Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of Education (University of KwaZulu-Natal)

On-line version ISSN 2520-9868

Print version ISSN 0259-479X

Journal of Education n.88 Durban 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2520-9868/i88a05

ARTICLES

Reframing policy trajectory for inclusive education in Malawi

Ben de Souza

Department of Education, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa. souzaben@outlook.com; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6746-9511

ABSTRACT

This qualitative study proffers ways of reframing the policy trajectory for inclusive education in Malawi. The study involved a document review of inclusive education policies and strategies and in-depth semi-structured interviews with mainstream teachers at a secondary school in Malawi. The results from the document review show that the framing of the education policies and strategies regarding inclusive education pedagogy as an educational practice is influenced solely by learners' cognitive proficiencies. However, the analysis of the semi-structured interviews points towards multi-scalar pedagogical responses to inclusive education. Therefore, I argue that the framing of inclusive education policies and strategies ignores crucial interactive schooling systems such as the onto-pedagogical framings of mainstream teachers and specialists that shape pedagogy in the context of inclusivity. The study concludes that inclusive education policy formulation and implementation requires interactions among and across schooling systems, such as mainstream and specialist teachers, and not merely attending to the epistemological needs of learners. I recommend a bio-ecological systems policy reframing that could help the Malawian and other southern African education systems to use different factors that influence inclusive education.

Keywords: education policy, inclusive education, pedagogical responses, policy reframing, Malawi

Introduction

Inclusive education is now on a global agenda that has impelled countries to increase their efforts towards its implementation and realisation. Most countries from the Global North and the Global South have instituted policies that foster inclusion in mainstream education (Slee, 2018). As part of the efforts toward implementing international treaties on inclusive education, many Southern African countries have developed their policy frameworks (de Souza, 2021; Mitchell & Sutherland, 2020). Since the Salamanca summit in Spain in June 1994, the Education for All conference in Thailand in 1990, and the World Education Forum (Dakar Framework of Action) in Senegal in 2000, Malawi has undeniably registered a tremendous improvement in inclusive education that is evident in the formulation of policies and the incorporation of learners with disabilities in mainstream classes (de Souza, 2020). In this regard, Malawi drafted and adopted several policies and strategies, including the National Education Policy (2016) and the National Strategy on Inclusive Education (2017-2021), to speed up the implementation of inclusivity in its education systems (Mgomezulu, 2017).

Nonetheless, there are doubts about whether countries are adopting their promise of inclusive education (Slee, 2018). For many Southern African countries, the primary concern is whether inclusive education equips mainstream teachers to educate learners with disabilities alongside their peers in the mainstream classroom as stipulated by national education policies and strategies (de Souza, 2020). The philosophy of inclusive education expects mainstream teachers to enact inclusive practices regardless of the learning barriers that learners with disabilities face in mainstream education (Kamchedzera, 2010). I argue that the framing of inclusive education policies and strategies ignores fundamental interactive schooling systems such as mainstream and specialist teachers who shape pedagogy in the context of inclusivity and discourse inclusive education as a privilege for learners.

Purpose and questions of the study

Purpose

The study aims at proffering ways of reframing policy trajectory for directing pedagogical responses in inclusive education in Malawi and other educational settings that share similar education circumstances especially in the Southern African region.

Objectives:

1. to proffer a theoretical model for reframing inclusive education policy trajectory;

2. to propose a methodological framework for formulating inclusive education policies; and

3. to demonstrate an evaluation model for inclusive education policy implementation.

Questions

1. Which theoretical underpinnings can reframe inclusive education policy traj ectory?

2. How can inclusive education policies be formulated?

3. What are viable ways of evaluating inclusive education policy implementation?

Legal and policy context for inclusive education in Malawi

In Southern Africa in general, and Malawi in particular, policies and strategies on inclusive education support opportunities for inclusivity. The policies and strategies accentuate a need for educating all children together in mainstream schools. For instance, the National Policy on the Equalisation of Opportunities of Persons with Disabilities (NPEOPD, 2006) aims to protect and promote the rights of persons with disabilities. The NPEOPD acknowledges that universal education is unobtainable if persons with disabilities are excluded and outlines strategies for the inclusion of persons with disabilities in education and training, including the "incorporation of special needs training in the teacher-training curriculum [and] supporting and encouraging inclusive education" (Malawi. Ministry of Persons with Disabilities and the Elderly, 2006, pp. 23-24).

In Malawi, education colleges and some universities train mainstream teachers for primary and secondary education. The NPEOPD strategies can be incorporated into the teacher education curriculum to ensure the inclusion of teachers in inclusive education (Baranauskiene & Saveikiene, 2018). When they teach, mainstream teachers would be mindful of inclusive education and would demonstrate this by preparing effective strategies for supporting learners with disabilities. However, teacher education curricula in Malawi seldom incorporate issues of inclusive education (Kamchedzera, 2010). Thus, in-service mainstream teachers cannot support inclusivity (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation, 2020).

Legal and policy frameworks need to respond to contemporary inclusive educational needs (Chilemba, 2013). The Disability Act of 2012 explains policy responsiveness and inclusive educational needs. The Act proclaims that "the government shall recognise the rights of persons with disabilities to education based on an equal opportunity and ensure an inclusive education system and lifelong learning" (Malawi. Ministry of Justice, 2022, p. 7). The Act recognises everyone's right to education and the government talked about making premises and buildings, including schools, accessible to everyone regardless of disability and aimed to remove exclusion from the education system and provide equal access to education to the less privileged, just as it would for persons without disabilities. Surprisingly, the Disability Act of 2012 did not address the plight of school-going children with disabilities who have been abducted (and often killed) since 2010 to date because of beliefs about albinism. The Act was the only legislative text to address the inclusion of learners with albinism and reduce misconceptions about this. Notwithstanding this, the Act remained mute. The muteness was a missed opportunity since the Act could have assisted in the formulation of the National Education Policy of 2016 and the National Strategy on Inclusive Education of 2017, that did not highlight this evident need for inclusive education.

The mismatch of policy formulation and practice implementation remains a significant setback in inclusive education. For example, the Malawian Child Care, Protection and Justice Act of 2010 illustrates this situation. The Act resonates with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child. Part II, Division 5 of the Act focuses on registering children with disabilities. In the same division, Section 72 stipulates that

a local government authority shall keep a register of children with disabilities within its area of jurisdiction and give assistance to them whenever possible to enable those children to grow up with dignity among other children and to develop their potential and self-reliance. (Malawi. Ministry of Justice, 2010, p. 29)

Confining children with disabilities to their local areas limits their prospects of acquiring education in various mainstream schools across Malawi. For example, Malawi has national government secondary schools that select students on merit and not on geographical location. The fact that a child with a disability has to be under the jurisdiction of a local authority does not inspire the spirit of striving for excellence in education seen in their peers. Moreover, this situation does not align with the philosophy of inclusive education. The Act can influence the formulation of policies that confine learners with disabilities to special schools within their localities, thus defeating the ends of inclusive education.

To recap, inclusive education overwhelms policy development in the broader educational policies worldwide, including in Malawi (Baranauskiene & Saveikiene, 2018; de Beco, 2018). However, Chimwaza's (2015) study found that most of the teachers in Malawi believe that the provision of physical accommodation in the schools guarantees educational success for the learners with physical disabilities. Yet, there is more to be done, especially in the teachers' practices, because dealing with disability as a reality needs a holistic approach (de Souza, 2020). Moreover, implementing policies in education is approached as a linear process so teachers do not realise the complexity of the process (Mbewe et al., 2021). For example, teachers often fail to realise that they must engage with inclusive education policies on behalf of the learners (Chimwaza, 2015). Hence, there is no doubt that teachers' perceptions, understandings, and interpretations of the national inclusive education policies and strategies are critical for inclusive pedagogical proficiency.

Bioecological systems theory in inclusive education

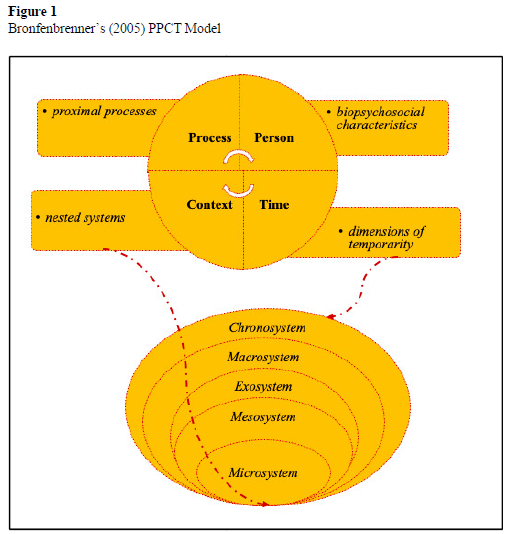

This study employs Bronfenbrenner's (2005) bioecological systems theory to interrogate the pedagogical responses emerging from education policy and teacher practices on inclusive education in Malawi. Key to this theory is the tenet that development and learning do not occur in a linear sequence. Instead, development and learning are very sophisticated processes involving the interaction of different systems in one's environment. This study adopts a particular theoretical research design that Bronfenbrenner (2005) termed the Process-Person-Context-Time Model (or PPCT Model), as explained below.

Process is a relationship between an individual and their context (Bronfenbrenner, 2005). Essentially, this component is comprised of proximal processes-the nature and form of frequent interactions an individual encounters with their physical, social, and cultural environment. The individual entails a child and the environment entails factors that influence the child's development. Bronfenbrenner designated the proximal processes (the key feature of the Process) as "primary engines of development" (2005, p. 6). However, for this study, the process means the interactions of mainstream teachers with their practices, learners, peers, policies, and affiliated institutions.

Person is an individual and biopsychosocial characteristic (Bronfenbrenner, 2005). This definition entails that the Person component theorises individual characteristics that determine the individual's development. The Person component is comprised of unique characteristics such as the experiences and beliefs of the developing child. For this study, mainstream teachers were the unit of analysis, and their biopsychosocial characteristics included their experiences and beliefs about inclusive education policy and practice.

Context refers to nested levels or systems in the ecology of human development (Bronfenbrenner, 2005). The Context component is comprised of micro-, meso-, exo- and macro-systems. Put differently, the Context component of the model is comprised of bioecological systems that intertwine with other model components, i.e., Process, Person, and Time components.

Time entails "dimensions of temporality" (Bronfenbrenner, 2005, p. xv). The Time component reminds us that a theory is very fluid and much more prone to further development than dogmatists would have it. Initially, Bronfenbrenner overlooked the essence of time in human development. A significant revision of the theory saw the chronosystem added as an element of human development.

Figure 1 below summaries the Process-Person-Context-Time Model (or PPCT Model):

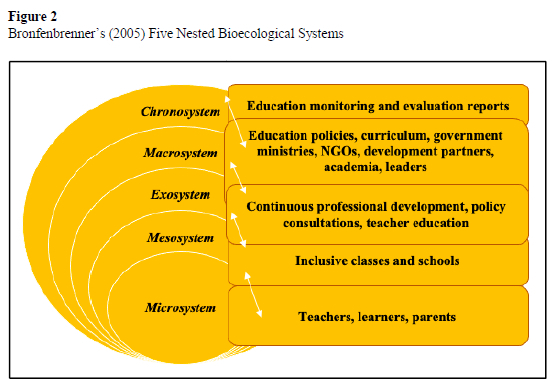

The PPCT model is employed in this study to explain different systems and the nature of interactions between and across the systems in inclusive education. In the study context, mainstream teachers, specialist teachers, and learners are theorised as elements of the microsystem. When these elements of the microsystem interact, such as through instruction, they form a mesosystem. Education factors such as inclusive education policies and strategies are theorised as part of a macrosystem. However, when teachers interface with these policies and strategies, for example, during professional development activities, they form an exosystem because the learners are not directly involved, although the effects of the interactions funnel down to the learners through the mesosystem. The chronosystem (Time component) is included for its ability to track strides made in inclusive education. The study uses the PPCT model to propose a policy trajectory framed from pedagogical responses to inclusive education that are emerging in a multi-scalar fashion.

Research methodology

Philosophical design

The study was framed around ontology, epistemology, and methodology that conform to the tenets of a qualitative research approach in general and critical realism under-labouring in particular. In a philosophical sense, ontology focuses on the nature of reality that preoccupies an inquiry (Hart, 2010). In this study, the reality was the practices of mainstream teachers in inclusive education. The focus was on whether and how their practices help develop inclusive pedagogy. Expectedly, not all teachers had similar practices as far as inclusivity was concerned. Since critical realism offers a less restrictive and more inclusive perspective, the study captured different meanings that teachers construct from their practices and experiences (see Danermark & Bhaskar, 2006).

Epistemology concerns itself with knowledge and how it is acquired (Flick, 2018; Roth, 2019). The epistemological standpoint of the study is that teachers construct their knowledge. In the study, I was interested in how teachers construct knowledge. For instance, I sought to explore how teachers understood the issues of inclusive education. A critical realist perspective became important since it afforded space for explaining the understandings impartially and elaboratively (see Danermark & Bhaskar, 2006). Within the critical realist under-labouring, I was concerned with the appropriateness of the chosen methods to generate data that addresses the research purpose. I assumed that the teachers had multi-layered understandings of their practices. Thus, these practices were perceived better through a critical realist perspective since it construes reality from a multi-layered point-a necessarily laminated system (Danermark & Bhaskar, 2006).

Participants and methods

The study involved document review and in-depth semi-structured interviews with five mainstream secondary teachers at one inclusive school in Blantyre, Malawi. The participants were purposively selected based on the criterion that they had learners with disabilities in their classrooms. The participants were requested to participate willingly in the study after I acquired enrolment information from the head of the institution and consent from the participants themselves. The interactions with the participants were situated in the critical realist perspective to challenge the dichotomic binary opposition that institutionalised exclusion in the education system by othering disabilities and brought new ontological framings that require teachers to embrace inclusive education into discourse.

Data analysis

The study employed a threefold data analytical framework: data triangulation; thematic analysis; and the theoretical framework. Data triangulation was an ongoing process that happened concurrently and synchronically between document review and interviews. Insights drawn from the document review analysis were applied in the in-depth face-to-face interviews. Second, a thematic method was used to analyse the interviews and document reviews. In essence, thematic analysis organises research data by identifying central ideas observed in data (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Thomas & Harden, 2008). Therefore, thematic analysis was crucial to uncovering key and central themes and categories at an inductive level in the data. Central themes and categories were drawn in both emic and etic fashion from the theories, literature, research questions, and data.

Ethical considerations

Rhodes University Ethics Committee gave me ethical clearance for the study. The gatekeeper's permission was obtained from the South-West Education Division Manager in Blantyre, Malawi. The negotiation process emphasized that participation in this study was voluntary. Informed consent of the participants in the study was used to negotiate access and permission to acquire, use, and refer to the data collected (see Maree, 2016; Sotuku & Duku, 2015). Each participant in the study was requested to sign an informed consent form and return it to me as the researcher. The informed consent form was evidence of their agreement to be included and involved in the study. The purpose of the study was explained verbally to the participants before they were requested to sign the consent forms. The participants who opted to participate were informed that they reserved the right to withdraw at any time should they find it necessary.

Research findings

This section presents research findings from interviews with five mainstream secondary teachers at one inclusive school in Blantyre, Malawi. These findings are presented in a synchronising manner with the document review analysis.

Emergence of communities of practice for inclusive education

The interviews show an emergence of communities of practice for inclusive education. Teachers recognised that inclusive education involves interactions between and across schooling systems. Participant 1 said,

It is very important to do what we call inclusive education because, first of all, I believe all of them are students, all of them have got a right to education.

Participant 3 offered another perspective in saying,

I believe that when you educate them together, they also learn from each other because the knowledge that these students have is not only the knowledge they get from the teachers, but they also help each other. So, if you do inclusive education, those with disabilities might benefit from the able ones.

Moreover, for Participant 5,

Some of us teachers we do not know the sign language, so if they learn together with those that are able those are kids they learn faster, they master the sign language and when they are in class and if maybe you are delivering something and they seem not to understand their friends come in and help them.

In a sense, these supportive systems that emerge from inclusive education can be termed communities of practice influenced, theoretically, by microsystems such as learners without disabilities.

Hitherto, a critical reading of the National Education Policy of 2016 suggests that it overlooks the microsystems that influence inclusivity. A microsystem is a "pattern of activities, roles, and interpersonal relations experienced by the developing person in a given face-to-face setting with particular physical and material features and containing other persons with distinctive characteristics of temperament, personality, and systems of belief (Bronfenbrenner, 2005, p. 148). The original tenet of the microsystem (see Bronfenbrenner's ecological and socioecological theories) put a child (a learner) at the core of this system. The National Education Policy of 2016 seems to frame inclusive education as focusing simply on the learner with disability. However, according to Bronfenbrenner's revision of the theory in 2005, this does not mean that the child would be the only unit of analysis in this system since they interact with other factors such as teachers, parents, and peers (Swartz, 2015). In essence, it is possible to theorise and centralise other factors apart from the developing child. Thus, a new policy framework on inclusive education needs to recognise mainstream teachers and their practices as a unit of analysis in the microsystem.

Differentiated epistemic strategies

Lynch et al., (2014) established that learners with disabilities, specifically those with albinism, do not have the same educational opportunities as their peers. The study attributed this worrisome development to several factors, including a lack of relevant materials and incorrect information about people with albinism. The interviews conducted with the mainstream teachers suggest that the trends in inclusive education are shaping up in an interactionist fashion that has learners without disabilities and specialist teachers assisting mainstream teachers in inclusive pedagogy for learners with disabilities. For example, as Participant 2 said,

When you go to a class with students with hearing impairment, you are supposed to stand in front. When you stand in front, you have to look at the students, mainly focusing on those that have got a hearing impairment so that if they, of course, they will not get what you are saying, lip read, they will sense what you are saying.

Furthermore, for Participant 4,

We are encouraged to write on the board so that if they fail to understand the language when they read at the chalkboard, they get the points.

Additionally, as Participant 1 put it,

We also learn basics of sign language, so if you can mix up those things: sign language and your words, they learn better.

Within mainstream education, according to Participant 5,

[w]e also have teachers from the special needs department. They come in class, and they do interpret the sign language, whatever you are saying they interpret to sign language, whenever they have got questions maybe when you ask a question to those students, and whenever they are answering the question, they will speak to their specialist teacher, and the teacher tells you.

Interestingly, for Participant 3,

If the specialist teacher is not available, other students without disabilities are also there to help.

These developments speak to the efforts made by communities of practice presented earlier, but they directly affect epistemological access in a mainstream class.

Nevertheless, in the National Education Policy of 2016, the Ministry of Education is a leading and centralised partner in implementing the policy without necessarily having a clear division of labour among other interested and concerned stakeholders. This situation ignores the fact that elements of microsystems need to interact to form mesosystems for inclusivity. Theoretically, a mesosystem is "a system of microsystems" (Bronfenbrenner, 2005, p. 160). This definition entails a mesosystem interacting with two or more factors within a microsystem. For example, an interaction between a developing child and parents forms a mesosystem. Other interactions could be between a teacher collaborating with another teacher and a teacher interacting with students. Central to the mesosystem is the influence that units of the microsystem have on each other (de Souza, 2020). Thus, a new education policy framework for inclusivity needs to acknowledge that mainstream teachers have the potential to influence inclusive pedagogical proficiency, which would eventually influence inclusive practices in schools, and theoretically, this assumption would manifest in the mesosystem.

Experience-informed pedagogical framings

The interviews with mainstream teachers found that they try to provide education for all learners regardless of their disabilities. Indeed, for Participant 5,

[a]s a human being, you always have the passion for teaching those students with disabilities. For my part, I am pleased whenever that student, maybe even out of ten concepts that you were trying to teach and even if they grab two that is better rather than if they go outside completely with nothing.

Participant 2 said that

as somebody who has taught these students for a long [time], I feel delighted when they grasp the concepts that you teach, but also, I feel terrible whenever you go there, and you come out, and you see that they have grasped nothing because sometimes you ask them, they say they have not heard anything, maybe you ask a friend to ask them what they have learned they will say they have not got anything. So, you feel bad and say why they are here then?

Participant 4 suggested that

because they are here to learn so if they are not getting anything it means the purpose of coming to school is not there, it is like they come to school to pass the time. But if they grasp something better and from my experience, the time when I came to [this school], teachers in the special needs department were not making the interpretations in the classrooms, but since they started interpreting what you teach to those students, there have been great improvements, you are seeing that you are together in the same boat though they might not get everything but seeing them being in the same boat that's fine.

However, when the National Education Policy of 2013 was revised and adopted in 2016, it did not respond to the local needs of special needs learners with disabilities and albinism in particular. It copied international protocols without meaningful consultations with persons with albinism and mainstream teachers to address the issue in schools. Inclusive education has an excellent opportunity to offer pathways for epistemological integration of learners with disabilities within their learning environments in Malawi (de Souza, 2022).

The epistemological integration of learners with disabilities in Malawi is at stake. An example can be seen in the context of the abduction and killing of persons with albinism in Malawi. The malpractice advances the myths about people with albinism, including learners with this skin disorder. Theoretically, the situation overlooks the essence of the exosystem in which different education stakeholders need to make meaningful interactions in the absence of the learners for the betterment of the learners. Exosystem is a system in which interactions involve units that are not the core of analysis in the microsystem (Bronfenbrenner, 2005). Put differently, the exosystem involves those factors in which, in the case of the original tenets of Bronfenbrenner, the developing child is not involved, but the effects of the interactions funnel down to the child in the microsystem through the mesosystem (McLinden et al., 2018; Stofile et al., 2013). Thus, a reframed policy trajectory on inclusive education has to recognise that whatever the teachers practise in the absence of the learners funnels down to the learners.

Practice-informed policies and strategies

The analysis of interviews suggests there is an expressed need to formulate policies and strategies that are informed by practice. As Participant 1 indicated,

Mainstream teachers recognise that the policy says there is a need for inclusive education. The aim is to make all students or to make all children in Malawi get educated, regardless of the disabilities that they have. At least they want students to attend the basic education.

In essence, for Participant 3,

when it comes to tertiary education, many students do not have access. So, I have seen that the government of Malawi is now trying to introduce some subjects which might help those learners, for example, clothing and textiles, home economics, technical drawing, woodwork and metalwork. At least what the government wants is that when they finish the four years of secondary school, they should be independent when they go out there. Those students should be independent regardless of the disabilities.

It was further indicated by Participant 5 that

the policies help a lot because sometimes you take things for granted, you feel you are there to teach them, you do not mind them. However, when we are reminded by that policy to say there is a need for inclusive education when you go to class, you are alert, to say I have got these students whom I am supposed to attend to.

The National Education Policy of 2016 "recognizes the importance of inclusion of special needs education" (Malawi. Ministry of Education, 2016, p. iii). From what the policy proclaims and what the situation on the ground tells, it is very clear that the policy is not well informed, implemented, or evaluated. For example, mainstream teachers raised the issue of post-school skills as a key benefit for learners with disabilities in inclusive education. Nonetheless, the policy sees the aim of the education of learners with disabilities as being to acquire basic competencies epistemologically. With such a lack, it is not viable to come up with workable educational plans unless the policies recognise the influence that the macrosystems have on inclusive education. Bronfenbrenner (2005) designated a macrosystem as being composed of metaphysical and sociocultural factors that surround a developing child's physical, social, and cultural environment. Thus, a new policy framework on inclusive education has to take into account such factors as teacher education institutions, projects, programmes, policies, and curricula because these are the metaphysical and sociocultural factors that shape teacher practices for inclusivity.

Responsive changes to the mainstream education

Malawi has put in place policies that aim to provide equal educational opportunities to all learners (Chitiyo et al., 2019; de Souza, 2022). Participant 5 welcomed this development but observed that

[i]nclusive education is there, but when you try to follow it fully, you fail because of time. Why am I saying so? When you teach those students, you need to dedicate more time, so our policy says forty minutes for a lesson, but you will discover that if you want to use more inclusive education, you will not likely finish the syllabus. So, it needs more time.

Also, for Participant 3,

The workshops are supposed to be there to remind us because we forget, with time you forget. So maybe this year I am teaching the class which has got those students with disabilities, next year I am no longer teaching that class it means I will relax.

The evaluation of the National Education Policy of 2016 is assigned to the Ministry of Education itself. It is not very likely that such evaluation would present reviews critical to the opportunities inclusive education can offer to promote inclusive education in Malawi. Thus, its evaluation is likely to be limited, and its findings are irrelevant to inclusive education unless the time factor (the chronosystem) is considered in the policy formulation. Chronosystem is the "patterning of environmental events and transitions over the life course" (Bronfenbrenner, 2005, p. 43). This delineation entails that the chronosystem is a tracking system of what happens in the life of a developing child, at least according to what Bronfenbrenner initially propounded (Hayes & Bulat, 2017). However, national education objectives, Sustainable Development Goal 4 indicators, etc., fall within this system. All these units are interested in monitoring and evaluating what happens after a while concerning inclusive education. Therefore, a new policy trajectory towards inclusive education should be interested in what happens in inclusivity over time.

Model for Reframing Inclusive Education Policy

Theoretical model

Often, policymakers overlook the essence of theory in formulating national education policies. This situation has led to the development of policies primarily divorced from the context in which they are intended to be implemented (Done & Andrews, 2020). A theory is not just something academic but rather an onto-epistemological tool that helps policymakers to contextualise policy stipulations. Therefore, for developing a national inclusive education policy for Malawi or other southern African countries, it is imperative to employ a bio-ecological model that has much potential for developing inclusive education praxis, primarily because of its emphasis on interactions in a socio-cultural environment and transformative education. This theoretical model draws on the ideas of Bronfenbrenner's (2005) bioecological systems theory especially the Process-Person-Context-Time (PPCT) Model.

In the theoretical context of the Process-Person-Context-Time (PPCT) Model, a national inclusive education policy should reflect a systems approach to inclusive schooling. In a conduit of systems, one system should eventually help to achieve the goal of inclusive education regardless of the starting point. For example, the mesosystem helps to explain the intersectional relationships and interactions between the teachers' interpretations of the national education policies and the learning processes (Velez-Agosto et al., 2019). In other words, the teachers are entrusted with implementing policies and have to interact with several microsystems such as the parents, peers, and learners. This means that a national inclusive education policy should be able to reflect and encourage these system interactions, as shown in Figure 2 below.

Theoretically, the interaction of the teacher and the policy forms an exosystem. While the interactions between the teachers and the inclusive education policies are in the exosystem, the influencing factors funnel down to the microsystem, thus intersecting with the other systems (Swartz, 2015). Hence, the exosystem is essential in explaining influencing factors that affect learners from inclusive education policy. Thus, a national inclusive education policy should be formulated using a systems approach to contextualise the schooling systems. Fundamentally, a national inclusive education policy should be based on the systems approach because of its ability, over time, through the chronosystem, to acquire an understanding of the learning processes of the learners, especially those with disabilities, in inclusive schooling.

Methodological model

In light of interactive bio-ecological systems involved in inclusive education, I suggest that the policy formulation process would be more relevant if undertaken using the Agile Participatory Approach (APA) of project planning (see Whiteley et al., 2021). Through an APA methodological model, policymakers can work closely with education specialists and a multi-disciplinary core team set by a national ministry responsible for education. This approach embraces the bio-ecological systems theory that has the potential to reframe inclusive education policy. To make this approach more serving, the research components of the policy formulation process should follow the APA model using a Phenomenological-Exploratory Nested Case Study (PENCS) (see Silverman, 2020). In the PENCS method, participants should be selected across the country, reflecting factors such as gender, disability, and social status. Expert informants such as government policymakers, nongovernmental organisations, academics, and activists should be selected for their engagement with inclusive education issues. Exponential snowball sampling, convenience and purposive sampling (see Flick, 2018) should be used to locate individuals involved in inclusive education with connections being made through the experts involved in various issues related to inclusivity.

Evaluation model

Technically, evaluation of an inclusive education policy would need a mixed methods research model in which quantitative and qualitative data is collected (Mertens, 2019). The quantitative data would be used to measure the impact of the policy on fostering inclusivity. The qualitative data would be used to explain the successes, shortfalls, and prospects of the policy in the context of inclusive education. A quantitative questionnaire could be developed based on different sources of information, including reports. Qualitative data could be collected through a biographical approach (see van Marrewijk et al., 2021). The understanding is that some relative educational change would have occurred as far as inclusive education is concerned. Thus, the biographical approach is better placed to provide the data necessary from key stakeholders such as teachers, learners, specialists and parents to explain any educational changes. The biographical approach could include interviews, focus group discussions, observations, and life stories. Adopting this proposed evaluation model would ensure that evidence is solicited from the interactive systems involved in inclusive education which resonate with the bio-ecological policy trajectory reframing agenda.

Conclusion

Malawi, just like other Southern African countries, made promises to ensure the inclusion of learners with disabilities in mainstream education in response to international agreements. Like many countries, Malawi promised to educate all learners together regardless of disabilities and afford necessary support within mainstream education. In this study, I examined national policies, strategies, and practices for inclusive education in Malawi. Findings from the policy analysis point to a lack of theory-based framing of the policies to reflect interrelated and transformative systems necessary for advancing inclusivity in school practices. These findings also speak to the reporting of the United National Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) (2020) in Profiles Enhancing Education Reviews (PEER) on inclusion in education that reflects the inadequate ways in which inclusivity is represented in the PEER profile for Malawi and other southern African countries. Based on the analysis of interviews in this study, I recommend a theory-based reframing of the policy trajectory for inclusive education in Malawi that emphasises inclusive pedagogical proficiency. Potentially, the theory-based reframing can inform future policy formulation in southern Africa and reshape educational reporting such as the Global Education Monitoring (GEM) Report. Since government policies are benchmarks for formulating sector plans, southern African countries should develop comprehensive and inclusive education policies and well-informed, inclusive education strategies that are specific, attainable, and grounded in bio-ecological systems framing. Presently, the policy ignores the essence of mainstream teachers' pedagogical competencies and systems. Thus, it is challenging for Malawi to formulate and implement a national inclusive education policy to ensure the epistemological inclusion of learners with disabilities in mainstream schools.

References

African Union. (1990). African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child. African Union.

Baranauskiene, I., & Saveikiene, D. (2018). Pursuit of inclusive education: Inclusion of teachers in inclusive education. Society, Integration, Education: Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference, May 25-26, Vol. 2, 39-53. [ Links ]

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. [ Links ]

Bronfenbrenner, U. (2005). Making human beings human: Bioecologicalperspectives on human development. Sage.

Chilemba, E. M. (2013). The right to primary education for children with disabilities in Malawi: A diagnosis of the conceptual approach and implementation. The African Disability Rights Yearbook (pp. 3-26). Southern African Legal Information Institute. http://hdl.handle.net/10566/5031

Chimwaza, E. (2015). Challenges in implementation of inclusive education in Malawi: A case study of Montfort Special Needs Education College and selected primary schools in Blantyre [Master's Thesis, Diakonhjemment University College, Oslo]. [ Links ]

Chitiyo, M., Hughes, E. M., Chitiyo, G., Changara, D. M., Itimu-Phiri, A., Haihambo, C., Taukeni, S. G., & Dzenga, C. G. (2019). Exploring teachers' special and inclusive educational professional development needs in Malawi, Namibia and Zimbabwe. International Journal of Whole Schooling, 15(1), 28-49. [ Links ]

Danermark, B., & Bhaskar, R (2006). Metatheory, interdisciplinarity and disability research: A critical realist perspective. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 8(4), 278-297. [ Links ]

de Beco, G. (2018). The right to inclusive education: Why is there so much opposition to its implementation? International Journal of Law in Context, 14(3), 396-415. [ Links ]

de Souza, B. (2020). Assessing pedagogical practices Malawian mainstream secondary teachers interpret from national policies and strategies on inclusive education. Journal of Educational Studies, 19(2), 42-61. [ Links ]

de Souza, B. (2021). Back and forth: The journey of inclusive education in Africa. Academia Letters, Article 421.

de Souza, B. (in press). Policy responses to inclusive secondary education in Malawi. Rwandan Journal of Education, 16(1).

Done, E. J., & Andrews, M. J. (2020). How inclusion became exclusion: Policy, teachers and inclusive education. Journal of Education Policy, 35(4), 447-464. [ Links ]

Flick, U. (2018). An introduction to qualitative research (6th ed.). Sage.

Hart, M. A. (2010). Indigenous worldviews, knowledge, and research: The development of an indigenous research paradigm. Journal of Indigenous Voices in Social Work, 1(1), 116. [ Links ]

Hayes, A. M., & Bulat, J. (2017). Disabilities inclusive education systems and policies guide for low and middle- income countries. RTI Press Publication No. OP 0043-1707. RTI Press.

Kamchedzera, E., & Aubrey, C. (2010, September). Implementation of inclusion policy in Malawian Secondary Schools. Paper presented at BERA Annual Conference, University of Warwick, Coventry, UK.

Kamchedzera, E. T. (2010). Education of pupils with disabilities in Malawi's inclusive secondary schools: Policy, practice and experiences [Doctoral dissertation, University of Warwick, Coventry, UK]. [ Links ]

Lynch, P., Lund, P.M., & Massah, B. (2014). Identifying strategies to enhance the educational inclusion of visually impaired children with albinism in Malawi. International Journal of Educational Development, 39, 216-224. [ Links ]

Malawi. Ministry of Education, Science and Technology. (2016). National Education Policy. Ministry of Education, Science and Technology.

Malawi. Ministry of Education, Science and Technology. (2017). National Strategy on Inclusive Education. Ministry of Education, Science and Technology.

Malawi. Ministry of Justice. (2010). Malawian Child Care, Protection and Justice Act. Ministry of Justice.

Malawi. Ministry of Justice. (2012). Disability Act. Ministry of Justice.

Malawi. Ministry of Persons with Disabilities and the Elderly. (2006). National Policy on the Equalisation of Opportunities of Persons with Disabilities. Ministry of Persons with Disabilities and the Elderly.

Maree, K. (2016). First steps in research (2nd ed.). Van Schaik Publishers.

Mbewe, G., Kamchedzera, E., & Kunkwenzu, E. D. (2021). Exploring implementation of national special needs education policy guidelines in private secondary schools. IAFOR Journal of Education: Inclusive Education, 9(1), 95-111. [ Links ]

McLinden, M., Lynch, P., Soni, A., Artiles, A., Kholowa, F., Kamchedzera, E., Mbukwa, J., & Mankhwazi, M. (2018). Supporting children with disabilities in low- and middle-income countries: Promoting inclusive practice within community-based childcare centres in Malawi through a bioecological systems perspective. International Journal of Early Childhood, 50, 159-174. [ Links ]

Mertens, D. M. (2019). Research and evaluation in education and psychology: Integratingdiversity with quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods. Sage.

Mgomezulu, V. (2017). A review of the National Strategy on Inclusive Education (2017 2021) in Malawi. African Journal of Special and Inclusive Education, 2(1), 22-30. [ Links ]

Mitchell, D., & Sutherland, D. (2020). What really works in special and inclusive education: Using evidence-based teaching strategies (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Roth, P. A. (2019). Meaning and method in the social sciences: A case for methodological pluralism. Cornell University Press.

Silverman, D. (Ed.). (2020). Qualitative research. Sage.

Slee, R. (2018). Inclusive education isn't dead: It just smells funny. Routledge.

Sotuku, N., & Duku, S. (2015). Ethics in human sciences research. In C. Okeke & M. van Wyk (Eds.), Educational research: An African approach (pp. 112-130). Oxford University Press.

Stofile, S., Raymond, E., & Moletsane, M. (2013). Understanding barriers to learning. In C. F. Pienaar & E. B. Raymond (Eds.), Making inclusive education work in classrooms (pp. 18-36). Pearson.

Swartz, D. J. (2015). Supportive strategies for teachers and parents dealing with learners experiencing mild intellectual barriers to learning. [Unpublished doctoral thesis, Nelson Mandela University, Port Elizabeth, RSA]. [ Links ]

Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 5(45), 1471-2288. [ Links ]

United Nations. (1989). Convention on the Rights of the Child. UN.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2020). Global Education Monitoring Report 2020: Inclusion and Education: All Means All. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

van Marrewijk, A., Sankaran, S., Muller, R., & Drouin, N. (2021). A biographical research approach. In N. Drouin, S. Sankaran, A. van Marrewijk & R. Muller (Eds.), Megaproject Leaders (pp. 12-19). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Velez-Agosto, N., Soto-Crespo, J., Vizcarrondo-Oppenheimer, M., Vega-Molina, S. V., & Coll, C. G. (2017). Bronfenbrenner's bioecological theory revision: Moving culture from the macro into the micro. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(5), 900910. [ Links ]

Whiteley, A., Pollack, J., & Matous, P. (2021). The origins of agile and iterative methods. The Journal of Modern Project Management, 5(3), 21-29. [ Links ]

Received: 8 January 2022

Accepted: 1 September 2022