Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

African Journal of Gender and Religion

On-line version ISSN 2707-2991

AJGR vol.29 n.2 Johannesburg 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.36615/ajgr.v29i2.2800

ARTICLES

Crochet Methodology: Thinking Creatively about and with the Study of Religion in the Anthropocene

Nina Hoel

University of Oslo nina.hoel@teologi.uio.no. ORCID https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0461-3528

ABSTRACT

What stories of religion matter in the age of the Anthropocene? This paper begins by situating the Abundance Crochet Coral Reef, an installation of crocheted coralline landscapes exhibited at the Two Oceans Aquarium in Cape Town, as a methodological motif and enactment to think creatively about and with the study of religion in the Anthropocene. Journeying through the current trends in various fields in the study of religion that are responsive to Anthropocene concerns, I argue that there is a growing body of scholarly work that troubles the dualisms and hierarchies of human-nature and nature-culture that have informed, and indeed, dominated, conceptualizations about religion and the study of religion. Finally, I turn to feminist theory to continue to in-tune religion storytelling (the study of religion) to the challenges of the Anthropocene. Drawing inspiration from the Abundance Crochet Coral Reef, I explore the concept of kinship to open creative vistas for methodological enrichment in the study of religion.

Keywords: Anthropocene, the study of religion, crochet methodology, feminist theory, kinship

Introducing Crochet Methodology as Relevant for the Study of Religion1

A few weeks ago, I visited the Two Oceans Aquarium in Cape Town. As expected, my two children wanted to reunite with Sally the Seal and Bruce the Shark, two fluffy characters in the Two Oceans Aquarium series of educational puppet shows. Then, we were off to the popular Touch Pool, an interactive exhibit where visitors can get their hands wet (literally) to experience and feel the textures of anemones, kelp, and starfish. But, "hey, mommy, come! What's on that wall?" my six year old exclaims, forgetting all about the kelp in his hand. There, between the Touch Pool and the Penguin Exhibit, I see a mesmerizing display of colors. "Are those corals? Are they real?" We move closer.

The installation, entitled The Abundance Crochet Coral Reef, was developed by the Woodstock Art Reef Project (WARP). Having curated the Cape Town Satellite Reef in 2010, as part of the worldwide eco-art project, the Crochet Coral Reef, The Abundance Crochet Coral Reef found a new home at the Two Oceans Aquarium in Cape Town.2 The installation is an entangled collection of crocheted coralline landscapes, hand-made by hundreds of local South Africans, primarily women. As an eco-art project, The Abundance Crochet Coral Reef draws attention to the severe damage to coral reefs around the world. Looking at the installation, the entire left side of the crochet coral reef is made by crocheting nuances and intricate gradations of white. The white coralline landscape demonstrates the phenomenon of coral bleaching, the process by which corals lose their effervescent colors and become white. The visuality of coral bleaching that the installation cultivates brings to mind, what radical evolutionary theoretician and cellular biologist, Lynn Margulis, termed, "the intimacy of strangers", namely, the fundamental evolutionary practice of becoming-with each other.3 For the corals experiencing environmental stress, such as an increase in oceanic temperature and pollution, it is the loss of or, rather, the dissolution of the symbiotic condition (the cessation of multi-species entanglements) that causes the bleaching. Corals fade and turn white as they expel the microscopic algae that live within their tissue and give them color. Without the other, we do not survive.

The right side of the installation displays a healthy coralline landscape. Here, the vibrancy and vitality of the corals emerge in all their colorful livelihoods. Healthy sympoiesis, the "making-with" each other, illuminates multi-species entanglements and co-dependence.4 Becoming-with each other, we flourish through "the intimacy of strangers".

Using crochet as the primary aesthetic technique, the eco-art installation renders visible the use of traditional crafts in environmental activism. Traditional crafts practices are informed by situated knowledges, wherein locality/location is central. Traditional craft practices commonly arise from locally sourced material and/or recovery of materials, as well as ethical modes of production and recycling, practices that intriguingly also speak to global sustainability goals.5 The Abundance Crochet Coral Reef embodies collaborative and entangled relations in the co-creation of intricate coralline landscapes. The ecological assemblage it projects extends an aesthetic invitation to visitors of the Two Oceans Aquarium to attend to the world through the process of worlding. That is, a way of being in the world that is attentive to our active and embodied engagement with materiality, a way of being that unsettles bodily boundedness, a way of being that troubles and makes porous the constructed boundaries between human-nature and nature-culture, and, instead, labors the connected and entangled nature of being and becoming-with other bodies.6

What does the eco-art-activism of crocheted coralline landscapes have to do with religion or the study of religion? I posit that The Abundance Crochet Coral Reef represents a rich methodological motif and enactment to think creatively about and with the study of religion in the Anthropocene. The Anthropocene denotes our current geological era of anthropogenic ecological disruption. However, there are good reasons to be critical about the universal and universalizing story of the human (Anthropos) that the concept of the Anthropocene conveys. A troubling concept in itself of locating humans at the center of being and belonging, it simultaneously erases histories of social inequalities and injustices. Furthermore, the concept of the Anthropocene highlights the extractivist modes that arguably mark (all) human cultures. My use of the concept of the Anthropocene in this article is reflective of feminist and decolonial critiques that maintain that particular configurations of gender, race and class - transported and transposed through imperialism, colonialism, racism, capitalist interests, and traditional forms of masculinity (patriarchy) - played a major role in creating this Anthropocene. Foregrounding indigenous knowledges and practices, feminist and decolonial scholarly work offers important correctives to the universalizing, human-centered and extractivist politics of the Anthropocene.7 Importantly, through their poignant critique of a universalizing anthropocentrism, feminist and decolonial scholars have crafted post-qualitative methodologies, reflective of feminist post-humanist and new materialist insights, which do much to destabilize anthropocentric and extractivist methodologies.

Methodology as a concept and approach suggests a way of understanding the world. Yet, on the one hand, methodology too, has been wrapped up in Enlightenment traditions that have taught us certain (and, indeed, correct) ways of knowledge making.8 Post-qualitative methodologies, on the other hand, invite us and challenge us to understand and think with the world differently. Foregrounding embodiment and entanglement as characteristic of any knowledge-making activity, post-qualitative methodologies shift our attention away from anthropocentric research objectives towards knowledge-making practices that takes seriously the relationalities between human and more-than-human materialities. Using crafts as a central component in sculpting new methodologies is one way in which alternative knowledge-making finds expression.9 My positing of The Abundance Crochet Coral Reef as a methodological motif and enactment, then, emerges from this post-qualitative turn of using arts and crafts as central for knowledge-making. Thinking with the collaborative eco-art-activism of The Abundance Crochet Coral Reef, opens up a creative nexus of worlding in the Anthropocene that can inform and reorient our scholarly gaze. Thinking with enables modes of thinking and practices that creatively explore the value of arts and crafts in knowledge making about religion, and, moreover, challenges us to think differently about religion and "the stuff of religion" in the Anthropocene.10 The Abundance Crochet Coral Reef as a methodological motif and enactment, what I will call crochet methodology, projects a material aesthetic, embodying the sympoiesis that births an expansive and entangled understanding of the world and of being. That is, being as modes of connection, being as co-being and co-becoming. Crochet methodology, I argue, offers the study of religion a creative and critical materialist response to inherited notions of human exceptionalism, atomistic legacies, and Enlightenment hierarchies that continue to ghost religious discourses and phenomena (and/or scholars' interpretive understandings of them), and continue to sustain the making of this Anthropocene.

I contend that the study of religion has much to say about and to the Anthropocene. I also contend that the Anthropocene requires us, scholars of religion, to think creatively about the stories we wish to tell about religion. What stories of religion matter in the age of the Anthropocene?

Scholars of religion are deeply invested in the telling of stories: stories about religion. In our scholarly conceptualizations of religion, that is, what religion is, what religion does and what purpose it serves, and in our storying about religion, we do, however, tend to move within methodologies and frameworks that are deeply anthropocentric. That is, our attention, our focus of study, our stories about religion, often centers on the human. We study religion by examining what people believe and what people do, through ritual enactment and practices. We study how religion is meaningful for people, how religion is navigated, and how religion is used, adapted, reconfigured, challenged, and renewed.

Through our extensive focus on humans, we often replicate and continue to perpetuate divisions and dualistic/hierarchical understandings of being, that is, between nature/culture, human/nature, human/animal, subject/object, and so on.11 Of course, saying that scholars of religion often tell stories about humans is not to say that folks within the study of religion have not developed concepts and engaged in studies that involve the more-than-human. On the contrary, I argue that a focus on the more-than-human has always been a central feature of religious studies storytelling. Scholars of religion are invested in exploring creation narratives, mythologies, the workings of the divine, Gods and Goddesses, spirit beings and spirit worlds, and so on. Nevertheless, cosmological and ontological explorations are still, more often than not, about humans. It is about how we came into being, and how we make sense of our being in the world.

Much work has already been done in the study of religion that foregrounds the various ways in which imperialism, colonialism, racism, sexism, capitalism, and traditional forms of masculinity (patriarchy) have informed religion and the study of religion.12 Yet, such work has primarily been concerned with documenting and, rightly, critiquing the history of constructing religious hierarchies, hierarchies of human beings including the gendered and racialized norms that continue to be perpetuated in and through religious discourses, by religious communities and individual religious persons. What would such critical work look like if more-than-human materialities featured more centrally? Storying into the entanglements of human and more-than-human relationalities, into human-nature entwinement, nature-culture permeability, and multi-species intimacy, I posit, is central to telling stories about religion that matter in the Anthropocene.

In keeping with The Abundance Crochet Coral Reef as a methodological motif and enactment, I argue that approaching religion and telling stories about religion with crochet methodology reorients the study of religion away from human exceptionalism and Enlightenment hierarchies towards a process of worlding the study of religion as a critical response to/in the Anthropocene.

Before I venture into feminist theory to further elaborate on perspectives and concepts that I consider useful for thinking creatively about and with the study of religion in the Anthropocene, I journey through current trends in a selection of fields in the study of religion that are responsive to Anthropocene concerns in different ways.

The Study of Religion in the Anthropocene: Some Critical Turns

Undoubtedly, there exists a vast and growing body of scholarly work that troubles the constructed dualisms and hierarchies of human-nature and nature-culture that have informed and, indeed, dominated conceptualizations about religion and the study of religion.13 Connectedly, research fields within the study of religion that are responsive to or engage with environmental challenges are well established and growing.14 Most notably, I would argue, is what some scholars have termed "the religious turn to ecology".15 In part, the religious turn to ecology was a response to Lynn White's publication, "The Historical Roots of our Ecological Crisis", in the renowned journal Science in 1967.16 In the article, White argues that Western Christianity, in particular, is a major cause of the global climate crisis. White's charge gave rise to heated debates in the study of religion and theology, about the role of religion in perpetuating dualistic worldviews and hierarchies (particularly that of human/nature) and the anthropocentrism/human exceptionalism that undergirds religious discourses. The theological project of "greening religion", that is, making religion more environmentally friendly (e.g. by ways of reinterpreting sacred texts, ritual creativity, the founding of green churches and mosques, and the like) took off.

Many theologians joined the green choir and stressed the need to recover the view of "this sacred earth" as foundational for environmental action and being in the world.17 Moreover, scholars within various theological disciplines poignantly drew attention to relationships of domination and exploitation, such as colonialism, imperialism, and patriarchy as having detrimental effects on the environment. That is, such relationships of domination and exploitation solidify dualistic and hierarchical relations (like human/nature) that inform and normalize (theological) conceptualizations of, in this instance, nature as Other. Conceptualizations of nature as Other and the (hu)man exceptionalism that have permeated theological discourses, theologians argued, have shaped the ways in which we, (hu)mans, have related to everything else.18 Theologians took to task theological anthropology, creation narratives and sacred texts as one way to deconstruct and reconstruct theology through an environmental lens. For many theologians, the recovery of historical (and mythical) figures who embodied different ways of being, that is, ways of being that were not characterized by and through relationships of domination and exploitation, became important. Foregrounding figures like Saint Francis of Assisi, Hildegard of Bingen, and the Prophet Muhammed - although all human (!) - did the work of positing figures whose being in the world was characterized by a humble relationality to their surrounding environments.19

Theological work, at least in its early articulations, was concerned with deconstruction to make way for reconstructive and responsive eco-theologies. Scholars were invested in looking anew at theological ethics to expand the field of ethics to include environmental concerns.20 Such endeavors found more practical expressions through the publication of "how-to" manuals and guides aimed at religious communities and leaders and, for lack of a better description, "self-help" handbooks aimed at individual believers who wished to become green, religious practitioners.21

Scholarly networks, like the Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology (founded by Mary Evelyn Tucker and John Grim), the Center for the Study of World Religions at Harvard Divinity School, and the International Society for the Study of Religion, Nature, and Culture (ISSRNC), primarily motivated by Bron Taylor and the academic milieu connected to the Graduate Programme in Religion and Nature at the University of Florida, resulted in the establishment of the field of "religion and ecology", alternatively "religion and nature", as a vibrant sub-discipline within the study of religion. ISSRNC, in particular, broadened the scope of scholarly engagement by positioning itself as an intersectional and interdisciplinary society, extending invitations not only to scholars of religion and theology but also to cultural anthropologists, historians, literary scholars, ethicists, and scholars in the life sciences. The scholarly networks named here produced a great number of publications and inspired the establishment of the Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture (up until 2007 named Ecotheology), housed by ISSRNC. Returning to, what I posit as, the need to trouble the dualisms and hierarchies of human-nature and nature-culture in the study of religion, I believe that scholarly networks like the ISSRNC and the Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture, in particular, provide critical perspectives to studying religion, broadly understood, through its relationality and co-becoming with everything else. That is, the ways in which religion, as discourse and materiality, is never a stable or fixed category but unfolds and co-becomes through its relationality with people, societies, and environments, categories that are, also, always continuously intertwined, changing, and co-becoming. On the Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture website, the description states that the journal explores "the complex relationships among human beings, their diverse 'religions' and the earth's living systems, while providing a venue for analysis and debate over what constitutes an ethically appropriate relationship between our own species and the environments we inhabit".22 Such a focus does, indeed, trouble human exceptionalism by positing, as a key node, a much more complex and entangled lifeworld.

Of course, although the field of African Traditional Religion (ATR) and ecology can be said to be an integral part of the established field "religion and ecology", I believe it is important to foreground networks and scholarship on ATR and ecology to illustrate the dynamic ways in which environmental concerns are central to the study of religion on the African continent. Notably, the African Association for the Study of Religions (AASR), a scholarly network that focuses on the study of religion in Africa, has, through their biannual conferences, been increasingly attentive to environmental concerns. In 2014, I was lucky to be on the program committee for the 6thAfrican Association for the Study of Religions Conference in Africa held in Cape Town. The theme for the conference was "Religion, Ecology, and the Environment in Africa and the African Diaspora". Following on the theme "Religion, Environment and Sustainable Development" of the 4th AASR conference in Ile-Ife, Nigeria in 2009, the AASR wished to "underscore its commitment to the growing environmental crisis and the impact it has on all areas of life and society in Africa and the African Diaspora".23 In 2023, the 9th African Association for the Study of Religions Conference in Africa, held at the University of Nairobi, Kenya, included four panels as well as a number of individual papers that engaged with the theme of African ecologies and religion/eco-spiritualities. The contributions covered a broad range of topics, from literary and soundscape eco-poetics to case studies of religious responses to the environmental crisis and eco-spirituality as conservational praxis. Many contributors raised critical questions concerning the challenge of monoculturalization, an effect of colonial and imperial expansion on ecological knowledges, and the role of African traditional religion in preserving such knowledges. Contributions spoke to the politics of location and situated knowledges and visited historical and contemporary archives of religious eco-practices. Moreover, many papers troubled the tendency to romanticize African traditional religions' eco-affirming cosmologies by illustrating the various ways in which certain practices (for example, ritual sacrifice), negatively affect local ecologies.24

The contributions engaging with the theme of African ecologies and religion, under the banner of the AASR, are reflective of the growing interest and central importance of environmental matters in the study of religion on the African continent. Additionally, scholarship on ATR and ecology is critical for worlding the study of religion for, at least, the following four reasons:

(1) The field of ATR and ecology frequently talks back to the paradigm of "world religions" embedded in the study of religion, and, certainly in its early stages, the presence of the "world religions" paradigm in the field of "religion and ecology";25

(2) it offers poignant critiques of imperialism and colonialisms in conversation with concerns of traditional religions and the environment;

(3) as a field it is responsive to an environmental crisis that is happening (we are in it, as opposed to a crisis that is perceived to be coming); and

(4) ATR and ecology offers complex cosmologies and entanglements of relationships that involve deities, spirit beings, ancestors, humans, animals, and nature/environments.

This is not to say that these webs of relationships are perceived or projected to exist in harmony by romanticizing African worldviews for their inherent nature and more-than-human-affirming qualities. Rather, the complexity of cosmologies and entanglements of relationships offer possibilities for methodologies that unsettle the dualisms and hierarchies (e.g. human/nature) that dominate conceptualizations of religion and the study of religion. Interestingly, as we currently witness a turn to indigenous knowledges as critical sources of ecological knowledge (also from the sciences), we are reminded of the complicated ways in which knowledge travels and the parochial ways in which knowledges are validated as "scientific" or "true". The field of ATR and ecology is well positioned to trouble the romanticizing and exploitative efforts of knowledge-making along downtrodden imperial and colonial trade routes.

Another field in the study of religion that is similarly well-positioned to offer perspectives and concepts that disrupt and rupture normative, hegemonic, and essentializing conceptions of being and becoming is that of feminist studies in religion. Feminist scholars of religion have widely documented past and present forms of erasure, marginalization, and silencing of women's knowledges and voices. As such, feminist scholarship challenges us to be critical of our epistemological truths by making us conscious of our situated knowledges, our location and positioning in the world.

Feminist thinking has, over many years, problematized the relationship between humans and nature, not the least within the field of ecofeminism with its particular attention to the "logic of domination" that speaks to the parallel domination of humans over nature and men over women.26 In short, although quite simplistically, ecofeminist thinking has engaged the splitting apart, the tear between humans and nature that through the philosophical, theological, and scientific discourses of the Enlightenment period became normalized. According to ecofeminist thinking, the concept of dualism has informed much western thinking and philosophizing about the human. Dualism, understood as a separation or splitting apart of a unit, is often traced back to René Descartes (1596-1650), who contemplated the distinction between the body and the mind (something both Plato and Aristotle did in similar ways before him). The Cartesian separation of the human did not only imply a distinction between two equal parts, the body, and the mind, but introduced a hierarchy wherein the body was inferior to the mind. The mind was the location of reason and rationality, the place where the human as a subject came into being. The body, on the other hand, became the object of the mind, a passive materiality without agency. The body became transformed into uncultivated and uncontrollable nature that needed to be disciplined. The mind represented culture. The mind represented the enlightened, civilized, and agentival subject.27

Ecofeminist readings of Cartesian dualism have led to the identification and problematization of a number of other dualisms that, arguably, are similarly premised on the mind/body dualism. One of them is that of human/nature in western philosophical and scientific tradition. The dualism implies that the human is conceptualized as both outside and above nature. The human is the ruler of nature. Nature is inferior. Nature is not-human, not-culture. Nature stands in opposition to the mind, to reason, to the rational and civilized human. Nature is irrational, it has no reason. Nature is wild and rebellious and must naturally be disciplined and subjugated.28

In her landmark publication, Feminism and the Mastery of Nature (1993), philosopher and ecofeminist Val Plumwood argues that the human/nature dualism stimulated the West's brutal treatment of nature. Plumwood contends that dualisms such as this modelled the western modern political world. Nature, as a concept during the Enlightenment period, did not only concern non-humans but also extended to different groups of humans and human practices perceived to be uncivilized or animalistic. That is, gender, race, and ethnic differences determined the degree of humanness. Some groups of people were perceived to be closer to nature than others and, as such, were considered naturally inferior to the human who came into being through the logic of reason and rationality. The dualism of human/nature contained in this way several other separations: culture/nature, reason/nature, reason/materiality, subject/object, civilized/primitive, production/reproduction, master/slave, and man/woman. All similarly maintained a hierarchy where one category was considered superior.29

From an ecofeminist vantage point, these dualisms, or separations, did not merely operate conceptually under the umbrella of a western philosophical tradition. The dualisms became realities, they became materialized and enfleshed through the development of imperialist and colonial projects. Nature and humans were subjugated. Nature and some groups of humans were managed and constituted resources that could be exploited.

The association between woman and nature, or woman as nature, has long and deep-rooted traditions. In Earthcare: Women and the Environment (1996), Carolyn Merchant engages with the various ways in which woman as nature has been symbolized through historical-mythological characters such as Gaia, Eve, and Isis.30 Using Eve as an example, Merchant notes that Eve, as a virgin in the Biblical universe, symbolized innocence and "untouched nature" on the one hand. As a fallen woman, on the other hand, she symbolized a "barren desert". Eve, as a mother, symbolized a "planted garden...a ripened, fruitful world".31 While the Fall (that Eve was blamed for) transformed the Garden of Eden into a depleted wasteland. Adam and Eve were evicted from the garden, God appointed man to be the ruler of woman. The man was the guardian of reason. The woman was irrational, a temptress driven by bodily desires. Eve, the temptress, symbolized the sinful human. She caused the human expulsion from paradisiacal existence to earth-boundedness.

The Garden necessarily needed to be re-created, Carolyn Merchant argues. 32 The Christian tradition (with its connections to imperialist and colonial projects), together with science, capitalism, and technology, can be read from an ecofeminist standpoint as a story about re-creating the Garden of Eden on earth. In this story, the earth must be improved, the soil must be cultivated, wilderness must be de-wilded and ploughed, and deserts must be watered.33 In this story a woman knows her place as inferior to the man. She must also be de-wilded, ploughed, impregnated, and give birth to the children of the patriarch that belong to him as his property.

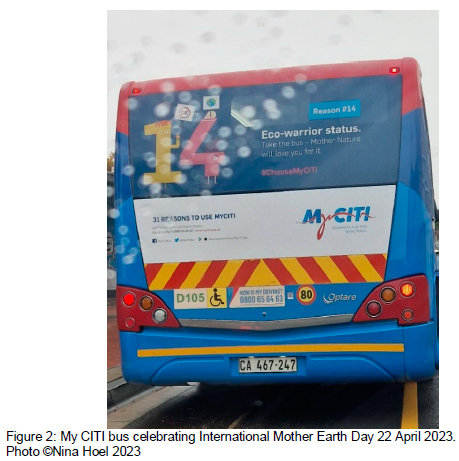

The feminization of earth and nature is not necessarily archaic or out-of-sync with contemporary society, as many may think. We find similar symbols and illustrations in popular culture as well as throughout political discourses. In 2009, the UN established the International Mother Earth Day (22 April) to remind the world population that the earth gives us life and sustenance. In Cape Town earlier this year (2023), International Mother Earth Day was marked, amongst other events and performances, by the My CITI bus service, which proudly proclaimed "eco-warrior status" and drove around the inner city carrying the slogan: "Take the bus - Mother Nature will love you for it."

Ecofeminist thinking and theorizing has done much to raise awareness in the study of religion and theology about the place of nature and of women. In so doing, ecofeminists have simultaneously rendered visible the entangled forms of oppression at work under the auspices of the logic of domination. Ecofeminist theologians, such as Heather Eaton and Ivone Gebara, have presented radical, theological, earth-centered-approaches where dualisms and hierarchical religious categories are destabilized and eschewed in favor of cosmologies that speak to vibrant networks of complexly embodied relationships between humans and the more-than human.34 Foregrounding embodiment, ecofeminists' rich reconceptualizations of theology importantly contribute to processes of worlding religion. Imagining cosmologies, not as a "given" but, rather, as emerging and co-evolving, ecofeminists present us with fruitful understandings of entangled life-worlds and being.

Feminist Theory in the Anthropocene: Crocheting Methodological Openings for the Study of Religion

Why look to feminist theory and crochet methodology when so much interesting work pertaining to religion and the environment already exists in the study of religion? As the previous section shows, there has been a growing interest in environmental issues within the study of religion, and much work has already been done on broadening the units of analysis to include materiality, relationality, locatedness, and human interdependence with more-than-human concerns. While I maintain that there exists a richness within the study of religion that bodes well for religion scholarship to tell stories about religion that are responsive to Anthropocene concerns, I also contend that there is much to learn methodologically about ways of approaching more-than-human relationalities in religion by looking to feminist theory.

In her chapter "The Future of Feminist Theory: Dreams for New Knowledges", feminist philosopher, Elizabeth Grosz, beautifully and engagingly probes the various ways in which feminist theory holds the potential to generate concepts that "enable us to surround ourselves with the possibilities for being otherwise".35 Relatedly, Donna Haraway, drawing on social anthropologist Marilyn Strathern's work, writes in Staying with the Trouble that "[i]t matters what stories make worlds, and what worlds make stories".36 Feminist theorizing in the Anthropocene often starts with stories and, in many ways, feminism in the Anthropocene is about telling stories and re-telling stories to contribute to the project of worlding, that is, making worlds that can hold deeply entangled lives. I turn to feminist theory to continue pushing our reimagining of methodologies in religion, and to in-tune and responsibly attune our storytelling about religion to the challenges of the Anthropocene.

Just as the material aesthetic of The Abundance Crochet Coral Reef births and extends an expansive and entangled understanding of the world and of being bodies enfolded within one another, feminist theorizing in the Anthropocene foregrounds bodily entanglements. That is, entanglements between humans and environments, between humans and the more-than-human, and entanglements between pasts and presents, and the possibilities these entanglements offer for worlding. Feminist theorizing attends to bodily materiality in a way that connects it to environmental concerns. Through the lenses of feminist posthumanism and hydrofeminism, bodily materiality and the environment are not separate; they are entangled, embodied, and evolve through mutual conditioning.37 At the same time, as noted when introducing the concept of the Anthropocene in the introduction of this article, the Anthropocene is not a singular narrative about human entanglements with the geological. The Anthropocene, read through feminist lenses, reminds us that our common/shared human history is not the history of everybody. As also widely documented by feminist scholars in religion, many groups of humans were deliberately excluded, marginalized and de-humanized. If anything, the Anthropocene - the age of humans - is brutally inhuman.

Feminist theorizing in the Anthropocene is, thus, also about problematizing the universal and universalizing story of the Anthropocene. That is, that humans (as a species) have changed the planet for the worse. The Anthropocene as an Age, then, runs the risk of re-universalizing the human and human relationships with the more-than-human. For feminism then, it is important that such a conflation, or thinning, of the narrative is challenged by foregrounding the various ways in which imperialism, colonialism, racism, capitalist interests, and traditional forms of masculinity (patriarchy) are deeply intertwined in the making of this Anthropocene.38 Feminist thinking in the Anthropocene is about illuminating these tangles, the human-centered discourses that have modelled and continue to model human relations with the more-than-human.

The contemporary climate challenges make it necessary to consider humans as a species. Not because the human species is what unites us (that would be the universal story), but because our very existence is conditioned through our coexistence/co-becoming/becoming with the more-than-human. We, too, embody "the intimacy of strangers". Feminist theorizing in the Anthropocene is about turning the gaze outwards, away from our limited understandings of ourselves, so that we can develop ways of thinking, ways of being with, becoming with the more-than-human, and think new forms of kinship, making kin across species distinctions. Becoming with is, quite simply, about the recognition that we, I, or the more-than-human are a result of several complex and entangled relations and intimacies. To be, is to be in relation, all the time. Relationality with the more-than-human is the starting point or, more precisely, a continuity that makes it possible to know anything about anything at all.

The relational has, in feminist thinking, been given a central space in the theorization and conceptualization of the body. When it comes to the human body, it does not necessarily stop at the surface: the skin. With cultural theorist and hydrofeminist, Astrida Neimanis, we might conceive of ourselves as "bodies of water", connected through "webs of physical intimacy and fluid exchange".39 Expansive conceptualizations of the human body perforate bodily membranes that sustain environmental disconnect; this outer layer of skin that is me, the demarcation that separates me from everything else, my boundedness is an illusion. What is the human body, really, if not part of everything else? The body emerges from, is shaped through, and shares kinship and genealogy with other biological material and abiotic factors (like electricity, light, and temperature). We gestate, ingest, and digest our surrounding environments through the food and liquid we devour. Our bodies leak. We are penetrable. We have microplastics in our blood, heavy metal in our liver, and particulate matter in our lungs. Our bodies are hybrids, cyborgs, its materiality fragmented. Some of us have pacemakers to survive, hip prosthesis to walk, or veneers to make our teeth look pretty.

The relational plasticity of the human body and its entanglements with the more-than-human entered feminist theorizing from the mid-1980s with Donna Haraway's theorization of the cyborg (cybernetic organism), a hybridization of a living being and machine.40 The figuration of the cyborg troubled and opened the rigid separation between skin and metal, between the human body and machine. Although Haraway's conceptualization of the cyborg emerged through her contemplation of destructive materialities, such as modern warfare and weapons production, the cyborg as a figuration was intended to weave together fantasy and material reality. In this way, the cyborg embodies an enmeshment of the imagined and the real that pushes us to confront and destabilize the dualisms that inform our being in the world.

On the basis that the cyborg complicates the ontological separation between human and machine, Haraway argues that the cyborg as a metaphor hold the potential to dissolve dualisms like man/woman, technology/nature, and life/non-life.41 The materiality of the cyborg, as a fragmented and complexly composed body, introduced new ways to theorize the relational, the entangled, and the hybrid. In this sense, the cyborg functions as one of (potentially) many metaphors, a thinking tool, that contributes to the feminist project of thinking new forms of kinship in the Anthropocene. Kinship in this way is not only about acknowledging humans as being part of relations with the more-than-human or that the relations we are part of condition life and death. Kinship is also about cultivating an expanded understanding of responsibilities and commitments. We have many examples of forms of kinship that expand conceptions of the nuclear family or the family tree, for example, perhaps particularly associated with various indigenous populations whose understandings of kinship include kinship with the land, with animals and the environment more broadly, and with connected responsibilities and duties, in addition to other humans, both living and the living-dead (or ancestors).42

Of course, we cannot become kin or share kinship with everything or everyone. Through our bodies and our positioning in the world, we are situated in time, in space, in matter. We are already part of several different networks that are earthbound, placebound, and timebound. Kinship thought of in this way can include companion species such as a domestic animal or other animal-beings. Indeed, kinship can emerge with the apple tree that was planted when my grandfather passed away, or with the pine tree at the end of the road that in a memory resound the pecking of a woodpecker, or the mussels along the shore that tore into my feet, or the mountain of trash that, for millions of people, is livelihood and home. Kinship is then not only about life, but also about death; the expulsion of the "stranger" that sustains us. In feminist thinking about kinship, the story about the human is refocused to become a story about being, living and dying with companion-species, and with more-than-human materialities.

Crocheting the Study of Religion

How can we do religious studies in a more multi-species way? How can we reconfigure and expand/stretch our methodologies and our concepts so as to take the more-than-human more seriously? How do we go about doing this in ways that de-center human exceptionalism and the philosophical and scientific discourses that inform our thinking about religion? This article has proposed The Abundance Crochet Coral Reef as a methodological motif and enactment to think creatively with and about the study of religion in the Anthropocene. My imagining of crochet methodology is meant as an aesthetic illustration of the possibilities for thinking (and being) otherwise, an opening to think-with and meditate more-than-human relationalities; a call to partake in responsive scholarship in this age of the Anthropocene. Crochet methodology, I argue, can push us to shift our point of entry from engaging human concerns to that of the entangled concerns with the more-than-human. By positing a methodological motif and enactment that vividly projects becoming-with as foundational for all that is, I hope to encourage scholars of religion to tell stories about religion that are attentive to the complexity and messiness of religious life-worlds. Partaking in processes of worlding religion is to be attentive to religion as a relational and embodied "category". Religion is never fixed, but unfolds and co-becomes with people, societies, and environments. Religion, too, it can be argued, exists only through the "intimacy of strangers" that co-create, embody, and animate local environments.

The Abundance Crochet Coral Reef as a methodological motif and enactment, draws our attention to kinship, being, and becoming with each other. It draws our attention to the process of sympoiesis. In this article, I have engaged feminist conceptualizations of kinship to illustrate potential sites and possibilities for multi-species thinking. Such imaginings of embodied relationalities do much to de-center human exceptionalism and provide figurative resources for scholars in religion to delve into the rich archives of religious cosmologies, cartographies, and aesthetics. Indeed, feminist imaginings of kinship are arguably echoed in the field of ecofeminism and religion and ecology, and perhaps, in particular, in the field of African Traditional Religion and ecology. With crochet methodology, I believe in the collaborative and co-creative efforts of knowledge collectives to storying religion in ways that increasingly trouble the power relations that continue to sustain this Anthropocene.

References

Abdul-Matin, Ibrahim. GreenDeen: What Islam Teaches About Protecting the Planet. San Francisco, CA.: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2010. [ Links ]

African Association for the Study of Religions, https://www.a-asr.org/. Accessed October 30, 2023. [ Links ]

Barad, Karen. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2007. [ Links ]

Bardhan, A. and A. Bhattacharya. "Role of Traditional Crafts in Sustainable Development and Building Community Resilience: Case Stories from India." Culture. Society. Economy. Politics, 2, no. 1 (2022): 38-50. https://doi.org/10.2478/csep-2022-0004. [ Links ]

Barnhill, David Landis and Roger S. Gottlieb. Deep Ecology and World Religions: New Essays on Sacred Grounds. Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press, 2001. [ Links ]

Beaman, Lori G. and Lauren Strumos, "Toward Equality: Including Non-Human Animals in Studies of Lived Religion and Nonreligion," Social Compass, 2023: 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1177/00377686231170993. [ Links ]

Braidotti, Rosi. The Posthuman. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2013. [ Links ]

Chidester, David. Savage Systems: Colonialism and Comparative Religion in Southern Africa. University Press of Virginia, 1996. [ Links ]

Chidester, David. Empire of Religion: Imperialism and Comparative Religion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014. [ Links ]

Chidester, David. Religion: Material Dynamics. Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2018. [ Links ]

de la Cadena, Marisol. Earth Beings: Ecologies of Practice across Andean Worlds. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015. [ Links ]

Demos, T. J. Against the Anthropocene: Visual Culture and Environment Today. Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2007. [ Links ]

Eaton, Heather. Introducing Ecofeminist Theologies. New York: T&T Clark International, 2005. [ Links ]

Gebara, Ivone. Longing for Running Water: Ecofeminism and Liberation. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1999. [ Links ]

Gottlieb, Roger S. This Sacred Earth: Religion, Nature, Environment. New York: Routledge, 1996. [ Links ]

Grim, John (ed.). Indigenous Traditions and Ecology: The Interbeing of Cosmology and Community. Cambridge, Mass.: Distributed by the Harvard Press for the Centre for the Study of World Religions, 2001. [ Links ]

Gross, Rita. Feminism and Religion: An Introduction. Boston: Beacon Press, 1996. [ Links ]

Grosz, Elisabeth. "The Future of Feminist Theory: Dreams for New Knowledges", in H. Gunkel, C. Nigianni, and F. Soderback (eds.), Undutiful Daughters: New Directions in Feminist Thought and Practice. New York: Palgrave, Macmillan, 2012, 13-22. [ Links ]

Halberstam, Jack. Wild Things: The Disorder of Desire. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2020. [ Links ]

Hasan, Heba. "Islam and Ecological Sustainability: An Exploration into Prophet's Perspective on Environment," Social Science Journal for Advanced Research 2.6 (2022): 9-14. DOI: 10.54741/ssjar.2.6.3. [ Links ]

Haraway, Donna. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2016. [ Links ]

Haraway, Donna. "Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective," Feminist Studies, 14(3) (1988): 575-599. [ Links ]

Haraway, Donna, "A Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology and Socialist Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century", Socialist Review, 80 (1985): 65-108. [ Links ]

Hinton, Peta and Iris van der Tuin, "Feminist Matters: The Politics of New Materialism," Women: A Cultural Review 25.1 (2014). [ Links ]

Hoel, Nina. "Feminisme i Antropocen", in Marius Timmann Mjaaland, Thomas Hylland Eriksen og Dag O. Hessen (eds.), Antropocen. Menneskets tidsalder. Oslo: Res Publica, forthcoming January 2024, 131-149. [ Links ]

Hoel, Nina and Elaine Nogueira-Godsey. "Transforming Feminisms: Religion, Women and Ecology," Journal for the Study of Religion 24.2 (2011): 5-16. [ Links ]

Institute for Figuring. "Crochet Coral Reef." Accessed October 30, 2023. https://crochetcoralreef.org/about/theproject/ [ Links ]

Jenkins, Willis. The Future of Ethics: Sustainability, Social Justice and Religious Creativity. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 2013. [ Links ]

Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture, https://journal.equinoxpub.com/JSRNC. Accessed October 30, 2023. [ Links ]

Kimmerer, Robin Wall. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants. Minneapolis, MN: Milkweed Editions, 2013. [ Links ]

Kirby, Vicky. Quantum Anthropology: Life at Large. Durham: Duke University Press, 2011. [ Links ]

Marder, Michael. Green Mass: The Ecological Theology of St. Hildegard of Bingen. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2021. [ Links ]

Margulis, Lynn. Symbolic Planet. A New Look at Evolution. New York, NY: Basic Books, 1998. [ Links ]

McMenamin, Mark and Dianna McMenamin. Hypersea. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994. [ Links ]

Merchant, Carolyn. Earthcare: Women and the Environment. London: Routledge, 1996. [ Links ]

Moore, Jason (ed.). Anthropocene or Capitalocene? Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism. Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2016. [ Links ]

Nasr, Seyyed Hossein. Man and Nature: The Spiritual Crisis of Modern Man. London: Unwin Paperbacks, 1976. [ Links ]

Neimanis, Astrida. Bodies of Water: Posthuman Feminist Phenomenology. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. [ Links ]

Neimanis, Astrida. "Hydrofeminism: Or, on Becoming a Body of Water," in H. Gunkel, C. Nigianni, and F. Soderback (eds.), Undutiful Daughters: New Directions in Feminist Thought and Practice. New York: Palgrave, Macmillan, 2012, 85-99. [ Links ]

Neimanis, Astrida and Rachel Loewen Walker, "Weathering: Climate Change and the 'Thick Time' of Transcorporality," Hypathia: A Journal of Feminist Philosophy, 29.3 (2014): 558-575. [ Links ]

Pérez-Bustos, Tania and Andrea Bello-Tocancipá. "Thinking Methodologies with Textiles, Thinking Textiles as Methodologies in the Context of Transitional Justice," Qualitative Research, Nov 30 2023, OnlineFirst, 1-21. DOI: 10.1177/14687941231216639. [ Links ]

Plumwood, Val. Feminism and the Mastery of Nature. London: Routledge, 1993. [ Links ]

Rasmussen, Larry L. Earth-Honoring Faith: Religious Ethics in a New Key. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013. [ Links ]

Romano, Nike, Vivienne Bozalek and Tamara Shefer (eds.), CriSTaL (Critical Studies in Teaching and Learning) Special Issue: Thinking with Ocean/s for Reconceptualising Scholarship in Higher Education, 11, 2 (2023). DOI:10.14426/cristal.v11iSI2.722. [ Links ]

Ruether, Rosemary Radford. New Woman, New Earth: Sexist Ideologies and Human Liberation. New York: Seabury Press, 1975. [ Links ]

Segalo, Puleng. "Embroidered Voices: Exposing Hidden Trauma Stories of Apartheid," TEXTILE, 21.2 (2023): 422-434. DOI: 10.1080/14759756.2022.2036071. [ Links ]

Segalo, Puleng. "Using Cotton, Needles and Threads to Break the Women's Silence: Embroideries as a Decolonising Framework," International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20.3 (2016): 246-260. DOI: 10.1080/13603116.2015.1047661. [ Links ]

Teague, Ellen. Becoming a Green Christian. Kevin Mayhew Ltd., 2009. [ Links ]

Tsing, Anna. "Earth Stalked by Man," Cambridge Anthropology 34.1 (2016): 2-16. [ Links ]

Tsing, Anna. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015. [ Links ]

Tucker, Catherine M. and Adrian J. Ivakhiv, "Intersections of Nature, Science, and Religion: An Introduction", in Nature, Science, and Religion: Intersections Shaping Society and the Environment. Santa Fe, N.M.: SAR Press, 2012. [ Links ]

Viviers, Hendrik. "The Second Christ, Saint Francis of Assisi and Ecological Consciousness," Verbum Et Ecclesia 35, no. 1 (2014): 1-9. [ Links ]

Warren, Karen, Ecological Ecofeminism. New York: Routledge, 1994. [ Links ]

White, Lynn. "The Historical Roots of our Ecological Crisis," Science 155(3767): 1203-1207. [ Links ]

Wildcat, Daniel R. Red Alert! Saving the Planet with Indigenous Knowledge. Golden, CO: Fulcrum, 2009. [ Links ]

Submission date: 1 November 2023

Acceptance date: 18 December 2023

i Nina Hoel is Associate Professor in Religion and Society at the Faculty of Theology, University of Oslo. Her research focuses on the entanglements of religion, gender and sexuality, and religion and feminism in the Anthropocene. In 2020 she published the monograph Religion, the Body and Sexuality: An Introduction, co-written with Melissa Wilcox and Liz Wilson.

1 Parts of certain sections in this article (ecofeminism and feminist theory in the Anthropocene) have been prepared in slightly revised versions for a book chapter in Norwegian entitled "Feminisme i Antropocen" (English: "Feminism in the Anthropocene") to be published as part of the anthology Antropocen. Menneskets tidsalder (English: The Anthropocene. The Age of Humans), edited by Marius Timmann Mjaaland, Thomas Hylland Eriksen and Dag O. Hessen (Oslo: Res Publica, forthcoming January 2024), 131-149.

2 The Crochet Coral Reef Project, initiated by the twin sisters Margaret Wertheim and Christine Wertheim of the Institute for Figuring in Los Angeles, USA, is an eco-art response to climate change. Blending crocheted yarn with plastic trash, the installations draw on "mathematics, marine biology, feminist art practices, and craft to produce large-scale coralline landscapes". After its inception at the Institute for Figuring, a number of "satellite reefs" emerged all over the world, among them the Satellite Reef in Cape Town in 2010. See, Institute for Figuring, "Crochet Coral Reef". Accessed October 30, 2023. https://crochetcoralreef.org/about/theproject/.

3 See, Lynn Margulis, Symbolic Planet. A New Look at Evolution (New York, NY: Basic Books, 1998).

4 For a more thorough engagement with the notion of sympoiesis (making-with), see Donna Haraway, particularly chapter three titled "Sympoiesis: Symbiogenesis and the Lively Arts of Staying with the Trouble" in Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2016).

5 For an intriguing discussion (and case study) on the relationships between traditional crafts and sustainability, see A. Bardhan and A. Bhattacharya, A., "Role of Traditional Crafts in Sustainable Development and Building Community Resilience: Case Stories from India," Culture. Society. Economy. Politics, 2, no. 1 (2022): 38-50. https://doi.org/10.2478/csep-2022-0004.

6 For scholarly engagements on worlding, I find particularly useful perspectives and thinking emerging from feminist new materialism. See, amongst others, Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2007); Peta Hinton and Iris van der Tuin, "Feminist Matters: The Politics of New Materialism," Women: A Cultural Review 25.1 (2014); Vicky Kirby, Quantum Anthropology: Life at Large (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011); and, Astrida Neimanis and Rachel Loewen Walker, "Weathering: Climate Change and the 'Thick Time' of Transcorporality," Hypathia: A Journal of Feminist Philosophy, 29.3 (2014): 558-575.

7 For excellent scholarly discussions and critiques pertaining to the concept Anthropocene, see, Haraway, Staying with the Trouble; Jason Moore (ed.), Anthropocene or Capitalocene? Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism (Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2016); Anna Tsing, "Earth Stalked by Man," Cambridge Anthropology 34.1 (2016): 2-16; and T. J. Demos, Against the Anthropocene: Visual Culture and Environment Today (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2007). For scholarly work that foregrounds indigenous knowledges and practices in relation to the Anthropocene and anthropogenic ecological disruption, see, Marisol de la Cadena, Earth Beings: Ecologies of Practice across Andean Worlds (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015); Daniel R. Wildcat, Red Alert! Saving the Planet with Indigenous Knowledge (Golden, CO: Fulcrum, 2009); Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants (Minneapolis, MN: Milkweed Editions, 2013).

8 An invocation that recalls Donna Haraway's idiomatic "God's eye view from nowhere", which, arguably, undergirded and dominated the application of scientific methodologies. Haraway, of course, critiqued this position and suggested, instead, that all knowledge is situated, located, and partial. See Donna Haraway "Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective," Feminist Studies, 14(3) (1988): 575-599.

9 For excellent examples of methodologies where craft is central to knowledge-making, see Tania Pérez-Bustos and Andrea Bello-Tocancipá, "Thinking Methodologies with Textiles, Thinking Textiles as Methodologies in the Context of Transitional Justice," Qualitative Research, Nov 30 2023, OnlineFirst, 1-21; in South Africa, see, Puleng Segalo, "Embroidered Voices: Exposing Hidden Trauma Stories of Apartheid," TEXTILE, 21.2 (2023): 422-434; and "Using Cotton, Needles and Threads to Break the Women's Silence: Embroideries as a Decolonising Framework," International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20.3 (2016): 246-260.

10 I borrow the phrase, "the stuff of religion" from David Chidester, Religion: Material Dynamics (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2018), 2 and 79.

11 See, for example, Lori G. Beaman and Lauren Strumos, "Toward Equality: Including Non-Human Animals in Studies of Lived Religion and Nonreligion," Social Compass, 2023: 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1177/00377686231170993.

12 On religion and imperialism/colonialism, see David Chidester, Savage Systems: Colonialism and Comparative Religion in Southern Africa (University Press of Virginia, 1996) and Empire of Religion: Imperialism and Comparative Religion (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014); On religion and feminist perspectives, see the classical Rita Gross, Feminism and Religion: An Introduction (Boston: Beacon Press, 1996); for more recent scholarly work that also engages in issues of queerphobia, transphobia, and racism see, Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion and, of course, African Journal of Gender and Religion.

13 For an article that traces the history and outlines central dimensions of the field of "religion and ecology", while also troubling the dualisms and hierarchies of human-nature and nature-culture, see, Nina Hoel and Elaine Nogueira-Godsey, "Transforming Feminisms: Religion, Women and Ecology," Journal for the Study of Religion 24.2 (2011): 5-16.

14 This section should not be read as an exhaustive account of what is happening in the study of religion in terms of trends in the field. Notions like the "animal turn" and the "material turn" in the study of religion, not covered in this article, also do much to unsettle inherited dualisms. The trends engaged in this article are not watertight containers. Rather, they inform each other, and are co-evolving and interdisciplinary, drawing on multiple intersecting methodological and theoretical frameworks.

15 See, Catherine M. Tucker and Adrian J. Ivakhiv, "Intersections of Nature, Science, and Religion: An Introduction", in Nature, Science, and Religion: Intersections Shaping Society and the Environment (Santa Fe, N.M.: SAR Press, 2012).

16 Lynn White, "The Historical Roots of our Ecological Crisis," Science 155(3767): 1203-1207.

17 See, for example, Roger S. Gottlieb, This Sacred Earth: Religion, Nature, Environment (New York: Routledge, 1996); Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Man and Nature: The Spiritual Crisis of Modern Man (London: Unwin Paperbacks, 1976); and the anthology, by by David Landis Barnhill and Roger S. Gottlieb, Deep Ecology and World Religions: New Essays on Sacred Grounds (Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press, 2001).

18 See, for example, Rosemary Radford Ruether's New Woman, New Earth: Sexist Ideologies and Human Liberation (New York: Seabury Press, 1975).

19 On Saint Francis of Assisi, see, for example, Hendrik Viviers, "The Second Christ, Saint Francis of Assisi and Ecological Consciousness," Verbum Et Ecclesia 35, no. 1 (2014): 1-9; on Hildegard of Bingen, see, for example, Michael Marder, Green Mass: The Ecological Theology of St. Hildegard of Bingen (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2021); on the Prophet Muhammed, see, for example, Heba Hasan, "Islam and Ecological Sustainability: An Exploration into Prophet's Perspective on Environment," Social Science Journal for Advanced Research 2.6 (2022): 9-14.

20 See, for example, Willis Jenkins, The Future of Ethics: Sustainability, Social Justice and Religious Creativity (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 2013) and Larry L. Rasmussen, Earth-Honoring Faith: Religious Ethics in a New Key (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013).

21 One example is Ibrahim Abdul-Matin's publication of GreenDeen: What Islam Teaches About Protecting the Planet (San Francisco, CA.: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2010), which gives the reader information and advice on how to go about greening a mosque. Another example is Ellen Teague's Becoming a Green Christian (Kevin Mayhew Ltd., 2009).

22 See, Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture, https://journal.equinoxpub.com/JSRNC. Accessed October 30, 2023.

23 African Association for the Study of Religions Conference in Africa, conference program Cape Town 2014, https://www.a-asr.org/. Accessed October 30, 2023.

24 African Association for the Study of Religions Conference in Africa, conference program Nairobi 2023, https://www.a-asr.org/. Accessed October 30, 2023.

25 An illustrious example is the ambitious nine-volume Harvard book series, Religions of the World and Ecology (emerging from the Centre for the Study of World Religions at Harvard Divinity School). Here African Traditional Religion is represented in the anthology entitled Indigenous Traditions and Ecology (2001) in one chapter (out of 26 chapters) that features the story of "the sacred egg" in West Africa. Suffice to say, the turn to indigeneity and indigenous knowledges was not exactly booming in early 2000s' scholarship on religion and ecology. See, John Grim (ed.), Indigenous Traditions and Ecology: The Interbeing of Cosmology and Community (Cambridge, Mass.: Distributed by the Harvard Press for the Centre for the Study of World Religions, 2001).

26 See, Karen Warren, Ecological Ecofeminism (New York: Routledge, 1994) and Hoel and Nogueira-Godsey, "Transforming Feminisms: Religion, Women and Ecology," 5-16.

27 For an excellent and sophisticated engagement with the concept of dualism, see Val Plumwood, Feminism and the Mastery of Nature (London: Routledge, 1993), particularly chapter two, "Dualism: the Logic of Colonisation", 41-68.

28 See Plumwood, Feminism and the Mastery of Nature, 41-68; and Hoel and Nogueira-Godsey, "Transforming Feminisms: Religion, Women and Ecology," 5-16.

29 See Plumwood, Feminism and the Mastery of Nature, 43, for a detailed list of "contrasting pairs".

30 Carolyn Merchant, Earthcare: Women and the Environment (London: Routledge, 1996).

31 See, Merchant, Earthcare, xvi.

32 Merchant, Earthcare, xvi.

33 Jack Halberstam's book Wild Things: The Disorder of Desire, invites us to journey through an alternative history of sexuality, a history where wildness has been inscribed onto queer bodies. Although, perhaps, centrally presenting an original critique of the modern liberal subject, Halberstam innovatively demonstrates the various ways in which wildness as knowing and being destabilizes boundedness and predictability. Thinking with Halberstam's 'wild thinking' as it pertains to imperial, colonial and Christian imaginings of a new Garden, offers us alternative and transgressive insights on the wild and wilderness. See, Jack Halberstam, Wild Things: The Disorder of Desire (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2020).

34 See, Heather Eaton, Introducing Ecofeminist Theologies (New York: T&T Clark International, 2005) and Ivone Gebara, Longing for Running Water: Ecofeminism and Liberation (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1999).

35 Elisabeth Grosz, "The Future of Feminist Theory: Dreams for New Knowledges," in H. Gunkel, C. Nigianni, and F. Soderback (eds), Undutiful Daughters: New Directions in Feminist Thought and Practice (New York: Palgrave, Macmillan, 2012), 13-22 (quotation pp.13-14).

36 Donna J. Haraway, Staying with the Trouble, 12.

37 For excellent scholarship on feminist posthumanism, see Rosi Braidotti, The Posthuman (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2013) and Stacey Alaimo, Exposed: Environmental Politics and Pleasures in Posthuman Times (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016); for hydrofeminist perspectives and connected scholarly works that innovatively thinks with water and oceans for environmental justice, see, Astrida Neimanis, Bodies of Water: Posthuman Feminist Phenomenology (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016) and "Hydrofeminism: Or, on Becoming a Body of Water," in H. Gunkel, C. Nigianni, and F. Soderback (eds.), Undutiful Daughters: New Directions in Feminist Thought and Practice (New York: Palgrave, Macmillan, 2012), 85-99; for emerging scholarship that thinks with oceans in relation to higher education in South Africa, see, Nike Romano, Vivienne Bozalek and Tamara Shefer (eds.), CriSTaL (Critical Studies in Teaching and Learning) Special Issue: Thinking with Ocean/s for Reconceptualising Scholarship in Higher Education, 11, 2 (2023). DOI:10.14426/cristal.v11iSI2.722.

38 See Anna Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015).

39 Neimanis, "Hydrofeminism," 85, and Mark McMenamin and Dianna McMenamin, Hypersea (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994), 15, quoted in Neimanis, "Hydrofeminism", 86.

40 Donna Haraway, "A Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology and Socialist Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century," Socialist Review, 80 (1985): 65-108.

41 Haraway, "A Manifesto for Cyborgs".

42 The field of African Traditional Religion and ecology engaged earlier in this article contains rich theorizations of kinship in connection with environmental concerns.