Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Education (University of KwaZulu-Natal)

versão On-line ISSN 2520-9868

versão impressa ISSN 0259-479X

Journal of Education no.74 Durban 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2520-9868/i74a03

RESEARCH ARTICLES

The school economics textbook as programmatic curriculum: An exploited conduit for neoliberal globalisation discourses

Suriamurthee Moonsamy MaistryI; Roshnee DavidII

ISocial Sciences Education, School of Education, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pinetown, South Africa Maistrys@ukzn.ac.za http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9623-0078

IISocial Sciences Education, School of Education, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pinetown, South Africa. University of KwaZulu-Natal (PhD student). Roshneedavid@yahoo.com

ABSTRACT

In South African schools, the textbook serves as an indispensable trustworthy source of disciplinary content knowledge. While the constitution and vetting of such knowledge is subject to the state's textbook publication protocols as they relate to screening for discrimination and prejudice in relation to race, gender, sexuality etc., there is a dearth of understanding of covert ideological hegemony embedded in the textbook as revered artefact. This programmatic curriculum, the school textbook, has received minimal attention from local curriculum theorists and researchers, so it is likely to masquerade as innocent purveyor of selected (or subversive) ideology. In an attempt to unveil the subtext, we report on a study that set out to examine the discourses of globalisation that manifest in selected contemporary high school economics textbooks. The study draws on the tenets of Fairclough's Critical Discourse Analysis to reveal how particular knowledge selections romanticise globalisation through the discourses of financescapes, presenting and perpetuating a neoliberal discourse as normal and acceptable. We present reflections on how critical curriculum theory might offer insights for classroom pedagogy, especially as it relates to re-embracing the critical pedagogy project in South African schools.

Keywords: critical discourse analysis, globalisation, neoliberalism, textbooks

Introduction

In this article we report on a study that focused on a commonly used, taken-for-granted artefact in the school curriculum-the school textbook. As an indispensable resource especially in South African schools where both teacher content and pedagogical knowledge have remained stubbornly fragile, the textbook continues to represent the trusted source of content knowledge. The competitive school textbook industry involves many publishing houses all vying for a share of this captive market. The overarching criterion for determining whether a textbook gets approved for inclusion on the Department of Basic Education's preferred list, is its compliance to, and alignment with, the National Curriculum Statement (NCS) Curriculum and Assessment Policy (CAPS) requirements. Textbook authors then use NCS(CAPS) as a guiding template to select disciplinary content and flesh out a programmatic curriculum for use in classrooms. While textbooks are subjected to a mandatory technical, tick-box style protocol, of concern is the fact that limited attention is paid to unearthing the subtext of selected content as it relates to the inherent value systems and the worldviews that it presents; this is the focus of our study. As a tentative exploration into this field of textbook research, we sampled a selection of contemporary Grade 12 economics textbooks.

As can be expected, the study of textbooks presents us with a multitude of foci. For this study we purposively selected content that dealt with the topic of globalisation. It is a phenomenon that is often uncritically punted as an ideal that should be pursued by economists, entrepreneurs, and politicians as necessary and beneficial. This study, therefore, troubles this assumption by engaging a Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) framework to examine the tensions inherent in what masquerades as innocent, neutral economics content knowledge particularly with regard to the representations of the discourses of globalisation in school economics textbooks. As a consequence, in this article we offer a sober assessment of the extent to which Africanisation and decolonisation debates have infused school curriculum policy and the extent to which the official NCS(CAPS) in particular might present as a major obstacle to this agenda.

Globalisation: A brief overview of the conceptual terrain

Globalisation as a phenomenon has gained currency and its purported benefits traction in multiple spheres of economic and social life. One might well argue that the process of globalisation began when, for the first time, human beings began to traverse what were for them new geographical spaces. In the past three decades, with the explosion of technology in transport and especially communication, the concept of globalisation has shifted well beyond rudimentary lay understandings to the point that selective appropriations of this concept have been deployed to advance particular agendas.

Globalisation is a multi-faceted phenomenon (Stromquist & Monkman, 2014). It may be viewed as a process that entails a restructuring and rearranging of social relationships for the advancement of global capitalism and the functioning of a market economy (Castells, 2010; Foucault & Senellart, 2008). Blommaert (2003) has described the phenomenon as a scalar process during which events are either at macro (global) level or at micro (local) level. It also refers to the process of reducing barriers between countries and encouraging closer economic, political, and social interaction (Mittelman, 2000).

In the economic arena, referred to as financescapes (Appadurai, 1990; 1996), prevailing practices feature unencumbered free markets, private enterprise, and increased foreign investment (Bazzul, 2012; Gruen, O'Brien, & Lawson, 2010; Stromquist & Monkman, 2014). An economic theory held by neoliberal protagonists advocates that free trade and capital flows generate a more efficient distribution of scarce world resources resulting in greater consumption and output than that generated under protectionism (Kapstein, 2000).

Even as people around the world are affected by transnational policies, attempts to restructure and rearrange social relations away from the public sphere to the control of global capitalism and the market economy are seen to be under the pervasive influence of neoliberalism (Bourdieu, 1998; Foucault & Senellart, 2008). Furthermore, the expansion of ties between and among countries has resulted in the enrichment of powerful corporations at the expense of ordinary workers and citizens, while increasing inequalities in the economic, political, and social domains between and among nations (Aguirre, Eick, & Reese, 2006). The impacts of globalisation are also more widely geographically dispersed through the activities of such groups as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund since these groups have often externally imposed a neoliberal model in the South as a condition for obtaining development loans (Aguirre, Eick, & Reese, 2006; Davies & Bansel, 2007; Fioramonti, 2017).

Some writers are sceptical about the economic benefits of globalisation (see Amadi, 2013; Kapstein, 2000; Lee, 2011; Stromquist & Monkman, 2014) and see it as increasing dependency because of its creation of social problems in developing countries. As Bauman (1998), has pithily put it,

globalisation is on everybody's lips; a fad word fast turning into a shibboleth, a magic incantation, a pass-key meant to unlock the gates to all present and future mysteries. For some, 'globalisation' is what we are bound to do if we wish to be happy; for others 'globalisation' is the cause of our unhappiness. (p. 1)

In South Africa more than twenty years into post-apartheid governance, the expectations of prosperity for most South Africans remain a pipe dream since poverty, unemployment, and inequality abound (Vally & Spreen, 2014). With a Gini coefficient of 0.63 (Oxfam, 2018), South Africa shows the highest inequality levels in comparison to countries with comparable data (Dessus & Hanusch, 2018). According to Vally and Spreen (2014), globalisation has increased this abysmal inequality with its attendant global capitalist labour markets.

In relation to knowledge presented to readers via textbooks, Akincioglu (2012), Amadi (2013), Bazzul (2012) and Lee (2011) have argued that critical engagement is needed to counter the legitimisation of the discursive practices of globalisation, especially by educators, teacher educators, and students. In his examination of excerpts from science textbooks, Bazzul (2012) found that the ideologies of neoliberalism and globalisation were present in taken-for-granted ways. This was evident, for example, in claims that science was driven by competition and presented as a statement of fact thereby promoting and reinforcing the importance of competition rather than collaboration. Bazzul concluded that without critical engagement, the neoliberal agenda can be reinforced. It is of significance that in many parts of South Africa, students learn only through a close interaction with textbooks. The authority of these textbooks is accepted uncritically, and this suggests the need for a close examination of textbooks to ascertain whether they are what Moran and Henning (2011) have described as servants of a market economy.

Studies of Business Education and Accounting literature have also shown an ideological bias (Ferguson, Collison, Power, & Stevenson, 2009; McPhail, 1996; Zhang, 2012). In his study McPhail (1996) observed that "accounting departments appear to function as ministries of propaganda, subliminally instructing students in the rudiments of neo-classical market economies" (p. 278). Likewise, Ferguson et al. (2009) said that accounting textbooks lend themselves easily to the criticism that they are tools of neoliberal capitalism. Textbooks can become instruments of propaganda when they promote and advance the ideologies of neoliberalism, globalisation, and capitalism and inculcate in students a particular worldview that draws on the values and assumptions of capitalism.

Zhang (2012) found that accounting discourses and policies in China are ideologically formed to further particular socio-political programmes and that accounting textbooks and related literature are also instruments of neoliberalism. The adoption of globalised accounting practices by the Chinese government reveals that it actively entrenches the ideological precepts of neoliberalism. However, recent research (Oxfam, 2018) confirms that income inequality in China has increased over the last 30 years. For instance, even though many Chinese people are employed because of globalised production, their well-being has not improved given the unequal income distribution (Jovanovic, 2010). Zhang (2012) has commented that in addition to textbooks and policies that appear to be ideologically unbiased and impartial, the importance of what is left unsaid or what is hidden as a subtext is more powerful than what is overtly stated.

It would appear that globalisation discourses take on a particular persuasiveness in the literature. The extent to which this pattern is prevalent in Grade 12 economics school textbooks is of significance here.

The methodological approach

The methodological framework for this study was informed by Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) as envisaged by Fairclough (1989; 1992; 2003) and incorporates a conceptual framework based on Appadurai's notion of scapes (1990; 1996), here, financescapes. CDA as a multidisciplinary research methodology has become increasingly popular in studies of texts and semiotic data (visual, spoken, or written) in the public sphere (see Huckin et al., 2012; Wodak & Meyer, 2009). For Fairclough (2003) CDA is a problem-oriented research discipline with an interest in issues of power, injustice, and cultural or political-economic changes in society. Revealing ideologies implicitly rooted in texts, CDA also examines the implementation of power in the construction and interpretation of texts (Widdowson, 2000). Blommaert (2005) has maintained that power, especially institutional power, is central to CDA and that it analyses the structural relationship of power and control as portrayed by language. This allows for a critical and constructive analysis that exposes "systematic asymmetries of power and resources between speakers and listeners and between readers and writers [that] can be linked to the production and reproduction of stratified political and economic interests" (Luke, 1996, p.12). Also, of interest here is that that dominant discourses in society tend to replicate these anomalies (Luke, 1996), in, for example, the bias towards global trade being seen to be natural and essential. CDA can be implemented as a tool to challenge these positionings and representations of institutional power.

Of particular relevance to this article is Fairclough's (2009) identification of five general claims about discourse as a facet of globalisation.

1) Discourse can represent globalisation, giving people information about it and contributing to their understanding of it.

2) Discourse can misrepresent and mystify globalisation, giving a confusing and misleading impression of it.

3) Discourse can be used rhetorically to project a particular view of globalisation that can justify or legitimise the actions, policies, or strategies of particular (usually powerful) social agencies and agents.

4) Discourse can contribute to the constitution, dissemination, and reproduction of ideologies, which can also be seen as forms of mystification but have a crucial systemic function in sustaining a particular form of globalisation and the (unequal and unjust) power relations that are built into it.

5) Discourse can generate imaginary representations of how the world will be or should be in strategies for change which, if they achieve hegemony, can be operationalised to transform these imaginaries into realities, i.e. particular actual forms of globalisation. (p. 321)

The fourth claim is particularly relevant to this article since it focuses more substantially on how discourse constitutes, disseminates, and reproduces a particular view of globalisation.

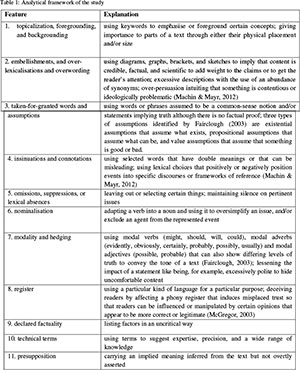

The textual analysis here focuses on the linguistic features of nominalisation, modality, foregrounding and backgrounding, omission, presupposition and assumption, overlexicalisation, and lexical register (Fairclough, 1989; 1992; 2003; Machin & Mayr, 2012). The table below provides an explanation of the analytical framework with the feature in the left column and an explanation in the right.

The four Grade 12 economics learner textbooks analysed are Economics (Bantjes, Burger, Engelbrecht, & Ross, 2013), Economics (Chaplin, Serfontein, & van Zyl, 2013), Economics (Levin, Pretorius, & Viljoen, 2014) and Clever Economics (Eloff, Nel, & Pretorius, 2013) referred to hereafter as textbooks A, B, C, and D. Following Ritchie and Lewis (2003), the purposively sampled textbooks were handpicked based on their accessibility and relevance. Furthermore, these textbooks, all of which were published in South Africa, were chosen because they are the primary resource used in the cluster area in which the research site is located.

Financescapes as dominant discourse

The discourse of financescapes (Appadurai, 1990; 1996) was evidenced through the use of the words and phrases capital, trade, economies of scale, costs, world markets, economy, price, and business. While it may be argued that these are typical of the discipline of economics, their manipulation to construct particular world views is a cause for concern. The globalized neoliberal discourse of finance and capital was pervasive in the selected Grade 12 economics textbooks. Narrow interpretations and applications of the concept of efficiency for example, are projected. In textbook C in a section detailing the reasons related to supply in the foreign exchange market, the text employs the technique of overlexicalisation and overwording. This excessive description suggests the preoccupation of the text with the notion that foreign trade leads to efficiency.

Supply also depends on the efficiency with which goods and services are produced. Businesses that are efficient in production supply goods at lower prices and this reduces the opportunity cost of acquiring them. Factors that impact on efficiency include the quality of the labour force, the availability of capital and natural resources, the use of technology, specialization, physical infrastructure, economic freedom, competitiveness, capital and stable government. (p. 76)

The text portrays efficiency as a valuable and splendid phenomenon and aspiration, emphasising the multiple factors that impact efficiency, yet efficiency can lead to the reality of the redundancy of human capital, poverty through job losses, and other kinds of trauma like deprivation and humiliation. There is a pointed silence about, and omission of facts relating to, the negative effects of efficiency including the fact that efficiency warrants the manufacturing of a product at the lowest cost to ensure the maximisation of profit. This suppression of pertinent issues reveals ideology at work since the inclusion of the above implications of efficiency would change the tangent of the discourse. What is left unsaid is notable by its absence. Also strengthening the impression of declared factuality, is the uncritical manner in which the factors are listed, a manner unlikely to be challenged by school pupils, especially since textbooks are seen to be an uncontested source of knowledge. The ideological assumptions that underpin the concept of efficiency are thus likely to go unchallenged. The use of technical terms in this list suggests an expertise, precision, and wide range of knowledge. Yet these are in fact presuppositions that these factors impact efficiency. Furthermore, hedging, the use of verbs in the present tense, and the lack of modality (modality being the expression of the level of commitment to what is said) implies an absolute certainty of facts. Also notable is the use of the phrase economic freedom to insinuate something appealing since it is a concept that people desire and for which they would strive, especially in the light of the poverty that many people in South Africa face. The phrase also implies the conflation of economic growth with the liberal doctrine of freedom that, in present day South Africa, might be seen to be a highly desirable attribute. Choice appears good since it is aligned with freedom. Herein lies the successful use of a presupposition, carrying an implied meaning inferred from the text but not overtly asserted. Thus, this lexical selection legitimates this purported noble value of efficiency. On page 79 of textbook C is a further example of the text's preoccupation with the concept of efficiency. Described as an effect of international trade the elaboration reads,

unrestricted international trade increases competition. Competition increases efficiency because it demands the elimination of unnecessary costs and all wastage. Increases in efficiency result in lower prices. Lower prices mean that income can buy more goods and services. The standard of living therefore increases.

Clearly evident in this extract are the features of foregrounding and topicalisation used to give prominence to the notion that international trade leads to efficiency. Because of the physical placement of the keywords (unrestricted international trade), the text prominently positions them to emphasise that free and open markets will lead to efficiency and, in the process, insinuates that any other economic system will not result in an increased standard of living. The text also employs the stratagem of nominalisation to further amplify this concept. This is evidenced in the use of the verb increase which is then used as the plural noun, increases. Instead of representing competition as a process (to compete) this particular usage represents it as a personified entity (competition). A consequence of this is the resultant exclusion of agents-people who are responsible for the initiation or the pursuit of such a process. Not only does this nominalisation obfuscate agency but the use of the modal form (can buy) also presents income and competition as personified entities replacing actual agents. Fairclough (2003) notes that these linguistic features are typical of the narrative of the new global economy in which human agency and responsibility are removed. Of note is the silence as to the ramifications of unbridled globalisation (see Machin & Mayr, 2012). An examination of the term competitive reveals that this concept seems to be accepted as a common-sense, generally accepted value. Moreover, the inclusion of the word competitive invokes the mantra of neoliberalism (Fairclough, 2003) that favours the economically powerful in society. Since it is seen as an authoritative source of knowledge and its readers as potential receivers of such knowledge, the power of the textbook as an influential ideological tool should not be under-estimated. In this instance, it serves the purpose of legitimating the competitive nature of international trade as something desirable and necessary for economic survival.

Furthermore, given the absence of agents the text makes it seem as though increased living standards just happen because of competition and efficiency. Added to this is the fact that these nominalisations are in danger of becoming common sense notions that can become part of the discourse of improved living standards. Through the suppression and silence of the negative consequences of international trade, the text deliberately misrepresents reality. As such, textual silence does covert ideological work. Page 68 of textbook B lists the effects of being/not being competitive in international trade.

• International trade is an important stimulant for economic growth of a country. Demand for certain products will increase as trade increases, leading to increased production, more job opportunities, increased income and increased expenditure. This will result in a higher economic growth rate.

• Infrastructure, such as harbour and transport networks, will be developed in order to move the high volumes of goods.

Industries in countries that do not have the ability to compete in global markets may fail. These industries will not be able to compete with the lower prices of imported goods on local markets.

A tone of certainty and factuality is invoked with the use of verbs in the present tense (is, gives) and the use of the high-commitment auxiliary modal will. The writers' authoritative stance thus presents these effects as inevitable and certain. An implicit juxtaposition is set up between countries that are able to compete on global markets and industries in countries that do not have this ability. The benefits of international trade are foregrounded-these countries are winners and the losers are those that do not engage in international trade. The insinuation is that good things will inevitably happen if international trade is encouraged and bad things (industries ... may fail) will happen if countries do not compete and engage in international trade. Moreover, the inclusion of the word compete alludes to the values of neoliberalism as mentioned above (see Fairclough, 2003), which advances the interests of the powerful. Furthermore, the rationalisation of international trade is legitimated by a clear specification in the form of the grammatically unnecessary connecting phrase in order to. The development of infrastructure is emphasised to show that this is an effect of international trade. Thus, the writers' legitimation of the ideology of international trade is clearly evident in this section.

Textbook D also elaborates on effective competition and efficiency as an effect of international trade.

Free trade between countries increases competition. It fuels efficiency, because it eliminates extra costs and wastage. This results in lower prices. (p. 72)

Both this extract and the example from page 79 of textbook C make use of personification to bestow on competition a sense that it is a living and dynamic entity. The human-like quality is evoked through the use of the phrases it demands, it fuels, and it eliminates. This can have the same effect as does the use of nominalisation since it obscures and conceals the agents who actually are responsible for competition and who might well be held responsible for its negative outcomes. It serves as an effective tool to persuade readers to view competition and efficiency as highly valued concepts. On page 107 of textbook D there also is a portrayal of the policy of free trade as an unquestionably efficient trade policy. Under the heading Economic efficiency, we read that

free trade allows industries to maximise economies of scale, reduce costs, and become competitive in world markets. It benefits the global economy by distributing labour effectively and creating economic efficiency. World production and economic welfare increase and markets grow. Producers compete to find the best production methods that cut costs and improve the quality of goods. This boosts innovation.

Of significance is the fact that there is not a single use of modal verbs, modal adverbs, or modal adjectives here. This signals the apparent belief of the writers that this is the absolute truth and that the positive outcome is a certainty that will result from free trade. In addition, the use of the present tense, authoritatively asserts that economic efficiency benefits the economy globally but suppressed is the actuality that this economic efficiency has resulted in the subordination of economic equality while compromising the quality of the life of the poor. The nominalisation that occurs in the third sentence (worldproduction) represents a process as an entity through the transformation of the possible clause with its significant verb (employees in the world produce) into the noun clause world production ... [increases]. This results in the exclusion of agency regarding who exactly produces, what is produced, whose welfare increases, and which markets grow. Fairclough (2003) notes that nominalisation is useful when we are generalising about an event without offering factual evidence to support the argument, a technique deployed in this instance in the representation of free trade. Innovation is also portrayed as a valued goal and the processes that boost this concept are presented as highly desirable thus rationalising and legitimating the policy of free trade; the use of the verbs in the present tense and the lack of modalities reinforce this portrayal of free trade as the categorical truth. The effect is that these linguistic devices once again position the textbooks as factual and knowledgeable.

Efficiency is also an attribute that is alluded to in Textbook A on page 93, in the demand and supply reasons for international trade.

Demand reasons

The country may not be able to produce required goods and services as efficiently as another country, meaning that the cost of production would be higher for the country than if these goods and services could be bought from a country that can produce them at a reasonable price

Supply reasons

The country may be able to produce required goods and services very efficiently compared with another country, meaning that the cost of production would be lower for this country and it would be possible to meet both local and foreign demand.

The concept of efficiency is raised through the use of the phrases as efficiently as another country and to produce required goods and services very efficiently. These articulations as presented as existential and propositional assumptions-something exists that leads to what can be-that assume that a foreign exchange market is responsible for efficiently produced goods and services. The use of the value assumption assumes that this efficiency is required for the improved economic welfare of a country. What is suppressed and/or omitted is reference to the consequences of this movement away from the local country. Of significance is the fact that large international companies that can move and establish themselves around the globe in search of greater profits through lower labour costs are the ones who are the beneficiaries of increased foreign trade. These large corporations move to newer markets to take advantage of that country's lower costs of production (Ar, 2015).

Discussion and concluding comments

A significant meta-observation from the full corpus of data analysed for this study is that the neoclassical economics canon continues to reign supreme in the South African high school curriculum. In fleshing out the official Further Education and Training economics curriculum as contained in the NCS(CAPS), textbook writers have also invoked a distinct neoliberal discourse, in line with the new democracy's strategic neoliberal economic direction (Harvey 2010). It then raises the pertinent question of the extent to which the aspirational Africanising and decolonising agenda might develop any traction in the schooling sector, given that the official curriculum policy on which the high-stakes matric examination is based is likely to be tinkered with even in rudimentary ways. While this presents as a pessimistic and defeatist position to assume for this agenda, it brings into sharp focus how entrenched structural arrangements might hinder the attainment of this objective.

From the data and analysis, it can be seen that the selection of particular kinds of knowledge, its lexical arrangement, ordering, and emphases project and foreground a very specific world view. In the examples we have used, the concept of efficiency is manipulated to lead the potential reader into an understanding of a somewhat romanticised, biased, and uncritical version of the phenomenon of globalisation.

The redressing of historic imbalances and redistribution policies was a major challenge facing the post-apartheid government of South Africa in 1994. The new government had to broaden access to social resources for groups that had been and were still marginalized through the policies of apartheid so as to uphold the principles of inclusivity and social justice (Fioramonti, 2017; Green & Naidoo, 2008). Initially the government had the newly created equity-oriented Reconciliation and Development Planning (RDP) unit which sought to address the social ills of the poor and to allow them access to basic services. This policy was then abandoned in favour of the neoliberal Growth Employment and Redistributive (GEAR) programme which advocated economic growth through the freedom of the market, entrepreneurship, decreasing barriers to trade, liberalising capital movement, and global trade integration (Fioramonti, 2017). However, the GEAR strategy was not effective in reducing poverty and creating employment largely because of its neoliberal approach. The present policy, the National Development Plan (NDP) was adopted in 2013 as a roadmap to reduce inequality and eliminate poverty by 2030.

But South Africa's exposure to the international economic world has not delivered on the promised redistributive agenda. If anything, South African society has become even more unequal, amid sustained high levels of unemployment (Fioramonti, 2017; Oxfam, 2018). So, while efficiency and globalisation appear as positive, more than two decades of trade liberalisation have not made any significant difference to the lives of the poor and destitute (Vally & Spreen, 2014). This then raises the fundamental question of whether neoliberal values such as unencumbered economic freedom for profit making, free markets, and the marketization of social services (including health) favour or fail the under classes in South African society.

There is a distinct absence of a counter-narrative in the textbooks under study. One might expect, therefore, that school teachers and learners are likely to internalise the neoliberal value system presented in them without having been given opportunities to critique its socially unjust consequences. It might be argued that students and teachers have agency and may well be able to read the sub-text. This is a somewhat optimistic position to take, especially in South Africa where teacher knowledge is a challenge and where a large percentage of school children learn under severely under-resourced and deprived conditions that may not offer opportunities for alternative thought.

This study has significant implications for a range of stakeholders in the South African education environment and certainly presents an area that is ripe for curriculum studies research. There is a dire need for critical teacher education (both in-service and pre-service) that might focus on critical approaches to school textbooks, and how they are used. School textbook writers might also benefit from a more profound understanding of how content selections and their construction for use by teachers and learners might, however inadvertently, transmit certain messages about the economic world at the expense of alternative views.

In returning to the argument in the opening paragraph of this section, we cautiously urge a re-visitation of the Critical Pedagogy project (with due cognisance of its fissures), and how it might infuse teacher education programmes. It might also signal the need to return to the principles of critical curriculum theory. This proposition opens up many research opportunities that might offer firmer empirically based theorisations as to how to advance the Critical Pedagogy project. It raises questions as to where and how to access the various points of entry and rupture as they relate to NCS(CAPS), with a view to exposing pre-selected worldviews that teacher educators, teachers, and school children consume as they ingest programmatic curriculum knowledge via the textbooks they use. It raises powerful research questions especially as it relates to the extent to which there is any invocation of critical curriculum theory in, for example, pre-service teacher education programmes, continuing professional development programmes, or even the textbook writing industry. It follows, then, that rupturing canonical curriculum theory as well as subject disciplinary canons is likely to be a formidable project. Accepting the status quo, however, is likely to impede the nation's decolonisation and transformation project.

References

Akincioglu, M. (2012). A critical approach to textbook analysis: Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) of two EAP textbooks (Unpublished master's thesis). University of St Andrews, Scotland. [ Links ]

Amadi, F. A. (2013). Discourse of globalization as a domain of colonization. Global Journal of Politics and Law Research, 1(3), 7-15 [ Links ]

Aguirre, A., Eick V., & Reese, E. (2006). Privatization and resistance: Contesting neoliberal globalization. Social Justice, 33(3), 1-5. [ Links ]

Appadurai, A. (1990). Disjuncture and difference in the global cultural economy. Theory, Culture and Society, 7(2-3), 295-310. [ Links ]

Appadurai, A. (1996). Modernity at large: Cultural dimensions of globalization. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Ar, M. (2015). Language and ideology in texts on globalization: A Critical Discourse analysis. International Journal of English Linguistics, 5(2), 63-78. [ Links ]

Bantjes, J., Burger, M., Engelbrecht, M., & Ross, D. (2013). Focus economics: Grade 12. Cape Town, RSA: Maskew Miller Longman. [ Links ]

Bauman, Z. (1998). Globalization: The human consequences. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

Bazzul, J. (2012). Neoliberal ideology, global capitalism, and science education: Engaging the question of subjectivity. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 7(4), 1001-1020. doi:10.10007/sl11422-012-9413-3. [ Links ]

Blommaert, J. (2003). Commentary: A sociolinguistics of globalization. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 7(4), 607-623. [ Links ]

Blommaert, J. (2005). Discourse. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Bourdieu, P. (1998). Acts of resistance: Against the tyranny of the market. New York, NY: The New Press. [ Links ]

Castells, M. (2010). The information age: Economy, society and culture: The rise of the network society (2nd ed.) Oxford, UK: Wiley Blackwell. [ Links ]

Chaplin, C., Serfontein, B., & van Zyl, C. (2013). Solutions for all Economics: Grade 12. Johannesburg, RSA: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Davies, B., & Bansel, P. (2007). Neoliberalism and education. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 20(3), 247-259. [ Links ]

Dessus, S. C., & Hanusch, M. (2018). South Africa economic update: Jobs and inequality (English). South Africa Economic Update, no. 11. Washington, DC: World Bank Group. Retrieved from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/368961522944196494/South-Africa-Economic-Update-jobs-and-inequality [ Links ]

Eloff, M., Nel, D., & Pretorius, A. (2013). Clever economics: Grade 12. Johannesburg, RSA: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Fairclough, N. (1989). Language and power. Harlow, UK: Longman Group. [ Links ]

Fairclough, N. (1992). Linguistic and intertextual analysis within discourse analysis. Discourse Society, 3, 193-217. [ Links ]

Fairclough, N. (2003). Analysing discourse: Textual analysis for social research. London, UK: Routledge. [ Links ]

Fairclough, N. (2009). Language and globalization. Semiotica, 1(4), 317-342. [ Links ]

Ferguson, F., Collison, D., Power, D., & Stevenson, L. (2009). Constructing meaning in the service of power: An analysis of the typical mode of ideology in accounting textbooks. Critical Perspectives in Accounting, 20, 896-909. [ Links ]

Fioramonti, L. (2017). Wellbeing economy: Success in a world without growth. Johannesburg, RSA: Pan Macmillan. [ Links ]

Foucault, M., & Senellart, M. (2008). The birth of biopolitics: Lectures at the Collegede France, 1978-1979. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Green, W., & Naidoo, D. (2008). Science textbooks in the context of political reform in South Africa: Implications for access to science. International Journal of Science Education, 19, 235-250. [ Links ]

Gruen, D., O'Brien, T., & Lawson, J. (2010). Globalisation, living standards and inequality: Recent progress and continuing challenges. Sydney, AU: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Harvey, D. (2010). Social justice and the city. London, UK: University of Georgia Press. [ Links ]

Huckin, T., Andrus, J., & Clary-Lemon, J. (2012). Critical discourse analysis and rhetoric and composition. College Composition and Communication, 64(1), 107-129. [ Links ]

Jovanovic, M. N. (2010). Is globalisation taking us for a ride? Journal of Economic Integration, 25(3), 501-549. [ Links ]

Kapstein, E. B. (2000). Winners and losers in the global economy. International Organization, 54(2), 359-384. [ Links ]

Lee, I. (2011). Teaching how to discriminate: Globalization, prejudice and textbooks. Teacher Education Quarterly, 38(1), 47-63. [ Links ]

Levin, M., Pretorius, E. & Viljoen, R. (2013). Enjoy Economics: Grade 12. Cape Town, RSA: Heinemann. [ Links ]

Luke, A. (1996). Text and discourse in education: An introduction to Critical Discourse Analysis. Review of Research in Education, 21, 3-48. [ Links ]

Machin, D., & Mayr, A. (2012). How to do critical discourse analysis. London, UK: Sage. [ Links ]

McGregor, S. L. T. (2003). Critical discourse analysis: A primer. Retrieved from http://www.kon.org/archives/forum/15-1/mcgregorcda.html

McPhail, K. (1996). Accounting education and the ethical construction of students: A Foucaldian perspective. Critical Perspective on Accounting, 10(5), 833-866. [ Links ]

Mittelman, J. H. (2000). The globalization syndrome: Transformation and resistance. New Jersey, NY: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Morgan, E., & Henning, E. (2011). How school history textbooks position a textual community through the topic of racism. Historia, 56(2), 169-190. [ Links ]

Oxfam International. (2018). Reward work, not wealth. London: UK: Oxfam. [ Links ]

Ritchie, J., & Lewis, J. (2003). Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. London, UK: Sage. [ Links ]

Stromquist, N. P., & Monkman, N. (2014). Defining globalization and assessing its implications for knowledge and education, revisited. In N. P. Stromquist & K. Monkman (Eds.), Globalization & education: Integration and contestation across cultures (2nd ed.) (pp 1-18). New York, NY: Rowman & Littlefield. [ Links ]

United Nations Development Programme. (2013). Human Development Report 2013: The rise of the South: Human progress in a diverse world. New York, NY: UNDP. [ Links ]

Vally, S., & Spreen, C.A. (2014). Globalization and education in post-apartheid South Africa: The narrowing of education's purpose. In N. P. Stromquist & K. Monkman (Eds.), Globalization & education: Integration and contestation across cultures (2nd ed.) (pp 267-284). New York, NY: Rowman & Littlefield. [ Links ]

Widdowson, H. G. (2000). Critical practices: On the representation and interpretation of text. In S. Sarangi, S. and M. Coulthard. (Eds.), Discourse and social life (pp. 59-770. Harlow, UK: Longman. [ Links ]

Wodak, R., & Meyer, M. (2009). Methods of Critical Discourse analysis (2nd ed.). London, UK: Sage. [ Links ]

Zhang, W. (2012). Fair value accounting as an instrument of neoliberalism in China (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Wollongong, Australia. [ Links ]

Received: 20 August 2018

Accepted: 24 October 2018