Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Communitas

versión On-line ISSN 2415-0525

versión impresa ISSN 1023-0556

Communitas (Bloemfontein. Online) vol.28 Bloemfontein 2023

http://dx.doi.org/1038140/com.v28i.7622

ARTICLES

The impact of a one-day adventure-based experiential learning programme on the communication competence of adult learners at a business school

Dalmé MulderI; Hermanus J. BloemhoffII

IDepartment of Communication Science, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa. Email: mulderd@ufs.ac.za (corresponding author). ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8491-3792

IIDepartment of Exercise and Sport Science, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa. Email: coetzeef@ufs.ac.za. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7854-162X

ABSTRACT

In today's dynamic business environment, every avenue that can contribute to fostering business performance has to be embraced. Interest in the contribution of communication to organisational effectiveness and performance has increased considerably in the last few decades. Despite positive claims made by advocates of adventure-based experiential learning programmes (AEL), the expansion of AEL into business schools and the corporate world necessitates ongoing empirical investigation. The aim of the study was to determine the developmental impact of a one-day programme on the communication competence of adult learners at a business school. The Communicative Adaptability Scale was administered as pre- and post-test measurement to adult learners with a permanent work appointment who enrolled for a qualification in management leadership in a business school at a university in South Africa. The overall post-test scores of the experimental group (n=140) were significantly higher (p=0.0001) than the post-test scores of the control group (n=126). The post-test scores of five dimensions differed significantly (p<0.05) from the post-test scores of the control group. The findings indicate the potential efficacy of an AEL course for the development of communication competence in adult learners. Ongoing research, directed at principles underlying the application of particular methodologies and other programmatic factors to maximise efficacy in reaching the desired outcomes of the interventions, is required.

Keywords: communication competence, adventure-based experiential learning, adult learning, business school, Communicative Adaptability Scale

INTRODUCTION

Interest in the impact of communication in the business environment has increased over the last few decades. It has been said that effective communication contributes to organisational effectiveness and performance (Montgomery 2023; Moreno 2010). In today's dynamic business environment, every avenue that can contribute to fostering efficiency and business performance must be embraced. Assisting individuals with improving their communication competency should therefore be a priority. It is assumed that when individuals improve their communication competency, it will contribute to improved business performance. Adventure-based experiential learning (AEL) programmes might create such an opportunity that could contribute to more effective communication.

Evidence is available in the literature that suggests the positive impact of AEL interventions (Carioppe & Adamson 1988; Bank 1994; Burke & Collins 1998; Neill et al. 2003; Gardner & Flood 2006). Wu et al. (2013) found that participation in ropes course experiences yielded intra- and interpersonal benefits to various target groups, while Bloemhoff (2016) indicated the potential efficacy of an AEL course for the development of life effectiveness skills in adult learners. Sceptics might be concerned that such claims are overzealous and that the effectiveness of AEL must be based on ongoing empirical investigations. Empirical evidence relating to the efficacy of AEL and the transfer of learning to adult learners in business schools specifically is still lacking.

Purpose of the study

Against the background of the importance of communication and the fact that literature on the study of interpersonal communication competence and leadership in the field of organisational behaviour and management is limited (Stigall 2005), and given the identified need for ongoing empirical investigations relating to the efficacy of AEL, the question was raised whether AEL could be used to contribute to the communication competence of adult learners in business schools. The aim of the study therefore was to determine the developmental impact of a one-day AEL programme (ropes course) on the communication competence of adult learners at a business school. These individuals were full-time employees in diverse corporate settings doing a part-time management course at a business school in South Africa. It was argued that if these learners were exposed to the one-day AEL programme, their communication competence would improve because of this experience.

COMMUNICATION COMPETENCE EXPLORED

One of the most common definitions of communication is that it entails "the process of creating meaning between two or more people" (Tubbs et al. 2011). By implication, if the communicators' intentions correspond with the receivers' reactions, the communication effort can be seen as effective. To be successful in communicating, communication competence is required (Obloberdiyevna 2023). Communication competence has been defined by Duran (1983: 320) as a "function of one's ability to adapt to differing social constraints". Çetin et al. (2012) described communication competence as the fundamental dynamics affecting the job satisfaction of employees, and therefore also the performance of an organisation. Friedrich (1994: 10) offered a comprehensive definition of communication competence in suggesting that it is best understood as a "situational ability to set realistic and appropriate goals and to maximize achievement by using knowledge of self, other, context, and communication theory to generate adaptive communication performances".

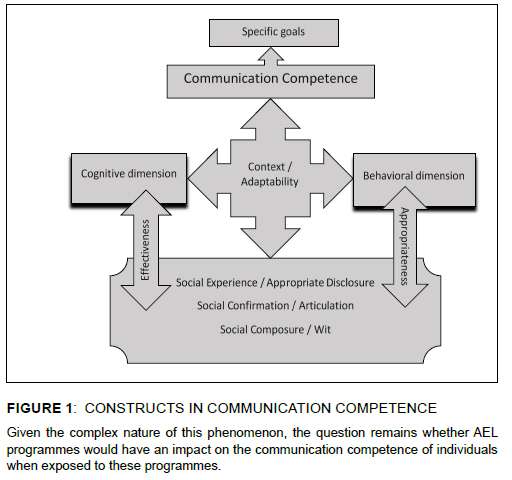

Adaptability is one of the essential characteristics that enable a person to interact more effectively with others. Groundbreaking research on communication adaptability, done in the 1980s by Duran (1983), is still relevant and widely cited in current research. A definition of communicative adaptability proposed by Duran (1983: 255) states that it entails "the ability to perceive socio-interpersonal relationships and adapt one's interaction goals and behaviours accordingly". Duran (1992) suggested that adaptability provides a repertoire (all the things a person can do) of behaviours that enables one to adjust to various communication contexts. Several salient aspects of communicative adaptability have been identified. According to Duran (1983), the requirement of cognitive (ability to perceive) and behavioural (ability to adapt) skills are essential in communication competence. This means that not only behaviour should be adapted, but also goals - emphasising the cognitive dimension of communication competence.

The requirements posed by different communication contexts should also be acknowledged and adapted. Communication context is often described as the setting and social-psychological climate within which communication takes place (Montgomery 2023; Tubbs et al. 2011). The context in which the communication takes place has a direct impact on the communication. Human communication occurs in various kinds of situations, which differ according to the number of people involved, the degree to which they can interact, and the context or setting in which communication takes place. Seven different contexts have been agreed upon in communication literature, namely intrapersonal, interpersonal, intercultural, small group, public, organisational, and mass communication (Tubbs et al. 2011). These authors (2011) asserted that while each context has unique characteristics, they share the process of creating meaning between two or more people. Managerial communication takes place in all the contexts mentioned, but more so on an interpersonal, small group and organisational level. In all these contexts, communication competence is required to enhance the sharing of meaning.

Spitzberg and Hecht (1984: 576) offered another view on communication competence, describing it as a "perceptual phenomenon", a "form of interpersonal influence in which an individual is faced with the task of fulfilling communicative functions and goals (effectiveness)". Spitzberg and Cupach (1981) suggested that conversational and interpersonal norms (appropriateness) must also be maintained. By implication, it is "the ability to interact well with others" (Spitzberg 1988: 68), where the term "well" refers to accuracy and clarity (effectiveness), but also comprehensibility, coherence, and expertise (appropriateness). Therefore, in addition to adaptability, appropriateness and effectiveness form the other central components of communication competence.

Against this background, behaviour, effectiveness, appropriateness, and cognitive abilities could all be considered important in communication competence. These constructs refer to the psychological processes involved in the acquisition and understanding of knowledge, the formation of beliefs and attitudes, and decision-making and problem-solving. The rules to competence in communication, established by Collier (1988), remain relevant today. These rules relate to the cognitive and behavioural dimensions of communication competence. They include politeness (being verbally courteous and using appropriate nonverbal styles), roles (the acknowledging thereof), content (staying relevant to the conversation topic), expressiveness (speaking assertively without violating another person's rights), relationship (feeling comfortable, showing trust), goals (gaining information and achieving personal goals), understanding (being appropriately empathic), self-validation (feeling good about the self), and cultural validation (feeling pride in one's own cultural identity). It seems that in most situations, displaying cognitive effectiveness and behavioural appropriateness (while being able to adapt to the contextual setting) will enhance the impression of competence that others have of a person.

More recently Montgomery (2023) describes communication competence as the skill of appearing in control of the course of one's communication behaviour. Morreale et al. (2007) support previously mentioned views by suggesting that behaviour that constitutes the skills of attentiveness, composure, coordination, and expressiveness is most likely to be viewed as competent and appropriate behaviour. Spitzberg (2006) described a skill as a repeatable, goal-oriented action sequence enacted in each context.

Against the established importance of adaptiveness in communication competence, it is important to determine which attributes can be adapted. Duran (1982) identified six areas of adaptability in social communication competence. These areas are social experience, social composure, social confirmation, appropriate disclosure, articulation, and wit. Social experience entails the awareness of these characteristics and measures an individual's desire and experience with communication, especially in novel social contexts (Duran 1982). The result of these experiences is the development and refinement of a social communication repertoire. Such a repertoire enables an individual to interact in various social contexts with different individuals. Social composure is a quality that is crucial to effective communication. When individuals bring composure into a chaotic situation, they can focus others on the bigger picture, create a sense of calm, and bring objectivity and perspective to the decision-making process (Courtney 2014). Battah (2015) described composure as follows: "In times of uncertainty we look to those who by instinct, learning or experience tend toward helping themselves and others ride out the storm." Lloppis (in Battah 2015) argued that there is much to be said about keeping your composure regardless of your role by "act(ing) like you have been there before" and always striving to deal with the situation with "elegance and grace".

Social confirmation or reinforcement is a skill employed in social interactions. It serves the purpose of encouraging another person to continue with a certain behaviour or activity (Hargie et al. 1994). This skill can be subdivided into verbal and non-verbal techniques; for example, verbal techniques include acknowledgements, praise and response development - which entails expanding upon and developing the response of the other person. Non-verbal techniques consist of gestural (smiles, head-nod, eye contact, gestures) and proxemics (posture, proximity, touch). Increasing competence regarding appropriate disclosure could have positive results. Self-disclosure is the purposeful disclosure of personal information to another person.

The Social Penetration Theory (Altman & Taylor 1973) explains the self-disclosure phenomenon and suggests that people engage in a reciprocal process of self-disclosure that changes in breadth and depth and affects how a relationship/communication progresses. Depth refers to how personal or sensitive the information is, and breadth refers to the range of topics discussed (Greene et al. 2006). Busby and Majors (1987) suggested five elements of disclosure that function as effective guidelines for determining how to disclose appropriately and effectively. These elements are the amount of information that is being communicated, the depth or intimacy of the information, the time needed, the person selected to receive the information, and the situation in which the disclosure is made. Appropriate disclosure thus refers to the aptness of the information shared in a specific communication context, while articulation suggests a methodological framework for understanding. Strategically, articulation provides a mechanism for shaping intervention within a particular social formation, conjuncture, or context (Slack in Morley & Chen 1996). Articulation is the expression (communication in speech or writing) of beliefs or opinions. Articulate people succeed because they get right to the point. They communicate their messages clearly and use few words (Stapleton 2015). The defining qualities of an articulate person is confidence in asking questions in conversations, unafraid of conflict, and assertive. They are clear on their roles and responsibility, not afraid of admitting gaps in their knowledge, break down problems into manageable tasks, their voice is calm, audible and engaging, and they use simple language that everybody can understand.

Since the 1970s, social behaviour specialists have suggested that humour may facilitate social influence (Goodchilds 1972). Henry Kissinger's use of humour to aid negotiation is well-known (McGhee 2010). He often made use of humour as a tool of diplomacy to create a relaxed atmosphere in private or formal discussions or negotiations with world leaders. According to the literature, the likeability of a communicator increases with the use of humour (Goodchilds 1972; Gruner in Hargie 2006). Bettinghaus and Cody (1987) added that the receivers of humorous messages are less critical and less resistant to persuasion. A study conducted by O'Quin and Aronoff (1981) established that humour could be used to influence others and suggested that humour may be a powerful agent of change in everyday life. The effective and appropriate use of humour or wit can therefore be seen as part of communication competence in social influence. A study by Taylor et al. (2022) on the importance of the use of humour in workplace communication highlights this notion. Against this background, Figure 1 below summarises the main constructs in communication competence.

Given the complex nature of this phenomenon, the question remains whether AEL programmes would have an impact on the communication competence of individuals when exposed to these programmes.

THE NATURE OF AEL PROGRAMMES

Adventure-based experiential learning (AEL) is based on the belief that changes will occur when people are taken out of their comfort zones into a state of disequilibrium (Bloemhoff 2016). The return to a state of equilibrium necessitates action (Priest & Gass 2005) that results in learning through their experience. Experiential learning (EL), one of the earliest forms of education in the Western world (Breunig 2008), is the strongest and most enduring of all learning theories using the elements of action, reflection, and transfer of learning (Beard & Wilson 2006). Kolb (1984) defined EL as the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience. Facilitators purposefully engage with clients to increase the transfer of knowledge, skills, and values. Active participation thus leads to different knowledge being gained as opposed to passive reception (Meyer 2003).

AEL is not a recent development (Hunt 1990) and has escalated in contemporary societies (Bloemhoff 2016). Adventure forms the basis of the experiential milieu and requires an element of real or perceived risk for the participant (Beard & Wilson 2006), which can have physical, mental, social, or financial consequences (Priest & Gass 2005). The expansion in the use of the outdoors as a vehicle for managerial learning (Burke & Collins 1998) and specifically leadership courses in business schools (Gangemi 2005) indicates that such experiential learning programmes have grown in importance.

METHODOLOGY

The methodology employed in this study entailed a quasi-experimental pre-test/post-test design. The study comprised an experimental and a control group. All groups completed the same questionnaire as a pre-test and again as a post-test.

Instrument

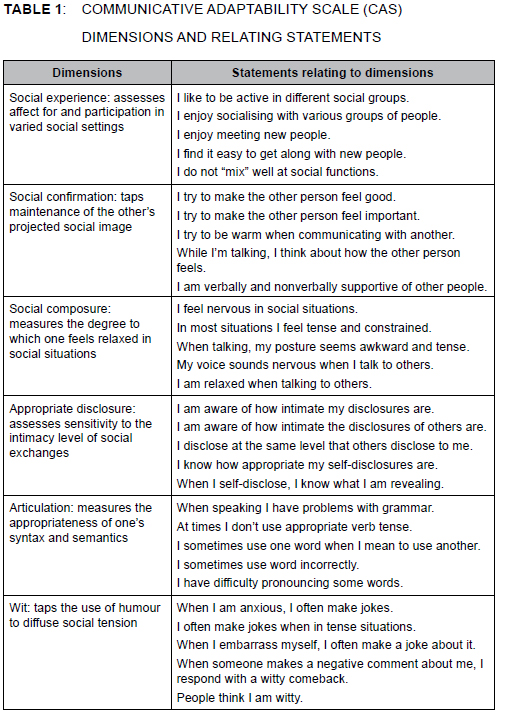

The research instrument used was the Communicative Adaptability Scale (CAS) developed by Duran (1983). The CAS is a dispositional (natural qualities of a person's character), molar-level measure of social communication competence. The choice of this scale is motivated against the background that "leadership is seen as a social process involving a relationship between individuals" (Çetin et al. 2012). This relationship is enacted through communication. The six dimensions and relating statements of the CAS are summarised in Table 1 below.

The average alpha reliabilities for the CAS dimensions based on ten samples are social experience .80; social confirmation .84; social composure .82; appropriate disclosure .76; articulation .80; and wit .74. (Duran 1992).

Participants

The sample population of this study constituted adult learners, at least 23 years of age, with a permanent work appointment enrolled for a qualification in management and leadership at a business school in South Africa. The objective of this particular qualification is to deliver a new generation of formally qualified and innovative managerial leaders equipped to excel in and add value, not only to today's corporate and business environment, but also to the public sector. After the necessary consent was obtained, all students who enrolled for this programme were recruited to participate in this research project. Respondents in their first year were randomly divided into a control (n=140) and experimental (n=126) group.

Experimental treatment

The traditional sequencing of a programme, as described by Rohnke (1989), was followed in this research project. This one-day ropes course programme included icebreakers, "deinhibitisers", trust/spotting, initiative challenges, and low and high ropes course elements. The elements required individual participants to perform tasks while receiving emotional support from the rest of the group. Group sizes varied between 15 and 20 participants per intervention, and it was a first-time experience for all the participants. The same programme was presented to all the respondents at the same venue. One of the authors, who has 20 years' experience in ropes course instruction and facilitation, acted as the head instructor and facilitator.

Statistical analysis

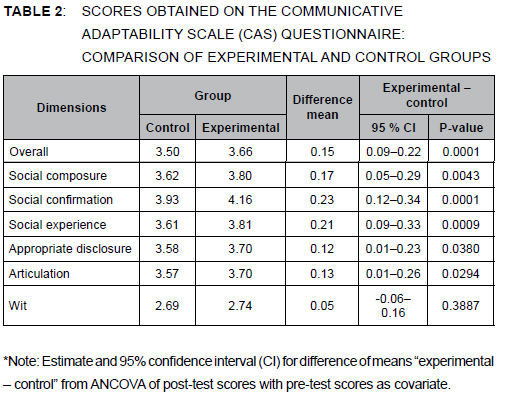

The data was analysed using the procedure MIXED of the SAS software system (SAS 2009). The overall score of the CAS questionnaire was calculated as the average of the six domain scores. Both the overall scores and the individual domain scores of each questionnaire were statistically analysed as follows: the post-scores of subjects in the experimental and control groups were compared using the analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) fitting the factor "group" (experimental/control) and the corresponding pre-score as covariate. From this ANCOVA model, estimates and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for the "experimental - control" difference in mean post-scores were obtained, as well as p-values associated with the null hypothesis of no difference between groups in post-scores.

RESULTS

The results of the ANCOVA are reported in Table 2 below. The overall post-test scores (that is, the average calculated from the six dimensions of communication) of the experimental group were significantly higher (p=0.0001) than the post-test scores of the control group. The post-test scores of five dimensions (social composure, social confirmation, social experience, appropriate disclosure, and articulation) differed significantly (p < 0.05) from the post-test scores of the control group. The post-test scores of the remaining dimension (wit) were not significantly higher than the post-test scores of the control group.

DISCUSSION

The significantly higher (p=0.0001) overall post-test scores of the experimental group demonstrates the positive impact of a one-day AEL programme (ropes course) on the communication competence of adult learners in a business school. From the results it could be concluded that the participants in the experimental group were significantly more willing to communicate and interact with different individuals in various social contexts after exposure to the AEL programme (social experience).

The participants in the experimental group also reflected significantly more confidence to approach a novel social setting and to engage in conversations as their composure (they measured as cool, calm, and collected) improved (social composure). The data also indicated that the participants' sense of perception (of self and the other person) improved, as they were more sensitive to/experienced the other person's perception (that is, seeing and feeling as the other does) (Tubbs et al. 2011) (social confirmation).

They also had a significantly more stable impression of themselves (what they have been, are, and aspire to be) (Pearson et al. 1995). Therefore, they were more likely to self-disclose within the constraints of the social context, as indicated by the other. The fact that they were more sensitive to the cues of others, aided them in establishing the appropriateness of their disclosures. According to Duran (1983), appropriate disclosure, like social confirmation, functions to provide information regarding how another person is presenting himself/herself and how the other is responding to the way the interaction is transpiring.

The participants displayed a significantly higher ability to clearly express their ideas in a manner that was considered appropriate to the social context (articulation). Although the literature established that humour/wit could be used effectively to diffuse social tension or to deal with anxiety that is often associated with novel social settings, this specific trait did improve, although not significantly, during exposure to the AEL programme.

The question can be posed regarding possible explanations on why five of the dimensions (social composure, social confirmation, social experience, appropriate disclosure, and articulation) changed significantly and one (wit) did not. This finding may be attributed to AEL programmes that vary regarding content and format. Gass (2008) suggested that transfer-of-learning is determined by programme design (appropriate learning activities) or by the teaching methodology. Sibthorp (2003) confirmed this view and maintained that programmatic factors are the best predictors of targeted outcomes. This necessitates research directed at the link between programme content and methodology, on the one hand, and programme outcomes, on the other (Ewert & McAvoy 2000; Holman & McAvoy 2005).

The possibility of various biases in these results is acknowledged. Artificially high post-intervention scores remain a measurement concern, especially in adventure programmes. Sibthorp (2003) identified the Hawthorne effect (the tendency of some individuals to change their behaviour due to the attention they are receiving from researchers rather than the manipulation of independent variables), demand characteristic (a subtle cue that makes participants aware of what the experimenter expects to find or how participants are expected to behave), social-desirability response bias (Nederhof 1985), and post-group euphoria (Marsh et al. 1986) as problems in the measurement of adventure programme outcomes.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

It can be argued that the conclusions are tenable despite the methodological limitations noted. The efficacy of AEL for the development of communication competence in adult learners in a business school is evident. The results of this study confirm the merit of the expansion of AEL programmes into management training and business schools, as well as the proliferation of AEL organisations worldwide. Bona fide interventions should deliver measurable and positive effects on clients, which necessitates ongoing research that prevents AEL from being based on perceived benefits and anecdotal evidence.

REFERENCES

Altman, I. & Taylor, D. 1973. Social penetration: The development of interpersonal relationships. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. [ Links ]

Bank, J. 1994. Outdoor development for managers. (Second edition). Aldershot: Gower. [ Links ]

Battah, P. 2015. Blog: World of work. Managing in times of uncertainty requires communication, composure. How senior leaders navigate uncertain times determines how organizations fare in difficult times. Available at: http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/new-brunswick/managing-in-times-of-uncertainty-requires-communication-composure-1.2897792 [Accessed on 7 April 2023]. [ Links ]

Beard, C. & Wilson, J.P. 2006. The power of experiential learning: A handbook for trainers and educators. Philadelphia, PA: Kogan Page. [ Links ]

Bettinghaus, E.P. & Cody, M.J. 1987. Persuasive communication. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. [ Links ]

Bloemhoff, H.J. 2016. Impact of one-day adventure-based experiential learning (AEL) programme on life effectiveness skills of adult learners. South African Journal for Research in Sport, Physical Education and Recreation 38(2): 27-35. [ Links ]

Breunig, M. 2008. The historical roots of experiential education. In: Warren, K., Mitten, D. & Loeffler, T.A. (eds). Theory and practice of experiential education. Boulder, CO: Association for Experiential Education. [ Links ]

Burke, V. & Collins, D. 1998. The great outdoors and management development: a framework for analysing the learning and transfer of management skills. Managing Leisure 3(3): 136-148. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/136067198376049 [ Links ]

Busby, R.E. & Majors, R.E. 1987. Basic speech communication: Principles and practices. New York: Harper & Row. [ Links ]

Carioppe, R. & Adamson, P. 1988. Stepping over the edge: outdoor development programmes for management and staff. Human Resource Management Australia 26(4): 77-95. DOI: 10.1177/103841118802600407. [ Links ]

Çetin, M., Karabay, M.E. & Efe, M.N. 2012. The effects of leadership styles and communication competency of bank managers on the employee's job satisfaction: The case of Turkish banks. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences 58: 227-235. DOI: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.09.996. [ Links ]

Collier, M.J. 1988. A comparison of conversations among and between domestic culture groups: How intra- and intercultural competencies vary. Communication Quarterly 36(2): 122-144. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01463378809369714 [ Links ]

Courtney, M. 2014. The Bates Blog. Calm, cool and collected: Why composure is an overlooked facet of executive presence. Available at: http://www.bates-communications.com/bates-blog/bid/107098/Calm-Cool-and-Collected-Why-Composure-is-an-Overlooked-Facet-of-Executive-Presence [Accessed on 20 June 2021]. [ Links ]

Duran, R.L. 1983. Communicative adaptability: A measure of social communicative competence. Communication Quarterly 31(4): 320-326. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01463378309369521 [ Links ]

Duran, R.L. 1992. Communicative adaptability: A review of conceptualization and measurement. Communication Quarterly 40(3): 253-268. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01463379209369840 [ Links ]

Ewert, A. & McAvoy, L. 2000. The effects of wilderness setting on organized groups: a state of knowledge paper. In: McCool, S.F., Cole, D.N., Borrie, W.T. & O'Loughlin, J. (eds). Wilderness as a place for scientific inquiry. USDA Forest Service Proceedings. (RMRS) 15(3):13-26. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture. Available at: www.wilderness.net/library/documents/Ewert_McAvoy_3-x.pdf [Accessed on 18 August 2023]. [ Links ]

Friedrich, G. 1994. Strategic communication in businesses and other professions. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. [ Links ]

Gangemi, J. 2005. Trekking to the top. Business News. Available at: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2005-02-27/trekking-to-the-top [Accessed on 20 June 2021]. [ Links ]

Gardner, E. & Flood, J. 2006. The impact of a one-day challenge course experience on the life effectiveness skills of college students. Proceedings and Research Symposium Abstracts of the 20th Association of Outdoor Recreation and Education Conference. Available at: http://connection.ebscohost.com/c/articles/35749523/impact-one-day-challenge-course-experience-life-effectiveness-skills-college-students [Accessed on 18 August 2021]. [ Links ]

Gass, A.L. 2008. Programming the transfer of learning in adventure education. In: Warren, K., Mitten, D. & Loeffler, T.A. (eds). Theory and practice of experiential education. Boulder, CO: Association for Experiential Education. [ Links ]

Goodchilds, J.D. 1972. On being witty: Causes, correlates and consequences. In: Goldstein, J. & McGhee, P. (eds). The psychology of humor. New York: Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-288950-9.50015-8 [ Links ]

Greene, K., Derlega, V.J. & Mathews, A. 2006. Self-disclosure in personal relationships. In: Vangelisti, A.L. & Perlman, D. (eds). The Cambridge handbook of personal relationships. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511606632.023 [ Links ]

Hargie, O. 2006. Handbook of communication skills. New York: Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203007037 [ Links ]

Hargie, O., Saunders, C. & Dickson, D. 1994. Social skills in interpersonal communication. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Holman, T. & McAvoy, L.H. 2005. Transferring benefits of participation in an integrated wilderness adventure program to daily life. Journal of Experiential Education 27(3): 322-325. https://doi.org/10.1177/105382590502700316 [ Links ]

Hunt, J.S. 1990. Philosophy of adventure education. In: Miles, J.C. & Priest, S. (eds). Adventure education. State College, PA: Venture Publishing. [ Links ]

Kolb, D.A. 1984. Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

Marsh, H.W., Richards, G.E. & Barnes, J. 1986. Multidimensional self-concepts: A long-term follow-up of the effect of participation in an Outward-Bound program. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 12(4): 475-492. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0146167286124011 [ Links ]

McGhee, P. 2010. Humor as survival training for a stressed-out world: The 7 humor habits program. Bloomington, Indiana: Author House. [ Links ]

Meyer, J.P. 2003. Four territories of experience: A developmental action inquiry approach to outdoor-adventure experiential learning. Academy of Management Learning and Education 2(4): 352-363. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/AMLE.2003.11901956 [ Links ]

Montgomery, K. 2023. How highly successful people & leaders communicate: Harnessing the power of effective communication and influence. Independently published. [ Links ]

Moreno, C.M. 2010. An approach to ethical communication from the point of view of management responsibilities. The importance of communication in organisations. Ramon LLull Journal of Applied Ethics 1(1): 97-100. Available at: http://www.raco.cat/index.php/rljae/article/view/270549 [Accessed on 18 August 2020]. [ Links ]

Morley, D. & Chen, K.H. 1996. Critical dialogue in cultural studies. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Morreale, S.P., Spitzberg, B.H. & Barge, J.K. 2007. Human communication: Motivation, knowledge and skills. Belmont, CA: Thompson Wadsworth. [ Links ]

Nederhof, A.J. 1985. Methods of coping with social desirability bias: A review. European Journal of Social Psychology 15(3): 263-280. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420150303 [ Links ]

Neill, J.T., Marsh, H.W. & Richards, G.E. 2003. The Life Effectiveness Questionnaire: development and psychometrics. Sydney: Department of Education, University of Western Sydney. [ Links ]

Obloberdiyevna, D.S. 2023. Place and significance of emotional and communicative competence in the work of a physician. Journal of Healthcare and Life-Science Research 2(4): 14-17. [ Links ]

O'Quin, K. & Aronoff, J. 1981. Humor as technique of social influence. Social Psychology Quarterly, 44(4): 349-357. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3033903 [ Links ]

Pearson, J.C., Turner, L.H. & Todd-Mancillas, W. 1995. Gender and communication. Dubuque, IA: Benchmark Brown. [ Links ]

Priest, S. & Gass, M.A. 2005. Effective leadership in adventure programming. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. [ Links ]

Rohnke, D. 1989. Cowstails and cobras II: a guide to games, initiatives, ropes courses, and adventure curriculum. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt. [ Links ]

SAS Institute Inc. 2009. SAS/STAT 9.2 User's guide. (Second edition). Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc. [ Links ]

Sibthorp, J. 2003. An empirical look at Walsh and Golins' Adventure Education Process Model: Relationships between antecedent factors, perceptions of characteristics of an adventure education experience, and changes in self-efficacy. Journal of Leisure Research 35(1): 80-106. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18666/JLR-2003-V35-I1-611 [ Links ]

Spitzberg, B.H. 1988. Communication competence: Measures of perceived effectiveness. In: Tardy, C.H. (ed.). A handbook for the study of human communication: Methods and instruments for observing, measuring, and assessing communication processes. Westport: Ablex. [ Links ]

Spitzberg, B.H. 2006. CSRS. The Conversational Skills Rating Scale. An instructional assessment of interpersonal competence. NCA Diagnostic Series. Available at: https://www.natcom.org/uploadedFiles/Teaching_and_Learning/Assessment_Resources/PDF-Conversation_Skills_Rating_Scale_2ndEd.pdf [Accessed on 18 August 2020]. [ Links ]

Spitzberg, B.H. & Cupach, W.R. 1981. Self-monitoring and relational competence. Paper presented at the Speech Communication Association Convention, Anaheim, CA. [ Links ]

Spitzberg, B.H. & Hecht, M.L. 1984. A component model of relational competence. Human Communication Research 10(4): 575-599. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.1984.tb00033.x [ Links ]

Stapleton, S. 2015. Why being articulate is an essential business skill. Available at: http://www.simonstapleton.com/wordpress/2012/11/19/why-being-articulate-is-an-essential-business-skill/ [Accessed on 18 August 2020]. [ Links ]

Stigall, D.J. 2005. A vision for a theory of competent leader communication: The impact of perceived leader communication behaviours on emergent leadership and relational and performance outcomes in collaborative groups. Unpublished doctoral thesis. Lexington: University of Kentucky. [ Links ]

Tubbs, S., Moss, S. & Papastefanou, N. 2011. Human communication: principles and contexts. London: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Taylor, S., Simpson, J. & Hardy, C. 2022. The use of humor in employee-to-employee workplace communication: A systematic review with thematic synthesis. International Journal of Business Communication 1(25). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/23294884211069966 [ Links ]

Wu, C.C., Hsieh, C.M. & Wang, W.C. 2013. Possible mechanisms of the benefit of one-day challenge ropes courses. South African Journal for Research in Sport, Physical Education and Recreation, 35(1): 219-231. [ Links ]

Date submitted: 21 September 2023

Date accepted: 9 October 2023

Date published: 15 December 2023