Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Communitas

versão On-line ISSN 2415-0525

versão impressa ISSN 1023-0556

Communitas (Bloemfontein. Online) vol.28 Bloemfontein 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.38140/jjs.v48i1.7476

ARTICLES

This is undignified! Comparing the representation of human dignity on Cheaters and Uyajola 9/9

Motsamai MolefeI; Mthobeli NgcongoII

ICentre for Leadership Ethics in Africa, University of Fort Hare, Alice, South Africa. Email: mmolefe@ufh.ac.za (corresponding author). ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5030-6222

IIDepartment of Communication Science, Faculty of the Humanities, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa. Email: ngcongom@ufs.ac.za. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9309-7483

ABSTRACT

Calls have resonated within media scholarship and practice for more ethical oversight in the production and distribution of media content by producers through ethical frameworks. This article intervenes in the literature on the global debate around media ethics frameworks by focusing on the under-explored value of human dignity in the context of television reality shows. The article makes two interventions in relation to the value of dignity, one theoretical and another applied. The theoretical intervention, contrary to the tendency to rely on Western cultures and theories to conceptualise human dignity, draws from a Global South perspective, specifically from the African ethical idea of Ubuntu that proffers a relational (as opposed to an individualist) conception of human dignity. The applied ethics intervention responds to the scant literature focusing on the representation of human dignity in media ethics. The article uses Ubuntu's theory of human dignity to compare the representation of participants on similar factual television shows from the United States of America (USA) and South Africa depicting relational infidelity. Multimodal critical discourse analysis from three episodes of Cheaters and three episodes of South Africa's Uyajola 9/9 (n=6) reveal that human dignity in the representation of the participants in these two shows is often neglected in the media production process, leaving many questions about the global and local media ethics of these two reality shows.

Keywords: global media ethics, human dignity, reality television, multimodal critical discourse analysis, Ubuntu, audiences, participation, Global South

INTRODUCTION

There are growing calls within media scholarship and practice for more ethical oversight in the production and distribution of media content as part of the media's responsibility for authentic and respectful representations (Ward 2021). This article responds to the lacuna in the literature on media ethics in relation to the concept of human dignity (Wasserman 2010). It proffers a two-pronged response. On the one hand, it suggests a theoretical intervention where it draws from the Global South to articulate an African conception of human dignity. On the other hand, it deploys this African conception of human dignity to evaluate the place or relevance of human dignity in reality dating TV shows. One major insight that will emerge in the article in relation to human dignity as a crucial value in media ethics is that reality dating shows have a responsibility not to humiliate human beings in the creation and distribution of content.

The article is motivated by three important considerations. First, the literature in media ethics has tended to focus on the values of non-violence and truth, and this has resulted in the general neglect of the relevance of the value of human dignity (Christians 2010). We understand human dignity to represent the moral distinctiveness and preciousness of human beings. Simply put, human dignity refers to human worth, an inherent, inalienable, and superlative value (Donnelly 2015). Underlying the question of human dignity in the context of media production and the distribution of content is whether it recognises, affirms and protects human dignity, or it degrades it. Thus, this study is important as it challenges us to think seriously about the ethics of representation, particularly with the eye towards recognising human dignity, or understanding what goes wrong when we fail to value it (Ward 2013).

The second motivation has to do with the tendency in the literature to rely on Western epistemic and axiological resources to imagine and construct the idea of human dignity. This article seeks to imagine the idea of human dignity from an African context. This is important because often ethical discourses in media (and other disciplines) tend to assume the Western frame as the default ethical lens (Wareham 2017). Motivated by a desire and the ideal of a truly global, diverse, and decolonised media ethics, the authors aim to contribute to a cross-cultural conversation by employing an African perspective as a voice to reflect on human dignity (Chimakonam 2017; Molefe & Alsobrooks 2023). Finally, this article is motivated by the desire to imagine the potential contribution this intellectual reflection on human dignity, considering African thought, can make to practical or applied issues in the space of reality shows, which have become a part of our lives. It aims to provide a criterion for evaluating an acceptable reality TV show as one that does not humiliate human beings.

The authors note that the aim of the article is not to suggest that African ethics is the only and best way to interact with the value of human dignity. Rather, the modicum idea is that perspectives from the Global South also warrant serious attention in (media) ethics because they also have something to contribute (Wareham 2017). Moreover, the authors do not want to suggest that the theory of human dignity appealed to in this study is the only one in the African context. Rather, the appeal to Thaddeus Metz's African ethics is motivated by the desire to open the conversation and debate, and to do so, we must start somewhere, and we chose to begin it in this fashion. There are other interesting accounts of human dignity in the literature in African philosophy, and certainly also in other traditions.

Moreover, a focus on human dignity highlights the potentially terrifying consequences that could result from the unethical representations of participants on reality television (Deery 2015; Hill 2020; Ouellette 2014). Indeed, questionable production processes such as paid appearances, scripting and lack of consent of some participants have bred distrust among audiences of reality TV about its authenticity, as well as ethical integrity. In response to this, viewers have voiced criticism of these shows through the formation of virtual communities for each show (Ngcongo 2022). These have been facilitated, for example on X through hashtag (#) communities (Bruns 2013). Thus, the erosion in the trust of media content has deepened, leading to a need for more work into restoring faith in media through applied and theoretical media ethics frameworks. This contribution makes an intervention by focusing on human dignity.

This article suggests that the production practices of reality TV (RTV) are not value-free and are packaged in ways that may marry an inauthentic spectacle with the difficulties of infidelity in romantic relationships. Using the concept of human dignity as the conceptual foundation, this article compares the representation of participants on similar factual television shows from the USA and South Africa depicting relational infidelity. Multimodal critical discourse analysis from three episodes of Cheaters and three episodes of South Africa's recent localised adaptation of Cheaters called Uyajola 9/9 (n=6) might reveal the extent to which human dignity should be a prominent consideration in relation to the representation of participants in the media production process. The authors believe that these shows present a poignant case study for attempts to reconcile and balance the ethical demands for both truth and dignity in media representation. The dilemma of uncovering the truth of relational infidelity with that of respecting the dignity of participants on the shows is brought in stark contrast in this reality format and gives us important analytical units of analysis for media ethics. This article poses three questions for which answers are pursued through the analytical tools of multimodal critical discourse analysis (MCDA):

Q1: How does reality TV on infidelity co-opt the spectacle to (mis)represent the human dignity of participants as depicted in Cheaters and Uyajola 9/9?

Q2: What are the similarities and differences in the (mis)representation of human dignity of participants as depicted in Cheaters and Uyajola 9/9?

Q3: What are the links between media ethics and human dignity on reality television around infidelity as depicted in Cheaters and Uyajola 9/9?

REALITY TELEVISION AND HUMAN DIGNITY

Reality television (RTV) has arguably transformed the television landscape since its impressive rise in the early 2000s (Deller 2011; 2016; 2020). From production to consumption, RTV challenges the conventional norms of television. Its limited scripting, reliance on non-professional actors as participants, as well as the relative ease in location means that RTV can be produced with a modest budget while being in the position to potentially make huge returns (Essany 2013). Quick production times also translate to content that can be produced consistently without many of the hurdles associated with traditional television programming.

Much can be said about the formulaic production practices of reality television, including its borrowing from other more recognised formats (Deery 2015). This is the case with Cheaters and its South African version, Uyajola 9/9, which can be classified as formats that borrow from melodramatic parody (Harry 2008). In other words, the shows are media spectacles, or at least have that element as one of their essential elements. On the other hand, the incorporation of docudrama, investigative journalism and other serious genres is important to position the shows as representations of the truth (White 2006).

The shows' focus on gaining justice for the wronged party through uncovering the "truth" of the partner's infidelity suggests a moralistic point of departure by the franchises. By claiming to uphold the values of self-control and faithfulness in romantic commitments, the shows situate themselves as promoting ethical conduct (Harry 2008). On closer inspection, a tension can be seen between how some production practices may be ethically questionable, while pursuing the ethical ideal of truth (White 2006). However, this ethical tension in the representations of the shows has scarcely been subjected to any rigorous cross-cultural comparative media ethics critique. This article proposes human dignity as a lens through which to analyse the authentic ethical representation of participants on Cheaters and Uyajola 9/9.

To proceed, it is crucial to clarify and justify the focus on human dignity and an African perspective. It is cliché in ethical discourses focusing on human dignity to begin by pointing out the mercurial status of this concept (Miller 2017). Different people in different contexts find it appealing for a variety of conflicting or divergent purposes, which might lead one to wonder if such a concept can be useful at all in intellectual engagements (Schroeder & Bani-Sadr 2017). To deploy the concept of human dignity in an intellectually responsible way, one should begin by recognising it as belonging among those concepts described as essentially contested (Rodriguez 2015). To identify human dignity as an contested notion denotes that there is no agreement about its core meaning. There are at least two ways to relate to the contested status of human dignity, one negative and another positive (Molefe 2022). This article favours the latter.

The negative approach to the contested nature of the concept of human dignity considers it useless in ethical theory. Often these scholars would urge us to repudiate it altogether if we are aiming for a meaningful intellectual engagement in ethics (Macklin 2003; Birnbacher 2005). The positive view recognises the contested nature of the concept but urges us to recognise that we can still use the concept in intellectually responsible ways (Misztal 2013; Ikuenobe 2017). Two arguments are possible to respond to the negative view of the contested nature of human dignity. On the one hand, we can argue analogically that the fact that concepts like democracy and development, among others, are contested does not imply that we cannot speak meaningfully about them. In fact, recently there have been interesting engagements on these concepts in the literature. Consider Bernard Matolino's (2019) engagement on democracy in the African context or consider Martha Nussbaum's (2011) exposition on development considering her capabilities approach. The second argument suggests that, in some sense, the problem is not with the concept of human dignity per se, but it lies at the level of its conceptions (or theories of it). In other words, the suggestion is that, at rock bottom, the concept of human dignity captures the abstract idea or even a persistent moral intuition that there is something morally distinctive, precious, and special about human beings (Metz 2012; Schroeder 2008). Indeed, scholars suggest varying accounts of the metaphysical capacities that account for the value of human dignity (see for instance Kant 1996; Schulman 2008; Nussbaum 2008, 2011; Miller 2017).

We now consider the distinct senses or meanings associated with the concept of human dignity in the literature. This is important for identifying the concept of human dignity that is relevant in media ethics. The ethical framework proposed to capture global media ethics requires us to reckon with the sacredness of being human (Christinas 2008). It explains human dignity in terms of human sanctity or scaredness. There are various meanings associated with the concept of human dignity in the literature (Sulmasy 2008; Rosen 2012; Michael 2014; Miller 2017; Ikuenobe 2017). Scholars draw a distinction between what they call status and achievement dignity (Michael 2014). They also refer to status dignity in terms of inherent or intrinsic dignity (Sulmasy 2008; Hughes 2011). Status/inherent/intrinsic dignity refers to the kind of value an individual has merely for being who they are. That is, merely being human is necessary and sufficient for having dignity. One does not earn dignity. In other words, it does not depend on performance. If one has the relevant metaphysical property then he/she has it; if not, he/she does not have it. Achievement dignity, or inflorescent dignity, is the function of developing the intrinsic capacities that secure one's status dignity. The positive development or nurturing of these capacities to manifest excellence or virtue amounts to achievement or inflorescent dignity (Sulmasy 2014; Michael 2014). This is a kind of dignity we are not born with; it comes in degrees relative to how well one conducts himself/herself and which one can lose if he/she performs dismally.

It is status/intrinsic dignity that lies at the heart of media ethics, which often scholars capture in a quasi-religious parlance of "scaredness of human life" (Christians 2010). The use of status or intrinsic dignity offers a non-religious presentation of the concept, which renders it useful to secular and multi-cultural societies. It is the value of dignity associated with human beings - status or intrinsic dignity - that content producers and distributors must be cognisant of and they must equally be aware of the duties it imposes on them. The idea of human dignity is usually associated with respect. That is, human dignity positions one as an object of ethical concern, and this concern is expressed via respect. We have duties of respect towards beings of human dignity (Dillon 2011). We can distinguish between two distinct kinds of respect: recognition and appraisal respect (Darwall 1977). Recognition respect is a function of respecting something by virtue of certain facts about it. In the case of human dignity, we respect them in virtue of recognising their human status; whereas appraisal respect emerges consequent to merit and esteem - it is a kind of respect that tracks excellent performance. Human dignity warrants the kind of respect that is a function of recognising and responding appropriately to the fact of being human. Considering this, all human beings, by merely being human, are owed respect and are owed equal respect (Rosen 2012).

One useful way to flesh out the respect associated with human dignity is in terms of constrains, aid and equality (Jaworska & Tannenbaum 2018). The idea of constraints implies that we have restrictions on not harming or interfering with a being of dignity (Beyleveld & Roger 2001). The basic idea is that certain ways of treating a human being are wrong and they can harm them in their status as a human being. The idea of dignity imposes on us negative duties not to harm a human being. The worst forms of harm against human beings in relation to their status dignity involve their objectification, inferiorisation, and/or humiliation. The idea of aid implies that, all things being equal, we have a duty to assist or empower a being of dignity (Beyleveld & Roger 2001). Some scholars think of aid as our duty to empower bearers of dignity (Molefe 2022). In summary, to respect a being of dignity requires that we do not harm or interfere with them (constraints), we aid them as far as is possible (duties of empowerment), and we treat them fairly (egalitarianism). Failure to respect persons, that is, to harm them, not aid them, and treat them unfairly may be construed in terms of humiliating or degrading human beings in terms of their status dignity.

Below we consider an African theory of human dignity. This view of dignity is hewn from the moral concept of Ubuntu, which embodies the essence of an African axiological orientation (Ramose 1999; Shutte 2001; Eze 2005). This ethical view is usually captured by appealing to the saying among the Nguni languages, umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu; in English, a person is a person through other persons (Ramose 1999). One of the things that stands out from this saying is the importance of social relationships. Ontologically, the saying construes the lived experience of being (human) in terms of interdependence, and normatively it prescribes that we should relate positively to others. It is the relationality of Ubuntu that Thaddeus Metz, one of the leading scholars of Ubuntu, invokes to ground an African conception of human dignity. We can distinguish between individualistic and relational theories of human dignity (Behrens 2011). Individualistic theories account for it by an appeal to an internal feature of an individual. Kant's account of human dignity is individualistic in that it explains it by appealing to some psychological property - the capacity for autonomy.

Relational interpretations of human dignity account for it in terms of the human capacity to connect or interact with others. The difference between the individualistic and relational theories of human dignity is that the former appeals to a capacity that makes no essential reference/connection to another person, whereas a relational conception requires this reference to another. On Metz's African relational view of human dignity, he states, "W]hat makes us more special than the animal, vegetable, and mineral kingdoms is that we can love others in a way that no other entity can". Note that Metz grounds our moral worth and the superlative status of human dignity on the human capacity to love, which, in other instances, he refers to as the capacity for harmony/friendliness (Metz 2012; 2021). The capacity for friendliness is constituted by two kinds of relationships - social identity and solidarity (Metz 2007). Social identity refers to conceiving of one's identity in terms of a social group (rather than I), where one shares common goals with the group and collaborates with members of the group to pursue the commonly shared goals. Solidarity refers to a social relationship characterised by caring or improving another's well-being for their own sake. Put in simple terms, identity refers to sharing a way of life and solidarity for caring for others' well-being. Thus, we have dignity because we have the capacity for friendliness (the ability to share with and care for others). How might this view of human dignity as friendliness contribute to media ethics?

METHODOLOGY

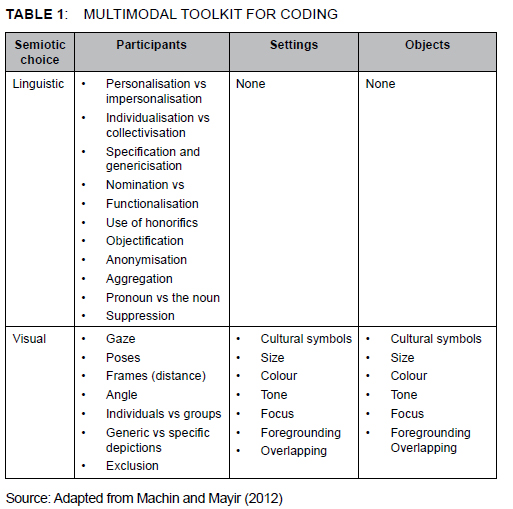

To effectively explore the underlying representations of human dignity on Cheaters and Uyajola 9/9, we adapted a Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis (MCDA) toolkit advanced by Machin and Mayir (2012). MCDA not only results in a better understanding of media texts (Coskun 2015), but it has also been shown to be particularly productive in the analysis of reality television (Monson et al. 2016; Mbuyani-Memani 2017). This is because at the heart of MCDA is an attempt to analyse how both the linguistic and the visual choices in a given text may convey a particular ideological meaning to audiences (O'Halloran 2004; Van Leeuwen & Jewitt 2008). In other words, MCDA seeks to go deeper than manifest meanings to uncover the latent meanings in media texts (Coskun 2015). The single focus on language that characterises critical discourse analysis is thus counterbalanced by incorporating the visual semiotic choices in communicative texts.

The toolkit by Machin and Mayir (2012) focuses on the visual choices in the placing of objects and the depiction of settings, as well as how participants are represented both visually and linguistically. This then provides three elements to focus on in the analysis of a text: objects, settings, and participants. The elements were then distilled into fine-grained characteristics to create a coding scheme for the data. Objects and settings were grouped into seven visual choices and the representations of participants into ten linguistics choices, as well as seven visual choices, as seen in Table 1 below.

The authors decided to sample six typical episodes from the recent seasons of Cheaters (three episodes) and Uyajola 9/9 (three episodes), as this has been shown to be a fruitful approach for making qualitative sense out of a large set of reality television data (Monson et al. 2016). Conversant with studies on MDCA in reality TV media texts (Smit & Bosch 2020; Mbunyuza-Memani 2017), we chose episodes in the beginning, middle and latter part of each season for an appropriate expert sample. We chose episodes from each season, which featured participants who are characteristically chosen for many of these shows' episodes to be able to provide a thick descriptive account within this context (Smit 2016).

FINDINGS

We began by watching the saved and downloaded episodes for each show, making initial notes, as well as highlighting important parts. The linguistic and visual choices for each episode were summarised in a table format, along with topic summaries for each episode, as well as for each semiotic choice. The linguistic choices were verified through independent coding processes and comparison overlapped in how the MCDA toolkit was used by the coders. The profile matrix also allowed both franchises to be compared much easier by looking at the similarities and omissions in the linguistic choices for the production process.

Both Cheaters and Uyajola 9/9 run on a similar format for the shows, with a few exceptions in the opening sequence. Cheaters opens with the host of the show, Peter Penkey, introducing the 'complainant' for the episode. We are told about their age, profession, how they met their partner, and what the current issues are that prompted suspicions of infidelity. The host then meets with the complainant to show them surveillance video footage of what they have found about their partner's infidelity. This is then followed by going to the unfaithful partner's physical location to confront them and the person with whom they are cheating. The Uyajola 9/9 introduction on the other hand consists of the host, Jub Jub Maroganye, introducing himself and the location in the country where the episode is being shot, followed by the host meeting the complainant to hear their side of the story. Uyajola 9/9 also introduces a local South African feel to the format using local languages and the spectacle of the crowd during the confrontation.

Cheaters

The semiotic choices in the show attempt to complement the linguistic as well as the visual choices in how the participants are represented. There is a clear sense of the transitions into the three different settings and scenes in each episode: the introduction by Peter Pankey, which is followed by a solo on-camera explanation of the complainant of the episode regarding their relational issues; secondly, the debriefing that happens on location; and lastly, the confrontation that also occurs on location. The objects in each setting are foregrounded and slightly contextualised. The objects are also referred to, for instance during the debriefing and confrontations, as accomplices to the unfaithfulness.

The linguistic choices in how the participants are represented are minimal, consisting mainly of personalisation, individualisation, and a lack of anonymisation. Each complainant is given an opportunity at the beginning of the episode to convey their love story, as well as why they suspect their partner is being unfaithful. This creates a sense of both a personal story that the viewers can relate to and a sense of the individual identity of the complainant. Given the importance of agency, they are not simply a victim but have come to the show as a form of empowering themselves with truth. Because the unfaithful partner is never provided the same on-screen opportunity to connect with the audience and tell their story, they are depersonalised. The unfaithful partner and the third party are in turn collectivised, especially during the portion where the surveillance footage is being narrated to the audience. Collective terms such as "the pair", "the love birds", and "clandestine couple" are used when referring to the visuals. The narration also adds an element to the linguistic choices not reflected in the MCDA toolkit, which we refer to as descriptions. The descriptions of the unfaithful party represent them as nefarious, while couched in witty language.

Visual choices, as well as the linguistic choices, are presented in a dynamic interplay. The visual choices in the representation of the participants, particularly the unfaithful partner, rely on close frames, level angles, and depicting them in a villain-like manner. The use of surveillance visuals is particularly pronounced in this format. This provides an atmosphere of authenticity and a depiction of truth telling through the provision of evidence, both for the audience through the narration of the footage, as well as for the complainant during the briefing.

Uyajola 9/9

The three episodes analysed show glaring patterns in terms of both the linguistic and the visual choices in the production of the show. Maybe the focus was more on the semiotic choices made about the participants' representation than on objects and settings; the objects and settings were rather part of the background and were de-emphasised, probably not to take away from the story at hand. The first setting for each episode was the van where the host meets the complainant to be briefed about the story and to provide an update on the surveillance evidence that corroborates the complainant's story. The second most important setting was where the unfaithful partner was confronted while in the act of infidelity. In both cases the objects of surveillance and recording devices were emphasised and de-emphasised. These symbols help to authenticate the truth and realness of the evidence provided and the quest for the truth from the offending partner.

The representation of the participants is the focus of each episode, in particular the use of polarising frames. The complainant is depicted as a helpless victim from the start of the episode, while the unfaithful partner is framed as a deceptive villain. The host opens the episodes by claiming that he wants to uncover the truth on behalf of the complainant and offer them closure or even a way to solve the lack of certainty about their partner's loyalty. In other words, the host takes the moral position as the vanguard of truth. By highlighting the plight and the side of the complainant, the producers make two linguistic choices. First is the individualisation of the complainant by focusing on their narrative, second is the personalisation through referring to them by their name, as well as protecting them during the confrontation. By contrast, the offending partner is both depersonalised and simultaneously objectified. The host neither refers to their name, nor speaks to them in a kind tone. Their bodies are sometimes shown or while they are in a moment that would otherwise not be broadcast publicly. In Episode 22, for example, Bheki is caught naked in bed during the confrontation scene. The blankets are pulled away by the crew, leaving his naked body exposed for the cameras. The host repeatedly makes objectifying comments about how big his penis is. This reduces the unfaithful partner to a body part, while simultaneously robbing him of a voice. When the unfaithful partner tries to explain their side of the story, they are either dismissed as a liar or ganged up on by the host and the complainant. The cheers of the crowd, as seen in Episodes 21 and 5, add to the sense of the odds being stacked against the unfaithful partner.

The visual choices appear to complement the linguistic choices made in the production process. There is the predominant use of close frames, as well as level eye angles, especially during the confrontation. These give a sense of the emotionally charged nature of the circumstances. The camera also focuses on the body parts of the unfaithful partner, as seen for instance in Episode 22. The simultaneous individual visualisation of the complainant, and the lumping of the unfaithful partner with the one they have been caught with, further reinforces the depersonalisation of the unfaithful partner by making them visually generic. Therefore, their story becomes lost in the sea of other unfaithful partners caught cheating. They become just cheaters.

Similarities and differences in the two shows

There appears to be many overlaps between the two shows, but the differences are also evident. Cheaters appears to try to uphold the agency and respect of all parties, but violence is much more uncontrolled in the show than on Uyajola 9/9. This is evidenced in how the hosts speak to the participants on the show. While Jub Jub is often confrontational with those caught in the act, Peter Pankey attempts to reason with them. There is also the verbal barrage, which amounts to impersonalisation and genericisation on Uyajola 9/9, mainly perpetrated by Jub Jub. Peter Pankey attempts to show those caught in infidelity how their actions have hurt their partner and to reconcile the two parties, where possible, asking questions such as, "Are you two going to work things out?", and "Are you going to throw away all the years you have invested into each other". Thus, the agency of the perpetrator is acknowledged more than on Cheaters as they are given an ultimatum to choose either in most episodes, but the third party is sometimes left reeling without consolation. They are objectified.

In both shows the offending party and perpetrator are collectivised. In Uyajola 9/9 the host chastises both parties caught in infidelity, with more focus of the cheating partner. This is done through sarcastic and scathing rhetorical questions such as "Both of you are having fun?". This is much less the case on Cheaters, where the focus of the host is on the cheating partner, and only coming in to speak to the third party for an explanation of why they would be involved with someone who is already in a relationship. Both parties caught in the act is seen as responsible for the infidelity. The shows do not attempt to give us a nuanced narrative of all the parties involved, but focus of the individual action and hurt of the one who is cheated on.

There is a much more distinct visual separation of the settings on Cheaters, with the focus being on the surveillance footage. This is punctuated by the narration over the different segments, which helps guide the viewer through each setting. The focus on Uyajola 9/9 is on the confrontation scene, which consists of Jub Jub interrogating the offending party. This emphasises the focus of Uyajola 9/9 on the impersonalisation of the one caught in infidelity. However, the crew in both shows play a big part in avoiding being in the frame so that the setting and the participants can be better seen. This becomes difficult to do for both crews during the confrontation scene as these involve either a closed space in the private residence of those caught in infidelity or a scuffle in a public setting with intervention needed from the crew to de-escalate the physical altercation.

DISCUSSION

The linguistic and visual choices made by reality television media on infidelity offer interesting insights into media ethics. The linguistic choices used on Cheaters revolving around the individualisation of the complainant and the collectivisation of the unfaithful partner, along with the third party, provide interesting insights on the lack of human dignity in the representation of the participants in the show. This lack of dignity centres on the offending partner, as well as the third party. Human dignity as friendliness offers us an interesting way to make sense of these three aspects. How might the idea of human dignity as friendliness grasp the individualisation and personalisation of the victim of cheating, and how might it deal with the collectivisation, depersonalisation, and generalisation of the perpetrator. Remember that human dignity as friendliness requires us to appreciate the centrality of friendly relations as the moral mode of existence (Metz 2012). The individual, as much as he/she must be recognised as an individual, he/she must never slip from the importance of relations where friendliness is nurtured (Metz 2021).

The visual choices on Cheaters centred on close frames, level angles, and visual depictions of the participants that attempted to represent the participants as their basest and bare selves. The visual choices therefore complement the linguistic choices made by the producers. Key here is the use of surveillance footage and the narration over it. This shapes a particular idea about the offending partner and the third party even before the confrontation. In doing this, the show limits the volition of the offending parties in articulating their version of the events and limits their capabilities through non-consensual forms of surveillance on behalf of the complainant (Rosen 2012). The use of surveillance could be argued to be a form of care for the complainant, but the equal status of respect for all required by an ethical commitment to human dignity in media ethics makes this an asymmetrical act that is undignified (Jaworska & Tannenbaum 2018). Surveillance may be necessary to gain the truth about the conduct of the suspected cheating partner. What we do with this truth is where concerns about dignity emerge. The surveillance could be used to confirm or negate the suspicious partner concerns. The public airing of the surveillance is objectionable in that it is characteristically unfriendly owing to the unnecessary public exposure, which is intended to humiliate the cheating partner and the third party. Friendliness, cognisant of the fact of lack of consent on the part of those 'watched' and their right to privacy, would recommend the results of the surveillance be shared privately with the complainant.

Although Uyajola 9/9 makes use of the same linguistic choices as Cheaters, it goes a step further by using objectification. Therefore, Uyajola 9/9 provides a poorer execution of balancing truth and non-violence with human dignity in the representation of the participants on the show. Through the additional focus on the objectification of the offending partner, as well as the third party, the show enters into the realm of verbally harming the participants. The verbal harm and abuse then spill over into physical harm through an altercation between the complainant and the offending parties. This goes against the core of showing respect towards participants by also considering constraints and aiding them in recognising their status dignity (Darwall 1977). Uyajola 9/9's visual choices also complement the linguistic choices through close angles that individualise the complainant and collectivise the offending parties, especially during the confrontation. These set of choices once more undermine the pursuit principle of human dignity in ethical media practice in not according respect to the offending partner and the third party (Dillon 2011).

Both shows make visual choices that are similar through close angles as well as the collectivisation of the offending party and the third party engaged in acts of infidelity. The close angles favour the personalisation of the complainant, while simultaneously not according the same to the offending party. There is therefore an inconsistency in the show in the application of status dignity, where each individual ought to be accorded equal respect merely because they are human (Sulmasy 2008; Hughes 2011). It may be argued that due to the questionable acts of the offending party and the third party that they have lost moral dignity and should not be accorded any dignity at all (Sulmasy 2014; Michael 2014). However, this argument and the underlying choices of the show, which point to its support, go against the very notion of status dignity (Sulmasy 2008; Hughes 2011). The offending party and the third party should still be accorded status dignity in recognition of their humanity, not because of any action or ill action they have taken. It is one thing for a person to lose their reputation and for them to be embarrassed, but status dignity demands that we still recognise them as beings deserving a minimum of respect merely because they are human. To strip the offending partner and the third party of their status dignity amounts to their dehumanisation as they are being treated as less than human in how they are depicted, which concretely manifests in their humiliation.

The presence of a segment in Cheaters where the viewers are shown the surveillance footage accompanied by controversial narration differs from the choices made in Uyajola 9/9. However, the use of asymmetrical forms of surveillance (Lyon 2001) in both shows again brings into question the capabilities approach (Beyleveld & Roger 2001) to respect, which is demanded by the principle of human dignity as a media ethic. Since the offending partner as well as the third party are being followed without their consent and knowledge, their recognition of human volition is undermined (Lyon 2007) and by extension their status of human dignity. This brings in an element of deception in the production process in that the truth about being under surveillance is only made known to the offending partner at the confrontation stage (White 2006). Since truth telling is essential for the sacredness of human life, the lack of truth telling by the production team about surveillance camera in homes and private investigators following the offending partners clearly opposes this principle (Lyon 2018).

The final visual choice made by the two shows is the emphasis on the time spent on the confrontation scene between the complainant, the offending partner, and the third party. This is arguably the portion where most of the linguistic barrage, already mentioned, is hurled at the offending partner and the third party. But more concerning is that this is where most of the physical violence on the shows takes place and is depicted. By exposing the three parties involved to the possibility of violence and further recording the physical altercation in this scene, the producers inadvertently promote violence, thereby undermining the pursuit of respect as constraint to harm (Molefe 2022). The promotion of human dignity demands that media practitioners promote peace actively in the sociology of production (Metz 2012). However, the depiction of physical altercations in these shows is inconsistent with the principle of non-violence that should be part of a media ethic (Christians 2010).

Overall, both Cheaters and Uyajola 9/9 have more similarities amidst the key differences in both the linguistic and visual production choices that inform media ethics. Taken together, the choices made in these reality shows on infidelity do not live up to the standard set by a media ethics that espouses human dignity in its sociology of media production. The shows fall far short of according status dignity to all parties involved consistently through the principles of constraints and capabilities respect (Beyleveld & Roger 2001), truth telling, as well as non-violence (White 2006). Pursuit of these principles in the shows would call for a total overhaul of their current format in order to accord narrative and voice to all parties, in addition to reconciliation, peace and transparency.

CONCLUSION

The paper set out as its rationale that the concept of human dignity as a shared cross-cultural norm (Donnelly 2015) is a fruitful lens from which to argue for a global media ethics framework (Christians 2010). Such a framework would inform the ontological decision-making in the sociology of media production. Using Cheaters and Uyajola 9/9 as case studies to assess this argument, the paper found that both shows fall far short of the standard that a global media ethics framework based on human dignity would entail. The decision making in the linguistic and visual choices in both shows lack the substantive and consistent application of according status dignity to all participants, especially the offending partner and the third party. The shows lack of pursuit of truthful practice through asymmetrical surveillance, the depiction of physical violence, and the lack of respect mainly of the offending partner and the third party point to a lack of human dignity in the production choices of the shows. A complete overhaul of the format of the shows would be needed if human dignity is to be applied as the ethical framework for the choices made in the production of these shows. Overall, the paper has shown the robustness of human dignity as a possible ethical framework for media production, while simultaneously showing the cross-cultural applications of such a media ethics framework.

REFERENCES

Birnbacher, D. (2005). Human cloning and human dignity. Reproductive BioMedicine Online 10(1): 50-55. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1472-6483(10)62206-7 [ Links ]

Christians, C.J. 2010. The universal ethics of being. In: Ward, S.J. & Wasserman, H. Media Ethics Beyond borders: A Global Perspective. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Çoşkun, G.E. 2015. Use of multimodal critical discourse analysis in Media Studies. The Online Journal of Communication and Media 1: 40-43. [ Links ]

Darwall, S. 1977. Two kinds of respect. Ethics 88: 36-49. https://doi.org/10.1086/292054 [ Links ]

Deery, J. 2015. Reality Television. New York: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Deller, R. 2011. Twittering On: Audience Research and Participation Using Twitter. Participations 8(1): 216-246. [ Links ]

Deller. R.A. 2016. Star image, celebrity reality television and the fame cycle. Celebrity Studies, 0: 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2015.1133313 [ Links ]

Deller, R.A. 2020. Reality Television: The TV Phenomenon that Changed the World. Bingley: Emerald Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1108/9781839090219 [ Links ]

Donnelly, J. 2015. Normative versus taxonomic humanity: Varieties of human dignity in the Western tradition. Journal of Human Rights 14, 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1080/14754835.2014.993062 [ Links ]

Essany, M. 2013. Reality Check: The Business and Art of Producing Reality TV. Massachusetts: Focal Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780080927831 [ Links ]

Harry, J.C. 2008. Cheaters: "Real" Reality Television as Melodramatic Parody. Journal of Communication Inquiry 32(3): 230-248. DOI: 10.1177/0196859908316329 [ Links ]

Hill, A. 2020. Reality TV: Performances and Audiences. In: Wasko, J. & Meehan, E.R. A companion to Television. California: Wyle-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119269465.ch10 [ Links ]

Hughes, G. 2011. The concept of dignity in the universal declaration of human rights. Journal of Religious Ethics 39: 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9795.2010.00463.x [ Links ]

Ikuenobe, P. 2017. The communal basis for moral dignity: An African perspective. Philosophical Papers 45: 437-469. https://doi.org/10.1080/05568641.2016.1245833 [ Links ]

Jaworska, A. & Tannenbaum, J. 2018. The grounds of moral status. In: Zalta E. N. (Ed.). The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. Available at https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2013/entries/grounds-moral-status/ [Accessed on October 30 2019]. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190634384.003.0014 [ Links ]

Lyon, D. 2001. Surveillance society: Monitoring everyday life. Milton Keynes: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Lyon, D. 2007. Surveillance, power, and everyday life. In Mansell R., Avgerou, C. Silverstone, R.& Quah, D. (Eds.). The Oxford handbook of information and communication technologies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Lyon, D. 2018. The culture of surveillance: Watching as a way of life. Boston: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Macklin, R. 2003. Dignity is a Useless Concept. BMJ 327: 1419-1420. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7429.1419 [ Links ]

Machin, D. & Mayr, A. 2012. How to do Critical Discourse Analysis: A Multimodal Introduction. California: Sage. [ Links ]

Michael, L. 2014. Defining dignity and its place in human rights. The New Bioethics, 20: 12-34. https://doi.org/10.1179/2050287714Z.00000000041 [ Links ]

Mbunyuza-Memani, L. 2018. Wedding Reality TV Bites Black: Subordinating Ethnic Weddings in the South African Black Culture. Journal of Communication Inquiry 42(1): 26-47. https://doi.org/10.1177/0196859917726047 [ Links ]

Metz, T. 2007. Toward an African Moral Theory. Journal of Political Philosophy 15(3): 321-341. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9760.2007.00280.x [ Links ]

Metz, T. 2012. An African theory of moral status: A relational alternative to individualism and holism. Ethical Theory and Moral Practice: An International Forum, 14: 387-402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10677-011-9302-y [ Links ]

Metz, T. 2021. A relational moral theory: African ethics in and beyond the continent. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198748960.001.0001 [ Links ]

Miller, S. 2017. Reconsidering dignity relationally. Ethics and Social Welfare 2: 108-121. https://doi.org/10.1080/17496535.2017.1318411 [ Links ]

Molefe, M. 2021. Partiality and impartiality in African philosophy. New York: Lexington Books. [ Links ]

Monson, O., Donaghue, N. & Gill, R. 2016. Working hard on the outside: a multimodal critical discourse analysis of The Biggest Loser Australia. Social Semiotics 0: 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2015.1134821 [ Links ]

Ngcongo, M. 2022. Exploring the Virtual Culture of Reality Television Communities: Lessons From #Date My Family. Television & New Media 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/15274764221138235. [ Links ]

Nussbaum, M. 2011. Creating capabilities: The human development approach. Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674061200 [ Links ]

O'Halloran, K. 2004. Multimodal Discourse Analysis: Systematic Functional Perspectives. London: Continuum. [ Links ]

Smit, A. 2016. Reading South African Bridal Television: Consumption, Fantasy and Judgement. Communicatio 42(4): 63-78. https://doi.org/10.1080/02500167.2016.1252781 [ Links ]

Smit, A. & Bosch, T. 2020. Television and Black Twitter in South Africa: Our Perfect Wedding. Media, Culture and Society 42(7-8): 1512-1527. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443720926040. [ Links ]

Sulmasy, D. 2009. Dignity and bioethics: History, theory, and selected applications. In The President's council on bioethics, human dignity and bioethics: Essays commissioned by the President's council (pp. 469-501). Washington DC: President's Council on Bioethics. [ Links ]

Van Leeuwen, T. & Jewitt, C. 2008. Handbook of Visual Analysis. California: Sage. [ Links ]

Ward, S.J.A. 2013. Global Media Ethics: Problems and Perspectives. New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell. [ Links ]

Ward, S.J.A. 2021. Handbook of Global Media Ethics. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32103-5 [ Links ]

Wasserman, H. 2010. Media Ethics and Human Dignity in the Postcolony. In: Ward, S.J. & Wasserman, H. Media Ethics Beyond borders: A global Perspective. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

White, M. 2006. Investigating Cheaters. The Communication Review 9(3): 221-240. DOI: 10.1080/10714420600814889 [ Links ]

Date submitted: 11 September 2023

Date accepted: 11 October 2023

Date published: 15 December 2023