Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Journal of Education (University of KwaZulu-Natal)

versión On-line ISSN 2520-9868

versión impresa ISSN 0259-479X

Journal of Education no.86 Durban 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2520-9868/i86a08

ARTICLES

A social psychological perspective on schooling for migrant children: A case within a public secondary school in South Africa

Sarah Blessed-SayahI; Dominic GriffithsII; Ian MollIII

IWits School of Education, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. lessedsayah@yahoo.com; https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6882-2260

IIWits School of Education, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa ominic.griffiths@wits.ac.za; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6773-7184

IIIWits School of Education, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. n.moll@wits.ac.za; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2891-7163

ABSTRACT

The conceptualisation of schooling is often based on "ideal children" in "ideal situations." However, in determining the level of participation for children who are considered vulnerable in schooling, it is important to understand the lived experiences of these children. In this study, migrant children (particularly undocumented ones) in South Africa are the focus, and their lived experiences were considered through reflections from their parents and teachers. Data were collected using semi-structured interviews, and analysed using a constant comparative method of qualitative analysis within a grounded theory approach. The study found that challenges affecting migrant children's schooling include the lack of documentation, language barriers, issues of transition and adaptation (discrimination), and the inability to access further education. Strategies were identified to address the challenges, including schools liaising with the Department of Home Affairs, implementing cultural diversity programmes within the school, and through deliberate inclusive programmes.

Keywords: schooling, school participation, migrant children, South Africa, language barriers, cultural diversity

Introduction

A narrow, traditional conceptualisation of the word "schooling" is commonplace. Parents, teachers, schools, and governments are concerned about ensuring that all children fully participate in formal schooling, and different formal measures are used to determine this participation (see UNICEF & UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2016). Schooling is typically associated with "ideal children" in an "ideal world" and, according to Giroux (1984), traditionally, schooling is embedded

in the narrow concerns for effectiveness, behavioural objectives, and principles of learning that treat knowledge as something to be consumed and schools as merely instructional sites designed to pass onto students a "common" culture set of skills that will enable them to operate effectively in the wider society. (p. 36)

That view was endorsed by Kivela in 2018. However, there is no one-size-fits-all approach to participating in formal education at a particular age, and not all children are situated within the same environment. Rajan (2021) has argued that migrant children may be at risk of not being able to participate in the schooling process as a result of this traditional view. There is, therefore, a need to develop a broader definition of schooling because the opportunity to participate in schooling and learn is dependent on the situatedness of the child in a given context.

Little attention is paid to the social life, lived experiences, and school participation of the particular, often vulnerable, group of children (and their parents) who are migrants. In South Africa, migrant children's schooling goes beyond the conceptions that focus on traditional understanding, and extends to their surrounding circumstances, which may, in fact, impede opportunities for participating in school (see Buckland, 2011). To gain an understanding of this challenging, underlying context, participants in our study were teachers and parents of migrant children. A limitation of this small-scale study is that it did not include migrant children themselves. However, they will be included in future studies. In keeping with the more expansive meaning of schooling in this study, the social context of the child must be considered in explaining their levels of participation in school. This social context varies significantly for different children and includes the "situational, historical, geographical [and] social or cultural environment" (Van Dijk, 2007, p. 285).

In South Africa, migrant children's lived experiences need to be considered more often when determining their level of participation in school. Hemson (2011) argued that migrant children in South Africa are "a hopeful resource within [the] education [system]" (p. 82). This draws attention to the importance of gaining an understanding of their context and experiences to create a platform for ensuring that they are able to fully participate in schooling while they remain in the country. For the purpose of this study, the definition of "migrants" refers specifically to individuals who have moved across international borders to another country (International Organization for Migration, 2004). It does not include "internal migrants," that is, people who have migrated to a particular place from another area inside South Africa. As the number of migrants increases (Akanle et al., 2016; Crush & Williams, 2002; Crush & Williams, 2018; Mobius, 2017), so the number of children who move with migrant parents, or even on their own, into South Africa also increases (United Nations Children's Fund, 2020). These children need to receive an education and, even though they are migrants (illegal or not), Section 29 of the South African Bill of Rights (Republic of South Africa [RSA], 1996b) warrants everyone in the country the right to basic education. Furthermore, the South African Schools Act (RSA, 1996a) made it mandatory for every child to attend school from age seven years until age 15 or Grade 9, whichever occurs first. However, in contradiction to these two policies, the South African Immigration Act (RSA, 2002) stated that instruction by a learning institution to an "illegal foreigner" is an offence. This legal contradiction between the Schools Act and Immigration Act (RSA, 1996a; RSA, 2002) has been explored extensively in a study that focused on the barriers for a group of migrant children in South Africa (Crush & Tawodzera, 2011).

The legal contradiction imposes a particular burden on parents and educators. When parents are unsure of their legal entitlement to access to schooling for their children, this may result in adverse psychological consequences for those children. Although ultimately, it may be a matter for the courts (perhaps the South African Supreme Court because two legal statutes contradict one another), it seems clear that schools should provide access to migrant children, based on the primary education legislation. If parents get the wrong messaging from the school (see Crush & Tawodzera, 2011), they are likely to pass their ambivalence on to their children-and that is likely to affect the participation of those children at school.

It is difficult to measure how effectively migrant children and their parents can exercise their right to education, and this has significant implications for how schooling for these children is affected and understood. To evaluate the determinants of participation in schooling for migrant children, it is important to identify the challenges they face in that regard. However, in the South African context, there are few recent studies that have focused on the challenges faced by migrant children in relation to their experiences of schooling.

In the South African context, one study that highlighted the challenges faced by migrant children, and which have an impact on their schooling, was conducted by Hlatshwayo and Vally (2014). In their research, the authors found that xenophobia and discrimination against migrant children at schools hindered their full participation in schooling. Another challenge noted by Buckland (2011) is the language barrier, which prevents migrant children from participating in the schooling process in South Africa. Crush and Tawodzera (2014), in a related study, noted that the key challenge migrants face in accessing public healthcare facilities arises from being unable to produce proper documentation and consequently being denied treatment. However, various policy documents, including Section 27 of the South African Bill of Rights, stated that everyone has the right to access healthcare facilities (RSA, 1996b). This contradiction between policy and reality further aggravates the challenges faced by migrant children as related to their schooling in addition to their ability to access healthcare.

As indicated, there remains ongoing need to consider and investigate the challenges faced by migrant children in relation to schooling in South Africa. Thus, this study investigated the meaning and conceptualisation of schooling for migrant children in Krugersdorp, South Africa with the aim of understanding the situated, lived experiences of migrant children and the barriers they face in schooling through reflections from their parents and teachers. The study was informed, on one hand, by the sociocultural theory (also understood as neo-Vygotskian social constructivism) developed by Bruner (1996) and, on the other hand, by the phenomenological tradition dating back to Martin Heidegger (1927/2006) and developed by Jackson (1996). The former theory illuminated the social and cultural situatedness of meaning systems, and in that regard, Bruner wrote:

Meaning making involves situating encounters with the world in their cultural context to know "what they are about" . . . however much the individual may seem to operate on his or her own in carrying out the quest for meanings, nobody can do it unaided [without his or her] culture's symbolic systems. (1996, p. 3)

The latter theory provided an account of the lived experience of that situatedness, the being-in-the-world of the subject. Here, Heidegger, in Being and Time (1927/2006), developed the notion of being-in-the-world (p. 78) and the concept of worldhood (p. 91). Both these concepts argued that our existence is always already embedded in a world, and our being-in that world is experienced as a unitary, situated whole. We can take up relationships with the world and engage with the objects around us because of this state of already being-in-the-world and being shaped by its circumstances.

Together, the two theories provide the theoretical framework of our study and are purposefully used to gain an in-depth understanding of the challenges faced by migrant children-and which serve as barriers to their full participation in schooling. Socioculturalism can develop an account of the participation of a child in schooling based on their situatedness in a community context. This psychological theory attempts to link culturally based experiences with cognitive development. Phenomenology, according to Jackson (1996, p. 3), refers to the "study of experience. It is an attempt to describe human consciousness in its lived immediacy." This theory allows the lived experiences of migrant children, their worldhood, to be fully acknowledged and considered given that they find themselves in a world with preexisting expectations and challenges that can be detrimental to them in terms of schooling. The theories are used together to integrate cognitive expectances and the specific lived, social context of the migrant child to explain their participation in schooling (Figure 1).

The relevance of these theories to our study emerged from the need to understand the underlying contextual factors that have an impact on the level of participation in schooling for migrant children. A starting point we considered was the importance of the diverse contextual experiences the identified group of children face in alignment with a clear, in-depth understanding of their specific lived experiences in South Africa. As illustrated in Figure 1, a one-size-fits-all approach would not be sufficient in explaining and developing a well-rounded approach to explain schooling. In the South African context, the various challenges that migrant children face in relation to their participation in schooling need to be closely considered in order to better understand the psychological and social factors that affect them.

Research methodology

Our study used a qualitative research design, employing a case study approach with teachers and parents of migrant children at a particular public secondary school in Krugersdorp, South Africa. This design is suited to understanding the contextual conditions that are relevant to schooling (Yin, 2014). According to the 2001 South African population census, 83% of the migrant residents in the Krugersdorp area were from countries outside South Africa and only 17% from other parts of the country (Mogale City Local Municipality, 2016). Krugersdorp falls under the Mogale City municipality on the west of Johannesburg, roughly 34 kilometres from the city centre and has a good number of public schools, of which the research school is one. According to the Department of Basic Education (2019), the school is a Quintile 2 (no-fee paying) institution, and has about 1,327 students. This school was purposefully selected (Etikan et al., 2016) because it is located directly opposite a small community of shack houses that are occupied by migrants from neighbouring countries. A sample size of 13 participants (seven teachers and six parents of migrant children) from the school was selected using a convenience sampling strategy (Etikan et al., 2016). Migrant children were not directly included in the study, but will be in future studies. Nonetheless, a reflection of their lived experiences through their parents and teachers served as an eye-opener and provided some depth of understanding of their experiences. Data were collected using a semi-structured interview technique. The interviews took place on the premises of the school, in a private room for confidentiality.

Sociodemographic characteristics of study participants

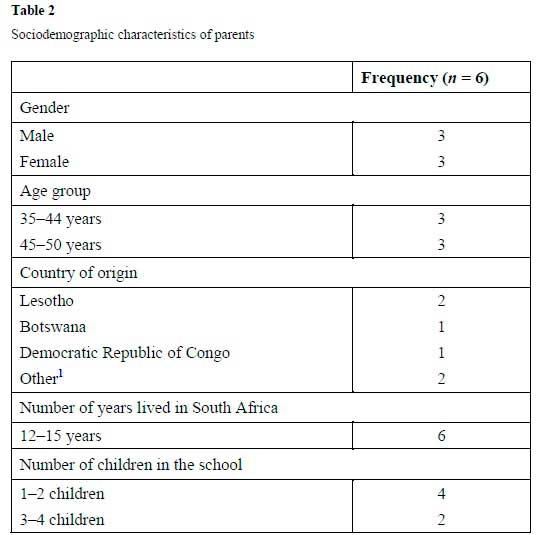

The study participants comprised two groups: teachers (n = 7) working with migrant children in the school, and parents (n = 6) of migrant children in school. The teachers' age range was 25 to 50 years; almost half of them had been teaching for between one to 10 years and some had taught for more than 21 years. All the teachers who participated indicated that they had consistently taught migrant children every school year. Table 1 provides a summary of the sociodemographic characteristics of teacher participants.

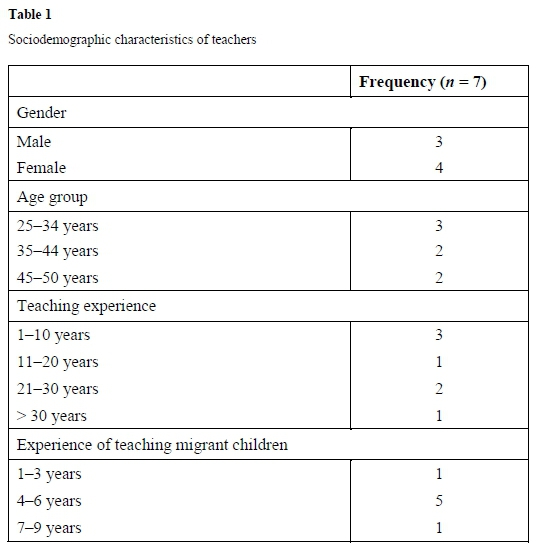

Six (n = 6) parents of migrant children in the school participated in the study. They were aged between 35 to 50 years, and half were women (see Table 2). Although most of the parents admitted that they had been in South Africa for over 10 years, some avoided talking about the topic. This subtle avoidance may have been because of the presumed stigma that accompanies being labelled a foreigner, and fear of being found out by the immigration authority. Their countries of origin included Lesotho, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Botswana.

Data analysis

Qualitative data were transcribed verbatim to retain meanings expressed by the participants. Standard coding procedures as developed within the grounded theory approach to social research (Corbin & Strauss, 2007; Glaser, 1965) were then applied to establish the beliefs and attitudes and, ultimately, the meaning systems of the participants. This is the constant comparative method of qualitative analysis and involves the iterative processes of open and axial coding. Firstly, in an open coding process, the raw data are grouped into categories in an inductive process. The rule guiding the development, populating, or discarding of categories is whether or not the data could offer possible insights into the research question (Geertz, 1973). The process moves between the raw data and the emerging categories until the latter are refined and the data are saturated. Secondly, in an axial coding process, the categories are embodied in more abstract theoretical principles. They must form "a stratified hierarchy of meaningful structures in terms of which . . . [the relevant behaviours] . . . are produced, perceived, and interpreted" (Geertz, 1973, p. 312). Thus, in this study, the transcripts were read and reread to provide a clear understanding of the data and identify code patterns as well as initial theme classification. Key emerging themes were identified and all the transcripts were revisited until saturation of data was reached (Birks & Mills, 2015; Given, 2016). The constant comparative method was important for a consistent and progressive building up of facts (Glaser & Strauss, 1967).

Findings

The study identified challenges affecting migrant children's schooling as well as strategies to address these challenges.

Challenges migrant children face in relation to schooling

This study reveals the key challenges, as reported by both groups of participants, which have an impact on migrant children's schooling. These include the lack of proper documentation, inability to access further education, language barriers, and issues of transition and adaptation (discrimination).

Lack of proper documentation

Both teachers and parents revealed that the lack of proper documentation is an underlying challenge, which compounds the other identified challenges that affect the schooling of migrant children. One parent stated:

If you don't have your permit, then you are not ready to study here. (Parent 5)

Although some participants were hesitant to admit that migrant children who attend the school have no proper documentation, others spoke openly about the challenge this presents and how it affects schooling:

I can tell you now that over 90% of the learners that do come, especially in the township schools like this, they don't have the whole paperwork . . . there's no documentation, which makes it even more difficult for us in the school. (Teacher 1)

This challenge is even more complex and evident when children have to register for external examinations such as the Grade 12 final examinations. At this point, most of the children are forced to remain in school or just quit:

The biggest problem that we are seeing with migrant children is that they do not have enough paperwork. So, when it comes to registering them [for the matric exam] it becomes an issue. (Teacher 4)

These migrant children are thus constantly faced with the reality of having incomplete legal documentation. A parent expressed this view by stating:

Especially when they have to write their finals, they don't have IDs-that's the problem for them. (Parent 2)

Furthermore, the teachers stated that there seems to be no clear way of overcoming this challenge because the laws that guide the country on immigration must be adhered to. One teacher explained despondently:

But then there's nothing that we can do, you know, it is policy . . . the schools are open for everyone . . . but now they want those papers to be present there and there's nothing we can do in terms of that. (Teacher 7)

Significantly, the inability to "do anything" relates here to structural constraints that prevent migrant children from being able to formally complete their schooling. The parents and teachers expressed a sense of powerlessness to help their children and learners progress through, and fully complete, schooling because of these structural, legal barriers. Crush and Tawodzera (2011) described the barriers as "gatekeeping" (p. 21) strategies to ensure migrant children are unable to access schools in South Africa. Thus, the initial challenge of access to any public South African school poses significant challenges to undocumented learners in terms of schooling.

Inability to access further education

The challenge of migrant children knowing that they will be unable to further their education to a higher level is another key factor that affects their full participation in schooling. One teacher noted:

It's useless for a child to come to a school . . . as a child who is a foreigner . . . they don't have the necessary documents; they do Grade 8, 9, 10, 11. When they get to Grade 11, they need to register for the matric exams. Now there's no [point] . . . I [migrant child] don't even have an ID. (Teacher 2)

This challenge, according to the teachers, is one that increases migrant children's lack of school preparedness. A teacher explained, using the example of a Grade 12 migrant child:

So, this Grade 12 learner is writing at the moment but there are no papers . . . there's no permit . . . there's nothing. What's going to happen to that girl next year? (Teacher 7)

The uncertainty, and often inability, to continue with and complete their schooling was highlighted as a reality for migrant children who lack the proper documentation to legally be in South Africa. Hence, although these children might attend schools in South Africa, knowing that they will be unable to formally complete their education is an ongoing challenge for their schooling.

Language barriers

Another major challenge faced by migrant children, which affects their schooling, is the language barrier. Many of the teachers interviewed raised this as a significant impediment to being prepared to participate in school, even at the high school level. The difficulty of this challenge is the sociological implication of lacking the "language" of a society and concomitantly, the accepted form of social, communicative behaviour (Fishman, 2012). This language barrier includes a lack of understanding of English as well as other widely spoken local languages in the area where the school is located. One teacher strongly stated:

Especially in English, because they don't know English . . . I think they know Portuguese or something like that which is difficult. At least, for maths, there's less English and they know maths but I think on other subjects where they have to elaborate in English, that's where it becomes a problem. (Teacher 5)

Another teacher reiterated:

Some of them cannot really encode English or speak English, okay, some of them are unable to even write in English. So, they come from maybe in a different country . . . and they don't know other languages, or they don't know English. (Teacher 3)

As is evident, a grasp of English is vital to being able to understand and participate in South African life. It is the lingua franca that allows someone to negotiate other kinds of social and cultural barriers. If a child is not able to understand even basic English, we must ask whether they can ever be adequately prepared for schooling in South Africa-particularly when it comes to reading and writing skills. This challenge is further compounded in that South Africa has 11 official languages, namely, Sepedi, Sesotho, Setswana, siSwati, Tshivenda, Xitsonga, isiNdebele, isiXhosa, isiZulu, English, and Afrikaans. Locals speak whichever language they identify with, and the migrant child must choose one of these "home" languages to learn at school (Broeder et al., 2002; Desai, 2016). As one teacher noted:

So, they will try to fit in and change their home language. Either they do Tswana, or they do Zulu; at the end of the day, they will fail that subject, because they will try to fit in with everyone else maybe in their class. (Teacher 3)

Another teacher mentioned:

The problem comes out when the child . . . is supposed to now choose the home language he or she is supposed to do . . . it becomes a problem now in reading and writing, constructing a sentence and such. (Teacher 7)

Parents also viewed this as a significant challenge. One parent said:

If your child is from outside the country, he cannot understand or speak the local language and that's a big problem because in school you have to read and write. How can you write a language that you don't know? (Parent 5)

These findings affirm how central language is to identity, learning, and belonging. A shared language is vital for cultural communication and the transfer of cultural values (Bonvillain, 2020). Thus, migrant children live within an already established cultural identity and must constantly negotiate the requirements of a foreign classroom space and language. Furthermore, given the importance of cultural integration, these children are disadvantaged because they are unable to fully interact with their social environment and community. This idea of being left out as a result of language has been explored by Cunningham and King (2018).

Issues of transition and adaptation (discrimination)

Another challenge expressed by the teachers and parents of migrant children is the issue of migrant children transitioning and adapting to the environment and schooling system. This challenge was explained as the children having difficulty in finding and having a sense of belonging. One parent said,

I think it's a problem of them trying to fit in with the other learners . . . I think somehow, they feel bad because they are not expressing themselves fully according to who they are. (Parent 3)

This inability to fully express oneself is part of a continual "negotiation of belonging" for migrant children (Devine, 2013, p. 290). This is further compounded by the xenophobic and derogatory name-calling that they are often subjected to. One teacher reported:

I think they have to constantly deal with other learners calling them foreigners or, calling them names. (Teacher 3)

Another parent stated:

I think one of the challenges they are facing most is discrimination. (Parent 3)

This abuse has serious psychological implications for these children. A teacher noted:

Some might commit suicide to end their lives. That is the fact! . . . I am worried. (Teacher 7)

Aside from what may be an unwelcoming, even hostile school environment, some of these children come from countries that are war-torn and politically unstable. As one parent said:

Some of them or many are coming from a trauma zone . . . they don't have any support . . . unfortunately, they came here to start the school like that . . . without counselling. (Parent 1)

This, sometimes dual, trauma profoundly affects these children, creating a stigmatised identity (Krzyzanowski & Wodak, 2008) characterised by a sense of shame that comes with being a foreigner in South Africa who is constantly reminded that they do not belong here. This sense of ongoing shame and, to use the Heideggerian term of homelessness, Unheimlichkeit, continues to influence migrants' experience in South Africa (Vandeyar, 2013). Thus, these phenomenological dimensions must also be considered when determining migrant children's participation in schooling.

Existing and suggested strategies to address the challenges

Despite the numerous challenges cited by parents and teachers that have an impact on schooling for these children, both teachers and parents highlighted only one strategy that is already in place to address some of the social and legal challenges they face. This strategy involves the school liaising with the South African Department of Home Affairs in order to assist migrant children who have incomplete, or no, legal documentation. The assistance is however, limited by what the law permits in relation to immigration. From the way some of the participants responded, this strategy seems much more perfunctory than anything else. In explaining what transpires, one teacher said:

Schools go to an extent of where we invite Home Affairs yearly. They come to school twice to assist the learners without documentation. . . . So, yes, the best that we can do is invite Home Affairs and invite parents to come and be there . . . see if they can find any amicable solution to whatever that is the challenge. (Teacher 1)

Although inviting the Department of Home Affairs seems to be the only existing strategy identified by the participants, teachers and parents were quick to make suggestions about what could be done to assist migrant children in participating in school, given their difficult context. One of the recommendations made by teachers and parents was that the school should incorporate and implement cultural diversity programmes within the school through the teaching of different cultures. One teacher proposed:

Diversity needs to be incorporated in schools, they need to teach learners about different cultures, race, languages, so that even the other learners, they understand that it's not just about me. It's not just about the language I speak, it's not just about how I do things, I also need to understand that there's other people that might be different from me, and there's absolutely nothing wrong with that! (Teacher 3)

Similarly, a parent suggested:

During the Heritage Month, what we could do when we have those is that each and every culture will come and perform their culture so that if they are more exposed to those activities, I think they will express themselves and maybe by seeing how the other learners receive it, it will also give them confidence. (Parent 3)

Another recommendation made by teachers was that the Gauteng Department of Education (GDE) should employ social workers and psychologists to be on school premises for the migrant children who are facing both social and psychological challenges. One teacher incessantly spoke about this need to employ professionals, saying:

I think we need social workers in school . . . I think it's very simple . . . we need social workers in school. So, we need psychologists, we need social workers who could deal with these kids because, honestly, in as much as teachers are trying, we are not trained to deal with the psych of a child honestly. So, you can only do so much, but they need professionals that they can speak. (Teacher 2)

In a bid to dispel the excuse of employing professionals being a costly exercise for the GDE, the teacher insisted:

It's very easy . . . I don't think it will cost them anything. If anything, it would try to fix the problems teachers are facing. I think they need help from the District and everyone else because, eish . . . there's a lot . . . because it's . . . it's not only about . . . with the teachers, their role is not only teaching . . . there's also admin so the school can only do so much. (Teacher 2)

The recommendation that parents should teach their children how to read and write in order to be able to participate fully in school was also put forward by the parent participants. Explaining this point, one parent said:

You can help them with reading. . . . You can teach them at home how to read, how to write. (Parent 2)

Another parent in agreement said:

We as parents we have to teach them, and we should have to monitor them all the time. (Parent 4)

Supporting this, yet another parent said that to teach migrant children how to read and write (especially in English), parents need to encourage and ensure that their children speak English at home. In the words of the parent:

Parents who are foreigners to speak English, if they've known how to speak English, at home and they allow the children to read English books and not speak local language at home because it can be like stopping them to improve the small that they are learning at school. (Parent 1)

Discussion

Our study investigated schooling for migrant children attending a public secondary school in Krugersdorp, South Africa. The aim was to discover what participation in schooling means to teachers and parents (in both the psychological and social development contexts) for these migrant children, and the associated challenges. The major challenges that emerged were lack of proper documentation, language barriers, inability to continue schooling, and issues of transition and adaptation (discrimination). A second set of key findings considered existing and suggested strategies to address the challenges faced by migrant children in relation to their participation in school. The themes that emerged interrogated the traditional explanation of what schooling is, and strongly support the importance of considering the specific context in which migrant children are situated. These points are discussed in turn.

Firstly, findings from this study show that the lack of proper documentation for migrant children was a key impediment to full participation in schooling. Both groups of participants spoke incessantly about this challenge as the one that amplified most of the other challenges that migrant children in this public school face. This finding has been corroborated by Crush and Tawodzera (2014) in the South African context, and also by Mitchell (2015). Crush and Tawodzera (2014) reported that all the migrants who participated in their study pointed out that enrolling children in school without paperwork was an arduous task in South Africa. Our study has thus confirmed the centrality of legal status in determining the participation of a migrant child in school in South Africa. It follows that, to explain schooling and the level of participation, the worldhood of the child and the already existing conditions that shape their circumstances must be considered. Evidently, in the South African context, an individual's state of being a learner is significantly dependent on their legal status. Determining participation in schooling, or explaining the concept, must therefore draw on the sociocultural conditions.

Secondly, the language barrier also emerged as a challenge that affects migrant children's schooling. Some participants said that children had the ability to grasp new languages faster than adult migrants in South Africa. However, most of the participants revealed that a lack of understanding of English (for migrants from non-English speaking countries) and local South African languages was an obstacle between migrants and their full participation in the schooling process. The fact that South Africa presents multilingual challenges compounds the barrier. This finding was also noted by Seker and Sirkeci (2015), Mitchell (2015), and Crush and Tawodzera (2014a). The challenge is further compounded by the need to speak and understand the language of learning and instruction, which may not be their first, second, or even third known language. The identified challenge of language is corroborated by the findings of Rodríguez-Izquierdo (2011). According to (Rodríguez-Izquierdo, 2011), the language barrier is a major challenge for migrant children, especially in terms of social integration and schooling. A more recent study (Rodríguez-Izquierdo & Darmody, 2019) found that the limitation of not fluently understanding the language of instruction can result in social exclusion. This relates to the theory of socioculturalism because, inasmuch as migrant children may want to hold onto their already learned languages because they are fluent and comfortable in them, they would be unable to integrate into the South African education system without learning the accepted cultural symbolic system, which in this case, is the language of instruction. Thus, a lack of language proficiency is a serious hindrance to schooling for migrant children.

A further challenge highlighted is the inability of migrant children to further their education, especially after high school. Many teachers reported that this challenge resulted in the unwillingness of migrant children to learn what is expected of them because it seemed there was no future in continuing with school in the current South African context. Related to, and supporting, these findings is work by Hernandez and Napierala (2012) who found that, despite the fact that migrant children in the USA may be resilient, about 25% of them were unable to complete high school. Also, the challenges of transition and adaptation, which include discrimination against migrant children by others, emerged from this study. A lack of a sense of belonging was identified by the participants. This challenge is one that is further compounded by issues of discrimination and xenophobia in South Africa and is supported by other studies on migration (Crush & Tawodzera, 2011, 2014; Landau et al., 2005; Spreen & Vally, 2012). The question remains whether, and to what extent, the migrant child's lived experience in the South African context in terms of limited opportunity for further education and discriminatory acts, limits and impedes their schooling. The challenge of discrimination against migrants is supported by Koehler and Schneider (2019) who noted that there is an urgent need to include these children in the education system and ensure they are not discriminated against or excluded.

In describing the theoretical implication of this study's findings, it is worth noting that experiences of schooling are constantly shaped by specific contextual factors (New et al., 2015). In our study, the context-based factors included, but were not limited to, the lack of proper documentation and language barriers for migrant children. Hence, in line with the theory of socioculturalism and phenomenology, the migrant children in the study cannot be expected to have the predetermined requirements of being able to participate in schooling without first considering their lived experiences. While socioculturalism permitted an understanding of the likelihood for cultural and educational experiences to significantly influence a child's participation in school, phenomenology allowed for an in-depth explanation of the specific experiences. Phenomenology provided the platform for the study to move beyond the formal criteria for determining the participation of migrant children in school to a more in-depth understanding of their lived experience (Bolton, 1979). The specific and context-based challenges that migrant children face are not separable from the environment in which they find themselves, and this difficult social reality deeply affects their schooling. Evidently, participation in the schooling process extends beyond the boundaries of psychological measurements into sociocultural contexts as well as the lived experience for migrant children in the South African context.

Our study also reports on existing and suggested strategies to address the challenges faced by migrant children in relation to their schooling. Most teachers noted that the only strategy currently in place is the school liaising with the Department of Home Affairs (DHA) to assist migrant children without complete documentation. Liaising with the DHA can create solutions that, in the long run, will allow migrant children to have reduced gaps in their education, access to, and the possibility of, formally completing schooling (see Dooley, 2017). Teachers and parents made other recommendations for addressing some of the identified challenges, which included the school governing body and management organising cultural programmes that promote greater cultural inclusion. This idea of cultural inclusion relates to the integration of migrant children into the education system. In support of this, Koehler and Schneider (2019) have argued that integrating migrant children into the education system as soon as possible is vital to ensure their integration into society.

Conclusion

Our study found that, to explain participation in the schooling process in the context of migrant children, it is necessary to consider context-specific challenges, which in this instance, are compounded by the lack of proper documentation. Both parents and teachers suggested that strategies including the introduction of cultural diversity within schools would aid the shift from the "ideal child with ideal competencies" explanation of schooling and expectations of participation to one that carefully considers the lived experiences of the migrant child. Although the South African government, through some of its policies, seems to allow for migrant children to access basic education, there is also a need to consider the other facets of the migrant child's life that consistently affect their schooling. These other facets are represented by embodied, lived experiences that are the realities of migrant children in South Africa.

Acknowledging that migrant children's lived experiences, as reflected through their parents and teachers, has a significant impact on their schooling and level of participation in the schooling process in the South African context is important for thinking critically about the meaning of schooling for them. The highlighted factors from this study show that the complexity of schooling cannot be tied to psychological measurements or ideal situations for ideal children. It is evident that the social world and embodied lived experiences play major roles in determining the nature of schooling for migrant children. If these other facets are not considered, gaps in the South African educational system will continue to exist, particularly hindering achievement of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 4-Quality Education, which highlights the basic right to education as well as the need for all children to attend and participate in school (https://en.unesco.org/gem-report/sdg-goal-4). Moreover, the contradictions that exist in the South African policies need to be addressed as a starting point for attending to the significant underlying factor impeding migrant children's schooling.

A major limitation of our study was that it only considered reflections from the parents and teachers of migrant children in order to highlight the challenges facing the children. The findings do not completely reflect migrant children's lived experiences from a participatory perspective. Excluding these children as participants ignores their perceptions of schooling in their lived context. Future research would need to focus on migrant children themselves (considering the ethical implications) as key participants to get a deeper understanding of the underlying factors that impede their participation in schooling.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge and thank the school and the participants involved in this study. We also thank all the reviewers for their helpful feedback.

References

Akanle, O., Alemu, A. E., & Adesina, J. O. (2016). The existentialities of Ethiopian and Nigerian migrants in South Africa. International Journal of African Renaissance Studies, 77(2), 139-158. https://doi.org/10.1080/18186874.2016.1249134 [ Links ]

Birks, M., & Mills, J. (2015). Grounded theory: A practical guide (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications.

Bolton, N. (1979). Phenomenology and education. British Journal of Educational Studies, 27(3), 245-258. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.1979.9973552 [ Links ]

Bonvillain, N. (2020). Language, culture, and communication: The meaning of messages (8th ed.). Rowman & Littlefield.

Broeder, P., Extra, G., & Maartens, J. (2002). Multilingualism in South Africa: With a focus on KwaZulu-Natal and metropolitan Durban (PRAESA, Occasional Papers No. 7). University of Cape Town.

Bruner, J. (1996). The culture of education. Havard University Press.

Buckland, S. (2011). From policy to practice: The challenges to educational access for non-nationals in South Africa. International Journal of Educational Development, 37(4), 367-373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2011.01.005 [ Links ]

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. L. (2007). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed.). SAGE.

Crush, J., & Tawodzera, G. (2011). Right to the classroom: Educational barriers for Zimbabweans in South Africa. Idasa. https://media.africaportal.org/documents/SAMP_-_Right_to_the_Classroom.pdf

Crush, J., & Tawodzera, G. (2014). Exclusion and Discrimination: Zimbabwean Migrant Children and South African Schools. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 75(4), 677-693. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-013-0283-7 [ Links ]

Crush, J., & Williams, V. (2002). Criminal tendencies: Immigrants and illegality in South Africa (Policy Brief No. 10). Southern African Migration Programme. https://scholars.wlu.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1067&context=samp

Crush, J., & Williams, V. (2018). Making up the numbers: Measuring "illegal immigration" to South Africa. Africa Portal and Southern Africa Migration Programme. https://www.africaportal.org/publications/making-numbers-measuring-illegal-immigration-south-africa/

Cunningham, U., & King, J. (2018). Language, ethnicity, and belonging for the children of migrants in New Zealand. SAGE Open, 8(2), 2158244018782571. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244018782571 [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education. (2019). 2018 Masterlist Gauteng. https://www.education.gov.za/Programmes/EMIS/EMISDownloads.aspx

Desai, Z. (2016). Learning through the medium of English in multilingual South Africa: Enabling or disabling learners from low income contexts? Comparative Education, 52(3), 343-358. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2016.1185259 [ Links ]

Devine, D. (2013). "Value"ing children differently? Migrant children in education. Children and Society, 27(4), 282-294. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12034 [ Links ]

Dooley, T. (2017). Education uprooted: For every migrant, refugee and displaced child, education. UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org/publications/files/UNICEF_Education_Uprooted.pdf

Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11 [ Links ]

Fishman, J. A. (2012). Readings in the sociology of language. Mouton Publishers.

Geertz, C. (1973). Thick description: The interpretation of cultures. Basic Books.

Giroux, H. A. (1984). Rethinking the language of schooling. Language Arts, 61(1), 33-40. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41405135 [ Links ]

Given, L. M. (2016). 100 questions (andanswers) about qualitative research. SAGE Publications.

Glaser, B. G. (1965). The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Social Problems, 12(4), 436-445. https://doi.org/10.2307/798843 [ Links ]

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. In B. G. Glaser & A. L. Strauss (Eds.), The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research (pp. 101-117). Aldine.

Heidegger, M. (2006). Being and time (J. Macquarrie & E. Robinson, Trans.). Blackwell. (Original work published 1927)

Hemson, C. (2011). Fresh grounds: African migrants in a South African primary school. Southern African Review of Education, 17, 65-85. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC99007 [ Links ]

Hernandez, D. J., & Napierala, J. S. (2012). Children in immigrant families: Essential to America's future (FCD Child and Youth Well-Being Index (CWI) Policy Brief). Foundation for Child Development. https://www.fcd-us.org/assets/2016/04/FINAL-Children-in-Immigrant-Families-2_1.pdf

Hlatshwayo, M., & Vally, S. (2014). Violence, resilience and solidarity: The right to education for child migrants in South Africa. School Psychology International, 35(3), 266-279. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034313511004 [ Links ]

International Organization for Migration. (2004). Glossary on migration. http://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/iml_1_en.pdf

Jackson, M. (1996). Things as they are: New directions inphenomological anthropology. Indiana University Press.

Kivela, A. (2018). Toward a modern concept of schooling: A case study on Hegel. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 50(1), 72-82. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2017.1336918 [ Links ]

Koehler, C., & Schneider, J. (2019). Young refugees in education: The particular challenges of school systems in Europe. Comparative Migration Studies, 7(28), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-019-0129-3 [ Links ]

Krzyzanowski, M., & Wodak, R. (2008). Multiple identities, migration and belonging: "Voices of migrants." In C. R. Caldas-Coulthard & R. Iedema (Eds.), Identity trouble: Critical discourse and contested identities (pp. 95-119). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230593329_6

Landau, L. B., Ramjathan-Keogh, K., & Singh, G. (2005). Xenophobia in South Africa and problems related to it (Forced Migration Working Paper Series #13). Forced Migration Studies Programme, University of the Witwatersrand. http://www.xenowatch.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Xenophobia_in_South_Africa_and_problems.pdf

Mitchell, C. (2015). In US schools, undocumented youths strive to adjust. Education Week, 34(29), 1-5. http://libertyeducationgroup.org/yahoo_site_admin/assets/docs/In_US_Schools_Undocumented_Students_Strive_to_Adjust.132152102.pdf [ Links ]

Mobius, M. (2017, March 16). South Africa: Key issues and challenges. Franklin Templeton. http://emergingmarkets.blog.franklintempleton.com/2017/03/16/south-africa-key-issues-and-challenges/

Mogale City Local Municipality. (2016). First annual review of the 5 years, 2016-2021. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwjY3PaM26f2AhVDY8AKHXVpDaQQFnoECB0QAQ&url=http%3A%2F%2Fmfma.treasury.gov.za%2FDocuments%2F01.%2520Integrated%2520Development%2520Plans%2F2016-17%2F02.%2520Local%2520Municipalities%2FGT481%2520Mogale%2520City%2FBinderl.pdf&usg=AOvVaw2dfqEpfVsr9QGdX5316Jp2

New, R., Guilfoyle, A., & Harman, B. (2015). Children's school readiness: The experiences of African refugee women in a supported playgroup. Australian Journal of Early Childhood, 40(1), 55-62. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworkspost2013/79/ [ Links ]

Rajan, V. (2021). The ontological crisis of schooling: Situating migrant childhoods and educational exclusion. Contemporary Education Dialogue, 18(1), 162-170. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973184920948364 [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa. (2002). Immigration Act: No. 13 of 2002. http://www.dha.gov.za/IMMIGRATION_ACT_2002_MAY2014.pdf

Republic of South Africa. (1996a). South African Schools Act, Act 84. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/act84of1996.pdf

Republic of South Africa. (1996b). Constitution of the Republic of South Africa No. 108, 1. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/images/a108-96.pdf

Rodríguez-Izquierdo, R. (2011). Discontinuidad cultural: Estudiantes inmigrantes y éxito académico. Aula Abierta, 39(1), 69-80. http://hdl.handle.net/11162/5197 [ Links ]

Rodríguez-Izquierdo, R. M., & Darmody, M. (2019). Policy and practice in language support for newly arrived migrant children in Ireland and Spain. British Journal of Educational Studies, 67(1), 41-57. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2017.1417973 [ Links ]

Çeker, B. D., & Sirkeci, I. (2015). Challenges for refugee children at school in eastern Turkey. Economics and Sociology, 8(4), 122-133. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-789X.2015/8-4/9 [ Links ]

Spreen, C. A., & Vally, S. (2012). Measuring the right to education for refugees: Possibilities and challenges. Southern African Review of Education, 18(2), 71-89. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC130316 [ Links ]

UNICEF & UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2016). Monitoring education participation: Framework for monitoring children and adolescents who are out of school or at risk of dropping out (Vol. 1). https://www.unicef.org/eca/media/2956/file/monitoring_education_participation.pdf

United Nations Children's Fund. (2020, January 8). UNICEF and the South African Red Cross partner to assist migirant children. https://www.unicef.org/southafrica/press-releases/unicef-and-south-african-red-cross-partner-assist-migrant-children

Vandeyar, S. (2013). Youthscapes: The politics of belonging for "Makwerekwere" youth in South African schools. Citizenship Studies, 17(3-4), 447-463. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2013.793079 [ Links ]

Van Dijk, T. (2007). Comments on context and conversation. In N. Fairclough, G. Cortese, & P. Ardizzone (Eds.), Discourse and contemporary social change (pp. 281-316). Peter Lang.

Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design methods (5th ed.). SAGE Publishers.

Received: 8 June 2021

Accepted: 8 December 2021

1 "Other" refers to parents who were not willing to disclose their countries of origin.