Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of Education (University of KwaZulu-Natal)

On-line version ISSN 2520-9868

Print version ISSN 0259-479X

Journal of Education n.69 Durban 2017

RESEARCH ARTICLES

"Squeezed oranges?" Xhosa secondary school female teachers in township schools remember their learning about sexuality to reimagine their teaching sexuality education

Nomawonga MsutwanaI; Naydene de LangeII

IFaculty of Education Nelson Mandela University. nomawonga.msutwana@mandela.ac.za

IIFaculty of Education Nelson Mandela University. naydene.delange@mandela.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Several concurrent and complex issues seem to influence the teaching of sexuality education in South African schools. Studies have shown that teachers believe they can teach the subject as they have the content knowledge of sexuality education, but experience discomfort when they actually begin the task. We were therefore interested in understanding their perspectives on their own learning about sexuality within their Xhosa culture. Working with 9 purposively selected female Xhosa teachers from 4 secondary schools in townships in Port Elizabeth, we used participatory visual methodology, located within a critical paradigm, generating data with them through drawing. The data was analysed using thematic analysis. The findings show that the women teachers largely learnt about sexuality through piecing together the 'puzzle' of limited information from various quarters; through strict rules and fear; through own mistakes and through shame. This remembering facilitated ideas to rethink and reimagine sexuality education, drawing the value-laden Xhosa cultural teachings about sexuality into contemporary sexuality education. The participatory visual research process enabled a deep and open engagement, and in more than one way the claiming back of power, demonstrating a way to engage today's Xhosa adolescents on matters of sexuality.

Introduction

School is positioned as the logical site for clear, evidential, age-specific knowledge about sexuality and reproductive health (Francis, 2010; Goldman, 2012). In spite of schools offering sexuality education, a research review cited by Pound, Langford and Campbell (2016) acknowledges that for young people the present school sex and sexuality education is perceived to be negative, is based on heteronormativity, does not speak to adolescents' life-worlds and is taught by poorly trained, embarrassed teachers. Reality is that risky and sometimes violent sexual behaviour among adolescents does not seem to be abating in South Africa (Health, 2016; Stats SA, 2012). We therefore draw on Moletsane's argument that something different is required, a "reimagined sexuality education that utilises the contradictions and ambivalences of past and contemporary South Africa and that creatively looks ahead ... towards interventions that might address the actual needs of the target group" (Moletsane, 2011, p. 205). Similarly, Van Dyk (2001) suggests that Africa should look into her own past and bring in some of the ways it used to ensure safe (and healthy) sexuality. The supposition of researchers like Barr (2008) and Anderson and Beutel (2007), where the latter say that "HIV and AIDS education might be more successful if tailored to specific racial or ethnic groups" (p.143), encourages this study. Also, according to Eisner (1985) who refers to views of education scholars such as William Pinar, Max van Manen and Madeline Grumet, personal relevance in the school curriculum is essential. Structured opportunities for culturally relevant and scientifically accurate knowledge as a key part of HIV prevention and sexuality education can and should be provided at school (UNESCO, 2009; Wood, 2009a; Zuilkowski & Jukes, 2012). It shouldn't be biased knowledge, like that which the male teacher of one of the participants provided, when he said that girls are like squeezed oranges when they have had sex (and have lost their virginity) - they are useless and nobody would want them. It is therefore necessary that teachers who teach sexuality-related topics understand their own sexuality, how they learnt it, and how such knowledge could enable them to teach the adolescents in their classes in an authentic way. In this article the following question is therefore posed: What are Xhosa Life Orientation (LO), Life Sciences (LS) and Natural Sciences (NS) secondary school teachers' perspectives of learning about their own sexuality within their Xhosa culture?

Teaching sexuality education

Although the South African government formulated policies to be implemented by teachers to address HIV and AIDS through the related sexuality education, a policy/practice challenge continues to exist. A policy usually provides guidelines on a philosophical and content level, while teachers have to implement the fairly abstract guidelines on a practical level. For example, the Curriculum Assessment Policy Statements (Department of Basic Education, 2011a,b,c,d) for Life Orientation, Life Sciences and Natural Sciences provide guidelines for teachers to teach sexuality and sex education, yet studies show that teachers struggle to implement them (Ferreira & Ebersöhn, 2011). Harley, Barasa, Bertram, Mattson and Pillay (2000) hold that policy describes the work for the ideal teacher but does not take into account the real teacher and the cultural and material constraints imposed by classroom realities. As noted in the review of sexuality education studies by Pound et al. (2016), South African authors Helleve, Flisher, Onya, Mukoma and Klepp (2009), Macleod (2016) and McLaughlin, Swartz, Kiragu, Walli and Mohammed (2012) also attest to the fact that teachers find it difficult to take on the work of teaching some of the content knowledge of sexuality education. However, Glover and Macleod (2016) note that the teacher's confidence in teaching sexuality issues improves with experience in teaching the subject, with formal 'training', with the increase in openness on sexuality issues, and within an in-school 'nurtured' policy. Msila and Gumbo's (2016) claim that "whilst Africans cannot ignore the Western belief systems, Africans will be stronger if they start by describing their own environment, even for the formal 'Western' education" (p. iii), should be taken into consideration. This suggested undertaking requires what Darder, Baltodano and Torres (2009) term "... an emancipatory vision and practice of critical pedagogy" (p. 24). Critical pedagogy can be seen as a teaching and learning approach in which teachers and learners learn together by challenging existing dominant perceptions.

Placing this study within the African and South African context, we have identified a few of the many authors and researchers on sexuality, such as Becker (2007), Delius and Glaser (2002), Moletsane (2011; 2014) and Steyn and Van Zyl (2009), who all confirm a seeming silence in communicating about sexual matters in contemporary African cultures as opposed to precolonial times. This silence seems to be a justification for the lack of adults engaging appropriately with their children about sexual matters. This prohibition, acknowledged by DePalma and Francis (2014), about sex and sexuality in several South African cultures, makes both teachers and learners guarded and unable to engage authentically on issues of culture, sexuality and HIV and AIDS. Although the rules that govern sexual behaviour differ widely across and within cultures (UNESCO, 2009), all people are cultural beings in the sense that everyone is influenced by an infinite number of social forces that have shaped a person's mental outlook and perspectives on life (Tamale, 2008).

Mbananga's (2004) study of Xhosa high school teachers in Mthatha, for example, clearly points out that culture (as it is understood in contemporary Xhosa society), can contribute to tensions that surface when having to teach sexuality education due to intergenerational issues. According to Mbananga (2004, p. 153) the Xhosa teachers were "wearing masks" when it came to teaching adolescent learners about sexuality and reproduction. They took on a technical, moralistic and superficial stance when approaching the subject (Macleod, 2016). This implies that educators teach sexuality in the curriculum by prescribing to the learners how to behave, instead of engaging in a participatory manner with the learners. A question arises about how to present a curriculum regarding sexuality in a manner which will be enabling to teachers and learners alike. The recent media uproar about a grade 10 Life Orientation textbook, in which the rape of a girl is framed as being her fault, is a demonstration of how an uncritical text also perpetuates socio-stereotypical views on matters regarding sexuality (Health-E News, 2016). It is therefore necessary to explore how Xhosa culture - which is also the first author's culture - influences the manner in which curricula relating to sexuality is taught by female Xhosa teachers in the context of secondary schools in a township. The invitation to participate in the study was open to both male and female teachers, but only women were willing to join this journey, bringing an interesting focus.

In this article we first outline the theoretical lens which we used to make meaning of the findings, followed by an explaination of the methodology. We then offer the findings and the discussion thereof.

Theoretical framework

It is through a lens of critical theory (specifically its subsidiary feminist theory) that literature on sexuality education and its curriculum, and Xhosa cultural perspectives on the teachers' learning about sexuality are examined and the data analysed. Critical theory refers to both a school of thought and a process of critique; on the one hand it points to an essential body of thought of educational theorists and on the other it refers to a body of work that calls for the need to continually critique the world being studied against presented reality (Giroux, 2009). Giroux claims that critical theory posits that it is "in the contradictions of society that one could begin to develop forms of social inquiry that analysed the distinction between what is and what should be" (Giroux, 2009, p. 28). This critical orientation is a perspective that seeks to challenge conservative practices in the teaching and learning environment and to find alternative democratic pedagogies that can shift relations of power and voice (Darder et al., 2009). This is in line with the critical paradigm within which this study is located. Teachers are enabled to disrupt and transgress the hegemonic expectations of the curriculum; both the 'official' and 'enacted' curriculum. As Darder et al. (2009) postulate "... teachers learn to assess inequalities in their lives and question the notions of common sense that perpetuate our cultural, linguistic, economic, gendered and sexual subordination" (p. 23). Darder et al. (2009) point out that critical theory is criticised because it is said that it leaves unchallenged the unjust "structures of patriarchy in society and the sexual politics that obstruct the participation of women as full and equal contributing members of society" that it is supposed to disrupt (pp. 14-15). This critique motivated the use of another theoretical lens for this study; Feminist theory. Carlson and Ray (2011) posit that feminist theories are used to "explain how institutions operate with normative gendered assumptions and selectively reward or punish gendered practices" (n. p.). This basis makes feminist theory a 'just' abstract of critical theory to inform this study. Feminist theory in this study includes drawing on personal narratives (the women's cultural stories of learning about sexuality) and feminist remembering (Mitchell, 2012, p.1), and a rethinking of authority (reclaiming women's power to reimagine the curriculum), within the historical and political context of women as knowing subjects (having insider cultural knowledge to be used in rethinking the teaching of sexuality education underpinned by their Xhosa culture).

Research design and methodology

We chose to use a qualitative design within the critical paradigm, employing participatory visual methodology to explore the participants' life worlds (understanding their reality) - the female Xhosa teachers teaching sexuality education in Port Elizabeth's township secondary schools. We also wanted the research process to enable the participant teachers to consider how they could transform how things are, following the critical paradigm (Taylor, 2013). Participatory visual methodology was used as it enables a process of reflection and action by the participants (Cornwall & Jewkes, 2010).

Participants

The teachers were purposively selected from four secondary schools in townships in Port Elizabeth. We conveniently selected the four schools whose management team was welcoming the invitation to be part of the research. The invitation was open to all teachers, male and female, who teach either Life Orientation, Life Sciences or Natural Sciences. Only nine female teachers volunteered. They were all Xhosa women, between the ages 42 and 55 and all were qualified to teach their subject.

Data generation method - Drawing

Drawing is a relatively simple and inexpensive method that can be a highly participatory and a potentially powerful force for policy and social change (De Lange, Mitchell & Stuart, 2011), and was used to explore how the teachers themselves learnt about sexuality when they were growing up. They responded to the following prompt:

"Draw how you learnt about your sexuality when you were growing up. The quality of your picture is not important. Write a brief explanation of your drawing."

The teachers were given 15 minutes to make a drawing - using pen and a sheet of A4 paper - and write a caption. They then explained their drawings to the others in the group. This served as the first layer of analysis. The drawings, captions and their explanations were analysed using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). A code-recode procedure was used and we held a consensus discussion with the supervisor. I, the first author, acknowledge that I came into this study with an emic perspective of the phenomenon under study in that I, a Xhosa woman, had been a Life Orientation teacher in secondary schools in townships within the Nelson Mandela Metropole. However, drawings and direct quotations are used to carefully represent the participants' voice, respecting their viewpoints and ensuring integrity of the data.

There was adherence to quality standards of trustworthiness and authenticity (Guba, 1981). Authenticity was ensured as we did not impose our own views when participants reflected on their own learning about sexuality, but listened attentively. In terms of ethics, ethical clearance was gained from the university, and informed consent was sought before partcipants embarked on this research journey. Due to the sensitive nature of the phenomenon under study, the first author arranged with the university's psychological support services to make themselves available to any participants who needed them. We adopted the philosophy of equal researcher-participant relations. The participants agreed that all their data (visual and verbal), may be shared.

Findings

Four themes were developed from the data, i.e., the Xhosa women learnt about sexuality through piecing together limited information from various sources; through the strict rules made by the parents and teachers and which instilled fear; through learning the hard way from own mistakes; and through the lens of shame. We present each theme by beginning with a brief conceptualisation of the theme, then provide a relevant drawing that best explains the theme, which is followed by direct quotations and meaning-making of the theme.

Theme one: Learning through piecing the 'puzzle' together

The Xhosa women felt they were not provided with either appropriate or adequate guidance where sexuality was concerned in spite of gaining knowledge from different avenues. The following are some of the many avenues from which they made meaning of sexuality; i.e. from the little talk about sexuality at home and from whoever was parenting them, from those in their friend zone, from some concerned teachers at school, from those at church, and also the media. It seemed that they had to piece the puzzle together on their own about sex and about expressing sexuality.

A Natural Science teacher made the following drawing showing how her learning about sexuality was piecemeal, coming from the home, school, church and friends.

Although some Xhosa women indicated that they had some talk at home, it was limited to selected aspects of sexuality, largely menstruation, and then in a very superficial way, leaving the relationship between menstruation and pregnancy unattended to. Another teacher explained as follows:

"In this picture there is me, there's home, there's community, there's school. And then, what I've learnt from home, what I was taught at home: there was not much information that I would get. I was just told when I started menstruating; 'You see now. . . because you are menstruating, should you have a boyfriend, you are going to fall pregnant.' That's the only thing I was told."

Some of the Xhosa women were not raised by their parents, as the parent or parents were either working in the big city, deceased or had deliberately walked out on the family.

"I grew up in a family where my father was working in Johannesburg and I stayed with my mother at home and my father used to come back during the Easters and December, so I saw him twice a year'"

"I grew up with my grandfather, my mother was not there. . . ."

"I grew with my mother's friend in Transkei, then moved to my father's wife, to my uncle. So was moving up and down."

So the substitute parent, relative or guardian, in the absence of a parent, might have offered bits of sexuality-related information or not.

Like any adolescent these Xhosa women also remembered how they wanted to hang out with their friends, but they were Xhosa and growing up in a Xhosa community and had lots of chores to do or had to stay inside the yard.

"In our community there were many girls that go out as friends but I remember when now we were not allowed to go out like go to films and everything that we would sit in the yard behind the closed gate. . . ."

They however had enough time with friends at school where they talked about things adolescents are curious about, also about sex and sexuality. The participants learnt about sexuality from the stories of their friends, some of the learned information was correct, some inaccurate and but altogether left some gaps.

"And then at school, the bigger girls that were with us in class, they would talk about stuff, in class and in break. And they would say 'Share your story your story, don't just listen to us, what's happening in your own life, don't just listen and say nothing'. And from that information also I know that some of the stuff that was shared was not correct. So there is some correct stuff that I've learnt. But there was also a lot of gaps from the information that I got."

Not all the Xhosa women learnt about sexuality in school, as sexuality was not in the curriculum, but some of their teachers took it upon themselves to guide the girls where sexuality was concerned. Because of that some of the participants preferred school over home.

"So she took me to a boarding school and I think that's where I got a lot of information from my Consumer Studies teacher. She used to tell us about how to behave as a girl and decision making and she introduced us into this menstruation stuff, to me school was better than home, home it was like a prison.. . ."

The Christian church played a big role in the lives of these Xhosa women, and in one instance they pointed to how space was provided for girls - within the church structures - to talk about sexuality and about being a woman. In the church they also saw that women and girls and men and boys sat separately, as if to support the idea of difference between the sexes, and also to keep them apart. In some instances the church prescribed how adolescents (and others) should behave.

"I think church played a big role in my life and there are those sessions for girls ministry whereby we talk as girls and the visions that we have how many children that we want to have, you want to keep your virginity and you just have a picture when you get married, how is it going to be sleeping for the first time. . .. "

There was also learning about sexuality from the media when these women were growing up. One Xhosa woman referred to watching a television programme where the male character was kissing a woman, although she learnt from it, she pointed out that that was Westernized behaviour. This statement might imply that there was an African (or Xhosa) way of enacting sexuality.

"I would say more on sexuality level, the influence was through the media. I remember at my mother's work while I am sitting with my mother's boss, watching Knight rider and in it this particular lady in the film, there would be a romantic part and when they are kissing you go like this, so it is not so much of an influence from outside because I grew up in a more westernized society."

The piecemeal knowledge seemed to leave the participants unequipped to express their sexuality in a relationship, and so did not know how to deal with conflicting feelings, or that such feelings were normal.

". . . but this boyfriend of mine expected me to say yes I love you, but those words couldn't come out of my mouth I couldn't say them, I was shy but inside. . .."

Theme two: Learning through strict rules and fear

The Xhosa women teachers talked about how their upbringing was characterised by prescriptive and restrictive rules, in the home and at school. According to them a Xhosa home run and conducted according to strict rules had prestige in the community. Breaking the rules (by having sex and becoming pregnant) would ruin the family prestige and so fear was instilled to ensure that the girls police their own behaviour under the surveillance of the family and community. A Life Sciences teacher made the following drawing of herself and her boyfriend going to the bioscope, with some friends in couples surrounding them, depicting how she did not know how to express her love and how she was afraid to do so.

The strictness of their Xhosa mothers at home is seen in what they permitted the children to do and not to do. For example, the children were not allowed to play outside the yard lest they do something that is not right and get into trouble:

"My mother was very strict it was even difficult to go and play with other children so I was always at home if it's not home its church, if it's not church I am in town with her."

In the Xhosa home, there was restricted movement for the growing children put in place by the parents which, in some cases, caused the children's humiliation.

"In our community there were many girls that go out as friends but I remember when now we were not allowed to go out like go to films and everything that we would sit in the yard behind the closed gates and I remember those that were passing by in a space (we call it a square), we would say it's a gap, so everybody would laugh at us and say 'hey, they are dogs of the yard'...."

Sometimes it was an instruction that evoked the fear. In a Xhosa home there was less dialogue and the common thing to do was to be commanding when dealing with sexuality matters.

"Should you have a boyfriend, you are going to fall pregnant".

At other times the fear was so real that it affected the growing young woman's life. Being brought up by a guardian meant that the child had to think twice about things that would affect the dynamics in the household.

"It was my aunt who played the role of being a mother to me because my mother passed on when I was only 8 years old. . . . So she was the one who showed me, 'You see, what will happen, when you get pregnant, I will not take care of your child because I am taking care of you. ' So I was so afraid to get pregnant in a very big way. I was really afraid because I thought; 'What will happen to the child'. As a result, I got children when I was very old. My first child, I think I was about going to my 30s I think".

A teacher, in trying to talk about sexuality, used the analogy of a "squeezed orange" (see Figure 2) which managed to evoke some fear in the young women learners. The teacher said that once squeezed the orange becomes useless, so a girl having sex with a boy loses her value.

". . .there was a teacher by the name of Mr Z. He used to tell us that 'You girls must know that you are like an orange. You see the orange. . .. You don't open an orange and cut it, you squeeze the orange, and you take that juice, if you have boyfriends you will be like that orange. Once that juice is taken out of that orange, nobody wants that orange'. So at the end of the day I told myself that, no ways I can't be like that orange and be thrown away and not be wanted by anyone. So we had those fears of not being those oranges and be squeezed."

It is a worrying analogy in that besides negatively focusing on only the girl, it takes away from sex as a pleasurable act between consenting individuals.

Theme three: Learning the hard way

Some Xhosa women learnt about sexuality from being confronted with having to act or make a decision regarding sexuality. The Xhosa girls were not enabled to be proactive with regard to their sexuality, they were living the submissiveness that they were expected to in contemporary Xhosa culture, and hence found themselves to have kissed and have had sex without planning nor contemplating it.

A Life Orientation teacher made the following drawing of herself as a free spirit in learning about sexuality since she grew up as an only child to a travelling single mother.

"I learnt about sexuality when Ifirst developed feelings, emotions and I remember on this one Friday I met Polo, there was a time I grew up in Limpopo and Polo proposed to me and I said yes, the chemistry was so strong it was 30 minutes of hugging and kissing just so tight but thanks God that nothing happened."

A Xhosa girl learnt from her own negative experience from being coerced into sex. At another time she was with a boyfriend and was 'persuaded' or forced to have sex.

"And then I met this guy I think I was probably 19, it was my first time to have sex. I would like to say this that being girl meeting someone you don't need them with the intention to have sex, you just don't know what is going to happen when they invite you over, you go over to their place as a friend as a girlfriend not knowing that they are gonna say you can come into my room, and from there they say (kaloku)... then you move from one corner of the bed to the other trying to avoid this up until it happens and you realize only later but that was not my will, and I never said yes."

Theme four: Learning through shame

Everyone in the Xhosa community was expected to rebuke youths engaging in sex as it was not embraced and was seen as shameful. Any deviance from the rules at home and in the community was treated harshly, shaming the girl who became pregnant, stripping her of dignity as she would not be given voice. For instance, she would be compelled to let her child grow up as if he or she was her parents' child and sometimes not be allowed to tell her child who the biological parents were.

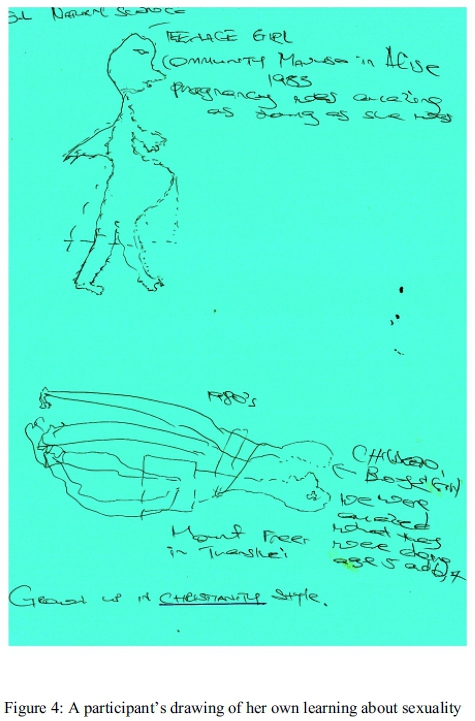

A Natural Sciences teacher made the following drawing of a pregnant teen and two children having sex in depicting how she learnt about sexuality.

Sex was referred to as 'something dirty' (izinto ezimdaka) which is an indication that sex was not viewed positively nor embraced. It was the same with teen pregnancy, it brought great shame to the girl as well as her family. This is not uncommon in Xhosa culture where intimacy and sex are treated as very private things.

" . . . in our culture . . . sex is 'izinto ezimdaka' translated in English as 'something that is very dirty' and that is what we call it in our culture, and we were raised to call it like that because we take it from our parents even if the small boy sees the others doing sex they will run and say mother those two are doing something dirty; sex is referred to as something that is dirty."

" I grew up without knowing my father because it was a shameful thing [for my mother] to get pregnant while you are not married. It would not be talked about in the family, and when you ask your mother who your father is, she won't tell you, she will go into the grave without telling you. It will be a secret in the family."

The four themes collectively shed light on what these Xhosa women teachers remembered about their own learning about sexuality during their adolescent years. We draw on the themes to tease out what their remembering might mean in terms of their reimagining teaching sexuality education to the adolescents in their classes.

Discussion

Although sexuality education was not part of the school curriculum when the participants grew up, they did learn about sexuality from different sources, often leaving them with inadequate knowledge on how to avoid risk and how to express healthy sexuality. Sexuality education, as we know it today in South Africa, came with the Revised National Curriculum Statement (RNCS) (Ramrathan, 2015) requiring teachers to engage with the curriculum and teach it to the children in their classes. We pointed out that most teachers struggle to teach sexuality education and so following Moletsane (2011) we tried to explore whether enabling the Xhosa women teachers to draw on their own personal and cultural knowledge of learning about sexuality might yield some insights into how they might reimagine teaching sexuality education to the Xhosa adolescents currently in their classes. Although we used a participatory method such as drawing which enabled a deep engagement with and reflection on the topic, and while the Xhosa women thought critically about their own learning about sexuality, we did not seem to get to a specific culturally informed and culturally sensitive way of teaching sexuality education for the target group, i.e. modern day Xhosa adolescents in secondary schools in townships.

Considering the socio-historical context of South Africa, black African people's beliefs about sexuality have been contoured by colonisation and its western thought, Christianity, apartheid and its philosophy of separate development, and urbanisation, diluting the strengths of indigenous cultures. This left indigenous people, in this instance, Xhosa people, having to contend with tensions and contradictions, and the loss of openness with which sexuality was handled (Delius & Glaser, 2002; 2004; Dickinson, 2014; Mudhovozi, Ramarumo & Sodi, 2012). It was thus not strange to find that there was limited talk about sexuality when these Xhosa women were adolescents, as contemporary (Xhosa) culture still makes it difficult to talk about such matters (Delius & Glaser, 2002; Wood, 2009b). In the Xhosa culture difference in age between an adolescent and an adult places restrictions on what could be said to the adolescent who needs to be taught about sexuality, limiting the discussion of sexuality. As such the notion of intergenerationality (Hunting, 2012; Moolman, 2013) explains such limited talk about sexuality.

Culture, drawing on patriarchy, also influences the behaviour of boys and men and girls and women worldwide, also the Xhosa people (Chabaya, Rembe, Wadesango & Mafanya, 2009). The Xhosa adolescents should thus have learnt about their roles and about sexuality at home and at initiation schools. Delius and Glaser (2002), however, point out that initiation schools had begun disintegrating also because black Africans began embracing city life. There was no direct substitute for the teaching done at the initiation schools, leaving the adolescents on their own to figure out how to express their sexuality.

Sexuality, in most cultures, also the Xhosa culture, is considered to be an area for adults only and from which children, who are seen to be innocent, need to be protected (Beyers, 2013; Robinson & Davies, 2008). Strict rules and instilling fear regarding sexuality is then a way to try to keep them from engaging in sex. Parents and teachers alike often take a technical and moralistic stance when addressing sexuality matters (Macleod, 2016) avoiding engaging with the matter in an appropriate way. Xhosa adolescents might have accepted the directives and restrictions from the parents rather than dare be disrespectful. This respect for older people is called ukuhlonipha in isiXhosa (Mkhwanazi, 2014). Adherence to the ideals of ukuhlonipha is alleged to be one of the causes behind girls falling pregnant in townships (Mkhwanazi, 2014) and women and girls being at the receiving end of sexual violence in the form of unwanted or coerced sex (Schefer, 2010). The women teachers talked of a time before theirs in Xhosa culture, around the 1940s and 1950s, and of the teachings regarding sexuality which were focused on values such as respect for self. They appraised that such value was useful then, and could still be useful in teaching today's adolescents too.

Traditional Xhosa culture also requires, along with Christian religious values, that girls remain pure until marriage. Breaking this through having sex is frowned upon as sex outside of marriage is regarded as izinto ezimdaka (something dirty). This is a way of policing of girls and women expressing their sexuality, leaving boys and men to do as they please. In this instance too, Xhosa culture and patriarchy contribute to such a state of affairs (Gqola, 2007; Msibi, 2009), with women feeling disempowered to stand up and negotiate relationships and sex.

In doing the research with the Xhosa women teachers, enabling them to remember and reflect on how they learnt about their sexuality, created a space for them to think about what they as Xhosa women teachers could draw on to make their teaching of sexuality education authentic so that the adolescents don't have to piece together the puzzle of sexuality, which might leave them with an incomplete (and dangerous) understanding of sexuality.

Conclusion

Drawing on the findings and discussion, and having exposed the Xhosa women teachers to a participatory visual methodology, we extrapolate what this might mean for reimagining teaching of sexuality education to Xhosa adolescents in township secondary schools.

We showed how personal narratives about learning about sexuality can enable an open discussion on sexuality, where all learn from each other, perhaps fulfilling the claim that Mitchell (2012) makes, that memory-work shifts teacher perceptions and practices. A critical pedagogy founded on the principle of dialogue, can only be enacted in interactive classroom spaces, where teachers and learners together can reflect, critique, and act upon their world (Darder et al., 2009). The pedagogy facilitates a democratic teaching and learning space which helps ease the tensions that usually surface in a teacher-centered instruction on sexuality. If the teachers are closer to understanding what it takes to teach sexuality differently, to listen to the learners, to learn together, the Xhosa women teachers would have claimed back their power to speak about sexuality, drawing the value-laden Xhosa cultural teachings about sexuality - through open dialogue - into contemporary sexuality education. It is necessary that innovative work on the self be done with teachers, in particular those who teach sexuality education, so that they can establish their own positionality in terms of their culture, their beliefs, and how these inform what and how they will teach sexuality education. As the female teachers got to remember and reflect on their own histories, they could also work in a similar way with the learners, thereby reimagining the sexuality education curriculum and its pedagogy, and shifting it to what it might be.

References

Anderson, K. G., & Beutel, A. M. (2007). HIV and AIDS prevention knowledge among youth in Cape Town, South Africa. Journal of Social Sciences, 3(3), 143-151. [ Links ]

Barr, B. K. (2008). The culture of AIDS in Xhosa society. University of Tennessee, Knoxville: Trace. [ Links ]

Becker, H. (2007). Making tradition: A historical perspective on gender in Namibia. In S. LaFont & D. Hubbard (Eds), Unravelling taboos: Gender and sexuality in Namibia (pp. 22-38). Windhoek: Gender Research & Advocacy Project/ Legal Assistance Centre. [ Links ]

Beyers, C. (2013). In search of healthy sexuality: The gap between what youth want and what teachers think they need. The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa, 9(3), 550-560. [ Links ]

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. [ Links ]

Carlson, J. & Ray, R. (2011). Feminist theory. Retrieved on October 7, 2016, from www.oxfordbibliographies.com DOI: 10.1093/OBO/9780199756384-0020

Chabaya, O., Rembe, S., Wadesango, N., & Mafanya, Z. (2009). Factors that inhibit implementation of policies on gender-based violence in schools: A case study of two districts in Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Agenda: Empowering women for gender equity, 80, 97-108. [ Links ]

Cornwall, A., & Jewkes, R. (2010). What is participatory research? Social Science & Medicine, 70(5), 794. [ Links ]

Darder, A., Baltodano, M. P., & Torres, R. D. (Eds). (2009). The critical pedagogy reader (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

De Lange, N., Mitchell, C., & Stuart, J. (2011). Learning together: Teachers and community healthcare workers draw each other. In L. Theron, C. Mitchell, A. Smith & J. Stuart (Eds), Picturing research: Drawings as visual methodology (pp.177-189). Rotterdam: Sense. [ Links ]

Delius, P., & Glaser, C. (2002). Sexual socialisation in South Africa: A historical perspective. African Studies, 61(1), 27-54. [ Links ]

Delius, P., & Glaser, C. (2004). The myths of polygamy: A history of extra-marital and multi-partnership sex in South Africa. South African Historical Journal, 50, 84-114. [ Links ]

DePalma, R., & Francis, D. (2014). Silence, nostalgia, violence, poverty . . .: What does 'culture' mean for South African sexuality educators? Culture, Health & Sexuality: An International Journal for Research, Intervention and Care, 16(5), 547-561. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education. (2011a). Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement for Life Orientation Grades 7-9. Retrieved on October 12, 2014, from http://www.wsparrow.co.za/AIDS/images/Documents/GRADES_7-9_LIFE_ORIENTATION_CAPS.pdf

Department of Basic Education. (2011b). Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement for Life Orientation Grades 10-12. Retrieved on July 29, 2014, from http://www.education.gov.za/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=aovsPAsVZao%3D&tabid=570&mid=1558

Department of Basic Education. (2011c). Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement for Life Sciences Grades 10-12. Retrieved on July 30, 2014, from http://www.education.gov.za/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=RsiGaHNRRNA%3d&tabid=420&mid=1216

Department of Basic Education. (2011d). Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement: Natural Sciences - Senior Phase. Retrieved on January 12, 2016, from http://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/CD/National%20Curriculum%20Statements%20and%20Vocational/CAPS%20SP%20%20NATURAL%20SCIENCES%20GR%207-9%20%20WEB.pdf?ver=2015-01-27-160159-297

Dickinson, D. (2014). A different kind of AIDS: Folk and lay theories in South African townships. Auckland Park: Fanele. [ Links ]

Eisner, E. (1985). Five basic orientations to the curriculum. In E. Eisner, The educational imagination: On the design and evaluation of school programs (2nd ed.) (pp. 61-86). New York: Macmillan Publishing Co. [ Links ]

Ferreira, R., & Ebersöhn, L. (2011). Formative evaluation of the STAR intervention: Improving teacher's ability to provide psychosocial support for vulnerable individuals in the school community. African Journal of AIDS Research, 10(1), 63-72. [ Links ]

Francis, D. A. (2010). Sexuality education in South Africa: Three essential questions. International Journal of Educational Development, 30, 314-319. [ Links ]

Giroux, H. A. (2009). Critical theory and educational practice. In A. Darder, M. P. Baltodano & R. D. Torres (Eds), The critical pedagogy reader (2nd ed.) (pp. 27-51). New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Glover, J., & Macleod, C. (2016). Rolling out comprehensive sexuality education in South Africa: An overview of research conducted on Life Orientation sexuality education. Unpublished policy brief document, Critical Studies in Sexualities and Reproduction. Rhodes University, Grahamstown. [ Links ]

Goldman, J. D. G. (2012). A critical analysis of UNESCO's International Technical Guidance on school-based education for puberty and sexuality. Sex Education, 12(2), 199-218. [ Links ]

Gqola, P. D. (2007). How the 'cult of femininity' and violent masculinities support endemic gender based violence in contemporary South Africa. African Identities, 5(1), 111-124. [ Links ]

Guba, E. G. (1981). Criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of naturalistic inquiries. Educational Resources Information Center Annual Review Paper, 29, 75-91. [ Links ]

Harley, K., Barasa, F., Bertram, C., Mattson, E., & Pillay, S. (2000). "The real and the ideal": Teacher roles and competences in South African policy and practice. International Journal of Educational Development, 20, 287-304. [ Links ]

Health. (May 17, 2016). Rape and Facebook make tense headlines in South Africa this Spring. Retrieved on October 01, 2016, from www.npr.org

Health-E News (August 2, 2016). Rape example in text book shows systemic flaws. Retrieved on August 4, 2016, from http://www.dailymaverick.co.za/section/south-africa/

Helleve, A., Flisher, A. J., Onya, H., Mukoma, W., & Klepp, K. (2009). South African teachers' reflections on the impact of culture on their teaching of sexuality and HIV/AIDS. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 11(2), 189-204. [ Links ]

Hunting, B. (2012). This thing called the future: Intergenerationality and HIV and AIDS. Educational Research for Social Change (ERSC), 1(2), 84-93. [ Links ]

Macleod, C. (2016). Why sexuality education in schools needs a major overhaul. Retrieved on June 17, 2016, from http://theconversationafrica.cmail19.com/t/r-l-stjddtt-iutiotka-u/

Mbananga, N. (2004). Cultural clashes in reproductive health information in schools. Health Education, 104(3), 152-162. [ Links ]

McLaughlin, C., Swartz, S., Kiragu, S., Walli, S., & Mohammed, M. (2012). Old enough to know: Consulting pupils about sex and AIDS education in Africa. Cape Town: HSRC Press. [ Links ]

Mitchell, C. (December 6, 2012). Feminist remembering: Productive remembering in changing times. The 21st Century woman: New opportunities and new challenges, Gorbachev Foundation. Retrieved on June 26, 2017, from http://www.gorby.ru/userfiles/gorbachev_women_dec6_1_.pdf

Mkhwanazi, N. (2014). "An African way of doing things": Reproducing gender and generation. Anthropology Southern Africa, 37(1&2), 107-118. [ Links ]

Moletsane, R. (2011). Culture, Nostalgia, and Sexuality Education in the Age of AIDS in South Africa. In C. Mitchell, T. Strong-Wilson, K. Pithouse & S. Allnutt (Eds). Memory and pedagogy (pp.193-208). New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Moletsane, R. (2014). Nostalgia: AIDS Review 2013. University of Pretoria: Centre for the study of AIDS.

Moolman, B. (2013). Rethinking 'masculinities in transition' in South Africa considering the 'intersectionality' of race, class, and sexuality with gender. African Identities, 11(1), 93-105. [ Links ]

Msibi, T. (2009). Not crossing the line: Masculinities and homophobic violence in South Africa. Agenda, 80, 50-54. [ Links ]

Msila, V., & Gumbo, M. T. (Eds). (2016). Africanising the curriculum: Indigenous perspectives and theories. Bloemfontein: SUN PRESS. [ Links ]

Mudhovozi, P., Ramarumo, M., & Sodi, T. (2012). Adolescent sexuality and culture: South African mothers' perspective. African Sociological Review, 16(2), 119-138. [ Links ]

Pound, P., Langford, R., & Campbell, R. (September 21, 2016). Sex education to blush over - international study. Medical Brief: Africa's Medical Media Digest. University of Bristol. Retrieved on September 22, 2016, from http://www.medicalbrief.co.za/archives/sex-education-blush-international-study/

Ramrathan, L. (2015, January 19). SA's school journey. Daily News. Retrieved on July 20, 2015, from http://www.iol.co.za/dailynews/opinion/sa-s-school-journey-1.1806392#Vazlwk0aLVI

Robinson, K. H., & Davies, C. (2008). 'She's kickin' ass, that's what she's doing!' Australian Feminist Studies, 23(57), 343-358. [ Links ]

Shefer, T. (2010). Narrating gender and sex through apartheid divides. South African Journal of Psychology, 40(4), 382-395. [ Links ]

Statistics South Africa. (2012). Retrieved on September 10, 2014, from http://www.stassa.gov.za/publications/SAStatistics/SAStatistics2012.pdf

Steyn, M., & Van Zyl, M. (Eds). (2009). The prize and the price: Shaping sexualities in South Africa. Cape Town: HSRC Press. [ Links ]

Tamale, S. (2008). The right to culture and the culture of rights: A critical perspective on women's sexual rights in Africa. Feminist Legal Studies, 16(1), 47-69. [ Links ]

Taylor, P. C. (2013). Research as transformative learning for meaning-centred professional development. In O. Kovbasyuk & P. Blessinger (Eds), Meaning-centred education: International perspectives and explorations in higher education (pp. 168-185). New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

UNESCO. (2009). International guidelines on sexuality education: An evidence informed approach to effective sex, relationships and HIV/STI education. Draft document. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation. [ Links ]

Van Dyk, A. C. (2001). Traditional African beliefs and customs: Implications for AIDS education and prevention in Africa. The South African Journal of Psychology, 31(2), 60-66. [ Links ]

Wood, L. A. (2009a). 'Not only a teacher, but an ambassador': Facilitating HIV/AIDS educators to take action. African Journal of AIDS Research, 8(1), 83-92. [ Links ]

Wood, L. (2009b). Teaching in the age of AIDS: Exploring the challenges facing Eastern Cape teachers. Journal of Education, 47, 127-149. [ Links ]

Zuilkowski, S. S., & Jukes, M. C. H. (2012). The impact of education on sexual behaviour in sub-Saharan Africa: A review of the evidence. AIDS Care, 24(5), 562-576. [ Links ]

Received 13 February 2017

Accepted 10 July 2017