Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

The Independent Journal of Teaching and Learning

On-line version ISSN 2519-5670

IJTL vol.18 n.1 Sandton 2023

ARTICLES

An assessment of the employability of learners who attained their qualifications through recognition of prior learning in Botswana

Mishak Thiza GumboI; Sethunya Ludo SerefeteII; Reginald OatsIII

IUniversity of South Africa, South Africa

IIGaborone University College of Law and Professional Studies, Botswana

IIIUniversity of Botswana, Botswana

ABSTRACT

This study assessed the abilities and competencies of Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL) graduates in Botswana and their employability. Twelve participants identified from various RPL education and training fields, and hairdressing and beauty therapy services were interviewed. The findings indicate that RPL has overall life-shaping consequences for the learners involved and for this reason, it was highly embraced by participants; RPL gives learners access to post-school education, including other qualifications; RPL benefits learners and it is thus value for money invested by the Botswana Government. Therefore, the promotion of social inclusion should be embraced and adopted as a mode of assessment to capacitate human resource development in Botswana. The article concludes by recommending a partnership between Government and relevant institutions and organisations to audit skils in the country to uncover the unused skils, as wel as to design RPL that is relevant to the local needs.

Keywords: RPL, out-of-school education, training and development, human resource development

INTRODUCTION

The formal economy offers more opportunities for skills development, however, the informal economy equips informal workers with skills, especially through learning by doing (Gewer, 2021). The Conference on The World Declaration on Education for All held in 1990 in Thailand envisioned the universalisation of access to education for all children, youth, and adults. As a result, the Botswana Government developed policies to mitigate the barriers that its citizens face regarding educational access. The policies include the Revised National Policy on Education [RNPE] (1994), National Development Plan 9 2003/04-2008/09 (Republic of Botswana, 2003), and Republic of Botswana. (2016): Vision 2016. These policies created awareness about the citizens' knowledge and skills obtained through non-formal education, thus creating the demand for the potential of their recognition of learning in Botswana. As a matter of fact, the 1994 RNPE decrees the inclusion of non-formal and informal learning as part of lifelong learning in education and training.

Various countries have strived to implement Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL), mainly due to their commitment to non-discriminatory and inclusive practices related to access and equal education and training. For instance, Namibia has identified, as one of the key features of the National Qualifications Framework (NQF), the provision of opportunities for its citizens to gain qualifications through the recognition of competencies regardless of whether they were gained in formal, non-formal and informal settings (UNESCO, 2013). Namibia deems RPL important in this regard (UNESCO, 2013). It has also been observed that technical and vocational skills primarily emanate from informal apprenticeships in sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Latin America (Gewer, 2021). The scope of this article falls on sub-Saharan Africa and further on Botswana.

The Botswana Qualifications Authority (BQA) which was established under the Vocational Training Act No 22 of 1998, implemented the Botswana National Vocational Qualifications Framework (BNVQF); this happened before establishing the National Credit and Qualifications Framework (NCQF) as its core function in 2013. Through this establishment, the principles and processes of the RPL were introduced in 2006 into the country's education and training system. This responded to the mandate of Botswana Training Authority (BOTA) to promote access to vocational training, learning and skills development in all sectors of Botswana's economy. The BQA Act No 24 of 201 3 mandates the BQA to develop policies and criteria for RPL. The RPL policy was positioned in the setting of the National Human Resource Development Strategy (NHRDS), successive National Development Plans and other important government initiatives. The NHRDS (2009-2022: 14) stipulates that to build the country's strategic human resource potential, a platform should be created based on the current educational attainment level of the people, including the labour market in which they are employed. The NHRDS drew on a life cycle analysis, which pointed to the areas of concern in lifelong learning in Botswana where RPL would critically address the limited levels of opportunities, failure to appreciate that learning is a lifelong activity, absence of personal commitment, and lack of recognition of the need for self-development. This development creates a need to inquire into the systems that recognise RPL in Botswana, which are non-discriminatory.

As is the case in other countries, Botswana has, over the years, employed traditional methods to collect evidence of learners' performance such as examinations, tests, and other specially constructed assessment tasks. Mooketsi (2012) claims that such systems have, for a long time, been generally associated with formal modes of learning in that they tend to discriminate as they disregard knowledge and skills acquired in informal and non-formal settings. Hence, there was a need to transform the education system in the country by introducing RPL. However, RPL in Botswana is a relatively new concept with little research. Little is known about the process of RPL and how Botswana's institutions administer it. Despite the significant strides that the BOTA has made in developing and implementing the RPL system, since 2009 when RPL assessments were conducted in a number of indigenous fields of learning, no such assessment has been effected in any specialist or modern areas. According to the BOTA Statistical Bulletin (2012), the indigenous fields of learning where RPL assessments were conducted include basketry, traditional song and dance, leather craft, and pottery in the Okavango area. To date, no evaluation has been done on those assessments, nor an assessment of their impact on the stakeholders. The Botswana Government, through the BQA Act No 24 of 2013, has been fully advocating for the implementation of RPL not only for indigenous skills but also for a wide range of modern skills in different fields of learning. This called for a need to assess the influence of RPL in Botswana.

This study explored the processes of RPL in Botswana with a view to unearth the readiness of the RPL 'graduates' to execute abilities and competencies (to perform routine duties) in the workplace and the ultimate benefits of RPL to the education and training system of Botswana.

The following research questions become necessary when trying to assess the employability of learners whose qualifications were attained through RPL:

1. What is the RPL graduates' knowledge of RPL?

2. How ready are the RPL graduates to execute the abilities and competencies they have acquired in a workplace?

3. How beneficial is RPL to the education and training system in Botswana?

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

RPL was drawn from Kolb's (1984) experiential learning framework which is in turn informed by Dewey's learning cycle (Jeffs, 201 7). Kolb (1984) argues from a learning cycle perspective that people learn from their daily experiences of life. The Kolb learning cycle considers reflection as an integral part of learning; the process of learning follows a pattern that is based on four stages. These stages include concrete experience (i.e. having the actual experience), reflective observation (i.e. reflecting on the experience), abstract conceptualisation (i.e. learning from the experience), and active experimentation (i.e. trying out what has been learned) (McLeod, 2023). Experiential learning is the idea that experiences are generated through our ongoing interactions and engagement with the world around us, and learning is an inevitable product of experience (FutureLearn, 2021). This theory of learning differs from the cognitive and behavioural learning theories as it takes a more holistic approach. It considers the role that all of our experiences play in our learning, including our emotions, cognition and environmental factors (FutureLearn, 2021).

Experiential learning is typically about the observation of a phenomenon and doing something with it. This can happen through testing the action and interaction the purpose of which is either to learn more about it or apply a theory to obtain the desired result. Experiential learning in this study is a key principle through which to assess and recognise prior learning. According to Kolb's theory advanced by Jeffs (201 7), effective learning is determined by progressing through the four stages described above. Hence, the four stages are relevant in this study as they frame the understanding of the experiences of the participants, their learning from the training that they have undergone in the fields cited above, and the application of the competencies that they have acquired from the training.

The RPL process receives applications from individuals coming from diverse situations and experiences. For example, some of these people observed their elders working and later developed an interest and followed their passion without any schooling background. These learning styles have their advantages and contribute toward a holistic learning process. For instance, the Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu) (2000) has identified reasons for RPL in themes such as social justice, access to education and training, validating knowledge, personal and social empowerment, improving the education and training system, and job opportunities. This logic centres personal and social development within the education and training system. Regarding self-learning, individuals freely analyse their most efficient styles and identify the areas that they can improve in the process of learning. We also observed that the learners classified under RPL differ in their learning styles and habits.

LITERATURE REVIEW

An overview of RPL

RPL has emerged in recent decades as an important concept in education policy development. The European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training (Cedefop) (201 5) has since validated the identification, documentation, assessment and certification of an individual's learning outcomes acquired through non-formal and formal learning. The world's economy rests more on people from low-income groups (Palmer, 2020) the majority of whom are from developing countries (Gwer, 2021). These people have accumulated experience and acquired skills, hence a need to implement the RPL that would make them better people socio-economically. RPL is characterised by certain variations in practices, contexts, concepts, and conceptions such that it is also called Accreditation of Prior Experiential Learning or Recognition of Current Competency (Andersson, Fejes & Sandberg, 2013; 2016). From the beginning, RPL was viewed as an assessment process to formally recognise learners' prior learning and the competencies which they have acquired through informal and non-formal learning compared to the registered unit standards or learning outcomes in a specific qualification (Van Rooyen, 2003; Gray et al., 2004). This assessment system recognised that learning and acquisition of knowledge and skills may occur informally and non-formally at sites such as workplaces other than through the formal modes associated with formal education and training institutions (Andersson et al., 2013). An emphasis was placed on the learner's ability to demonstrate competence or produce evidence of his/her competencies against set standards or assessment criteria for a particular qualification or part of a qualification, irrespective of where, when, and how such competencies had been acquired. The learner was required to demonstrate the competencies that matched stipulated standards and assessment requirements for the target award or qualification.

RPL assessment processes were normally designed and implemented (Gray et al., 2004) for the participants to gain access to a course or job, credit for an award, or for promotion, or salary increase. Deller, Coetsee and Beekman (2007) categorised the RPL applications for:

• assessment to offer opportunities for the formal recognition of demonstrated experiential learning

• access to promote access to courses of study based on the learning acquired informally rather than the achievement of stipulated entry requirements

• awards and/or certification, a work-based learning system that considers the previous, current, or even planned experiential learning related to standards for a specific qualification

• diagnosis to help individuals to identify their learning achievements from work and previous learning experiences, skills gaps, or performance problem areas for training and development purposes

• progress to help disadvantaged groups to gain entry into higher programmes of study without emphasis on direct linkage to relevant academic standards.

As noted by Deller et al. (2007), RPL assessment, irrespective of intended purposes, required participants to demonstrate the competencies that match the specified learning outcomes and assessment criteria for such learning achievements to be considered worthy of credit. It was, therefore, imperative that there be clear RPL assessment requirements and criteria, policy, processes, and procedures, which were made public for the RPL to be implemented effectively for whatever purposes they can be considered. Self-esteem and professionalism among participants helped them to contribute at an organisational level. Andersson and Fejes (2012) conclude that RPL has valuable effects on its stakeholders.

Aggarwal (2015) conducted a study for International Labour Organisation (ILO) on RPL in which he postulated that RPL can improve inter alia employability, mobility, lifelong learning. According to Aggarwal (2015), encouraging lifelong learning can produce a competent and adaptable workforce that can stand the challenges of the current complex labour market, reduce the skills shortage gap, and develop holistically. In a way, RPL enhanced the skills portability of the migrant workers, fostered their mobility and employability, as well as created opportunities for them to get decent jobs or even self-employment. According to the South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA) (201 6), most institutions of higher learning in South Africa now treat RPL as one of the alternative ways to admit students. For instance, the University of South Africa (2023) indicates that experience could translate into subject credits within a qualification or direct access to undergraduate and postgraduate qualifications. This is also happening in other countries around the world. For example, in Australia, RPL starts with a person's training, apprenticeship, or traineeship, to grant him/her credit for the units in which he/she shows competence and reduce the time he/she would take to obtain the qualification (Queensland Government, 2014). Whilst acknowledging that the establishment of RPL procedures at the level of individual countries is embedded in a global diffusion process, such reforms are simultaneously shaped by the growth trajectories of each country's education system (Maurer, 2023).

A study by ILO (201 8) notes the benefits of RPL to both employees and employers, i.e. employers who have invested in their workers for a long time can advance their skills and experience for a particular job. Employers could take advantage of RPL to build on the educational profile of their employees and support the applicants to expand their employment prospects. With this, as the authors of this paper, we also saw the issue of cost efficiency emerging because of RPL. The ILO study (ibid.) also suggested that if RPL could be incorporated into education and training, a positive impact on the labour market, the country's economy, and society could be visible. Makeketa and Maphalala (2014), through a mixed-methods study, investigated the RPL's effectiveness and its impact on improving the lives of previously marginalised groups in the workplace in South Africa, using Eskom's Northern Region as a case study. Makeketa and Maphalala (2014) administered a questionnaire to a sample of employees and conducted interviews with three participants. The study revealed that RPL does exist in Eskom's workplace and efforts about its implementation can be traced; several milestones were achieved in the business in the region; there was still more to be done to realise the full and effective implementation of RPL; several gaps and challenges hampering the success of the RPL were identified, from building capacity to quality assurance (Eskom Academy of Learning, 2011).

The RPL benefits in Botswana's education and training system

The Botswana Government, through its plans and policies on education and training had maintained that all learning, regardless of how it was obtained, should be worthy of recognition and credit. BQA (2015) states that RPL critically adds to the mechanisms which enable the achievement of equity and acceleration to access education and training. Gray et al. (200) identified the benefits of RPL, focusing on employees and employers. Employee benefits may include the following: (i) they can access an award-bearing course, (ii) their informal non-formal learning is recognised toward acquiring credits and a qualification while employed, thus saving them time and money, (iii) a platform is created for them to negotiate their career development or progression, (iv) their personal development and growth are promoted, (v) their self-awareness, confidence, and self-esteem are boosted, and (vi) they can build on their previous experience so that replication of learning is prevented (Gray et al. 2004). The Sustainable Development Goals include a commitment to ensuring inclusive and equitable quality education and promoting lifelong learning opportunities for all (Goal 4), and the Education 2030 Framework for Action has called on countries to provide lifelong learning opportunities for youth and adults that encompass formal, non-formal and informal learning (United Nations, 2015).

Srivastava and Jena (2015) report that RPL can contribute toward equity by creating a platform for people to achieve qualified status and thus increase their qualifications and expertise. Srivastava and Jena (2015) also assert that individuals are increasingly required to have the necessary attributes to move and adapt to modern and changing times. Due to a lack of appropriate qualifications, a large proportion of learners face severe disadvantages in getting decent jobs, promotions and accessing further education, even though they might have the necessary knowledge and skills (Aggarwal, 2015). The RPL process can help such learners acquire a formal qualification that matches their knowledge and skills, and thus contributing towards improving their employability, mobility, lifelong learning, social inclusion and self-esteem. In the process, equity in recognition at work and other opportunities such as better remuneration and promotion can be realised. According to Bohlinger (201 7), the core idea of RPL is to promote, make visible and full use of the entire scope of learning results and (work) experience gained by an individual over the lifespan irrespective of where, when, and how the learning took place. Individuals, therefore, need to continuously learn from their experiences and contribute significantly to the operations of their organisations. The development of such attributes, as observed by Stephenson (1992) (Gray et al., 2004), requires the individual to manage his/her own learning, which is critical for RPL.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

The study adopted an interpretive paradigm to describe the worldview to inform the meaning of data (Chilisa & Kawulich, 2015). We believe that people construct and reproduce reality and knowledge through communication, interaction, and practice - we communicated (through interviews) and interacted with the participants to understand their views from a practice point of view as far as it culminated in their RPL. We mediated knowledge about the participants' reality through the research we conducted (Tracy, 2013). This is because, through interpretivism, we could describe the nature of the practices and experiences of our participants. Our aim was to strive to interpret reality as the participants understood and experienced their world. Epistemologically, we strived to understand how the participants acquired this reality (training) and the extent to which it was valid and limited (Chilisa & Kawulich, 2015) that could qualify them for RPL or not. These authors underscore that truth can be known through varied methodologies. Thus, the chosen methodologies were followed to achieve this.

BQA (2021) piloted the RPL in a few fields of learning from 2016 until 2018, as per its mandate to promote the uptake of RPL assessments in education and training providers. These fields included services (hairdressing and beauty therapy as the sub-field), education and training (early childhood education as the sub-field), building and construction (bricklaying as the sub-field), manufacturing, engineering and technology (welding and fabrication as the sub-field), and agriculture and nature conservation (livestock farming as the sub-field). Fifty (50) candidates were assessed by the Botswana Qualifications Authority through local institutions for RPL from which 12 participants were drawn for this study. These were candidates who were found in the capital city and its vicinity. Therefore, the study used purposive selection mainly to access relevant information for the study. This method was appropriate for this study because the candidates were geographically easily accessible and were from were representative of various fields such as hairdressing, building and construction, welding and fabrication and agriculture. Purposive sampling is the process of selecting a sample that represents a particular population (Gray et al., 2009). Data were gathered from the participants through in-depth semi-structured interviews to get a deeper and interpretation of their experiences and perspectives (Ritchie et al., 2013). The use of open-ended questions allowed the participants to relay more information and understanding of the subject matter. Data were recorded in a notebook during interviews.

Validity and reliability are critical aspects of any given research. Wallen and Fraenkel (2001) describe validity as the extent to which an instrument gives the information needed and reliability as its consistency. Validity was tested by a team of experts at Botswana University of Agriculture and Natural Resources, and the University of Botswana. The experts were asked to verify the readability, clarity, and coverage of questions in the interview guide. To determine reliability, a mock interview was conducted with two candidates who were not part of the 12 participants, so that we could establish the practicality and understandability of the interview. This is where we checked the understanding and ability to answer the questions, highlighting the areas of confusion and scrutinising any unforeseen errors, as well as estimating the average time the interview would take to complete.

To address ethical issues, we first sought ethical clearance from the University of Botswana's Office of Research and Development. Upon the granting of clearance, we sought permission for data collection from the Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Tertiary Education Skills and Development. The permission letters granted were used to introduce the study to the participants, its purpose, and the procedures used during data collection. The participants were not just persuaded into taking part in the study as their permission was also requested (Creswell, 2015). We asked for their permission and, by negotiating with them, protected their personal details in the interview sheets by treating them confidentially and anonymously. For this reason, names are not disclosed in reporting of the findings.

Data analysis

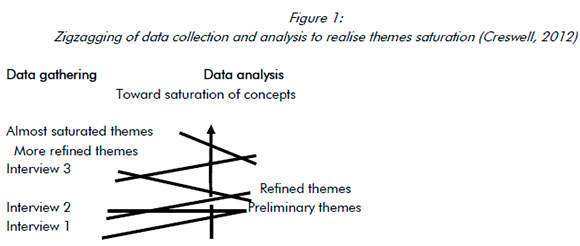

Thematic analysis was employed to describe how participants responded to the items raised in the interview guide. Data were split into bits, and the pieces were constructed together (Dey, 2005). The phenomena were described, and classified from the primary sources (participants), followed by tracing how the concepts were interconnected with each other. In essence, we transcribed, coded, and categorised the data and built the themes ultimately (Flick, 2014; Miles, Huberman & Saldana, 2014). We adopted traditional and modern analysis methods in which we used paper and pencil, and developed tables to enable data transcription, created minor categories of themes highlighting sections in different colours, and formed the main themes to answer the research questions. In summary, our data gathering, transcription, coding, categorisation, and thematic analysis zigzagged and involved constant comparative analysis methods (Creswell, 2012).

Figure 1 gives an indication of an in-depth interview through which data were collected, analysed from the preliminary categories, and we identified clues and refined the meanings of themes. This process forced us into a back-and-forth swing as shown in Figure 1. This way data were reduced and transformed to be more readily accessible, and understandable and to draw out various themes and patterns. Hence, for Berg (2004) data analysis in a qualitative study refers to data reduction, display and conclusions and verifications. After data have been collected, reduced and displayed, analytic conclusions began to emerge and define themselves more clearly and definitively.

FINDINGS

Knowledge and involvement of RPL

The background information on RPL was sourced from participants at the beginning of the interview sessions to ascertain if they had knowledge of RPL and whether they had ever been involved with RPL before. Participants were at first confused using the word RPL, even though all were subjected to the identification and assessment process. The analysis indicated that eight of them were knowledgeable about and had experience with RPL, while the other four had varied views, which include not knowing about RPL or not being sure what RPL was all about. One participant, a beneficiary of RPL, stated that BQA introduced him to RPL,

I did not know much before until the Botswana Qualifications Authority personnel visited me and indicated that they wish to take me for a short training after which I will be certificated.

The analysis revealed that the participants were experienced and skilled to a greater extent but needed formal recognition. Hence, one participant appreciated the government's training strategy. Referring to the skills and talents that one participant had, he said:

Yes, it is a strategy, so to speak, used by the government to identify us who hold certain skills or talents but had not gone for formal schooling.

Another participant knew about RPL and the opportunity it presented for her to acquire obtain a qualification,

for me, this is an opportunity for lifelong learning as it promotes alternate pathways to acquiring qualifications for us who somehow did not complete formal schooling. Currently, I am enjoying learning through this route more so that the government is taking us seriously now.

Improvement in career life after RPL

Participants were asked to reflect on their abilities and competencies after acquiring their qualifications through RPL and if there had been any improvement in their career life. Their views revealed that RPL had capacitated them in certain areas and that their career life had improved. The participants were confident that they could implement what they had learned. For instance, a participant who was an assistant teacher before could now develop worksheets and teach, a competency that she did not have prior to undergoing RPL.She now had her own class to teach,

I have my own class that I teach without being assisted and I am also respected.

Another participant had this to say:

Before being assessed, I was just an assistant teacher with no Early Childhood qualification, but now I have a qualification and I can apply for preschool teaching jobs advertised anywhere.

A participant who underwent training in the Hairdressing and Beauty Therapy subfield felt that she was already skilled, however,

having a certificate to show that I am a qualified hairdresser gives me dignity. I know my job and I can apply for a job at any hair salon.

Opportunity to upgrade qualification

The improvement of participants through RPL could take them even to higher education levels. It is in this sense that the analysis revealed that participants valued education as they stated that if given the opportunity to upgrade their qualifications to a higher level, they would do so. Thus, it was evident from the analysis that the participants realised the need for further education through progression to higher NCQF levels. One participant said in this regard:

I started hairdressing long before at home observing my elder sister. Later I worked in her salon; what I learned was recognised by the Botswana Qualifications Authority. After certification, my sister promoted me to a salon supervisor. As such, if I am given another chance to increase my qualification at a formal institution, I believe I can go high.

Along the same line, another participant said:

It is my desire to further my studies to get a higher qualification given that age is still on my side.

The participants hoped for the Government to support them financially in their training. This claim finds relevance in one participant,

to upgrade my qualification, I have applied to a local Brigade but due to financial challenges as a self-sponsor, I could not enrol. I wish the Government or Botswana Qualifications Authority could finance my training again.

Competency to perform duties

The participants were asked about their level of competency to carry out routine duties in their workplaces. Data analysis showed that they believed that having learned from their practical experience, they were competent to perform duties accordingly in the workplace. When asked how they were being monitored and evaluated at the workplace, one participant said,

Management assesses us and tells us where to improve and where we are doing well.

Another participant said,

As a hairdresser, my customers assess my work. They always tell me if they are satisfied with my work on their hair, and with that, I know I am very competent.

RPL as a necessity

The participants' views were gathered with respect to RPL as a critical necessity and imperative. The findings revealed that they embraced RPL as a necessity, except for one, who expressed a different view. To this participant, RPL was unnecessary. When probed for elucidation of his view, he responded:

Being in possession of a qualification certificate does not guarantee the ability to produce quality desired results. One can still achieve the best results in the workplace without a qualification certificate. Having acquired basic education is enough for me so far. With the kind of job I do, I can easily walk from one job to the next one in a day without any need for a certificate.

One of the participants who appreciated the need for RPL had a view that

being knowledgeable and skilled without a qualification certificate is heartache but having a certificate on its own makes life easier.

With that, it is evident that participants viewed RPL as a necessity. Some participants had not undergone formal education and training, but they were happy that their confidence had been restored through recognition of their skills.

DISCUSSION

In answering the research questions in this study, it is noticed that RPL has an overall life-shaping consequence for learners who participate in it. This is mainly in the form of access and equity. The participants demonstrated their knowledge and value of RPL in this regard. The findings show that RPL creates opportunities to access post-compulsory education and other qualifications, thus increasing social inclusion. RPL sets them at the door of such a level of education. For instance, looking at the designations of the participants' views, they continued with their line of work after being assessed and attaining qualifications. They were found in the pursuit of their specialisations and for that matter, others were ready to enrol with tertiary institutions to further their studies in those areas. This is a clear indication that RPL is embraced and that it should be adopted as a mode of assessment to affirm the learners' abilities and competencies. Clearly, the introduction of RPL promises those who did not qualify or were less qualified in the past greater inclusion in formal education and training (Rakometsi, 2014). The introduction of RPL anticipated it to be a mechanism for individuals to be confident, and for the formal learning system to recognise the knowledge and skills that individuals have acquired either through life or work experience. Indeed, in this article, participants attested to some level of abilities and competencies - they shared their experiences and reflected on what they were capable of, some even before undergoing RPL.

The central perception of RPL to be construed by participants who participated in this study was that of increased self-esteem in the workplace. Some participants in this study indicated increased self-esteem and recognition, therefore, they deemed this as the central effect of RPL. This supports Anderson and Fejes (201 2), who claim that the increased self-esteem and recognition of prior knowledge because of the effects of RPL in the workplace can be related to a more professional attitude and competence in the workplace. The introduction of RPL by Botswana Government promises to improve the lives of its people judging from the gains that participants have realised from the short training that led to their certification ultimately. The RPL programme did not only benefit the participants in their career lives but it benefited the Government as well as the programme yielded results - it is a good investment (and value for money) in changing the lives of its people.

According to the authors, a more professional attitude is closely related to an increase in self-esteem, producing a more professional attitude in the workplace. The findings of this study prove that nonformal education can be transformed into a tool that can restore dignity and recognition of people who are involved in the low levels of the job sector. Such employees can assume more responsibility in practice after RPL. Such a change in the workforce may be linked to the readiness of participants to perform routine jobs in the workplace and thus, renders them employable. In this study, we argue that RPL, if well supported by Botswana Government and private institutions can build an individual's confidence and self-esteem. The explicit development of the learner's identity could be engaged in this regard to support and motivate him/her to be determined to learn further. The emphasis on increased confidence and self-esteem is depicted in this study when the participants unanimously highlighted how their career lives changed after RPL and that now, they could perform their daily routines confidently. Indeed, the findings confirmed the benefits of RPL (Gray et al., 2004) to both the participants and the Government to a larger extent.

The findings categorically reveal that RPL is a beneficial assessment process in the education and training sector in Botswana (BQA, 2015) and that it should be adopted, promoted, and fully implemented. We learned from this study that the programme reflected the four aspects of Kolb's theory - participants' views revealed their concrete experience in their career fields, some prior to RPL and some after RPL, the study helped them reflect on their abilities and competencies, they conceptualised RPL and expressed their knowledge and experiences of it, and they enacted or implemented what they had learned. Berglund (2010) conducted a study focusing on the contribution of prior learning assessment to workforce development. The author noted that there has been a shift from company to company, from a focus on professional growth to personal growth (Berglund, 2010). The author also argued that RPL is a means of holistically combining professional and personal development. To this author, RPL encourages a more holistic conceptualisation of what learning is, who learners are, and how learning takes place. Berglund (2010) further argued that RPL may better enable the workforce to complete the transition from employment to employability. The findings showed that RPL can contribute immensely to the companies' competence and the employability of individuals. The findings revealed that some learners were absorbed in some workplaces.

The findings of this study imply that RPL has become an important tool through which many countries worldwide hope to support the prominence of lifelong learning, as well as to develop economic prosperity. The contribution of this study lies in the understanding that Botswana, being a developing context (Gewer, 2021) has embraced RPL to improve the lives of its people. A developing context presents a unique scenario considering the high employment rate and the large portion of the population being from low-income groups (Palmer, 2020). Botswana showcases how the situation can be turned around through RPL, something that other developing contexts can learn from. Though the initiative is in its infancy stage, the findings show that it is producing fruits already judging from the benefits the participants got from RPL. It is important to conceive of RPL as a lifelong learning programme for individuals to identify and verify their own achievements in learning throughout life (Boud, 2000). A lesson derived from this argument is that RPL should emphasise access to education and training. Also, resources should be used to open pathways for adult learners into higher education and support them.

RPL is an attractive and viable proposition to improve the relationships between the education and training provider with employers and the government with an aim to transform its learners and staff competence. We thus think that RPL could open opportunities in higher education to enrol scores of informally qualified, mature, and working adults. However, RPL should always be evaluated and improved especially in the developing context so that the pre-RPL abilities and competencies that individuals have cannot be compromised. The participant who did not see a need for RPL but wanted his abilities and competencies to be recognised through certification suggests diversification of RPL to cater to situations such as this.

CONCLUSION

This study shows that RPL graduates are knowledgeable in RPL, have abilities and competencies that engaging in RPL confirmed, RPL benefited them and the Botswana Government, and that the graduates are employable as such. The study indicates Botswana has implemented RPL as an attempt to improve the socio-economic lives of its people by putting them on a path for educational improvement and increasing their chances of employability. By so doing, Botswana recognises the enormous skills possessed by its citizens who attained their skills informally. RPL serves as a feasible strategy for skills development and capacity building in Botswana in an endeavour to produce enough well-equipped employees for its economic development. Education and training is a strong transformative force that can promote human rights and dignity, eradicate poverty, deepen sustainability and improve livelihoods. We thus advocate for the recognition and promotion of RPL as a tool to make an informally qualified workforce gain access to formal education. There is a need for the country, in partnership with relevant institutions and organisations, to conduct countrywide skills search with a view to uncovering the unused skills. This idea is triggered by literature, which widely reveals that RPL is central in the endeavour to produce employees who are knowledgeable, skilled, and have the requisite competencies to perform various activities. However, RPL in a developing context such as Botswana should not follow a traditional approach but must be sensitive to the dynamics of skills and talents that the citizens possess. With proper evaluation, RPL that is relevant to the context can be developed.

REFERENCES

Aggarwal, A. (2015) Recognition of prior learning: Key success factors and the building blocks of an effective system. Geneva: ILO. [ Links ]

Andersson, P. & Fejes, A. (2017) Effects of recognition of prior learning as perceived by different stakeholders. Prior Learning Assessment Inside Out pp, 1 (2). https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:570124/FULLTEXT02 (Accessed 3 May 2023). [ Links ]

Andersson, P., Fejes, A. & Sandberg, F. (2013) Introducing research on recognition of prior learning. International Journal of Lifelong Education 32(4) pp.405-411. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2013.778069 [ Links ]

Berglund, L. (2010) Assessment of competence at work: Bound to be tacit and not transferable? Adult learning in Europe - understanding diverse meanings and contexts. The 6th European Research Conference. Linköping, Sweden.

Bogdan, R. & Biklen, S. (2007) Qualitative research for education: An introduction to theories and methods (5th ed.). Boston: Pearson Education, Inc. [ Links ]

Bohlinger, S. (201 7) Comparing recognition of prior learning (RPL) across countries. In M. Mulder (Ed.) Competence-based vocational and professional education. Springer: Cham, pp.589-606.

Botswana Qualifications Authority (2021) Standards for Recognition of Qualifications. Gaborone: BQA.

Botswana Qualifications Authority (2015) RPL Impact Assessment Report. Gaborone: BQA.

Botswana Training Authority (2012) HIV/AIDS model policy for the vocational education and training institutions. Statistical Bulletin 7(1) pp.1 2-23. [ Links ]

Boud, D. (2000) Sustainable assessment: Rethinking assessment for the learning society, Studies in Continuing Education 22(2) pp.151 -167. [ Links ]

Cedefop. (2015) European guidelines for validating non-formal and formal learning. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Chilisa, B. & Kawulich, B. (2015) Selecting a research approach: Paradigm, methodology and methods. http://www.researchgate.net/publication/257944787 (Accessed 10 August 2022).

Creswell, J.W. (1998) Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among five traditions. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Creswell, J. (2012) Educational research: Planning, conducting and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th ed.). Boston: Pearson Education, Inc. [ Links ]

Creswell, J. (2015) Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating qualitative and quantitative research (5th ed.). Boston: Pearson Education, Inc. [ Links ]

Deller, K., Coetsee, W.J. & Beekman, L. (2007) Towards the design of a workplace RPL implementation model for the South African insurance sector (Part One). http://www.rpl.co.za/Portals/ (Accessed 10 August 2022).

Dewey, J. (1938) Experience and education. New York: MacMillan. [ Links ]

Dey, I. (2005) Qualitative data analysis: A user-friendly guide for social scientists. London: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group. [ Links ]

Eskom Academy of Learning (EAL). (2011) Learner Guide: Assess Employee: Manage Recognition of Prior Learning. Johannesburg: Eskom Holdings Soc Limited. [ Links ]

Flick, U. (Ed.) (2014) The SAGE handbook of qualitative data analysis. Los Angeles: Sage. [ Links ]

FutureLearn (2021) What are the fastest growing industries in Australia? https://www.futurelearn.com/info/futurelearn-international (Accessed 25 April 2023).

Gewer, A. (2021) Formal and informal VET in Sub-Saharan Africa: Overview, perspectives and the role of dual VET. Zurich: Donor Committee for Dual Vocational Education and Training (DC dVET).

Gray, D., Cundell, S., Hay, D. & O'Neill, J. (2004) Learning through the workplace: A guide to work-based learning. London: Nelson Thornes. [ Links ]

International Labour Organisation (2018) Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL): Learning Package, International Labour Office, Skiils and Employability Branch/Employment Policy Deparíment. Geneva: International Labour Organisation. [ Links ]

Kelly, C. (2003) Experimental learning. http://www.algonquinc.on.ca/edtech/gened/styles.html (Accessed 11 August 2022).

Kolb, D.A. (1984) Experiential learning. Experience as the source of learning and development. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Loynes, C. (2017) Theorising of outdoor education. In T. Jeffs & J. Ord (Eds.) Rethinking outdoor, experiential and informal education (1st ed.) London: Routledge, pp.35-56. [ Links ]

Makeketa, M-J. & Maphalala, M.C. (2014) Recognition of prior learning: Are we bridging the gap between policy and practice in the workplace? Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 5(1) pp.249255. [ Links ]

Maurer, M. (2023) Recognizing prior learning in vocational education and training: Global ambitions and actual implementation in four countries. Comparative Education 59(1) pp.1 -17. [ Links ]

McLeod, S. (2023) Kolb's learning styles and experiential learning cycle. https://www.simplypsychology.org/learning-kolb.html (Accessed 28 April 2023).

Miles, M., Huberman, M. & Saldana, J. (2014) Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). California: Sage. [ Links ]

Mooketsi, M.B. (2012) Recognition of prior learning (RPL): Perspectives and practices. Gaborone: Botswana Qualifications Authority.

Muscat, M. & Mollicone, P. (2012) Using Kolb's learning cycle to enhance the teaching and learning of mechanics of materials. International Journal of Mechanical Engineering Education 40(1) pp.66-84. [ Links ]

New Zealand Qualifications Authority (2001) Learning and assessment: A guide to assessment for the National Qualifications Framework. http://www.nzqa.govt.nz/assets/Studying-in-NZ/Tertiary/creditpolicy.pdf (Accessed 11 August 2022).

Palmer, R. (2020). Lifelong learning in the informal economy. Geneva: International Labour Organization. [ Links ]

Queensland Government (2014) Guidelines for the recognition of prior learning. https://www.forgov.qld.gov.au/human-resources (Accessed 23 August 2021).

Rakometsi, M. (2014) Recognition of prior learning: The value of informal learning. Paper presented at SAQA RPL Conference. https://saqa.org.za/docs/pres/2014/m_rakometsi.pdf (Accessed 30 August 2022).

Republic of Botswana (1994) Revised National Policy on Education. Gaborone: Government Printers.

Republic of Botswana (1998) Vocational Training Act (Act No. 22 of 1998) (Cap. 47:04). Gaborone Government: Printers.

Republic of Botswana. (2003). National Development Plan 9 2003/04-2008/09. Gaborone: Government Printers.

Republic of Botswana (2009) National Human Resource Development Strategy (NHRDS). Gaborone: Government Printers.

Republic of Botswana. (2013) Botswana Qualifications Act No.24 of 2013. Gaborone: Government Printers.

Republic of Botswana. (2016) Vision 2016. Gaborone: Government Printers.

Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., Nicholls, C.M. & Ormston, R. (2013) Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. Los Angeles: Sage. [ Links ]

Rubenson, K. (1996) Lifelong learning. In P. Ellström, B. Gustavsson & S. Larsson (Eds.) Experiences from a development programme for process operators. Lund: Studentlitteratur, pp.29-47.

Samoa Qualifications Authority (2010) Guidelines for the recognition of prior learning. http://www.sqa.gov.ws/formsAndDocuments/Qualifi.sqa.html (Accessed 10 August 2022).

South African Qualifications Authority (2016) Criteria and guidelines for the implementation of the recognition of prior learning. http://www.saqa.org.za/docs/crtguide/rpl/rpl00.pdf (Accessed 10 August 2022).

Srivastava, M. & Jena, S.S. (2015) Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL) and skill deficit: The role of open distance learning (ODL). Journal of Learning for Development 2(1) pp.12-26. [ Links ]

Van Rooyen, M. (2003) Training manual: Conduct outcomes-based assessment. Cape Town: Troupant Publishers. [ Links ]

United Nations. (2015) Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations. [ Links ]

UNESCO Institute for Education (2005) Recognition, validation and certification of non-formal learning and informal learning. Synthesis Report of the UIL's First International Survey. Hamburg: UIL. [ Links ]

Wallen, N.E. & Fraenkel, J.R. (2001) Educational research: A guide to the process. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]