Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of Education (University of KwaZulu-Natal)

On-line version ISSN 2520-9868

Print version ISSN 0259-479X

Journal of Education n.92 Durban 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2520-9868/i92a05

ARTICLES

Mapping the form of continuing professional development in public-private partnership schools in the Western Cape

Lynne JohnsI; Yusuf SayedII

IDepartment of Educational Studies, Faculty of Education, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa. ljohns@uwc.ac.za; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1570-7765

IIFaculty of Education, Cambridge University, Cambridge, United Kingdom. yms24@cam.ac.uk; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2534-8420

ABSTRACT

Public-private partnership (PPP) schools in the Western Cape, South Africa, are known as collaboration schools. The management of these schools is outsourced to private entities known as school operating partners and these are, inter alia, also contracted to provide support to teachers through continuing professional development (CPD). The CPD activities are meant to up-skill teachers to improve teaching and learning and ultimately, advance learner performance. Although this is a valid principle, there is a need to evaluate the CPD received by collaboration schools. This paper profiles CPD provided in PPP schools to add to the understanding of this new form of schooling that which has taken hold in the Western Cape. Data were collected in the form of questionnaires and in-depth individual interviews with school operating partners, Western Cape Education Department officials, school leadership, teachers, and school governing body members. An analysis of the gathered information reveals that CPD received by teachers tends to focus narrowly on teaching and learning, and lacks the provision of a broad, expansive, and holistic notion of education. It also indicates the need for a better understanding of how such schools provide professional development support for teachers, and the effects on the provision of equitable and quality education for all.

Keywords: continuing professional development, public-private partnerships, collaboration schools

Introduction

Globally, and in South Africa, governance reform in recent times has seen the introduction of public-private partnerships (PPPs) in education where the public sector integrates the private sector for the provision of services and management. There have been multiple forms of private involvement in public schooling that include the provision of schooling, educational publishing, and production of standardised assessments (Winchip et al., 2019). This paper focuses on PPP schools in the South African context; they are known as collaboration schools in the Western Cape of South Africa. Given their newness in the field of education, much attention has been paid to the governance and management aspects, but far less to teachers and their professional development. This paper seeks to address this gap in knowledge.

Internationally, the specific provision of schooling by PPPs has taken the form of charter schools in the United States, and academies in the United Kingdom (Green & Connery, 2019). It was only in recent times that this phenomenon took root in Africa, namely, in Liberia and in South Africa (Gamedze, 2019; Romero et al., 2020).

In the Western Cape, collaboration schools are owned by the state, whilst the management of the school is outsourced to a non-profit school operating partner (SOP; de Kock et al., 2018). This new form of public schooling was introduced by the Western Cape Education Department (WCED) in 2016 as a pilot project. The provincial government of the Western Cape subsequently legislatively institutionalised the collaboration school model through the Western Cape Provincial School Education Amendment Act 4, 2018 (Western Cape Government, 2018). The legislation provided the overarching governing framework for these schools by clearly stating that collaboration schools are to be conceived as public schools.

The move towards PPP schools is often motivated by the argument that the public schooling system is failing. The arguments advanced for this failure are numerous, as described in literature (Languille, 2017; LaRocque & Sipahimalani-Rao, 2019), and include recurring themes such as teachers' lack of content knowledge and the pedagogical skills to teach the curriculum-resulting in poor learner performance (Taylor, 2019). In addition, it has been argued that PPPs, through the professional support they offer, the pedagogies they adopt, and the manner in which they monitor teachers, are likely to cause a turnaround in these schools (Ark Schools, 2015; Collaboration School Pilot Office, 2017). In that context, we critically examine these arguments and the effects of PPPs.

In a search to better understand the manner in which continuing professional development (CPD) is provided, a case study of two collaboration schools in South Africa was undertaken. As mentioned, SOPs are contracted to provide support to teachers through CPD activities designed to up-skill teachers and ultimately, improve learner performance. Whether this is indeed happening, needs to be assessed by detailing what is being offered and what the outcomes are. Currently, not much information is available on the topic and therefore this paper will focus on: "Who provides CPD?" "What kind of CPD is provided?" and "To what extent does the CPD provided meet teachers' needs?"

In addressing these questions, we begin the paper by contextualising the study and PPPs as well as providing literature on CPD. These sections are then followed by research methodology, findings, discussion, and conclusion sections.

Context of the study

This paper is the first in a series of papers on a research project on PPPs in education undertaken by the Cape Peninsula University of Technology's Centre for International Teacher Education with the rationale of understanding the experiences of teachers involved in PPPs. Eight collaboration schools participated in the project, and this paper focuses on CPD provided in two of the schools. Both are urban schools in disadvantaged areas, one being a high school and the other a primary school.

The CPD model (Figure 1) used by SOPs in the selected collaboration schools includes training and coaching. The approach to CPD in these schools is based on the philosophy of Get Better Faster by Bambrick-Santoyo (2016) to culminate in the ultimate goal of exemplary teaching. This form of CPD is drawn from the charter school system established in the United States. The model uses training and coaching to entrench the philosophy within the culture of the school.

It is within the context of collaboration schools that we will be mapping the forms of CPD.

Contextualisation of PPPs

The PPP model we are discussing in this paper describes the situation where the state devolves education authority to a private actor. The original purpose of this schooling model was to improve the quality of teaching and learning, thus improving learner outcomes in disadvantaged communities (Feldman, 2020; Hutchings & Francis, 2018). Globally, these models are found in America, the United Kingdom, and Liberia. Charter schools in the United States are publicly funded schools managed by private entities. However, they differ from traditional public schools with regard to their accountability procedures, admissions policies, and contracts with teachers (Cohodes & Parham, 2021). Regarding accountability, charter schools are allowed more operational autonomy because they are exempt from state and local regulations by comparison with traditional public schools (Baude et al., 2019; Sowell, 2020). This has led to fraud and the abuse of state funds in many United States schools (Burris & Bryant, 2019).

Academy schools in the United Kingdom are independent schools, funded by the state and managed outside local authority oversight (Eyles & Machin, 2019). It is interesting to note that almost all academies were previously state-run schools that have been converted or taken over and are now managed by school sponsors (Eyles & Machin, 2019). However, teachers in these schools are subjected to bureaucratic compliance and professional accountability (Brown, 2023). This has often resulted in increased workload, greater dissatisfaction, and loss of the teachers' voices (Brown, 2023).

The Liberian PPP schools model is known as partnership schools. In this model, private contractors are responsible for managing the school and providing professional development for teachers (Shakeel, 2018). However, the government owns the schools and is responsible for the maintenance of school buildings. In addition, the government pays the salary of one teacher per grade (Shakeel, 2018). Klees (2017) was not in agreement with the PPP schools model of Liberia; he argued that the government continues to retain a number of statutory powers and should be more effective in driving the necessary reforms in education. Such reforms include making changes to the curriculum, ensuring smaller class sizes, and training teachers.

Collaboration school is the term used to describe PPP schooling in South Africa. These schools are owned by the state whilst the management of the school is outsourced to a nonprofit SOP (de Kock et al., 2018). This model of schooling is seen as a solution for supporting underperforming schools in the Western Cape (Collaboration School Pilot Office, 2017) and thus improving the quality of education in those public schools (Schãfer, 2016). SOPs are contracted to provide high-performing support that focuses on educator development and school improvement in order to improve educational outcomes (Feldman, 2020).

The above paragraphs contextualise the increasing involvement of the different forms of PPP schools in the Global North and South. Emerging research has been either supportive of, or shown the benefits of PPPs (Baum, 2018; Helmy et al., 2020). However, there is a growing body of scholars raising a number of concerns about these PPPs. These scholars have raised questions about cost effectiveness, equity, and accountability (Verger & Moscetti, 2017). Scholars have also queried the ambiguity of the notion of PPP schools, and argued that PPPs are a form of the privatisation of public schooling, undermining the right to quality education for all as a public good (Spreen & Vally, 2014). Much of this research has focused on the governance of PPP schools and its effects; less attention has been paid to teachers and, in particular to CPD, which this paper addresses. The next section turns to a review of literature on CPD, which this paper reports on in relation to PPP collaboration schools in South Africa.

Literature on CPD

Research and policy have both drawn attention to the importance of CPD (Howell & Sayed, 2018; Tuli, 2017). This is also the case in South Africa where several policies attest to the importance of CPD, including the Integrated Strategic Planning Framework for Teacher Education and Development (Department of Higher Education and Training, 2011). CPD is important because it supports lifelong learning (Howell & Sayed, 2018; Mestry, 2017), improves knowledge and skills (Popova et al., 2018), and supports equitable and quality education (Howell & Sayed, 2018).

There are multiple models of understanding CPD, and this paper looks at the models of Borg and Ingvarson. Borg's model (2018) uses input, process, and output in relation to what is provided, how it is delivered, and what results emanate from the process. Adapting this framework as a basis, this paper considers who provides CPD, what kind of CPD is provided, and to what extent it meets the teachers' needs. Adding to this framework, we also use Ingvarson et al.'s (2003) model of understanding CPD. Figure 2 shows that there are four ways in which CPD programmes impact teachers: knowledge, practices, pedagogies, and efficacy. This model also includes three components as key indicators, namely, background variables, structural features, and opportunities to learn.

Background variables that play a significant role include the size of the school and the support it offers. Structural features of CPD programmes comprise the duration of activities and collective participation-meaning that all teachers need to participate, that is, compulsory participation. Opportunity to learn refers to learning being collaborative and inclusive of follow-up sessions. In addition, teachers need to receive feedback on their practice. These key indicators are requisite for quality CPD that results in benefits such as improved teacher knowledge, practice, student learning, and efficacy (Sayed et al., 2022).

In the context of this paper, it is important to recognise what effective CPD is, and which was defined by Darling-Hammond et al. (2017, p. 2) as "structured professional learning that results in changes in teacher practices and improvements in student learning outcomes." Research has pointed to various elements as important for quality and effective CPD, and which include frequent professional development, a clear focus on improving classroom pedagogy, and an enabling policy environment (Coburn, 2016; Hardy et al., 2018; Popova et al., 2018). Further, such research has pointed to effective CPD as focusing on teachers as adult learners and being provided by quality and expert facilitators (Darling-Hammond et al., 2017; Popova et al., 2018). Further, effective CPD should contain concrete goals and be more practical than theoretical in nature (Popova et al., 2018), and allow for reflective practice and feedback (Darling-Hammond et al., 2017). Reflection and feedback, critical components of adult learning theory, are seen as the two most powerful tools of effective CPD (Darling-Hammond et al., 2017). They mean that teachers would be able to apply the pedagogical knowledge and skills they obtained to the context of their school classrooms (Popova et al., 2018). Training offered by the experts should also be targeted, repeated, and coupled with coaching because training followed by coaching is more likely to yield continuous pedagogical gains (Conn, 2017; Wolf & Peele, 2019; World Bank, 2017). Targeted, in this context, means that it should be subject specific because the pedagogies of subjects differ.

However, CPD in the PPP schools model has been found to be rigorously scripted, and the training thereof prescribed (Sutcliffe, 2019). This often results in routine classroom application, and such an approach reduces the agential expression of teachers because it is compliance-driven and regulatory (Sayed & Soudien, 2021). This correlates with research done by Johns and Sosibo (2019) who found that teachers felt the CPD was compliance-driven and that policy implementation was forced upon them.

It is a flawed model of CPD that drives such an approach because it provides teachers with a narrow and limited range of skills that are constantly monitored (Sayed & Soudien, 2021). The fact that teachers have negative attitudes towards the CPD cannot be avoided. Such attitudes are derived from the activities being compulsory, single-session encounters organised by officials or administrators. In the process, the individual teachers' needs are not considered (Yurtseven, 2017). Furthermore, it has been found that when teachers are engaged with respect for their opinions and ideas, and context is considered, CPD has a positive effect on learner results (Popova et al., 2018). The involvement of the teacher in CPD cannot be overstated. According to Singh (2011), teachers must be involved in their professional development and they must understand the importance thereof. In addition, CPD is only effective if teachers are motivated to use the knowledge and skills they have gained. This happens when they take responsibility for, and are committed to, a desire to change (Makovec, 2018).

The above review of the literature pointed to the growing phenomenon of PPPs as a form of education provision and the scholarship associated with that. It also reviewed CPD, which forms the basis of the findings reported in relation to PPP collaboration schools in South Africa. Specifically, the review confirms that what is required is examination to understand who provides CPD, what kind of CPD is provided, and to what extent the CPD meets teachers' needs.

Research methods

Two collaboration schools were identified to be part of this case study. The methodology applied in gathering information to map the CPD provided in these schools followed a qualitative and a quantitative approach. A questionnaire survey collected quantitative data, while individual interviews were employed to determine qualitative findings.

Participants and setting

The schools participating in the study were two collaboration schools in the Western Cape, South Africa. One school was a primary school, and the other a high school-each being in a different school district and managed by different SOPs. Both schools were no fee schools in impoverished communities of the Western Cape.

The participants identified for interviewing were purposefully selected and comprised of school teachers and school leaders. The teachers were chosen by considering their 1) age, 2) gender, 3) race, 4) qualifications, 5) teaching experience, and 6) subject/phase specialisation. The population sample included eight teachers (four from each school), and four school leaders (two from each school-the principal and one other).

Data collection and analysis

Before the research project could start, certain administrative and ethical issues had to be attended to. These included gaining permission from the WCED to conduct the research, and receiving ethical clearance from the Cape Peninsula University of Technology. In addition, permission was gained from the SOPs and the schools to participate in the study. All participants were informed of the purpose of the study, of their rights, and given the assurance of anonymity. The teachers and school leaders also signed consent forms stating their voluntarily participation.

The research then commenced with a piloted questionnaire survey administered to all teachers in the two schools with regard to the form and content of the professional development offered to them in order to improve student learning outcomes. The data received were analysed using the IBM SPSS (28.1) statistical package. The second phase of the research followed with the collection of qualitative data. This was done by means of in-depth individual interviews. Subsequently, the qualitative data were analysed using thematic analysis.

Findings

From the analysis of both the quantitative and qualitative data, three sections emerged, namely, provision and content of CPD, limited form of CPD, and developmental needs of teachers. Prior to a discussion of these sections, it is useful to gain a perspective of how these sections relate to Borg's (2018) model: input (provision and content of CPD), process (limited form of CPD), output, which is the result of the process (to what extent does CPD provided meet teacher's needs).

Provision and content of CPD

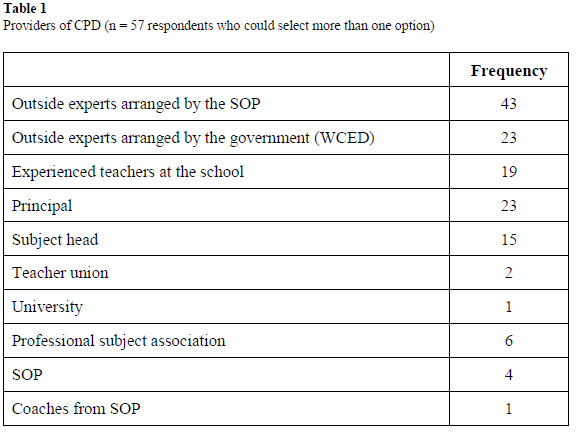

The providers of CPD are responsible for driving the CPD, thus it is of importance that we identify them. Table 1 presents an outline of this.

The survey data revealed that out of the 57 (n = 57) respondents, 43 indicated that the SOP arranged for or provided CPD, 23 indicated that it was arranged by the government (WCED), and one indicated that it was arranged or provided by coaches from the SOP. The term "frequency" in the context of this paper refers to the number of responses (respondents could select more than one response).

It is evident that the SOP takes the lead when it comes to providing CPD, specifically the outsourcing to experts. Coaches, however, provided the least CPD. Furthermore, the data suggest that the government (WCED) and school principals are also actively involved. This is consistent with Ingvarson et al.'s (2003) model where background variables such as school sector and school support play a significant role in providing CPD. The provision of CPD requires a theory of action in which school leaders (in this case the principal and SOP) support teachers in engaging with quality CPD (Tooley & Connally, 2019).

Table 2 reflects the focus/content of CPD programmes offered to teachers, and the usefulness thereof. This quantitative data reveals that fewer teachers attended CPD programmes involving psycho-social matters. These are issues such as special needs, dealing with violence, and teacher well-being. Teachers attended more programmes focusing on assessment of learning, positive disciplinary approaches and classroom management. It is evident that the focus of programmes is on how teachers can manage their classrooms effectively. Less time was spent on teacher well-being and psycho-social matters.

Regarding the highest value of usefulness, teachers were of the opinion that the CPD they received in relation to teaching and learning was either useful or very useful. This can be interpreted as meaning that what was learned during the activities could be applied in their classrooms. This is consistent with the views of Cole (2018) and Conn (2017) that the benefits of CPD include improved lesson planning, improved classroom management, and improved relations with learners, ultimately influencing learner performance. It must be noted that some teachers did not complete the highest value of usefulness section. This section is thus incomplete and no comprehensive conclusions can be derived from it.

According to the World Bank (2017) report, the content of CPD programmes needs to be targeted and subject specific because subjects have different pedagogies. This was not evident in the qualitative data, which reveals that the focus of CPD programmes is predominately on teaching and learning, as was expressed by a teacher at School 2: "Focus of our CPD programme is mostly on teaching and learning." We also found that the programmes did not focus on content or subject-specific knowledge. The principal from School l stated: "CPD programmes are not based on content."

A newly qualified teacher at the same school elaborated on this by commenting that the content of programmes was generic, for example, lesson planning, assessment, classroom management, data driven instruction, and the development of cognitive thinking. Further, a more experienced teacher at School 1 was of the opinion that the CPD programme lacked the fostering of critical thinking in children.

In School 2, the focus and content of the CPD programme did not only focus on the prescribed philosophy, but included a variety of topics. Teacher 2 mentioned:

We have done ICT workshops, we have had external experts come in to teach how to use Google, we have done mental health workshops, we have done a communication workshop, we have had the district psychologist come in to come and talk about the problem, how do I identify learners who have been through abuse, and how to identify learners who are going through trauma and how to respond appropriately.

The data suggest that the focus and content of CPD programmes was more inclusive in School 2, indicating that the operating partner was more flexible and considered the context of the school.

Limited form of CPD

Both schools and SOPs implemented the same philosophy, based on the books, Teach Like a Champion" by Lemov (2014) and Get Better Faster by Bambrick-Santoyo (2016). The philosophy involves two trajectories as a school management team (SMT) member at School 1 explained:

The CPD model is based on two trajectories namely, rigour, and management. Management trajectory-about learning and behaviour (how they behave and what you must do/say). Rigor trajectory-this is the thinking process, you must get children to think in this way for example, "do now," "I do," "We do," and "you do."

In that utterance, the teacher used the words "you must," which may mean that teachers are mandated to follow a prescribed and scripted approach. Sayed & Soudien (2021) also referred to this as a routine application wherein the agential space of teachers is reduced and CPD becomes compliance-driven-you must.

Furthermore, school leaders expressed different opinions about the implementation of these philosophies in their schools. Some concurred with what the teachers had to say, and expressed feelings that the philosophies were prescriptive and scripted. To illustrate this point, the principal from School 1 stated:

CPD programmes are based on two books, two bibles namely, Teach like a Champion and Get Better Faster . . . it's artificial, it's imposed.

With that assertion, the principal was suggesting that the implementation of the philosophy was rigid, allowing no room for deviation. She also implied that the CPD was not real, in other words there is a hidden agenda. According to Sayed and Soudien (2021), CPD may become compliance-driven and regulatory. The deputy principal at the same school concurred that the CPD model was very mechanical. Unfortunately, compliance and regulatory driven CPD has left teachers feeling that CPD is just a tick-box exercise where things are forced upon them and they not are treated as professionals (Johns & Sosibo, 2019).

In contrast, a SMT member at School 2 felt that the implementation of the philosophy at their school allowed for deviation and was flexible:

Get Better Faster, which is a metric made up by someone in the UK or the USA, so it's not entirely appropriate, but there are a whole bunch of techniques there that we try and incorporate.

The SMT member was implying that they only used the techniques appropriate to their school's context. He also highlighted that the approach or philosophy was not specific to the South African schooling context, thus they chose what to apply in their school. As noted by Popova et al. (2018), school context plays an important role when designing CPD programmes because the content of these programmes needs to fit the context.

With regards to what kind of CPD is provided, it was evident from the data that both schools and SOP's used training followed by coaching as a form of CPD. These opportunities to learn coincide with Ingvarson et al.'s (2003) model in which learning is collaborative and inclusive of follow-up sessions. Table 3 indicates the teachers' views about the coaching/instructional support they receive. The majority of responses in the survey data indicated that teachers agreed with the coaching support they received. Of the 57 respondents (n = 57), 25 strongly agreed that the coach had extensive knowledge about teaching, 26 responses strongly agreed that the coach was able to model practices and 23 responses strongly agreed that the coach had significant experience of being a teacher.

According to the above-mentioned quantitative data, the teachers valued the coaching/instructional support they receive at schools. Coaches were qualified, friendly, and able to model expected practices that teachers were expected to introduce into their classrooms. As noted by Darling-Hammond et al. (2017), facilitators of CPD need to be experts in subject matter and be able to guide teachers in the contexts of their classrooms.

The qualitative data affirmed the modality of CPD. Experienced teachers at both schools stated that teachers had to attend training sessions followed by weekly visits from coaches. Teacher 3 (School 1) stated:

Coaches come and watch your lesson and then give you feedback. You have a week to practice what you have to improve on. Next time they visit your classroom they want to see that you improved.

This is consistent with the views of the World Bank report (2017) that CPD programmes need to be repeated and followed up with coaching sessions. Darling-Hammond et al. (2017) also identified reflection and feedback as key elements of effective CPD that allow teachers to adapt their teaching practices. Ingvarson et al.'s (2003) model referred to creating opportunities to learn, and one such opportunity is providing feedback on practice.

As previously mentioned, the CPD programme focused on topics such as lesson planning, assessment, and classroom management. Many workshops are repeated, as stated by an experienced teacher at School 2:

So again, we have a routine, we have a programme, I'm a little annoyed because I feel like we're doing the same thing for the fifth time but there are new teachers who need it so that's not . . . it's not on me and reinforcement is good. (Teacher 3)

It is evident that the repetition of workshop topics can lead to frustration and be demotivating, and some teachers might even think it a waste of time (especially teachers who have longer service at the school). Teacher motivation plays an integral part in the implementation of effective CPD; if teachers are not motivated they are less likely to apply the knowledge and skills gained during a CPD session (Makovec, 2018).

Training sessions at both schools were facilitated weekly by SOP coaches and were compulsory for teachers to attend. This is consistent with Ingvarson et al.'s (2003) view that when structured, CPD needs to include collaborative participation. However, in the study by Johns and Sosibo (2019), teachers viewed compulsory attendance as something that was forced upon them, resulting in them feeling demotivated and not being treated as professionals. Yurtseven (2017) asserted that negative attitudes are derived from activities being compulsory.

In addition to the training, all staff members at both schools received instructional support through coaching. The coaches were qualified teachers with a minimum of five years teaching experience and appointed by the SOP. Coaching provided by the SOP was based on the books Teach Like a Champion (Lemov, 2014) and Get Better Faster (Bambrick-Santoyo, 2016). The model of coaching, however, was found to be mostly prescriptive and scripted as stated by the following participant:

Coaching model is prescriptive, scripted and controlling-policing of professional teachers. (SMT, School 1)

A post Level 1 teacher at the same school concurred that many teachers did not enjoy coaching because it was prescriptive and predictable. She elaborated that by prescriptive, she meant very rigid, scripted, and controlling: "You were told what to say and your practices were checked on." This is consistent with the views of Sayed and Soudien (2021) that prescribed coaching becomes compliance-driven and regulatory. Therefore, this approach to CPD is flawed because teachers are provided with a narrow range of skills and are constantly being monitored (Sayed & Soudien, 2021).

A more experienced teacher at the same school (School 1), did not agree with the approach of being observed and evaluated. She said:

Coaching-when the coach observes, "I dance to their tune" when they leave, I do my own thing. (Teacher 1)

Not all teachers like being observed and evaluated, some (as seen above) may see it as a top-down approach organised by management (Yurtseven, 2017) and thus have a defiant or negative attitude.

A newly qualified teacher at the same school indicated that the coaching model did not include how to assist learners with barriers to learning. This she found to be very frustrating because she required guidance regarding barriers to learning.

Commenting on the training and coaching teachers received, a SMT member at School 2 said:

There's a lot of development and space for exploration and how you use your coach and develop with your coach is entirely how much effort you put into it. Across the last four years, we've changed a lot and we've grown and we've developed, we have improved our classroom behaviour.

The data suggest that teachers experienced the modality differently in both schools. School 1 tended to be more prescribed and scripted while at School 2 the approach was more flexible, and experiences positive.

Teachers' CPD needs

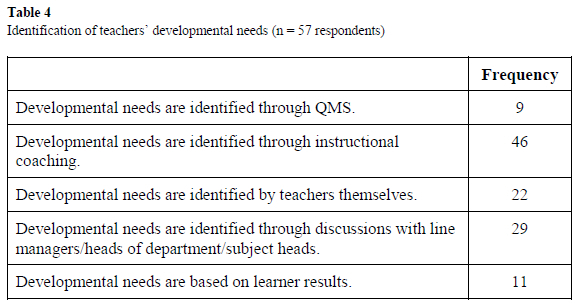

Table 4 represents how the developmental needs of teachers were identified. The data revealed that out of the 57 (n = 57) responses, nine indicated that developmental needs were identified through Quality Management System (QMS) a teacher management system adopted by the WCED, 46 through instructional coaching and 11 based on learner results.

It is apparent that instructional coaching plays a dominant role in the identification of teachers' developmental needs, while QMS was of much less significance in this regard.

However, the qualitative findings reveal that the developmental needs of teachers in School 2 were identified through their personal growth plans, which were derived from appraisals based on coaching and the school improvement plan. The latter plays a significant and integral role in enhancing school development. As disclosed by a SMT member at School 2:

The school improvement plan of the operating partner is so in-depth and it's so detailed and it's so specific. It has eight or nine versions across the year, as we continuously reflect and update and adjust, it is a living document, as opposed the WCED school improvement plan, which is historically done in November, distributed and filed.

In the light of the above statement, it is clear that the identification of developmental needs is done consultatively with the SOP and SMT, but excludes teachers. This top-down approach yields negative attitudes towards CPD because the individual developmental needs of teachers are ignored (Yurtseven, 2017). This practice seems to be characteristic within PPP schooling models as is seen in the academies model where the voice of teachers is limited (Brown, 2023).

However, in School 1, coaches play an integral role in identifying developmental needs. A head of department at the school said:

Developmental needs of teachers are identified by SOP coaches. Coaches meet and give feedback to the head of education (SOP), if they identify that five teachers don't have their entry routine right, they might do another workshop on entry routine.

Another teacher at School 1 concurred:

The SOP appraisal includes a personal growth plan-which is based on coaching and the coach's evaluation of the teacher. So, the teacher is excluded from identifying their own developmental needs-needs are prescribed.

Evidently, the identification of developmental needs presents challenges, especially for teachers given that it excludes their voices. As noted by Popova et al. (2018) and Singh (2011), teachers need to be involved in the identification of developmental needs because if they are engaged on their opinions and ideas, CPD has a positive effect on learner results (Popova et al., 2018).

Discussion

The following points form the basis for this discussion, namely, who provides CPD and what kind of CPD is provided, and to what extent does the CPD provided meet teachers' needs?

Who provides CPD and what is provided?

The evidence provided in the previous section suggests that teachers received sufficient support and opportunities to learn. It was encouraging to find that the SOP and WCED were the main providers of these programmes. This is significant because it shows that school managers recognise the importance of developing staff to improve teaching and learning. Background variables such as school support and school sector support play a significant role in the provision of CPD according to Ingvarson et al.'s (2003) model.

Although both schools used the same philosophy, each school implemented it differently. At School 1, teachers were mandated to implement a prescribed and scripted approach as per the books of Bambrick-Santoyo (2016) and Lemov (2014). However, as Sayed and Soudien (2021) cautioned, this routine application can become compliance-driven, resulting in the agential space of teachers being reduced and the pedagogy employed being restricted. When that happens, teachers lose their innovative spirit and teaching becomes mechanical (as one teacher alluded to). SOPs thus should review their approach to pedagogy and allow for more innovation in the classroom, thus giving the classroom back to the teacher.

School 2, by contrast, applied a flexible approach of implementation, in which elements of the philosophy were applied according to the context of the school. The school thus took ownership of the philosophy by customising it rather than imposing a philosophy that did not fully apply to their context. According to Popova et al. (2018) context plays an important role when implementing CPD.

Moreover, School 2 was more flexible because it considered the context of the school when deciding on content. It was encouraging to learn that those teachers found the CPD sessions to be very useful because they could apply their knowledge and skills to the classroom. This would ensure improved lesson planning, classroom management, and teacher-student relationships Cole (2018) and Conn (2017). However, according to the World Bank (2017) the content of CPD programmes also needs to be targeted, that is, be subject specific because the pedagogies of subjects differ. Unfortunately, this is lacking in current CPD programmes offered because the approach to pedagogy is generic and not subject specific.

Regarding the form of CPD provided, the evidence showed that both schools adopted training and coaching as vehicles of development. Although programmes do need to be repeated and followed up with coaching (World Bank, 2017), the repetition of compulsory training can become frustrating for more experienced teachers. Ingvarson et al. (2003) supported compulsory attendance and referred to it as collaborative participation. However, we are of the opinion that this approach is problematic because it can culminate in demotivated teachers with negative attitudes towards CPD-often resulting in learned pedagogy not being applied in the classroom.

To what extent does the CPD provided meet teachers' needs?

Regarding the identification of CPD needs, it became clear from the data that teachers were excluded from the process and a top-down approach was evident in both schools. In School 1, the coaches identified developmental needs when evaluating the practices of teachers during coaching sessions. In School 2, the SMT and the SOP identified needs through the detailed school improvement plan. Thus, developmental needs were disconnected from individual teachers' developmental needs. These practices of identifying developmental needs are concerning because literature has revealed that in order for CPD to be effective, teachers need to be involved in this practice (Popova et al., 2018; Singh, 2011). According to those researchers, if teachers are engaged and their ideas and views are considered, CPD has a positive effect on learner results.

The data also disclosed that in both schools the teachers generally valued the coaching support they received and regarded the coaches as being friendly, qualified, and able to model the practices they were expected to implement in practice. However, some teachers did not enjoy coaching because they found it to be predictable and prescriptive. This is problematic because coaching should not contain either of these elements. Furthermore, this approach to coaching provides teachers with a narrow range of skills-and they are constantly monitored (Sayed & Soudien, 2021). This means that the SOP and coaches restricted innovation in the classroom, were not collaborative in their approach to coaching, and were regulating teachers (prescriptive) and conditioning learners (predictable).

Conclusion

The purpose of this article was to map the form of CPD provided in PPP collaboration schools. The results show that restrictive characteristics of PPP schooling models may already be evident in the South African model because teachers are subjected to bureaucratic compliance and regulated professional accountability. This manifested through the actions of the main providers of CPD (SOPs), the content of CPD being prescribed and scripted, and teachers not being involved in the identification of developmental needs. Clearly, the approach adopted in the provision of CPD was restrictive and limited, and robbed the teachers of agency. In light of the above, it is recommended that policy makers and providers of CPD take cognisance that CPD is something we do with teachers, not to teachers- meaning, that teachers need to be included in all aspects of CPD provision. Furthermore, SOPs should rethink their approach of scripted and prescribed pedagogy and be more flexible in order to promote teacher agency. It is also recommended that further empirical research be done pertaining to the outcomes of the CPD model, namely, the impact that CPD has on learner achievement and improved pedagogy within a South African context. The findings of this study are significant for policy makers and implementers of programmes because they could help to shape and improve CPD in PPP collaboration schools. Finally, this study has contributed to existing knowledge of PPPs in education, specifically with respect to the provision of CPD.

References

Ark Schools. (2015). Supporting a new collaborative school model in South Africa. https://arkonline.org/news/supporting-new-collaborative-school-model-south-africa

Bambrick-Santoyo, P. (2016). Get better faster. Wiley.

Baude, P. L., Casey, M., Hanushek, E. A., Phelan, G. R., & Rivkin, S. G. (2019). The evolution of charter school quality. Economica, 57(345), 158-189. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecca.12299 [ Links ]

Baum, D. R. (2018). The effectiveness and equity of public-private partnerships in education: A quasi-experimental evaluation of 17 countries. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 26, 105-105. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.26.3436 [ Links ]

Borg, S. (2018). Evaluating the impact of professional development. RELC Journal, 49(2), 195-216. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688218784371 [ Links ]

Brown, M. (2023). Teachers ' experiences of participation in performance appraisal in an English academy school: Navigating bureaucratic compliance and professional accountability [Doctoral dissertation, University of Sussex]. https://ethos.bl.uk/OrderDetails.do?uin=uk.bl.ethos.887777 [ Links ]

Burris, C., & Bryant, J. (2019). Asleep at the wheel: How the federal charter schools program recklessly takes taxpayers and students for a ride. Network for Public Education. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED612862

Coburn, C. E. (2016). What's policy got to do with it? How the structure-agency debate can illuminate policy implementation. American Journal of Education, 122, 465-475. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/685847 [ Links ]

Cohodes, S. R., & Parham, K. S. (2021). Charter schools' effectiveness, mechanisms, and competitive influence. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/papers/w28477

Cole, M. (2018). An exploration of the long-term impacts of short CPD workshops [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. Northumbria University, England. [ Links ]

Collaboration School Pilot Office. (2017). Overview of the Western Cape collaboration schools programme. https://wcedonline.westerncape.gov.za/documents/CollaborationSchools/CollaborationSchools-InfoForParents.pd

Conn, K. M. (2017). Identifying effective education interventions in sub-Saharan Africa: A meta-analysis of impact evaluations. Review of Educational Research, 87(5), 863898. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654317712025 [ Links ]

Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., & Gardner, M. (2017). Effective teacher professional development. Learning Policy Institute. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/teacher-prof-dev.

de Kock, T., Hoffmann, N., Sayed, Y., & van Niekerk, R. (2018). PPPs in education and health in the Global South focusing on South Africa [Working paper]. Sussex University. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/237013789.pdf

Department of Higher Education and Training. (2011). Integrated strategic framework for teacher education and development in South Africa. https://www.education.gov.za/Informationfor/Teachers/ISPFTED2011-2025.aspx

Eyles, A., & Machin, S. (2019). The introduction of academy schools to England's education. Journal of the European Economic Association, 17(4), 1107-1146. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvy021 [ Links ]

Feldman, J. (2020). Public-private partnerships in South African education: Risky business or good governance? Education as Change, 24(1), 1-18. http://dx.doi.org/10.25159/1947-9417/4873 [ Links ]

Gamedze, T. S. (2019). The politics of accountability within the collaboration schools: Measures, processes and emerging issues [Master's dissertation, University of the Western Cape]. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/289120758.pdf [ Links ]

Green, P., & Connery, C. E. (2019). Charter schools, academy schools, and related-party transactions: Same scams, different countries. Arkansas Law Review, 72(2), 408444). https://scholarworks.uark.edu/alr/vol72/iss2/5/ [ Links ]

Hardy, I., Rönnerman, K., & Edwards-Groves, C. (2018). Transforming professional learning: Educational action research in practice. European Educational Research Journal, 17(3), 421-441. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904117690409 [ Links ]

Helmy, R., Khourshed, N., Wahba, M., & Bary, A. A. E. (2020). Exploring critical success factors for public private partnership case study: The educational sector in Egypt. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 6(4), 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc6040142 [ Links ]

Howell, C., & Sayed, Y. (2018). Improving learning through the CPD of teachers: Mapping the issues in sub-Saharan Africa. In Y. Sayed (Ed.), Continuing professional teacher development in sub-Saharan Africa: Improving teaching and learning (pp. 15-35). Bloomsbury.

Hutchings, M., & Francis, B. (2018). The impact of academy chains on low-income pupils. The Sutton Trust. https://policycommons.net/artifacts/3366358/chain-effects-2018/4165022/

Ingvarson, L., Meiers, M., & Beavis, A. (2003). Evaluating the quality and impact of professional development programs. Australian Council for Educational Research. https://research.acer.edu.au/professional_dev/3

Johns, L. A., & Sosibo, Z. C. (2019). Constraints in the implementation of continuing professional teacher development policy in the Western Cape, South African Journal of Higher Education, 33(5), 130-145. https://doi.org/10.20853/33-5-3589 [ Links ]

Klees, S. J. (2017). Liberia's experiment with privatizing education: Working Paper 235. Teachers College, Columbia University. https://ncspe.tc.columbia.edu/working-papers/files/WP235.pdf

Languille, S. (2017). Public private partnerships in education and health in the Global South: A literature review. Journal of International and Comparative Social Policy, 33(2), 142-165. https://doi.org/10.1080/21699763.2017.1307779 [ Links ]

LaRocque, N., & Sipahimalani-Rao, V. (2019). Education management organisations program in Sindh, Pakistan: Public-private partnership profile. Asian Development Bank. http://dx.doi.org/10.22617/BRF190018

Lemov, D. (2014). Teach like a champion 2.0. John Wiley & Sons.

Makovec, D. (2018). The teacher's role and professional development. International Journal of Cognitive Research in Science, Engineering and Education, 6(2), 33-45. http://doi.org/10.5937/ijcrsee1802033M [ Links ]

Mestry, R. (2017). Empowering principals to lead and manage public schools effectively in the 21st century. South African Journal of Education, 37(1), 1-11. http://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v37n1a1334 [ Links ]

Popova, A., Evans, D. K., Breeding, M. E., & Arancibia, V. (2018). Teacher professional development around the world. World Bank. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/349051535637296801/pdf/WPS8572.pdf

Romero, M., Sandefur, J., & Sandholtz, W. A. (2020). Outsourcing education: Experimental evidence from Liberia. American Economic Review, 110(2), 364-400. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20181478 [ Links ]

Sayed, Y., & Soudien, C. (2021). Managing a progressive educational agenda in post-apartheid South Africa: The case of education public-private partnerships. In J. Zajda Ed.), Third international handbook of globalisation, education and policy research (pp. 117-138). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-66003-1_7

Sayed, Y., Singh, M., & Pesambili, J. C. (2022). Developing an impact evaluation tool for continuing professional teacher development programmes in South Africa. DBE & VVOB.

Schäfer, D. (2016, March 16). MEC Debbie Schäfer hands over schools in Eerste Rivier. South African Government. https://www.gov.za/speeches/minister-debbie-schafer-hands-over-two-new-schools-eerste-rivier-today-16-mar-2016-0000

Shakeel, M. (2018). Public-private educational partnerships in developing countries: A special focus on Liberia. John Hopkins School of Education. https://jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/bitstream/handle/1774.2/62980/liberiaforwebsite.pdf?sequence=1

Singh, S. K. (2011). The role of staff development in the professional development of teachers: Implications for in-service training. South African Journal of Higher Education, 25(8), 1626-1638. https://journals.co.za/doi/pdf/10.10520/EJC121487 [ Links ]

Sowell, T. (2020). Charter schools and their enemies. Hachette.

Spreen, C. A., & Vally, S. (2014). Globalization and education in post-apartheid South Africa: The narrowing of education's purpose. In N.P. Stromquist & K. Monkman (Eds.), Globalization and education: Integration and contestation across cultures (pp. 267-284). Rowman & Littlefield.

Sutcliffe, K. (2019). Teacher professional development in collaboration schools, South Africa [Unpublished master's dissertation]. University of Sussex, United Kingdom. [ Links ]

Taylor, N. (2019). Inequalities in teacher knowledge in South Africa. In N. Spaull & J. Jansen (Eds.), South African schooling: The enigma of inequality: A study of the present situation andfuture possibilities (pp. 263-282). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-18811-5_14

Tooley, M., & Connally, K. (2016). No panacea: Diagnosing what ails teacher professional development before reaching for remedies. New America. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED570895.pdf

Tuli, F. (2017). Teachers professional development in schools: Reflection on the move to create a culture of continuous improvement. Journal of Teacher Education and Educators, 6(3), 275-296. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/jtee/issue/43274/525716 [ Links ]

Verger, A., & Moschetti, M. (2017). Partnering with the private sector in the post-2015 era? Main political and social implications in the educational arena. In C. Reuter & E. Stetter (Eds.), Progressive lab for sustainable development: From vision to action (pp. 245-269). Foundation for European Progressive Studies.

Western Cape Government. (2018). Western Cape Provincial Education Amendment Act (Act 4): Provincial gazette 8010. https://tinyurl.com/yv33h7ss

Winchip, E., Stevenson, H., & Milner, A. (2019). Measuring privatisation in education: Methodological challenges and possibilities. Educational Review, 71(1), 81-100. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2019.1524197 [ Links ]

Wolf, S., & Peele, M. E. (2019). Examining sustained impacts of two teacher professional development programs on professional well-being and classroom practices. Teaching and Teacher Education, 86, 102873. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.07.003 [ Links ]

World Bank. (2017). World development report 2018: Learning to realize education's promise. https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/abs/10.1596/978-1-4648-1096-1

Yurtseven, N. (2017). The investigation of teachers' metaphoric perceptions about professional development. Journal of Education and Learning, 6(2), 120-131. http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/jel.v6n2p120 [ Links ]

Received: 28 April 2023

Accepted: 12 September 2023