Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

The Independent Journal of Teaching and Learning

On-line version ISSN 2519-5670

IJTL vol.18 n.1 Sandton 2023

ARTICLES

Transforming students' perceptions of selfhood through pedagogical theatre strategies

Sharon Margaretta Auld

Varsity College, The Independent Institute of Education, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Traditional approaches to postgraduate psychological education are inherently reductionistic - drawing on positivist theoretical models designed for understanding our physical bodies rather than our thoughts, feelings, and actions. Taking a decolonial stance, and advocating for critical reflexivity, this paper argues that theatre holds a potential space for students to engage with selfhood in complex ways. Positioned within critical pedagogy, theatre strategies can present vital opportunities to personalise historical eras, enabling intertwined psychodynamic, cultural, economic, and ideological factors to impact sensuously, emotionally, and cognitively on students. Such immersive opportunities can foster students' awareness of the social embeddedness of subjectivity, prior to their engagement with clinical practice. Drawing on Fugard's political tragedy, 'Sorrows and Rejoicings', possible guidelines are suggested as to how theatre can educate students about the impact of taken-for-granted socio-political attitudes, norms, and values on selfhood.

Keywords: chosen traumas, critical pedagogy, decolonisation, postgraduate psychological education, social unconscious

INTRODUCTION

Gender-based violence, poverty, racism, sexism, homophobia, xenophobia, and the failure of social care are just a few of the socio-political struggles faced by many, daily. To ignore these struggles in postgraduate psychological education-maintains a split between the individual and society. This split cultivates the impression that our social embeddedness does not contribute to the aggression, hatred, apprehension, frustration, and misery we can experience in our lives.

One of the principal ways our social embeddedness impacts us is through the idea of race - a classification system that sorts citizens socially, based on physical characteristics (Akhtar, 2012). Race organises culture and knowledge production in both the Global North and Global South. For example, Quijano and Ennis (2000), working in Latin America, describe how race historically has been used to justify colonial domination. Acting as a social hierarchy, race sustains a matrix of colonial power, impacting subjectivity, and leading to racial discrimination and stigmatisation. As a result, colonial racial identities in Latin America - in which whites, blacks, mestizos (mixed race), and Indians have been sorted into distinct groups with broadly shared characteristics - have displaced the many varied indigenous Latin cultures, undermining indigenous knowledge systems, local understandings of distress, and ways of healing (Mills, 2014).

From an African perspective, Frantz Fanon (1986), in his book Black Skin, White Masks, describes the impact of racism on the black psyche and selfhood. In looking at the relationship between the coloniser and the colonised, Fanon discusses how undesirable and unwanted traits are projected onto people with black skin. Importantly, he goes on to describe how such longstanding racist projections are internalised, bringing about a longing (both at the conscious and unconscious level) to be white. In a similar vein, M. Fakhry Davids (2020), a British psychoanalyst, argues that from a young age, black children's internalisation of racism leaves an imprint on their mind. Davids describes how such an internalised racist structure comes to regulate relationships at both a personal and interpersonal level. Ultimately, identifications with and against ethnic and racialised groups depend on unconscious projections on to these groups, and the definition of self in relation to other: rational or irrational; white or black. Such dichotomies are the outcome of power relations, where the second term in the relation -for example irrational or black - is defined as inferior and more marginal (Lo & Diop, 2022). Thus, identification with and against ethnic and racialised groups inevitably impacts subjective experience.

The sociologist, Michael Rustin (2004), writes on the subject of psychoanalytic defenses in a social way. In doing so, he shifts the focus from the individual to the collective psyche. Rustin is interested in explaining why, following the collapse of Soviet communism and the end of the Cold War, Western societies still feel threatened by their enemies. He argues that by identifying a discernible enemy (and projecting destructive impulses onto it) governments can justify aggressive retribution, packaged as counterterrorism. For Rustin, the paranoid creation of an 'evil enemy' serves a cohesive social function, providing citizens with 'psychic reassurances in identification with their nation against its enemies' (Rustin, 2004: 34). Thus, the operation of social defenses (Jaques et al., 1955, Menzies-Lyth, 1961) and the social unconscious (Foulkes, 1964, Fromm & Funk, 201 7) are keys to understanding how we see ourselves and others - as friend or foe, good or bad, desirable or undesirable, healthy or pathological.

To begin educating clinicians in culturally competent practice (Hart, 2020, Tummala-Narra et al., 2018) - where poverty, racism, sexism, homophobia, xenophobia, the failure of social care, and other socio-political struggles, are understood as impacting the meaning we ascribe to our experience - it is vital that students (especially in those working in oppressed and racialised contexts) become aware of the social embeddedness of subjectivity. In response to this need, theatre strategies are put forward towards enhancing subjective awareness.

To substantiate the utility value of theatre, I begin with a review of gaps in the field of postgraduate psychological education, before exploring how theatre can address these areas. In this paper postgraduate psychological education refers to Honours, Masters, and PhD level of study.

The need for culturally competent postgraduate psychological education

Given the dominance of Western positivism (the belief that we can arrive at knowledge by analysing facts without considering values or emotions), postgraduate psychological education has traditionally focused on the asocial, medico-scientific search for explanations of individual behaviour. However, more recently, critics worldwide have highlighted that imposing Western models of psychopathology on other cultures is a damaging form of colonialism (Boyle, 2022, Bracken et al., 2016). This has led to calls by both academics and concerned clinicians to transform postgraduate psychological education in order to view subjectivity as socially embedded (ibid.). Although postgraduate institutes are now more cognisant of the need for appropriate contextual models of education, alternatives to psychiatric diagnosis have had trouble shaking off the legacy of positivism. For example, Boyle (2022) points out that the vulnerability-stress and biopsychosocial models continue to emphasise biological factors over socio-political and relational considerations, preventing emotional distress being understood as a meaningful response to life circumstances. The failure of these alternative models to truly transform, reveals the extent to which positivism has come to organise culture and knowledge production,

impacting what is understood as desirable or 'best practice'. In other words, academic scholarship has been legitimised as a science under parameters established by Western scholars, causing other forms of thinking and knowledge production to become marginalised and stigmatised (Mills, 2014). There is a pressing need, therefore, to decolonise postgraduate psychological education in order for race, class, gender, religion and sexual orientation, as well as other diversities, to be seen as aspects of identity which are dynamics of both the patient and clinician in the therapeutic space (Lobban, 2013).

In my 2023 empirical review of South African psychology Honours students' impressions of their education thus far - the subject of my next study in this area - most students felt ill equipped to engage with the impact of political, economic, and social variables on self-hood. Instead, they felt their education had predominantly been positivistic, fostering a medico-scientific understanding of self, focused on genetic pre-dispositions, personality traits, and intrapsychic phenomena. This is alarming given that some 30 years ago many scholars working against apartheid - for example, Butchart and Seedat (1990), Foster (1989), Gibson (1989), Ingleby (1988), Mohutsioa-Makhudu (1989), Punamäki (1988), and Swartz and Levett (1989) - noted the deep and enduring impacts of political oppression, economic disparity, and apartheid on subjectivity. Given the difficulties encountered in South Africa's transformation from a position of racism and violence to a democratic non-racial society, developing awareness of the socio-political embeddedness of subjectivity remains an imperative (Kagee and Price, 1994).

In order to see ourselves as active agents, creating meaning and making choices in our lives - while also recognising that we are, at various times, both helped and hindered by bodily, environmental, economic, cultural, political, psychological, and ideological factors - we must move away from the positivist dichotomy of individual vs society, and understand how our social embeddedness impacts subjectivity (Boyle, 2022). This argument is rooted in Fanon's (1986) insight into subjectivity as both a private domain as well as a social construction. In other words, subjectivity must be seen as connected to the public processes and practices that contain and restrain it. In keeping with this argument, identity has more recently become theorised as decentred, ambivalent, contradictory, provisional, contextual, and de-essentialised. This represents an important move away from the Western positivistic notion of selfhood as rational and self-aware, to a conceptualisation of self as also being shaped and directed by emotions, unconscious desires, relational elements, and socio-political impacts (Lo & Diop, 2022).

Taking a decolonial stance in education and knowledge production means that we - as researchers, educators, and students - must reflect critically on our relationships with each other, the theories and resources we draw from, and the knowledge produced through these interactions. Decolonial approaches force us to recognise the socio-political context impacting those producing such work. For example, there are specific reasons why the call to decolonise resonates strongly with me. To elaborate, I was born in Northern Ireland during 'the Troubles' - a time that saw Northern Irish society deeply divided in terms of religion and nationality (Auld, 2022a). I completed my education as a clinical psychologist at a university in South Africa - once again, a society deeply divided, this time by race and access to resources. In both countries, such divisions directly impacted selfhood. These divisions restricted where you lived and went to school, the games you played, the language you spoke, the career you aspired to, the friends you made, and whom you could desire and marry. As an immigrant to South Africa, my complicated and at times contradictory positioning within the socio-political norms and values of both the Global South and Global North, emphasise how I inhabit multiple sites. My positioning as both an insider and outsider in various social narratives and discourses, has caused me to question the multiple ways that my context has shaped me (Auld, 2022a, Auld, 2022b, Auld, 2022c).

My complicated and contradictory positioning has led me to realise that subjectivity is impacted by the 'sociocultural power differentials' (Lykke, 2010: 67) or socio-political hierarchies in which it takes shape, while these power relations become more meaningful when viewed through the lens of individual experience. Being able to acknowledge how our own subjectivity has been impacted by the taken-for-granted socio-political power relations into which we are born and raised highlights our inability to divorce ourselves from socio-political influences, and the need to think about how this impacts the therapeutic relationship.

Awareness of how taken-for-granted socio-political norms and values impact subjectivity is supported by scholars such as Butler (1990), Frosh et al. (2002), Grosfoguel (2009), and Haraway (1988). For example, critical theory - the Marxist-inspired movement originally associated with the work of the Frankfurt School - highlights how social structures dominate and oppress. Butler (1990) builds on critical theory in her important work on intersectionality - describing the ways in which systems of inequality based on gender, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, disability, class, and other forms of discrimination, 'intersect' to create unique dynamics and effects. In a similar vein, Haraway (1988) argues against a disembodied subjectivity - where objectivity and neutrality are held up as 'best practice' - and instead advocates for embodied subjectivity. Haraway challenges us to reflect on how our own positioning within available social narratives and discourses shape what we observe. Likewise, Grosfoguel (2009) also argues that we express ourselves within the confines of available socio-political power relations. According to Frosh et al. (2002), our positioning within these hierarchies defines the kinds of experiences available to us. It is imperative, then, that we use an intersectional approach to knowledge systems in postgraduate psychological education, in order to explore how taken-for-granted socio-political power relations interweave with one another and shape subjective reality.

Transgenerational trauma

In my earlier work, exploring the decolonisation and transformation of postgraduate psychological education (Auld, 2022a, Auld, 2022b, Auld, 2022c), I highlighted the group psychoanalytic concept of the 'social unconscious' as a way of assisting students to explore how some of their most deeply held attitudes and values have roots in the cultural and societal circumstances into which they are born. Extending these earlier discussions, the concept of the social unconscious is also helpful in assisting us -as clinicians, researchers, educators, and students - to explore the transgenerational consequences of massive trauma experienced by one group (social, ethnic, or national, amongst others) at the hands of another. This aspect of the social unconscious gives us insight into how issues of personal distress and crisis are intertwined with broader socio-political conflicts.

To elaborate, the concept of the social unconscious was initially formulated by Fromm (2001) and subsequently by Foulkes (2018), Hopper (2002), Volkan (2001), Dalal (1998), and Weinberg (2007), amongst others. In his work, Beyond the chains of illusion: My encounter with) Marx and Freud, Fromm (2001) sought to link Marxist ideas around ideology and the psychoanalytic concept of repression, to grasp how social constructs - which are historical and conditional - can be experienced as natural and inevitable. Drawing from Fromm's work, the concept of the social unconscious allows us to contemplate how we not only repress parts of ourselves, but society itself becomes a repressive force. Going further, Volkan (1999) explains how large groups become used as receptacles for unacceptable ways of thinking, feeling, and behaving (both at individual and group levels), and how this supports socially accepted aspects of identity and a shared sense of sameness. As a result, instead of risking exclusion by trying to meet our own needs - which may be different from those valued in our social system - we accept what is socially valuable and change ourselves accordingly, defensively projecting or repressing the unwanted aspects.

Weinberg (2007) highlights factors such as shared anxieties, fantasies, social defence mechanisms (Jaques et al., 1955, Menzies-Lyth, 1961), myths, and memories as key to the operation of the social unconscious. In his work he focuses on the traumagenic nature of the social unconscious by drawing on Volkan's (2001) thoughts around 'chosen traumas'. Here, Volkan describes how, within large groups, there exists an un-mourned or unresolved psychological representation of a shared trauma in relation to loss. Chosen traumas are pushed into the social unconscious via defensive operations, such as repression and denial. Through generations the unprocessed trauma lies as if dormant, unconscious, and unprocessed within the group, in relation to its former oppressors. If in the future the group is threatened by a new peril, it can fall back on old patterns of responding to conflict, with a reactivation of these past traumas. In other words, as Baldwin (1 985: 41 0) notes,

... the great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are unconsciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is literally present in all that we do.

The operation of the social unconscious is then reflected in the way we absorb, replicate, and reinforce attitudes, norms, and values, without us realising we are doing so, impacting our subjectivity and the meaning which we ascribe to our experience (Dalal, 1998). This insight has an important implication for postgraduate psychological education - namely, an awareness of the social unconscious, and the legacy of chosen traumas, can enable us to understand how culture shapes our behaviour and interactions.

Drawing these points together, to develop culturally informed postgraduate psychological education we need to take a decolonial stance to address the limitations of positivism and undermine racist colonial knowledge production. As a way forward, employing pedagogical strategies which develop awareness of the social unconscious, opens the potential of enabling students to explore the impact of taken-for-granted socio-political attitudes, norms, and values on subjectivity. Such strategies must also allow us to reflect upon the transgenerational legacy of massive trauma, and how this affects the meaning we ascribe to our experience in the here-and-now. Theatre strategies are put forward to facilitate this awareness by bringing historical eras to life, allowing students to explore how psychodynamic, cultural, economic, and ideological factors impact them personally.

Theatre strategies

Moving beyond entertainment to pedagogical utility, theatre has the potential to open an educational space in which our social embeddedness can be brough to awareness, explored, interrogated, and challenged. Theatre has the power to clarify, to inform, to unsettle, to incite, and to arouse. It can be deliberately contrived to focus on socio-political struggles around abuse and exploitation. For example, Brazilian playwright Augusto Boal's (1985) Thieafre of the Oppressed, is a well-known theatre form which stimulates critical observation and representation of reality. This theatre form utilises a set of dramatic techniques whose purpose is to bring to light systemic exploitation and oppression operating within common situations. Another example of the pedagogical utility of theatre is from within my own local community of Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Here, Empatheatre has emerged as a research-based, theatre-making methodology. Empatheatre is co-directed by Mpume Mthombeni, Neil Coppen, and Dr Dylan McGarry, in collaboration with a variety of other artists, academic researchers, and responsive citizens. Starting with action-based research, co-participants and key partners identify issues of socio-political concern, with the aim of developing dramatic productions and creating a space for reflexive deep listening. It follows that, by drawing on theatre productions which are local to the postgraduate psychological education programme, theatre can bring awareness to, provide an experience of, and provoke discussion about, broader socio-economic, cultural, political, and ideological forces impacting upon us as citizens of whatever socio-political context in which we find ourselves.

Elaborating further, as an immersive art form, theatre targets multiple senses simultaneously, engaging the audience mind, body, and soul. Theatre does not simply tell a story - it makes us, as the audience, feel what is happening, affecting us personally. Such active engagement makes theatre useful from a critical pedagogical perspective. Theatre's great strength is in helping students become aware of otherwise taken-for-granted socio-political norms and values that impact them first-hand through the characters in the play, instead of hearing about the second-hand effects of life's struggles during lectures. This transformative experience is only possible because theatre does not bind the student to their own ethnocentric worldview - instead, through theatre, students are able become immersed in the characters' lives. This opens the possibility of a student distancing themselves from their own perspective enough to see the situation in a different way. By so doing, students can contemplate new points of view non-threateningly - facilitating fewer defensive explorations of contentious socio-political realities such as race, class, gender, religion, economic status, and sexual orientation (Alkin & Christie, 2002, Duncan, 2008, Sonn et al., 2013, Stevens et al., 2013).

In his critique of traditional Western teaching methods, Brazilian educator and philosopher Paolo Freire (1970) views students as passive - receiving information in lecture format and simply 'banking' this knowledge without giving it much consideration. Western techniques of learning, such as taking notes or listening to a lecture, do not require students be actively involved (Tovani & Moje, 2017). In other words, with traditional Western education, students are not asked to reflect on, or question, the bias inherent in the knowledge, course content, or classroom resources, that they are being presented. They are also not required to engage critically with, or analyse, how these biases shape their thinking. In other words, they lack a critical consciousness (Freire, 2018). This makes it difficult for students to question the nature of knowledge itself or come up with their own interpretations of the ideas they are presented with.

Responding to Freire's (2018) critique of Western teaching methods, cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT) offers a valuable lens for understanding how education can be transformed from one focused on acquiring information to one concerned with cultivating cultural awareness. Facilitating this move, Vygotsky's (1978) sociocultural perspective on learning provides a framework for the first generation of CHAT. In his response to the positivist behavioural assertion of a simple relationship between stimulus and response, Vygotsky emphasises that learning is mediated by culture - which in turn is shaped by individual agency. In other words, Vygotsky understands children's development as shaped by their social interactions with adults and peers. Here, learning is seen as occurring as children engage in purposeful activity with others who possess more knowledge about the task at hand.

Vygotsky's colleague Leont'ev (1981) and others, such as Il'enkov (1977, 1982) and Davydov (1988, 1990), subsequently developed the second generation of CHAT. In Leont'ev's conception, the unit of analysis is the group instead of the individual subject. Il'enkov (1977, 1982) then incorporated Marxist ideas about dialectics and contradictions into CHAT by suggesting that internal contradictions are the driving force for change and development within an activity. Finally, Davydov (1988, 1990) translated Il'enkov's dialectical theories of learning into classroom-based teaching strategies, introducing the movement from the abstract to concrete via steps in which students engage and respond actively with their environment.

In the 1980s, Engeström (2001, 2014) took up Leontiev's CHAT and applied it to learning in organisations. One of the forces driving the development of this third generation of CHAT has been a growing recognition that cultural diversity (Cole, 1988, Griffin, 1984) results in varied ways to accomplish tasks - and can, therefore, affect definitions and perceptions of any given task as well as its relation to other tasks and activities. The third generation of CHAT also provides a way to integrate the individual and social levels of analysis: individuals are seen as having varying capacities to engage in different kinds of activities (e.g., cooking or composing music), but their ability is constrained by what is available in the environment (e.g., utensils or instruments) and by rules that govern behaviour (e.g., those governing musical performance).

Going further, Engeström's (2001, 2014) expansive learning theory helps us understand how to create spaces where students can learn from one another's experience, and where educator and students can develop new knowledge together. This is facilitated, as Gutierrez (2008) suggests, when educator and students co-construct a third space, where each brings their knowledge to bear. Here, both educator and students' diverse cultural backgrounds, discourses and knowledges become resources for mediating learning. In this way, Engeström and Gutierrez challenge us to create spaces in the classroom for students and educator alike to learn about themselves and each other.

Taking up this challenge, in contrast to traditional Western teaching methods, theatre - and African Storytelling as an early form of theatre - opens a space to afford both educator and students first-hand engagement with taken-for-granted socio-political attitudes, norms, and values. Theatre makes it possible for educator and students, as members of the audience, to contribute to the performance. To put it another way, with theatre there is an actor-audience collaborative relationship. Theatre presents a space where educator and students are personally involved while simultaneously being removed enough from their own ethnocentric perspective to be able to engage critically (Haselau & Saville Young, 2022). Film and television, or even YouTube plays, do not have this facility as the performance in these formats is fixed rather than interactive. As a result of theatre's relational, interactive, and collaborative nature, it has the potential to facilitate educator and student understanding, as well as to stimulate the processing of information around complex topics involving power, oppression, interpersonal relationships, and individual subjectivity. This active engagement can be further enhanced, post-performance, through a series of educator facilitated discussion groups. Creating a third space in the classroom where educator and students can think critically about the social norms and values portrayed in the performance, helping students develop a better awareness of how power relationships affect people's (as citizens) thoughts, feelings, and actions.

Freire's (2018) critical pedagogical approach advocates students developing a critical consciousness towards learning by engaging in self-directed inquiry. Such active engagement empowers students to view themselves as citizens and agents, dispelling the misperception that they are isolated from their socio-cultural communities, or are unable to effect change. Theatre, as a critical pedagogical strategy, aligns with these goals, for, as Jackson (1 993: 35) points out,

Any good theatre will of itself be educational - that is, when it initiates or extends a questioning process in its audience, when it makes us look afresh at the world, its institutions and conventions and at our own place in that world, when it expands our notion of who we are, of the feelings and thoughts of which we are capable, and of our connection with the lives of others.

Utilising theatre as a critical pedagogical strategy, therefore, aligns with contemporary constructivist models of teaching and learning. According to Pammenter (1993: 59),

Theatre, at its best, is the communication and exploration of human experience; it is a forum for our values, political, moral and ethical. It is concerned with the interaction of these values at a philosophical, emotional, and intellectual level.

Incorporating theatre as a critical pedagogical strategy in postgraduate psychological education enables students not to be passive recipients of facts, but as agents of their own learning. In other words, theatre does not just focus on the transmission of information, but rather on exposing students to a variety of contexts and situations to help them actively and critically engage in knowledge construction.

Let us now look at how theatre, as a critical pedagogical strategy, can be employed in a postgraduate psychology education. While the context of my use of theatre is in an institute of higher education in South Africa, the activity could also be offered as a short course for qualified clinicians engaging in continuing professional development anywhere in the world. It is recommended that 36 education hours be given to the activity.

PROCEDURE

In terms of a procedure to integrate theatre into postgraduate psychological education, the following steps may be used as a guide:

1. A first step is for students and educator to explore the development and socio-political background of theatre within their community.

2. Any resultant journal articles and texts can be circulated between the students and educator. These readings make up the resources for the module.

3. The reading resources are used as starting points in a series of educator facilitated discussions around the relationship between theatre and the local (historical) socio-political climate.

4. Following this series of discussions, educator and students attend a production of a local play, rich in socio-political context. A useful interdisciplinary move would be to attend a production in the drama department of the tertiary institution in which your postgraduate programme is situated. Such a move ensures relevance of subject matter and performance, promotes interdisciplinary collaboration, is practically accessible, and cost effective. If this is not possible, your local community theatre company (either amateur or professional), or high school, can provide useful alternatives.

5. Students are then asked to write a reflective essay exploring how the play impacts them. It is important to highlight to students that there are no 'right' or 'wrong' responses. The following questions can be used as a guide to reflection:

• What do you imagine are the playwrights' intentions in writing this play?

• What socio-political context is the playwright writing from?

• Briefly describe the characters, their relationships, and conflicts (internal/external/interpersonal)

• How are socio-political categories such as race, age, gender, and class engaged with in the play?

• What are the play's themes and messages?

• Describe the play's set, props, and costumes and suggest what their use might communicate to the audience.

• What is the relevance of the play, in terms of when it was written, and the current socio-political climate?

• By engaging and reflecting on the play in this manner, what have you learnt about the impact of your own socio-political context on you?

6. Returning to the classroom, the educator - acting as facilitator - encourages each student to discuss their reflective essay with the rest of the class. The class looks at any similarities or differences that may emerge between their essays, as well as any insights gained. Students can elaborate on the tools they used to immerse themselves in the character's life. For example, with a performance analysis is a tool an actor uses during the text-analyses of a play. Here the actor creates a character profile where he or she finds common threads and differentiates his or her socio-political background to the character.

Often during this process, the actor also needs to find a commonality which they share with the character, in order to create a truthful performance. The aim of the performance analysis is to engage with selfhood and positioning of self in the world.

7. The class then selects socio-politically contentious aspects of the play to perform role plays, with students taking on various characters (see Auld, 2022c for further information on role play as a pedagogical strategy to assist students engage with the social embeddedness of trauma). This allows students to further grapple with and reflect on the taken-for-granted socio-political attitudes, norms, and values.

8. Next, the class is divided into groups of three and asked to devise a three-minute short 'trailer' for the play. The aim of this activity is for students to distil out the central themes. The students then perform, and video record, this trailer, before sharing it with the rest of the class.

9. Students take turns to be in the 'hot seat', as the character they portray. They are interviewed by their peers to further explore, and make explicit, the character's social embeddedness.

10. After the filming of the trailer, and taking the hot seat, the students are given an opportunity to reflect on their experience. Each student is asked to write another short reflective essay - this time specifically about the socio-political attitudes, norms, and values impacting the character they portray. These 'writing-in-role' essays are shared with the class during class discussion time.

11. If time allows, the whole procedure may be repeated with a new socio-politically rich play.

Anecdotal illustration

1. Example of background research

Closely associated with the work and theories of Freire, Augusto Boal, the Brazilian theatre practitioner, drama theorist, and political activist, has been influential in South African theatre and society. Of particular interest, Boal's work on conscientisation through theatre, and his ideas regarding the utilisation of theatre for socio-political purposes, have been very influential in the shaping of the protest theatre movement of the 1 960s, 1 970s and 1 980s, as well as the more socially conscious community work of the 1990s. The English version of his first book, Thieafre of he Oppressed (Boal, 1985), influenced many South African theatre practitioners and theorists during the struggle against apartheid, while his later handbook, Games for Actors and Non-Actors (Boal, 2002), has become an important tool in the post-apartheid period.

Drawing on Boal, Athol Fugard - born in Middleburg, South Africa, in 1 932 - is a playwright, novelist, actor, and director, who is widely regarded as one of South Africa's greatest playwrights. Fugard often draws on his own personal experience as inspiration for his work. For example, during apartheid, Fugard was friends with prominent local anti-apartheid activists and, as a result, Fugard and his family were placed under government surveillance for many years. His passport was confiscated by the authorities, and he was prevented from travelling abroad. The apartheid government gradually, over time, increased its restrictions on his work and freedom of movement, finally banning the publication and performance of his plays. Some of these personal experiences and events are reflected in this play, Sorrows and Rejoicings ( Fugard, 2002).

2. Example of a trailer

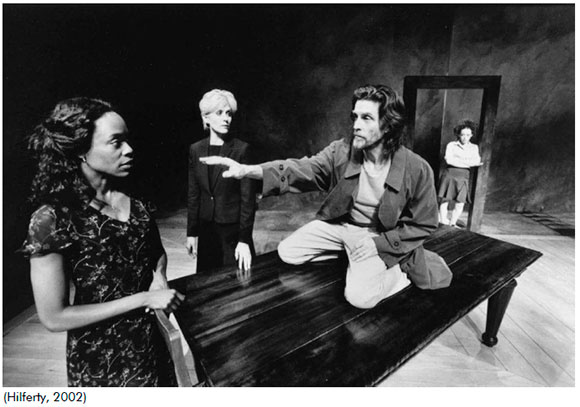

Fugard's play, Sorrows and Rejoicings, explores the legacy of South Africa's policy of apartheid on three women - one classified as 'white', one 'black', and one 'coloured'. Initially, it appears that these women have little in common, except for their connection to one man, a white poet named Dawid. The three women meet in a small Karoo village after Dawid's funeral. The white woman, Allison, was

Dawid's wife, while the black woman, Marta, was his former lover and is the mother of their coloured child, Rebecca. Dawid, despite loving the Karoo village in which he grew up, was driven into exile because of his anti-apartheid activism. He appears to the audience only in flashbacks as the women share their memories of him, confronting their misunderstandings and resentments, as well as the shackles that have been handed down to them from the past, managing to connect and reconcile in the present, with the hope of moving on in the future.

3. Example of a student's reflective essay

Sorrows and Rejoicings is set in the late 1 990s - just before the turn of the century - in a post-apartheid South Africa. Under apartheid, almost every aspect of life in South Africa was specified and regulated -from where you might live and work, to whom you might relate to and how. Establishing links with others during apartheid was, therefore, severely curtailed: Black people were not allowed to associate with white people, and vice versa, and this separation is evident in the play. During apartheid, Dawid has a child, Rebecca, with Marta and, because of this illicit relationship, Dawid must constantly disassociate himself from his daughter. This is conveyed when Allison says (Fugard, 2002: 29),

And then when I saw little Rebecca - I think she was already about one year old - I knew for sure. Poor Dawid! He made it so obvious by deliberately ignoring the child when she was in here with you.

Race and racial divisions, therefore, play a major role in Sorrows and Rejoicings. Apartheid resulted in Dawid having to leave Marta and Rebecca. Due to the segregation of the different races, Dawid went on to marry Allison, a white English woman. Allison highlights the white privilege that resulted from apartheid when she says to Marta (Fugard, 2002:,31), 'Had I got him, like so many other things in my life, because in addition to all my other splendid virtues, I had white skin?'

The title of the play contains the nouns 'Sorrows' and 'Rejoicings', which are, in many ways, polar opposites. Symbolically, the split between 'Sorrows' and 'Rejoicings' echoes the imposed divisions of apartheid - the separation of South Africa into two racist categories, black and white. On one hand, 'Sorrows' is a reference to the Latin poet, Ovid's, letters - Trista meaning sorrows (Ovid, 1 924) - written during his exile from Rome by the Emperor Augustus. On the other hand, 'Rejoicings' is reference to the title Dawid chose for his poetry anthology (to be written during his exile from South Africa). In terms of 'Rejoicings' Dawid hopes that his exile will offer a chance for him to come to life, and find his voice, after being stifled by the repressive apartheid regime. 'Rejoicings' symbolises Dawid's hope to make a difference to South Africa's future generations. Unlike Ovid's 'Sorrows', Dawid's 'Rejoicings' are meant to celebrate his newfound freedom and hope in London. Unfortunately, Dawid's hope for the future ends as the legacy of apartheid lives on in him: He feels he has lost his soul, being removed from the land he loves so much. He finds life in London to be the opposite of what he has envisioned - he experiences it as soulless and alienating. This is seen by the various memories of Dawid's life voiced by the women in the play. Unfortunately, the division of 'Sorrows' and 'Rejoicings', does not allow for diversity and collaboration. By focusing on 'Rejoicings' Dawid does not engage with life's complexities, and, therefore, reconcile his pain and sorrow, gain the ability to mourn loss, and move on.

The division and separations brough about by apartheid are also reflected symbolically using language. An example of this is the pronunciation of 'Dawid'. During apartheid Afrikaans was regarded as the language of the oppressor. In Afrikaans, the poet's name is pronounced 'Dawid'. However, in English, his name is pronounced as 'David'. Allison prefers to call Dawid by the English pronunciation, whereas Marta calls him Dawid. These different pronunciations reflect the differences between the two women and make the divide between them seem even greater.

The play, although written in 2002, resonates with issues still encountered in the lives of many South Africans. In both South Africa and many other parts of the world where divisive social systems, and the resultant trauma, have impacted the social unconscious, leaving a transgenerational legacy. The play encourages people to take a stand against prejudice, not just by protesting and acting out, but by talking and connecting. In post-apartheid South Africa, sorrow clings to all South Africans. We are still facing the aftermath of this divisive social system, slumbering in the social unconscious only to flare up at the slightest provocation. Themes of resentment and violence come up at multiple points in the play, as they do in day-to-day life in post-apartheid South Africa. For example, Rebecca feels a deep resentment towards her father, as he abandoned her mother and herself and 'ruined their life'. Rebecca is violent in her burning of Dawid's poems, which were an important emotional connection between her mother and father during apartheid.

Another aspect of socio-political trauma is revealed through the play's critique of patriarchy. Women in the play are depicted as strong, complex, and capable of forgiving a man who, ultimately, cannot forgive himself. Opposingly, the only man in the play, Dawid, is portrayed as two dimensional and extreme - he is either full of life and ideas, striving for ideals, or he completely falls apart, full of shame and inadequacy, becoming an alcoholic. Dawid is unable to reconcile life's sorrows and rejoicings while the female characters, although flawed, can open to one another, see past sorrows, and grasp the possibility of rejoicing despite this pain.

The trauma of betrayal is also a pinnacle theme. Dawid has a history of betraying women - leaving and abandoning both Marta and Rebecca. He also betrays and abandons Allison by drinking, not supporting her career, by losing his job, and returning to South Africa without telling her. He also betrays his own ideals - he wanted to go to London to find his voice and use it to save South Africa, however, he soon loses sight of his goal and falls into alcohol abuse to dull his sorrows.

The actor-audience relationship is intimate, causing the character's socio-political struggles to affect the audience personally. The entire play is set in the living room of a family home in the Karoo, which traditionally is a place for a family to come together. The Karoo is also a stripped land and, therefore, stripped decor also allows the audience to focus even more intently on the characters in the play. When a character speaks, they generally engage in emotional monologues. This has the effect of drawing the audience in and making us aware of the characters inner world, hopes, dreams, and desires. In so doing the audience has a deep and personal attachment to the characters. The actors use no over the top facial expressions, so the acting is natural and relatable. In terms of props and set design, symbolically, a table represents the coming together of people to share in communion around food. However, in apartheid South Africa citizens were split apart. The table, therefore, within this sociopolitical context represents, the divide in South Africa.

I believe that Fugard's intentions in writing this play are to demonstrate the transgenerational legacy of apartheid and how this impacts people at an individual, family, and social level. As the play unfolds in the post-apartheid period, the main characters, Marta, Allison, Dawid, and Rebecca represent the disconnection, misunderstanding, alienation, and resentment that has built up and been passed on during apartheid. With Rebecca, a sullen and impotent figure in the doorway of the living room for most of the play, there is the ominous sense of the legacy of apartheid - violence and resentment -blocking the door and preventing future possibilities. However, the end of the play is hopeful with Rebecca's confrontation of this legacy within herself, after listening to the testimony of Allison and Marta. Ultimately, Rebecca comes to realise that through connecting with others, opening herself up to understand where these two older women are coming from, as well as the sorrows and rejoicings they have lived through, there is hope for communion and creativity in the future.

CONCLUSION

Given that prejudice and prejudgements govern and limit our formulation of experience, such taken-for-granted socio-political attitudes, norms, and values are an integral part of who we are, and therefore, cannot be ignored when we understand the other (Bhattacharya & Kim, 2018). In other words, everyone holds prejudices and discriminates against people who are perceived as different from them. These prejudices influence both our conscious thoughts and unconscious assumptions about other people, as well as the ways in which we interact with them (Esprey, 2013). Fonagy and Higgitt (2007) and Straker (2006) suggest that, just as our early relationships shape our attachment styles and relational patterns, so too are we shaped to take on specific roles when interacting with others. Unless we cultivate a consciousness that liberates us from these roles, we are likely to remain trapped within them (Love, 2013). Drawing on the play, Sorrows and Rejoicings, there is no getting away from the ghosts of the past. As the play illustrates, you carry them within you. We need to engage with these ghosts to alleviate some of the bitterness of the present - a process which has both personal and political dimensions. In terms of a way forward, unlike positivist thinkers, we need to incorporate prejudice into our understanding of selfhood - rather than trying to avoid it - to enable us to view life as complex and multi-layered, and open the door to the possibility of change and growth in the present and future (Bhattacharya & Kim, 2018).

Important arguments by critical scholars such as Boyle (2022), Bracken et al. (2016), Fanon (1986), Frosh (2018), Laclau and Mouffe (1988) have led to calls for a decolonial stance to postgraduate psychological education. To accomplish this, Mathebane and Sekudu (201 7), working within the South African context, advocate inculcating critical awareness of the impact of taken-for-granted sociopolitical attitudes, norms, and values on subjectivity. In other words, we - as educators - need to develop critical pedagogical strategies-to explore how narratives - the stories told to make sense of experience - are derived from wider cultural narratives. Such initiatives must highlight how some ways of understanding and experiencing the world are more accessible and socially endorsed than others.

We need pedagogical strategies which enable us to explore how we compare ourselves against prevailing social discourses, resulting in social shame when we fail to attain socially prescribed ideals (Boyle, 2022, Layton, 2007). These initiatives need to help us trace how socially stigmatised and undesirable aspects of self can be defensively split off and projected, at both an individual and social level (Jaques et al., 1955, Menzies-Lyth, 1992), onto others. In other words, as Layton (2007) points out, we need educational tools to help us reflect on how each society has its own socially embedded sense of acceptable ways of thinking, feeling, and behaving. Such taken-for-granted socio-political attitudes, norms, and values then set the unquestioned parameters about who and what is deemed good/desirable/healthy. Through such pedagogical strategies we can develop an awareness within postgraduate psychological education of how behaviours and experiences that do not correspond to the socio-political norms and values of a given culture can lead to feelings of anger, hatred, and resentment for some, as well as shame, embarrassment, and humiliation for others.

As a critical pedagogical strategy, theatre provides students with first hand engagement with taken-for-granted socio-political attitudes, norms, and values. In the illustration, Sorrows and Rejoicings, we can see how theatre's relational, interactive, and collaborative nature can fully engage the student, creating a space where they can think critically about the norms and values portrayed in the performance. The illustration also highlights how students can reflect on themselves as citizens who are embedded in their socio-cultural communities. In this way, theatre, as a critical pedagogical initiative, aligns with contemporary constructivist models of teaching and learning, where students are not passive recipients of facts, but rather agents of their own learning. How theatre strategies can be applied to the different levels of postgraduate psychological education, will be the subject of my next study in this area.

For psychological practice to be relevant to non-Western cultures within the Global North and Global South, institutes of higher education have an ethical responsibility to take a decolonial stance and foster critical awareness of the ideological underpinnings of psychological theories, research, and knowledge production. In non-Western cultures, such as South Africa, postgraduate psychological education must consider the multicultural and resource-constricted context in which we operate. While universities that offer advanced education in psychology are aware of the need for contextual models, because of the dominance of positivism, Western approaches are idealised and held up as best practice. Such approaches separate the mind from the body, the individual from the social group, removing values, ethics, and power interests from theory and practice (Boyle, 2022). Blindly accepting these universal assumptions can lead educators, students, and clinicians to view patients as passive objects instead of active agents who create meaning within their socio-political context. This can perpetuate cycles of abuse for patients and leave students feeling inadequate and insufficient in their skills.

The political landscape, cultural differences, and the effects of economic hardship are just some aspects we must consider when understanding emotional distress and suffering, to be effective practitioners. By discussing the psychosocial causes of distress - such as racism, sexism, and engineered inequality - we can facilitate critical awareness, opening the possibility of finding ways to address unspoken issues within and between racial groupings that have arisen out of the traumas born in a racially haunted history. Many other themes in Fugard's (2002) Sorrows and Rejoicings are also relevant in today - the absent father figure and the impact thereof on households, for instance. Although we need to be reminded of a colonial and segregated past, we also need to be sensitive to the current issues of poverty and inequality experienced by all races in South Africa. Therefore, the role of psychology in the future of this country could also include the healing of polarised societies using theatre pedagogies.

REFERENCES

Akhtar, F. (2012) Mastering Social Work Values and Ethics. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. https://www.perlego.com/book/952219/mastering-social-work-values-and-ethics-pdf [ Links ]

Alkin, M.C. & Christie, C.A. (2002) The use of role-play in teaching evaluation. American Journal of Evaluation 23 pp.209-218. [ Links ]

Auld, S. (2022a) Autoethnography as a Pedagogical Tool for Developing Culturally Situated Psychotherapeutic Practice Critical Arts pp.1-20, doi:10.1080/02560046.2022.2116467

Auld, S. (2022b) Case-based learning as a pedagogical strategy to explore the social embeddedness of trauma. 145igital 2022 - International conference on Teaching, Assessment and Learning in the Digital age. Umhlanga: South Africa. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/366733432_digiTAL_2022_Conference_Proceedings

Auld, S. (2022c) Role-play as a pedagogical strategy to assist postgraduate psychology students engage with the social embeddedness of trauma. Critical Arts pp.1 -20, doi: 10.1080/02560046.2022.2143832

Baldwin, J. (1985) The Price of the Ticket: Collected 1948-1985, London: St Marin's/Marek. https://books.google.co.za/books?id=05C3xwEACAAJ [ Links ]

Bhattacharya, K. & Kim, J.-H. (2018) Reworking Prejudice in Qualitative Inquiry With Gadamer and De/Colonizing Onto-Epistemologies. Qualitative Inquiry 26 pp.1174-1183, doi: 10.11 77/1077800418767201 [ Links ]

Boal, A. (1985) Theatre of the oppressed. New York: Theatre Communications Group. [ Links ]

Boal, A. (2002) Games for Actors and Non-Actors. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Boyle, M. (2022) Power in the power threat meaning framework. Journal of Constructivist Psychology 35 pp.27-40, doi: 10.1080/10720537.2020.1773357 [ Links ]

Bracken, P., Giller, J.E. & Summerfield, D. (2016) Primum non nocere. The case for a critical approach to global mental health. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences25 pp.506-510. [ Links ]

Butchart, A. & Seedat, M. (1990) Within and without: Images of community and implications for South African psychology. Social Science & Medicine 31 pp.1093-1102. [ Links ]

Butler, J. (1990) Gender trouble : feminism and the subversion of identity. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Cole, M. (1988) Cross-cultural research in the sociohistorical tradition. Human Development 31 pp.137-157. [ Links ]

Dalal, F. (1998) Taking the group (really) seriously. Race, racism and group analysis. Group Analysis 34, doi: 10.1177/05333164211041549 [ Links ]

Davids, M.F. (2020) Internal racism: A psychoanalytic approach to race and difference, London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [ Links ]

Davydov, V.V. (1988) Problems of developmental teaching: the experience of theoretical and experimental psychological research: excerpts. Armonk, North Castle, NY: M.E. Sharpe. [ Links ]

Davydov, V.V. (1990) Types of generalization in instruction: logical and psychological problems in the structuring of school curricula. Soviet studies in mathematics education. Reston, VA: National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. [ Links ]

Duncan, N. (2008) Understanding collect violence in apartheid and post-apartheid South Africa. African Safety Promotion: A Journal of Injury and Violence Prevention 3, doi: 10.4314/asp.v3i1.31620 [ Links ]

Engeström, Y. (2001) Expansive learning at work: Toward an activity theoretica reconceptualization. Journal of Education and Work 14 pp.133-156, https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080020028747 [ Links ]

Engeström, Y. (2014) Learning by Expanding: An Activity-Theoretical Approach to Developmental Research. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139814744 [ Links ]

Esprey, Y. (2013) Raising the colour bar: Exploring issues of race, racism and racialised identities in the South African therapeutic context. In C. Smith, G. Lobban & M. O'Loughlin (Eds.) Psychodynamic psychotherapy in South Africa. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. [ Links ]

Fanon, F. (1986) Black skin, white masks, London: Pluto. [ Links ]

Fonagy, P. & Higgitt, A. (2007) The development of prejudice: An attachment theory hypothesis explaining its ubiquity. Lanham: Jason Aronson. [ Links ]

Foster, D. (1989) Political detention in South Africa: A sociopsychological perspective. International Journal of Mental Health 18 pp.21 -37. [ Links ]

Foulkes, S.H. (1964) Therapeutic group analysis / by S.H. Foulkes. London: Allen & Unwin. [ Links ]

Foulkes, S.H. (2018) Therapeutic group analysis. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Freire, P. (2018) Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Bloomsbury publishing USA. [ Links ]

Freire, P. & Ramos, M.B. (1970) Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Herder and Herder. [ Links ]

Fromm, E. (2001) Beyond the chains of iilusion: My encounter with Marx and Freud. New York: A&C Black. [ Links ]

Fromm, E. & Funk, R. (201 7) Beyond the chains of iilusion : my encounter with Marx and Freud. New York: Bloomsbury Academic USA. [ Links ]

Frosh, S. (2018) Born with a knife in their hearts: transmission, trauma, identity, and the social unconscious. In E. Hopper (Ed.) The Social Unconscious in Persons, Groups, and Societies. London: Karnac, doi: 10.4324/9780429483240-1 [ Links ]

Frosh, S., Phoenix, A. & Pattman, R. (2002) Young masculinities: Understanding boys in contemporary society. Basingstoke: Palgrave. [ Links ]

Fugard, A. (2002) Sorrows and Rejoicings. New York: St. Paul MN. [ Links ]

Gibson, K. (1989) Children in political violence. Social Science & Medicine28 pp.659-667. [ Links ]

Griffin, P. & Cole, M. (1984) Current activity for the future: The Zo-ped. New Directions for Child and AdolescentDevelopment23 pp.45-64, doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/cd.23219842306 [ Links ]

Grosfoguel, R.A. (2009) A decolonial approach to political-economy: Transmodernity, border thinking and global coloniality. Kult 6 pp.10-38. [ Links ]

Gutierrez, K. (2008) Developing Sociocritical Literacy in the Third Space. Reading Research Quarterly -READ RES QUART' 43, doi: 10.1598/RRQ.43.2.3 [ Links ]

Haraway, D. (1988) Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective. Feminist Studies 14 pp.575-599. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3178066 [ Links ]

Hart, A. (2020) Principles For Teaching Issues Of Diversity In A Psychoanalytic Context. Contemporary Psychoanalysis 56 pp.404-417, doi: 10.1080/00107530.2020.1760084 [ Links ]

Haselau, T. & Saville Young, L. (2022) Co-Constructing Defensive Discourses of Service-Learning in Psychology: A Psychosocial Understanding of Anxiety and Service-Learning, and the Implications for Social Justice. Teaching of Psychology pp. 1 64-174, doi: 10.1177/00986283221077206

Hilferty,S. (2002) Susan Hilferty. https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.susanhilferty.com%2Fshows%2Fsorrows-and-rejoicings130%2F&psig=AovVaw2CwAFJWHzkG90ddubBZXur&ust=1681452043961000&source=images&cd=vfe&ved=0CBMQjhxqFwoTCKi0oZCXpv4CFQAAAAAdAAAAABAE (Accessed 13 April 2023).

Hopper, E. (2002) The Social Unconscious: A Post-Foulkesian Perspective. Group Analysis 35 pp.333335, doi: 10.1177/05333160222078143 [ Links ]

Il'Enkov, É. (1977) Dialectical logic: Essays on its history and theory. Moscow: Progress Publishers. [ Links ]

Il'Enkov, É. (1982) The dialectics of the abstract and the concrete in Marx's Capital. Moscow: Progress Publishers. [ Links ]

Ingleby, D. (1988) Critical psychology in relation to political repression and violence. International Journal of Mental Health 17 pp.16-28. [ Links ]

Jackson, A. (1993) Learning Through Theatre New Perspectives on Theatre in Education. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Jaques, E., Klein, M., Heimann, P. & Money-Kyrle, R.E. (1955) New directions in psychoanalysis. London: Tavistock. [ Links ]

Kagee, A. & Price, J.L. (1994) Apartheid in South Africa: Toward a model of psychological intervention. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling 17 pp.91 -99, doi: 10.1007/BF01407965 [ Links ]

Laclau, E. & Mouffe, C. (1988) Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics. London: Verso. [ Links ]

Layton, L. (2007) What psychoanalysis, culture and society mean to me. Mens sana monographs 5 pp.146-1 57, doi: https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-1229.32159 [ Links ]

Leont'ev, A. (1981) Problems of the development of the mind. Moscow: Progress. [ Links ]

Lo, I. & Diop, A. (2022) Issues of identity in Michael Ondaatje's "The English Patient" (1992) and "Anil's Ghost" (2000). Akofena 4 pp.265-280. [ Links ]

Lobban, G. (2013) Subjectivity and identity in South Africa today. In C. Smith, G. Lobban & M. O'Loughlin (Eds.) Psychodynamic psychotherapy in South Africa. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. [ Links ]

Love, B.J. (2013) Readings for diversity and social justice. New York: Routledge. https://search.library.wisc.edu/catalog/9910150102702121 [ Links ]

Lykke, N. (2010) Feminist Studies: A Guide to Intersectional Theory, Methodology, and Writing. New York/London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Mathebane, M.S. & Sekudu, J. (201 7) A contrapuntal epistemology for social work: An Afrocentric perspective. International Social Work 61 pp.1154-1168, doi: 10.11 77/002087281 7702704 [ Links ]

Menzies-Lyth, I. (1961) The Functioning of Social Systems as a Defense Against Anxiety. Human Relations 13 pp.95-121. [ Links ]

Menzies-Lyth, I. (1992) Containing Anxiety in Institutions: Selected Essays. London: Free Association Books. [ Links ]

Mills, C. (201 4) Decolonizing global mental health: the psychiatrization of the majority world. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Mohutsioa-Makhudu, Y.N.K. (1989) The Psychological Effects of Apartheid on the Mental Health of Black South African Women Domestics. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development 1 7 pp.134-42. [ Links ]

OVID. (1924) Tristia ExPonto, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Pammenter, D. (1993) Devising for TIE. London: Routledge [ Links ]

Punamäki, R.-L. (1988) Political violence and mental health. International Journal of Mental Health 1 7 pp.3-15. [ Links ]

Quijano, A. & Ennis, M.J. (2000) Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America. Nepantla: Views from South 1 pp.533-580. [ Links ]

Rustin, M. (2004) Why are we more afraid than ever? The politics of anxiety after Nine Eleven. I n The Pervesion of Loss. Philadelphia, PA, US: Whurr Publishers. [ Links ]

Sonn, C., Stevens, G. & Duncan, N. (2013) Decolonisation, Critical Methodologies and Why Stories Matter, doi: 10.1057/9781137263902_15

Stevens, G., Duncan, N. & Hook, D. (2013) Race, Memory and the Apartheid Archive: Towards a Transformative Psychosocial Praxis. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137263902 [ Links ]

Straker, G. (2006) The Anti-Analytic Third. The Psychoanalytic Review 93 pp.729-753. https://guilfordjournals.com/doi/abs/10.1521/prev.2006.93.5.729 [ Links ]

Swartz, L. & Levett, A. (1989) Political repression and children in South Africa: The social construction of damaging effects. Social Science & Medicine 28 pp.741 -750. [ Links ]

Tovani, C. & Moje, E.B. (201 7) No more telling as teaching: less lecture, more engaged learning. Portsmouth, NH : Heinemann. [ Links ]

Tummala-Narra, P., Claudius, M., Letendre, P.J., Sarbu, E., Teran, V. & Villalba, W. (2018) Psychoanalytic psychologists' conceptualizations of cultural competence in psychotherapy. Psychoanalytic Psychology 35 pp.46-59, doi: 10.1037/pap0000150 [ Links ]

Volkan, V.D. (1999) Psychoanalysis and Diplomacy Part II: Large-Group Rituals. Journal of Applied Psychoanayytcc Studies 1 pp.223-247, doi: 10.1023/A:1023252314892 [ Links ]

Volkan, V.D. (2001) Transgenerational transmissions and chosen traumas: An aspect of large-group identity. Group Analysis 34 pp.79-97, doi: 10.1177/05333160122077730 [ Links ]

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978) Mindinsociety: The development of higher psychological processes, Massachusetts. Harvard University Press, doi: 10.2307/j.ctvjf9vz4 [ Links ]

Weinberg, H. (2007) So what is this social unconscious anyway? Group Analysis 40 pp.307-322, doi: 10.1177/0533316407076114 [ Links ]