Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Communitas

versión On-line ISSN 2415-0525

versión impresa ISSN 1023-0556

Communitas (Bloemfontein. Online) vol.27 Bloemfontein 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/24150525/comm.v27.10

ARTICLES

https://dx.doi.org/10.18820/24150525/comm.v27.10

Strategic multi-stakeholder partnerships for achieving SDG 9 through the revival of South African township industries

Olebogeng SelebiI; Sandy Oupa MhlongoII

IDepartment of Business Management, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa. Email : olebogeng.selebi@up.ac.za (corresponding author); ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9934-8538

IIDepartment of Business Management, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa. Email : odzopa1972@gmail.com; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5696-4293

ABSTRACT

South Africa faces many socioeconomic ills which government cannot address on its own. Various stakeholders need to come together to address the issues of unemployment, poverty and inequality. Multi-stakeholder partnerships (MSPs) are broadly defined as participatory and collaborative forms of decision-making structures involving key stakeholders willing to cooperate with one another to attain set objectives. The United Nations' Sustainable Development Goal 17 (SDG 17) emphasises the importance of partnerships for achieving socioeconomic development. These partnerships cannot be successful without effective strategic communication. Thus, the purpose of this study was to explore the role of MSPs (SDG 17) in the revitalisation of job-creating industries in South African townships (SDG 9). Many industrial areas are forlorn and stranded following the withdrawal of the decentralised industrial policy. A generic qualitative study using semi-structured interviews was conducted in South Africa's Limpopo province. Twelve respondents participated and thematic analysis was used to analyse the data. The study found that despite the withdrawal of incentives and subsidies, township industries' occupancy rate is high, yet with little impact on job creation. The findings may assist policymakers in reviewing township industrial policies.

Keywords: Multi-stakeholder partnerships, strategic communication management, decentralised industrial policy, sustainable development goals, generic qualitative research, township economy

INTRODUCTION

One of the biggest challenges faced by the South African government is the creation of sustainable employment and growing the economy. High unemployment remains a challenge in the country despite the government's continued efforts to turn the tide. The United Nations (UN) aims to address such socioeconomic issues through the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Two of the 17 goals will form the focus of this study, namely Goal 9 (investments in industry, innovation and infrastructure) and Goal 17 (revitalising partnerships).

South Africa is a country facing many socioeconomic ills, including unemployment and slow economic growth. Industrialisation is an important solution to these issues. Industries in the former homelands/townships are currently in a dilapidated state due to the withdrawal of the "decentralisation industrial policy" and incentive schemes post-1994 (Phalatse 2000: 161). The decentralised industrial policy consisted of various packages and incentives, including providing infrastructure and subsidising labour costs, tax concessions, and low factory rentals (Naudé & McCoskey 2000). Many factories closed due to the withdrawal of these incentives.

Furthermore, Phalatse (2000: 161) maintains that industries in the former homelands or "Bantustans" were designed as sources of employment creation to eliminate poverty. In outlining the industrial development policy, Mosiane (2020: 2) highlighted how funding was made available to lure investors into building factories in and around South African townships and former homelands. The withdrawal of the decentralised industrial policy from homelands spelt the collapse of industries and lost jobs (Phalatse 2000: 161).

To underscore the point above, Mosiane (2020: 2) illustrated how the Rosslyn and Babelegi industrial zones, which served areas like Ga-Rankuwa, Winterveldt and Mabopane, were directly impacted by the rearrangement and review of the industrial incentives by the 1994 democratic government on their residents and the beneficiaries of industries that had to ultimately shut down their operations. Mosiane (2020: 3) argues that the termination of government-sponsored industries had a devastating effect on the employment levels in these areas.

Restoring these industries requires the collaboration of various stakeholders who communicate in a way, which will facilitate the goal of reindustrialisation. Gaining multi-stakeholder support through strategic communication is necessary for the achievement of socioeconomic development (Selebi 2019: 1). Public relations (also referred to as communication management) is described as "the art and social science of analysing trends, predicting their consequences, counselling organisations' leaders and implementing a planned programme of action, which will serve both the organisation and the public interest" (Skinner et al. 2013: 3). More importantly public relations is "a strategic communication process that builds mutually-beneficial relationships between organisations and other publics" (Skinner et al. 2013: 4). This statement emphasises the importance of effective strategic communication in the management of the multi-stakeholder partnerships (MSPs) that would be necessary for the re-industrialisation of South African townships.

In his 2021 Budget Speech, the former Minister of Finance, Tito Mboweni, "allocated R4 billion over the medium term to the township and rural enterprises, including blended initiatives", compared to R694 million in the previous financial year through the Township and Rural Entrepreneurship Programme (Daniel 2021). The SA Township and Rural Entrepreneurship Programme (TREP) was established in 2020 to financially boost the informal economy through the Small Enterprise Development Agency (Seda) and the Small Enterprise Finance Agency (Sefa) (Daniel 2021). This was viewed by some as an acknowledgement by the government that there was a dire need for reinvestment in townships whose businesses were estimated to account "for at least a third of total turnover generated by the country's formal business sector" (Daniel 2021). Thus, the purpose of this qualitative research was to determine the role of strategic MSPs (SDG 17) in fostering the reindustrialisation of South African townships (SDG 9). Strategic MSPs cannot function effectively without strategic communication. Compared to the Industrial Development Zones (IDZs), the former homelands/townships have been neglected when it comes to issues like job creation, poverty alleviation and addressing inequality (Department of Trade and Industry 2000).

The qualitative study used 12 semi-structured interviews involving participants from two public institutions in Limpopo - the municipality and a state-owned enterprise (SOE). The main research question the study sought to answer was, "How can strategic multi-stakeholder partnerships (MSPs) serve as a tool to revive dilapidated industrial parks surrounding townships in South Africa?". The following sub-questions were devised:

♦ Why is the use of strategic MSPs important in fostering the development of industries around townships in South Africa?

♦ What is the role of MSPs in revitalising industrial zones in townships?

♦ How does strategic communication facilitate the achievement of MSPs?

♦ Why is strategic communication important for reviving industrial zones in townships?

LITERATURE REVIEW

An overview of industrial development in and around townships

Prior to 1994, South Africa's spatial development was configured into four provinces and ten homelands or "Bantustan" systems (South African History Online 2021). The Bantustans or homelands systems came into existence in 1959 through the promulgation of the Apartheid Parliamentary Act, Act No. 46 of 1959, the Promotion of Bantu Self-Government (Jensen & Zenker 2015: 937-938). A township is an area that was designated for non-whites and designed without the modern town planning principles of proper land-use plans laid out for residential, commercial, or industrial developments without adequate infrastructure for basic services and amenities largely situated away from major economic hubs (Desai & Alex 2012: 790).

In total, there were ten homelands that were designated for blacks, four of which were the so-called "independent states" and six were self-governing territories. These were (Alexander 2018):

♦ Transkei (gained independence in 1976)

♦ Bophuthatswana (gained independence in 1977)

♦ Venda (gained independence in 1979)

♦ Ciskei (gained independence in 1981)

♦ Gazankulu (self-governing territory)

♦ KaNgwane (self-governing territory)

♦ KwaNdebele (self-governing territory)

♦ KwaZulu (self-governing territory)

♦ Lebowa (self-governing territory)

♦ QwaQwa (self-governing territory)

According to Jeffrey et al. (1978) homelands were configured along the following ethnic and tribal lines:

♦ Gazankulu for the Xitsonga people

♦ Venda for the Venda people

♦ Lebowa for the Pedi and Northern Ndebele groups

♦ Bophuthatswana for the Tswana people

♦ Ciskei and Transkei for the Xhosa-speaking group

According to South African activist Steve Biko (1978: 95), homelands or townships should not have been created at all because "these tribal cocoons called homelands are nothing else but sophisticated concentration camps where Black people are allowed to suffer peacefully". Essentially, to restrict the mobility of people from townships, a decentralised industrial policy was designed and introduced to undergird South Africa's economy (Naudé & McCoskey 2000).

The decentralised industrial policy

The genesis of the decentralisation industrial policy can be traced back to the 1930s, but it was introduced in earnest around the 1970s within the former homelands and further revised around 1982 to attract more industrial investors (Wellings & Black 1986: 2). According to Naudé and McCoskey (2000), a critical component of South Africa's economy was the decentralised industrial policy that was adopted to develop the homelands and townships by ensuring that industries had direct access to township or rural labour without workers having to relocate to urban centres. The decentralised industrial strategy was used as the instrument to spur and attract investors, which comprised of various incentives such as the provision of infrastructure, the subsidisation of labour costs, "tax concessions, provision of complete factories with low rentals, concessions on railway rates, establishment of fully planned industrial townships, assistance in provision of housing for white personnel" and lower wages (Beck 1968).

Naudé and McCoskey (2000) further argue that "since the withdrawal of these incentives, there has been extensive disinvestment from the South African township industries". This view is supported by Phalatse (2000: 161), who states that the withdrawal of the decentralisation industrial policy and incentives schemes post-1994 resulted in negative socio-economic maladies. Although each homeland or township had its unique ethnographic profile, one common denominator underpins all of them now - the collapse and disintegration of the industries (Phalatse 2000: 161).

However, not everyone supports the above views. According to Wellings and Black (1986: 2), the decentralised industrial policy was specifically "conceived as a means for stabilising the state's system of influx control providing alternatives to metropolitan employment within the Bantustan sub-economies". It is argued that the original intent of creating industries in townships through this policy had the racial intent of separating blacks from whites - thus, confining blacks to the homelands and townships away from economic centres (South African History Online 2021).

It appears that the unintended consequences of the decentralised industrial policy had some positive spin-offs in some townships, such as improved infrastructure, job opportunities and financial freedom, especially for previously unemployed women (Phalatse 2000: 161). Bhorat and Hodge (1999: 155) write that "between 1970 and 1995, formal employment increased by 18.6% or from about 7.5 million employees to 8.9 million". In a period of 25 years, from 1970 to 1995, people eligible to work (economically active population) grew by 57% from 8.1 million to 12.7 million (Bhorat & Hodge 1999). According to Statistics South Africa's (2011) October Household Surveys of between 1995 and 1998, "the total employment in the formal sector declined from 10.1 million to 9.4 million", which was a loss of approximately 700 000 jobs in two years.

National Industrial Policy Framework (NIPF)

The Department of Trade and Industry (2007) promulgated the National Industrial Policy Framework (NIPF) policy intervention to accelerate industrial development in South Africa. The NIPF provides strategic direction regarding matters relating to industrial development whose key objectives are the following (DTI 2007):

♦ to expedite and enlarge South Africa's trading portfolio into non-conventional commodities in both export and import markets;

♦ to fast-track industrialisation through migration into the knowledge economy; and

♦ to accelerate job creation through intensive labour-absorption and industrial mechanisms.

The NIPF has a much wider mandate than the decentralised industrial policy whose focus was homeland based through the provisioning of incentives to lure investors into creating jobs and stimulating township economies (Naudé & McCoskey 2000). While one of the NIPF aims is to identify and solve constraints that hamstring economic development on national level, township and rural economies continue to lag behind urban and metropolitan areas.

The role of MSPs in the re-industrialisation of townships

Stakeholders "are the individuals, groups, and organisations that can affect the firm's vision and mission, and are affected by the strategic outcomes achieved, and have enforceable claims on the firm's performance" (Kenny 2012: 44). MSPs are defined as "voluntary and collaborative relationships between various parties, both state and non-state, in which all participants agree to work together to achieve a common purpose or undertake a specific task and to share risks, responsibilities, resources, competencies and benefits" (United Nations General Assembly 2003).

Resuscitating township industries requires MSPs anchored in trust, transparency and commitment to a course. MSPs are the focus of SDG 17, as socioeconomic development (including township reindustrialisation) cannot be achieved without the input of various stakeholders. In addition, it will require a clear definition of the common purpose, roles, responsibilities, and accountability of each stakeholder. If MSPs represent the broader society it becomes easier for them to gain social legitimacy (Mulder 2016).

Strategic MSPs are increasingly becoming critical platforms for consideration in the sustainable developmental success of many companies, organisations, and communities (United Nations General Assembly 2003). In addition, trust is cited as one attribute that forms the basis for strategic MSPs - trust creates social legitimacy (Marr & Walker 2002: 6; Mulder 2016). Stakeholders must trust each other to communicate in a way that achieves the goals of the partnership. Therefore, communication management becomes a critical component for the development of trusting relationships (Grunig et al. 2002). Not only do organisations build relationships for their sake, but they should also strive for quality relationships with strategic constituencies (Grunig et al. 2002: 97), which become necessary in reviving industries in the former townships given the potential resistance that might arise from some quarters.

Selebi (2019: 7) writes that involving key stakeholders from the beginning of any plan takes the diverse expectations and needs of these stakeholders into account - thereby creating alignment and trust. Knowing your stakeholders and creating alignment between them will ensure that effective communication follows (Selebi 2019: 343-355).

Partnerships and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

The SDGs are premised on the principle of "leaving no one behind", by assembling MSPs consisting of government agencies, communities, businesses, the media, institutions of higher education, influential individuals, and local non-governmental organisations (NGOs) to ameliorate the livelihoods of the people in their respective countries by the year 2030 (United Nations Development Programme 2021). These SDGs are interlinked because success in one goal may have a domino effect on other goals. For example, revitalising the industries in the townships (SDG 9) may provide opportunities for employment creation and spur economic growth, which would alleviate inequality and poverty (SDG 10 and 1).

SDG 17 represents "Global Partnership for Sustainable Development", which acknowledges strategic MSPs critical for galvanising power to champion any sustainable development course to the benefit of affected communities (UNDP 2021). Pillay (2000) argues that the government is increasingly becoming aware of its shortcomings and the weaknesses of its policy interventions. The need for strategic MSPs to forge collaboration among various stakeholders for the successful implementation of development objectives is becoming more evident. Former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan said, "...by now we know that peace and prosperity cannot be achieved without partnerships involving governments, international organisations, the business community and civil society" (United Nations General Assembly 2003). Therefore, the revitalisation of township industries may not be equally achieved without creating strategic MSPs.

Botan and Hazelton (2006: 7) share the co-creational perspective that underscores the importance of relationships in co-creating meaning. This co-creational theory "sees publics as co-creators of meaning and communication as what makes it possible to agree on the shared meanings, interpretations and goals" (Botan & Hazelton 2006: 13). Thus, without partnerships, common purpose and shared meaning among various stakeholders for value co-creation, nothing can be achieved.

Communication theories in the context of MSPs

At the core of strategic MSPs are stakeholders with varying interests. To understand one another, they need to share a common purpose, exchange information and ideas, and agree on roles and responsibilities using communication. Without effective communication, MSPs are bound to collapse. Hill (1996) asserts that "at the root of many organisation and management problems are simple communication breakdowns". Success in public policy development and implementation requires multi-stakeholder co-operation and partnerships (Pillay 2000). This lends itself to the excellence theory of PR. To ensure the success of strategic MSPs (according to the excellence theory), these theoretical propositions need to be considered by the lead stakeholder (Botan & Hazelton 2006: 7):

♦ create a participative rather than an authoritative culture to ensure a multiplicity of views;

♦ create a symmetrical system of communication where everyone receives information equally;

♦ create organic rather than mechanical structures to ensure flexibility; and

♦ create programmes to ensure equality and equity among stakeholders.

In line with the above, Mitchell et al. (1997: 853) conceptualised the idea of the stakeholder salience theory, which is based on the attributes of power, legitimacy and urgency. This assists with stakeholder identification and salience amid various competing needs. Freeman (1984) and Drucker (1999) popularised the idea of stakeholder engagement during the 1980s and 1990s. In their view, stakeholder engagement can be defined as the systematic identification, analysis, planning, and implementation of actions designed to influence stakeholders (Drucker 1999; Freeman 1984). There is essentially no difference between the two perspectives, save for underscoring that before any MSPs can be constituted there is a need to identify, analyse, map and understand the role of each stakeholder.

Thus, MSPs can benefit from considering some of the principles of stakeholder theory as proposed by Freeman (2004: 230-231). In addition, power and legitimacy attributes underpinning stakeholder salience theory coupled with social intelligence are worth considering for the successful formation of MSPs.

METHODOLOGY

The purpose of the study was to explore how strategic MSPs could be used for the revitalisation of industries in townships to achieve sustainable development. In doing this, a generic qualitative research design using semi-structured interviews was deployed to explore insights and perspectives from the selected participants (Merriam 2009: 22). This design was the best strategy for answering the research questions and soliciting information-rich data regarding the participants' perceptions and experiences

(Plano Clark & Creswell 2015: 289).

The chosen geographical area for this study was South Africa's Limpopo province as it is home to three of the ten former homelands, namely Gazankulu, Lebowa and Venda, which had factories within their jurisdiction (Alexander 2018). All three former homelands have merged into the Limpopo province. Two townships with industries were sampled, namely Seshego and Nkowankowa.

Seshego is a township north-west of Polokwane in the Polokwane Local Municipality, as part of the Capricorn District Municipality. Until 1974, Seshego was the capital of the non-independent former homeland of Lebowa (McKenna 2021). According to Frith (2021b), Seshego has a population of 83 863 (Statistics South Africa 2011) and it has 76 factories.

Nkowankowa is a small township in the Greater Tzaneen Local Municipality, as part of the Mopani District Municipality. According to Frith (2021a), the township has a population of 24 484. It boasts 91 industrial factories manufacturing a range of goods from manikins and buses to electric bulbs, school furniture, and steel.

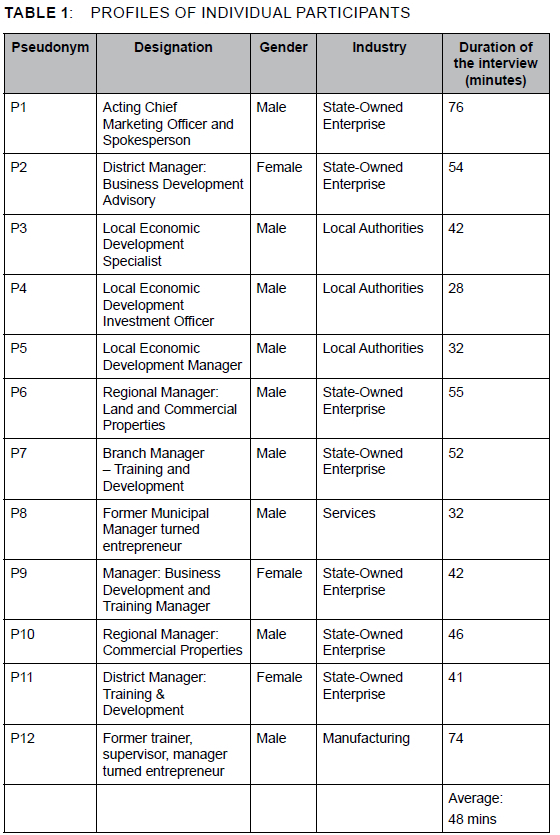

Twelve participants were interviewed. A stratified purposive sampling technique, with a homogeneous strategy, was chosen (Creswell 2012: 206-209; Polit & Beck 2012: 517-520). Table 1 below outlines the profiles of the individual participants:

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with all 12 participants. Three of the interviews were conducted face-to-face on the insistence of the participants in strict observance of Covid-19 protocols. The remaining respondents were interviewed through virtual platforms, such as MS Teams and Google Meets. The interviews' duration ranged from 28 minutes to 76 minutes, with the average being 48 minutes. Consent forms were sent with the discussion guide for participants' signatures prior to the scheduled interviews. The final part of the interview was generally preceded by expressing gratitude to the participants and establishing whether there was anything else they felt should have been added, as well as their overall impression of the study (Braun & Clarke 2013: 81-85).

Recordings were saved, transcribed and cross referenced with the participants for additional clarity and final comments (Louw 2014: 265-266). The Otter application was used to transcribe the recorded interviews.

Thematic analysis was used for this study. According to Braun and Clarke (2012), thematic analysis (TA) is a systematic approach and method for "identifying, organising and offering insight into patterns of meaning (themes) across a data set". Creswell (2012: 238) writes that although TA is systematic and methodical, it is an "iterative" and "non-linear process" of frequently cross-checking and referencing information during coding to "connect the dots" in order to form an overall picture of participants' collective experience. ATLAS.ti software was used to assist with coding and categorising the themes and sub-themes. Furthermore, a comprehensive master list was generated to provide more detail on the themes.

DISCUSSION OF FINDINGS

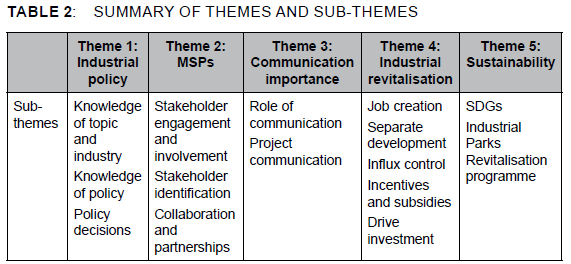

Five main themes with related sub-themes were constructed (see Table 2 below): industrial policy, MSPs, the importance of communication, industrial revitalisation, and sustainability.

Industrial policy

This theme focuses on the historical context of South Africa's decentralised industrial policy and establishes whether the participants are familiar with the policy. In addition, the authors explore if it was a prudent policy decision to withdraw the decentralised industrial policy.

Knowledge of the topic and industry

Nine of the 12 respondents have knowledge of the decentralised industrial policy. This is largely because their average combined years of experience was over 20 years.

Knowledge of the policy

On the knowledge and familiarity of the decentralised industrial policy, similar sentiments have been expressed by eight of the 12 participants on awareness:

... the industrialisation of the homelands began when... the government decided to decentralise the industries and the Gazankulu homeland was also picked as one of the areas that the decentralisation was going to take place ... - P12

Most of the participants were aware that the industries started in the 1970s to early 1980s. This is supported by Wellings and Black (1986: 2) that the decentralisation industrial policy can be traced back to the 1930s, but it was introduced in earnest around the 1970s within the former homelands and further revised around 1982 to attract more industrial investors.

Policy decision

Concerning the termination of the policy, eight out of 12 participants disagree with the government's decision to withdraw the policy. Two expressed mixed feelings and two supported the complete withdrawal of the policy:

For me it definitely not... it had its negatives and it had its positive side... it was supposed to be revised... and strengthened... - P9

Although there is no agreement in the literature on this view, there is consensus among the majority of the participants that the decision was not well-considered, with a proviso leaning more towards policy revision.

MSPs

The key finding revealed that all the participants agreed on the critical role MSPs play in revitalising the township industries. However, they differed slightly in their proposed approaches.

Stakeholder engagement and involvement

All the participants acknowledged that stakeholders not only have to be engaged, but they must also be involved in any project that directly or indirectly impacts them.

When you engage the multi-stakeholders you are ... bringing them into the process that they own the exercise - P4

One of the key findings on stakeholder engagement and involvement is that the revitalisation of township industries, without an effort to solicit the input of all stakeholders, would yield undesirable results.

Stakeholder identification

Stakeholder identification and mapping are key elements in MSPs and the stakeholder salience theory. Six out of the 12 participants agreed that stakeholder identification, as well as outlining clear roles and responsibilities for each stakeholder, is paramount:

I think it should start with the National Government Department of Trade and Industry coordinated with the provincial departments, then it comes down to the municipalities ... to the SOEs ... So, it cannot be a municipality thing alone, it cannot be provincial alone - P10

Mitchell et al. (1997: 853) validate this idea of stakeholder salience, which concerns itself with stakeholder identification.

Collaboration and partnerships

This sub-theme responds to the role MSPs can play in reviving township industries. Collaboration is the cornerstone of MSPs. This requires that time is invested in building and nurturing sound relationships with the core stakeholders. In addition, openness and transparency are at the core of relationship-building coupled with a collaborative approach that can create value and improve relationships to earn trust and minimise uncertainty and disruptions to any project (Pillay 2000):

... in terms of the multi-stakeholders, what needs to be done is to come up with a terms of reference that will outline role clarification because you can't be a stakeholder without a role. Your role must be defined in the terms of reference... If one of the stakeholders' role is to recruit, let it be and be clearly outlined... If one of the stakeholder's role is to market, let it be clear... - P5

All the participants agreed that collaboration and partnerships are essential to success in any public policy development and implementation, which requires multi-stakeholder co-operation and partnerships (Pillay 2000).

Importance of communication

Strategic communication is essential for successful MSPs. The sub-themes give insight into why this is the case (within the context of township industry revitalisation).

Role of communication

All the participants agreed that communication plays a key role in all sectors of society, especially within MSPs:

...communication is very key because... every project collapsed because it was not communicated properly... with all the elements the intentions can be good, but if communication was not properly done across the project, people may not support it... - P1

At the core of this statement is the trust attribute that can be earned within MSPs using communication. This is validated by literature on the excellence theory of communication where PR becomes a critical vehicle used by stakeholders to foster trust (Grunig et al. 2002).

Project communication

This sub-theme emanates from one participant who sees industrial revitalisation as a project. The study revealed that most of the participants are aware of the revitalisation of industrial parks:

... project communication is also about the benefits to society at large because what you do in Limpopo Province might be replicated in KZN for instance... it is communicating about this particular project clearing exactly what the intentions of the project and the values. the sustainability aspect. into the future - P1

Industrial revitalisation

This theme examined how township industrial development can improve socioeconomic development. The majority of the participants (eight out of the 12) were of the view that it was purely for employment creation, whereas four argued that it was motivated by the need for employment creation and to address the racial divide.

Job creation

Most of the participants (eight of the 12) asserted that industrial revitalisation leads to job creation and the improvement of people's livelihoods:

. these industrial parks. created a lot of jobs to those localities based on. their respective homelands. People were working, but so far when you check because of this new dispensation - no more jobs; industrial parks lie forlorn, dilapidated. That's the challenge we're having - P5

In addition, most of the participants indicated that when you compare job creation now to the past, these industries, even though they have high occupancy rates, do not generate jobs:

But majority of the space that we have in the townships, most has been occupied for now. And then, with regards to employment. I've noticed that majority of our black township businesses, they don't generate adequate job opportunities - P2

The total unaudited number of employed people as of 30 September 2021 in the Seshego industrial parks amounted to 1036 individuals (996 blacks and 40 whites), which included 320 youth (including 35 people living with disabilities), 215 females and 501 males (information provided via email by one of the participants).

Meanwhile, in the early 1980s, as part of further enhancing the decentralised industrial programme, Babelegi in Bophuthatswana was viewed as one of "the most successful of the growth points in the independent Bantustans with 14 500 workers" (Wellings &

Black 1986: 6).

Separate development

Four of the 12 participants highlighted the racial motive, plus job creation, as the force behind establishing industries in the townships:

...So it was a political strategy from the apartheid regime. Then the second part... it was to make it a point that economic development, though Black people will then be confined in their respective areas - P6

Four participants agreed that the creation of industries in townships was not a benevolent motive of job creation, but rather to restrict movement and interracial mix. To justify this goal, masked as job creation, they had to build Arms adjacent to blacks. Thus, to restrict the mobility of people from townships, a decentralised industrial policy was designed and introduced to undergird South eAfrica's economy (Naudé & McCoskey 2000).

Influx control

Again, four of the 12 participants highlighted the apartheid policy, plus job creation, as the driver:

I still remember in our area it was in the early 80s to mid 80s... Nkowankowa industrial area was developed ... I think it was obviously part of the whole apartheid ideology of separate development, keeping Africans in the townships...so they don't go to stay in towns and cities - P8

The participants' views were corroborated by Wellings and Black (1986: 2) who asserted that the decentralised industrial policy was specifically "conceived as a means for stabilising the state's system of influx control providing alternatives to metropolitan employment within the Bantustan sub-economies".

Incentives and subsidies

All 12 participants agreed that incentives and subsidies must be reconsidered to attract industrialists and investors. They differ, however, regarding the quantum of subsidies and incentives to be provided:

No. They were supposed to continue with the incentive because you can't say because this was apartheid this is bad. It's not everything bad under apartheid. Jobs is jobs. Poverty is poverty... they were supposed to have used the current system making sure that the people are employed. - P5

The findings indicate that the reason the government is not reintroducing subsidies in the township industries is due to the high demand for space with low rent, as demonstrated by the high occupancy rate:

The average occupancy is between 80% and 90% - P10

The Seshego industries' occupancy rate as of 30 September 2021 was 76% at R20/m2 rental rate, whereas Nkowankowa factories' occupancy rate was 80% at R21/m2 respectively (P1 and P10 email responses). Meanwhile, in the suburb of Midrand commercial property average monthly rental for A-grade office space is R100/m2, while B-grade space costs about R80/m2, and C-grade costs R75/m2 (Rawson Properties 2021).

Sustainability

For this theme and related sub-themes, the participants spoke on their perspectives on the attainment of the SDGs by 2030, in relation to sustainable township development.

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

Altogether, the participants refute that the SDGs will be attained by 2030:

... I don't see those noble goals being achieved. If we still have people losing their jobs on a daily basis by 2030, it will be a disaster. I don't see us meeting the goals in 2030 - P2

To validate the sentiment above, South Africa's President Cyril Ramaphosa alluded to a severe setback to South Africa's ability to realise the SDGs (Ramaphosa 2020).

Industrial parks revitalisation programme

Contrary to the assumption that has been made about the stranded and disused industries around South African townships, the government through the Department of Trade, Industry and Competition (DTIC) and the Development Bank of Southern Africa (DBSA) launched a programme in 2016, dubbed the DTI Industrial Parks Revitalisation Programme (Development Bank of Southern Africa 2021):

... even the new government realised that they can't do without those industrial parks... This was convened by the DTI and then they also invited the DBSA so that we can brainstorm as to how can we revitalise the industrial parks in the country so that they can create more jobs . the discussion yielded the funding from the DBSA... First thing ...was to fence the industrial area, put cameras and also start with the revitalisation. Brand it and market it... to be attractive for investors to come and occupy them - P5

Additionally, the government launched the Industrial Parks Revitalisation Programme, which bears all the hallmarks of the decentralised industrial policy, except that it does not provide subsidies and incentives. According to Solomons (2016), the Industrial Parks Revitalisation Programme aims to promote industrialisation, lure investments, encourage local manufacturing, job creation, and economic growth. The DBSA found that ten of the industrial parks in seven provinces, except for the Northern Cape and Western Cape, needed to be repaired and refurbished (Development Bank of Southern Africa 2021).

Another major finding is that although the DTIC has launched the revitalisation programme and most of the industries are occupied, they are not generating enough jobs to make any dent in township socio-economic development and livelihoods.

CONCLUSION

This study revealed a few core findings. These relate to strategic MSPs, communication, industrial parks revitalisation, sustainability (as it relates particularly to job creation), and the revision of industrial policy. The findings indicate that strategic MSPs and communication were unanimously supported by the participants as key drivers of success in the revitalising of township industries.

First, all the participants unanimously found strategic MSPs to be key drivers in township industrial revitalisation. No individual government entity is the driver of industrial policy. The participants highlighted that operating in silos among government entities is the main issue hampering policy implementation (Pillay 2000). Relevant stakeholder identification, the definition of roles and responsibilities in the form of terms of references, as well as partnership and collaboration were cited as key considerations for MSPs to revive township industries (Mitchell et al. 1997).

Communication had been fully endorsed as critical to MSPs because through communication people articulate the purpose of a project, exchange valuable information, remove barriers to MSPs, and co-create value (Botan & Hazelton 2006: 13). Despite the challenges of the Covid-19 pandemic, which drove people to explore various technological forms of communication, the participants emphasised the importance of traditional channels of communication in information sharing. While they acknowledged the increased role of social media (especially amongst the youth), they cited, among others, public participation, radio stations, loud hailing, churches and community-based structures as important vehicles through which MSPs could communicate initiatives such as township industrial revitalisation.

The government, through the DTI, has launched the Industrial Parks Revitalisation Programme with the Development Bank of Southern Africa (DBSA) as its implementing agent (Development Bank of Southern Africa 2021). That was confirmed by six of the participants who were responsible for land and commercial property portfolios in various districts of Limpopo. However, they acknowledged that most industries had been vandalised and have been lying forlorn for a period of time.

There are two phases to the programme. Phase one includes the provisioning of security and fencing. Phase two is focused on the overall refurbishment of the factories' physical structures. However, unlike the decentralised industrial policy, incentives and subsidies have been withdrawn. Nkowankowa and Seshego had already received their first batch of phase one allocations for security upgrades. Most of the participants indicated that unless subsidies and incentives were reintroduced, the industrial areas would not attract major investors, despite their competitive low rental rates.

One of the disappointing findings was that the current industrial zones in townships were not correspondingly generating enough jobs to make a large socio-economic impact, despite the high occupancy rates. The participants revealed that part of the reason industries were not generating jobs was because most of them have deviated from their former manufacturing or processing mandates. The current occupants of these industrial zones are more service-oriented (mortuaries, hair salons, churches, schools, etc.). According to the respondents, this did not bode well for large-scale sustainable job creation. Most of the participants recommended that the reintroduction of subsidies and incentives could lure foreign investors into these areas. It was recommended that the government not make rentals available for a high occupancy rate and that it should rather focus on businesses with a high rate of intensive labour absorption.

The final key finding focused on the revision of industrial policy. Most of the participants conceded that the remnants of the decentralised industrial policy, particularly incentives and subsidies, could lure both domestic and foreign investors into considering setting up their manufacturing base if the government made it attractive. They proposed either the 90:10 or 80:20 principle, where 10 to 20% would constitute the government incentives, while industrialists paid the rest.

REFERENCES

Alexander, M. 2018. The homelands. [Online]. Available at: https://southafrica-info.com/infographics/provinces-homelands-south-africa-1996/ [Accessed on 2 May 2021]. [ Links ]

Beck, J. 1968. Border industries. The Black Sash, February. [Online]. Available at: https://www.sahistory.org.za/sites/default/flles/archiveflles/BSFeb68.0036.4843.011.004.Feb%201968.8.pdf [Accessed on 9 March 2021]. [ Links ]

Bhorat, H. & Hodge, J. 1999. Decomposing shifts in labour demand in South Africa. The South African Journal of Economics 67(3): 155-168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1813-6982.1999.tb01146.x [ Links ]

Biko, S. 2004. I write what I like. Johannesburg: Picador Africa. [ Links ]

Botan, C. & Hazleton, V.H. 2006. Public relations theory II. (Second edition). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. 2012. Thematic analysis. In: Cooper, H. (ed.) APA handbook of research methods in psychology: Volume 2 Research designs. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13620-004 [ Links ]

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. 2013. Successful qualitative research: a practical guide for beginners. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Creswell, J.W. 2012. Education research: planning, conducting and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. (Fourth edition). Boston, MA: Pearson. [ Links ]

Daniel, L. 2021. R700 million allocated to township entrepreneurs - here is how the money is being split. Business Insider South Africa, 1 June. [Online]. Available at: https://bit.ly/3iDLL69 [Accessed on 22 June 2021]. [ Links ]

Department of Trade and Industry. 2000. Special Economic Zones: tax special guide. [Online]. Available at: http://www.thedtic.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/SEZ_Guide.pdf [Accessed on 5 May 2021]. [ Links ]

Department of Trade and Industry. 2007. A National Industrial Policy Framework. [Online]. Available at: https://bit.ly/3Vy1Qsr [Accessed on 3 May 2021]. [ Links ]

Desai, V. & Alex, L. 2012. Speculating on slums: infrastructural fixes in informal housing in the Global South. Antipode 45(4): 789-808. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-83330.2012.01044.x [ Links ]

Development Bank of Southern Africa. 2021. Revitalisation of Industrial parks. [Online]. Available at: https://bit.ly/3F0mCde [Accessed on 9 November 2021]. [ Links ]

Drucker, P. 1999. Management challenges for the 21st century. New York: Harper. [ Links ]

Freeman, R.E. 1984. Strategic management: strategic management approach. Boston: Pitman. [ Links ]

Freeman, R.E. 2004. The stakeholder approach revisited. ZFWU. Journal for Business, Economics and Ethics 5(3): 228-254. https://doi.org/10.5771/1439-880X-2004-3-228 [ Links ]

Frith, A. 2021a. Nkowankowa: main place 962049 from census 2011. [Online]. Available at: https://census2011.adrianfrith.com/place/962049 [Accessed on 3 November 2021]. [ Links ]

Frith, A. 2021b. Seshego: main place 974043 from census 2011. [Online]. Available at: https://census2011.adrianfrith.com/place/974043 [Accessed on 3 November 2021]. [ Links ]

Grunig, L.A., Grunig, J.E. & Dozier, D.M. 2002. Excellence public relations and effective organisations: A study of communication management in three countries. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Hill, L. 1996. Building effective one-on-one work relationships. Harvard Business School Technical Notes, 9-497-028. [Online]. Available at: https://bit.ly/3Bandbg [Accessed on 5 May 2021]. [ Links ]

Jeffrey, B., Rotberg, R.I. & Adams, J. 1978. The Black Homelands of South Africa: the political and economic development of Bophuthatswana and Kwa-Zulu. Berkeley: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Jensen, S. & Zenker, O. 2015. Homelands as frontiers: apartheid's loose ends - an introduction. Journal of Southern African Studies 41(5): 937-952. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070.2015.1068089 [ Links ]

Kenny, G. 2012. From a stakeholder viewpoint: Designing measurable objectives. Journal of Business Strategy 33(6): 40-46. https://doi.org/10.1108/02756661211281507 [ Links ]

Louw, M. 2014. Ethics in research. In: Du Plooy-Cilliers, F., Davis, C. & Bezuidenhout, R.M. (eds). Research Matters. Cape Town: Juta. [ Links ]

Marr, J.W. & Walker, S.F. 2002. Stakeholder power: a winning plan for building stakeholder commitment and driving corporate growth. Cambridge, MA: Perseus. [ Links ]

McKenna, A. 2021. Seshego: South Africa. Britannica. [Online]. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/place/Seshego [Accessed on 3 November 2021]. [ Links ]

Merriam, S.B. 2009. Qualitative research: a guide to design and implementation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Mitchell, R.K., Agle, B.R & Wood, D.J. 1997. Theory of stakeholder identification and salience. Academy of Management Review 1: 853-854. [Online]. Available at: https://www.stakeholdermap.com/stakeholder-analysis/stakeholder-salience.html [Accessed on 5 May 2021]. https://doi.org/10.2307/259247 [ Links ]

Mosiane, N. 2020. Mobility, access and the value of the Mabopane station precinct. [Online]. Available at: https://wiser.wits.ac.za/system/flles/seminar/Mosiane2020.pdf [Accessed on 26 June 2021]. [ Links ]

Mulder, J. 2016. Social legitimacyin the internal market: a dialogue of mutual responsiveness. Unpublished doctoral thesis. European University Institute. Florence, Italy. [Online]. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/1814/41264 [Accessed on 11 November 2021]. [ Links ]

Naudé, C. & McCoskey, S.K. 2000. Spatial development initiatives and employment creation: will they work? [Online]. Available at: https://bit.ly/3B8s3Wk [Accessed on 29 May 2021]. [ Links ]

Phalatse, M.R. 2000. From industrialisation to de-industrialisation in the former South African homelands: the case of Mogwase, North West. Urban Forum 11(1): 149-161. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03036836 [ Links ]

Pillay, P. 2000. South Africa in the 21st century: some key socio-economic challenges. [Online]. Available at: http://library.fes.de/pdf-flles/bueros/suedafrika/07195.pdf [Accessed on 3 May 2021]. [ Links ]

Plano Clark, V.L. & Creswell, J.W. 2015. Understanding research: a consumer's guide. (Second edition). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. [ Links ]

Polit, D.F. & Beck, C.T. 2012. Nursing research: generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice. (Ninth edition). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [ Links ]

Ramaphosa, C. 2020. High level meeting of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals moment. [Online]. Available at: https://www.gov.za/speeches/president-cyril-ramaphosa-virtual-high-level-meeting-united-nations-sustainable-development [Accessed on 5 May 2021]. [ Links ]

Rawson Properties. 2021: Overview: commercial property market in Midrand. [Online]. Available at: https://blog.rawson.co.za/exciting-commercial-property-market-in-midrand [Accessed on 5 November 2021]. [ Links ]

Selebi, O. 2019. Towards a communication framework for South Africa's national development plan. Unpublished doctoral thesis. University of Pretoria. Pretoria, South Africa. [ Links ]

Skinner, C., Mersham, G. & Benecke, R. 2013. Handbook of public relations. (Tenth edition). Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Solomons, I. 2016. Seshego industrial park receives R21 million boost from DTI. Engineering News, 28 July. [Online]. Available at: https://bit.ly/3ulUUTk [Accessed on 1 November 2021]. [ Links ]

South African History Online. 2021. The homelands. [Online]. Available at: https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/homelands.html [Accessed on 22 February 2021]. [ Links ]

Statistics South Africa. 2011. Census 2011. [Online]. Available at: http://www.statssa.gov.za/?page_id=4286&id=13156 [Accessed on 3 November 2021]. [ Links ]

United Nations Development Programme. 2021. Goal 9: industry, innovation and infrastructure. [Online]. Available at: https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sustainable-development-goals/goal-9-industry-innovation-and-infrastructure.html [Accessed on 19 February 2021]. [ Links ]

United Nations Development Programme. 2021. Sustainable development goals knowledge platforms. [Online]. Available at: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdinaction [Accessed on 5 May 2021]. [ Links ]

United Nations General Assembly. 2003. Enhanced cooperation between the UN and all relevant partners, in particular the private sector, 18 August. Report of the Secretary-General. [ Links ]

Wellings, P. & Black, A. 1986. Industrial decentralization under apartheid: the relocation of industry to the South African periphery. World Development 14(1): 1-38. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(86)90094-X [ Links ]

Date submitted: 19 January 2022

Date accepted: 28 September 2022

Date published: 8 December 2022