Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

The Independent Journal of Teaching and Learning

On-line version ISSN 2519-5670

IJTL vol.17 n.1 Sandton 2022

ARTICLES

Work Integrated Learning (WIL) model – A win-win process between university, postgraduate business students and industry

Isolde LubbeI; Goran SvenssonII

IUniversity of Johannesburg, South Africa3

IIKristiana University, Norway4

ABSTRACT

A project-based work integrated learning (WIL) model that is a match between business postgraduate programmes, business postgraduate students and industry partners can increase employability and job opportunities. This study is based on a qualitative and inductive approach and a longitudinal study initiated in 2014 and evaluated in early 2020. Based on empirical findings in a South African setting, the model reflects that in gaining a sense of the environment via a WIL partnership, postgraduate students are better able to connect innovatively to grow the business. A win-win situation can be achieved where a university, business postgraduate students and industry interact to achieve consensus and a match between industry needs and educational skills. The challenges of companies to find and employ appropriately skilled employees among business postgraduate students can be met through the use of the model. The model contributes to WIL knowledge in a business disciplines. This study presents the argument that if universities and industry partners are able to match their needs, connect, collaborate and engage successfully, postgraduate job opportunities and employability could increase.

Keywords: work integrated learning (WIL), project-based learning, win-win process, business graduate job opportunities, employability

INTRODUCTION

Work integrated learning (WIL) is a process whereby students transfer theoretical knowledge into practice. Universities, industry, and students regard graduate skill, employability and job opportunities as critical success factors for degree programmes (Ohei & Brink, 2019; Ibrahim & Jaaffar, 2017) and WIL enhances a graduate's chances of employability and job opportunities (Freudenberg, Brimble & Vyvyan, 2010). Through building a student's practical and basic skills, graduates can become more employable and WIL is being respected as an important instrument to enhance graduate job opportunities (Ohei & Brink, 2019; Ibrahim & Jaaffar, 2017; Hamilton et al., 2015). WIL also improves learning outcomes by enhancing personal and cognitive development, student learning, and work-readiness (Smith, Ferns & Russell, 2016), reinforce skills learned, and transfer skills from one context to another (Crebert et al., 2004). The issue is that most WIL studies have tended to focus on undergraduate students' work-integrated experiences, and most WIL models do not easily translate to postgraduate programmes (Karim, Campbell & Hasan, 2020; Campbell, Stewart & Karim, 2018). The compressed nature of a postgraduate degree makes industry involvement difficult to incorporate, but the benefits far outreach the constraints.

One of the reasons graduates do not find jobs is that employers look for not only a university qualification, but also some form of work experience and practical 'on-the-job' knowledge (BizTrends, 2017). The South African economy demands experienced and skilled work-seekers. Not having some form of experience makes it difficult for young people to find employment (StatsSA, 2021). For universities or higher education institutions (HEIs), providing these 'practical skills' is not possible if good partnerships between university, industry, and student are non-existent (Henderson & Trede, 2017). HEIs are expected to adopt a 'market-economy-oriented pedagogy' that will equip students to become global citizens (Kalafatis & Ledden, 2013). A gap exists in literature addressing conceptual or empirical research on project-based WIL models and strategies to achieve linkages between universities and industry partners, specifically for postgraduate business graduates.

This research aims to meet the challenges of business postgraduate students entering the labour market; enhance their employability; and improve the match with industry needs. It also aims to assist companies to find and employ appropriately skilled employees among business graduate students. The research question is how a Work Integrated Learning (WIL) Model can establish a win-win process between university, business postgraduate students and industry. The research objective is therefore to describe a WIL-model for business postgraduates.

The study describes a win-win situation where a university, business postgraduate students and industry interact in a quest for consensus and a match between industry needs and educational skills. It contributes to theory by adding to the body of knowledge on WIL and its practical contribution lies in the WIL model presented to attract industry stakeholders and academics to engage in WIL projects. The study is limited to describing the application of a WIL model in business disciplines with postgraduate students.

In a project-based learning approach, the 'project' is central to the learning making sourcing and scoping of the project's key essentials to craft a meaningfully challenging learning endeavour in constructive alignment with its objectives (Vande Wiele et al., 2017).

LITERATURE REVIEW

Industry needs for business managers

According to Branson (2017), there is an element of marketing behind every successful business. Consumers have a desire for products and services that serve their needs, but without marketing, they would not be aware of these (Johnson, 2015; Barwise & Meehan, 2011). Substantial evidence shows that business and marketing, and specifically business functions and tasks such as strategic planning, lead to increased profit margins and ultimately improved business performance and success (La Marca, 2017; Van Scheers & Makhitha, 2016), but this is not possible without skilled business graduates (Melaia, Abratt & Bick, 2008), and specifically business graduates with some form of practical experience (Okoti, 2018; Baker, 2015).

Graduates prefer to find the best job, while employers prefer the best candidate for the job; whether in an emerging economy or a developed economy, employers share common concerns about gaps in graduate skills (McArthur et al., 2017; IOA, 2017; Vaaland & Ishengoma, 2016). Recruiters constantly refer to their need for 'employable' graduates (McArthur et al., 2017) or 'work-ready' graduates (Greenacre et al., 2017). These requirements constitute a good mix of skills that are not only academic and technical, but also include soft skills (Mutalemwa, Utouh & Msuya, 2020; Greenacre et al., 2017; Kausar, 2015), as soft skills contribute to work-ready graduates (Karim et al., 2020; Schlee & Karns, 2017).

Soft skills are defined as the 'interpersonal, human, people or behavioural skills needed to apply technical skills and knowledge in the workplace' (Weber et al., 2009: 356). Business is a challenging, fast-changing, and a dynamic field that requires managers to have the soft skills necessary to constantly adapt, while regularly updating their 'technical skills' (Mutalemwa et al., 2020; Schlee & Karns, 2017; Saeed, 2015). Table 1 presents a summary of soft skills, technical and academical skills proposed in literature as essential to shape 'work-ready' graduates.

Soft Skills

Interpersonal skills are built on good communication skills (Rackova, 2015). Good written communication, oral communication, and presentation skills, with the ability to manage competing priorities and timelines are other important skills that employers are looking for (Mutalemwa et al., 2020; Schlee & Karns, 2017; McArthur et al., 2017). Additional requirements include problem solving skills, project management skills, creativity, the ability to work in teams, the ability to adapt to new technologies, and the willingness to learn, together with conflict resolution skills (Mutalemwa et al., 2020; Hall, 2018; Schlee & Karns, 2017; McArthur et al., 2017; Saeed, 2015; Ince, 2011). Mutalemwa et al. (2020) elaborate that the employers further seek initiative, self-awareness, ethical skills, and stress tolerance. Ince (2011) even proposes that graduates should be taught how to handle an interview, draft a CV, and dress for the workplace. Masole and Van Dyk (2016) propose that graduates should present emotional intelligence, and the ability to persevere towards goals and show resilience to attain success. Iyengar (2015) argues that although all these skills are important for graduates, postgraduate WIL programmes should specifically focus on critical thinking, creative solutions, solving complex problems and to grow managers for the digital world. Gannon, Rodgrido & Santema (2016) add that postgraduate programmes should encourage teamwork, inter-culturally contact, and create opportunities for digitally literate skills to develop.

Table 1 above presents a summary of soft skills proposed in literature. Although educators can assist with technical knowledge and skills and provide opportunities for students to exercise the softer skills, the gap between theory and practice is too wide and must be eliminated if educators are to create the skilled, business managers that industry needs (Krell, Todd & Dolecki, 2019).

Technical and academic business skills

From the actual degree, recruiters expect graduates to have more than academic and/or technical skills, but to interpret complex information, solve problems, apply critical thinking, go beyond reporting and metrics, and to be proficient in a full range of analytical skills (Mutalemwa et al., 2020; Whitler, 2018; Schlee & Karns, 2017; Saeed, 2015). Furthermore, graduates, specifically postgraduates are expected to plan and conduct research, but to interpret the research in such a way that they can identify problems and use the insights gained to develop strategic plans (Ferreira & Barbosa, 2019; McArthur et al., 2017; Greenacre et al., 2017; Kausar, 2015). It is important for postgraduate students to understand concepts, have the breadth of knowledge in their field, be up to date with latest trends and know how to apply knowledge gained (Mutalemwa et al., 2020). The issue is that many recruiters require some form of business 'hands-on' or 'know-how' experience when hiring, but these business postgraduate students are less likely than most to be involved in decision-making while studying (Alharahsheh & Pius, 2021; Keegan, 2017; Kausar, 2015; Baker, 2015).

Students, especially those in postgraduate studies, need opportunities to develop their thinking, research and practical skills, specifically on the strategic aspects of business, in order to engage with potential employers (Mutalemwa et al., 2020; Meza Rios et al., 2018). Strategic thinking is an important skill and companies are in serious need of managers equipped with strategic thinking savvy (Seyed Kalali, Momeni & Heydari, 2015; Moon, 2013). Strategic thinking, heightened by today's market uncertainty and technological turbulence, has become a key management tool. It is essential for setting direction, growing a business and shaping the future goals of that business (Vega, 2018; Haycock, Cheadle & Bluestone, 2012).

The main elements of strategic skills include soft skills, business thinking and practical skills. Strategists need as much social skills as they need intellectual skills (Carucci, 2018). For example, analytical skills, planning and teamwork are not possible if a manager does not have good communication skills, a sense of responsibility and the ability to delegate and resolve conflicts (Mustata, Alexe & Alexe, 2017; Gurchiek, 2010). It is further argued that vision and analytical skills affect the strategic manager's questioning ability positively, and inspire innovation and creativity (Mustata, Alexe & Alexe, 2017; Seyed Kalali et al., 2015; Fodness, 2007). Strategic thinkers are able to recognise and solve problems by defining objectives and developing a strategic action plan to resolve daily challenges. Each objective should be broken down into tasks, while each task is allocated resources, budgets and timelines with measurable standards (Bradford, 2018; Mustata, Alexe & Alexe, 2017; Grecu & Denes, 2017). Table 1 summarises the technical and academic skills proposed in literature.

Strategic skills have to be developed by more than just theoretical teaching; they are better acquired through hands-on experience than classroom learning (Meza Rios et al., 2018; Seyed Kalali et al., 2015). Workplace experience and improving personal skills are a means to enhance the graduates' chances of gaining employment and being work-ready (IOA, 2017). Market turbulence and technological turbulence foster strategic thinking at the organisational level and there is a positive relationship between strategic thinking and performance (Moon, 2013). Work-integrated learning (WIL) models and strategies offer many benefits to all related stakeholders, especially industry, by creating work-ready, business postgraduates as future talent for the global marketplace.

Work-integrated learning (WIL)

WIL is also known as project-based learning or practise-based learning and occurs when there are partnerships between the higher education institution, such as a university, and a business organisation (referred to as 'industry' in this paper) to facilitate learning in providing hands-on experience (Prior et al., 2021). Students engaging in this type of learning, are able to enhance their skills development as well as their professional demeanour required to be a work-ready postgraduate (Clausen & Andersson, 2019). In this study, a project-based WIL adheres to three characteristics: (i) students engage with an industry partner, (ii) students undertake activities for industry, and (iii) students are assessed on these activities. This is different from authentic learning, as authentic learning 'exist[s] along a continuum where WIL encapsulates the learning that occurs in close situation to the experience of work' (Karim et al., 2020: 159). It seems though that universities tend to focus more on undergraduate WIL (Campbell et al., 2018) and that literature on postgraduate studies tend to be few and far in between (Valencia-Forrester, 2019: 389) with benefits for postgraduate WIL not entirely explored (Karim et al., 2020; Ferreira & Barbosa, 2019).

Industry benefits from strategic WIL

University-industry linkages are fast becoming the norm in developed countries and emerging economies (Clausen & Andersson, 2019; Vaaland & Ishengoma, 2016). Agnew, Pill and Orrell (2017) as well as Vande Wiele et al. (2017) argue that partnerships between educators, industry (business) and students are important because all three should share an understanding of the expected requirements and responsibilities and value gained. This multi-stakeholder partnership provides lucrative benefits for all stakeholders, including students, educators, businesses and government (Govender & Wait, 2017; Vaaland & Ishengoma, 2016).

By engaging in WIL models and partnerships with universities, industry benefits from the opportunity to showcase its expertise, brand and organisational culture (Johnson et al., 2016; Vaaland & Ishengoma, 2016). When industry experts join Advisory Board discussions in graduate programmes, they are able to influence skills sets those graduates bring to the workplace. University graduates are the future talent that workplaces seek when recruiting new employees and creating talent pools. Leaders and managers benefit from WIL students who present recruitment and talent scouting opportunities when they showcase their theoretical knowledge of business competencies (Hemmert, Bstieler & Okamuro, 2014; Johnson et al., 2016).

Future-fit graduates present business and industry with fresh ideas, innovative creations and futuristic knowledge, skills, values and attitudes (Jackson, 2015). Graduates are 'techno-savvy', with knowledge on how to access and utilise the latest technological devices and applications in the local, national and global arena. University graduates present businesses with strategies for growth and development, especially to meet future, global market trends (Govender & Wait, 2017). Qualified, professional Gen-X, Gen-Y and Gen-Z talent pools are naturally created by tertiary institutions and are fast becoming sought-after talent in the global strategic sector (Wiedmer, 2015).

Industry benefits by engaging in WIL projects, especially when it employs graduates or commits to internships and graduate empowerment programmes after WIL implementation. WIL industry partners meet national and international skills development and human resource strategic imperatives and may gain tax benefits from engaging with university-industry linkages (Govender & Wait, 2017).

METHODOLOGY

Research Design

This study is based on a qualitative and inductive approach. It is an ongoing longitudinal study, initiated in 2014 and evaluated in early 2020. The process of developing a WIL model between a university and industry partners is based on empirical findings in a South African setting.

Population and Sample

The initiative was set up to meet the challenges of business postgraduate students in the labour market and to improve their employability by enhancing their match with industry needs. It was also designed to assist companies to find and employ appropriately skilled employees among business postgraduate students. It is ultimately about creating a win-win situation where a university, business postgraduate student and industry interact in a quest for consensus and a match between industry needs and educational skills.

Data Collection

The evolutionary stages of the empirically developed project-based WIL model, from inception in 2014 until end of 2019, are depicted in Figure 1. It is evident from the stages implemented, that the project-based learning programme evolved every year and was transformed to better meet and match all stakeholders' (students, recruiters, industry partner and the university) changing needs. To understand the needs and expectations of all parties involved, they need to be involved from the commencement of the project. All stakeholders have to be consulted so that they feel they have influence and a voice to what the outcomes might be and to better manage and match expectations and needs.

Ethical Considerations

Participants in this study were granted strict confidentiality and anonymity. Furthermore, there was no obligation whatsoever to participate, but business postgraduate students, recruiters and industry partners all gave their consent and volunteered in good faith to collaborate in the process of establishing a Work Integrated Learning (WIL) Model to develop a win-win process between university, business graduate students and industry.

To determine needs and expectations from postgraduate students, feedback was gathered in 2020 from participants in the 2018 group (depicted in Table 1), who by this time had had a year of work experience and were better equipped to reflect on the WIL programme. The response rate on interviews was 38% (23 out of 60 students). Of the participants providing feedback, 78% indicated that they are more employable based on the WIL-model and 78% indicated better job opportunities.

FINDINGS

This section reports the findings based on the WIL-model stages applied and described in the previous section. Table 2 structures a summary of the skills and benefits gained from interviewing students on the WIL model. Multiple skills are gained as a result of participation in the programme. Key skills reported were: (i) working under pressure / tenacity, (ii) presentation skills, (iii) team dynamic skills, (iv) conflict resolution skills, (v) problem solving skills / critical thinking skills, (vi) project management skills, (vii) research skills, and (vii) digital business and marketing skills.

The top three skills mentioned by interviewees were firstly (i) the ability to present to a variety of audiences, secondly (ii) to work under pressure were mentioned jointly with applying your project management skills as students had expectations from industry participants, their lecturer and their team members. Jointly in third place (iii) were critical thinking and problem-solving skills and digital business and marketing skills.

There are a range of benefits (Table 2) recorded, such as: (i) skills and confidence to find a job/ internship; (ii) better preparation for the working world; (iii) application of skills to approach work promotions; (iv) application of oneself in various work circumstances; (v) adaption to changing world /new technologies; (vi) exposure to corporate structures and different work environments; (vii) exposure to different brands and a diverse customer base; (viii) 'real work' experience; and (viii) the WIL programme provided career direction to areas of business and marketing preferred or enjoyed more by students. The top benefit mentioned, was that students felt better prepared for the working world.

Participants provided proposals (Table 2) for additions to the programme, such as: (i) increasing students' financial knowledge and specifically practical financial abilities by adding more course work and by exposing students to more industry-specific financial information; (ii) briefing guest speakers before their presentations on specific deliverables (e.g. what their industry is looking for, what they value, how to apply for a job); (iii) removing repetitive messages or module information (lectures to obtain knowledge of what is offered in the entire programme and become less silo focused); (iv) including a sales module or project to make students even more versatile in the job market; (v) ensuring industry participants also provide feedback on the projects and assignments - not just the lecturers; (vi) considering job shadowing opportunities where internships or graduate programme are not an option for the industry partner involved; (vii) including a variety of industry projects, not just for example financial services management and fast moving consumer good management opportunities; and (viii) guard against a silo approach.

DISCUSSION FROM FINDINGS

The authors propose a WIL-model for business graduates based on the feedback gathered from participants and the WIL-model stages outlined in the section of methodology. Current literature assisted in synthesising the steps that were followed to design, develop and implement the WIL model for business postgraduates described above, into the more formal model presented in Figure 2.

Step 1: Determine industry needs

Since the process of obtaining industry input, be it from potential employers (Zakharchenko, 2017; Henderson & Trede, 2017; HRDC, 2017; McArthur et al., 2017) or past students (Atkinson, Coleman, & Blankenship, 2014; Jacques, 2014) is supported by current literature, the WIL model commences by conducting research with WIL stakeholders. To determine what skills the industry requires, educators conduct focus group sessions with current students, in-depth interviews with alumni and formal discussion meetings with selected industry members. Industry experts are invited to serve on the university Industry Advisory Board. Students are asked what skills they expect will be required for job opportunities and which skills they think they still lack. Alumni students are interviewed regarding the skills they would like to have learnt, or learned more about, and what skills, in their experience, the job market requires of graduates in the field of business.

The focus is on constructive feedback regarding where the degree fulfils job environment needs (so that the Department can continue doing this), and where the skills gaps exist. Feedback from students and the Industry Advisory Board includes constructive criticism of softer skills that students can improve on, such as time management, presentation skills, working in groups, and general communication skills. Examples of the latter include how to write a professional email, when to send an email, when to phone and how to adapt when a situation changes. Focus group discussions and Industry Advisory Board meetings also attempt to uncover participants' thoughts on future trends in general and how these will alter the skills sets that will be required in the workplace.

Feedback received from students and the Industry Advisory Board is then communicated to academic curriculum designers, where brainstorming takes place regarding changes that can be implemented immediately and those that need to be planned. It is at this stage that academic requirements need to be considered. The established Curriculum Committee agrees on time pressures and theory requirements regarding specific qualification modifications. Industry experts and business lecturers then collaborate to agree on WIL timelines, skills transfer, relevant assessments and further opportunities. These discussions are confirmed via email to the relevant industry and other partners, and WIL participants.

Step 2: Implement the WIL project

The project requires both educators and the industry partner to agree on time and budget commitments and constraints. Both partners need to obtain buy-in at different levels, and constant communication between the partners is essential. A designated manager from industry and one from the university need to be appointed, as the 'go-to' people for the two partners. At the first project briefing session, the industry partner explains a Non-Disclosure Agreement (NDA) whereby students agree not to disclose business information with external parties, and each student is required to sign this before the project brief takes place. The Protection of Personal Information Act (applicable in South Africa) is also discussed, and students provide written confirmation that their personal particulars (e.g., name, surname, cellular phone number and email address) can be provided to the industry partner, especially if it should be required for recruitment purposes.

Once administrative issues are dealt with, the industry partner briefs students on three possible projects which they will complete as a group, with each student selecting one project in which they would like to participate. The lecturer is responsible for dividing students into equal groups and needs to ensure that an equal number of groups are allocated to each project. It would not be fair to project 1, as an example, if only two groups are allocated to this project, but six groups are allocated to project 2. Competition should be equal; it is much easier to 'win' a project if only two groups 'compete'. As far as possible it should be 'fair game' for everyone participating, the students as well as the industry participants. In this particular scenario, equal groups are proposed, to make it fair. A group of four members will have to work harder than a group of six members, and it is easier for individuals to get lost or hide in groups that are bigger than six members.

It is recommended that where possible, four groups participate per project, as experience has shown that this is manageable from a time management and project management perspective for a group of 60 students. The industry partner then presents an overview of the company, what it stands for, its culture, its work ethic, the history of the WIL project, how collaboration is shared, and how each project is expected to unfold, with specific requirements. Current market information, product information and sensitive 'real project' issues are shared, and it is reiterated that these details cannot be shared via any type of social media or informal conversation with friends. Students working on the project and the industry partner's sponsors and colleagues are the only partners' privy to the project specifications. The industry partner also introduces the main sponsors who are engaged with the brand/project internally.

The previous year's graduates who received an internship with the company are invited to assist with the project and mentor and coach current students. A group leader is appointed by each group, and after the general briefing session, the project groups break away and talk to the industry partner's sponsors and alumni graduates. Questions are asked, deadlines are agreed on and methods of communication are shared. Literature supports this step, stressing that collaboration between the university and the industry partner is crucial (Khuong, 2016; Etzkowitz & Ranga, 2015) as this working relationship provides lucrative benefits to all parties involved including student, educator and the business partner (Govender & Wait, 2017; Ferns, Russell & Kay, 2016;). Involvement from the industry partner is reiterated, delivering good guidelines, expectations and a well-written brief (Henderson & Trede, 2017).

Step 3: WIL presentation and assessment

The project briefing should be conducted as the first lecture or briefing session for the particular module, and the final presentation to the industry partner's directors and senior managers should take place at the end of the same semester/year. The lecturer meets with the students during the allocating lecturing slots, for three-and-a-half hours per session, before the final presentation. At these sessions certain themes are lectured, theories are explained, and all theories are linked to the different projects where applicable. Guest speakers are invited to address the latest trends in business thinking and students are encouraged to engage with guest lecturers during these sessions. Class participation is encouraged through a debate, themed around an industry trend and/or challenge. An individual report is submitted initially, in which each student is required to portray a thorough situation analysis, identify the problem, and set the objectives for their project as a 'check point' to ensure that they start at the right place.

Student groups present their project ideas to the industry panel, where they have the opportunity to engage with the panel and critically and constructively address questions and comments. They are then steered in the right direction with recommendations for improvement. The groups next present their amended concepts to a Creative Agency, together with the industry partner's sponsors and industry interns. The Creative Agency develops one image from input and discussions at this meeting and the WIL students use this image in their final presentations. The lecturer, together with other academic colleagues, attends an event where each student group presents their proposals to industry and the Creative Agency to gauge progress, determine if students are on the right track and intervene if there are gaps.

At these presentations, student groups are awarded a mark by all panel members present. An average of these marks counts towards their academic semester mark. The rubric for marking is developed with the industry partner beforehand and is available to students before the presentation. The same procedure is followed with the final presentation at the end of the semester/year. Once again, a rubric is available to the students, and they receive the average mark of the industry attendees present. At the final presentation, student groups present for 30-45 minutes and receive feedback. Each group answers specific questions regarding their concept, proposed strategy and implementation suggestions. They are required to present a 'fictional budget', and show how they would implement it and how they would measure the success of their campaign. In the final part of the presentation, each group reflects on the journey of the industry project and highlights the project's strengths as well as challenges.

Students and groups who impress industry partners most are targeted for interviews for possible internships and/or employment positions. The winning group from each project is announced at various educator and industry year-end functions, where each group member is presented with a reasonable cash voucher. Leon-Garcia (2018) and Farr-Wharton et al., (2018) support the notion of lecturers preparing students for the real world by providing opportunities to engage in teams as well as with the lecturer. Student and lecturer communication, engagement, and class participation are crucial in preparing students to achieve the WIL industry-project's goals (Hunt & Madhavaram, 2014; Farr-Wharton et al., 2018).

RECOMMENDATIONS

Recommendations to Step 1: Determine Industry needs

Recommendation 1: Determine who are the 'behind the scenes' stakeholders

As mentioned in step 1, it is imperative to meet each year with the entire industry project team involved before the new projects are devised and approved. The benefits of evaluating the previous year's performance are to (i) gain an understanding about the industry participants perceptions and experiences of what can be improved; (ii) gain knowledge of new technologies that need to be implemented; and (iii) agree on expectations and outcomes. Currently proposed during step 1 of the postgraduate WIL Model, the industry's needs are evaluated and determined, but from the industry advisory board, the alumni, the current students and the Council of Higher Education. However, to improve this current postgraduate WIL-model, it is proposed that key stakeholders that are 'behind the scenes' from industry are interviewed to gain an understanding of what worked and did not work. Although industry participants are approached every year to evaluate the previous year's project and plan for the coming year's project, there are stakeholders 'behind the scenes' that are not approached. For example, the marketing director and/or divisional manager who attended the final presentations, but who are not formally part of the university-industry project or the Industry Advisory Board, might have valuable insights. It is not necessary for these 'behind the scenes' stakeholders to meet, but research strategies can be implemented to gain their input too.

Recommendation 2: Obtain input from lecturers from other disciplines who are involved in WIL projects

To incorporate the proposed recommendation by students to guard against a 'silo' approach, this can be overcome by inviting other lecturers from other disciplines to provide input into this particular WIL model. A lecturer from, for example, Applied Information Services, who is still in the business domain, can share his or her experiences and 'know how' to improve the current postgraduate WIL model.

Recommendation 3: Involve all the lecturers on the course to evaluate the WIL model

To incorporate feedback from students who commented:

Remove repetitive messages or course information (other modules in programme,

the various lecturers on the programme need to talk to each other to ensure repetitiveness is avoided. Constructive criticism on the entire course will influence the perception of the WIL project that builds on all the modules presented in the course. Repetitive information can be removed if transparency is adhered to. Another suggestion from students were:

To address the issue of a variety of experiences on the course.

Again, if there is transparency about what each lecturer is doing in each of the modules, variety can be introduced.

Recommendations to Step 2: Implement WIL project

Recommendation 4: Agree and negotiate expectations between the student and the lecturer

Although the WIL-model for postgraduate students is refined after each year, it is evident from some students' responses that their expectations were not met. One student wrote

I never plan to work in FMCG, so I wasn't sure why I had to participate in this project.

Another student wrote:

I am an entrepreneur and will start my own business and I didn't see how this project align to my future business plans.

Although there were only four negative responses on the project itself, it is proposed that the university, specifically the lecturer in charge should communicate and negotiate expectations and projected outcomes before the project commences. Furthermore, it will be good to hear what students' expectations are, before they start with the project and to agree together: students, industry and university on guidelines and ground rules before the project starts. To address the need to have exposure to more than one industry, all the lecturers on the course have to meet during step 1 as explained above in recommendation 3.

Recommendation 5: Facilitate strategic thinking

Literature states the need for strategic thinking skills (Vega, 2018; Haycock et al.,2012; Seyed et al., 2015; Moon, 2013), and propose that it is easier to gain these skills when students are involved in practical, hands-on projects (Meza Rios et al., 2018). In straddling the business theory and practical business challenges, opportunities arise for creative problem solving, together with novel ideas and innovative solutions that facilitate strategic thinking. Undergraduate numbers hinder the practicality of hands-on, work-related industry projects, and thus the increased need for postgraduate WIL projects is highlighted where classes are smaller with less students that makes such a project more manageable. It is recommended that students are provided with the opportunity to incorporate all their knowledge gained from undergraduate studies as well as on the rest of the postgraduate course. The only way to do this, is for the lecturer to be involved in undergraduate programmes too, to understand what is offered and how the postgraduate scaffolds on the undergraduate foundation.

Furthermore, to address students' feedback that financial skills are not fully addressed with this particular postgraduate WIL model, it is recommended that experts are brought in, from other disciplines at the particular university, or from other parts of industry to provide students with this hand-on practical financial expertise to better their strategic thinking skills.

Recommendations to Step 3: WIL assessment and presentation

Recommendation 6: Assess industrystakeholders' benefits received after final presentations

It is not possible to increase benefits if the expectations and needs are not known. It should not be assumed that what the university sees as a benefit, is what the industry participants or the students see as benefits. The only way to determine needs, is to ask what they are and to monitor various' parties' experiences throughout the entire process. It is therefore proposed that the university WIL project leader, identify stages during the WIL process to obtain feedback. Currently the postgraduate WIL project proposes that stakeholders meet before and after the project, however expectations can be better managed if it is monitored throughout the process. This will provide all the participants the opportunity to adapt during the process to provide a better experience for all participants involved.

CONCLUSIONS

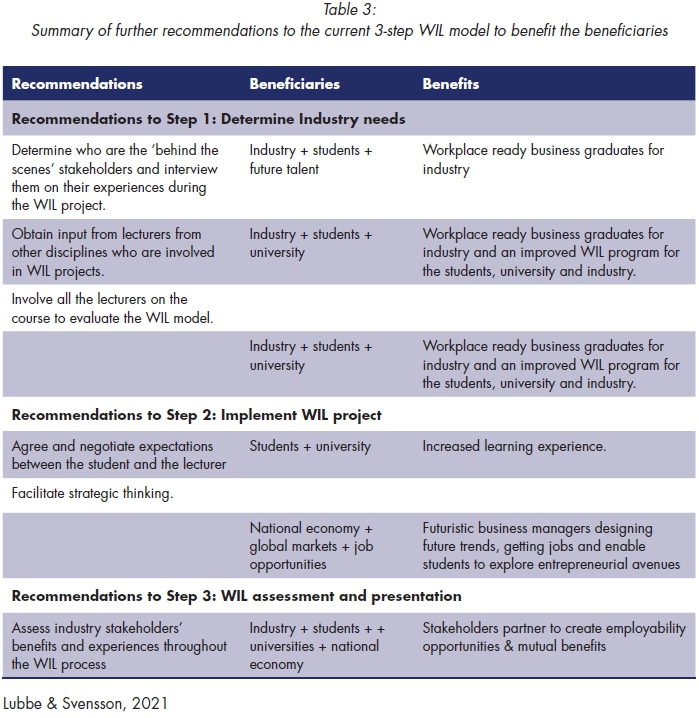

This study critically evaluated an existing WIL model for postgraduate business students. The two strengths of this study are firstly, the promotion of input and feedback from all stakeholders involved in the postgraduate WIL project, and secondly this proposed WIL model can be a good starting point for universities or industry considering a future postgraduate WIL project for business students. Although feedback from stakeholders have been obtained to refine and improve the model over the years, the authors recognise that there are yet more improvements to implement: (i) determine who are the 'behind the scenes' stakeholders, (ii) obtain feedback from lecturers from other disciplines, (iii) involve all the lecturers on the course to evaluate the WIL model, (iv) agree and negotiate expectations between the student and the lecturer, (v) facilitate strategic thinking, and (vi) assess industry stakeholders' benefits and experiences throughout the WIL process.

The challenges for implementing future postgraduate WIL projects are the increasing postgraduate student numbers. Pressure from management to increase postgraduate student numbers put strain on lecturers to manage this increasing classes sizes. Furthermore, it becomes harder to manage WIL projects when there are many students involved. Industry also faces challenges, with financial pressures to make a profit with increased economic pressures leave little time to involve industry participants in university related WIL projects, when they could be billing their hours. However, in this particular project the industry partner recognises the privilege to be involved in shaping future business leaders and to be first to spot talent.

This study presents the value for postgraduate business students and the benefits to industry of partnering in WIL projects for a win-win situation. It presents a working WIL model for postgraduate business students, which is aligned with trends documented in literature. Step 1 of the model determines industry needs. Step 2, enables students to experience WIL as a practical activity and Step 3 allows students to present and showcase their unique talents and skills to potential employers. It is this phase that has the potential to increase job opportunities for graduating business students in the immediate short term. In the long term, all students experiencing the WIL model stand a chance of becoming absorbed into the workforce, locally, nationally or internationally.

REFERENCES

Agnew, D., Pill, S. & Orrell, J. (2017) Applying a conceptual model in sport sector work-integrated learning contexts. Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education 18(3) pp.185-198. [ Links ]

Alharahsheh, H.H. & Pius, A. (2021) Exploration of Employability Skills in Business Management Studies Within Higher Education Levels: Systematic Literature Review. Research Anthology on Business and Technical Education in the Information Era, pp.1147-1164.

Asproth, V., Amcoff Nyström, C., Olsson, H. & Oberg, L. (2011) Team syntegrity in a triple loop learning model for course development. Issues in Informing Science & Information Technology 8 pp.1-11. [ Links ]

Atkinson, J.K., Coleman, P.D. and Blankenship, R.J. (2014) Alumni attitudes on technology offered in their undergraduate degree program. Databases 52(3) pp.63-793. [ Links ]

Baker, H. (2015) What makes a great PR or marketing graduate? The B2B PR Blogg, http://b2bprblog.com/blog/2015/05/what-makes-a-great-pr-or-marketing-graduate

Barwise, P. & Meehan, S. (2011) Customer insights that matter. Journal of Advertising Research 51(2) pp.342-344. [ Links ]

BizTrends 2017. (2017) #BizTrends2017: SA's graduate labour market - trends and issues. Bizzcommunity http://www.bizcommunity.com/Article/196/722/157320.html (Accessed 15 November 2019).

Bradford, R. (2018) Strategic Thinking: 11 Critical skills needed. Center for Simplified Strategic Thinking, Inc. https://www.cssp.com/CD0808b/CriticalStrategicThinkingSkills/ (Accessed 17 January 2020).

Branson, R. (2017) Richard Branson's advice for creating great marketing. Virgin.com. https://www.virgin.com/entrepreneur/richard-bransons-advice-creating-great-marketing (Accessed 15 November 2019).

Campbell, M., Stewart, V. & Karim, A. (2018) Beyond employability: Conceptualising WIL in postgraduate education. Creating connections, building futures: Proceedings of the 2018 Australian Collaborative Education Network (ACEN) 2018 National Conference. Australian Collaborative Education Network (ACEN) Limited, Australia, pp.19-23.

Carucci, R. (2018) Three ways to be sure you're a strategic thinker. Forbes https://www.forbes.com/sites/roncarucci/2018/04/09/three-ways-to-be-sure-youre-a-strategic-thinker/#2034f4764218 (Accessed 10 October 2019).

Chuenpraphanusorn, T., Snguanyat, O., Boonchart, J., Chombuathong, S. & Moonlapat, K. (2017) The development of work-integrated learning model in business service field for Rajabhat University, Thailand. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 8(1) pp. 216-226. [ Links ]

Clausen, H.B. & Andersson, V. (2019) Problem-based learning, education and employability: a case study with master's students from Aalborg University, Denmark Journal of teaching in travel & tourism 19(2) pp.126-139. doi.org/10.1080/15313220.2018.1522290 [ Links ]

Crebert, G., Bates, M., Bell, B., Patrick, C-J. & Cragnolini, V. (2004) Developing generic skills at university, during work placement and in employment: graduates' perceptions. Higher Education Research & Development 23(2) pp.147-165. [ Links ]

Donald, W., Baruch, Y. & Ashleigh, M. (2017) Boundaryless and Protean Career Orientation: A multitude of pathways to graduate employability. Graduate Employability in Context. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Etzkowitz, H. & Ranga, M. (2015) Triple helix systems: an analytical framework for innovation policy and practice in the knowledge society. Entrepreneurship and Knowledge Exchange. Routledge.

Farr-Wharton, B., Charles, M.B., Keast, R., Woolcott, G. & Chamberlain, D. (2018) Why lecturers still matter: The impact of lecturer-student exchange on student engagement and intention to leave university prematurely. Higher Education 75(1) pp.167-185. [ Links ]

Ferreira, L. & Barbosa, M. (2019) PBL method in the formative process in postgraduate courses: An evaluation from students' perception. International journal for innovation education and research 7(12) pp.333-347. [ Links ]

Ferns, S., Russell, L. & Kay, J. (2016) Enhancing industry engagement with work-integrated learning: Capacity building for industry partners. Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education 17(4) pp.363-375. [ Links ]

Fitzgerald, B.K., Barkanic, S., Cardenas-Navia, I., Elzey, K., Hughes, D. & Troyan, D. (2015) The BHEF National Higher Education and Workforce Initiative: A model for pathways to baccalaureate attainment and high-skill careers in emerging fields, Part 2. Industry and Higher Education 29(5) pp. 419-427. [ Links ]

Fodness, D. (2007) Strategic thinking in marketing: implications for curriculum content and design. AMA Winter Educators' Conference Proceedings pp.341-342.

Freudenberg, B., Brimble, M. & Vyvyan, V. (2010) The penny drops: Can work integrated learning improve students' learning? E-Journal of Business Education & Scholarship of Teaching 4(1) pp.42-61. [ Links ]

Gannon, J., Rodrigo, Z. & Santomá, R. (2016) Learning to work interculturally and virtually: Developing postgraduate hospitality management students across international HE institutions. International Journal of Management Education (Elsevier Science) 14(1) pp.18-27, doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2016.01.002 [ Links ]

Govender, C.M. & Taylor, S. (2015) A work integrated learning partnership model for higher education graduates to gain employment South African Review of Sociology 46(2) pp.43-59. [ Links ]

Govender, C.M. & Wait, M. (2017) Managing work integrated learning strengths, opportunities and risks in the emerging South African environment. GABTA 19th Annual Conference - Vienna, Austria 11-15 July, pp.223-232.

Grecu, V. & Denes, C. (2017) Benefits of entrepreneurship education and training for engineering students. In the 8th International conference on Manufacturing Science and Education - MSE 2017. MATEC Web of Conferences 121 No.12007 pp.1-7. EDP Sciences

Greenacre, L., Freeman, L., Jaskari, M. & Cadwallader, S. (2017) Editors' Corner: The 'Work-Ready' Marketing Graduate. Journal of Marketing Education 39(2) pp.67-68. [ Links ]

Gurchiek, K. (2010) Strategic thinking, communicating are top HR competencies HR Magazine 55(5) p.18. [ Links ]

Hall, J. (2018) 5 Marketing Trends to Pay Attention to in 2019. Forbes https://www.forbes.com/sites/johnhall/2018/06/17/5-marketing-trends-to-pay-attention-to-in-2019/#739ad1c560f7 (Accessed 15 November 2019).

Hamilton, M., Carbone, A., Gonsalvez, C. & Jollands, M. (2015) Breakfast with ICT Employers: What do they want to see in our graduates. Proceedings of the 17th Australasian Computing Education Conference (ACE 2015) 27(1) p.30.

Haycock, K., Cheadle, A. & Bluestone, K.S. (2012) Strategic thinking: Lessons for leadership from the literature. Library Leadership and Management 26(3-4) p.10. [ Links ]

Hemmert, M., Bstieler, L. & Okamuro, H. (2014) Bridging the cultural divide: Trust formation in university-industry research collaborations in the US, Japan, and South Korea. Technovation 34(10) pp.605-616. [ Links ]

Henderson, A. & Trede, F. (2017) Strengthening attainment of student learning outcomes during work-integrated learning: A collaborative governance framework across academia, industry and students. Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education 18(1) pp.73-80. [ Links ]

HRDC. (2017) The importance of education-industry partnerships. Human Resource Development Council South Africa, http://hrdcsa.org.za/the-importance-of-education-industry-partnerships/ (Accessed 7 March 2019).

Hunt, S.D. & Madhavaram, S. (2014) Teaching dynamic competition in marketing. Atlantic Marketing Journal 3(2) pp.80-93. [ Links ]

Ibrahim, H. & Jaaffar, A. (2017) Investigating post-work integrated learning (WIL) effects on motivation for learning: an empirical evidence from Malaysian Public Universities. International Journal of Business and Society 18(1) pp.17-32. [ Links ]

Ince, M. (2011) How are universities responding to demand for degrees that better prepare students for future employment? Top Universities https://www.topuniversities.com/student-info/careers-advice/how-can-universities-prepare-students-work/ (Accessed March 2019).

Iyengar, R.V. (2015) MBA: The Soft and Hard Skills That Matter. IUP Journal of Soft Skills 9(1) pp.7-14. [ Links ]

IOA. (2017) How can graduates better their chances of employment in the South African job market? On Africa (IOA) https://www.inonafrica.com/2017/07/20/can-graduates-better-chances-employment-south-african-job-market-2/ (Accessed March 2019).

Jackson, D. (2015) Employability skill development in work-integrated learning: Barriers and best practice Studies in Higher Education 40(2) pp.350-367. [ Links ]

Jacques, C. (2014) Credit quandaries: How career and technical education teachers can teach courses that include academic credit. Center on Great Teachers and Leaders at American Institutes for Research https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED555679.pdf (A ccessed 10 October 2019).

Johnson, L., Becker, S.A., Cummins, M., Estrada, V., Freeman, A. & Hall, C. (2016) NMC horizon report: 2016 Higher Education Edition. The New Media Consortium, pp.1-50.

Johnson, P. (2015) Can a business survive without marketing? LinkedIn, https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/can-business-survive-without-marketing-poppy-johnson/ (Accessed 17 January 2020).

Kalafatis, S. & Ledden, L. (2013) Carry-over effects in perceptions of educational value Studies in Higher Education 38 pp.1540-1561. [ Links ]

Karim, A., Campbell, M., Hasan, M. (2020) A new method of integrating project-based and work integrated learning in a postgraduate engineering study. The Curriculum Journal 31(1) pp.157-173, doi: 10.1080/09585176.2019.1659839 [ Links ]

Keegan, B.P. (2017) The value of strategic thinking. Forbes https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbescoachescouncil/2017/04/26/the-value-of-strategic-thinking/#371b6153430b (Accessed 17 January 2020).

Khuong, C.H. (2016) Work-integrated learning process in tourism training programs in Vietnam: Voices of education and industry. Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education 17(2) pp.149-161. [ Links ]

Krell, J., Todd, A. & Dolecki, P.K. (2019) Bridging the Gap Between Theory and Practice in Neurofeedback Training for Attention. Mind, Brain, and Education 13 pp.246-260. doi:10.1111/mbe.12220 [ Links ]

La Marca, D. (2017) Why IoT (Internet of Things) and Industry 4.0 need professional marketing. Media Buzz, https://www.mediabuzz.com.sg/research-analysis-and-trends-july2017/why-iot-and-industry-4-0-need-professional-marketing (Accessed 17 January 2020).

Leon-Garcia, F. (2018) Preparing students for a rapidly-changing world. University World News. 23 March, https://www.universityworldnews.com/ (Accessed January 2019).

Masole, L. & Van Dyk, G. (2016) Factors influencing work readiness of graduates: An exploratory study. Journal of Psychology in Africa 26(1) pp.70-73. [ Links ]

McArthur, E., Kubacki, K., Pang, B. & Alcaraz, C. (2017) The employers' view of 'work-ready' graduates: A study of advertisements for marketing jobs in Australia. Journal of Marketing Education 39(2) pp.82-93. [ Links ]

Melaia, S., Abratt, R. & Bick, G. (2008) Competencies of marketing managers in South Africa. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 16(3) pp.233-246. [ Links ]

Meza Rios, M., Herremans, I., Wallace, J., Althouse, N., Lansdale, D. & Preusser, M. (2018) Strengthening sustainability leadership competencies through university internships. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 19(4) pp.739-755. [ Links ]

Moon, B. (2013) Antecedents and outcomes of strategic thinking. Journal of Business Research 66(10) pp.1698-1708. [ Links ]

Mustata, I.C., Alexe, C.G. & Alexe, C.M. (2017) Developing competencies with the general management ii business simulation game. International Journal of Simulation Modelling (IJSIMM) 16(3) pp.412-421, doi:10.2507/IJSIMM16(3)4.383 [ Links ]

Mutalemwa, D., Utouh, H. & Msuya, N. (2020) Soft Skills as a Problem and a Purpose for Tanzanian Industry: Views of Graduates. Economic Insights - Trends & Challenges 4 pp.45-64. [ Links ]

Ohei. K.N. & Brink, R. (2019) Investigating the prevailing issues surrounding ICT graduates' employability in South Africa: A case study of a South African University. The Journal of Independent Teaching and Learning 14(2) pp.29-42. [ Links ]

Okoti, D. (2018) It takes more than a degree to beat unemployment. Daily Nation https://www.nation.co.ke/lifestyle/mynetwork/It-takes-more-than-a-degree-to-beat-unemployment/3141096-4588296-ff7uv4/index.html (Accessed 10 October 2019).

Papakonstantinou, T., Charlton-Robb, K., Reina, R.D. & Rayner, G. (2013) Providing research-focused work-integrated learning for high achieving science undergraduates. Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education 14(2) pp.59-73. [ Links ]

Pate, D.L. (2020) The skills companies need most in 2020 - and how to learn them. www.googlescholar.com (Accessed 16 March 2020).

Prikshat, V., Kumar, S. & Nankervis, A. (2019) Work-Readiness Integrated Competence Model: Conceptualisation and Scale Development. Education & Training 61(5) pp.568-589. [ Links ]

Prior, S.J., Van Dam, P., Phoebe, E.J., Griffin, N.S., Reeves, L.K., Bronwyn, P., Giles, A. & Peterson, G.M. (2021) The healthcare redesign student experience: qualitative and quantitative insights of postgraduate work-integrated learning. Higher Education Research & Development doi:10.1080/07294360.2020.1867515

Rackova, K. (2015) Towards Selected Interpersonal Skills in Management. Social & Economic Revue 13(4) pp.68-70. [ Links ]

Reinhard, K. & Pogrzeba, A. (2016) Comparative cooperative education: Evaluating Thai Models on work-integrated learning, using the German Duale Hochschule Baden-Wuerttemberg Model as a benchmark. Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education 17(3) pp 227-247. [ Links ]

Saeed, K. (2015) Gaps in marketing competencies between employers' requirements and graduates' marketing skills. Pakistan Business Review 17(1) pp.125-146. [ Links ]

Schlee, R.P. & Karns, G.L. (2017) Job requirements for marketing graduates: are there differences in the knowledge, skills, and personal attributes needed for different salary levels? Journal of Marketing Education 39(2) pp.69-81. [ Links ]

Seyed Kalali, N., Momeni, M. & Heydari, E. (2015) Key elements of thinking strategically. International Journal of Management, Accounting and Economics 2(8) pp.801-809. [ Links ]

Solnet, D., Kralj, A., Moncarz, E. & Kay, C. (2010) Formal education effectiveness and relevance: Lodging Manager perceptions. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Education 22(4) pp.15-24. [ Links ]

StastSA. (2020) Vulnerability of youth in the South African labour market. StatsSA. June 24, http://www.statssa.gov.za/

Vaaland, T.I. & Ishengoma, E. (2016) University-industry linkages in developing countries: perceived effect on innovation Education + Training 58(9) pp.1014-1040. [ Links ]

Valencia-Forrester, F. (2019) Internships and the PhD: Is this the future direction of work-integrated learning in Australia? International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning 20(4) pp.389-400. [ Links ]

Vande Wiele, P., Morris, D., Ermine, J.L. (2017) Project based learning for professional identity: a case study of collaborative industry projects in marketing. Independent Journal of Teaching and Learning 12(2) pp.44-63 [ Links ]

Van Scheers, L. & Makhitha, K.M. (2016) Are small and medium enterprises (SMEs) planning for strategic marketing in South Africa? Foundations of Management 8(1) pp.243-250. [ Links ]

Vega, J. (2018) Strategic Thinking. Stratex Solutions http://www.stratex.solutions/strategic-thinking/ (Accessed 28 January 2019).

Whitler, K.A. (2018) The 2018 summer reading list for marketers. Forbes https://www.forbes.com/sites/kimberlywhitler/2018/06/03/the-2018-summer-reading-list-for-marketers/#7af425884282 (Accessed 17 January 2020).

Wiedmer, T. (2015) Generations do differ: Best practices in leading traditionalists, boomers, and generations X, Y, and Z. Delta Kappa Gamma Bulletin 82(1) p.51. [ Links ]

Zakharchenko, Y. (2017) Professional training of marketing specialists: Foreign experience. Comparative Professional Pedagogy 7(2) pp.51-55. [ Links ]

1 Date of submission 24 June 2020; Date of review outcome: 11 February 2021; Date of acceptance 4 June 2021

2 Thank you to Cookie Govender from the University of Johannesburg, who assisted with the article's structure.

3 ORCID: 0000-0002-7399-2886

4 ORCID: 0000-0002-4857-9408