Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of Education (University of KwaZulu-Natal)

On-line version ISSN 2520-9868

Print version ISSN 0259-479X

Journal of Education n.70 Durban 2017

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Attributes for the field of practice of the administrator and office manager

Shairn Hollis-Turner

Cape Peninsula University of Technology. hollis-turners@cput.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The arrangements for the curriculum for administration studies are based mainly on the work of the administrator in support of people in different professions, industries, and contexts. The research objectives on which this study focused, aimed to identify those attributes which are considered legitimate for carrying out office management work, and to establish the attributes required by graduates of the National Diploma in Office Management to enter the field of practice. The utilisation of the Specialisation dimension of Legitimation Code Theory (Maton, 2014) enabled the identification of the attributes required for graduates to function effectively in the workplace. A Delphi approach comprising three rounds of surveys was utilised and distributed to employers, academics and graduates. A survey was also distributed to third year and alumni students. The findings show that the employers and practitioners have strong consensus on the generic qualities such as self-management, participating in team work, having honesty and integrity and applicable attitudes and conduct for graduates entering the field of practice. This is significant as these attributes are considered legitimate for the expected identity of administrators and office managers in future professional practices.

Introduction

Different names are attributed to administrators such as 'secretaries', 'office managers', 'data processors', 'typists' or 'personal assistants', which are dependent on the kind of work they are expected to do. Curricular arrangements for office administration studies are largely founded on the work of administrators in support of individuals in a range of different contexts, industries and professions. Training programmes for secretarial and office workers have been strongly swayed by prevailing thinking about administration, namely, that such work is repetitive and unskilled. There is a significant lack of attention paid to the work and training of secretaries and administrators (Truss, Alfes, Shantz & Rosewarne, 2013). During World War I, the need for secretarial training arose when young women entered the workplace as typists. The general practice for young women interested in a career in administration was to complete their schooling and then to enrol in specialist secretarial training colleges. Many secretaries and clerical workers also received on-the-job training in the workplace (Waymark, 1997). Since administrative work was deemed routine, training colleges developed arbitrary programmes of single subjects and only equipped individuals for basic office work (Waymark, 1997). Training usually focused on the shorthand and typing skills essential for secretarial work.

In the early twentieth century, many clerical workers favoured being called 'secretaries', as the term was distinct from the role of the stenographer, considered to be more mechanical work, and the term had connotations of a higher status (Solberg, 2014). However, many employers considered administrative work to be 'mechanical', and their attention was on the secretaries' abilities to convey or record communication by means of shorthand and typing. Russon (1983) argued that the work of secretaries and administrators necessitated a high level of competence in language and in some instances, several languages, implicit and explicit communication, interpretations of communication, technical and business communication, and knowledge of the management of organisations. Administrators and office managers are in charge of the administration of external and internal information flow and safeguarding the confidentiality of corporation information (Biebuyck, 2006). Thus, the innately social nature of the positions of office administrator and office manager are obvious; however, these attributes have not been widely recognised.

It is evident that there are wide differences regarding the roles and attributes expected of secretaries and administrators. Views range from Kanter's (1977, p.89) disparaging "office wife" to Holten-Moller and Vikkelso's (2012) report of the role played by medical secretaries. It has been established that secretaries and administrators, while executing routine tasks, also need to have loyalty, the ability to work in a team and personal attributes of calmness, reliability, discretion and tact (Waymark, 1997).

Research undertaken on business administration graduates who had completed an internship of six months in the workplace found that in addition to the disciplinary knowledge requirements of Information and Business Administration, personal attributes of enthusiasm, adaptability, good listening and human relations skills, problem-solving and assertiveness skills are highly valued. Interns should be able to work independently, have perseverance and be able to make decisions (Hollis-Turner, 2008). However, while these attributes are significant, they would fit practically any professional context as they are generic.

Stemming from the above, the research on which this article is based aimed to investigate what are considered legitimate attributes, values, knowledge and skills for the role of administrator to function effectively in the workplace. The principle of Specialisation investigates what makes something or someone special, different and worthy of distinction (Howard & Maton, 2011). Drawing on the principle of Specialisation enables an investigation of what attributes, values, knowledge and skills should comprise the National Diploma in Office Management (ND:OM) curriculum.

The research on which this paper is based found that the knowledge bases of the curriculum were information technology, communication, business administration and interpersonal skills in support of the efficient management of the administration of corporations (Hollis-Turner, 2015a). However, for the purpose of this paper the focus will be on those social attributes considered legitimate for administrators to function effectively in the dynamic workplace. The research on which this paper is based had the following objectives: 1)To determine what attributes are considered legitimate for the role of administrator to function effectively in the workplace, and 2) to establish the attributes required by graduates of the National Diploma in Office Management to enter future professional practices.

Literature review

Universities have for many centuries been known as sites for the promotion of academic engagement and for the development of rational and ethical reasoning. However, Nel & Neale-Schutte (2013) point out that governments worldwide have become increasingly concerned about the role of higher education institutions to enhance the employability of graduates. This has resulted in increased pressure on higher education to improve the employability of graduates by ensuring that students' learning experiences contribute to inculcating the knowledge, attributes and skills that will enable graduates to "perform successfully as citizens in the knowledge economy" (Nel & Neale-Schutte, 2013, p.437). Badat (2010) cautions that graduate attributes should be targeted at the holistic advancement of students and not only at training students for occupations in the knowledge economy. Teichler (2009) describes the worldwide views of industry and employers as the focus on skills and disciplinary knowledge in higher education. He contends that this is imperative but insufficient for graduates to acquire employment. Higher education should therefore focus more on the nurturing of "competences beyond systematic cognitive knowledge" (Teichler, 2009, p.197).

In this context, Wheelahan and Moodie (2011) assert that this assumed mismatch between the workplace and higher education, the fast pace of technological, economic and social changes and the pressures of the knowledge economy have promoted an emphasis on graduate attributes or generic competencies in higher education policy. For example, graduate attributes or generic competencies are referred to in various forms: key competencies (Mayer Committee, 1992), cross-field outcomes or critical skills (South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA), 2000), capabilities (Stephenson, 1998) or professional capabilities (Walker, 2012) or generic graduate attributes (Barrie, 2007). It also supports the question arising from the debate regarding the intent of higher education and the development of educated people who are employable and who can contribute to society (Hager & Holland, 2006).

Bosanquet, Winchester-Seeto and Rowe (2010) reviewed the literature on the development of graduate attributes in higher education and contend that these appear to focus on four key arguments. These are the perception of education as a process of learning which is lifelong; graduate employability; the promotion of outcome measures to affirm the value of higher education, and the need for the preparation of students for a future which is uncertain and working for the social benefit of society (Barnett, 2004; Pitman & Broomhall, 2009). This is a future which is highly complex comprising changeability, contestations and uncertainty (Bosanquet et al., 2010). Barnett (2006, p.50) contends that this uncertainty requires graduates to acquire "new knowledges, new adaptations and new skills". The consequences of this uncertainty in the world is an immense challenge to education institutions (Jackson, 2011b, p.11) as "change is exponential and we are currently helping to prepare students for jobs that don't yet exist, using technologies that have not yet been invented in order to solve problems that we don't know are problems yet". Higher Education therefore has the task of preparing "the ground for forms of human being that are going to be able to withstand profound and incessant change" - graduates that are fit for a future life (Barnett, 2006, p.51).

The problem facing higher education is determining its role in preparing students for a changing world and whether higher education is about preparing students to acquire employment, inducting students into knowledge-based practices or whether learning should not merely be understood as the acquisition of skills and knowledge but instead as developing "human qualities and dispositions" (Barnett, 2004, p.247). Barnett (2004) further contends that the role of higher education is to prepare students for a future which is unknown. Higher education is confronted by the challenge of how to ensure that graduates attain the understanding, knowledge, soft skills and personal attributes essential in the dynamic workplace (ACT Inc., 2013). Numerous reports investigating the role of higher education, such as the Robbins Report (1963), the Dearing Report (1997) in the UK, the Report on Employability Skills for Australian Industry (Curtis & McKenzie, 2002); and Confederation of British Industry (CBI) Universities UK Report (2009) all accentuate the task of higher education to prepare graduates for the challenges of a worldwide knowledge-based economy.

Slonimsky and Shalem (2006, p.38) are of the opinion that academic practices include "both disciplined and disciplinary activities, involving specialised actions and operations, which promote the development of knowledge". Regardless of a student's potential "if they do not have opportunities to participate in activities that develop specialised forms of knowledge and functioning and/or are not afforded sufficient opportunities of mediation by others experienced in those activities, they are unlikely to develop such forms of functioning" (Slonimsky & Shalem, 2006, p.49). Their analysis of a course which builds epistemic access effectively includes taking students through four aspects of activity in various ways and at various stages of engagement, thereby inducting them into knowledge-based practices (Slonimsky and Shalem, 2006) and building academic depth. The research on which this article is based contends that the role of higher education is rather about the growth of professionals with specialised expertise in a field of knowledge, and the personal attributes and skills necessary for the field of practice (Hollis-Turner, 2015b).

Dall' Alba and Barnacle (2007, p.683) argue that "Knowledge remains important" but the focus on the education of students should be "not what they know, but also who they are becoming". Jackson (2011a) argues that higher education needs to broaden its focus on cognitive development to assume a life-wide concept for education that may be described as contributing to the holistic development of a person. Graduate attributes in this sense comprise a graduate's totality of experiences, namely, cognitive, personal and social. The focus of higher education should rather support the self-actualisation of the student and not just the preparation of graduates for employability (Jackson, 2011b). The South African Council on Higher Education contends that one of the prerequisites for the enhancement of the curriculum is the advancement of graduate attributes not related to fundamental disciplinary learning, but to life skills and the foundation for critical citizenship. The report notes that "there is strong interest in the concept of social responsiveness and how experience with it can be included in educational programmes, to foster cultural sensitivity and civic engagement" (Council on Higher Education (CHE), 2013, p.96).

The National Diploma in Office Management falls within the area of the new professions as described by Muller (2009). These comprise fields such as tourism, business studies, and information science. As a professionally oriented curriculum the diploma draws on applied disciplinary knowledge which comprises knowledge that has been "recontextualised for application in the field of practice, and then again recontextualised for curriculum" (Wheelahan, 2010, p.157). Wheelahan (2009, p.240) contends that professional curricula must include "learning in the workplace but that learning cannot be limited to the workplace". She further asserts that it is imperative to provide students with opportunities to attain systematic disciplinary knowledge to allow them to advance the kind of thinking that arises from such engagement (Wheelahan, 2010). This is the objective of the Office Management curriculum offered at a university of technology as it focuses on the training of graduates with critical office management knowledge and skills to take up positions of administrative and office management positions in the workplace and the future workplace. While similar programmes are offered at a Further Education and Training college (FET) these focus on the training of graduates to take charge of all aspects of any administrative or secretarial position (Hollis-Turner, 2015b).

Theoretical framework

The theoretical framework that underpins this article is that of Legitimation Code Theory (LCT), particularly the Specialisation dimension since professional curricula are overtly about the establishment of a specific kind of knower or "projected identity" (Bernstein 2000, p.55). LCT extends principle concepts of Bernstein and Bourdieu. LCT is a framework for investigating the structuring of practices and knowledge within intellectual and pedagogical fields (Maton, 2000; Moore & Maton, 2001; Maton & Muller, 2007). LCT offers insight into the "recontextualization of theoretical knowledge for vocational purposes" (Shay, 2013, p.577), which comprise significant pedagogical and curriculum challenges.

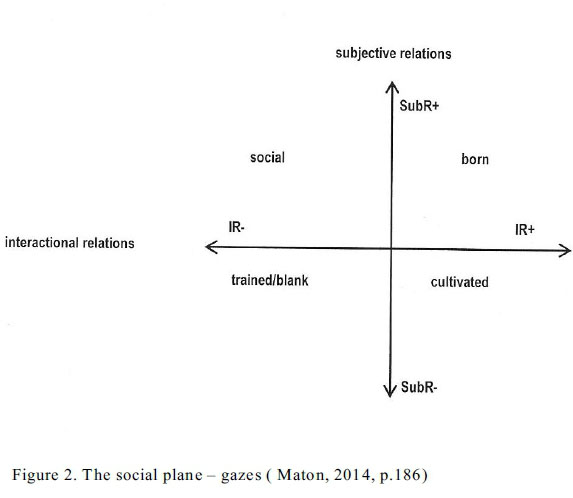

The Specialisation dimension may be defined as "what makes someone or something different, special and worthy of distinction" (Howard & Maton, 2011, p.196). Specialisation codes can differentiate the "epistemic relations (ER) between practices and their object or focus; and social relations (SR) between practices and their subject, author or actor" (Howard & Maton, 2011, p.196). Epistemic and social relations may be more strongly or weakly stressed in beliefs and practices and envisaged on x and y axes of a Cartesian plane. Specialisation codes focus on the questions of: "what can be legitimately described as knowledge (epistemic relations); and who can claim to be a legitimate knower (social relations)" (Maton, 2014, p.29). Maton (2014, p.75) contends that for "every educational knowledge structure there is also an educational knower structure" and LCT aims to establish which of these is highlighted in practices and knowledge assertions.

Specialisation codes are defined as follows: knowledge codes (ER+, SR-) where possession of specialised knowledge of specific objects of study is emphasised as the basis of achievement; and knower codes (ER-, SR+), where specialised knowledge and objects are less significant and instead the attributes of actors are emphasised as measures of achievement. There are also élite codes (ER+, SR+), where legitimacy is based on both possessing specialist knowledge and being the right kind of knower; and relativist codes (ER-, SR-), where legitimacy is determined by neither specialist knowledge nor knower attributes (Maton, 2014). Refer to Figure 1 below for the specialisation codes.

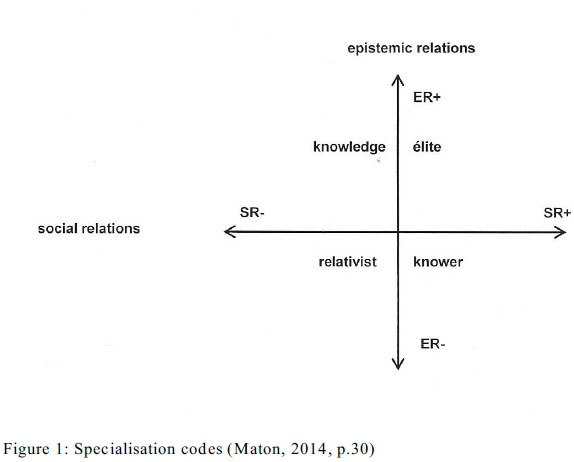

A second level of analysis is utilised in the identification of different kinds of knower codes (Maton, 2014). Two kinds of social relations are distinquished, namely, subjective relations (SubR) and interactional relations (IR). Subjective relations is "between knowledge practices and 'kinds of knowers'" (Luckett & Hunma, 2014, p.186) such as the gender, race, social class which are probable categories for describing knowers. Interactional relations (IR) "between knowledge practices and 'ways of knowing'" (Luckett & Hunma, 2014, p. 186) comprise relations with significant others such as interactions between mentor and mentee. Both relations may be stronger or weaker, the variations of which generates four "gazes" (Maton, 2014, p. 85). The concept of gazes builds on Bernstein's premise of the "acquired gaze" where a gaze was described as "a particular mode of recognising and realising what counts as an 'authentic'. . .reality" (2000, p. 164). The four gazes comprise:

• the trained gaze which has weaker social and interactional relations and is acquired through training in "specialized principles or procedures" (Maton, 2014, p. 95);

• the cultivated gaze which has weaker social relations but stronger interactional relations where legitimacy arises of the knower's dispositions that can be taught through prolonged exposure, such as an apprentice to that of a master;

• the social gaze which has stronger social relations and weaker interactional relations where the legitimate knower possesses a social gaze determined by their social category of race, gender etc., and

• the born gaze which has stronger social and interactional relations and illustrated by the legitimate knower possessing a "natural talent" (Maton, 2014, p. 95). Refer to Figure 2 below for the social plane and gazes.

This paper will focus on the social relations of the knower code which are evidence that the work of administrators and office managers involves the support of the work of others in the workplace.

Overview of the office management curriculum

The National Diploma in Office Management curriculum occupies a position within the field of Business and Management Sciences. As a field of study office management can be defined as a type of vertical discourse with a horizontal knowledge structure (Bernstein, 2000) which has soft or weak boundaries which differs from the more strongly classified disciplines such as law and the natural sciences. As a result, the field absorbs most of its concepts and practices from disciplines, such as the wider sphere of management practice (Oswick, Fleming & Hanlon, 2011).

The purpose of the Diploma is the training of administrators and office managers who will provide the corporate sector with graduates proficient in administration, management and technology. This field of study aims to be responsive to the rapidly changing world of business and is driven by new technologies, new regions of work and the demands of globalisation (Miller, 2010). It is a three year programme comprising 360 SAQA credits including the major fields of study of Information Administration and Business Administration which is offered during the 1st, 2nd and 3rd years of study. Communication is presented during the 1st and 2nd years of study, and each of the subjects of Financial Accounting, Legal Practice, Mercantile Law and Personnel Management are offered at 1st year level. A six-month internship period is offered during the 3rd year of study where graduates enter the workplace in the legal, tourism, medical, retail, education, financial, government, and local government fields (Hollis-Turner, 2015b).

Research methodology

A multi-method approach included the views of graduates, employers and academics, and provided an opportunity for them to convey their own experiences, expectations, concerns and viewpoints in the research process.

Delphi is a recognised method used to gain the opinions of a diverse group of experts (Powell, 2003) and to generate opportunities for the analysis of knowledge and learning from the experts as they honed their opinions and attained consensus. This allowed for the experts to refine their opinions over three rounds of surveys over a period of three years. The critical cross-field outcomes of the South African Qualifications Authority, NSB Regulations (Nkomo, 2000) and 13 personal attributes from the Employability Skills Framework of the Australian Qualifications Framework (Bowman, 2010) were utilised. In response to feedback from the participants of the pilot study, the 13 personal attributes were modified to include additional personal attributes considered legitimate to the role of the administrator for the round three survey.

The Delphi panel comprised three types of experts, all of whom have workplace experience, namely, graduates, employers as business experts, and academics. The responses of the panel to each question on the survey were compared and analysed to determine the consensus scores of each individual group in addition to the average consensus ratings of the responses of the three expert groups. Delphi participants were requested to include other attributes they considered legitimate to the role of the administrator and which were included in the next round of surveys. This allowed for the identification of what the Delphi panel considered as the legitimate attributes required for the role of administrators and office managers. Both quantitative and qualitative data were obtained from the Delphi surveys, the reliability of which was attained through continuous verification throughout the process.

The research project on which this paper is based extended the traditional opinion of the Delphi method of 'expert' as the Delphi panel included not only employers, but also graduates of the ND:OM (Hollis-Turner, 2015b). Purposive sampling was used for the selection of the Delphi panel experts which allowed for in-depth information to be acquired for a specific intention from a concerned group of participants (Maree, 2007). Fifteen graduates, twenty-three employers and fifteen academics consented to respond to three rounds of Delphi surveys.

The main performance areas assigned to graduates are determined by the culture and size of the organisation at which graduates are employed. Therefore, strict selection criteria were followed to ensure that graduates and business experts were not all chosen from large organisations. Graduates and employers had to be occupied in the major areas of education, tourism, government and local government, production, service and retail industries and medical fields and speak diverse South African first languages such as English, isiXhosa, isiZulu and Afrikaans (Hollis-Turner, 2015b).

The selection criteria for the Delphi panel required that they were situated in the Western Cape. Graduates had to have been employed for at least three years and be occupying office management practitioner and/or managerial positions. Employers had to be operating in medium to high technological milieus locally and internationally. As co-operative partners of the higher education institution they had to be currently employing, or to have had employed office management graduates and/or third-year students as interns. Academics had to have occupied a position in the workplace within the preceding two to four years and have participated in regular meetings with the business sector to remain up-to-date with the field of office administration and office management practices (Hollis-Turner, 2015b). In addition, a survey was disseminated to full-time and part-time third year OM students and to alumni of the National Diploma: OM who were employed, and studying part-time for their Baccalaureus Technologiae (BTech) degree. The survey intended to establish the attributes that graduates required to be effective in the workplace. The respondents included 113 students of whom 43% had completed the ND:OM, were studying part-time for the BTech degree, and were employed as administrative assistants, administrative supervisors, administrative managers, and store managers employed in wholesale, manufacturing, financial, hospitality, public administration, printing, marketing, education, and medical fields.

The adherence to the selection criteria and the relevant ethical considerations for undertaking a research project, enabled participants to consider objectively current office management work practices to establish the attributes considered legitimate for the role of administrators and office managers.

Findings

All the subjects offered in the curriculum include components of the knowledge code. Those knower code subjects with stronger epistemic relations (ER+) are the Financial Accounting, Information Administration, Legal Practice and Mercantile Law syllabi (Hollis-Turner, 2015b).

However, for the purpose of this paper the responses of the Delphi panel to the round three Delphi survey as well as the feedback from the third year students and alumni on the stronger social attributes (SR+) of the knower code considered legitimate for the role of administrators are discussed. The findings comprising the average consensus ratings of the responses of the Delphi panel to the critical cross-field outcomes and personal attributes of 50% and more are presented and analysed. A fourth column comprising a key of analysis is included to show those consensus ratings of the Delphi panel which are aligned or non-aligned on the basis of a variance of 10% or more. In addition, the findings will be discussed to include the extent to which the students' ways of knowing or doing, in other words, their gaze, correlates to a particular base.

Critical cross-field outcomes

The Delphi panel were asked to rate the critical cross-field outcomes which they considered legitimate to the role of administrators and office managers. The consensus ratings are as follows: the critical cross-field outcome which received the highest consensus rating was the ability to organise and manage oneself and one's activities effectively (91%), comprising employer 90%, graduate 91% and academic 92% consensus. This was followed by the outcome to work effectively with others as a member of a team, group, organisation or community (75%) including employer 79%, graduate 75% and academic 71% consensus. These ratings of the Delphi panel show alignment in value placed on these critical cross-field outcomes. This was supported by the the third year and alumni student surveys (71%) which rated team work as essential to success in their current workplace positions. Research undertaken by Lowden, Hall, Elliot and Lewin (2011) regarding employers' opinions of the employability skills of new graduates recognised team work as particularly relevant to workplace success.

The critical outcome of multi-tasking was added to the round one survey by the Delphi panel and received a consensus rating of 68%, comprising employer 63%, graduate 83% and academic 57% consensus. These were followed by the consensus ratings for self-motivation (68%), including employer 63%, graduate 75% and academic 65% consensus; and being able to work under stress (67%) comprising employer 53%, graduate 92% and academic 57% consensus. These findings show that the consensus ratings of the graduates were not aligned and were considerably higher than the ratings of the employers and academics. It is evident that the graduates' considerations are linked to the physical activities in the workplace while those of the employers and academics, many of whom are managers and in senior positions, would be planning and scheduling workplace activities in order to avoid excessive multi-tasking and stressful situations.

The Delphi panel rated ccommunicating effectively using visual, mathematical and/or language skills in the modes of oral and/or written presentation (66%) comprising employer 68%, graduate 51% and academics 78% consensus. The third-year students and alumni (72%) rated communicating with colleagues at all levels essential to their roles as administrators in the workplace. One of the graduates commented that "it is important to be able to communicate with top-level executives". However, the findings show significant non-alignment in that the academics had a considerably higher rate of consensus as opposed to the employers and graduates in this category. There is alignment for the significance of communicating effectively with the third-year students and alumni, and the academics which suggests that within the Diploma programme these areas are considered vital to the success of graduates. Archer and Davison (2008) researched employers' opinions of the attributes of new graduates, at small, medium and large corporations with both UK and international distributions. The findings showed that regardless of the size of the corporation, employers judged attributes such as communication and team-working abilities to be the more important attributes, rather than a good degree qualification.

To collect, analyse, organise and critically evaluate information (56%) with employers 53%, graduates 50% and academics 64% consensus. The attributes of life skills, behaviour and attitudes (56%) comprising employers 52%, graduates 51% and academics 64% consensus. These findings show non-alignment in that the academics have a higher consideration for the legitimacy of these attributes as opposed to the consensus ratings of the employers and graduates. This is evidence of the academics attempt to inculcate these attributes throughout the curriculum in preparation of graduates for the workplace which will be discussed in detail at a later stage.

The data displayed in Table 1 show that the employers in the workplace value team work more highly than communication, while the academics in higher education have an opposing view as they value communication more highly than team work. This is evidence of the varying prerequisites for success in higher education and the workplace and that the experts value different kinds of knowers.

Being able to embrace diversity in the workplace (53%) with employers 42%, graduates 75% and academics 42% consensus and shows the non-alignment of the consensus ratings of the graduates with those of the employers and academics. This suggests that the graduates, the majority of whom are younger than the academics and employers, regard this attribute as highly significant to their success and to their physical activities in the workplace. The consensus ratings of the ability to be compatible with company ethics (51%) comprised employers 52%, graduates 58% and academics 42%. This shows that the academics consensus ratings are non-aligned with those of the employers and graduates. Since diversity in the workplace and ethics is included in the content of the subject, Diversity Management in the new Diploma, this may account for the academics low rating since it was covered in the subject specific ratings by the Delphi Panel. It does appear though that ethics and issues of professionalism bring stronger social relations into the programme because of the spotlight on the knower, however these attributes are considered specialist knowledge required for the field of practice of office management and administration.

The high ratings of the academics for attributes described above may be explained in that the Diploma programme structure aims to cultivate knowers, alongside the disciplinary learning, with life skills such as organisational abilities and team work skills by incorporating team and group work projects requiring students to organise events, such as seminars, workshops and market days. Students are required to collect, analyse, organise and critically evaluate information for presentation at these events and are required to display the behaviour and attitudes of office management practitioners. The Diploma programme structure makes it possible for students to experience an immersion in and prolonged engagement in the field of communication theory and practice. Oral presentations, group and peer feedback and reflective practices are some of the activities of the programme which aim for students to cultivate the gaze of reflexive office management and administrative practitioners. The weaker social relations but stronger interactional relations of the cultivated gaze is where the legitimacy arises of the knower's dispositions that can be learned through prolonged exposure to interactions with academics, as well as with employers who visit as guest speakers and during job-shadowing and internship projects.

The rest of the items received less than 50% consensus from the Delphi panel. Refer to Table 1 for the consensus ratings of the critical cross-field outcomes.

Personal attributes

The Delphi panel rated the personal attributes which they considered legitimate to the role of administrators and office managers. The consensus ratings are as follows: having honesty and integrity (88%), including employer 79%, graduate 100% and academic 86% consensus. The attribute of being reliable (82%), comprising employer 74%, graduate 100% and academic 72% consensus. There is non-alignment of the consensus rating of the graduates as opposed to those of employers and academics with regard to the significance of these attributes. While both the employers and academics have high consensus ratings for these attributes, the findings show that the graduates consider honesty and reliability as highly significant to carrying out their administrative and management roles in the workplace.

The consensus rating for the attribute of being loyal and committed (74%), comprising employer 74%, graduate 92% and academic 57% consensus. The vast non-alignment of consensus ratings of the graduates opposed to the employers and academics is evidence that the graduates rated this attribute as essential to their success in the field of practice of office management and administration. The University of Glasgow undertook research on employers' opinions of the employability skills of new graduates which disclosed that in addition to transferable skills recognised by employers, the need for significant attitudes such as commitment, motivation and tenacity was also considered valuable for graduates entering the world of work (Lowden et al., 2011).

Using one's own intuition to think and work on one's own (74%) was an attribute added to the round one survey by the Delphi panel comprising employer 68%, graduate 67% and academic 86% consensus. Graduates commented that 'using your own intuition' and 'having self-confidence' are important in the workplace. The ability to work independently was rated by 66% of the third-year students and alumni as essential requirements for positions in the workplace. The panel members added punctuality (68%) to the first list of personal attributes with employer 68%, graduate 58% and academic 79% consensus. The significance of these attributes to the academics is evident which will be further discussed at a later stage. There is non-alignment of the graduates' consensus ratings with those of the employers and academics concerning the impact of punctuality on the role of administrator and office manager. The majority of the graduates on the panel did not hold senior or management positions and this may account for the non-alignment of the findings.

The ratings for being motivated (63%) included employer 57%, graduate 59% and academic 72% consensus. The academics' rating of this attribute shows non-alignment with the opinions of the employers and graduates. The consensus ratings for the attribute of being adaptable (61%) shows alignment of the Delphi panel. The consensus ratings of the attributes of possessing common sense (59%) comprising employers 47%, graduates 66% and academics 64%, having self-confidence (58%) with employers 36%, graduates 66% and academics 71%, and dealing with pressure (57%) receiving employers 47%, graduates 66% and academics 57% are non-aligned.

The employer consensus ratings for these attributes are significantly lower than those of the graduates and academics. This may be evidence of the employers' expectations of graduates gaining these attributes with experience and exposure in the workplace while the graduates view these attributes as essential to their physical administrative roles in the workplace. This is supported by the consensus ratings of the graduates for the attributes of going the extra mile and doing more than what is expected (57%) with employers 52%, graduates 75% and academics 43%, and having a positive attitude (56%) comprising employers 52%, graduates 66% and academics 50%, which show higher ratings than those of the employers and academics. The consensus rating for the attribute of possessing a positive self-esteem (56%) is highly rated by the academics 71% and non-aligned with the employers 47% and the graduates 50%. The consensus ratings for the attribute of applying knowledge to new situations (53%) showing employers 51%, graduates 58% and academics 50% are aligned.

The academics high consensus ratings included attributes such as using one's own intuition, punctuality, having honesty and integrity, being reliable, motivated, having self-confidence, and a positive self-esteem". This suggests that the academics see their role as growing professionals by preparing the graduate as a 'whole person' to take up positions in society and to empower graduates with attributes beyond core disciplinary learning. This higher consensus rating is evidence of attempts by academics to enhance the curriculum by promoting students' critical thinking abilities and to work independently. The Diploma programme structure encourages debate and critical thinking which aims to promote over a prolonged period confidence in what the students' know and how they express themselves through opportunities for practice and interactions with academics, employers and peers.

This immersion in the field of office management theory and practice aims to develop a "community of experience" and the "shared sensibilities or dispositions of knowers" (Maton, 2014, p. 100). This emphasises the interactional relations (IR) over the subjective ones (SubR) as a cultivated gaze. However, while the students as knowers are from different cultural backgrounds, have different genders or dispositions and so on, they are all involved in the field of office management and administrative practice. Entry to this field of practice is therefore not restricted on the basis of students having specific attributes.

The rest of the items received less than 50% consensus from the Delphi panel. Refer to Table 2 for the consensus ratings for the personal attributes.

Conclusions

While it is evident that the employers, graduates and academics value different kinds of knowers, the findings show some consensus about the legitimate attributes for the role of administrator and office manager in the workplace. The graduate of the Diploma curriculum should acquire the attributes of honesty, integrity, reliability, loyalty, independence, punctuality, self-motivation, adaptability, common sense, self-confidence, going the extra mile, a positive attitude, self-esteem and the ability to apply knowledge to new situations. Graduates should develop organisational and self-management attributes and should be able to work effectively with others in a team, be able to multi-task, work under pressure, communicate effectively, and collect, analyse, organise and critically evaluate information, acquire life skills, embrace diversity in the workplace, and be compatible with company ethics. The high consensus ratings of the Delphi participants on the importance of critical cross-field outcomes and personal attributes emphasised the need for specific kinds of knowers for the role of administrators and office managers. This is significant as those attributes are considered legitimate for the expected identity of administrators and office managers in future professional practices. These findings support the notion of an ideal knower for the field of practice of office management and administration with a cultivated gaze.

The stronger social qualities of the knower code identified by the experts are all general attributes that would be required in almost any profession. However, it is imperative for the office management and administrative graduate to be able to work across a wide range of areas in supportive administrative and management positions and such a person should therefore be a generalist. In the South African setting the debate about the role of higher education includes opinions of higher education's becoming part of a worldwide knowledge society and economy (Griesel & Parker, 2009). The government and employers recognise the significance of graduates possessing "a range of attributes that empower them as lifelong learners" (Harvey, 2003, p.2). The curriculum should aim to prepare administrators and office managers with the "technical and generic skills for success in their future workplace" (Freudenberg, Brimble, Cameron, MacDonald and English (2013, p.177). This comprises the goal of lifelong learning development to heighten employment opportunities and to attain personal learning objectives (Higher Education Funding Council for England [HEFCE, 2011, p.5]).

References

ACT Inc. (2013). Work readiness standards and benchmarks. http://www.act.org/newsroom/releases/view.php?lang=english&p=2878 [27 December 2014].

Archer, W. & Davison J. (2008). Graduate employability: What do employers think and want? London: Council for Industry and Higher Education (CIHE). [ Links ]

Badat, S. (2010). The challenges of transformation in higher education and training institutions in South Africa. Development Bank of Southern Africa. [Online]. https://www.ru.ac.za/media/rhodesuniversity/content/vc/documents/ The%20Challenges%20of%20Transformation%20in%20 Higher%20Eduaction%20and%20Training%20Institutions%20in%2 0South%20Africa.pdf [Accessed: 25 April 2016].

Barnett, R. 2004. Learning for an unknown future. Higher Education Research and Development, 23(3), 247-260. [ Links ]

Barnett, R. (2006). Graduate attributes in an age of uncertainty. In P. Hager & S. Holland (Eds), Graduate attributes, learning and employment (49-65). Drordrecht: Springer. [ Links ]

Barrie, S.C. (2007). A conceptual framework for the teaching & learning of generic graduate attributes. Studies in Higher Education, 32(4), 439-458. [ Links ]

Bernstein, B. (2000). Pedagogy, symbolic control and identity: Theory, research, critique. (2nd ed.). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. [ Links ]

Biebuyck, C. (2006). Keeper of secrets: company secretaries and information management. Keeping Good Companies, 55(1),10-14. [ Links ]

Bosanquet, A., Winchester-Seeto, T. & Rowe, A. 2010. Changing perceptions underpinning graduate attributes: A pilot study. In M. Devlin, J. Nagy, & A. Lichtenberg (Eds). Proceedings from the 33rd HERDSA Annual International Conference: Research and Development in Higher Education: Reshaping in Higher Education. 33, 105-117.

Bowman, K. (2010). Background paper for the AQF Council on generic skills. The Australian Qualifications Framework Council with funding provided by the Ministerial Council for Tertiary Education and Employment and the Australian Government Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations.

Confederation of British Industry (CBI). Universities UK. 2009. Future fit: Preparing graduates for the world of work. London: CBI. http://www.cbi.org.uk/media/1121435/cbi_uuk_future_fit.pdf [24 April 2009]. [ Links ]

Council on Higher Education (South Africa.). (2013). A proposal for undergraduate curriculum reform in South Africa: The case for a flexible curriculum structure. Report of the Task Team on Undergraduate Curriculum Structure Discussion Document. Pretoria: CHE. [ Links ]

Curtis, D. & McKenzie, P. 2002. Employability skills for Australian industry: Literature review and framework development. Report to: Business Council of Australia; Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry. Melbourne: Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER). [ Links ]

Dall'Alba, G. & Barnacle, R. 2007. An ontological turn for higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 32(6) pp. 679-691. [ Links ]

Dearing, R. (1997). Report of the National Committee of Inquiry into Higher Education: Higher education in the learning society. London: HMSO. [ Links ]

Freudenberg, B., Brimble, M., Cameron, C., MacDonald, K.L. & English, D.M. 2013. I am what I am: am I? The development of self-efficacy through work integrated learning. International Journal of Pedagogy and Curriculum, 19(3), 177-193. [ Links ]

Griesel, H. & Parker, B. (2009). Graduate attributes: A baseline study on South African graduates from the perspective of employers. Pretoria: HESA; SAQA. [ Links ]

Hager, P. & Holland, S. (2006). Introduction. In P. Hager & S. Hollard (Eds), Graduate attributes, learning and employability (1-15). Dordrecht: Springer. [ Links ]

Harvey, L. (2003). Employability and diversity. Sheffield: Centre for Research and Evaluation, Sheffield Hallam University. [ Links ]

Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE). (2011). Opportunity, choice and excellence in higher education. Bristol: HEFCE. http://www.hefce.ac.uk/media/hefce/content/about/howweoperate/ corporateplanning/ strategystatement/HEFCEstrategystatement.pdf [13 February 2012]. [ Links ]

Hollis-Turner, S.L. (2008). Higher education business writing practices in office management curricula and in related workplaces. Unpublished MEd thesis, Cape Peninsula University of Technology, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Hollis-Turner, S.L. (2015a). Fostering the employability of business studies graduates. Journal of Education, 60, 145-166. ISSN 0259-479X. [ Links ]

Hollis-Turner S.L. (2015b). Educating for employability in office environments. Unpublished DEd thesis, Cape Peninsula University of Technology [ Links ]

Holten-Moller, N.L. & Vikkels0, S. (2012). The clinical work of secretaries: Exploring the intersection of administrative and clinical work in the diagnosing process. In J. Dugdale, C. Masclet, M.A. Grasso, J. Boujut, & P. Hassanaly (Eds), From research to practice in the design of cooperative systems: Results and open challenges (33-47). Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on the Design of Cooperative Systems, Marseille, France, 30 May-1 June 2012. London: Springer. [ Links ]

Howard, S. & Maton, K. (2011). Theorising knowledge practices: a missing piece of the educational technology puzzle. Research in Learning Technology, 19(3),191-206. [ Links ]

Jackson, N. (2011a). An imaginative lifewide curriculum. In N.J. Jackson (Ed.). Learning for a complex world: A lifewide concept of learning, education and personal development (100-121). Bloomington, IN.: AuthorHouse. [ Links ]

Jackson, N.( 2011b). The lifelong and lifewide dimensions of living, learning and developing. In N.J. Jackson (Ed.), Learning for a complex world: A lifewide concept of learning, education and personal development (121). Bloomington, IN.: AuthorHouse. [ Links ]

Kanter, R.M. (1977). Men and women of the corporation. New York: Basic Books. [ Links ]

Luckett, K. & Hunma, A. 2014. Making gazes explicit: Facilitating epistemic access in the Humanities, Higher Education Journal, 67, 183-198. [ Links ]

Lowden, K., Hall, S., Elliot, D. & Lewin, J. (2011). Employers' perceptions of the employability skills of new graduates. London: SCRE Centre, University of Glasgow; Edge Foundation. [ Links ]

Maree, K. (2007). First steps in research. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Maton, K. (2000). Languages of legitimation: the structuring significance for intellectual fields of strategic knowledge claims. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 21(2), 147-167. [ Links ]

Maton, K. (2014). Knowledge and knowers: Towards a realist sociology of education. Abingdon: Routledge. [ Links ]

Maton, K. & Muller, J. (2007). A sociology for the transmission of knowledges. In F. Christie & J.R. Martin (Eds), Language, knowledge and pedagogy: functional linguistics and sociological perspectives (14-33). London: Continuum. [ Links ]

Mayer, E. (1992). Key competencies: Report of the committee to advise the Australian Education Council and Ministers of Vocational Education, Employment and Training on employment-related competencies for post compulsory education and training. Canberra: Australian Education Council (AEC) and Ministers of Vocational Education, Employment and Training (MOVEET). September. http://hdl.voced.edu.au/10707/72980 [Accessed: 20 June 2014]. [ Links ]

Miller, J.L. (2010). Conducting business in a fast-paced world: the importance of change management. Student Pulse, 2(10). http://www.studentpulse.com/articles/299/2/conducting-business-in-a-fast-paced-world-the-importance-of-change-management [14 October 2014]. [ Links ]

Moore, R. & Maton, K. (2001). Founding the sociology of knowledge: Basil Bernstein, intellectual fields and the epistemic device. In A. Morais, I. Neves, B. Davies & H. Daniels (Eds), Towards a sociology of pedagogy: The contribution of Basil Bernstein to research (153-182). New York, Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Muller, J. (2009). Forms of knowledge and curriculum coherence. Journal of Education and Work, 22(3), 205-227. [ Links ]

Nel, H. & Neale-Shutte, M. (2013). Examining the evidence: Graduate employability at NMMU. South African Journal of Higher Education, 27(2),437-453. [ Links ]

Nkomo, M. (2000). The National Qualifications Framework and curriculum development. Pretoria: SAQA. [ Links ]

Oswick, C., Fleming, P. & Hanlon, G. (2011). From borrowing to blending: Rethinking the processes of organizational theory building. Academy of Management Review, 36(2), 318-337. [ Links ]

Pitman, T. & Broomhall, S. (2009). Australian universities, generic skills and lifelong learning. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 25(4), 439-458. [ Links ]

Powell, C. (2003). The Delphi technique: Myths and realities. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 41(4), 376-382. [ Links ]

Robbins Report, The. (1963). [Great Britain. Committee on Higher Education. Higher Education: Report of the Committee Appointed by the Prime Minister, under the Chairmanship of Lord Robbins, 1961-1963]. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. [ Links ]

Russon, M. (1983). How secretarial studies might evolve. Vocational Aspect of Education, 35(90), 31-36. [ Links ]

Shay, S. (2013). Conceptualizing curriculum differentiation in higher education: a sociology of knowledge point of view. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 34(4), 563-582. [ Links ]

Slonimsky, Y. & Shalem, L. (2006). Pedagogic responsiveness for academic depth. Journal of Education, 40(1), 37-58. [ Links ]

Solberg, J. (2014). Taking shorthand for literacy: Historicizing the literate activity of US women in the early twentieth-century office. Literacy in Composition Studies, 2(1), 1-28. http://licsjournal.org/OJS/index.php/LiCS/article/view/38/61 [4 Oct. 2014]. [ Links ]

South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA). (2000). The National Qualifications Framework and Curriculum Development. Pretoria: SAQA. [ Links ]

Stephenson, J. (1998). The concept of capability and its importance in higher education. In J. Stephenson & M. Yorke (Eds), Capability and quality in higher education (1-13). London: Kogan. [ Links ]

Teichler, U. (2009). Higher education and the world of work: Conceptual frameworks, comparative perspectives, empirical findings. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. [ Links ]

Truss, C., Alfes, K., Shantz, A. & Rosewarne, A. (2013). Still in the ghetto? Experiences of secretarial work in the 21st century. Gender, Work & Organization, 20(4), 349-363. [ Links ]

Walker, M. (2012). Universities, professional capabilities and contributions to the public good in South Africa. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 42(6), 819-838. [ Links ]

Waymark, M. (1997). The impact of national vocational qualifications on the secretarial curriculum. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 49(1), 107-120. [ Links ]

Wheelahan, L. (2009). The problem with CBT (and why constructivism makes things worse). Journal of Education and Work, 22(3), 227-242. [ Links ]

Wheelahan, L. (2010). Why knowledge matters in curriculum: a social realist argument. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Wheelahan, L. & Moodie, G. (2011). Rethinking skills in vocational education and training: From competencies to capabilities. New South Wales Government: Department of Education & Communities. http://www.bvet.nsw.gov.au/pdf/rethinking_skills.pdf [Accessed: 17 March 2014]. [ Links ]

Received 30 August 2016

Accepted 28 November 2017