Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of Education (University of KwaZulu-Natal)

On-line version ISSN 2520-9868

Print version ISSN 0259-479X

Journal of Education n.88 Durban 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2520-9868/i88a08

ARTICLES

Visual methodologies as effective tools in reflecting on aspects of identity as an educator for inclusion and social justice

Antoinette D'amant

Social Justice Education Discipline, School of Education, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa. damant@ukzn.ac.za; https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8276-5792

ABSTRACT

As an educator for inclusion and social justice, it is essential to be self-reflective about all aspects of identity that relate to diversity and differential power relations. As part of this commitment, I am part of a group of critical academics and practitioners who comprise the South African Education Research Association (SAERA) Special Interest Group on Self-Reflexive Methodologies. In this paper, I include reflections on two artworks I created during self-reflexive exercises using visual methodologies. The first artwork led to my interrogating aspects of meaning and identity as a white person in post-apartheid South Africa. What emerged was, first, the need to confront my privileged racial identity that had been fashioned in a divided and exclusive past and second, I needed to reposition myself beyond my white socialisation, recognising the possibility of new frames of understanding and new identities, new social spaces, and new communities beyond the historical differences that keep South Africans separated and alienated.

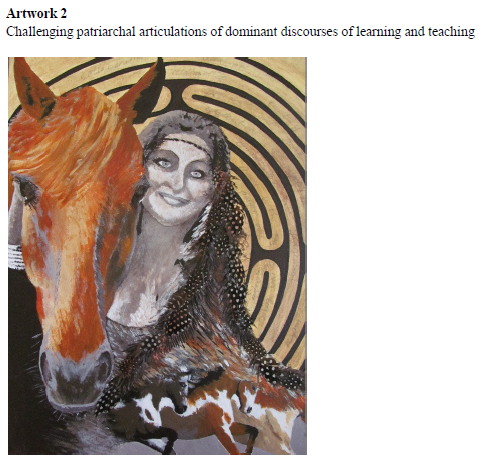

Critical reflection on the second artwork reveals embedded commentary on the need to challenge patriarchal articulations of the professional identity and dominant discourses of learning and teaching in academia. What emerged was the possibility of how lost feminine aspects of knowledge could inform teaching and learning strategies. These strategies could then contribute to a critical pedagogy that challenges the prevailing system of social relations and disrupts and unsettles the stereotypical assumptions of a dominant masculine discourse in academia. Here, I highlight the effectiveness of using visual methodologies to explore various aspects of identity, especially relevant for educators as transformative agents educating for inclusion and social justice.

Keywords: self-reflexive methodology; visual methodology; educating for social justice; racial identity; challenging patriarchal articulations of professional identity in academia

The need to educate for inclusion and social justice

By the last decade of the twentieth century, the exclusionary politics of South Africa's past had run their course. We needed to find a way to transform our social landscape by creating a radically inclusive and participatory social discourse in which diversity would be celebrated and equality of opportunity promoted. Such a discourse requires informed citizens who possess certain attitudes, a particular consciousness, and a commitment conducive to a deep sense of common good. However, a well-intentioned Constitution and a set of progressive educational policies are not enough to bring about the healing of the divisions of our past and the social transformation that our country desperately needs. South Africans still need to find ways of confronting and breaking down existing myths, deal with ignorance, prejudice, and the fundamental failure to respect others, and learn to relate to each other in ways that sustain social cohesion and co-operation without suppressing our differences. We need to put our energies intentionally into creating and maintaining education for inclusivity and sustainability in times of increasing inequality. Embracing such a progressive vision requires a radical restructuring of our society and our education system. Such a vision has important implications for teacher education in that educators still need to develop new ways of thinking and teaching that seriously challenge the prevailing system of social relations and that "enable attitudes to shift" (Howell, 2007, p. 90). We need to take on the mantle of transformative agents (Giroux, 1988), become cultural workers for self and social emancipation (Freire, 1998), and commit to teaching for social responsibility, social change, inclusion, and social justice (Cochran-Smith, 1991).

Background and context

Against an historical backdrop of exclusion, segregation, and unequal power relations, education in South Africa today is responsible for nurturing a vision that takes seriously the project of human liberation from all forms of discrimination and oppression, and that embraces the tenets of social justice. As a social justice lecturer, it is essential for me to always be self-reflective about all aspects of my personal and professional identity that relate in any way to diversity and differential power relations. My university work involves the critical interrogation of all forms of oppression (including sexism, racism, xenophobia, classism, ableism, ageism, religious oppression, cultural imperialism, heteronormativity, homophobia etc.) and how our various identities are linked to them. My investment and work in the specific field of social justice affords me a strong foundation in theories and models of oppression. It encourages critical interrogation of these issues (racism, sexism, oppression, and identity), and helps to disrupt the internalisation of prejudicial messages and manifestations that follow a systematic process of racial and gender socialisation. Ultimately, my role is to function as an agent of transformation, recognising and disrupting injustices, and to facilitate this in my students, in the hope of developing a world free of oppression. Seeing myself as accountable and responsible for challenging the oppressive power relations between different social groups and, in so doing, encourage anti-racist and anti-sexist change, I need to acknowledge and examine the issue of power relations and how these inform aspects of my identity formation. I must engage in constant critical interrogation of my own placed identity. I cannot expect my students to consider the ways in which their socialisation influences their personal and professional identities, without engaging in the same critical reflection. To this end, I am part of a group of critical academics and practitioners who comprise the SAERA Special Interest Group on Self-Reflexive Methodologies. We are committed to researching ourselves in the context of autoethnographic studies. As part of personal and professional transformation and social awareness, we employ various visual arts-based methodologies as tools for developing self-reflexivity. Since we are consciously and unconsciously invested in our identities, I have found using visual methodologies, and specifically process art, extremely helpful in critically unpacking these investments. In this paper, I offer critical reflections on two artworks I created as part of my commitment to researching myself in the context of autoethnographic studies employing visual arts-based methodologies. The critical reflection with which I have engaged through the process of creating and making sense of these artworks has prompted in me a deeper consideration of social change and of my role as an agent of transformation. This has also given me the opportunity and space to explore how issues that emerged from an analysis of these artworks were bound up with identity, power, and social structures.

Visual methodologies and arts-based research

Visual methodologies provide opportunities for investigating how the creative process can be a key feature of engaging a politics of location, positioning, and situation, or what Haraway (1991, p. 169) has called "the view from a body." According to Turner (2017, pp. 52-53), "[Y]ou can't argue with creative forms that come from this place of being fully present in the body as they are the result of a process of inwardness, and critical self-reflection."

Arts-based projects work from the premise that our inner world of imagery and metaphor holds a wisdom that bypasses the rational mind and that our souls present us with images before we have a thought or an emotion. The imagery in artworks created through arts-based methodology inevitably always links to what needs to be said and heard by the individual and by the greater society. I have come to understand this process as process art as opposed to outcomes-based art. Instead of having a firm idea of what a piece of art will ultimately look like and what its significance and meaning will be from the outset, process art is essentially

spontaneous, in the moment . . . free creative expression . . . and is always broader, more expansive and multi-layered than words and opens the door to our deepest intuitive wisdom. As soon as we connect to a deeper level of ourselves and create without pre-planning and holding fast to intentional outcomes, we are able to open up to possibilities outside the realm of the rational mind. Process art takes us to that place where we are able to connect with our souls at a deeper level and access imagery that keeps us connected to our inner compasses. It is a process of intuitive listening to where we are and how our lives need to unfold. Almost always, uncomfortable emotions and old patterns of thought or behaviour start to shift when we acknowledge them. (McClunan, 2013, para. 1)

Julia Cameron, in The Artist's Way, said that "the act of making art exposes a society to itself. Art brings things to light. It illuminates" (1995, p. 67). These interactive processes with visual texts have the potential to reveal embedded commentary on facets of our own identities in relation to our socio-political contexts. These interactive processes can lead to critical subjectivity that allows us to consider "what it is we have become, and what it is we no longer want to be" and enables us "to recognize, and struggle for, possibilities not yet realized" (Giroux and Simon, 1988, p. 17). This offers us the potential to "intervene in the formation of our own subjectivities" (p. 10), to define ourselves anew and speak our narratives of liberation and desire (McLaren, 1995). These insights can then inform teaching and learning and, ultimately, contribute to developing a critical pedagogy. It is the emphasis on embodied responses to the world and non-conventional ways of meaning-making that constitute both the rationale and the critique of arts-based research. Cameron (1995) expressed a belief that "artists and intellectuals are not the same animal" and that the halls of academia, "with their preference for lofty intellectual theorems, do little to support the life of the forest floor. . . [and that] academia harbours a subtle and deadly foe to the creative spirit." For her, "the subtle discounting" (p. 131) of anything artistic is dangerous and can lead to the neglect of including anything remotely artistic in the academic grove. When I chose the two artworks described in this paper, it was with the understanding of the significance of the brief for the exercises that led to their creation; we were told to bring portraits of ourselves and other images and writings to which we felt drawn or that had inspired us. The way that process art works is to engage in visual exercises simply as aesthetic exercises, indulging aspects of personal experiences and interests, with no initial critical agenda or scholarly thought on identity or professional practices. In other words, each of the critical reflections on the artworks I discuss in this paper began purely as an aesthetic exercise with no scholarly forethought or critical agenda behind them. Once created, I engaged critically and intuitively with each and noted the various themes and overall messages that emerged from the visual text. This is why the intuitive processes of process art and arts-based methodologies may appear to the rationally minded to work backwards. For Cameron,

[c]reativity cannot be comfortably quantified in intellectual terms. By its very nature, creativity eschews such containment. In a university, where intellectual life is built largely upon the art of critique and deconstruction-the art of intuitive creation and creative construction, in general, meets with scanty support, understanding or approval. (132)

Cameron warns that to become overly cerebral is, in itself, crippling and that the entire thrust of intellectualism runs counter to the creative impulse. This is not to say that an artistic endeavour lacks rigour but, rather, that artistic rigour is grounded differently from what intellectual life usually admits. There is no doubt that the boundaries of what has traditionally constituted academic research are being pushed and blurred through process art and arts-based methodologies. For me, these visual research techniques are profoundly forthcoming in terms of understanding personal and professional identity. They lead me to re-assess critically my subjectivities and open up possibilities of understanding and re-creating myself in respect of attitudes and behaviour regarding racial differences and racial identities.

Reflecting on the first artwork: Interrogating my whiteness, imagining my African-ness

For this artwork, I felt drawn to include a portrait of myself wearing a combination of Masai and Zulu beadwork as its central image surrounded by images of African elephants and some prose on the meaning of home. What began purely as an aesthetically appealing exercise with no scholarly thought or critical agenda on race or whiteness behind its creation, soon extended into a critical investigation of important issues hidden in the visual text. It became apparent that the artwork represented a commentary on the densely charged political context of whiteness and on the legacies of racial oppression and political struggle, thus placing this personal visual narrative within a dynamic public history. Given my intention to be accountable and responsible for anti-racist change, I realised the need to acknowledge power and privilege as central aspects of my identity formation and engage in constant critical interrogation regarding my own placed racial identity. Through this self-reflexive exercise, I reflect on the permanent elephant-race-in any South African room and in grappling with what it means to be white in a country that is still deeply racialised and deeply political (see McKaiser, 2011).

Insights and influences of other voices: The necessity of a black counter-gaze

I feel that it is important to acknowledge that while my authorship of this paper carries traces of a creator, none of us works in a vacuum. I cannot, therefore, forget those who helped to create conditions that supported my journey of reflection. I owe a debt to the insights and influences of predominant theorists in areas related to the white hegemonic gaze. Yancy (2012) and hooks (1992) have argued that whites themselves cannot solve the problem of whiteness without the critical voices of blacks, and they emphasise "the necessity of a black counter-gaze, a gaze that recognizes the ways of whiteness" (Yancy, 2012, p. 7). Throughout this process, I have taken heed of Yancy's (2008, p. x) warning that "whiteness is not an objective social location entirely independent of the self, but rather, a central feature of subjectivity, or one's lived, interior self." McKaiser (2011) highlighted for me that South African whites are unconsciously habituated into an uncritical white way of being and this made me aware that I need to be constantly critically aware of my whiteness and what this means to me and to others. This process has forced me to admit that I am a subject of everyday white normalcy and have "inherited the privileged status of being the 'looker' and gazer, with all the power that this entails" (Yancy, 2008, p. xviii). I am also inherently unfamiliar with the direction of a gaze that objectifies and critically analyses whiteness, being "more familiar with the role of the person that sees than of the person who is seen" (p. x). It has taken careful and critical reflection to distinguish my defensive responses from true critical engagement. I also owe a debt to my colleagues and friends of colour, who have facilitated my critical reflection on the complexities of white anti-racist efforts and have persevered and loved me through my "blind spots" (Yancy, 2008, p. ix), where my whiteness has clouded my critical reflection. I have been encouraged to see the world and my identity through the critical analysis and experiences of blacks, and while I may always fail to comprehend the sheer complexity of what it is like to be black, I am aware of the operations of white privilege and hegemony (see Yancy, 2012).

Appropriating another cultural identity

Reflection on this artwork has facilitated my growing sensitivity to larger questions raised in connection with a white person wearing traditionally African items of adornment. I could well be accused of appropriating another's cultural identity and using cultural objects that I have no right to make my own. I have come to understand this criticism in terms of Africa's history of colonisation and South Africa's legacy of apartheid. As a white person of European ancestry in South Africa, I am a walking reminder of colonialism and racism and all with which it is associated given its history of conquests, dominance, alien rule, and the humiliation of conquered people. Wearing these traditional cultural items could be interpreted as my exercising my power to take from others and make these things my own, following the example my forefathers set in exercising their white right to define and construct their own reality of dominance and privilege. I have realised through this exercise that I need to be mindful always of my whiteness and to consider visual representations and how they might tie into discourses invested in power that maintain certain constructions of the world.

Socialised to overvalue whiteness and devalue blackness

My reflection on this artwork prompted me to consider the burden of years of colonialism and racism and the need to engage critically with the issue of my whiteness. Yancy (2008, p. xxiii) noted that "whiteness is a form of conscious and unconscious investment that many whites would rather die for than call into question, let alone dismantle," and that "when it comes to race, we need forms of expressive discourse that unsettle us, that make us uncomfortable and unnerve us with their daring frankness" (Yancy, 2012, p. 30). In my professional and personal position, I realised that it was vital for me to engage with this challenge, however uncomfortable and unnerving, in the hope of building a better future. My feelings of discomfort during the process of critical interrogation of this artwork were red flags that showed me where further interrogation was needed and led me to a better understanding of why I was feeling uncomfortable. Generally, when we feel uncomfortable about any issue(s), we should take the opportunity to press on and further engage with the challenging questions that emerge.

My journey of reflection forced me to admit that I was born into an era in South African history where whiteness was supreme and was socialised to "over-value whiteness" and "devalue blackness" (hooks, 1992, p. 12), and raised in "segregated spaces that restricted black bodies from disturbing or tainting the tranquillity of white life, white comfort, white embodiment and white being" (Yancy, 2008, p. xvi). I realised that any investigation of my identity must necessarily explore my white body in terms of an historical ontology in which whites and blacks experienced vastly different histories with the latter enduring one of violence, oppression, and white power and world-making.

In unpacking her white privilege, McIntosh (1989) discovered that even though whites may readily grant that blacks are disadvantaged, they may be unwilling to grant that they are over-privileged. I have had to face the reality that as a white child growing up under apartheid in South Africa, I was carefully taught not to recognise white privilege and, thus, to remain oblivious to it. As McIntosh stated, this serves to deny and protect the phenomenon of white privilege. Many of the whites whom I encounter every day believe that they are not racists but fail to realise that they work from a base of unacknowledged privilege and dominance. I think it has been helpful for me as a white person to acknowledge my years of privilege and be honest and outspoken about it to other people. This has helped other white people whom I have encountered to recognise their own privilege that so often renders us all insensitive to the reality of racism. As Yancy put it, "[T]he production of the Black body is an effect of the discursive and epistemic structuring of white gazing and other white modes of anti-Black performance." These performances are not always enacted consciously but are "the result of years of white racism calcified and habituated within the bodily repertoire of whites" (Yancy, 2008, p. xix).

Learning to disarticulate the white gaze

For Yancy (2008), "disarticulating the white gaze involves a continuous effort on the part of whites to forge new ways of seeing, knowing and being" (p. xxiii) and hooks has argued that it is only when radical self-interrogation takes place that the white person can have the power to create new different cultural productions and that their acts of resistance can be truly transgressive (hooks, 1992). Through the cycles of interrogation and critical engagement with the visual text, I came to interpret this artwork as eroding the certainty of white dominance and indicating disloyalty to the supremacy of whiteness. For me, it suggested the possibility of me, as the coloniser, turning my back on the accepted norms of overvaluing whiteness and devaluing blackness, and, following Mitchell et al., (2011), deepening my understanding and acceptance of indigenous ways and cultures. As a white South African, I cannot remain ignorant of or unaffected by my whiteness. Of course, there are risks involved in confronting and critically engaging issues of racism and whiteness, but I stand in agreement with Yancy about the importance of raising unsettling questions to encourage critical engagement that is "not afraid to critique hegemonic forces" (Yancy, 2012, p. 16). This process of critical self-reflexivity encouraged me to engage the white world and call it forth from a different perspective. It helped me to foreground my whiteness, to name and identify whiteness as a site of privilege and power, and served to "unsettle my normative pretensions of whiteness" (p. 13). I also came to realise that just as it is important to remember "where we come from," it is as important to re-imagine "who we may yet become" (Mitchell et al., 2011, p. 10) and consider ways in which I could re-imagine the future. None of us need be passive victims, powerless against cycles of socialisation. Instead, we can, and must, disrupt them in the endeavour to build our world anew. This critical process reinforced and highlighted the realisation that I had the potential to "intervene in the formation of my own subjectivities" (Giroux and Simon, 1988, p. 10), to reconstruct myself as a new historical subject.

Insights from a Masai bride

My reflexivity prompted me to further interrogate the image in my artwork-more specifically, the beadwork featured in it. Young Masai brides are adorned with layers of exquisite jewellery on the day of their marriage as a symbol of the young woman preparing to leave her childhood home and begin a new life. According to Masai tradition, she leaves the familiarity of her mother's hut and family compound and follows her husband to a new home which brings with it different roles, responsibilities, and loyalties (Beckwith & Fisher, 2009). This knowledge highlighted for me the similarities of our individual contexts of change and disruption in leaving something behind and beginning something new. The artwork spoke to me of the possibility of overlapping domains, the intertwining and integration of different cultures, the emergence of a sense of common identities, the multiplicity, complexity, and fluidity of identity, and the dismantling of conventional modes of Western imperial thought in favour of developing hybrid identities. While remembering that we have all developed an acute sense of racial difference, separating them from us, I was offered the opportunity to imagine elements of a common identity that has the potential to bring people together rather than separate them. I join with Said (1994, p. 340) in believing that my commitment to the domain of racial liberation requires a vision that presents an "impossible union" of coloniser and colonised, white and black.

Reflecting on the second artwork: Challenging patriarchal articulations of dominant discourses of learning and teaching

For this second artwork I used as the central focus a portrait of me and my horse, Willpower, against a backdrop of the medieval labyrinth in Chartres Cathedral. Themes of understanding the equine perspective and acknowledging the lost feminine emerged from my interactive process with this visual text and uncovered embedded commentary on the need to challenge masculine articulations of the professional identity in academia and dominant discourses of learning and teaching.

I met Willpower, a gentle Chestnut gelding, about twelve years ago. After having two bad falls while riding other horses and losing my confidence and nerve to ride, it was suggested that I try riding him. Willpower had come to the yard from a previous owner at whose hands he had suffered abuse and neglect. He was an angry horse with a large saddle sore on his back, refusing to allow anyone too close to him. Months later, after his saddle sore had healed, he slowly succumbed to being ridden, but would constantly bite anyone attempting to groom him or saddle him up and would constantly rear in protest before going out of the gate on a ride. His mistrust of people in general was obvious. The suggestion that I try riding him was unnerving to say the least. As I was warned, Willpower reared at the gate. It was more an instinctual than conscious decision when I leaned over his head and rubbed his forelock, gently telling him we were both going to be alright. He calmed, walked out of the gate and we had a wonderful ride. My confidence grew a little more every time I rode Willpower. I can now say that I am a relaxed and confident rider again. I have spent as much time on the ground working with Willpower as I have in the saddle, and we have developed a respectful and loving relationship. He now knows my voice and comes to the fence with greetings when I arrive at the yard. He allows me to groom him and clean his hooves with no hint of biting, and he no longer rears at the gate. This magnificent creature has become an important part of my life, bringing me hours of joy and friendship. It seems that we have brought each other much healing. We have learned to trust each other and draw courage from each other. From a horse whose spirit had been broken and his body abused, I have witnessed a growing change in this beautiful gelding and have seen him regain his spirit and individuality. I have always treated him with love and respect, in contrast to his previous owner who viewed his mounts as machines to be dominated, used, and discarded without conscience. I ride him with a light yet persuasive touch, encouraging him as an "agile, thoughtful partner rather than a dissociative, machinelike mode of transportation" (Kohanov, 2013, p. 54). No doubt my gentleness would be criticised by those who believe riders need to show their horses who is in control. I believe people have historically relied too much on the use of abusive dominance techniques in their workings with horses and that there are other ways to work with these exquisite, sensitive, and intelligent animals. I remain committed to becoming a rider capable of harnessing the power and intelligence of my horse without conquering and repressing his spirit.

The equine perspective: Power with rather than power over

Kohanov (2003, 2013) has written extensively on mastering an alternative human-equine relationship. I find her writings intriguing and much of her philosophy informs my relationship with Willpower. I have chosen to develop a partnership with him that is one of trust, genuine caring, and mutual respect that demands compassion, sensitivity, and a continual awareness and respect for the other's dignity. I have learned that if I force him to do something through a show of dominance, he loses the trust that I have been at pains to build between us. But if I come alongside him in a manner that shows my intention to be an equal partner eager to work with him, the trust and mutual respect is maintained. In such an atmosphere there is no place for abuse or enslavement. The more I spend time with Willpower, the more I understand why Kohanov (2013) encourages riders to set aside the need to be in control and work, instead, within an ethic of collaboration. I found this notion inspiring in both my relationship with Willpower and in my work as an educator for inclusion and social justice. Understanding the equine perspective and translating horses' intensely social and nonpredatory perspective on power into a human context, "models how members of a free society are expected to treat their colleagues, and their subordinates" (p. 56), thus providing the ultimate education in being able to empower ourselves and inspire others towards social change.

This link between the equine perspective and educating for inclusion and social justice emerged very clearly for me through the interrogation of this artwork. Fundamental to both, is building relationships of trust and respect and developing power with others, rather than perpetuating the historical focus on power over others. As an agent of transformation, the nature of my relationship with my students is based on establishing safe environments of mutual trust and respect, coming alongside them in a supportive but challenging way, and encouraging them to critically examine sensitive and personal issues through a variety of methodologies and strategies. Working with students towards social transformation within an ethic of collaboration exactly mirrors the perspective that Kohanov described.

Acknowledging the lost feminine

My fascination with the Chartres labyrinth inspired the background image of this artwork. Walking the labyrinth is a spiritual practice believed to symbolise finding our path through life, to healing, balance, and spiritual wholeness. My interest in labyrinths lead me to visit Chartres on a recent trip to France and walk this ancient labyrinth that was constructed in the twelfth century and is one of the original Middle Ages labyrinths (Artress, 2006). The labyrinth is an ancient symbol of importance in heretic cultures, symbolising matriarchal spirituality and acknowledging the equal importance of both the masculine and feminine aspects of all things. This way of thinking was especially heretical in the Middle Ages since the Church did not recognise the equal role of the feminine but limited the feminine presence to the periphery of things sacred. The circular design of the labyrinth symbolizes "the inner map of knowing in women" (Artress, 2006, p. 54)-the feminine aspect that has historically been absent from much of life and spirituality in our Western culture or, in other words, the lost feminine.

Patriarchal power relations: Devaluing the feminine and over-valuing the masculine

Historically, men and women have inhabited very different worlds. In patriarchal societies, men have traditionally had the power and autonomy to make the rules and define knowledge and truth, while women have been domesticated and subordinated, rendered powerless and subservient, and have had their choices and potential restricted and limited. Women have lived for centuries under patriarchal rule being overlooked, disenfranchised, exploited, devalued, and often dehumanized. Years of masculine domination and the subordinating and devaluing of the feminine have resulted in the suppression and demonisation of many aspects of feminine knowledge and values. Cycles of socialisation (Harro, 2000) have proved to be a powerful force in keeping men and women trapped in rigid roles and definitions of masculinity and femininity. In addition, they produce and maintain stereotypes of which characteristics and qualities different genders should possess and to which they should aspire. Human qualities have been systematically divided, polarised, and labelled masculine or feminine, with the feminine being consistently devalued. This has resulted in our present tendencies to emphasise thought over emotion, logic and reason over intuition, territory over relationship, goal over process, strategy over responsiveness, force and coercion over collaboration, competition over cooperation, and judgement over compassion.

Essential to the equine perspective is the need to reclaim modes of wisdom and interaction, based not on conquest and domination, but on harmony and collaboration that are indicative of a more intuitive and compassionate spirit in having us relate to each other as sensitive beings worthy of collaboration rather than deserving of domination. In its quest to discover new ways of negotiating power, the equine perspective is directly aligned to the notion of acknowledging the lost feminine; both are movements facilitating the discovery of ways of being and working together during which the differences between individuals and social groups add richness to our lives rather than making us retreat into the traditional imbalances of the past.

While I created this artwork with no critical agenda and the two images to which I felt drawn include two different concrete historical moments for me, the embedded meanings in both visual images are remarkably similar. What emerged from these artworks was a commentary on the densely charged political context of challenging masculine articulations of the professional identity in education, reclaiming feminine aspects in educating for inclusion and social justice, and finding a healthy balance between the two.

The perpetuation of a masculine culture

Despite a pervasive belief that gender equality has been achieved in most first world countries, studies provide evidence that educational institutions remain inherently gendered and essentially patriarchal in being "defined, conceptualized, and structured in terms of a distinction between masculinity and femininity" (Britton, 2000, p. 419). Research results from Katila and Merilainen's (1999) study of gendered social and discursive practices give clear support to the dominance of patriarchy in the academic context. Their study demonstrated how women in academia are characterised as lacking in relation to the characteristics required for a professional identity and indicated that these are perceived to be "tied to a system of values in which identities defined as masculine are prioritized" (p. 4). The perpetuation of a masculine culture in many academic and educational institutions worldwide indicates how deeply rooted patriarchal articulations and underlying assumptions of the professional identity in academia/education are (Kantola, 2008). One of the most insidious aspects of contemporary sexism is its ability to remain camouflaged in everyday academic and educational practices, policies, notions, and ideas. Despite our being critical of the masculine culture in academia and education, the persistent and pervasive nature of sexism and patriarchy results in structural factors often being difficult to recognise. Many academics and educators thus opt for settling voluntarily into the position and space that is created for them in the masculine organisation and accepting it as their own. Katila and Merilainen (1999) have warned that after years of hearing how feminine characteristics are lacking in one respect or another and have no place in academia, many academics may start to believe in this as an objective fact.

Unsettling stereotypical assumptions of a dominant masculine discourse

Rather than trying to fit in with the dominant expectations, defining self and their relations with others in terms of the dominant discourse, and adopting its language in the endeavour to gain legitimacy, Katila and Merilainen (1999) have encouraged academics and educators to become agents of change who resist and challenge the dominant masculine discourse in academia through intentional acts. Such counter-identification of rejecting the dominant assumptions and expectations of the professional identity and dis-identification in replacing the dominant discourse allows radical alternative ideologies and pedagogies to flourish. Educators for inclusion and social justice need to be committed to and vigilant about unearthing the complexities of sexism and patriarchy in all aspects of the curriculum (Schmidt, 2005). In attempting to find my place in academia, I can sustain and reproduce the dominant discourse by fitting in and conforming to its underlying assumptions and expectations, or I can contribute to disrupting it and transforming it. Educating for inclusion and social justice within a critical pedagogy using non-conventional, non-conformist, creative and innovative methodologies, disrupts traditional academic discourses, and unsettles the stereotypical assumptions of the dominant masculine discourse in academia and education.

Historically, there have been powerful essentialist notions of male and female and the characteristics that have been assigned to each. We are all still products of history and socialisation processes that encourage the perpetuation of essentialist gender characteristics (Harro, 2000). Jewkes et al., (2015) have explored the critical question in developing processes of gender change as to whether it is indeed possible to deconstruct gender as a binary. They conclude by citing Alsop and colleagues (2002, p. 132) who have argued that "even critical studies of masculinity . . . retain a residual essentialism that makes a division between men and women and draws on the assumption that masculinity belongs to men and femininity to women (Jewkes et al., 2015, p. 118).

Feminist re-culturing

According to Noddings (2003), ethics, academia and education have so far "been guided by Logos, the masculine spirit, whereas the more natural and perhaps, stronger approach would be through Eros, the feminine spirit." She refers to the feminine ethic in the deep classical sense, rooted in receptivity, relatedness, and responsiveness, believing that "the notion of psychic relatedness lies at the heart of the feminine ethic" (p. 1). Despite highlighting contrasts between masculine and feminine approaches to ethics, academia, and education, Noddings did not intend to divide men and women into opposing camps, but, rather, has illustrated "how great the chasm is that already divides the masculine and feminine in each of us" and has suggested that we "enter a dialogue of genuine dialectical nature" in order to achieve transcendence of this divide. Highlighting such contrasts does not imply that logic should be discarded or that logic is alien to women. Noddings presents "an invitation to dialogue and not a challenge to enter battle" (p. 6). Re-culturing is not the exclusive domain of women; implementing feminist ideals into pedagogies is not new and is advocated by both female and male educators seeking to improve the practice of education in general. The intention of feminist critique is to suggest alternatives to the traditional masculine models (that focus on power over, competition, and domination), to subvert prescriptive methodologies in favour of developing redemptive methodologies that recognise women's ways of thinking and acting and incorporating a greater concern for context and explanation along with a diminishing concern for control and domination, and using the need to communicate (Kramarae, 1988; Wajcman, 1991).

I believe that when we abandon honouring the masculine and the feminine as equal and essential parts of an integrated whole, we suffer a great loss to our humanity. In acknowledging the lost feminine, I am not proposing a radical form of feminism that seeks to supplant the dominant discourse with women's modes of thinking and acting but I am advocating for the possibility of re-evaluating and re-defining the professional identity in academia and acknowledging feminine aspects of knowledge as valuable. Such a discourse aligns with the feminism of the new moral vision that integrates cultural feminism without radical feminism, and works towards the goal of addressing inequality as the result of the masculine bias, and thus creates, for both men and women, inclusion in a male dominated society (Donovan, 1994).

An issue of identity

Alternative teaching and learning practices challenge the deep culture of traditional discourses and power relations in academia and education that include forms of exclusion, non-participation, and authoritarianism. Attempts to transform this culture could lead to negative critique, disrespect, or perceived grounds for questioning my professional identity as an academic by those still embedded in traditional patriarchal discourses. Such "professional diminution" and "hidden forms of discrimination" (Kantola, 2008, p. 17) pose an ongoing challenge to advancing the agenda for inclusion and social justice in academia and education, and it is a professional and personal test of perseverance "trying to listen to our muse over the din of skeptics who don't believe in what we are doing" (Kohanov, 2013, p. 16). Disrupting existing deep cultures within academia and education necessarily incorporates the issue of identity and of how my identity as an academic and educator is defined for me (according to the traditional expectations of rational, logical, and quantitative thought) and how I might redefine this identity for myself (with the inclusion of intuitive and qualitative thought). Developing a critically inclusive pedagogy and praxis creates educational sites for greater social equity and inclusion, and enables educators to situate themselves as active social, cultural, and historical agents who are resisting and transforming history (McLaren, 1995), thus becoming "cultural workers for self and social emancipation" (p. 22). Disarticulating any dominant discourse involves a continual effort "to forge new ways of seeing, knowing and being" (Yancy, 2008, p. xxiii) and "demands uncommon courage and awareness and a creative intelligence willing to take chances outside conventional thought and behaviour" (Kohanov, 2003, p. 7).

Visual methodologies as a reflexive tool for a critically inclusive pedagogy

Educating for inclusion and social justice and critical pedagogy are closely aligned. Both recognise that meaning is produced through the construction of forms of power, experiences, and identities, and that these need to be analysed in terms of their wider political and cultural significance. Both necessitate a refusal to sustain codes of the dominant culture and existing relations of power and aim to reverse the tradition of demonising the other by affirming diversity. The argument for educational environments as sites of struggle, and for pedagogy as a form of cultural politics was made by Giroux and Simon (1988), who believed that academic and educational institutions should be places that expand human capacities to develop critical subjectivity that should lead to individuals being able to "intervene in the formation of their own subjectivities" and "exercise power in the interest of transforming the ideological and material conditions of domination into social practices which promote social empowerment and demonstrate democratic possibilities" (p. 10).

I am committed to carrying the torch of educating for diversity, inclusion, and social justice with passion, sensitivity, and effectiveness, and to developing my transformative capacity to challenge all forms of prejudice, discrimination, and oppression on a personal level as well as on an academic one. In this endeavour, I am aware of constantly positioning myself in the role of agent of transformation, cultural worker for self and social emancipation, and in doing so, I acknowledge the important role that critical self-reflection, emotion, intuition, relationship, process, responsiveness, collaboration, cooperation, and compassion play in my work.

I have learned much from interrogating my whiteness and the need for feminist re-culturing as a result of using Process Art with the two artworks I have presented in this paper. The insights gained from this process of interrogation have important implications for teacher education since they inform both professional and personal identities. By learning to reposition myself beyond my white socialisation and recognise the possibility of new frames of understanding and new identities beyond the historical racial differences and power relations that keep us separated and alienated, I am able to encourage student teachers to do the same. In interrogating the lost feminine, I realise the need to acknowledge feminine aspects of knowledge as valuable and, in so doing, advocate for the possibility of reevaluating and re-defining professional identities in education and academia (see Donovan, 1994).

There remains the need to maintain the clarity of intention along with courage and conviction to constantly disrupt and unsettle the stereotypical assumptions of a dominant white and masculine discourse in academia and education through alternative methodologies such as arts-based visual methodologies, and, specifically, Process Art, within a critically inclusive pedagogy. Critical self-reflection and alternative teaching and learning practices have the potential to challenge deep cultures of traditional discourses and power relations in education. Visual arts-based methodologies have proved to be highly effective tools in reflecting on aspects of my personal and professional identity and have highlighted important issues for me as an educator for inclusion and social justice.

References

Artress, L. (2006). Walking a sacred path: Rediscovering the labyrinth as a spiritual practice. Penguin.

Beckwith, C., & Fisher, A. (2009). Faces of Africa. National Geographic Society.

Britton, D. (2000). The epistemology of the gendered organization. Gender and Society, 14(3), 418-434. [ Links ]

Cameron, J. (1995). The artist's way. Pan Books.

Cochran-Smith, M. (1991). Learning to teach against the grain. Harvard Educational Review, 61(3), 279-310. [ Links ]

Donovan, J. (1994). Feminist theory: Intellectual traditions of American feminism. Continuum.

Freire, P. (1998). Pedagogy of freedom: Ethics, democracy and civil courage. Rowman and Littlefield.

Giroux, H. (1988). Teachers as intellectuals: Toward a critical pedagogy of learning. Bergin and Garvey.

Giroux, H., & Simon, R. (1988). Schooling, popular culture, and a pedagogy of possibility. Journal of Education, 170(1), 9-26. [ Links ]

Haraway, D. (1991). Simians, cyborgs and women: The reinvention of nature. Routledge.

Harro, B. (2000). The cycle of socialization. In M. Adams, W. Blumenfeld, D. Catalano, K. Dejong, H. Hackman, L. Hopkins, B. Love, M. Peters, D. Shlasko & X. Zuniga (Eds.), Readings for diversity and social justice (pp. 45-52). Routledge.

hooks, B. (1992). Black looks: Race and representation. Routledge.

Howell, C. (2007). Changing public and professional discourse. In P. Engelbrecht & L. Green (Eds.), Responding to the challenges of inclusive education in Southern Africa (pp. 90-136). Van Schaik.

Jewkes, R., Morrell, R., Hearn, J., Lundqvist, E., Blackbeard, D., Lindegger, G., Quayle, M., Sikweyiya, Y., & Gottzen, L. (2015). Hegemonic masculinity: Combining theory and practice in gender interventions. Culture, Health and Sexuality, 17(2), 112-127. [ Links ]

Kantola, J. (2008). Why do all women disappear? Gendering processes in a political science department. Gender, Work & Organization, 15(2), 202-225. [ Links ]

Katila, S., & Merilainen, S. (1999). A serious researcher or just another nice girl? Doing gender in a male-dominated scientific community. Gender, Work and Organization, 6(3), 163-173. [ Links ]

Kohanov, L. (2003). Riding between the worlds. New World Library.

Kohanov, L. (2013). The power of the herd: A nonpredatory approach to social intelligence, leadership and innovation. New World Library.

Kramarae, C. (1988). Gotta go Myrtle, technology's at the door. In C. Kramarae (Ed.), Technology and women's voices: Keeping in touch (pp. 1-14). Routledge and Kegan Paul.

McClunan, M. (2013, September 28). Intuitive art. Process art. https://michellemcclunan.com/creative-therapy/

McIntosh, P. (1989, July/August). White privilege: Unpacking the invisible knapsack. Peace and Freedom Magazine, 10-12.

McKaiser, E. (2011, July 1). Confronting whiteness. The whiteness debate. Mail & Guardian online. https://mg.co.za/article/2011-07-01-confronting-whiteness/

McLaren, P. (1995). Critical pedagogy and predatory culture: Oppositional politics in a postmodern era. Routledge.

Mitchell, C., Strong-Wilson, T., Pithouse, K., & Allnut, S. (2011). Introducing memory and pedagogy. In C. Mitchell, T. Strong-Wilson, K. Pithouse & S. Allnut (Eds.), Memory and pedagogy (pp.1-14). Routledge.

Noddings, N. (2003). Principles, feelings and reality. Theory and Research in Education, 4(1), 9-21. [ Links ]

Said, E. (1994). Culture and imperialism. Vintage.

Schmidt, S. L. (2005). More than men in white sheets: Seven concepts critical to the teaching of racism as systemic inequality. Equity and Excellence in Education, 38(2), 110-122. [ Links ]

Turner, T. (2017). Belonging. Her Own Room Press.

Wajcman, J. (1991). Feminism confronts technology. Pennsylvania State University Press.

Yancy, G. (2008). Black bodies, white gazes: The continuing significance of race in America. Rowman & Littlefield.

Yancy, G. (2012). Look, a White! Philosophical essays on whiteness. Temple University Press.

Received: 11 February 2022

Accepted: 6 July 2022