Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Education (University of KwaZulu-Natal)

versão On-line ISSN 2520-9868

versão impressa ISSN 0259-479X

Journal of Education no.85 Durban 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2520-9868/i85a09

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Measuring preservice teachers' ethnocentrism: A South African case study

Joyce WestI; Rinelle EvansII; Joyce JordaanIII

IDepartment of Early Childhood Education, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa joyce.west@up.ac.za https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3916-9754

IIDepartment of Humanities Education, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa rinelle.evans@up.ac.za https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3892-3479

IIIDepartment of Statistics, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa joyce.jordaan@up.ac.za https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5678-5853

ABSTRACT

High degrees of ethnocentrism indicate intolerance towards that which is not one's own. When displayed by teachers towards learners, such attitudes may have detrimental effects on learner performance and hinder transformation in South African classrooms. Using Vygotskian sociocultural theory of human learning as a theoretical framework, this quantitative case study reports on the outcome of the electronically administered Generalised Ethnocentrism survey that measured 1,164 preservice teachers' ethnocentrism at a private higher education institution. Apart from providing biographical data, respondents answered 22 statements on a 5-point Likert-type scale about their beliefs pertaining to their own and others' culture, customs, and values. Results showed that preservice teachers manifest varying degrees of ethnocentrism but that those who attended multicultural schools scored significantly lower on the ethnocentrism scale than those who attended mono-ethnic schools. Respondents in the last stretch of their studies also obtained lower scores on the GENE scale than first and second years. This would suggest that greater exposure to social diversity and interaction across cultures plays a fundamental role in shaping ethnocentric beliefs and attitudes. An unexpected finding was that the instrument did not provide similar results as found in several studies, thus creating misgivings about its applicability in a context in which a minority ethnic grouping no longer held power. Policy makers and teacher educators should consider interventions to create more explicit and purposeful opportunities for preservice teachers to gain multicultural exposure and develop cultural competence. Assisting prospective teachers to identify their own ethnocentrism and knowing how to counter the many prevailing ideologies that promote, however inadvertently, ethnocentrism would prepare them for the realities of their future classroom and equip them to act as agents of change.

Keywords: ethnicity, ethnocentrism, mono-ethnic, pre-service teacher, teacher education

Introduction

Given South Africa's apartheid history of segregation at all levels, discussions about issues of ethnicity in education remain uncomfortable yet pertinent. After the first democratic elections in 1994, followed the drafting of a just national constitution, key educational policies such as the South African Schools Act 108 of 1996, the Language-in-Education Policy of 1997, and the Language Policy for Higher Education of 2002, as well as the development of new school curricula, the time was ripe for transforming education by implementing social justice, encouraging tolerance, accepting diversity, and promoting multiculturalism and multilingualism.

However, bringing about change to the apartheid-fractured education system implied not only challenging inequities related to ethnicity in policies and curricula, but also endeavouring to equip teachers with adequate cultural competence in order to teach well in ethnically diverse classrooms. However, achieving this requires more than just introducing new ideologies that manifest in new policies, adopting a culturally relevant pedagogy, or designing new modules on multiculturalism. As Jansen (2011, p. vii) claimed, "[E]ducation must move beyond 'face equity' as an account of change and take on the hard knowledge questions."

We wondered whether a decade later the next generation of prospective white South African teachers had moved beyond "face equity." As part of a larger study, we thus asked to what degree are pre-service teachers studying at a mono-ethnic institution ethnocentric? It was of interest since after graduating, they would most likely not be appointed in similar mono-ethnic teaching contexts but would work, rather, in multicultural schools with a diverse learner profile. Although we measured only the degree of ethnocentrism and not its possible effect, our premise was that high degrees of ethnocentrism could possibly affect their attitude towards learners whose identity frameworks did not mirror theirs. If apparent, such prejudicial behaviour might impact negatively on the teaching and learning experience.

In this article, we report on a key outcome of our study conducted with a mono-ethnic preservice teacher population (n = 1,164) enrolled at a private higher education institution (PHEI) in South Africa. By mono-ethnic we mean preservice teachers who share a commonality in terms of race, language, culture, and religion. It is within this broad mono-ethnic context that we sought to establish to what degree these preservice teachers manifest ethnocentrism.

Literature review

The 21st century has been characterised by globalisation (Kamwangamalu, 2010; Marshall & Moore, 2018; Yiakoumetti, 2003), high mobility, fluid borders, seamless migration, and rapidly expanding human interconnectedness (Dewey, 2007; Hammack, 2015). This has not necessarily brought about an appreciation of cultural and linguistic pluralism but had led, rather, to an increase in ethnocentrism (see Ager, 2001; Eatwell, 2000, Van der Westhuizen, 2018). However, it is important to note that the construct of ethnocentrism carries both positive and negative connotations (Neuliep, 2002; Neuliep & McCroskey, 1997; Wrench et al., 2006). While ethnocentrism can be associated with national pride and even patriotism (Neuliep, 2002) as positive attitudinal indicators, it is generally associated with individuals who are "lacking acceptance of cultural diversity" (Hooghe, 2008, p. 11) based on the belief that their own ethnic group or culture is superior to others and that their own world view and values should be applied universally (Tajfel & Turner, 1982). In its extreme form, it manifests as racism and xenophobia. An increase in this type of ethnocentrism is exemplified in the anti-immigrant movements such as Brexit, the termination of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) policy in the United States along with the brutal racism that led to the Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests, the xenophobic attacks reported in Africa (especially in South Africa), the advocacy for ethnic nationalism, and the tendency to vote for extreme-right-wing political parties like Vlaams Belang in Belgium and, earlier this decade, UKIP in the United Kingdom. The most recent manifestation was the storming of the Capitol in January 2021 after Trump lost the US presidential election. To understand the complexities of identifying and measuring ethnocentrism we now go on to clarify the related concepts of ethnicity and ethnocentrism.

Defining ethnicity and ethnocentrism

Late 20th-century sociolinguistic definitions described ethnicity as "a group identity" that is derived from social constructs such as language, culture, race, and religion (Edwards, 1985, p. 6). Ager's description (2001) included physical attributes such as skin and hair colour as well as the shape of one's nose. More appropriate for the 21st century since individuals claim various identities and affiliations, ethnicity should instead be defined as "a lived and experienced sense of groupness that is more fluid, flexible and subjective than the biological and genetic considerations inherent in the concept of race" (Mesthrie, 2017, p. 102).

Brekhus (2008) and Mesthrie (2017) have argued that ethnic identity should not be viewed as fixed but, rather, as complex and multidimensional. Crump (2014) also stated that individuals enact and negate hybrid fluid identities making it hard to view ethnicity or ethnic identity as fixed. The neo-Simmelian position also criticises fixed notions of identity since, as this anti-positivist researcher argued over half a century ago, identity is a result of multiple overlapping affiliations such as religious, political, cultural, social, familial, and geographical intersections (Simmel, 1955). Fixed notions of identity are often also associated with national political agendas that lead to in-group and out-group distinctions based on ethnicity (Crump, 2014). However, viewing ethnic identity singularly as fluid belies the fact that ethnic differences and similarities can still be grouped into political, stable, and countable social constructs. Fluid notions of identity could also result in invisible heterogeneity, i.e., the failure to acknowledge diversity explicitly (Crump, 2014) and is associated with a colourblind ideology that promotes sameness and suppresses diversity by not acknowledging socially constructed (ethnic) differences (Thomas, 2018).

When the term ethnicity is associated with social constructs that categorise and distinguish individuals from one another, it can also be used to establish in- and out-groups based on a hierarchical categorisation related to notions of ethnocentrism.

The term ethnocentrism was coined by the Polish sociologist, Ludwig Gumplowicz, in 1883, and in 1906, according to Bizumic (2014), it was appropriated by William Graham Sumner. Ethnocentrism, with its roots in the Greek word for nation or people, is a sociological and psychological construct that influences the attitudes and beliefs of individuals about ethnicity (Gumplowicz, 1883; Mangnale et al., 2011); the two constructs are thus inseparable. Sumner (1906, p. 8) defined ethnocentrism as "self-centred scaling" or the tendency of individuals to identify strongly with their own culture by viewing it as central and by rejecting or reducing other cultures, languages, and/or religious traditions to a less prominent role (Mangnale et al., 2011; Sumner, 1906; Tajfel & Turner, 1982).

Ethnocentrism is often associated with ethnic nationalism (Ager, 2001) and what De Luca et al., (2018, p. 15) called "ethnic favouritism" that often manifests in the domination of, or preference for, a specific language or religion by a particular group. The foundation of nationalism lies in the sense of a collective or social identity and, in many cases, in the presence of an outsider, the "other" or "them", against whom the struggle takes place and "whose domination or potential threat stresses the necessity of a collective endeavour" (Ager, 2001, p. 14).

More recently, ethnocentrism has been found to correlate strongly with a lack of cultural intelligence (Harrison, 2012; Young et al., 2017), having intercultural communication apprehension (Wrench & McCroskey, 2003; Wrench et al., 2006), displaying religious fundamentalism (Altemeyer & Hunsberger, 2004; Wrench, et al., 2006), homonegativity (Wrench et al., 2006) and homophobia (Wrench & McCroskey, 2003).

Furthermore, ethnocentrism is evident in various societal conditions such as sectionalism, religious prejudice, racism, and even nationalism (Neuliep, 2002). It is generally also connected to distrust and authoritarian ideologies such as conservatism (Hooghe, 2008). Levinson (1950, p. 150) has argued that ethnocentrism is based

on a pervasive and rigid in-group out-group distinction; it involves stereotyped, negative imagery and hostile attitudes regarding out-groups, stereotyped positive imagery and submissive attitudes regarding in-groups, and a hierarchical, authoritarian view of group interaction in which in-groups are rightly dominant, out-groups subordinate.

An argument has also been made that ethnocentrism is a universal natural phenomenon that is subconscious (see Neuliep, 2002; Neuliep and McCroskey, 1997, Shimp and Sharma,1987; Sumner, 1906, Wrench et al., 2006). However, describing ethnocentrism as universal might well overlook the fact that although it is a widespread phenomenon, it has various localised manifestations (Tajfel & Turner,1982).

Louw et al. (2014), explained that human development is a cultural process based on the impact that cultural values, norms, and lifestyles can have on a person's attitudes, beliefs, and personal development. Yusof et al., (2014) suggested that prolonged exposure to an exclusive, mono-ethnic environment may be one of the reasons why some individuals manifest a high degree of ethnocentrism, and whether one could argue that exposure to other ethnicities (races, cultures, and languages) could decrease one's degrees of ethnocentrism while no such exposure could inflate them. We thus chose Vygotsky's sociocultural theory (1978) as the theoretical framework for this study. Since human development can be viewed as a cultural process, it is possible that individuals' ethnocentrism can increase or decrease based on their social experiences with other cultures, the interaction between their biological and sociocultural changes, and their environmental exposure, such as, for example, their schooling context and home environment (Louw et al., 2014; Vygotsky, 1978.) The latter also argued that human development is a social occurrence, not an individual one and this notion aligns with the general premises of ethnocentrism (see Gibbon 2015). Ager's (2001) research resonates with the tenets of Vygotsky's social cultural theory and strengthens the argument of Yusof et al. (2014) by claiming that individual attitudes and beliefs are socially conditioned and therefore usually shared within a particular community. Therefore, in a mono-ethnic community, individuals' attitudes and beliefs about others' language, culture, and race may well be influenced. Tajfel and Turner's (1982) argument that the reasons leading to an increase or decrease in ethnocentrism or even perhaps its disappearance should be considered. We were thus interested in measuring a sample of pre-service teachers' degree of ethnocentrism since we surmised that their earlier and current education environments were largely mono-ethnic.

Teachers and ethnocentrism

The damaging effects of ethnocentrism are, however, not limited to politics; they are also evident in education. Various national and international studies (e.g., Cain, 2012; Fittel, 2008; Incecay, 2011; Johnson, 1992, 1994; Karabenick & Noda, 2004; Kazempour & Sadler, 2015; Knudson, 1998; Lombard, 2017; Nespor, 1987; Vibulphol, 2004; Xu, 2012) found that teachers' beliefs about ethnicity have a significant impact on their classroom practices and learner performance yet, as Kazempour and Sadler (2015) argued, studies that focus on preservice teachers' convictions related to ethnicity and their ethnocentrism remain largely unaddressed. It thus becomes imperative to investigate ethnocentrism in teacher education if preservice programmes are to deliver teachers who appreciate cultural and linguistic pluralism in their classrooms. However, exhibiting high degrees of ethnocentrism publicly is viewed most often as socially unacceptable (Roy, 2006) so, ethnocentrism is, therefore, complex to investigate and difficult to measure.

As promulgated in the National Qualifications Framework (NQF) Act 67 (Republic of South Africa (RSA), 2008, teacher education in South Africa is guided by the Minimum Requirements of Teacher Education Qualifications (MRTEQ) policy (Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET), 2015). According to the MRTEQ policy, all teacher education programmes are required to prepare preservice teachers to become socially just teachers by including "situational and contextual elements that assist teachers in developing competencies that enable them to deal with diversity and transformation" (DHET, 2015, pp. 8-9). However, even though policies may advocate for such attributes in teachers, Anderson (2014, n.p.) asked, "How many teachers walk into their classrooms on their first day of teaching with the necessary skills in their toolbox to navigate diversity and aspects of ethnicity?"

The challenges awaiting novice teachers are exacerbated when they are not equipped to recognise ethnic diversity and further complicated when their ethnic profile differs from that of their learners (Anderson, 2014). If preservice teachers lack "acceptance of cultural diversity" (Hooghe, 2008, p. 11) and consider their own ethnic group superior to others (see Mangnale et al., 2011; Sumner, 1906) such attitudes and beliefs may drive classroom practices (Johnson, 1992, 1994; Lombard, 2017; Nespor, 1987; Pajares, 1992; Richardson, 1996; Vibulphol, 2004), and become detrimental to learners' performance and academic achievement (le Roux, 2016; Marx, 2004; Xu, 2012). It is thus pertinent that preservice teachers understand how their beliefs about so-called others and their own ethnocentrism might manifest in their classroom practices (le Roux, 2016) and create dissonance in an environment that ought to be conducive to learning. As le Roux (2016, p. 7) and Marx (2004, p. 40) have stated, the most "loving teachers" can be racist and ethnocentric and have detrimental effects on the learners they teach.

In a South African study by Vandeyar (2008), the participants failed to recognise the opportunities that a multicultural and multilingual class offers in relation to cultivating a generation of learners committed to the values of democracy and social justice. Another study, conducted in the United Kingdom, found that preservice teachers are ill-prepared for the multilingual and multicultural classroom since their undergraduate programme prepared them only for a "monoculture, a mythical, culturally homogeneous aggregation of students' ' (Bullock, 1998, p. 1025). Various studies (see Khunou et al., 2019; le Roux, 2016; Reygan, 2019; Roux and Becker, 2016; Vandeyar, 2008) have also reported on teachers' and preservice teachers' prejudices, their ignorance about diversity, and their ineptitude or unwillingness to address issues of diversity in the South African education system. In another study by Vandeyar and Vandeyar (2017) South African preservice teachers were quick to make distinctions between them and us when they were working with immigrant students. From their study, ethnocentrism in teacher education was evident since the preservice teachers clearly attempted to exclude immigrant students on an academic and social level, based on aspects of ethnicity. One can therefore understand why Jansen (2011, p. vii) stressed the need for researching the "epistemological and ideological character" of South African preservice teachers to counter this reluctance to change and, instead, embrace diversity.

If preservice teachers are to become active role players in addressing the detrimental effects of ethnocentrism in education, they need to be taught to interrogate their own worldviews and to reflect critically on their degree of ethnocentrism in order to appreciate the diverse worldviews of their learners and make informed decisions about their own classroom practices (Boutte et al., 2011; le Roux, 2016).

Contextualising the study

Higher education remains central to the project of transformation in South Africa (Council of Higher Education, (CHE), 2016). Currently persons wishing to become teachers have the option of enrolling at either public universities or private higher education institutions (PHEIs), a favoured choice because students most often gain their qualifications through distance mode. Legislation exists to ensure that higher education in South African operates within the Constitution (Act No. 108 of 1996). (See, for example, the registration and accreditation requirements of the DHET, the Higher Education Quality Council (HEQC), CHE, a statutory body responsible for promoting and overseeing quality assurance in higher education, the South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA) and the NQF. The registration of PHEIs takes place in accordance with the requirements of the Higher Education Act (No. 101 of 1997) and the Regulations for the Registration of PHEIs, 2016. PHEIs have to adhere to Section 9(3 and 4) in the Regulations for the Registration of Private HEIs (2016) in the Higher Education Act (Act No. 101 of 1997) and Section 29(3) of the Constitution (RSA, 1996, p. 12), giving everyone "the right to establish and maintain, at their own expense, independent educational institutions that do not discriminate on the basis of race; are registered with the state; and maintain standards that are not inferior to standards at comparable public educational institutions." Section 9(3) furthermore provides more detail by stating clearly that "the state may not unfairly discriminate directly or indirectly against anyone on one or more grounds, including race, gender, sex, pregnancy, marital status, ethnic or social origin, colour, sexual orientation, age, disability, religion, conscience, belief, culture, language and birth" (RSA, 1996, p. 6). Once registered, PHEIs must offer equitable quality education to ensure that students obtain NQF-aligned qualifications. The CHE regulations with regard to PHEI's accreditation of qualifications further curb existing mistrust surrounding PHEIs and perceptions that such institutions deliver programmes of "questionable quality" (CHE, 2016).

Although various studies have been done on teachers' beliefs such as learner expectations and best teaching practices, Fittel (2008), Incecay (2011), and Kazempour and Sadler (2015) have all indicated that studies focusing on preservice teachers' beliefs about diversity in the classroom remain largely unaddressed especially in South Africa. Since various national and international studies (e.g., Cain, 2012; Johnson, 1992, 1994; Karabenick & Noda, 2004; Kazempour & Sadler, 2015; Knudson, 1998; Lombard, 2017; Nespor, 1987; Vibulphol, 2004; Xu, 2012) have found that teachers' beliefs about teaching practices have a significant impact on their classroom practices and on learner performance, it has become imperative to investigate their beliefs about ethnicity in the classroom since, if left unchecked,

ethnocentrism may become a threat to future teachers' good classroom practice.

Methodology

We conducted the research at a PHEI in South Africa that offers various Bachelor of Education (B.Ed) degrees through a mostly distance mode of delivery. At the time of the study, this PHEI was considered mono-ethnic in terms of its student composition since 99% of the preservice teachers were white and shared the same mother-tongue. The pertinent administrative records also show homogeneity in terms of gender since 89% of them identified as female. Upon enrolment, a student has to endorse the institutional Christian vision and mission statements.

The mono-ethnic nature of the PHEI is permitted by a law that allows PHEIs to establish their own policies as long as no form of unfair discrimination takes place. For example, Section 29(2) of the Bill of Rights (RSA, 1997) protects South Africans' right to receive education in the language of their choice, Section 6 of the Constitution (Act 108 of 1996) prioritises the right of all languages to be treated equitably, and Section 30 states that "[e]veryone has the right to use the language and to participate in the cultural life of their choice" (RSA, 1997, p. 13). Furthermore, Section 31 states that every person has the right and freedom to belong to and enjoy the cultural, religious, or linguistic community of his or her choice.

With careful consideration of the interwoven aspects of ethnicity and in recognition of the fluidity of ethnic identities in the 21st century, we measured the degree of ethnocentrism using the Generalised Ethnocentrism (GENE) scale of preservice teachers studying in a monoethnic environment.

Method

This case study drew on a single data set of 1,164 preservice teachers studying at a purposefully chosen PHEI in South Africa making it an institutional case study i.e., a singular study within a particular setting (see Trochim et al., 2016). A positivist paradigm and a quantitative research design served this study best since empirical as well as biographical data was collected deductively through an objective measurement-a fixed Likert-scale survey that measures ethnocentrism (see Grosser, 2016; Lombard and Klopper, 2015). This was a non-experimental study since it was descriptive in nature and investigated preservice teachers' degree of ethnocentrism.

Sample

Along with the research site being purposefully chosen, the homogenous sample of preservice teachers was conveniently selected through a non-random selection process since all the preservice teachers enrolled in 2019 were invited to participate in the study. The homogeneous sample was "typical" (Babbie et al., 2014, p. 281; Trochim et al. 2016, p. 87) of the PHEI population strengthening the case study design (see Babbie et al., 2014) since the results were largely representative of the enrolled student population of the PHEI at the time. However, in line with the points made by Trochim et al. (2016), the non-probability sampling technique did affect the external validity of the study.

Students were informed of the purpose of the study via the PHEI's online learning platform. They were told that their participation would be anonymous and voluntary, and that they were required to complete an online Google Forms questionnaire. No incentives were offered. Institutional ethical clearance for this study was received (HU 18 08 01) and it was also consented to by the Research Board of the PHEI.

The population consisted of 1,200 students of whom 1,164 participated in the online questionnaire. More than half (58%) of the sample was made up of first-year students. Second-year students accounted for 25%, third year, 13%, and students enrolled for the fourth, fifth, or sixth year constituted 4% of the sample. Although a regular B.Ed. degree is generally completed in four years, students at this PHEI are studying through a blended mode that allows them a longer completion time. The third-year preservice teachers who participated were collapsed with the other senior students to create a set accounting for 17% of the data set.

The majority of the sample self-identified as female (86%) and 14% as male. The average age of the respondents was 21 years and 6 months with a standard deviation of 5.2 years. The minimum age was 18 and the maximum age was 56. The sample consisted of 99% white and 92.5% of Afrikaans mother-tongue speakers with 94% having English as their second strongest language. Of the sample, 96% received primary education in Afrikaans, and 94% high school education in this language. Many of these students were appointed as teaching assistants and would have been responsible for a fair amount of instruction each week yet only 63% used Afrikaans as the medium of instruction. A test for equal proportions indicated a statistically significant difference (p <.001) between the respondents who used Afrikaans as the medium of instruction and those who did not. However, although the equal proportions test result was statistically significant, an effect size of 0.3 showed only moderate practical significance (see Field, 2018). The heterogeneity evident could therefore have occurred by chance.

Biographical data showed that 61% attended multicultural primary schools and 56% attended multicultural high schools. An equal proportions test indicated a statistically significant difference (p <.001 level, an effect size of 0.23) between the respondents who attended multicultural primary schools and those who attended mono-ethnic primary schools. Another statistically significant difference (p-value, 0.001 level, an effect size of 0.11) existed between the respondents who attended multicultural high schools and those who had been in mono-ethnic high schools. From the descriptive demographical statistics, it was evident that the sample was homogenous with regard to race, gender, and language. Given the interrelated nature of the demographics, the sample is representative of a minority ethnic group in South Africa.

Data collection instruments

Two instruments were used-an online questionnaire consisting of 13 biographical questions and the GENE survey of 22 items. The GENE survey, also known as the 2002 Generalised Ethnocentrism scale, is a self-reporting instrument that was developed by Neuliep and McCroskey in 1997 and revised by Neuliep in 2002. The original GENE scale consisted of 24 items, but after extensive factor analysis, these were reduced to 22 (Neuliep, 2002). The GENE scale is supposedly unidimensional; Neuliep (2002) reported that the 15 items consistently form one factor when subjected to factor analysis. The revised GENE scale uses a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from (1) "strongly disagree" to (5) "strongly agree." Only 15 items are used in the scoring of ethnocentrism; the remaining seven items are used as distractors and three items should be reverse-scored before the calculation takes place (see Neuliep, 2002; Neuliep & McCroskey, 1997). The items of the GENE scale measure the respondent's beliefs about the validity of others' ethnicity, culture, customs, values, and lifestyles as well as their own.

The GENE scale has been used to predict various attitudes and behaviours. For example, high degrees of ethnocentrism correlated with negative attitudes and expectations (Amos & McCroskey, 1999), poor cultural intelligence (Harrison, 2012; Young et al., 2017), intercultural communication apprehension (Wrench & McCroskey, 2003; Wrench et al., 2006), religious fundamentalism (Altemeyer & Hunsberger, 2004; Wrench et al., 2006), homonegativity (Wrench et al., 2006) and homophobia (Wrench & McCroskey, 2003). Neuliep (2002) also claimed that this scale possesses construct validity since it can be associated with positive attributes such as loyalty and patriotism.

Furthermore, despite a careful search, we could find no definitive norms on the GENE scale although a mean score of around 30 has been found in earlier studies (Amos & McCroskey, 1999; Neuliep, 2002; Neuliep & McCroskey, 1997; Wrench & McCroskey, 2003). In a study by McCroskey (2003), women scored significantly lower (mean score of 30.6) than men (mean of 35.5), indicating that a score between 30 and 35.5 seems to be the norm. The reason why men scored higher than women was unclear and was not discussed. These studies therefore provide a frame of reference that was used to interpret the respondents' results.

Reliability and validity of the instrument

The GENE scale items (See Addendum A) were not translated into Afrikaans since this could have affected the reliability and validity of the instrument. All the respondents were believed to be bilingual and would therefore have been able to complete the survey in English. This assumption was based on the bilingual enrolment requirements of the PHEI as well as English being the additional language school-leavers are compelled to take as an exit subject. However, synonyms were added in brackets for low-frequency words. For example, item 14 read, "Lifestyles in other cultures are not as valid (correct) as those in my culture." Similarly, in item 17, "I see people who are similar to me as virtuous, the final word was glossed as "good."

According to Neuliep (2002, p. 205), the GENE survey "can be administered to any person regardless of his or her cultural background." The survey has been used and tested internationally numerous times by researchers such as Dong et al. (2008), Neuliep et al. (2001) and Wrench et al. (2006), with all their studies reporting a reliability coefficient above 0.88. Studies conducted over 20 years ago reported the reliability of the GENE scale to be between 0.72 and 0.92, thus indicating its reliability. See Table 1 for 14 studies in chronological order and their reported Cronbach's alphas on the GENE scale that demonstrate its reliability.

Data analysis

The data collected from the survey was first exported from Google Forms and then analysed using IBM SPSS statistics software. There was no missing data. However, an anomaly appeared in the response rate of 97% and in similarities in the biographical section. Therefore, it is possible that there were duplicates in the data set, but because of the anonymous nature of the data, this was impossible to confirm. The high response rate is, therefore, a limitation of the study's findings.

We did several descriptive and inferential statistical analyses and performed exploratory factor analyses (EFA). Furthermore, we performed a test of normality and, since the sample size was larger than 50, we also conducted the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test that indicated that the data did not come from a normal distribution (p-value < 0.001). However, the central limit theorem holds, implying that the means have an approximately normal distribution.

Results

The average GENE score (degree of ethnocentrism) was 31.53 (SD = 8.62), with a minimum score of 15 and a maximum of 65. See Figure 1 for the equal and symmetrical distribution of the GENE scores with an interquartile range of 12 (25, 31, 37).

Reliability analysis was carried out on the GENE scale that showed that the GENE survey reached good reliability (α = 0.86) (see Field, 2018) that increases the trustworthiness of the study's findings. After extraction, all 15 items appeared to be worthy of retention, resulting in a decrease in the alpha if deleted. See Table 2 for the descriptive statistics of each of the 15 items as well as the reliability estimates.

The reliability and validity of the GENE survey were further investigated by EFA using principal axis factoring and Oblimin with Kaiser Normalisation rotation with eigenvalues greater than one. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy yielded a value of 0.893 (105 df) with a significant Bartlett's test of sphericity (p < 0. 001), indicating that the sample size (1164) was large enough to assess the factor structure and that the data was sufficient for the factor analysis (see Hair et al., 2010; Pallant, 2007; Tabachnick and Fidell, 2007).

From the EFA, 15 factors were identifiable before extraction; after extraction, three factors with an eigenvalue greater than 1 remained with an overall cumulative percentage of 43.219. The low cumulative percentage may be ascribed to the GENE survey having been designed for and in the context of North America and that contextual factors in South Africa may have affected the degree of variance.

The eigenvalues show that the first factor explains 32% of the variance, with an eigenvalue of 5.332. The second factor shows 8% and the third factor shows 3.19% of the variance. A further investigation into the factors was therefore important. See Table 3 for the three different factors through a pattern matrix and Figure 2 that depicts the GENE survey's factor loadings on a scree plot.

The pattern matrix in Table 3 and the scree plot in Figure 2 suggest that the GENE survey is not unidimensional and that there are three factor loadings involved.

Further data analysis included tests for equality and one-way ANOVAs. The Levene's test for equality of variances and the t-test for equality of means reported a statistically significant difference (p-value = 0.001) between the mean GENE score of those respondents who attended multicultural primary schools and those who attended mono-ethnic primary schools (t-value = 3.028; df = 1162). The mean GENE score of the respondents in multicultural primary schools was lower than those who did not attend multicultural primary schools (30.5 vs 32.2). Therefore, it can be inferred that the preservice teachers who attended multicultural primary schools had lower degrees of ethnocentrism. However, an effect size of 0.09 shows that the effect is small (see Field, 2018).

The Levene's test for equality of variances and the t-test for equality of means also reported a statistically significant difference (p-value = 0.001) between the mean GENE score of the respondents who attended multicultural high schools and those who attended mono-ethnic high schools (t-value = 3.236; df = 1162). The mean GENE score of the respondents who were in multicultural high schools was lower than those who did not attend multicultural high schools (30.8 vs 32.4). We therefore inferred that the respondents who attended multicultural high schools had lower degrees of ethnocentrism. However, an effect size of 0.09, following Field (2018) shows that the effect is small. From the findings of the Levene's test for equality of variances and the t-test for equality of means, it is possible to infer that the preservice teachers who lacked social and environmental exposure to multicultural schooling environments (i.e., at primary and high school) could be associated with higher degrees of ethnocentrism.

A one-way ANOVA was also performed to determine whether there was a statistically significant difference between the GENE score (degrees of ethnocentrism) of the respondents and their year of registration. The one-way ANOVA shows moderate evidence of a difference across the respondents' years of registration (p-value = 0.067) (see Field, 2018). Even though the evidence is not strong, further testing was done to investigate where possible differences might have occurred. A statistically significant difference was found between the second-year group and the third- to sixth-year group (p <0.001). The third- to sixth-year respondents (M = 31.22; SD = 8.92) had lower degrees of ethnocentrism than the second-year respondents (mean GENE score = 32.54). However, in line with Field (2018), an effect size of 0.06 shows that this is small. A one-way ANOVA showed no evidence of a difference across the respondents' different age groups (p-value = 0.665) and different medium of instruction groups (p-value = 0.621).

Discussion of results

We endeavoured to measure preservice teachers' degree of ethnocentrism and its association with other variables in a mono-ethnic environment. The variables included the nature (multicultural vs mono ethnic) of the preservice teachers' schooling environment, their year of registration, and their age.

The first finding indicated varying degrees of ethnocentrism. The lowest GENE score was 15 and the highest was 65 (a range of 50). The average score of 31.53 aligns with the average GENE scores reported in the literature that averages between 30 and 50 (Neuliep, 2002). Although there are no established norms with regard to ethnocentrism, Neuliep (2002) argued that a score above 50 indicates a high degree of ethnocentrism and any score below 50 is regarded as indicative of a lower degree of ethnocentrism. However, while the preservice teachers had an average GENE score of 31.53, the wide range of 50 shows that the sample had varying degrees of ethnocentrism. Preservice teachers with high degrees of ethnocentrism may struggle to teach effectively in multicultural classrooms resulting in instructional and affective dissonance.

It was evident that item B2, "My culture should be the role model for other cultures", scored the highest (2.68) and item B9 "I respect the values and customs of other cultures", scored the lowest (1.48). Strongly agreeing with these statements could be viewed as having high degrees of ethnocentrism since it indicates how strongly one's identity is embedded within one's own culture. It also suggests a belief that cultural standards can be applied universally (see Hooghe, 2008; Tajfel and Turner, 1982) thus suggesting cultural superiority. Item B9, with which the preservice teachers mostly disagreed, is about respecting other cultures and their customs. Participants' disagreement with such a statement suggests the likelihood of high degrees of ethnocentrism since this could be perceived as being intolerant and disrespectful towards cultures other than their own.

Second, a statistically significant difference between the preservice teachers' GENE score (degree of ethnocentrism) and the nature of their primary and high school environment (mono-ethnic vs multicultural) was evident. This finding aligns with Vygotsky's sociocultural theory (1978) that proposes that one's environment plays an influential role in one's development of attitudes and beliefs about others. It is with caution that we suggest that preservice teachers' schooling environments have influenced their degree of ethnocentrism and that this section of the sample's lack of exposure to socially and culturally diverse contexts may be the reason for higher degrees of ethnocentrism.

A third finding based on the one-way ANOVAs showing a statistically significant difference between the second-year group (M = 32.54) and the third- to sixth-year group (M= 31.22; p-value = 0.001), indicated that this age cohort manifested lower degrees of ethnocentrism, possibly as a result of their having received more schooling and having had lengthier exposure to multicultural classrooms during the course of their studies in comparison to the first- and second-year groups. However, since this was not investigated, there is no way of drawing credible conclusions.

The significance of the study lies primarily in finding a correlation between higher degrees of ethnocentrism in respondents who had less exposure to diversity in their own schooling career.

An unexpected fourth finding was the reliability and validity of the instrument (i.e., GENE survey) in the context of a diverse, developing country. The GENE survey, as a measure of ethnocentrism, was, to our knowledge, used for the first time in South Africa. From the data, a Cronbach alpha above 0.8 showed that the survey had high reliability and internal consistency (see Field, 2018) that aligns with the findings reported in previous studies (see Table 1). However, the variation (43.219%) explained through the EFA is not ideal since it accounts for less than half of the variance within the GENE survey. The eigenvalues also showed that the first factor is much larger than the other factors, making it evident that the GENE survey was not unidimensional in the South African context and therefore needs further investigation and possible revision. It is not known whether the respondents were reluctant to answer truthfully since they may have desired to be socially acceptable. This possibility is unaccounted for in the GENE and could therefore be a methodological limitation of the study. Using a measure like the Balanced Inventory of Desirable Responding test as an independent variable could help eliminate the possible effect that social desirability has on the validity and reliability of the findings.

In the same vein, future research needs to be conducted on a wider and more comprehensive scale. It should go beyond establishing superficial and stereotypical characteristics of ethnocentrism since the use of a single, quantitative, fixed Likert scale measuring instrument may have provided a reductionist view. Using a mixed-method design may provide a more comprehensive understanding of the concept when we are measuring ethnocentrism in similar contexts. Future studies should view ethnocentrism as a multidimensional construct that exists on a continuum and that requires synergy between quantitative and qualitative research designs for us to be able to draw valid and reliable conclusions.

Conclusion

From the findings of this study, we conclude that high degrees of ethnocentrism could indicate intolerance towards diversity in the classroom that, if left unaddressed, could affect learner performance and further hinder transformation in South African classrooms. If teachers are to be considered agents of change (le Roux, 2016; Reygan, 2019), it is imperative that teacher education programmes help preservice teachers reflect on their own beliefs regarding the interwoven nature of social diversity and how holding strong ethnocentric beliefs could perpetuate distance, prejudice, and continued segregation.

Based on Vygotsky's sociocultural theory, HEIs, especially those with a mono-ethnic profile, may need to consider curriculum transformation by creating more explicit and purposeful opportunities for their students to gain multicultural exposure and cultural competence thus preparing them for the future realities of teaching. They should also learn to identify classroom practices that could, at least potentially, be detrimental.

Such interventions can hardly be considered without attention being paid to this issue by policymakers like the CHE and DHET who may even need to revise the MRTEQ and adjust the NQF accreditation standards.

More research on preservice teachers' beliefs about issues of ethnicity-in-education will provide invaluable information regarding "our understanding of how and why teaching looks and works like it does" (Clark & Peterson, 1986, p. 256). For the classroom to become a place in which diversity is valued, teacher education programmes ought to include means of assisting preservice teachers to identify their own ethnocentrism and how to counter the many prevailing ideologies that, however inadvertently, promote ethnocentrism (Boutte, 2008) as well as those that do so explicitly.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

Ager, D. (2001). Motivation in language planning and language policy. Multilingual Matters.

Altemeyer, B., & Hunsberger, B. (2004). A revised religious fundamentalism scale: The short and sweet of it. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 14(1), 47-54. [ Links ]

Amos, R. D., & McCroskey, J. C. (1999 April 6-9). Ethnocentrism and student perceptions of teacher communication [Conference session]. Annual convention of the National Communication Association, Chicago, IL., United States.

Anderson, M. (2014). When educators understand race and racism. [Online]. https://www.tolerance.org/magazine/when-educators-understand-race-and-racism

Babbie, E., Mouton, J., Vorster, P., & Prozesky, B. (2014). The practice of social research. Oxford.

Benmamoun, M., Kalliny, M., Chun, W., & Kim, S. (2018). The impact of managers' animosity and ethnocentrism on multinational enterprise (MNE) international entry-mode decision. ThunderbirdInternational Business Review, 61(1), 413-423. [ Links ]

Bizumic, B. (2014). Who coined the concept of ethnocentrism? A brief report. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 2(1), 3-10. [ Links ]

Boutte, G. S. (2008). Beyond the illusion of diversity: How early childhood teachers can promote social justice. The Social Studies, 99(4), 165-173. [ Links ]

Boutte, G., Lopez-Robertson, J., & Powers-Costello, B. (2011). Moving beyond colourblindness in early childhood classrooms. Early Childhood Education Journal, 39(5), 335-342. [ Links ]

Brekhus, W. H. (2008). Trends in the qualitative study of social identities. Sociology Compass, 2(3), 1059-1078. [ Links ]

Bullock, L. D. (1998). Efficacy of a gender and ethnic equity in science education curriculum for preservice teachers. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 34(1), 1019-1038. [ Links ]

Cain, M. (2012). Beliefs about classroom practice: A study of primary teacher trainees in Trinidad and Tobago. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 2(3), 96-105. [ Links ]

Clark, C., & Peterson, P. (1986). Teachers' thought processes. In M. C. Wittrock (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (pp. 255-296). Macmillan.

Crump, A. (2014). Introducing LangCrit: Critical language and race theory. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, 11(3), 207-224. [ Links ]

De Luca, G., Hodler, R., Raschky, P. A., & Valsecchi, M. (2018). Ethnic favouritism: An axiom of politics. Journal of Development Economics, 132(1), 115-129. [ Links ]

Dean, E., & Veenstra, G. (2008). The relationship between cultural competence and ethnocentrism of health care professionals. Journal of TransculturalNursing, 19(2), 121-125. [ Links ]

Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET). (2015). Revised Policy on the Minimum Requirements of Teacher Education Qualifications. Government Printer.

Dewey, M. (2007). English as a lingua franca and globalization: An interconnected perspective. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 17(3), 332-354. [ Links ]

Dong, Q., Day, K., & Collaço, C. M. (2008). Overcoming ethnocentrism through developing intercultural communication sensitivity and multiculturalism. Human Communication, 11(1), 27-38. [ Links ]

Eatwell, R. (2000). The rebirth of the 'extreme right' in Western Europe? Parliamentary Affairs, 53(3), 407-425. [ Links ]

Edwards, J. (1985). Language, society and identity. Blackwell.

Edwin, C. H., Obi-Nwosu, H., Atalor, A., & Okoye, C. A. F. (2016). Toward globalization: Construct validation of global identity scale in a Nigerian sample. Psychology & Society, 8(1), 85-99. [ Links ]

Field, A. (2018). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (5th ed.). Sage.

Fittell, D. (2008). Reforming primary science education: Beyond the 'stand and deliver' mode of professional development. Proceedings of the AARE International Education Conference (pp. 1-14). Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane.

Gibbon, P. (2015). Scaffolding language, scaffolding learning: Teaching English language learners in the mainstream classroom. Heineman.

Grosser, M. (2016). Kwantitatiewe Navorsing. In I. Joubert, C. Hartell & K. Lombard (Eds.), Navorsing: 'n Gids vir die beginnnernavorser (pp. 245-270). Van Schaik.

Gumplowicz, L. (1883). Der Rassenkampf: Sociologische Untersuchungen - The racial struggle: Sociological studies. Wagner'sche Universitätsbuchhandlung.

Hammack, P. L. (2015). Theoretical foundations of identity. In K. C. Mclean, & M. U. Syed (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of identity development (pp. 11-30). Oxford University Press.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., & Babin, B. J. (2010). RE Anderson multivariate data analysis: A global perspective. Pearson Prentice Hall.

Harrison, N. (2012). Investigating the impact of personality and early life experiences on intercultural interaction in internationalized universities. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 36, 224-237. [ Links ]

Hooghe, M. (2008). Ethnocentrism. In W. A. Darity (Ed.), International encyclopaedia of the social sciences (Vol. 3) (pp. 11-12). Gale.

Incecay, G. (2011). Pre-service teachers' language learning beliefs and effects of these beliefs on their practice teaching. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 15(1), 128-133. [ Links ]

Jansen, J. (2011). Editorial: What could second-generation research on the doctorate be like? Perspectives in Education, 29(3), vi -viii. [ Links ]

Johnson, K. E. (1992). The relationship between teachers' beliefs and practices during literacy instruction for non-native speakers of English. Journal of Reading Behavior, 24(1), 83-108. [ Links ]

Johnson, K. E. (1994). The emerging beliefs and instructional practices of pre-service English as a second language teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 10(4), 439-452. [ Links ]

Kamwangamalu, N. M. (2010). Vernacularization, globalization and language economics in non-English speaking countries in Africa. Language Problems & Language Planning, 34(1), 1-23. [ Links ]

Karabenick, S. A., & Noda, P. A. C. (2004). Professional development implications of teachers' beliefs and attitudes toward English language learners. Bilingual Research Journal, 25(1), 55-75. [ Links ]

Kazempour, M., & Sadler, T. (2015). Pre-service teachers' science beliefs, attitudes, and self-efficacy: A multi-case study. Teaching Education, 26(3), 247-271. [ Links ]

Khunou, G., Phaswana, E. D., Khoza-Shangase, K., & Canham, H. (2019). Black academic voices: The South African experience. Human Sciences Research Council Press.

Knudson, R. E. (1998). The relationship between pre-service teachers ' beliefs and practices during literacy instruction for non-native speakers of English. ERIC.

le Roux, A. (2016). The teaching context preference of four white South African pre-service teachers: Considerations for teacher education. South African Journal of Education, 36(1), 1-11. [ Links ]

Levinson, D. J. (1950). Politico-economic ideology and group memberships in relation to ethnocentrism. In T. W. Adorno, E. Frenkel-Brunswick, D. J. Levinson & R. N. Sanford (Eds.), The authoritarian personality (pp. 151-221). Harper and Brothers.

Lombard, E. (2017). Students' attitudes and preferences toward language of learning and teaching at the University of South Africa. Language Matters, 45(3), 25-48. [ Links ]

Lombard, B. J. J., & Klopper, M. (2015). Undergraduate student teachers' views and experiences of a compulsory course in research methods. South African Journal of Education, 35(1), 1-14. [ Links ]

Louw, D., Louw, A. E., & Kail, R. (2014). Basiese konsepte van kinder- en adolessente-ontwikkeling. In D. A. Louw & A. E. Louw (Eds.), Die ontwikkeling van die kind en adolessent (2nd ed.) (pp. 3-50). Psychology Publications.

Mangnale, V. S., Potluri, R. M., & Degufu, H. (2011). A study on ethnocentric tendencies of Ethiopian consumers. Asian Journal of Business Management, 3(4), 241-250. [ Links ]

Marshall, S., & Moore, D. (2018). Plurilingualism amid the panoply of bilingualism: Addressing critiques and misconceptions in education. International Journal of Multilingualism, 15(1), 19-34. [ Links ]

Marx, S. (2004). Regarding whiteness: Exploring and intervening in the effects of white racism in teacher education. Equity & Excellence in Education, 37(1), 31-43. [ Links ]

McCroskey, L. L. (2003). Relationships of instructional communication styles of domestic and foreign instructors with instructional outcomes. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 32(1), 75-96. [ Links ]

Mesthrie, R. (2017). Urban cool: Social bridging in language. In C. Ballantine, M. Chapman, K. Erwin & G. Maré (Eds.), Living together, living apart? Social cohesion in a future South Africa (pp. 101-109). University of KwaZulu-Natal Press.

Nespor, J. (1987). The role of beliefs in the practice of teaching. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 19(4), 317-328. [ Links ]

Neuliep, J. W. (2002). Assessing the reliability and validity of the generalized ethnocentrism scale. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 31(4), 201-215. [ Links ]

Neuliep, J. W., & McCroskey, J. C. (1997). The development of a US and generalized ethnocentrism scale. Communication Research Reports, 14(4), 385-398. [ Links ]

Neuliep, J. W., & McCroskey, J. C. (2001). The influence of ethnocentrism on perceptions of interviewee attractiveness, credibility, and socio-communicative style. [Conference Session]. Annual convention of the International Communication Association, Washington, DC, United States.

Neuliep, J. W., Chaudoir, M., & McCroskey, J. C. (2001). A cross-cultural comparison of ethnocentrism among Japanese and United States college students. Communication Research Reports, 18(2), 137-146. [ Links ]

Pajares, M. F. (1992). Teachers' beliefs and educational research: Cleaning up a messy construct. Review of Educational Research, 62(3), 307-332. [ Links ]

Pallant, J. F. (2000). Development and validation of a scale to measure perceived control of internal states. Journal of Personality Assessment, 75(2), 308-337. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa. (1996). Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 (Act No. 108 of 1996). http://www.gov.za/documents/constitution/chapter-1-founding-provisions#5

Republic of South Africa. (1997). Higher Education Act. https://www.up.ac.za/media/shared/409/higher-education-act-1997.zp86770.pdf

Republic of South Africa. (2008). National qualifications framework Act 67 of 2008. https://www.saqa.org.za/docs/legislation/2010/act67.pdf

Reygan, F. (2019). Sexual and gender diversity in schools: Belonging, in/exclusion and the African child. Perspectives in Education, 36(2), 90-102. [ Links ]

Richardson, V. (1996). The role of attitudes and beliefs in learning to teach. In J. Sikula (Ed.). The handbook of research in teacher education (2nd ed.) (pp. 102-119). Macmillan.

Roux, C., & Becker, A. (2016). Humanising higher education in South Africa through dialogue as praxis. Educational Research for Social Change, 5(1), 131-143. [ Links ]

Roy, K. M. (2006). Measures of racial prejudice. In Y. Jackson (Ed.), Encyclopedia of multicultural psychology (pp. 292-294). Sage.

Shimp, T. A., & Sharma, S. (1987). Consumer ethnocentrism: Construction and validation of the CETSCALE. Journal of Marketing Research, 24(3), 280-290. [ Links ]

Simmel, G. (1955). Conflict: The web of group-affiliations. Free Press.

Star, N. S. (2000). The effects of international student exchange programs on ethnocentrism andethnonationalism (Unpublished Master's dissertation). Pepperdine University, Malibu, CA, United States. [ Links ]

Sumner, W. G. (1906). Folkways: A study of the sociological importance of usages, manners, customs, mores, and morals. Ginn and Company.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Pearson Education.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1982). Social identity and intergroup relations. Cambridge University Press.

Thomas, K. M. (2018). Colour-blindness as ideology. [Online]. https://www.asbmb.org/asbmb-today/opinions/080118/colorblindness-as-ideology

Trochim, W. M., Donnelly, J. P., & Arora, K. (2016). Research methods: The essential knowledge base. Cengage Learning.

Van der Westhuizen, C. (2018). South Africa's white right, the Alt right and the alternative. [Online]. https://theconversation.com/south-africas-white-right-the-alt-right-and-the-alternative-103544.

Vandeyar, S. (2008). The attitudes, beliefs and anticipated actions of student teachers towards difference in South African classrooms. South African Journal of Higher Education, 22(3), 692-707. [ Links ]

Vandeyar, S. & Vandeyar, T. (2017). "Opposing gazes: Racism and xenophobia in South African schools." Journal of Asian and African Studies, 52(1), 68-81. [ Links ]

Vibulphol, J. (2004). Beliefs about language learning and teaching approaches of pre-service EFL teachers in Thailand (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK, United States. [ Links ]

Vygotsky, L. (1978. Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

Wrench, J. S., Corrigan, M. W., McCroskey, J. C. & Punyanunt-Carter, N. M. (2006). Religious fundamentalism and intercultural communication: The relationships among ethnocentrism, intercultural communication apprehension, religious fundamentalism, homonegativity, and tolerance for religious disagreements. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 35(1), 23-44. [ Links ]

Wrench, J. W., & McCroskey, J. C. (2003). A communibiological explanation of ethnocentrism and homophobia. Communication Research Reports, 20(1), 24-33. [ Links ]

Xu, L. (2012). The role of teachers' beliefs in the language teaching-learning process. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 2(7), 1397-1402. [ Links ]

Yiakoumetti, A. (2003). Language education in our globalised classrooms: Recommendations on providing for equal language rights. In M. Solly & E. Esch (Eds.), Language education and the challenges of globalisation: Sociolinguistic issues (pp. 13-32). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Young, C. A., Haffejee, B., & Corsun, D. L. (2017). The relationship between ethnocentrism and cultural intelligence. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 55(1), 31-41. [ Links ]

Yusof, N. M., Abdullah, A. C., & Ahmad, N. (2014). Multicultural education practices in Malaysian preschools with multi-ethnic or monoethnic environment. International Journal of Multicultural and Multireligious Understanding, 1(1), 12-23. [ Links ]

Received: 12 January 2021

Accepted: 24 May 2021

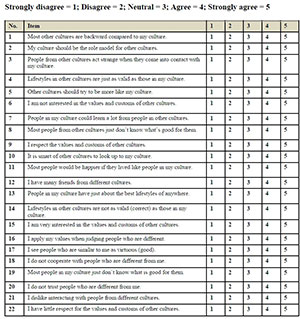

Generalised Ethnocentrism (GENE) survey

Work quickly and record your first reaction to each item. There are no right or wrong answers. Please indicate the degree to which you agree or disagree with each item using the following five-point scale:

Researcher's note: How to calculate the ethnocentrism score

1. Recode questions 4, 7 and 9 with the following format: 1 = 5; 2 = 4; 3 = 3; 4 = 2; 5 = 1

2. Drop the following questions: 3, 6, 12, 15, 16, 17 and 19

3. Add up the 15 remaining questions.