Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Communitas

versión On-line ISSN 2415-0525

versión impresa ISSN 1023-0556

Communitas (Bloemfontein. Online) vol.27 Bloemfontein 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/24150525/comm.v27.12

ARTICLES

https://dx.doi.org/10.18820/24150525/comm.v27.12

Towards a communication strategy implementation framework for Higher Education Institutions in Lesotho

Relebohile Letlatsa

Department of English, National University of Lesotho, Maseru, Lesotho. Email : rmletlatsa@nul.ls; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4362-1731

ABSTRACT

This article reports on the findings of a research study of three Higher Education Institutions (HEI) in Lesotho on the communication strategies they use to engage with internal and external stakeholders to implement their institutional strategies. A mixed-method research approach was followed, and a sample of three HEIs and their internal and external stakeholders was identified through a multidimensional sampling strategy. Triangulation included a survey among stakeholders, interviews with senior managers, and a content analysis of strategic plans. Statistical analysis was conducted on quantitative data, thematic analysis on qualitative data from interviews and open-ended survey items, and content analysis on strategic plans. Leximancer software was used for the qualitative data analysis. Results indicate the importance for the institutions to develop communication strategies; align institutional strategies with organisational culture; identify legitimate and strategic stakeholders; and use fitting communication platforms to disseminate information to all stakeholders.

Keywords: communication strategy, stakeholder engagement, strategy implementation, higher education institutions

INTRODUCTION

Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) in Sub-Saharan Africa seem to experience similar challenges with regard to stakeholders, which include a lack of stakeholder participation in developing and implementing strategic plans (Bender 2008: 84). Through goals and objectives, the institutions integrate stakeholders into institutional structures and funding to enhance accessibility, relevance and quality assurance (Council on Higher Education 2013). The HEIs further face communication challenges characterised by poor communication and collaboration levels across academic disciplines (National University of Lesotho n.d.: 5). There is generally a lack of teamwork, which consequently manifests in an organisational culture that affects the implementation of strategic plans. Despite all these common challenges, HEIs do have effective strategic plans in operation (National University of Lesotho n.d.: 5).

The purpose of the study was to assess the extent to which HEIs use a communication strategy to implement their strategic plans. Emphasis is placed on communicating the goals and objectives to stakeholders (internal and external) to enhance the implementation of the strategic plans. The stakeholders of HEIs in Lesotho include managers, employees and students of the HEIs, the government, the media, parents, parastatals, alumni, donors and the community. The research attempts to determine if in order for stakeholders to process information effectively they have to understand the organisation's decision-making rationale and strategy implementation imperatives (Sutcliffe 2001: 203).

A need exists for a clear articulation of how managers should manage the implementation of strategic plans. A well-developed communication strategy aimed at improving all communication platforms is needed to address this problem. Columbine (2007: 17) emphasises that communicators have an important role to play in guiding businesses to maintain healthy relationships with stakeholders and manage corporate reputation and brand positioning in their respective markets. This implies that organisations must involve stakeholders in activities that concern the implementation of strategic plans.

The link between strategy and the actual implementation process has always been tenuous (Argenti et al. 2005: 83). Top consulting companies have employed countless people with MBAs to develop strategies for their clients. Academics at top universities have developed frameworks to guide improved strategy development for top companies. A handful of academics and communication consultants at public relations companies have struggled primarily with the implementation of strategic plans where it matters most: stakeholder communication (Argenti et al. 2005: 83). Additionally, research has shown that "lack of implementation has been one of the major failings in strategic planning" and most organisations' strategic plans "gather dust rather than results" (Kenny 2005: 191). The author has observed that while stakeholders at the HEIs in Lesotho are aware of the importance of strategic plans, the concern rests with ineffective implementation.

The research employed a mixed-method research approach to address the research question and used available literature to collect data to inform the analysis. Internal and external stakeholders of three HEIs in Lesotho participated through face-to-face interviews and questionnaires. In addition, content analyses were done on the strategic plans of the different institutions to determine how strategy implementation is communicated to stakeholders.

In addition, the research aims to contribute to the existing body of knowledge about the implementation of strategic plans by proposing a communication strategy implementation framework for the HEIs to implement strategy more effectively in the higher education environment.

OVERVIEW OF LITERATURE

Organisations formulate strategic plans to establish and develop their operational actions. Argenti et al. (2005: 83) attest that greater effort is expended in formulating rather than implementing strategic plans, whereas strategic planning is an institutionalised concept of a common process across organisations. As opposed to implementation process, strategic planning employs common formats and purposes as well as strategy tools and techniques. Research also indicates that the lack of implementation becomes more noticeable when it has to be communicated (Argenti et al. 2005: 83). It is, therefore, imperative for a HEI to have a communication strategy in place that engages stakeholders for effective implementation of its strategic plan, while at the same time positioning and promoting the institution.

Communication strategy

Communication strategy mainly focuses on an organisation's way of managing its strategy. Steyn and Puth (2000: 52) posit that communication strategy (referred to as institutional communication strategy) determines a guideline (framework) against which to test the prevailing communication decisions. "The corporate communication strategy is the framework for the strategic communication plan and the operational communication plans or programmes" (Steyn & Puth 2000: 52). It establishes the communication function to be communicated to support the organisation and its strategies.

Strategic formulation and planning are key to the formulation of a communication strategy; hence, the two should mirror each other since the communication strategy paves the way to a communication plan and generates a collaboration between an organisation and the communication strategy. Organisational effectiveness is therefore enhanced by the support the organisation gets from organisational communication as it responds to the organisational needs (Steyn & Puth 2000: 53).

Stakeholder engagement

As has been mentioned, a communication strategy focuses on frameworks that are used by institutions for the strategic and operational plans of institutions. One cannot discuss this concept without a mention of stakeholder engagement strategy. Institutions use stakeholder engagement strategies to engage their stakeholders to enhance the implementation of institutional strategic plans. Morsing and Schultz (2006: 325) argue that 50% of companies practice one-way communication to inform the stakeholders, and 35% practice two-way communication that builds on the processes of sense-giving and sense-making. Organisations make use of three strategies to involve stakeholders, namely stakeholder information strategy; stakeholder response strategy; and stakeholder engagement strategy (Morsing & Schultz 2006: 325).

Stakeholder engagement strategy involves organisations and their stakeholders in persuading each other for a change. The two parties are involved in a symmetric communication model, a process of sense-making and sense-giving. This strategy allows for concurrent negotiation with the stakeholders. The organisation ensures that it keeps abreast with the stakeholders' expectations, as well as its possible influence on those expectations and of the influence the expectations will have on the organisation (Morsing & Schultz 2006: 327); hence, the need to engage stakeholders.

Organisations use various strategies to engage their stakeholders for effective implementation of their communication strategies. As a result, organisations should be mindful of principles that underpin stakeholder engagement strategies. Friedman and Miles (2006: 151) propose that there is a need for the organisations to be aware that stakeholders have diverse interests, as organisations should monitor the concerns that emanate from all legitimate stakeholders. Secondly, managers should allow a two-way dialogue between the organisation and stakeholders; this will give room for stakeholders to air their concerns and views, and any risks foreseen because of their engagement with the organisation.

Thirdly, managers should note that the extent to which stakeholders are involved in the organisation differs. In some cases, stakeholders formally get involved through annual general meetings or are represented by unions or through informal contacts, such as direct contact, advertising and media releases.

Fourth, Friedman and Miles (2006: 151) emphasise that the two forms of contact should be treated with caution by the organisation, more especially the stakeholders who have limited capacity to interpret complex circumstances. A balance in risk and rewards should be considered between the different stakeholders, as well as to ensure a balance in the distribution of benefits.

The fifth principle encourages cooperation between the stakeholders and the organisation to minimise unwanted externalities to the organisational premises, while the sixth principle discourages activities that might jeopardise human rights. Lastly, managers should recognise the potential of their own conflicts, conflicts that may exist between the organisation and legitimate stakeholders; and the need to resolve such conflicts through open communication (Friedman & Miles 2006: 151).

Consequent to the principles, organisations must clearly distinct between internal and external stakeholders, which requires a thorough study of the organisational environment. Environmental analysis enables the organisation to determine who to engage with in the decision-making and to know what factors can affect the organisation's freedom of action (Van Riel & Fombrun 2007: 49).

Van Riel and Fombrun (2007: 49) suggest that institutional managers should inform the stakeholders about the intent of the new strategy and its implications for the stakeholders' daily jobs and careers, as well as on the future of the organisation. Organisations should motivate stakeholders through emphasising the availability of opportunities that a new strategy provides and should provide a clear indication of the administration of the expected implications that it will have on their work whilst the strategy is implemented.

Puth (2002: 202) and Kaplan and Norton (2001: 2-8) put forth a consistent pattern to follow in achieving strategic alignment and focus in order to enhance the planning, implementation, review and monitoring of institutional strategic plans. This pattern is formed according to the following five common principles: translate strategy into operational terms; align the organisation to the strategy; make strategy everyone's everyday job; make strategy a continual process; and mobilise change through strategic leadership.

Additionally, stakeholder engagement strategy is effected through an alignment of communication strategy development with a two-way communication measure between the internal and external environments, for it is an efficient method towards the excellent implementation of the strategy (Chanda & Shen 2009: 7). Two-way symmetrical communication comes as a go-between between the organisation and its environment as it balances the interests of the two (Grunig et al. 2002:15).

According to the excellence theory, through communication management, excellent institutions activate a two-way symmetrical communication process into practice to benefit both the stakeholders' and institution's interests and manages conflict between the two. This is how symmetrical practitioners maintain loyalty between their institutions and stakeholders.

Communication departments should have a strategic origin rather than a historic origin. Excellent communication departments have the following qualities (Grunig et al. 2006: 53):

♦ participative rather than authoritarian institutional cultures

♦ a symmetrical system of internal communication

♦ organic rather than mechanical structures

♦ programmes to equalise opportunities for men and women and minorities

♦ high job satisfaction among employees.

Excellent institutions should therefore adopt the following drivers for strategy implementation to enhance effective implementation of their strategic plans.

Drivers for strategy implementation

Institutional management must make sure that they take note of the social and environmental aspects in the organisation for the effective implementation of the institutional strategy. Consensus within both internal and external environments should be reached to secure the successful implementation of the strategy. Cronjé (2005: 178) emphasises that to fail in taking the external stakeholders on board in the implementation of strategy will result in jeopardising the strategy implementation because the stakeholders may have the potential to hinder or delay key elements of the strategy.

Firstly, Cronjé (2005: 178) maintains that in any organisation there has to be a leader with a vision for the organisation and who is willing to assist the organisation in realising the vision in contributing to the successful implementation of the strategy. For the purpose of this research, the leader will be addressed as the manager since they both refer to deciding what needs to be done, and forming networks of people in whose relationships agenda can be accomplished (Kotter 2008: 5). Cronjé (2005: 178) further attests that "a critical element of strategic success is the ability of top management, through superior leadership and management skills, to respond swiftly to changes in the global business environment".

Additionally, Cronjé (2005: 178) argues that top management should ensure proper implementation of organisational strategy by influencing the behaviour of their stakeholders. Cronjé (2005:178) stipulates the following major responsibilities of managers in implementing the strategy:

♦ managers should develop an open strategic direction

♦ the vision and strategic direction should be communicated to all stakeholders

♦ they should inspire and motivate stakeholders

♦ they should develop and maintain organisational culture that will be effective to the organisation

♦ managers should ensure proper incorporation of good corporate governance principles into the strategies and operations.

The above drivers for strategy implementation are worth taking note of for HEIs to enhance engagement with their stakeholders for effective implementation of their strategic plans. The institutions are encouraged to practice an open communication system to allow for effective stakeholder participation. Again, institutional visions need to be well communicated to all stakeholders and good corporate governance principles should be incorporated into the institutional strategies.

Some organisations integrate communication functions under one executive (Grunig et al. 2006: 35), as is the case with HEIs in Lesotho, except the National University of Lesotho, where communication is managed by the Registrar's office. They overlook the integral role that can be played by communication executives at the strategy-making tables (Falkheimer et al. 2017: 97). If the institution can develop a suitable motivation system to persuade the stakeholders' participation, this may assist in developing an organisational culture that is conducive for effective implementation of institutional strategic plans.

Institutional culture

Institutional culture is referred to as a group of important, though not written down, assumptions, beliefs, behavioural norms and values shared by members in the organisation (Cronjé 2005: 184). It is a system that determines how things are done in a specific organisation, which is evident through the organisation's stories, legends and traditions, as well as its techniques to approach problems and make decisions, its policies and its relationships with stakeholders.

Organisational culture is believed to tie together members of the organisation and guides the actions of the members. Culture is one aspect that needs attention as it is believed to be much easier to create and maintain in smaller than in bigger organisations. Moreover, organisational culture can be considered valuable or an obstacle towards the successful implementation of the strategy. This can be apparent if the beliefs, visions and objectives of an organisation seem to be on par with the organisational culture; then culture becomes valuable to the organisation and simplifies the implementation of the strategy (Cronjé 2005: 184).

Therefore, managers are responsible for creating institutional culture and should consider the values, believes and attitudes of the stakeholders. Managers are normally vested in the culture that is instilled by the founders of the organisation, and as the organisation recruits more stakeholders, they join in the sharing of the existing culture. Cronjé (2005: 185) introduces four categories of organisational culture, namely strong, weak, unhealthy, and adaptive.

It is worth noting that organisations do not have a homogeneous culture (Cronjé 2005: 185). They are divided into different subdivisions which operate according to their individual culture, beliefs, values and attitudes. It is important to match the existing culture with a strategy in order to promote internal stakeholder identification with the organisation's vision and mission (Cronjé 2005: 186).

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

In order to assess the extent to which HEIs in Lesotho use communication strategy to engage stakeholders for the effective implementation of a strategic plan, the author used a mixed-method research approach. Creswell and Plano Clark (2011: 256) define this as a mix of qualitative means of collecting words and a quantitative way of collecting numbers in conducting research. The use of multiple techniques enables validity of the results more than if it was only one technique (Myers & Powers 2014: 300). As a result, this study utilised exploratory and descriptive designs as it attempted to explore and describe the implementation of communication strategy to engage the stakeholders for the effective implementation of the strategic plans of the HEIs.

Mixed-method research approach

Data was concurrently collected and analysed, and later merged and interpreted. The research conclusions were based on both qualitative and quantitative methods, and treated as a whole (Creswell 2014: 4).

A convergent design was used to collect and analyse the data. The data analysis per strand was done independent of each other, while the interpretation of the data results was merged. The key reason behind the choice of the convergent design was to enable triangulation of the results by comparing and contrasting the qualitative and quantitative results (Bergman 2008: 4).

Since the author was interested in synthesising the information obtained, different individuals from different levels of the sample were used. In this case, the questionnaires were disseminated to the internal and external stakeholders, while the interviews were carried out with senior management. It was of interest to the author to corroborate the findings; hence, the questionnaire was designed as a combination of the qualitative and quantitative strands, and as a result was disseminated to the same internal and external stakeholders.

Both the qualitative and quantitative samples were conducted on different sample sizes of participants and respondents. The number of members of the senior management (interviewees) were fewer than the number of stakeholders (questionnaires). The aim was to qualitatively apply an in-depth exploration and to enable a severe quantitative study of the research topic to allow for generalisation of the findings to the rest of the HEIs in Lesotho.

The items in the questionnaires and the interviews were designed to collect data concurrently. The items addressed the same concepts as those mentioned in the research question and subsequently enabled the merging of the questionnaire and interview databases. To add, since the open-ended and closed-ended questions from the questionnaires were administered concurrently, the results from the open-ended questions were used to validate those from the closed-ended questions.

Leedy and Ormrod (2014:269) write that the mixed-method research approach enables researchers to generalise the results of the sample to the overall population and as a result assists in establishing the credibility of the research. There is an allowance of greater diversity of ideas to inform the research. Moreover, the mixed-method research approach enables researchers to maintain focus, as the qualitative method can be used for one aspect and the quantitative for another aspect of the research. Heyvaert et al. (2013: 303) argue that when using this approach, researchers get an opportunity to give a clear justification for mixing qualitative and quantitative approaches; this makes an explicit rationale for having a thoughtful decision-making process concerning the design and implementation of the study.

The three HEIs in Lesotho and their stakeholders were studied to encourage understanding of a communication strategy to assist the implementation of the strategic plan. The study explored and described areas within the institutions where it was not clear if there was information with regard to attitudes, trends, and needs that were applicable to the units of analysis. Therefore, the National University of Lesotho (NUL), Lesotho Agricultural College (LAC) and Lerotholi Polytechnic's (LP) strategic plans, interviews and questionnaires were analysed to assess the degree to which the stakeholders were engaged in the communication strategy for effective implementation of the strategic plans.

The author was mindful of the disadvantages the mixed-method research design may have on studies that use this approach. Myers and Powers (2014: 313) write that despite the common characteristic that makes it time consuming, studies conducted using this method may not be published in the state of a mixed-method design. The data collection and analysis of such articles may appear in two phases in separate manuscripts of qualitative and qualitative studies.

Target population

The target population included in this research is senior management, middle management, other employees of the institutions and students' representation as the internal stakeholders; alumni, industry, parents, the media, funders and the ministry of education (the government) were sampled as external stakeholders. Therefore, the research generalised the results to the population of research.

Sampling strategy

Of the eight public HEIs in Lesotho, data was collected from NUL, LAC, and LP (and the Centre for Accounting Studies as the pilot study) based on the knowledge of the population, its elements and purpose of research. The focus was based on both the internal and external stakeholders of the three institutions. As one of the crucial groups of internal stakeholders, students had to be excluded from the research because the survey was conducted at the beginning of the academic year, when students had not yet elected their student representation. Nonetheless, the author targeted the outgoing Student Representative Council (SRC) members. However, a few of the remaining outgoing SRC members were not available.

Probability and purposive sampling were used to achieve the representativeness of the internal and external stakeholders of the public HEIs on a broader scope of the HEIs. The selection was based on the author's knowledge of the variety of the institutions' stakeholders, together with their location.

Probability sampling was applied on quantitative strands of the research study and the HEIs were clustered into private and public. Since the focus was on the public institutions, this cluster was stratified into four HEIs based on their size. Two HEIs were categorised as the biggest in Lesotho while the other two represented the smallest. The three HEIs were stratified into internal and external stakeholders. The internal stakeholders were purposively sampled into members of senior management, employees, and students' representation (SRC) of the HEIs. Employees, senior management and students' representation of the HEIs formed the target population. While the external stakeholders' selection was based on the heterogeneous sampling as the media, parents, the government, alumni, industry and funders were surveyed in order to provide the utmost variation of data (Saunders et al. 2012: 287). Most elements of the sample for external stakeholders were easily identifiable, though the numeration was almost impossible (Babbie 2007).

Pilot study

To refine the data collecting instrument, namely the questionnaire, so that respondents could attempt the questions without problems, and no problems would be incurred in recording data, the author pilot-tested the questionnaire with the CAS prior to using it (Saunders et al. 2012: 451). Another reason a pilot test was run was to enable the assessment of the validity and possible reliability of the data that would be collected through both the questionnaire and interviews since the semi-structured interview questions were derived from the questionnaire. The author then followed Bryman and Bell's (2010) proposition as adapted by Saunders et al. (2012: 452) to pilot test the questionnaire, whereby time was taken to complete a questionnaire and its clarity was taken into consideration.

In order to create replicable and valid interpretations of the research findings, content analysis of strategic plans and responses to open-ended questions for HEIs in Lesotho was applied. Themes were deductively generated from the content of those documents. During this process, the capture of the qualitative richness of the phenomenon was ensured, as this was of assistance to the interpretation and presentation of the research.

The level of approach for content analysis was on words, key phrases and strings of words, at the same time deciding on the number of concepts to code. Coding was done to illustrate occurrence, frequency and contextual similarity. All meaningful data was coded to allow for generalisation of the content (Babbie 2007); thus, the use of Leximancer to analyse the strategic plans enhanced the exploration of instances that related to the coded concepts. Furthermore, content analysis was used at the sentence level. Sentences within which the themes appeared were captured to complement the co-occurrence of the themes and phrases that were captured in the conceptual maps.

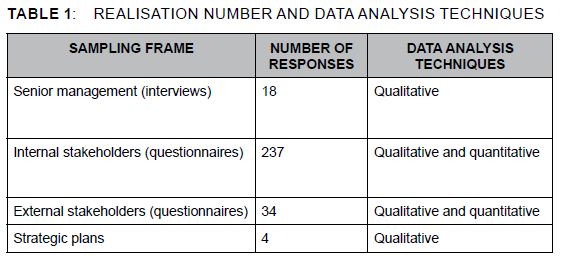

Table 1 illustrates the number of questionnaires, interviews and strategic plans realised.

Quantitative data analysis

The author categorised data into meaningful and relevant categories in spreadsheets. Categories first took the form of descriptive data as there were no numerical values attached to them. Though they could not add any numerical value, they were still counted as they were listed in the spreadsheet; in this case the author was able to determine which category had the highest numbers. In cases where data variables allowed for two categories, then dichotomous data was formulated. Rating and scaling questions called for ranked data. Besides categorical data, the author made use of numerical data to determine positions of data value. Numerical data was further divided into interval data where the difference between two data values was detected in one variable. To determine the numerical values of the data, SPSS was used. SPSS was further used to determine the relationships between the variables. A Chi-square (x2) test was used to determine whether the relationship exists between two nominal variables (Saunders et al. 2012: 514) based on the cross-tabulation of the two variables. Where there was a relationship, the Chi-square test further established whether the relationship was dependent or independent. In addition, the Chi-square value obtained determined its statistical significance.

Qualitative data analysis

The data was analysed qualitatively to maintain consistency between the qualitative data collection and its analysis. The author employed CAQDAS: Leximancer to analyse the qualitative data and SPSS for quantitative data. The qualitative data collected from the face-to-face interviews and the open-ended questions from the questionnaires were analysed in the following ways. First, the author prepared all data that was captured as a result of open-ended questions and interviews, and converted it from its oral (audio-recorded) or written form as a word-processed text.

For the qualitative data gathered from the open-ended questions, the author read the sets of answers from both the internal and external stakeholders. The in-depth reading enabled the identification of codes in order to generate an index of terms that helped the author to interpret and theorise with regard to the collected data (Bryman & Bell 2014: 337). The author went on to draw connections between the concepts and categories developed. The development of the categories was made from the collected data and literature, and was underpinned by the research question (Saunders et al. 2012: 557).

The content analysis was manually applied (without the help of software) to the open-ended questions of the questionnaires. For this data set, the author developed a categorisation matrix and coded the data according to the structured categories (Elo & Kyngäs 2008: 111). All data aspects that fitted into the categories were categorised accordingly and those that did not fit were categorised under the concept other.

Leximancer thematic analysis

The researcher used Leximancer to improve the validity by feeding transcribed text into the programme for coding. Themes were formulated through automated coding. In this case, content analysis was used to analyse the concepts derived from the interview transcriptions. The programme also analysed the relationships between the identified concepts in order to measure co-occurrence of such concepts (Leximancer 2011: 9).

DISCUSSION OF RESEARCH FINDINGS

The primary research question was, "To what extent do the HEIs in Lesotho use a communication strategy to engage stakeholders in the implementation of their institutional strategic plans?".

Firstly, it was found that HEIs' stakeholders receive information that is rarely specific to institutional strategic plans. The Office of the Registrar is responsible for communication activities, except for NUL, which has a Public Affairs and Industrial Relations office. Secondly, HEIs engage their stakeholders to a certain extend for the planning, implementation, monitoring and review of their strategic plans. Information is also disseminated similarly to all types of stakeholders; however, academic staff participate more in strategic planning activities than non-academic staff. There is no statistically significant association between the length of affiliation of the external stakeholders and their knowledge about their engagement in the strategic planning activities.

Despite efforts by HEIs towards information dissemination and stakeholder engagement, the research revealed that institutional culture negatively influences the implementation of the communication strategy. In most cases HEIs management practice a top-down and non-engaging form of communication. They disregard stakeholders' views, withhold information from them, and use inappropriate platforms of communication. Moreover, long-term serving employees are resistant to the ideas of newly employed personnel.

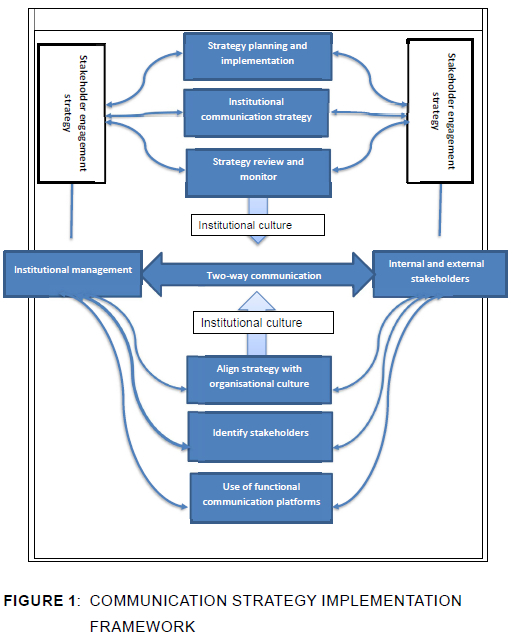

To address the problem statement formulated at the start of the research, a communication strategy implementation framework (Figure 1) was developed to help HEIs engage their stakeholders to enhance the successful implementation of institutional strategic plans.

COMMUNICATION STRATEGY IMPLEMENTATION FRAMEWORK

As indicated in the proposed communication strategy implementation framework (Figure 1), the HEIs are encouraged to practice this stakeholder engagement strategy to engage their stakeholders in the formulation, implementation, reviewing and monitoring of institutional strategic plans. Stakeholder engagement should not only be applied in these activities but should also be considered in the development of institutional communication strategy.

As the HEIs are large organisations, two-way symmetrical communication will not be possible for all institutions. The research suggests that the institutions develop institutional communication strategies accordingly. The institutions should ensure that they keep abreast of the stakeholders' expectations, along with the possible influence of the stakeholders' and institutions' expectations.

The research does not discard the stakeholder information strategy but proposes that HEIs apply both stakeholder information and stakeholder engagement strategies. Stakeholders can support or oppose the institutions' decisions, and consequently enhance mutual benefit through frequent dialogues. The latter, taking place between the HEIs and their stakeholders, encourages stakeholder engagement, which discourages autocracy wherein managerial decisions are made unilaterally. It also encourages open discussions and joint decisions.

It is further proposed that stakeholders be granted direct participation to contribute their views and provide inputs during facilitating, and before decisions are made. Stakeholders should be empowered during institutional decision-making.

The following steps are proposed for effective implementation of the communication strategy implementation framework:

1. The influence of institutional culture is inevitable in stakeholder engagement and the implementation of strategic plans. Thus, the HEIs should consider aligning the formulation and implementation of strategic plans with the institutional culture. In an institution, culture can enforce certain types of institutional growths or oppose some institutional values.

2. HEIs should know who their stakeholders are. It is proposed that they identify strategic and legitimate stakeholders, and that they maintain longterm relationships with them. Stakeholder identification is important because it is possible to have stakeholder values, needs, goals and objectives that differ from the institution's. Implications of strategic issues on institutions and stakeholders can be identified.

3. HEIs should review their communication platforms. They should establish functional and clear communication platforms to engage stakeholders. In addition to the existing platforms, the HEIs should incorporate more platforms into their communication system. The use of these platforms should be inclusive, regardless of the type of stakeholder or the length of affiliation with the institutions. Also, the HEIs should use the right communication platforms for the right type of message.

From the research findings, it was concluded that the institutions practice one-way/top-bottom communication to inform and engage the stakeholders in the implementation of their strategic plans. HEIs predominantly use memoranda, meetings and media platforms to convey information to the stakeholders. Two of these communication platforms, memoranda and the media, do not allow for immediate feedback, whereas meetings, which are convened at the most once in a month, allow HEIs' stakeholders to provide feedback to the management. This means that HEIs engage their stakeholders through a stakeholder information strategy instead of stakeholder engagement strategy.

In addition, institutional culture was found to be the most common factor to adversely influence institutional communication. It is a common practice for management to use top-bottom communication. Some of the information is not communicated to the stakeholders and management keeps it to themselves. The stakeholders, in return, develop a negative attitude towards the management because they feel they are not engaged in the decision-making. This trait is mostly prevalent amongst the alumni, and long-service and long-affiliated stakeholders. It is concluded that there is no alignment between institutional culture and strategic plans.

It is generally concluded that HEIs in Lesotho are closed to external ideas; hence, they favour worldviews that practice asymmetrical communication. They place less value on excellent public relations and communication management. All the HEIs, except NUL, do not have public relations or communication units to manage internal and external communication. Offices of the Registrar directly deal with this function.

It was further found that the HEIs do not consider participative institutional cultures and do not realise their potential to produce a conducive environment for excellent communication (Dozier et al. 2013: 17). Therefore, the research proposes a communication strategy implementation framework (Figure 1) for HEIs in Lesotho to engage their stakeholders for effective implementation of their strategic plans. The HEIs are also encouraged to consider aligning their institutional strategy with their institutional culture; to identify legitimate stakeholders; and to use functional communication platforms.

CONCLUSION

The study was designed to assess how the HEIs use communication to engage their stakeholders in order to enhance the implementation of their strategic plans. The research inquiry, therefore, identified that the institutions engage the stakeholders using the stakeholder information strategy. The communication is still dominated by one-way communication.

Findings of this research contribute towards developing the body of knowledge of communication management and public relations in Sub-Saharan Africa, Lesotho in particular, by arguing that instead of using a stakeholder information strategy, the institutions should choose a stakeholder engagement strategy to achieve their goals and objectives. The institutions may also consider developing communication strategy.

The research also contributes to the discipline of communication management by complementing existing theory that a communication strategy is vital for stakeholder engagement towards the successful implementation of a strategic plan. The research further contributes to the field of academic institutions in Sub-Saharan Africa by proposing a communication strategy implementation framework (Figure 1) to prompt the management in the HEIs in Sub-Saharan Africa to adopt for implementation of their strategic plans.

In conclusion, blending communication strategy into the formulation and implementation of strategic plans remains under-researched. Future research should address how best communication strategy practitioners and strategic managers in HEIs could appreciate the value of communication strategy by explicitly inculcating it into the strategic management of their strategic plans.

REFERENCES

Argenti, P.A., Howell, R.A. & Beck, K.A. 2005. The strategic communication imperative. MIT Sloan management review 46(3): 83. [ Links ]

Babbie, E. 2007. The practice of social research. (Eleventh edition). Belmont: Thomson Learning. [ Links ]

Bender, G. 2008. Exploring conceptual models for community engagement at higher education institutions in South Africa: conversation. Perspectives in Education 26(1): 81-95. [ Links ]

Bryman, A. & Bell, E. 2014. Research methodology: business and management contexts. Cape Town: Oxford University Press Southern Africa. [ Links ]

Chanda, A. & Shen, J. 2009. HRM strategic integration and organisational performance. New Delhi: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9788132108269 [ Links ]

Council on Higher Education. 2013. Higher Education Strategic Plan 2013/14-2017/18. Maseru. [Online]. Available at: http://www.che.ac.ls/documents/HE%20Strategic%20Plan.pdf. [Accessed on 24 August 2021]. [ Links ]

Cronjé, S. 2005. The drivers of strategy implementation. In: Ehlers, T. & Lazenby, K. (eds). Strategic management: Southern African concepts and cases. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Dozier, D.M., Grunig, L.A. & Grunig, J.E. 2013. Manager's guide to excellence in public relations and communication management. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203811818 [ Links ]

Elo, S. & Kyngâs, H. 2008. The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of advanced nursing 62(1): 107-115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x [ Links ]

Falkheimer, J., Heide, M., Nothhaft, H., Von Platen, S., Simonsson, C. & Andersson, R. 2017. Is strategic communication too important to be left to communication professionals? Managers' and coworkers' attitudes towards strategic communication and communication professionals. Public Relations Review 43(1): 91-101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2016.10.011 [ Links ]

Grunig, J.E., Grunig, L.A. & Dozier, D.M. 2006. The excellence theory. In: Botan, C.H. & Hazleton, V. (eds). Public relations theory II. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Grunig, L., Grunig, J. & Dozier, D. 2002. Excellent organisations and effective organisations: a study of communication management in three countries. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Joffe, H. & Yardley, L. 2004. Content and thematic analysis. In: Marks, D.F. & Yardley, L. (eds). Research methods for clinical and health psychology. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Kaplan, R.S. & Norton, D.P. 2005. The office of strategy management. Strategic Finance 87(4): 8. [ Links ]

Kotter, J.P. 2008. Force for change: How leadership differs from management. New York: Simon and Schuster. [ Links ]

Leximancer. 2011. Leximancer manual version 4. [Online]. Available at: https://www.leximancer.com/site-media/lm/science/Leximancer_Manual_Version_4_0.pdf [Accessed on 20 August 2021]. [ Links ]

National University of Lesotho. n.d. National University of Lesotho strategic plan 2015-2020. Roma, Maseru: National University of Lesotho. [ Links ]

Puth, G. 2002. The communicating leader: the key to strategic alignment. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Saunders, M., Lewis, P. & Thornhill, A. 2012. Research methods for business students. Harlow: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Steyn, B. & Puth, G. 2000. Corporate communication strategy. Sandton: Heinemann. [ Links ]

Sutcliffe, K.M. 2001. Organizational environments and organizational information processing. In: Jablin, F.M. & Putnam, L.L. (eds). The new handbook of organizational communication: advances in theory, research, and methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Van Riel, C.B. & Fombrun, C.J. 2007. Essentials of corporate communication: implementing practices for effective reputation management. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203390931 [ Links ]

Date submitted: 10 September 2022

Date accepted: 07 November 2022

Date published: 8 December 2022