Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of Education (University of KwaZulu-Natal)

On-line version ISSN 2520-9868

Print version ISSN 0259-479X

Journal of Education n.84 Durban 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2520-9868/i84a06

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Exploring how the national COVID-19 pandemic policy and its application exposed the fault lines of educational inequality

Ronicka MudalyI; Vimolan MudalyII

ISchool of Education, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa. Mudalyr@ukzn.ac.za; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7347-2098

IISchool of Education, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa. Mudalyv@ukzn.ac.za; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3570-1256

ABSTRACT

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many surveys in education were conducted. These revealed alarming statistics about learners losing half of the academic year, parents' anxiety about sending children to school, and a minority of education institutions being able to offer online teaching. In response to a cacophony from teachers' and students' unions, school governing body representatives, scientists and education experts, the government decided to close education institutions as part of what was known as the hard lockdown. Against this background, we used critical policy analysis (CPA) to explore decision-making by education departments and the enactment of these decisions at schools. This qualitative study revealed iniquity and inequity as departments of education made decisions to close and reopen institutions. The findings revealed a tension between expectations of producers of policy and enactors of policy within unequal school settings. We recommend a repositioning from the perspective of the dispossessed to inform future policy.

Keywords: critical policy analysis, educational inequality, educational policy, policy enactment

Introduction

Under so-called normal circumstances, education is a complex undertaking, especially in the context of deepening neoliberal agendas. Performance pay, financial austerity, and the tension between raised standards and diminished resources (Apple, 2019) make good teaching and learning nearly impossible. This provides the impetus for reform-based agendas and provokes critical questions. For example: "What constitutes what we might call a good curriculum?"; "Whose interests does it serve?"; "What is powerful knowledge (Apple, 2019)?"; and "Who claims and controls the authoritative knowledge mantle?" These questions are linked to reforms in education that are underpinned by ideological versions of what a good education is. In South Africa, many critical educators work towards teaching and learning that is embedded in a social justice framework in order to address social and educational inequalities that sustain class and racial supremacy. However, the outbreak of COVID-19 exposed the declivity of education for the masses, a situation born of social injustice in South Africa. This forced policy analysts to take a critical retrospective gaze at the education landscape, and inside this temporal space to underscore the real impact of educational inequality on people's lives. Our research focussed on two aspects of policy. First, we explored the production of policy by analysing policy documents and data from a key informant interview. Second, we considered the views of recipients and enactors of policies who were educators. In this way we sought to research the intersection between policy production and policy implementation and the power relations that underpin this, within a context of severe inequality, during a global pandemic. We aim to answer the following questions:

• What politics informed the creation of education policies during COVID-19?

• What were the experiences of educators at schools who received and enacted these policies?

In attempting to answer these questions, we begin with a brief discussion on inequality in the education sector in South Africa. We present the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the education sector and follow this with theoretical insights from critical policy analysis and rhetorical analysis. Next, we present and analyse data, and, finally, we offer concluding remarks.

Inequality in the basic education sector

Apartheid era legislation in South Africa resulted in black Africans being legislatively disenfranchised and geographically dispossessed. The politics of race severely marginalised and excluded the majority of black learners (de Kadt, 2020). Divisive apartheid machinery entrenched its separatist oppressive ideology by making educational institutions "a legal entity" and a "creature of the state" (Bunting, 2006, p. 37). The resultant inequality rendered schools in South Africa "very different places" and these differences continue to be reflective of the profoundly unequal societies in which they are located (Christie, 2020, p. 2).

According to the Curriculum Assessment and Policy Statement (CAPS), produced by the Department of Basic Education (DBE) (2011), the social mandate of schools is to prepare young people to become responsible citizens who can participate meaningfully in society, irrespective of their race, gender, class, culture, physical, or intellectual ability. This noble goal has not been realised, given that where a learner is born and the race and socio-economic class of their family determine the type of school they will attend as Amnesty International (2020) has pointed out. Socio-economic inequality has resulted in an education system in which 75% of mainly poor black learners attend under-resourced schools with poor infrastructure and overcrowded classrooms (Parker et al., 2020; Van der Bergh & Spaull, 2020). In 2018, the government conducted a survey of 23,471 schools, and found that 86% had no laboratories, 77% had no libraries, 72% had no internet facilities, and 19% relied on illegal pit latrines for sanitation (Amnesty International, 2020). Large learner to teacher ratios, scant resources (Black, 2020; Vorster, 2020) and ill-educated teachers (Vally, 2019), deepen the crises in education. In these settings, chronic underperformance of learners is the norm (Amnesty International, 2020). Thousands of learners are suspended in a liminal space that is influenced by the effects of a lack of institutional accountability within a democratic government, as well as the legacy of apartheid, both of which have sustained socio-economic disadvantage among the majority of learners.

Effects of COVID-19 on education

Emerging and re-emerging diseases can create havoc in public health systems, the national economy, and in education; this is not a new phenomenon. The influenza outbreaks of 1918 and 2009, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome in 2012, and the Ebola epidemic in 2014 are some such examples. In anticipation of a pandemic, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 a public health emergency of international concern on 30 January, 2020. According to Coulibaly and Madden (2020, p. 1), the declaration of COVID-19 as a global pandemic by WHO on 11 March, 2020 "removed any doubt about the threat that the virus poses to every country in the world."

Although COVID-19 is a global pandemic, socio-economically constrained countries, especially those in sub-Saharan Africa, will be more severely affected (World Bank Group, 2020). The global shutdown has affected all aspects of life, and the effects on education have been unprecedented. In South Africa, the Ministries of Basic Education and of Higher Education and Training made the decision to declare an early recess in school and Post School Education and Training sectors. Ministers then announced a shift to an online mode of learning. Endowed with the privilege of coloniality, middle-class learners apparently adapted well to this technocratic intervention, and forged ahead with their academic endeavours, while working-class learners, often in densely populated wretched spaces, struggled to obtain data and devices (Parker et al., 2020). The shameful legacy of educational inequality, while present all the time, became highly visible after the onset of COVID-19. The most vulnerable, especially girls and children, became more peripheralised since they bore the brunt of multiple forms of violence (African Child Policy Forum, 2020). The impossibility of home schooling for most children, as well as other impacts on their lives, resulted in the decision to embark on a phased-in reopening of schools and higher education institutions. The National Income Dynamics Study-Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (NIDS-CRAM)-revealed that most learners lost 40 to 43% of the school year in 2020 (Mohohlwane et al., 2020). Children from wealthier households were three times more likely to have returned to school than those from poorer ones. Therefore, recovery of learning is crucial if social and economic fractures are not going to worsen. The Early Childhood Development (ECD) sector was severely affected by the pandemic with only 13% of children in the 0- to 6-year range having returned to ECD programs between July and August 2020. This attendance figure of 13% was the lowest recorded in 18 years (Mohohlwane et al., 2020).

Education policy decisions were initially informed by members of the scientific community, who were deemed a monolithic authority, and they prescribed the way forward (Sayed & Singh, 2020). Contextual inequalities in learners' domestic and school or higher education institutions were not adequately considered, and learners were (and continue to be) buffeted by policy decisions that warrant further scholarly inquiry.

Theoretical orientation

Traditional Policy Analysis (TPA), an intentional, research-based process by a selected group of actors, has been popular in educational research for some time. It includes "planning, adoption, implementation, examination and/or evaluating . . ." (Young & Diem, 2018, p. 1). Costs and benefits of the strategy are evaluated and this is expected to contribute to a deeper understanding of policy planning and implementation, with a view to solving problems in education. The linearity of thought and processes in this approach render the positivist underpinnings that frame it more visible. We depart from the TPA approach because it offers a parochial perspective on human behaviour and socio-cultural issues by privileging an input-output model (Young & Diem, 2018). The need to move away from TPA is rendered more urgent by the COVID-19 pandemic that has presented dynamic complexities in uncertain times. To examine educational policy, we gaze through the alternative lens of Critical Policy Analysis (CPA), since critical policy researchers problematise the power, ideology, and control at the core of educational policy, and, in doing so, illuminate inequality (Lugg & Murphy, 2014).

We borrow the following critical practices selectively from Young and Diem (2018, p. 3) to examine how educational policy contributes to the subversion or the support of rights and values within a democratic South Africa.

• CPA explores the distribution of power, resources, and knowledge and the creation of 'winners' and 'losers.'

• CPA is concerned with social stratification and the impact of policy on relationships of privilege and inequality.

We explore how these policies reflect on the state of the basic education sector in South Africa in terms of inequality and crisis management during the COVID-19 pandemic. We also borrow the additional theoretical tools of rhetorical analysis, espoused by Nicoll and Edwards (2004), to examine policy statements. These tools include crisis narrative, a shared immersion in education, narrative organisation, and corroboration and consultation.

Methodology

Following Levitt et al. (2017), the qualitative approach of this study, within the critical paradigm, was useful for exploring insights related to the educational policy of the different actors during a public health emergency. Many different methods were used to understand what informed education policy decisions, and how these were received and enacted (see Mohajan, 2018). We generated data by analysing policy documents, conducting one key informant interview (KII), and conducting a survey with school personnel. The key informant was a senior education official in the national Department of Education who was deemed to be a repository of "first-hand information and knowledge" (Mumtaz et al., 2014, p. 133) about policy decisions. The KII was used to understand the "how" and "why" of policy decisions (see Mohajan, 2018, p. 24). Seventy-three survey questionnaires were sent to teachers, principals, and teachers' union representatives at schools using a Google Form and, of these, 30 were completed and returned. We designed survey questionnaires to understand how policies were received and enacted. We analysed policy documents and media release statements that were in the public domain to elicit meaning, and to understand why policies and media release statements were formulated in particular ways (see Bowen, 2009).

We used convenience and purposive sampling methods. Purposive sampling (see Maxwell & Chmiel, 2014) involved the selection of participants based on defining characteristics that identified them as holders of the rich information we needed for this study. Using convenience sampling, we selected 73 recipients/enactors of policy. We refer to these enactors of policy as educators, and they included teachers, union representatives, and principals. These educators had participated in postgraduate seminars and were opportunistically available (see Lopez & Whitehead, 2013). The prospective participants experienced the effects of pandemic policy because they were practising teachers during 2020, and were well suited to respond to the survey. The 30 educators who responded came from 30 different schools. Four teachers were from independent or private schools that were classified as advantaged while another four teachers worked at well-resourced public schools that were also advantaged. Following Amnesty International (2020), these eight schools were deemed to be advantaged because they had running water, sanitation, laboratories, libraries, spacious classrooms and grounds for sports and leisure, adequate infrastructure, information and computer technology resources, and low learner to teacher ratios. Three principals, one union representative, and eighteen teachers were from less advantaged public schools that served poor communities. The 22 schools that were deemed disadvantaged, did not enjoy these affordances and most of the learners they served were from low socio-economic households.

Data presentation and analysis

We used thematic analysis (see Maxwell et al., 2014) to interpret the data. The themes and sub-themes that emerged were:

• Pandemic policy

• Lived experiences of policy

o Enacting COVID-19 protocols

o Information and Communications Technology (ICT) and enacting the curriculum during COVID-19

o Enacting practical work while observing COVID-19 policy

We go on to examine some of the policies that were formulated to manage education during the pandemic and the lived experience of the educators who enacted these policies.

Pandemic policy

The profound impact of the pandemic was unexpected and the Department of Basic Education initially referred all enquiries to the Department of Health since they believed it was better qualified to clarify uncertainties. As the COVID-19 infection numbers swelled, schools were closed despite objections from many people, institutions, and researchers all of whom raised concerns about worsening the pre-existing social disadvantages of poor learners and parents. They also argued that COVID-19 infection rates should not be the sole determinant of school closures since schools provided children with better food security and personal safety. Under mounting pressure, schools were re-opened based on persuasive policies that were presented in a hierarchically ordered narrative. This revealed a fragmented policy environment that was complicated by multiple actors and discordant institutions.

At a media briefing on 9 March, 2020, that was captured in a policy brief, the Minister of Basic Education cautioned everyone involved in the schooling sector about the perils of COVID-19. The DBE had received enquiries about how they intended to deal with the pandemic in schools and had released a statement saying "[W]e have received many enquiries regarding our plans to deal with the Coronavirus in schools. We have redirected all the enquiries to the Department of Health that is leading the interventions regarding the management of cases" (DBE Media Release Statement, 9 March, 2020d). The DBE had elected to absolve itself from decisions about how the education sector would manage the pandemic because of sparse information about the effects of the virus on children. A "crisis narrative" (Nicoll & Edwards, 2004, p. 49) is evident here, as well as corroboration by another government department, as an attempt to persuade the acceptance of the standpoint of the DBE at the beginning of the pandemic and during subsequent months.

Circular 1 of 2020 (DBE, 2020a) that was sent to schools before 15 March, 2020, provided COVID-19 guidance for childcare facilities and schools. It provided guidance on monitoring absenteeism and on establishing procedures for personnel and learners who are ill at school. In addition, it provided guidelines related to learners who had travelled recently to areas that had reported community spread of COVID-19, or learners who had been exposed to cases of COVID-19. Another directive contained in Circular 3 of 2020 (DBE, 2020b) stated that while at home, learners should engage in the "Read to Lead programme, maths buddies, constructive holiday assignments, etc. through the supervision and guidance of parents. . ." When we read this statement, we wondered whether the DBE was unaware that most South African parents do not have the capacity or training to guide and supervise children's work. In saying this we do not construct financially deprived parents as intellectually or morally deficient, or uncaring about their children's education, but we do acknowledge that their material existence does not allow them to scaffold concepts, mediate, monitor, and evaluate their children's learning. This policy directive, then, was formulated for a minority of privileged, middle-class households, and excluded the majority of learners who are financially and socially deprived. Lines of division of educational opportunity between wealthy and poor households became more entrenched in this way.

The decision to close schools was vigorously contested. The adverse effects seemed to far outweigh the effects of the virus and yet schools were closed for a prolonged period as Taylor (2020) noted. Van der Berg's (2020) call for schools to remain open was based on schools addressing food insecurity and other challenges that stemmed from being absent from schools such as the greater risk of substance abuse and child abuse, and mental health challenges. It was also argued that school closures would create curriculum gaps, the effects of which would be felt for many years to come. In South Africa, school nutrition programmes are particularly important in sustaining more than nine million learners with a daily meal (Black et al., 2020). While the social welfare of learners was underscored by researchers like these, the DBE relied on decisions of health scientists who viewed schools as places in which the risk of transmissibility is high, and therefore recommended the school closures. In a combined advisory, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), the World Bank, the World Food Programme and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) (2020) all noted that the "the adverse effects of school closures on children's safety, wellbeing and learning are well documented" (p. 1). They argued for evaluating the benefits and risks in individual contexts to inform reopening schools in saying,

Disruptions to . . . time in the classroom can have a severe impact on a child's ability to learn. The longer marginalized children are out of school, the less likely they are to return. Children from the poorest households are already almost five times more likely to be out of primary school than those from the richest. Being out of school also increases the risk of teenage pregnancy, sexual exploitation, child marriage, violence and other threats. Further, prolonged closures disrupt essential school-based services such as immunization, school feeding, and mental health and psychosocial support, and can cause stress and anxiety due to the loss of peer interaction and disrupted routines. (p. 2)

However, UNESCO et al. added that decisions about reopening schools should be based on considering transition points (for example, between primary and secondary schooling), the capacity to sustain remote learning, and the capacity to maintain safety protocols, among others. The following excerpt captures the essence of the UNESCO position: "School re-openings must be safe and consistent with each country's overall Covid-19 health response, with all reasonable measures taken to protect students, staff, teachers and their families" (p. 2).

Pressure mounted from different quarters for the re-opening of schools. Eventually, the DBE re-opened them, and this was motivated by advice from the Ministerial Advisory Committee on COVID-19 as well as the DBE's Annual Performance Plan 2020/21 that states that

the overall goal of the various actors in the basic education sector must remain to improve the quality of learning outcomes and reduce educational inequalities. We should not lose sight of this. South Africa has been on an upward trajectory in terms of the skills acquired by learners for around two decades . . . The momentum of this improvement cannot be lost as a result of the pandemic. (DBE, 2020c, p. 20)

There was deepening fear that if schools did not remain open learners would lose the benefits of the progress they had made. The DBE acknowledged that the pandemic would have a lasting but as yet indeterminate impact on the education system. It identified COVID-19 as a key risk to the completion of the curriculum and assessments and a barrier to ensuring quality, inclusive, safe, and healthy basic education.

The allusion to advice from the Ministerial Advisory Committee on COVID-19 reflects the reification of policy that is effected by presenting what Nicoll and Edwards (2004) referred to as authoritative groups being supportive of the DBE policy. It shows that policy emerged as a result of consultation processes, and this renders policy more persuasive. The "narrative organisation" (Nicoll & Edwards, 2004, p. 49) of the policy brief is important. It begins with a social justice imperative to "reduce educational inequalities" and emphasises the gains of the past decades. Then the importance of not losing these gains by keeping schools closed is alluded to as a final convincing argument. The use of "we" (DBE, 2020c, p. 20) creates a connection between the author and the audience. This implied relationship, a shared "immersion" in education, is a strategy of persuasion (Nicoll & Edwards, 2004, p. 48).

On 29 May, 2020 the DBE issued the following directive related to the re-opening of schools.

Sanitizers, disinfectants and masks. . . should be easily accessible, sufficient quantities of hand sanitizer (minimum 70% alcohol) based on the number of learners . . . facilities for washing of hands with soap and clean water . . . school must (a) provide each official and educator, with a minimum of two cloth face masks; and (b) require learners and any other person entering the office or school premises to wear a cloth face mask . . . (Government Gazette Notice 302, 2020a, p. 12).

Instructions that included socio-behavioural measures to stem the spread of the pandemic and daily cleaning of work surfaces along with more regular cleaning of toilets and shared equipment, were also issued.

The politics that governed decisions on educational policy regarding opening and re-opening of schools were based on advice from the Ministerial Advisory Committee on COVID-19 that was led by virologists and other biomedical scientists. The government was criticised for its over-dependence on scientific experts to inform policy-related decisions, with limited input from experts in the humanities (Sayed & Singh, 2020).

These policy decisions resonated with the KII data we sourced from the senior education official who described extensive planning having preceded the reopening of schools when he said,

In order to prepare and regulate the school environment, the Department published a series of Directions under the National State of Disaster Regulations. The Departments immediately set up different structures to respond to the pandemic and the anticipated effect it would have on education. These were responsible for various tasks which included, but were not limited to, the development of Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs); development and translation of information booklets on Covid-19; evaluation, aggregation and development of educational content to support remote learning; facilitating the zero-rating platforms for educational content; the revision of Annual Teaching Plans (ATPs) etc. Extensive plans were put in place around the strengthening of support on the availability of water and sanitation.

The key informant interviewee emphasised critical factors that needed to be considered before any policy for re-opening of schools was established. The narrative structuring of the KII statement is significant. It begins with the National State of Disaster Regulations that are laden with authority, and in this way, reification is effected (see Nicoll & Edwards 2004). The hierarchical ordering of the narrative, from the National State of Disaster Regulations, to various (provincial education) departments, to the development of standard operating procedures, adjusting education content, making remote learning more affordable, and providing basic needs such as water and sanitation, is clear in this plan.

Against this brief background of the production and distribution of policy (see Apple, 2019), we examine how this was received and enacted by educators given the second theme.

Lived experiences of policy

Our attempt at understanding the lived experiences of policy revealed three sub-themes, namely, enacting COVID-19 protocols, ICT and enacting the curriculum during COVID-19, and conducting practical work while observing COVID-19 policy. Because of inequalities, the implementation of policy evolved differently based on school infrastructure and basic services, the agency of the teachers' unions, the capacity for using and leveraging technology, and the availability of resources for practical work.

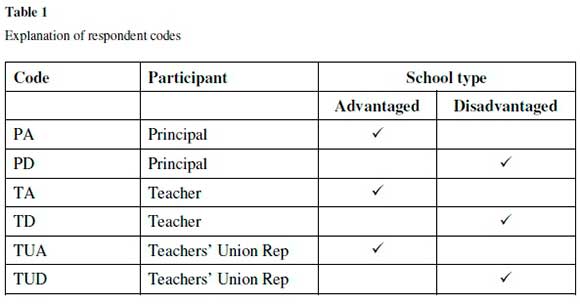

We explored the experiences of educators who were recipients of policy and enactors of policy directives at schools. The purpose was to explore the resonance between the production and the enactment of policy. Respondents were assigned codes according to whether they were teachers (T) or principals (P), and whether they worked in advantaged (A) or disadvantaged (D) schools. Union representatives were assigned an additional code (U).

Enacting COVID-19 protocols

Respondents were asked about their views on whether the DBE had had plans for schools related to observing COVID-19 protocols. Some of the responses were as follows.

PD: Yes, done by us as principals. No support from DBE

TD: Yes, plans were made but not adequate.

TD: At the beginning there were no plans, but eventually after lockdown the department of education decided to come with plans such as social distancing and phasing in of learners after approximately five months. Even though there were plans after lockdown, but it did not benefit all schools, especially rural schools.

Although detailed plans were provided in circulars, media release statements, and policies, and were also mentioned by the senior official in the KII, some recipients of policy believed that no organised planning had been done. A persistent feature of responses from school personnel was one of abandonment-the sense of having to manage their schools creatively with limited resources. The following responses solidified the notion of schools having to cope with COVID-19 challenges almost alone.

PD: There were actions that applied to the different institutions but as for schools, no action was taken by the DBE but principals had to do the required protocols. Except for giving each school a cleaner and a screener. These too (in some cases) were problematic because the number employed could not cope with the number of students at schools.

PD: There was no monitoring of how or what was going to be a way forward.

Some teachers, however, reported a more positive experience.

TA: Circuit Managers visited schools when problems arose and addressed issues. In the main, schools had to resolve their own problems.

TA: We were provided with Standard Operating Procedures for Educators. Educators were trained and instructed to implement procedures.

The guidance obtained from the Standard Operating Procedures, and the training of teachers to use these, was valued by some respondents.

On distribution of policy, one teacher asserted that "the President's announcement was enforced by people in authority." This reveals how policies suffused with authority and power (Apple, 2019) were distributed.

Inadequate or a complete lack of support from the DBE for schools to implement COVID-19 protocols was reported by some educators. The senior official, however, indicated that there was weekly monitoring, evaluation, and reporting on the state of readiness of schools. In the main, school principals were tasked with ensuring that regulations were adhered to, regardless of the inadequate personal protection equipment (PPE) or personnel required.

Having received and experienced these policies, educators were asked about the successes of the measures taken by the DBE to stem the spread of the pandemic when schools re-opened.

TUD: We pressurized for the correct quality and quantity of PPE. The supply of water, which had been neglected for 26 years was addressed and most schools received some form of water supply. Teachers with co-morbidities were given leave. Schools with poor infrastructure, especially ablutions, were improved. At first [policy was] highly effective in certain areas. In others, because of socio-economic conditions such as overcrowding, persons (learners) could not remain indoors and spilled into streets. Schooling was at a standstill.

This reveals that in some instances teachers' unions had to intervene in order to secure adequate PPE and that the shameful neglect of basic infrastructure in schools for poor learners was addressed to some extent with the provision of ablution facilities and water supplies. Several schools needed the COVID-19 emergency water supply (water tanks) and sanitation in the form of chemical toilets (Government Gazette, 2020b). This confirms that what Ndlovu-Gatsheni (2020) referred to as a systemic civilizational crisis continues to plague many schools.

Teachers' unions seem to have seized the COVID-19 moment to ensure that the DBE's plans for the provision of water and sanitation to schools were realised, and this was viewed as a success. However, spatial constraints did not allow for social distancing. The pandemic illuminated the effects of decades of neglect that did not allow some public schools to resume, even when certain infrastructure was provided.

ICT and enacting the curriculum during COVID-19

Educators were asked about their experiences related to implementing the curriculum during COVID-19. An educator (TA) who taught Information Technology at a private school, where learners paid an annual fee of R120,000, reported that

all resources (worksheets/past papers) were available electronically. Resources were posted/uploaded to the online portal (Google Classroom).

A Physical Sciences teacher (TA) at a fee-paying public school explained,

Worksheets were printed and distributed using the D6 app. The D6 app is an app that is zero rated that students and parents download from Google play store. The school publishes worksheets and memos for students.

However, most of the respondents said that they did not have access to adequate resources for remote teaching. The following excerpts were from educators in disadvantaged public schools.

TD: My school has no facilities for online teaching and learning therefore any kind of online format would help. However, not all students have the means for online teaching.

TD: Giving all learners data to access online lessons would have prevented them sitting at home being idle. It could have assisted me to give them work on a continuous basis and engage with their queries.

An acting principal (PD) at a public school that served a poor community explained,

E-learning seems so far-fetched in a semi-rural area, like my school. However, it needs to be seriously looked at as a tool to assist with teaching/learning. It would have obviated the mindset of 'holiday' being entrenched in the minds of learners.

There were teachers in public schools who had partial access to online resources, as is evidenced by the following excerpt.

TD: Learners were given tablets by the DBE for remote learning. That process somehow was not adequately enacted as some of them did not receive the gadgets. Moreover, they were not orientated on using them fruitfully for educational purposes, as most of them could not access the internet on weekends. That alone is a barrier to teach remotely as we prepare online classes via Microsoft Teams mostly in our free time on weekends. It becomes extremely hard without the internet.

Executing practical work while observing COVID-19 policy

Educators were asked about how they executed practical work in subjects such as Life Sciences, Information Technology, Physical Sciences, and Natural Sciences while maintaining social distancing and sanitising shared equipment and spaces.

A teacher (TA) from a private school that catered to wealthy learners, responded,

Our practical work includes programming, yes this was done using the relevant program. I shared my screen on our online meeting to explain concepts and implement them in coding. Our IT labs have sufficient computers. Therefore, no sharing. Computers were sanitised before every use. Computers between learners were spaced sufficiently [far] apart. In addition, boards were used to separate each learner to avoid direct contact between learners.

Another teacher (TA) at an advantaged public school described a strategy for practical work.

After COVID, no practical [was] performed by students. All practical work was performed by me as a demonstration and a practical test was administered.

Two teachers (TD and TD) at a no-fee paying school, where 90% of learners come from poor, rural areas, explained,

There is no laboratory at our school so no sharing as there is no equipment.

I did not do practical work. I showed them videos on YouTube.

Based on the survey data, we wonder whether the DBE ever considered the capacity of all schools to enact the Standard Operating Procedures as per DBE requirements. Did all schools have running water to maintain the hygiene requirements? Did all schools have adequate space for maintaining social distancing among learners? Did all schools have adequate screeners and cleaners, to cope with the learner population density? We argue that the DBE could have done things differently by considering these questions, based on diverse experiences of enacting the curriculum, that were inextricably linked to compliance with policy. In some schools, there was no change in the teaching of practical work because this was impossible before the pandemic since these schools lacked essential facilities and equipment. Other schools adhered to the policy by relying on teacher demonstrations instead of arranging learners in groups for hands-on practical work for which they would have had shared equipment. Some skills for practical work, for example designing investigations, handling equipment, measuring and counting using specialised equipment, conducting investigations, recording, interpreting and presenting results, would not have been achieved, so certain outcomes in the CAPS curriculum would have been unattainable. Wealthier schools were able to conduct practical work individually because they had the advantage of small class sizes, adequate space, and resources for disinfecting equipment. ICT-enabled schools had different levels of success in achieving curriculum outcomes based on, among other resources, the provision of devices, availability of internet access, and proficiency in using devices. Schools without ICT infrastructure had to contend with learners being what was thought of as idle and having a holiday mindset as teaching and learning became increasingly difficult.

Discussion

While there was a flurry of activity to provide life-saving resources such as water and sanitation to under-resourced schools, the more advantaged schools could expend their energies on training staff to move to online platforms such as Google Classroom and Microsoft Teams. The "pandemic pedagogy accomplished through the modality of the machine and accompanying online learning platforms" (Fataar & Badroodien, 2020, p. 2) allowed wealthier learners, privileged with abundant resources at home and at school, to transition between contact and online modes of delivery, whether schools opened fully or partially or shut down during the year. We intentionally position different experiences of policy by educators in schools with minimum infrastructure and resources, alongside those in more advantaged schools whose preoccupation was with teaching and learning using technology. This revealed the effects of socio-economic inequality on the stratification of schools, based on uneven distribution of resources, learning opportunities, human dignity and ontological density within a fractured basic education sector. The positions of "winners" and "losers" (Young & Diem, p. 3) were more deeply entrenched by the COVID-19 moment.

This study revealed that policy was difficult to implement in some schools because contextual factors that were compounded by the perceived lack of support from the DBE, simply did not allow for this. In 2020, the National Income Dynamics Study Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (Mohohlwane et al., 2020) revealed that many independent and private schools received exemption and remained open during the lockdown, and that learners from wealthy households were three times more likely to attend school than those from poor households. Poorer schools could not afford or did not receive PPE, were spatially restricted, and struggled to comply with the regulations. The digital divide among South African learners, most of whom lack devices, cannot afford data, or do not have access to stable connectivity, made the transition to online learning impossible. In addition, many learners lack digital literacy skills and physical spaces that are conducive to working from home using online technology (Parker et al., 2020). So, this invites several questions: Were policy decisions premised on a homogenous view of capacity and resources of schools to cope with the pandemic? Was the likelihood that a technology-based education solution would be successful mainly in institutions that enjoyed historically and socio-economically endowed cultural privilege, overlooked by the basic education sector? Was the imperative to stabilize education and save the school year so intense that it resulted in a blinkeredness to race and class deprivation?

Conclusion

The COVID-19 moment has rendered the fault lines of educational inequality highly visible. An analysis of some of the COVID-19 policies, related to socio-behavioural rules, school closures and openings, trimming of curricula, and online learning, were initiated by directives from the Office of the President. Subsequent policies, although well-intentioned by the DBE, were not enacted by recipients according to how policy was formulated. For example, the phased return of learners was fraught with problems because of the unavailability of PPE and poor communication. There was dissonance between the expectations of policy makers and the expectations of school personnel of policy makers.

The inability of policies in education to address the provision of basic infrastructure during the pre-COVID-19 era reveals the power of those in authority to perpetuate the subordination and indignity of poor learners during almost three decades of democracy. Faced with many challenges, the best efforts of school personnel in disadvantaged schools, as enactors of policies, were futile in many instances. Many difficulties may be attributed to the rhetoric that surrounds policy and the experienced reality (see Apple, 2019). The policy appeared to promise safe spaces for teachers and learners but some of the respondents claimed that PPE was not available or was of substandard quality. The enactors of policy then felt isolated, abandoned, exhausted, and overwhelmed by many different responsibilities.

Compromises related to policy formulation included online/blended learning, curriculum trimming, and reorganising timetables. While ICT resources were leveraged in some instances, poor connectivity and low proficiency in the use of the devices hampered teaching and learning. The absence of ICT resources in other disadvantaged schools severely interrupted teaching and learning, and without schooling, learners were propelled into an idle, holiday mindset. The inability of enactors of policy in disadvantaged schools to engage learners in hands-on practical work because these were space- and resource-constrained sites, is in stark contrast to wealthier schools at which lessons progressed relatively uninterruptedly, and curriculum outcomes were likely to have been achieved.

What is required is a "repositioning" (Apple, 2019, p. 280) for policy makers to view the education sector through the eyes of the masses who are dispossessed. This could facilitate some understanding of the lived educational experiences of principals, teachers, learners, and parents. The COVID-19 pandemic can refocus the political implications of policies, that are, in reality, often only suitable for a small minority of the elite, and should be deeply reflected upon by those in power. The COVID-19 moment should stimulate a critical look at the pre-COVID-19 educational landscape, and a deconstruction of what counts as good education, who this benefits, and how the unequal "distribution of power, resources, and knowledge" creates "winners" and "losers" (Young & Diem, p. 3). This consciousness-raising can give birth to a re-imagining of an education that strives to achieve social justice goals.

Acknowledgement

This research was made possible with the cooperation of the National Research Foundation, Department of Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation (RSA), and the Government Technical Advisory Centre.

References

African Child Policy Forum. (2020). Under siege: Impact of COVID-19 on girls in Africa. African Child Policy Forum.

Amnesty International. (2020). Broken and unequal: The state of education in South Africa. Amnesty International.

Apple, M. W. (2019). On doing critical policy analysis. Educational Policy, 33(1), 276-287. [ Links ]

Black, S. (2020, 11 May). The problem with Stephen Grootes' views about online learning. Daily Maverick. https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2020-05-11-the-problem-with-stephen-grootes-views-aboutonline-learning/

Black, S., Spreen, C. A., & Vally, S. (2020). Education, COVID-19 and care: Social inequality and social relations of value in South Africa and the United States. Southern African Review of Education, 26(1), 40-61. [ Links ]

Bowen, G. A. (2009). Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(2), 27-40. [ Links ]

Bunting, I. (2006). The higher education landscape under apartheid. https://www.ses.unam.mx/curso2017/bibliografia/Bunting%202006%20HE%20under%20apartheid.pdf

Christie, P. (2020). Decolonising schools in South Africa: The impossible dream. Taylor & Francis Group.

Coulibaly, B. S., & Madden, P. (2020, March 18). Strategies for coping with the health and economic effects of the COVID-9 pandemic in Africa. Brookings.

de Kadt, E. (2020). Promoting social justice in teaching and learning in higher education through professional development. Teaching in Higher Education: Critical Perspectives, 25(7), 872-887. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education. (2020a). Circular No. 1 of 2020: Containment/management of COVID-19 for schools and school communities. https://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/Documents/Publications/Guidelines%20for%20Childcare%20Facilities%20and%20Schools%20-%2011%20March%202020.pdf?ver=2020-03-12-100451-990

Department of Basic Education. (2020b). Circular No. 3 of 2020: Containment/management of COVID-19 for schools and school communities. https://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/Documents/Publications/Circular%20on%20change%20of%20school%20dates%20COVID19.pdf?ver=2020-03-16-132144-460.

Department of Basic Education. (2020c). Annual Performance Plan 2020/21. DBE, Pretoria. https://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/Documents/Reports/Revised%20202021%20APP%20July%202020.pdf?ver=2020-08-26-095030-437

Department of Basic Education, (2020d). Statement delivered by the Minister of Basic Education, Mrs Angie Motshekga, at a media briefing March 9, 2020. https://www.education.gov.za/Newsroom/MediaReleases/tabid/347/ctl/Details/mid/9134/ItemID/7910/Default.aspx

Department of Basic Education. (2011). National Curriculum Statement (NCS): Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS). Further Education and Training Phase: Grades 10-12. Government Printer.

Fataar, A., & Badroodien, A. (2020). Editorial notes. Southern African Review of Education, 26 (1), 1-5. [ Links ]

Government Gazette. (2020a). Department of Basic Education Notice 302 of 2020. http://www.gpwonline.co.za/Gazettes/Gazettes/43372_29-5_BasicEdu.pdf

Government Gazette. (2020b). Department of Water and Sanitation. Regulation 10(8) of the Regulations issued under section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act, 2002 (Act No. 57 of 2002). https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202004/43231gon464.pdf

Levitt, H. M., Motulsky, S. L., Wertz, F. J., Morrow, S. L., & Ponterotto, J. G. (2017). Recommendations for designing and reviewing qualitative research in psychology: Promoting methodological integrity. Qualitative Psychology, 4 (1), 2-22. [ Links ]

Lopez, L., & Whitehead, D. (2013). Sampling data and data collection in qualitative research. In Z. Schneider & D. Whitehead (Eds.), Nursing and midwifery research: Methods and appraisal for evidence-based practice (4th ed.) (pp.123-140). Elsevier-Mosby.

Lugg, C. A., & Murphy, J. P. (2014). Thinking whimsically: Queering the study of educational policy-making and politics. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 27(9), 1183-1204. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2014.916009 [ Links ]

Maxwell, J. A. & Chmiel, M. (2014). Notes towards a theory of qualitative data analysis. In in U Flick (Ed.) Sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 21-34). SAGE.

Mohajan, H. (2018). Qualitative research methodology in social sciences and related subjects. Journal of Economic Development, Environment and People, 7(1), 23-48. [ Links ]

Mohohlwane, N., Taylor, S., & Shepherd, D. (2020, July). COVID-19 and basic education: Evaluating the initial impact of the return to schooling. NIDS-CRAM (National Income Dynamics - Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey) Report Wave 2, July. https://cramsurvey.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/11.-Mohohlwane-N.-Taylor-S-Shepherd-D.-2020-COVID-19-and-basic-education-Evaluating-the-initial-impact-of-the-return-to-schooling.pdf

Mumtaz, A., David, M. K., & Ching, L. L. (2013). Using the Key Informants Interviews (KIIs) technique: A social sciences study with Malaysian and Pakistani respondents. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/273636636_Using_the_Key_Informants_Interviews_KIIs_Technique_A_Social_Sciences_Study_with_Malaysian_and_Pakistani_Respondents

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. (2020, 21 October). The new idea of Africa in the context of COVID-19. Accord. https://www.accord.org.za/analysis/the-new-idea-of-africa-in-the-context-of-covid-19/

Nicoll, K., & Edwards, R. 2004. Lifelong learning and the sultans of spin: Policy as persuasion? Journal of Education Policy, 19(1), 43-55. [ Links ]

Parker, R., Morris, K., & Hofmeyr, J. (2020). Education, inequality and innovation in the time of Covid-19. JET Education Services.

Sayed, Y., & Singh, M. (2020). Evidence and education policy making in South Africa during Covid-19: Promises, researchers and policymakers in an age of unpredictability. Southern African Review of Education, 26(1), 20-39. [ Links ]

Taylor, N. (2020). School lessons from the Covid lockdown. Southern African Review of Education, 26(1): 148-166 [ Links ]

UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization), UNICEF (United Nations Children's Fund), World Bank, World Food Programme, & UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) (2020, June). Framework for reopening schools. https://www.unicef.org/sites/default/files/2020-06/Framework-for-reopening-schools-2020.pdf

Vally, Z. (2019, March 19). Education inequality: The dark side of SA's education system. The Daily Vox. https://www.thedailyvox.co.za/educational-inequality-thedark-side-of-sas-education-system-2/

Van der Bergh, S. (2020, July 14). COVID-19 school closures in South Africa and their impact on children. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/covid-19-school-closures-in-south-africa-and-their-impact-on-children-141832

Van der Bergh, S., & Spaull, N. (2020, June). Counting the cost: COVID-19 school closures in South Africa and its impact on children. Stellenbosch University, https://resep.sun.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Van-der-Berg-Spaull-2020-Counting-the-Cost-COVID-19-Children-and-Schooling-15-June-2020-1.pdf

Vorster R. (2020, May 5). The challenges of safety and some potential solutions (Part two). Daily Maverick. https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2020-05-05-part-two-the-challenge-of-safety-and-some-potentialsolutions/

World Bank Group. (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on education financing. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/33739/The-Impact-of-the-COVID-19-Pandemic-on-Education-Financing.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Young M. D., & Diem, S. (2018). Doing critical policy analysis in education research: An emerging paradigm. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325908605_Doing_Critical_Policy_Analysis_in_Education_Research_An_Emerging_Paradigm

Received: 14 March 2021

Accepted: 23 September 2021