Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of Education (University of KwaZulu-Natal)

On-line version ISSN 2520-9868

Print version ISSN 0259-479X

Journal of Education n.75 Durban 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2520-9868/i75a06

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Compliance with legislative framework in implementing recognition of prior learning (RPL) by South African library and information science (LIS) schools

Ike Hlongwane

Department of Information science, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa http://orcid.org/00000003-2224-1238

ABSTRACT

RPL is defined broadly as the principles and processes through which prior experiences, knowledge, skills, and attitudes acquired outside the formal learning programme are recognised and assessed for purposes of certification, alternative access and admission, and further learning and development (South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA) 2013). In this paper, I highlight the importance of an enabling environment in the development and implementation of RPL in library and information science (LIS) in South Africa. The SAQA RPL policy (2002) makes it explicit that "an enabling environment" (p. 18) demonstrating commitment to RPL is essential. It is evident from the document that unless proper policies, structures, and resources are allocated to a credible assessment process, it can easily become an area of contestation and conflict. In my study, I adopted a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods which involved the use of questionnaires and document analysis to collect data. I found that there are islands of good practice in terms of compliance with the legislative framework in implementing RPL in South African LIS schools. I recommend, among other things, that the Department of Higher Education (DHE) together with the Council on Higher Education (CHE) and SAQA conduct regular monitoring and evaluation processes of RPL implementation in LIS schools to encourage compliance with prevailing legislative frameworks. Further, periodic RPL accreditation processes could also be used to great effect to ensure that LIS schools comply, failing which, their accreditation to offer RPL services could be reviewed. This will help create an enabling environment, which is a prerequisite for an effective and credible recognition of the RPL process.

Keywords: Recognition of prior learning (RPL), legislative framework for RPL, library and information science (LIS) schools, South Africa, South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA) RPL policy.

Introduction

RPL is defined broadly as the principles and processes through which prior experiences, knowledge, skills, and attitudes acquired outside the formal learning programme are recognised and assessed for purposes of certification, alternative access and admission, and further learning and development (SAQA, 2002, 2013). RPL is a globally lauded phenomenon that provides access to learning programmes in the Higher Education and Training sector on a continuum that quantifies informal education by apportioning credit value as applicable in the academic or formal education realm. In South Africa, SAQA's RPL policy (2013) advocates commitment to the principles of equity and redress and it identifies two RPL target groups.

The first one is the access group that is made up of

• under-qualified adult learners wanting to up-skill and improve their qualifications; and

• candidates lacking minimum requirements for entry into a formal learning programme.

The second one is the redress group that is made up of

• workers on the shop floor or in the workplace who may be semi-skilled and even unemployed and who may have worked for many years but were prevented from developing because of restrictive past policies; and

• candidates who exit formal education prematurely and who have, over a number of years, built up learning through short learning programmes.

The significance of RPL as a catalyst for career and professional development is underscored in the literature. For instance, it has emerged that RPL can be used as a mechanism to offer non-traditional learners such as workers, adult learners, and community workers access to learning opportunities (Bowman et al., 2003; Wheelahan et al., 2003). In the LIS sector in South Africa, RPL can be used for up-skilling. The benefit of this is that it promotes professional development but at the same time enhances promotional opportunities for LIS staff by enabling them to migrate from paraprofessional to professional roles. Owing to past injustices, the South African Higher Education and Training sector is characterised by inequalities of resource allocation and of learning opportunities. Recognition of RPL was established through the National Qualification Framework (NQF), to address the previous inequalities in this sector. LIS schools could use this approach to offer experienced but unqualified library workers opportunities for progressive professional development and career growth.

South Africa is recuperating from the disparities of apartheid and RPL is one of the tools that can be used to address past inequalities. However, although the intention behind RPL is good, there is evidence that its success can be compromised if it is not properly implemented (SAQA, 2013). This is why I support the thesis that the implementation of RPL has to be preceded by, or juxtaposed with, the establishment of an enabling environment characterised by context specific RPL provision that takes into account policies, structures, and available resources to ensure successful implementation. Based on SAQA's Criteria and Guidelines for Assessment of NQF registered Unit standards and Qualifications (2001), several questions must be answered in order to determine the extent to which LIS in South Africa complies with legislative and regulatory frameworks relating to RPL that will ensure successful implementation. These include whether

• institutional RPL policies are based on the SAQA policy (2013);

• there is an institutional will to open up access to diverse learners;

• LIS schools are committed to NQF principles of equity/redress and inclusion;

• information about RPL services is widely available to potential candidates;

• admission procedures in LIS schools are inclusive of non-matriculated learners; and

• there are formal articulation agreements within the broader LIS sector.

Post-1994, the LIS profession has been dramatically affected by the restructuring of the South African Higher Education and Training sector because of changes to national policy regarding primary, secondary, and higher education (Ocholla & Bothma, 2007; DAC, 2010). In particular, the drop in student numbers resulted in a reduction in the number of institutions offering programmes in LIS from 18 schools in 2000 to the current 10 (Ocholla & Bothma, 2007; Department of Arts and Culture (DAC), 2010). The University of Johannesburg (UJ) and Stellenbosch University (SU) refocused and rationalised their qualifications by moving away from traditional library-oriented education into information technology (IT) and information and knowledge management fields (DAC, 2010). There are currently 10 LIS schools in South Africa.

• Durban University of Technology (DUT),Department of Information and Corporate Management (Library and Information Studies & Office Management and Technology)

• University of Cape Town (UCT), Library and Information Studies Centre (LISC)

• University of Fort Hare (UFH), Department of Library and Information Science

• University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN), Department of Information Studies

• University of Limpopo (UL), Department of Information Studies

• University of Pretoria (UP), Department of Library and Information Science

•University of South Africa (UNISA), Department of Information Science

• University of Zululand (UZ), Department of Information Studies

• Walter Sisulu University (WSU), Department of Library and Information Science

• University of Western Cape (UWC), Department of Library and Information Science.

Different institutions offer different entry routes to the LIS profession (Ocholla & Bothma, 2007; Nassimbeni & Underwood, 2007). Institutions such as UNISA, UFH, UP, UWC, and UZ offer an undergraduate qualification at entry level. Other institutions such as UCT and UKZN offer a postgraduate diploma towards a professional career in the LIS sector. UZ, UL, UNISA, UWC, and WSU also offer both an undergraduate degree and a postgraduate diploma.

LIS schools in South Africa are struggling to survive as a result of declining numbers in student enrolment because of less interest in librarianship as a career and the impending retirement of incumbent scholars (Ocholla & Bothma, 2007; Stilwell, 2009; DAC, 2010). In their struggle for survival, South African LIS schools are making changes to their courses and positioning themselves in various schools, departments, and faculties (Ocholla & Bothma 2007).

Using RPL, LIS schools can tap into a large pool of many library practitioners who are either unqualified or under-qualified (Davids, 2006, cited in Hlongwane, 2014, p. 2). When these people achieve recognised status "at a level of assistant, paraprofessional or professional" (Underwood, 2003, p. 53), the shortage of qualified staff in the LIS sector, as noted by Stilwell (2009), can be alleviated and this will also increase, in part, opportunities for the survival and viability of LIS schools in the South African Higher Education and Training sector.

Problem and purpose of the study

One of the key drivers for RPL is its capacity to act as a mechanism for social inclusion by improving opportunities for people to use their informal learning to gain recognised qualifications (Young, 2001). To effectively implement the RPL mechanism in higher education and training, an enabling environment demonstrating commitment to relevant legislative and regulatory frameworks with regard to admission policies, structures and resources including willingness to open up access, commitment to NQF principles of equity/redress and inclusion, availability of RPL services and formal articulation agreements within the broader LIS sector, needs to be created (SAQA, 2002; 2013). Several studies have been conducted on RPL in the LIS field in South Africa. However, no study appears to have been conducted to determine compliance with the legislative framework in implementing RPL in the LIS sector. This is, therefore, what I sought to determine in this study.

The main objectives of the study were

• to examine the use of SAQA policy (2013) in the development of institutional RPL policies;

• to find out whether there was an institutional will to open up access to diverse learners;

• to establish the commitment of LIS schools to NQF principles of equity/redress and inclusion;

• to determine the availability of information of RPL services to prospective candidates;

• to examine admission procedures in LIS schools; and

• to determine the existence of formal articulation agreements in the broader LIS sector.

Literature review

The fundamental prerequisite for an effective and credible implementation of an RPL programme is the establishment of an enabling environment (SAQA policies, 2013). As in other countries such as Australia and New Zealand, the development of a national qualifications systems has been a driver of RPL (Australian qualifications framework, AQF, Advisory Board, 2002; New Zealand Qualification Authority, NZQA, 2003). However, despite widespread interest and activity in RPL in higher and further education sectors in the US, there is no national RPL policy in their national education system or framework (International Labour Organisation, ILO, 2005). In addition, in the UK, there is no national RPL policy as such but the Quality Code (Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education, QAA, 2013) covers the assessment of RPL. Furthermore, the implementation of RPL or Prior Learning Assessment and Recognition (PLAR), as it is known in Canada, is within existing educational, professional, and employment systems (Van Kleef, 2011).

In South Africa, and, as mentioned earlier, in Australia and New Zealand, various laws and regulations have been promulgated in order to support the establishment of an enabling environment for the development of a comprehensive RPL policy.

The South African Qualifications Authority Act 58 of 1995 was the key driver in assisting individuals who were previously denied access to higher education and training because of the apartheid system. In the main, this Act was established with a view to develop and implement the NQF, which inherently includes RPL. The RPL principle is fundamental to the development of new education and training systems based on the NQF (SAQA, 2002) so that, following Harris (1997), national qualifications and outcome-based unit standards can be registered. Through RPL, the NQF is intended to give previously disadvantaged individuals much needed opportunities for lifelong learning. According to Du Pré (2004), these individuals are increasingly gaining access to higher education and training through this RPL mechanism.

The Skills Development Act of 1998 was intended to provide an "institutional framework to develop and improve the skills of the South African workforce" (Department of Labour, 1998b, p. 2). The importance of improving the employment prospects of people who were previously disadvantaged by unfair discrimination and to redress those disadvantages through training and education is explicitly stated in this act. This Act also formed the foundation for the establishment of Sector Education and Training Authorities (SETAs). Among their other functions, the SETAs facilitate the development and implementation of RPL policies in all economic sectors. As Education, Training and Quality Assurance (ETQA) mechanisms, the SETAs are also responsible for ensuring quality RPL outcomes in these sectors.

The Employment Equity (EE) Act 55 of 1998 (Department of Labour, 1998a) stated that employers have a duty to eliminate unfair discrimination. The Act also provides a framework through which the employer can attract, develop, advance, and retain his or her human resource talent. This Act recognises that

• as a result of apartheid and other discriminatory laws and practices, there are disparities in employment, occupation, and income within the national labour market; and

• these disparities create pronounced disadvantages for certain categories of people and these disadvantages cannot be redressed simply by repeating discriminatory laws.

The purpose of the EE Act (1998) is to achieve equity in the workplace by

• promoting the constitutional right of equality, and the exercise of true democracy;

• eliminating unfair discrimination in employment;

• ensuring that employment equity is implemented to redress the effects of discrimination;

• achieving a diverse workforce that is broadly representative of the South African population;

• promoting economic development and efficiency in the workforce; and

• meeting the Republic of South Africa's obligations as a member of the International Labour Organisation (ILO).

In the Further Education and Training (FET) Act of 1998, RPL is seen as a mechanism to gain access to programmes in the FET band. This Act is underpinned by principles of redress and access in education. However, the 2009 report by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) raised cautious optimism about the implementation of RPL in the FET sector. Among other things, the report asserted that RPL was practised only on a limited scale, and that there was no formal policy governing RPL in this sector.

The Department of Education White Paper (1997) was promulgated with the aim of transforming the education landscape in South Africa. It was hoped that by eliminating social imbalances through higher education, South Africans would be empowered to engage effectively in globalisation (Kistan, 2002). The Council on Higher Education (CHE) report (2001) emphasised the importance of this White Paper by stating that it created a system in which "higher education could provide greater access to learning opportunities at various levels, across a range of programmes and entry points" (p. 9). As a basis for social justice, this will lead to the creation of opportunities for individuals who have been educationally and/or academically disenfranchised by the previous apartheid dispensation.

To standardise the implementation of RPL in the Higher Education and Training sector SAQA, in consultation with CHE and the Department of Higher Education, developed an RPL national policy. This national policy underscores the need for universities to establish discipline specific RPL policies for various academic departments or schools. Given that the development of RPL in South Africa is sector specific to allow for institutional autonomy and contextual practices, the establishment of an enabling policy environment in LIS schools will not only improve efficiency in RPL provision but will also enhance the credibility of the RPL assessment process.

Research methodology

In this study, following Creswell (2014), I used a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods to collect data from all the 10 LIS schools in South African Higher Education. The data was collected from the respondents through a survey questionnaire based on the list of statements (themes) taken from the SAQA RPL policy document (2013), and content analysis (Bryman, 2011) of the institutional RPL policies. I triangulated the results from the survey questionnaire with content analysis results in order to supplement the survey results and thus provide greater richness and depth to the findings of the study. The respondents included the head/chair of departments/schools, senior lecturers, lecturers, junior lecturers, and RPL officials because of their knowledge and experience of RPL practices. The documents that were analysed included policy documents from the Higher Education and Training National Department as well as related institutional documents. A total of 76 respondents were targeted; these consisted of 10 RPL officials and 66 academic staff recommended by the heads/chairs of the schools/departments. Of the RPL officials, five did not respond along with three academic staff. As a result, there were 68 respondents: five professors; one associate professor; 44 senior lecturers; 13 lecturers; and five RPL officials.

Findings

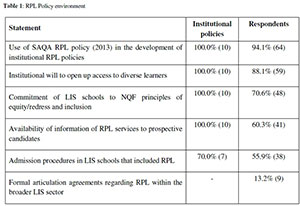

This section presents in a thematic mode integrated findings yielded by questionnaires and the content analysis of institutional RPL policies. The variables measured by the study are key constructs for facilitating or enabling an RPL policy environment. Table 1 below indicates the percentages of respondents who agreed with each statement and the number of institutions that had policies that reflected these statements.

Discussion

Use of SAQA RPL policy (2013) in the development of institutional RPL policies

There was an indication in this study that RPL policies in the different universities where the LIS schools are located were based on the SAQA policy (2013) as required by the SAQA Act of 1995. The analysis of the institutional RPL policy documents further indicated that, in addition to the SAQA Act of 1995 and related Acts, six out of ten institutional policy frameworks make reference to several regulations and Acts that capture the importance of RPL in the South African Higher Education and Training sector. These Acts and regulations include the Employment Equity Act (Act 55 of 1998), Skills Development Act (Act 97 of 1998), Higher Education Act of 1997, and the National Plan for Higher Education (2001). Using SAQA policy (2013) guidelines in the formulation of institutional RPL policies and the inclusion of related Acts and regulations not only aims to help standardise RPL practice in the LIS sector but also creates an enabling environment for effective and efficient RPL practice in LIS schools in South Africa. Standardisation of RPL practices is essential if we are to avoid ad hoc procedures that will compromise academic standards, articulation opportunities, academic ethos, throughput, and pass rates.

Institutional will to open up access to diverse learners

As indicated earlier, one of the main purposes of RPL in South Africa is to open up access to education and training and to effect the redress of past injustices. In the legislation, regulations, and criteria and guidelines documents (SAQA, 2013), RPL is put forward as one of the key strategies to ensure equitable access to higher education and training. In addition, RPL is seen as one of the mechanisms with the potential to ensure redress of past unjust educational practices in South Africa. The findings of the study indicate that 88.1% of the respondents acknowledged that there was institutional understanding, leadership, and will to support LIS schools to open up access to diverse learners who display diverse needs and capabilities. The commitment of institutions was reflected in all the institutional RPL policy documents and this was also confirmed by most respondents (88.1%) from the different LIS schools. There seemed to be greater acknowledgement (88.1%) in the LIS schools of RPL as a tool of access to learning in higher education. However, a few respondents (11.9%) indicated that the institutional standpoint on RPL was not very positive.

Commitment to the principles of equity/redress and inclusion

The content analysis of the institutional RPL documents found that, in principle, there was reference to equity, redress, and inclusion in all the documents. However, when asked about commitment to the principles of equity, redress, and inclusion, approximately 70.6% of the respondents indicated that RPL procedures, processes, and practices complied with SAQA RPL policy (2013) requirements. This show of commitment to the principles of equity/redress will benefit potential RPL candidates in terms of access to higher education and training.

Availability of information of RPL services to prospective candidates

RPL providers such as universities and/or academic departments are required to provide potential RPL candidates with information relating to the general overview of RPL services, details of costs, guidelines for collecting evidence, and particulars about the application process (SAQA, 2013). In addition, the would-be implementers, as required by the policy, are supposed to inform clients about RPL prior to, and on enrolment. The results of the study indicated that only 60.3% of the respondents agreed that information about RPL services was widely available to potential candidates. However, only half (50%) of the institutional RPL policy documents analysed contained promotional information about RPL assessment. Overall, there seemed to be low levels of awareness about RPL services and their benefits in LIS schools in South Africa. RPL service providers or training organisations have different views on RPL applicability and implications.

• There is a lack of clarity between the institution and the various departments on the responsibility to market RPL;

• there is fear that RPL is a political prescript that is likely to compromise academic standards;

• RPL outcomes are not valued as equal to formal training outcomes;

• confidence to undertake the process is lacking, and knowledge and understanding of the merits of RPL are lacking; and

• there is a lack of institutional leadership and commitment.

The downside to ineffective publicising of RPL is that the uptake will be low since the intended beneficiaries may not know about the possibilities and opportunities available to them. This means that RPL service providers may be perpetuating social exclusion and defeating their own mandate of upholding social justice. It has emerged in the literature that there is low RPL uptake in the Higher Education and Training sector. The RPL phenomenon still needs to be publicised vigorously to create awareness and understanding especially in developing countries like South Africa where there is a dire need for social transformation.

Admission procedures in LIS schools which included RPL

The results of the survey indicated, on the one hand, that the admission procedures of 6 out of 10 LIS schools (55.9%) were not inclusive of non-matriculated learners. On the other, the institutional RPL document analysis revealed that seven out of 10 (70%) RPL policies used by LIS schools made reference to this aspect. What these results show is that commitment to the principles of equity/redress (70%) as reflected in the institutional RPL policy documents does not, in practice, translate into the implementation of admission procedures that are inclusive of non-matriculated learners.

Formal articulation agreements regarding RPL in the broader LIS sector

In this study, the survey results indicated that only 13.2% of the respondents acknowledged that formal articulation agreements among LIS schools exist while none of the institutional RPL policy document (0.0%) reflected any formal articulation agreements among them. The significance of formal articulation agreements among LIS schools lies in ensuring that there is recognition of RPL results/outcomes in the LIS sector to enhance student mobility. Despite 13.2% of the respondents indicating that there were formal articulation agreements among LIS schools, the results are a clear indication of deviation from the SAQA RPL policy (2013) which requires LIS schools to establish formal articulation agreements among themselves in relation to the chosen field of learning and qualifications.

Conclusions

In my study, I found out that there are islands of good practice in terms of compliance with all the legislative framework themes discussed above regarding the implementation of RPL in South African LIS schools but there are very few formal articulation agreements regarding RPL in the broader LIS sector.

I recommend that the Department of Higher Education, together with CHE and SAQA, conduct regular monitoring and evaluation processes of RPL implementation in LIS schools to encourage compliance with prevailing legislative frameworks. Further, periodic RPL accreditation processes could also be used to great effect to ensure that LIS schools comply, failing which their accreditation to offer RPL services could be reviewed. This will help create an enabling environment, which is a prerequisite for an effective and credible recognition of the RPL process in LIS schools. This will take greater cooperation among all stakeholders if we are to create an enabling environment for the implementation of RPL in the South African Higher Education and Training sector, including LIS schools.

References

Australian Qualifications Authority (AQF) Advisory Board. (2002). Australian qualifications framework implementation handbook (3rd ed.). Carlton South, Victoria, AU: AQF Advisory Board. [ Links ]

Bowman, K., Clayton, B., Bateman, A., Knight, B., Thomson, P., Hargreaves, J., & Enders, M. (2003). Recognition of prior learning in the vocational education and training sector. Adelaide, AU: National centre for vocational education research (NCVER). [ Links ]

Bryman, A. (2011). Business research methods (3rd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Council for Higher Education (CHE). (2001). A new academic policy for programmes and qualifications in higher education. Pretoria, RSA: CHE. [ Links ]

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. [ Links ]

Department of Arts and Culture (DAC) and National Council for Library and Information Services (NCLIS). (2010). The demand for the skills and the education and training currently provided by higher education institutions for librarians, archivists, records managers and other information specialists. Retrieved from http://dac.gov.za/publications/reports/2010/Final%20Report%2015%20March201pdf

Department of Education. (1998). Further Education and Training Act, no. 98 of 1998. Pretoria, RSA: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Department of Labour. (1998a). Employment Equity Act, no. 55 of 1998. Pretoria, RSA: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Department of Labour. (1998b). Skills Development Act, no. 97. Pretoria, RSA: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Du Pré, R. (2004). Coping with changes in higher education in South Africa. Retrieved from http://face.stir.ac.uk/paper101-RoydePre000.htm

Harris, J. (1997). The recognition of prior learning (RPL) in South Africa: Drifts and shifts in international practices: Understanding the changing discursive terrain. Cape Town, RSA: Department of adult education and extra-mural studies, University of Cape Town.

Hlongwane, I. K. (2014). Recognition of prior learning (RPL) implementation in library and information science (LIS) schools in South Africa (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of South Africa, Pretoria, RSA. [ Links ]

International Labour Organisation (ILO). (2005). Skills, knowledge and employability: Recognition of prior learning policy and practice for skills learned at work. Skills working paper no. 21. Geneva, CHE: ILO. [ Links ]

Kistan, C. (2002). Recognition of prior learning: A challenge to higher education. South African Journal of Higher Education, 16(1), 169-173. [ Links ]

Nassimbeni, M., & Underwood, P. G. (2007). Two societies: Duality, contradictions and integration: A progress report on South Africa. The International Information and Library Review, 39(2), 166-173. [ Links ]

New Zealand Qualifications Authority (NZQA). (2003). Prior learning for learners. Wellington, NZ: NZQA. [ Links ]

Ocholla, D., & Bothma, T. (2007). Trends, challenges and opportunities for LIS education and training in Eastern and Southern Africa. New Library World,108(12), 55-78. [ Links ]

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2009). Recognition of non-formal and informal learning: Country note for South Africa. Paris. FR: OECD. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/edu/recognition [ Links ]

Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA). (2013). Safeguarding standards and improving the quality of UK higher education. Gloucester, UK: QAA. [ Links ]

South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA) Act. (1995). Pretoria, RSA: Government Printer.

South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA). (2002). Criteria and guidelines for the implementation of the recognition of prior learning. Pretoria, RSA: Government Printer. [ Links ]

South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA). (2013). Revised RPL policy. Pretoria, RSA: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Stilwell, C. (2009). Mapping the fit: Library and information services and national transformation agenda in South Africa. Part II. South African Journal of Library and Information Science, 75(1), 1-11. [ Links ]

Underwood, P. G. (2003). Recognition of prior learning (RPL) and the development of library and information science profession in South Africa. South African Journal of Library and Information Science, 69(1), 49-54. [ Links ]

Van Kleef, J. (2011). Canada: A typology of prior learning assessment and recognition (PLAR) research in context. In J. Harris, M. Breier, & C.Wihak (Eds.), Researching recognition of prior learning: International perspectives. Leicester, UK: National Institute of Adult Continuing Education (NIACE). [ Links ]

Young, M. (2001). The role of national qualifications frameworks in promoting lifelong learning: Discussion paper. Paris: Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). [ Links ]

Wheelahan, L., Dennis, N., Firth, J., Miller, P., Newton, D., Pascoe, S., & Brightman, R. (Eds.). (2003). A report on recognition of prior learning (RPL) policy and practice in Australia. Australian Qualifications Framework Advisory Board (AQFAB), Lismore, AU: Southern Cross University. [ Links ]

Received: 11 September 2018

accepted: 24 April 2019