Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Communitas

versión On-line ISSN 2415-0525

versión impresa ISSN 1023-0556

Communitas (Bloemfontein. Online) vol.28 Bloemfontein 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.38140/com.v28i.6981

ARTICLES

The role of strategic multi-stakeholder partnerships in reducing food loss and waste in South Africa

Dr Olebogeng SelebiI; Criska SlabbertII; Elizma van NiekerkIII

IDepartment of Business Management, University of Pretoria, South Africa. Email: olebogeng.selebi@up.ac.za (corresponding author). ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9934-8538

IIDepartment of Business Management, University of Pretoria, South Africa. Email: criskaslabbert0712@gmail.com. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6917-7985

IIIDepartment of Business Management, University of Pretoria, South Africa. Email: hello@elizmavn.co.za. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3992-0886

ABSTRACT

Food loss and waste is a wicked problem (a problem with no single solution). This problem is addressed by Sustainable Development Goal 12. Solving this wicked problem in South Africa requires the collaboration of a variety of stakeholders, all with their own organisational interests. Therefore, multi-stakeholder partnerships (MSP) are imperative to the achievement of SDG 12.3, which focuses on the reduction of food waste. This qualitative case study unpacks the necessity for the use of multi-stakeholder partnerships (SDG 17) in achieving SDG 12.3. The South African Food Loss and Waste Voluntary Agreement (SAFLWVA) is the multi-stakeholder partnership being studied in this article. MSPs cannot be effective without strategic communication. Therefore, the barriers and enablers of strategic communication within a multi-stakeholder partnership of this nature are explored. The study was conducted in South Africa with stakeholders involved with the SAFLWVA. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 15 participants. The findings indicate that strategic communication is one of the pillars of a successful MSP. Additionally, the following enablers for successful communication in MSPs were identified: trust, information sharing, education about benefits, receiving value, and gaining ownership. The study contributes to the understanding of communication barriers and enablers within MSPs.

Keywords: multi-stakeholder partnerships, strategic communication, SDG 12.3, food loss and waste, Sustainable Development Goals, South African Food Loss and Waste Voluntary Agreement

INTRODUCTION

A third of South Africa's available food is wasted, amounting to approximately ten million tonnes of food waste yearly (CGCSA 2019: 18; WWF 2017: 8). This is a worldwide challenge that is being addressed as part of the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 12 to reduce 50 percent of food loss and waste by 2030 (FAO 2020a). Food loss and waste is an example of a wicked problem (Thornsbury & Minor 2019: 55), which is characterised as a problem that has no single cause or solution (Dentoni et al. 2018: 336; Thornsbury & Minor 2019: 55). The Consumer Goods Council of South Africa (CGCSA) initiated the implementation of a multi-stakeholder partnership (MSP) - the South African Food Loss and Waste Voluntary Agreement (SAFLWVA). Their approach is focused on the formation of a strategic MSP consisting of various stakeholder groups such as the government, industry, academia, and civil society (CGCSA 2019: 20-24).

Sloan and Oliver (2013: 1837) define MSPs as formal agreements between various stakeholders mainly from the private, public, and non-profit sector. Having all the stakeholders contribute their resources and capabilities to an MSP ensures that a common goal is achieved more effectively than in their individual capacity (Brouwer et al. 2016a: 20-22; Sloan & Oliver 2013: 1837). In line with this, the 17 SDGs are interconnected and all equally important (FAO 2020a). SDG target 12.3 focuses on the reduction of food loss and waste across the entire food supply chain - from farm to fork levels (United Nations 2020). For MSPs to achieve SDG 12.3 targets, good communication is necessary (Lindén & Carlsson-Kanyama 2002: 897). MSPs are at risk of failure without effective communication on the expectations of each stakeholder, as well as their roles and responsibilities (Brouwer et al. 2016a: 20-22; Brouwer et al. 2016b: 9-11).

The SAFLWVA is the first voluntary agreement to be signed in South Africa to reduce food loss and waste. Limited studies have been conducted on food waste in South Africa (Nahman et al. 2012: 2147-2149). The purpose of a voluntary agreement is to be a policy instrument with which an issue can be tackled by applying new technology, knowledge, or routines (Lindén & Carlsson-Kanyama 2002: 897). Additionally, there is a lack of research on the communication barriers and enablers in an MSP, in the form of a voluntary agreement (CGCSA 2020). This study, therefore, fills the gap in the academic literature and provides insight into the creation of a communication framework for the SAFLWVA and similar MSPs.

This study focused on the communication between the stakeholders of the SAFLWVA voluntary agreement, targeting the core signatories - private sector, the government and NGOs/NPOs. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 15 participants to investigate the communication enablers and barriers faced in the process leading up to the establishment of the voluntary agreement.

The following research questions guided the study:

1. Why is understanding multi-stakeholder partnerships necessary for the success of SAFLWVA?

2. How do the stakeholders communicate within the SAFLWVA MSP?

3. What are the communication enablers and barriers within the SAFLWVA?

The intended academic contribution of this study is threefold. Firstly, this study contributes to the academic literature by offering insight into possible communication barriers and enablers in MSPs. As MSPs are becoming more relevant in today's world to solve wicked problems (Dentoni et al. 2018: 333-356), it will be valuable and serve as a starting point for future research. Secondly, this study explores an MSP that takes the form of a voluntary agreement. This will provide academic literature for future studies on both voluntary agreements and MSPs. Lastly, this study contributes to the academic conversation on the role of strategic communication in the success of MSPs by looking at the barriers and enablers of communication in this context.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Global, continental, and local perspectives on food loss and waste

In 2015, the United Nations set 17 goals to be achieved in the next 15 years to make the world a better place for everyone. This includes addressing food loss and waste (United Nations 2020). The 17 Sustainable Development Goals set out by the United Nations are the "blueprint to achieve a better and more sustainable future for all" (FAO 2020a). The goals are all interconnected and should be achieved by 2030, according to the agreed UN Agenda (FAO 2020a). SDG 12 is aimed at sustainable consumption and production, stating the goal to "by 2030, halve per capita global food waste at the retail and consumer levels and reduce food losses along production and supply chains, including post-harvest losses" (United Nations 2019).

SDG target 12.3 seeks to reduce (United Nations 2020):

♦ food losses that occur from production up to (but not including) the retail level, and

♦ food waste, which comprises the retail and consumption levels.

SDG 17 seeks to strengthen global partnerships to support and achieve the ambitious targets of the 2030 Agenda, bringing together national governments, the international community, civil society, the private sector, and other actors at all levels (international, national, regional, and local) to create partnerships to be able to achieve the targets set out in the other 16 SDGs (FAO 2020b).

The complexity of the issues of food waste and loss (SDG 12.3) today requires the involvement of government, as well as local businesses, non-governmental organisations, and citizens. The involvement of all these parties is best done through an MSP (MacDonald et al. 2018).

Research has shown that globally around a third of all food produced for human consumption is lost or wasted at some point in the value chain (CGCSA 2019: 18; WWF 2017: 8). Despite the amount of food being produced worldwide increasing, there are still approximately one in nine people who do not have daily food to eat (Shafiee-Jood & Cai 2016: 8432). An estimated 1.3 billion tonnes of the edible parts of food are not utilised, forming part of food loss and waste annually (Shafiee-Jood & Cai 2016: 8433). This results in more pressure on the planet's agricultural system to produce increased amounts of food to account for the loss, while producing enough food for human survival (Lipinski et al. 2013: 4-7; Secondi et al. 2015: 25).

It is estimated that 30 to 40 percent of food loss occurs in developing countries (Irfanoglu et al. 2014: 2; Sheahan & Barrett 2017: 3). In Sub-Saharan Africa, the food waste and loss estimate is estimated at 37 percent (Sheahan & Barrett 2017: 3). This figure, however, is not completely accurate as there is no agreed-upon standard method of measurement to record food loss and waste (Sheahan & Barrett 2017: 3; Thornsbury & Minor 2019: 55-57). In South Africa, food losses are estimated to be around 50 percent of all food produced for consumption throughout the entire supply chain process (Nahman et al. 2012: 2147). This accounts for at least ten million tonnes of food loss and waste annually (CGCSA 2019: 18; WWF 2017: 8).

"Food loss and waste refers to the edible parts of plants and animals that are produced or harvested for human consumption but that are not ultimately consumed by people" (Lipinski et al. 2013: 1). This refers to food that spoils or reduces in quality before it reaches the end-consumer as part of the supply chain process (Lipinski et al. 2013: 1; Nahman et al. 2012: 2147). This is due to carelessness or consciously discarding food (Lipinski et al. 2013: 1). The impact of food loss and waste emphasises why it can be considered a wicked problem that requires MSPs to solve it (Lipinski et al. 2013: 2; Nahman et al. 2012: 2148-2149; Secondi et al. 2015: 25; Thornsbury & Minor 2019: 55). It is also important to consider that each stakeholder within an MSP seeks to approach the solutions to the reduction of food loss and waste differently (Dentoni et al. 2018: 336-338; Thornsbury & Minor 2019: 55). The SDGs are interconnected and no one goal can be seen as superior to another, making the SDGs unique and allowing organisations to better identify areas in which they can make a difference or join an MSP to make a societal impact (Murray 2018).

Voluntary agreements as a tool to reduce food waste

Lindén and Carlsson-Kanyama (2002: 897) describe voluntary agreements as a communication process between stakeholders who are mutually dependent and have a common goal. The purpose of a voluntary agreement is to be a policy instrument, which can address an issue by applying new technology, knowledge, or routines (ibid.). As stated above, food loss and waste can be defined as a wicked problem as various stakeholders can each envision a different solution to the problem. Therefore, a voluntary agreement can be a useful tool for addressing food loss and waste. It allows all stakeholders to participate in the solution whilst an independent entity is in control (Lindén & Carlsson-Kanyama 2002: 897; Thornsbury & Minor 2019: 55). Baggot (1986) states that a voluntary agreement is "any agreement between the government (or one of its agencies) and a section of the community (or its representatives) whose main purpose is to establish a degree of regulation over the specific activities of the latter, and which involves a non-statutory regulatory procedure or code of practice, or both, which the latter is committed to following under the terms of the agreement".

Currently, there are food loss and waste voluntary agreements both in the pilot and implementation phases worldwide. Numerous countries have published research on voluntary agreements and their success (Refresh 2018b: 1-6). Reviewing these voluntary agreements across the globe provides insight into the use of these MSPs for the achievement of the SDGs. Several countries have prioritised socioeconomic development through MSPs between leading universities, research institutes, private businesses, governments, civil society, and other actors and stakeholders (Refresh 2018b: 1-6).

The Netherlands is one of the countries in the European Union (EU) where the voluntary agreement has progressed well into the implementation phase. The success of this voluntary agreement has been so significant that the Netherlands is seen as a leader in achieving SDG 12.3 (Refresh 2018b: 1-6). The United Kingdom is also a leading country in achieving SDG 12.3 as its voluntary agreement has been active since 2005. Food waste was reduced by 2.3 million tonnes in 2013. This testifies to the fact that an MSP formalised in a voluntary agreement can achieve significant success (Priefer et al. 2016: 159). China has set up a five-year plan to achieve the SDGs. The China Chain Store and Franchise Association (CCFA) proposed that a voluntary action plan should be formulated (Refresh 2018a: 18). The voluntary action plan would be called The Food Waste Reduction China Action Platform. This action plan flows form an international MSP with IVL Swedish Environmental Research Institute, CCFA and CHEARI, guided by FAO, UNEP 'Think, Eat, Save', and supported by REFRESH, in the aim of supporting China to achieve SDG 12.3 (Refresh 2018a: 18).

In Kenya, between 30 and 40 percent of food is being lost and wasted. This amounts to more than 50 million bags of food (Kimiywe 2015: 489). Most of these losses happen post-harvest due to the lack of infrastructure for farmers to transport all the produce to communities (Kimiywe 2015: 490). To address this, the government has been encouraged to partner with farmers and NGOs to reduce food loss and waste. Proposals have been drafted on systems that will assist with reducing post-harvest loss through infrastructure changes (Affognon et al. 2015: 491-493; Kimiywe 2015: 50-64).

Currently, plans are in progress among South African food manufacturers, suppliers, and retailers to commit, via a voluntary agreement, to reduce food waste and loss (CGCSA 2020). Three main stakeholder groups will be stakeholders in this voluntary agreement - the government, the private sector, and NGOs. This MSP was launched at a three-day meeting from 1 to 3 April 2019, hosted by the Consumer Goods Council of South Africa (CGCSA) in partnership with the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI), and funded by the European Union (SA-EU Dialogue Facility) (CGCSA 2020). This first stakeholder meeting focused on the first step of understanding food loss and waste and to develop a deeper understanding of why and where this loss and waste occurs in the markets and industries, in line with the research done by Thornsbury and Minor (2019: 55). A series of further workshops were held to facilitate a deeper understanding of food waste and loss among stakeholders and to investigate collaborative options to address this wicked problem.

Currently, in South Africa, no formalised food waste voluntary agreement has been implemented (CGCSA 2019). "In a country where millions of people go to bed hungry daily, this is monumental waste which we cannot allow to continue," said CGCSA Executive Matlou Setati (CGCSA 2020). South Africa's situation is like that of Hungary in terms of the lack of information available regarding the measurement and reporting of food waste (Nahman et al. 2012: 2148; Refresh 2018b: 1-6). Limited studies have also been conducted on the analysis of the food waste streams in South Africa (Nahman et al. 2012: 2147-2149). This raises the need for a food waste voluntary agreement between all stakeholders involved in the food supply chain. Voluntary agreements help various stakeholders to collaborate more effectively and to understand the drivers of food loss and waste in their supply chain (Thornsbury & Minor 2019: 56).

Communication within MSPs

An MSP can be defined as a formal agreement between various stakeholders from the private, public, and non-profit sectors (Sloan & Oliver 2013: 1837). Voluntary agreements are a form of MSP. The core of MSPs is based on having a shared goal to solve a problem that none of the stakeholders can solve in their individual capacity. This is the key driving force that encourages stakeholders to work collaboratively (Brouwer et al. 2016a: 20-22; Sloan & Oliver 2013: 1837). Any successful MSP must provide and ensure benefits for all stakeholders involved. While all stakeholders will benefit from the partnership, they will also have to contribute their expertise and resources to ensure partnership success. Knowledge-sharing is a key characteristic of an MSP (Beisheim & Simon 2016: 3; Brouwer et al. 2016a: 20-22).

Brouwer et al. (2016a: 44-46) set out various principles that will ensure an MSP is effective. At the foundation of these principles lies the importance of communication between partners. It can be argued that this is the foundation and that there would be no partnership without constructive dialogue with one another to reach a common end goal (Brouwer et al. 2016b: 9-11). Communication is necessary to set out the expectations of all partners, and to determine leadership, and to delegate roles and responsibilities. If these factors are not communicated clearly, the MSP will not be able to function effectively, leading to unmet expectations. It is of critical importance that all stakeholders should be actively involved in the communication process (Brouwer et al. 2016a: 20-22; Brouwer et al. 2016b: 9-11). This communicative collaboration facilitates transformative change, which is a key requirement to successfully address the wicked problems set out in the SDGs (Brouwer et al. 2016a: 20-22; Brouwer et al. 2016b: 9-11).

For an MSP to be successful, all stakeholders must be equally willing to share information and power. There should be an equal level of commitment from the stakeholders. This will contribute to the success of the MSP as everyone will focus on meeting the joint goal to the best of their individual abilities (Brouwer et al. 2016a: 18-19; Mohr & Spekman 1994: 137-138). Therefore, having effective communication is key to an MSP's success (Brouwer et al. 2016a: 18-19; Mohr & Spekman 1994: 137-138).

In an MSP (such as a voluntary agreement), certain stakeholders may have more institutional power than others. For stakeholders to communicate effectively within an MSP, interdependence must be established to ensure each stakeholder is of equal importance and value to the partnership. This will also create an equal level of respect amongst the stakeholders. Without respect, there will not be free and open communication (Brouwer et al. 2016a: 18-19; Mohr & Spekman 1994: 137-138).

Establishing mutual respect amongst the stakeholders is a key factor in creating an environment of trust. Stakeholders will be more inclined to share information when trust is established. This will lead to stakeholders communicating more openly to collectively reach the joint goals of the partnership (Brouwer et al. 2016a: 18-19; Mohr & Spekman 1994: 137-138). As South Africa is a diverse country, all stakeholders will be from different cultures and religions, and this might affect the way in which a stakeholder communicates with other stakeholders or how communication is received from other stakeholders (Kapur 2018: 4).

The cultural diversity of South Africa is reflected in the country's 12 official languages. This could create a semantic barrier of misunderstanding among stakeholders when different languages are used for communication. As all stakeholders are also from various sectors and industries, the sectoral and industry jargon used might also create communication barriers among stakeholders (Kapur 2018: 5).

RESEARCH DESIGN

Methodology

This study used a single qualitative case study research design. The purpose of a single case study research design is to describe and interpret the phenomenon being studied in a real-world context (Du Plooy-Cilliers et al. 2014: 178-179; University of Pretoria 2019: 2). This requires an extensive study of one or more space-and time-bound events (University of Pretoria 2019: 2). Case studies in business usually involve an investigation of the functioning of some aspect of the organisation (Myers 2013: 78). For this study, the researchers worked with the CGCSA to describe and understand the communication within the MSP of the SAFLWVA towards the achievement of SDG 12.3. A single case study research design was most suited to this study as the researchers were focusing on the topic of communication barriers and enablers within the MSP of the voluntary agreement to achieve SDG 12.3.

Sampling

The unit of analysis consisted of representatives from the signatory organisations from three sectors - the government, the private sector, and NGOs - that are part of the SAFLWVA. The units of observation were 15 individuals representing each organisation interviewed.

The purposive technique was used to select the organisations and individual participants who were deemed to be information-rich with regards to the study's research questions. The organisations and participants were carefully chosen based on specific inclusion and exclusion characteristics. Additionally, snowball sampling allowed for participants to refer other individuals or organisations who were also relevant to the study. These information-rich interviews gave deeper insights and a clear understanding of the phenomenon (Du Plooy-Cilliers et al. 2014: 142-143; Palinkas et al. 2015: 1).

Inclusion criteria for individual participants:

♦ Individual must have been employed by an organisation which is a stakeholder or potential signatory of the SAFLWVA;

♦ Individual must be actively involved in the organisation's participation in the voluntary agreement; and

♦ Individual must have been residing in South Africa.

Data collection

One-on-one semi-structed interviews took place via online video calls. The online semi-structured interviews used open-ended questions that allowed the participants more flexibility to answer the questions freely and without the interviewer's bias (Creswell 2012: 218). A discussion guide was created. The researchers started the interview with introductions and consent before heading into the interview questions. The discussion guide allowed for the researchers to use probing questions encouraging the respondents to give detailed responses.

A pre-test was conducted on two individuals participating in the SAFLWVA. The pre-test was used to improve the discussion guide to ensure optimal results in the data collection (Du Plooy-Cilliers et al. 2014: 15).

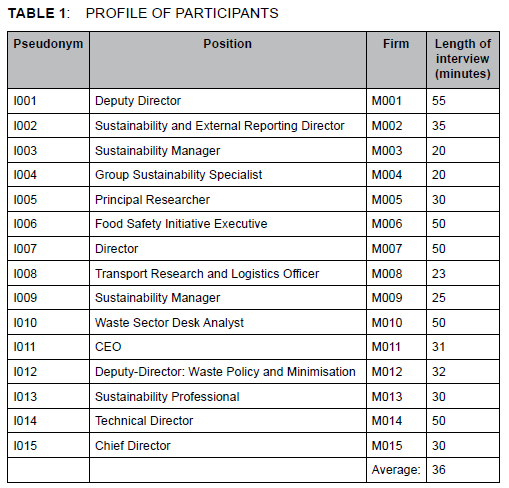

Data collection took place from September to October 2020, with a total of 15 semi-structured online interviews conducted. Table 1 provides a breakdown of the 15 interviews, each lasting an average of 36 minutes. All the interviews were conducted virtually using the Google Meet and Zoom online platforms. All participants granted their consent for the interviews to be recorded.

An auto-transcription tool, Fireflies.ai, was utilised for transcribing the interviews. Each transcription was available within an hour after completing the interview. The researchers downloaded the transcriptions immediately after the interviews and edited any errors made by the transcription tool.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis was used to analyse the data. The readings of Braun and Clarke (2012: 57-71) and Creswell (2012: 236-253) were used as guidelines to conduct the thematic analysis. This process involved preliminary studying of all the transcripts in-depth to develop a master code list from which the relevant sub-themes and themes were derived. The codes identified were used to analyse and codify all the transcriptions.

Ethical considerations

The Research Ethics Committee of the Department of Business Management at the University of Pretoria approved the study in August 2020. All participants were encouraged to read and sign an informed consent form before participating in an interview. The form clarified the intent of the study, and emphasised that participation in the research was voluntary and that a respondent could cease to participate at any point in time. This form guaranteed the anonymity and confidentiality of the information provided during the interviews. This information was reiterated before the audio recording of the interview commenced. The anonymity of all the participants was further protected by providing pseudonyms for all of them and by removing any identifying information from the transcripts. No organisation or individual participant's information is identifiable in the final research article.

FINDINGS

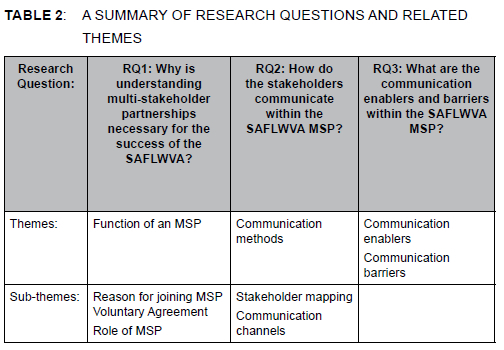

Four main themes were identified in the findings. Table 2 illustrate how the main themes and their sub-themes link to the research questions.

Table 2 was adapted from Mostert et al. (2017: 8) and provides an effective way to illustrate the links between the research questions and the themes identified. In the following sections each of the themes and sub-themes will be discussed in more detail with a relevant quotation from the data.

Theme 1: Function of an MSP

The first identified theme, function of an MSP, relates to the first research question about the role (purpose) of an MSP in reducing food waste. An MSP is seen as a vehicle to involve all the stakeholders to work together to tackle the issue of food waste and loss. This is illustrated by the following quote:

It's throughout the supply chain and therefore making one or getting one part in the value chain on board will not have as much effect as having different partners from the entire value chain to come on board. That is why it is important to have a multi-stakeholder involvement in this process (I005, Principal Researcher)

This links back to previous literature. Food loss and waste is seen as a complex problem that cannot be solved without the collaboration of various stakeholders (Lipinski et al. 2013: 2; Nahman et al. 2012: 2148-2149; Secondi et al. 2015: 25; Thornsbury & Minor 2019: 55).

Sub-theme 1: Reason for joining voluntary agreement

MSPs are necessary to solve the issue of food loss and waste. The first sub-theme emphasises the importance of understanding the reasons why stakeholders would join an MSP. Each stakeholder also must understand the importance and relevance of joining the voluntary agreement. This should be clearly communicated.

The findings illustrate that an organisation will join an MSP on the following pre-conditions: (1) there should be strategic alignment with the voluntary agreement's goals and the organisation's goals; and (2) there must mutual benefits. The following quotes illustrate this:

...I think at the moment, what would be important to us that a voluntary agreement is within our scope and our mission as an organisation... (I011, CEO)

...then mutual benefit probably for all the partners (I003, Sustainability Manager)

Understanding the reasons why a stakeholder joins will assist in understanding how to best communicate with stakeholders and can set the tone for the communication and indicate the frequency and possible vehicles that could be utilised.

Sub-theme 2: Understanding the purpose of MSPs

The findings indicate that an MSP allows for stakeholders, who would otherwise not have come together, to share their skills and knowledge for a mutually beneficial purpose. Such a partnership also creates a support network that serves all stakeholders in the form of information and knowledge-sharing. The following quote summarises this:

I think once stakeholders agree to achieve the objective, I think what becomes relevant then is to build an efficient system to achieve that objective. I think the natural progression should be that these stakeholders then would engage with each other and, collaborate with each other in order to achieve the objective (I012, Deputy-Director: Waste Policy and Minimisation)

Theme 2: Communication methods

This theme explores how the stakeholders should communicate with each other within an MSP.

Sub-theme 1: Stakeholder mapping

Understanding the audience is imperative to effective communication. An MSP consists of various stakeholders. In the SAFLWVA, there are stakeholders ranging from large corporates to smallholding farms. This makes it essential to conduct stakeholder mapping, as only one method of communication will not align with all stakeholders. The quotes below explain the relevance of stakeholder mapping:

...the farmers ... in Cape Town, they are very old school and conservative, and the only reason why they will ever change is if the neighbour changes. if you go speak to them face to face.... [Farmers] Does not talk, or send emails, honours. They actually go out and to meet them... (010, Waste Sector Desk Analyst)

i think that we have to be very selective and sensitive about what communication platforms and methods we use (I011, CEO)

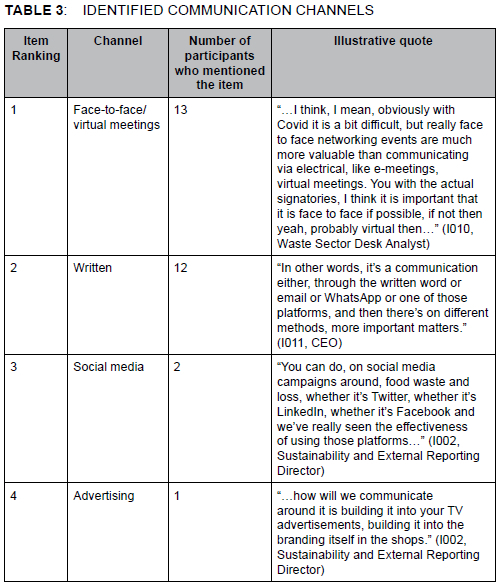

Sub-theme 2: Identifying communication channels

Following from the previous sub-theme, it is important to determine the channels of communication perceived to be most effective. The four most prominent communication channels mentioned by the participants are indicated in Table 3.

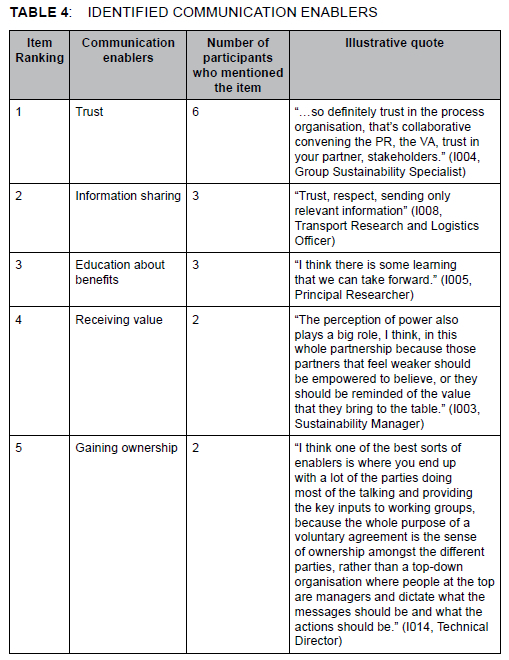

Theme 3: Communication enablers

The third theme relates to the communication enablers that are perceived to improve communication within the SAFLWVA. Table 4 lists the communication enablers necessary for a successful MSP.

The literature identified openness and closure as communication enablers (Radovic Markovic & Salamzadeh 2018; Stacho et al. 2019). The research findings have contributed these five additional enablers: (1) trust; (2) information sharing; (3) education about benefits; (4) receiving value; and (5) gaining ownership, which will enhance effective communication within the MSP of the SAFLWVA.

Theme 4: Communication barriers

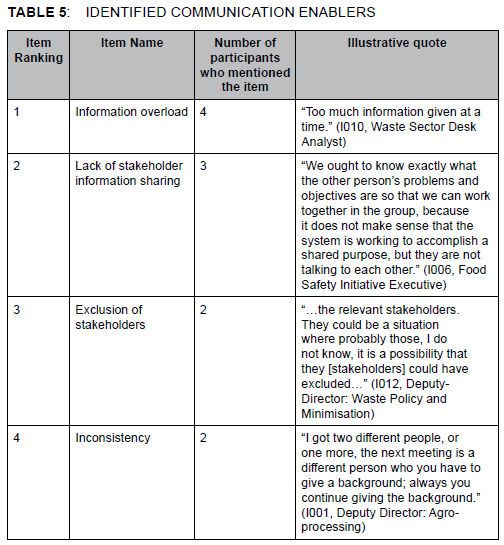

The last theme explains some of the communication barriers the participating stakeholders identified in this MSP. Table 5 summarises the findings related to the communication barriers that may affect the success of the voluntary agreement.

The four barriers identified in the findings are: (1) information overload; (2) lack of stakeholder information sharing; (3) exclusion of stakeholders; and (4) inconsistency.

CONCLUSION

This study's aim was to show that effective communication in MSP can help achieve SDG 12.3 through the SAFLWVA. The findings revealed valuable insights, which answered the research questions posed at the beginning of the study.

The findings indicate that stakeholder mapping is vital and provides insights into the various channels of communication seen by the participants as most effective within the SAFLWVA. The research findings provide new insights into improving communication with all stakeholders using the necessary channels, which are suited to each stakeholder within an MSP.

The research further found that stakeholders will encounter different communication enablers and barriers that affect how they will communicate with each other in the SAFLWVA. The findings as to the main communication enablers for the multi-stakeholders were that there needs to be trust amongst stakeholders to share important and relevant information. The participants also noted that effective education on the benefits of participating in the partnership, accompanied by ensuring that partners receive perceived value from the SAFLWVA, is essential for achieving SDG 12.3.

The communication barriers that the participants stated could hinder the effectiveness of the MSP pertain to large amounts or too much information being shared by the CGCSA, but not enough information being shared by the relevant stakeholders who are involved in the SAFLWVA. Some participants also noted that certain key stakeholders were not involved from the start and were still not involved, creating a large gap of knowledge and information sharing that needed to be filled.

Managerial recommendations

The findings of this study clearly identify the main communication barriers and enablers that are present in the SAFLWVA MSP. These should be used to develop a communication framework enabling better communication, whilst actively curtailing the barriers. Addressing these barriers will lead to more effective communication and thus a more successful voluntary agreement. Secondly, the need for stakeholder mapping emerged in the findings. Therefore, it is recommended that within the communication framework a section be included where various communication channels and techniques are mapped according to the needs of each relevant stakeholder. Lastly, the benefits stakeholders would enjoy in signing up with the SAFLWVA MSP should be more clearly communicated. From the findings of this study, the already identified benefits should be used in the communication messaging. The findings could be used to determine the messaging and communication strategy (evolving from the stakeholder mapping, communication methods, barriers, and enablers).

Limitations and directions for future research

This study specifically focused on how the MSP could achieve SDG 12.3 for the SAFLWVA. Further research could broaden the knowledge on utilising MSPs in voluntary agreements to achieve other SDGs. Not many studies have been conducted on voluntary agreements in developing countries. Therefore, more studies of this nature should be undertaken in a variety of contexts. This study received responses from 15 participants. These research findings could be expanded to quantitatively evaluate the findings allowing for a larger number of participants and a broader reflection of the views of MSP stakeholders.

REFERENCES

Affognon, H., Mutungi, C., Sanginga, P. & Borgemeister, C. 2015. Unpacking postharvest losses in Sub-Saharan Africa: A meta-analysis. World Development 66: 49-68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.08.002 [ Links ]

Baggot, R. 1986. By voluntary agreement: The politics of instrument selection. Public Administration 64(1): 51-67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.1986.tb00603.x [ Links ]

Beisheim, M. & Simon, N. 2016. Multi-stakeholder partnerships for implementing the 2030 Agenda: Improving accountability and transparency. Analytical Paper for the 2016 ECOSOC Partnership Forum. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2767464 [ Links ]

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. 2012. Thematic analysis. In: Cooper, H. (ed.) APA Handbook of research methods in psychology. Volume 2. Research designs. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13620-004 [ Links ]

Brouwer, H., Woodhill, J., Hemmati, M., Verhoosel, K. & Van Vugt, S. 2016a. The MSP Guide. Available at: http://www.mspguide.org/sites/default/flles/case/msp_guide-2016-digital.pdf [Accessed on 16 March 2020]. [ Links ]

Brouwer, J.H., Hemmati, M. & Woodhill, A.J. 2016b. Seven principles for effective and healthy multi-stakeholder partnerships. Great Insights 8(1): 9-11. https://doi.org/10.3362/9781780446691.000 [ Links ]

CGCSA. 2019. South African Food Waste Voluntary Agreement: Business Plan Implementation Workshop. Available at: https://www.cgcsa.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Business-Plan-Implementation-Workshop-Morning-Session.pdf [Accessed on 28 March 2020]. [ Links ]

CGCSA. 2020. South African companies close to signing voluntary agreement to reduce food loss and waste. Available at: https://www.cgcsa.co.za/south-african-companies-close-signing-voluntary-agreement-reduce-food-loss-waste/ [Accessed on 1 May 2020]. [ Links ]

Creswell, J.W. 2012. Education research: planning, conducting and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. (Fourth edition). Boston: MA: Pearson. [ Links ]

Dentoni, D., Bitzer, V. & Schouten, G. 2018. Harnessing wicked problems in multi-stakeholder partnerships. Journal of Business Ethics 150(2): 333-356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3858-6 [ Links ]

Du Plooy-Cilliers, F., Davis, C. & Bezuidenhout, R.M. 2014. Research matters. Paarl: Paarl Media. [ Links ]

FAO. 2020a. Sustainable Development Goal 12. Available at: http://www.fao.org/sustainable-development-goals/goals/goal-12/en/ [Accessed on 20 March 2020]. [ Links ]

FAO. 2020b. Sustainable Development Goal 17. Available at: http://www.fao.org/sustainable-development-goals/goals/goal-17/en/ [Accessed on 20 April 2020]. [ Links ]

Irfanoglu, Z.B., Baldos, U.L., Hertel, T. & Van der Mensbrugghe, D. 2014. Impacts of reducing global food loss and waste on food security, trade, GHG emissions and land use. Conference papers 332486. Purdue University, Centre for Global Trade Analysis, Global Trade Analysis Project. [ Links ]

Kapur, R. 2018. Barriers to effective communication. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323794732_Barriers_to_Effective_Communication/citation/download [Accessed on 1 April 2020]. [ Links ]

Kimiywe, J. 2015. Food and nutrition security: challenges of post-harvest handling in Kenya. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 74(4): 487-495. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0029665115002414 [ Links ]

Lindén, A.-L. & Carlsson-Kanyama, A. 2002. Voluntary agreements - a measure for energy-efficiency in industry? Lessons from a Swedish programme. Energy Policy 30(10): 897-905. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-4215(02)00003-4 [ Links ]

Lipinski, B., Hanson, C., Lomax, J., Kitinoja, L., Waite, R. & Searchinger, T. 2013. Reducing food loss and waste. World Resources Institute Working Paper 1-40. [ Links ]

MacDonald, A., Clarke, A., Huang, L., Roseland, M. & Seitanidi, M.M. 2018. Multi-stakeholder partnerships (SDG #17) as a means of achieving sustainable communities and cities (SDG #11). In: Leal Filho, W. (ed.). Handbook of sustainability science and research. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-63007-6_12 [ Links ]

Mohr, J. & Spekman, R. 1994. Characteristics of partnership success: partnership attributes, communication behavior, and conflict resolution techniques. Strategic Management Journal 15(2): 135-152. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250150205 [ Links ]

Mostert, W., Niemann, W. & Kotzé, T. 2017. Supply chain integration in the product return process: A study of consumer electronics retailers. Acta Commercii 17(1): 1-16. https://doi.org/10.4102/ac.v17i1.487 [ Links ]

Murray, J. 2018. How Unilever integrates the SDGs into corporate strategy. GreenBiz, 15 October. Available at: https://www.greenbiz.com/article/how-unilever-integrates-sdgs-corporate-strategy [Accessed on 1 April 2020]. [ Links ]

Myers, M.D. 2013. Qualitative research in business and management. (Second edition). Los Angeles: CA: SAGE. [ Links ]

Nahman, A., De Lange, W., Oelofse, S. & Godfrey, L. 2012. The costs of household food waste in South Africa. Waste Management 32(11): 2147-2153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2012.04.012 [ Links ]

Palinkas, L.A., Horwitz, S.M., Green, C.A., Wisdom, J.P., Duan, N. & Hoagwood, K. 2015. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 42(5): 533-544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y [ Links ]

Priefer, C., Jörissen, J. & Bräutigam, K. R. 2016. Food waste prevention in Europe - A cause-driven approach to identify the most relevant leverage points for action. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 109: 155-165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2016.03.004 [ Links ]

Radovic Markovic, M. & Salamzadeh, A. 2018. The importance of communication in business management. 7th International Scientific Conference on Employment, Education and Entrepreneurship, Belgrade, Serbia. [ Links ]

Refresh. 2018a. Launch of food waste reduction China action platform at the 2018 China sustainable consumption roundtable. Available at: https://eu-refresh.org/launch-food-waste-reduction-china-action-platform-2018-china-sustainable-consumption-roundtable [Accessed on 28 April 2020]. [ Links ]

Refresh. 2018b. Voluntary agreements as a policy instrument for food waste reduction. Available at: https://eu-refresh.org/sites/default/files/MINUTES_REFRESH-Policy-Working-Group-on-VAs.pdf [Accessed on 27 April 2020]. [ Links ]

Secondi, L., Principato, L. & Laureti, T. 2015. Household food waste behaviour in EU-27 countries: A multilevel analysis. Food Policy 56: 25-40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2015.07.007 [ Links ]

Shafiee-Jood, M. & Cai, X. 2016. Reducing food loss and waste to enhance food security and environmental sustainability. Environmental Science & Technology 50(16): 8432-8443. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b01993 [ Links ]

Sheahan, M. & Barrett, C.B. 2017. Food loss and waste in Sub-Saharan Africa. Food Policy 70: 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2017.03.012 [ Links ]

Sloan, P. & Oliver, D. 2013. Building trust in multi-stakeholder partnerships: Critical emotional incidents and practices of engagement. Organisation Studies 34(12): 1835-1868. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840613495018 [ Links ]

Stacho, Z., Stachová, K., Papula, J., Papulová, Z. & Kohnová, L. 2019. Effective communication in organisations increases their competitiveness. Polish Journal of Management Studies 19: 391-403. https://doi.org/10.17512/pjms.2019.19.L30 [ Links ]

Thornsbury, S. & Minor, T. 2019. Food loss as a wicked problem. The Economics of Food Loss in the Produce Industry 55-58. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429264139-22 [ Links ]

United Nations. 2019. Global indicator framework for the Sustainable Development Goals and targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available at: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/indicators/Global%20Indicator%20Framework%20after%202019%20refinement_Eng.pdf [Accessed on 2 April 2020]. [ Links ]

United Nations. 2020. About the sustainable development goals. Available at: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ [Accessed on 20 April 2020]. [ Links ]

University of Pretoria. 2019. An overview of selected qualitative research designs. Available at: https://clickup.up.ac.za [Accessed on 17 June 2020]. [ Links ]

WWF. 2017. Food loss and waste: Facts and futures. Available at: https://dtnac4dfluyw8.cloudfront.net/downloads/wwf_2017_food_loss_and_waste_facts_and_futures.pdf?21641/Food-Loss-and-Waste-Facts-and-Futures-Report [Accessed on 22 February 2020]. [ Links ]

Date submitted: 27 December 2022

Date accepted: 15 June 2023

Date published: 15 December 2023