Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

The Independent Journal of Teaching and Learning

versão On-line ISSN 2519-5670

IJTL vol.17 no.1 Sandton 2022

ARTICLES

Motivating Grade 12 learners at a quintile 3 secondary school in South Africa1

Thaabit IsmailI; Thobeka MdaII; Nomakhaya MashiyiIII

ICape Peninsula University of Technology, South Africa2

IICape Peninsula University of Technology, South Africa3

IIICape Peninsula University of Technology, South Africa4

ABSTRACT

This study identifies factors that motivated Grade 12 learners at a quintile 3 secondary school in post-apartheid South Africa. A phenomenological qualitative approach was adopted. Semi-structured interviews were used to collect data from Grade 12 learners. Human Motivation theory and Self-determination theory were synthesised to form an underpinning theoretical structure. The results of the research study identified various factors that motivated Grade 12 learners: parental involvement, affirmation, and enjoyment of subjects. Knowing about such factors and applying motivational interventions at schools in poor areas affirms learners and empowers them to escape destitution, despair, cycles of illiteracy and poverty, and the bonds of a racist past. Teachers and parents should be cognisant of such important factors. School communities, particularly those in economically challenged areas, need to be made aware of the value of such motivating factors.

Keywords: extrinsic motivation, intrinsic motivation, motivation to learn, self-actualisation, self-determination

INTRODUCTION

Motivation is essential in any learning process and fundamental for academic success (Gbollie & Keamu, 2017). Teachers, parents and the school community as a whole need to be made aware of the value and power of motivation as a primary means of encouraging, affirming and empowering learners, and ultimately giving them the self-confidence and skills to lift themselves out of poverty, and break free from the sense of worthlessness which apartheid imposed upon so many households. Well-considered motivational interventions initiate, enhance and sustain authentic acquisition, personal assimilation and ownership of new knowledge (Ghaedi & Jam, 2014).

Researchers in South African and international contexts have identified numerous factors that can affect learner motivation, such as socio-economic conditions, parents, classmates, friends and teachers (Nel, 2000), test anxiety, nervousness about academic evaluation, a fear of failing tests, or an unpleasant experience of learners in various situations (Rastegar, Akbarzadeh & Heidari, 2012). There is considerable uncertainty concerning which factors stimulate learners in South African schools. Since schools are arranged according to the income of parents, traditionally white schools have been allowed to flourish almost as semi-private schools since liberation in 1994. Schools which were classified as non-white under apartheid received the lowest level of funding before 1994 and have seldom been able to escape the privations of that era since. South African public schools are categorised into five different groups termed 'quintiles'. Quintile 1 schools serve learners from the poorest parts of a province. Quintile 5 schools are fee-paying and serve learners from the most prosperous areas (Hall & Giese, 2008). According to Grant (2013), these quintiles or rankings are determined according to the poverty levels and indicators of the community around the school as well as certain infrastructural factors. Contrary to its liberatory intentions, post-apartheid government has inadvertently constructed a classist, capitalist system of schooling not dissimilar to the public versus comprehensive school structure in England. Instead of enabling education to achieve egalitarian priorities, the quintile system has entrenched privilege at quintile 5 level, and cycles of illiteracy and hopelessness at quintile 1-3 levels. This research project reveals motivational factors that grant learners the self-belief and skills to escape such cycles. The ultimate success of such initiatives lies with the school community, that range of concerned and committed individuals who are determined to reverse the deprivations of the past and deploy education as the vital means to do so. According to Horgan (2007), learners at disadvantaged quintile 1-3 schools are mainly motivated to find a path to secure employment in order to escape the destitution with which they are familiar. Learners from advantaged schools are more motivated to use better education as a means to attain a high-paying professional job. This invidious distinction in post-apartheid South Africa has replaced racist distinctions before 1994 with a classist education system which enables the new multiracial rich to become wealthier while the quintile 1-3 areas welter in continuities of impoverishment, humiliation, unemployment, drug abuse, crime and despair.

The project noted a significant decrease in the Grade 12 pass rate from 82% in 2015, to 79.5% in 2016 and 62% in 2017 (DBE, 2017). This poor performance caused concern among teachers and management at the school. Researchers on this project sought to detect whether motivational issues of Grade 12 learners at this school were related to the low pass rate. At the quintile 3 secondary school selected for this research, it was observed that Grade 12 learners ranged from a few who worked hard to achieve success, to many learners who did the minimum. It was noted that in the same classroom, some learners were evidently highly motivated, while others were demotivated, although the learners were from relatively similar backgrounds. This study provides teachers, school management and parents with a better understanding of why learners in the same classroom are interested in learning and others not. Once the school and parents are made aware of these factors, appropriate strategies can be implemented to motivate learners to learn more readily, prevent learners from being demotivated towards their academic studies and enable them to succeed and reach their full potential. Little research has been conducted in the broader national and international context to investigate motivation of Grade 12 learners from communities similar to this one. This study is unique, pertinent and useful to schools, not only in the Western Cape and South Africa, but also to schools with similar social contexts in other developing countries outside of South Africa, and developed countries which manifest severe social/racial stratification such as the UK or USA.

In order to establish what factors intrinsically or extrinsically motivate or demotivate Grade 12 learners to commit themselves to learn, the following research question was posed:

• How do Grade 12 learners at a quintile 3 secondary school explain what motivates or demotivates them to learn?

LITERATURE REVIEW

Several national and international studies investigating motivation underline the two key types of motivation: namely, intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Since the early 1970s, research has been conducted to determine the impact of these two main types of motivation. Researchers such as Deci (1972), Deci & Ryan (1980, 1985, 1991, 2000) have constantly revised the theoretical parameters and philosophical understandings of the terms 'intrinsic and extrinsic motivation' in their Self-determination theory (SDT). Unlike other researchers who emphasise the amount or level of motivation, Deci and Ryan (2000) concentrate the focus of their research upon the different types of motivation that determine motivated behaviour. Their research confirms that the type or quality of motivation is more important than the amount of motivation for predicting many significant outcomes such as 'psychological health and well-being, effective performance, creative problem-solving, and deep or conceptual learning' (Deci & Ryan, 2008: 182).

Motivation

Bakar (2014:723) asserts that motivation influences how much time and energy learners devote to learning and how long they will persist to complete a task. The lack of motivation, on the other hand, is an obstacle in learning and a reason for the decline of education standards (Awan, Noureen & Naz, 2011). When learners lack academic motivation or are demotivated to learn, both teaching and learning activities are negatively affected. A demotivated learner is generally uninterested in learning and has a strong interest in non-academic activities (Bannatyne, 2003). Motivation is the inborn potential power of human beings that energises, directs and sustains behaviour and is a trigger that transforms thoughts into action (Wang, 2007; Ormrod, 2008). Learning cannot take place without some form of inner determination, purposeful commitment or motivation (Rehman & Haider, 2013). Every learner possesses some form of motivation, whether it is towards school activities, extramural activities, being part of a peer group or participating in mischievous activities.

Motivation is fundamental to successful construction of knowledge, self-knowledge and academic achievement (Gbollie & Keamu, 2017). Motivating resistant, indifferent, reluctant or recalcitrant learners is challenging, especially in a poor area where families have submitted to hopelessness, drugs, crime, prostitution and social dependency. Identifying and providing motivation in such situations is a difficult and time-consuming task that requires considerable effort (Rehman & Haider, 2013). When considering learners' motivation to assimilate and own new knowledge, it is important to identify precisely the type of motivation they respond to best.

In their self-determination theory, Deci and Ryan (1985-2000) provide clarity on the different types of motivation. They distinguish between autonomous and controlled motivation. Autonomy involves acting voluntarily and the opportunity to experience a sense of choice (Gagné & Deci, 2005); intrinsic motivation is an example of autonomous motivation. On the other hand, controlled motivation involves acting under pressure when an individual is compelled or obliged to engage in a certain action (Hagger et al., 2014: 566). Autonomous motivation and controlled motivation are in contrast to amotivation, which involves a complete lack of desire to apply effort (Howard et al., 2016).

Autonomous motivation

Intrinsic motivation is a form of autonomous motivation which is considered by Ryan and Deci (2000) to be the highest and ideal type of motivation. Ryan and Deci (2000: 56) note that 'intrinsic motivation is the doing of an activity for its inherent satisfaction, for the fun or challenge entailed, rather than because of external pushes, pressures, or rewards'. In a school context, intrinsically motivated behaviour is manifested when learners are motivated to learn on their own, without external rewards or prompts, and gain pleasure and satisfaction from their performance (Deci et al., 1991; Deci, Olafsen & Ryan, 2017). High-quality learning and creativity are a result of intrinsic motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2000) because learners are ready to own, acquire and re-formulate knowledge out of a spontaneous enthusiasm and hunger for it. Working with intrinsically motivated learners is an ideal experience for teachers because they are so enthused about their area of interest that they do not need to be disciplined or watched. For them, the work itself is rewarding and they derive pleasure and a sense of satisfaction from working on a task (Davids, 2010).

Controlled motivation

Extrinsic motivation is a form of controlled motivation which, in contrast to intrinsic motivation, is not performed out of interest but because learners are encouraged towards some separable consequence (Deci et al., 2017). Tasks or activities are performed because of an instrumental value and not because it is interesting and enjoyable: 'The extrinsically motivated student normally wants the good grades, money, or recognition that particular activities and accomplishments bring' (Ford & Roby, 2013: 102). Teachers do not always comprehend the importance of extrinsic motivation: many teachers perceive extrinsic motivation as a reward for good behaviour and punishment as the correct penalty for bad behaviour.

Ryan and Deci (2000) argue that although extrinsic motivation is understood as a weaker type of motivation, it is essential for teachers who cannot always rely upon intrinsic motivation to develop extrinsic motivational teaching strategies. Many of the tasks that teachers want their students to perform are not intrinsically interesting or enjoyable. When learners perceive a task to be uninteresting, difficult or irrelevant, they may neglect to engage with or complete the task or become academically disengaged (Legault, Green-Demers & Pelletier, 2006).

Conceptual Framework

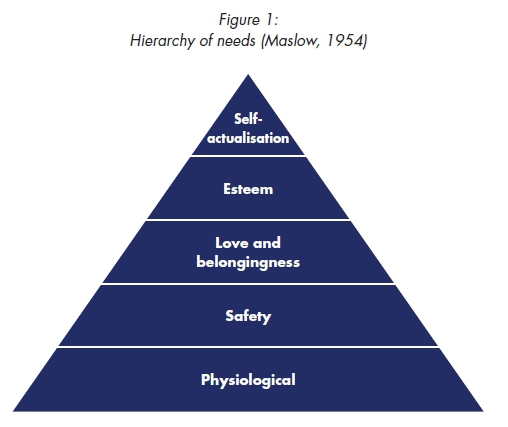

This study made use of two theories: Maslow's (1943-1954) theory of human motivation as well as Deci and Ryan's (1985, 2000) self-determination theory (SDT). These two theories intertwine as both explore human motivation and the role played by human needs in motivation. Maslow's theory of human motivation places human needs in a five-level hierarchy that humans strive to satisfy; one level leading up to the next in a pyramidal structure of attainment and personal fulfilment. Maslow describes the different needs learners are motivated to satisfy in order to reach the ultimate goal of self-actualisation: physiological needs, safety, love and belongingness, and esteem.

According to Maslow (1943; 1954; 1970), to be motivated towards achieving at your full potential, these needs must first be satisfied. This theory was used to establish a link between the motivational needs described by Maslow and what learners explain as their motivation to learn, to determine what needs in the hierarchy learners have difficulty satisfying, and how these motivational needs affect their motivation to learn. For learners to commit themselves to achievement, they need to take the initial steps to succeed academically and to try to achieve status within the esteem needs. They need to have satisfied their fundamental physiological needs, safety needs and their yearning for love and belonging. The ideal is for learners to reach and satisfy the need for self-actualisation so that they are able to realise their potential and achieve to the best of their abilities. This observation links with the theory of Deci and Ryan (1985, 2000) regarding the psychological needs that learners will be motivated to satisfy in order to gain self-determination in their academic work. The concern of the theory is the inherent motivation of human beings and how humans internalise motivation to become self-determined.

Deci and Ryan (1985, 2000) focus on two different types of motivation: intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. These types, largely determine the origin of behaviour towards academic activities. The theory considers these two types of motivation as a continuum that extends from extrinsic to intrinsic motivation. Motivation towards a task becomes an embedded part of the learner's psyche. This belief is described as internalisation and it defines how an individual's deepest motivation or behaviour can range from being unwilling (amotivation) to compliant through external means (passive compliance), to active personal commitment (Ryan & Deci, 2000). The SDT suggests three basic psychological needs that are innate in humans: competence, relatedness, and autonomy. In order to facilitate the internalisation process, these needs should be relatively satisfied. Competence involves the need to feel effective and capable of attaining various outcomes in a given situation (Legault, 2017). Learners have the need to feel competent when engaging with others. Relatedness involves the need to connect and develop secure and satisfying relations with others (Legault, 2017). Autonomy refers to taking responsibility for one's own actions. Learners need a sense of control over their learning and want to engage in learning activities of their own volition and enthusiasm for the knowledge area. All these needs interact with one another and constitute self-determination. The SDT helps to understand what basic psychological needs learners have to satisfy to gain intrinsic motivation.

Four types of extrinsic motivation emanate from the self-determination theory which results from the internalisation process: External regulation, Introjected regulation, Identified regulation and Integrated regulation. These types of extrinsic motivation exhibit the degree to which autonomy is experienced by learners. They range from External regulation which is considered the least self-determined and determining type of extrinsic motivation, to Integrated regulation, the most autonomous form of extrinsic motivation, since the regulatory process is completely integrated with the learner's sense of self (Ryan & Deci, 2000). When the regulatory processes are integrated, the behaviour is an expression of who the person is, what is important to, and valued by, the individual. Learners perform tasks willingly and of their own because the work is important to them.

METHODOLOGY

This study is set within an interpretive paradigm. An interpretive paradigm allows the researcher more scope to investigate issues that influence and characterise academic motivation; to gain a better understanding of factors affecting Grade 12 learners' motivation to learn. This study adopted a phenomenological design and deployed a strictly defined and adapted type of qualitative research methodology, and applied recognised qualitative methods to collect data. Qualitative research seeks to establish how individuals make sense of, or interpret, phenomena in order to understand the social reality of individuals (Mohajan, 2018). Phenomenological studies are concerned with describing in-depth understandings and meanings of individuals' lived experiences about certain phenomena (Creswell, 2013).

A purposive sampling method was used to select the sample for the interviews. Purposive sampling is the process by which a researcher purposefully selects a sample, based upon its characteristics (Pascoe, 2014). This sampling method was chosen as the most appropriate method because it allowed the researchers to include a variety of participants based upon certain characteristics representative of the population. A sample of 10 Grade 12 learners was selected: five male learners, and five females. These learners ranged from 17 to 18 years of age. In this specific year, all Grade 12 learners were Coloured learners.

The learners for the sample were identified from a pilot study the main researcher conducted, to gain a social and academic profile of the Grade 12 learners. Participant learners were selected to capture a fairly diverse academic and social background profile, and the result was 10 learners with the following characteristics:

• One learner was selected because this learner was the top Grade 12 learner at the school and lived with a single parent in low socio-economic conditions.

• One learner lived in the school's student residence and maintained a relatively high academic performance.

• One learner was selected based upon high academic performance and because the learner lived with a single parent.

• One learner lived in a neighbouring town with both parents in relatively good socio-economic conditions but performed below average.

• One learner lived with both parents in relatively good socio-economic conditions but performed below average.

• Three learners were selected who performed at an average level and lived in low socio-economic conditions with their grandparents.

• Two learners were selected who performed at an average level and were drawn from a low to middle class socio-economic background.

Six Grade 12 teachers and three school management team (SMT) members were selected to provide insight into teachers' and management's understanding of Grade 12 learners' academic motivation, and factors that motivate or demotivate learners to learn at this school. The SMT members included the principal and the two deputy principals who are also Grade 12 teachers. The remainder of the six teachers in the sample were selected based upon their teaching experience and the different subjects they teach.

The use of a small, carefully selected sample allowed the researcher to devote more time to participants, so as to excavate the contextual situations that affect learner motivation identified by participants, such as the home, the classroom, teachers, poverty, hunger, lack of computer access or a place to study undisturbed. This study is concerned with the motivation of Grade 12 learners and seeks to explore factors affecting their motivation to learn.

The study was conducted using semi-structured interviews with open-ended questions for all learners. This interview method allowed the researchers to probe questions and dig more deeply into learners' responses, to gain a better understanding of factors that motivate or demotivate learners to learn at a quintile 3 secondary school. The researchers ensured that all the questions were answered by elaborating upon questions or rephrasing questions to ensure that the participants understood the questions and to eliminate potential bias answers. The interview schedule was arranged, starting with questions pertaining to learners' backgrounds, to deeper questions relating to personal issues affecting motivation at their home and school environment. All learners were interviewed using the same interview schedule as a guide. Teachers and SMT members were interviewed through a Focus Group.

Qualitative researchers choose the concepts 'trustworthiness', 'rigour' and 'quality' in the qualitative paradigm to establish validity and reliability which are associated with quantitative research. Trustworthiness can be achieved by ensuring the credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability of the study (Gunawan, 2015). Credibility refers to how accurately the researcher interprets the data provided by participants (Koonin, 2014). This credibility indicates whether results of the study are believable from the perspective of the participants in the research. Credibility was ensured by collecting data that were relevant to the research questions. Participants were made to feel at ease during the interview process and were ensured that they were free to express themselves in total confidentiality; so that the data truly reflected their opinions and feelings. To further ensure credibility of the findings, the researchers applied the use of source triangulation which involves reliance upon various informants so as to verify individual opinions and experiences against others (Shenton, 2004). In this study, source triangulation was achieved by interviewing learners, teachers and the SMT. Data collection methods were triangulated by conducting individual interviews with Grade 12 learners and a focus group interview with Grade 12 teachers and the SMT. This process allowed the researcher to construct a rich overview and understanding of the attitudes, needs and behaviours relating to learners' academic motivation, based upon the contributions of various participants.

The researchers ensured construct validity by virtue of having spent enough time in the context of the participants and respecting the context of the study. The researchers were sufficiently steeped in the culture, mores and language of the school community. It was therefore possible to detect nuances in the language, as well as to comprehend the significances of what was not stated overtly. As the researchers were familiar with the participants' various learning profiles and circumstances generally, they were able to interpret facial and bodily expressions when learners responded to sensitive questions and the researchers were able to adapt questions quickly to avoid any discomfort, awkwardness or pain which the questions might otherwise have caused.

Transferability and dependability were enhanced by providing thick descriptions of the research design, data collection methods and procedures. According to Pitney (2004), dependability is based upon the question of whether the findings are reasonable, based on the data collected and not whether similar findings can be reproduced by another researcher.

To ensure confirmability, the researcher made sure that the findings objectively represent the results of the explanations and experiences of participants, and not the preference of the researcher. When reporting upon the data, the researcher included interviewees' actual words. Data from different sources were triangulated to confirm the responses of participants.

Ethical considerations were adhered to. Permission was granted by the Western Cape Education Department to conduct the research at the secondary school. All participants were informed regarding the purpose of the study, the value of their contribution, how the findings were to be used and their contribution to the field of knowledge. Details of learners were provided by the school with the assurance that all information would be kept confidential. All participants were informed that their details and the information provided would remain confidential, and anonymity was maintained throughout the study. Participants signed a consent form agreeing to participate in the study voluntarily without any rewards. Participants under 18 were given a consent form to be completed and signed by them and their parents or guardians to grant permission to participate in the study. All participants were made aware of their right to withdraw from the study at any time, or withdraw any data provided by them if they so wished.

Data were analysed using an inductive content analysis approach which indicated that the researchers garner raw data and allows themes to emerge, without attempting to fit the data to suit a preconceived conceptual framework (Bezuidenhout & Cronje, 2014). The inductive approach allowed the researchers to include all key themes that emerged from the data. An open coding method was used to identify the themes. The researchers examined several transcripts in detail, identified common data and created codes to link these related patterns in the data. Atlas.ti version 7 was used as a tool to identify the themes and patterns, and created codes using the build in coding function. The conclusion provided the researchers with insight into motivation of learners under similar conditions or backgrounds.

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

Four themes were identified in the analysis of the data collected from participants, namely: breaking the cycle of poverty, parental involvement, acknowledgement, and enjoyment of subjects. These themes are presented with reference to the actual responses of the participants. The literature and conceptual framework were linked to the findings in order to discuss and interpret the themes. Although findings from this study cannot be generalised, they can be related to other learners with similar conditions.

Breaking the Cycle of Poverty

The learners responded that the poor socio-economic conditions at home influenced their motivation to learn. Some learners responded that the living conditions at home demotivated them to learn. They lived in relatively small houses along with many family members that included young siblings and at times members of the extended family. Consequently, finding a place where learners could learn and study in silence was seldom possible. One learner mentioned,

Our house is very small and my siblings are very active in the house during the day when I want to study.

Another learner remarked,

I study late at night when everybody is asleep, then the next day I'm tired and unproductive at school.

Many breadwinners were single mothers or grandparents who struggled to make ends meet. These breadwinners often had to provide for the entire extended household and at times struggled to put food on the table. Learners often experienced difficulty learning on an empty stomach. A learner noted,

I come to school hungry and then cannot focus in class...I hear the words, but nothing goes in.

A few learners remarked that hardship and social deprivation motivated them to work harder at school in order to get out of their current living conditions. One learner stated,

Seeing how hard my mother as a single parent works to look after me makes me want to work harder so that I can give her a better life.

Another learner mentioned,

I work as hard as possible to get good marks so that I can get out of the conditions that we live in. I don't have to live in these conditions for the rest of my life.

It is evident from the responses that some Grade 12 learners attended school on an empty stomach due to lack of food at home. When learners sit in class craving food, they struggle to focus and become demotivated to learn. To address this challenge, the Department of Basic Education (DBE) developed a National School Nutrition Program to provide learners with meals from the school feeding scheme at quintile 1-3 schools (Munje & Jita, 2019). Similarly, systems have been put into place in the UK to provide meals to learners from low-income families (World Food Programme, 2013). This predicament is thus not unique to South Africa. Munje and Jita (2019) note that too often in SA schools, meals are not available at the scheduled time and this results in an increase in learner anxiety and hinders concentration and learning abilities.

Learners struggled to study at home during the day due to various distractions and had to catch up with their studies at night; consequently, learners often lacked sufficient sleep. These learners were frequently exhausted or sleepy in class, which resulted in them being demotivated to learn at school. They were, in many cases, more motivated to satisfy the need to sleep than to learn. Such learners struggled to focus on any learning, which in that situation was not a priority for them. In line with Maslow's theory, it is evident that the lack of basic needs such as food and adequate sleep emanated from the data as reasons for learners' demotivation. These needs, according to Maslow, have to be satisfied first before learners can be motivated towards higher planes of existential significance. It can, therefore, be inferred that learners who have satisfied their physiological needs are more likely to be motivated to learn than their counterparts who are struggling to satisfy their physiological needs. Learners from poor households are limited from functioning at higher levels because they are forced by poverty to devote their time struggling to satisfy physiological and safety needs, leaving them little time or energy to develop self-respect or their own potential (Dos Reis, 2007). These negative and demoralising factors render it difficult for learners to fulfil their goal of escaping the degrading cycle of historically imposed poverty, exploitation and hardship.

Living under these difficult and unjust socio-economic conditions, one might expect learners to be universally demotivated to learn. Instead, the data revealed that Grade 12 learners were in many instances motivated by these very conditions to learn at school as a means of escaping degradation, suffering and humiliations; in order to live a better life in the future. This observation of learners' positive reaction to destitution is in line with the findings of a study by Igwe (2017) which reveals that learners are frequently motivated to achieve academically in order to free themselves from the confines and sufferings of poverty. Identified regulation as a form of extrinsic motivation, according to the SDT, was most relevant in these situations. Learners accept the regulatory process as their own and begin to value the consequences and significance of their own behaviour (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Though some learners were found to become demotivated, others became motivated by similar conditions. In line with the SDT, these motivated learners have identified the value and personal importance of learning for them. They realised that studying at school was the only viable and realistic hope of avoiding the hardships of their parents' lives and of escaping from their own crowded and poor living conditions.

Parental Involvement

The majority of the learners indicated that they were motivated to learn by parents who were involved in their academic activities; by checking homework, attending parent-teacher meetings and enquiring about their academic performance from teachers. A learner remarked,

My mother and grandmother will ask me every day if I have schoolwork.

Learners revealed that they were motivated by their family; supporting them in their education and going out of their way to provide them with the necessary facilities that they needed to learn. A learner mentioned,

It motivates me to know that my mother would do anything for me when it comes to my schoolwork.

Another learner concurred,

...they will never think twice to buy things I need for school.

On the other hand, lack of parental involvement was perceived by many learners in this study to be a lack of care, concern and support from parents who seemed uninterested in their schoolwork. Parent apathy was found to demotivate learners to learn; that is within the parameters of this selected study. A learner attested,

nobody checks my homework or worries about my schoolwork.

One might have expected that learners preferred to be left alone to work on their own and take responsibility for their own work, but the opposite emerged from the data. Learners desired to learn in a controlled environment and became demotivated when nobody checked their homework or when nobody enquired about their progress or activities at school. Usher and Kober (2012: 4) agree that learners develop 'feelings of competence, control, curiosity, and positive attitudes about academics' when parents create an environment at home that motivates learning and remain actively involved in their children's education. Seemingly, if parents are concerned about learners' schoolwork, it is an indication to learners that they are interested and concerned about their future. Parental concern could thus be cited as a motivating factor.

From the participants' remarks, it is clear that learners were motivated to learn when their parents were involved in their schoolwork. This involvement includes physically helping learners with homework, attending school functions, encouraging them to learn and providing positive feedback. When parents or guardians were involved in learners' academic and social lives, learners perceived them as interested, and concerned for their future and tended to adopt similar concerns and commitment to study. Learners feel connected to their parents and guardians and experience a sense of belonging. These acts of love, care and involvement contribute to the satisfaction of the need for relatedness according to the SDT. This stems from satisfying the love and belonging needs according to Maslow. Relatedness is one of the needs that facilitate the internalisation process, in addition to the autonomy and competence needs (Niemiec & Ryan, 2009). In line with Niemiec and Ryan's study, these learners are inclined towards identified and integrated regulation. They were motivated to learn on their own because they had identified the value of learning. The value of learning for these learners was a means of showing appreciation and love to their caregivers. They were therefore motivated to return the love and care by making their parents or guardians proud through learning in order to achieve academically. Although this is a form of controlled motivation, it is relatively self-determined because learners do it willingly, even if partially for personal reasons. Such action towards the acquisition of knowledge is more authentic and self-fulfilling than action driven by the threat of punishment or the lure of reward. However, these learners have not completely integrated the regulation of their motivation. There is a possibility that if their parents neglect to show interest and care for their academic work, they might become demotivated and would require external regulation to motivate them to learn.

Acknowledgement

Learners mentioned that receiving positive feedback, rewards and being recognised for their performance motivates them to learn and maintain high academic performance. Prizegiving (diploma evenings) was one of the factors highlighted by the majority of the learners as motivation to learn. One learner mentioned,

Just to receive a certificate for good performance and being able to show everybody at home motivates me again to do better and to get a certificate again.

On the other hand, when learners were not acknowledged for their hard work and performance, they became demotivated to learn. A learner revealed,

I put in so much and I feel that I've done well, but when I get home my mother will say I could've done better.

Another learner mentioned,

My father will never tell me he is proud of me.

From the participants' views, one can establish an important link between acknowledgement, and the motivation to learn and achieve. The data revealed that many learners were motivated to learn in order to gain an external reward and recognition for their performance by peers, parents or teachers. Learners craved recognition; they wished others to regard them as intelligent and hardworking. This craving is aligned strongly with Maslow's (1954) theory of human needs: learners, in their effort to satisfy their needs for esteem and social recognition, desire reputation, status, attention, importance or appreciation. Learners want to be acknowledged for their efforts to gain status and respect in the eyes of those in their family, learning or work environment and society at large. This impulse was evident from observing that learners who receive recognition and who gained a reputation for good performance, were further motivated to learn in order to uphold and increase their standing in the community. In agreement with the SDT, competency needs play an important role in the motivation of these learners. The SDT suggests that learners desire to be seen by others as competent and want to feel competent when engaging with other learners. These learners experience a sense of competence when they are acknowledged by others for their good performance. When they satisfy their need for competence, they are likely to internalise their motivation, learn out of their own volition and exhibit attributes of self-determination.

A corollary to this point was that data from this study indicated that learners whose efforts were not recognised at home often became demotivated to learn. In terms of Maslow's theory, these learners experienced difficulty satisfying their need for esteem. To satisfy this need, learners selected for this investigation at a quintile 3 semi-rural school often resorted to seeking attention and recognition in less orthodox, non-academic or even undesirable areas; further diverting their focus away from a ladder of achievement and steady progress in learning. It is therefore evident from the responses that learners who are acknowledged for their achievements are more motivated to learn than those who do not receive the necessary acknowledgement.

Enjoyment of subjects

A few of the learners reported that they were motivated in subjects that they enjoyed and found interesting. A learner commented,

I'm motivated in Physical science, because this is one of the subjects I enjoy.

Another learner had a similar response,

I love computers; I find the subject interesting.

One learner highlighted,

Afrikaans I would learn on my own, not because I have to, but because I enjoy it.

Another learner mentioned,

I like challenging problems. I enjoy struggling with a difficult problem so that when I solve it I feel proud of myself and that motivates me to continue trying.

On the other hand, when learners did not enjoy the subject, they became demotivated in the subject. A learner made the following comment:

I feel like I have to force myself to study Life Sciences because I don't really enjoy learning this.

It is clear from the responses that when learners found subjects interesting and enjoyable, they were more motivated to learn and study for subjects; of their own volition and enthusiasm for new knowledge. Schukajlow and Krug (2014) note that finding connections with a subject or building up an interest in one area is key for sparking and sustaining a learner's short-term and possibly long-term love of a particular area of knowledge. Finding such a connection and spark of enthusiasm for one particular area or point of fascination is strongly linked to academic achievement. In line with the SDT, the study found a link between the enjoyment of subjects, the needs for competence and autonomy and learners' motivation to learn. When learners find subjects interesting and enjoyable, they tend to work harder to understand the work and feel proud of themselves when completing a difficult task. They, therefore, exhibit a sense of satisfaction towards their need for competence. These learners feel competent when engaging with the work and with others and attempt more challenging tasks, because they believe in their abilities to master the work.

When learners enjoy the work, they develop a sense of autonomy. In this instance, they take responsibility for their own actions and do not need a controlled regulation, since they will learn on their own because they enjoy what they are doing and find interest in acquiring knowledge. It is apparent that these learners have relatively satisfied the needs for competence and autonomy, which is essential in facilitating the internalisation of their motivation to learn. These learners learned because they were authentically driven by a passionate interest in a certain subject - they enjoyed learning new content, persisted until they understood the challenging content, and wanted to figure out solutions for challenging problems on their own. This pattern of knowledge acquisition is aligned with findings from a study conducted by Singh (2011) who claims that intrinsically motivated learners enjoy challenges, and do not readily give up when facing challenges; they are likely to persist and complete assigned tasks. From the findings of this investigation, it may be implied that in confirmation of the SDT, these learners were intrinsically motivated.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATION

Motivation, whether controlled or autonomous, is undoubtedly a crucial part of learning and academic success. This study found that learners from impoverished households, who have managed to satisfy their basic needs, were motivated to learn as a means to escape their harsh living conditions and achieve a better future. The study further revealed that when learners were acknowledged for academic achievements, they became more motivated to learn to continue receiving these acknowledgements. When parents were involved in learners' schoolwork, learners became motivated to learn to make their parents proud as a means of returning the love and care they perceived when parents were involved in their studies. Learners who found enjoyment in subjects often learned from their own volition because they enjoyed the work, found the work interesting and wanted to increase their knowledge.

The compelling factor that emerged from the findings was that these motivating factors allowed learners to identify the purpose and benefit of learning for them; whether it was working towards a better future to please their parents, gain recognition, or internal satisfaction. Once they understood why they had to learn, they often appreciated the value of learning. Learners should thus be encouraged to set goals that are relevant to their circumstances and interest so that they can comprehend the greater purpose of learning for their future. Parental involvement and academic acknowledgement should be encouraged as it adds intrinsic value to learning. Learners must be provided opportunities to be acknowledged for their academic abilities, to be seen as competent, and to be valued by others. Teachers and parents should be cognisant of factors that contribute to learner motivation and need to provide clarity and indicate to learners, in the classroom and at home, how learning would add value to aspects of their lives which coincide with their life goals.

REFERENCES

Awan, R., Noureen, G. & Naz, A. (2011) A Study of Relationship between Achievement Motivation, Self concept and Achievement in English and Mathematics at Secondary level. International Education Studies 4(3) pp.72-78. [ Links ]

Bakar, R. (2014) The effect of learning motivation on student's productive competencies in vocational high school, West Sumatra. International Journal of Asian Social Science 4(6) pp.722-732. [ Links ]

Bannatyne, A. (2003) Student characteristics. http://www.bannatynereadingprogram.com/BP13CHAR.htm (Accessed 07 July 2015).

Bezuidenhout, R. & Cronje, F. (2014) Qualitative data analysis. In F. Du Plooy-Cilliers, C. Davis & R. Bezuidenhout (Eds.) Research matters. Cape Town: Juta. [ Links ]

Creswell, J.W. (2013) Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Davids, R. (2010) Practices which contribute towards grade 6 learners' reading motivation (Unpublished master's dissertation). Cape Peninsula University of Technology, Mowbray, South Africa. [ Links ]

Deci, E.L. & Ryan, R.M. (1985) Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum. [ Links ]

Deci, E.L. & Ryan, R. M. (2008) Self-Determination Theory: A Macrotheory of Human Motivation, Development, and Health. Canadian Psychology 49(3) pp.182-185. [ Links ]

Deci, E.L., Olafsen, A.H. & Ryan, R.M. (2017) Self-determination theory in work organizations: The state of a science. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 4(1) pp.19-43. [ Links ]

Deci, E.L., Vallerand, R.J., Pelletier, L.G. & Ryan, R.M. (1991) Motivation and Education: The Self-Determination Perspective. Educational Psychologist 26(3 & 4) pp.325-346. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education. (2017) The 2017 National Senior Certificate Schools Performance Report. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Dos Reis, K.M. (2007) The influence of gangsterism on the morale of educators on the Cape Flats, Western Cape (Unpublished master's dissertation). Cape Peninsula University of Technology, Cape Town, South Africa. [ Links ]

Ford, V.B. & Roby, D.E. (2013) Why do high school students lack motivation in the classroom? Global Education Journal 2013(2) pp.101-113.

Gagné, M. & Deci, E.L. (2005) Self-determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior 26 pp.331-362. [ Links ]

Gbollie, C. & Keamu, H.P. (2017) Student Academic Performance: The Role of Motivation, Strategies, and Perceived Factors Hindering Liberian Junior and Senior High School Students Learning. Education Research International 2017 pp.1-11.

Grant, D. (2013) Background to the national quintile system. http://wced.pgwc.gov.za/comms/press/2013/74_14oct.html (Accessed 7 September 2016).

Gunawan J. (2015) Ensuring Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research. Belitung Nursing Journal 1(1) pp.10-11. [ Links ]

Hall, K. & Giese, S. (2008) Addressing quality through school fees and school funding. In S. Pendlebury, L. Lake, & C. Smith (Eds.) South African child gauge 2008/2009 pp.35-40. Cape Town: Children's Institute, UCT. [ Links ]

Hagger, M.S., Hardcastle, S.J., Chater, A., Mallett, C., Pal, S. & Chatzisarantis, N.L.D. (2014) Autonomous and controlled motivational regulations for multiple health-related behaviors: between- and within-participants analyses. Health Psychology & Behavioural Medicine 2(1) pp.565-601. [ Links ]

Horgan, G. (2007) The Impact of Poverty on Young Children's Experience of School, York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation. [ Links ]

Howard, J., Gagné, M., Morin, A.J. & Van den Broeck, A. (2016) Motivation profiles at work: A self-determination theory approach. Journal of Vocational Behavior 95 pp.74-89. [ Links ]

Igwe, I.O. (2017) Influence of socio-economic status of parents' income and motivation on the academic achievement of chemistry students. International Journal of Current Research 9(4) pp.49627-49633. [ Links ]

Klatte, M., Bergstrôm, K. & Lachmann, T. (2013) Does noise affect learning? A short review of noise effects on cognitive performance. Frontiers in psychology4(578) pp.1-6, doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00578 [ Links ]

Koonin, M. (2014) Validity and Reliability. In F. Du Plooy-Cilliers, C. Davis & R. Bezuidenhout (Eds.) Research matters. Cape Town: Juta. [ Links ]

Legault, L., Green-Demers, I. & Pelletier, L. (2006) Why do high school students lack motivation in the classroom? Toward an understanding of academic amotivation and the role of social support. Journal of Educational Psychology 98(3) pp.567-582. [ Links ]

Legault, L. (2017) Self-determination theory. In V. Zeigler-Hill & T.K. Shackelford (Eds.) Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences pp.1-9. New York: Springer. [ Links ]

Maslow, A.H. (1943) A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review 50(4) pp.370-396. [ Links ]

Maslow, A.H. (1954) Motivation and Personality. (3rd ed.) New York: Harper & Row. [ Links ]

Maslow, A.H. (1970) Motivation and Personality. (2nd ed.) New York: Harper & Row. [ Links ]

Mohajan, H.K. (2018) Qualitative research methodology in social sciences and related subjects. Journal of Economic Development, Environment and People 7(1) pp.23-48. [ Links ]

Munje, P. & Jita, L. (2019) The implementation of the school feeding scheme (SFS) in South African Public primary schools. Educational Practice and Theory 41(2) pp.25-42. [ Links ]

Nel, W.N. (2000) Faktore wat verband hou met die leermotivering en leerhouding van leerders in sekondêre skole in die Upington omgewing. (Unpublished master's dissertation). University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa. [ Links ]

Niemiec, C.P. & Ryan, R.M. (2009) Autonomy, competence, and relatedness in the classroom: Applying self-determination theory to educational practice. Theory and Research in Education 7(2) pp.133-144. [ Links ]

Ormrod, J.E. (2008) Educational psychology: Developing learners. 6th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Pascoe, G. (2014) Sampling. In F. Du Plooy-Cilliers, C. Davis & R. Bezuidenhout (Eds.) Research matters. Cape Town: Juta.

Pitney, W.A. (2004) Strategies for Establishing Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research. Athletic Therapy Today 9(1) pp.26-28, January. [ Links ]

Rastegar, M., Akbarzadeh, M. & Heidari, N. (2012) The Darker Side of Motivation: Demotivation and Its Relation with Two Variables of Anxiety among Iranian EFL Learners. International Scholarly Research Network 2012 pp.1-8.

Rehman, A. & Haider, K. (2013) The impact of motivation on learning of secondary school students in Karachi: An analytical study. Educational Research International 2(2) pp.139-147. [ Links ]

Ryan, R.M. & Deci, E.L. (2000) Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology 25 pp.54-67. [ Links ]

Schukajlow, S. & Krug, A. (2014) Are interest and enjoyment important for students' performance? In C. Nicol, S. Oesterle, P. Liljedahl & D. Allan (Eds.) Proceedings of the Joint Meeting of PME 38 and PME-NA 36. 5th ed. Vancouver, Canada: PME. [ Links ]

Shenton, A.K. (2004) Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information 22 pp.63-75. January 6.

Singh, K. (2011) Study of Achievement Motivation in Relation to Academic Achievement of Students. International Journal of Educational Planning & Administration 1(2) pp.161-171. [ Links ]

Usher, A. & Kober, N. (2012) Student Motivation - An Overlooked Piece of School Reform. Center on Education Policy. Washington: The George Washington University. [ Links ]

Wang, Y. (2007) On the cognitive processes of human perception with emotions, motivations, and attitudes. International Journal of Cognitive Informatics and Natural Intelligence 1(4) pp.1-13. [ Links ]

World Food Program. (2013) State of School Feeding Worldwide. https://www.hst.org.za/publications/NonHST%20Publications/wfp257481.pdf (Accessed 01 February 2021).

1 Date of submission 26 June 2020; Date of review outcome: 18 November 2020; Date of acceptance 7 January 2021

2 ORCID: 0000-0002-8254-6888

3 ORCID: 0000-0002-0877-7848

4 ORCID: 0000-0001-7606-4586.