Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of Vocational, Adult and Continuing Education and Training

On-line version ISSN 2663-3647

Print version ISSN 2663-3639

JOVACET vol.6 n.1 Cape Town 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.14426/jovacet.v6i1.317

ARTICLES

Pathways of Early Childhood Development practitioners into higher education: A capabilities approach

Kaylianne Aploon-ZokufaI; Seamus NeedhamII

ILecturer and PhD candidate in the Institute for Post School Studies (IPSS), Faculty of Education, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa ORCID link http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2725-6893; (kaploonzokufa@uwc.ac.za)

IIActing Director of the Institute for Post-School Studies (IPSS), Faculty of Education, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa ORCID link http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8353-9148; (sneedham@uwc.ac.za)

ABSTRACT

The creation of professional learning pathways in the field of early childhood development (ECD) is currently a key policy priority in South Africa, especially as research has indicated the critical need that exists for investment in ECD practitioners to resolve previous educational inequalities and poor throughput rates in formal schooling. The option of recognition of prior learning (RPL) often provides the only route into post-school studies for educators in this historically marginalised sector to enable them to pursue formal qualifications. The barriers faced by mature females, who constitute a large proportion of ECD practitioners, include mismatches between occupational and discipline-based qualifications and a lack of understanding of the non-traditional routes into higher education. This article reports on an investigation into the experiences of a sample of mature women who attempted to access higher education with non-traditional qualifications. Using the lens of capabilities theory, we demonstrate the significant efforts made by these ECD practitioners to achieve their goals of personal and economic freedom by accessing further training and higher education through RPL. The article concludes with a discussion on implementing effective RPL for transitions in post-school education and training.

Keywords: Recognition of prior learning (RPL); articulation; mature women students; early childhood development; post-school studies; capabilities theory

Introduction

Poverty among women has been on the rise globally (Moghadam, 1998; Kongolo, 2009; Tao, 2019). Women's access to higher education, particularly in Africa, is crucial to their upward mobility, and, for many, it provides a route out of poverty (Groener, 2019). Inequalities in access and participation feminise poverty and further assign to women much of the menial work in society, as largely unpaid or underpaid labour (Robertson, 1998). Globally, male privilege is also constantly shifting in form and being reinvented under new circumstances (Robertson, 1998). For poor black women, accessing higher education is crucial. This kind of access reinforces women's stronghold against poverty and provides empowerment in marginalised communities.

South African statistics show a close relation between gender, race and class:

[B]lack working-class women's class, race and gender-based access to resources and opportunities ... perpetuate inequality and poverty as a whole, while simultaneously decreasing women's socio-economic status (Kehler, 2001:44).

These three concepts - race, class and gender - are relational concepts that define the political, social and economic functions in society. Women's poverty will continue to increase so long as their participation in the workforce continues to decrease. Poverty is therefore feminised and perpetuated among South African women due to the inaccessibility of socio-economic rights, inclusive of access to higher education, which are supposedly enshrined in the Constitution (Kehler, 2001). Accessing higher education for women is consequently an essential resource to circumvent poverty.

This article provides a brief context of the challenges faced by women in accessing higher education, including challenges with recognition of prior learning (RPL). It then describes South Africa's post-school education and training (PSET) system, which incorporates adult education institutions, technical and vocational education and training (TVET) colleges, and universities. The attempts of mature women to access higher education with non-traditional qualifications is then analysed through a capabilities approach as espoused by Sen (1999) and this analysis reveals the importance of individual agency in obtaining economic and social freedoms in a difficult institutional environment. We conclude with a discussion on further research and the effective implementation of RPL in higher education.

Mature women's access to, and recognition of, prior learning

The limited research on access to higher education for mature women, and the ways in which RPL facilitates it, is a global phenomenon (Cooper & Harris, 2013). However, recent research in South Africa shows funding to be a serious impediment to mature women's access to, and participation in, higher education (Aploon-Zokufa, 2022). Elsewhere, mature women's access has been described as limited, associated as it is with risk and barriers to access, participation and success in both further education and training and higher education (Reay, 2003; Zart, 2019). The facilitation of access for mature women through RPL has also not been well documented. Research does, however, show that such access is important for skills development and crucial to social justice because of its potential to widen the access and participation of marginalised people such as mature women (Cooper & Harris, 2013).

Mature women's access and learning pathways

According to research, mature women have certain characteristics that make them a unique group in relation to their access, participation and success in higher education (Wyatt, 2011; Lee, 2014; Santos, Bagos, Baptista, Ambrósio, Fonseca & Quintas, 2016). Among these characteristics is the idea that they have dropped out of school early in their lives, re-entered schooling informally in their communities and then moved on to higher education in their later years (Reay, 2003; Kaldi & Griffiths, 2013; Wright, 2013). They mainly lack traditional school qualifications with acceptable pass marks for entrance to universities, which makes their learning pathways more challenging than for those who enter higher education earlier in their lives. The age at which they aim to access higher education deeply affects their participation and success of entry (Santos et al., 2016). Learning informally through communities of practice (Wenger, 1998) is an important characteristic of mature women students because informal learning plays a crucial role in their learning pathway (McGivney, 2003). The flexibility associated with informal learning is what attracts mature women students. However, numerous studies show that mature women students face barriers to their formal learning and their progression (Burton, Lloyd & Griffiths, 2011; Kaldi & Griffiths, 2013). Among these barriers are family and financial responsibilities as well as a lack of financial resources and time to study and to attend classes (Bowl, 2001). Learning informally is therefore one way of ensuring that their high level of motivation to learn (Kaldi & Griffiths, 2013) is achieved and provides hope for access to formal learning.

Mature women's access and articulation

Some of the challenges associated with limited access to higher education in South Africa can be attributed to poor articulation between TVET colleges and higher education. Minister Blade Nzimande (as quoted in Papier, Sheppard, Needham & Cloete, 2016:44) indicated that

a well-articulated system is one in which there are linkages between its different parts; there should be no dead ends. If a student completes a course at one institution and has gained certain knowledge, this must be recognized by other institutions if the knowledge gained is sufficient to allow epistemological access to programmes that they want to enter.

The South African education system is not well articulated. This view is supported by Papier et al. (2016), who argue that there is minimal articulation between TVET colleges and universities, resulting in TVET graduates struggling to access university.

They argue further that, for TVET to be seen as a first choice for students, articulation needs to be effective both at the systemic level and at the level of the institution. 'Systemic articulation' refers to the joining up of qualifications and all the other elements that are aligned to and support learning pathways. 'Specific articulation' refers to the informal and formal agreements between different institutions within the education system (SAQA, 2017). The South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA) policy also iterates that

articulation exists through the addressing of boundary-making practices and the support of boundary-crossing practices as individuals encounter 'boundary zones' between the different elements of learning pathways. This support includes reducing the gap between learning pathways-related policy development and implementation; strengthening specific pathways and enhancing the opportunities to access and progress along these pathways ... (SAQA, 2017:15).

Currently, colleges and higher education institutions do not provide students with the access and mobility which many need to progress academically. Students face obstacles in moving both vertically and horizontally (Cosser, 2011; Papier et al., 2016). In particular, the lack of articulation in the South African education system is a fundamental factor that prevents mature women students from accessing further and higher education. The purpose of our study is to provide a description of the experiences of mature women who accessed higher education through RPL so that we can assess how they navigated the career and learning pathways in a difficult higher education system in order to realise their own social opportunities.

South African context and background to recognition of prior learning

Evidence of student access to higher education through an RPL route is largely unknown and limited (Cooper & Harris, 2013). Official public statistics (DHET, 2022) also do not include access through RPL as a statistical category. The Council on Higher Education (CHE), which is responsible for university qualifications, has noted that university records conflate students who access higher education through RPL with other students entering with non-traditional schooling qualifications, such as mature-age exemption and foreign qualifications (Papier & Needham, 2021). There is, therefore, no formal statistical evidence that RPL is used as a mechanism to enter higher education.

The manner in which RPL is managed varies across higher education institutions: as is shown in our analysis, some universities have established RPL offices on campus and their records are publicly available. Other universities manage the RPL process virtually (Bolton, 2022). Targets of 10% enrolment of students in undergraduate degrees through RPL processes have also been set. In 2021, a Western Cape research university noted that 27 candidates had applied to study for undergraduate degrees in education, and that, of these, 20 candidates had been successful and had enrolled at the university (Rambharose, 2022).

The current full-time enrolment in the first year of an undergraduate education degree at this university in 2021 was 154. This shows that the target of 10% RPL candidates is possible, although there is no evidence from this university or other higher education institutions that the target of 10% undergraduate enrolment through RPL has been met in other undergraduate programmes. Access through RPL into undergraduate degrees remains a marginal form of mainstream access to these programmes, and to higher certificates and diplomas generally. The following section provides some insight into the candidates applying to enter university undergraduate degree programmes through RPL.

Policies in post-school education and training: Access, mobility and progression

South Africa's first democratic Constitution promises that everyone has the right to further education, which the state, through reasonable measures, must make progressively available and accessible (RSA, 1996:12). A raft of education and training policies was subsequently introduced to realise these aims. The articulation of qualifications in post-apartheid South Africa has received considerable policy attention. For instance, the SAQA Act 57 of 1995 was one of the first pieces of legislation introduced after the dawn of the new democratic dispensation in South Africa in 1994. This led to the introduction of an eight-level National Qualifications Framework (NQF) that encompassed all qualifications in South Africa and a subsequent ten-level framework in 2008. Articulation was one of the key principles addressed in the NQF, its aim being to

facilitate access to, and mobility and progression within education, training and career paths for all South Africans to accelerate the redress of past unfair discrimination in education, training and employment opportunities (SAQA Act 57 of 1995).

Successive policies were introduced, culminating in the 2017 formal Articulation Policy for the Post-School Education and Training (PSET) system of South Africa.

Similar policies have been developed for RPL as an integral part of articulation between PSET institutions. The 2019 SAQA National Policy and Criteria for the Implementation of RPL notes that 'RPL can include any type of prior learning (non-formal, informal and formal) across all ten levels of the NQF' (SAQA, 2019:8). It further notes the following:

There are two main forms of RPL that reflect the different purposes and processes within which RPL takes place: a. RPL for access: To provide an alternative access route into a programme of learning, professional designation, employment and career progression; and b. RPL for credit: To provide for the awarding of credits for, or towards, a qualification or part-qualification registered on the NQF (SAQA, 2019:9).

Whereas these appear to be enabling policies that allow the movement of learners to higher education career and learning pathways, a High Level Panel Report produced in 2017 is critical of South Africa's policy formulation, as noted below:

The sheer number of bodies that have some role in relation to quality, for example, has reached unsustainable proportions (they include, inter alia, the South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA); Council on Higher Education/Higher Education Quality Committee (CHE/HEQC); Umalusi; the Quality Council for Trades and Occupations (QCTO); 21 Sector Education and Training Authorities (SETAs); 93 professional bodies; National Artisan Moderation Body (NAMB); South African Institute for Vocational Training and Continuing Education and Training (SAIVCET); and so forth (RSA, 2017:550).

Each of the bodies mentioned above is a statutory organisation with separate quality assurance mandates, including RPL. Whereas SAQA oversees the implementation of South Africas NQF, it has limited authority to ensure coherence in and between these quality assurance bodies. More recently, there has been a strong focus on attempting to implement articulation such as the Unfurling Post-School Education and Training (UPSET) project underway at the Durban University of Technology (DUT) and a continuing focus on policy formulation such as Flexible Learning Pathways (Bolton & Blom, 2020). These are emerging initiatives and their impact is still to be assessed. A critical factor affecting articulation into higher education by learners with occupational qualifications is that universities use secondary school exit qualifications as the sole criteria when granting access to undergraduate programmes, while occupational programmes are not recognised. This applies even in cases where occupational programmes are accredited as being on the same level as, or on a higher NQF level than, the secondary school exit qualifications.

Having outlined the central policies affecting articulation, including RPL in South Africa, the following section attempts to provide evidence of any policy implementation of access to higher education through RPL.

A capabilities approach to assessing mature women's access to, and learning pathways into, higher education

The idea of educating for sustainable development draws on a human capabilities approach informed by theorists such as Sen (1999), which approach prioritises human development above economic development. While sustainable development has also been a response to the growing strength of the environmental criticism of conflating development with growth, Sen's approach to human freedom has had considerable impact. Sen's theoretical approach assumed prominence following the criticism of human capital approaches to TVET promoted by theorists such as Psacharopolous (1985), whose research was used by the World Bank to justify an assertion that primary education offered better economic rates of return than TVET in the 1980s. Nussbaum & Sen (1993:30) define the term capabilities' as a representation of the 'alternative combinations of things a person is able to do or be - the various "functionings" they can achieve'. In describing freedom as the primary focus of human development, Sen identifies five main freedoms that require both individual and institutional efforts for their achievement:

• political freedoms;

• economic facilities;

• social opportunities;

• transparency guarantees; and

• protective security.

Sen views these freedoms as interconnected: social opportunities such as health and education facilities can contribute to economic participation, which, in turn, increases wealth and contributes to further resources for social upliftment (Sen, 1999). Sen asserts that this perspective of freedom reinforces the role of individual human agency in achieving freedoms for human development, although institutional contributions are also acknowledged.

Nussbaum and Sen (1993) disagree on the issue of developing a single list of capabilities that would describe essential human freedoms. These authors argue that a single list would have to be over-specified to include all the contexts of human interaction (Nussbaum & Sen, 1993:47). Sen readily concedes, in response to criticism by Cohen (1989:50), that his capabilities approach is not a complete theory of valuation in its own right but that it is a general approach to human development that can be combined with other substantive theoretical approaches, and that it advocates the 'cogency of a particular space for the evaluation of individual opportunities and successes'.

Robeyns (2005:94) states that Sen's capabilities approach is 'not a theory that can explain poverty, inequality or well-being: instead it provides a tool and a framework within which to conceptualise and evaluate this phenomena (sic)' (italics in original, 2005). Whereas most academic use of Sen's capabilities approach has focused on individual human agency to achieve capabilities and associated functionings, Sen (1999:142) refers to the importance of institutions in stating that individual 'opportunities and prospects depend crucially on what institutions exist and how they function'. Otto and Ziegler (2006:275) concur with this view and note that 'educational and welfare institutions as well as other policies should be evaluated according to their impact on people's present and future capabilities'. Robeyns (2005:110) similarly asserts that the conceptual framework of the capabilities approach includes institutions and individual human agency, and posits that

for political and social purposes it is crucially important to know the social determinants of the relevant capabilities, as only those determinants (including social structures and institutions) can be changed.

The capabilities approach has been used to evaluate educational interventions and conditions for learners to achieve educational success (Hoffmann, 2005; Walker & Unterhalter 2007; Wilson-Strydom, 2011; Powell, 2014; Powell & McGrath, 2014).

A critical challenge has been to identify lists of capability and associated functioning that can be used to evaluate whether learners are capable of obtaining educational freedoms in their chosen course of study. Hoffmann (2005) drew on the Dakar Framework for Action (UNESCO, 2000) and the Delors Commission (1996) that identified four pillars of learning aligned to a life-skills education and capabilities approach:

• learning to know (informed action);

• learning to be (individual agency);

• learning to live together (interpersonal skills); and

• learning to do (practical application).

In a South African context, Wilson-Strydom (2011) draws on Walker's (2006) approach that identifies appropriate contexts in which to develop illustrative capabilities for education. Wilson-Strydom (2011:416) argues that a singular focus on educational outcomes at universities can lead to

new forms of injustice because it is assumed that once equal resources are provided (such as a place at university or financial support) all students are equally able to convert these resources to capabilities and functionings.

From an educational perspective, capabilities theory has been used to identify a range of capabilities that position learners and institutions in ways that supersede the traditional human capital approaches of education for employment. Powell (2014:205-206) developed a capabilities list as entitlements that learners can expect from TVET colleges. These include: economic opportunities that matter; active citizenship; confidence and personal empowerment; recognition and respect; and to upgrade skills and qualifications throughout the course of life. These are expanded capabilities that transcend traditional approaches of education and training for employment in the formal economy. Having outlined the theoretical approach for this article, we now examine case studies of older women's experience of the RPL process to further their higher education studies in pursuit of economic and social upliftment.

Context and methodology of the study

The central research question for this study was: What are the barriers to accessing higher education for mature women early childhood development (ECD) practitioners through the alternative route of RPL?

Our study focuses on the learning pathways of mature women who are ECD practitioners in the Western Cape. Mature women ECD practitioners are defined as 20- to 60-year-old women working as practitioners in the early years of education, that is, those before the Foundation Phase of primary school. In addition, they actively seek access to undergraduate studies at institutions of higher education, specifically the Bachelor of Education (BEd) undergraduate degree. The qualitative research design (Giddings & Grant, 2009) and the interpretivist framework (Bryman, 2016) of the broader study incorporated three research methods: a research survey, life history interviews, and one focus-group interview. Data from the research survey, which extended across two different institutions of higher education in South Africa, provided the pool from which the participants for the life history interviews were selected. The key criteria for the selection of participants for the life history interviews were that the women had to have worked in ECD centres previously and completed ECD Level 1, ECD Level 4 or ECD Level 5 programmes atTVET colleges. They also had to reside in the Western Cape and had to have applied to a university to register for the BEd programme for a minimum of five consecutive years.

The life history interviews were conducted with 11 mature women ECD practitioners during the COVID-19 lockdown period using the Google Meet application. The interviews were approximately two hours long and were semi-structured. From the life histories, the participants' learning pathways from birth to primary school, from primary school to high school, and from post-high school to the time of the interview were traced and compiled. Our specific focus for this study was on the learning pathways which could show us the RPL route for accessing the BEd programme on the post-school learning pathway of the participants. Therefore, we extracted the data regarding the RPL access route for mature women. In accordance with ethics requirements, the identities of the women have been kept anonymous and pseudonyms have been used to ensure confidentiality. In our analysis, the higher education institutions at which the women applied for access are referred to as Institution 1, 2 and 3. We do this to anonymise the individual and specific experiences the participants had with the processes, staff and policies at these institutions.

Data analysis

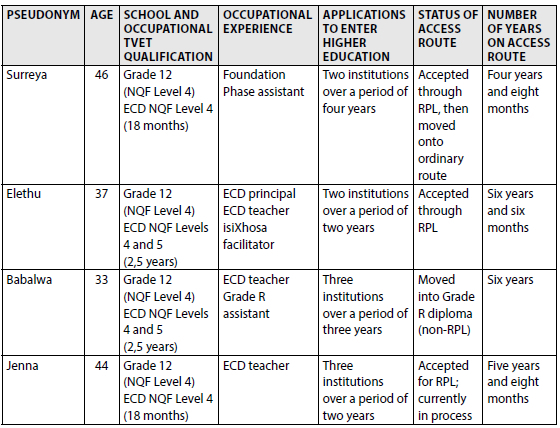

Using narrative analysis (Richmond, 2002), we drew up detailed descriptions of the participants' post-school learning pathways. These pathways included the RPL route into the BEd. All 11 ECD practitioners lived and worked in lower-income communities and identified themselves as Black or Coloured, with either Afrikaans and isiXhosa as their mother tongue. The use of these racial identities is included, as South Africa still uses these categories to promote affirmative action and empowerment as a form of redress to overcome discrimination as a result of colonialism and apartheid. They were all women who had commenced their journey in ECD as volunteers and, after obtaining some formal occupational qualification in the field, occupied roles such as teacher assistant, principal, ECD practitioner, and Foundation Phase assistant at primary schools. Although they had been working in this industry for a few years, they had also had other kinds of previous work experience, including administration, debt collecting, and working as cashiers in the retail industry. The only formal qualifications these women had acquired after school were those from TVET colleges. The occupational ECD programmes at these TVET colleges are 18 months in length. In addition to these qualifications, all of the women participated in informal training opportunities at their centres and in their communities. All 11 participants in the life history interviews had applied for access into the BEd programme at three institutions of higher education but only four had gained such access through RPL. One gained access into university. However, it was not into this programme and not through RPL, even though she had applied to do so. The remaining participants had not accessed higher education. The data suggest that a limited knowledge of RPL is related to their status of a lack of access to a higher education institution. Below are the descriptions of the four mature women who had been able to access the BEd through RPL.

The learning pathways of the four ECD practitioners described above reveal their participation and success in ECD occupational programmes based at TVET colleges. The pathways also provide clarity with regard to the qualifications these women have obtained and their accompanying occupational experience. The women had applied to different higher education institutions for access over a period of between three and six years and, as mentioned before, had been able to gain access only through RPL. Furthermore, the data reveal that the process of gaining access to higher education for the ECD learning pathway is long and convoluted, and filled with barriers and bridges. For those women who have gained access via RPL, it has provided some light on their journey towards higher education access.

We now continue with the individual descriptions of the ECD learning pathways in relation to RPL for our participants.

Surrey a (46)

After completing her schooling and ECD Level 4, Surreya applied for access into the BEd undergraduate degree at two different institutions over a period of four years. She received no feedback regarding her applications and, upon enquiring, was directed to the Adult Learning Centre and the RPL Unit at Institution 1. She first learnt about RPL through a friend. She explains:

Then somebody, one of the teachers ... at Institution 2 ... [who] was doing a diploma in Grade R ... basically said, 'You know, because of your age, why don't you try to get through the RPL?'

After being redirected to this unit by faculty staff, Surreya applied and participated in this programme. Midway through the programme, she describes her experience:

When I got [to the unit] I still had an interview ... . And then after the interview they realised that I actually ... didn't fail any of my [school] subjects, so I passed with exemption. [Then they said,] 'You can actually just go apply as normal, you don't have to apply through the RPL.'

Elethu (37)

Elethu received information about RPL from a friend. She explained that her friend had phoned her and had asked: 'Have you looked at your WhatsApp? I sent you something. Please look at it and then try to follow the link; there is a link there.' Said Elethu, And then, when I was looking at it, it was ... the RPL programme.' She had applied at two institutions but was told that she did not have sufficient points to qualify for access to university undergraduate qualifications and that she did not meet the requirements. However, she followed the link sent via WhatsApp, applied and was accepted into the RPL programme at Institution 1. She shared her positive experience of participating in this programme:

[T]hat was a very nice experience because it was actually ... [my] first time ... [at] the university. ... [0]n Saturday[s] there [were] no other students ... , only the RPL people (faculty staff within a university RPL unit) [who] helped us. [T]hey taught us how to write the essays and everything, preparing us for the first year. But they said, 'Not all of you will be accepted at the university.' You need to work on your portfolio of evidence so that they will [accept] it; ... we had to work hard, [v]ery hard. [A]nd then in November ... I got accepted [by] the Education Faculty.

Babalwa (33)

Babalwa's learning pathway shows that she gained access into higher education but not into the BEd programme as she desired. She continued:

I went and looked for a school there [at] Institution 1.1 applied there, and I think I applied twice but . was rejected. I think they (the Faculty of Education) [said] I should go to ... RPL where there is education for old women. I think I applied twice ... [but] was rejected. ... I applied at ... and [at] ... , so I applied [to] two faculties. Luckily for me, I was accepted [at] [Institution 2], ... so now I'm doing this Grade R Diploma for Foundation Level.

Jenna (44)

Jenna, who had applied at three different universities, two years in a row, also heard about RPL from a friend:

I was contacted by a friend and she told me about the RPL programme. I asked her to contact the RPL office for me, and she contacted the RPL office and then sent me all the information . I needed to complete. She copied me into the emails and so I could see that they took very long to respond. We actually had to email a few times ... to get them to respond. (Jenna's friend referred her to the RPL unit at Institution 3).

For my application, I [then] had to send all my details, work history, certificates, motivational letters with a payment of R330.

My application was successful, but the lady took very long to respond. Then I had to complete a portfolio for access to an undergraduate qualification. I had to answer a contextual questionnaire, write a motivation letter [, give ... ] a career timeline and [outline] my teaching philosophy. [I a]lso had to observe two experienced teachers and write about their lessons and the obstacles they faced. I had to prepare three lessons [for] two different subjects ... [from] the grade which I am currently teaching. ... I [then] had to complete a reflective assessment [and] write about my extramural experience. My mentor and the principal had to write verification letters about me. With the portfolio I also had to make a payment of R2 420.

Findings

The data from the life history interviews show that access to higher education for the group of mature women occurred only through RPL, with the exception of one candidate whose RPL process showed that she had acceptable school grades to access an undergraduate degree. This means that, in the post-school education system in South Africa, RPL provides a rare access route to undergraduate degrees for mature women ECD practitioners. Despite completing their schooling, participating in ECD programmes offered at TVET colleges, and having years of acquired practical experience, these attributes were not recognised by the universities to which the women practitioners applied for access. Only those women who knew about RPL, and applied using their previous experience and post-school qualifications, were able to access undergraduate studies. Knowledge regarding this access route is therefore key for mature women. However, all of the participants who were able to access RPL learnt about this programme through word-of-mouth from other women in their communities or circles of influence. This indicates that information regarding RPL is not disseminated at grassroots levels in communities where those most marginalised from accessing higher education reside, including mature women ECD practitioners. This is a key barrier to accessing higher education through RPL.

In addition to finding out about RPL from a friend, Surreya was also directed to RPL via university faculty staff after she enquired about the outcome of her application for undergraduate studies. This participant applied to two different institutions over a three-year period but received no feedback from the universities to which she applied. This was the case for all the participants in this study: they applied at different institutions for the same programme over a two- to three-year period. None of them received feedback regarding their application. After applying for RPL access and participating in the programme, Surreya was advised by RPL staff that she could access the BEd undergraduate degree on the basis of her school-leaving certificate alone. Perhaps she was directed to RPL due to her age or her vocational qualifications and work experience. However, she did not need RPL access and she was accepted into the BEd programme at Institution 1 after applying again the following year. In this instance, limited feedback from universities regarding the applications of mature women further hinders their access and participation.

Our data show that institutional differences in providing RPL access to mature women ECD practitioners create barriers to access. At Institution 1, Elethu participated in RPL through a classroom setting. This mature woman indicated that, in this setting, RPL participants were taught valuable skills such as essay writing. However, a barrier at this institution, mandated by the SAQA regulation, is that only 10% of RPL participants per year may be allowed entry to university. This means that, even though students may successfully participate and complete the RPL programme in a given year, they may still not gain access into university due to this SAQA regulation.

At Institution 2, Babalwa was accepted into university for the Grade R Diploma even though she had applied for access to the BEd undergraduate degree. At this institution, despite official policy, RPL was not offered as an access route and, as has been mentioned before, without RPL mature women struggle to gain access into the BEd programme. Babalwa, who had participated in ECD Level 4 and ECD Level 5 for a period of 36 months after her secondary school qualifications, is now participating in a Grade R Diploma programme for another four years. She then faces more years of study if she is successful in entering the BEd undergraduate degree based on her diploma results. At an institutional level, not providing RPL as an access route for mature women through which their previous ECD qualifications can be recognised poses a barrier to their access and participation, in that it lengthens the time they spend trying to access an undergraduate degree. This also results in the need for more funding, as both the Grade R Diploma and the BEd undergraduate degree are full-time programmes at Institution 2 and are funded through the National Student Financial Aid Scheme (NSFAS). However, NSFAS policies provide funding only for one higher education qualification per student.

Jenna also received the information regarding RPL from a friend. Quite differently from Elethu, who participated in RPL in a classroom setting, Jenna had the option of participating in the programme by completing a portfolio on her own with the help of a mentor. At the time of the interview, Jenna was a Grade R teacher with an ECD Level 5 qualification. Her position in a formal primary school, and having other teachers and staff at the school as mentors, may have provided her with a good support structure for creating lesson plans. However, not all mature women have this support, and completing the RPL portfolio for access without institutional support, such as in the case of the requirements at Institution 3, poses a barrier to marginalised ECD practitioners who work at informal centres in their communities and have limited resources at their disposal.

Discussion

Gaining access to higher education for mature women ECD practitioners should be a primary concern in the South African PSET system, since ECD is a key policy priority for the DHET and research shows the importance of education in the early childhood years before formal schooling commences (Feza, 2012, 2018) in order to overcome educational inequalities and poor throughput rates in formal schooling. RPL provides an articulation route for ECD practitioners into the BEd (Foundation Phase) programme. However, there are barriers to accessing higher education through RPL, which the present study shows is a rare access route to higher education for the women in this context. As noted, even when mature women can access undergraduate studies without the support of RPL, they are often redirected to this programme for access due to a lack of recognition of their post-school studies. Key barriers to RPL for the participants in the study include not receiving information regarding this access route; higher education institutions not providing access through RPL for mature women with occupational qualifications; and the requirement by some institutions to have RPL participants complete a portfolio as a prerequisite for access - in isolation of any institutional support. Our study has described the impact of these barriers on the lived experiences of mature women who aim to graduate as Foundation Phase teachers following their existing ECD practitioner route and TVET college qualifications after they completed high school.

All of the women who eventually gained access to a BEd undergraduate degree took many years to do so, which involved both costs and an inordinate amount of time to achieve this goal. This was the same for the women who are still attempting to gain access. From a human capabilities perspective, their personal routes to achieving access to university showed that their efforts to formalise their qualifications were not primarily based on obtaining qualifications to enter employment. Rather, this reflected the culmination of efforts to achieve their life goals and become qualified and recognised professional teachers. Issues such as dignity and respect in their own families and communities were important drivers, and also the need to make a difference in the communities in which they lived and worked. Each of these women aspired to achieve their own personal freedoms and were determined to face and overcome all barriers in order to empower themselves, their families and their communities.

Conclusion

This article has focused on mature women's attempts to enter undergraduate degrees in education through an RPL process. These women have spent years after their formal schooling trying to obtain a range of occupational qualifications that allowed them to work in lower-level positions in ECD centres. Their passion for, and commitment to, education led them to pursue higher education opportunities so as to improve their educational status and become fully fledged early childhood educators in their communities. From a human capital perspective, their pursuit of higher education shows a poor rate of economic return, especially considering that these mature women have spent more than three years trying to enter RPL programmes that would lead to their acceptance into undergraduate degrees in the field of education. However, an analysis of their career and learning pathways from a capabilities perspective shows their individual determination to succeed and to achieve both economic and social freedoms despite having to navigate poorly articulated education and training pathways. A final hurdle they faced was to access university education, which proved difficult without sufficient mainstream schooling qualifications and due to the lack of recognition of their occupational qualifications. For these women, the RPL access route for entering higher education was their only way into a university education. Using capabilities as a lens to view these mature women's education and training pathways not only illuminated their individual attempts to achieve their own freedoms, but also sheds light on the institutional and systemic blockages that continue to impede mature women's access to higher education.

REFERENCES

Aploon-Zokufa, K. 2022. Funding as a crisis for mature women students: Agency, barriers and widening participation. In Z Groener & S Land (Eds). Adult education and learning access: Hope in times of crisis in South Africa. University of the Western Cape, CapeTown: Department of Higher Education and Training.

Bolton, H. 2022. Flexible learning pathways and RPL in South Africa: National snapshot. Implementation Assessment Articulation of Recognition of Prior Learning Conference. University of the Western Cape. Republic of South Africa, 31 March 2022.

Bolton, H & Blom, R. 2020. Report for the IIEP-UNESCO Research 'SDG4': Planning for flexible earning pathways in higher education. Available at: http://www.saqa.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Flexible-Learning-Pathways-in-SA-2020-12. [Accessed 5 April 2023].

Bowl, M. 2001. Experiencing the barriers: Non-traditional students entering higher education. Research Papers in Education, 16(2):141-160. Available at: <http://doi.org/10.1080/02671520110037410> [ Links ].

Bryman, A. 2016. Social research methods (5 ed). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Burton, K, Lloyd, MG & Griffiths, C. 2011. Barriers to learning for mature students studying HE in an FE college. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 35(1):25-36. Available at: <http://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2010.540231> [ Links ].

Cooper, L & Harris, J. 2013. Recognition of prior learning: Exploring the 'knowledge question'. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 32(4):447-463. Available at: <http://doi.org./10.1080/02601370.2013.778072> [ Links ].

Cosser, M. 2011. Pathways through the education and training system: Do we need a new model? Perspectives in Education, 29(2):70-79. [ Links ]

Delors, J, AÍ Mufti, I, Amagi, I, Carneiro, R, Chung, F, Geremek, B, Gorham, W, Kornhauser, A, Manley M, Padrón Quero, M, Savane, MA, Singh, K, Stavenhagen, R, Myong Won Suhr &, Zhou, N. 1996. Learning: The treasure within; report to UNESCO of the International Commission on Education for the Twenty-first Century. UNESCO. Available at: <http://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark/48223/pf0000102734>. [Accessed 20 April 2023]

Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET). 2022. Statistics on Post-School Education and Training in South Africa 2020. ISBN: 978-177018-873-0.

Feza, N. 2012. Can we afford to wait any longer? Pre-school children are ready to learn mathematics. South African Journal of Childhood Education, 2(2):58-73. [ Links ]

Feza, N. 2018. Teachers' journeys: A case of teachers of learners aged five to six. Africa Education Review, 15(1):72-84. Available at: <http://doi.org/10.1080/18l46627.2016.1241673> [ Links ].

Giddings, LS & Grant, BM. 2009. From rigour to trustworthiness: Validating mixed methods. In S Andrews & EJ Halcomb (Eds). Mixed methods research for nursing and the health sciences. Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. [ Links ]

Groener, Z. 2019. Access and barriers to post-school education and success for disadvantaged black adults in South Africa, journal of Vocational, Adult and Continuing Education and Training, 2(1):54-73. Available at: <http://jovacet.ac.za/index.php?journal=JOVACET&page=article&op=view&path[]=32>. [Accessed 22 February 2023] [ Links ]

Hoffmann, M. 2005. The capabilities approach and educational policies and strategies: Effective life skills education for sustainable development downloaded. Available at: <http://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/env/esd/EGC/Relevant%20materials/ADFCAPABILITIESARTICLE.doc>. [Accessed 22 April 2022]

Kaldi, S & Griffiths, V. 2013. Mature student experiences in teacher education: Widening participation in Greece and England. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 37(4):552-573. Available at <http://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2011.645468> [ Links ].

Kehler, J. 2001. Women and poverty: The South African experience, journal of International Womens Studies, 3(1):41-53. [ Links ]

Kongolo, M. 2009. Women in poverty: Experience from Limpopo Province, South Africa. An International Multi-Disciplinary Journal, 3(1):246-258. [ Links ]

Lee, S. 2014. Korean mature women students' various subjectivities in relation to their motivation for higher education: Generational differences amongst women. InternationalJournal of Lifelong Education, 33(6):791-810. Available at: <http://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.20l4.972997> [ Links ].

McGivney, V. 2003. Adult learning pathways: Through-routes or cul-de-sacs? National Institute of Adult Continuing Education. England and Wales. Available at: <http://www.voced.edu.au/content/ngv%3A12911>. [Accessed 10 April 2023]

Moghadam, VM. 1998. The feminization of poverty in international perspective. The Brown Journal of World Affairs, 5(2):225-250. [ Links ]

Nussbaum, M & Sen, A (Eds). 1993. The quality ofltfe. Oxford University Press. Published online: November 2003. Available at: http://www.doi.org/10.1093/0198287976.001.0001.

Otto, HU & Ziegler, H. 2006. Capabilities and education. SocialWork and Society, 4(2):1-19. [ Links ]

Papier, J & Needham, S. 2001. Commissioned CHE Research Paper, 2001. Not published.

Papier, J, Sheppard, C, Needham, S & Cloete, N. 2016. Provision, differentiation and pathways: A study of post-schooling in the Western Cape. Cape Town: Centre for Higher Education Trust. [ Links ]

Powell, L. 2014. Reimagining the purpose of vocational education and training. The perspectives of further education and training college students in South Africa. PhD thesis, University of Nottingham. Available at: <http://www.academia.edu/9430179/My_PhD_Thesis_Reimagining_the_Purpose_of_Vocational_Education_and_Training_The_perspectives_of_Further_Education_and_Training_College_students_in_South_Africa http://www.academia.edu/9430179/My_PhD_Thesis_Reimagining_the_Purpose_of_Vocational_Education_and_Training_The_perspectives_of_Further_Education_and_Training_College_students_in_South_Africa>. [Accessed 1 June 2023]. [ Links ]

Powell, L & McGrath, S. 2014. Exploring the value of the capability approach for vocational education and training evaluation: Reflections from South Africa. In MC Carbonnier & KK Gilles (Eds). Education, learning, training: Critical issues for development. International Development Policy Series No 5. Boston: Brill-Nijhoff. Available at: <http://www.researchgate.net/publication/271151340_Exploring_the_Value_of_the_Capability_Approach_for_Vocational_Education_and_Training_Evaluation_Reflections_from_South_Africa>. Accessed 5 March 2023] [ Links ]

Psacharopolous, G 1985. Returns to education: A further international update and implications. TheJournal of Human Resources, 2(4):586-604. Available at: <http://doi.org/10.2307/145686. Available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/145686>. [Accessed 15 April 2023] [ Links ]

Rambharose, R. 2022. Implementing RPL assessment and development through a multimodal pedagogical approach: An innovative model for student support. Implementation Assessment Articulation of Recognition of Prior Learning Conference. University of the Western Cape, 31 March 2022.

Reay, D. 2003. A risky business? Mature working-class women students and access to higher education. Gender and Education, 15(3):301-317. Available at: <http://doi.org/10.1080/09540250303860> [ Links ].

Republic of South Africa (RSA). 1996. The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996. Available at: <http://www.justice.gov.za/legislation/constitution/saconstitution-web-eng.pdf>. [Accessed 22 April 2022]

Republic of South Africa (RSA). 2017. Report of the High Level Panel on the Assessment of Key Legislation and the Acceleration of Fundamental Change. Available at: <http://www.parliament.gov.za/storage/app/media/Pages/2017/october/High_Level_Panel/HLP_Report/HLP_report.pdf>. [Accessed 22 April 2022]

Richmond, HJ. 2002. Learners' lives: A narrative analysis. The Qualitative Report, 7(3):1-14. [ Links ]

Robertson, CC. (1998). The feminization of poverty: Roots and branches. The Brown Journal of World Affairs, 5(2):195-202. [ Links ]

Robeyns, I. 2005. The capabilities approach: A theoretical survey. Journal of Human Development, 6(1):93-117. [ Links ]

Santos, L, Bagos, J, Baptista, AV, Ambrósio, S, Fonseca, H & Quintas, H. 2016. Academie success of mature students in higher education: A Portuguese case study. European Journal for Research on the Education and Learning of Adults, 1(17):57-73. Available at: <http://doi.org/10.3384/rela.2000-7426.rela9079> [ Links ].

Sen, A. 1999. Development as freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Sen, A. 2007. Capabilities approach and social justice in education. Available at: <http://doi.org.10.1057/97802306048101_1>.

South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA). 2017 and 2019. The South African National Qualifications Framework. Available at: <www.saqa.org.za>. [Accessed 8 November 2019]

Tao, S. 2019. Female teachers in Tanzania: An analysis of gender, poverty and constrained capabilities. Gender and Education, 31(7):903-919. Available at: <http://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2017.1336203> [ Links ].

UNESCO, (United Nations Educational, Social and Cultural Organization). 2000. The Dakar Framework for Action, Paris. ED 00/WS/27. Available: http://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/1681 Dakar%20Framework%20for%20Action.pdf [Accessed 1 June 2023].

Walker, M. 2006. Higher education pedagogies: A capabilities approach. New York: Open University Press. Available at: < http://philpapers.org/rec/WALHEP http://philpapers.org/rec/WALHEP >. [Accessed 20 March 2023] [ Links ]

Walker, M & Unterhalter, E. 2007. Amartya Sens capability approach and social justice in education. Palgrave, DOI: 10.1057/9780230604810. Available at: <http://www.researchgate.net/publication/258175758_Amartya_Sehs_Capability_Approach_and_Social_Justice_in_Education>. [Accessed 10 April 2023].

Wenger, E. 1998. Communities of proactive learning: Meaning and identity. Cambridge University Press. http://doi.org/10.1017/CB07980511803932.

Wilson-Strydom, M. 2011. University access for social justice: A capabilities perspective. South African Journal of Education, 31(3):407-718. DOI: 10.15700/saje.v31n3n544. Available at: <http://www.researchgate.net/publication/256462238_University_access_for_social_justice_A_capabilities_perspective>. [Accessed 5 March 2023] [ Links ]

Wright, HR. 2013. Choosing to compromise: Women studying childcare. Gender and Education, 25(2):206-219. Available at: <http://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2012.712095> [ Links ].

Wyatt, LG. 2011. Nontraditional student engagement: Increasing adult student success and retention. The Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 59(1):10-20. Available at: <http://doi.org/10.1080/07377363.2011.544977> [ Links ].

Zart, K. 2019. 'My kids come first - education second: Exploring the success of women undergraduate adult learners. Journal of Women and Gender in Higher Education, (12)2:245-260. Available at: <http://doi.org.10.1080/19407882.2019.1575244> [ Links ].