Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of Education (University of KwaZulu-Natal)

On-line version ISSN 2520-9868

Print version ISSN 0259-479X

Journal of Education n.72 Durban 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2520-9868/i72a06

A critical arts-based narrative of five educators working in higher education during an era of transformation in South Africa

Marguerite Müller

University of the Free State. mullerm@ufs.ac.za

ABSTRACT

In this paper I explore creative ways to engage critically with educator identity and experience during an era of transformation and decolonisation. I have written it as an illustrated arts-based narrative that revolves around the experiences of five educators working at the University of the Free State between 2014 and 2016. The narrative was created as part of a collaborative research project in which participants shared their experiential knowledge of anti-oppressive practice. In working with these portraits of five South African educators, I explore the connections between educator identity and social justice in the broader South African higher educational landscape as the call for transformation and decolonisation intensifies. The narrative is intended to trouble the identities and experiences of educators as they make their way through this messy terrain in an attempt to learn from uncertainty and crisis.

Keywords: social justice, arts-based research, performative text, educator identity, anti-oppressive education

Sketching the background

In recent years South African universities have come under the spotlight during student protest movements, such as #RhodesMustFall and #FeesMustFall. The fallist movements highlighted an intensifying call for transformation and decolonisation in South African institutions of higher education (Jansen, 2017). The call for transformation is not new; in the post-apartheid context there has been a strong focus on transforming the curriculum to make it more socially just. This focus is underpinned by the 1996 Bill of Rights that promotes equity and protects all citizens against discrimination based on "race, gender, sex, pregnancy, marital status, ethnic or social origin, colour, sexual orientation, age, disability, religion, conscience, belief, culture, language and birth."1 It can thus be argued that all South African educators have a constitutional commitment to teach in anti-oppressive ways and to work towards socially just practices. However, a 2008 ministerial report on transformation in higher education found racism and sexism to be pervasive, not in the institutional policies, but, rather, in the lived experiences of students and staff (Soudien et al., 2008). Their experiences therefore become an important area of investigation in relation to social justice. Furthermore, Jansen (2017) reminds us that "[t]eachers interpret the curriculum to students on the basis of their own experiences, backgrounds, politics, and preferences" (p. 169), so both the identity and experience of South African educators emerge as key factors to consider in relation to curriculum transformation and decolonisation. In this paper I use portraiture to explore the lived experiences of five educators working towards transformation at the University of the Free State. The portraits are used to highlight the complexity and multiplicity of educator identity through a collaborative narrative exploration of social justice in this context. Through a creative engagement with the entanglement of identity, experience, curriculum, and pedagogy, I hope to move away from theoretical discussions on why we need change, to a more action-oriented emphasis on how we need to change. Davies (2010) posits that agency, rather than being the product of individual will, resides in "the conditions of possibility that provoke new thought" (p. 55). Through the visual/textual narratives I hope to create conditions of possibility that provoke new thought as we work towards transformed, socially just, and decolonised educational research and practice.

Setting the stage

As educators currently working in the South African higher education context, as outlined above, we are caught up in the demand for socially just, transformed, and decolonised approaches to education. However, the contextual realities and lived experiences of educators are sometimes left out or lost in discussions that focus on grand narratives of social change, transformation, and decolonisation. Keet, Sattarzadeh, and Munene (2017), point out that we need to move beyond the theoretical knowledge of what social justice and decolonisation mean to more collaborative, active, and creative approaches. Here, I purposefully extend the theoretical research on anti-oppressive education into a narrative that stretches beyond the classroom space into the lives, childhood memories, personal anxieties, spiritual beliefs, and embodied experiences of five educators at the University of the Free State. In other words, it is not simply about how we teach or what we teach but about who we are inside and outside the classroom, and about how our being is entangled with those around us to form multiple and assembled subjectivities (Deleuze & Guattari, 1988).

If we think of identity as fluid and not fixed, it becomes possible for us to engage with anti-oppressive theories that allow us to work towards different ways of being and understanding. Anti-oppressive theories are not prescriptive about how we should be, but, rather, encourage exploration of who we are and how we can become different. This notion is based on the work of Kumashiro (2002) who has argued for an anti-oppressive pedagogy. In this framework oppression is seen as "a situation or dynamic in which certain ways of being (e.g., having certain identities) are privileged in society while others are marginalized." Furthermore, oppression is viewed as intersectional, multiple, and situational. While critical theory is useful for naming oppression and becoming critically conscious, Kumashiro has argued that we "need to make more use of poststructural perspectives in order to address the multiplicity and situatedness of oppression and the complexities of teaching and learning" (p. 25). Through the portraits referred to in this article, I aim to create a collaborative way of engaging with the multiplicity and situated nature of oppression. The participants and I used the visual/textual work to engage with some of our complex, messy, and uncomfortable experiences as educators at the University of the Free State. In this multiplicity, experience is foregrounded not as a form of narcissism or inwardness, but as a way of situating experiences as micro expressions of narratives of change, transformation, social justice, and decolonisation in higher education. hooks (2003) reminds me that "whenever we love justice and stand on the side of justice we refuse simplistic binaries. We refuse to allow either/or thinking to cloud our judgement. We embrace the logic of both/and. We acknowledge the limits of what we know" (p. 10). By using a theory that foregrounds subjectivity as complex, multiple, and assembled, I hope to make a contribution to how transformation, social justice, and decolonisation can be understood as a micro-project that (partially) emerges and unfolds in the lives, experiences, identities, memories, interactions, and becoming of educators working in higher education. By focusing on the becoming of educators though engagement with creative self-reflexive practices I hope to centre the change-of-self as part of the decolonisation process as a way to move beyond fixed and essentialised identities as we explore the entanglements with others and search for new ways of being.

Creating the portraits

In creating these visual/textual portraits I use a multi-method approach with its roots in critical forms of inquiry such as narrative, collaborative, arts-based research. The use of the ontology of multiplicity seems to fit well with a multi-method approach. It is critical, but also aims to move beyond the critical into an affective analysis where meaning is sought in action and interaction, rather than in representation (Zembylas, 2017). The subject is thus viewed through a critical lens so that we can see, as it were, the intersections of various social identities, such as race, sex, gender, class, and sexuality, but she or he is also read as an emerging subjectivity, not fixed, but always in a state of flux and change-becoming. The narrative component is used to sketch the identity as complex and multiple because

in the storied world. . . things do not exist, they occur. Where things meet, occurrences intertwine, as each becomes bound up in the other's story. Each such binding is in a place or a topic. It is in this binding that knowledge is generated. To know someone or something is to know their story, and to be able to join that to one's own. Yet, of course people grow in knowledge not only through direct encounters with others, but also through hearing their stories told. (Ingold, 2011, pp. 160-161)

Using these portraits I engaged in a visually driven process of storying in which the aim was to make the "mundane, taken-for-granted, everyday world visible" and to "seek performative interventions and representations that heighten crucial reflective awareness leading to concrete forms of praxis" (Denzin, 2013, p. 2). The text functions in the storied world and the characters occur and intertwine to generate new knowledge and heighten crucial reflective awareness. The visual/textual portraits are creative expressions rather than factual representations of stories and occurrences. Working in a postmodern paradigm I cannot possibly claim any objective truth, but, rather, I purposefully fictionalise, narrate, and sketch (see Leavy, 2009). In so doing I also rely on visual methods of expression (drawing and collage) that function with the text to create visual/textual portraits. The arts-based approach I followed was useful for creating what Finley (2011) has referred to as "new visions" that might lead to concrete forms of praxis.

From within the liminal openings that are created by the performance/practice of arts-based inquiry, ordinary people, researchers as participants and as audiences can imagine new visions of dignity, care, democracy and other decolonizing ways of being in the world. Once it has been imagined, it can be acted upon, or performed. (p. 443)

Through these visual/textual portraits I hope to create academic work that is "socially responsible, locally useful, engaged in public criticism, and resistant to neoconservative discourses that threaten social justice and close down efforts toward a performative research ethics that facilitates critical race, indigenous, queer, feminist and border studies" (Finley, 2011, p. 437). The portraits were created as part of my PhD research project for which I invited participants, working as educators at the University of the Free State, to share some of their personal narratives and experiences of working and being in this space. The research project received ethical clearance from the University of the Free State and the participants chose their own pseudonyms. I hoped that a collaborative method of creating and sharing narratives would help me to understand some of the complexities that I felt in my own attempts to work towards anti-oppressive practice.

At the start of the project, I asked each of the participants to create a character and make a visual/textual portrait of their character as a fictional self. The participants were supplied with some basic art materials which they could use (or not), but how they created or presented the character visual/textual portraits was entirely up to them. The only guideline was that the character they created had to be an educator working in higher education and had to be inspired by their own experiences. In the second round of individual conversations (which were recorded), we discussed the participants' artwork and they each introduced the character-self into the emerging story. Using the recordings of these conversations I produced written sketches of each character, which I then shared with the participants via email. Following this I arranged another round of individual conversations (also recorded) during which we reflected on the portraits and the way in which they could help us engage with some questions that stem from Kumashiro's (2002) theory of anti-oppressive education. During the second interview, the participants were also asked to share a photograph to help me build their visual character portrait. After these conversations, I re-created the portrait collages by incorporating the initial artwork alongside the newly emerging stories, and the photographs. The portraits I created were then shared with the participants. Finally, I invited the participants to help me interpret, read, and facilitate meanings that emerged from this layered process.

Art and narrative help us communicate that which is unquantifiable (often deemed unscientific), but which is at the foundation of our human experience. It offers "knowledge as a process, a temporary state, [which] is scary to many" (Eisner, 1997, p. 7). The implication is that, as educators, we cannot learn or be told how to work towards anti-oppressive practice but have to build such knowledge through our experiences, and the process of creative engagement with those experiences. This is important in the context of social justice, transformation, and decolonisation since changing the curriculum or policies will not be effective if the teachers who implement curriculum and pedagogy are left out of the conversation. Through an engagement with creative self-reflexive practices I hope to focus on the change-of-self as part of the process of becoming. Creative engagement with our experiences and memories becomes a way to move beyond fixed and essentialised identities as we explore our entanglements with others and search for new ways of being.

Five portraits of educators at UFS

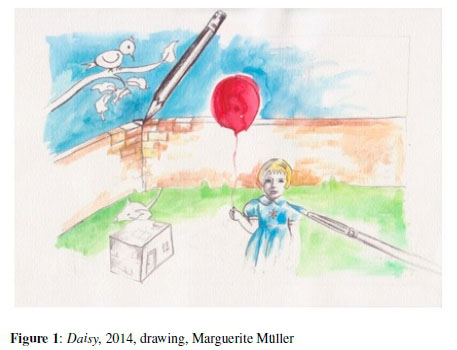

Daisy

She is playing with a red balloon in a lush green suburban garden. The air smells of jasmine, sunshine, watermelon, birthday cake, washing powder, ironed clothes, mowed lawns . . . She goes to a good Afrikaans school and gets a good education. She is part of a close-knit community in which similar views on religion, politics, history, and a shared language serve as the glue that binds them as white Afrikaners. The only people of colour she knows work as cleaners or gardeners. She listens to them speak languages she cannot understand. Although they are grown-ups she does not call them oom or tannie,2 as she would call white grown-ups, but addresses them by their names. She knows that they have children, because unused toys or outgrown clothes are often sent home with them, but she never sees their families or their homes. They seem to exist only in her world, with their own world somewhere beyond hers, out of her sight. She goes to high school in 1996 and for the first time she sits in classrooms with people who had been classified as coloured3 under apartheid. Her coloured classmates do not live in the white neighbourhoods, but in the township that was designated for coloured people under apartheid legislation, and which is far away from school. These classmates arrive in buses in the morning and leave in buses in the afternoon. In class she gets to converse with some of the coloured students and exchange ideas on topics from music to religion. When the bell has rung for break the coloured learners sit in one group and she sits with the other white learners. The teachers are all white and the cleaners are all black. The principal is male and the secretaries are female.

Daisy is made to sit silently through countless ceremonies to celebrate the school's mediocre rugby team and watch boys with inflated muscles parade across the stage while she applauds in what is thought of as a civilised manner. No whistling or shouting! On early winter mornings she is secretly envious of the boys who get to wear pants to school when she must wear short skirts (five fingers above the knee) with stockings. Even if pants were allowed she wouldn't wear them anyway; that would make her seem unfeminine and therefore unpopular. She would love to take woodwork and metalwork as a subject because of her interest in sculpting, but she doesn't dare do such a thing. One girl in the school did have the guts to take the boy subject once and everyone talked about it saying she must be a lesbian...

At this point in the narrative I have to point out that Daisy's memories as recounted above are probably not very different from the memories of many other white middle-class South African females who grew up in the 1980s. Her memories are a part of me, of my memory and childhood, but it is also part of something more collective. I see it as a micro-expression of a larger social narrative that weaves in and out of my identity. What does remembering make possible? When I stand in front of diverse classes and teach social-justice lessons I have to allow myself to be there, present and fully present, with all the history, memory, and experience that comes with being me. But I do not exist in isolation; I belong to a bigger assemblage into which my experiences are woven. Thus, I leave Daisy's partial and incomplete story here on this page and I go on to speak to Alice. "Tell me about what it was like growing up and going to school?" I ask her.

Alice

I remember when I was in Grade 7, I had such curly hair! I didn't look typical . . . like a typical Indian you know? And I had this kind of accent that was not Indian, and I felt different and I was made to feel different, because I came from this different kind of school . . . because before that I had been in a Catholic school; it was a private school so we were all mixed-white, black, coloured, and Indian. I remember it as a strict and rigid kind of schooling with rote learning and questioning, and obedience, discipline, and respect for elders. There was this distance between the teachers and us and the majority of the teachers were Catholic nuns, so anyway there was this otherworldly kind of [discipline], you know, so they always threatened you with Jesus and God when you did anything wrong, and they were a bit abusive, yes they were physically abusive . . . they used to give us [what we called] German knocks, like knuckles on the forehead . . . but I learnt discipline there, and to work hard . . . and I learnt to be independent . . . But anyway, then that school closed down and on my first day at this new school, this Indian school, in the afternoon the principal wanted to see me and she asked, "What are you? What is your race?" and I was not sure . . . so she said, "Are you coloured?" And I was like so uncertain about what I was. And so she called my mother that day and she asked for my birth certificate. On the birth certificate it said Indian and I, uhm, you know then she told my mother, that you know she said she's coloured. Uhm, but schooling ja, was . . . after a while . . . you know, apartheid was so deeply entrenched that we never really questioned its effects on us.

So like I feel all this sense of uncertainty and I'm like looking at myself and I'm wondering, am I doing the right thing, even in my teaching? . . . you know like . . . even you know like, like I constantly feel like I'm in this space where I'm like asking . . . if this works. Why didn't it work, or did it work? So there is this constant state of flux that I'm in. So like I'm constantly feeling like I'm . . . I don't know . . . like I'm not doing the right thing?

Celine

I grew up in the dusty streets, in that small little house you know, it was just, myself, my mother, and my sister, just three ladies in the house, so that was . . . I think it had pros and cons, for me as a child you know, because uh, in my house we never used to wear towels when you come out of the bath . . . we didn't even have a bathtub, we used those small basins, plastic basins, you know. I remember just bits and pieces of my parents staying together, and [they were] not good memories where my father was abus . . . physically abusive, also cheating and then just that's when my mother decided to leave, and you know when she left we've never seen a male in our house, you know. That also affected how I take my decisions now-it's ok to have kids; it's also ok not to have a husband. I think that's just how it shaped me as a person. I think one of the other things which she has also said . . . not out in so many words, but she would articulate that you become your own person; you don't need to . . . you don't need a man to get to where you want to go. So that's how I started becoming this Miss Independent. And you know coming to think of it back then, if you didn't have father, you were stereotyped in some way . . . like they would want to know, why don't you have a father . . . and I just felt like they would look at you differently, even though some of the teachers were being abused themselves. We would see one coming with a black eye on a Monday, you understand? And for me that would say . . . because I remember my own mother being abused and she walked out of the marriage. If a marriage does not work just walk out . . .

But the biggest lesson I learnt was [that] money will not even get you where you want to go, your brains will, you know, so it sort of motivated me to see all those students that were from the very well-off backgrounds, repeating the same modules with me and some of them I was even passing more than they were, you know, and I just set my deadline that you know in three years' time I'm getting my degree, which I worked very hard for, you know. There [were] a lot of sleepless nights, and what motivated me was always seeing my mother when I sent the results home that I did well, the pride that she would have and my sister as well.

Now when I see this student sitting in front of me in my office, I see myself at that time and you know, knowing very well that this is a once-in-a-life-time-opportunity, that's why I preach it to them that it's your one chance and you cannot afford to mess it up.

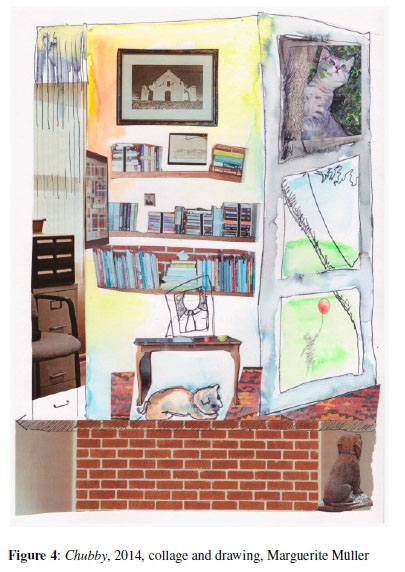

Chubby

We moved around quite a lot; I think I went to seven different schools. My father worked for the municipality, but he was always looking for a better life for us, and better work often meant moving . . . I remember as a small child of around five, I wondered why there were separate entrances at the shop and the post office. We went through one entrance and black people through another. I was small, but I remember wondering about that. My father worked on the roads and I think it was a rough life . . . a guy didn't do his work they would punish him . . . so I think there was sort of racism in the background of my youth, but I think in our home it was different. Racism wasn't an issue there. But I remember wondering about the separate entrances . . . I never became an activist or anything; I suppose we were comfortable in our own lives. I grew up in a very protected environment; I had a happy childhood.

But you know I cannot be perfect; I make so many mistakes, we all do . . . On Friday there was a group of students who had to write an exam and when they got to the venue the question paper was only in English, and some of the Afrikaans students walked out . . . and that is their right, but when the secretary phoned them to make arrangements for another opportunity, I asked her to request that they do not make a language political issue out of this . . . it was just an administrative mistake-one of the lecturers made an error when getting the paper copied, that's all . . . I think it's all about awareness . . . There are things I don't know about and I might be stepping on people's toes, but then I do I think there should be a space to talk about those things. We are all on a journey in this new South Africa . . . I make mistakes, or say naïve things, but don't run to the Rector . . . come talk to me and make me aware.

Uhm, one has so many things you want to do perfectly, but you cannot do everything perfectly. You really . . . One really makes mistakes and sometimes you say something and feel yourself go cold . . . I am a calm person, uhm, I do not lose my head easily; in a crisis I can actually keep my head above water and rise above the challenge. So losing my head is not part of who I am.

Mick

I am busy with a juggling act. I am trying to make the world better, but I have to juggle all these things: relationships, friendships, work, studies . . . trying to make people happy. . . where students are comfortable, everything is normal and they know everything and nobody is rocking the boat and I think when we started to talk about the issue of race and we didn't move away from it, it was like now I made them to be in that space, that dangerous space where there is nothing and I actually pushed them to a foreign place . . . my work being about moving the students, to that, to the other side, but actually a lot of this work is about moving myself onto that cliff, so it's like I'm moving with my students. I think it is both ways, the cliff, and not just students but constantly also me, of always having to be on that side all the time, so it's like going to another planet and someone just drops you off there.

I always want the students to make that leap to the other side of the cliff, to the foreign space. But I think in this picture it represents me also, constantly having to make that leap, because this for me, it was also a foreign space where I was othered, and I had to force myself to stay in that space in order for my own learning to occur . . . Emphasis on my students, my work being about moving the students to that other side, but actually a lot of this work is about moving myself over that cliff, so it's like I'm moving with my students.

An affective reading

As explained above, the portraits were created in response to narrative interviews and were collaboratively discussed and interpreted by me, the researcher, and the participants. The analysis or interpretation happened throughout, as we sketched, talked, and created. It should therefore be seen as a continual and collaborative process, as well as an affective one. Our responses were often more about how the portraits and narratives made us feel and react, than about what they meant. I consciously distance myself from the terms data and analysis because of their associations with a positivist and empirical paradigm. By contrast, the arts-based approach is used to help us move beyond the theoretical knowledge of what social justice and decolonisation mean to more collaborative, active, and affective approaches. St. Pierre (2013) criticises the logical positivist empirical unconsciousness that also heavily influences qualitative studies for what counts as scientifically based or evidence-based research in the social sciences. "Once the empirical is transformed into real, visible words on a page-brute, sense data-these researchers strip the words from context, manipulate them, order them in binaries and hierarchies and categories, label some words with other words (code data), and even count the words. Words become quasi-numbers" (p. 224). St Pierre has advocated for a post-qualitative kind of research in which the aim is to explore different research practices. This kind of creative and affective collaborative interpretation is a move away from what traditionally counts as empirical data and analysis to interrogate the traditional power hierarchies that exist in research. A move towards decolonised ways of doing research is also a move towards research practices that do not rely on binaries, hierarchies, categories, and labels to make sense of experiences.

For example, in Daisy's story it is easy to list all the social and essentialised categories that constitute her memories of childhood-categories of race, sex, gender, class, and sexuality. Her story is one that is located in the world of binaries, but her story is not one that can exist in isolation. I know that because her story is also mine. When I commenced research on anti-oppressive education I realised that before I could move forward I had to go back, as far back as childhood, in order to make sense of my present self. As I started this process I realised the limits of my experiences and it became evident that I had to go beyond my story, to look for the stories of those around me. Listening to the participants tell stories that are different from mine became a valuable way of reaching beyond my story into other stories. I think that this process of understanding and venturing beyond the known is an important part of recognising the self as entangled with others. The self is thus seen not essentialised, but, rather, as multiple and assembled.

Alice also speaks of how the category of race emerged so strongly during her childhood. She makes the statement, "You know apartheid was so deeply entrenched that we never really questioned its effects on us." By bringing her past experience into the present she made me aware that we cannot move towards anti-oppressive education if we do not reflect on the effects of the past. Most of us, as South African educators, come from a past in which we were affected by apartheid significantly in ways that have shaped who we are now, and we need to look at the ways in which we stay stuck, but also recognise how those experiences can help us to become different through this crucial reflective awareness. Creating the portraits is a way to interpret and re-tell stories that make the "mundane, taken-for-granted, everyday world visible" and to "seek performative interventions and representations that heighten crucial reflective awareness leading to concrete forms of praxis" (Denzin, 2013, p. 2). Furthermore, the portraits function to make the educator's experiences in relation to social justice visible in local and contextual realities. After reading her portrait Celine responded,

When I read the story it just connected very well and I was actually surprised-wow! MY story is part of this! And you know when you talk you just don't realise how somebody is listening to what you are saying. And to be actually . . . because you know we are so used to reading other people's stories, but when you are part of the story you just . . . ok, ok that's interesting.

Celine expressed her surprise at seeing that her story "is part of this." So often we fail to recognise ourselves in academic discourses on social justice that are written in contexts far removed from where we are. Thus, the process of collaborative narrative creation makes it possible to situate ourselves in the research story where we understand oppression to be "the citing of harmful discourses and the repetition of harmful histories" (Kumashiro, 2000, p. 40). The visual/textual portraits highlight the fact that anti-oppressive education is not simply about how we teach or what we teach, but about who we are in terms of being, becoming, and belonging. If we bring our bodies, emotions, and histories into the research space we move towards a more vulnerable and honest engagement with issues of social justice. For example, Mick mentioned how he was fuelled by a desire to make society a better place and to heal, and also spoke about how this type of work could be emotionally draining.

And my work is social justice; my work is to work towards a society which is equal, fair and . . . uhm, so transformation is part of that huge agenda. So the clown makes people happy. I'm trying to make society a place where people . . . there's equality and there's less pain and there's less hurt and there's less discrimination. But I think possibly, ja . . . so it is a mask . . . Because in this process of trying to make people happy, it's heavily taxing, taxing on me the individual who is doing this. There is a lot of uhm [pause] hurt and um [pause] it's emotionally draining . . .

Later, he talks about a specific episode in the classroom.

So I walked out of that classroom feeling extremely confused, frustrated and I was questioning: Did I do hurt more than I tried to do anything about healing in that classroom?

According to Zembylas, Charalambous, and Charalambous (2012) the value of discomforting emotions is that these might lead educators to examine their constructed self-images critically, as well as how they have learnt to perceive others. When we grapple with issues of oppression we often feel disorientated, like aliens in a foreign place, because we are different, and because we have allowed ourselves to lose control partially and to move away from doing things correctly and perfectly to asking, "Am I doing the right thing? What just happened here? Am I causing more hurt than healing?" This means we will need to embrace uncertainty, imperfection, confusion, and discomfort. We also need to acknowledge our limitations in terms of anti-oppressive and social justice work. Kumashiro's (2000) anti-oppression theory oscillates between critical theory and post-structuralism because he uses critical theory to explore unequal power relationships and oppression while at the same time uses a post-structuralist approach to highlight the fluidity and situated nature of identity. In doing so, he highlights the necessity to understand always that all theoretical approaches are limited and incomplete. It is necessary to acknowledge the limits of what we know and not attempt to sell grand narratives and complete packages of what social justice might look like in different contexts to various people. Partiality, as expressed in the visual/textual portraits, is purposeful and necessary.

Chubby makes the connection between theological work and education in that they both involve caring. Yet he backgrounds his own feelings of vulnerability and emotional involvement by saying that he is someone who does not "lose [his] head" easily in a crisis and that he can "handle" difficult situations. When I commenced my postgraduate studies I encountered a similar approach to what researchers are expected to do. They are supposed to stay rational and not allow their emotions to cloud their vision. It was only as an artist that I felt encouraged to be in touch continually with my emotions and to bring these into my work. Using arts-based methodologies is useful for bridging the rational/emotional binary. In order to move beyond the binaries of self/other we need to engage other binaries as well. A decolonised form of research needs to probe binaries that have kept categories and classifications in place. For example, the distinction between theory and methodology could also come under scrutiny in research practices in which we seek to engage with the entanglement and embodiment of theoretical perspectives. Through our artworks, memories, and narratives we begin to embody the theory, but also trouble it, which then brings about an understanding of social justice as both a process and a goal (Adams, Blumenfeld, Castaneda, Hackman, & Peters, 2000). Francis and Hemson (2007) found that teacher education in social justice should be seen "less as a triumphant charge from oppression to liberation, and more as a scaffolding of a difficult entry into a new and still imperfect discourse" (p. 100). In this article I argue that the portraits function as an entry point into an imperfect discourse in which educators emerge as complex individuals in an uncertain and messy space.

Conclusion

This article is my exploration of creative ways to engage critically with educator identity and experience during an era of transformation and decolonisation in higher education. The aim of this exploration is to find new ways to think about who educators are, and about how the complexity, multiplicity, and assembled expression of identities can help us think differently about the context of higher education. In this way educator identity emerges as an integral part of our thinking about anti-oppressive education, social justice, and decolonisation. In a South African context the goals of anti-oppressive education and social justice overlap and are woven into the decolonisation and transformation project. In an attempt to move beyond the theoretical knowledge of the need for change, the portraits are examples of how, through our practices, we can work with self-reflexive expressions to engage in micro transformation. The use of visual/textual portraits shows how educators can explore the self as a critical site of micro transformation.

Furthermore, the visual/textual portraits of five educators at the University of the Free State are used to foreground the emotional and experiential knowledge that underscores work on transformation and decolonisation. The connections between educator identity and transformation are made visible within a messy, uncertain, and volatile space since they highlight the disconnect between what we want, who we want to be, and what really happens inside and outside our classrooms. At the same time, they serve to turn our lens, as researchers, away from grand narratives of transformation and decolonisation and focus on the micro narratives that play out in the everyday lives, memories, and experiences of educators in higher education.

As educators working towards social justice in the higher education space we need constantly to relearn and unlearn prior knowledge. This is an ongoing process in which we trouble existing knowledge and so-called normal ways of being. We need continually to look beyond the limits of what we know and who we are, in order to become different. In addition, we need to move beyond binary ways of thinking about ourselves, the world and our research practices. In the creation of the visual/textual portraits of educators, I do not attempt to paint a complete or comprehensive picture of educators working in the higher education space in South Africa because our stories are always partial. I hope to foreground an affective engagement with new possibilities, rather than a descriptive or representational analysis of what they might mean.

This account of a creative exploration of the action and interaction of a group of educators working in the higher education landscape in South Africa foregrounds the complexities and contradictions in our lived experiences as we make our way through an uncertain and messy terrain to trouble and unlearn oppressive knowledge as we look for new ways of being, becoming, and belonging.

References

Adams, M., Blumenfeld, W. J., Castaneda, C., Hackman, H. W., & Peters, M. L. (Eds.). (2000). Readings for diversity and social justice (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Davies, B. (2010). The struggle between the individualised subject of phenomenology and the multiplicities of the poststructuralist: The problem of agency. Reconceptualizing Educational Research Methodology, 1(1), 54-68. [ Links ]

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1988). A thousand plateaus. London, UK: Athlone. [ Links ]

Denzin, N. K. (2013). The death of data? Cultural Studies - Critical Methodologies, XX(X), 1-4. https://doi.org/10.117/1532708613487882 [ Links ]

Eisner, E. W. (1997). The promise and perils of alternative forms of data representation. Educational Researcher, 26(6), 4-10. [ Links ]

Finley, S. (2011). Critical arts-based inquiry. In Norman K Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (pp. 435-450). Thousand Oakes, CA: SAGE. [ Links ]

Francis, D., & Hemson, C. (2007). Rainbow's end: Consciousness and enactment in social justice education. Perspectives in Education, 25(1), 99-109. [ Links ]

hooks, b. (2003). Teaching community: A pedagogy of hope. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Ingold, T. (2011). Being alive: Essays on movement, knowledge and description. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Jansen, J. 2017. Sense and non-sense in the decolonization of curriculum. In J. Jansen, As by fire: The end of the South African university (pp. 153-171). Cape Town, RSA: Tafelberg. [ Links ]

Keet, A., Sattarzadeh, S. D., & Munene, A. (2017). Higher education and knowledge otherwise. Education as Change, 21(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1947-9417/2017/2741 [ Links ]

Kumashiro, K. K. (2000). Toward a theory of anti-oppressive education. Review of Educational Research, 70(1), 25-53. [ Links ]

Kumashiro, K. (2002). Troubling education: Queer activism and anti-oppressive pedagogy. New York, NY: RoutledgeFalmer. [ Links ]

Leavy, P. (2009). Method meets art: Arts-Based research practice. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Soudien, C., Micheals, W., Mthembi-Mahanyele, S., Nkomo, M., Nyanda, G., Nyoka, N., & Villa-Vicencio, C. (2008). Report of the Ministerial Commitee on transformation and social cohesion and the elimination of discrimination in public higher education institutions. Pretoria, RSA: Department of Education. [ Links ]

St. Pierre, E. (2013). The appearance of data. Cultural Studies - Critical Methodologies, 13(4), 223-227. https://doi.org/10.117/1532708613487862 [ Links ]

Zembylas, M. (2017). The contribution of non-representational theories in education: Some affective, ethical and political implications. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 36(4), 393-407. [ Links ]

Zembylas, M., Charalambous, P., & Charalambous, C. (2012). Manifestations of Greek-Cypriot teachers' discomfort toward a peace education initiative: Engaging with discomfort pedagogically. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28, 1071-1082. [ Links ]

Received: 12 May 2018

Accepted: 20 September 2018

1 Section 9 (3) of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996. Available from: http://www.justice.gov.za/legislation/constitution/SAConstitution-web-eng.pdf

2 The honorary terms oom [uncle] and tannie [aunt] are used as a respectful way to address adults in traditional Afrikaans speaking communities in which children would rarely address an adult by name.

3 Under apartheid legislation all South Africans were classified into a racially demarcated group. The groups were white, coloured, black, and Indian. Many South Africans still use these racially demarcated categories to refer to their racial identity.