Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of Education (University of KwaZulu-Natal)

On-line version ISSN 2520-9868

Print version ISSN 0259-479X

Journal of Education n.72 Durban 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2520-9868/i72a03

Voices of Grade Four teachers in response to Mazibuye Izilimi Zomdabu! (Bring Back African Languages!): A decolonising approach

Patrick Mweli

University of KwaZulu-Natal, School of Education. mwelip@ukzn.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The language of learning and teaching (LoLT) poses a threat to the quality of teaching and learning of most learners who speak African languages in Africa and particularly in South Africa. In this study, I explore language attitudes and the lived experiences of 400 Grade Four teachers in Pinetown and UMgungundlovu districts teaching African learners using English as LoLT. The study challenges Anglonormative language ideologies (Mckinney, Carrim, Layton, & Marshall, 2015) and the coloniality of dominant discourses about LoLT in South Africa. Calling on the voices of the teachers, I argue for the use of African languages to teach African learners as a powerful measure to regain African identity and to delink education from Eurocentric knowledge and cultures. I compared results from quantitative and qualitative data to arrive at the overall finding that most Grade Four teacher participants prefer the use of African languages to teach African learners and that these teachers are experiencing difficulty in using English as LoLT to teach most of them. Drawing from teachers' responses, I conclude that the use of African languages in education connects learners' worldviews and ways of knowing to the curriculum and provides access to knowledge.

Keywords: language of learning and teaching (LoLT), African languages, African worldview, African ways of knowing, culture, colonial LoLT, Epistemic Decoloniality LoLT (EDLoLT)

Introduction

Language and literature were taking us further from ourselves, from our world to the other world. (Ngifgf Wa Thiong'o, 1986, p. 12)

Linguistic mismatch between the language of education and the language known and understood by learners has been a matter of global concern since the mid-twentieth century (Mohanty, 2012; Wigglesworth, Simpson, & Loakes, 2011). Language in education has been a controversial issue in South Africa in spite of the constitutional right that all children should receive education in a language of their choice and that all eleven official languages should enjoy equal status. The Language in Education Policy, drafted along language rights as enshrined in the Constitution, aimed at ensuring the continued use of mother tongue as LoLT and enabling learners to gain access to additional languages through additive bi/multilingualism. However, research (Madiba & Mabiletja, 2008; Makoni & Pennycook, 2012; Pluddemann, 2013; Prinsloo, 2007) indicates a disjuncture between the additive bi/multilingual and its implementation in classroom discourse. For example, Banda (2000) has pointed out that the chances of success of the South African Language in Education Policy are very slim if African languages are not made part of classroom discourse.

The use of African languages in education could ensure the cultural identity of learners and provide access to knowledge through the alignment between LoLT, worldviews, and ways of knowing. Most African cultures that learners bring into the classroom are not used to support quality learning and teaching. Therefore, in a situation in which English is privileged over African languages as LoLT, it could be argued that the use of English, which is embedded in Anglo-centric culture, denies epistemological access to knowledge to the majority of learners who speak African languages.

I recognise the argument made by most researchers that language ideologies, language theorisation, and historical context have played a crucial role in shaping the character of languages (Banda, 2000; Makalela, 2015; Makoni & Pennycook, 2005; Mckinney et al., 2015; Spear, 2003). This literature also indicates the role played by missionaries in the development of African languages through the introduction of written languages using Latin script (alphabets). However, my argument in this article centres on the idea that there is a necessity for scholars of linguistics and psycholinguists as well as educationalists to move beyond the current language theorisation and ideologies and recognise the role of cultures in shaping human cognition through worldviews and languages as the carriers of culture. Ngu~gi~ (1986) regarded language as "both the means of communication and a carrier of culture" (p.13).1

South Africa as an Anglophone country inherited English as LoLT as did other Anglophone and Francophone African countries that inherited the coloniser's language during dependence and continued to use it after independence. The hegemony of the English and French languages in Africa has been ignored by the international community for a long time (Brock-Utne & Mercer, 2014). Researchers in this regard (Alexander, 2009; Alidou et al., 2006; Cabansag, 2016; Skutnabb-Kangas, 2017) have argued against the use of English and French as dominant language in African education systems since this has resulted in African languages being shifted to the background; this is likely to affect the delivery of quality education for all speakers of African languages.

Quality teaching and learning is understood in terms of the assumption that learning is a social activity and both learners and teachers construct knowledge through active participation. In other words, quality teaching refers to effective mediation during which the teacher as the knowledgeable other interacts with the learner in the process of knowledge and skills acquisition using language that is understandable to the learner as the tool of communication. Researchers have indicated the inherent difficulty of using English as LoLT to teach African learners (Hugo & Lenyai, 2013; Sibanda & Baxen, 2016) with low English language proficiency. To illustrate, in the study by Kirui, Osman, and Naisujaki (2017) conducted with teachers in Arusha district, Tanzania, in community secondary schools, it was found that that both teachers and learners struggled to express themselves in English so it is likely that no effective mediated teaching process occurred. Moreover, "teachers agree[d] that they face[d] challenges in the use of English as the language of instruction" (Kirui et al., 2017, p. 113). This complicated the learning and teaching process and resulted in low learner academic achievement. Cummins, Mirza, and Stille (2012) concurred with this in stating that learner and teacher proficiency in the medium of instruction largely determines academic success. In South Africa, a similar situation exists in the education system since the majority of African learners receive education through the medium of English in contravention of the ideal of additive bi/multilingualism that is promoted by the South African Language in Education Policy (Department of Education, 1997). In this article, I challenge the hegemony of the use of the English language in education as one of the remnants of coloniality that promotes the imperialistic agenda by instilling Eurocentric worldviews and cultures in the minds of African learners. The argument is framed within the understanding that "coloniality is the fundamental problem of the modern age" (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2013, p. 13).

It is crucial to note that language and cognition are intertwined, and language contains knowledge codes that are crucial to learning (Vandeyar & Killen, 2006). Most importantly, languages are cultural symbols that exist in the human mind, represent abstract ideas or concepts, and shared cultural knowledge in a particular society. These symbols are meaningless outside the culture in which members of the societies who use them attach shared meanings to them (Mweli, 2018). In this regard, African languages contain African worldviews and ways of knowing that are in line with African cultures. Using African languages to educate the African child is likely to have more benefits than using English. For example, Adesemowo (2017) has pointed out that there are benefits in using the language that is familiar to learners because learners are able to relate to concepts in their own language and culture. UNESCO (2014, p. 283) concurred by noting that if we are "to ensure that children from ethnic and linguistic minorities acquire strong foundation skills, schools need to teach the curriculum in a language that children understand" (p. 283). The bilingual approach needs further exploration to ensure the alignment between the worldviews and the ways of knowing of learners and teachers that is made possible by the use of mother tongue languages that incorporate shared African cultures. It is likely that under these circumstances, the teachers will teach better and learners will understand more.

Problem Statement

The performance of the South African Grade Four children in the international literacy test, The Progress in International Reading and Literacy Study (PIRLS), shocked most stakeholders in the South African education system. The PIRLS 2016 Report revealed that 78% of Grade Four children could not read for meaning in any language. This means that they cannot retrieve basic information from a text to answer simple questions. Furthermore, the Annual National Assessment (ANA) report of 2013 and 2014 (Department of Basic Education, 2013, 2014) indicated that most Grade Four learners have difficulty in interpreting meaning and analysing information from a text. The greatest difficulty was in responding to questions on writing and presenting as well as on the language structure and conventions. Most learners at this level could not provide valid reasons for their answers and demonstrated limited vocabulary in their first additional language.

These results suggest that there is a severe problem with language and with pedagogic content knowledge in the South African education system. This problem deepens with African learners who use the second language of English as LoLT. It is apparent that most African learners at Grade Four level have not reached the required level of English proficiency. For example, Sibanda (2017, p. 4) has pointed out that "there is no basis to suggest that African language-speaking learners would have developed Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills (BICS) in English by the time they get to Grade Four" (p. 4). In addition to the problem, as mentioned earlier, teaching African learners through a language that is unfamiliar to them could result in their access to knowledge being denied, and could lead to low academic achievement, minimal learner-participation in classroom activities, and memorization of information and concepts that would result in shallow learning and misunderstanding of the concepts.

Conceptual Framing: Decoloniality

I conceptualised what I call Epistemic Decolonial LoLT (EDLoLT) in this study within the definition of decoloniality provided by Ndlovu-Gatsheni (2015) that "decoloniality centres around the notion of remaking the world to emancipate the enslaved, exploited and colonised people to regain their dignity as human beings, land, their knowledge systems and power" (p. 23). The use of languages inherited from the colonisers is regarded as part of the propagation of the coloniality of knowledge in which the imperialist agendas are spread with the aim of promoting Eurocentric modernity in the African continent (Ngugi , 1986). Hence, EDLoLT in schools should strive towards emancipating the exploited and colonised people by providing access to knowledge that will enable them to regain their dignity, land and power. After all, as Ngugi has said, "English was the official vehicle and magic formula to colonial elitedom" (p. 12).

Grounding my thinking in the above, I position my argument in terms EDLoLT. By this, I mean a language of learning and teaching that delves into the epistemologies of the oppressed, colonised people, and captures the essence, depth, and goodness of African indigenous knowledges. EDLoLT should affirm the dignity of African people and recognise their identities, knowledge systems, and cultures (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2013); this would allow for multi-African languages to be used in education to teach the African child. Put differently, EDLoLT is rooted in the idea that African education systems need to use multi-African languages that do not "exercise racial and colonial power/knowledge" (Adams & Estrda-Villalta, 2017, p. 37) to suppress the exploited and enslaved African learners but should, instead, sustain the African identity and dignity that was obliterated by colonialism.

Decoloniality is a reaction against coloniality in an attempt to redefine and find a new world order (Grosfoguel, 2011). The term coloniality was first coined by Quijano (2000) and was further elaborated on in the work of Mignolo (2011) who referred to coloniality as the name for the dark side of modernity. This must be unmasked and shown to be rooted in the logic that enforces control, domination, and exploitation disguised in the name of modernization and said to be good for everyone. It is important to note that the forms of coloniality persist because of "knowledge formation and [the] modern ways of being that the colonial powers imposed on the world as a hegemonic standard" (Adams & Estrda-Villalta, 2017, p. 39). However, EDLoLT in the African context would affirm indigenous epistemologies and worldviews that are aligned with African cultures because, as already noted, languages are tied up with cultural values and worldviews (Batibo, 2015). In this regard, African education systems should sever themselves from Eurocentric knowledge, languages, and cultures to acknowledge education that affirms African identity (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2013) and indigenous knowledge systems.

English as LoLT to teach African learners is one of the elements of colonial knowledge-the "constructions of reality that both reflect and reproduce forms of racial domination and inequality" (Adams & Estrda-Villalta, 2017, p. 37) and ways of knowing that do not align with the African worldviews that most African learners bring into classrooms. Therefore, EDLoLT can be seen to be rooted in the idea that African languages should be regarded as enabling tools for quality teaching and for the learning of African learners in a way that aligns their worldviews and ways of knowing (Marrow, 1994) with the curriculum content. Haraway (1988) has concurred with this in stating that "our knowledges are always situated" (p. 8) in that they are embedded in a culture and transmitted through a language. Collins (1990) has referred to Haraway's statement as "Afro-centric epistemology" (p. 508). This could promote the use of indigenous knowledge systems and enable most African learners to approach the learning of new concepts from the position of strength provided by African languages as LoLT in education.

Theoretical framing: A sociocultural approach

According to sociocultural theory, language is central to learning (Wertsch, 2007). Learning is a social process through which human intelligence develops (Wertsch, 1985). Through language, the learner acquires knowledge and skills that originate in society and culture (Lantolf & Thorne, 2000). Knowledge and skills, according to the sociocultural approach, are mediated through interactions between the learners and their social environment or culture. Learning becomes a social collaborative activity (Swain, Kinnear, & Steinman, 2010) given the interaction occurring between the capable others (teachers, peers, and parents) and the learner in the educational social context.

Language is central to the learning process; it is understood to be one of the cultural artefacts used for communication during interaction where knowledgeable others give instruction and learners respond to instructions in learning activities. These instructions play a vital role in facilitating the smooth and effective acquisition of skills and knowledge. The learner actively engages with verbal instructions through communication and task performance. For example, teaching a child how to ride a bicycle follows a number of sequenced procedures. First, the capable other could model how to ride and verbally explain the procedure. Then the learner performs the modelled behaviour and follows instructions to acquire the skill necessary to riding a bicycle. During this process, the capable other scaffolds the skills and knowledge by allowing the learner to perform tasks that are manageable at the time until the acquisition of more complex skills and knowledge is achieved. A similar situation occurs during the performance of learning tasks in the classroom. Drawing on sociocultural theory, we see the learning process following an outward-in approach; knowledge that was an external entity in the learner's environment becomes an internal entity residing in the mind of the learner. Learning first occurs between people and then in the individual (Liang, 2013). We can see that language plays a crucial role in the acquisition of skills and knowledge during the learning process.

Methods

Following Creswell and Plano Clark (2010), my study consists of two parts, the survey and the focus group discussions used in a parallel convergent mixed method approach. I have compared the findings from both sections to reach the overall findings of the study. Part 1 (quantitative) investigated the attitudes that Grade Four teachers have towards English as LoLT. Random sampling was used to select the survey respondents. The sample consisted of 400 Grade Four teachers from semi-rural and urban schools. Following Cohen, Manion, and Morrison (2011), the qualitative second section interrogated the lived teaching experiences of Grade Four teachers in using English as LoLT to teach African learners. Twenty Grade Four teachers participated in five focus group discussions. All Grade Four teachers teaching different subjects were eligible to participate in the study since the main purpose was to investigate their lived experiences regarding the use of English as LoLT to teach the African learners. I used purposive sampling to select the participants for the focus group discussion. A convergence parallel mixed method research design was used to interrogate the research phenomenon. Quantitative data (survey) was analyzed using inferential and descriptive data analyses. Qualitative data (focus group interviews) was analyzed through thematic data analysis.

Ethical considerations to ensure the safety, privacy, and confidentiality of the participants and to secure permissions from gatekeepers were taken into account. After I had applied for ethical clearance from the University and had received permission from the Department of Basic Education and the school principals to use the research sites, I visited each and held a meeting with potential participants. I assured them of the confidentiality of the information obtained, their anonymity, and their right to withdraw. I also had the participants sign a consent form.

Findings

African language preference as LoLT to teach African learners

Of 400 Grade Four teachers, most reported a positive attitude towards the use of African languages to teach African learners. In line with the items loaded on the African language preference factor, teachers' responses indicated that using African languages to teach African learners enables them to express themselves better, improves understanding, and allows them to show their intelligence. Table 1 displays the results of descriptive analysis for factors of language attitudes.

Table 1 indicates that African language preference has the highest mean (N=397, M=39.30) and is thus deemed to be the most important factor. Teachers were responding to the statement that teaching in African languages at Grade Four level would show the intelligence of African learners. The latter was followed by English language preference (N=394, M=34.3); teachers responded to questions about whether one needs English to understand academic ideas and whether using English for teaching is a way of remaining competitive and keeping standards high. Then followed African languages challenges (N=396, M=25.3). In this section teachers answered questions on whether learners can or cannot use the standard version of African languages and whether it is difficult for most African learners to read and write in their own languages. The factor with the smallest mean was African identity language and development. See Figure 1.

African learner difficulty with English as LoLT

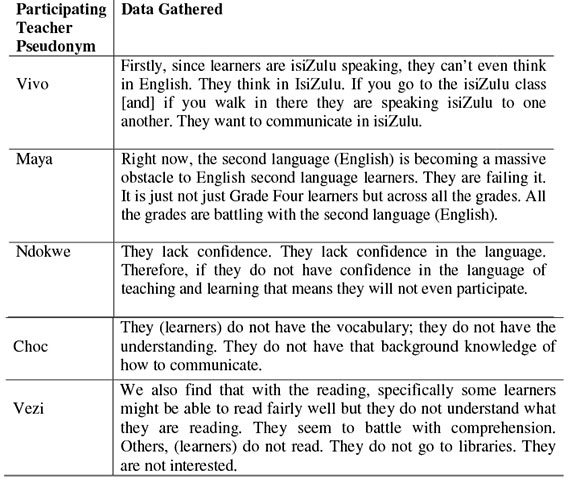

Participant teachers reported that most learners who are speakers of African languages at Grade Four level in South African schools do not understand English as their LoLT and are unable to access the curriculum content knowledge.

The excerpts above show that most African learners are not coping with English. When these learners reach Grade Four the language they know and identify with is no longer being used. These learners bring into the classroom a wealth of language skills in their mother tongue, which is not used during the learning process. Most learners think and understand their worlds in isiZulu, which is the known and familiar language that contains blueprints of their cultural knowledge, cultural values. and epistemologies. It is important to note that if the mother tongue language that these learners bring to school is not used such learners will not have access to knowledge that is presented in English and they will be capable of only minimal participation in the learning process. The result is most likely to be shallow learning and misunderstanding of the concepts.

Teacher-difficulty in teaching African learners using English as LoLT

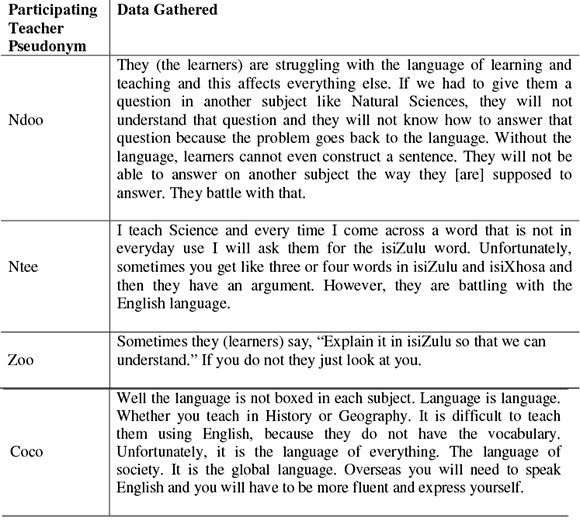

Grade Four teachers reported that they have trouble teaching most African learners using English as the medium of instruction.

The teachers' responses above indicate the difficulty they experience in teaching African learners using English as LoLT. Primarily, teachers agreed that learners are struggling with English and this affects everything; it was implied that no effective learning and teaching could happen under these conditions. Teachers struggle to give instructions to African learners in English. Learners do not understand English and sometimes demand that teachers explain in IsiZulu. This situation forces the teachers to codeswitch to the learners' mother tongue to resolve the problem. However, what happens if the teacher does not understand the home language of the learners? Teachers indicated that they ask learners for the meaning of the English word in isiZulu or isiXhosa. In this case, because the learners do not know the meaning of the English word they might give the teacher any word that comes to mind to make him or her happy. We can see, quite clearly, that if LoLT is not the learners' or the teacher's mother tongue or if both the learners and the teachers are not highly proficient in LoLT, effective learning and teaching is hindered in the classroom, and the two-way interaction of learning through interaction as outlined earlier is destroyed.

Discussion

Drawing from the South African context of the Language in Education Policy formulation, the introduction of the Incremental Implementation of African languages (IIAL) in South African schools was welcomed as the greatest move towards strengthening the use of African languages as subjects at school. However, "the dropping of the LoLT issue [African languages as LoLT] represents a missed opportunity to address the learning crisis in the majority of schools" (Pluddemann, 2015, p. 191). The implication of the latter statement for South African education is clearly articulated in the survey and focus group responses of Grade Four teachers presented above.

The following discussion on the coloniality of LoLT points to the opportunity missed by the South African Department of Education and calls for the reinstatement of African languages as EDLoLT to teach African learners.

Colonial LoLT vs EDLoLT

The dominance of the English language and its use in most African education systems is indicative of its colonial oppressive nature that continues to haunt most African education systems and has resulted in African languages shifting to the background and becoming underdeveloped (Brock-Utne & Mercer, 2014; Mohr & Ochieng, 2017; Olajide, 2010; Prah, 2010). The English language carries Eurocentric culture, worldviews, and knowledges that align themselves with Eurocentric modernity, although some literature in post-colonial and sociolinguistic studies of world Englishes shows how English has been appropriated and localized in different parts of the world (Bamgbose, 1998; Saraceni, 2017). Its colonial nature is evident when it is used in an African context as the dominant language in education. This means that when an African learner enters formal schooling and brings along his or her mother tongue language to navigate learning, he or she is confronted with the schooling system that enforces English as LoLT. In this way, African learners are denied the privilege of using and upholding their cultural ways of knowing and their knowledge systems and are prevented from using their mother tongue languages to navigate learning in favor of Eurocentric modernity. In this manner, African learners are socialized to think epistemically like Euro-American individuals (Grosfoguel, 2011).

English becomes a factor of coloniality or a colonial LoLT. As noted above, the concept of coloniality refers to the aftermath of colonisation and its practices that have remained in place after the colonial rule had been "displaced" (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2013, p. 13). Using English to teach African learners indicates the use of a colonial LoLT, the language that does not affirm African identity and does not ensure the regaining of African dignity that was destroyed by the colonial powers. Most research has suggested that the use of English as LoLT to teach the African learner does not have any educational benefits and secures, instead, the alienation of the African learner from his or her own reality and creates a barrier to access to knowledge (Chivhanga & Chimhenga, 2013; Sibanda, 2014; Webb, Lafon, & Philips 2010). Language is not neutral; it is a carrier of beliefs, cultural values, and worldviews. In the process of using English as LoLT, the idea of western civilization and culture, with its life styles that are seen to be perfect becomes something to pursue and aspire to in order to achieve success and this is injected into the minds of African learners.

Most importantly, the social context and cultural aspect of the child's learning is disturbed. Socially, the African learner in this situation is unable to interact meaningfully with capable others, characterized by meaning-making, during the learning process. Not only do these learners not understand English, this language as LoLT blocks the communication process between peer learners and teachers and hinders the process of mediation (Liang, 2013; Wertsch, 1990) and the effective internalization of knowledge by the mind from the social context.

If the learners' language is the prism through which they see the world, then language becomes more than just the symbols that they use to communicate in that it also shapes how they think, and thoughts control behavior. When a learner learns a home language, it gives her or him a worldview that is based on a particular culture. This worldview becomes the reference point from which this human being interprets the world around her or him through the language. African learners, when they learn their mother tongue language at home, develop an African culture-based worldview. This is a powerful cultural tool the African child brings into the classroom to navigate the acquisition of new knowledge and skills.

The teachers said that when learners do not understand them they codeswitch to the learners' mother tongue to explain difficult concepts. Teachers then explain better and the learners are better able to understand concepts. It is likely that most teachers' preference for African languages as LoLT, as reflected in the survey responses, implies the perfect match between their worldviews, ways of knowing, cultures, and languages with that of the learners. It also indicates the meeting of minds among learners themselves, their worldviews, and their language. It is vital to note that it is when a language plays an emancipatory role, in the sense that it facilitates the perfect alignment of the oppressed or exploited group's worldviews with their cultural knowledges we can regard it as an EDLoLT. If this concept is applied in South African schools, we would use African languages to teach African learners, thereby aligning their worldview, cultures. and language for the purpose of ensuring quality learning and teaching. In other words, EDLoLT connects the African epistemologies with African culture to navigate the acquisition of new knowledge that will determine the new order of the world and accommodate multiple epistemologies and knowledge systems to emancipate the groups of people that are located on the oppressed side of the world (Mignolo, 2011).

Conclusion

The findings in this study reveal that most Grade Four teachers prefer to use an African language as LoLT to teach African learners and that many Grade Four learners are struggling with English. The mother tongue is, clearly, a perfect link between the subject content knowledge and the learner's worldview and ways of knowing. Teachers in these classrooms identified the language problem and tried to solve it by codeswitching (Creese & Blackledge, 2010) to the home language of the learners but their resolution was effective for a short time only. I call for the full implementation of the South African Language in Education policy and for the reinstatement of African languages as LoLT at least through the primary phase given the structural challenges of affordances that could accompany the use of African languages in South Africa. Some teachers in their responses indicated the power of English. It also reminds us of the power of colonialism especially in the case of the teacher who sees English as the world language. Finally, while acknowledging the work done by researchers on bilingualism/multilingualism (Hornberger & Link, 2012; Wei, 2014) it is vital to caution against a tendency to assert that bi/multilingualism is a combination of African languages with dominant colonial languages only, since this affirms the dominance of certain languages over the others.

References

Adams, G., & Estrda-Villalta, S. (2017). Theory from the south: A decolonial approach to the psychology of global inequality. Current Opinion in Psychology, 18, 37-42. [ Links ]

Adesemowo, A. K. (2017). Multilingualism as a learning scaffolding element: Reflection on first-year information communication technology networking students. South African Journal of African Languages, 37(1), 11-16. doi:10.1080/02572117.2017.1316922 [ Links ]

Alexander, N. (2009). The impact of the hegemony of English on access to and quality of education with special reference to South Africa. Language and Poverty, 141, 53 66. [ Links ]

Alidou, H., Boly, A., Brock-Utne, B., Diallo, Y. S., Heugh, K., & Wolff, H. E. (2006). Optimizing learning and education in Africa: The language factor. Paris, FRA: ADEA. [ Links ]

Bamgbose, A. (1998). Torn between the norms: Innovations in world Englishes. World Englishes, 17(1), 1-14. [ Links ]

Banda, F. (2000). The dilemma of the mother tongue: Prospects for bilingual education in South Africa. Language Culture and Curriculum, 13(1), 51-66. doi:10.1080/07908310008666589 [ Links ]

Batibo, H. (2015). The prevalence of cultural diversity in a multilingual situation: The case of age and gender dimensions in the Shisukuma and Kiswahili greeting rituals. Journal of Multicultural Discourses, 10(1), 100-111. doi:10.1080/17447143.2014.993398 [ Links ]

Brock-Utne, B., & Mercer, M. (2014). Languages of instruction and the question of education quality in Africa: A post-2015 challenge and the work of CASAS. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 44(4), 676-680. [ Links ]

Cabansag, J. N. (2016). The implementation of mother tongue-based multilingual education: Seeing it from the stakeholders' perspective. International Journal of English Linguistics, 6(5), 43-53. [ Links ]

Chivhanga, E., & Chimhenga, S. (2013). Language planning in Zimbambwe: The use of indigenous language (Shona) as a medium of instruction in primary schools. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 12(5), 58-65. [ Links ]

Collins, P. H. (1990). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness and the politics of empowerment. New York, NY: Routledge, Chapman and Hall. [ Links ]

Creese, A., & Blackledge, A. (2010). Translanguaging in the bilingual classroom: A pedagogy for learning and teaching? The Modern Language Journal, 94(1), 103-115. doi:10.1111/J.1540-4781.2009.00986.x [ Links ]

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2010). Designing and conducting mixed methods (2nd ed.). London, UK: SAGE Publication. [ Links ]

Cummins, J., Mirza, R., & Stille, S. (2012). English language learners in Canadian schools: Emerging directions for school based policies. TESL Canadian Journal, 29(6), 25-48. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education. (2013). Annual national assessment: 2013 diagnostic report and 2014 framework for improvement. Pretoria, RSA: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education. (2014). Annual national assessment 2014: Diagnostic report first additional languages and home languages. Pretoria, RSA: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Department of Education. (1997). Language in Education Policy. Pretoria, RSA: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Grosfoguel, R. (2011). Decolonizing post-colonial studies and paradigms of political-economy: Transmodernity, decolonial thinking, and global coloniality. Transmodernity: Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production of Luso-Hispanic World, 1-38. Retrieved from http://escholarship.org/uc/items/21k6t3fq

Haraway, D. (1988). Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of portal perspective. Feminist Studies, 14, 575-599. [ Links ]

Hornberger, N. H., & Link, H. (2012). Translanguaging and transnational literacies in multilingual classrooms: A biliteracy lens. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 15(3), 261-278. doi:10.1080/13670050.2012.658016 [ Links ]

Hugo, A., & Lenyai, E. (2013). Teaching English as a first additional language in the foundation phase: Practical guidelines. Cape Town, RSA: Juta Academic. [ Links ]

Kirui, K. E. J., Osman, A., & Naisujaki, L. (2017). Attitudes of teachers towards the use of English language as a medium of instruction in secondary schools in Republic of Tanzania: A pragmatic perspective of community secondary schools in Arusha district. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 4(9), 105-117. [ Links ]

Lantolf, J. P., & Thorne, S. L. (2000). Sociocultural theory and second languge learning. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Liang, A. (2013). The study of second language acquisition under sociocultural theory. American Journal of Education, 1(5), 162-167. [ Links ]

Madiba, M., & Mabiletja, M. (2008). An evaluation of the implementation of the new Language-in-education policy (LIEP) in selected secondary schools of Limpopo Province. Language Matters, 39(2), 204-229. doi:10.1080/10228190802579601 [ Links ]

Makalela, L. (2015). Moving out of linguistic boxes: The effect of translanguaging strategies for multilingual classroms. Language and Education, 29(3), 200-217. doi:10.1080/09500782.2014.994524 [ Links ]

Makoni, S., & Pennycook, A. (2005). Disinventing and (re) constituting languages. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies: An International Journal, 2(3), 137-156. [ Links ]

Makoni, S., & Pennycook, A. (2012). Disinventing multilingualism. From monolingual multilingualism to multilingual francas. In M. Martin-Jones, A. Blackledge, & A. Creese (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of multilingualism (pp. 439-453). London, UK: Routledge. [ Links ]

Marrow, W. (1994). Entitlement and achievement in education. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 13(1), 33-47. [ Links ]

Mckinney, C., Carrim, H., Layton, L., & Marshall, A. (2015). What counts as language in South African schooling? Monoglossic ideologies and children's participation. AILA Review, 28(1), 103-126. [ Links ]

Mignolo, W. D. (2011). The dark side of Western modernity: Global futures, decolonial options. Durham, NC: Duke University. [ Links ]

Mohanty, A. K. (2012). MLE and the double divide in multilingual society: Comparing policy and practice in India and Ethopia. In T. Skutnabb-Kangas & K. Heugh (Eds.), Multilingual education and sustainable diversity work: From pheriphery to centre (pp. 138-150). New York, UK: Routledge. [ Links ]

Mohr, S., & Ochieng, D. (2017). Language usage in everyday life and in education: Current attitudes towards English in Tanzania: English is still preferred as medium of instruction in Tanzania despite frequent usage of Kiswahili in everyday life. English Today, 33(4), 1-7. doi:10.1017/S0266078417000268 [ Links ]

Mweli, P. (2018). Indigenous stories and games as approaches to teaching within the classroom. In I. Eloff & E. Swart (Eds.), Understanding educational psychology (pp. 94-101). Cape Town, RSA: JUTA. [ Links ]

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. (2013). Empire, global coloniality and African subjectivity. New York, NY: Berghahn. [ Links ]

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. (2015). Decoloniality in Africa: A continuing search for a new world order. Australasian Review of African Studies, 36(2), 22-50. [ Links ]

Ngugi wa Thiong'o. (1986). Decolonising the mind: The politics of language in African literature. London, UK: James Currey. [ Links ]

Olajide, S. B. (2010). Linking reading and writing in an English-as-a-second-language (ESL) classroom for national reorientation and reconsruction. International Education Studies, 3(3), 195 200. [ Links ]

Pluddemann, P. (2013). Language policy from below: Bilingual education and heterogeneity in post-apartheid South Africa (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Stockholm University, Sweden. [ Links ]

Pluddemann, P. (2015). Unlocking the grid: Language-in-education policy realisation in postapartheid South Africa. Language and Education, 29(3), 186-199. doi:10.1080/09500782.2014.994523 [ Links ]

Prah, K. K. (2010). Multilingualism in urban Africa: Bane or blessing? Journal of Multicultural Discourses 5(2), 169-182. [ Links ]

Prinsloo, D. (2007). The right to mother tongue education: A multidisciplinary, normative perspective. South African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies, 25(1), 27-43. [ Links ]

Quijano, A. (2000). Coloniality of power and social classification. Journal of World Systems, 6(2), 342-386. [ Links ]

Saraceni, M. (2017). World Englishes and linguistic border crossings. In E. L. Low & A. Pakir (Eds.), World Englishes (pp. 154-171). London, UK: Routledge. [ Links ]

Sibanda, J. (2014). Investigating the English vocabulary needs, exposure, and knowledge of Isixhosa speaking learners for transition from learning to read in the foundation phase to reading to learn in the intermediate phase: A case study (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Rhodes University, Grahamstown, RSA. [ Links ]

Sibanda, J. (2017). Language at the Grade three and four interface: The theory-policy-practice nexus. South African Journal of Education, 37(2), 1-9. [ Links ]

Sibanda, J., & Baxen, J. (2016). Determining ESL learners' vocabulary needs from a textbook corpus: Challenges and prospects. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies, 34(1), 57-70. [ Links ]

Skutnabb-Kangas T. (2017) Language rights and bilingual education. In O. García, A. Lin, & S. May (Eds.), Bilingual and multilingual education: Encyclopedia of language and education (3rd ed., pp. 51-63). Cham, Switzerland: Springer. [ Links ]

Spear, T. (2003). Neo-traditionalism and the limits of invention in British colonial Africa. Journal of African History, 44(1), 3-27. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0021853702008320 [ Links ]

Swain, M., Kinnear, P., & Steinman, L. (2010). Sociocultural theory in second language education: An introduction through narratives. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters. [ Links ]

UNESCO. (2014). Teaching and learning: Achieving quality for all. Paris, France: UNESCO. [ Links ]

Vandeyar, S., & Killen, R. (2006). Teachers-student interactions in desegregated classrooms in South Africa. International Journal of Educational Development, 26, 382-393. [ Links ]

Webb, V., Lafon, M., & Philips, P. (2010). Bantu languages in education in South Africa: An overview. Ongekho akekho - The absentee owner. Language Learning Journal, 38(3), 273 292. [ Links ]

Wei, L. (2014). Researching multilingualism and superdiversity: Grassroots actions and responsibilities. Multilingua-Journal of Cross-Cultural and Interlanguage Communication, 33(5-6), 475-484. doi:10.1515/multi-2014 - 0024 [ Links ]

Wertsch, J. V. (1985). Vygotsky and the social formation of mind. Cambridge, MA: Havard University Press. [ Links ]

Wertsch, J. V. (1990). The voice of rationality in a sociocultural approach to mind. In L. C. Moll (Ed.), Instructional implications and applications of socio-historical psychology, (pp. 111-126). New York, NY:Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Wertsch, J. V. (2007). Mediation. In H. Daniels, M. Cole, & J. V. Wertsch (Eds.), The Cambridge companion to Vygotsky (pp. 178 192). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Wigglesworth, G., Simpson, J., & Loakes, D. (2011). Naplan language assessments for indigenous children in remote communities: Issues and problems. Australian Review of Applied Linguistics, 34(3), 320 343. [ Links ]

Received: 8 May 2018

Accepted: 4 October 2018

1 The focus in this article is on language as a tool to navigate learning and teaching in the classroom.