Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

The Independent Journal of Teaching and Learning

versión On-line ISSN 2519-5670

IJTL vol.17 no.1 Sandton 2022

ARTICLES

Enriching the professional identity of early childhood development teachers through mentorship1

Keshni Bipath

University of Pretoria, South Africa2

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this paper is to highlight three professional identity tensions that are experienced by beginning teachers: the change in role from student to teacher; conflicts between expectations and realities of mentor support given to students (mentees), and contradictory notions of learning to teach. Research shows that Early Childhood Development (ECD) is losing many highly qualified teachers due to the perceived lack of proper mentorship in developing professional identity. This article outlines a study to explore the mentoring needs of ECD teachers in developing a positive professional identity. Participatory Reflection and Action (PRA) as a data collection method, which relied heavily on interpretivism as epistemology was conducted. The research sample consisted of all fourth year (final-year) undergraduate BEd students (n=713), who had to attend the compulsory teaching-practice component of the teacher training programme for the first time during the second and third quarters of the academic year. The BEd (Foundation Phase) students' completed matrices (maps) were transcribed, coded and categorised through thematic analysis. As a result, two dimensions of the participants' identity construction emerged: (1) Positive Role Modelling and (2) Missed Opportunities. It is suggested that mentor training, as well as scheduled talk-time and reflection opportunities between the mentors and mentees could transform the Work Integrated Learning (WIL) landscape and enrich the professional identity of Early Childhood Education teachers.12

Keywords: early Childhood Education teachers, mentoring, professional identity, teacher education programme

INTRODUCTION

It is important that universities pay serious attention to tensions such as helplessness, frustration and anger which are related to beginning teachers' professional identity during Work Integrated Learning (WIL). Three professional identity tensions that are experienced by beginning teachers are the change in role from student to teacher; conflicts between expectations and realities of mentor support given to students (mentees), and contradictory notions of learning to teach (Pillen; Beijaard & den Brok, 2013). There has been an increase in the number of studies conducted on teacher professional identity (Al-Khatib & Lash, 2017). However, very few studies have been done with the early childhood development (ECD) teachers, especially student teachers in this field (Thomas, 2012). The battle for the appreciation of the professional status of early childhood education teachers has been a challenge. The lack of achieving common qualifications, unqualified teachers, low pay, and poor public understanding that the work of early childhood practitioners is wasting time through play, have led to instabilities surrounding professional identity (Bipath & Joubert, 2016). This gap in research exists despite the growing demand for teachers at this level. Early childhood education teachers are faced with a number of challenges; among them is lack of professional identity and the mentorship needed to develop such an identity (Botha & Onwu, 2013).

Many countries are striving to improve the qualifications of teachers in the Early Childhood Development (ECD) phase. Such momentum is aimed at producing better equipped ECD teachers (Gibson, 2015), who are able to facilitate the holistic development of young children. Commencement of teaching is a particular and compound stage of teacher identity development (Avalos, 2011). Research shows that ECD is losing many highly qualified teachers (Fantilli & McDougall, 2009), at times due to the perceived lack of professional identity mentoring (amongst other factors).

This article outlines a study to explore the mentoring needs of ECD teachers in developing a positive professional identity. Nurturing of the ECD teachers' identity alone is not sufficient; it is through mentoring that desired change in the ECD teachers' professional identity will be accomplished. The process of mentoring teacher identity begins during the years student teachers spend in teacher training institutions and lasts for a lifetime (Osgood, 2006). I argue further that the sustainability of ECD teachers' professional identities relies on the continuation of mentoring by schools (Urban, 2015) and for this reason, I illuminate how effective mentoring enriches the professional identity of early childhood education teachers during WIL.

The next section provides a brief overview of developing professional identity; training mentors for effective professional identity development; mentoring to develop professional identity and the influence of mentoring on ECD.

LITERATURE REVIEW

While teacher professional identity does not develop without being nurtured, the questions raised are how then should such nurturing, and mentoring be done? Fraser (2018: 7) discovered that student teachers complained about their mentor lecturer interactions, and criticised 'the absence of moral and spiritual support, lack of involvement and poor communication styles'. Bouwer, Venketsamy and Bipath (2021: 28) suggest that 'collaborative, comprehensive and critically constructive discussions should be held by mentor lecturers after lessons are taught during WIL'. This could perhaps assist student teachers in moulding their professional identity.

ECD teacher professional identity entails 'exploring, understanding and finding one's own style in teaching' (Abongdia, Foncha & Dakada, 2015: 495). Professional identity is influenced by one's past, present and future experiences in relation to how they are viewed by those around them. Professional identity is 'an intricate and tangled web of influences and imprints rooted in personal and professional life experiences', says Bukor (2015: 306). He argues that professional identity reflects the values and beliefs of all the interrelationships and connections that human beings experience. This includes the professional, educational, and pedagogical aspects of being a teacher. Jackson (2017: 15) considers

professional identity as a complex phenomenon spanning awareness of and connection with the skills, qualities, behaviours, values, and standards of a student's chosen profession, as well as one's understanding of professional self in relation to the broader general self.

Societal expectations, field placements during their pre-service course as well as previous experiences of teachers and teaching has moulded the professional identity (Beltman et al., 2015). Friedman (2004: 312) describes the 'shattered dreams' that teachers experience as they journey between the potentially conflicting worlds of expectations and reality. The tensions they experience cause teachers to resign after a few years, as they realise that teaching is regarded as a low status job.

The future of the profession rests on our ability to develop new... methods to help individuals cope with the new organisation of work that is becoming increasingly less predictable, regulated, stable, and orderly (Savickas: 2019: n.p.).

Developing professional identity

At the start of the profession, it is essential to carve a strong, coherent teacher identity in beginning teachers. This is related to teacher retention, resilience and effectiveness (Mansfield, Beltman & Price, 2014). Boydell (1986) alerted us to the three main role players in the WIL relationship: namely, the student teacher, the mentor lecturer and the mentor teacher. Understanding how mentee teachers' professional identity develops during the WIL in teacher education programmes will allow mentor lecturers and mentor teachers to formulate guidelines to prepare mentee teachers for the reality of teaching. Mentee teachers should this be enlightened on how to engage in 'a productive process of constructing their professional identities' (Izadinia, 2013: 712).

Training mentors for effective professional identity development

A variety of tasks and tools as well as personal and contextual factors come into play for effective mentoring. Beutel and Spooner-Lane (2009) point out the importance of training mentors for their roles. The University of Tampere (Finland) ensures that mentor training occurs before mentor teachers are tasked with mentoring. Without the training, they are not permitted to mentor students.

Preschool teacher training involves lectures, seminars, small group exercises, and practicums in a preschool. In Finland, each practicum has different goals. The ethics and professional identity of the preschool teacher, as well as observing the learning environment and the children from the focus of the first practicum. The pedagogy and curriculum work of ECD is part of the second practicum. The holistic responsibility in the preschool teachers' work, including cooperation with the preschool's multi-professional team and the children's parents is realised in the third practicum. This practicum also allows the students to investigate the development process in the preschool. It is the responsibility of the university lecturer (mentor lecturer) and a preschool teacher (mentor teacher) to guide practicums.

Student teachers (mentees) develop professionally during the three practicums. A mentee's first years of practice is well documented, as the growth and development is referred to during the later practicums. The first year is regarded as crucial as this is where the construction process of professional identity begins, and students grow into their future roles as teachers. Moreover, Pendergast, Garvis and Keogh (2011) state that students are given an opportunity to face the reality of a teacher's role during these practicums. Trained and motivated mentors are thus essential in the development of a mentees' professional identity (Balduzzi & Lazzarri, 2015; Leshem, 2012; Ukkonen-Mikkola & Turtiainen, 2016).

The mentor is looked upon as an example of a professional and a role model (Johnson, 2007). In Russell and Russell's (2011) study, mentors also viewed themselves as guides and individuals offering resources. These roles have an impact on the professional identity development of the mentee. A good relationship with the mentor supports the student's professional identity construction (Johnson, 2007). Mentorship and professional identity is studied more in the school context (Heikkinen, Jokinen & Tynjala, 2012).

Mentoring to develop professional identity

Professional identity (PI) consists of four characteristics (Al-Khatiba & Lash, 2017). PI depends on an individual's experiences. It is influenced by the interaction of an individual and their surroundings. The involvement between the mentors and mentees themselves is of importance in the development of their professional identity.

Mentoring to develop professional identity among ECD teachers is essential for beginning teachers (Rhodes, 2006). Rhodes (2006) posits that though professional identity is developed by one's interaction with families and cultures, interaction with colleagues in the workplace is prominent. Encounters teachers have with their managers on a day-to-day basis are likely to form part of professional identity mentoring. Professional identity mentoring, according to Thomas (2012), is a process that involves its construction and reconstruction. He reiterates that mentoring professional identity is not a once-off experience, but rather a process that lasts a lifetime. Langford (2007) states that acknowledgement of the importance of diverse prerequisites is central to the construction and reconstruction of early childhood education teacher identities.

Teachers with low self-esteem could be bound to experience lack of professional identity, hence the significance of mentorship. Teacher development happens throughout one's teaching career, indicating the need for developing professional identity in schools. In this light, Moloney (2010) argues that in ECD, professional identity is awkward due to lack of obligatory training prerequisites.

The influence of mentoring on ECD

The battle for the appreciation of the professional status of early childhood has been unending and challenging in Australia as elsewhere. Underqualified and unqualified practitioners, very low wages and poor public opinions that the job of an early childhood practitioner is one of babysitting and play rather than work have led to uncertainties surrounding professional identity. A positive professional identity has the prospective to reduce attrition rates for novice ECD teachers (Cattley, 2007), who make up the majority of those who resign from the profession (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2001). Teacher identity is related to how teachers teach and their growth as professionals, and it influences plans to leave the profession (Schepens et al., 2009).

Langford (2007) views professional identity as the result of a cultural pact, interference, blending and disjuncture. The extent to which a teacher is valued and respected by society impacts on her professional identity. Teachers are influenced by their cultures, and this forms a significant aspect of professional identity. Culture impacts on our way of doing things in life, so it is the situation with the professional identity of ECD teachers. Mentoring of teachers during WIL can emancipate ECD teachers from aspects of culture that lead to devaluing and undermining of their professional identity.

Mentors in schools need to have an interest in school activity and have adequate knowledge and skills regarding the curriculum and how to execute it, (Kupila, Ukkonen-Mikkola & Rantala, 2017). They hold that not mentored, teachers might be frustrated, unstimulated and non-participative in terms of integration into a variety of school activities. Fraser's (2018: 9) study concurs with this statement when he quotes a comment from a 4th year student teacher after a mentoring experience:

We have learnt to think outside the box. We have learnt to work with one another, which will help us in the workplace in order to be able to work with other teachers...

An ECD teacher should be able to work collaboratively with other teachers. Such a level of teamwork and support requires influencing professional identity of teachers by the school managers. Professional identity development gives teachers an opportunity to merge theory with practice in their classes. In a study conducted by Botha and Onwu (2013: 7), the findings revealed that the novice teachers who were mentored during their teaching in terms of relating theory to practice at the workplace, experienced 'positive mediating influences that grew and sustained their identity formation'.

The purpose of this study was to determine the mentoring needs of student teachers and the mentoring responsibilities of the mentor lecturers and teachers in order to enrich the professional identity of early childhood development teachers.

METHODOLOGY

Paradigm

The qualitative design of the study, with specific reference to PRA school-based activities, relied heavily on interpretivism as epistemology. The framework that provided the structure to the study lay vested in Engestrom's Activity Theory. This framework represented the broad base of teaching practice which should be regarded as the main activity or event defining WIL. It embraced WIL as 'unit of analysis' capturing the experiences of student teachers over period of time. In the context of this study, mentorship during WIL played a sound instrumental role.

Participatory Reflection and Action (PRA) as Data Collection Method

The decision to use PRA as the research method was built on two premises. The first premise ensured the emancipatory and empowering nature of participatory research as data collection strategy. Von Maltzahn and van der Riet (2006: 110) refer to the 'strong social justice orientation' of participatory research, as well as the value of participatory research to construct knowledge within a particular social context. The second premise sought security in addressing emerging profession-related challenges and problems as they emerge. When we decided to use PRA, we were guided by Von Maltzahn and van der Riet's (2006: 110) observation that it 'gives people an opportunity to articulate what they feel the problems are and to generate relevant solutions'. This became the cornerstone of PRA as a data collection and capacity building strategy. I decided on a strategy that would allow participants to reflect on the development of their professional identities, report on emerging challenges, and also to allow them to introduce measures that could strengthen areas of concern. Ferreira and Ebersohn (2012) explain that PRA is built on three premises, namely, the participants working in the field are not experts, those local problems require local solutions, and the actions to be taken in solving these problems, would result in empowerment.

Research Sample

The research sample consisted of all University of Pretoria fourth year (final year) undergraduate BEd students (n=713) who had to attend the compulsory WIL component of the teacher training programme for the first time during the second and third quarters of the 2015 academic year. What made this intake unique is the fact that it was the participants' first school visit in four years and many students thought this to be extremely challenging and uncertain. The majority of the participants (79%) were female, while 21% of the sample were male. The selected sample for this study included all fourth-year students enrolled for the foundation phase (n=100).

Data collection method

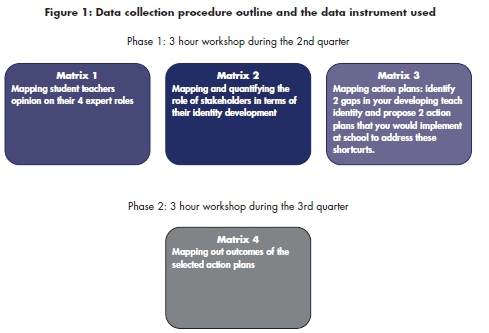

Student teachers attended the first three-hour workshop on campus one month into WIL followed by a second workshop at the end of their three-month WIL period. At the workshops, they formed groups of 10 according to their specialisations and participated in the first PRA data collection exercises. Hence 10 groups of 10 (n=100) foundation phase mentees' matrices were used as data for this article. Figure 1 describes the main tasks of the data capturing instruments or matrixes. Matrix 2 was mostly used for the capturing of data for this article. A two-phased data collection approach which occurred during the 2nd quarter and 3rd quarter of the year follows:

Data analysis procedure

Thematic analysis was used to make sense of the data. Matrix 2 used for this article required students to rank and state the importance of mentors to the development of their professional identities. This specific dimension of identity coincided well with so-called professional identity defined by Day, Elliot and Kington (2005: 263) as the expectations of a 'good teacher' as well as the 'educational ideals' of the teacher. The completed matrices were transcribed, and the collected data coded classified and categorised according to themes. Member checking was done during the 2nd phase of the data collection which occurred after three months.

Ethics

Managing the Research Process prior to the commencement of the PRA workshops and the required permission to conduct the study was sought from faculty management as well as from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Education of the university. Student teachers were informed about the workshop date and times by mail and short text messages. Participants were briefed on the purpose of the workshop prior to the commencement of each workshop. They gave their written consent before participating in the workshop.

FINDINGS

Two dimensions of the students' experiences that contributed to their identity building emerged for consideration; (1) Positive Role Modelling and (2) Missed Opportunities.

Positive Role Modelling

Group 1 complimented their mentor teacher for 'changing their perspectives of life skills' and for 'giving them positive feedback regarding their teaching' and showing them how to change 'bad situations into good ones'. Group 2 was positive regarding the advice about improvement of teaching that was given to her from the mentor teacher.

They always encourage us to do better and take charge of our lives.

Group 3 described their experience of their mentor teacher as

They were transparent, did not hide the challenges. They hinted on things that work and do not work in school and teaching in the day we are living in. They taught us how to focus on different types of learners, not just focus on the gifted ones only.

Group 4 described their mentor teacher as a 'second parent'. They elaborated:

They were the first role models we were ever exposed to. They helped us with being respectful and most disciplined. They helped and motivated us to do better and believe in ourselves and they build our knowledge and created a solid foundation for us.

Group 5 mentioned their positive experience as

They involved us more, encouraged us to be more open about our past struggles and victories. They encouraged us and gave us tips and ideas.

Group 6 praised their mentor teacher by saying

.they provided helpful guidelines to teach, demonstrated effective administrative strategies, gave us tips on dealing with troublesome learners, taught us different methods of teaching and offered realistic examples and expectations of actually being a teacher.

Group 7 said that their mentor teachers

gave us guidance, tips, moral support, feedback and were our educators too.

Group 8 described their experiences as follows:

...they exposed us to the real demand of teaching that includes setting of question papers, and they gave us guidance in lesson preparation and other admin issues.

Students in Group 8 valued the mentor lecturer as the greatest contributor to their positive identity. They said:

My mentor lecturer is playing a significant role that is contributing to shaping our teacher identity. She is a doctor and well educated. She advised me well and was the stamp of approval in praising me for choosing the best career. She gave me 'rare high marks' which showed her framing our identity in a positive, reflective manner.

This statement shows that the mentor lecturer can make a difference to students in their final year. However, it could be that the marks given by the mentor lecturer was the reason for this positive comment by this group. Group 9 also praised the mentor lecturer as follows:

They motivated us through their way in which they present themselves and inspired us through their passion for education.

Thus, role modelling and praise for effort proved an important factor in developing a positive professional identity.

Missed Opportunities

Missed opportunities in developing professional identities amongst student teachers was prevalent in the findings. Groups 9 and 10 complained about their mentor teachers:

The mentor teachers take advantage and overload us with their work

and

Although our mentor teachers' characters motivate us as student teachers, they give us their work to do while they are sitting and chatting on phones.

The student teachers considered their mentor lecturer to have played the least significant role in their professional identity building. Group 1 recommended that

We feel that it can be wise and very helpful if the mentor lecturers can visit at least 5 to 6 times to the schools, just for 'sit ins' in the student lessons to render motivational words before and after assessment.

Group 2 questioned

Why hasn't the university taught/shaped us accordingly in some aspects? They stated that the university could have

focused more on practicals from the first year.

Clearly, this statement shows that these 10 students in this group realised the benefits of WIL but were wondering why teaching practice does not occur from the first year. Group 3 echoed the same sentiment stating that

They should have made us do the practical part earlier, exposed us more to the real world and they should have designed modules to be more practical and focused on what is done in schools.

Group 4 saw the lack of preparation on the part of mentor lecturers who

instead of guiding us on becoming teachers.they encouraged us to continue with our studies.

Perhaps this is due to some mentor lecturers not being in schools themselves and having adequate training as a schoolteacher before they became lecturers. Group 5 complained that instead of being helpful and supporting them, they 'emphasised weaknesses'. However, they mentioned that their mentor lecturers

gave us positive criticism, appreciated and encouraged us.

Group 6 recommended that mentor lecturers

must provide us with more practical opportunities and expectations should be realistic.

This group complained that theory was quite repetitive. Group 7 complained that their mentor lecturer was very disrespectful to them and showed a

lack of communication, poor people skills, lacking expertise, inadequate knowledge and poor punctuality.

However, Group 10 complained about the lack of preparation by the mentor lecturer:

He is not eager to shape me as a student teacher. During his first visit he did not assess my file. He did not fill page 9 of the reader of which he was supposed to fill.

The possible reason for this is that due to lecturers being so overloaded with tasks and research loads, the university hires outside people - previous teachers or retired teachers to assist in assessing the students. However, if the mentor lecturer is not trained by the university on how to shape the professional identity of students, this was an opportunity wasted.

So, it was clear that the mentees valued the input from their mentor teachers more than their mentor lecturers. Most students also ranked their mentor teachers' impact on their professional identity development higher than that of the mentor lecturer.

Discussion

The aim of the study was to investigate whether mentorship during WIL enriched the professional identity of ECD teachers. Unfortunately, the missed opportunities by the mentors proved to be challenges in enriching the professional identity development. Therefore, transformation efforts to improve the WIL experience needs to be implemented. The themes from the data highlighted the practical implications for enriching the mentorship of student teachers during WIL.

Train the mentor teacher and mentor lecturer

The two important mentors (mentor teacher and mentor lecturer) for the optimal development of a student teachers' professional identity, need to be trained. At universities, student teachers are assigned mentor teachers and mentor lecturers. These mentors are given manuals from the WIL office, on how to assess and support students. Contact sessions for training are provided for mentor lecturers; however, these are not compulsory. Furthermore, these mentor lecturers are assigned an average of 10 students, over and above their general workload. Perhaps, university lecturers find themselves inundated with postgraduate students as well as research activities that they do not have time to attend training sessions as mentor lecturers before going out for WIL assessments. Training sessions should be available online and should be compulsory for both mentor lecturers and teachers.

Unawareness of expectations from the mentor lecturers during WIL

The lack of mentor lecturer training regarding expectations from student teachers is clear from the negative responses from students on mentor lecturers. One group requested that mentor lecturers come more often, '5 to 6 times for sit ins' on teaching. This confirms that the students need to prove to lecturers that are converting theory to practice. Students seem to want to see their lecturers in their classrooms. Students expressed their discontent about being exposed to WIL very late in their teaching degree. Maybe exposure to schools in their first year through practical held in classrooms or having teaching schools linked to universities could prove beneficial.

Students enter their schools and listen and learn from their mentor teachers as these teachers will provide a final mark for their practice teaching. The mentor teachers sometimes take advantage of the students and use them 'as markers for the work that they marked for the term' (communication from 4th year mentee). This practice should not be encouraged, and mentor teachers need to realise their importance as a role model for the mentees. They have the power to create unhappiness and demotivation in the mentee and this can severely impact their future careers. Universities need to warn mentor teachers to refrain from using their power over their mentees ruthlessly.

The importance of motivation and positive professional identity development

Group 9 showed how the mentor lecturer made a difference to their professional identity. The way their mentor lecturer

presented themselves, inspired us through their passion for education

showed them that they had chosen the right profession. The students say that due to positive professional identity development and moulding, they felt confident that they were in the right profession and were going to make a difference in learner's lives.

Talk-time between mentor teacher and mentee teacher

Adequate time should be scheduled for the meet and greet (initial meeting) between mentor and mentee teacher. This relationship building activity is very important when establishing a cooperative, collaborative learning relationship. Establishing a trusting communication channel between mentors and mentees would allow each to share their experiences in a safe and trusting environment. Bouwer, Venketsamy and Bipath (2021 : 29) agree that safe learning spaces for students would 'ensure Grade R student teachers' experiences of WIL are positive for teaching and learning to occur'.

Development of Trust

The 'only vehicle on which the journey can be made is trust' (Sgroi, 1998: 26). By valuing each other's ideas and opinions and having an open commitment to in-depth discussions, collaborative expansion of ideas is possible. By working as a Community of Practice (COP) with the mentor teachers and lecturers, modelling and experimentation of lesson plans can occur. When mentors and mentees are paired, the mentee would begin to form ideas of how she or he needs to perform or behave as a teacher. Mentees are wanting to emulate good practices, and mentors therefore need to be aware that how they behave and what they believe is being scrutinised and this could make an indelible impression on the minds of the young teacher. Mentee teachers need to be well informed and encouraged to challenge currently held ideas. Explicit guidance is required from mentor teachers. This needs to be discussed in the first mentoring session. Adequate time is required to consider the deeper implications on a mentor -mentor partnership. Further time spent in stimulating discussion about teaching and learning is as important as time spent teaching and observing learners in classrooms.

Reflection opportunities between mentors and mentees

Reflections after every lesson taught or activity facilitated is an expectation of work-integrated placements. It is assumed that these reflections would refine their personal philosophies of teaching and learning. The students have their personal philosophies in their portfolio files. The mentor lecturer will need to spend time reading this and allowing time for the student to reflect on whether the lesson observed showed the characteristics of his philosophy as recorded. The students will also realise the importance of the reflections for his /her growth as a professional teacher and will pay more attention to planning and preparation of the portfolio file as this file becomes a teaching resource when he/she is a fully fledged teacher. It is hoped that mentees would develop reflections of lessons as a habit that they would take through in their daily practice as teachers.

Field and Field (1994) provide narratives where the student teachers have felt alienated and uncomfortable with their mentor teachers. These mentee teachers are afraid to divulge their negative feelings because of their fear of being judged by the school and mentor teachers. Compliance is seen as the 'safer' option, since open and deep discussions are sometimes not entertained. The mentee feels devalued and this leads to helplessness, and disenchantment with the job. Therefore, the mentor lecturer needs to ensure that reflection occurs in a safe space with respect for mentees and mentor teachers.

Reflection on one's own practices, experiences, perceptions and beliefs is a core activity for all teachers, pre-service and in-service, in schools and universities. The concepts of both teacher role and teacher identity are integral to create a zest for life-long learning in the 'becoming teacher' (Mayer, 1999). The 'intellectual dimension of expert practice is, for most teachers, reflection' (Mayer, 1999: n.p.). The reflections of their responsiveness and reciprocity in the classrooms with their learners, as well as the choice of the resources for stimulating the learner, needs to be discussed in an open and trusting way. By doing this student teachers begin to realise that he or she is responsible for quality teaching and thus would be more responsible when drawing up lesson plans and setting up learning environments for learner achievement.

Portfolio File as a tool for professional development

Student teacher portfolios are available, effective, and appropriate tools in documenting teacher growth and development and in promoting reflective, thoughtful practice. Mentors should be given clues on how to analyse portfolios in a professional way in order to develop students' professional identities positively. The mentee teacher needs to begin to take responsibility for his actions in the choice of resources, the context, as well as the cultural diversity of learners in the class. Positive teacher identity is promoted when mentees and mentors dedicate sufficient time to empowering mentee teachers to make their own decisions, learn through research in action and understand that the children in the class are reliant on their methods of teaching to learn optimally. Thus, the mentor teacher should promote a collegial relationship, based more on mentoring rather than supervision. This would enhance the capacity and identity of the mentees. They would feel empowered to make a difference to learning and thus feel a sense of pride in becoming a professional.

CONCLUSION

This article aimed to explore the mentorship opportunities and challenges of ECD teachers in developing a positive professional identity during WIL. Due to the problem of many teachers leaving the profession at an early stage, the importance of an excellent mentoring relationship between mentor teachers/ lecturers and mentees is essential for developing a strong professional identity. The findings of this study showed that positive role modelling and missed opportunities within a mentor-mentee relationship led to disenchantment and devalued professional identities. Higher Education Institutes will need to train their mentor lecturers and mentor teachers so that they realise their motivational role and the deep impression that they create in future careers of young teachers. Future training models for mentors need to be created where mentees and mentors from schools and higher educational institutions form new habits and work as communities of practices (COPs), providing a safe environment for mentee teachers to value their professional identity as ECD teachers and become life-long learners. Individuals in a COP share ideas and activities, as well as ways of communicating and acting in the profession (Morrell, 2003). Hawkins and Rogers (2016) discovered that working in a COP helped student teachers to develop professionally and that COPs can be customised to improve WIL experiences. Thus, if we are to transform the WIL landscape, mentors cannot only work vertically (top-down) with student teachers. It has become more urgent to work horizontally, understand problems and provide the space for students to interact and express themselves freely in COPs. This horizontal approach could embrace student teachers' professional identity and thus enrich the mentoring experiences of education graduates at higher educational institutes.

REFERENCES

Abongdia, J.A., Foncha, J.W. & Dakada, A. (2015) Challenges Encountered by Teachers in Identifying Learners with Learning Barriers: Toward Inclusive Education. International Journal of Educational Science 8(3) pp.493-501. [ Links ]

Al-Khatib, A.J. & Lash, M.J. (2017) Professional Identity of an Early Childhood Black Teacher in a Predominantly White School: a Case Study Child Care in Practice 23(3) pp.242-257. [ Links ]

Avalos, B. (2011) Teacher Professional Development in Teaching and Teacher Education over Ten Years. Teaching and Teacher Education 27 pp.10-20, https://doi.org/10.10167j.tate.2010.08.007 [ Links ]

Balduzzi, L. & Lazzarri, A. (2015) Mentoring practices in workplace-based professional preparation: a critical analysis of policy developments in the Italian context. Early Years: An International Research Journal 35(2) pp.124-138, https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2015.1022513 [ Links ]

Beltman, S., Glass, C., Dinham, J., Chalk, B. & Nguyen, B. (2015) Drawing identity: Beginning pre-service teachers' professional identity. Issues in Educational Research, 2015 25(3) pp.225-245. [ Links ]

Beutel, D. & Spooner-Lane, R. (2009) Building mentoring capabilities in experienced teachers. The International Journal of Learning 16 pp.351-360. [ Links ]

Bipath, K. & Joubert, I. (2016) The birth of a new qualification for ECD. Mail and Guardian. 27th May 2016.

Bouwer, M, Venketsamy, R. & Bipath, K. (2021) Remodelling Work-Integrated Learning experiences of Grade R student teachers. South African Journal of Higher Education 35(5). [ Links ]

Botha, M. & Onwu, G. (2013) Beginning teachers' professional identity formation in early science mathematics and technology teaching: What develops? Journal of International Cooperation in Education 15(3) pp.3-19. [ Links ]

Boydell, D. (1986) Issues in teaching practice supervision research: A methodological approach in motion. Historical Social Research 37(4) pp.191-222. [ Links ]

Bukor, E. (2015) Exploring teacher identity from a holistic perspective: reconstructing and reconnecting personal and professional selves. Teachers and Teaching 21(3) pp.305-327, doi:10.1080/13540602.2014.953818 [ Links ]

Cattley, G. (2007) Emergence of professional identity for the pre-service teacher. International Education Journal 8(2) pp.337-347. [ Links ]

Day, C., Elliot, B. & Kington, A. (2005) Reform, standards and teacher identity: Challenges of sustaining commitment. Teaching and Teacher Education 2 pp.563-577, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2005.03.001 [ Links ]

Fantilli, R. & McDougall, D. (2009) A study of novice teachers: Challenges and supports in the first years. Teaching and Teacher Education 25 pp.814-825, doi:10.1016/j.tate.2009.02.021 [ Links ]

Ferreira, R. & Ebersohn, L. (2012) Partnering for Resilience. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Field, B. & Field, T. (1994) Teachers as mentors: a practical guide. London: The Falmer Press. [ Links ]

Fraser, W.J. (2018) Filling the gaps and expanding spaces - voices of student teachers on their developing teacher identity. South African Journal of Education 38(2) pp1-11. [ Links ]

Friedman, I.A. (2004) Directions in teacher training for low-burnout teaching. In E. Frydenberg (Ed.) Thriving, surviving, or going under: Coping with everyday lives. Greenwich, Connecticut: Information Age Publishing.

Gibson, M. (2015) Leadership for Creating Cultures of Sustainability. In J. Davis (Ed.) Young Children and the Environment. Early Education for Sustainability. Melbourne: Cambridge Press. [ Links ]

Hawkins, S. & Rogers, M. (2016) Tools for reflection: Video-based reflection within a preservice community of practice. Journal of Science Teacher Education 27(4) pp.415-437. [ Links ]

Heikkinen, H.L.T., Jokinen, H. & Tynjala, P. (2012) Teacher education and development as lifelong and lifewide learning. In H.L.T. Heikkinen, H. Jokinen, & P. Tynjala (Eds.) Peer-group mentoring for teacher development pp.3-30. Abingdon, OX: Routledge. [ Links ]

Izadinia, M. (2013) A review of research on student teachers' professional identity. British Educational Research Journal 39(4) pp.694-713, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01411926.2012.679614 [ Links ]

Jackson, D. (2017) Developing pre-professional identity in undergraduates through work-integrated learning. Higher Education 74, doi:10.1007/s10734-016-0080-2 [ Links ]

Johnson, W. B. (2007) On being a mentor. A guide for higher education faculty. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Kupila, P., Ukkonen-Mikkola, T. & Rantala, K. (2017) Interpretations of Mentoring during Early Childhood Education Mentor Training. Australian Journal of Teacher Education 42(10) http://dx.doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2017v42n10.3 [ Links ]

Langford, R. (2007) Who is a Good Early Childhood Educator? A Critical Study of Differences within a Universal Professional Identity in Early Childhood Education Preparation Programs. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education 28(4) pp.333-352, doi:10.1080/10901020701686609 [ Links ]

Leshem, S. (2012) The many faces of mentor-mentee relationships in a pre-service teacher education programme. Creative Education 3(4) pp.413-421, https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2012.34065 [ Links ]

Mansfield, C.F., Beltman, S. & Price, A. (2014) 'I'm coming back again!' The resilience process of early career teachers. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice 20(5) pp.547-567, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2014.937958 [ Links ]

Mayer, D. (1999) Building teaching identities: implications for pre-service teacher education. Paper presented to the Australian Association for Research in Education, Melbourne.

Malony, M. (2010) Professional identity in Early Childhood Care and Education: Perspectives of pre-school and infant teachers. Irish Educational Studies June 2010 29(2) pp.167-187, doi:10.1080/03323311003779068. [ Links ]

Morrell, E. (2003) Legitimate peripheral participation as professional development: Lessons from a summer research seminar. Teacher Education Quarterly 30(2) pp.89-99. [ Links ]

Osgood, J. (2006) Deconstructing Professionalism in Early Childhood Education: Resisting the Regulatory Gaze. Contemporary issues in early childhood 7(1) pp.5-14. [ Links ]

Pendergast, D., Garvis, S. & Keogh, J. (2011) Pre-service student-teacher self-efficacy beliefs: An insight into the making of teachers. Australian Journal of Teacher Education 36(12) pp.46-58, https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2011v36n12.6 [ Links ]

Pillen, M., Beijaard, D. & den Brok, P. (2013) Tensions in beginning teachers' professional identity development, accompanying feelings and coping strategies. European Journal of Teacher Education 36(3) pp 240-260, doi:10.1080/02619768.2012.696192 [ Links ]

Rhodes, C. (2006) The impact of leadership and management on the construction of professional identity in school learning mentors. Education Studies 32(2) pp.157-169. [ Links ]

Russell, M. L. & Russell, J. A. (2011) Mentoring relationships: Cooperating teachers' perspectives on mentoring student interns. Professional Educator 35(1) pp.16-36. [ Links ]

Savickas, M.L. (2019, September). Designing a self and constructing a career in post-traditional societies. Keynote address at the 43rd International Association for Education and Vocational Guidance Conference, Bratislava, Slovakia.

Sgroi, A. (1998) Teaching learning partnerships in the arts. In I.M. Saltiel, A. Sgroi & R.G. Brockett (Eds.) The power and potential of collaborative learning partnerships San Francisco: CA, Jossey-Bass.

Schepens, A., Aelterman, A., Vlerick, P. & Vlerick, A. (2009) Student teachers' professional identity formation: Between being born as a teacher and becoming one. Educational Studies 35(4) pp.361-378 doi:10.1080/03055690802648317 [ Links ]

Thomas, L. (2012) New possibilities in thinking, speaking and doing: Early childhood teachers' professional identity constructions and ethics. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood 37(3) pp.87-95. [ Links ]

Ukkonen-Mikkola, T. & Turtiainen, H. (2016) Learning at work in the boundary space of education and working life [Tyossaoppiminen koulutuksen ja tyoelaman rajavyohykkeella]. Journal of Early Childhood Education Research 5(1) pp.44-68. [ Links ]

Urban, M. (2015) From 'closing the gap' to an ethics of affirmation. Reconceptualising the role of early childhood services in times of certainty. European Journal of Education 50(3) pp.293-306, https://doi/10.1111/ejed.12131 [ Links ]

Von Maltzahn, R. & Van der Riet, M. (2006) A critical reflection on participatory methods as an alternative mode of enquiry. New Voices in Psychology 2(1) pp.108-128.

1 Date of submission 22 July 2020; Date of review outcome: 15 December 2020; Date of acceptance 17 March 2021

2 ORCID: 0000-0003-0588-9905