Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of Education (University of KwaZulu-Natal)

On-line version ISSN 2520-9868

Print version ISSN 0259-479X

Journal of Education n.81 Durban 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2520-9868/i81a07

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Analysing the hegemonic discourses on comprehensive sexuality education in South African schools

Lindokuhle Ubisi

Unit 3-49, Department of Educational Psychology, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa lindokuhle.ubisi@up.ac.za https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5228-6686

ABSTRACT

Despite the mixed public responses, the South African Department of Basic Education decided to issue its detailed comprehensive sexuality education scripted lesson plans for testing in schools. I conducted a desktop review by searching for digital newspapers in the online archive Sabinet References using six key terms such as "comprehensive sexuality education", "schools", and "South Africa." In total, I retrieved 128 newspaper articles and selected 83 for a Foucauldian discourse analysis underpinned by governmentality theory. The newspapers reported on marches, letters, and press conferences from various stakeholders such as parents, learners, teachers, and other social figures. Some stakeholders were in favour of the rollout while others were against, but of interest was the seemingly neutral position of those whose reporting was presented in a balanced, non-biased manner. In this paper, I aim to make sense of this neutrality in addition to the views in favour of and against the rollout while suggesting implications for educational settings.

Keywords: comprehensive sexuality education, digital newspaper articles, public discourse analysis, rollout, scripted lesson plans, South Africa

Introduction

In spite of the conflicting public reactions surrounding its readiness, public consultation and policy-making, the South African Department of Basic Education (DBE) declared plans in 2015 to pilot its comprehensive sexuality education1 (CSE) scripted lesson plans (SLPs) in five of its nine national provinces (DBE, 2019). The DBE (2018) used national policy such as the Constitution of South Africa Act of 1996 and Children's Act 38 of 2005 as well as curriculum policy including the National policy on the prevention and management of learner pregnancy in schools and integrated school health policy to back up the rollout. Based on its content and contextual appropriateness, parents, teachers, learners, and other social figures expressed differing viewpoints in support of and in opposition to the piloted rollout (Bhana et al., 2019; Francis & DePalma, 2014a; Mayeza & Vincent, 2019; Mudhovozi et al., 2012; Swanepoel, 2020). Both local and international literature feature comparisons and offer points in favour of and against the rollout of CSE in schools (see Aggleton et al, 2011; Braeken & Cardinal, 2008; Jones, 2020; Kendall, 2013; and the collected chapters in Sundaram & Sauntson, 2016). However, there are those individuals who remain neutral towards the rollout for reasons that have not been previously explored in extant research.

Furthermore, there has been an increase in the readily available news items in online digital platforms as Newman et al. (2015) have noted. Given the internet and various technological devices, online newspapers and social networking sites are able to circulate information instantly around the world, using news feeds as Oeldorf-Hirsch & Sundar (2015) have reminded us. Local and international research indicates that more people, of whom most are young, rely on the internet and other online sources for information about current affairs. Not surprisingly, the research also indicates that many of these individuals become more susceptible to fake news, which, in turn, influences their behaviour and conduct (Greer & Yan, 2011; Moosa, 2020; Rodny-Gumede, 2012). As Luu (2019) has stated, "Fake news can be deliberately manipulated by those with vested interests to shape and frame and control public opinions, which result[s] in the problematic actions (and inaction) on existential issues, such as climate change or human rights" (para. 7). However, it is not only fake news with which the general public has to grapple. For example, there is national legislation proclaimed by government such as the rollout of CSE SLPs in schools which can elicit all kinds of reactions, including panic, outcry, and approval, or result in general apathy. However, Foucault (1979/1991), in his theory of governmentality, maintained that government and other prominent institutions may formulate certain governing rationalities so as to influence the public to partake in action related to citizenship.

Theoretical framework: Governmentality theory

For Levenberg (2012), Foucault's (1979) theory of governmentality referred to

[t]he ensemble formed by the institutions, procedures, analyses and reflections, the calculations and tactics that allow the exercise of this very specific albeit complex form of power, which has as its target population, as its principal form of knowledge political economy, and as its essential technical means apparatuses of security. (para. 4)

Foucault (1981/1997) as I have explained elsewhere (Ubisi, 2020) departs from the capitalist false notion of autonomous, rational decision-making, contending that individuals are subjected to rigid forms of disciplinary power and knowledge. For example, individuals may believe that their ideologies are formed separately from media influence. Instead, Foucault maintained that individuals create knowledge alongside existing discourses and social norms, which, in turn, influences their own and other's behaviours, decision-making, and conduct. In other words, the theory of governmentality looks at how subtle, macro-mechanisms (for example, government rationalities) and micro control apparatuses (a fallacious belief in a self-regulating subject) aimed at governing individuals, in turn influence their own and other's behaviour and conduct (Foucault, 1979/1991). In essence, governmentality considers "who can govern; who can be governed; what is to be governed; and how" (Walters & Haahr, 2005, p. 290).

In this paper, I examine the hegemonic public discourses reflected in online digital newspaper articles surrounding the rollout of CSE SLPs in South African schools. I employ a Foucauldian discourse analysis, underpinned by governmentality theory, to make sense of the apparent neutral stance that emerged. First, I consider what both national and curriculum policy documents such as the Children's Act and National policy on the prevention and management of learner pregnancy in schools say about CSE and its rollout. Then, I discuss the implementation of CSE in South African schools. I go on to discuss the public's response to the rollout while turning to the social psychology of decision-making to explore possible reasons in an attempt to understand the apparent neutrality.

National and curriculum policy surrounding the rollout of comprehensive sexuality education in South African schools

The Constitution stands as a national legislative framework that upholds the rights and responsibilities of its citizens in relation to the state and its governmental bodies. The right to sexual and reproductive health services and information can be identified in the Bill of Rights under Section 27(1)(a) of the Constitution. However, the Constitution is not clear about the age of consent when it comes to services and procedures such as accessing age- appropriate CSE, preventative contraceptives, and the termination of pregnancy. The Children's Act 38 of 2005 (as amended by the Children's Amendment Act, No. 41 of 2007) protects the rights of children and makes provision for the physical, emotional, psychological, social, sexual, and legal wellbeing of all children. For example, Chapter 2, Section 13, taking their age, maturity and stage of development into consideration, states that all children, including children living with disabilities have the right to access age- appropriate CSE in an accessible format. In addition, Part 3 of Chapter 7 in the Children's Act, also states that a child may consent to medical services, such as being prescribed contraceptives and having a pregnancy terminated as early as 12 years of age, given their maturity and understanding of the associated risks of these treatments and procedures.

The National policy on the prevention and management of learner pregnancy in schools (DBE, 2018), together with the Integrated school health policy (2012) remain part of the DBE's strategic plan to ensure the availability of condoms and contraceptives along with putting in place in schools by 2022, a referral system that includes testing and treatment for TB, HIV, and sexually transmitted diseases. The National policy on the prevention and management of learner pregnancy in schools, which was extended for public comment until 31 July 2018, is intended to extend the sexual and reproductive services for learners in schools (DBE, 2018). These services include access to male and female condoms and oral contraceptives, and options for the termination of pregnancy services to learners aged 12 and above, as determined by the level of inquiry or need. The policy also makes provision for counselling and support, instructions for systematic management and implementation, as well as age- appropriate, culturally relevant and human rights based CSE. According to the policy, the aim of CSE is to equip learners with appropriate knowledge and skills to enable them to make mindful and healthy choices about relationships and the expression of their sexuality. This includes providing practical information based on scientific evidence that is presented in a non-judgemental manner (DBE, 2018).

The emergence of comprehensive sexuality education in South African schools

According to the DBE (2019), the CSE curriculum has been integrated into the school curriculum in subjects such as Life Orientation and Life Skills since 2000. In other words, apparently, CSE has been part of the South African curriculum for almost 20 years. The introduction of CSE into the South African curriculum was a response to the daily challenges that learners face in terms of sexual and reproductive health services, care, and education, according to the DBE (2019). A significant number of young people, especially in the age range of 14 to 24, are increasingly experiencing early sexual debut, being exposed to pornography, and enacting non-compliance when it comes to condom use, and to TB and HIV testing. They are also making use of the available prevention measures to prevent unplanned pregnancy (DBE, 2019; Statistics South Africa, 2018; UNESCO, 2018). Female students who fall pregnant often drop out of school with limited skills and few career opportunities (DBE, 2019). Some may find themselves in poverty and turning to prostitution to survive which may, in turn, leave them susceptible to risks such as contracting sexually transmitted diseases (Statistics South Africa, 2018; UNESCO, 2018). The DBE (2019) has maintained that CSE provides an opportunity for young people to acquire the knowledge, skills, and resources that will help them avoid engaging in risk-taking behaviours and build, instead, positive constructions of gender, sexuality, and the dynamics of relationships. However, whether CSE was ready to be implemented and whether there had been sufficient consultation with experts was debatable (Bhana et al. 2019; Francis, 2019a, 2019b; Msibi, 2015; Ngabaza & Shefer, 2019; Shefer & Macleod, 2015).

According to Bhana et al. (2019), the South African landscape is characterised by specific historical, socio-economic, and cultural differences between and among its learners and their parents (or guardians) and teachers. This means that some of the recommendations offered such as the valuing of compulsory heterosexuality over sexual diversity, for example, may differ from the expectations of learners, parents, and the teachers involved. This is true, too, of the values emphasised in relation to education about sexuality and relationships such as, for example, the insistence on sexual abstinence rather than on informed decision-making. Young people have reported that CSE is presented mostly from an abstinence focused (Msutwana & de Lange, 2017), disease-ridden (Mayeza & Vincent, 2019) and heteronormative framework (Reygan, 2016). They have also noted that CSE is often offered by embarrassed (Pound et al., 2016), unconfident (Francis & DePalma, 2014b) and poorly trained (Wood, 2009) teachers. For most South African parents and teachers, the morality behind the social construction of sex, gender, sexuality, and the teaching of sexuality education has been informed by a Judeo-Christian worldview (Bhana et al., 2019). This moral framework, in emphasising an abstinence approach based on heteronormativity, presents a specific culturally and religiously conservative approach to sexuality as Shefer and Macleod (2015) have observed.

As a result, the current CSE curriculum has been criticised for its failure to engage with the changes in young people's evolving sexual identities (Shefer & Macleod, 2015), the wide range of sexual practices of young people (Mayeza & Vincent, 2019), and the need of learners of minority (a)sexual identification groups to be accepted in schools (Ubisi, 2020). However, according to Bhana et al. (2019), Ngabaza and Shefer (2019) and Swanepoel (2020), CSE does address other concerns such as the recognition of young people as sexual beings, the importance of increasingly safe sexual practices, and the problems inherent in the culture of sexual violence in schools. It affirmed some values about sex and notes the lack of parental involvement in education that deals with sex, HIV, and intimate relationships. Scholars (Bhana et al., 2019; Francis, 2017; Msibi, 2015) have maintained that if CSE could be positioned within a framework based on human rights and gender and sexual justice, it has the potential to alleviate the effects of gender inequality, the supremacy of heteronormativity, and the promotion of sexual justice in the education system (Bhana et al., 2019; Ngabaza & Shefer, 2019; Shefer & Macleod, 2015).

Public reaction towards the rollout of comprehensive sexuality education in schools

According to Foucault (1976/1990), the sexuality of children has been an intriguing yet socially sanctioned subject by those in positions of power. He theorised in the "pedagogization of children's sex" (1976/1990, p. 104) that powerful institutions, namely the state, church, and family unit, deemed what was thought to be the highly sexual nature of children's sexuality to be dangerous, and, therefore, in need of monitoring and control. Foucault suggested that, in response to this belief, these powerful institutions created discourses of children as innocent subjects who should be kept ignorant of any exposure that may might sexualise them into early sexual debut. For Philo (2011),

In his vision, children below some uncertain age (pre-teenage?) are regarded as sexually innocent, entirely without bodily urges and passions of a 'sexual' nature, so much so that any attempt to discuss them as 'sexual' beings, or indeed to broach the issue of 'sex' with them, is met with widespread squeamishness if not outcry. (p. 124)

Despite the differences in time and context, many South Africans echo Foucault's sentiments about the protection of children's supposed innocence and take a stand against the rollout of CSE SLPs in schools (Swanepoel, 2020). At the crux of these objections is debate about the implementation of CSE in schools given the lack of readiness of the CSE SLPs and the extent of public consultation, as the chapters in Sundaram and Sauntson (2016) have attested. For one, as Jones (2020) has pointed out, parents and religious figures have contended that, given the differences in cultural taboos and the various decrees of religious observation, the timing of the exposure to children of either abstinence-only or CSE-based sex education should be at their discretion. Also, parents along with religious and civil organisation spokespeople have maintained that governmental bodies like the DBE have engaged in limited consultation with the general public (Swanepoel, 2020). Instead, these stakeholders have expressed feeling that government departments tend to rely on decision-making by global intergovernmental agencies like the United Nations (UN) that do not consider the diverse African landscape (see the chapters in Sundaram and Sauntson, 2016). At the same time, the DBE (2019) has insisted that national and curriculum policies are not adapted in isolation but with the assistance of an advisory committee panel made up of professional and civil bodies. The DBE (2019) has also claimed that CSE is not sex education in which individuals are taught how to have sex. In response to critics against CSE, Basic Education Minister, Angie Motshekga stated, "There's adequate information that says if you teach children sexual education, you're about to educate them about sexuality, not sexualise them" (Mokone, 2019, para. 12). In fact, the DBE (2019) maintains that CSE is a holistic, value-driven strategy meant to prepare learners to make conscious, healthy decisions about their relationships and sexuality.

Up to this point, there is limited local and international research that suggests the prevalence of a neutral stance towards the CSE rollout. To understand the possible reasons for individual decision-making in social contexts, it is useful to consider theory from other fields such as the social psychology of decision-making that explores the steps and processes taken by individuals and groups in making decisions in social contexts. Based on research using simulated scenarios, experts in this field have suggested theories that explain decision-making strategies when it comes to prominent issues (Ajzen, 1996; Branscombe & Baron, 2016; Minda, 2015). For example, individuals may react to national protocols out of a sense of their citizenship duty in a manner that demonstrates acquiescence, however reluctantly, or as a way of showing obedience to authority in an act of conformity, depending on the required action on their part as well as the perceived consequences (Branscombe & Baron, 2016). Some individuals may employ a decision-making strategy aligned with contrariness or rebelliousness toward national priorities such as, for example, a nation-wide vaccination requirement. According to Branscombe and Baron (2016), contrariness results from an unwillingness to share a similar view with a perceived oppressive authority figure. Then, again, some individuals may openly remain on the fence about national agendas such as a vaccination rollout based on feelings of general apathy or the unwillingness to challenge power (Minda, 2015). For example, the individual may believe the government is going to do what it wants to do anyway. However, even in these cases, while an individual may state socially an apparently neutral stance, their personal ideology may demonstrate contradictory beliefs towards the certain issue (Tajfel, 1978).

Methodology

Sampling and data collection

I conducted a desktop review by searching through digital newspaper articles from 2015 to 2019 on the online archive SA Media on Sabinet References. I used the six broad key terms of "comprehensive sexuality education", "sex education", "sexual education", "sex ed", "schools" and "South Africa". The newspapers reported on marches and organisational positions, and published letters, commentaries, opinion pieces, reports of press conferences a; well as pieces on health communication from various stakeholders such as parents, teachers, learners, religious figures, advocates, and civil and governmental organisations. Of the128 online digital newspaper articles that were retrieved, I selected 83 for the final analysis (see Table 1). The retrieved newspaper articles from newsrooms such as Pretoria News, Cape Times, Mail and Guardian, and The New Age reflect those that made it beyond editorial censorship and represented the journalists' position, and, to a certain extent, the editorial position, too, of the newsroom at the time. I based the selection criteria for the final analysis on (1) whether the online digital newspaper article responded to or created a discourse about the rollout of CSE in schools; (2) if it was published between the years 2015 and 2019; and (3) the newsroom was South African based, or the report reflected a South African context.

Data analysis

I captured the online digital newspaper articles and prepared them in an Excel spreadsheet for analysis. I entered the data according to each subsequent year (from 2015 to 2019) indicating the article name, its author, year of release, newspaper, and page number. Following the direction of Babbie and Mouton (2001), I conducted a thematic analysis based on the articles' condensed meaning units, codes, categories and identified theme(s). All in all, I identified three themes with their supporting discourses and analysed them using Foucauldian discourse analysis. This kind of analysis is concerned with how an individual's worldview is shaped by how language is used and how relations in power are exercised by the individual in interactions with social institutions (Arribas-Ayllon & Walkerdine, 2008). In particular, this discourse analysis was used to identify hegemonic discourses evident in the public voice as shaped by language and authority bodies towards the rollout of CSE in schools. In this case, in line with Ferreirinha and Raitz (2010), I considered online media platforms as authority bodies that use language and forms of representation to persuade the consumers to accept or reject a certain viewpoint.

Findings and discussion

Following a public discourse analysis of online digital newspaper articles surrounding the rollout of CSE SLPs, my findings suggest that a number of hegemonic discourses were employed by some stakeholders in favour of and against the rollout (see Table 2). As the years go by from 2015 to 2019, most of the views show a particular trend towards being in favour of the rollout, with a gradual increase of a seemingly neutral stance towards it (see Table 1).

Dominant public discourses in favour of the rollout of CSE in South African school

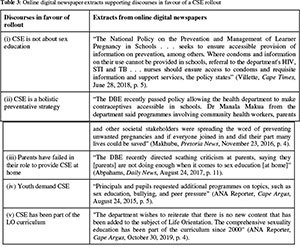

Supporting extracts from online digital newspapers that demonstrate dominant public discourses in favour of a CSE rollout in South African schools are indicated in Table 3 below. Consistent with the available literature, the discourses remain in line with the positions of scholars such as Bhana et al. (2019), Ngabaza and Shefer (2019) and Swanepoel (2020) who contend that CSE is a holistic strategy rather than just about sex education. Intergovernmental agencies, such as the UN (UNESCO, 2018), and some scholars (Francis, 2019b; Shefer & Macleod, 2015) have maintained that CSE is a broad curriculum intended to generate early positive values in schooling environments such as the acceptance of sexuality diversity. These discourses corroborate the findings in some literature that parents have failed to offer CSE at home for reasons such as discomfort in relation to talking about issues of sexuality (Mudhovozi et al., 2012), and that young people require more open communication about less prioritised topics such as dating within same-sex relationships (Mayeza & Vincent, 2019).

I use the tenets of governmentality theory (Foucault, 1979/1991) here to examine sources of decision-making, specifically how rationalities have been used to persuade individuals, as well as how these governing rationalities influence, in turn, our own behaviours and conduct and that of others. As Foucault (1981/1997, p. 291) put it, the

subject constitutes itself in an active fashion through the practices of self, these practices are nevertheless not something invented by the individual himself [sic]. They are models that he finds in his culture and are proposed, suggested, imposed upon him by his culture, his society and his social group.

Since online news platforms have become a readily available source of information, especially for young people, more pressure can be exerted by social institutions such as governmental bodies to influence citizenship to move towards particular forms. In this case, the supporting extracts from the newspaper articles in Table 3 show that rationality from governmental departments such as the DBE's policy outlines, health communications and the reassurance given to the public may have been employed during the process of policy-making to influence the public to support the rollout. Such governing mentality raises questions, identified by opponents of the CSE rollout, about how extensively governmental departments conduct their public consultations to include a variety of public views.

In terms of the implications for teacher education, policy, and the teaching and learning of CSE, the extracts below show that despite the DBE's reiterated objections, CSE is considered widely by the public as sex education. This means that to ensure inclusivity in both schooling environments and broader social contexts, teacher education needs to incorporate pedagogy and curriculum knowledge which emphasises that CSE is a broad curriculum that is scientifically-based (UNESCO, 2018), age- appropriate (DBE, 2019) and that it is based within an anti-oppressive, sexual justice and human rights based framework (Shefer & Macleod, 2015). The DBE needs to clarify, also, the implications of policy such as the Children's Act and National policy on the prevention and management of learner pregnancy in schools for stakeholders in communities such as parents, teachers, community leaders, and learners to secure the involvement and cooperation of the broader community that will ensure the effective implementation of CSE in schools. In terms of the teaching and learning of CSE, the findings suggest that more young people and principals seem to welcome the teaching of CSE (Mayeza & Vincent, 2019).

Dominant public discourses against the rollout of CSE in South African schools

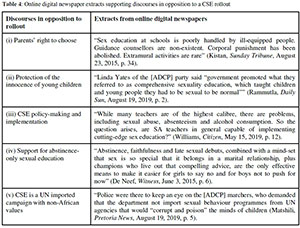

Table 4 below shows corroborating extracts from online digital newspapers that demonstrate hegemonic discourses in opposition to the rollout of CSE SLPs in South African schools. In line with local and international research, the discourses support contentions by parents that it is their right to choose the timing and exposure of their children to any sexuality education, especially when it comes to protecting their innocence (Jones, 2020; Kendall, 2013; Sundaram & Sauntson, 2016). Existing literature supports discourses opposing a CSE rollout based on the DBE's lack of readiness and consultation and its untimely implementation, given, as mentioned above, that CSE is presented by embarrassed (Pound et al., 2016), unconfident (Francis & DePalma, 2014b), and poorly trained teachers (Wood, 2009). However, there is limited literature that criticises the discourse in identifying CSE as a UN import that fails to take into account the diverse African landscape (see the collected chapters in Sundaram and Sauntson, 2016).

According to governmentality theory, disciplinary knowledge from social and academic institutions such as psychology has driven socio-medical and cultural discourses about how parents and teachers should understand the sexuality of children (Foucault, 1976/1990). Foucault's (1979/1991) theory of governmentality urges us to consider how the discursive use of language by disciplines such as medicine and religion, as indicated in the extracts below, provide reasons for the opposing stance when it comes to addressing children's sexuality. For example, at some points in history, talking about children's sexuality was considered a moral taboo (Foucault, 1976/1990). Foucault's theorisation of the "pedagogization of children's sex" (Foucault, 1976/1990, p. 104), a social construction that children are innocent and need to be kept ignorant of sex and away from any sexual exposure lest they become sexualised into early sexual debut, used to be an accepted worldview endorsed by early institutional bodies, including the medical profession. According to Foucault (1976/1990), governmentality through disciplinary powers needs to be critically examined. In this case, the extracts reveal how religion has exerted its influence on the maintaining of abstinence-only approaches. Foucault maintained that it is necessary to reveal any self-serving interests of power so, here, we need to ask why and how religious belief defines what counts as normal sexuality.

In terms of the consequences of these findings for teacher education, policy, and the teaching and learning of CSE, it is still clear that certain religious views on sexual morality (e.g. that children are innocent and should be kept pure) inform how the public sees sexuality and relationship education in schools. Given this, it is teacher education that should be seen as crucial to reinforcing the values and interpretive framework of constitutional democracy that allows for the expression of many worldviews, including those of religious bodies and sexual minorities. For example, teacher education needs to prepare teachers to let go of the fear that the teaching of sexuality diversity in schools will sexualise youth in any way. Teachers need to learn that the teaching of sexuality diversity is meant to queer what are considered to be normal gender constructions or views on sexuality (Shefer & Macleod, 2015), as well as to destabilise compulsory heterosexuality (Francis, 2017) the belief in which often leads to oppression like victimisation, homophobia, and transphobia in schooling environments and society more broadly. The integration of national policy in relation to the Constitution needs to be foregrounded in the teaching and learning of CSE to engender the values of creating inclusive schooling environments and social contexts for all learners, including those of religious and sexual minorities.

Understanding the neutrality towards the rollout

Extracts are offered from online digital newspapers supporting discourses of seeming neutrality towards the rollout of CSE SLPs in schools, as indicated in Table 5. The apparent neutrality was determined by the newspaper's balanced, non-biased reporting about the rollout. I have employed governmentality theory to suggest how individuals create knowledge, identities, and agency alongside existing discourses and social norms that, they use, in turn, to regulate their own and other's behaviour (Foucault, 1979/1991). However, a shortcoming of governmentality theory is the recognition that individuals are capable of forming new experiences from their everyday interactions and observations that require alternative explanations outside existing discourses related to social norms. For example, the supporting extracts suggest that neutrality may be seen in the ambivalent feelings expressed by principals about the effectiveness of a CSE rollout in their schools.

To further understand the neutrality discourse, one can also see in operation journalistic ethics that require journalists to represent equally both sides of a certain issue, since reporting in a neutral, non-biased manner is what journalists are trained to do (see the chapters in McBride & Rosenstiel, 2013). However, there are newsroom dynamics based on editorial policies that reinforce censorship of certain content that might affect a journalist's ability to write freely. There is a new need to recognise that non-biased reporting creates a neutral stance from which the public is invited to consider new outlooks, in this case, on CSE, regardless of personal secular and/or religious perspectives. Then again, some individuals, based on their personal ideology, may be neutral when it comes to supporting national priorities. For example, some individuals may withdraw into a state of general apathy (feeling that they and their decisions do not matter when it comes to policy making), while others may take the stance of being unwilling to challenge authority (Branscombe & Baron, 2016).

The lesson that could be drawn for teacher education, policy, and the teaching and learning of CSE is that both opponents and supporters of the CSE rollout might have something to learn from each other. The DBE might need to acknowledge counter-normative stances from religious leaders and parents' concerns regarding the CSE curriculum. A public engagement inviting wider approaches from secular and religious perspectives would allow for the expansion of a diverse approaches and worldviews towards the teaching of CSE in schools. However, as it stands, the DBE has maintained that parents can come up with their own sex lessons that will be considered at policy level. The DBE should be proactive in coming up with alternative strategies in cases where offering CSE has not been effective, instead of promoting CSE as the magic bullet without acknowledging its shortcomings. Then again, a neutral stance should also be welcomed in the teaching and learning of CSE by multiple stakeholders in the education sector since this advances the enactment of a constitutional democracy.

Conclusion

In this paper, I aimed to explore hegemonic discourses surrounding the rollout of CSE SLPs in South African schools. I focused on online digital newspapers because of the reliance by young people on online sources for news (Greer & Yan, 2011; Moosa, 2020; Rodny-Gumede, 2012). I uncovered a neutral position, in addition to those in favour of and in opposition to the rollout. I used Foucault's (1979/1991) governmentality theory to analyse the data. The findings suggest that social institutions such as the media, government departments, and religious leaders may influence individuals' responses to, decision-making about, and behaviour towards, the rollout. There may be, however, those individuals who seemingly remain neutral towards the rollout. The findings in this study point to feelings of ambivalence and the lack of reliable evidence supporting the success of a CSE rollout. The reported increase in teenage pregnancies, despite learners being offered CSE in schools, also cast doubts on its effectiveness. Further calls to revisit new approaches from secular and religious perspectives show uncertainty by some individuals with regard to the current state of the CSE programme. Applying theoretical explanations from the field of the social psychology of decision-making, other possible reasons suggest that neutrality towards the rollout may originate from feelings of general apathy or an unwillingness to challenge authority or take a stand (Branscombe & Baron, 2016).

One of the limitations of this study is that not all newsroom publishers upload their articles on the public database Sabinet References. In addition, the newspapers also cannot be said to reflect the public's actual responses, given that they are also written from a journalistic point of view, and are possibly influenced by editorial policy at the time of writing. The findings of this study, therefore, cannot be said to be representative of the various views across the country. Future research could use autobiographical accounts and/or a collection of both digital and hard copy newspaper articles to gather a more representative view.

References

Abpahams, M. (2017). How to have that talk with your child. Daily News, August 24. https://www.iol.co.za/lifestyle/family/parenting/how-to-have-the-talk-with-your-child-10920089

Aggleton, P., Yankah, E., & Crewe, M. (2011). Education and HIV/AIDS-30 years on. AIDS Education and Prevention, 23(6), 495 - 507. [ Links ]

Ajzen, I. (1996). The social psychology of decision making. In E. T. Higgins & A. W. Kruglanski (Eds.), Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles (pp. 297 - 325). Guilford Press.

ANA Reporter. (2015). Anti-drug strategy to be expanded. Cape Argus, August 24. https://www.pressreader.com/search?query=Principals%20and%20pupils%20requested%20addition al%20programmes%20on%20topics%2C%20such%20as%20sex%20ed ucation%2C%20bullying%2C%20and%20peer%20pressure&languages=en&g roupBy=Language&hideSimilar=0&type=1&state=1

ANA Reporter. (2019). Department defends sex education curriculum. Cape Argus, October 30. https://www.pressreader.com/south-africa/cape-argus/20191030/281595242325960

Arribas-Ayllon, M., & Walkerdine, V. (2008). Foucauldian discourse analysis. In C. Willig & W. Stainton-Rogers (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research in psychology (pp. 91 - 108). SAGE.

Babbie, E., & Mouton, J. (2001). The practice of social research: South African edition. Oxford University Press Southern Africa.

Bhana, D., Crewe, M., & Aggleton, P. (2019). Sex, sexuality and education in South Africa. Sex Education, 19(4), 361 - 370. [ Links ]

Braeken, D., & Cardinal, M. (2008). Comprehensive sexuality education as a means of promoting sexual health. International Journal of Sexual Health, 20(1/2), 50 - 62. [ Links ]

Branscombe, N. R., & Baron, R. A. (2016). Social psychology, Global edition (14th ed.). Pearson Education Limited.

De Neef, R. (2015). Condoms at school disastrous. Witness, June 3. https://reference-sabinet-co-za.uplib.idm.oclc.org/webx/access/samedia/2015/06/WITNS20150603/WITNS201506036_030.pdf

Department of Basic Education. (2018). National policy on prevention and management of learner pregnancy in schools: Comments invited: Extension of deadline for comments. https://www.gov.za/documents/national-policy-prevention-and-management-learner-pregnancy-schools-comments-invited

Department of Basic Education. (2019). Comprehensive Sexuality Education. https://www.education.gov.za/Home/ComprehensiveSexualityEducation.aspx

Discussion needed on sex education. (2019). Cape Argus, August 22. https://reference-sabinet-co-za.uplib.idm.oclc.org/webx/access/samedia//2019/08/ARGUS20190822/ARGUS201908227_162.pdf

Ferreirinha, I. M. N., & Raitz, T. R. (2010). Relations of power in Michel Foucault: Theoretical reflections. Revista de Administração Pública, 44(2), 367 - 383. [ Links ]

Foucault, M. (1990). The history of sexuality: Volume 1: The will to knowledge. New York: Vintage Books. (Original work published 1976) [ Links ]

Foucault, M. (1991). Governmentality. In G. Burchell, C. Gordon, & P. Miller (Eds.), The Foucault Effect (pp. 87-104). University of Chicago Press. (Original work published 1979)

Foucault, M. (1997). The ethics of the concern for self as a practice of freedom. Ethics: Subjectivity and truth, 1, 281-301. (Original work published 1981) [ Links ]

Francis, D. (2019a). 'Keeping it straight,' What do South African queer youth say they need from sexuality education? Journal of Youth Studies, 22(6), 772 - 790. [ Links ]

Francis, D. A. (2019b). What does the teaching and learning of sexuality education in South African schools reveal about counter-normative sexualities? Sex Education, 19(4), 406 - 421. [ Links ]

Francis, D. A. (2017). Homophobia and sexuality diversity in South African schools: A review. Journal of LGBT Youth, 14(4), 359 - 379. [ Links ]

Francis, D. A., & DePalma, R. (2014a). Teacher perspectives on abstinence and safe sex education in South Africa. Sex Education, 14(1), 81 - 94. [ Links ]

Francis, D. A., & DePalma, R. (2014b). 'You need to have some guts to teach': Teacher preparation and characteristics for the teaching of sexuality and HIV/AIDS education in South African schools. Sahara-J: Journal of Social Aspects of Hiv/Aids, 12(1), 30 -38. [ Links ]

Greer, J. D., & Yan, Y. (2011). Newspapers connect with readers through multiple digital tools. Newspaper Research Journal, 32(4), 83 - 97. [ Links ]

Jones, T. (2020). Sexuality: Australian schools' sexuality wars. In T. Jones (Ed.), A Student-centred Sociology of Australian Education (pp. 129 - 183). Springer.

Kendall, N. (2013). The sex education debates. University of Chicago Press.

Kistan, C. (2015). Sex legislation change reflects moral decay. Sunday Tribune, August 23. https://www.pressreader.com/south-africa/sunday-tribune-south-africa/20150823/282643211298515

Levenberg, L. (2012). Foucault - On governmentality. https://lewislevenberg.com/1053

Luu, C. (2019). The incredibly true story of fake headlines. Lingua Obscura. https://daily.jstor.org/the-incredibly-true-story-of-fake-headlines/

Makhubu, N. (2016). Preventing unwanted pregnancies vital. Pretoria News, November 23. https://www.pressreader.com/south-africa/pretoria-news/20161123/281608125031038

Mayeza, E., & Vincent, L. (2019). Learners' perspectives on Life Orientation sexuality education in South Africa. Sex Education, 19(4), 472 - 485. [ Links ]

McBride, K., & Rosenstiel, T. (Eds.). (2013). The new ethics of journalism: Principles for the 21st century. CQ Press.

Minda, J. P. (2015). The psychology of thinking: Reasoning, decision-making and problem-solving. SAGE.

Mokone, T. (2019). "We have to talk about these things to save our children": Motshekga defends sex-ed classes. TimesLive,November 20. https://www.timeslive.co.za/politics/2019-11-20-we-have-to-talk-about-these-things-to-save-our-children-motshekga-defends-sex-ed-classes/

Moosa, M. (2020). News in the COVID-19 crisis: Where do South Africans get their news, and is it trustworthy? Findings from the 2019 South African Reconciliation Barometer. Africa Portal. https://www.africaportal.org/publications/news-covid-19-crisis-where-do-south-africans-get-their-news-and-it-trustworthy-findings-2019-south-african-reconciliation-barometer/

Msibi, T. (2015). The teaching of sexual and gender diversity issues to pre-service teachers at the University of KwaZulu-Natal: Lessons from student exam responses. Alternation, 12, 385 - 410. [ Links ]

Msutwana, N., & de Lange, N. (2017). "Squeezed oranges?" Xhosa secondary school female teachers in township schools remember their learning about sexuality to reimagine their teaching sexuality education. Journal of Education, 69, 211 - 236. [ Links ]

Matshili, R. (2019). ACDP march against sex education plan. Pretoria News, August 19. https://www.iol.co.za/pretoria-news/acdp-march-against-sex-education-plan-30970782

Mudhovozi, P., Ramarumo, M., & Sodi, T. (2012). Adolescent sexuality and culture: South African mothers' perspective. African Sociological Review/Revue Africaine de Sociologie, 16(2), 119 - 138. [ Links ]

Newman, N., Levy, D. A., & Nielsen, R. K. (2015). Reuters Institute digital news report 2015: Tracking the future of news. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

Ngabaza, S., & Shefer, T. (2019). Sexuality education in South African schools: Deconstructing the dominant response to young people's sexualities in contemporary schooling contexts. Sex Education, 19(4), 422 - 435. [ Links ]

Philo, C. (2011). Foucault, sexuality and when not to listen to children. Children's Geographies, 9(2), 123 - 127. [ Links ]

Pound, P., Langford, R., & Campbell, R. (2016). What do young people think about their school-based sex and relationship education? A qualitative synthesis of young people's views and experiences. BMJ Open, 6, e011329. [ Links ]

Rammutla, K. (2019). 'Sex education must be stopped'. Daily Sun, August 19. https://www.dailysun.co.za/News/sex-education-must-be-stopped-20190818

Reygan, F. (2016). Making schools safer in South Africa: An antihomophobic bullying educational resource. Journal of LGBT Youth, 13(1/2), 173 - 191. [ Links ]

Rodny-Gumede, Y. (2012). Peace journalism and the usage of online sources. Communicare: Journal for Communication Sciences in Southern Africa, 31, 57 - 74. [ Links ]

Oeldorf-Hirsch, A., & Sundar, S. S. (2015). Posting, commenting, and tagging: Effects of sharing news stories on Facebook. Computers in Human Behavior, 44, 240 - 249. [ Links ]

Shefer, T., & Macleod, C. (2015). Life Orientation sexuality education in South Africa: Gendered norms, justice and transformation. Perspectives in Education, 33(2), 1 - 10. [ Links ]

Sokutu, B. (2019). The school of baby boomers. Citizen, October 23. https://reference-sabinet-co-za.uplib.idm.oclc.org/webx/access/samedia//2019/10/CITIZ20191023/CITIZ201910233_3.pdf

Statistics South Africa. (2018). Demographic Profile of Adolescents in South Africa. Statistics South Africa.

Sundaram, V., & Sauntson, H. (Eds.). (2016). Global perspectives and key debates in sex and relationships education: Addressing issues of gender, sexuality, plurality and power. Springer.

Swanepoel, E. (2020). New method, same curriculum: Taking a step back to reflect on 'doing' comprehensive sexuality education in the 21st century. [Review of the book Troubling the teaching and learning of gender and sexuality diversity in South African education, by D. A. Francis]. The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa, 16(1), 1 -2. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/td.v16i1.803 [ Links ]

Tajfel, H. E. (1978). Differentiation between social groups: Studies in the social psychology of intergroup relations. Academic Press.

Ubisi, L. (2020). Using governmentality and performativity theory to understand the role of social attitudes in young people with visual impairment access to sexual and reproductive health services. Gender & Behaviour, 18(2), 15399 - 15408. [ Links ]

UNESCO. (2018). International technical guidance on sexuality education: An evidence-informed approach. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/ITGSE_en.pdf

van Rooyen, K. (2015). Outrage over condoms for kids. The Herald, May 16. https://www.pressreader.com/south-africa/the-herald-south-africa/20150516/281775627736946

Villette, F. (2018). Sex education policy comment extended. Cape Times, June 28. https://www.pressreader.com/south-africa/cape-times/20180628/281676845648136

Walters, W., & Haahr, J. H. (2005). Governmentality and political studies. European Political Science, 4(3), 288 - 300. [ Links ]

Williams, M. (2019). Teachers unfit for sex ed. Citizen, May 15. https://www.pressreader.com/south-africa/the-citizen-gauteng/20190515/281809990346010

Wood, L. (2009). Teaching in the age of AIDS: Exploring the challenges facing Eastern Cape teachers. Journal of Education, 47, 127 - 150. [ Links ]

Received: 12 June 2020

Accepted: 10 August 2020

1 CSE refers to a long-term approach and investment in inculcating values, attitudes, and skills in relation to safe and healthy sexual practice, gender, power, sexuality construction, as well as consent and communication in relationships across the lifespan (UNESCO, 2018).