Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Communitas

versión On-line ISSN 2415-0525

versión impresa ISSN 1023-0556

Communitas (Bloemfontein. Online) vol.28 Bloemfontein 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.38140/com.v28i.7599

ARTICLES

Safety of journalists from a gendered perspective: evidence from female journalists in Ghana's rural and peri-urban media

Theodora Dame Adjin-TetteyI; Manfred A.K. AsumanII; Mary Selikem Ayim-SegbefiaIII

IDurban University of Technology, Durban, South Africa. Email: theodoradame@yahoo.com (corresponding author). ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3160-9607

IIThe University of Western Ontario, Ontario, Canada. Email: masuman@uwo.ca. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0319-5870

IIIUniversity of Media Arts and Communication, Accra, Ghana. Email: mary.ayim@nafti.edu.gh. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7281-3703

ABSTRACT

This study sought to explore the safety risks female journalists working in Ghana's rural and peri-urban media encounter, how safe they feel, and how they are coping with safety breaches. Thirteen semi-structured interviews were conducted with female journalists employed by Ghanaian broadcast media outlets in rural and peri-urban areas. Guided by Braun and Clark's (2006) six steps for qualitative data analysis, interview transcripts were thematically analysed. It was found that physical and emotional security threats and poor working conditions were the main threats to female journalists working in Ghana's rural and peri-urban media. While there are generally bad working conditions in Ghana, some of the participants believe that men receive more benefits and opportunities for professional growth than women. Compared to their male counterparts, females are occasionally ridiculed and refused training and professional opportunities. When there are safety violations, employers generally offer little assistance. Female journalists cope with violations and insecurities by self-censoring, avoiding working during specific hours of the day, and steering clear of reporting conflicts, politics, and elections as a safety measure. The study recommends that to avoid maladaptive actions by journalists, media organisations should address the safety needs of their female journalists.

Keywords: journalism, safety of journalists, safety violations, gender, female journalists, rural media, peri-urban media, Ghana

INTRODUCTION AND STUDY RATIONALE

This study explores the safety risks encountered by female journalists in Ghana's rural and peri-urban media in the news gathering and distribution process. Safety of journalists is the ability of journalists and media professionals to receive, produce and share information without facing physical or moral threats, as well as threats to their psychological, digital, and financial integrity and well-being (Andreotti et al. 2015; Slavtcheva-Petkova et al. 2023). According to H0iby and Ottosen (2019), reporter safety affects journalism, media freedom, free speech, democracy, and society at large. Globally, media freedom is on the wane as violations of journalists continue unabated (UNESCO 2022). Journalists have increasingly become the target of killings, physical attacks, acts of intimidation, offline and online harassment, harassment through judicial powers, imprisonments, and smear campaigns (Andreotti et al. 2015; Ferrier 2018; Appiah-Adjei 2021). The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) reports that in 2020, there were 274 cases involving the imprisonment of journalists. Again, according to the 2022 Report on the Safety of Journalists and the Danger of Impunity, since 2008, the lowest ever recorded annual deaths among journalists were 55 killings. Also, between 2020 and the end of 2021, a total of 117 journalists were murdered (UNESCO 2022).

In addition to being threatened and slain, nine out of ten recorded murders go unsolved and without the offenders receiving any punishment (UNESCO 2020). This contributes to the increasing impunity with which journalists are attacked as it is likely any offence against journalists will go unpunished. Amid this, women journalists have become easy targets of murders and sexual offences (Ibrahim et al. 2021; UNESCO 2022). UNESCO (2022) revealed that the number of women journalists killed in 2021 was twice as many as what were accounted for in 2020.

A 2020 study indicated that the harassment of journalists is more likely to negatively impact women who are involved in the news collection/news delivery process (Lewis et al. 2020). Due to the multifaceted nature of the harassment and safety issues faced by women in journalism, women journalists find it difficult in deciding how to respond to the harassment they face from other actors in the news production and distribution value chain, as well as news audiences (North 2016). As noted by McCosker (2014), women journalists who cover political news are most likely to face some form of harassment and violence during their careers. The harassment faced by women journalists are usually in the form of disruptive in-person harassment, abrasive in-person harassment, sexual harassment, and online harassment (Lewis et al. 2020). Evidently the effects of the threats, sexual abuse, and name calling meted out to women journalists stretch into their personal lives and have in some instances forced women journalists to abandon their careers because of fears for their safety (White 2009).

From a sociological perspective, it is widely reported that it is difficult for women journalists to practice in more conservative traditional societies than men. This is because the traditional institutions promoted by patriarchy restrict women and block their career development in professions such as journalism. Out of the five radio stations in rural Ghana studied by Asuman and Moodley (2023), none employed women as on-air news personalities because of the safety concerns attributed to being a woman journalist in a historically volatile area such as rural Northern Ghana.

Studying the safety of journalists in terms of gender can help to raise awareness of the specific risks faced by women journalists and lead to the development of targeted interventions to improve safety. Pöyhtäri and Berger (2015) indicate that research on safety will not only deepen understanding of the intricacies of the safety of journalists but will also form the framework for creating a better and safer atmosphere for working journalists. Despite the scholarly attention on attacks and threats to journalists, literature on the safety of journalists in the specific case of Ghana is scanty. Recent studies on Ghana have either been exploratory or conceptual. These studies aimed to understand the state of media freedom and safety risks faced by journalists (Bodine 2022); others looked at the causes of threats against journalists to conceptualise safety (Nyarko & Akpojivi 2017); and more recently, the threat of the COVID-19 pandemic on the work and safety of Ghanaian journalists (Boateng & Buatsi 2022; Adjin-Tettey & Braimah 2023).

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

To ascertain the safety risks female journalists working in Ghana's rural and peri-urban media encounter while doing their work, the following research questions guided the study:

1. What are the most common safety violations female journalists encounter in the line of duty when compared to male journalists?

2. Who do female journalists identify as the key perpetrators of safety violations?

3. How safe do female journalists feel performing their jobs in Ghana?

4. What strategies do female journalists employ to secure their safety?

THEORETICAL GROUNDING

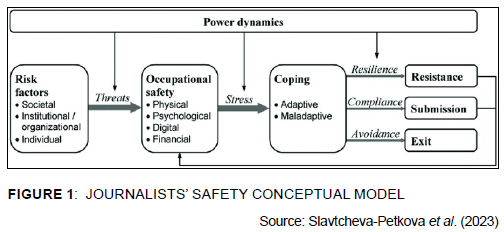

The study was motivated by Slavtcheva-Petkova et al.'s (2023) Journalists' Safety Conceptual Model. The Model suggests that risk factors for journalists can be divided into three categories: societal, institutional, and individual. These risk factors speak to how the actions of key stakeholders within the media ecology and the public contribute to making journalism/journalists thrive or lose its/their relevance (Adjin-Tettey & Braimah 2023).

The risk factors result in threats, which can be categorised as physical, psychological, digital, and financial. Threats turn into pressures that force journalists to use either healthy or unhealthy coping mechanisms. When journalists use adaptive techniques, they either develop resilience so that they can continue, or they give in to the pressures placed on them to continue working in the industry. When the risk is considerable, the maladaptive responses lead to avoidance of the threat, which finally results in them leaving the profession.

Slavtcheva-Petkova et al. (2023) focus on the resilience of journalists in a climate of constrained media freedom. Maladaptive tactics have a detrimental impact on the journalism industry as this means the loss of potentially quality human resources for the media industry. Journalists who choose compliance, on the other hand, demonstrate acquiescence to the authorities behind the threats; thus, decreasing their autonomy. As a result, they engage in behaviour such as self-censorship, concealing one's name or gender, and avoiding contact with news consumers (Post & Kepplinger 2019). Compliance can be seen positively or adversely since, while it is seen as showing resilience, it potentially degrades the quality of reporting (Slavtcheva-Petkova et al. 2023) as journalists may conform to pressure (compliance) to keep going.

Female journalists struggle to decide how to respond to the harassment they experience from other players in the news production and distribution value chain as well as news consumers due to the complexity of the harassment and safety issues experienced by them (North 2016). This study offers an opportunity to examine the various strategies used to address the safety violations experienced by female journalists. It will be particularly helpful because, even though peri-urban and rural communities have unique problems that may not be comparable to those in metropolitan societies, most studies have been general and have provided little information for female journalists working in peri-urban and rural media. Determining whether strategies are adaptive or maladaptive and the resultant consequences is imperative to ensure that a conducive atmosphere is created for female journalists to excel in their chosen careers.

METHODS

The study adopted a purely qualitative approach in the collection and analysis of data. In this study, the researchers got close to journalists practising in Ghana's rural and peri-urban media (through semi-structured interviews) to learn about their experiences with safety breaches while performing their jobs and to find out how safe they feel working as female journalists to determine how they deal with such experiences, how safe they feel practicing as journalists, and the safeguards they would have their media outlets enact to ensure their safety.

Before starting the fieldwork, ethical approval for the study was sought and received from the Faculty's Research Ethics Committee at the University of Ghana's Department of Communication Studies. The idea for this study emerged from the conclusions drawn from the State of the Ghanaian Media Report (2023) which was published by the University of Ghana Press, and which highlighted the harassment and abuse of journalists as one of the factors affecting the growth and interest of women in media work in Ghana (Adjin-Tettey 2023).

Sampling and sample size

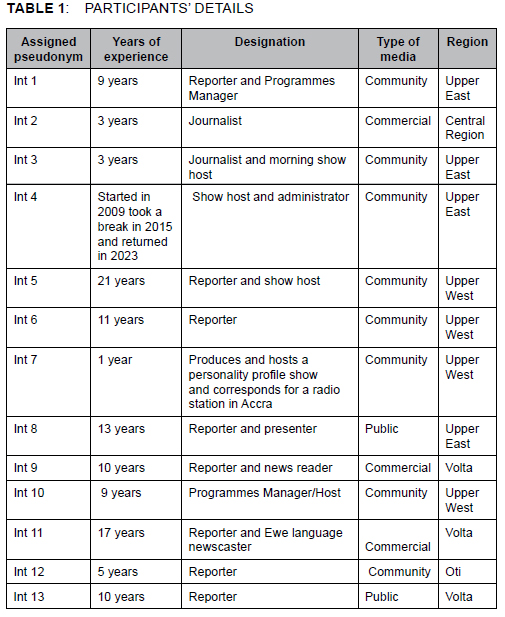

Interviewees were purposively selected based on Asuman and Moodley's (2023) finding that not many women are employed as radio journalists in rural and peri-urban Ghana. The selection criteria were that participants had to be female journalists who work in media outlets located in a rural or peri-urban area or region of Ghana. Rural and peri-urban media were operationalised as broadcast media outlets located in geographic areas that are located outside urban towns and cities. The economy of rural areas is typically agrarian and smaller compared with urban areas. The areas also have a low population density and small settlements. Community media tend to be in rural towns and formed part of the media outlets considered. A total of 13 participants were selected across 11 rural and peri-urban broadcast media outlets. The interviews were conducted over a two-month period; each interview lasted an average of 40 minutes. The interviews were conducted using the telephone and the videoconferencing application, Zoom. Table 1 provides a breakdown of the participants.

Due to the sensitive nature of violence and harassment, especially for women working in media and journalism (UNESCO 2020), the researchers decided to keep the interview participants anonymous. This was to ensure data validity and data reliability and protect their identities to ensure their safety. All interviewees were assigned pseudonyms, and their media houses were kept anonymous for the purpose of this study.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis was used to analyse the transcribed data from the interviews. It enabled the researchers to construct themes within the data. The researchers followed the six steps in constructing themes for analysis, as proposed by Braun and Clark (2006). The first step, data immersion, involved familiarisation with the data. Codes were developed for the transcribed interview data in the second stage. The researchers then developed broader patterns of meaning from the codes of the transcribed data in the third stage. In the fourth stage, themes were developed which were paired against the research questions. Themes were defined and paired based on how they addressed the research questions of the study. Themes included "safety risks by journalists practicing in rural areas", "domestic challenges that interfere in the work of female journalists", "assignments women journalists shun to minimise risk" and others. This led the researchers to the fifth stage, which involved naming and defining the themes, and finally the sixth stage, which involved selecting extracts from the interview data and using these to answer the research questions (Braun & Clark 2006).

RESULTS

Women working in rural and peri urban media

There are fewer women working as journalists in rural media. Most of the female journalists interviewed also work in other fields, primarily as schoolteachers. Some women in full employment with media organisations were secretaries with no connection to journalism. Moreover, the quest to recruit female interns to pursue journalism training in rural media organisations proved challenging although there are many news outlets operating in rural Ghana. One participant said there were only about ten female journalists practicing in the entire Upper West region. There are slightly more female radio presenters; but generally, journalism practice in rural media is male dominated.

Upper west is male dominated when it comes to journalism (Int 7).

Although there might be other factors, the current situation may be due to the numerous obstacles women face when working as journalists in rural areas, as opposed to men.

Safety risks experienced by journalists practicing in rural and peri-urban media

Even though some female journalists encounter safety hazards more than their male colleagues, the female journalists who were interviewed described a variety of situations that compromise their safety and make their work precarious, with some of these not specific to the experiences of female journalists. The police limiting access and concealing information from journalists are challenges faced by media outlets in Ghana's rural areas that are experiencing conflict.

Ghana Police have made it clear to us that they can't talk certain issues, even if there are eyewitnesses to them. When you call them [the Police], the Regional Commander is not ready to talk because he feels his position may be threatened. When we go to the PROs whose job it is to speak to the media, they don't speak to us (Int 1).

Journalists' working conditions, which is viewed as bad and as a potential source of demotivation for all journalists, is one of the concerns faced by journalists working in rural media.

The condition of service is very poor. We are supposed to be given allowances but at the end of the day what comes to the radio station, is not even enough to run it, nor to talk of compensating you (Int 4).

However, despite claims to the contrary, journalists endure the unfavourable working conditions because they are passionate about their work.

My station is community-based so it is non-profit. You know, the media in the rural area doesn't attract much advertising revenue, so everything is not really straightened at my end. I just do what I can do at my own pace. It is the passion that keeps me going (Int 7).

One participant who works in the Upper East region states that wages in this area are lower, even for journalists who work for a media conglomerate that is owned by the same company as those in other regions and in Accra, the country's capital; this is another factor that makes practicing in rural areas an unattractive venture for female journalists.

You wouldn't believe the salaries of journalists in this region. For public media, even Jamale workers earn better than those of us here. Some take less than GHS 500 ($50), while others earn even less, even for some private media that are supposed to pay better. Sometimes journalists must depend on soli [Ghanaian journalistic jargon which loosely means tips or gifts] and the generosity of sources. I tell you, poverty sometimes influences reportage (Int 9).

Like their male colleagues, female journalists are vulnerable to physical attacks when they report from dangerous locations (i.e., conflict and dispute-prone places) as certain factions might believe that they are working for "unfavourable reasons". Political news also often exposes journalists to assault, especially physical assault. Therefore, covering these beats has become risky for all journalists working in rural and peri-urban media.

Female journalists' safety-related risks - internal organisational challenges/risks

In-house risks that female journalists reported included emotional abuse, undervaluing of their skills, gendered unfair working conditions, sabotage by male co-workers, sexual harassment by male managers and colleagues, and tribalism that intersects gender lines. Women typically get the low-profile and follow-up stories after the men have taken a solid bite on the stories, whereas males are immediately allocated high-profile beats that boost their careers and/or earn them favours and perks.

Also, females are less likely to occupy managerial positions or positions of leadership in news organisations in rural media. Furthermore, male-dominated management frequently sabotage female journalists who are rising to prominence. They achieve this by limiting the time they can speak on air, giving them low-profile tasks, dictating the sequence and structure of their programmes, taking away their jobs after they return from maternity leave, and creating obstacles in their path so that they will give in to pressure to quit their jobs. There is also the issue of sexual harassment, which can sabotage the professional relationships of female journalists.

Even while pay and working conditions are generally poor, the study found that these situations might have a gendered twist that disadvantages women and places them in a more precarious position than their male co-workers.

When there's a programme that comes with certain benefits, they just call some of their male journalist friends, two or three, to go. [When they come, they'll call the female journalists to do the follow-up stories]. And this is so intimidating, if you think we have those capabilities of taking the stories up, why don't you involve us from the beginning? (Int 1).

In addition, women are less likely to have prospects for advancement or training, as their male counterparts are given most of the training opportunities. One journalist described how she almost lost her job because she enrolled in a fact-checking training course that she intended to use in her work.

It was as if they wanted him alone to attend the programme. This is because I was the only one suspended; even though a male colleague also attended the programme. Meanwhile you said both of us cannot go. If both of us cannot go, and both of us ended up going, why was only one person suspended? (Int 3).

One participant was visibly upset about how their colleagues dismissed their skills and attributed their achievements on favours they received in exchange for sexual favours.

And some people don't hide it. They go as far as making fun of you about it. They don't even ask you. They say it like that is it. They feel like no matter how good you are it was because you opened your legs somewhere; excuse me to put it that way. It's very insulting and demoralising because your hard work is overlooked just because they feel like you didn't work hard enough but you rather went through other means to get what you have or to do a job you're doing (Int 4).

Domestic challenges that interfere with female journalists' work

The domestic challenges that constitute potential threats to female journalists are the insecurities that the spouses and in-laws of female journalists have owing to the exposure of their employment. Int 4 described such an experience at the start of her career.

When I started working for the radio station the perception was that my husband had given me so much freedom to just go for assignments, and most of our family members were surprised. [...] You know, sometimes as a woman you would experience some of these challenges because of some structural and cultural problems. But over the years, I have proven to my husband that I have passion for what I do, and I will continue to do it (Int 4).

Moreover, female journalists are most negatively impacted by the rural stereotype that media professionals are promiscuous and unfaithful in their personal relationships. One participant stated that there has long been a belief in her society that journalism is exclusively for men.

When you go to the field, the men do not see you as a journalist but just a woman. It is not only our colleagues but every man you meet, except those who know you (Int 9).

The frankness of female journalists goes against cultural expectations. Because of this, many people think that women who work in the media are heartless. The false assumption that female journalists are unfaithful and commonly have marital or relationship issues also contributes to the perception that they are irresponsible.

For one participant, the fear that husbands and in-laws have about the relationships that female journalists have with their male colleagues puts those journalists' emotional and psychological well-being at risk. This is because partners have, on occasion, assaulted female journalists' superiors because of their suspicions. This led to certain managers giving female journalists the cold shoulder, jeopardising their job security. Due to a similar problem she had to deal with, one participant had to take a significant break from work, which could have jeopardised her career.

I have fought my way back. [...] I have passion for journalism, and I will still do it (Int 6).

Field-specific risks

While all reporters suffer physical threats when covering conflict, female reporters state that it is harder for them to cover such stories. To protect themselves from physical harm, female journalists tend to avoid such stories. Additionally, there are instances where female journalists' personal safety is jeopardised while trying to secure an interview with a newsmaker in the setting of a contested space. Although some male colleagues support their female colleagues, some are unaware of the fact that women have less physical strength than men.

When we're at a place on assignment and we're supposed to take some information, most of the men try to push us back and put their recorders there. Sometimes, you must give your recorder to someone to hold and record for you (Int. 5).

Sometimes information is withheld from female journalists just because they are female. Coincidentally, most institutional sources of information are men. While there are rare instances when sources favour female journalists when they ask for interviews, others have had to put up with advances from male sources to gain interviews.

They grant you the interview so quickly because you are a woman and they are interested in you, so you will be happy and show up again when needed. Other times, they'll lure you away from what you want and delay you to get closer to you in a particular way (Int 4).

Female journalists have occasionally experienced delays and disdain when trying to obtain information from newsmakers and sources. On occasion, sources will only provide information to female journalists if they consent to their advances.

There was a time when a source kept pushing back the interview and kept claiming to be busy to lure me out in the evening. He was implying that if I could go out with him in the evening, I would be able to get what I was after from him (Int 5).

In most cases, advances by male sources towards female journalists turn into sexual harassment. In addition, journalists working in rural areas must travel long distances to cover stories. Without reliable transportation, the best strategy is to obtain help from community leaders. Int 11 mentioned that community leaders are the main source of aid in securing journalists' safety as they sometimes assist in getting them safe transportation back home.

Frequent perpetrators of safety violations

The participants identified the heads of institutions/newsmakers, colleagues, political party loyalists and community members as the frequent perpetrators of violations, which mainly came in the form of verbal attacks, emotional abuse, discrimination, disrespect, and physical attacks.

Politicians and their followers are one of the biggest perpetrators. Sometimes, our community members are also perpetrators of violence. Any opinion you express on air can be misinterpreted by somebody, and that can easily make you a target of violence and abuse (Int 6).

Sometimes, statements made by journalists on talk shows or how they control discussions that support a side they disagree with enrage community members, spurring them to harm journalists.

Assignments that women journalists will likely shun to minimise safety hazards

The female journalists interviewed admitted that they avoid certain assignments due to concerns about their safety. Journalists in the Upper East region said they avoid stories related to ethnicity and conflict, and stories on Bawku and Mamprusi because of active conflict and chieftaincy disputes. Most females also avoid election coverage, whether assigned or not. This is because of the propensity for high tensions during election periods, which could escalate into violence.

Most media outlets in Ghana's rural towns do not offer transport to their journalists. Hence, journalists need to arrange their own transport, typically a motorcycle. Therefore, the likelihood of having to work late into the night while covering an election deters many female journalists from accepting such assignments.

What rural media organisations are doing to secure the safety of their journalists

Some of the media organisations have guidelines for content production to guide talk programmes, particularly political ones, to equip their journalists in avoiding ethical breaches, which could attract attacks. However, there are no organisational safety measures in place for journalists working in the rural and peri-urban media under study. Most organisations also do not have anti-sexual harassment policies.

Moreover, there are no formal measures concerning securing the physical safety of journalists at work, apart from the general security services in the workplace, which are mainly provided at night. When physical harm occurs in the line of duty, some participants said that colleagues aid the affected journalists in the form of financial support. Colleagues also call the police when their colleague is in harm's way. For a media organisation, there are "safety dues" and welfare dues, which are drawn from their salaries; they revert to these contributions when a colleague experiences a safety threat, which requires financial support to help them recover. For one of the media organisations, there appears to be systemic action to ensure their journalists' safety; but ultimately security lies with the journalists themselves.

My current organisation (state-owned) has the sectional head advise those s/he is supervising about the possible safety implications for an impending assignment and/ or developing story and ask that reporters use their discretion in such circumstance(s) to stay safe (Int 13).

Even though elections are potentially volatile, the journalists working in rural media are not typically given the requisite gear for covering such stories. The only instrument that could possibly guarantee their safety is the tag that identifies them as journalists.

Likelihood of long-term practice for female journalists working in rural media

Given the difficulties they experience in their line of work, several of the female journalists had second thoughts about continuing in the field in the long term. Others, though, were ready to do so for however long they could. One journalist stated that if she had not been given the opportunity to work as a journalist, she would have founded her own media organisation due to her intense passion for the job.

Had I not been in radio, I would have started a radio station myself because I want to impact society. I want to see how I can contribute with my knowledge to support young people, women, and vulnerable men (Int 4).

Conditions of service is a deciding factor for female journalists who are undecided about staying in the profession in the long term. If their working circumstances did not change, they might stay if they could find complementing part-time employment elsewhere.

For now, when it comes to what we take home, it's not much, so some of us must get a job and do journalism part-time. Where I am currently does not encourage me to stay in the profession full time because I don't make much and the job is really demanding (Int 6).

I sell some products and I get commission from the companies. That is what is keeping me. I love the job and I want to stay because if you go off air, nobody will know you exist (Int 9).

What rural and peri-urban journalists are doing to stay safe

Female journalists have taken precautions to reduce the risks they face. Most of them said that they avoid conflict and politically related stories. Another precaution is to avoid working at odd hours to prevent physical assaults from people who might be angry about their line of work.

As a female I won't work at odd hours. When I'm going home, I go during rush hour so that I know I will be safe (Int 1).

This implies that female journalists, due to circumstances, miss out on opportunities to cover significant stories that emerge at unusual hours and that have the potential to advance their careers.

In addition, some participants were of the view that by sticking to the ethics of journalism, they could avoid conflict situations involving the public. As a strategy, they ensure that they speak to the available facts. Additionally, they are quick to apologise when it is important to make amends for any ethical breaches they may have committed. One participant acknowledged constantly being careful about what she writes and says, particularly when it involves politics. This raises concerns about self-censorship and its effects on media freedom generally.

I guard whatever I write and say, so that I don't have issues with the public and politicians. I also make sure I own up to whatever comes my way. I'm my own motivator, inspirer, and protector, even before the organisation comes in (Int 9).

Participants' recommendations to media outlets to protect female journalists

The participants suggested ways media houses could protect female journalists working in Ghana's rural media outlets. Some of these are discussed below.

Training on safety

Some participants believed that journalists' susceptibility to safety breaches could be attributed to the lack of requisite skills to sense danger or potential safety breaches and to prevent them. For Int 5, the lack of comprehensive journalistic training renders female journalists susceptible to risks while fulfilling their reporting responsibilities. Most of the journalist practicing in rural/peri-urban media suggested training programmes, which provided them with the tools to avoid different types of attacks.

Additionally, upholding the principles of truth and accuracy is key. The participants believe that journalists must thoroughly verify information before reporting on it to avoid spreading misinformation or sensationalising events. In rural settings, where access to reliable information may be limited, adhering to this principle is even more critical to avoid exacerbating existing tensions or conflicts.

Involving police when covering conflict, ethnic issues

Some of the journalists who hail from specific regions in Ghana that are conflict-prone and have chieftaincy disputes asserted that, for female journalists to report on these issues confidently and comprehensively, it is important to engage security personnel when covering such issues within communities. The presence of security personnel could serve as protection, affording the female journalists a sense of security in the line of duty. Most of the journalists were of the view that their organisations must work together with security organisations to establish a dedicated group who could protect reporters working in the region.

Support from media organisations

According to some of the participants, employers must give female journalists the platform and support to express their talents and open their platform to more women-centred programmes. For Int 6 the tendency of media organisations to leave their employees to their own fate is a major disincentive. Managers must assure employees of their support when needed and make them aware of safety and welfare provisions they have in place for them. For women who have other social responsibilities to take care of, flexible work schedules would be a major boost.

I am expected to be at work at 7:30 am and close at 5:30 pm which are very long hours. I am a mother and I have my family to take care of. Media organisations can employ modern techniques for journalists to easily work with. Some of the programmes like announcements can be recorded and played so that after the afternoon news broadcast, I can go back home (Int 9).

Most journalists working in rural areas must go the extra mile when covering stories in remote areas. This means that they must contend with poor roads and bad transportation services in remote areas, putting them at risk. The participants said that media organisations must provide reliable transportation to enhance their work.

Social marketing to increase revenue for community media

Rural media, particularly community media, rely on donor funding for survival (Asuman & Moodley 2023). Although journalists are happy to serve the communities they work for, they could benefit from good compensation to be able to do that. Some of the journalists were of the view that the reliance of community media on donor funding is not sustainable. They asked that legislation governing community media be revised to allow community media to try out other business models to generate revenue to do quality journalism and to compensate their journalists.

We can't just keep relying on donors ... by the time the monies come, it has so much work to do, we usually have a backlog of arrears to pay. If we engage with the community, we could get women to train to make shea butter cream and make soap to sell to generate income. We are advertising local businesses, so it would be very nice if we had our own business to generate income (Int 4).

Insurance, medical and legal aid

Some participants appealed for support from their employers when they experience safety breaches. Some also appealed for insurance cover for workplace accidents and recounted how colleagues who had suffered physical safety breaches in the past were admitted to hospital without any material support from management.

I learned a while ago that every institution is supposed to get an insurance for workers where they must be contributing for the future of that person. If anything happens to me on the job, the contribution can help my kids or my husband. They don't pay us well, so if they do this for us, we'll appreciate it (Int 5).

In an era where journalism plays a pivotal role in shaping societies, the need for a robust legal aid system for female journalists has become increasingly evident (James 2002). Female journalists, particularly those working in the rural areas of Ghana, encounter distinct challenges in their reportage that necessitate protection and support (Nyarko & Akpojivi 2017). One of the participants stated that female journalists often encounter adversities ranging from harassment and intimidation to legal threats and physical attacks. These challenges not only hinder their professional growth but also inhibit their ability to deliver unbiased and essential information to the public. By providing legal aid, female journalists could be empowered to pursue investigative and impactful stories without fear of retribution or being silenced.

Another way the station might be able to assist is if they hire a lawyer for the organisation and make it clear that if any of us have problems, there will be a lawyer who can at least defend us. However, I have seen many of my colleagues struggle to escape court after having issues with the police or other people (Int 5).

Public education

It was further stated that if the public is aware of and appreciates the function of journalism, they are more likely to offer the needed protection and support that female journalists need to be able to do their work without fear of hostility and attacks. Public education could also shed light on the issue of the harassment faced by female journalists and the need for a safe working environment. This could ensure behavioural changes among community members.

The National Communication Authority and other relevant agencies must engage in public education. When we have such bodies coming to give public education on what the journalists do and how they can support journalists, I think it will go a long way to reduce the violence (Int 1).

DISCUSSION OF RESULTS

This study provides evidence to guarantee the development of a key component of rural and peri-urban media: the human resource. This study is also relevant considering the ongoing push for gender awareness in newsrooms (Asuman & Moodley 2023). Adhikary and Pant (2016) state that the main actors who engage in ensuring the safety of journalists comprise international organisations, state and political leaders, civil society organisations and academia, media organisations, as well as professional bodies and journalists' unions. On another level, the work of academia is key in focusing attention on the safety issues affecting journalists and by providing training and relief (Adhikary & Pant 2016). To provide empirical support for action, a study of this kind is crucial.

Most of the female journalists interviewed self-censor as a safety measure. In rural and peri-urban settings, which are also conflict-prone, the study revealed that female journalists tend to not delve into subjects relating to conflict, elections, chieftaincy, and other ethnically related matters, similar to what was reported by Asuman and Moodley (2023) that radio in Northern Ghana rarely had women as on-air news personalities because of the safety concerns.

Exposure to safety breaches could have similar implications in various contexts, and could deprive a nation of quality journalism. Suraj (2021) argues that Nigerian journalists, in response to the Nigerian Press Council Act (2018) and online government surveillance, self-censor by not publishing stories that could be seen as critical of the government and avoid controversial online activities.

International Media Support (IMS) (2022) recommends a three-item toolkit for ensuring the safety of journalists, including setting up plans to monitor safety attacks; improved dialogue that leads to international support, and collaboration between governments, media and security forces; and more appropriate legal frameworks including initiatives that help secure financial and legal counsel for journalists who need them, and practical steps such as setting up 24/7 hotlines, safe houses and protective equipment for journalists. It is expected that by developing policies, media organisations, whether located in urban, peri-urban or rural towns, tailor these recommendations.

According to Delorie (2012), when reporting on armed conflicts, natural disasters, or tense situations, journalists frequently operate in hazardous conditions. Training could offer the necessary tools for journalists to evaluate the risks, avoid dangers, handle emergencies successfully, and lower the chance of physical harm. As risks in journalism change, ongoing training remains essential to ensure journalists' safety and uphold information freedom. Specialised courses that prepare journalists for hostile environments and teach them survival skills, kidnap avoidance, as well as strategies for handling captivity should also be considered for journalists in conflict zones.

Journalists serve as the pillars of democracy, shedding light on crucial issues and providing the public with accurate information. However, the rise of misinformation and poor reporting pose a significant threat to journalists, leading to potential attacks and endangering their safety (Egelhofer & Lecheler 2019). Thus, the suggestion by female journalists practicing in rural and peri-urban media that fact checking is crucial in stemming attacks is prudent. Some of the journalists had benefited from such training and were aware of the power of evidence-based reporting to silence potential assailants.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Safety training is vital in ensuring the safety of female journalists. It is therefore not surprising that almost all the participants suggested journalistic training to include personal safety measures, such as situational awareness, travel safety, and how to handle dangerous situations while reporting. As journalists are trained on how to sense and manage risks, it is also recommended that training includes how journalists can cope with trauma, stress, and emotional challenges that arise from their work. Lastly, it is recommended that safety training must target media owners and must include ethical reporting in conflict zones, which necessitate the use of protective gear, adherence to international laws, and protocols for dealing with armed actors.

REFERENCES

Adhikary, N.M. & Pant, L.D. 2016. Supporting safety of journalists in Nepal. UNESCO Publishing. [ Links ]

Adjin-Tettey, T.D. 2023. Safety of journalists in Ghana. In: The State of the Ghanaian Media Report. Accra: University of Ghana Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003298977-38 [ Links ]

Adjin-Tettey, T.D. & Braimah, S. 2023. Assessing safety of journalism practice in Ghana: Key stakeholders' perspectives. Cogent Social Sciences 9(1): 2225836. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2225836 [ Links ]

Andreotti, O., Muižnieks, N., McGonagle, T., Parmar, S., Çalı, B., Voorhoof, D., Akdeniz, Y., Altıparmak, K., Sarikakis, K., White, A., Siapera, E. & Haski, P. 2015. Journalism at risk: Threats, challenges and perspectives. Council of Europe. [ Links ]

Asuman, M.K.A. & Moodley, S. 2023. Women's participation in indigenous language media: An analysis of five community radio stations in Northern Ghana. In: Mpofu, P., Fadipe, I.A. & Tshabangu, T. (eds). African Language Media. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Boateng, K.J.A. & Buatsi, R. 2022. Face to face with COVID-19: Experiences of Ghanaian frontline journalists infected with the virus. In: Dralega, C.A. & Napakol, A. (eds). Health crises and media discourses in Sub-Saharan Africa. Cham: Springer. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-95100-9_9 [ Links ]

Bodine, A. 2022. For Ghanaian journalists, physical attacks and legal battles are on the rise. Available at: https://akademie.dw.com/en/for-ghanaian-journalists-safety-is-a-growing-concern/a-62279317 [Accessed on 18 January 2023]. [ Links ]

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2): 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [ Links ]

Delorie, C. 2012. Safety guide for journalists: A handbook for reporters in high-risk environments. UNESCO Digital Library. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000243986 [Accessed on 2 February 2023]. [ Links ]

Egelhofer, J.L. & Lecheler, S. 2019. Fake news as a two-dimensional phenomenon: A framework and research agenda. Annals of the International Communication Association 43(2), 97-116. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2019.1602782 [ Links ]

H0iby, M. & Ottosen, R. 2019. Journalism under pressure in conflict zones: A study of journalists and editors in seven countries. Media, War & Conflict: 12(1): 69-86. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750635217728092 [ Links ]

International Women's Media Foundation. 2018. Attacks and harassment: The impact on female journalists and their reporting. International Women's Media Foundation & Troll Busters. [ Links ]

James, B. 2002. Press freedom: safety of journalists and impunity. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000248297 [Accessed on 27 July 2023]. [ Links ]

Lewis, S.C., Zamith, R. & Coddington, M. 2020. Online harassment and its implications for the journalist-audience relationship. Digital Journalism 8(8): 1047-1067. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2020.1811743 [ Links ]

North, L. 2016. Damaging and daunting: female journalists' experiences of sexual harassment in the newsroom. Feminist Media Studies 16(3): 495-510. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2015.1105275. [ Links ]

Nyarko, J. & Akpojivi, U. 2017. Intimidation, assault, and violence against media practitioners in Ghana: considering provocation. SAGE open 7(1): 2158244017697165. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017697165 [ Links ]

Post, S. & Kepplinger, H.M. 2019. Coping with audience hostility. How journalists' experiences of audience hostility influence their editorial decisions. Journalism Studies 20(16): 2422-2442. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2019.1599725 [ Links ]

Slavtcheva-Petkova, V., Ramaprasad, J., Springer, N., Hughes, S., Hanitzsch, T., Hamada, B. & Steindl, N. 2022. Conceptualizing journalists' safety around the globe. Digital Journalism 11(7): 1211-1229. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2022.2162429 [ Links ]

Suraj, O.A. 2020. Online surveillance and the repressive Press Council Bill 2018: A two-pronged approach to media self-censorship in Nigeria. In: Grøndahl, A., Larsen, L. Fadnes, I. & Krøvel, R. (eds). Journalist safety and self-censorship. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367810139-6 [ Links ]

UNESCO. 2020. Online violence against women journalists: A global snapshot of incidence and impacts. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000375136 [Accessed on 27 July 2023]. [ Links ]

UNESCO. 2022. Journalism is a public good: World trends in freedom of expression and media development. Global Report 2021/2022. Paris, France: UNESCO. [ Links ]

White, A. 2009. Getting the balance right: gender equality in journalism. Available at: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0018/001807/180707e.pdf [Accessed on 27 July 2023]. [ Links ]

Date submitted: 12 September 2023

Date accepted: 9 October 2023

Date published: 15 December 2023