Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

The Independent Journal of Teaching and Learning

versión On-line ISSN 2519-5670

IJTL vol.16 no.2 Sandton 2021

ARTICLES

School climate: Perceptions of teachers and principals

Leentjie van JaarsveldI; Kobus MentzII

INorth-West University, South Africa

IINorth-West University, South Africa

ABSTRACT

School climate is experienced differently by various stakeholders at a school; it is also affected by different perceptions, behaviours and social identities. This research set out to contribute to the knowledge of the perceptions of teachers and principals about the organisational climate of their schools. A quantitative study was conducted in one of the provinces in South Africa. The Organisational Climate Description Questionnaire - Rutgers Secondary (OCDQ-RS) was distributed among teachers and principals at 72 public secondary schools in KwaZulu-Natal. A range of statistical analyses was used to analyse the data. Open-ended questions allowed teachers and principals to express their perceptions regarding the factors that played a positive or a negative role in their relationships. The open-ended questions indicated that the perceptions of teachers and principals with regard to the climate in their school differed. Nevertheless, there was some agreement between the teachers and principals regarding particular factors that have an impact on the school climate, such as poor human relations, disrespect, poor work ethics and competitiveness among teachers. The results showed that, although the perceptions of teachers and principals differed, there was no clear evidence that these differences in perceptions had any direct impact on the school climate.

Keywords: school climate, perceptions, attribution theory, social identity, communication, principals, teachers

INTRODUCTION

The circumstances in which teachers have to teach at schools in South Africa are difficult (Cornelissen, 2016; Maddock & Maroun, 2018; Segalo & Rambuda, 2018). Various reports of attacks on teachers have appeared in newspapers over the past few years (for example, News24, 2018; Daily Maverick, 2019; Mail & Guardian, 2019). Apart from the violence in schools, teachers often question the behaviour of the principal. It is the duty of school principals to create an environment that is conducive to teaching and learning. However, perceptions regarding the necessary support for teachers often differ, which results in a questionable perception of school climate.

The term 'social perception' refers to how an individual 'sees' other people and how other people see the individual. Individuals perceive others in ways that reflect their own attitudes and beliefs (Pickens, 2005; Grèzes & De Gelder, 2009; Finne & Svartdal, 2017; Krueger, 2018). The principal plays an important role in achieving the goals of the school. Principals have day-to-day interaction with the teachers as part of a vision and support (Cohen, 2015). The roles of teachers and principals influence their perceptions of the responsibilities of both. Principals regard themselves as responsible for the entire school system and try to create transparency in an effort to exert a positive influence on teachers (Newman, 2014; Klieger, 2016). This transparency does not apply everywhere, which might be why teachers question the behaviour of their principals (Hill, 2013). Teachers also believe that principals can affect learner achievement (Hardman, 2011). The main research question in this article is: To what extent do the perceptions of principals with regard to school climate differ from those of teachers?

The rest of this article is structured as follows. First, the key concepts that guide this study are explained, followed by a description of the theoretical lens that is used to frame this investigation. Thereafter, the authors provide an in-depth explanation of the empirical methods utilised in the study, followed by a discussion of the results. Then, the limitations of the study are discussed, after which the article concludes.

KEY CONCEPTS THAT FOREGROUND THIS INVESTIGATION

Perceptions

Humans perceive data, but it is not known precisely how they do it. Visualisations present data that are then perceived, but how these visualisations are perceived is unknown. For this reason, whether or not our visual representations are interpreted differently by different viewers is not known. In addition, whether or not the data presented are understood is also unknown. There are many definitions of and theories about perception. Most define perception as the process of recognising (being aware of), organising (gathering and storing) and interpreting (binding to knowledge) sensory information.

Johns (2008) claims that perception is the procedure of understanding a message in order to understand the environment. Perceptions help to make meaning of what our senses experience and observe. The focus is on interpreting. People frequently base their actions on the interpretation of reality that their perceptual system provides, rather than on reality itself (Johns, 2008). The perception that members in the organisation have plays an important role when collaboration is involved. Perception consists of three components: (i) a perceiver (e.g., teachers or a principal); (ii) a target (e.g., a school principal or teachers); and (iii) a context (e.g., a school) in which the perception is happening. The perception that an individual has about a target (that is, another human being, e.g., the principal or a peer teacher) is influenced by these three components (Johns, 2008).

The perceiver's understanding, needs and feelings can influence their impression of a target. Past encounters lead the perceiver to create desires, and these desires influence current discernment. Unconsciously, the needs that we have are influenced by our perceptions. Furthermore, feelings such as antagonism, pleasure or anxiety can influence one's perceptions. Johns's statement is in line with Tzeni, loannis, Athanasios and Amalia's (2019) view that teachers' perceptions are different, depending on, for example, their demographic characteristics. Taking this clarification into account, it is obvious that teachers can, for example, change their perception of the school principal as their experiences, motivation and emotional state change. The same could be applicable to the principal.

As far as the target is concerned, perception includes translation and the expansion of importance to the target. It can be said that more information about the target will provide a better perspective of the target. It is important that principals maintain a good relationship with learners, teachers and parents, as it will affect the learners', teachers' and parents' perceptions of the principal. It is important for school principals to know how they are perceived by other people. Therefore, school principals must be transparent (Kadi & Beytekin, 2017). Teachers and principals may change their perceptions regarding one another if they receive more information about each other. However, this is not always the case. Teachers and principals may work together for many years and still have particular perceptions of one another (Johns, 2008).

Studies have shown that differences in perceptions are a common phenomenon. Klieger (2016) postulates that when goals are discussed, teachers and principals often misunderstand one another. The main problem seems to be the lack of what is perceived as 'ours'. In this regard, transparency is of the essence. Clear descriptions of what exactly is meant by reaching particular goals are essential. Ifat and Eyal (2017) focus on assessments, especially the principals' involvement in the assessment process. In another study, Swanepoel (2008: 50) reveals that 'teachers and principals have negative perceptions of each other when it concerns teachers' involvement in responsibility-sharing'. Misunderstandings between teachers and principals often result in a negative climate (Bellibas & Liu, 2016; Kor & Opare, 2017; Pratami, Harapan & Arafat, 2018).

Organisational (School) Climate

Organisational (school) climate can be defined as

a measurable quality, which is identified depending upon the common perceptions of people living and working together in a specific place and affects the behaviors of individuals of the working environment (Hoy & Miskel, 2008: 185).

In line with this definition, Cohen et al. (2009: 182) postulate that school climate is a multidimensional construct that refers to the

quality and character of school life [...] based on patterns of people's experiences of school life and reflects norms, goals, values, interpersonal relationships, teaching and learning practices, and organizational structures.

In yet another explanation of school climate, Hoy and Miskel (2008) focus on the uniqueness of climate in schools. In this regard, they argue that school climate is a combination of inner appearances that distinguishes one school from another. School atmosphere is a wide idea that incorporates the impression of the educators with respect to the workplace, the authority of the school and the community. Zehetmeier et al. (2015) agree with Hoy and Miskel and view school climate as a particular 'atmosphere' created in the school. From another point of view, Barkley (2013) states that school climate is synonymous with an environment in which teaching and learning occur and that it is characterised by a set of norms and expectations within the school. Typically, the climate of the school can be said to be the collective experience of stakeholders in the school.

A positive climate refers to the environment in which employer and employee support each other (Cardina & Fegley, 2016). On the other hand, Cohen and Keren (2010) note that school climate is a psychological experience situated in their work situation and environment that teachers are all a part of. Teachers consider the degree of trust and respect with which they are treated as essential for a positive climate. This reinforces the principal-teacher relationship and means that teachers enjoy more freedom to express their opinions (Hendricks, 2011). Malinen and Savolainen (2016) contend that a positive school atmosphere is seen as associated with less stress as well as higher efficacy and employment fulfilment among teachers. It is clear that school climate has an influence when instructional and distributed leadership practices (Bellibas & Liu, 2016), relationships (Browning, 2014), teachers' performance (Pratami et al., 2018) and teacher support (Silva, Amante & Morgado, 2017) are involved.

THE THEORETICAL LENS UTILISED IN THIS STUDY

In this part of the article, the theoretical framework is discussed. Perceptions of people and attribution theory are related to each other.

Attribution theory deals with how the social perceiver uses information to arrive at causal explanations for events. It examines what information is gathered and how it is combined to form a causal judgment (Gailey & Lee, 2005: 338).

Attribution theory addresses how the behaviour of a person can be explained. As Harvey and Martinko (2010) note, the cause explains the behaviour of a person. Heider (1958) makes two distinctions with regard to behaviour, namely (i) whether a behaviour is seen as intentional or unintentional and (ii) whether a behaviour is seen as caused by something about the person (e.g., culture) or by something about the situation. Heider (1958) elaborates on this distinction and refers to internal and external attributions, respectively. The cause of the behaviour can be attributed to internal personality traits. With reference to external attribution, Heider (1958) claims that a particular action can be attributed to an external circumstance. In this regard, Johns (2008) refers to situational attributions - that is, the outer circumstance or condition wherein the targeted individual exists, whether they have command over their own conduct. In light of this discussion on attribution theory, the behaviour of the principal in a given situation plays an important role when it comes to the perceptions of the teachers with regard to the principal.

In view of this investigation regarding principals' and teachers' perceptions of school climate, the authors interrogated three issues pertinent to the research question:

• Are teachers and principals regularly and consistently part of the behaviour that contributes to the school climate?

• I s this behaviour limited to one person, or extended to other people who behave in the same particular way?

• I s the behaviour influenced by one incident, or does it arise from or is a result of other behavioural incidents as well?

The perceiver's interpretation of the target is influenced by their 'answers' or responses to these questions. People do not stand independently of one another. For this reason, people have certain perceptions about one another. In line with this, the perception of 'the self' plays just as important a role. Based on this statement, the choice of social identity theory is important in this study.

As per social identity theory, individuals structure a view of themselves dependent on their qualities and participation in social classifications (Johns, 2008). One's feeling of self is made up of an individual character and a social personality. Our own personality depends on our one-of-a-kind, individual attributes, for example, our interests, capacities and characteristics. Social character depends on our observation that we have a place in different social gatherings. As people, we expect from ourselves, as well as from others, to comprehend the social condition. The perception that an individual has about themselves forms the perception they have about other people in society (Johns, 2008). Islam (2014: 1782) contributes to this argument by suggesting that 'social identity effects are based on protection and enhancement of self-concepts, threat to the self-concept would intuitively be related to the strongest identity effects'. In line with this, Bochatay et al. (2019) argue that, depending on the situation, individuals may identify with different relevant groups based on their position in the social hierarchy in a school. For example, each teacher forms a perception of themselves. Teachers belong to a specific social group (that is, staff members of a school) and form perceptions about the other staff members as well as about the school principal.

Individuals will, in general, see individuals from their own social classification in increasingly positive and favourable ways as individuals who are unique and have a place with different classes. Thus, teachers could perceive principals in a particular way, while they perceive their own colleagues in a different way.

According to Craig (2012), the principal is seen as the person who determines the school climate, whether positive or negative. Therefore, principals need to be aware of both their influence on school climate and the fact that they can improve or weaken the climate. However, teachers and principals categorise themselves according to social groups to make sense of their social environment. Furthermore, teachers and principals behave differently within the social environment (school), and, as a result, their perceptions of one another differ as well. Kliegler (2016) notes that there is a gap between teachers' and principals' perceptions regarding a positive school climate. It is, therefore, evident that school climate is perceived differently by teachers and principals. In addition, Hayes (2013) claims that male principals view their schools as being more positive and inviting than female principals do. Gül§en and Gülenay (2014) declare that principals in an open climate are supportive, listen to teachers and respect teachers' professionalism. They encourage teachers not only to perform but also to act as leaders themselves. As a result, a more open and positive climate is experienced. Gül§en and Gülenay (2014) continue their argument and emphasise that the school principal is the person who determines the climate of the school. In this regard, they postulate that the school principal is responsible for the administrative process, which includes persuading teachers to arrange their work. Pulleyn (2012) supports Gül§en and Gülenay's (2014) view and adds that, through school principals, a climate of collaboration, collegiality, recognition and respect can be created. This creates a climate in which both teaching could succeed and a learning culture could be created by the learners.

It is notable that school principals have a more positive perception of a positive school climate than teachers do (Duff, 2013). Transparency and openness are, therefore, important to create a joint vision of school climate. Hendricks (2011) found that the availability and visibility of the principal contributed to a positive school climate as teachers experienced this as supportive. Furthermore, teachers experience that daily interaction with the principal, colleagues and learners strengthens relationships. This leads to mutual respect, trust and support, which are important in creating and enabling a climate conducive to teaching and learning.

School climate is regularly estimated from the perspective of learners; however, considering educators' observations is essential (Huang et al., 2015). In this regard, Lim and Eo (2014) argue that clear knowledge of the performance of a school, teacher efficacy and support are essential as they are factors that contribute to establishing a positive school climate. Teachers influence school climate by encouraging learners, establishing a supportive environment and authorising school rules (Huang et al., 2015).

Babu and Kumari (2013) concur and believe that school climate contributes to the perceptions of teachers regarding their own potential. The effectiveness and success of teachers relate to a climate in which good relations, collegiality and participation are of interest. This can be achieved when (i) teachers are allowed to be creative, (ii) regular communication and cooperation exist between them, (iii) they are allowed to be flexible, (iv) opportunities for development are created for them, and (v) sufficient resources are available to them (Chang, Chuang & Bennington, 2011). Furthermore, teachers associate school climate with their own morale at the school. When teachers see the school climate as a positive experience, it strengthens their relationships with the principal, learners and even parents (Barkley, 2013).

As explained, attribution theory is about how individuals perceive one another and how they use that information to explain individuals' behaviour. In addition, social interdependence theory focuses on how individuals see themselves within a social hierarchy. These two theories were used to examine the perspectives of teachers regarding their principals and the principals' perspectives of their staff. It is important that the workers in an organisation (a school) understand one another so that they can work together to achieve goals.

EMPIRICAL INVESTIGATION

Purpose

The purpose of the research was to gain more insight into the perceptions of teachers and principals with regard to school climate.

Research Design

The research is embedded in a quantitative approach within a post-positivist paradigm. Numerical measurement and the observation of the behaviour of individuals are the most important features of the post-positivist paradigm. Because post-positivism allows limitation, contextual factors and the use of multiple theories within the interpretation of the research findings, it is an appropriate paradigm for the study, specifically for quantification but also to unite subjectivity and meaning. According to Creswell (2012), knowledge gained through a post-positivist lens is based on the measurement of targeted reality that focuses on the support of and search for valid and reliable evidence with regard to the phenomenon. This approach leads to a measurement of how the perceptions of teachers and principals differ with regard to the climate of a school.

Population and Sample

The population in this study was the secondary schools in KwaZulu-Natal. A systematic random cluster sampling of 98 schools was drawn by means of statistics from the data list, sorted by quintile and region, so that the selected sample was representative with respect to the region. Eighty schools were identified to take part in this study. The 2013 Grade 12 mathematics results of the National Senior Certificate were used to calculate percentages of mathematics achievement per province in order to distinguish between poorly and well-performing schools.

Data Collection

The OCDQ-RS (34-item, 5-point Likert scale) was used to determine the climate of particular schools (Vos, 2010; Martin, 2012; Van Jaarsveld, 2016). The scale used is represented as follows: 0 = Not at all; 1 = Occasionally; 2 = Sometimes; 3 = Quite often; 4 = Often, if not always.

Teachers and principals had the opportunity to give their opinion on the climate of their schools in these questionnaires. Open-ended questions were posed in the questionnaire with regard to positive and negative factors influencing the relationship between the principal and the teachers and among the teachers themselves. Teachers and principals had to indicate their perceptions separately.

Validity, Reliability and Ethical Issues

The OCDQ-RS has been used in numerous international and national studies and has been proven to be a valid and reliable questionnaire (Antonakis, Avolio & Sivasubramaniam, 2003; Hinkin & Schriesheim, 2008; Schriesheim, Wu & Scandura, 2009; Leong & Fischer, 2011; Martin, 2012). The following statistical analysis techniques were used: statistical significance (p-values) and effect size (d-values). The researchers obtained ethical approval from their institution of employment. Permission was also obtained from the Department of Education in KwaZulu-Natal as well as from the principals of the participating schools. The researchers provided the participants with information on the research and the ethical issues of the study (cf. McMillan & Schumacher, 2010; Creswell, 2012; Leedy & Ormrod, 2013). In the written consent letters, the respondents were informed about their privacy, anonymity, integrity and professional qualities. They were also ensured that they could withdraw from the study at any time. Anonymity was ensured in every respect.

Data Analysis

The data collected were analysed by means of different statistical techniques, namely descriptive statistics. Averages for the different subscales were determined as well as the standard deviation, p-value and effect size of differences.

RESULTS

The results of the OCDQ-RS questionnaire are displayed by means of tables and the results of the open-ended questions by means of graphs. The OCDQ-RS, compiled by Hoy and Miskel (2008), was used to determine how the actions of the principal and the teachers mutually influence the climate in the school. Dimensions to determine school climate are as follows: (i) supportive behaviour; (ii) directive behaviour; (iii) engaged behaviour; (vi) frustrated behaviour; and (v) intimate behaviour (Hoy & Miskel, 2008).

Results of the OCDQ-RS Questionnaire

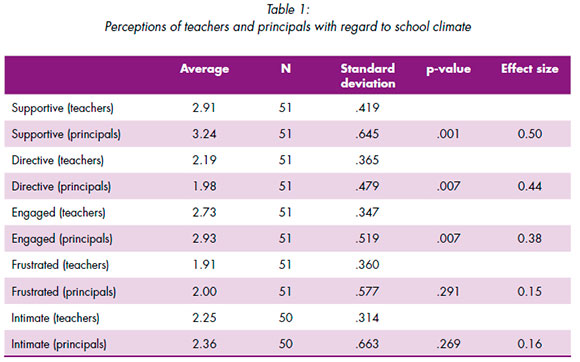

There were statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) between the views of the teachers and views of the principals for various reasons, as discussed below.

Principals' supportive behaviour

The effect size (d = 0.50) indicates a medium difference between teachers' and principals' perceptions with regard to support. According to the average scores, the principals in the study believed that their support was very good (average = 3.24), whereas the teachers did not necessarily agree with them (average = 2.91).

Principals' prescriptive behaviour

The effect size (d = 0.44) indicates a medium difference between teachers' and principals' perceptions about prescriptive behaviour. The average scores made it clear that the teachers thought their principals were prescriptive (average = 2.19), while the principals did not necessarily agree with that (average = 1.98).

Involved behaviour of teachers

The effect size (d = 0.38) indicates a small difference between the teachers and the principals with regard to teachers' behaviour. According to the average scores, the principals were of the opinion that the teachers were involved with one another (average = 2.93), while the teachers did not necessarily agree with that (average = 2.73).

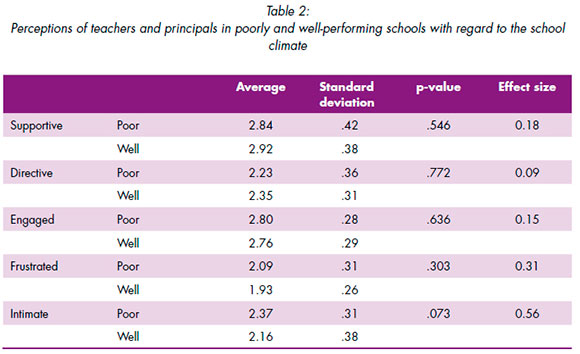

Table 2 presents the perceptions of the teachers and the principals with regard to the school climate in poorly and well-performing schools.

No factor in the organisational climate showed statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) between the poorly and well-performing schools. Nonetheless, it appeared that the relationships between the teachers in the well-performing schools were not that intimate. It can be an indication that these teachers concentrate more on their learners than on associating with one another, and, as a result (d = 0.56), the learners perform better.

Analysis of Open-Ended Questions

Interesting results for the open-ended questions came to the fore. Principals and teachers differ remarkably with regard to influential factors in a positive relationship between teachers and principals. This finding corresponds with the results of the findings set out in Tables 1 and 2. Teachers prioritised communication as the main factor that contributed to a positive relationship between them and their principals. On the other hand, the principals perceived honesty and respect as the main contributing factors with regard to a positive relationship. However, the principals agreed with the teachers that respect was a contributing factor in a positive relationship. It was clear that the perceptions of the teachers and principals played a role in the school climate. Where the teachers and principals understood each other and the behaviour of the principal was explained, a positive school climate prevailed. The opposite was visible when teachers did not understand the principal's actions. In this case, a negative school climate prevailed.

The perception of the teachers was that teamwork and respect were the two main factors that contributed to a positive relationship between them. On the other hand, the principals perceived respect as the main contributing factor to a positive relationship between teachers. Thus, the principals and the teachers agreed that respect and teamwork were the two main contributing factors to a positive relationship between teachers. Respect and teamwork contribute to a positive school climate.

With regard to negative factors influencing the relationship between teachers and principals, it was notable that the principals felt that poor ethical behaviour was the main factor that influenced the relationship between them and teachers. Typically, from the viewpoint of the principals, work has to be done, and, if teachers do not follow ethical practices, it could ruin the relationship between them. However, teachers' perceptions indicated that autocracy was the main factor influencing the relationship between them and the principals. The teachers also perceived poor management as a factor that negatively influenced the relationship between them and the principals, while the principals perceived poor human relations as a factor that influenced the relationship between them negatively.

The results for the negative impact on the relationship between teachers were remarkable. Both the principals and the teachers perceived poor human relations, disrespect, poor ethics and competitiveness in the same way. It was clear that, in this instance, the principals and the teachers agreed on the negative factors influencing the relationship between teachers. From this discussion, it is clear that ethical behaviour, democratic leadership, effective management and human relationships are crucial elements for a conducive school climate.

DISCUSSION OF RESULTS

As envisaged, the results of this study were interpreted through the lens of perceptions, attribution theory and social identity theory. Perceptions are unique to people. Each person experiences situations and behaviour in their own way and forms their own perception regarding another person. In this study, it was clear that the perceptions of the respondents with regard to the school climate differed.

The teachers interpreted the behaviour of the principals in their own way and, therefore, acted according to the interpretation of the behaviour. Because individuals' perceptions differ, each individual will interpret an action differently and act accordingly. The principals indicated that they were supportive of teachers, whereas the teachers disagreed with that. The results of a favourable school climate are strengthened relationships, better interaction and improved performance. These relationships and interactions are established by the behaviour of the principal and the teachers. Robinson (2010) placed emphasis on the importance of support and engagement in her studies in the United States of America. Yet perceptions with regard to principals' support in order to get teachers more involved differed. The participants' indications varied in terms of how supportive the principals and how involved the teachers were. All of the principals indicated that they were supportive of the teachers. In accordance with the principle of attribution theory that explains how the social perceiver uses information to arrive at causal explanations for events, the teachers felt that the principals did not support them. The principals felt that the teachers were engaged, but it seemed as though the teachers did not agree with the principals.

The fact that there was a discrepancy in the principals' and the teachers' perceptions, especially with regard to support and engagement, corresponds with the findings of Osman (2012), who placed emphasis on the mediation and transmission of information and expectations to enhance a positive school climate. It is important for school principals to support teachers in order to ensure effective teaching and learning. By being friendly and encouraging, praising teachers and having empathy for them, a school climate conducive to teaching and learning can be created (Sirisookslip, Ariratana & Ngang, 2015). Although the principals indicated that they were supportive of the teachers, the teachers disagreed. In fact, the teachers indicated that the principals were prescriptive, while the principals disagreed with this perception of the teachers. Gedifew (2014) argues that successful principals are prescriptive and supportive, which results in teachers and management being effective. In the study, the principals and the teachers agreed that a poor work ethic among teachers was one of the negative factors influencing a school climate conducive to teaching and learning. Poor work ethic among teachers could result in ineffective teaching. With regard to the involvement of teachers, the principals' perceptions were that the teachers were involved with one another, but the teachers disagreed with the perceptions of the principals. Robinson (2010) claims that when teachers are involved with and know one another, it contributes to a positive school climate. In this study, it was clear that the teachers disagreed with the statement that they were involved with their colleagues.

When the open-ended questions regarding school climate were taken into consideration, it was again clear that the perceptions of the teachers and the principals in the study differed. With regard to a positive relationship between the principals and the teachers and between the teachers themselves, the results showed a different perspective on what was important with regard to a positive school climate. The teachers' perception was that communication and teamwork were the two main factors contributing to a positive relationship. The principals indicated that support contributed to a positive school climate. In their opinion, honesty and respect contributed to a supportive relationship.

With regard to negative relationships between the principals and the teachers and between the teachers themselves, the principals and the teachers differed in their perspectives on which factors influenced a positive school climate. The teachers' perceptions were that autocracy and poor human relationships could create a negative school climate, while the principals' perceptions were that poor ethics could create a negative school climate. It was notable that the teachers and the principals agreed that poor human relations were the main factor that contributed to a negative school climate.

It is clear that the perceptions of the principals and the teachers differed. As mentioned earlier, attribution theory is concerned with the question of how ordinary people explain human behaviour. The perceptions of both the principals and the teachers should be seen in light of their behaviour: (i) Is the behaviour intentional or unintentional? and (ii) Is the behaviour a result of the person or the situation at hand? If the teachers experienced the behaviour of their principals as not supportive, it simply implied that it was their perception and not necessarily true. It could be possible that the principals did not behave in a supportive manner due to circumstances. Thus, internal and external attributions should be taken into consideration. The behaviour of the principal, therefore, must be monitored over a period to determine whether the behaviour is an internal attribution, for example, the personality of the principal, or an external attribution, for example, the principal's environment. Furthermore, the perceptions of the teachers and principals should be seen in light of the social identity of each individual. Teachers tended to perceive individuals who fall into the same social class as themselves as similar to them. For the teachers, there was a social difference between teachers, administrative personnel and other workers. Therefore, teachers experienced more supportive behaviour from their colleagues than from their principals.

When teachers or principals experience the school climate as one where there is a lack of involvement, membership in different social categories should be taken into account. Thus, staff members might see themselves as a group that is positively involved in school matters, but principals might see themselves as belonging to a different hierarchy and, therefore, experience the involvement of the teachers differently. It is a matter of concern that there is a discrepancy between teachers and principals regarding issues that affect the relationship between them. This discrepancy can be ascribed to the strict hierarchical structure that is found at most schools, where principals are viewed as managers and representatives of the Department of Basic Education. The gap between these two groups should be narrowed in the interest of both. According to attribution theory, individuals use information to explain events. For this reason, perceptions should be aligned to explain particular events. In addition, as social identity theory argues, individuals' personalities should be taken into consideration, and, therefore, individuals' perceptions should be considered.

LIMITATIONS

A mixed-methods research approach, including the perceptions of the learners regarding their school climate, could be of value in further research. A larger sample could have added to the value of the study; that is, more provinces could be investigated to gain a clearer picture of the climate in schools in the country.

CONCLUSION

The study focused on the perceptions of teachers and principals regarding their school climate. As a school consists of various individuals with different beliefs, ideas and perceptions, different behaviours are expected. Within different social identities, it is clear that teachers and principals have their own perceptions of a school climate that is conducive to teaching and learning. Particularly concerning is the finding that principals view themselves as being very supportive, while teachers, in general, do not agree. As indicated above, this can be ascribed to a gap in management, where principals are seen as unapproachable. However, to create a school climate conducive to teaching and learning where teachers and principals agree upon the factors that influence the school climate, open and transparent communication must be maintained. Some schools in South Africa are struggling to maintain a school climate conducive to teaching and learning, which influences the teaching and learning process. In addition, teachers and principals should attempt to align their perspectives and to understand why an individual behaves in a particular way. Further investigation should be conducted into school climate in South Africa. The actions of the principal and the teachers affect school climate. Transparent actions can create a favourable climate within which the principal, teachers and learners can achieve their goals so that the school as a whole performs better. Ways of how to improve school climate should be explored, not only on school level but also by the Department of Basic Education. Teachers, principals, learners, the community and the Department of Basic Education must collaborate to build a positive school climate in South African schools.

REFERENCES

Antonakis, J., Avolio, B.J. & Sivasubramaniam, N. (2003) Context and leadership: an examination of the nine-factor full-range leadership theory using the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire. The Leadership Quarterly 14(3) pp.261-295. [ Links ]

Babu, A. & Kumari, M. (2013) Organizational climate as a predictor of teacher effectiveness. European Academic Research 1(5) pp.553-568. [ Links ]

Barkley, B.P. (2013) Teacher perception of school culture and school climate in the leader in ME schools and non-leader in ME schools. PhD dissertation, University of Southern Mississippi, Hattiesburg, US. [ Links ]

Bellibas, M.S. & Liu, Y. (2016) The effects of principals' perceived instructional and distributed leadership practices on their perceptions of school climate. International Journal of Leadership in Education 21(2) pp.229-244. [ Links ]

Bochatay, N., Bajwa, N.M., Blondon, K., Perron, N.J., Cullati, S. & Nendaz, M.R. (2019) Exploring group boundaries and conflict: a social identity theory perspective. Medical Education 53 pp.799-807. [ Links ]

Brown, M.T. (2018) The differences between principal and teacher perception of professional learning communities in California schools. PhD thesis, Lynchburg, Liberty University, US. [ Links ]

Browning, M. (2014) Self-leadership: Why it matters. International Journal of Business and Social Science 9(2) pp.14-18. [ Links ]

Cardina, C.E. & Fegley, J.M. (2016) Attitudes towards teaching and perceptions of school climate among health education teachers in the United States, 2011-2012. Journal of Health Education Teaching 7(1) pp.1-14. [ Links ]

Chang, C., Chuang, H. & Bennington, L. (2011) Organizational climate for innovation and creative teaching in urban and rural schools. Quality and Quantity 45(4) pp.935-951. [ Links ]

Cohen, E. (2015) Principal leadership styles and teacher and principal attitudes, concerns and competencies regarding inclusion. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 186 pp.758-764. [ Links ]

Cohen, A. & Keren, D. (2010) Does climate matter? An examination of the relationship between organisational climate and OCB among Israeli teachers. The Service Industries Journal 30(2) pp.247-263. [ Links ]

Cohen, J., McCabe, E.M., Michelli, N.M. & Pickeral, T. (2009) School climate: Research, policy, practice, and teacher education. Teachers College Record 111 pp.180-213. [ Links ]

Cornelissen, T.P. (2016) Exploring the resilience of teachers faced with learners' challenging behaviour in the classroom. MEd thesis, University of Stellenbosch, Stellenbosch, South Africa. [ Links ]

Craig, A.V. (2012) A new framework for school climate: Exploring predictive capability of school climate attributes and impact on school performance scores. PhD dissertation, University of Louisiana, Lafayette, US. [ Links ]

Creswell, J.W. (2012) Educational research. Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. Boston: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Daily Maverick. (2019) Violence at school: 'Lack of political will' blamed, among other factors. Simelane, B.C. June 14.

Duff, B.K. (2013) Differences in assessments of organizational school climate between teachers and administrators. PhD dissertation, Liberty University, Lynchburg, US. [ Links ]

Finne, J.N. & Svartdal, F. (2017) Social perception training: Improving social competence by reducing cognitive distortions. International Journal of Emotional Education 9(2) pp.44-58. [ Links ]

Gailey, J. & Lee, M.T. (2005) An integrated model of attribution of responsibility for wrongdoing in organizations. Social Psychology Quarterly 68(4) pp.338-358. [ Links ]

Gedifew, M.T. (2014) Perceptions about instructional leadership: The perspectives of a principal and teachers of Birakat primary school in focus Educational Research and Reviews 9(16) pp.542-550. [ Links ]

Grèzes, J. & De Gelder, B. (2009) Social perception: understanding other people's intentions and emotions through their actions. In T. Striano & V. Reid, V. (Eds.) Social cognition: Development, Neuroscience and Autism. S.l.: Wiley-Blackwell.

Grobler, R. (2018, November 22) Violence and killing at SA schools: These stories shocked us in 2018. News24.

Gülsen, C. & Gülenay, G.B. (2014) The principal and healthy school climate. Social Behavior and Personality 42 pp.93-100. [ Links ]

Hardman, B.K. (2011) Teacher's perception of their principal's leadership style and the effects on student achievement in improving and non-improving schools. PhD dissertation, University of South Florida, Florida, US. [ Links ]

Harvey, P. & Martinko, M.J. (2010) Attribution theory and motivation. In N. Borkowski (Ed.) Organizational behavior in health care (pp.147-164). Boston: Jones and Bartlett. [ Links ]

Hayes, C.L. (2013) Examination of principals' perceptions on school climate in metropolitan Nashville public elementary schools. PhD dissertation, Tennessee State University Nashville, US. [ Links ]

Heider, F. (1958) The psychology of interpersonal relations. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Hendricks, K.H. (2011) Examining the impact of school climate on student achievement: A retrospective study. PhD dissertation, Purdue University West, Lafayette, US. [ Links ]

Hill, V. (2013) Principal leadership behaviors which teachers at different career stages perceive as affecting job satisfaction. PhD dissertation, Western Michigan University, US. [ Links ]

Hinkin, T.R. & Schriesheim, C.A. (2008) A theoretical and empirical examination of the transactional and non-leadership dimensions of the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ). The Leadership Quarterly 19(5) pp.501-513. [ Links ]

Hoy, W.K. & Miskel, C.G. (2008) Educational administration: Theory, research, and practice. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Huang, F.L., Cornell, D.G., Konold, T., Meyer, J.P., Lacey, A., Nekvasil, E.K., Heilbrun, A. & Shukla, K.D. (2015) Multilevel factor structure and concurrent validity of the teacher version of the authoritative school climate survey. Journal of School Health 85(12) pp.843-851. [ Links ]

Ifat, L. & Eyal, W. (2017) A discrepancy in teachers' and principals' perceptions of educational initiatives. Universal Journal of Educational Research 5(5) pp.710-714. [ Links ]

Islam, G. (2014) Social identity theory. In T. Teo (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Critical Psychology (pp.17811783). S.l.: Springer-Verlag.

Johns, G. (2008) Organizational behaviour: Understanding and managing life at work. Toronto: Pearson Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Kadi, A. & Beytekin, O.F. (2017) Metaphorical perceptions of teachers, principals and staff on school management. Journal of Education and Practice 8(15) pp.29-35. [ Links ]

Kliegler, A. (2016) Teachers and principals: Different perceptions of large-scale assessment. International Journal of Educational Research 75 pp.134-145. [ Links ]

Kor, J. & Opare, J.K. (2017) Role of head teachers in ensuring sound climate. Journal of Education and Practice 8(1) pp.29-38. [ Links ]

Krueger, J. (2018) Direct social perception. In Newen, A., De Bruin, L. & Gallagher, S. (Eds.) Oxford Handbook of 4E Cognition (pp.301-320). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Leedy, P.D. & Ormrod, J.E. (2013) Practical research. Planning and design. New Jersey: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Leong, L.Y. & Fischer, R. (2011) Is transformational leadership universal? A meta-analytical investigation of Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire means across cultures. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies 18(2) pp.164-174. [ Links ]

Lim, S. & Eo, S. (2014) The mediating roles of collective teacher efficacy in the relations of teachers' perceptions of school organizational climate to their burnout. Teaching and Teacher Education 44 pp.138147. [ Links ]

Maddock, L. & Maroun, W. (2018) Exploring the present state of South African education: challenges and recommendations. South African Journal of Higher Education 32(2) pp.192-214. [ Links ]

Mail & Guardian. (2019) Faction fights in KZN turn school playgrounds into battlefields. Macupe, B. August 2.

Malinen, O. & Savolainen, H. (2016) The effect of perceived school climate and teacher efficacy in behavior management on job satisfaction and burnout: A longitudinal study. Teaching and Teacher Education 60 pp.144-152. [ Links ]

Martin, T.F. (2012) An examination of principal leadership styles and their influence on school performance as measured by adequate yearly progress at selected title 1 elementary schools in South Carolina. PhD dissertation, South Carolina State University, Orangeburg, SC, US. [ Links ]

McMillan, J.H. & Schumacher, S. (2010) Research in education. Evidence-based inquiry. New Jersey: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Newman, S. (2014) Teacher perceptions of leadership styles in distinguished title I schools and the effect on teacher satisfaction and effort. DEd dissertation, A&M University-Commerce, TX, US. [ Links ]

Osman, A.A. (2012) School climate the key to excellence Journal of Emerging Trends in Education Research and Policy Studies 3(6) pp.950-954. [ Links ]

Pickens, J. (2005) Attitudes and perceptions. Organizational behavior in health care. Sudbury: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. [ Links ]

Pratami, F.A.R., Harapan, E. & Arafat, Y. (2018) Influence of school principal and organizational climate supervision on teachers' performance. International Journal of Scientific & Technology Research 7(7) pp.228-236. [ Links ]

Pulleyn, J.L. (2012) The relationship between teachers' perceptions of principal leadership and teachers' perception of school climate. PhD dissertation, University of Nevada, Reno, US. [ Links ]

Robinson, T. (2010) Examining the impact of leadership style and school climate on student achievement. PhD dissertation, Old Dominion University, Norfolk, US. [ Links ]

Schriesheim, C.A., Wu, J.B. & Scandura, T.A. (2009) A meso measure? Examination of the level of analysis of the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ). The Leadership Quarterly 20(4) pp.604-616. [ Links ]

Segalo, L. & Rambuda, A.M. (2018) South African public school teachers' view on right to discipline learners. South African Journal of Education 38(2) pp.1-7. [ Links ]

Silva, J.C., Amante, L. & Morgado, J. (2017) School climate, principal support and collaboration among Portuguese teachers. European Journal of Teacher Education 40(4) pp.505-520. [ Links ]

Sirisookslip, S., Ariratana, W. & Ngang, T.K. (2015) The impact of leadership styles of school administrators on affecting teacher effectiveness. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences 186 pp.1031-1037. [ Links ]

Swanepoel, C. (2008) The perceptions of teachers and school principals of each other's disposition towards teacher involvement in school reform. South African Journal of Education 28 pp.39-51. [ Links ]

Tzeni, D., Ioannis, A., Athanasios, L. & Amalia, S. (2019) Variation of perceptions of Physical Education teachers on the principal's level of effectiveness according to their age, gender, years of service in the same school and stage of service. Journal of Physical Education and Sport 19(1) pp.134-142. [ Links ]

Van Jaarsveld, M.C. (2016) Die verband tussen skoolhoofleierskapstyl, skoolklimaat en leerderprestasie. [The relationship between school principal leadership style, school climate and learner performance]. PhD dissertation, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa. [ Links ]

Vos, D. (2010) Bestuurstrategieë vir die vestiging van 'n effektiewe organisasieklimaat in die primêre skool [Management strategies for the establishment of an effective organisational climate in primary schools]. PhD thesis, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa. [ Links ]

Zehetmeier, S., Andreitz, I., Erlacher, W. & Rauch, F. (2015) Researching the impact of teacher professional development programmes based on action research, constructivism, and systems theory. Educational Action Research 23(2) pp.162-177. [ Links ]

Date of submission: 19 November 2019

Date of review outcome: 27 August 2020

Date of acceptance: 13 October 2020