Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of Education (University of KwaZulu-Natal)

On-line version ISSN 2520-9868

Print version ISSN 0259-479X

Journal of Education n.79 Durban 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2520-9868/i79a07

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Career development of women principals in Lesotho: Influences, opportunities and challenges

Moikabi KomitiI; Pontso MoorosiII

IFaculty of Education, North-West University, Mafikeng, South Africa. berengmakuena@yahoo.com; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1402-2051

IIEducation Studies, University of Warwick, Coventry, United Kingdom. Department of Education, Leadership and Management, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa. p.c.moorosi@warwick.ac.uk; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4447-4684

ABSTRACT

In this paper, we present findings from a study that explored career development of women principals of high schools in Lesotho. The aim of the study was to understand how women principals construct career development experiences by looking specifically into how they choose careers in teaching, how these careers transition from teaching to principalship, and what career advancement opportunities exist in a particular context. Through a qualitative narrative inquiry, we conducted in-depth interviews with eight women principals on their personal and professional lives. The findings revealed that family played a significant role in influencing women's teaching career choices, while transitions from teaching to principalship were influenced by levels of readiness and desire to implement change and to improve student outcomes. Opportunities of career advancement included self-initiated study which improved qualifications, taking advantage of chances to perform leadership roles, as well as self-confidence and self-drive to actively seek promotion.

Keywords: women principals, career choices, career transitions, career opportunities, career development

Introduction

The under-representation of women in educational leadership has been a well-noted problem in many countries on the African continent (Chabaya, Rembe & Wadesango, 2009; Kitele, 2013; Moorosi, 2010; Uwamahoro, 2011) and the rest of the world (Coleman, 2001; Kaparou & Bush, 2007; Oplatka, 2004; Shakeshaft, 1987). Coleman (2001) noted that "women in educational management are a minority not only in the UK, but in countries with comparable levels of development and those that constitute the newly emerging economies" (p. 175). While studies of women in educational leadership and management have been carried out mostly in the west and in more developed countries focusing on white women's experiences (e.g., Coleman, 2001; Shakeshaft, 1987), the last two decades have seen some significant contributions from the developing world with specific focus on experiences of women principals who are not white and are from non-western contexts (Chan, Ngai, & Choi, 2016; Faulkner, 2015; Moorosi 2010; Sperandio & Kagoda, 2008). This research is, however, inadequate since it is still not clear which factors affect the advancement of women's career development in educational leadership in these contexts. This confirms the need for global research on the career development of female leaders as established by Oplatka (2004) and McLay (2008).

This study therefore set out to investigate and explore how women principals of high schools in Lesotho experienced career development which is, in this case, understood as a life-long process through which, following Super (1990), an individual develops a career identity starting from childhood. Here we explore influences on career choice, transitions, and opportunities of career development from teaching to principalship. Specifically, the study was guided by the following questions:

• What inspired female principals to choose a career in teaching?

• How do female teaching careers transition into principalships?

• What factors have promoted and/or hindered the career advancement of female principals?

Contextual background

While there is considerable research conducted on the African continent on women in educational leadership, not much is known about women in school leadership in Lesotho. What we do know is that in Lesotho, as in many other African societies, traditionally men have been the main providers of their families. Boys were socialised into this role very early in their lives and young men would leave school for work. As a result, while men were focused on work as the breadwinners for their families, women continued with their studies and, in gaining higher qualifications, were enabled to become established in formal employment (Matsie, 2009). This placed the country in a unique position in sub-Saharan Africa in making it the only country in this region in which women are more educated than men (Chwarae Teg Report, 2015; Mosetse, 2006). Ironically, under traditional law, Basotho women were legal minors whose rights of access to property and the courts could be effected only through their family male representatives (Matsie, 2009). More recently, however, Lesotho has become signatory to many international declarations in relation to gender equality and the protection of women's rights and has developed correspondingly appropriate legislation (Hausmann, Tyson, & Zahidi, 2012). Culturally, however, men are viewed as superior to women, so policies advocating for gender equality take a long time to come into effect (Chwarae Teg Report, 2015).

The absence of women in decision-making positions in educational institutions fails to reflect their educational advantage. The Chwarae Reg Report (2015) suggested that women in Lesotho may be literate but are not empowered to benefit from the policies and international ratifications to which Lesotho is signatory. The National University of Lesotho (NUL) and Lesotho College of Education (LCE), the two teacher training institutions in the country, have both experienced a high enrolment of female students in teacher education, resulting in an overwhelming 80 percent majority representation of women in teaching. The higher concentration of women is, however, in primary school teaching (78%) compared to an average of 54% in secondary schools (Kelleher, 2011). Women thus dominate the headship of primary schools but are less well represented in secondary schools and even less so in tertiary and university leadership. As Kelleher (2011) has made clear, this suggests that leadership is a gendered concept in Lesotho, with males often assumed to be the rightful leaders.

Given the high enrolment of female students in teacher training institutions, and the feminised status of teaching in Lesotho, one would expect there to be an equally high number of female teachers who have advanced to principalship positions in high schools. However, Posholi (2012) has shown the exact opposite to be true. Women are still under-represented in the positions of principalship of high schools in Lesotho, despite their training and achievements in education being so much greater in number and degree than men's and despite their dominance in the teaching profession overall. Significantly, and extending beyond the concern with gender parity, it is not known what factors contribute to and affect and/or shape the career development of the women who do make it to school principalship positions. Such knowledge would help advance women's career development and is, furthermore, vital for the development of programmes that would prepare them for principalship.

Women's career advancement

The literature suggests that women's advancement to senior positions in education is affected by various factors including culture, socio-political conditions, and gender regimes. One of these contributing ideologies is patriarchy, which informs the world's social structures and practices that give authority to men and legitimises the oppression of women in all sectors of society (Sultana, 2012). Patriarchy has thus been a stumbling block to women's freedom and success for hundreds of years and the subordination of women under patriarchy is deeply rooted in Basotho custom and law.

Gender stereotyping is another factor identified as affecting women's career progression. Linked to notions of patriarchy, the traditional view of women's roles as home-makers and child-bearers is of great disadvantage to women in gaining leadership positions; it frequently holds them back. Posholi's (2012) study on women in senior positions from different parastatals in Lesotho revealed that most participants intended to study further in order to improve their qualifications and take up senior positions. However, these aspirants were held back by being stereotyped as necessarily occupying caring and gentle roles that were not seen as befitting of leadership. Similarly, Chabaya et al (2009), asserted that the perception that looking after children and the home comes "natural[ly]" to women and "takes precedence over their career advancement" (p. 247), is a view driven primarily by conformity to social gendered norms and stereotypes.

The third factor is guilt, related to the duality of women's responsibilities between family and work. This leads to a potential role conflict since women are expected to be good home-makers yet are pressured to perform at high levels in their careers (Coleman, 2007; McLellan & Uys, 2009). Moorosi (2010) found that female principals in South Africa were under pressure to perform well in their careers while the pressure from the traditional expectation to be a good wife and mother militates relentlessly against them. While western women tend to delay their career progression while they raise a family (Coleman, 2007), a choice that tends to sabotage their progression into leadership that results in their always being behind their male counterparts, women from the developing world tend to balance these roles with the help of family and paid domestic help (McLellan & Uys, 2009; Moorosi, 2010).

Furthermore, where women appear to have overcome the adversities of structural oppression, they are often held back by organisational practices that do not support them in failing to provide opportunities for their career progression. These organisational barriers include lack of access to mentoring, networking, and training and development, as well as work cultures that are not supportive of women [and men] who have responsibilities related to caring for others (Moorosi, 2012; Spurk, Meinecke, Kauffeld, & Volmer, 2015). Other studies have shown that women have made progress where this organisational support is available (see Bosch, 2015; Moorosi, 2010) even though women may not benefit from same sex mentors (Moorosi, 2012; Spurk, et al, 2015). The opportunities given to women principals played a crucial part in their preparation for principalship and were used to their benefit to advance their careers.

Career development theory and gender

We found Super's (1990) career development theory with its emphasis on self-concept linked to leadership self-identity and gendered stereotypes appropriate and useful in explaining career choice and career development. According to Super (1990), career development is a life-long process through which people make vocational choices that express their self-concept. Self-concept in this sense means the extent to which people perceive themselves in relation to certain vocational choices and, in this case, how they perceive themselves in general. Super has suggested that self-concept changes over time and develops through different experiences that influence vocational maturity. He further posited that people implement and develop their self-concept during career development throughout which process they make vocational choices that enable them to express their self-concept. These choices may influence certain "image norms" (Giannantonio & Hurley-Hanson, 2006, p. 318) and beliefs about which occupations would be suitable given a particular self-concept.

Super (1990) identified five stages of career development (growth, exploration, establishment, maintenance, and decline) in which a person's career develops over a life span. In this framing, career development unfolds over time through a sequence of occupational positions and social roles that are assumed in a lifetime. This model acknowledges that career interests ought to be examined alongside other life interests and recognises that women's career patterns are different to men's because of the former's interest in family responsibilities. Although it has been criticised for its lack of sophistication and nuance on gender specific issues (Bimrose et al., 2014), it is regarded as one of the first career models to pay attention to women. We therefore found Super's conception of self-concept being used to view career development as a helpful organising framework in which to explain the lived experiences of female principals' career transitions and development over time.

According to Super (1990), the first stage is growth, during which a person develops self-concept, attitudes, and needs that relate to the general world of work. This is followed by exploration during which people explore possibilities through classes, work, and hobbies and also develop tentative choices and skills in order to become well developed. Establishment is the third stage, constituting the entry level for skills development and stabilisation through work experience. At this stage, teachers look to develop their skills so as to advance in their careers in preparation for maintenance, which is the fourth stage. This involves maintaining self-concept or self-belief in one's present job status. Finally, the decline stage means reduced output in preparation for retirement. Super acknowledged that these stages may or may not occur linearly nor necessarily correspond to chronological age because individuals go through the stages as they experience career transitions.

Methodology

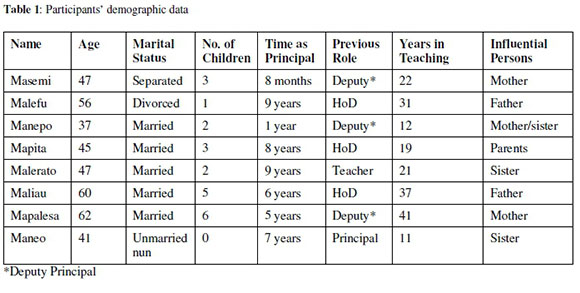

This study is positioned in the interpretive paradigm which, according to Nieuwenhuis, "serves as a lens through which reality is interpreted" (2007, p. 48). We used narrative inquiry within a qualitative approach to carry out in-depth semi-structured interviews with eight female principals of high schools. The narratives provided us with rich primary data on how each participant's career path had unfolded. According to Clandinin and Connelly (2000), a narrative inquiry focuses on participants' stories and the sequence of events that have affected their lives. Additionally, since, as mentioned above, career development is understood to be a life-long process, we chose an approach that could capture the lives of women in a holistic and culturally specific context as recommended by Goodson and Sikes (2001). Given that our focus was on female principals' experiences of career development, we made a purposive selection of women who were already in principalship of high schools, a context in which women are not well-represented. The eight participants were purposively selected from one town in Lesotho because of its large concentration of high schools. Details of high school principals were obtained from the district office and female principals were contacted by telephone. We conducted face-to-face in-depth interviews with those principals who were available and willing to be interviewed. Each interview took just over an hour.

To observe ethical protocol, participants signed informed consent forms with which they were provided, agreeing that they were voluntarily taking part in the study. As an outsider in the field of educational leadership practice, the first author as researcher had to be honest with the participants from the beginning about her own identity so that they could feel free to express themselves knowing to whom they were talking. This "self-disclosure" acted not only as a "gesture of reciprocity" (Zinn, 1979, p. 218) but helped to form good relationships and led to a high level of rapport between the researcher and the participants which is, as Oakley (1981) has pointed out, essential for effective [feminist] interviewing.

The participants' narratives were transcribed verbatim from the voice recordings of the interviews. Each recording was transcribed under the same set of questions so that the similarities and differences would be apparent. The research questions were used to organise the data into the themes that emerged from participants' narratives of their life stories. A coding system was used to organise raw data in order to make it more meaningful (see Glesne, 2011; Patton, 2002). We also used Renner and Taylor-Powell's (2003) five steps in the analysis of narratives in qualitative research data. These five steps involved reading the text thoroughly, identifying consistencies and differences in participants' responses, categorising information, identifying patterns and connections within and between categories, and developing an outline for the presentation of the results.

Findings

We present the findings on the career development of female principals based on the three themes 1) the influence on career choices, 2) career transitions, and 3) career advancement opportunities and challenges to women principals' career development. We have used pseudonyms to ensure confidentiality and the anonymity of our participants. The women were all Basotho born and bred in Lesotho and all had qualified teaching status. Other details of the participants are summarised in the table below.

The family as an influence on career choice

To begin with, we looked into early childhood influences on the career choices of female principals. The findings suggest that the teaching career choices of female principals were mostly influenced by family. For some female principals, it was easy to choose a career in teaching since the profession was well represented in their families.

For example, 'Manepo's mother and two sisters were teachers. She stated, "I was raised in the environment of teachers" and so it was natural for her to choose teaching.

Mapita mentioned that both her mother and father were teachers. She explained,

I grew up knowing only one profession which was teaching. My mother and father used to teach at the same school and I also went to school there even though they never taught me.

'Mapalesa's situation was slightly different in that her parents were not educated, yet she was encouraged by her mother to go to a teacher training college. She said,

My parents were farmers; they sold animals for my education and were living as low income earners. We are a family of six and I was the first girl in the community to go to the [teacher] training college because my parents wanted me to have a career and guided me towards becoming a teacher.

'Malerato and 'Maneo were both influenced by their older sisters to follow a career in teaching. 'Malerato admits that she did not want to be a teacher but, rather, an accountant. Yet her sister encouraged her to further her studies in education. She explained,

My sister told me that since I like accounting so much, I should do teaching and specialise with accounting so that I could teach it at high school and suddenly she was making sense to me and I accepted the advice with greater joy.

Although 'Maneo admired her sister who was a teacher and a nun, she did not want to follow the teaching profession herself but was somehow cajoled into it when she decided to become a nun. She stated that both her parents were not working, and at first she wanted to be a farmer like them. But the closest person with whom she grew up was her sister and she was a teacher. 'Maneo was the only participant who developed a passion and love for teaching at a very late stage in her life.

Transitioning from teacher to principal

Career transitions were marked by a move from teaching to principalship. These transitions were not linear since participants progressed via different routes even though they all started their careers as teachers. Responses showed that some decided to seek promotion actively from being teachers to being principals whereas others did not even think of the move until they were encouraged by other people or were nominated to the position of principalship. Moreover, some participants found themselves in principalship positions very early in their teaching career without preparation, while others felt prepared through following the promotion route.

Five participants did not actively pursue the principalship (unintentional journeys) while three of the participants purposefully sought principalship positions (intentional journeys).

Unintentional Journeys

The transition from teaching to principalship for women in this category was not planned. Opportunities for promotion presented themselves without much initiative on their part. 'Manepo studied for a Master's degree with the intention of moving to higher education teaching. However, while she waited for opportunities to teach at university she was asked to act as a principal when the current principal's contract expired. When asked at what stage she decided to become a principal, she said,

Never. I think it is a very stressful position, I never really wanted the position. I was hoping and planning to go to a higher institution when I came back from school [after doing Master's]. I did not want to come and work at the high school . . . because when you advance your degree you want to advance your career and I wanted to work at tertiary institutions, but it did not happen.

It is interesting to note that 'Manepo did not perceive moving to a leadership position in schools as an advancement in her career. As the youngest (37) of the participants, it can be deduced that she was exploring other options besides a career in school teaching.

'Maneo was the only participant who was in her second principalship at the time of the study. Her journey was rather different. She said,

I started working as a teacher . . . in [August] 2005 and . . . in 2006 January, the principal died and I was asked to act as a principal by the school board. I was scared and felt that I was not ready to take a huge step like that in my life. Remember I was just fresh from the university with little teaching experience and none on [an] administrative role. . . . I worked as a principal from 2006 to 2008 December. In 2009, I was given another job to take care of school finances until 2011. Later in 2011, management asked me if I could . . . be a principal [in another school] because the nun who was a principal was retiring from the position, but this time around I was a bit confident because of my previous principalship experience.

It is perhaps worth mentioning that, as a nun, 'Maneo did not have much control over her career moves since she could respond only to what she was being instructed to do by her superiors in the church.

'Maliau said she was comfortable being a teacher until she learned about a new school opening in her area. Although she had a great deal of experience, as a teacher and Head of Department, she had never really thought of becoming a principal, but was persuaded by the education officer's comment that it would "not be nice at her age" (in her 50s at that time) to be answering to someone else. Her husband also encouraged her to apply and convinced her that she had nothing to lose. She said,

To my surprise, I was short-listed, and I went for an interview and I got the job. I could not believe it at first; it took time to sink in. The school was established in 2010, so I have been the principal here since then.

'Mapita also did not intend to become a principal even though she was a Head of Department. She said that when the promotion happened it was a complete shock to her. She was nominated to act in the position when her principal left the school to further his studies.

Like four other participants, 'Mapalesa did not plan to become a principal, but was unexpectedly promoted into deputy principalship in 2004. She elucidated,

I did not know about this promotion. I did not know a lot of things at school. My main focus was my work. I was a marker and I was out marking, then I was called by the school board and I had no idea why they wanted to see me. They asked me if I could be a deputy principal [of the school] and I accepted [and] that is how the promotion came along. I did not apply for it.

We noted that at age 62, 'Mapalesa had 41 years of teaching experience in total, which included only 6 years as a principal. Although the women in this category did not plan their careers, it is possible that they harboured latent ambitions so none of them objected to the promotion.

Intentionally sought promotions

Three participants had intentionally sought promotion in order to become principals. These go-getters-'Masemi, 'Malefu and 'Malerato-actively applied for promotion and did not give up when it did not happen the first time around.

'Masemi had a passion for the position of principalship and said she knew that she was destined for bigger things and therefore worked hard to achieve her goals. She declared,

I developed [a] passion for principalship when I was studying part-time while I was also teaching. So, the new knowledge I acquired made me feel that I was ready and full of ideas for [a] principalship position. My honours and postgraduate diploma helped me to see and understand that things should not be running like that and that there was a need for change in that school.

Her teaching career started in 1994 and she had 18 years of teaching experience when she finally decided to apply for promotion. Her first application in her own school was not successful since she was rejected because she was a woman. She said,

I was told that I was good, but the school board was looking for a male principal.

This overt discrimination did not put her off completely, although she later applied for a deputy principal position in another school. However, it turned out that the principal of the school was on suspension and, to her surprise, she was asked to act as the principal until she was offered the job permanently.

'Malefu told us why she sought the principalship position when she explained,

I decided to become a principal when I was still at a private school because once I was from the university, I could not see anything standing in my way of becoming a principal, with my degree. I really looked around and wanted to do something different, so immediately after my graduation, I felt that I no longer belonged to the classroom.

There is something significant about what triggered the need for change in both 'Masemi and 'Malefu; it was the education they received while upgrading their qualifications that made them dream of doing bigger things as well as boosting their confidence to apply for the principalship. And this is different from 'Malerato's case in that she just took a leap of faith in actively seeking promotions. She recounted,

When I was still teaching at the previous high school between 2004 and 2005, I felt that I was ready to become a principal. I started looking for the vacancies for the position, then in 2006, I heard that this school was being upgraded from primary to high school, so I took a chance and applied. Fortunately, I got the job.

'Malerato became a principal in her late 30s, becoming the only principal in our study who transitioned into principalship straight from the classroom. For women like her, it is the self-drive and personal agency that seems to have made a difference regarding whether to actively pursue the principalship.

The women participants' reasons for transitioning to principalship can be summarised thus:

1. They felt that they were ready for the position after they had improved their studies.

2. They wanted to see their ideas being implemented.

3. They had enough experience with in the classroom.

4. They wanted to see change.

Informal mentoring and networking

In addition to factors that facilitated the transition into principalship presented above, two organisational factors (informal mentoring and networking) emerged as significant factors in the women principals' career advancement. Informal mentoring occurred mostly through women being encouraged to apply for promotion as explained above. In addition to that, 'Masemi mentioned that she was supported by her previous principal who "valued my input and ideas so much and I was motivated to always do my best and more."

'Manepo was grateful for the networking opportunities that were made available for principals. She observed, "I think one of the things that is good about being a principal is that one gets to know a lot of important people; networking is very important in this job."

'Malefu explained how she had an opportunity to develop herself and her teachers when she said,

[You get] the opportunity to develop [your] teachers as much as you develop yourself. Sometimes we go to African conferences and international conference in Australia to network because it is important to network in this kind of work so as to find out how best can you deal with situations in the position that you are in, so our Principals Association and Ministry of Education take care of all that.

'Mapita also had an opportunity to travel overseas through the Principals' Association network. 'Maneo described activities that were involved in meetings and workshops when she explained,

We are divided into sections and this . . . has made me grow or develop because they used to hold workshops a lot. Other principals used to share their experiences with us new principals back then. They even gave me materials about leadership skills, how to keep records . . .

Both 'Mapalesa and 'Malerato knew about the great work that was done by the Principals' Association but had never made use of it, thus suggesting the need for personal initiative as well. Opportunities for career development also gave participants a chance not only to develop themselves, but to develop their teachers as well. This shows the significance of mentoring and networking and their possible benefits for the wider organisation.

Family as a source of support

Beyond influencing career choice, family also emerged as a strong source of psychosocial support for women's career development. This was through moral support and help with childcare. 'Maliau, 'Maneo, 'Manepo, 'Malefu, and 'Masemi all expressed their gratitude for the support they had received from their families throughout their career journey. They said that they have always had support from their parents and siblings who were there to listen whenever they faced challenges and that they provided advice and a shoulder to cry on. 'Malefu said that she has always had support from her mother and brother and she even dedicated her achievements to them when she said,

My mother was my everything. When I went up and down learning and working she used to stay with my son and it became a challenge when she died because I had to pick him up and we were even strangers because he could relate [more] easily to my mother than [to] me.

All was not lost, though, since she was left with her brother who would remind her constantly that her mother wanted her to be a principal.

For 'Manepo, her mother and father were always there to comfort her and give her advice whenever she needed it. She said,

When I was already a deputy principal, my father . . . always talked to me about what I should do, how to deal with people with different characters, especially people who seem to be very troublesome, how to approach people, what is the best way to deal with people. . . [He used to say] 'Always do what is right, do not do your work to satisfy other people but always do what is right for the school.'

'Maneo and 'Masemi also drew their strength from their respective mothers. In contrast, 'Maliau mentioned that she got support from her husband. She explained,

My husband is also a teacher, so he knows and understands when I am under pressure at work and have to bring work home and not be able to cook supper sometimes and he does it. He also has been very supportive throughout the whole journey because he understands the field very well and that one needs to seek opportunities and grow or develop.

Challenges to women's career advancement

Challenges to female principals' career advancement are summarised in the two themes of gender discrimination at the work place and family responsibilities.

Gender discrimination

Participants talked about their capabilities and intelligence being undermined simply because they were women. 'Masemi faced this challenge in the selection process when she applied for a principalship and was directly discriminated against. She exclaimed,

I did not get the position because the school board at the time had [an] old mindset that the position was suitable for a strong man not a woman. I think that school has had one female principal so far since it has been established, so the school board looked at me, my stature, my age. And I felt so hurt because I really worked hard and long in that school and even school board members knew that I was capable of doing the principal's job efficiently and effectively but I was told that I was good but the school board was looking for a male principal!

'Malerato expressed how she felt the sexist undertones, which meant that she could not be trusted with certain roles because of her gender when she declared,

When you are a woman, people do not think you can do it because you are a female principal and there are males under you and those males undermine you thinking that you lack managerial skills just because you are a woman.

Female principals face gender discrimination not only from the school board members and teachers but from parents as well, as 'Maliau experienced. She said,

I really work well with my staff so the only problem is that of parents when they do not want to pay school fees. They think because I am a woman they can walk all over me. They like passing remarks like, 'If only this school was led by a man things would be great" and I just ignore them.

'Mapita also had the same problem of being undermined by men just because she is a female principal. She revealed,

I have dismissed seven men from this school since I became a principal, including a Pastor. They did not appreciate being led by a woman, so they did not hide their feelings and thoughts in the meetings, and they tortured me just for being a female principal. I used to lock myself in my office and cry until I told myself that enough was enough.

Family responsibilities

Female principals mentioned that family responsibility was one of the problems that inhibited their career advancement. 'Malerato had this to say,

I felt that I was ready to become a principal long before I could actually take a step to apply for it. I used to be worried because I always heard of vacancies in high schools which were far from my home place where I stayed with my family and I did not see how I could stay away from my family until my husband convinced me to apply and try it for some time and see how it goes.

While Malerato's husband played a supportive role, 'Malefu went through a different experience in that she found it impossible to leave her husband after getting married, thus delaying her career advancement. She explained,

I got married in 1981, which means for . . . ten years I had nothing to do with education because I [only] went back to school to train for teaching in 1991. . . I did not want to think about anything which would take me away from my husband for a long time like going to school because we [had] just got married so with the jobs I did it was better because I came back to him every day after work. If I went back to school earlier, my career could have advanced quicker than it did. But I have learned my lesson the hard way because that person I stopped my dreams for is now divorcing me. I guess it is life's lessons (laughs).

Most of the participants viewed it as a weakness that women tend to put family ahead of career. They believe having a family should not distract them from reaching their goals because their professional success is their family's success.

Discussion

Influences

Findings reveal that family was instrumental in influencing the women principals' career choices in teaching. Participants were mostly exposed to teaching, which is a typically feminine career choice at both primary and secondary levels (Kelleher, 2011). Even someone who aspired to become an accountant is somehow cajoled into a softer version of a career in commercial subjects. A couple of issues are at play here: the strong influence of family that leads women into conforming to social norms (see Chabaya et al., 2009; Mutekwe & Modiba, 2012) and limited autonomy in career choices for women in Lesotho. The influence of family in this study is unsurprising, since, as Taylor, Harris and Taylor (2004) have maintained, without parental approval, children are often reluctant to pursue, or even explore certain careers. The findings are also partly consistent with those of Inman (2011) and McKillop and Moorosi (2017) who established that at the formation stage most participants' career choices were influenced by parents, extended family, and teachers. We found it surprising that schooling and teachers were not mentioned as key influencing agents at the growth stage, contrary to existing literature (e.g. McKillop & Moorosi, 2017; Ribbins, 2008). Most of these women were in their 40s and above at the time of the study and were of a generation that grew up when teaching and nursing were the main careers available to women in Lesotho. Additionally, although as professionals the participants lived and worked in the town, they were brought up in rural villages where opportunities for career guidance were less available and where subsistence agriculture and livestock farming were the main occupations for women while men worked in the South African mines. Career choice was, in this sense, also shaped by socio-economic conditions given which, financial security is important. Super (1990) referred to situational determinants as factors involving individuals' socio-economic conditions that may affect career choice. Since women could not work in the mines in neighbouring South Africa, getting an education and a career were ways of ensuring a better socio-economic status. Also, Giannantonio and Hurley-Hanson (2006) have posited that normative images of a career formed in the growth stage that arise as a result of family influence may have subtle but long-lasting effects on an individual's career choices. Mutekwe and Modiba (2012) have linked the effect of family influence to gendered social norms of socialisation. This means, then, that the visibility of a teaching career arguably makes teaching an obvious choice for most women of the participants' generation, given that these images were powerful since they were the only images of a visible career choice for women during their childhood and youth.

Transitions and opportunities for women's career development

The second theme refers to opportunities for career development, which can be summarised as the organisational factors of the promotion route, informal mentoring, and networking. Career transition from teaching to principalship occurred at different stages of the career development of the women principals in our study. Findings suggest that women transitioned intentionally (by design) and accidentally (by default). Participants who intentionally sought the principalship all went through the promotion route or had pursued further study which strengthened their self-concept (see Super, 1990), preparing them for the principalship. Self-initiated career advancement opportunities in the form of further studying gave women the confidence to actively seek promotion from the classroom. This is similar to Faulkner's (2015) finding that participants felt confident that nothing could stop them from becoming principals after they had had the experience and acquired the necessary qualifications despite the latter not being a requirement. What is also discernible here is the high value placed on the education and higher qualifications that were believed to have facilitated their transition into principalship. These findings concur with those of Moorosi (2010) and Chan et al. (2016) that women studied continually so that they could get promoted to a principalship. Besides their acquiring higher qualifications, there is evidence of high levels of self-drive and personal agency among women who actively sought promotion.

In contrast, women who transitioned by default were more reactive to opportunities when they presented themselves. These women were spurred on by encouragement from some trusted people who acted as informal mentors. No further involvement of these informal mentors was observed beyond this transitioning stage, but there is a strong evidence of networking during the principalship tenure. Kruse and Krumm (2016), Bosch (2015), and Eckman (2004) found that women who were not overtly ambitious were likely to apply for the principalship when they were encouraged by other people to step out of the classroom and seek such promotion. While this can be seen as a result of lack of confidence and/or lack of career planning (see Coleman, 2007), this has been explained by others (Faulkner, 2015; Moorosi, 2010; Sanchez & Thornton, 2010) as the lack of exposure to leadership roles and the association of leadership with masculinity, which makes women appear hesitant to apply for principalship positions even when they qualify for them. Presenting high school leadership as a male's territory is a direct result of the patriarchal tendency that assumes that authority and power emanate from masculinity in comparison with women's femininity and submissiveness (Sultana, 2012). Principalship was not a visible career move for these women since they all replaced male principals (see Chan et al., 2016). Considering some of the gendered discrimination experienced by some of the participants, and the reasons given for not transitioning earlier, it is possible that women did not perceive themselves as future principals because of their gender; principalship was not part of their self-concept (Super, 1990), arguably because of cultural and structural impediments that disadvantage women despite Lesotho's reported advancement in female education and progress on gender equality policies.

However, the women in this study do benefit from informal mentoring from their former principals, colleagues, and spouses who happen to be men. Spurk et al., (2015) and Moorosi (2012) have used similarity attraction theory to show women benefiting from men as sources of mentoring support. Spurk et al., (2015) argue that women and men tend to have access to the same organisational factors which include mentoring and networking, yet these have varying effects, arguably because women's career advancement "values are aligned with their wish to fulfil family responsibilities" (p. 115). McKillop and Moorosi (2017) conclude that encouraging women teachers to apply for promotion is something that needs to be institutionalised within organisations. Encouraging women into leadership positions boosts their confidence in their ability to lead, as Young and McLeod (2001) observed. Women who receive professional endorsement are more likely to mentor and support others.

Challenges to women's career advancement

Challenges to the career advancement of women principals included gendered discrimination at the work place and family responsibilities. These findings concur largely with those in the existing literature (see Chabaya et al., 2009; Chan et al., 2016). Some of the participants considered principalship only after teaching for more than twenty years and after being held back by family considerations. We believe that the slow career progression of women in this regard in Lesotho is shaped by patriarchal tendencies since the subordination of women is deeply rooted in the Basotho culture. Women here take longer to develop a leadership self-concept and identity, and, while previous literature links this to self-esteem and/or self-efficacy (Betz, 1994), we see an interplay with culture and gender norms as well. Chan et al., (2006) have argued that

when gender norms in society prescribe different, and often inferior, roles to women, these shape not only their career orientations but also the way schools are organised and the social perception of leadership. (p. 195)

The gendered nature of structural impediments can also be discerned here; women face gendered prejudice in organisations that affects their career development. Contrary to Super's (1990) theory that suggests that all individuals have the agency to shape their vocational development, these prejudicial experiences point to women's limited autonomy in patriarchal societies. It is possible that Super's career maturity, which implies women's readiness to cope with gendered challenges to career development, improves women's resilience against discrimination. This would account for their ability to blossom in the later stages of career development when they are approaching the decline stage. Engaging further with this notion is beyond the scope of this article but we suggest that it warrants further exploration in future studies of women's career development in school leadership.

Conclusion

In analysing the career development stories of eight female principals in a context where very little is known about women in school leadership, our contribution is contextual and geographical. Our explanation of why women in Lesotho are still not able to transform the educational leadership landscape, despite their educational advantage over men in higher levels of literacy, higher qualifications, and the feminised teaching profession, we blame the patriarchal ideology that views men as the official holders of authority. Despite the advantages listed above, women are not empowered to dismantle the patriarchy and begin to change the landscape of educational leadership. This problem cannot be solved by women alone so we call on men to help improve women's career development in school leadership. Patriarchal thinking that values masculine superiority constrains women's career advancement despite the presence of policies on gender equality and the agency of individual women. In a significant theoretical contribution we note a strong interplay of personal agency, culture, and economic conditions that shape career choices, career transitions, and overall experiences in the career development of women principals. However, we note that ours was a small sample of eight women, but we suggest that this opens what should be an ongoing dialogue on women's career development in school leadership.

References

Betz, N. E. (1994). Self-concept theory in career development and counseling. The Career Development Quarterly, 43, 32-42. [ Links ]

Bimrose, J., Watson, M., McMahon, M., Haasler, S., Tomassini, M., & Suzanne, P. A. (2014). The problem with women? Challenges posed by gender for career guidance practice. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 14(1), 7788. [ Links ]

Bosch, M. (2015). Investigating the experiences of women principals in high schools in the Western Cape (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Stellenbosch University, RSA. [ Links ]

Chabaya, O., Rembe, S., & Wadesango, N. (2009). The persistence of gender inequality in Zimbabwe: Factors that impede the advancement of women into leadership positions in primary schools. South African Journal of Education, 29(2), 235-251. [ Links ]

Chan, A. K. W., Ngai, G. S. K. & Choi, P. K., (2016). Contextualising the career pathways of women principals in Hong Kong: A critical examination. Compare, 46(2), 194-213. [ Links ]

Chan, A. K., Ngai, G. S., & Choi, P. (2016). Contextualising the career pathways of women principals in Hong Kong: A critical examination. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 46(2), 194-213. [ Links ]

Chwarae Teg Report. (2015). A woman's place in Lesotho: Tackling the barriers to gender equality. Retrieved from https://www.cteg.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/chwarae-teg-report-a-womans-place-in-lesotho-DT-en.pdf

Clandinin, D., & Connelly, F. (2000). Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Coleman, M. (2001). Achievement against the odds: The female secondary headteachers in England and Wales. School Leadership & Management, 21(1), 75-100. [ Links ]

Coleman, M. (2007). Gender and educational leadership in England: A comparison of secondary head teachers' views over time. School Leadership and Management, 27(4), 383-399. [ Links ]

Eckman, W. E. (2004). Similarities and differences in role conflict, role commitment and job satisfaction for female and male high school principals. Educational Administration Quarterly, 40(3), 366-387. [ Links ]

Faulkner, C. J. (2015). Pathways to principalship: Women leaders of co-educational high schools in South Africa: A life history study (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, RSA. [ Links ]

Giannantonio, C. M. & Hurley-Hanson, A. E (2006) Applying image norms across Super's career development stages. The Career Development Quarterly, 54(4), 318-330. [ Links ]

Glesne, C. (2011). Becoming qualitative researchers: An introduction (3rd ed.). Boston. MA: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Goodson, I., & Sikes, P. (2001). Life history research in educational settings: Learning from lives. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Hausmann, R., Tyson, L. D., & Zahidi, S. (2012). The global gender gap report. Retrieved from https://c2you.eu/data/GenderGapReport2012.pdf

Inman, M. (2011). The journey to leadership for academics in higher education. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 39(2), 228-241. [ Links ]

Kaparou, M., & Bush, T. (2007). Invisible barriers: The career progress of women secondary school principals in Greece. Compare, 37(2): 221-237. [ Links ]

Kelleher, F. (2011). Women and the teaching profession: Exploring the feminisation debate. London, UK: Commonwealth Secretariat. [ Links ]

Kitele, A. N. (2013). Challenges faced by female headteachers in the management of secondary schools: A case of Kangundo District in Machakos County, Kenya (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Kenyatta University, Nairobi, KE. [ Links ]

Kruse, R. A., & Krumm, B. L. (2016). Becoming a principal: Access factors for females. The Rural Educator, 37(2), 28-38. [ Links ]

Litmanovitz, M. (2010). Beyond the classroom: Women in education leadership. Kennedy School Review, 11, 25-28. [ Links ]

Matsie, R. (2009). Gender relations and women's livelihoods in the post-mine retrenchment era: A case study in Mafeteng, Lesotho (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Pretoria, RSA. [ Links ]

McKillop, E., & Moorosi, P. (2017). Career development of English female head-teachers: Influences, decisions and perceptions. School Leadership & Management, 37(4), 334353. [ Links ]

McLay, M. (2008). Headteacher career paths in UK independent secondary coeducational schools: Gender issues. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 36(3), 353-372. [ Links ]

McLellan, K., & Uys, K. (2009). Balancing dual roles in self-employed women: An exploratory study. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 35(1), 21-31. [ Links ]

Moorosi, P. (2010). South African female principals' career paths: Understanding the gender gap in secondary school management. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 38(5), 547-562. [ Links ]

Moorosi, P. (2012). Mentoring for school leadership in South Africa: Diversity, dissimilarity and disadvantage. Professional Development in Education, 38(3), 487-503. [ Links ]

Mosetse, P. (2006). Gender stereotypes and education in Lesotho (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, RSA. [ Links ]

Mutekwe, E., & Modiba, M. (2012). Girls' career choices as a product of a gendered school curriculum: the Zimbabwean example. South African Journal of Education, 32, 279292. [ Links ]

Nieuwenhuis, F. J. (2007). Introducing qualitative research. In J. L. Maree, (Ed.), First steps in research (pp. 98-122). Pretoria, RSA: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Oakley, A. (1981). Interviewing women: A contradiction in terms. In H. Roberts (Ed.), Doing feminist research. London, UK: Routledge & Kegan Paul. [ Links ]

Oplatka, I. (2004). The principal's career stage: An absent element in leadership perspectives. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 7(1), 43-55. [ Links ]

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research & evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks. CA: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Posholi, M. R. (2012). An examination of factors affecting career advancement of women into senior positions in selected parastatals in Lesotho (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Cape Peninsula University of Technology, Cape Town, RSA. [ Links ]

Renner, M., & Taylor-Powell, E. (2003). Analyzing qualitative data. Retrieved from: https://cdn.shopify.com/s/files/1/0145/8808/4272/files/G3658-12.pdf

Ribbins, P. (2008). A life and career-based framework for the study of leaders in education: Problems, possibilities and prescriptions. In J. Lumby, G. M. Crow & P. Pashiardis (Eds.), International handbook on the preparation and development of school leaders (pp. 61-80). New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Sanchez, J. E., & Thornton, B. (2010). Gender issues in K-12 educational leadership. Advancing Women in Leadership Journal, 30(13), 2-15. [ Links ]

Shakeshaft, C. (1987). Women in educational administration. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Sperandio, J., & Kagoda, A. M. (2008). Advancing women into educational leadership in developing countries: The case of Uganda. Advancing Women in Leadership Journal, 27, 1-14. [ Links ]

Spurk, D., Meinecke, A. L., Kauffeld, S., & Volmer, J. (2015). Gender, professional networks, and subjective career success within early academic science careers: The role of gender composition inside and outside departmental support networks. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 14, 121-130. [ Links ]

Sultana, A. (2012). Patriarchy and women's subordination: A theoretical analysis. Arts Faculty Journal, 4, 1-18. [ Links ]

Super, D. E. (1990). A life-span, life-space approach to career development. In D. Brown, L. Brooks, & Associates (Eds.), Career choice development (2nd ed.) (pp. 197-261). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Taylor, J., Harris, M. B., & Taylor, S. (2004). Parents have their say... About their college-age children's career decisions. Nace Journal, 64(2), 15-21. [ Links ]

Uwamahoro, J. (2011). Barriers to women in accessing principalship in secondary schools in Rwanda: A case study of two secondary schools in the Gicumbi District (Unpublished Masters thesis). University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, RSA. [ Links ]

Young, M. D., & McLeod, S. (2001). Flukes, opportunities, and planned interventions: Factors affecting women's decisions to become school administrators. Educational Administration Quarterly, 37(4): 462-502. [ Links ]

Zinn, M. B. (1979). Field research in minority communities: Ethical, methodological and political observations by an insider. Social Problems, 27(2), 209-219. [ Links ]

Received: 21 January 2019

Accepted: 2 January 2020