Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of Education (University of KwaZulu-Natal)

On-line version ISSN 2520-9868

Print version ISSN 0259-479X

Journal of Education n.69 Durban 2017

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Reconfiguring educational relationality in education: the educator as pregnant stingray

Karin Murris

Professor of Pedagogy and Philosophy. School of Education. University of Cape Town. karin.murris@uct.ac.za

ABSTRACT

In my paper, I discuss student, teacher-centred and 'post-postmodern' educational relationality and use Karen Barad's posthuman methodology of diffraction to produce an intra-active relationality by reading three familiar figurations through one another: the midwife, the stingray, and the pregnant body. The new educational theory and practice that is produced is the 'superposition' of the pregnant stingray - a reconfiguration of the educator that disrupts power producing binaries, such as teacher/learner, adult/child, individual/society. The reconfiguration of the pregnant stingray makes us think differently about difference, the knowing subject (as in/determinate and unbounded), and creates a more egalitarian intra-relationality 'between' learner and educator through the shift in subjectivity.

Student centred or teacher centred education?

Educators are trained to regard schools as places of learning for human development and achievement. For example, philosopher of education Gert Biesta argues that education works in three domains and has three concurrent, overlapping purposes or aims (Biesta, 2010, 2014). Education, he argues, should concern itself not only with schooling or qualification, but also with socialisation and what he calls 'subjectification'. Educational institutions need to ensure that students are qualified, that they are equipped with the right kind of knowledge, skills and dispositions ('qualification'). The emphasis on qualification is orientated around cognitive and linguistic capabilities, measured through observations by the teacher and through standardised testing administered by the adult knowledge expert. Educators also need to ensure that 'newcomers' to the world are familiarised with the values and traditions that enable learners to become part of existing social practices ('socialisation') (Biesta, 2014). Children learn to excel through the acquisition of knowledge, skills and dispositions with the main purpose of integration within human society as it is (Snaza, Applebaum, Bayne, Carlson, Rotas, Sandlin, Wallin and Weaver, 2014). Educationalists differ in their opinions about whether education should include more than these two, but, drawing on Levinas, Biesta enriches this debate by offering an important third aim, 'subjectification', which relates to how education impacts on the person. Although each aim of education is legitimate, Biesta does prioritise them, and he regards the third, 'subjectification' as fundamental for education. It is on this basis that questions about knowledge, skills and dispositions, competence and evidence can be asked. For Biesta, the aim of education should not be a mere focusing on the acquisition of knowledge, or a process of socialisation into an existing order, but to speak with one's own voice and to bring something new into the world. For Biesta, subjectification is not an outcome, or a thing to be produced, an essence or identity, but an event. Educational action is not guided by what a student might become; as educators we should show "an interest in that which announces itself as a new beginning, as newness, as natality, to use Arendt's term" (Biesta, 2014, p.143). Teaching is not a quality or something a person possesses; it emerges only in an encounter with the other, because a teacher can never control the "impact" her activities have on her students (Biesta, 2014, pp.54, 56).1 The teacher's role, for Biesta,2 is that of a person who mediates in any concrete moment between child and curriculum when making practical judgements.3 But, as Biesta (2014, p.142) insists, such education should not be in terms of "a truth about what the child is and what the child must become".

Biesta's relational subjectivity mapped out earlier involves surrendering the idea that individual subjectivity is pre-social. As he explains, teaching and learning is not a:

. . .one-way process in which culture is transferred from one (already acculturated) organism to another (not yet acculturated) organism, but as a co-constructive process, a process in which both participating organisms play an active role and in which meaning is not transferred but produced. (Biesta, 1994, p.311-312; my emphasis).

In other words, meaning is the result of co-constructive processes between two or more organisms. Production of meaning is not a 'one-way process'. Both human subjects (teacher and learner) "constitute the meaning of what is learned" (Biesta, 1994, p.315) - a subject is an existential event, not an identity or essence (Biesta, 2014, p.143). Therefore, education should not start from ideas about what children (or students) should become (according to the educator), but "by articulating an interest in that which announces itself as a new beginning" (Biesta, 2014, p.143). 'Coming into the world' cannot be done in isolation, and meaning can be co-produced only when students are treated as a subject.

The advantage of Biesta's articulation of subjectification as the third (and most salient) aim of education is that it shifts the typical teacher-centred versus student-centred polemic debate into a different direction with its focus on collaborative co-production of knowledge by teacher and learner with "bothparticipating organisms" (see above citation) playing an active role in meaning-making. This 'post-postmodern' philosophical shift renders the student/teacher binary redundant and offers a justification for the kind of emancipatory, critical and democratic (teacher) education in which there can be epistemic equality (Murris and Verbeek, 2014). There is an important difference between Biesta's philosophy of education and a student-centred approach to teaching and learning. He is well-known for his critique of the current focus in education on learning rather than teaching - a dangerous shift in educational discourse and practices, he calls 'learnification' (Biesta, 2010, 2014). This global tendency to talk about 'learning' (see e.g. 'lifelong learning'), rather than 'education', has meant a moving away from concerns about what content is taught to concerns about process (skills and competences). Biesta agrees with the critique levelled at traditional teaching with its authoritarian conception of teaching as control. He argues that the learner does not exist as a subject in her own right, but merely as an object of the interventions of the teacher. However, (without setting up a binary between teaching and learning) he is equally critical of student-centred teaching that positions the teacher as a facilitator of learning (Biesta, 2016). Teaching, he claims, is always about content, that is, about something for particular purposes and is always relational because it involves someone educating somebody else (Biesta, 2012, p.12; my emphasis). His main point is that learnification hides the importance of content, purpose and the 'who' or the subjectivity of the teacher in the educational relationship (Biesta, 2006, 2010, 2012).

As an individualistic concept, learnification shifts the attention away from relationships (Biesta, 2014). Student-centered education puts the individual, the student, at the centre of pedagogy in terms of planning by foregrounding their interests, backgrounds, needs and goals. In student-centered education, the development of educational relationships relies on dialogical and sociocultural pedagogies, mentoring, formative assessment, (self-) reflection, reflexivity and relational and interactive strategies such as peer and small group work (Ceder, 2016, p.16). With the emphasis on knowledge and the important role of the teacher, one might mistakenly believe that Biesta is proposing a teacher-centred approach. In the latter, the teacher is an authority of knowledge production, and consequently positions the learner as knowledge consumer. Therefore, the relationship between teacher and learner is that of epistemic inequality (Murris, 2013). The recent emphasis on evidence-based research, student performance, national and international assessments, yearly exams and tests and homework at increasingly earlier ages positions the teacher as the authority. But Biesta is highly critical of the politics of the lingo of the educational measurement culture and, as we have seen through the discussion of his work above, Biesta foregrounds relationality. However, educational relationality is still theorised as someone educating somebody else (see above citation), therefore in humanistic terms -education is about human development (see also Murris, 2016).

Both, the knowledge-centered approach with the educator as the 'sage on the stage', and the student-centred approach "find their points of departure not in the processes, but in stable identities existing before and after the process" (Ceder, 2016, p.18; my emphasis). The knowing subject is formed (teacher-centred) or transformed (student-centred). The pedagogical relationship is between pre-existing entities, individual people. And this is even the case in Biesta's educational philosophy. The relationality presupposed is that between "bothparticipating organisms" (see above citation) in an existential event. Now, what difference does it make to move the focus away from the human individual (either teacher or learner) and put relationality at the centre of pedagogy? What difference does this make epistemologically, politically and ethically? Does it shift the 'who' of knowledge production and would the knowledge produced be different? What is the role of the educator in this kind of education? In order to answer these questions, I turn to the philosophy of critical posthumanism and conceptualise an educational intra-relationality with, at the heart of my argument, a posthuman reconfiguration of the educator. For the latter, I will draw on the posthuman methodology of diffraction to read two familiar Platonic metaphors (the midwife and the stingray) through the figuration of a pregnant body.

Epistemological orphans and Nomadic subjectivity

Despite the transformational potential to think in terms of teaching as a relational encounter, Biesta's notion of 'subjectification' is still too much of a humanist notion and assumes human exceptionalism (although he refrains from articulating what a human is). Inspired by Levinas and Arendt, Biesta's ethics of subjectivity is, of course, not formulated in indivi-dual metaphysical terms such as 'being', 'essence' or 'nature' (Biesta, 2014, p.19), but agency seems to be attributed to human subjects and the discursive only. Critical posthumanist Rosi Braidotti (2002, 2006, 2013) argues against a notion of subjectivity that attributes agency only to (individual) humans. Moreover, she points out that only certain humans have been accredited full agency: the capital 'I' as transcendental signifier. The yardstick by which the worth of the knowing subject (the 'I') is measured, is the human of a particular gender (male), race (white), able-bodied and with a particular sexual orientation (heterosexual); the humanist ideal of Leonardo da Vinci's Vitruvian Man (Braidotti, 2013). Posthumanists problematise this narrow, patriarchal view of the 'human' of humanism and have "given us a language where we can now describe much more intricately and robustly how human beings - not just their minds but their bodies, their microbiomes, their modes of communication and so on - are enmeshed in and interact with the nonhuman world", and this includes technology (Lennard and Wolfe, 2017, n.p.). The power producing human/nonhuman binary is based on certain engrained habits of thought about knowledge and intelligence and is "inherently oppressive and violent" (Lennard and Wolfe, 2017: n.p). Why is this the case?

Meaning making and knowledge production as an anthropocentric affair separates the knower (mind) from the known (body) and knowledge (epistemology) from being (ontology). In contrast, education in the posthuman age abandons the patriarchal Cartesian project that privileges the mind as a substance - the ontological and epistemological home of consciousness and thought. The power producing binaries on which this substance ontology rest are multiple: inner/outer, mind/body, cognition/emotion, reality/fantasy, culture/nature and so forth. These binaries produce differences that include and exclude, and structure what counts as 'real' knowledge and 'worthwhile' learning (Murris, 2016). Modernist education assumes that the knowing subject has so-called 'objective' access to this world 'out there', at a distance, with the mind producing knowledge through cognition, for example, acquiring knowledge of a concept through definitions. In education, we tend to rely on words to define, to pin down truth, but as Tim Ingold (2015, ix) puts it strikingly "adrift upon the printed page, the word has lost its voice". Helena Pedersen points out that there are "many ways of relating to the world, of which 'human' ways only constitute a small subset" and human language is after all, only "part of a wider natural-semiotic system", transcending "traditional disciplinary boundaries between natural sciences and social/humanist sciences" (Pedersen, 2015, 60, 65). Posthumanists position the knowing subject as part of the world and not separate from it, therefore the challenge is to find other, more tacit ways of experiencing the world that also account for nonhuman or more-than-human experiences.

Braidotti (1991, p.2) urges everyone instead to be "epistemological orphans", that is, knowing subjects without an authoritative father who is 'the' expert of the meanings of texts, for example, and 'nomadic subjects' (Braidotti, 2006, 2013). The nomadic subject is not only epistemologically homeless, but also dis/continuously (Barad, 2014) 'becoming' - a corporeal entity that has spatio-temporal force - that is, embedded and embodied, and therefore immanent and dynamic (Braidotti, 2006, pp. 151-152). Importantly, 'embodied' is meant as 'transindividual' (Massumi 2014), not a body bounded by a skin as a unit in space and time, but an in/determinate subject. The nomadic subject does not have one singular stable identity and is not firmly located geographically, historically, ethnically, or 'fixed' by a class structure. The key idea here is that self is not 'subject-as-substance', but always 'subject-in-process', and always produced involving contradiction and multiplicity.

Biesta's educational philosophy also does not take into account the agential performativity of matter. Although neither Braidotti, nor feminist philosopher and quantum physicist Karen Barad, talk about child (or age) as a category of exclusion, their work is highly relevant for education. For a further broadening of who, or what, matters epistemologically, ontologically and ethically in education, I turn to Karen Barad's agential realism.

Agential realism, distributed agency and runny noses

A posthuman relational ontology changes how we see the more-than-human; not inert, passive things in space (as mere background to what happens, for example, in a classroom), but requires an un/learning of agency "outside the acting, human body" (Rotas, 2015, p.94). The posthuman notion of distributed agency (Bennett, 2010), or mutual performativity (Barad, 2007), changes how we think about causality, and shifts what we mean by knowledge-production in education. Karen Barad argues that agency is an enactment (Barad, 2007, p.235). Matter is an "active participant in the world's becoming" (Barad, 2007, p.136). With 'matter', Barad (2014) does not mean inert, passive substances that need something else (e.g. a spirit) to bring them alive or to have agency - a rupturing of the animate/inanimate binary. Matter is not a thing, 'in' time and space, but it materialises and unfolds in different temporalities.

The key to understanding Karen Barad's agential realism is her diffractive reading of queer theory and quantum physics. It provides 'multiple and robust' empirical evidence that atoms are not as 'simple' as they were once thought to be (Barad, 2007). They are real in the sense that they are bits of matter that can be 'seen', picked up, one at a time, and moved (Barad, 2007). They can be further divided into subatomic particles such as, for example, quarks and electrons, but importantly they do not take up determinate positions 'in ' space and time (Barad, 2007). Nature (or world) is not simply 'there' or 'given', but the entangled nature of nature means that things only become distinguishable as determinately bounded through their intra-action (Barad, 2007). They cannot be located, as their being extends ontologically across different spaces and times (Barad, 2007). It is the queerness of quantum phenomena that unsettles the distinctions we routinely make between being, knowing and doing. Barad (2007, pp.392-393) argues that the "very nature of materiality is an entanglement" and not only at micro-level as the dichotomy between micro and macro is human-made. The interconnectedness of all human and nonhuman bodies implies that there are no individual agents and no singular causes (Barad 2007). All actions of human and nonhuman bodies matter epistemologically, ontologically and ethically and at the very same time.

Agential realism disrupts not only ontologies and epistemologies, but also an ethics that takes human exceptionalism as its starting point. Barad (2012, p.81) explains that "responsibility is not an obligation that the subject chooses, but rather an incarnate relation that precedes the intentionality of consciousness. Responsibility is not a calculation to be performed" (Barad, 2012, p.81). So what does it mean to be take responsibility for one's actions as educator?

Taking responsibility is not about choosing "the right response, but rather a matter of inviting, welcoming, and. . . "providing opportunities for the organism to respond" (Barad, 2012, p.81). Therefore, posthuman ontology implies an intra-relational ethics - an ethics that is implied, not applied (Ceder, 2016) and requires a different relationality 'between' educator and learner.

Although Barad would probably be sympathetic towards Biesta's proposal of a relational subjectivity, she maintains that meaning and matter are always ontologically entangled and she therefore queers4 an anthropocentric epistemology - the idea that meaning making is a social process, that is, involves human animals only. She writes: "Neither discursive practices nor material phenomena are ontologically prior or epistemologically prior.. .matter and meaning are mutually articulated" (Barad, 2007, p.152). Therefore, teaching means "transcorporeal engagements, involving other faculties than the mind.. .[making] matter intelligible in new ways" (Lenz Taguchi, 2010, p.267). For a posthumanist human and nonhuman, matter always exists in entangled intra-active relations. Barad's neologism 'intra-action' or 'intra-activity' should not be confused with notions such as 'inter-subjectivity' or 'inter-activity' (as in student-centred pedagogies), which assume pre-social independently existing human subjects (in relation with one another) - the kind of subjectivity assumed by psychological scientific discourses, for example.

Barad's seminal work Meeting the Universe Halfway (2007) has already influenced educational practices (see e.g. Lenz Taguchi, 2010; Hultman and Lenz Taguchi, 2010; Kuby and Gutshall Rucker, 2016; Murris, 2016; Pedersen, 2016). This 'material' or 'ontological turn' has informed a new scholarship in education to focus not only on the human and the discursive, but also to include the more-than-human, such as chairs, textbooks, the national curriculum, governing bodies, atmosphere, runny noses, the absence of nonhuman animals, ancestors, the land, or the video cameras that 'collect' data for educational research. These scholars include, but at the same time, move beyond the discursive.

Posthuman subjectivity and methodologies

Posthuman and non-representational methodologies move beyond the personal and avoid psychological, psycho-analytical or sociological interpretations that involve reflection on what has happened (see e.g. Snaza and Weaver, 2015; Koro-Ljungberg, 2016; Lather, 2016; St Pierre, Jackson and Mazzei, 2016; Taylor and Hughes, 2016; Vannini, 2015). They are characterised by "overwhelming subject-fatigue" (Pedersen and Pini, 2016, p.1), and involve being suspicious of any method "that privileges both speaking and hearing human subjects" and regard 'voice' "as a prime source of 'lived experience' and meaning" (Pedersen and Pini, 2016, p.2). A posthumanist articulation of teaching and learning disrupts how in education we traditionally see the knowing subject, whether this subject is a teacher or learner. The posthuman subject is not an individual with distinct boundaries, but "spread out", like "a flow of energies, constituted in a total interdependence with other humans and the matter and physical intensities and forces around us" (Palmer, 2011, p.7). An individual is not a "centred essence" who remains the same through time and space, but instead comes into existence through the encounter with other material-discursive agencies (Petersen, 2014, p.41). It is this move from the discursive to the material-discursive that constitutes a posthuman ontology that has implications for the figuration of the educator. For Deleuze and Guattari (1987/2013), a human being is not a singular subject (or product), but multiple. Mazzei (2013, p.733) explains this multiplicity as an "assemblage, an entanglement, a knot of forces and intensities that operate on a plane of immanence and that produce a voice that does not emanate from a singular subject". This also means that agency and intentionality are not located 'in' a person (learner or teacher), but are always produced in relation with material-discursive human and nonhuman others.

An intra-active relational ontology disrupts our understanding of causal relations and enables us to talk about materials intra-actively and how human and more-than-human bodies render each other capable (Haraway 2016). Posthumanism provokes the urgent question about what the role of the (human) educator is in educational settings. I will now use Barad's posthuman methodology of diffraction to propose a posthuman reconfiguration of the educator.

The diffractive methodology and the subjectivity of the researcher

The non-representational posthuman methodology of diffraction aims to playfully breathe new life into existing pedagogical practices and create an interference pattern that disrupts humanist binaries, particularly the individual/society, child/adult, learner/teacher, theory/practice binary. First developed by Haraway (1988) and built on by Barad through her interpretation of quantum physics (2003, 2007, 2012, 2014), diffraction should not be understood as a metaphor, which would imply representationalism. Barad's significant contribution to both physics and philosophy is to see the ontological implications of what feminist philosopher Donna Haraway and quantum physicist Niels Bohr before her thought were mainly epistemological issues. I have already shown how quantum physics troubles the determinate position of the electron in space and time. What was not clear yet though, was the role of the apparatus that measures in research. Barad (2014, p.178) shows that quantum entanglements are not about intertwining "two (or more) states/entities/events", but that they call into question "the very nature of twoness, and ultimately of one-ness as well". The concept 'between' will therefore never be the same and this also holds for the relationship 'between' researcher ('subject') and the researched ('object'). Salient here is the idea that there are no absolute insides or outsides and that the researcher participates in re/configuring the world. Does this disruption of the nature/culture binary mean that the researcher is therefore subjective? Barad (2007, p.91) explains the Cartesian assumptions involved in the question itself:

Making knowledge is not simply about making facts but about making worlds, or rather, it is about making specific worldly configurations - not in the sense of making them up ex nihilo, or out of language, beliefs, or ideas, but in the sense of materially engaging as part of the world in giving it specific material form. And yet the fact that we make knowledge not from outside but as part of the world does not mean that knowledge is necessarily subjective (a notion that already presumes the preexisting distinction between object and subject that feeds representationalist thinking). At the same time, objectivity cannot be about producing undistorted representations from afar; rather, objectivity is about being accountable to the specific materializations of which we are a part. And this requires a methodology that is attentive to, and responsive/responsible to the specificity of material entanglements in their agential becoming.

For the rest of the paper, I show how such a diffractive methodology can be put to work. Bohr's famous two-slit diffraction experiment (Barad, 2007) made evident that under certain conditions light behaves like a particle (as Newton thought) and under other conditions it behaves like a wave, described by Bohr's influential complementarity theory. Electrons are neither particles nor waves -"a queer experimental finding" (Barad, 2014, pp.173). Wave and particle are not inherent attributes of objects. But, "the nature of the observed phenomenon changes with corresponding changes in the apparatus" that measures it (Barad, 2007, p.106). Electrons and the differences 'between' them are neither here nor there, this or that, one or the other or any other binary type of difference; and what holds for an electron also holds for a human (Barad, 2014). The ontology of entities emerges through their relationality, and not only at quantum level. As we have seen, quantum physics gives experimental evidence that subject and object are inseparable, non-dualistic wholes at all ontological levels.

Diffraction as a methodology is different from reflection, which involves a looking for the same or similar. Diffraction means "to break apart in different directions" (Barad, 2014, p.168). Diffraction patterns hold for water waves, as well as sound waves, or light waves (Barad, 2007, p.74). It is where they interfere or overlap that the "waves change in themselves in intra-action" (Lenz Taguchi, 2010, p.44) and create a "superposition" (Barad, 2007, p.76). The diffractive activity of reading texts, images or ideas through one another is methodologically a 'cutting together-apart' as one move (Barad, 2014). As Barad (2014, p.168) explains "the quantum understanding of diffraction troubles the very notion of dicho-tomy - cutting into two - as a singular act of absolute differentiation, fracturing this from that, now from then". Dichotomies (from the Greek διχοτομία) derive from particular 'cuts', therefore differences are not found, but made and their production needs to be queered (Barad, 2012). To queer is not a fixed, determinate term with a stable meaning and referential context (Barad, 2012), but it is the ethico-political practice of radically questioning identity and binaries (Barad, 2012). Especially relevant for education, this queering includes the disruption of the nature/culture binary, and informed by the experimental findings of quantum physics the queerness of causality, matter, space, and time. Queering is an un/doing of identity.

So how does the diffractive methodology work in the context of the role of the educator in posthuman intra-relationality? Barad's methodology is affirmative, not critical, but to place different transdisciplinary practices in conversation with one another whilst paying attention to fine details and the exclusions this action produces by investigating how 'objects' and 'subjects' and other differences matter, and for whom they matter (Barad 2007). The methodology helps to get a feel for how differences are produced without rejecting, comparing or synthesising. The experimentation is not a cerebral (cognitive) engagement by the researcher. It involves playful experimentation by paying attention to how bodies affect one's own being as part of the world. Living without bodily boundaries opens up spaces for imaginative, speculative philosophical enquiry that ruptures, unsettles, animates, reverberates, enlivens and reimagines. The methodological use of diffraction unsettles the separateness of being, knowing and responding.

Reading three figurations of the educator through one another diffractively

Rosi Braidotti (2002) uses the term figurations as an alternative to metaphors. These figurations are embodied imaginings, cognitive assumptions and beliefs. She explains that "figurations are not figurative ways of thinking, but rather more materialistic mappings of situated, or embedded and embodied positions" (Braidotti, 2012, p.13). They are not metaphors, but social-material positions: "living maps, a transformation account of the self" (Braidotti, 2011, p.14). Educational relationality involves (sometimes contradictory) enacting figurations of teacher and learner, that is, acts of shaping into particular figures; and they always express particular locations and power relations (and are therefore political). Unlike metaphors, figurations demand a sense of "accountability for one's locations" and a "self-reflexivity" that is not an individual activity, but an intra-active process that "relies upon a social network of exchanges" (Braidotti, 2002, p.69). These subject positions are hybrid, multi-layered, often internally contradictory, interconnected and weblike. Drawing on Deleuze, Braidotti (2002, p.78) argues that the transformational project is to develop alternative "post-metaphysical" figurations (or reconfigurations) and new images of subjectivity that break with theoretical representations, and that creatively express active states of being - one that helps materialise a different kind of knowledge and produces a more equal epistemic relationship.

The first figuration of the educator I use in my diffractive reading is that of a stingray - a famous image from Ancient Greek philosopher Socrates in the Platonic dialogue, Meno:

Meno: 'Socrates, even before I met you they told me that in plain truth you are a perplexed man yourself and reduce others to perplexity. If I may be flippant, I think that not only in outward appearance but in other respects as well you are exactly like the flat sting-ray that one meets in the sea. Whenever anyone comes into contact with it, it numbs him, and that is the sort of thing that you seem to be doing to me now...'

Socrates: '.. .if the sting-ray paralyses others only through being paralysed itself, then the comparison is just, but not otherwise. It isn't that knowing the answers myself, I perplex other people. The truth is rather that I infect them also with the perplexity I feel myself.' (Meno, 80a-c; in Guthrie, 1956)

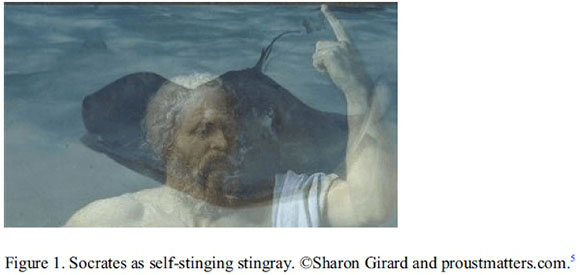

So, for Socrates, an educator is not just a 'stingray' (see Figure 1), but a self-stinging stingray.

In the sea, the stingray is dangerous; it numbs its victims. Socrates as stingray also numbs himself. In Socratic teaching the educator is as 'numb' and perplexed as the learners (Matthews, 1999). The figure of Socrates is well-known as someone "who questions others, not from a position of assumed knowledge, but rather from a position of self-confessed ignorance" (Matthews, 1999, p.89). Typically, his questions are not about difficult matters, but exactly those matters that "most people think too simple and basic for a grownup to question" (Matthews, 1999, p.89). The danger, therefore, of the stingray is that its paralysis undermines confidence and can start to shake the certainty with which people habitually take for granted the meaning of the abstract concepts we routinely use in education, such as 'number', 'causality' or 'world'. It can also cause embarrassment, because concepts investigated are often common words that adults claim familiarity with and certainty about their meaning. So they can be made to look foolish. The meaning of these concepts is, however, always contestable, and everyone has ideas about what they mean by them, based on their own lived experiences. And it is here that the more positive figure emerges - the educator as a midwife, another famous character of Socrates, whose mother was a midwife. Interestingly, stingrays give birth to multiple, live young. The figuration of the midwife is introduced in the dialogue Theaetetus. Socrates, himself barren (of both child and wisdom, he claims), helps others to deliver their theories, insights and ideas about philosophical concepts (Matthews, 1999, p.88). The educator assists in the process of giving birth ('labour'), so has a more productive role, even assisting in abortions and false pregnancies, that is, identifies "sham theories, doctrines and analyses" (Matthews, 1999, p.91). The power of Plato's figuration of the midwife is that the educator is not seen as the source of the knowledge - understanding has to come from 'within' through reasoning (including the emotions and feelings). The educator has no knowledge to impart or transmit, but learners "discover within themselves a multitude of beautiful things, which they bring forth into light" (Socrates quoted in Matthews, 1999, p.88). There is not one theory (baby), but multiple, like the stingray giving birth. This "superposition" (Barad, 2007, p.76) created by diffracting the two figurations of the pregnant self-stinging stingray and the midwife foregrounds an educational relationality that is not about transmission (from teacher to learner), nor is it about students discovering knowledge by themselves. There is an interaction between student and educator as an essential part of teaching and learning with multiple and unpredicted outcomes (births are notoriously unpredictable).

Now, despite the power of this concept of the educator, both stingray and midwife assume individual subjectivity, that is, a relationality between two ontological entities 'in' the world: educator (self-stinging stingray and midwife) and learner. However, there is something more that can be said of the stingray, which does justice to intra-relational subjectivity. As Barad (2011) points out, the neuronal receptor cells in stingrays make it possible for these creatures to anticipate a message which has not yet arrived - a kind of clairvoyance, one could argue, that strikingly describes the embedded and transindividual embodied listening of the posthuman educator. This practice disrupts linear time: past, present and future are threaded through one another in Barad's diffractive reading of quantum physics. It would mean, as an educator, not only listening to and following what the human is saying or writing, but to trace the human and more-than-human relational corporeal entanglements and to be attuned to what is not there as yet, but has the potential to be expressed (the virtual), for example, by including silences, transmodal opportunities for expression, small group work, or going for a walk. This cannot be predicted or planned for. Confounding the logic of causality, stingrays unlock themselves before this is (apparently) necessary (Barad, 2011).

Furthermore, an even more powerful figuration can be created through diffracting the created superposition of the pregnant stingray with that of another body that is part of this world: the female6 human animal.

The pregnant stingray reconfiguration

The pregnant female body (not as a metaphor) contests Western metaphysical assumptions about subjectivity. The relationship between mother and unborn baby is not simply one of containment. Lakoff and Johnson (1980, p.29) argue that metaphors of containment work at a pre-conceptual level and shape our (mostly universal) experience of embodiment and territoriality. Feminist philosopher Christine Battersby rejects the idea that everything is either inside a container or outside of it. When reading Lakoff and Johnson's account of embodiment she comments:

I register a shock of strangeness: of wondering what it would be like to inhabit a body like that. And that is because I do not experience my body as three-dimensional container into which I 'put various things' - such as 'food, water, air' - and out of which 'other things emerge (food and water wastes, air, blood, etc.). (Battersby,1998, p.41-2)

She argues that the containment model for bodily boundaries and selves might be more typical of male experience, which has shaped the western metaphysical notion of self and self-identity: bodies as containers and selves as autonomous (Battersby, 1998, p.54) - a body that is One and not the Other. In metaphysical constructions of self, philosophers have bypassed the female body which "is messy, fleshy and gapes open to otherness - with otherness 'within', as well as 'without'" (Battersby, 1998, p.59). Take, for example, the meaning of the concept 'innate'. When theorists use the concept, it is assumed that what is meant is 'before birth', and not 'before conception'. The relationship the mother has with her unborn baby simply does not count in the Western construction of subjectivity. Intrapersonal relationships do not exist before the baby is born. But the female body is different from the male body. It has the potential of becoming more than one body out of its own flesh. Battersby concludes that there ".. .is no sharp division between 'self and 'other'. Instead, the 'other' emerges out of the embodied self, but in ways that mean that two selves emerge and one self does not simply dissolve into the other" (Battersby, 1998, p.8). In other words, the male body "has acted as both norm and ideal for what is to count as an entity, a self or a person" in Western philosophy (Battersby, 1998, p.50). Inspired by French feminist philosopher, Luce Irigaray, Battersby proposes a different account of identity: a different understanding of boundaries leads to a different conceptualisation of (self)identity. She understands identity as emerging out of patterns of potentialities and flow (Battersby, 1998, p.53). When there are no clear boundaries between 'self and 'not-self, it becomes possible to think of the self as always in flux, and to privilege 'becoming' over 'being' (Battersby, 1998, p.55). For Lenz Taguchi (2010, p.95), the pregnancy image holds within itself "a potentiality of new invention and new becoming from what already is".

So, what are the implications of the interference pattern or superposition created by reading these three figurations diffractively through one another? What is the new created through the posthuman methodology? And what are the implications for a different ethics in education? The figuration of the pregnant stingray en-courages educators to reconfigure their own practices through a doing of subjectivity differently. The relationship 'between' learner and educator is not characterised by body boundaries that are closed, autonomous or impermeable, but allows "the potentiality for otherness to exist within it, as well as alongside it". The agency of both teacher and learner are characterised "in terms of potentiality and flow. Our body-boundaries do not contain the self; they are the embodied self" (Battersby, 1998, p.57). Both teacher and learner do not have pre-existing identities (as in post-postmodern relationality), which, for example, respond or react to new information. Intra-relationality is an ontology whereby teacher and learner are engaged in a continuous flow and fluidity between humans and more-than-humans: "new identities are born out of difference; self emerges from not-self; and identity emanates from heterogeneity via patterns of relationality" (Battersby, 1998, p.58). Pregnant stingrays are multiple and unbounded inhuman becomings, who can anticipate the not-yet-thought with a fleshy openness to otherness (Battersby, 1998), including doing justice to the in/determinate agency of the material world in knowledge construction.

The pregnant stingray reconfiguration of the teacher has been created through a diffractive reading of three figurations: the midwife (who assists in giving birth to new ideas from 'within'), the stingray (who numbs others and herself through philosophical perplexity), and the pregnant body (a body that can be one and more than one at the very same time, thereby queering identity). The pregnant-stingray-educator treats her own knowledge as contestable, and is willing to inhabit the perplexity of the dynamic and always contestable nature of knowledge itself. This 'being-with' the human and more-than-human in knowledge construction (Haraway, 2016) also renders human learners capable, whatever their age or social status. This ontological shift in educational intra-relationality involves epistemic modesty and epistemic equality with bodily boundaries that are not closed, autonomous or impermeable, but allow the potentiality for otherness to exist within it. Such educators are not 'ventriloquists' (Kennedy, 2006), which is the case in teacher-centred education when teachers already know beforehand what learners are going to say. In posthuman education, the aim is not to represent, or reproduce, or recognise (as in qualification and socialisation as aims of education), but to embrace a practice that is passionate and spontaneous, with "students and teachers entering a zone of interrogation - in putting themselves, their lives, their passions and beliefs into question through the experience of thinking together (Kohan, 2015, p.65). Rather than 'filling' students, they are 'emptied' of the truths in which they are installed (Kohan, 2015, p.66). This process of intra-active unlearning cannot be anticipated or expected (Kohan, 2015), either by the teacher, or by the learner; and it is this playful relationship with knowledge that comes easier for children who have not invested as much of their identity yet in what they know. What this could look like in practice is described elsewhere (Murris, 2016) and goes beyond the scope of this paper. The challenge indeed is how to prepare (student) teachers for their role as pregnant self-stinging stingrays where they need like a stingray "to anticipate .... a kind of clairvoyance" (Barad, 2011, p.131). Disrupting the binaries of individual/society, teacher/learner and child/adult -the binary logic of Western metaphysics - requires posthuman educators to listen with an open fleshiness towards the human and the more-than-human in order to anticipate the not-yet-thought.

Acknowledgement

This work is based on research supported by the National Research Foundation of South Africa [Grant number 98992].

References

Barad, K. (2003). Posthumanist performativity: Toward an understanding of how matter comes to matter. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 28 (31), 801-831. [ Links ]

Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Durham: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Barad, K. (2011). Nature's queer performativity. Qui parle, 19 (2) Spring/summer, 121-58. [ Links ]

Barad, K. (2012). Intra-actions: an interview with Karen Barad by Adam Kleinman. Mousse #34 June,76-81.

Barad, K. (2014). Diffracting diffraction: Cutting together-apart. Parallax. 20(3), 168-187. [ Links ]

Battersby, C. (1998). The phenomenal woman: Feminist metaphysics and the patterns of identity. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Bennett, J. (2010). Vibrant matter: A political economy of things. Durham: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Biesta, G.J.J. (1994). Education as practical intersubjectivity: Towards a critical pragmatic understanding of education. Educational Theory, 44(3), 299-317. [ Links ]

Biesta, G. J. J. (2006). Beyond learning. Boulder USA: Paradigm Publishers. [ Links ]

Biesta, G. J. J. (2010). Good education in an age of measurement: Ethics, politics, democracy. Boulder; USA: Paradigm Publishers. [ Links ]

Biesta, G.J.J. (2012). The future of teacher education: Evidence, competence or wisdom? Research on Steiner Education, 3(1), 8-21. Accessed: 10th June, 2012 www.rosejourn.com. [ Links ]

Biesta, G.J.J. (2014). The beautiful risk of education. Boulder; USA: Paradigm Publishers. [ Links ]

Biesta, G.J.J. (2016). The rediscovery of teaching: On robot vacuum cleaners, non-egological education and the limits of the hermeneutical world view. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 48(4), 374-392. [ Links ]

Braidotti, R. (1991). Patterns of dissonance: A study of women in contemporary philosophy. Trans. by E. Guild. Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Braidotti, R. (2002). Metamorphoses: Towards a materialist theory of becoming. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. [ Links ]

Braidotti, R. (2006). Transpositions: on nomadic ethics. Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Braidotti, R. (2011). Nomadic theory: The portable Rosi Braidotti. Columbia: Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

Braidotti, R. (2013). The posthuman. Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Ceder, S. (2016). Cutting through water: Towards a posthuman theory of educational relationality. Doctoral dissertation. Faculty of Social Sciences, Lund University, Sweden. [ Links ]

Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. (1987/2013). A thousand plateaus. Translated and a foreword by B. Massumi. London: Bloomsbury. [ Links ]

Guthrie, W.K.C. (1956). Plato: Protagoras and Meno. London: Penguin. [ Links ]

Haraway, D. (1988). Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism as a site of discourse on the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3), 575-99. [ Links ]

Haraway, D. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham and London: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Hultman, K. & Lenz Taguchi, H. (2010). Challenging anthropocentric analysis of visual data: a relational materialist methodological approach to educational research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 23(5), 525-542. [ Links ]

Ingold, T. (2015). Foreword. In P. Vannini (Ed). Non-representational methodologies: Re-envisioning research, pp vii-x. New York and London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Kennedy, D. (2006). Changing conceptions of the child from the renaissance to post-modernity: A philosophy of childhood. New York: Edwin Mellen Press. [ Links ]

Kohan, W. (2015). Childhood, education and philosophy: New ideas for an old relationship. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Koro-Ljungberg, M. (2016). Reconceptualizing qualitative research: Methodologies without methodology. New York: SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

Kuby, C. & Gutshall Rucker, T.G. (2016). Go be a writer!: Expanding the curricular boundaries of literacy learning with children. New York: Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

Lakoff, G. & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by. Chicago, University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Lather, P. (2016). Top ten+ list: (Re)Thinking ontology in (post)qualitative research. Cultural Studies ** Critical Methodologies, 16(2), 125-131. [ Links ]

Lennard, N. & Wolfe, C. (2017, 9 January). Is humanism really humane? An interview with Cary Wolfe. New York Times. The Stone. Accessed 1 March 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/09/opinion/is-humanism-really-humane.html?r=0

Lenz Taguchi, H. (2010). Going beyond the theory/practice divide in early childhood education. London: Routledge Contesting Early Childhood Series. [ Links ]

Matthews, G. (1999). Socratic perplexity and the nature of philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Massumi, B. (2014). What animals teach us about ethics. Durham: Durham University Press. [ Links ]

Mazzei, L.A. (2013). A voice without organs: interviewing in posthumanist research, International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education. 26(6), 732-40. [ Links ]

Murris, K. (2013). The epistemic challenge of hearing child's voice [Special issue]. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 32(3), 245-259. [ Links ]

Murris, K. (2016). The posthuman child: Educational transformation through philosophy with picturebooks. Contesting Early Childhood Series (Eds G. Dahlberg and P. Moss). London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Murris, K. & Verbeek, C. (2014). A foundation for foundation phase teacher education: making wise educational judgements. South African Journal of Childhood Education, 4(2),1-17. [ Links ]

Palmer, A. (2011). How many sums can I do"? Performative strategies and diffractive thinking as methodological tools for rethinking mathematical subjectivity. Reconceptualizing Educational Research Methodology, 1(1), 3-18. [ Links ]

Pedersen, H. (2015). Educational policy making for social change: A posthumanist intervention. In N.Snaza & J.A.Weaver (Eds). Posthumanism and Educational Research (56-76). New York and London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Pedersen, H. (2016). Animals in schools: Processes and strategies in human-animal education. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. [ Links ]

Pedersen, H. & Pini, B. (2016). Educational epistemologies and methods in a more-than-human world. Educational Philosophy and Theory. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2016.1199925

Petersen, K.S. (2014). Interviews as intraviews: A hand puppet approach to studying processes of inclusion and exclusion among children in kindergarten. Reconceptualising Educational Research Methodology. 5(1), 32-45. [ Links ]

Rotas, N. (2015). Ecologies of praxis: Teaching and learning against the obvious. In N. Snaza. & J.A. Weaver (Eds). Posthumanism and educational research (91-104). New York and London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Snaza, N. & Weaver, J.A. (Eds.). (2015). Posthumanism and educational Research. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Snaza, N., Applebaum, P., Bayne, S, Carlson, D., Rotas, N., Sandlin, J., Wallin, J., & Weaver, J. (2014). Toward a posthumanist education. Journal of Curriculum Theorizing, 30 (2), 39-55. [ Links ]

St Pierre, E. A., Jackson, A.Y., & Mazzei, L. A. (2016). New empiricisms and new materialisms: Conditions for new enquiry. In Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies, 16, (2), 99-110. [ Links ]

Taylor, C. & Hughes, C. (2016). Posthuman Research Practices in Education. London: Palgrave. [ Links ]

Lenz Taguchi, H. (2012) A diffractive and Deleuzian approach to analysing interview data. Feminist Theory, 13 (3), 265-281. [ Links ]

Vannini, P. (2015). Non-representational methodologies: Re-envisioning Research. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Received 16 February 2017

Accepted 3 July 2017

1 Therefore, a teacher's identity is not absolute, but "sporadic", that is, "only emerges at those moments when the gift of teaching is received" (Biesta, 2014, p.54). Receiving the gift of teaching is to welcome the unwelcome, to give a place to inconvenient truths and difficult knowledge and it is at precisely that "moment that we give authority to the teaching we receive" (Biesta, 2014, p.55).

2 It is difficult to extract a coherent notion of subjectivity from his writings. For example, against the idea that a teacher is a facilitator of learning, Biesta argues that the teacher has "to bring something new to the educational situation, something that was not already there" (Biesta, 2014, p.44) and teaching can therefore not "be entirely immanent to the educational situation but requires a notion of transcendence". His arguments are complex and not directly relevant for my key arguments here, but there does seem to be a tension between his conception of a teacher and the subjectivity it presupposes and the notion of 'coming into the world'.

3 There is no space in this article to do justice to the complex notion of practical judgements or phronesis and it is not relevant for the main argument.

4 As we have seen earlier, with 'queer' Barad does not just mean 'strange' but it disrupts the Nature/Culture binary and is therefore an 'undoing of identity', because waves and particles are ontologically different entities. It raises the key question how is it possible that an electron can be both. See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cS7szDFwXyg. [Accessed: 21/02/2015].

5 Downloaded from http://proustmatters.com/tag/socrates/; Accessed 15/05/2015. One can freely copy material from this site provided full and clear credit to Sharon Girard and proustmatters.com has been given.

6 Although it is not impossible that men will also be able to birth babies in the future.