, ja, it is very friendly. We borrow sugar from one another. It is not like those towns or like in Meersig where nobody wants nothing from nobody. It is just like, 'Anita, can you please go and ask Aunt Nita for something or something like that or Aunt Nita will come and ask us for something. (Anita, Walvis Bay)

Emphasis was also placed on how safe participants (e.g., Riana and Joseph) feel in their local environment. It is evident that some participants (e.g., Kristen and Matthew) experience an affective sense of place and belonging in their town, city and communities. Participants' (e.g., Anita, Adam and Philip) use of words and phrases such as 'family, 'friendly, 'chain of community, 'tight-knit' and 'this thing that connects everyone to one another' are some of the expressions describing how they feel.

Community cohesion is significant because it not only influences how participants feel about a place but also how they choose to engage with those places. Participants' sense of place and belonging is of consequence in this study because it can determine their willingness and desire to contribute to the protection of their local environment. Various scholars (e.g. Daryanto & Song, 2021; Ramkissoon, et al., 2012 2012; Scannell & Gifford, 2010) agree that attachment to place is vital because it fosters a sense of belonging which can influence people's pro-environmental behavioural

intentions. An individual with a stronger place attachment is expected to possess more positive attitudes than an individual with a weaker place attachment. Positive attitudes can contribute to the development of geographical consciousness (refer to Wepener & Pretorius, 2023) which can in turn contribute to sustainable development. One's connection (or disconnection) to a place will influence one's willingness to protect it (Scannell & Gifford, 2010).

Category 3: Infrastructure

The third category that emerged is participants' descriptions of their local environments in terms of infrastructure, especially buildings and roads. The type, size, age, condition and architecture of the buildings (e.g., Jonathan and Matthew) seem to catch their attention, while the types and business of roads and the occurrences of motor-vehicle accidents (e.g., Joseph and Christel) are other aspects that they noticed.

Mostly we have these gravel roads. There are no tarred roads. People usually complain, like whenever we come to school, we're dirty so, we must at least walk on something that does not make our shoes dusty. (Joseph, Otavi)

There are so many gravel roads. Basically the town was just poorly planned. If it was planned very well then we could have good infrastructures. Rundu is big, it's not really populated but the thing is it's like, it does not have so many facilities like golf course, parks and we don't really have a lot of shops, malls. (Martha, Rundu)

It's a nice town. We have a lot of things here, like Kavango river and lodges, showcasing our culture. (Amanda, Rundu)

I like the buildings a lot because it is attractive and it is old buildings and it makes this place [Keetmanshoop] unique - because it is beautiful... (Ann, Keetmanshoop)

I see buildings, cars, roads, flowers and the bridge. Sand, the sky and the sun. (Wilmien, Keetmanshoop)

Other places such as Windhoek has a cinema. We do not have a cinema yet. A game shop with a variety of games, we do not have things like that. (Lizl, Keetmanshoop)

To me the infrastructure, they've really improved the roads, and are well-managed. There are now also traffic lights in the location, which is much better. Because back in the years there weren't traffic lights, so it was a risk crossing the road. (Daniel, Keetmanshoop)

Well we have a big school. I think it's about 3 buildings total. Our school is now 100 years old, we have about 3 blocks in total I would say. We have our big main hall and then our small hall, we have a tuckshop and what not. We have a rugby field that is also in a big dug out area and we have a few netball fields as well, we have a hockey field, it's a pretty large school so the surface area I would say is pretty large. (Jonathan, Windhoek)

The school is beautiful compared to other schools.

It is mostly developed, it's in a good state, buildings are painted, and then, it has good characteristics. You feel at home; you feel welcome at school. (Matthew, Windhoek)

It [Windhoek] has a certain something to it, because everything has been developed, but then it has been here for a very long time. I once went on an exhibition around these areas, and found out what each building means. And it has a lot of history. So whenever we drive up here, I would always just observe everything, how everything is changing year by year. But then it always keeps that one thing that just makes it important, so I would say is the infrastructure. (Adam, Windhoek)

There was once an accident when I was on my way to school..it is busy in the mornings because everyone is trying to get to work. (Christel, Walvis Bay)

People are building more homes. I have noticed that people really love vandalising walls and doing their graffiti. It is quite interesting because it is building established for a reason and you are vandalising it. You know, it says you are breaking down things that were built for a reason. (Sharon, Walvis Bay)

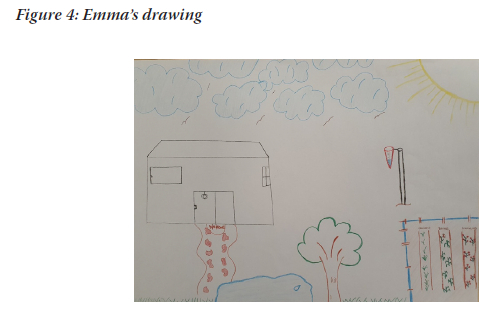

This was also apparent in some drawings. The participants drew their homes (e.g., Kristen, Windhoek), their school (e.g., Figure 4, Emma, Otavi), other developments (e.g., Matthew, Windhoek) or roads (e.g., Christel, Walvis Bay).

Owing to their engagement in and with their local environments, some participants (e.g., Adam) described these infrastructural developments in terms of change over time. The participants also seemed to be aware of roads and their associated functions because of their preference to walk from point A to point B in their local environments. It is also evident that participants are able to provide more detailed descriptions of spaces such as school and home. These are the spaces and places where participants spend most of their time, thereby explaining their frequent references to and familiarity with them. Korpela (1992) and Lieberg (1995) also found that "home" is considered by some individuals as highly favourable places because home is viewed as a place where a person feels stable, valued and safe (Koops &Galič, 2017).

With reference to the quotes provided for the third category, some participants (e.g., Matthew and Daniel) place emphasis on infrastructural improvements and scenic value of infrastructure in their local environment, others (e.g., Martha and Joseph) concentrate on negative characteristics such as poor town planning, urban degeneration and the lack of development. Participants who seem to consider the infrastructure in their local environment to be adequate, well maintained or in the process of being developed demonstrate levels of pride and ownership by using words such as 'big', 'beautiful', 'nice', 'unique', 'developed' and 'home' (e.g., Amanda and Matthew) as opposed to those who voice their dissatisfaction and disappointment by using words such as 'poorly planned', 'vandalising', 'old and outdated' and 'congested' (e.g., Martha and Sharon). Rollero & De Piccoli (2010) found that participants with a high attachment to place were more likely to use words such as 'home', 'history', 'beautiful' and 'welcoming' while participants with a low attachment to place focused on problems such as traffic congestion, pollution and immigrants. This latter observation suggests a relationship betwe en p articip ants' place attachment to their local environment and their tendency to describe it negatively or positively.

Category 4: Open public spaces

The fourth category about participants' local environments which surfaced as significant during the interviews was open public spaces. Some examples of participants' experiences with open public spaces are provided below. These open public spaces include spaces in the learners' neighbourhoods, in town or around the school. This corresponds with Koops &Galič,'s (2017) explanation of public space which includes the spaces individuals interact with as they move between places, such as commuting to work or school. Public spaces in the context of this study also refer to any open spaces that are available and open to all people, including green spaces. Some participants (e.g., Emma and Ann) refer to these spaces in a distant manner by using the term 'there'. Elden (2009) contends that place is often understood as localised and 'in here' in contrast to space that is less personal and 'out there. This becomes evidently clear in the manner in which the participants describe their surroundings.

And then there's actually an area, an open area where the boys usually play soccer there. (Emma, Otavi)

So there you mostly find toddlers, and children running around in the streets, which is not good at all. And sometimes you see that the father is at the bar, and then now he has keys. It's really not a good thing. (Emma, Otavi)

...the way its planned like the ground I really appreciate because its divided into things but the thing that I also want like, they need to change a bit like, they need to place something there at the vacant place, it is vacant so they need to place something like for entertainment maybe the kids are not going home for lunch then they can just do the things. (Ben, Rundu)

And the Town Council they don't collect the dustbins on a daily basis. Maybe after 2 or 3 weeks and then people end up gathering their rubbish somewhere else and then it becomes a habit, every time they just throw the things there. (Martha, Rundu)

Back when I was in primary school, the areas were big, open areas without buildings, or houses. But now those areas are mostly filled with new houses that have been built, or how can I say? People that can't afford to buy new houses, they mainly build their own shelter there for sleeping, but then they are being forced by the municipality to move out. (Daniel, Keetmanshoop)

The town is a quiet place. It is welcoming but the refuse bothers me. This place is too dirty. There are too many open spaces. I feel more buildings should be built there. The veld is too much and it makes this place look like a farm. (Ann, Keetmanshoop)

And I want to talk to my friends while going home, some extra time. So I usually prefer walking home. (Sharon, Walvis Bay)

Participants' interactions with open public spaces involved physical and social affordances as well as positive and negative affordances. The term 'affordance' refers to the functional, social and emotional opportunities an environment offers for an individual (Kytta, 2008; Kytta et al., 2018). In this study, physical affordances include the playing of team sports such as soccer and walking (e.g., Emma), while social affordances include participants' socialisation with friends (e.g., Sharon). Positive affordances are associated with elements that participants like in their local environment as opposed to negative affordances that focus on what is disliked or avoided. For certain participants, open spaces have negative physical and social affordances. Vacant spaces are often associated with a lack of development and entertainment (e.g., Ann), physical problems such as littering (e.g., Martha) and the erecting of shacks (e.g., Daniel) and social problems such as the abuse of alcohol in public and the negligence of parents (e.g., Emma). There is an indication that participants expect the open public spaces to be clean rather than dirtied with litter (e.g., Ann) and to be a suitable space to engage in (e.g., Ben). This can also be an indication that some participants expect these public areas to be filled with infrastructure and developments that can improve the participants' quality of life.

Factors that influence participants ability or willingness to make observations in their local environments

This research has also zoomed in on the characteristics of the perceivers and some of the barriers that influence participants' ability to make observations and to reflect on lived experiences were identified. Some of the factors that affect participants' awareness of their local environment and their ability and willingness to make observations are quoted below.

I don't take note, I just, I just used to see it for several times then if like going out of interest. (Ben, Rundu)

I do not really look around me. I am not bothered with other people; I am on my own. (Wilmien, Keetmanshoop)

I don't know, but I feel like especially now that I'm in Grade 111 have so much stuff on my mind it's hard to focus on what's happening now, like where I am and what I'm doing. I often feel like I'm on autopilot, if that makes sense, like you're just automatically doing everything, not really thinking about what you're doing but thinking about what you have to do next. (Yvette, Windhoek)

I mostly look out of the window but then my thoughts are not there. It's on another place, so I don't really notice the things, only here and there. I mostly think about school and the stress, the pressure and everything, it is just making me depressed but I'm fine. Since I would really like to get good marks to apply for scholarships and so I can go and study in other places. And then my mother's always expecting like good marks and then some of the teaches also since they already know you can achieve it, but sometimes they work us just too much and then we have to study for a lot of tests. (Kristen, Windhoek)

I am a lazy person overall. I don't concentrate much on one thing; my attention gets grabbed to something else very quickly ifI don't focus on something that I enjoy. Mornings I would still sleep in the car because I am tired. Afternoons I would think to myself, oh no I have homework, I have to study for exams, so crying a bit inside. (Jonathan, Windhoek)

And I see, I see around me but it is difficult because you are usually on your phone and your mind is occupied with other things. (Melanie, Windhoek)

So I've noticed there are a lot of people commuting from Windhoek to Rehoboth. And then, so like when I'm on the road, I sleep most of the time, but I've just noticed that it's busy, the road is busy all the time. (Matthew, Windhoek)

It is really not interesting. We just see other people going to work or getting to school - just doing their daily lives. We see that every day. (Jeremy, Walvis Bay)

Most of the time I chat with my friends so I do not look around. We wait for a car to pass and then we continue to talk. (Christel, Walvis Bay)

Some participants (e.g., Yvette and Kristen) found their thoughts to be preoccupied with schoolwork and academic pressures. Others (e.g., Jeremy and Ben) indicated that the monotonous nature of their local environments and the features in their local environments make them lose interest. Social affordances also play a role. Christel, for example, asserted that because she engages in conversations with her friends, she tends to not make observations in her local environment. Wilmien and Melanie, on the other hand, find themselves being preoccupied with their own thoughts and lives rather than what is happening around them or what others are doing. Matthew and Jonathan admitted that they do little observation because they sleep on their way to school.

Discussion

From the exploration of participants' experience of their local environment, it is noteworthy to point out that all the participants demonstrate some degree of awareness of their surroundings and are able to identify the characteristics of the spaces they interact with on a regular or daily basis in their local environment. The spaces participants are exposed to vary from participant to participant so that the level of detail in their descriptions also varies greatly. In describing their local environments and everyday spaces some participants focus primarily on physical attributes or social dimensions, whereas others concentrate on how these spaces make them feel. Overall, it appears that the participants are acquainted with their local environments. According to Xu et al., (2013) one expects a person to have a greater awareness of his or her local Geography than that of places further away.

This being said, there are discrepancies. While some participants (e.g., James, Rundu and Jeremy, Walvis Bay) make plentiful observations and provide detailed descriptions of their surroundings during the interviews, this was not the case for all participants. Some participants (e.g., Yvette, Windhoek and Martha, Rundu) had difficulty sharing observations that they have made in their local environments. During the interviews, prompts such as "please elaborate", "please explain why you say that" and/or "can you provide examples of" were needed to reveal some observations. The level of detail of participants' descriptions is subject to a range of influencing factors such as place attachment and the eagerness to reflect upon past experiences and/ or observations. Rollero & De Piccoli (2010) found that different individuals attribute different meanings and features to the same environment, depending on their place attachment. Rollero & De Piccoli (2010) argue that place perception is not only dependent on the information available within an environment but also on the characteristics of the perceiver. This appears to be true for this study as well, suggesting that the lived experiences and awareness of learners are highly individualised.

From the evidence presented, two main conclusions can be drawn about the participants' awareness and conceptual consciousness of their local environments. The first is that most participants are well aware of their local environments. Various participants pointed out that their local environment is a milieu that they encounter and see on a daily basis. It is common for participants to see and experience the same people, places and phenomena on a daily or regular basis as they walk or drive to school, home and town and back. It is also a routine to walk along the same footpath or to drive along the same roads between points of interest. By being exposed to the same environment repeatedly results in familiarity. Familiarity largely depends on the duration a participant has been living in his/her local environment. Some participants, such as James from Rundu and Miles from Otavi who have not been living in their local environment for an extended period, because they moved there recently, are able to provide more detailed descriptions of their (current) local environment. The 'newness' and unfamiliarity of a new local environment provokes interest, enthusiasm and curiosity in participants. They also display an eagerness to make and share observations. These participants tend to compare their previous local environment with the local environment they presently find themselves in.

Familiarity results in participants having difficulty to reflect and report on what they see or have noticed in the past. While participants indicated that they have made many observations and that they are aware of their surroundings, reporting on these observations is challenging (e.g., Yvette and Melanie, Windhoek). By repeatedly observing and experiencing the same phenomena in their local environment dampens their interest and eagerness to make further observations (e.g., Ben, Rundu and Jeremy, Walvis Bay). The familiarity of the local environment means that some participants have become accustomed to what the local environment has to offer and what makes it different. This finding is significant because it shows that the frequent engagement by the participants with environments, such as their local environment, results in implicit knowledge. Frequent exposure means that the characteristics of the local environment are ingrained in the perceptions and experience of individuals ofthat specific environment. Frequent exposure to and familiarity with their local environment, leads to passive engagement with their local environment. The consequences of this inattentiveness are beyond the scope of this research, but one can argue that it might influence the cognitive and affective domains of individuals in varying ways.

The second conclusion is that participants (being Grade 11 learners who are preparing for their Grade 12 examination) experience immense academic pressure and fatigue. Some participants find themselves being consumed with stress and worry based on the expectations placed on them. Academic pressure is exerted by parents, teachers and the participants themselves. This is especially so with the city (Windhoek) participants who are evidently experiencing more pressure and greater levels of expectation to attend university after high school compared to the participants from the four towns (e.g., Kristen and Jonathan, Windhoek). This suggests that formal education (including homework and assessments) may hinder participants from making observations which then limits their awareness of their local environment. One can conclude that these academic pressures may inhibit participants' ability to use their local environment as learning resources. The potential meanings they extract from engagement with their local environment may be constricted because they are not in a mental space conducive to exploration and inquiry. This suggests that an individual's ability to actively sense their environment as "one big sensory exploratorium" as referred to by Day & Midbjer (2007) might be negatively influenced by variables such as stress, academic pressures and the use of cell phones, especially in older learners

Conclusions

The findings of this study indicate that secondary-level school learners in Namibia experience their local environments in both tangible and intangible ways. They can provide accounts of their lived experiences and observations. While some learners consider the physical properties of their local environment noteworthy and significant, others regard the affective properties and how their local environment makes them feel as most important. Based on the analysis of both the interviews and drawings, four main categories were identified: natural features, a sense of belonging, infrastructure, and open public space. It is evident that trees hold a special place in the hearts and minds of the learners, not only as physical entities but also as powerful symbols and connectors to their environment. Their descriptions of infrastructure and open public space are coloured by both positive and negative aspects, reflecting their expectations for their surroundings.

The frequent exposure of participants to their local environment also poses some challenges because it fosters familiarity and leads to a lack of curiosity. This study also highlights the burden of academic pressure and expectations placed on Grade 11 learners. This is significant because it may hinder the learners' capacity to fully explore and engage with their local environment as valuable learning resources.

Author Bios

Tiani Wepener recently completed her PhD at the University of South Africa. She is a lecturer at Sol Plaatje University in Kimberley. She teaches Geography and Social Sciences pedagogies and didactics to education students. Her research interests include children's geographies and geographical consciousness.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

Acar, H. (2014). Learning environments for children in outdoor spaces. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 141, 846-853. [ Links ]

Ansell, N. (2009). Childhood and the politics of scale: Descaling children's geographies? Progress in Human Geography 33(3), 190-209. [ Links ]

Arnott, L., & Yelland, N.J. (2020). Multimodal lifeworlds: Pedagogies for play inquiries and explorations. Journal of Early Childhood Education Research 9(1), 124-146. [ Links ]

Beery, T., & Jorgensen, K.A. (2018). Children in nature: sensory engagement and the experience of biodiversity. Environmental Education Research 24(1), 13-25. [ Links ]

Bennett, N.J., Roth, R., Klain, S.C., Chan, K., Christie, P., Clark, D.A., Cullman, G., Curran, D., Durbin, T.J., Epstein, G., & Greenberg, A. (2017). Conservation social science: Understanding and integrating human dimensions to improve conservation. Biological Conservation 205, 93-108. [ Links ]

Binz, C., Coenen, L., Murphy, J.T., & Truffer, B. (2020). Geographies of transition - From topical concerns to theoretical engagement: A comment on the transitions research agenda. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 34, 1-3. [ Links ]

Blaut, J. M., McCleary, G. F., & Blaut, A. S. (1970). Environmental mapping in young children. Environment and Behavior 2(3), 335-349. [ Links ]

Bulman, K., & Moonie, N. (2004). BTEC first early years student. Oxford: Heinemann. [ Links ]

Burke, C. (2005). "Play in focus": Children researching their own spaces and places for play. Children Youth and Environments 15(1), 27-53. [ Links ]

Caputo, V. (1995). Anthropology's silent 'others'. In Amit-Talai, V., & Wulff, H. (eds) Youth cultures: A cross cultural perspective, 19-42. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Catling, S. (2003). Curriculum contested: Primary geography and social justice. Geography 88, 164-210. [ Links ]

Cloke, P., & Pawson, E. (2008). Memorial trees and treescape memories. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 26(1), 107-122. [ Links ]

Cole, J. (1973). Perception in Geography. In Bale, J., Graves, N., & Walford, R. (eds) Perspectives in Geographical Education, 239-248. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd. [ Links ]

Daryanto, A., & Song, Z. (2021). A meta-analysis of the relationship between place attachment and pro-environmental behaviour. Journal of Business Research 123, 208-219. [ Links ]

Day, C., & Midbjer, A. (2007). Environment and children: Passive lessons from the everyday environment. Amsterdam: Architectural Press. [ Links ]

Devi, K.S. (2019). Constructivist approach to learning based on the concepts of Jean Piaget and lev Vygotsky. Journal of Indian Education 44(4), 5-19. [ Links ]

Elden, S. (2009). "Space I". In Kitchin, R., & Thrift, N.J. (eds) International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, Volume 10, 262-267. Oxford: Elsevier. [ Links ]

Greenwood, D.A. (2013). A critical theory of place-conscious education. In Robert, B., Stevenson, M.B., Dillon, J., & Wals, A.E.J. (eds) International Handbook of Research on Environmental Education, 93100. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Gurholt, K.P., & Sanderud, J.R. (2016). Curious play: Children's exploration of nature. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning 16(4), 318-329. [ Links ]

Haines, K., Case, S., Smith, R., Joe Laidler, K., Hughes, N., Webster, C., Goddard, T., Deakin, J., Johns, D., Richards, K., & Gray, P. (2020). Children and crime: In the moment. Youth Justice 21(3), 275-298. [ Links ]

Hart, R. (1979). Children's experience of place. New York: Irvington. [ Links ]

Hasselkus, B.R., & Ray, R.O. (1988). Informal learning in the family: A worm's eye view. Adult Education Quarterly 39(1), 31-40. [ Links ]

Holloway, S.L. (2014). Changing children's geographies. Children's Geographies 12(4), 377-392. [ Links ]

Ittelson, W.H., Proshansky, H.M., Rivlin, L.G., & Winkel, G.H. (1974). An introduction to Environmental Psychology. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. [ Links ]

James, S. (1990). Is there a 'Place' for Children in Geography? Area 22, 278-283. [ Links ]

Kimmons, R., & Caskurlu, S. (2020). The Students' Guide to Learning Design and Research (online). Available from: https://edtechbooks.org/studentguide [Accessed 29 September 2023].

Koops, B.J., &Galič, M. (2017). Conceptualizing space and place: Lessons from geography for the debate on privacy in public. In Timan, T., Newell B.C., & Koops, B.J. (eds) Privacy in Public Space: Conceptual and Regulatory Challenges , 19-46. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar [ Links ]

Korpela, K.M, (1992). Adolescents' favourite places and environmental self-regulation. Journal of Environmental Psychology 12(3), 249-258. [ Links ]

Kytta, M. (2008). Children in outdoor contexts: Affordances and independent mobility in the assessment of environmental child friendliness. Saarbrücken: VDM Verlag. [ Links ]

Kytta, M., Oliver, M., Ikeda, E., Ahmadi, E., Omiya, I., & Laatikainen, T. (2018). Children as urbanites: Mapping the affordances and behavior settings of urban environments for Finnish and Japanese children. Children's Geographies 16(3), 319-332. [ Links ]

Laaksoharju, T., & Rappe, E. (2017). Trees as affordances for connectedness to place - a framework to facilitate children's relationship with nature. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 28, 150-159. [ Links ]

Lieberg, M. (1995). Teenagers and public space. Communication Research 22(6), 720-744. [ Links ]

Loebach, J.E. (2013). Children's neighbourhood geographies: Examining children's perception and use of their neighbourhood environments for healthy activity. Doctoral dissertation. Ontario: University of Western Ontario, Graduate Program in Geography. [ Links ]

Marsick, V.J., & Watkins, K. (1990). Informal and incidental learning in the workplace. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Marsick, V.J., & Watkins, K.E. (2001). Informal and incidental learning. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education 89, 25-34. [ Links ]

Marsick, V.J., Watkins, K.E., Scully-Russ, E., & Nicolaides, A. (2017). Rethinking informal and incidental learning in terms of complexity and the social context. Journal of Adult Learning, Knowledge and Innovation 1(1), 27-34. [ Links ]

Marsick, V.J., & Volpe, M. (1999). The nature of and need for informal learning. In Marsick, V.J., & Volpe, M. (eds) Advances in developing human resources, Volume 1, 1-9. San Francisco: Berrett Koehler. [ Links ]

Mason, J., & Danby, S. (2011). Children as experts in their lives: Child inclusive research. Child Indicators Research 4, 185-189. [ Links ]

Matthews, M.H., & Limb, M. (1999). Defining an agenda for the geography of children: Review and prospect. Progress in Human Geography 23(1), 61-90. [ Links ]

McAdams, D.P. (2001). The psychology of life stories. Review of General Psychology 5(2), 100-122. [ Links ]

McCarter, R., & Pallasmaa, J. (2012). Understanding architecture: A primer on architecture as experience. London: Phaidon Press. [ Links ]

Merewether, J. (2019). Listening with young children: Enchanted animism of trees, rocks, clouds (and other things). Pedagogy, Culture & Society 27(2), 233-250. [ Links ]

Moolman, T. (2015). The environmental reasoning of secondary-level schoolchildren: A case study of Okahandja, Namibia. Master's thesis. Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University, Department of Geography and Environmental Studies. [ Links ]

Olds, A.R. (2001). Childcare design guide. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Pearce, L.M., Davison, A., & Kirkpatrick, J.B. (2015). Personal encounters with trees: The lived significance of the private urban forest. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 14(1), 1-7. [ Links ]

Ramkissoon, H., Weiler, B., & Smith, L.D.G. (2012). Place attachment and pro-environmental behaviour in national parks: The development of a conceptual framework. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 20(2), 257-276. [ Links ]

Rasmussen, K. (2004). Places for children-children's places. Childhood 11(2), 155-173. [ Links ]

Relph, EC (1976). Place and Placelessness. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [ Links ]

Richards, P., (1974). Kant's geography and mental maps. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 61, 1-16. [ Links ]

Rogoff, B., Dahl, A., & Callanan, M. (2018). The importance of understanding children's lived experience. Developmental Review 50, 5-15. [ Links ]

Rollero, C., & De Piccoli, N. (2010). Place attachment, identification and environment perception: An empirical study. Journal of Environmental Psychology 30 (2), n198-205. [ Links ]

Scannell, L., & Gifford, R. (2010). The relations between natural and civic place attachment and pro-environmental behavior. Journal of Environmental Psychology 30(3), 289-297. [ Links ]

Scully-Russ, E., & Boyle, K. (2018). Sowing the seeds of change: Equitable food initiative through the lens of Vygotsky's cultural-historical development theory. New Directions for Adult & Continuing Education 159, 37-52. [ Links ]

Seamon, D. (1980). Body-subject, time-space routines, and place-ballets. In Buttimer, A., & Seamon, D. (eds) The human experience of space and place, 148-167. London: Croom Helm. [ Links ]

Shackleton, S., Chinyimba, A., Hebinck, P., Shackleton, C., & Kaoma, H. (2015). Multiple benefits and values of trees in urban landscapes in two towns in northern South Africa. Landscape and Urban Planning136, 76-86. [ Links ]

Souto-Otero, M. (2021). Validation of non-formal and informal learning in formal education: Covert and overt. European Journal of Education 56(3), 365-379. [ Links ]

Visser, K. (2020). 'I didn't listen. I continued hanging out with them; they are my friends.' The negotiation of independent socio-spatial behaviour between young people and parents living in a low-income neighbourhood. Children's Geographies 18(6), 684-698. [ Links ]

Wagnon, C.C., Wehrmann, K., Klöppel, S., & Peter, J. (2019). Incidental learning: a systematic review of its effect on episodic memory performance in older age. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 11(173), 1-15. doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2019.00173 [ Links ]

Watkins, K., & Marsick, V.J. (2015). Informal and incidental learning in the workplace. Abingdon: Routledge. [ Links ]

Wepener, T., & Pretorius, R.W. (2023). A model of lived experiences and geographical consciousness based on Namibian secondary school learners' perspectives. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education. doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2023.2201757

Xu, C., Wong, D.W., & Yang, C. (2013). Evaluating the "geographical awareness" of individuals: An exploratory analysis of twitter data. Cartography and Geographic Information Science 40(2), 103-115. [ Links ]